Abstract

Defence priming by organismal and non-organismal stimulants can reduce effects of biotic stress in plants. Thus, it could help efforts to enhance the sustainability of agricultural production by reducing use of agrochemicals in protection of crops from pests and diseases. We have explored effects of applying this approach to both Arabidopsis plants and seeds of various crops in meta-analyses. The results show that its effects on Arabidopsis plants depend on both the priming agent and antagonist. Fungi and vitamins can have strong priming effects, and priming is usually more effective against bacterial pathogens than against herbivores. Moreover, application of bio-stimulants (particularly vitamins and plant defence elicitors) to seeds can have promising defence priming effects. However, the published evidence is scattered, does not include Arabidopsis, and additional studies are required before we can draw general conclusions and understand the molecular mechanisms involved in priming of seeds’ defences. In conclusion, defence priming of plants has clear potential and application of bio-stimulants to seeds may protect plants from an early age, promises to be both labour- and resource-efficient, poses very little environmental risk, and is thus both economically and ecologically promising.

Subject terms: Environmental biotechnology, DNA methylation, Biotic, Environmental impact

Introduction

Pesticides are used by farmers globally to protect crops from pests and diseases1, and they played important roles in “the green revolution” that brought huge benefits for agriculture and mankind2. However, conventional uses of pesticides also have serious drawbacks as they contaminate the environment3, cause fatalities1, and may foster a false sense of security regarding risks of pest outbreaks4. Hence, both national and international authorities, e.g., FAO5 and EU6 advocate development of alternative strategies.

Current approaches include biotechnological enhancement of plant resistance7 and optimization of integrated management efforts8. In addition, organismal interactions can be used to promote natural plant resistance interactions and mechanisms9–13. There is increasing evidence14,15 that plant-associated microorganisms can bolster plants’ resistance to biotic stresses. Inter alia, authors including16,17 have shown that manipulations of single microorganisms or entire microbiomes can enhance plant health. Plant resistance to biotic stressors can also be strengthened by activating plant defences through innovative uses of non-toxic internal or environmental bio-stimulants18–20.

Such stimulants can “prime” plants’ defences, i.e. enhance their responsiveness to biotic stressors21–23, thereby potentially offering a sustainable alternative to use of conventional plant protection chemicals24–27. Priming initially triggers a minor part of a defence response that increases the plant’s ability to defend itself against future antagonists (for example herbivores or pathogens). Once a plant has been primed, it will defend itself more rapidly, strongly and/or enduringly against subsequent threats. Priming agents may be live organisms (e.g. microorganisms or arthropods), chemicals (e.g. vitamins or plant hormones) or components thereof, and priming can be applied to various tissues and at diverse developmental stages (for example to foliage or roots of mature plants, or to seeds).

Molecular mechanisms underlying priming are far from completely understood, but there is a consensus that primed plants conserve a memory. Two potential mechanisms have been suggested. One involves accumulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MPKs). For example, Beckers et al.28 found that two MPKs (MPK3 and MPK6) accumulate during induction of systemic acquired resistance (SAR) by benzothiadiazole (BTH). Gene expression studies of knockout mutants showed that the kinases remain dormant until the plant is under attack, which initiates accumulation of defence enzymes (Ibid.). The other suggested mechanism is that epigenetic changes in DNA methylation and histone modifications may be carriers of stress memories and triggers of immune responses29–31. Reversible histone acetylation may be involved, at least in some cases, according to suggestions by Chen and Tian32 and observations of Arabidopsis plants’ responses to BTH31. Similarly, Lopez Sanchez, et al.33 found that hypomethylated Arabidopsis mutants were resistant to the biotrophic pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis, whereas hypermethylated mutants were susceptible.

Numerous studies of plants’ defences have provided detailed information about how plants recognise attackers, the resulting modulation of hormonal pathways, and effects at multiple metabolic and physiological levels34–36. Diverse priming agents and biotic stresses have been applied to diverse plant taxa in various developmental stages. Clearly, it would be helpful to identify general patterns in responses, and their relationships (if any) with priming agents or antagonists. Therefore, we have sought such patterns and relationships through review of seed priming documented for various crops and meta-analyses of studies of priming of Arabidopsis plants. As effects of dosage and priming agent may be plant-species dependent, we focused our meta-analysis on one species and used Arabidopsis as a model. This is the first meta-analysis of defence priming in any plant species.

Results

Seed priming in Arabidopsis

Evidence of enhanced resistance to biotic stresses has been found in several plant systems after priming seeds’ defences using biological organisms or chemical biostimuli (see Table 1). Defence priming appears to generally enhance plants’ health, either by reducing effects of herbivore damage or disease symptoms, or by impairing the growth of populations or replication of pests or pathogens.

Table 1.

Overview of seed priming studies.

| Host Plant (HP) | Priming Stimulus* | Stress Agent (ASA)** | Trait | Priming*** | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. cv. PKM-1 | Bacillus subtilis (TN_Vel-35) (b) | Alternaria solani (f) | HP: Gene expr. & enz. activity (POX, PPO)│Growth, yield, nutrient uptake, germination, vigour ASA: Disease symptoms | HP (+│+) ASA (−) | Babu et al. (2015) |

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. cv. PKM-1 | Azotobacter chroococcum (KR_Tri-17) (b) | Alternaria solani (f) | HP: Enz. activity (POX, PPO)│Growth, yield, nutrient uptake, vigour ASA: Disease symptoms | HP (+│+) ASA (−) | Babu et al. (2015) |

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. cv. PKM-1 | Bacillus cereus KA_Mys-39 (b) | Alternaria solani (f) | HP: Enz. activity (POX, PPO)│Growth, yield, nutrient uptake, germination, vigour ASA: Disease symptoms | HP (+│+) ASA (−) | Babu et al. (2015) |

| Pisum sativum L. | Pseudomonas chlororaphis MA 342 (b) | Acyrthosiphon pisum (a) | ASA: Population growth | ASA (−) | Hamada et al.27 |

| Capsicum annuum L. cv. Bukwang | Bacillus gaemokensis (PB69) metabolites (b) | Pseudomonas syringae pv. lachrymans (b) Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. vesicatoria (b) | HP: Gene expr. (LOX)│Growth, yield ASA: Disease symptoms | HP (+│+) ASA (−) | Song et al.18 |

| Cucumis sativus L. cv. Backdadagi | Bacillus gaemokensis (PB69) metabolites (b) | Pseudomonas syringae pv. lachrymans (b) Spodoptera litura (l) | HP: Gene expr. (LOX)│Growth, yield ASA: Disease symptoms, expansion rate, survival rate | HP (+│+) ASA (−) | Song et al.18 |

| Gossypium hirsutum | Beauveria bassiana (f) | Aphis gossypii (a) | ASA: Population growth | ASA (−) | Castillo Lopez et al. (2014) |

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. cv. Oogata-fukuju | Trichoderma harzianum (TriH_JSB27) (f) | Ralstonia solanacearum (b) | HP: Gene expr. & enz. activity (PAL)│Growth, yield, nutrient uptake, germination, vigour ASA: Disease symptoms | HP (+│+) ASA (−) | Jogaiah et al.15 |

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. cv. Oogata-fukuju | Trichoderma harzianum (TriH_JSB36) (f) | Ralstonia solanacearum (b) | HP: Growth, yield, nutrient uptake, germination, vigour ASA: Disease symptoms | HP (+) ASA (−) | Jogaiah et al.15 |

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. cv. Oogata-fukuju | Penicillium chrysogenum (PenC_JSB41) (f) | Ralstonia solanacearum (b) | HP: Gene expr. & enz. activity (PAL)│Growth, yield, nutrient uptake, germination, vigour ASA: Disease symptoms | HP (+│+) ASA (−) | Jogaiah et al.15 |

| Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. cv. Oogata-fukuju | Phoma multirostrata (PhoM_JSB17) (f) | Ralstonia solanacearum (b) | HP: Growth, yield, nutrient uptake, germination, vigour ASA: Disease symptoms | HP (+) ASA (−) | Jogaiah et al.15 |

| Helianthus annuus L. cv. Morden | Trichoderma harzianum PGPFYCM-14 (f) | Plasmopara halstedii (o) | HP: Growth, yield, nutrient uptake, germination, vigour ASA: Disease symptoms | HP (+) ASA (-) | Nagaraju et al. (2012) |

| Picea abies | JA | Hylobius abietis (bc) | HP: Growth ASA: Attack, girdling | HP (0) ASA (−) | Berglund et al.26 |

| Solanum lycopersicum cv Carousel | JAa | Tetranychus urticae (s) Myzus persicae (a) Manduca sexta (l) Botrytis cinerea (f) | HP: Gene expr. (PinII)│Growth, yield ASA: Disease symptoms, population growth, fecundity, survival | HP (+│0) ASA (−) | Worrall et al.20 |

| Capsicum annuum L. cv. Bukwang | BTHb | Pseudomonas syringae pv. lachrymans (b)Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. vesicatoria (b) | HP: Gene exp. (PR1) ASA: Damage symptoms | HP (+) ASA (−) | Song et al.18 |

| Cucumis sativus L. cv. Backdadagi | BTHb | Pseudomonas syringae pv. lachrymans (b) | HP: Gene expr. (PR2)│Growth, yield ASA: Disease symptoms, expansion rate | HP (+│0) ASA (−) | Song et al.18 |

| Solanum lycopersicum cv Carousel | BABAc | Oidium neolycopersici (f) | ASA: Colonization | ASA (−) | Worrall et al.20 |

| Picea abies | NIA (v:B3) | Hylobius abietis (bc) | HP: Growth ASA: Girdling | HP (0) ASA (−) | Berglund et al.26 |

| Picea abies | NIC (v:B3) | Hylobius abietis (bc) | HP: Growth ASA: Attack, girdling | HP (0) ASA (−) | Berglund et al.26 |

| Hordeum vulgare L. | Thiamine (v:B1) | Rhopalosiphum padi (a) Sitobion avenae (a) | ASA: Population growth, fecundity, settlement | ASA (−) | Hamada & Johnsson66 |

| Pisum sativum L. | Thiamine (v:B1) | Acyrthosiphon pisum (a) | ASA: Population growth | ASA (−) | Hamada & Johnsson66 |

| Avena sativa L. | Thiamine (v:B1) | Rhopalosiphum padi (a) | ASA: Population growth, fecundity, settlement | ASA (−) | Hamada et al.27 |

| Hordeum vulgare L. | Thiamine (v:B1) | Myzus persicae (a) Rhopalosiphum padi (a) | ASA: Population growth, fecundity, settlement, lifespan | ASA (−) | Hamada et al.27 |

| Pisum sativum L. | Thiamine (v:B1) | Myzus persicae (a) Acyrthosiphon pisum (a) | ASA: Population growth, settlement | ASA (−) | Hamada et al.27 |

| Triticum aestivum L. | Thiamine (v:B1) | Myzus persicae (a) Rhopalosiphum padi (a) | ASA: Population growth, fecundity, settlement, lifespan | ASA (−) | Hamada et al.27 |

| Pennisetum glaucum (L.) | Thiamine (v:B1) | Sclerospora graminicola (o) | HP: Enz. activity (LOX)│Growth ASA: Disease symptoms | HP (+│+) ASA (−) | Pushpalatha et al.62 |

| Pennisetum glaucum (L.) | Riboflavin (v:B2) | Sclerospora graminicola (o) | HP: Growth, yield, germination, vigour ASA: Disease symptoms | HP (+) ASA (−) | Pushpalatha et al.62 |

| Pennisetum glaucum (L.) | Niacin (v:B3) | Sclerospora graminicola (o) | HP: Growth, yield, germination, vigour ASA: Disease symptoms | HP (+) ASA (−)(−) | Pushpalatha et al.62 |

| Pennisetum glaucum (L.) | MSB (v:K3) | Sclerospora graminicola (o) | HP: Growth, yield, germination, vigour ASA: Disease symptoms | HP (+) ASA (−) | Pushpalatha et al.62 |

Priming Agents: JA = Jasmonic acid, BABA = beta-aminobutyric acid, MSB = menadione sodium bisulphite, NIA = nicotinic acid, NIC = nicotinamide, BTH = benzothiadiazole, v: = vitamin:type. Antagonist Stress Agent: (s) = spider mite, (a) = aphid, (bc) = beetle, coleoptera, (l) = caterpillar, lepidopteran, (f) = fungus, (b) = bacteria, (o) = oomycota. Response Trait: trait used to assess priming effect: e.g. growth, damage symptoms or gene activity (PAL = Phenylalanine ammonia lyase, POX = peroxidase, PPO = polyphenol oxidase, LOX = lipoxygenase). Priming: Evidence of phenotypic differences between primed and un-primed plants, measuring directly on host plant (HP) or indirectly as antagonist stress agent response (ASA); (+) = enhanced, (−) reduced, (0) = no difference.

aJA had a negative effect on Solanum lycopersicum primary root length.

bBTH had a positive effect on Spodoptera litura weight in Cucumis sativus L. cv. Backdadagi, and a negative effect on Capsicum annuum L. cv. Bukwang shoot length.

cBABA had a positive effect on mean area of lesions caused by Botrytis cinerea.

More than 200 studies identified through the Web of Science searches investigated effects of priming seeds on the subsequent growth and development of Arabidopsis plants, but far fewer (11) reported effects of defence priming on biotic stress resistance, and none included the model plant Arabidopsis. With the diverse experimental backgrounds meta-analyses could not be performed on this dataset. However, a general conclusion is that priming with (for instance) vitamins and plant hormones has reportedly enhanced the resistance of many crops to a wide array of antagonists. In addition, increases in expression of defence genes recorded in the 11 studies were generally interpreted as increases in resistance, although neither general nor specific metabolomic responses were necessarily considered.

Meta-analysis data

Of the 835 papers initially identified by Web of Science searches, 77 (describing 296 experiments) met the inclusion criteria. Of the excluded studies, 52% lacked information about the priming agent or biotic stress or the study was irrelevant, ca. 38% did not include experiments with wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana plants, ca. 3% were not peer-reviewed research articles, and 2% did not include data on performance of the antagonist. The remaining ca. 6% lacked information about sample sizes or errors, had poor figure resolution, included retracted or un-available parts or were studies of transgenerational priming.

The 296 studies (all included in the meta-analyses) documented results of applying defence priming treatments to foliage or root tissue, but not seed priming, except for a few studies of priming via soil enrichment by bacterial or fungal agents37–40.

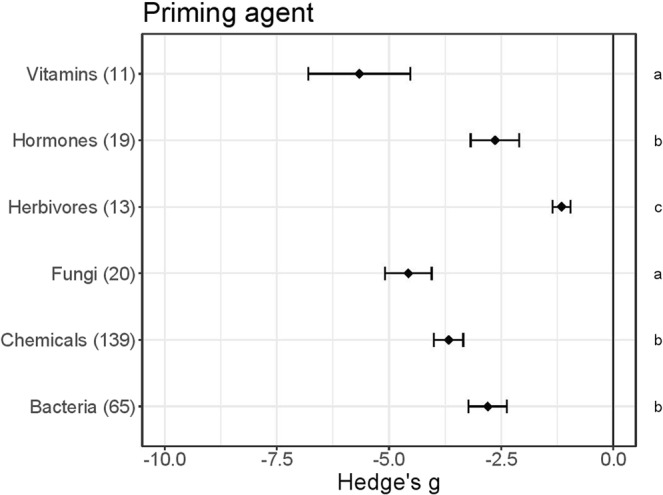

Plant priming increases resistance to biotic stress

To meet our objective of identifying patterns in priming responses we focused on experiments involving application of priming treatments to the model plant Arabidopsis (in vegetative stages), to exploit the large pool of relevant available information41. We used data drawn from 267 independent Arabidopsis defence priming experiments, reported in 77 papers, in our meta-analyses. In all of these experiments whole plants were exposed to either selected bio-stimuli or live organisms in the priming treatments. In almost all of the experiments priming enhanced resistance to biotic stress, on average (Fig. 1, Hedge’s g < 0). Ca. 7% (19 of 267 studies) suggested that it had no or negative effects on plant resistance (Hedge’s g > 0). Vitamins and microorganisms proved to be stronger primers, providing better general protection, than herbivores (Dunn’s test, P < 0.05). In addition, fungi primed Arabidopsis plants more strongly than bacteria (Dunn’s test, P = 0.002)). When ranking individual priming agents across all categories, priming with riboflavin and BABA yielded the highest improvement of plant resistance to biotic stresses, whereas aphids, caterpillars and ologigalacturonides (OGs) performed as the worst priming agents (Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Resistance effects of priming Arabidopsis plants with indicated agents. Results of meta-analysis of data obtained from 267 experiments described in 77 publications. Negative values imply that primed plants were more resistant (less damaged or associated with lower pest fitness) than unprimed controls. Numbers of experiments are shown in brackets, and symbols specify means of Hedge’s g ± SE bars, equivalent to effects of groups of priming agents (Vitamins, Hormones, etc.). Different letters along the right-hand axis indicate significant differences according to the Kruskal Wallis test (α = 0.05) followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test to rank differences (α = 0.05).

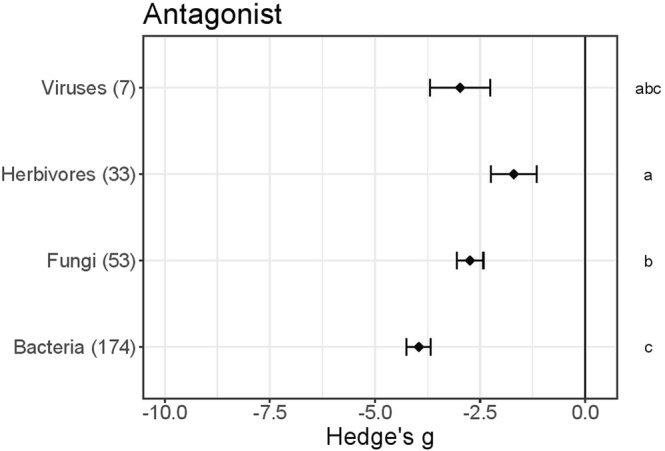

No general advantage of self-priming

As several organisms had been used to prime the plants, we investigated their relative efficacy and dependence of their effectiveness on the antagonist used in the tests (Fig. 2). The meta-analyses suggested that priming with organisms is more likely to protect plants against bacterial and fungal antagonists than against herbivores (Dunn’s test, P < 0.05). In addition, there was no significant indication that “self” priming (i.e. priming by an organism that is later used as a stressor) was either more or less advantageous than priming by another organism. For example, Kruskal-Wallis rank sum tests detected no significant differences (P > 0.05) in effects of priming with fungal and non-fungal agents on fungal infections (N = 53), or effects of priming with herbivore and non-herbivore agents on herbivore damage (N = 33). However, bacterial “self” priming (Hedge’s g = −3.7 ± 0.6, N = 44) provided weaker protection than fungal priming against bacteria (Hedge’s g = −5.5 ± 0.7, N = 11, Dunn’s test, P < 0.05; Fig. S2). Note, throughout the paper, data in x ± y format are means ± standard errors.

Figure 2.

Enhancement of primed Arabidopsis plants’ resistance to indicated antagonists (i.e. ASA in Table 1). Results of meta-analysis of data obtained from 267 experiments described in 77 publications. Hedge’s g indicates the treatment effect for each taxonomic group of antagonists, and negative values imply that primed plants were less damaged (or hosted less fit antagonists) than unprimed controls. Numbers of relevant experiments are shown in brackets, and symbols specify means of Hedge’s g ± SE bars. Different letters along the right-hand axis indicate significant differences according to the Kruskal Wallis test (α = 0.05) followed by Dunn’s test post-hoc test to rank differences (α 0.05).

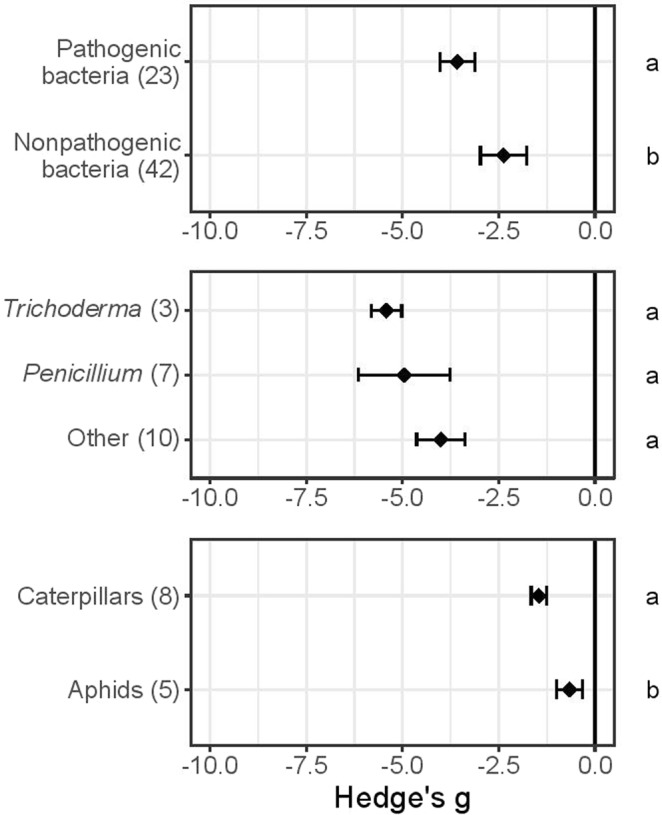

Evidence of organismal-specific priming effects

We also assessed variations in reported effects of defence priming among sub-groups of organisms (Fig. 3). Pathogenic bacteria reportedly induced significantly stronger resistance (Hedge’s g = −3.6 ± 0.5, N = 23) than non-pathogenic bacteria (Hedge’s g = −2.4 ± 0.6, N = 42; Wilcoxon rank sum test, P < 0.001; Fig. 3a). This result appears, however, to be highly affected by the difference in antagonist composition between the groups. Herbivores for example make up ca. 43% of the antagonists in the non-pathogenic bacteria dataset whereas pathogenic bacteria have 9% herbivores. When excluding herbivores, non-pathogenic bacteria appears to induce slightly stronger resistance (Hedge’s g = −3.7 ± 1.0, N = 24) compared to pathogenic bacteria (Hedge’s g = −3.6 ± 0.5, N = 21; Wilcoxon rank sum test, P = 0.04). In addition, as shown in Fig. 3b, Trichoderma induced somewhat higher resistance (Hedge’s g = −5.4 ± 0.4, N = 3) than Penicillium (Hedge’s g = −5.0 ± 1.2, N = 7), which induced stronger priming than “Other” fungi (including Phoma sp. and baker’s yeast; Hedge’s g = −4.0 ± 0.6, N = 10). However, these differences were not significant according to the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test, possibly because the sample numbers did not provide sufficient statistical power. Herbivores used as priming agents were divided into two classes: aphids (Hedge’s g = −0.7 ± 0.3, N = 5) and caterpillars (Hedge’s g = −1.5 ± 0.2, N = 8). Caterpillars had significantly stronger priming effects than aphids according to Student’s t-test (P = 0.048, Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

Enhancement of primed Arabidopsis plants’ effects on indicated sub-groups of groups of antagonists (ASA in Table 1). Negative mean values of Hedge’s g indicate that primed plants were less damaged (or hosted less fit antagonists) than unprimed controls. Results show: (a) differing effects of priming on pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria; (b) lack of significant differences in effects on fungal sub-groups (Penicillium, Trichoderma and “Other” (e.g. Phoma and Saccharomyces cerevisiae); (c) differing effects on aphid and caterpillar herbivores. Different letters along the right-hand axis indicate significant differences according to the Kruskal Wallis test, Wilcoxon rank sum test or Student’s t-test (α 0.05), followed by post-hoc Dunn’s test (α 0.05).

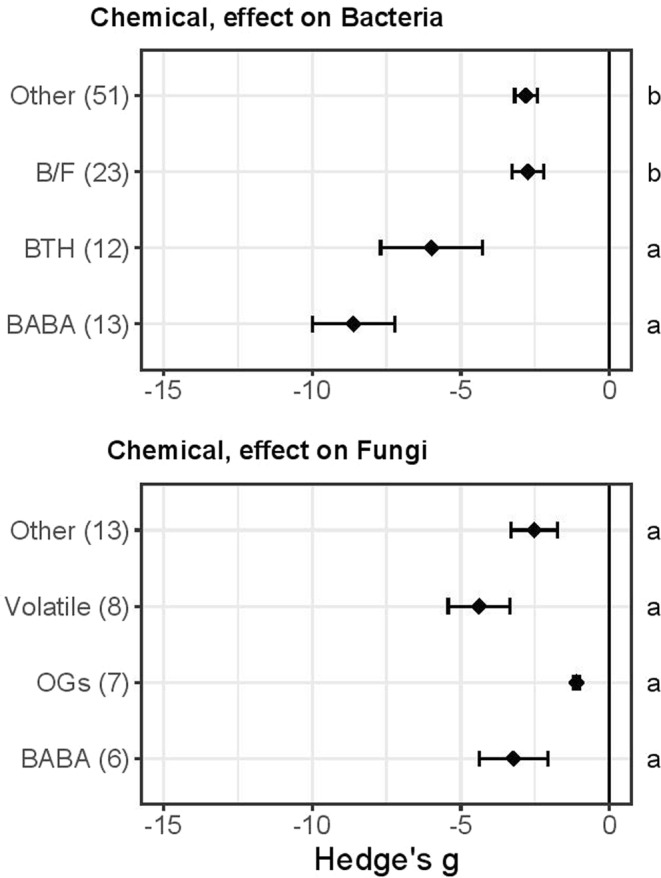

Evidence of priming effects of plant-related elicitors

Chemical priming was included in many experiments (N = 139) and effects of diverse biotic stressors were tested. The tested chemical compounds included two classes of phytohormones, jasmonic acid compounds (JA and MeJA; Hedge’s g = −2.8 ± 1.1, N = 9) and salicylic acids (Hedge’s g = −2.5 ± 0.4, N = 10), which did not apparently differ in priming strength (Wilcoxon rank sum, P > 0.05). There was also no significant difference between effects of the B vitamins thiamine (Hedge’s g = −4.7 ± 1.5, N = 7) and riboflavin (Hedge’s g = −7.4 ± 1.6, N = 4; Wilcoxon rank sum, P > 0.05). To further investigate priming compounds’ effects, we tested differences in priming effects of four kinds of elicitors —BABA, BTH, selected bacterial and fungal compounds (B/F), and “Other” — on bacterial antagonists. The results indicated that, generally, chemical priming protects Arabidopsis against bacterial antagonists (Fig. 4a). Moreover, BABA provides the strongest protection (Hedge’s g = −8.6 ± 1.4, N = 13), followed by BTH (Hedge’s g = −6.0 ± 1.7, N = 12), “Other” (Hedge’s g = −2.9 ± 0.4, N = 50), and B/F (Hedge’s g = −2.7 ± 0.5, N = 23). Differences between chemical priming agents on bacterial antagonists were confirmed statistically (Dunn’s test, P < 0.05). In addition, several chemicals reportedly primed Arabidopsis against fungal infections (Fig. 4b), including BABA (Hedge’s g = −3.2 ± 1.2, N = 6), volatiles (Hedge’s g = −4.4 ± 1.0, N = 8), oligogalacturonides (OGs, Hedge’s g = −1.1 ± 0.1, N = 7) and “Other” compounds (Hedge’s g = −2.5 ± 0.8, N = 13). However, we found no significant differences between effects of those compounds (Kruskal-Wallis rank sum, P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Differences in effects of priming by chemicals on bacterial and fungal antagonists. (a) Effects on bacteria of beta-aminobutyric acid (BABA), benzothiadiazole (BTH), compounds derived from bacteria or fungi (B/F), and associated compounds (“Other”). B/F included flg22, lipopolysaccharides, hairpin protein, ergosterol, siderophores, cyclic dipeptides, and a bacterial quorum-sensing molecule. Data from experiments with chemicals used in ≤2 studies were pooled, forming the category “Other”. These include pentanol, dehydroabietinal, steroid, oligogalacturonides, 1,2-benzisothiazol-3(2 H)-one1,1-dioxide (BIT), azelaic acid, E-2-hexenal, glutathione, glutathione disulphide, pipecolic acid, sulphanilamides, amino acids (Gly, Cys, Ser, Ala, Asp, Asn, Glu), and compounds derived from algae or oomycota. (b) Effects on fungi of volatiles, oligogalacturonides (OGs), BABA and other chemicals. In this case data from experiments with chemicals described in only one article were pooled, and they include thymol, allose, glycine, abietic acid, 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid, galacturonic acid, indole-3–carboxylic acid, hypoxanthine, hexanoic acid, BTH, and flg22. Symbols specify mean values of Hedge’s g ± SE. Negative values imply that primed plants were more resistant (less damaged or associated with lower pest fitness) than unprimed control plants. Different letters along the right-hand axis indicate significant differences according to the Kruskal Wallis test and comparisons performed with post-hoc Dunn’s test (α 0.05).

Quality control of the database

Publication biases were evaluated with funnel plots, which were either symmetric suggesting that data were unbiased (for example, for herbivore priming effects and resistance), or slightly asymmetric, suggesting that data were slightly biased (Fig. S3). However, Fail-safe numbers indicating the number of non-significant findings required to reject the outcome of a meta-analysis suggested that our database was highly representative (Table S4).

Discussion

Fungi and vitamins prime Arabidopsis plants’ defences most strongly

There is ample evidence that seed defence priming with diverse agents can protect various plant species against diverse antagonists (Table 1). Curiously, we found no published studies that assessed effects of priming defences of Arabidopsis seeds, apart a few indicating that enrichment of soil by bacterial or fungal agents may have indirect priming effects40,42–44. Regarding priming at the plant stage, we found 835 Arabidopsis studies of which 77, describing 267 experiments, fulfilled our requirements. More specifically, they provide information on effects of priming by organisms or plant-derived elicitors on defences against bio-stresses, including quantifiable details about antagonist responses (Supplementary Material List S5). Meta-analysis of this information confirmed that such priming generally enhances pest or pathogen resistance in Arabidopsis, and that fungi and vitamins have stronger effects than other tested agents, inducing stronger resistance to bacterial and fungal antagonists than to herbivores. The meta-analyses summarize indications of priming strength and antagonist specificity in previous studies, which may support future efforts to study and understand defence priming in Arabidopsis and other plants.

Priming agents and their generality

Organismal priming: microorganisms

An increasing number of studies suggest that plant resistance may be orchestrated interactively with associated organisms45 and those interactions could potentially be commercially manipulated46. Below-ground relationships with mycorrhizal fungi and bacteria, for example, not only promote growth, but also reduce damage to above-ground parts47, pre-inoculation of fungal endophytes modulates later plant disease development47–49, and spread of Heterobasidion (stem rot) to healthy spruce trees may be avoided by applying Phlebiopsis gigantean fungal spores to stumps50. Spontaneous associations between microbiomes and plants further suggest that cross-kingdom associations may provide overlooked promotion of plant growth and development16,17. Generally positive effects of priming by bacteria and fungi have been reported in Arabidopsis (Figs 1–4), confirming the potential to use microorganisms commercially for priming plants’ defences, as knowledge of the specificity and strength of various organisms’ effects increases.

Our meta-analyses suggest that defence priming by certain groups of organisms may provide better general protection than others. Fungi appear as the stronger of the tested organismal priming agents in Arabidopsis (Figs 1 and 3b), and bacteria follow closely (Fig. 3a). Organismal priming may offer some advantages over use of chemicals. For example, cold season tall fescue grasses that host defensive endophytic symbionts (Neotyphodium) have selective advantages in the presence of herbivores51, illustrating the potential importance of associated organisms for mutual protection. There is increasing awareness that the microbiota associated with plants is constantly filtered by the taxa, organs, and developing tissues present16. Moreover, plants and associated organisms share both semiochemical signals17,19,52 and evolutionary histories53–55. Unravelling such relationships and exploiting them for plant production may offer environmentally sound agricultural strategies. The diversity of natural interactions and associations is vast but increasing knowledge of the patterns involved is enhancing our ability to recognize and apply them8,10,56.

Organismal priming: Herbivores

As evidenced by meta-analyses, herbivores appear as generally weak priming agents (Figs 1 and 3c). Higher organisms induce defences in plants, as they give rise to immediate activation of defensive pathways and upregulated pools of specialised defence products57,58. Long-lasting trans-generational resistance shaped by herbivory has also been documented in Arabidopsis and tomato by Rasmann, et al.12. Our meta-analyses indicate that herbivores are generally weak priming agents (Figs 1 and 3c), although they induce immediate activation of defensive pathways and upregulation of pools of specialised defence products57,58. Internal herbivore feeders (e.g. miners and gallers) have more intimate associations with their hosts, but maintaining them in culture for experimental purposes is demanding, which may explain the scarcity of mechanistic and detailed studies of their impact on defence priming in the literature.

In addition, any reported priming of Arabidopsis plants included in our meta-analyses had weak anti-herbivory effects. In contrast, several studies found that seed priming effectively prevented herbivory in various crop systems (Table 1 and references herein, also see Rasmann, et al.12). Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that the success of priming treatments against herbivore attacks may depend on the developmental stage at which they are applied to plants.

Non-organismal chemical priming: Vitamins

Vitamins are strong chemical priming agents according to our meta-analyses (Fig. 1). Moreover, they are essential, natural organic substances and many have additional defensive functions in planta. Hence, they have commercially appealing properties for priming purposes, including non-phytotoxicity and potentially growth-stimulating properties (Table 1), and B vitamins in particular are widely used as priming agents59–62.

Thiamine (vitamin B1) is an antioxidant produced by plants, bacteria, and fungi60,63. It naturally functions as a coenzyme in several metabolic pathways, including the Krebs cycle, glycolysis, and pentose phosphate pathway63,64. In Arabidopsis, Tunc-Ozdemir, et al.64 found that various stress treatments (cold, salt and paraquat) led to accumulation of thiamine, accompanied following paraquat treatment with reduced production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Observations of enhanced defence responses to infection by Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato bacteria in various plants following foliar applications of thiamine confirmed that it has diverse, species- and genotype-specific priming effects24,65. When applied to seeds, thiamine also enhances resistance of several crops (including pea, barley, oat, wheat, and millet) against aphid pests27,66 and fungal infections62.

Vitamin-B2 (riboflavin) is also produced naturally in plants, but its effects as a priming agent have not been frequently tested. However, Azami-Sardooei, et al.67 reported that priming with B2 enhanced resistance to the pathogen B. cinerea in bean but not tomato plants. The authors cited argue that the latter may have been insensitive to B2 priming because the tomato plants already had sufficient endogenous levels of B2, lacked riboflavin receptors, or were unable to absorb it adequately.

Vitamin B3 is another natural metabolite in plants, niacin, that has frequently been used to prime plants. More strictly, niacin refers to nicotinamide and the closely related nicotinic acid (also with B3 activity). Nicotinamide is released by the enzyme poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) in response to oxidative stress causing single-strand breaks in DNA68,69. Thus, as it is formed during oxidative stress, it putatively functions as a general signal and stress response59. Plants primed with B3, in either nicotinic acid or nicotinamide forms70, reportedly have enhanced resistance to both subsequent biotic26,61 and abiotic26,71 stressors.

Vitamins B1 and B3 have also been used as priming agents for a range of crops (including barley, wheat, and pea) without causing detectable phenotypic changes. Hamada, et al.27 and Hamada and Jonsson66 found that vitamin B1 protected several crops against aphid attacks, while Berglund, et al.26 found that B3 protected spruce against pine weevils. The lack of detected phenotypic responses to treatment with these agents is very promising as the ideal defence priming agent would have no or minimal performance penalties for the host, compared to unprimed controls22. In our meta-analyses there were too few studies to distinguish between effects of specific vitamins. However, our results confirm that vitamins may be attractive agents for priming plants of various species, applied either in vegetative stages (as in Arabidopsis studies) or seeds (as in studies with assorted non-model crop species).

Non-organismal chemical priming: Defence elicitors

Another potentially strong priming agent is the signalling compound aminobutyric acid isomer BABA (Fig. 4a)20. This is usually present at levels so low that it was only recently proven to be synthesised in highly diverse plant species in response to several kinds of pathogens72. Our meta-analyses show that BABA-priming of Arabidopsis plants has provided strong protection against bacterial diseases and, to a lesser degree, fungal diseases (Fig. 4a,b). Wilkinson, et al.73 also detected strong long-lasting effects of BABA against Botrytis cinerea post-harvest infections in tomatoes with no yield penalty. Elucidation of mechanisms behind these diverse effects may provide highly interesting insights and opportunities.

In contrast to BABA, oligogalacturonides (OGs) appear to have weak priming efficiency against fungal diseases (Fig. 4b). OGs comprise a diverse group of defence signalling molecules that are degradation products of pectin in plants’ cell walls. When disrupted they break into fragments, or so-called Damage Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) that induce plant immune responses via an MPK-dependent pathway74–76. Thus, the finding that OGs did not score highly as priming agents in our analyses was surprising, but may be due to their diversity, and OG specificity may warrant further attention in future studies. Only general effects of OGs have been tested in seven Arabidopsis studies as yet, so it is too early to draw robust conclusions about their potential utility as priming agents.

Priming of plants with jasmonates is highly efficient, and even deters relatively large insects such as pine weevils from de-barking coniferous plants26. Martinez-Medina et al.22 argue that priming may come at an initial cost, that is outweighed by later benefits, but methyl-jasmonate (MeJA) appears to come with fairly high cost because it stunts growth, and causes plants to reallocate resources towards specialized metabolism e.g. terpenoid production in spruce77. Li, et al.78 found that MeJA applications may also cause changes in cuticle thickness and composition, and increases in densities of trichomes and stomata, as well as reductions in height and biomass, in various species (e.g., tomato, sunflower and soybean). Thus, although application of MeJA efficiently enhances herbivore resistance its value as a priming agent is questionable due to its undesirable phenotypic effects.

Previous meta-analyses have shown that green leaf volatiles (GLV) may protect plants against bacterial, fungal and herbivorous antagonists57,79. Despite the evidence of shared cross-kingdom chemical signalling, volatiles (and compounds derived from bacteria and fungi) did not collectively score high as priming agents in our meta-analyses. However, they are also highly heterogenous groups of compounds. Diverse expression-level responses to these compounds have been examined, and they have usually included responses of defence-associated pathways (for example JA or SA pathways) or pathways leading to specialised defence compounds (e.g., phenylpropanoids or glucosinolates, Table 1). Organisms secrete chemicals. Bacteria, for example, produce signaling molecules to regulate transcription and cell population density80 that may affect plant performance. Therefore, the mechanisms behind any organismal or chemical treatments may have shared mechanisms, which motivated a general illustration of efficiency order of all biostimulants included in this study (Fig. S1).

The increasing abundance of information about plants’ responses to stress conditions is rapidly increasing knowledge of the sophisticated metabolic and signalling networks involved in finetuning their defence responses. Understanding these responses and plants’ interactions with associated organisms may undoubtedly facilitate discovery of alternative strategies to protect plants, as noted by various authors10,16,17,53,81. However, the mechanisms involved in diverse responses must be elucidated to enable any generalisations.

Potential bias and sources of error

The quality of the database used in any meta-analysis is a major concern, mainly because publications on any topic may be subject to biases that exaggerate evidence, as significant effects or relationships are more attractive for publication than non-significant effects or relationships82. In our case, a risk of overestimating effects was weakly suggested in the funnel plots (Fig. S3). However, that concern was strongly contradicted by Fail-safe numbers (Table S4), which indicate the number of conflicting studies needed to reject findings of a meta-analysis.

Another potential source of error in meta-analyses lies in the way parameters are chosen. There are endless ways to measure priming effects, due to the diversity of both potential experimental systems (e.g. between non-pathogenic and pathogenic bacteria) and biological settings of priming treatments. There is also often no general agreement between responses that may be dynamic, non-linear and dependent on both spatial and temporal parameters (e.g. when evaluating relationships between gene expression, enzyme activity, and metabolomic changes). Currently we have no general mechanistic understanding of priming, although potential MPK accumulation and epigenetic alterations have been suggested. Any measurable general mechanistic understanding of plant memory would be a huge step forward in assessing and documenting plant priming.

Arabidopsis and general insights

The meta-analyses presented here are based on studies of the model species Arabidopsis thaliana. This is advantageous as it avoids potentially confounding variation in responses due to variations in the host plant, thereby assisting inter-study comparisons. The Col-0 accession, the first model plant to be sequenced was used in more than 85% of the studies included in our database and meta-analyses. Thus, the findings may not be relevant for all plant systems, but Arabidopsis provides a convenient model of higher plants generally, and the Brassicaceae specifically, offering high potential for molecular follow-up studies to unravel mechanisms underlying defence priming41.

Curiously, although diverse plant systems may be primed at the seed stage (Table 1), we identified no studies of defence priming Arabidopsis seeds, so we could only consider aspects of priming this species at the plant stage. Moreover, we identified relatively few studies on priming of seeds of other species, although priming at the seed stage appears to be commercially attractive. This could be due to biased knowledge in this field of research, which is often driven by private seed companies83, so knowledge of seed-priming mechanisms could be protected by commercial interests.

Future challenges

Despite advances in knowledge of priming, several challenges must be addressed before priming may be commercially viable84. Reliable priming methods must be established with detailed knowledge about priming strength for relevant crop species, and detailed information about priming stability and reliability will be expected by the customers. Successful priming increases plants’ overall performance under stress21,22,85, and to evaluate priming strength in any experimental test, it is desirable to include both physiological costs and performance benefits. This is not straightforward. Positive effects on yield and negative effects on an antagonist are convincing indications of successful priming, but bioassays are costly and elaborate to perform, and demanding to standardize86. A mechanistic understanding of priming might indicate convenient and cost-effective ways to assess priming. Assessments of MPK accumulation and epigenetic responses (DNA methylation/demethylation and histone modifications) are promising possibilities. However, they cannot stand alone and must be calibrated according to plant and antagonist performance.

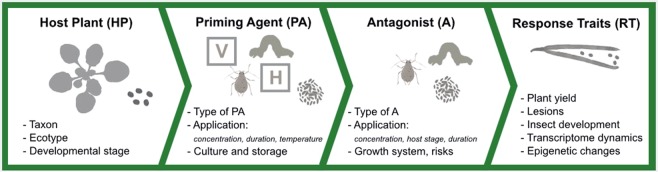

A priming agent can be applied in diverse ways, e.g. by spraying or submerging seeds, foliage or roots. Seeds have obvious advantages, as they can be treated evenly and precisely with little if any environmental impact or non-target ramifications87. Moreover, in contrast to plant priming, seed priming will also protect plants from the earliest stages of germination and throughout their development. Thus, seed treatment promises to be less labour intensive and more cost-efficient than treatment of plants88. However, the development of robust seed priming procedures will involve several optimization steps, including choices of plant system and priming agents, test conditions, stresses, and responses of both plants and antagonists (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

A hierarchical overview of relevant process elements (referred to in this paper) in the development of chemical and biological seed priming routines. Priming with live organisms involves three-way interactions, and optimisation of screening conditions for both host plant and priming agent may be required. Measured response traits may include variables indicating changes in host performance, symptoms or antagonist performance. Some response traits (e.g. molecular level changes) will require a priori calibration for correct interpretation in terms of costs or benefits for the plant. (Letters in squares refer to vitamins “V” and hormones “H”).

Ugena et al.89 developed a multi-trait high throughput screening method of biostimulants on Arabidopsis seeds to assess effects on growth and germination in response to subsequent salt stress. This work provides a rare resource for characterization of biostimulants towards plant health promotion.

Conclusion

There is an urgent need for sustainable crop protection techniques and seed defence priming appears to be an attractive strategy. However, before it can be commercially applied several aspects, starting with the priming mechanism(s), must be elucidated. Assessments of priming treatments’ persistence (duration of priming effects) and the range of biotic stresses they may protect against are also warranted. The meta-analyses presented here convincingly show that priming has general potential for raising crop productivity. This is increasingly important as our agricultural systems are facing severe challenges including increasing demands, higher costs, and a changing climate.

Material and Methods

Literature search

Literature covering priming of seeds to enhance germination and growth extends back to the 1970s, but relatively few published studies have focused on the priming of seeds’ defences against biotic stress. Strategic searches of databases like Web-of Science detected few relevant papers, which address diverse systems. A much larger body of literature covers defence priming in the plant stage, and we used Web-of-Science to compile a database of these studies in Arabidopsis thaliana (hereafter Arabidopsis) that provides a model for studies of plant biology, and is a suitable study system to understand mechanistic responses in plants at the molecular scale41.

Data selection

Seed defence priming

As already mentioned, Web of Science searches identified relatively few studies on defence priming in seeds. For example, a search for papers on the Topics seed priming AND biotic stress on 27 July 2018 resulted in 31 papers, published from 2009–2018 including 20 published in 2012–2018 that addressed seed priming. Of the latter, 15 covered enhancement of resistance to abiotic stress and just four documented defence priming against pathogens. Host plants considered in those 20 studies were mainly crops such as rice, barley, wheat, maize, tomato, onion, corn and Brassica species, and only four included defence priming with use of a specific compound (beta-aminobutyric acid, BABA) or pathogen (Trichoderma or a hemibiotrophic pathogen). The search also listed a few reviews on, for example, uses of macro-algal compounds as agricultural bio-stimulants90. Back-tracing through such reviews, as described for example by18,60, was a more rewarding search strategy, resulting in identification of most of the studies on defence priming in seeds listed in Table 1 (see List S6 for references).

Plant defence priming

To cover defence priming of Arabidopsis plants, we searched the Web of Science for documents of Article type in the Category Plant Sciences on the Topics Arabidopsis AND priming. This resulted in 509 hits (collected on the 17th and 18th of April 2018). An additional search for Articles in the Category Plant Sciences with Arabidopsis in the title on the Topics treatm* AND resistance AND plant defen?e resulted in 326 more hits (collected on the 2nd and 3rd of May 2018). Thus, the resulting database included 835 articles.

Papers that mentioned Arabidopsis as a main study organism in the title, abstract or author keywords were then selected. Fifty of the discarded papers were randomly chosen for quality checking, and scrutinised to verify that they did not include data on responses of Arabidopsis that should have been included according to the data selection criteria. Thus, although a few studies may have been overlooked by chance, we judge that the database is rich enough to fulfil the purpose of this study.

Next, in order to extract usable information from the identified papers, each reported study was examined and retained if:

It included experiments with a priming agent and a wild-type population of any specified ecotype of Arabidopsis thaliana. Priming and tests with any kinds of organs or tissues (e.g. seeds, plants, or roots) were allowed.

The priming agent was organismal (e.g., a herbivore, bacterium, fungus, or pathogen effector), or plant-related elicitor, e.g., beta aminobutyric acid (BABA), or flagellin (flg22), a plant hormone related to biotic stress, e.g., jasmonic acid (JA, or its methyl derivative, MeJA) or salicylic acid (SA), or any vitamin.

Experiments were detailed and information about the priming agent (its kind, concentration, treatment duration etc) was included.

Responses to any kinds of biotic stresses (e.g. any herbivore, bacterium, fungus or virus) were detailed, but not responses to un-groupable stress agents (e.g. singletons, oomycota or transgenic stresses).

The study provided information about both primed and unprimed plants, statistical data about their responses (averages and standard deviations, standard errors or confidence intervals), and sample sizes, as well as resistance effects in terms of quantified pest/pathogen performance. Experiments that solely quantified Arabidopsis defence responses (e.g. gene expression, metabolite accumulation, etc.) were excluded. Papers indicating pathogen performance based solely on use of RT-PCR and ELISA were also excluded (ca. eight papers were excluded on these grounds). Studies providing information on behavioural responses of herbivores, for example, data on feeding responses of aphids obtained using electrical penetration graphs showing durations and frequencies of phloem phase were included.

Experiments were not included if:

The authors had not specified treatments of the primed or control plants (regarding, for example, concentrations/amounts of primer used), or information about types of errors was incomplete.

Effects of an abiotic stress such as salt stress or drought, or the highly specific agents ethylene, abscisic acid (ABA), coroatine, catechol, silicon, quinolinate, mycotoxins, transgenic bacterial strains, and volatiles or exudates produced by transgenic plants were defined or regarded as priming agents.

Priming treatments included use of NADPH oxidase inhibitors (e.g. DPI), H2O2 scavengers (e.g. catalase), a mETC uncoupler (e.g. antimycin or rotenone), nitric oxide inhibitors (e.g. cPTIO, L-NAME and OA) or BABA-inhibitors (e.g. L-Glutamine).

Several priming agents, for instance two compounds, were combined.

They were intended to determine active components or sizes of the priming agent (e.g. via use of proteases or deacetylases).

Transgenerational priming was tested.

Data extraction

Mean values and variances of resistance data were extracted from tables and figures in the remaining studies and listed according to priming agent and antagonist. The plugin “Figure Calibration” in ImageJ, available at: http://www.astro.physik.uni-goettingen.de/hessman/ImageJ/, was used to obtain data from plots when numbers were not available. If sample sizes were given as a range (e.g. 20–25 replicates), the lowest number was listed. If the resolution of a figure was too low to extract data, the study was excluded.

If a primer’s effects at several concentrations and/or time points were tested in an experiment, data pertaining to the strongest effect (positive or negative) were included. Bacterial growth assays presented at log-scale were log-transformed after data extraction. Repeated experiments were included if they were independent of each other. Effect size (Hedge’s g) was calculated using Rstudio as described by Del Re91.

If several parameters (e.g. bacterial growth and disease severity) of individuals were measured, the effect sizes obtained were aggregated into a single effect size according to the “BHHR” procedure91. After aggregation, 267 experiments described in 77 papers remained and were included in the database, and subsequent meta-analyses. Responses quantified in these experiments included lesion area, feeding damage, bacterial growth, infection, disease severity, spore production, feeding duration, population increase, herbivore weight, time to pupation and/or reproduction rate. The studies reporting these experiments are listed in the Supplementary Information (List S5). Funnel plots and Fail-safe numbers, indicating how many conflicting studies would be needed to reject the outcome of a meta-analysis, are also reported in the Supplementary Information (Fig. S3 and Table S4) in agreement with use of Funnel plots and Fail-safe numbers92,93.

After calculating the effect sizes, the experiments were divided into classes depending on the type of priming (Bacteria, Fungi, Herbivores, Chemicals, Hormones or Vitamins, with further division into sub-classes such as JA, SA, or B1) and biotic stressor (bacterial, fungal, herbivore, or viral) applied.

Statistical analyses

QQ-plot and Shapiro tests were used to assess the normality of data distributions. The variance of the data was assessed with F- or Levene’s tests. When comparing two groups, statistical analyses were performed using the parametric Student’s t-test (with equal or unequal variance settings depending on the outcome from the variance test) and nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests (for datasets with sufficiently equal and unequal variance, respectively). If more than two groups were compared, statistical analysis were performed using One-way ANOVA for normally distributed data and Kruskal Wallis tests for non-normally distributed data. Pairwise comparison after the Kruskal Wallis test was performed using post-hoc Dunn’s tests (with Benjamini-Hochberg methodology for P-value adjustment). A significance threshold of 0.05 was applied in all tests. R version 3.4.2 was used for all analyses and generating all plots.

Ethical and third parts issues do not apply to this submission as no experiments were performed and no copying of any material included.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The present paper was the result of the masters’ thesis by Sara M. Westman. We thank two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments. The authors associated with the Umeå Plant Science Centre were supported by the UPSC Centre for Forest Biotechnology and BRA was supported by the TC4F (Trees and Crops for the Future) both with financial support by the Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems – VINNOVA.

Author Contributions

B.A. initiated the present study; S.W. collected data and performed all analyses. B.A. wrote the paper together with S.W. and all authors (K.K., A.O. and J.H.) commented on and greatly took part in developing the manuscript. In particular: K.K. created Figure 5 and carefully reviewed parts about plant defence responses, A.O. was responsible for careful reviewing the molecular priming mechanisms, and J.H. carefully reviewed parts about seed biology.

Data Availability

The data of this study is based on extracts from published papers available through scientific citation data bases, and it is available as open access on-line data https://springernature.figshare.com/s/19070f9acfb5182cce0b. Lists of references that were included to compile the data base are available in the up-loaded supplemental material document included in the submission.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-49811-9.

References

- 1.Alavanja MCR. Pesticides Use and Exposure Extensive Worldwide. Reviews on environmental health. 2009;24:303–309. doi: 10.1515/REVEH.2009.24.4.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borlaug NE. Ending world hunger. The promise of biotechnology and the threat of antiscience zealotry. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:487–490. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.2.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aktar MW, et al. Impact assessment of pesticide residues in fish of Ganga river around Kolkata in West Bengal. Environ Monit Assess. 2009;157:97–104. doi: 10.1007/s10661-008-0518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oerke EC. Crop losses to pests. J Agr Sci. 2006;144:31–43. doi: 10.1017/S0021859605005708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FAO. International Code of Conduct on the Distribution and Use of Pesticides. (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2010).

- 6.EC-Directive. In Official Journal of the European Union (ed the European Parliament), (10.3000/17252555.L_2009.309.eng, 2009/128/EC).

- 7.Montesinos E. Development, registration and commercialization of microbial pesticides for plant protection. Int Microbiol. 2003;6:245–252. doi: 10.1007/s10123-003-0144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barzman M, et al. Eight principles of integrated pest management. Agron Sustain Dev. 2015;35:1199–1215. doi: 10.1007/s13593-015-0327-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albrectsen, B. R. & Witzell, J. In Fungi: Types, Environmental Impact and Role in Disease (ed Maria Sol Adolfo Paz Silva) 235–246 (Nova Science Publishers, 2012).

- 10.Biere A, Bennett AE. Three-way interactions between plants, microbes and insects. Funct Ecol. 2013;27:567–573. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruce TJA, Matthes MC, Napier JA, Pickett JA. Stressful “memories” of plants: Evidence and possible mechanisms. Plant Sci. 2007;173:603–608. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2007.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasmann S, et al. Herbivory in the Previous Generation Primes Plants for Enhanced Insect Resistance. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:854–863. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.187831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulz B, Boyle C. The endophytic continuum. Mycol Res. 2005;109:661–686. doi: 10.1017/S095375620500273x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Innerebner G, Knief C, Vorholt JA. Protection of Arabidopsis thaliana against Leaf-Pathogenic Pseudomonas syringae by Sphingomonas Strains in a Controlled Model System. Appl Environ Microb. 2011;77:3202–3210. doi: 10.1128/Aem.00133-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jogaiah S, Abdelrahman M, Tran LSP, Shin-ichi I. Characterization of rhizosphere fungi that mediate resistance in tomato against bacterial wilt disease. J Exp Bot. 2013;64:3829–3842. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bai Y, et al. Functional overlap of the Arabidopsis leaf and root microbiota. Nature. 2015;528:364–369. doi: 10.1038/nature16192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang YX, Ruyter-Spira C, Bouwmeester HJ. Engineering the plant rhizosphere. Curr Opin Biotech. 2015;32:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song, G. C., Choi, H. K., Kim, Y. S., Choi, J. S. & Ryu, C. M. Seed defense biopriming with bacterial cyclodipeptides triggers immunity in cucumber and pepper. Sci Rep-Uk7, 10.1038/s41598-017-14155-9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Song LX, et al. Brassinosteroids act as a positive regulator for resistance against root-knot nematode involving RESPIRATORY BURST OXIDASE HOMOLOG-dependent activation of MAPKs in tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41:1113–1125. doi: 10.1111/pce.12952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Worrall D, et al. Treating seeds with activators of plant defence generates long-lasting priming of resistance to pests and pathogens. New Phytol. 2012;193:770–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilker M, et al. Priming and memory of stress responses in organisms lacking a nervous system. Biol Rev. 2016;91:1118–1133. doi: 10.1111/brv.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez-Medina A, et al. Recognizing Plant Defense Priming. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21:818–822. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mauch-Mani B, Baccelli I, Luna E, Flors V. Defense Priming: An Adaptive Part of Induced Resistance. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2017;68:485–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042916-041132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahn IP, Kim S, Lee YH. Vitamin B-1 functions as an activator of plant disease resistance. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1505–1515. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.058693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beckers GJ, Conrath U. Priming for stress resistance: from the lab to the field. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10:425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berglund T, Lindstrom A, Aghelpasand H, Stattin E, Ohlsson AB. Protection of spruce seedlings against pine weevil attacks by treatment of seeds or seedlings with nicotinamide, nicotinic acid and jasmonic acid. Forestry. 2016;89:127–135. doi: 10.1093/forestry/cpv040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamada AM, Fatehi J, Jonsson LMV. Seed treatments with thiamine reduce the performance of generalist and specialist aphids on crop plants. Bull Entomol Res. 2018;108:84–92. doi: 10.1017/S0007485317000529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beckers GJM, et al. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases 3 and 6 Are Required for Full Priming of Stress Responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2009;21:944–953. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.062158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conrath U. Molecular aspects of defence priming. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:524–531. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Espinas, N. A., Saze, H. & Saijo, Y. Epigenetic Control of Defense Signaling and Priming in Plants. Front Plant Sci7, 10.3389/fpls.2016.01201 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Jaskiewicz M, Conrath U, Peterhansel C. Chromatin modification acts as a memory for systemic acquired resistance in the plant stress response. Embo Rep. 2011;12:50–55. doi: 10.1038/embor.2010.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen ZJ, Tian L. Roles of dynamic and reversible histone acetylation in plant development and polyploidy. Bba-Gene Struct Expr. 2007;1769:295–307. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez Sanchez A, Stassen JH, Furci L, Smith LM, Ton J. The role of DNA (de)methylation in immune responsiveness of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2016;88:361–374. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones JDG, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macel M, van Dam NM, Keurentjes JJB. Metabolomics: the chemistry between ecology and genetics. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010;10:583–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pieterse CMJ, der Does V, Zamioudis D, Leon-Reyes C, Van Wees A. S. C. M. Hormonal Modulation of Plant Immunity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Bi. 2012;28:489–521. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aziz, M. et al. Augmenting Sulfur Metabolism and Herbivore Defense in Arabidopsis by Bacterial Volatile Signaling. Front Plant Sci7, 10.3389/fpls.2016.00458 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Elsharkawy MM, Shimizu M, Takahashi H, Hyakumachi M. Induction of systemic resistance against Cucumber mosaic virus by Penicillium simplicissimum GP17-2 in Arabidopsis and tobacco. Plant Pathol. 2012;61:964–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2011.02573.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hossain MM, Sultana F, Hyakumachi M. Role of ethylene signalling in growth and systemic resistance induction by the plant growth-promoting fungus Penicillium viridicatum in Arabidopsis. J Phytopathol. 2017;165:432–441. doi: 10.1111/jph.12577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hossain MM, Sultana F, Kubota M, Hyakumachi M. Differential inducible defense mechanisms against bacterial speck pathogen in Arabidopsis thaliana by plant-growth-promoting-fungus Penicillium sp GP16-2 and its cell free filtrate. Plant Soil. 2008;304:227–239. doi: 10.1007/s11104-008-9542-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koornneef M, Meinke D. The development of Arabidopsis as a model plant. Plant J. 2010;61:909–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aziz A, et al. Effectiveness of beneficial bacteria to promote systemic resistance of grapevine to gray mold as related to phytoalexin production in vineyards. Plant Soil. 2016;405:141–153. doi: 10.1007/s11104-015-2783-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elsharkawy MM, Shimizu M, Takahashi H, Hyakumachi M. The plant growth-promoting fungus Fusarium equiseti and the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus mosseae induce systemic resistance against Cucumber mosaic virus in cucumber plants. Plant Soil. 2012;361:397–409. doi: 10.1007/s11104-012-1255-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hossain MD, et al. Differential enzymatic defense mechanisms in leaves and roots of two true mangrove species under long- term salt stress. Aquat Bot. 2017;142:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2017.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barbosa P, et al. Associational Resistance and Associational Susceptibility: Having Right or Wrong Neighbors. Annu Rev Ecol Evol S. 2009;40:1–20. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friesen ML, et al. Microbially Mediated Plant Functional Traits. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 2011;42:23–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jung SC, Martinez-Medina A, Lopez-Raez JA, Pozo MJ. Mycorrhiza-Induced Resistance and Priming of Plant Defenses. J Chem Ecol. 2012;38:651–664. doi: 10.1007/s10886-012-0134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Busby PE, et al. Genetics-based interactions among plants, pathogens, and herbivores define arthropod community structure. Ecology. 2015;96:1974–1984. doi: 10.1890/13-2031.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Busby PE, Peay KG, Newcombe G. Common foliar fungi of Populus trichocarpa modify Melampsora rust disease severity. New Phytol. 2016;209:1681–1692. doi: 10.1111/nph.13742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kenigsvalde K, et al. Evaluation of the biological control agent Rotstop in controlling the infection of spruce and pine stumps by Heterobasidion in Latvia. Scand J Forest Res. 2016;31:254–261. doi: 10.1080/02827581.2015.1085081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clay K, Holah J, Rudgers JA. Herbivores cause a rapid increase in hereditary symbiosis and alter plant community composition. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12465–12470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503059102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jelenska J, Davern SM, Standaert RF, Mirzadeh S, Greenberg JT. Flagellin peptide flg22 gains access to long-distance trafficking in Arabidopsis via its receptor, FLS2. J Exp Bot. 2017;68:1769–1783. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gourbal B, et al. Innate immune memory: An evolutionary perspective. Immunol Rev. 2018;283:21–40. doi: 10.1111/imr.12647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kohler A, et al. Convergent losses of decay mechanisms and rapid turnover of symbiosis genes in mycorrhizal mutualists. Nat Genet. 2015;47:410–415. doi: 10.1038/ng.3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tisserant E, et al. Genome of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus provides insight into the oldest plant symbiosis. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:20117–20122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313452110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumar S, Kumari R, Sharma V. Transgenerational Inheritance in Plants of Acquired Defence Against Biotic and Abiotic Stresses: Implications and Applications. Agr Res. 2015;4:109–120. doi: 10.1007/s40003-015-0170-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ameye M, et al. Priming of Wheat with the Green Leaf Volatile Z-3-Hexenyl Acetate Enhances Defense against Fusarium graminearum But Boosts Deoxynivalenol Production. Plant Physiol. 2015;167:1671–1684. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karban R, Agrawal AA, Thaler JS, Adler LS. Induced plant responses and information content about risk of herbivory. Trends Ecol Evol. 1999;14:443–447. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01678-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berglund T. Nicotinamide, a Missing Link in the Early Stress-Response in Eukaryotic Cells - a Hypothesis with Special Reference to Oxidative Stress in Plants. Febs Lett. 1994;351:145–149. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00850-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boubakri H, et al. Vitamins for enhancing plant resistance. Planta. 2016;244:529–543. doi: 10.1007/s00425-016-2552-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pushpalatha HG, et al. Ability of vitamins to induce downy mildew disease resistance and growth promotion in pearl millet. Crop Prot. 2007;26:1674–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2007.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pushpalatha HG, Sudisha J, Geetha NP, Amruthesh KN, Shetty HS. Thiamine seed treatment enhances LOX expression, promotes growth and induces downy mildew disease resistance in pearl millet. Biol Plantarum. 2011;55:522–527. doi: 10.1007/s10535-011-0118-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goyer A. Thiamine in plants: Aspects of its metabolism and functions. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:1615–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tunc-Ozdemir M, et al. Thiamin Confers Enhanced Tolerance to Oxidative Stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:421–432. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.140046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ahn IP, Kim S, Lee YH, Suh SC. Vitamin B-1-induced priming is dependent on hydrogen peroxide and the NPR1 gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:838–848. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.092627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hamada AM, Jonsson LMV. Thiamine treatments alleviate aphid infestations in barley and pea. Phytochemistry. 2013;94:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Azami-Sardooei Z, Franca SC, De Vleesschauwer D, Hofte M. Riboflavin induces resistance against Botrytis cinerea in bean, but not in tomato, by priming for a hydrogen peroxide-fueled resistance response. Physiol Mol Plant P. 2010;75:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pmpp.2010.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Briggs Amy G., Adams-Phillips Lori C., Keppler Brian D., Zebell Sophia G., Arend Kyle C., Apfelbaum April A., Smith Joshua A., Bent Andrew F. A transcriptomics approach uncovers novel roles for poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in the basal defense response in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(12):e0190268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vriet C, Hennig L, Laloi C. Stress-induced chromatin changes in plants: of memories, metabolites and crop improvement. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:1261–1273. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1792-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sasamoto H, Ashihara H. Effect of nicotinic acid, nicotinamide and trigonelline on the proliferation of lettuce cells derived from protoplasts. Phytochem Lett. 2014;7:38–41. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2013.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ohlsson AB, Landberg T, Berglund T, Greger M. Increased metal tolerance in Salix by nicotinamide and nicotinic acid. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2008;46:655–664. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thevenet D, et al. The priming molecule beta-aminobutyric acid is naturally present in plants and is induced by stress. New Phytol. 2017;213:552–559. doi: 10.1111/nph.14298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wilkinson SW, Pastor V, Paplauskas S, Petriacq P, Luna E. Long-lasting -aminobutyric acid-induced resistance protects tomato fruit against Botrytis cinerea. Plant Pathol. 2018;67:30–41. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ferrari, S. et al. Oligogalacturonides: plant damage-associated molecular patterns and regulators of growth and development. Front Plant Sci4, 10.3389/fpls.2013.00049 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Galletti R, Ferrari S, De Lorenzo G. Arabidopsis MPK3 and MPK6 Play Different Roles in Basal and Oligogalacturonide- or Flagellin-Induced Resistance against Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:804–814. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.174003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vorwerk S, Somerville S, Somerville C. The role of plant cell wall polysaccharide composition in disease resistance. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sampedro L, Moreira X, Zas R. Resistance and response of Pinus pinaster seedlings to Hylobius abietis after induction with methyl jasmonate. Plant Ecol. 2011;212:397–401. doi: 10.1007/s11258-010-9830-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li C, Wang P, Menzies NW, Lombi E, Kopittke PM. Effects of methyl jasmonate on plant growth and leaf properties. J Plant Nutr Soil Sc. 2018;181:409–418. doi: 10.1002/jpln.201700373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ameye Maarten, Allmann Silke, Verwaeren Jan, Smagghe Guy, Haesaert Geert, Schuurink Robert C., Audenaert Kris. Green leaf volatile production by plants: a meta-analysis. New Phytologist. 2017;220(3):666–683. doi: 10.1111/nph.14671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Whiteley M, Diggle SP, Greenberg EP. Progress in and promise of bacterial quorum sensing research. Nature. 2017;551:313–320. doi: 10.1038/nature24624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tugizimana, F., Mhlongo, M. I., Piater, L. A. & Dubery, I. A. Metabolomics in Plant Priming Research: The Way Forward? Int J Mol Sci19 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Peters JL, et al. Assessing publication bias in meta-analyses in the presence of between-study heterogeneity. J R Stat Soc a Stat. 2010;173:575–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2009.00629.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pedrini S, Merritt DJ, Stevens J, Dixon K. Seed Coating: Science or Marketing Spin? Trends Plant Sci. 2017;22:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Paparella S, et al. Seed priming: state of the art and new perspectives. Plant Cell Rep. 2015;34:1281–1293. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1784-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.van Hulten M, Pelser M, van Loon LC, Pieterse CMJ, Ton J. Costs and benefits of priming for defense in Arabidopsis. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5602–5607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510213103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schmidt L, Schurr U, Rose USR. Local and systemic effects of two herbivores with different feeding mechanisms on primary metabolism of cotton leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 2009;32:893–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen K, Arora R. Priming memory invokes seed stress-tolerance. Environ Exp Bot. 2013;94:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2012.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sharma KK, Singh US, Sharma P, Kumar A, Sharma L. Seed treatments for sustainable agriculture-A review. Journal of Applied and Natural Science. 2015;7:521–539. doi: 10.31018/jans.v7i1.641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ugena, L. et al. Characterization of Biostimulant Mode of Action Using Novel Multi-Trait High-Throughput Screening of Arabidopsis Germination and Rosette Growth. Front Plant Sci9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.Sharma HSS, Fleming C, Selby C, Rao JR, Martin T. Plant biostimulants: a review on the processing of macroalgae and use of extracts for crop management to reduce abiotic and biotic stresses. J Appl Phycol. 2014;26:465–490. doi: 10.1007/s10811-013-0101-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Del Re AC. A Practical Tutorial on Conducting Meta-Analysis in R. Quant Meth Psychol. 2015;11:37–50. doi: 10.20982/tqmp.11.1.p037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rowen E, Kaplan I. Eco-evolutionary factors drive induced plant volatiles: a meta-analysis. New Phytol. 2016;210:284–294. doi: 10.1111/nph.13804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Viechtbauer W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v036.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study is based on extracts from published papers available through scientific citation data bases, and it is available as open access on-line data https://springernature.figshare.com/s/19070f9acfb5182cce0b. Lists of references that were included to compile the data base are available in the up-loaded supplemental material document included in the submission.