Abstract

Introduction

Development and implementation of appropriate health policy is essential to address the rising global burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). The aim of this study was to evaluate existing health policies for integrated prevention/management of NCDs among Member States of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). We sought to describe policies’ aims and strategies to achieve those aims, and evaluate extent of integration of musculoskeletal conditions as a leading cause of global morbidity.

Methods

Policies submitted by OECD Member States in response to a World Health Organization (WHO) NCD Capacity Survey were extracted from the WHO document clearing-house and analysed following a standard protocol. Policies were eligible for inclusion when they described an integrated approach to prevention/management of NCDs. Internal validity was evaluated using a standard instrument (sum score: 0–14; higher scores indicate better quality). Quantitative data were expressed as frequencies, while text data were content-analysed and meta-synthesised using standardised methods.

Results

After removal of duplicates and screening, 44 policies from 30 OECD Member States were included. Three key themes emerged to describe the general aims of included policies: system strengthening approaches; improved service delivery; and better population health. Whereas the policies of most countries covered cancer (83.3%), cardiovascular disease (76.6%), diabetes/endocrine disorders (76.6%), respiratory conditions (63.3%) and mental health conditions (63.3%), only half the countries included musculoskeletal health and pain (50.0%) as explicit foci. General strategies were outlined in 42 (95.5%) policies—all were relevant to musculoskeletal health in 12 policies, some relevant in 27 policies and none relevant in three policies. Three key themes described the strategies: general principles for people-centred NCD prevention/management; enhanced service delivery; and system strengthening approaches. Internal validity sum scores ranged from 0 to 13; mean: 7.6 (95% CI 6.5 to 8.7).

Conclusion

Relative to other NCDs, musculoskeletal health did not feature as prominently, although many general prevention/management strategies were relevant to musculoskeletal health improvement.

Keywords: policy, integrated care, health system, non-communicable, global, musculoskeletal

Key questions.

What is already known?

Health policy is recognised as essential to build capacity in health systems to respond to the increasing burden associated with non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

Although musculoskeletal conditions and persistent pain are leading causes of global morbidity, global action plans and monitoring frameworks for NCDs have historically not explicitly included these conditions.

What are the new findings?

Health policies for integrated prevention/management of NCDs among OECD countries typically address NCDs closely aligned to mortality, in alignment with target 3.4 of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Musculoskeletal health conditions and persistent pain feature less prominently than other NCDs.

The aims and strategies for integrated management of NCDs among OECD Member States align with the WHO System Building Blocks and Integrated People-Centred Health Services frameworks.

What do the new findings imply?

There is close alignment between NCD global action plans and monitoring frameworks and the NCD policy foci of OECD Member States.

While many general strategies outlined in the included policies are relevant to addressing musculoskeletal health, without an explicit focus in national policy and global strategies meaningful improvements in global morbidity may not be achievable.

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) represent one of the most important and urgent threats to human health globally,1–3 with a disproportionate and increasing burden experienced by older people and those in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). The burden of disease attributed to NCDs now far outweighs that associated with communicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional deficiency diseases in most countries.4 The impacts of NCDs are significant and wide-reaching. These include direct health consequences (such as premature death, reduced functional ability, impaired quality of life) and also dramatic social and economic sequelae that impact human capital and prosperity leading to poverty and threats to achieving targets of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).3 5–7

On a background of global population ageing and an increasing prevalence of risk factors for the development of NCDs (eg, harmful use of alcohol and tobacco, physical inactivity, poor diet, and pollution), the magnitude of the burden of disease attributed to NCDs is expected to increase and further threaten the sustainability of health systems.8 9 In the most recent analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study, NCDs accounted for the majority (62%) of total burden of disease globally, expressed as disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), representing an increase of 16% from 2007 to 2017.4 NCDs as a major contributor to total disease burden was observed across all economies. As a disaggregated DALY burden, NCDs accounted for the greatest proportion of deaths in 2017 (73%), reflecting an increase of 23% from 2007 to 201710 and 80% of the total years lived with disability (YLDs), or morbidity burden, in 2017.9 Critically, the number YLDs attributed to NCDs from 1990 to 2017 has risen by 61%.9 In particular, musculoskeletal conditions are a major contributor to the NCD disability burden, particularly in association with ageing.9 11 12 YLDs for musculoskeletal conditions have risen by 20% from 2007 to 2017 and low back pain remains the single leading cause of global disability since 1990.9 Recent systematic review evidence suggests that a third to a half of the population in the UK lives with chronic pain, the majority of which is musculoskeletal in aetiology,13 mirroring trends in LMICs.14 Despite the identified burden of disease of musculoskeletal pain, and evidence of pain as a key determinant of disability,15 historically it has not been integrated into NCD prevention and management policy or strategy in most countries, or by the World Health Organization (WHO).11 16

Against this backdrop, health systems globally are often ill-equipped to effectively address prevention and management of NCDs.2 6 17 18 Urgent attention to system strengthening approaches to more effectively address prevention and management of NCDs and support healthy ageing, is therefore, well justified.6 19 While strengthening approaches should be nationally-specific, global leadership and support from high-income economies, such as Member States of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), is important.

However, multiple barriers have been identified as limiting progress in addressing the burden of NCDs: political will, appropriate policy, commercial forces, inadequate technical and operational capacity, insufficient financing, inadequate action to the social determinants of health and lack of accountability.20 The Lancet Global Health Commission argues that health system strengthening approaches that include formulation of national policy to prioritise prevention and management of NCDs is essential,2 mirroring objectives of the WHO global action plan21 and other calls for urgent policy formulation.11 22–25 Despite the identified burden of disease, political action on NCDs has been criticised and deemed inadequate to ensure global health security into the future and achievement of the 2030 targets for SDG 3.4 will not be achieved.1 6 22

Since NCDs often co-occur, particularly in the context of ageing,26 and many share common behavioural and environmental risk factors, system reform for NCDs should typically be approached in an integrated manner at both system and service levels, rather than in disease-specific siloes.18 The WHO has provided guidance, or ‘best buys’,27 on how to prevent and manage NCDs as part of the Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020.21 This Action Plan and the targets for SDG 3.4 are largely aligned to mortality reduction for cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and lung disease. While imperative, this focus inadequately considers the profound morbidity burden associated with NCDs, especially musculoskeletal conditions, and contemporary global health estimate data pointing to an increasing life expectancy associated with poor health.4

The aim of this study was to evaluate health policies for integrated prevention/management of NCDs among Member States of the OECD. Specifically, we sought to describe the aims, and strategies to achieve those aims, among policies and evaluate the extent to which musculoskeletal conditions were integrated. We limited our analysis to OECD Member States as a starting point for this research, recognising that these nations are considered policy leaders and work to support global social and economic development.

Methods

Design

Systematic document review and data analysis of health policies on integrated NCD prevention or management of OECD Member States that participated in a WHO NCD Country Capacity Survey.22

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not directly involved in the design or execution of the research. The research was co-designed with representatives from patient advocacy organisations (JGP, AC) and government (JGP, MLD, YS).

Eligibility for inclusion

Health policies of the 36 OCED Member States that reported on integrated NCD prevention/management and were submitted to WHO between 2015 and 2017 as part of a WHO NCD Country Capacity Survey were eligible for inclusion. We defined ‘policy document’ as any national or regional health policy, strategy or action plan submitted by a country in response a WHO NCD Country Capacity Survey, consistent with aligned research.28

Document selection

A document repository of Member States’ policies, strategies and action plans for NCDs and their risk factors, NCD clinical guidelines, and NCD legislation and regulation, submitted in response to periodic WHO NCD Country Capacity Survey was created by the WHO in 2016 (https://extranet.who.int/ncdccs/documents/db). We used this document clearing-house to identify and download the relevant policy document(s) for each country. Where documents were not available from the clearing-house for some countries (Austria, Finland, Greece, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Turkey), the WHO secretariat was contacted in 2018 to confirm that no submissions were made from these countries. We confirmed that Finland, Greece, Luxembourg and New Zealand had not made submissions, while policies were under development (in 2017) for Austria and Turkey. We therefore undertook a desktop internet search for relevant policies from the Ministries of Health of Austria (in German) and Turkey (in English) and identified the relevant Turkish policy. No specific policy for NCD prevention or management was identified for Austria, other than 2013 action plans for nutrition and physical activity.29 30 Since policies were not under development for Finland, Greece, Luxembourg or New Zealand, internet searches were not undertaken for these nations, although we recognise that potentially suitable policies may exist.

Document review and data extraction

A multidisciplinary and multilingual team of 13 reviewers was assembled to review documents and extract data (five from Australia; five from Western Europe; one from Eastern Europe; one from Asia and one from North America). For those documents published in a language outside the language competencies of the review team, online translation software was used to translate the text to English (https://www.onlinedoctranslator.com/en/).

A standardised data extraction template was developed to ensure a consistent approach to document reviews and data extraction (online supplementary file 1). The data extraction template collected data on: publication information; vision and scope of the policy; health conditions explicitly included; strategies/actions proposed to achieve the objectives/aims of the policy; and the extent of explicit integration of musculoskeletal conditions, mobility/functional impairment or persistent non-cancer pain within the scope of prevention/management for NCDs. The template was initially piloted on nine policies across seven countries between four reviewers (September–October 2018), before being revised and piloted again on two policies from one country by one reviewer (November 2018). The main review period was December 2018 to April 2019, with each reviewer assigned to one or more countries based on their language skills. A review protocol document was also prepared after the pilot phase, to accompany the data extraction sheet and guide reviewers in standardised document review and data extraction tasks.

bmjgh-2019-001806supp001.pdf (2.2MB, pdf)

Quality appraisal

A quality appraisal (internal validity) of each policy document was undertaken as a component of the review task. A quality appraisal tool using assessment criteria and a response scale established and used previously for evaluation of chronic disease policies was used.31 The tool was based on important evaluation criteria previously identified in the literature.31–33 It consisted of seven items covering seven domains reflecting best-practice policy development (background and case for change; goals; resource considerations; monitoring and evaluation; public opportunity; obligations; and potential for public health impact) and rated on a 3-point nominal response scale (scored from 0 to 2; total score range 0–14). The inter-rater reliability of the tool was assessed across nine policies in the first pilot phase. A kappa (k) statistic was computed for each domain, with 6 out of 7 categorised as fair/good (k=0.4–0.75) to excellent (k>0.75), based on thresholds recommended by Fleiss.34 The domain ‘goals’ had poor reliability (k<0.4). The inter-rater reliability of sum scores was, however, high, expressed as an intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC); ICC: 0.91 (95% CI 0.68 to 0.98).

Data analysis

Reviewers submitted their completed data extraction sheets to a project officer who quality-checked the submissions, based on a quality checklist established a priori. Simple (short-text) data were recorded verbatim, while content analysis was undertaken to analyse extensive text responses,35 using standard methods for inductive coding and meta-synthesis.36 37 Content analysis was applied to the following data fields: (1) Aim/vision of the policy. (2) Strategies to achieve the policy aims/objectives. (3) Relevance of the strategies to the prevention/management of musculoskeletal health.

For each of these three data fields, a five-step process was undertaken. First, a primary analyst (AMB) inductively developed a coding framework (first-order codes) based on the provided responses. Second, the coding framework was verified independently by two reviewers (EMGH, HS) using a 20% subset of responses, with discrepancies resolved through consensus. Third, the primary analyst coded each response against the coding framework. Fourth, coding was verified independently by two reviewers (EMGH, HS) using a 20% subset of responses, with discrepancies resolved through consensus. Discordance in coding ranged from 0% to 7% across questions. Finally, an interdisciplinary group (AMB, JGP, MLD, EMGH, HS) representing clinicians, researchers, civil society represenatives and policy makers met and familiarised themselves with the derived coding framework. These initial codes were then iteratively and inductively organised into consensus-based descriptive subthemes. We then derived new, higher-order themes that extended beyond the initial coding framework. Findings were linked back to the research questions to ensure relevance and appropriate contextualisation for a narratively reported meta-synthesis. Frequencies of first-order codes were calculated to provide an indication of overall weighting.

Results

Overview of included policies

Document selection

We identified 48 policies for inclusion across 31 OECD Member States from the WHO document clearing-house (see PRISMA-aligned flow chart, online supplementary file 2). No policies were included for five OECD Member States (Austria, Finland, Greece, Luxembourg and New Zealand). An additional six policies were identified through other means, including: one document for each of Portugal,38 Turkey39 and the Republic of Korea,40 identified through desktop internet searches (as these documents were not available in the WHO database or were outdated); and, based on advice from Public Health Canada, three documents linked to the primary Canadian policy,41–43 ‘Canadian Integrated Strategy on Healthy Living and Chronic Disease’ (N=54).44 At screening and eligibility assessment, 10 policy documents were excluded: 6 duplicates and 4 did not meet the inclusion criteria (Belgium, Canada, Israel, Italy; online supplementary file 2). Consequently, 44 policies from 30 OECD Member States were included in the final review.38–81

bmjgh-2019-001806supp002.pdf (89.7KB, pdf)

Policy characteristics and aims

A summary of included policies is provided in table 1. Policies were regionally represented as 1 (2.3%) from Oceania, 28 (63.6%) from the European Union, 5 (11.4%) from Europe, 5 (11.4%) from North America, 1 (2.3%) from South America, 1 (2.3%) from Central America and 3 (6.8%) from Asia. Forty-two (95.4%) polices originated from high-income economies and two (4.6%) from upper-income middle-income economies. All policies were national in reach; 13 (29.5%) explicitly aligned with the WHO Global Action Plan21; and 11 (25%) focused on NCD prevention only, 1 (2.3%) on NCD management only, and 32 (72.7%) on NCD prevention and management.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included policies

| Nation (income band†) | Policy title (year of publication; classification‡) | Time span | Explicit alignment with the WHO Action Plan§ (yes/no) | Focus (NCD prevention; NCD management; both) | Purpose, aim or vision |

| Australia (high) | National Strategic Framework for Chronic Conditions (2017; primary)*45 | 2017–2025 | Yes | Prevention +management |

All Australians live healthier lives through effective prevention and management of chronic conditions. |

| Belgium (high) |

Chronic Disease Plan. Integrated Health Services for Better Health (2015; primary)46 | n.s. | No | Prevention +management |

To support the improvement of the quality of life of the population, in particular people suffering from multiple chronic conditions and ensure that they can live better in their own environment (family, school, work) and the community, and can engage in active self-management of their own health. |

| Canada (high) |

Integrated Strategy on Healthy Living and Chronic Disease (2005; secondary)*44 | n.s | No | Prevention +management |

To provide a framework for the federal government to promote the health of Canadians and reduce the impact of chronic disease in Canada. |

| Canada’s Tobacco Strategy (2018; secondary)*41 | 2018–2035 | No | Prevention | To achieve a target of <5% tobacco use by 2035. | |

| Curbing Childhood Obesity: A Federal, Provincial and Territorial Framework for Action to Promote Healthy Weights (2010; primary)*42 | n.s. | No | Prevention | Canada is a country that creates and maintains the conditions for healthy weights so that children can have the healthiest possible lives. | |

| Let’s get moving: A common vision for increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary living in Canada (2018; primary)*43 | n.s. | No | Prevention | A Canada where all Canadians move more and sit less, more often. | |

| Chile (high) |

National Health Strategy to Complete the Health Objectives of the Decade (2011; primary)47 | 2011–2020 | No | Prevention +management |

Reduce the impact of chronic communicable and non-communicable disease, traffic accidents and family violence, through actions, screening and prevention strategies, improved health coverage and treatment; target risk factors for NCDs; enhance workplace health and safety and food safety; strengthen the public health system and health workforce; and build preparedness for emergency and disaster relief. |

| Czech Republic (high) |

HEALTH 2020 – National Strategy for Health Protection and Promotion and Disease Prevention (2014; primary)*48 | 2014–2020 | No | Prevention +management |

Stabilise the system of disease prevention, health protection and promotion and to initiate efficient mechanisms to improve health of the population, sustainable in the long term. |

| Long-term programme of improving the health status of the population of the Czech Republic – Health for All in the 21st Century (2002; primary)**49 | n.s. | No | Prevention +management |

Protect human health and development over the life course and reduce the incidence of diseases and injuries and limit suffering. | |

| Denmark (high) |

Recommendations for preventative services for citizens with chronic diseases (2016; primary)50 | n.s. | No | Prevention +management |

Guide how services in the municipalities can implement important preventative measures in the best possible way, so citizens all over the country will receive high-quality services for prevention of chronic diseases. |

| Care pathways for chronic diseases – the generic model (2012; primary)51 | n.s. | No | Prevention +management |

To present a generic model of care to use as a basis for creating other (disease-specific) care pathways. | |

| Estonia (high) |

National Health Plan 2009–2020 (2012; primary)*52 | 2009–2020 | No | Management | A longer health-adjusted life expectancy by decreasing premature mortality and illnesses. |

| France (high) |

Laws Official Journal of the French Republic of January 27th, 2016: Law no 2016–41, January 26th, 2016 of the Modernisation of Our Health System (1). Keynote Title: Mobilising Health System Members Around a Shared Strategy (2016; primary)53 | n.s. | No | Prevention +management |

To mobilise health system members around a shared (health) strategy. |

| National Health Strategy: Roadmap (2013; primary)54 | n.s. | No | Prevention +management |

To address growing social and geographical inequalities which limit access to healthcare in France. | |

| Germany (high) |

IN FORM: Germany’s initiative for healthy nutrition (diet) and more physical activity. National action plan for prevention of malnutrition, lack of physical activity overweight and associated diseases (2014; primary)55 | n.s. | Yes | Prevention +management |

To improve the nutrition and physical activity behaviour in Germany in a sustainable way, such that: adults live healthier, children grow up healthier and benefit from a higher quality of life and an increased performance in their education, profession and private life; and diseases that are caused by an unhealthy lifestyle will decline. |

| Hungary (high) |

‘Healthy Hungary 2014–2020’—Health Sector Strategy (2015; primary)56 | 2014–2020 | No | Prevention +management |

To improve the health of Hungarians through different interventions (prevention, rehabilitation) and through further improvement to the whole healthcare system across sectors with a focus on responsible and cooperative citizen participation. |

| Iceland (high) |

Public health policy and actions to encourage a healthier society—with emphasis on children and adolescents under 18 years of age (2016; primary)57 | 2016–2018 | No | Prevention +management |

Iceland will be one of the healthiest nations worldwide by 2030. |

| Ireland (high) |

Tackling Chronic Disease: A Policy Framework for the Management of Chronic Diseases (2008; primary)*58 | n.s. | No | Prevention +management |

To promote and to improve the health of the population and reduce the risk factors that contribute to the development of chronic diseases; and to promote structured and integrated care in the appropriate setting that improves outcomes and quality of life for patients with chronic conditions. |

| Healthy Ireland: A framework for improved health and well-being 2013–2025 (2013; primary)*59 | 2013–2025 | No | Prevention +management |

A healthy Ireland, where everyone can enjoy physical and mental health and well-being to their full potential, where well-being is valued and supported at every level of society and is everyone’s responsibility. | |

| Italy (high) |

National Prevention Plan 2014–2018 (2014; primary)60 | 2014–2018 | Yes | Prevention | To establish the crucial role of health promotion and prevention as factors of social development and welfare sustainability, in light of demographic changes; adopt a public health approach that will guarantee equality and contrast disparities; express the cultural vision in public health values, objectives and methods; base health prevention, promotion and care interventions on best effective evidence, implemented with equality and planned to reduce disparities; accept and manage the challenge of cost-effective interventions, innovation and governance; and develop competence in professionals, people and individuals aiming at an appropriate and responsible use of available resources. |

| National Chronicity Plan (2016; primary)61 | n.s. | Yes | Prevention +management |

To contribute to the improvement of health protection for chronically ill people, reducing the burden on the individual, on his/her family and on the social context, improving the quality of life, making health services more effective and efficient in terms of prevention and assistance and assuring a higher harmonisation and equity for citizens’ access. This will be achieved by identifying a common strategy aiming at promoting a unified approach to interventions centred on the individual and oriented towards a better service organisation and responsibilities of all the service-providing actors. | |

| Gaining Health: Making healthy choices easy (2008; primary)62 | n.s. | No | Prevention | To make healthy life choices easier for Italians and to promote information campaigns aimed at changing unhelpful behaviours, which contribute to causing non-communicable diseases of a major epidemiological significance. | |

| Japan (high) |

Health Japan 21 (the second term) (2012; primary)63 | 2013–2022 | No | Prevention | To improve lifestyles and the social environment; to enable all citizens from infancy to older adulthood to have hope and meaning for living; to achieve a vibrant society with healthy and spiritually rich lives according to life stages; and to improve sustainability of the social security system. |

| Republic of Korea (high) |

National Health Plan 2020 in Korea (2011; secondary)*64 | 2011–2020 | No | Prevention +management |

To create a healthy world all people can enjoy together through an extension of healthy life expectancy, an improvement in health equity and monitoring of health trends. |

| The Third National Health Promotion Plan (2011–2020) (2011; primary)40 | 2011–2020 | Yes | Prevention +management |

To establish national policies aimed at enhancing the health of individuals and groups through health education, disease prevention, nutrition improvement and the practice of healthy lifestyles. | |

| Latvia (high) |

Public Health Guidelines 2014–2020 (2014; primary)**65 | 2014–2020 | Yes | Prevention +management |

To increase the lived healthy life years of the Latvian population and prevent premature death through maintaining, improving and restoring health. |

| Lithuania (high) |

Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania Resolution No XII-964 of Approval of the Lithuanian Health Strategy 2014–2025 (2014; primary)*66 | 2014–2025 | No | Prevention | The attainment of improved health of the Lithuanian population by 2025 as well as longer life and reduced health inequities. |

| The 2014–2020 National Programme Progress Horizontal Priority ’Health for All’ Interinstitutional Operations Plan (2014; primary)**67 | 2014–2020 | No | Prevention +management |

To coordinate measures to enhance public health outcomes and implement the principle of health in all policies to achieve closer interagency cooperation on public health issues. | |

| The National Public Healthcare Development Programme for 2016–2023 (2015; primary)*68 | 2016–2023 | No | Prevention +management |

To set goals, tasks, assessment criteria and anticipated values of national public healthcare strategies and to ensure implementation of public healthcare goals and tasks set in the Lithuanian Health Programme for 2014–2025. | |

| Mexico (upper middle) |

National Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Overweight, Obesity and Diabetes (2013; primary)69 | n.s. | Yes | Prevention +management |

To improve the well-being of the population and contribute to the sustainability of national development by decreasing the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Mexicans, in order to impact the epidemic of non-communicable diseases, particularly type 2 diabetes, through public health interventions, a comprehensive model of medical attention and intersectoral political action. |

| The Netherlands (high) |

All about health (2013; primary)*70 | 2014–2016 | No | Prevention | To promote individual health and prevent chronic illness by means of an integrated approach within the settings in which people live, work and learn; give prevention a prominent place within healthcare; and maintain the quality of health protection, responding promptly to any new threats. |

| Norway (high) |

NCD-Strategy 2013–2017. For the prevention, diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation of four non-communicable diseases: cardiovascular disease, diabetes, COPD and cancer (2013; primary)*71 | 2013–2017 | Yes | Prevention +management |

To reduce premature death from cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic lung disease and cancer by 25% by 2025. |

| Poland (high) |

The National Health Programme for the years 2016–2020, Council of Ministers’ Decree (2016; primary)**72 | 2016–2020 | Yes | Prevention +management |

To extend healthy life, improve health and related quality of life of the population, and reduce social inequalities in health. |

| Portugal (high) |

National Health Plan 2020 Review and Outreach (2015; primary)**38 | 2015–2020 | Yes | Prevention +management |

To maximise the health gains by integrating sustained efforts in all sectors of society, and the use of strategies based on citizenship, equity and access in quality and in healthy policies. |

| Slovakia (high) |

Updated National Health Promotion Programme in the Slovak Republic (2014; primary)**73 | 2014–2030 | No | Prevention | To achieve a long-term improvement in the health of the Slovak population, extending life expectancy and quality of life, eliminating the incidence of health disorders that reduce quality of life and threaten premature human death. The policy is primarily aimed at influencing the determinants of health, reducing population-based risk factors and increasing involvement of various sectors of society. |

| Slovenia (high) |

Resolution on the National Healthcare Plan 2016–2025 (2016; primary)*74 | 2016–2025 | No | Prevention +management |

To promote health and prevent diseases; optimise healthcare; enhance the performance of the healthcare system; and achieve equity, solidarity and sustainability in financing of healthcare. |

| Spain (high) |

Strategy for Addressing Chronicity in the National Health System (2012; primary)75 | n.s. | No | Prevention +management |

To decrease the prevalence of health conditions and chronic limitations of activity, reduce premature mortality of people who already have any of these conditions, prevent deterioration of functional capacity and complications associated with each process, and improve the quality of life of people and their caregivers. |

| Sweden (high) |

A person-centred public health policy (2012; primary)76 | n.s. | No | Prevention | To present a person-centred public health policy. |

| A cohesive strategy for alcohol, narcotic drugs, doping and tobacco (ANDT) policy (2011; primary)*77 | 2011–2025 | No | Prevention +management |

A society free from illegal drugs and doping, with reduced alcohol-related medical and social harm, and reduced tobacco use. | |

| Switzerland (high) |

Action plan for the National Strategy on the Prevention of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCD-Strategy) 2017–2024 (2016; primary)78 | 2017–2024 | Yes | Prevention +management |

To improve the coordination between actors and agencies and to increase the efficiency in prevention and health promotion. |

| National strategy for the prevention of non-communicable diseases (NCD-Strategy) 2017–2024 (2016; primary)79 | 2017–2024 | Yes | Prevention +management |

More people stay healthy or have, despite chronic illness, a high quality of life. Less people fall ill with avoidable, non-communicable diseases or die prematurely. Independent of their socioeconomic status, people are enabled to have a healthy lifestyle in a conducive healthy environment. | |

| Turkey (upper middle) |

Multisectoral Action Plan of Turkey for Non-communicable Diseases 2017–2025 (2017; primary)*39 | 2017–2025 | Yes | Prevention +management |

To raise the health and well-being of the Turkish population through reducing preventable deaths and the disability burden attributable to NCDs and thus enabling citizens to maintain the highest attainable health status at all ages. |

| United Kingdom (high) | Living Well for Longer: A call for action to reduce avoidable premature mortality (2013; primary)*80 | n.s. | No | Prevention +management |

To challenge and inspire the health and care system, in its widest sense, to take action to reduce the numbers of people dying prematurely, defined as premature deaths due to cancer, heart disease, stroke, respiratory disease and liver disease under the age of 75 years. |

| United States of America (high) | National Prevention Council Action Plan: Implementing the National Prevention Strategy (2012; primary)*81 | n.s. The development of a pragmatic | No | Prevention | To identify National Prevention Council shared departmental commitments and unique department actions to further each of the strategic directions and priorities of the National Prevention Strategy. |

*Source document published in English.

**Source document translated to English.

†Classification: documents classified as primary or secondary. Primary documents are full or stand-alone national or jurisdictional policy or strategy documents. Primary documents may be brief, but should be interpretable as a stand-alone document. Secondary documents accompany primary documents (eg, infographics, summary pages, excerpts from primary documents) and do not represent the full policy or document.

‡Refers to the WHO Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases 2013–2020.21

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease;NCD, non-communicable disease; n.s., not stated.

The purpose/aims of included policies (table 1) were summarised with three overarching themes, supported by a range of subthemes and linked to 22 first-order codes (online supplementary file 3). These are described in the meta-synthesis below.

bmjgh-2019-001806supp003.pdf (67.7KB, pdf)

System strengthening

Policies outlined a system-strengthening focus that included aspects of governance (such as the creation of disease-specific models of care and public policy), financing to achieve health service sustainability and building workforce capacity. A number of policies also included a focus on building emergency and disaster response capacity. Expanding the reach of health services through improved coverage and access to minimise inequality due to socioeconomic or geographical factors, were also identified. Some policies identified population health monitoring as a focus.

Service delivery

Policies cited improvement in health service delivery as a key focus through effective, efficient and comprehensive management approaches for NCDs, including addressing multimorbidity. Quality in service delivery and support for integrated care, active self-management and innovation in service delivery were identified as common aims.

Population health

Policies aimed to target risk factors for poor health, to support screening and to promote healthy lifestyles across the life course as a means to improve physical and mental health and functional ability. Specific policy foci included a reduction in use and harms related to substance abuse, decreasing the incidence and prevalence of overweight and obesity, and improving population-level physical activity. Policies aimed to reduce the impact of NCDs by reducing incidence of disease (NCDs and communicable diseases) and premature mortality and injury, thereby improving the quality of life of the population. Environmental factors influencing health were also cited, including food and workplace safety.

Integration of musculoskeletal health, persistent pain and mobility/functional ability in NCD health policies

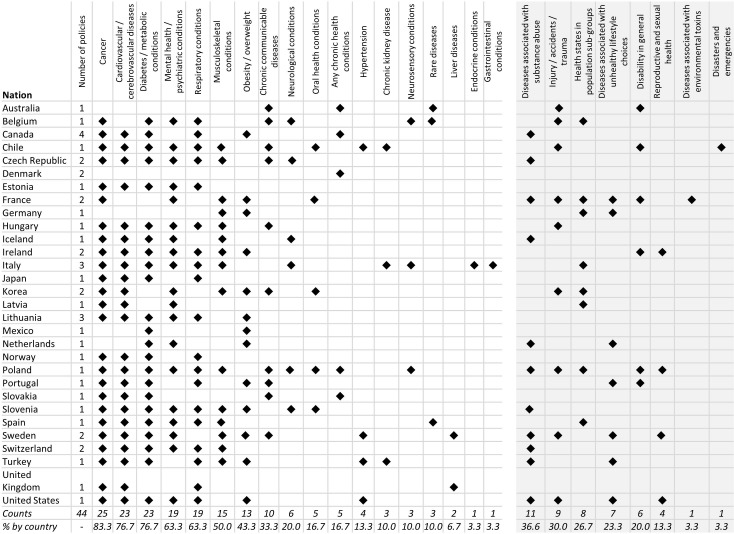

Figure 1 illustrates the conditions (health states) explicitly stated as being covered by the policies across nations, while table 2 summarises this detail by policy. Whereas the polices of most countries covered cancer (83.3%), cardiovascular disease (76.6%), diabetes/endocrine disorders (76.6%), respiratory conditions (63.3%) and mental health conditions (63.3%), only half the countries included musculoskeletal health and pain (50.0%) as conditions covered within the policies. Five (16.7%) countries had policies that included any chronic health conditions. Among the 41 (93.2%) policies of 30 countries that included a background commentary, 23 (56.1%) mentioned musculoskeletal health, pain or mobility/functional ability in some way. Within the specific context of prevention and/or management of NCDs, 23 (52.3%) policies of 19 (63.3%) countries referred explicitly to musculoskeletal health, pain or mobility/functional ability, including: 20 (45.4%) to musculoskeletal health, 5 (11.4%) to pain and 11 (25.0%) to mobility/functional ability. The context in which musculoskeletal health was mentioned included:

Figure 1.

Frequency map of diseases/health conditions (left panel) and health states (right panel) explicitly cited as within the scope or coverage of the included policies by nation. Musculoskeletal conditions encompass any condition of the musculoskeletal system or persistent non-cancer pain. Neurological conditions include any neurological or neurodegenerative condition.

Table 2.

Health conditions/priority areas included within scope; the extent of integration of musculoskeletal health (MSK), mobility (Mob) or functional ability (FA) and persistent non-cancer pain; and internal validity scores across included policies

| Nation | Policy title (year of publication) | Health conditions/priority areas included within stated scope | Policy explicitly includes MSK health, mobility/ functional ability or persistent pain in the context of NCD management | Aims/objectives and strategies/actions relevant to prevention or management of MSK, Mob/FA or pain (all, some, none, n/a) | Internal validity sum score (range: 0–14) | ||

| MSK | Mob / FA | Pain | |||||

| Australia | National Strategic Framework for Chronic Conditions (2017; primary)45 | All chronic and complex health conditions across the spectrum of illness, including mental illness, trauma, disability and genetic disorders, including communicable diseases and NCDs. | No | No | No | All | 11 |

| Belgium | Chronic Disease Plan. Integrated Health Services for Better Health (2015; primary)46 | NCDs (diabetes, cancer, asthma), chronic communicable disease (HIV-AIDS), mental health (psychoses), certain anatomical/functional conditions (blindness, multiple sclerosis), rare diseases, following accidental injury (amputation, paralysis), complex multimorbidities in the stages of high dependency or palliative care. | No | No | No | All | 11 |

| Canada | Integrated Strategy on Healthy Living and Chronic Disease (2005; secondary)44 | All chronic diseases and explicitly states inclusion of diabetes, cancer, respiratory diseases and cardiovascular disease. | No | No | No | All | 0 |

| Canada’s Tobacco Strategy (2018; secondary)41 | Chronic diseases associated with tobacco use. | No | No | No | None | 3 | |

| Curbing Childhood Obesity: A Federal, Provincial and Territorial Framework for Action to Promote Healthy Weights (2010; primary)42 | Obesity and overweight. | No | No | No | All | 3 | |

| Let’s get moving: A common vision for increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary living in Canada (2018; primary)43 | n.s. | No | No | No | All | 10 | |

| Chile | National Health Strategy to Complete the Health Objectives of the Decade (2011; primary)47 | Communicable diseases—HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, acute respiratory disorders. NCDs—explicitly covers cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, cancer, chronic respiratory disorders, mental health disorders, disability, oral health conditions and musculoskeletal conditions. Injury—traffic accidents, workplace injury and family violence. Emergencies and disasters. |

Yes | Yes | Yes | Some | 13 |

| Czech Republic | HEALTH 2020 National Strategy for Health Protection and Promotion and Disease Prevention (2014; primary)48 | Serious NCDs such as type 2 diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, mental disorders and musculoskeletal diseases, among others. | Yes | No | No | Some | 10 |

| Long-term programme of improving the health status of the population of the Czech Republic – Health for All in the 21st Century (2002; primary)**49 | New cancers, metabolic diseases especially diabetes, musculoskeletal diseases, respiratory diseases, cardiovascular disease, nervous and mental diseases, psychosomatic consequences of drug use, certain infections (AIDS). | Yes | No | No | Some | 7 | |

| Denmark | Recommendations for preventative services for citizens with chronic diseases (2016; primary)50 | All chronic conditions. | Yes | Yes | Yes | All | 6 |

| Care pathways for chronic diseases – the generic model (2012; primary)51 | All chronic conditions. | Yes | Yes | No | All | 1 | |

| Estonia | National Health Plan 2009–2020 (2012; primary)*52 | Cancer, cardiovascular diseases, asthma, diabetes, mental health conditions. | No | No | No | Some | 10 |

| France | Laws Official Journal of the French Republic of January 27th, 2016: Law no 2016–41 January 26th, 2016 of the Modernisation of Our Health System (1). Keynote Title: Mobilising Health System Members Around a Shared Strategy (2016; primary)53 | NCDs including: mental disorders, cancer, pain; diseases related to poor nutrition; diseases related to lifestyle conditions that are susceptible to change; diseases related to tobacco use; diseases related to illicit drug use (narcotics, psychoactive drugs); diseases related to poor oral health; conditions related to environmental conditions (eg, air pollution); conditions related to exposure to harmful chemicals in consumer products (lead, asbestos, bisphenol A); injury; disability. | No | No | Yes | Some | 5 |

| National Health Strategy: Roadmap (2013; primary)54 | NCDs related to unfavourable health behaviours (tobacco consumption, excessive alcohol consumption, malnutrition, sedentary behaviours); individuals living with a disability or age-related loss of autonomy; other public health priority areas including youth health, obesity, mental health, cancer and age-related illness. | No | No | No | All | 10 | |

| Germany | IN FORM: Germany’s initiative for healthy nutrition (diet) and more physical activity. National action plan for prevention of malnutrition, lack of physical activity overweight and associated diseases (2014; primary)55 | Overweight and obesity and their sequelae; diseases associated with inadequate physical activity; malnutrition and eating disorders (eg, anorexia, bulimia); postural deformities in children and teenagers; work-related musculoskeletal disorders. | No | No | No | Some | 7 |

| Hungary | “Healthy Hungary 2014–2020”—Health Sector Strategy (2015; primary)56 | Cardiovascular conditions; diabetes; chronic respiratory disease; musculoskeletal diseases; cancer; mental health; accident/injury; communicable diseases. | Yes | No | No | Some | 8 |

| Iceland | Public health policy and actions to encourage a healthier society—with emphasis on children and adolescents under 18 years of age (2016; primary)57 | Heart disease; diabetes; cancer; musculoskeletal conditions; migraine; drug abuse and mental health conditions. | Yes | No | No | Some | 11 |

| Ireland | Tackling Chronic Disease: A Policy Framework for the Management of Chronic Diseases (2008; primary)*58 | Cardiovascular disease; diabetes; cancer; musculoskeletal conditions and osteoporosis; mental disorders; asthma and chronic bronchitis. | Yes | No | No | Some | 5 |

| Healthy Ireland: A framework for improved health and well-being 2013–2025 (2013; primary)*59 | Overweight and obesity; mental health; sexual health; disability. | No | No | No | None | 9 | |

| Italy | National Prevention Plan 2014–2018 (2014; primary)60 | NCDs including cardiovascular diseases, cancer, respiratory diseases, diabetes, mental health conditions; neurosensory conditions, including hearing impairment and deafness, visual impairment and blindness; occupational health, including musculoskeletal conditions. | No | No | No | None | 4 |

| National Chronicity Plan (2016; primary)61 | Chronic kidney disease; rheumatoid arthritis and chronic arthritis in developmental age (juvenile arthritis); ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease; chronic heart failure; Parkinson's disease and Parkinsonism; COPD; chronic respiratory failure; asthma; chronic endocrine diseases. | Yes | Yes | No | Some | 6 | |

| Gaining Health: Making healthy choices easier (2008; primary)(62) | Cardiovascular diseases; cancer; diabetes; chronic respiratory diseases; mental health conditions; musculoskeletal conditions. | Yes | No | No | n.s | 0 | |

| Japan | Health Japan 21 (the second term) (2012; primary)63 | Cancer; cardiovascular diseases; diabetes and COPD. | No | No | No | Some | 9 |

| Republic of Korea | National Health Plan 2020 in Korea (2011; secondary)64 | Cancer; arthritis; cardiocerebrovascular disease; obesity; mental health conditions; oral health; infectious diseases (tuberculosis, AIDS); injury prevention; health of population subgroups (maternal, infant, elderly, worker’s health, military health). | Yes | Yes | No | n.s. | 6 |

| The Third National Health Promotion Plan (2011–2020) (2011; primary)40 | Cardiovascular disease; arthritis; obesity; diabetes; cancer; mental health; oral health; communicable diseases. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Some | 12 | |

| Latvia | Public Health Guidelines 2014 – 2020 (2014; primary)**65 | Cardiovascular disease; cancer; paediatric/neonatal health; mental health. | No | No | No | Some | 10 |

| Lithuania | Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania Resolution No XII-964 of Approval of the Lithuanian Health Strategy 2014–2025 (2014; primary)*66 | Cardiovascular disease; cancer; diabetes; chronic respiratory diseases and mental health disorders. | No | No | No | Some | 5 |

| The 2014–2020 National Programme Progress Horizontal Priority ‘Health for All’ Interinstitutional Operations Plan (2014; primary)**67 | Cardiovascular disease; cerebrovascular conditions; cancer; mental health conditions. | No | No | No | Some | 7 | |

| The National Public Healthcare Development Programme for 2016–2023 (2015; primary)*68 | Mental health conditions; obesity; diabetes; cancer and cardiovascular disease. | Yes | No | No | Some | 10 | |

| Mexico | National strategy for the prevention and control of overweight, obesity and diabetes (2013; primary)69 | Overweight; obesity; diabetes. | No | No | No | Some | 12 |

| The Netherlands | All about health (2013; primary)70 | Health conditions related to: smoking, overweight/obesity, excessive alcohol consumption, and physical inactivity; depression; diabetes. | No | No | No | Some | 10 |

| Norway | NCD-Strategy 2013–2017. For the prevention, diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation of four non-communicable diseases: cardiovascular disease, diabetes, COPD and cancer (2013; primary)71 | Cardiovascular disease; diabetes; COPD and cancer. | No | No | No | All | 4 |

| Poland | The National Health Programme for the years 2016–2020, Council of Ministers’ Decree (2016; primary)**72 | NCDs in general, with specific reference to acute myocardial infarction; stroke; cancer; asthma; COPD; diabetes; depression and mental distress; dental caries; dementia; musculoskeletal pain; infertility; substance abuse conditions; specific communicable diseases (HCV, HBV, HIV, rubella, measles, polio); suicide; functional limitations on physical and sensory organs; and women’s and children’s health (pregnancy/labour/perinatal maternal health, child health problems diagnosed in utero, developmental problems of newborns, low birth weight, fertility, infant and maternal mortality). | Yes | Yes | No | Some | 8 |

| Portugal | National Health Plan 20208 Review and Outreach (2015; primary)**38 | Cardiovascular disease; cancer; diabetes; obesity; chronic respiratory diseases; disability; nutrition-related diseases, HIV/AIDs. | No | Yes | No | Some | 10 |

| Slovakia | Updated National Health Promotion Program in the Slovak Republic (2014; primary)**73 | All health conditions (communicable and non-communicable), with specific foci including cardiovascular diseases; diabetes and selected cancers (cervical, breast, colon/rectal). | No | No | No | Some | 6 |

| Slovenia | Resolution on National Healthcare Plan 2016–2025 (2016; primary)*74 | Cardiovascular disease; cancer; obesity; diabetes; chronic respiratory diseases; neurodegenerative diseases; autism; epilepsy; musculoskeletal diseases; diseases of the teeth and oral cavity; mental illness; conditions related to substance abuse (alcohol, tobacco smoking). | Yes | Yes | No | Some | 12 |

| Spain | Strategy for Addressing Chronicity in the National Health System (2012; primary)75 | Cancer; ischaemic heart disease; stroke; diabetes; mental health; COPD; rare diseases; pain; palliative care. | No | Yes | Yes | All | 8 |

| Sweden | A person-centred public health policy (2012; primary)76 | NCDs related to lifestyle with specific reference to: diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, liver damage, hypertension, psychiatric diseases, stroke, musculoskeletal conditions and overweight; accidents and injury; communicable diseases, including sexually transmitted diseases. | Yes | Yes | No | Some | 4 |

| A cohesive strategy for alcohol, narcotic drugs, doping and tobacco (ANDT) policy (2011; primary)*77 | Any conditions associated with substance abuse. | No | No | No | Some | 4 | |

| Switzerland | Action plan for the National Strategy on the Prevention of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCD-Strategy) 2017–2024 (2016; primary)78 | Respiratory diseases; cancer; cardiovascular diseases; diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders; conditions related to substance abuse; mental health disorders. | Yes | No | No | Some | 13 |

| National strategy for the prevention of non-communicable diseases (NCD-Strategy) 2017–2024 (2016; primary)79 | Respiratory diseases; cardiovascular disease; cancer; diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders. | Yes | No | No | All | 13 | |

| Turkey | Multisectoral Action Plan of Turkey for Non-communicable Diseases 2017–2025 (2017; primary)*39 | Cardiovascular diseases; malignant neoplasms; respiratory diseases; diabetes; cancer (specifically breast and cervical cancers); chronic airway diseases; COPD; asthma; disease related to lifestyle choices (tobacco consumption, secondhand smoke, alcohol consumption, unhealthy diet (high salt consumption), raised blood cholesterol, and insufficient physical activity); obesity; hypertension; chronic kidney disease; musculoskeletal system diseases. | Yes | No | No | Some | 13 |

| United Kingdom | Living Well for Longer: a Call to Action to Reduce Avoidable Premature mortality (2013; primary)*80 | Cancer; circulatory disease (heart disease, stroke); respiratory and liver disease. | No | No | No | All | 4 |

| United States of America | National Prevention Council Action Plan: Implementing the National Prevention Strategy (2012; primary)81 | Diseases related to lifestyle choices (tobacco, substance abuse, nutrition, physical inactivity; for example, obesity, heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, certain cancers, respiratory infections, asthma, depression); injury/accidents (including violence); reproductive and sexual health; mental health. | Yes | No | No | Some | 5 |

*Source document published in English.

**Source document translated to English.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FA, functional ability or functional impairment; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; Mob, mobility;MSK, musculoskeletal;NCD, non-communicable disease; n.s., not stated; Pain, persistent non-cancer pain.

Within prevention and management strategies for NCDs (n=12 policies);

A leading cause of disability in the country (n=8 policies);

A determinant of healthy ageing (n=4 policies);

A priority condition for care pathways (n=2 policies);

Arthritis as a priority condition (n=3 policies);

Conditions amenable to lifestyle/behaviour change (n=3 policies);

An indicator for population health monitoring (n=1 policy).

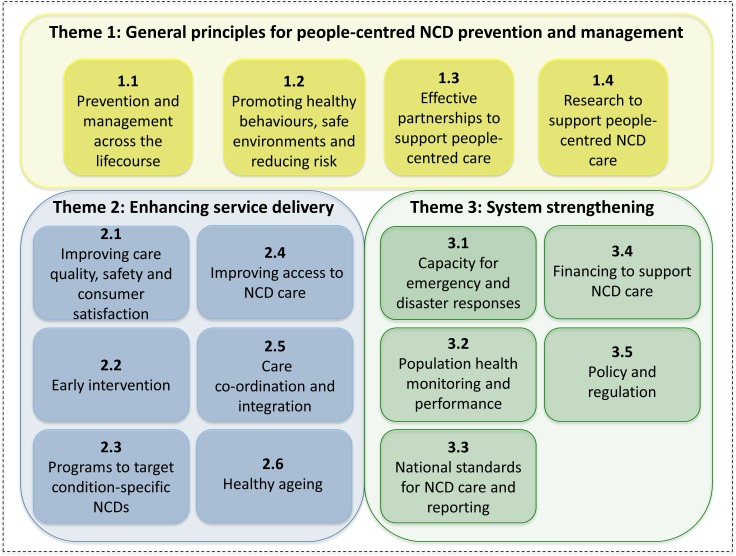

Strategies outlined within and across policies, including relevance to musculoskeletal health, pain and mobility

General strategies to address the stated policy aims were outlined in 42 (95.5%) policies. From these, all strategies were relevant to prevention/management of musculoskeletal health, pain and mobility/functional ability in 12 (28.6%) policies, some were relevant in 27 (64.3%) policies and none were relevant in 3 (7.1%) policies. Thirty first-order codes were derived to summarise these general strategies. An additional 12 first-order codes were derived to summarise strategies specific to the prevention or management of musculoskeletal conditions, pain or mobility/functional ability. This resulted in a net 42 first-order codes, and these were subsequently aggregated into three overarching themes with supporting subthemes (figure 2; table 3). Twenty-eight (93.3%) of the 30 first-order codes in table 3 describing general policy strategies were relevant to the prevention/management of musculoskeletal health conditions, persistent pain or loss of functional ability/mobility (range: 2.1%–71.4% of policies), with the exception of 1.2.1 and 3.1.1. The frequency of policies with strategies specific to musculoskeletal health (ie, general strategies linked to musculoskeletal health based on the initial 30 first-order codes, or strategies cited in policies as explicitly related to musculoskeletal health based on the additional 12 first-order codes), is also included in table 3; range: 2.6%–55.3% of policies. A narrative meta-synthesis of the themes aligned to general and specific strategies is provided below.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the themes and subthemes describing the strategies outlined in the included policies for integrated management of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). The themes align with the WHO Framework on Integrated People-Centred Health Services (IPCHS).85. Theme 1 aligns with IPCHS strategy 1 (‘engaging and empowering people and communities’); theme 2 aligns with IPCHS strategies 3 and 4 (‘reorienting the model of care’ and ‘coordinating services within and across sectors’, respectively); theme 3 aligns with IPCHS strategy 5 (‘creating an enabling environment’).

Table 3.

Summary of overarching themes, supported by subthemes and first-order codes to describe the scope and content of the strategies outlined in the included policies. Frequencies of general strategies and frequencies of specific strategies relevant to musculoskeletal (MSK) health, pain or mobility/functional ability, by policy, are included to provide a measure of prominence for first-order codes. Frequencies are colour coded for ease of interpretation (red <25%; amber ≥25% to <50%; green ≥50%).

| Subthemes | First-order codes describing strategies contained in policies | Frequency of policies with general strategies; n (%) | Frequency of policies with strategies relevant to MSK, pain or mobility/functional ability care; n (%) |

| Theme 1: General principles for people-centred NCD care | |||

| 1.1 NCD prevention and management across the life course | 1.1.1 NCD prevention/management should be based on a care continuum across the life course from prevention (including maternal and child healthcare) through to rehabilitation and palliative care that is tailored to the individual's needs and that considers physical health, mental well-being and injury protection. A focus on vulnerable groups should be prioritised. | 16 (38.1)* | 8 (21.1) |

| 1.1.2 NCD prevention/management should include initiatives that address social and financial consequences of, or risk factors for, NCDs and that promote physical and social function. | 13 (31.0)* | 8 (21.1) | |

| 1.1.3 NCD management should adopt a people-centred model in service delivery. | 1 (2.4)* | 2 (5.3) | |

| 1.2 Promoting healthy behaviours, safe environments and reducing risk | 1.2.1 NCD prevention/management should be based on promoting a healthy and safe environment to minimise risk factors for NCDs including food safety, exposure to chemicals, air and noise pollution, and climate change. This approach should extend to education and work environments. | 15 (35.7) | 3 (7.9) |

| 1.2.2 NCD prevention/management should support the development and implementation of multifaceted interventions to increase the volume of physical activity (PA) and reduce sedentary behaviour at the population level targeting all ages (eg, population awareness campaigns; supportive environments and transport options; work and school-based PA; leadership in PA initiatives; upskilling teachers in PA) with indicators to monitor performance. | 14 (33.3)* | 16 (42.1) | |

| 1.2.3 NCD prevention/management should be based on promoting healthy behaviours/lifestyles to minimise risk factors for NCDs (primary and secondary prevention) with a strong focus on obesity management. Foci should include healthy lifestyle (nutrition focusing on a reduction of sugar, salt and saturated fats; PA; safe use of alcohol/tobacco; minimising substance abuse especially in youth; mental health strategies; and oral hygiene). This approach should extend to education and work environments, with particular attention paid to supporting healthy lifestyle environments for children in schools. | 30 (71.4)* | 22 (57.9) | |

| 1.2.4 NCD prevention/management should include public health education that is accessible and disseminated across various settings (eg, work, education/school, kindergarten) and is tailored to target groups, with the outcome being a change in health beliefs and empowering positive health behaviours (improved health literacy) and improved capacity for self-management. In some settings, mass media is recommended. | 25 (59.5)* | 17 (44.7) | |

| 1.2.5 †NCD prevention/management should support the development and implementation of policies and/or programmes that target reducing the potentially negative effects of alcohol, narcotics, doping substances and tobacco (ANDT) on the MSK system, on the mental health system and that reduce the chances of injury to the MSK system. | – | 2 (5.3) | |

| 1.3 Effective partnerships to support people-centred care | 1.3.1 NCD prevention/management efforts (inclusive of service delivery, service design and policy formulation) should be approached with effective partnerships across the sector (eg, government, civil society, volunteers, health services, industry) and with consumers and their families, including indigenous communities. | 21 (50.0)* | 11 (28.9) |

| 1.4 Research to support people-centred NCD care | 1.4.1 NCD prevention/management should support research that is accessible to decision makers, that addresses societal need in NCD prevention/management, that considers emerging technologies/technology innovations, that examines the value of complementary and alternative medicines, and is system-relevant. | 12 (28.6)* | 7 (18.4) |

| Theme 2: Service delivery | |||

| 2.1 Improving care quality, safety and consumer satisfaction | 2.1.1 Deliver interventions or services that are effective and safe (high-value) and that improve care quality and consumer satisfaction. | 15 (35.7)* | 7 (18.4) |

| 2.1.2 Prevention initiatives (eg, programmes, policies) should be underpinned by quality criteria for NCD prevention, including evaluation of effectiveness. | 4 (9.5)* | 4 (10.5) | |

| 2.2 Early intervention | 2.2.1 NCD prevention should include timely interventions to identify and manage risk factors, enable early diagnosis (eg, health checks, screening, education campaigns) and enable risk classification/stratification. | 20 (47.6)* | 14 (36.8) |

| 2.2.2 †National health assessments or ‘health checks’ should include assessment of disability. | – | 1 (2.6) | |

| 2.2.3 †Implement strategies and policy for injury prevention at work, for leisure and sport and that monitor injury prevalence. | – | 3 (7.9) | |

| 2.3 Programmes targeting condition-specific NCDs | 2.3.1 NCD management of major conditions should include programmes that are evaluated and supported by disease-specific clinical guidelines and established criteria for diagnosis and stratification. Mechanisms to update programmes based on new evidence should be included. | 8 (19.0)* | 3 (7.9) |

| 2.3.2 NCDs management should include disease-specific and technology-enabled models of care, that address a specific population or condition/disease group and contain evidence-based components of care, implementation strategies, and mechanisms for monitoring and quality improvement. | 4 (9.5)* | 2 (5.3) | |

| 2.3.3 †NCD management should include support strategies for obesity reduction/prevention strategies, in addition to general nutrition and PA strategies. | – | 1 (2.6) | |

| 2.3.4 †Support delivery of mental healthcare through targeted health promotion, through accessible services (inclusive of mind-body therapies) and through provider training in mental healthcare. | – | 5 (13.2) | |

| 2.3.5 †Support specific system and service strategies for arthritis (identification of disease, supporting adherence to pharmacological and non-pharmacological care, integrated management between health services and clinicians, development of models of service delivery and models of care). | – | 2 (5.3) | |

| 2.4 Improving access to NCD care | 2.4.1 Support NCD management by harnessing digital technologies (eg, eHealth, telehealth, electronic medical records) to enable information/service access and exchange for consumers and health professionals to support self-management, system navigation and care delivery. | 10 (23.8)* | 6 (15.8) |

| 2.4.2 Support accessible NCD care services (geographically accessible, appropriate infrastructure, ICT support) irrespective of age, gender, residence and socioeconomic status, and ensure that services are culturally acceptable. | 17 (40.5)* | 12 (31.6) | |

| 2.4.3 NCD prevention and management needs to be supported by population access to essential medicines and essential laboratory medicine. | 3 (7.1)* | 4 (10.5) | |

| 2.5 Care coordination and integration | 2.5.1 Create community-based, multidisciplinary healthcare teams responsive to local needs, supported by a referral network for providers. | 5 (11.9)* | 4 (10.5) |

| 2.5.2 Build and monitor capacity/competencies in the workforce (particularly in primary care) to deliver high-value NCD care, including a focus on ageing, mental health, obesity management, PA and competencies in technology use. | 17 (40.5)* | 10 (26.3) | |

| 2.5.3 Support care coordination between the workforce and support coordination and integration between services, regions and existing programme (eg, with ICT infrastructure, referral networks). | 20 (47.6)* | 11 (28.9) | |

| 2.5.4 †Ensure that health facilities have rehabilitation professionals working in multidisciplinary teams. | – | 1 (2.6) | |

| 2.5.5 †Ensure that citizens who have NCDs have comprehensive health plans developed, inclusive of supports for return to work. | – | 3 (7.9) | |

| 2.5.6 †Support the provision of community-based rehabilitation services, especially in areas where care disparities exist. | – | 2 (5.3) | |

| 2.6 Supporting healthy ageing | 2.6.1 In the context of supporting older people living with NCDs, implement specific strategies and indicators to support healthy ageing (health promotion; health checks; interventions to address functional impairments; develop models of care for older people that include geriatric care and long-term care systems). | 8 (19.0)* | 5 (13.2) |

| Theme 3: System strengthening | |||

| 3.1 Capacity for emergency response to disasters and epidemics | 3.1.1 Strengthen emergency response capacity to better manage disasters and epidemics. | 5 (11.9)* | 1 (2.6) |

| 3.2 Population health monitoring and performance | 3.2.1 To inform NCD prevention and management initiatives, population health monitoring/surveillance is needed through electronic health information systems, that should include health and injury outcomes and the social determinants of health. | 14 (33.3)* | 6 (15.8) |

| 3.2.2 Performance targets for NCD management/prevention should be based on: reduction in risk factors for NCDs; prevention of premature mortality; minimising morbidity (reduce disability and increase healthy life years); reduction in disease incidence; reduction in cost associated with NCDs; reduction in care disparities and health inequalities due to financial or social factors in vulnerable groups (eg, indigenous groups, ethnic minorities); and empowerment of citizens to more actively manage their health/participate in their healthcare. | 23 (54.8)* | 9 (23.7) | |

| 3.3 National care standards and reporting | 3.3.1 Establish national care/quality standards and standardised reporting for NCDs, care delivery and health outcomes to enable monitoring of care quality. | 8 (19.0)* | 6 (15.8) |

| 3.3.2 †Develop care guidelines/quality standards relevant to the care of people with MSK conditions (eg, rehabilitation guidelines; disability guidelines; community health promotion guidelines that include PA, nutrition, injury prevention and mental health). | – | 1 (2.6) | |

| 3.4 Financing to support NCD care | 3.4.1 Financing for NCD care needs to consider long-term health spending, resources to support implementation of policy/programmes, compulsory insurance, funding only interventions and technologies with proven effectiveness, universal health insurance, and payments linked to performance and quality. | 11 (26.2)* | 7 (18.4) |

| 3.4.2 †Appropriately finance rehabilitation services to ensure appropriate quality care can be delivered sustainably. | – | 1 (2.6) | |

| 3.4.3 †Provide social and financial support packages for people living with disability and/or their carers. | – | 1 (2.6) | |

| 3.5 Policy and regulation | 3.5.1 Ensure health, especially NCD prevention/management, is considered in all public policy and interministerial activity (eg, social policy, ageing policy, employment policy), including the evaluation of policies in terms of health impact. | 12 (28.6)* | 6 (15.8) |

| 3.5.2 NCD prevention and management should be nationally prioritised agenda items. | 1 (2.4)* | 0 (0) | |

| 3.5.3 NCD prevention and management requires strengthening of health governance through the formulation of appropriate health and social policies. These should be evidence-based, enable monitoring of outcomes that are aligned to international targets, address the needs of people with disability and support citizens to actively and positively manage their health. | 9 (21.4)* | 5 (13.2) | |

| 3.5.4 Develop and implement financial and marketing regulation and/or policy measures to support citizens make healthy choices and limit unhelpful commercial influences on health behaviours and outcomes (eg, nutritional information for food, making healthy food affordable, regulation of advertising unhealthy foods, regulation of sales of illicit drugs via social media, tobacco control). | 14 (33.3)* | 4 (10.5) | |

*Strategies relevant to the prevention/management of musculoskeletal health conditions, persistent pain or loss of functional ability/mobility.

†Additional codes added where strategies were specifically related to persistent pain or mobility/functional ability care.

ICT, information and communication technology; MSK, musculoskeletal; NCD, non-communicable disease; PA, physical activity.

General principles for people-centred NCD prevention and management

Policies strongly identified that NCD prevention and management should be based on a continuum of care across the life course. Further, NCD prevention and management should be underpinned by a people-centred (biopsychosocial) approach to planning and delivery. In addition to optimising health, this should consider social and financial consequences and the risks associated with NCDs. Efforts to prevent and manage NCDs should consider healthy behaviours (nutrition, physical activity, safe use of substances) with a strong focus on obesity prevention and management; facilitating a healthy environment (including food safety, air/noise/chemical pollution, climate change); and supporting an active lifestyle. In particular, a focus on increasing population-level physical activity and reducing sedentary exposure across all ages and environments (school, work, home) through multifaceted programmes should be encouraged, monitored and measured. Promoting healthy behaviours and reducing risks for NCDs should also incorporate public health education tailored to target groups with the aim of improving health literacy, supporting positive health beliefs and encouraging effective self-management behaviours. Policies and programmes that target reducing the negative effects of alcohol, narcotics, doping substances and tobacco may also be helpful in reducing harm to people’s musculoskeletal systems.

Person-centred NCD care that includes policy, service design and delivery should be developed and implemented through effective, cross-sector partnerships that include people and their families (including vulnerable groups), government, civil society, health services and industry.

Research that is accessible to decision makers, that addresses societal need in NCD prevention/management, that considers emerging technologies/technology innovations, that examines the value of complementary and alternative medicines, and is policy-relevant, was also cited as an important strategy in some policies.

Service delivery

Interventions/programmes/services for NCD prevention/management should be effective based on health and cost outcomes, should be safe, and be acceptable to consumers. In the context of prevention, timely interventions to identify and manage risk factors, to enable early diagnosis (eg, health checks, screening, education campaigns), and to enable risk classification/stratification, was identified as important. For musculoskeletal health specifically, some policies rationalised the need to include disability assessments as part of national health checks while others cited the need for strategies to prevent injuries across various settings (work, school, recreational).

In the context of disease management, evidence from policies supported that NCDs may be addressed through disease-specific and technology-enabled models of care. Such models must address a specific population/clinical group (such as the Danish care pathway for musculoskeletal conditions); be informed by clinical guidelines/evidence and by criteria that support effective clinical decision making (eg, improved diagnostics) and adopt appropriate stepped care; and identify implementation strategies and mechanisms for monitoring effectiveness, safety and quality improvement. Specific to musculoskeletal health, some policies identified the need to support specific strategies for obesity prevention/reduction, to improve mental healthcare and for targeting arthritis as a specific priority condition.

Policies identified that improved NCD management may be achieved through services that are accessible (ie, geographically accessible, accessible thorugh appropriate infrastructure, and supported by technology eg telehealth and information exchange to improve access) irrespective of age, gender, residence and socioeconomic status; and that are culturally acceptable. Access to essential medicines and laboratory medicine facilities were considered critical. Leveraging digital technologies to mitigate care disparities imposed by geographical and socioeconomic barriers and to facilitate access to high-value NCD care for vulnerable groups/populations, was supported.

Where possible, evidence suggested that health services should be delivered in community settings by multidisciplinary care teams. For musculoskeletal health specifically, rehabilitation providers within multidisciplinary teams and community-based rehabilitation services were seen as important, together with comprehensive care plans that support return to work and/or social participation. To ensure holistic care, policies indicated that service delivery should be integrated between services, settings and regions. Capacity building in the workforce was highlighted as a critical enabler to supporting the delivery of the right NCD care (eg, development of core competencies that include ageing, mental health, obesity management, physical activity), with a particular focus on primary care providers.

In the context of supporting older people living with NCDs, policies recommended the implementation of specific strategies and indicators to support healthy ageing, including: health promotion, health checks, interventions to address functional impairments, development of a model of care for older people that includes geriatric care and support for long-term care systems.

System strengthening

To inform NCD prevention/management planning and system-level responses, there is a need for population health monitoring. Relevant system performance targets should include NCD risk factor reduction, prevention of premature mortality, morbidity reduction, disease incidence reduction, reduction in health economic burden associated with NCD care, and health inequality and care disparity reductions. To support health systems, there is a need to establish national care/quality standards and standardise reporting practices for NCDs. Findings suggested a need to develop guidelines or quality care standards that are relevant for people living with musculoskeletal health impairments, such as rehabilitation and disability guidelines. At a broader level, building capacity in the system to respond to health disasters and epidemics was identified as important.

Financing for NCD care was considered essential to address long-term health spending, to ensure appropriate resourcing of policy/programme implementation initiatives, to ensure there are compulsory insurance schemes to act as a mechanism for financial sustainability (eg, universal health insurance), and to support funding of only interventions and technologies with proven effectiveness and safety, and finally, develop and implement financing models linked to performance and quality. In the context of positively influencing musculoskeletal health services, providing appropriate financing for rehabilitation services and for social and financial support packages for people living with disability, were identified as important factors for the prevention and management of musculoskeletal health, pain and mobility.

NCD prevention and management was considered as needing to be nationally prioritised and actioned through a whole-of-government approach. Health and social care policy was identified as necessary for NCD care and public health and policies indicated that this should be evidence-informed for effective prevention and management initiatives. Further, policy should explicitly allow for capture of outcomes that align with international targets. Regulation (eg, through policy and financial levers) also emerged as a key area that should be used to enable healthy lifestyle choices and support healthy behaviours; for example, disincentivising unhealthy foods, tobacco, substance use and unhelpful advertising.

Implementation and internal validity

Information to support implementation was provided in 38 (86.4%) polices from 29 (96.7%) countries. Across specific domains of implementation, priorities for implementation were described in 19 (50.0%) policies, timelines or phasing of implementation activity in 23 (60.5%) policies, financing arrangements to support implementation in 26 (68.4%) policies, and identification of agencies responsible for implementation actions in 37 (97.4%) policies (online supplementary file 4 provides these details by policy).

bmjgh-2019-001806supp004.pdf (69.7KB, pdf)

Internal validity sum scores ranged from 0 to 13 across policies, with a mean score of 7.6 (95% CI 6.5 to 8.7).

Discussion

Main findings