Abstract

Objectives

We sought to understand the implementation of multifaceted community plans to address opioid-related harms.

Design

Our scoping review examined the extent of the literature on community plans to prevent and reduce opioid-related harms, characterise the key components, and identify gaps.

Data sources

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINHAL, SocINDEX and Academic Search Primer, and three search engines for English language peer-reviewed and grey literature from the past 10 years.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible records addressed opioid-related harms or overdose, used two or more intervention approaches (eg, prevention, treatment, harm reduction, enforcement and justice), involved two or more partners and occurred in an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development country.

Data extraction and synthesis

Qualitative thematic and quantitative analysis was conducted on the charted data. Stakeholders were engaged through fourteen interviews, three focus groups and one workshop.

Results

We identified 108 records that described 100 community plans in Canada and the USA; four had been evaluated. Most plans were provincially or state funded, led by public health and involved an average of seven partners. Commonly, plans used individual training to implement interventions. Actions focused on treatment and harm reduction, largely to increase access to addiction services and naloxone. Among specific groups, people in conflict with the law were addressed most frequently. Community plans typically engaged the public through in-person forums. Stakeholders identified three key implications to our findings: addressing equity and stigma-related barriers towards people with lived experience of substance use; improving data collection to facilitate evaluation; and enhancing community partnerships by involving people with lived experience of substance use.

Conclusion

Current understanding of the implementation and context of community opioid-related plans demonstrates a need for evaluation to advance the evidence base. Partnership with people who have lived experience of substance use is underdeveloped and may strengthen responsive public health decision making.

Keywords: opioids, overdose, scoping review, community-based

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our systematic search of the literature included six electronic databases, three internet search engines, reference lists and referrals of unpublished sources; however, records could have been missed due to restrictions on date, language and the number of grey literature references reviewed.

The potential use of these findings in practice is strengthened by our engagement of stakeholders to add perspective to the design and interpretation of our scoping review.

Most opioid-related response plans were from urban communities in the USA and may not be applicable to other contexts; our scoping review did not analyse how plans varied by the context in each community.

Background

In Canada and the United States, opioid-related deaths continue to reach annual record-setting levels.1 2 Many communities have developed comprehensive opioid-related plans including a range of prevention, treatment, harm reduction and enforcement or justice interventions across multiple socioecological levels and involving multiple sectors. Community action ‘involves deliberate organization of community members to accomplish some objective or goal’3 and is a key public health strategy4 for substance use prevention and health promotion and cited for reducing alcohol-related harms.5–7 Throughout this paper, we refer to ‘plan’ as community-based, multistrategy, multisectoral approaches to prevent or reduce opioid-related harms.

To date, few studies have evaluated community opioid-related plans, and those that have been evaluated have demonstrated mixed results in preventing or reducing opioid-related harms. Evaluative research on Project Lazarus in North Carolina, a community-based initiative that involves seven strategies to address opioid overdose, observed a non-significant reduction in opioid deaths between 2009 and 2010 when it originated in Wilkes County,8 and at the state level, unexpected increases in mortality were associated with some of the intervention components.9 Several other communities have released comprehensive action plans,10 11 and a public health guide for local response planning on opioid-related harms has been introduced.12 Yet, there is little information that describes the development, implementation and evaluation of these plans to enable public health practice and improve health outcomes.

Our scoping review sought to address the following research question: what is the scope of the literature on community-based interventions to prevent and reduce population-level harms related to opioids? A scoping review methodology was undertaken due to the broad nature of the literature. Though the definition of ‘community’ varies within public health, in this paper, it refers to a local or regional geographic location.13 Our objectives were to examine the extent of the peer-reviewed and grey literature on community opioid-related plans, characterise the key components and identify gaps for future research and evaluation.

Methods

Our methodological approach followed the six-staged framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley14 and refined by Levac et al 15 and the Joanna Briggs Institute.16 Our reporting conforms to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standards for scoping reviews.17 The review protocol was not registered; however, the protocol was peer reviewed as part of the grant approval process.

Search strategy

In March 2018, our research librarian (SM) developed the search strategy for peer-reviewed English language publications dated after 2008. This period is most relevant to the current context of opioid-related harms and prior to the original publication of the first and most well-known community response, Project Lazarus, in 2011. We searched six electronic databases: MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINHAL, SocINDEX and Academic Search Primer, with terms including, ‘community networks’ OR ‘multi-component or multi-faceted’ AND ‘drug overdose’ OR ‘substance-related disorders’ OR ‘prescription misuse’ (see online supplement 1).

bmjopen-2018-028583supp001.pdf (33.7KB, pdf)

The search strategy developed for the peer-reviewed literature was adapted for the grey literature, and the searches were performed in Google and two of Google’s custom search engines. For each search query, the first 100 results were reviewed. An additional Indigenous-specific search strategy was developed to locate records relevant to Indigenous contexts. This strategy was included because of the disproportionate burden of opioid-related harms among Indigenous groups18 and need to identify how community plans consider Indigenous people. The electronic searches were supplemented by citation searching, referrals from the research team and consulting with stakeholders for relevant documents.

Study selection

To capture relevant community plans, eligible records were those describing plans that: (1) addressed opioid-related harms or overdose at the community level; (2) involved interventions within at least two pillars of the Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy (CDSS) (prevention, treatment, harm reduction and enforcement interventions)19; (3) included interventions that involved two or more partner organisations; and (4) occurred in an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development member country. The CDSS four-pillar approach to substance use originated in Switzerland in the 1990s20 and has been adopted internationally as a comprehensive approach to address substance use-related harms.

We used these criteria as our unit of interest was comprehensive multistrategy, multisector approaches rather than organisations working independently on isolated interventions. We included both community-wide and smaller community-based initiatives that included multisector partners and integrated strategies from at least two pillars. Additionally, provincial/state plans were included if local implementation was discussed or if the province/state was small in geographic size and population (eg, Rhode Island). Records were excluded if community plans: (1) were not opioid or overdose-specific strategies; (2) included partners or interventions from only one pillar of the CDSS19; and (3) occurred exclusively in a specific setting (eg, emergency department or prison). Two reviewers independently completed the title and abstract screening, followed by reviewing the full-text articles. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and involved a third reviewer when needed. Screening of the grey literature and the reference lists of included records followed the same selection process.

Data charting and synthesis

We developed a data extraction spreadsheet available in online supplement 2 for data extraction variables. These included, for example, intervention components (prevention, treatment, harm reduction, enforcement and justice and enabling), community partnerships, community engagement strategies and reported outcomes. We defined enabling components as those that span and support activities across the pillars of the CDSS,19 and examples included surveillance, and approaches to address stigma or other social determinants of health. Our extraction of implementation strategies was guided by the National Implementation Research Network framework (NIRN).21

bmjopen-2018-028583supp002.pdf (23.9KB, pdf)

Two reviewers independently extracted relevant data from a sample of four records in the peer-reviewed and grey literature using a standardised data extraction form. Following pilot testing, data extraction of the peer-reviewed and grey literature was separated and completed by one reviewer, and a sample (20%) was independently verified by an additional reviewer to ensure reliability.

Data extraction was an iterative process and categories were refined, expanded or added based on stakeholder input during consultations. The following categories were added: framing or definition of the problem (eg, prescription opioid and drug overdose), lead agency, funding, data collection sources and system-level outcomes. Furthermore, using a socioecological framework,22 we recharted implementation strategies to capture the ecological level in which they occurred: intrapersonal, interpersonal, organisational, community and policy.

We used a qualitative thematic approach to develop themes from the extracted information and code our findings. The themes were analysed using the data extraction form, and frequencies were calculated for the themes within each data extraction category. Several records discussed similar or multiple plans; thus, frequencies were derived from the number of plans identified rather than the number of included records.

Stakeholder consultations

The consultation phase of our scoping review involved interviews, focus group discussions and a multistakeholder workshop. First, we conducted interviews and focus groups to refine our data extraction strategy to ensure that findings would be relevant and applicable to practice. We recruited a purposive sample of participants that represent diverse perspectives involved in opioid-related responses across Canada and in North Carolina (where Project Lazarus originated as a community action model), including people with lived experience of substance use, family members, researchers, physicians, first responders, public health professionals, and community and social service providers (referred to herein as stakeholders). Participants were contacted via email invitations through the investigators’ professional networks or snowball sampling methods and received a consent form, a project overview and list of interview questions.

Semistructured interviews (n=14) and focus group discussions (n=3; groups that included three to five participants), 30 min to 1 hour in duration, were conducted via telephone or in-person by two researchers (PL and TK). Participants were asked to: (1) describe how the results of the scoping review might be used; (2) provide suggestions on how the results might be best shared with others; and (3) identify additional supports needed to facilitate the uptake of results into practice. All participants provided verbal consent for audio-recording.

Two researchers (PL and TK) independently coded six transcripts and met to discuss and develop the coding framework, which was then applied by one coder (TK) to all transcripts using NVivo 11 software. An inter-rater reliability exercise was completed, whereby a sample of five transcripts was independently coded by a second coder (PL). A sufficient kappa coefficient was achieved (87%).

In our second stage of consultation, we reported the preliminary results of the extracted literature to previously consulted stakeholders at a full-day workshop on 23 July 2018. Forty-five participants from across Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta and North Carolina were brought together to: (1) interpret the results; (2) identify gaps; and (3) describe the implications for practice. Data were collected using notes and posters, and responses from each discussion were summarised by one team member (TK) using thematic analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Our research team included members who work closely with people who have lived experience of substance use (CS, JC, MP and PL) and provided strategic advice on the scoping review design and consultation approach. Interview and focus group consultations included people with lived experience of substance use and family members. These consultations informed our record selection, data extraction and knowledge translation strategies. Furthermore, this group was invited at a later stage as workshop participants to interpret the results, identify gaps and implications of our results for practice. We did not have specific criteria to include people in our research due to their engagement in clinical care (ie, patients).

Results

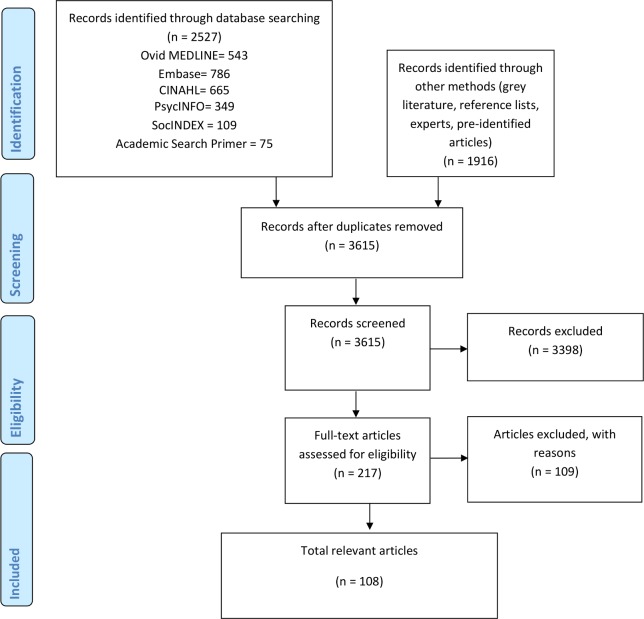

Our literature search resulted in the retrieval of 4443 records, and 3615 records were screened after removing duplicates. Our PRISMA flow diagram is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

A total of 108 records were included,8–11 18 23–125 of which 79 were grey literature references (eg, reports and web pages) (see online supplement 3). From these records, we identified 100 community plans or initiatives from 82 communities and 12 provinces/states, which often encouraged or mandated plan development. Of the 100 plans, 81 were from the USA and the remaining 19 were from Canada. Most community plans referred to actions to address issues of opioid poisoning as the focus of their problem definition (n=57) (see table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of plans

| Characteristics of plans | No. of 100 plans |

| Location | |

| USA | 81 |

| Canada | 19 |

| Level of response implementation | |

| Provincial/state | 15 |

| Municipal/county/regional | 85 |

| Problem definition | |

| Opioid poisoning | 57 |

| Drug poisoning | 3 |

| Heroin poisoning | 2 |

| Prescription drug poisoning | 14 |

| Heroin and opioid poisoning | 16 |

| Other | 8 |

| Lead agency | |

| Province/state | 5 |

| Municipality/county | 11 |

| Public health | 22 |

| Public health co-led | 7 |

| Regional health/health authority | 6 |

| Healthcare including, Local Health Integration Networks | 6 |

| Other | 14 |

| Not specified | 29 |

| Funding | |

| Federal government | 3 |

| Provincial/state government | 26 |

| Municipal/county/local | 3 |

| Non-profit organisation | 10 |

| Other | 11 |

| Not specified | 47 |

| Centralised supports | 9 |

| Not reported | 91 |

| Types of data collected | |

| Coroner data | 22 |

| Local public health data | 23 |

| Emergency medical services data | 15 |

| Hospital data | 22 |

| Prescription monitoring programme data | 16 |

| Law enforcement data | 15 |

| Addiction treatment admissions | 8 |

| None specified | 54 |

| Specific groups considered in interventions | |

| Homeless and housing insecure | 10 |

| People in conflict with the law | 34 |

| Indigenous | 9 |

| Women | 13 |

| Youth | 16 |

| Other | 8 |

| None reported | 47 |

| Community engagement | |

| Survey | 2 |

| Forums | 15 |

| Meeting | 5 |

| Town halls | 6 |

| Other | 6 |

| None reported | 71 |

| Implementation strategies | |

| Training: for example, public and professional training; in-service training for programme delivery | 95 |

| Systems interventions: for example, policy advocacy, developing standards and facilitating intersector collaboration | 83 |

| Coaching: for example, outreach, recovery coaches and consultation | 36 |

| Planning: for example, strategic, financial, advocacy or communications plans; infrastructure | 19 |

| Organisational development: for example, redeploying or hiring employees with certain competencies | 27 |

| Evaluation: for example, establishing targets and collecting data to monitor programmes | 52 |

| Assessment: for example, conducting needs assessments and assessing intervention feasibility | 14 |

| Ecological level of implementation | |

| Intrapersonal: for example, knowledge on the use of opioids or naloxone | 95 |

| Interpersonal: for example, peer support | 27 |

| Organisational/institutional: for example, mandatory workplace policies | 44 |

| Community: for example, collaboration to deliver services, share data and address stigma | 79 |

| Policy: for example, drug policy reform, system-wide guideline implementation | 43 |

bmjopen-2018-028583supp003.pdf (170.2KB, pdf)

Organisation

Leadership

Reports based on 71 plans described the lead agency, which most frequently indicated public health leadership (n=22); an additional seven plans included coleadership by public health and community-based organisations.36 42 61 74 80 103 One plan provided a rationale for public health as an appropriate convener35 and another evaluated the effectiveness of public health leadership.26 Plans were also led by municipal/county-level government (n=11), regional health authorities (n=6),18 51 60 provincial/state governments (n=5),54 56 83 99 123 healthcare organisations (n=6),24 34 79 85 91 115 or others (n=14) (see table 1).

Partnerships

Ninety-one plans discussed members of the partnerships in community plans. Across the 91 plans, a total of 35 different partner groups were represented, and an average of seven partners involved. Most commonly represented partners were healthcare (n=61), law enforcement (n=60), public health (n=44) (see table 2). We found little information on decision-making processes; one plan8 described decision making through the use of advisory committees, although the process for finalising decisions was unclear.

Table 2.

Categorisation of partners in community opioid-related plans

| Sectors | No. of 100 plans |

| Healthcare | 61 |

| Law enforcement | 60 |

| Public health | 44 |

| Government | 40 |

| Addiction treatment services | 40 |

| Non-profit organisations | 36 |

| Mental health services | 32 |

| Corrections | 26 |

| Public | 23 |

| Emergency medical services | 21 |

| Education | 20 |

| Fire services | 16 |

| Harm reduction | 16 |

| Pharmacy | 15 |

| Social services | 15 |

| Recovery services | 14 |

| Antidrug/substance use prevention coalitions | 12 |

| Health services research and evaluation | 11 |

| Indigenous population | 9 |

| Faith-based organisations | 9 |

| Politicians | 8 |

| People with lived experience of substance use | 8 |

| Support and advocacy groups | 7 |

| Youth and youth groups | 7 |

| Private sector | 6 |

| Regional health | 6 |

| Coroners | 4 |

| Community leaders | 4 |

| Health insurance providers | 3 |

| Media | 3 |

| Poison control | 1 |

| Emergency management | 1 |

| Library | 1 |

| Dentists | 1 |

| Military services | 1 |

Funding and centralised support

Fifty-three plans described their direct source of funding for development of plans or service delivery implementation. Often, community opioid-related plans received funds from the province/state (n=26). Ten plans received funding from non-profit organisations and 11 plans described multiple funding sources, including private sector or university grants. Fewer plans were funded federally (n=3)38 122 123 or locally (n=3).46 73 113 Nine plans described a centralised entity, which offered funding and/or technical assistance to support community plans and initiatives.9 35 39 54–56 71 87 99

Theoretical basis

Five plans described the use of the Collective Impact Model126 to inform the organisation and implementation of community action and strategic response planning (n=5).30 35 39 42 70 Additionally, a study on Project Lazarus described the use of a Community Readiness Framework to assess how prepared the community was prior to implementation, based on two behaviour change theories: stages of change model and diffusion of innovation theory.100

Community engagement

Five strategies to engage the community in response planning were identified among 29 plans. These five strategies were described as: in-person community forums (n=15), town halls (n=6),8 9 56 69 76 89 meetings (n=5),56 61 68 97 117 and surveys (n=2).10 125 The range of community members engaged included people with lived experience of substance use (n=8),10 30 37 54 65 68 98 121 family members (n=7)10 37 38 65 80 88 116 and Indigenous people (n=4).10 68 88 121

Plan components

Among the four pillars of the CDSS, treatment components for opioid-use disorder or pain management (n=96) were most common, followed by harm reduction (n=93), prevention (n=58) and enforcement and justice (n=55). Seventy-nine plans included enabling components (n=80) that supported activities across the four pillars. A complete list of categories within each intervention pillar is presented in online supplement 4.

bmjopen-2018-028583supp004.pdf (54.2KB, pdf)

Subgroup and equity considerations

Fifty-three plans included interventions with a specific target population (n=53). Most common were interventions specific to people in conflict with the law (n=34), followed by youth (n=16), women (n=13), people experiencing homelessness (n=10) and Indigenous people (n=9).9 11 51 54 60 68 74 76 85 When Indigenous communities were considered (n=9), plans described the need for culturally appropriate and trauma-informed treatment approaches (eg, land-based healing practices),18 60 68 74 increasing access to either treatment or naloxone among Indigenous communities,51 55 60 76 85 offering Indigenous cultural safety training to health providers,60 Indigenous harm reduction (eg, integrating Indigenous culture into harm reduction practices)60 68 care coordination68 74 and engaging elders in response planning.60

Implementation activities

Using the NIRN framework,21 the categories of implementation activities described in local opioid response plans are summarised in table 1. Most common were training strategies (n=95), often related to overdose prevention, naloxone use and safer prescribing, as well as systems interventions (n=83) (eg, developing standards or collaboration) and evaluation activities (n=52) (eg, establishing data monitoring).

When compared against the socioecological model,22 strategies commonly targeted the individual level (n=95) (eg, knowledge about the use of naloxone), community-level (n=79) (eg, intersectoral collaboration to deliver direct services or share data) or the organisational (n=44) (eg, mandatory workplace policies) (see table 1).

Facilitators and barriers

We identified five common facilitators or barriers impacting community opioid-related plans, among those described or implied (n=67). These included: funding (n=47), stigma (n=22) (eg, experienced in relation to operating and accessing addiction treatment programme), availability of addiction treatment (n=15) (eg, numbers of treatment beds) policies and legislation (n=12) (eg, involving harm reduction services, law enforcement practices) and staffing (n=11).

Data collection and outcomes

Fifty-five plans described data collection and evaluation activities, such as collecting local public health data (n=23), healthcare administrative data (n=22) and coroner reports (n=22).

Four community plans were evaluated (n=4), which included: (1) Project Lazarus that observed a decline in opioid-related mortality and opioid prescribing between 2009 and 2010 in Wilkes County, North Carolina8; (2) the state-wide implementation of the seven intervention components of Project Lazarus found non-significant decreases in opioid overdose mortality associated with provider education and hospital emergency department policies and increases associated with the addiction treatment intervention component9; (3) Staten Island’s five-part response to opioid-related harms observed a decline in opioid-related mortality and opioid prescribing; however, an increased rate of heroin-related overdose deaths occurred89; and (4) centrally funded coalitions in California experienced a greater decrease of opioid prescribing and an increased rate of buprenorphine prescribing compared with non-funded coalitions.35

Stakeholder consultations

From our stakeholder consultations, including 14 interviews, 3 focus groups and a workshop between May and July 2018, we report the major themes that emerged.

Use of the scoping review results

Stakeholders often described their interest in using the scoping review results to identify opportunities to strengthen their own efforts to prevent and reduce opioid-related harms. Learning about practices from other communities was seen by many as a way to understand how to overcome barriers in response planning, how to implement intervention components or integrate innovative approaches to their multistrategy plans. Additionally, several stakeholders described the potential use of the scoping review results for policy and programme advocacy. Locally, some spoke about advocating for community partnerships to involve people with lived experience of substance use.

Stakeholders also described barriers related to response planning, including structural barriers, such as social determinants of health and stigma towards people with lived experience of substance use. Organisational barriers included coordination and collaboration among sector partners, as well as coordinated leadership to spearhead community action.

Gaps in the literature

Workshop participants identified several gaps in the current literature, many of which were also identified in the data extraction phase. The first was a gap in the role and involvement of certain groups in community partnerships responding to opioid-related harms, including the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, two-spirit, intersex and asexual community, family members affected by substance use, pharmacists and representatives from the housing sector. Especially seen as critical was the lack of inclusion of people with lived experience of substance use and community-led or peer-driven approaches.

The second gap concerned the role of context in the literature, including the geographic, sociocultural, economic and political contexts in which plans were implemented. Also noted was a lack of drug policy interventions, approaches that address the social determinants of health, and targeted strategies for at-risk populations (eg, people experiencing homelessness). Lastly, participants noted the gap in evaluative research to support the implementation of community plans as well the use of intervention research to justify the selection of included approaches.

Implications for practice

Three main implications for practice were identified among consultation workshop participants.

First, based on the gaps identified in the literature, improving documentation and evaluation emerged as priorities for practice. Stakeholders recommended actions focused on information sharing, conducting real-time implementation evaluation and building local evaluation capacity. Second, stakeholders also described the need to incorporate strategies to reduce stigma related to people with lived experience of substance use, such as promoting inclusive language use in organisations and workplace antistigma training. Finally, based on the under-representation of certain community partners in the literature, stakeholders suggested improving meaningful partnership with people who have lived experience of substance use, through inclusion of multiple perspectives and providing equitable payment for participation throughout the development, implementation and evaluation of community opioid-related plans

Discussion

Our scoping review synthesised 100 community opioid-related plans described in the peer-reviewed and grey literature. We found that most community opioid-related plans were provincially/state funded, public health-led efforts that involved an average of seven partners, with law enforcement, healthcare and public health sectors commonly represented in partnerships. Most plans employed individual level training as an implementation strategy and focused on treatment and harm reduction approaches to prevent and respond to overdose incidents, particularly increasing the accessibility of addiction treatment and naloxone. Tailored interventions for people in conflict with the law were common, and community forums were used to engage the public in response planning. Overall, there was a lack of representation of Indigenous people in community partnerships as well as intervention approaches.

This scoping review identified several knowledge gaps, all of which were verified and expanded on through our stakeholder consultations. Generally, a very limited body of evidence exists on community opioid-related plans including design, implementation and evaluation. Indeed, the nature of the emerging practice of community opioid-related plans, and the resources required to publish, contribute to the paucity of literature at this time. It is perhaps not surprising that documented evaluations are limited, given the urgency to respond and the difficulty to ascertain the impact of complex multistrategy plans.8 9 35 89 Despite this, conducting and widely sharing rigorous and ongoing evaluation of implementation and outcomes is critical to allow for course corrections and advance the evidence base. In the case of Project Lazarus, state-wide evaluation activities were facilitated by a community-academic partnership,8 and lessons learnt were documented and shared with other community coalitions.33 These strategies may be helpful for other communities to engage in evaluation and learn from the experience of others.

There were few descriptions of how interventions were identified or sustained, how implementation was approached or who was involved and in what sociocultural and political contexts plans took place. It is critical to consider the community context and systems in which response planning occurs, in that contextual factors contribute127 to opioid-related harms12 and influence development and implementation of community actions. Future research should address the contexts in which plans are situated in order to identify context-specific barriers and modifiable strategies to guide practice.

We also found that most community plans used implementation strategies that focus on changing the knowledge and skills of individuals rather than recommending changes to impact systemic factors. As recognised by socioecological models, individual behaviour is embedded within a system of interacting interpersonal, organisational and policy influences.22 Though it may be methodologically challenging to demonstrate impact of community level strategies,128 by relying on individual level implementation, these plans miss opportunities to intervene on community and policy factors that influence access to resources and achieve population-level change.129

Also lacking was the use of evidence to support the selection of intervention components in community opioid-related plans; thus, conclusions about which interventions constitute best practice in local plans cannot be made. Evidence supports several interventions aimed at reducing opioid or substance-related harms that were used in plans, including: supervised consumption services,130 131 needle and syringe programmes,132 overdose education and naloxone distribution,133 methadone maintenance or buprenorphine treatment134 and school-based strategies that address youth protective factors.135–137 Several plans included interventions that have been found ineffective (eg, Drug Abuse Resistance Education programmes)138 or have little evidence for effectiveness (eg, medication take-back programme).139 140 A complete mapping of the effectiveness of interventions employed across community opioid-related plans warrants further investigation.

There was also minimal description in the literature to identify key principles for developing community opioid-related plans, such as the principles of social justice, health equity and cultural safety described in a recent community guide for overdose response.12 This finding may relate to our observations on the lack of involvement of those disproportionately affected by the crisis (eg, Indigenous persons and people with lived experience of substance use) and initiatives addressing structural determinants of health. Particularly as the value of involving people with lived experience of substance use is well documented,141 our findings underscore the need for meaningfully involving people with lived experience of substance use to ensure approaches better meet population needs.

The strengths of our review include the systematic search of the literature through six electronic databases, three internet search engines, reference lists and referrals of records not identified through the literature source (eg, unpublished sources). The potential use of our findings is enhanced by our engagement of diverse stakeholders in consultations to add perspective to the design and interpretation of the review. Despite our broad search strategy, it is possible that relevant records were missed due to date and language restrictions and screening of the grey literature limited to the first 100 records; however, the language restrictions reduced the search results from MEDLINE, Embase and PsycINFO by less than 5%. Our review primarily identified opioid-related plans from urban communities in the USA, thus our findings may not be applicable to different socioenvironmental contexts (eg, rural communities or outside Canada and the USA). We did not include US state plans that did not describe activities focused at the local level, so our review may under-represent actions at the state level that influence community plans. Our equity analysis was not designed to fully assess such social conditions that impact health status related to opioids; however, this is the basis of a subsequent planned analysis. Finally, our review likely under-represents current community-led responses to opioid-related harms, which are not publicly documented or did not meet our inclusion criteria if intervention components were implemented in isolation of a comprehensive community plan.

Conclusion

Through synthesising the current literature, our scoping review identified some consistent components of community opioid-related plans. This characterisation and identification of gaps can inform the efforts of other communities confronting the opioid crisis. Due to the paucity of evaluations, limited use of evidence in planning, and the variation in interventions, partnerships, engagement and implementation strategies, it is difficult to suggest which components are effective and in what contexts. Considering the growing crisis, and the complexity of multistrategy plans, it is essential that the implementation and contexts of these efforts be documented and evaluated to enable public health decision making. In addition, we heard from stakeholders about the importance of developing community opioid-related plans in partnership with people with lived experience of substance use to better ensure efforts are responsive and relevant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Foremost, we would like to thank our interview, focus group and workshop participants for taking the time to provide feedback on our scoping review. We would also like to acknowledge all Public Health Ontario staff who contributed to the project and workshop: Beata Pach, Chase Simms, Harkirat Singh, Tiffany Oei, Rebecca Mador, Michelle Vine, Andrea Bodkin, Rachel Laxer, Elisabeth Marks and Maggie Civak.

Footnotes

Contributors: PL, HM, JC, MP, GP, ST, RH, SM, SK-O and CS were involved in the conception and design of the study design. SM, PL and TK were involved in data acquisition. PL, TK and NP were involved in data analysis. PL and TK drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in interpretation of the results, critical revision of the manuscript and approval of the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR Operating Grant FRN 156785). Due to time constraints, we did not extract data on the sources of funding for each included record.

Competing interests: All authors (except ST) report grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research during the conduct of the study. PL, TK, NP, SK-O, SM and HM report employment of Public Health Ontario during the conduct of the study. PL and CS report non-financial support from Adapt Pharma (in-kind donation of naloxone on an unrelated study, with no involvement of the company in the study design).

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This component of our review was approved by the Ethics Review Board at Public Health Ontario (File numbers – part 1 and 2: 2018–027.02 and 2018–016.03).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1. Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses National report: apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada (December 2017). Ottawa, ON: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada; 2017. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/apparent-opioid-related-deaths-report-2016-2017-december.html [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ahmad FB, Rossen LM, Spencer MR. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics; 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown ER. Community action for health promotion: a strategy to empower individuals and communities. Int J Health Serv 1991;21:441–56. 10.2190/AKCP-L5A4-MXXQ-DW9K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization The Ottawa charter for health promotion. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1986. http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/index1.html [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization Global strategy to reduce the harmful use of alcohol. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44395/9789241599931_eng.pdf;jsessionid=0EBA536E2D238DAD0867341FE3F72A68?sequence=1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shakeshaft A, Doran C, Petrie D, et al. The effectiveness of community action in reducing risky alcohol consumption and harm: a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001617 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. MacPherson D, Mulla Z, Richardson L. The evolution of drug policy in Vancouver, Canada: strategies for preventing harm from psychoactive substance use. International Journal of Drug Policy 2006;17:127–32. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.10.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Albert S, Brason FW, Sanford CK, et al. Project Lazarus: community-based overdose prevention in rural North Carolina. Pain Med 2011;12 Suppl 2:S77–S85. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alexandridis AA, McCort A, Ringwalt CL, et al. A statewide evaluation of seven strategies to reduce opioid overdose in North Carolina. Inj Prev 2018;24:48–54. 10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shepherd S, Caldwell J. Toronto overdose action plan: prevention & response. Toronto, ON: Toronto Public Health; 2017. https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/968f-Toronto-Overdose-Action-Plan.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sawula E, Greenaway J, Olsen C, Jaun A, Flanagan Q, Leiterman A. Opioid use and impacts in Thunder Bay district. Thunder Bay, ON: Thunder Bay District Health Unit; 2018. https://www.tbdhu.com/sites/default/files/files/resource/2018-03/Opioid%20Use%20and%20Impacts%20in%20Thunder%20Bay%20District%202018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pauly B, Hasselback P, Reist D. Public health guide to developing a community overdose response plan [Internet]. British Columbia: Centre for Addictions Research of British Columbia; 2017. https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/cisur/assets/docs/resource-community-overdose-response-plan.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goodman RA, Bunnell R, Posner SF. What is “community health”? Examining the meaning of an evolving field in public health. Prev Med 2014;67(Suppl 1):S58–S61. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.07.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Sci 2010;5 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:141–6. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. First Nations Health Authority Overdose data and first nations in bc: preliminary findings. West Vancouver, BC: First Nations Health Authority; 2016. http://www.fnha.ca/newsContent/Documents/FNHA_OverdoseDataAndFirstNationsInBC_PreliminaryFindings_FinalWeb.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19. Government of Canada Canadian drugs and substances strategy. Ottawa, ON: Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada; 2016. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/canadian-drugs-substances-strategy.html [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harm Reduction International The global state of harm reduction: towards an integrated response. London, UK: Harm Reduction International; 2012. https://www.hri.global/files/2012/07/24/GlobalState2012_Web.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fixsen D, Blase K, Naoom S, Wallace F. Stages of implementation: activities for taking programs and practices to scale. Chapel Hill, NC: National Implementation Research Network; 2005. https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/stages-implementation-activities-taking-programs-and-practices-scale [Google Scholar]

- 22. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 1988;15:351–77. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alaska Department of Health and Social Services Division of Public Health Narcan [Internet]. Anchorage, AK: State of Alaska, 2018. Available: http://dhss.alaska.gov/dph/Director/Pages/heroin-opioids/narcan.aspx [Accessed 4 Jul 2018].

- 24. Alameda-Contra Costa Medical Association East Bay safe prescribing coalition. Oakland, CA: Alameda-Contra Costa Medical Association; 2018. http://www.accma.org/community-health/safe-prescribing [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alameda-Contra Costa Medical Association East Bay safe prescribing coalition: activities, timeline and goals. Oakland, CA: Alameda-Contra Costa Medical Association; 2018. http://www.accma.org/Portals/0/ACCMA%20Project%20Pages/EB%20Safe%20Prescribing%20Images/EastBaySafeRx%20-%20Activities%20Timeline%20and%20Goals.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alexandridis AA, Dasgupta N, Ringwalt C, et al. Effect of local health department leadership on community overdose prevention coalitions. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;171:e5–6. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Altarum Addressing the opioid crisis in Lorain County, Ohio: Executive summary. Ann Arbor, MI: Altarum; 2017. https://altarum.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-publication-files/Lorain-County-Community-Assessment_Executive-Summary.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barnes J, South Coast Today . New Bedford police, chaplains, counselors reach out to od victims, 2017. Available: http://www.southcoasttoday.com/news/20170103/new-bedford-police-chaplains-counselors-reach-out-to-od-victims

- 29. Berkshire Regional Planning Commission BOAPC: Berkshire opioid abuse prevention collaborative. Pittsfield, MA: Berkshire Regional Planning Commission; 2018. http://berkshireplanning.org/initiatives/boapc [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boulder County Boulder County opioid Advisory group: 2017 roadmap. Boulder, CO; 2017. https://assets.bouldercounty.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/boulder-county-opioid-advisory-group-roadmap.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bowman S, Engelman A, Koziol J, et al. The Rhode island community responds to opioid overdose deaths. R I Med J 2014;97:34–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brason FW, Roe C, Dasgupta N. Project Lazarus: an innovative community response to prescription drug overdose. N C Med J 2013;74:259–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brason FW, Castillo T, Dasgupta N. Lessons learned from implementing project Lazarus in North Carolina. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Injury Prevention Research Center; 2016. https://iprc.unc.edu/files/2016/08/Lessons-Learned-White-Paper-FINAL-8-15-16.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brucker K, O'Donnell D, Rusyniak D, et al. Planned outreach, intervention, naloxone, and treatment): a novel approach to post-opioid overdose care. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24:S129–30. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Public Health Institute, California Tackling an epidemic: an assessment of the California opioid safety coalitions network. Oakland, CA: Public Health Institute; 2017. https://www.phi.org/uploads/application/files/bt93oju0nrnbsmjhpdw692ljgu0d27ttdpzxmbclj7cxq99alz.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cattaraugus County Heroin/Opioid Task Force Cattaraugus county addiction & recovery resources. Olean, NY: Cattaraugus County; 2017. http://www.recoveryincattco.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 37. City of Hamilton Hamilton opioid response: funding Request. Hamilton, ON; 2017. https://pub-hamilton.escribemeetings.com/filestream.ashx?DocumentId=123771 [Google Scholar]

- 38. City of New Orleans Addressing opioid addiction and overdose in New Orleans: a community-based response to a national epidemic. New Orleans, LA: City of New Orleans; 2017. https://nola.gov/city/opioid-plan-10-18-17/ [Google Scholar]

- 39. Colorado Consortium for Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention About the Consortium. Aurora, CO: Colorado Consortium for Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention; 2017. http://www.corxconsortium.org/about-the-consortium/ [Google Scholar]

- 40. Colorado Heroin Response Work Group From law enforcement to treatment: heroin in Colorado, 2017. Available: http://www.corxconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/From-Law-Enforcement-to-Treatment.pdf

- 41. Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment & Tri-County Health Department Tri-County overdose prevention partnership. Available: https://sites.google.com/colorado.edu/tcopp/home [Accessed 1 Aug 2018].

- 42. Community Overdose Action Team Community overdose action team: 2017 annual report. Dayton, OH: Public Health - Dayton & Montgomery County; 2017. https://www.phdmc.org/agency-reports/807-2017-coat-annual-report/file [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cook A. Enhancing harm reduction services in Waterloo region. Waterloo, ON: Region of Waterloo Public Health and Emergency Services; 2017. https://www.regionofwaterloo.ca/en/regional-government/resources/Reports-Plans-Data/Public-Health-and-Emergency-Services/Enhancing-Harm-Reduction-Services-in-Waterloo-Region.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cuyahoga County Opiate Task Force Cuyahoga County opiate Task force report 2016, 2016. Available: http://www.ccbh.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/2016-CCOTF-Annual-Report.pdf [Accessed 1 Oct 2018].

- 45. Dasgupta N, Brason FW, Albert S, et al. Project Lazarus: overdose prevention and responsible pain management. NCMB Forum 2008;1:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Department of Public Health and Environment (DDPHE), City and County of Denver, Denver’s Collective Impact Group Opioid response strategic plan: 2018 - 2023. Denver, CO: Denver Public Health & Environment; 2018. https://www.denvergov.org/content/dam/denvergov/Portals/771/documents/CH/Substance%20Misuse/DDPHE_OpioidResponseStrategicPlan.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 47. Durham Region Health Department Status report: June 2018: Durham region opioid response plan. Whitby, ON: Region of Durham; 2018. https://www.durham.ca/en/health-and-wellness/resources/Documents/AlcoholDrugsandSmoking/DROpioidResponsePlan.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 48. Duwve J, Hancock S, Collier C, Halverson P. Report on the toll of opioid use in Indiana and Marion County: with recommendations for improving health and well-being. Indianapolis, IN: Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health; 2016. https://fsph.iupui.edu/doc/community/Richard_M._Fairbanks_Opioid_Report_September_2016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 49. Feeling trapped. Mod Healthc 2017;47. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Formica SW, Apsler R, Wilkins L, et al. Post opioid overdose outreach by public health and public safety agencies: exploration of emerging programs in Massachusetts. Int J Drug Policy 2018;54:43–50. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fraser Health Overdose response regional supports and services, 2018. Available: https://www.fraserhealth.ca/your-community/overdose-response-regional-supports-and-services [Accessed 1 Oct 2018].

- 52. Prina LL. Funders' efforts to prevent substance use disorders. Health Aff 2018;37:329–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ganeva T. Raising opioid addicts from the dead. Stanford Social Innovation Review 2018;16:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Province of British Columbia Overview: provincial overdose emergency response. Victoria, BC: Province of British Columbia; 2017. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/overdose-awareness/bg_overdose_emergency_response_centre_1dec17_final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 55. Government of Minnesota 2016 tribal-state opioid Summit: final report. Saint Paul, MN: Government of Minnesota; 2017. http://mn.gov/gov-stat/pdf/2017_03_09_Opioid_Summit_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 56. Governor's Cabinet Opiate Action Team Action guide to address opioid abuse. Columbus, OH: Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services; 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20171118132443/http://mha.ohio.gov/Portals/0/assets/Initiatives/GCOAT/GCOAT-Health-Resource-Toolkit.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 57. Green TC, Bratberg J, Dauria EF, et al. Responding to opioid overdose in Rhode island: where the medical community has gone and where we need to go. R I Med J 2014;97:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hamilton County Hamilton County heroin coalition, 2018. Available: http://www.hamiltoncountyohio.gov/government/open_hamilton_county/projects/heroin_coalition/treatment/

- 59. Harvey KB. Responding to the heroin crisis: two initiatives in the eastern district of Kentucky. US Attorneys Bull 2016;64:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 60. HealthCareCAN Responding to the opioid crisis: leading practices, challenges, and opportunities: a summary of the ministerial roundtable on opioids. Ottawa, ON: HealthCareCAN; 2017. http://www.healthcarecan.ca/wp-content/themes/camyno/assets/document/Reports/2017/HCC/EN/OpioidsBackgrounder_EN.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 61. Heroin and Prescription Opiate Addiction Task Force Heroin and prescription opiate addiction Task force final report and recommendations. Tacoma, WA: Heroin and Prescription Opiate Addiction Task Force; 2016. http://www.co.pierce.wa.us/DocumentCenter/View/44171/Heroin-n-Opiate-report [Google Scholar]

- 62. Holmburg M. 388 harm reduction: primary and secondary prevention through community opioid education and distribution of Narcan rescue kits in Haines, Alaska. J Investig Med 2018;66:A228. [Google Scholar]

- 63. KFL&A Public Health Action plan on opioids: reducing the community opioid load, 2016. Available: https://www.kflaph.ca/en/partners-and-professionals/action-plan-on-opioids-reducing-the-community-opioid-load.aspx

- 64. KNOWTHERX Cleveland, OH, 2018. Available: https://www.cleveland.com/knowtherx/

- 65. Korr M. Community forum seeks ways to quell overdose epidemic in RI: less than 20 percent of physicians use prescription monitoring database. R I Med J 2014;97:62–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kuehn BM. Back from the brink: groups urge wide use of opioid antidote to AVERT overdoses. JAMA 2014;311:560–1. 10.1001/jama.2014.481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lancaster M, McKee J, Mahan A. The chronic pain initiative and community care of North Carolina. N C Med J 2013;74:237–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Langlois A. The overdose crisis where to next? community voices from the may 10, 2017, symposium, 2017. Available: http://avi.org/sites/avi.org/files/publications/AVI_OverdoseSymposium.pdf

- 69. Leeds, Grenville & Lanark District Health Unit Opioid overdose cluster plan, 2017. Available: http://healthunit.org/wp-content/uploads/Leeds_Grenville_Lanark_Opioid_Overdose_Cluster_Plan-1.pdf

- 70. Los Angeles County Prescription Drug Abuse Coalition (Safe Med LA) Los Angeles County prescription drug abuse strategic plan: working together to reduce prescription drug abuse & overdose deaths. Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles County Department of Public Health; 2016. http://nebula.wsimg.com/8e13ffa4cb08d0fff8ef0d8986b2ac0b?AccessKeyId=5647EEC704480FB09069&disposition=0&alloworigin=1 [Google Scholar]

- 71. Massachusetts Technical Assistance Partnership for Prevention (MassTAPP) Prevention and reduction of opioid misuse in Massachusetts: guidance document, 2015. Available: http://masstapp.edc.org/sites/masstapp.edc.org/files/MOAPC%20Guidance%20Document%209.12.16.pdf [Accessed 1 Oct 2018].

- 72. Mayhew C. Boone County starts overdose response team. Cincinnati Enquirer, 2017. Available: https://www.cincinnati.com/story/news/local/boone-county/2017/06/16/boone-county-starts-overdose-response-team/404410001/

- 73. City of Philadelphia The mayor's task force to combat the opioid epidemic in Philadelphia: final report & recommendations. Philadelphia, PA: City of Philadelphia; 2017. https://dbhids.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/OTF_Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 74. Minnesota Department of Health; Minnesota Department of Human Services; Minnesota Department of Corrections; Minnesota Department of Public Safety Minnesota's opioid action plan, 2018. Available: http://mn.gov/gov-stat/pdf/2018_02_14_Minnesota_Opioid_Action_Plan.pdf [Accessed 1 Aug 2018].

- 75. Moore K, Boulet M, Lew J, et al. A public health outbreak management framework applied to surges in opioid overdoses. J Opioid Manag 2017;13:273–81. 10.5055/jom.2017.0396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Moore KM, Papadomanolakis-Pakis N, Hansen-Taugher A, et al. Recommendations for action: a community meeting in preparation for a mass-casualty opioid overdose event in southeastern Ontario. BMC Proc 2017;11(Suppl 7):8 10.1186/s12919-017-0076-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Nash DB. "Opioids Equal Heroin". Am Health Drug Benefits 2017;10:391–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. National Association of Counties; National League of Cities A prescription for action: local leadership in ending the opioid crisis, 2016. Available: http://opioidaction.org/report/

- 79. Close R, Grover C. New initiative slashes opioid prescriptions, boosts community response. ED Manag 2016;28:109–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. New York State Association of Counties County case studies in Battling New York's heroin and opioid epidemic. Albany, NY: New York State Association of Counties; 2016. http://www.nysac.org/files/NYSAC%20Heroin%20CASE%20STUDIES%209-13-16(1).pdf [Google Scholar]

- 81. North Carolina Division of Public Health Healthy North Carolina 2020: injury and violence - reducing unintentional poisonings: a success story in progress. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. http://publichealth.nc.gov/hnc2020/docs/UnintentionalPoisoningSuccessStory-DPH-2012-FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 82. Northern Sierra Opioid Safety Coalition Northen Sierra Opioid Safety Coalition: "to reduce opioid misuse and abuse in Plumas, Lassen, Sierra, and Modoc Counties", 2016. Available: http://www.countyofplumas.com/index.aspx?NID=2448

- 83. Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness Nova Scotia's opioid use and overdose framework. Halifax, NS: Crown Copyright, Province of Nova Scotia; 2017. https://novascotia.ca/opioid/nova-scotia-opioid-use-and-overdose-framework.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 84. Opiate Task Force of Clermont County Get clean now Clermont. Batavia, OH: Clermont County Mental Health and Recovery Board; 2018. https://www.getcleannowclermont.org/home-1.html [Google Scholar]

- 85. Opioid Strategy Action Group Central East LHIN opioid strategy. Ajax, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2018. www.centraleastlhin.on.ca/page.aspx?id=789975175EB04B2C9B61960B7104C9F1 [Google Scholar]

- 86. Orange County Collaborative on Prescription Drug Abuse (SafeRx OC) Taking actions for a safer OC: a countrywide initiative to stop the misuse and abuse of prescription drugs. Available: http://www.saferxoc.org/home.html

- 87. Pennsylvania Opioid Overdose Reduction Technical Assistance Center OverdoseFreePA, 2018. Available: https://www.overdosefreepa.pitt.edu [Accessed 4 Jul 2018].

- 88. Palombi LC, Vargo J, Bennett L, et al. A community partnership to respond to the heroin and opioid abuse epidemic. J Rural Health 2017;33:110–3. 10.1111/jrh.12180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Paone D, Tuazon E, Kattan J, et al. Decrease in rate of opioid analgesic overdose deaths - Staten Island, New York City, 2011-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:491–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Patients at risk for od should get naloxone: project Lazarus. Alcohol Drug Abuse Wkly 2012;24:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Placer-Nevada County Medical Society Rx drug safety: Placer and Nevada County. Available: http://www.pncms.org/rxdrugsafety/

- 92. Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Center of Excellence at Brandeis University Notes from the field: project Lazarus: using PDMP data to mobilize and measure community drug abuse prevention. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University; 2012. http://www.pdmpassist.org/pdf/Resources/project_lazarus_nff_a.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 93. Project Lazarus Project Lazarus annual report 2010. Moravian Falls, NC: Project Lazarus Blog; 2018. https://issuu.com/projectlazarusnc/docs/prolaz_2010_annual_report [Google Scholar]

- 94. Project Lazarus Learn about the project Lazarus model. Moravian Falls, NC: Project Lazarus; 2009. https://www.projectlazarus.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 95. Project Lazarus blog $2.6 Million announced to take Project Lazarus statewide! Moravian Falls, NC: Project Lazarus; 2013. http://projectlazarusnc.tumblr.com/post/48213120670/26-million-announced-to-take-project-lazarus [Google Scholar]

- 96. Raimondo GM. Rhode island overdose prevention and intervention Taskforce action plan, 2016. Available: https://www.governor.ri.gov/documents/press/051116.pdf [Accessed 1 Aug 2018].

- 97. Rebbert-Franklin K, Haas E, Singal P, et al. Development of Maryland local overdose fatality review teams: a localized, interdisciplinary approach to combat the growing problem of drug overdose deaths. Health Promot Pract 2016;17:596–600. 10.1177/1524839916632549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Rendon CS. The Northern district of Ohio model: community action. US Attorneys Bull 2016;64:32–5. [Google Scholar]

- 99. Rhode Island Department of Health; Rhode Island Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals Rhode island community overdose engagement Summit: guide to developing a municipal overdose response plan. Cranston, NE: Rhode Island Department of Health; 2018. https://www.riresponds.org/files/PublicFileManager.ashx?utm_source=trex&utm_medium=email&Guid=0e4e51dc-0126-4297-9f12-beb16b4ee454 [Google Scholar]

- 100. Ringwalt C, Sanford C, Dasgupta N, et al. Community readiness to prevent opioid overdose. Health Promot Pract 2018;19:747–55. 10.1177/1524839918756887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Rx Safe Humboldt Coalition Rx Safe Humboldt: safer care and better outcomes, 2018. Available: http://www.rxsafehumboldt.org/ [Accessed 6 Aug 2018].

- 102. Rx Safe Humboldt Coalition Rx safe Humboldt coalition opioid safety: background and history. eureka, Ca: RX safe Humboldt coalition. Available: http://www.rxsafehumboldt.org/Humboldt%20Chronic%20Pain%20Coalition%20Backgroud%20information.pdf

- 103. RxSafe Marin [Internet]. San Rafael, CA: RxSafe Marin, 2018. Available: https://rxsafemarin.org/ [Accessed cited 2018 Aug 9].

- 104. Safe Rx Mendocino Safe Rx Mendocino opioid safety coalition, 2016. Available: https://www.saferxmendocino.com/ [Accessed 8 Aug 2018].

- 105. Health Improvement Partnership of Santa Cruz County Safe Rx Santa Cruz County. Scotts Valley, CA: Health Improvement Partnership of Santa Cruz County; 2018. https://www.hipscc.org/saferx [Google Scholar]

- 106. Samuels E. Emergency department naloxone distribution: a Rhode island department of health, recovery community, and emergency department partnership to reduce opioid overdose deaths. R I Med J 2014;97:38–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. San Luis Obispo Opioid Safety Coalition Action team: community prevention [Internet]. San Luis Obispo, CA: County of San Luis Obispo. Available: http://communityprevention.opioidsafetyslo.org/ [Accessed 6 Aug 2018].

- 108. San Luis Obispo Opioid Safety Coalition Data collection and monitoring [Internet]. San Luis Obispo, CA: County of San Luis Obispo. Available: http://data.opioidsafetyslo.org/ [Accessed 10 Aug 2018].

- 109. San Luis Obispo Opioid Safety Coalition Medication assisted treatment [Internet]. San Luis Obispo, CA: County of San Luis Obispo. Available: http://mat.opioidsafetyslo.org/ [Accessed 9 Aug 2018].

- 110. San Luis Obispo Opioid Safety Coalition Naloxone overdose antidote [Internet]. San Luis Obispo, CA: County of San Luis Obispo. Available: http://naloxone.opioidsafetyslo.org/ [Accessed 8 Aug 2018].

- 111. San Luis Obispo Opioid Safety Coalition Safe prescribing and health care [Internet]. San Luis Obispo, CA: County of San Luis Obispo. Available: http://saferx.opioidsafetyslo.org/ [Accessed 8 Aug 2018].

- 112. San Luis Obispo Opioid Safety Coalition San Luis Obispo County data report on opioids [Internet]. San Luis Obispo, CA: County of San Luis Obispo, 2018. Available: http://www.opioidsafetyslo.org/ [Accessed 6 Aug 2018].

- 113. SCCgOV Santa Clara County opioid overdose prevention project (SCCOOPP), 2018. Available: https://www.sccgov.org/sites/bhd/info/opioid/Pages/home.aspx

- 114. Smith MY, Kleber HD, Katz N, et al. Reducing opioid. analgesic abuse: models for successful collaboration among government, industry and other key stakeholders. Drug Alcohol Depend 2008;95:177–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. South East Local Health Integration Network LHIN South East LHIN opioid management strategy. Belleville, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2017. http://www.southeastlhin.on.ca/~/media/sites/se/UploadedFiles/BoardOfDirectors/BoardMeetings/BoD-Mtg-149-June26-2017/8%20A%20-%20Opioid%20Management%20Strategy.pdf?la=en [Google Scholar]

- 116. St. Mary's County Health Department Opioid crisis response plan, 2017. Available: http://www.smchd.org/wp-content/uploads/Opioid-Response-Plan_10-17.pdf [Accessed 1 Oct 2018].

- 117. Suffolk Heroin and Opiate Epidemic Advisory Panel Findings and recommendations of the Suffolk heroin and opiate Advisory panel. Smithtown, NY: Suffolk County Legislature; 2010. https://www.scnylegislature.us/DocumentCenter/View/12124/Findings-and-Recommendations-of-the-Suffolk-Heroin-and-Opiate-Advisory-Panel-PDF [Google Scholar]

- 118. Thomson E, Lampkin H, Maynard R, et al. The lessons learned from the fentanyl overdose crises in British Columbia, Canada. Addiction 2017;112:2068–70. 10.1111/add.13961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Thompson CA. Pittsburgh project takes novel approach in fighting opioid epidemic. Health Syst Pharm 2016;73:1717–8. 10.2146/news160062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Tomassoni AJ, Hawk KF, Jubanyik K, et al. Multiple Fentanyl Overdoses - New Haven, Connecticut, June 23, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:107–11. 10.15585/mm6604a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Vancouver Police Department The opioid crisis: the need for treatment on demand, 2017. Available: http://vancouver.ca/police/assets/pdf/reports-policies/opioid-crisis.pdf [Accessed 1 Oct 2018].

- 122. Vermont Department of Health Public health strategies to reduce opioid use disorders: 2017-2020, 2017. Available: http://www.healthvermont.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2017/03/ADAP_Opioid_Strategy_Brief.pdf [Accessed 1 Oct 2018].

- 123. Washington State Department of Health 2018 Washington state opioid response plan. Olympia, WA: Washington state department of health, 2018. Available: https://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/1000/140-182-StateOpioidResponsePlan.pdf

- 124. Weber W, Alnajjar K. Opioid needs assessment and response plan. Aberdeen, WA: Grays Harbor County Public Health and Social Services Department; 2018. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/53ee83dee4b027cf34f1b520/t/5a99e51dc830255b24067ebb/1520035105024/Opioid+Needs+Assessment+and+Response+Plan.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 125. Windsor-Essex County Health Unit; Windsor-Essex Community Opioid Strategy - Leadership Committee Windsor-Essex community opioid strategy: consultation document, 2017. Available: https://www.wechu.org/sites/default/files/pdf/OpioidStrategy_ConsultationDocument_ENG.pdf [Accessed 1 Oct 2018].

- 126. Kania J, Kramer M. Collective impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review 2011;9:36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 127. Edwards N, Di Ruggiero E. Exploring which context matters in the study of health inequities and their mitigation. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(6_suppl):43–9. 10.1177/1403494810393558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Merzel C, D'Afflitti J. Reconsidering community-based health promotion: promise, performance, and potential. Am J Public Health 2003;93:557–74. 10.2105/AJPH.93.4.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav 2010;51 Suppl:S28–S40. 10.1177/0022146510383498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Potier C, Laprévote V, Dubois-Arber F, et al. Supervised injection services: what has been demonstrated? A systematic literature review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;145:48–68. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Kennedy MC, Karamouzian M, Kerr T. Public health and public order outcomes associated with supervised drug consumption facilities: a systematic review. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2017;14:161–83. 10.1007/s11904-017-0363-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Ritter A, Cameron J. A review of the efficacy and effectiveness of harm reduction strategies for alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs. Drug Alcohol Rev 2006;25:611–24. 10.1080/09595230600944529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Furlan AD, Carnide N, Irvin E, et al. A systematic review of strategies to improve appropriate use of opioids and to reduce opioid use disorder and deaths from prescription opioids. Canadian Journal of Pain 2018;2:218–35. 10.1080/24740527.2018.1479842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ 2017;357 10.1136/bmj.j1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Das JK, Salam RA, Arshad A, et al. Interventions for adolescent substance abuse: an overview of systematic reviews. J Adolesc Health 2016;59:S61–S75. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Hodder RK, Freund M, Wolfenden L, et al. Systematic review of universal school-based 'resilience' interventions targeting adolescent tobacco, alcohol or illicit substance use: A meta-analysis. Prev Med 2017;100:248–68. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Stockings E, Hall WD, Lynskey M, et al. Prevention, early intervention, harm reduction, and treatment of substance use in young people. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:280–96. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00002-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Caputi TL, Thomas McLellan A, McLellan A. Truth and D.A.R.E.: Is D.A.R.E.’s new Keepin’ it REAL curriculum suitable for American nationwide implementation? Drugs 2017;24:49–57. 10.1080/09687637.2016.1208731 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Egan KL, Gregory E, Sparks M, et al. From dispensed to disposed: evaluating the effectiveness of disposal programs through a comparison with prescription drug monitoring program data. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2017;43:69–77. 10.1080/00952990.2016.1240801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Kennedy-Hendricks A, Gielen A, McDonald E, et al. Medication sharing, storage, and disposal practices for opioid medications among US adults. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1027–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Ti L, Tzemis D, Buxton JA. Engaging people who use drugs in policy and program development: a review of the literature. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2012;7:47 10.1186/1747-597X-7-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028583supp001.pdf (33.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028583supp002.pdf (23.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028583supp003.pdf (170.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028583supp004.pdf (54.2KB, pdf)