Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the long-term efficacy of hydrophilic and lipophilic statin therapy for cardiovascular outcomes in Asian diabetic patients.

Method:

Newly diagnosed cases of type 2 diabetes during the period from January 2000 to December 2011 were divided into 2 cohorts on the basis of their statin use, namely hydrophilic statin and lipophilic statin. We used Cox proportional hazard regression models to analyze the risks of cardiovascular outcomes.

Result:

In this study, 12 896 patients used statin, including 4259 patients using hydrophilic statin and 8637 patients using lipophilic statin. With 12-year follow-up, higher incidence rate of coronary artery disease and stroke was noted in the lipophilic statin use instead of hydrophilic statin use.

Conclusion:

According to our long-term cohort study, hydrophilic statin use may be a better choice than lipophilic statin to reduce cardiovascular events in Asian diabetic patients.

Keywords: hydrophilic, lipophilic, statin, diabetes

Introduction

Statins are hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors, widely prescribed for various types of dyslipidemia to reduce cardiovascular risk. Most clinical guidelines recommend statin use for primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention or treatment.1,2 Diabetes is one of the high-risk factors for cardiovascular disease, as is stated in clinical guidelines.1,2 One study published in 1998 showed that diabetes can be considered as a myocardial infarction or a risk equivalent state.3 A review article presented the links between diabetes and cardiovascular disease.4 Consistent with the findings of these studies, statins have been prescribed for diabetic patients worldwide. However, there are numerous subtypes of statin exhibiting structural differences, and these differences cause various pharmacokinetics or efficacy. In general, statins are classified into hydrophilic or lipophilic groups on the basis of tissue selectivity. In our studies, there were rosuvastatin and pravastatin in the hydrophilic group and there were atorvastatin, simvastatin, fluvastatin, and lovastatin in the lipophilic group. No standard recommendations exist for selecting a hydrophilic or lipophilic statin in clinical practice. Our 12-year follow-up study was designed to enable evaluating the benefits of hydrophilic or hydrophobic statins for diabetic patients in Asia.

Methods

Data Source

The universal National Health Insurance (NHI) program was implemented in Taiwan in March 1995 as a compulsory single-payer health-care system. By 2011, it had achieved a coverage rate of approximately 99.9% of the 23.22 million Taiwanese citizens.5,6 The substantial computerized database that became the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) was derived from the NHI program and is maintained by the National Health Research Institutes. The identification numbers of all people in the NHIRD are encrypted to protect privacy. In this study, we used the data set from the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000 (LHID2000). It contains the original claims data of 1 000 000 claims, randomly sampled from the 2000 Registry for Beneficiaries of the NHIRD, which has been demonstrated to be representative of the entire population. Patient diagnoses were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). Taiwan launched an NHI in 1995, operated by a single buyer, the government. Medical reimbursement specialists and peer review should scrutinize all insurance claims. The diagnoses of cardiovascular events were based on the ICD-9 codes which were judged and determined by related specialists and physicians according to the standard clinical criteria. Therefore, the diagnoses and codes for cardiovascular events used in this study should be correct and reliable.

Ethics Statement

The NHIRD encrypts patient personal information to protect privacy and provides researchers with anonymous identification numbers associated with relevant claims information, including sex, date of birth, medical services received, and prescriptions. Therefore, patient consent is not required to access the NHIRD. This study was approved to fulfill the condition for exemption by the institutional review board (IRB) of China Medical University (CMUH-104-REC2-115-CR4). The IRB also specifically waived the consent requirement.

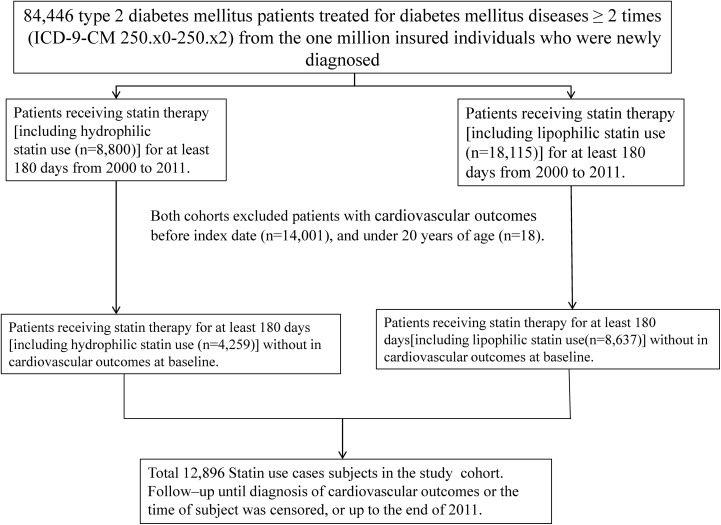

Sampled Participants

Figure 1 shows the selection process of the participants in the study cohorts. The study patients were identified from the LHID2000 as newly diagnosed cases with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM; ICD-9-CM 250.x0 and 250.x2) during the period from January 2000 to December 2011. The patients with T2DM were divided into 2 cohorts according to their statin use: the hydrophilic statin cohort included patients who had received hydrophilic statin therapy for at least 6 months (180 days) and the lipophilic statin cohort included patients who had received lipophilic statin therapy for at least 6 months (180 days). Among the 2 cohorts, patients with a history of coronary artery disease (CAD; ICD-9-CM codes 410-414), acute myocardial infarction (AMI; ICD-9-CM code 410), congestive heart failure (CHF; ICD-9-CM code 428), atrial fibrillation (AF; ICD-9-CM code 427.31), and stroke (ICD-9-CM codes 430-438) before the index date, patients under 20 years of age, and those with incomplete medical information were excluded.

Figure 1.

Selection process of the participants in the study cohorts.

Outcome

Cardiovascular events included CAD, AMI, CHF, AF, and stroke. All study patients were followed from the index date to the development of cardiovascular events, loss to follow-up, withdrawal from the insurance program, or December 31, 2011.

Baseline Variables

We obtained baseline variables investigated in this study, including sociodemographic status (including sex, age, monthly income, and urbanization level), comorbidities of hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes 401 to 405), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ICD-9-CM codes 491, 492, 496), chronic kidney disease (ICD-9-CM codes 580-589), and arrhythmia (ICD-9-CM code 426, 427), and medications including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, β-blockers, metformin, aspirin, and insulin.

Statistical Analysis

We compared the distributions of sociodemographic status, comorbidities, and medications between the cohorts with hydrophilic statin and with lipophilic statin use by using a Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables and a Student t test for continuous variables. The overall sex-specific incidence densities of cardiovascular events were measured among the 2 cohorts. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for cardiovascular events in patients with T2DM with lipophilic statin use in relationship to the hydrophilic statin use. The multivariable models simultaneously adjusted for sociodemographic status, comorbidities, and medications. The cumulative incidence of cardiovascular events among the 2 cohorts was plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method and the difference was tested using a log-rank test. All data analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) for Windows. The level of significance was set at .05, and the tests were 2-tailed.

Results

This study involved 4259 patients who used hydrophilic statin and 8637 patients who used lipophilic statin (Table 1). Among the 2 cohorts, most patients were aged 50 to 64 years (50.7% in the hydrophilic statin use cohort and 49.4% in the lipophilic statin use cohort) and were female (52.6% in the hydrophilic statin use cohort and 52.1% in the lipophilic statin use cohort). Compared with patients in the lipophilic statin cohort, the patients in the hydrophilic statin cohort exhibited a higher tendency to have high monthly incomes (34.3% vs 32.0% for monthly income ≥20 000) and live in urbanized areas (64.8% vs 61.0% in urbanization levels 1 and 2). Comorbidities were more prevalent in the hydrophilic statin cohort than in the lipophilic statin cohort, particularly hypertension (69.3% vs 65.4%). The prevalence of medications was higher in the hydrophilic statin cohort than in the lipophilic statin cohort.

Table 1.

Comparison of Demographics and Comorbidity Between Hydrophilic and Lipophilic Statin Use.a

| Type 2 Diabetes | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophilic Statin Use (N = 4259) | Lipophilic Statin Use (N = 8637) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age, years | .001 | ||||

| ≤49 | 919 | 21.6 | 2103 | 24.4 | |

| 50-64 | 2158 | 50.7 | 4264 | 49.4 | |

| >65 | 1182 | 27.8 | 2270 | 26.3 | |

| Mean (SD)b | |||||

| Gender | .59 | ||||

| Women | 2240 | 52.6 | 4499 | 52.1 | |

| Men | 2019 | 47.4 | 4138 | 47.9 | |

| Monthly income (NTD) | .027 | ||||

| <15 000 | 766 | 18.0 | 1604 | 18.6 | |

| 15 000-19 999 | 2031 | 47.7 | 4272 | 49.5 | |

| ≥20 000 | 1462 | 34.3 | 2761 | 32.0 | |

| Urbanization levelc | <.001 | ||||

| 1 (highest) | 1422 | 33.4 | 2667 | 30.9 | |

| 2 | 1336 | 31.4 | 2600 | 30.1 | |

| 3 | 770 | 18.1 | 1479 | 17.1 | |

| 4 | 731 | 17.2 | 1891 | 21.9 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Hypertension | 2951 | 69.3 | 5651 | 65.4 | <.001 |

| COPD | 480 | 11.3 | 956 | 11.1 | .73 |

| CKD | 578 | 13.6 | 1106 | 12.8 | .22 |

| Arrhythmia | 242 | 5.68 | 470 | 5.44 | .57 |

| Medications | |||||

| ACEI | 2157 | 50.7 | 4106 | 47.5 | <.001 |

| AIIRBs | 1939 | 45.5 | 2880 | 33.3 | <.001 |

| β-Blockers | 2240 | 52.6 | 4311 | 49.9 | .004 |

| Metformin | 3518 | 82.6 | 6894 | 79.8 | <.001 |

| Aspirin | 1778 | 41.8 | 3197 | 37.0 | <.001 |

| Insulin | 2591 | 60.8 | 5074 | 58.8 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; AIIRB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; NTD, new Taiwan dollar; SD, standard deviation.

a Chi-square test comparing subjects with hydrophilic statin use and lipophilic statin use.

b T test.

c The urbanization level was categorized by the population density of the residential area into 4 levels, with level 1 as the most urbanized and level 4 as the least urbanized.

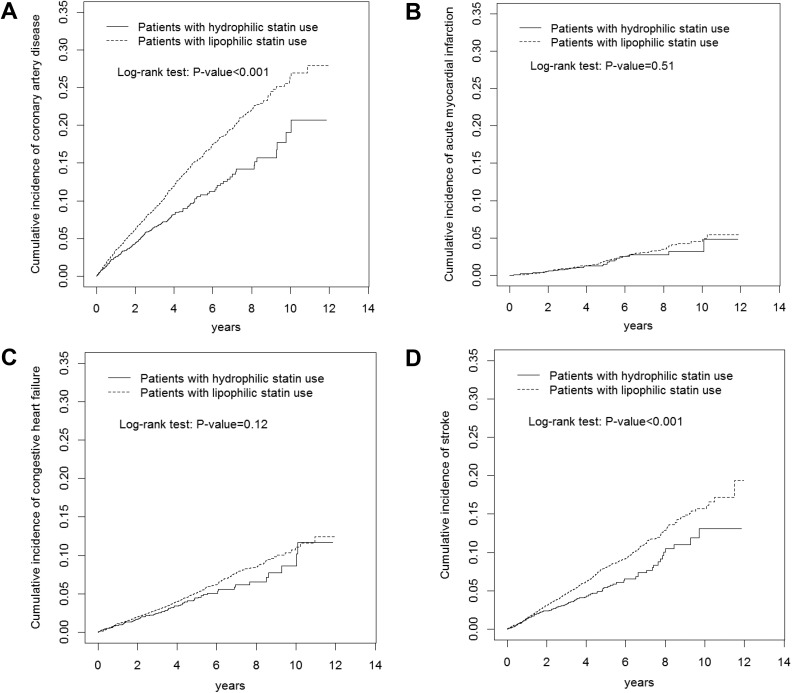

With 12-year follow-up, Kaplan-Meier analysis was adopted to calculate the cumulative incidence of CAD, AMI, CHF, and stroke, as shown in Figure 1. The cumulative incidence of CAD and stroke was higher in patients of the lipophilic statin cohort than in those of the hydrophilic statin cohort (Figure 2A, log-rank test: P < .001, Figure 2D, log-rank test: P < .001).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidences of coronary artery disease (A), acute myocardial infarction (B), congestive heart failure (C), and stroke (D) in patients with hydrophilic statin use, and with lipophilic statin use, compared to patients without statin use.

The overall incidences of CAD were 21.6 and 31.6 per 1000 person-years in the hydrophilic statin and lipophilic statin cohorts, respectively (Table 2). After adjusting for age, sex, comorbidities, and medication, the risk of CAD and stroke in the lipophilic statin use cohort was 54% and 46% higher (significantly) than in the hydrophilic statin use cohort. Among men patients, the risk of CAD in the lipophilic statin use cohort was 49% higher (significantly) than in the hydrophilic statin use cohort. Among women patients, the risk of CAD, CHF, and stroke in the lipophilic statin use cohort was 58%, 43%, and 66% higher (significantly) than in the hydrophilic statin use cohort.

Table 2.

Comparisons of Incidence Densities and Hazard Ratio of Cardiovascular Outcomes in Study Cohorts.

| Hydrophilic Statin Use | Crude HRb (95% CI) | Adjusted HRc (95% CI) | Lipophilic Statin Use | Crude HRb (95% CI) | Adjusted HRc (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Ratea | Case | Ratea | |||||

| All | ||||||||

| CAD | 262 | 21.6 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 1000 | 31.6 | 1.48 (1.29-1.69)d | 1.54 (1.35-1.77)d |

| AMI | 41 | 3.19 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 140 | 3.98 | 1.12 (0.79-1.60) | 1.12 (0.79-1.59) |

| CHF | 113 | 8.93 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 373 | 10.8 | 1.18 (0.96-1.46) | 1.23 (0.99-1.52) |

| AF | 28 | 2.17 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 92 | 2.61 | 1.11 (0.72-1.69) | 1.15 (0.75-1.76) |

| Stroke | 147 | 11.7 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 560 | 16.5 | 1.39 (1.16-1.67)d | 1.46 (1.22-1.76)d |

| Men | ||||||||

| CAD | 121 | 22.1 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 461 | 31.2 | 1.44 (1.17-1.76)d | 1.49 (1.22-1.83)d |

| AMI | 22 | 3.82 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 73 | 4.48 | 1.07 (0.66-1.74) | 1.06 (0.65-1.72) |

| CHF | 53 | 9.31 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 145 | 9.03 | 0.95 (0.69-1.30) | 0.99 (0.72-1.36) |

| AF | 14 | 2.42 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 40 | 2.44 | 0.88 (0.47-1.62) | 0.92 (0.50-1.72) |

| Stroke | 73 | 13.0 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 253 | 16.1 | 1.21 (0.93-1.58) | 1.26 (0.97-1.64) |

| Women | ||||||||

| CAD | 141 | 21.2 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 539 | 32.0 | 1.52 (1.26-1.83)d | 1.58 (1.31-1.90)d |

| AMI | 19 | 2.68 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 67 | 3.55 | 1.17 (0.70-1.95) | 1.18 (0.70-1.98) |

| CHF | 60 | 8.61 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 228 | 12.4 | 1.40 (1.06-1.87)e | 1.43 (1.07-1.91)e |

| AF | 14 | 1.97 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 52 | 2.75 | 1.33 (0.74-2.42) | 1.36 (0.74-2.48) |

| Stroke | 74 | 10.7 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) | 307 | 17.0 | 1.57 (1.22-2.03)d | 1.66 (1.29-2.15)d |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; AF, atrial fibrillation; AIIRB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HR, hazard ratio.

a Rate, incidence rate, per 1000 person-years.

b Crude HR, relative hazard ratio.

c Adjusted HR: Multivariable analysis including age, sex, monthly income, urbanization level, comorbidity of hypertension, COPD, CKD, and arrhythmia, and medication of ACEI, AIIRB, β-blockers, metformin, aspirin, and insulin.

d P < .001.

e P < .05.

The risk of CAD was higher in men with lipophilic statin use (HR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.43-2.11) and women with lipophilic statin use (HR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.31-1.91) than in women with hydrophilic statin use (Table 3). Compared with women who used hydrophilic statin, men who used lipophilic statin exhibited a higher risk of AMI (HR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.04-2.91). Compared with women who used hydrophilic statin, men who used lipophilic statin were 1.87-fold more likely to develop stroke (95% CI = 1.44-2.43), followed by women who used lipophilic statin (HR = 1.66, 95% CI = 1.29-2.14) and men who used lipophilic statin (HR = 1.48, 95% CI = 1.07-2.05).

Table 3.

Development of CAD, AMI, and Stroke in Patients With Statin Use Associated With Gender in Cox Regression Analysis.

| Hydrophilic Statin Use | Lipophilic Statin Use | Gender | N | Case | Ratea | Crude HRb (95% CI) | Adjusted HRc (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAD | |||||||

| Yes | No | Women | 2240 | 141 | 21.2 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | No | Men | 2019 | 121 | 22.1 | 1.04 (0.82-1.32) | 1.16 (0.91-1.48) |

| No | Yes | Women | 4499 | 539 | 32.0 | 1.52 (1.27-1.83)d | 1.58 (1.31-1.91)d |

| No | Yes | Men | 4138 | 461 | 31.2 | 1.48 (1.23-1.79)d | 1.74 (1.43-2.11)d |

| AMI | |||||||

| Yes | No | Women | 2240 | 19 | 2.68 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | No | Men | 2019 | 22 | 3.82 | 1.48 (0.80-2.73) | 1.65 (0.89-3.07) |

| No | Yes | Women | 4499 | 67 | 3.55 | 1.20 (0.72-2.00) | 1.19 (0.71-1.99) |

| No | Yes | Men | 4138 | 73 | 4.48 | 1.55 (0.93-2.57) | 1.74 (1.04-2.91)e |

| Stroke | |||||||

| Yes | No | Women | 2240 | 74 | 10.7 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | No | Men | 2019 | 73 | 13.0 | 1.22 (0.89-1.69) | 1.48 (1.07-2.05)e |

| No | Yes | Women | 4499 | 307 | 17.0 | 1.57 (1.21-2.02)d | 1.66 (1.29-2.14)d |

| No | Yes | Men | 4138 | 253 | 16.1 | 1.49 (1.15-1.93)e | 1.87 (1.44-2.43)d |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; AIIRB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HR, hazard ratio.

a Rate, incidence rate, per 1,000 person-years.

b Crude HR, relative hazard ratio.

c Adjusted HR: multivariable analysis including age, sex, monthly income, urbanization level, comorbidity of hypertension, COPD, CKD, and arrhythmia, and medication of ACEI, AIIRB, β-blockers, metformin, aspirin, and insulin.

d p < 0.001.

e p < 0.05 .

Discussion

In our study, we separated 2 statin group cohorts including hydrophilic statin cohort such as rosuvastatin and pravastatin users and lipophilic statin cohort such as atorvastatin, simvastatin, fluvastatin, and lovastatin users. Patients in the hydrophilic statin cohort were mostly older than 50 years old, female, had a high monthly income, lived in urbanized areas, and exhibited comorbidities with hypertension. Multiple medications such as antihypertension, oral antidiabetic agents, and insulin were prescribed in our hydrophilic statin cohort.

Sex and Hydrophilic or Lipophilic Statin

The Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration suggested that statin therapy is of similar effectiveness in the prevention of major vascular events among men and women.7 One study showed that high low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels were significantly associated with cardiovascular events among men and women, but there was a stronger association for stroke in women and for coronary heart disease death in men.8 In our study, most cardiovascular events such as CAD and stroke in patients used lipophilic statin. Among men patients, the risk of CAD in the lipophilic statin use cohort was significantly higher than other men in the hydrophilic statin use cohort.

Among women patients, the risk of CAD, CHF, and stroke in the lipophilic statin use cohort was significantly higher than other women in the hydrophilic statin use cohort. Different races or hormone effects in women are possible explanations. We suggest that hydrophilic statin may be the optimal choice for diabetic Asian for reducing the occurrence of cardiovascular events.

Hydrophilic or Lipophilic Statins for Cardiovascular Events

In our study, no benefit was observed for AF in diabetic patients of both statin cohorts. Atrial fibrillation is another independent risk factor for cardiovascular death.9 However, previous studies have shown that lipophilic statin with atorvastatin was superior to hydrophilic statin with pravastatin on AF issue.10 Statin therapy for CHF was considered controversial in other studies.11,12 In our study, no benefit was observed in both statin cohorts and both sexes. A 2-year comparison of hydrophilic and lipophilic statin studies showed no significant difference in AMI.13 A 1-year cardiovascular outcomes study suggested that lipophilic statin was superior for AMI.14 However, another study showed that hydrophilic statin was superior to lipophilic statin in the prevention of new-Q wave formation in patients with AMI.15 Our long-term study showed that hydrophilic statin was superior to lipophilic statin in diabetic patients with CAD, and stroke.

Hydrophilic Versus Lipophilic Statins

In our study, the incidence of CAD and stroke was strongly associated in the lipophilic statin cohort; for the male group, the incidences of CAD were higher in the lipophilic statin cohort, but for the female group, the incidences of CAD, CHF, and stroke were higher in the lipophilic statin cohort. In addition to a lipid-lowering effect, numerous pleiotropic effects are associated with statin use, such as a reduction in inflammation and vascular thrombus and an improvement in endothelial functions.16–18 Hydrophilic statin exhibits lower tissue absorption and lower dependence on the cytochrome P450 enzyme compared with lipophilic statin; therefore, fewer side effects occur in the use of hydrophilic statin.19 According to one study, compared with lipophilic statin, hydrophilic statin was superior in attenuating inflammation.20 These are the possible mechanisms explaining our cardiovascular outcomes. The retrospective cohort study is usually lower evidence than the randomized controlled trials because a retrospective cohort study is subject to have many unknown or uncontrolled confounding factors. Further study is needed to evaluate the association between hydrophilic and lipophilic statin.

Limitations

The retrospective cohort study is usually lower evidence than the randomized controlled trials because a retrospective cohort study is subject to have many unknown or uncontrolled confounding factors. Another limitation of our study was that cardiovascular diseases are asymptomatic or underdiagnosed. Based on the NHIRD, we could not collect patients’ other risk factors for cardiovascular events such as lifestyle, alcohol consumption, salt intake, nutritional status, weight and height, and smoking habit. Because of the lack of individual laboratory data (such as cholesterol, LDL or high-density lipoprotein, fasting blood sugar, or hemoglobin A1C [HbA1C]) and for the study subjects in the NHIRD, we did not do analyses of the cholesterol reduction after different statin treatments and measures of diabetes (eg, fasting blood glucose or HbA1C) between these subgroups. Image data such as radiologic results or heart echo finding were also not offered by NHIRD. Of course, if the patient could absolutely follow these doctors’ order to regularly receive the statin therapy (patient compliance) should be considered as one of the other study limitations for this study.

Conclusion

Hydrophilic and lipophilic statin therapy for dyslipidemia is still controversial in clinical practice. According to our long-term cohort study, hydrophilic statin use may be a better choice than lipophilic statin to reduce cardiovascular events in Asian diabetic patients.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Hsin-Hung Chen and Shang-Yi Li equally contributed to this work. All authors have contributed substantially to, and are in agreement with the content of, the manuscript. Shang-Yi Li, Hsin-Hung Chen, and Chia-Hung Kao contributed to conception/design; Chia-Hung Kao contributed to provision of study materials; all authors contribute to collection and/or assembly of data; data analysis and interpretation; manuscript preparation; and gave final approval of the manuscript. Chia-Hung Kao is the guarantor of the paper, taking responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study is supported in part by Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (MOHW108-TDU-B-212-133004); China Medical University Hospital (DMR-107-192); Academia Sinica Stroke Biosignature Project (BM10701010021); MOST Clinical Trial Consortium for Stroke (MOST 107-2321-B-039-004-); Tseng-Lien Lin Foundation, Taichung, Taiwan; and Katsuzo and Kiyo Aoshima Memorial Funds, Japan. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. No additional external funding was received for this study.

ORCID iD: Chia-Hung Kao  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6368-3676

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6368-3676

References

- 1. Rabar S, Harker M, O’Flynn N, Wierzbicki AS; Guideline Development Group. Lipid modification and cardiovascular risk assessment for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2014;349:g4356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 pt B):2889–2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haffner SM, Lehto S, Rönnemaa T, Pyörälä K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(4):229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sattar N. Revisiting the links between glycaemia, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Diabetologia. 2013;56(4):686–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Health Research Institute: National Health Insurance Research Database, Taiwan. http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/en/index.htm. Accessed 2015.

- 6. Directorate General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Republic of China: Statistical Yearbook of Republic of China 2011. Population by sex, rate of population increase, average persons per household, density and natural increase rate. http://eng.stat.gov.tw/public/data/dgbas03/bs2/yearbook_eng/y008.pdf. Accessed 2015.

- 7. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration, Fulcher J, O’Connell R, Voysey M, et al. Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: meta-analysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;385(9976):1397–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hsue PY, Bittner VA, Betteridge J, et al. Impact of female sex on lipid lowering, clinical outcomes, and adverse effects in atorvastatin trials. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(4):447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB, Levy D. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1998;98(10):946–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Komatsu T, Tachibana H, Sato Y, Ozawa M, Kunugita F, Nakamura M. Long-term efficacy of upstream therapy with lipophilic or hydrophilic statins on antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: comparison between atorvastatin and pravastatin. Int Heart J. 2011;52(6):359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oh J, Kang SM, Hong N, et al. Effect of high-dose statin loading on biomarkers related to inflammation and renal injury in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. Randomized, controlled, open-label, prospective pilot study. Circ J. 2014;78(10):2447–2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Takano H, Mizuma H, Kuwabara Y, et al. Effects of pitavastatin in Japanese patients with chronic heart failure: the Pitavastatin Heart Failure Study (PEARL Study). Circ J. 2013;77(4):917–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Izawa A, Kashima Y, Miura T, et al. Assessment of lipophilic vs. hydrophilic statin therapy in acute myocardial infarction—ALPS-AMI study. Circ J. 2015;79(1):161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim MC, Ahn Y, Jang SY, et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes of hydrophilic and lipophilic statins in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Korean J Intern Med. 2011;26(3):294–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sakamoto T, Kojima S, Ogawa H, et al. Usefulness of hydrophilic vs lipophilic statins after acute myocardial infarction: subanalysis of MUSASHI-AMI. Circ J. 2007;71(9):1348–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Laufs U, La Fata V, Plutzky J, Liao JK. Upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by HMG CoA reductase inhibitors. Circulation. 1998;97(12):1129–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aikawa M, Rabkin E, Sugiyama S, et al. An HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, cerivastatin, suppresses growth of macrophages expressing matrix metalloproteinases and tissue factor in vivo and in vitro. Circulation. 2001;103(2):276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dangas G, Badimon JJ, Smith DA, et al. Pravastatin therapy in hyperlipidemia: effects on thrombus formation and the systemic hemostatic profile. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(5):1294–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McKenney JM. Pharmacologic characteristics of statins. Clin Cardiol. 2003;26(4 suppl 3):III32–III38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kai T, Arima S, Taniyama Y, Nakabou M, Kanamasa K. Comparison of the effect of lipophilic and hydrophilic statins on serum adiponectin levels in patients with mild hypertension and dyslipidemia: Kinki Adiponectin Interventional (KAI) Study. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2008;30(7):530–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]