Abstract

Objectives

The current study aimed to validate and determine the psychometric properties of the Arabic versions of the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in Qatar.

Design

A cross-sectional study design was employed.

Setting

Antenatal care (ANC) clinics at nine primary healthcare centres.

Participants

Pregnant women (n=128) aged 15–46 years in different trimesters of pregnancy, attending the ANC clinics as well as capable of reading and writing in the Arabic language.

Results

A total of 128 participants were enrolled. On conducting the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, the EPDS showed a larger area under the curve at 0.951 than the BDI-II tool (0.912). Using Youden’s index, a score >13 on the EPDS (87% sensitivity, 90% specificity) and >19 on the BDI-II (96% sensitivity, 73% specificity) allowed for the greatest division between depressed and non-depressed participants.

Conclusion

To address the under-recognition of antenatal depression, physicians at primary healthcare centres in Qatar should be encouraged to utilise the EPDS to screen pregnant women seeking ANC services.

Keywords: mental health, antenatal depression, validation studies, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, Beck Depression Inventory-II, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This was the first study in the State of Qatar to identify the most valid screening tool for antenatal depression. Furthermore, the study identified the optimal cut-off points for the Arabic versions of the EPDS and BDI-II among the pregnant population in the country.

The sample in the current study was derived from a heterogeneous population of pregnant women across the Qatar.

The examined screening tools in the study were compared with the golden standard (MINI) tool.

One of the limitations of this study was the inability to use the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 as a tool for diagnosing antenatal depression.

Introduction

Globally, maternal mental health problems are considered as a major public health challenge, where depression affects 10% of pregnant women in developed countries and 15.6% in the developing nations (WHO, 2017).1 2 Also, the variation in the prevalence of pregnancy-related depression from one country to another may be justified by the use of different measurement tools and methodologies among the different populations.

High figures were revealed in Arab Gulf countries, where antenatal depression was estimated to impact more than half (57.5%) of expecting mothers in Saudi Arabia and almost a quarter (24%) in Oman during 2016.3 4 However, pregnant women with mental disorders can be managed through effective and low-cost interventions after being properly screened by their healthcare providers.5 6

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) encourages the identification of antenatal depression through screening all gravid women at the primary healthcare level, given the fact that antenatal depression is a serious, prevalent and treatable disease (B recommendation).7 Nevertheless, there is a lack of strong evidence regarding the best screening tool to be employed.8

In 2017, a published systematic review compared seven screening tools including the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD), Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSCL), Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) and Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ). The review concluded that the EPDS was the most suitable antenatal depression screening tool in low-resource settings due to its superior level of accuracy and sensitivity.9

Debatably, some researchers prefer EPDS as it excludes constitutional symptoms (eg, changes in sleeping pattern and food habits) in the screening of antenatal depression as such symptoms are considered uninformative and common in normal pregnancy.10 On the other hand, some scholars choose BDI-II, arguing that somatic symptoms are valid indicators and these constitutional symptoms should not necessarily be dismissed as normative pregnancy experiences.11 Given the ease of administrating self-report measures in the clinical and research settings, the decision to include or exclude the aforementioned symptoms is crucial for decision makers as it will affect their choice of the screening tool.

The identification of an optimal cut-off point could be a key consideration when screening pregnant women especially that literature reveals different cut-off points used among different populations to distinguish between depressed and non-depressed pregnant women. For BDI-II diverse cut-off points were used including a cut-off >15 in Brazil,12 while higher cut-off point >16 was used in Washington.13 Similarly, For EPDS, a cut-off value of >10 was employed in Korea14 and Spain,15 while >11 was used in Nigeria16 and >13 was used in New Zealand as well as in Japan.17 18 This indicates that there is no international agreement on a specific cut-off value for antenatal depression screening. Furthermore, the adequate determination of this threshold in the screening process is necessary to decrease the false positive and false negative rates and their relevant implications.

Qatar is a country located on the west coast of the Arabian Gulf and a member of the Gulf Cooperation Council. During the past decade, the country has been the home for the world’s fastest growing population and second highest migrant population.19 The Arab population currently constitutes about 27% of the total population (45% are Qatari and 55% are non-Qatari).20 Based on Qatar’s new National Health Strategy (2018–2022), there is a focus on preventative strategies among specific vulnerable cohorts such as pregnant women.21 Thus, the country’s main provider of primary health services, the Primary Health Care Corporation (PHCC), has aligned its corporate strategy with the National Health Strategy and is aiming at better population health through early detection and screening programme by 2023.22

Unfortunately, there is a lack of evidence regarding the most valid screening tool to detect depression among pregnant women in the country. Thus, the objective of this study is to validate and determine the psychometric properties of the BDI-II and the EPDS in Qatar.

Material and methods

This study is part of a larger project that aimed to measure the prevalence of antenatal depression in Qatar at the PHCC. The results of the pilot study in relation to the validation of the Arabic version of EPDS and BDI-II are reported in this paper.

Study design and setting

This was a cross-sectional study conducted among Arab pregnant women attending the antenatal clinics of the PHCC in Qatar. The data was collected during both morning and evening work shifts of the health centres and the data collection took place in August and September of 2018.

The primary health centres are the first line of contact between pregnant women and the healthcare system in the country with antenatal participation rate is high as 60% of the total live births. PHCC provides accessible preventive, promotive and curative services to the community in Qatar. At the time of the study, there were 23 antenatal clinics across the country and each clinic was operated by a Family Medicine Practitioner.23

Sampling methods or strategy

A cluster random sampling technique was employed. First, the list of the primary health centres that provide antenatal services was obtained from the ‘Operations Department’ at PHCC. The list also included the total number and percentage of pregnant women attending the antenatal care (ANC) clinic in each health centre and in total (23 centres during the study period). Second, the automated random number generator technique was used to randomly select 9 health centres out of 23. Thus, each selected health centre was designated as a cluster. Finally, the nine selected health centres were visited by data collectors to enrol eligible participants on a daily basis until fulfilling the quota (n=128).

Patient and public involvement

We did not involve patients or the public in our work.

Sample size and participants

In order to validate the aforementioned screening tools and identify their psychometric properties, the sample size was calculated at 100 to adequately estimate the sensitivity and specificity of the tools, given a margin of error of at most 5% and a 95% CI.24 To be included in the study, the participants had to be pregnant women (aged 15–49 years) and they were capable of reading and writing in the Arabic language and granting a written consent and assent. No restrictions were made regarding the specific trimester of pregnancy.

Research protocol

The eligible pregnant women were first informed about the study and its objectives. After signing the consent form, the participants were briefly interviewed about their demographic and pregnancy-related characteristics. Afterwards, they were asked to complete the self-administrated Arabic versions of the EPDS and BDI-II tools before their scheduled ANC visit. Subsequently, the participants would directly undergo the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) with the primary care physician during their ANC visit to avoid any unwanted exposure or interference. Also, the aforementioned physicians were blinded to the results of the EPDS and BDI-II tools. Thus, the enrolled pregnant women were assessed for antenatal depression through the three tools during the same visit. As a result, any participant who was diagnosed positive for antenatal depression through the MINI tool was referred to specialised secondary care (psychiatrists) for further evaluation and management.

Data collection tools

An interview-based and structured questionnaire on sociodemographic and pregnancy-related characteristics (age, nationality, gravidity, trimester, family income, number of children, educational level, occupational status and family size).

The EPDS is a self-administrated tool and was first published in the British Journal of Psychiatry during 1987. It consists of 10 items and has been validated for use in different populations.25

The BDI-II, first introduced in 1961, is a 10 min brief self-administered questionnaire that can detect the presence of depressive symptoms. It consists of 21 questions pertaining to the various aspects of mood such as sadness, suicidal ideation, loss of weight and social withdrawal.26

The MINI is a short, diagnostic and structured interview that is used for diagnosing major axis I psychiatric disorders in DSM-V and ICD-10.27 The MINI tool was employed and validated through several studies, particularly for diagnosing depression disorders.28 29

Translation

First, the standard English versions of the EPDS and BDI-II tools were retrieved. Then, they were translated to Arabic by a bilingual clinician whose primary language is Arabic and is familiar with the terminology of the area covered by the instrument (forward translation). Next, a panel consisting of one clinician, a researcher in the field and the aformentioned translator checked the expressions and concepts of the Arabic version for any discrepancy in comparison to the original English one. Any significant difference was corrected in consensus and the final Arabic versions were translated back to English by an independent bilingual clinician whose mother tongue was English. After the back translation ensured the accuracy of the translated versions, they were piloted on a sample of 20 pregnant women. The pilot testing aimed to check if the Arabic versions were clear and understandable among study subjects as well as interviewers, where the piloted sample was excluded from analyses.

Statistical analysis

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were summarised using descriptive statistics in the form of means and SD for quantitative variables as well as frequency and percentages for categorical variables. Additionally, bivariate analyses were conducted through the chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests to compare the association between the dependent (antenatal depression) and independent variable (sociodemographic and clinical characteristics).

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was employed to measure the accuracy of the EPDS and BDI-II in diagnosing major depression according to DSM-V criteria. Afterwards, Youden’s index (J=Sensitivity+ Specificity −1) was used to determinate the best cut-off points for antenatal depression screening. Also, Cronbach's alpha (α) was employed as an estimate of scale reliability, internal consistency and item homogeneity.

To examine the concordance among the psychometric scales tested, the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was calculated. In addition, a principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out on the EPDS and BDI-II tools to identify the components of the tools contributing to the most of the variance. The convergent construct validity of the EPDS was demonstrated through a rotated component matrix (varimax rotation). The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) values were considered for measuring sampling adequacy.

The analysis was conducted using the SPSS V.23 based on a preset significant level of 0.05.

Results

Demographical characteristics

One hundred and twenty-eight (128) pregnant women matched the inclusion criteria and accepted to participate in the current study. Table 1 presents the background characteristics of the study participants, where most of the pregnant women were non-Qatari Arabs (82%), holding a diploma or university degree (70%), unemployed (55%), with a monthly family income >10 000 QR (75%), multigravid (71%), and in the second trimester of their pregnancy (48%). Additionally, the mean age of the participants was 28.8 (SD=5 years).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample (n=128)

| MINI diagnostic | Total (n) | P value | |||

| Positive n (%) | Negative n (%) | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 20–34 | 31 (26) | 87 (74) | 118 | 0.87 | 0.46 |

| 35–46 | 4 (40) | 6 (60) | 10 | ||

| Nationality | |||||

| Qatari | 6 (23.1) | 17 (73.9) | 23 | 0.053 | 0.817 |

| Other Arabs | 25 (23.8) | 80 (79.2) | 105 | ||

| Trimester | |||||

| First trimester | 8 (29.6) | 19 (70.4) | 27 | 1.56 | 0.457 |

| Second trimester | 12 (19.4) | 50 (80.6) | 62 | ||

| Third trimester | 11 (28.2) | 28 (71.8) | 39 | ||

| Gravida | |||||

| Primigravida | 10 (73) | 27 (27.8) | 37 | 0.224 | 0.636 |

| Multigravida | 21 (23.1) | 70 (76.9) | 91 | ||

| Family monthly income (QR) | |||||

| <10 000 QR | 7 (22.6) | 24 (77.4) | 31 | 4.5 | 0.1 |

| 10 000–<20 000 QR | 20 (37) | 34 (63) | 54 | ||

| ≥20 000 QR | 8 (18.6) | 35 (81.4) | 43 | ||

| Number of children | |||||

| 0 | 10 (26.3) | 28 (73.7) | 38 | 1.48 | 0.685 |

| 1–3 | 19 (22.9) | 64 (77.1) | 83 | ||

| 4–5 | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | 5 | ||

| >6 | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 2 | ||

| Educational level* | |||||

| Higher education | 18 (20) | 72 (80) | 90 | ||

| Secondary education | 7 (25.9) | 20 (74.1) | 27 | 9.1 | 0.027* |

| Primary education | 6 (54.5) | 5 (45.5) | 11 | ||

| Occupational status | |||||

| Housewife | 20 (28.2) | 51 (71.8) | 71 | ||

| Employed | 8 (17.4) | 38 (82.6) | 46 | 1.828 | 0.4 |

| Student | 3 (27.3) | 8 (27.7) | 11 | ||

| Family size* | |||||

| Small family size (<5) | 11 (14.7) | 64 (85.3) | 75 | 11.63 | 0.003* |

| Average family size (=5) | 10 (50) | 10 (50) | 20 | ||

| Large family size (>5) | 10 (30.3) | 23 (69.7) | 33 | ||

*P<0.05/a=Fisher test/χ2.

QR, Qatari Riyals.

Psychometric properties of the scales

Reliability

The internal consistencies of the EPDS and BDI-II scales were calculated at α=0.865 and 0.90, respectively. Using Lawshe’s method, an expert panel of three clinicians evaluated the questionnaire for the necessity of items, their grammar, wording and scaling. The necessity of each item was assessed using a 3-point rating scale: (1) not necessary, (2) useful but not essential and (3) essential. The universal agreement between the three raters was 78% for the EPDS (intraclass correlation coefficient r=0.78 (CI 0.16 to 0. 94)) and 59% for the BDI-II (intraclass correlation coefficient r=0.59 (CI 0.033 to 0.9)).

Cut-offs

Based on Youden’s index, the following cut-off scores were determined: a score >13 on the EPDS (87% sensitivity, 90% specificity) and >19 on the BDI-II (96% sensitivity, 73% specificity) (table 2).

Table 2.

The psychometric properties of the EPDS and BDI-II scales

| Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Corrected classified | LR+ | LR− | Youden’s index (%) |

|

| EPDS | >8 | 96 | 64 | 46.2 | 2.66 | 0.062 | 60 |

| >9 | 96 | 68 | 49.2 | 3 | 0.0058 | 64 | |

| >10 | 96 | 76 | 55.6 | 4 | 0.0052 | 72 | |

| >11 | 90 | 83 | 62.2 | 5.29 | 0.12 | 73 | |

| >12 | 87 | 88 | 69.2 | 7.25 | 0.15 | 75 | |

| >13 | 87 | 90 | 77.1 | 8.7 | 0.14 | 77 | |

| >14 | 71 | 99 | 84.6 | 17.3 | 0.29 | 71 | |

| BDI-II | >18 | 96 | 63 | 46 | 2.59 | 0.063 | 59 |

| >19 | 96 | 73 | 51.7 | 3.5 | 0.05 | 69 | |

| >20 | 90 | 76 | 53.8 | 3.75 | 0.13 | 66 | |

| >21 | 90 | 77 | 54 | 3.9 | 0.12 | 67 | |

| >22 | 80 | 80 | 55.6 | 4 | 0.25 | 60 | |

| >23 | 74 | 82 | 56.1 | 4.1 | 0.31 | 56 | |

| >24 | 67 | 84 | 56.8 | 4.18 | 0.39 | 51 |

BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; LR, Likelihood ratio.

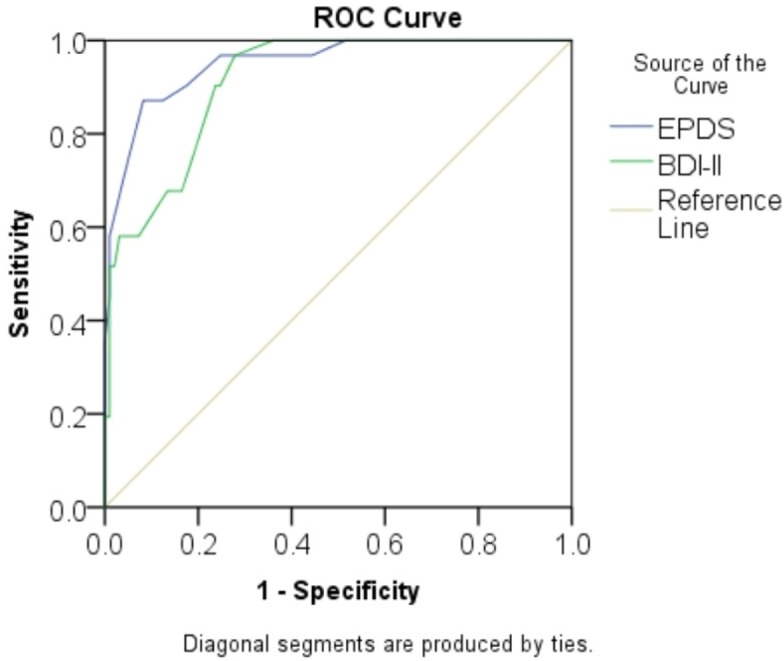

Validity

Using ROC analysis, the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated at 0.951 (SE=0.02; 95% CI=0.91 to 0.99) for EPDS and 0.912 (SE=0.025; 95% CI=0.86 to 0.96) for BDI-II (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Receiving operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the EPDS and BDI-II. BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

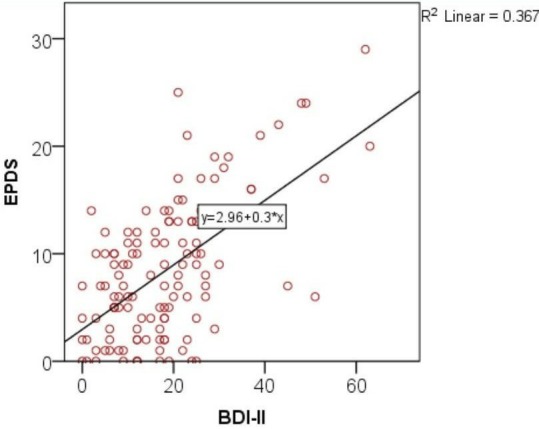

Correlation

The correlation established between EPDS and BDI-II was 60% which represent a weak uphill linear correlation (figure 2). Thus, the explained variance will be 37%.

Figure 2.

Correlation between EPDS and BDI-II. BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

Construct validity

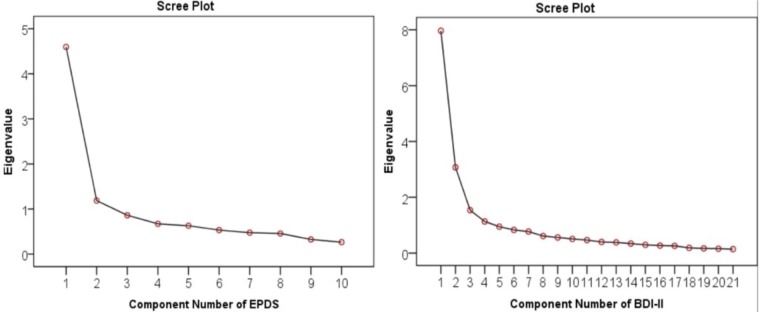

PCA was conducted for the EPDS and BDI-II scales (figure 3). The analysis suggested that two components of the EPDS explain most of the variance with a cumulative percentage of 58%. The two components were item 2 (sadness) and item 8 (optimism). The convergent construct validity of EPDS was demonstrated through a rotated component matrix of 0.75, which is acceptable and significant (p=0.01). Discriminant validity was supported because no violations were seen in the correlation matrix. Also, the scree plot of the BDI-II suggests that four components explain most of the variance with a cumulative percentage of 65.2%. These four factors were item 7 (self-dislike), item 2 (pessimistic), item 3 (past failure) and item 6 (punishment feeling). The convergent construct validity of the BDI-II was weak as seen through a rotated component matrix of 0.45. No violations were noted in the correlation matrix, hence supporting discriminant validity. The KMO values were considered for measuring sampling adequacy for each factor analysis and it showed to be 0.872 (p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Scree plots of EPDS and BDI-II. BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

Discussion

In the current study, a similar prevalence rate of antenatal depression was found through the EPDS and MINI-interview tools at 27.3% and 24%, respectively. However, the BDI-II detected a higher prevalence at 45.3%. Overall, the EPDS was found to be superior to the BDI-II because the positive predictive value of the former (0.75) was much higher than that of the latter (0.54).

Given that the positive predictive value could be influenced by the actual prevalence of the disease, the likelihood ratio was calculated and revealed that the EPDS had a higher positive likelihood ratio, nearly triple that of the BDI-II. Additionally, the EPDS showed a higher Youden’s index. So, the EPDS demonstrated a better performance and was the more useful screening tool for antenatal depression in Qatar.

The previously mentioned result is consistent with that of a systematic review on antenatal depression screening instruments across low resource settings, which revealed an apparent superiority for EPDS (AUC=0.96) with a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 0.80 and 0.81, respectively.9 Similarly, a meta-analysis on the reliability and validity of perinatal depression screening instruments for perinatal depression in African countries concluded that the EPDS was the most reliable and valid tool.30 On the other hand, the current results oppose those reported from a similar validation study in Brazil, where the BDI-II was found to be the best-performing screening instrument (AUC=0.9) and showed higher accuracy than the EPDS (AUC=0.85).12

In addition to that, a key question was which cut-off point will reveal the maximum dichotomy between the depressed and non-depressed patients and result in further intervention. The current study revealed that the best cut-off value for the EPDS was >13, which is consistent with that obtained from studies in Saudi Arabia, Oman and New Zealand.3 4 17 Additionally, a score above 13 was identified as the optimal EPDS cut-off point by a recent study in Japan. On the other hand, the study yielded an AUC of 0.956 as well as a sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 92.1%, respectively,18 whereas an EPDS cut-off value >9 was the most optimal in African countries. The aforementioned value was associated with a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 0.94 and 0.77, respectively.30 Another study in Spain showed that EPDS cut-off value >10 (AUC of 0.76, sensitivity of 72.4%, specificity of 79.3%, positive predictive value of 18.2%, negative predictive value of 97.8%, and overall accuracy of 78.9%).15

Regarding the BDI-II tool, the results showed that a cut-off value >19 distinguishes the most between depressed and non-depressed expecting mothers. In contrast, the previously mentioned validation study in Brazil determined that the optimal cut-off value was >16.12 Also, a much lower BDI score (11/12) was identified as the optimal cut-off point among pregnant women in Taiwan at which the sensitivity and the specificity were 74% and 83%, respectively.31 Such variation of results across different settings highlights the importance of validation studies to identify the most appropriate screening tool and associated cut-off value in each population.

In order to minimise the selection bias, the sample taken in this study included pregnant women during all trimesters of pregnancy in the first (21%), second (48%) and third (30%) trimester of pregnancy. This has been supported by the recommendation of the USPSTF which underlines the importance of screening pregnant women for antenatal depression regardless of their gestational age.7 In addition to that, a study conducted in Saudi Arabia found an insignificant difference in the prevalence of antenatal depression across different trimesters.3 However, a study conducted in Korea concluded that the highest prevalence of antenatal depression occurred during the third trimester (61.4%).14 On the other hand, another study from Nigeria determined that the first trimester entailed the higher burden of antenatal depression with a prevalence of 27.5%.16

This was the first study in the State of Qatar to identify the most suitable screening tool for antenatal depression. The study sample in the current study was derived from a heterogeneous population of pregnant women, regardless of the gestational age, attending nine primary health centres across the country. Furthermore, the investigators were blinded to the results to avoid any interviewer bias. Also, the examined screening tools in the study were compared with the golden standard tool (MINI). Similarly, the construct validity of the EPDS has been demonstrated in the current study. The aforementioned factors allow for the universal administration of the EPDS as a screening tool in Qatar’s primary healthcare setting. One of the limitations in this study was the inability to use the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 as a tool for diagnosing antenatal depression.32 The reason behind this was the need for lengthy appointments, which was not feasible because such action will interrupt the general workflow at the ANC clinic of the primary healthcare centre.

In conclusion, the current study shows that the EPDS is superior to BDI-II as an antenatal depression screening tool at the primary healthcare level in Qatar. The EPDS was found to have better psychometric properties in comparison to the BDI-II tool. Ultimately, the proper use of the aforementioned screening tools along with their cut-off values will help in the early identification of antenatal depression among pregnant women in Qatar. As a result, such step will help raise awareness about antenatal depression and alleviate some of its burden in the country.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Rajvir Singh for his support during this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: SN designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, interpretated the results and drafted the manuscript. NA-K and IB helped in designing the study. MC and AA-D helped in data analysis and participated in the preparation of the manuscript. NA helped in data collection, entry and interpretation. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: The publication of this article was funded by the Qatar National Library.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Primary Health Care Corporation under protocol ID (PHCC/RC/18/06/002).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

- 1. Cohen N Public health perspectives on depressive disorders. Baltimore: John Hopkins University, 2017: 281. [Google Scholar]

- 2. who World Health organization (who). who maternal mental health, 2017. Available: http://www.who.int/mental_health/maternal-child/maternal_mental_health/en/ [Accessed 17 Apr 2018].

- 3. Alotaibe H, Elsaid T, Almomen R. The prevalence and risk factors for antenatal depression among pregnant women attending clinics in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. EJPMR 2016;3:60–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Al-Azri M, Al-Lawati I, Al-Kamyani R, et al. . Prevalence and risk factors of antenatal depression among Omani women in a primary care setting: cross-sectional study. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2016;16:e35–41. 10.18295/squmj.2016.16.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World health Organization (WHO) Thinking healthy a manual for psychosocial management for perinatal depression, 2015. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/152936/1/WHO_MSD_MER_15.1_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 [Accessed 17 Apr 2018].

- 6. World Health Organization (WHO) Who interventions for common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. who, 2013. Available: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/91/8/12-109819/en/ [Accessed 31 Dec 2018]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7. O’Connor E, Rossom R, Henninger M, et al. . Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartum women. JAMA 2016;315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. . Screening for depression in adults. JAMA 2016;315 10.1001/jama.2015.18392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chorwe-Sungani G, Chipps J. A systematic review of screening instruments for depression for use in antenatal services in low resource settings. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17 10.1186/s12888-017-1273-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yonkers KA, Smith MV, Gotman N, et al. . Typical somatic symptoms of pregnancy and their impact on a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2009;31:327–33. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nylen KJ, Williamson JA, O’Hara MW, et al. . Validity of somatic symptoms as indicators of depression in pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health 2013;16:203–10. 10.1007/s00737-013-0334-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martins Brancaglion MY, Martins Brancaglion MY, Nogueira Cardoso M, et al. . What is the best tool for screening antenatal depression? J Affect Disord 2015;178:12–17. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holcomb WL, Stone LS, Lustman PJ, et al. . Screening for depression in pregnancy: characteristics of the Beck depression inventory. Obstet Gynecol 1996;88:1021–5. 10.1016/S0029-7844(96)00329-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Park J-hwan, Karmaus W, Zhang H. Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive symptoms in Korean women throughout pregnancy and in postpartum period. Asian Nurs Res 2015;9:219–25. 10.1016/j.anr.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vázquez MB, Míguez MC. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale as a screening tool for depression in Spanish pregnant women. J Affect Disord 2019;246:515–21. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thompson O, Ajayi I. Prevalence of antenatal depression and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in Abeokuta North local government area, Nigeria. Depress Res Treat 2016;2016:1–15. 10.1155/2016/4518979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Waldie KE, Peterson ER, D'Souza S, et al. . Depression symptoms during pregnancy: evidence from growing up in New Zealand. J Affect Disord 2015;186:66–73. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Usuda K, Nishi D, Okazaki E, et al. . Optimal cut-off score of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale for major depressive episode during pregnancy in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2017;71:836–42. 10.1111/pcn.12562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ministry of public health (MOPH). Qatar health report 2013. Qatar: MOPH 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Qatar Statistics Authority (QSA) Planning and statistics authority (PSA). Qatar statistics authority census, 2010. Available: www.qsa.gov.qa [Accessed 29 May 2018].

- 21. Ministry of public health (MOPH). Qatar National health strategy 2018-2022. MOPH:P10–14. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Primary health care Corporation (PHCC). Corporate strategic plan 2019-2023. PHCC 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Primary Health Care Corporation (PHCC) Antenatal care report. Doha: primary health care Corporation. PHCC 2012.

- 24. Mathers N, Fox N. Surveys and Questionnaires. The NIHRRDS for the East Midlands / Yorkshire & the Humber. The NIHR Research Design Service for Yorkshire & the Humber 2007.

- 25. Cox JL, Holden JM, Segovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hendrick V. Psychiatric disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum. 14 Dordrecht: Springer, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Harnett Sheehan K, et al. . The validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview (mini) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. European Psychiatry 1997;12:232–41. 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83297-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Onah MN, Field S, Bantjes J, et al. . Perinatal suicidal ideation and behaviour: psychiatry and adversity. Arch Womens Ment Health 2017;20:321–31. 10.1007/s00737-016-0706-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pettersson A, Modin S, Wahlström R, et al. . The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview is useful and well accepted as part of the clinical assessment for depression and anxiety in primary care: a mixed-methods study. BMC Fam Pract 2018;19 10.1186/s12875-017-0674-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsai AC, Scott JA, Hung KJ, et al. . Reliability and validity of instruments for assessing perinatal depression in African settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e82521 10.1371/journal.pone.0082521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Su K-P, Chiu T-H, Huang C-L, et al. . Different cutoff points for different trimesters? the use of Edinburgh postnatal depression scale and Beck depression inventory to screen for depression in pregnant Taiwanese women. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2007;29:436–41. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American psychiatry association (APA). Structured clinical interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5). Appi.org, 2017. Available: https://www.appi.org/products/structured-clinical-interview-for-dsm-5-scid-5 [Accessed 25 Dec 2018].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.