Abstract

Several viruses exploit clathrin-mediated endocytosis to gain entry into host cells. This process is also used extensively in biomedical applications to deliver nanoparticles (NPs) to diseased cells. The internalization of these nano-objects is controlled by the assembly of a clathrin-containing protein coat on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane, which drives the invagination of the membrane and the formation of a cargo-containing endocytic vesicle. Current theoretical models of receptor-mediated endocytosis of viruses and NPs do not explicitly take coat assembly into consideration. In this paper we study cellular uptake of viruses and NPs with a focus on coat assembly. We characterize the internalization process by the mean time between the binding of a particle to the membrane and its entry into the cell. Using a coarse-grained model which maps the stochastic dynamics of coat formation onto a one-dimensional random walk, we derive an analytical formula for this quantity. A study of the dependence of the mean internalization time on NP size shows that there is an upper bound above which this time becomes extremely large, and an optimal size at which it attains a minimum. Our estimates of these sizes compare well with experimental data. We also study the sensitivity of the obtained results on coat parameters to identify factors which significantly affect the internalization kinetics.

Keywords: nanoparticle, virus, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, random walk, vesicle formation

1. Introduction

Several biomedical applications, including targeted-drug delivery and diagnostic imaging, utilize clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) to deliver ligand-coated nanoparticles (NPs) to diseased tissues and cells (see review articles [1–3] and references therein). CME is also exploited by several viruses, including hepatitis C, influenza A, and dengue, to gain entry into host cells [4–8]. Understanding the details of how these nano-sized objects are taken up by cells via this internalization pathway is crucial for designing efficient NPs for biomedical purposes, as well as for developing strategies to inhibit cellular entry of viruses.

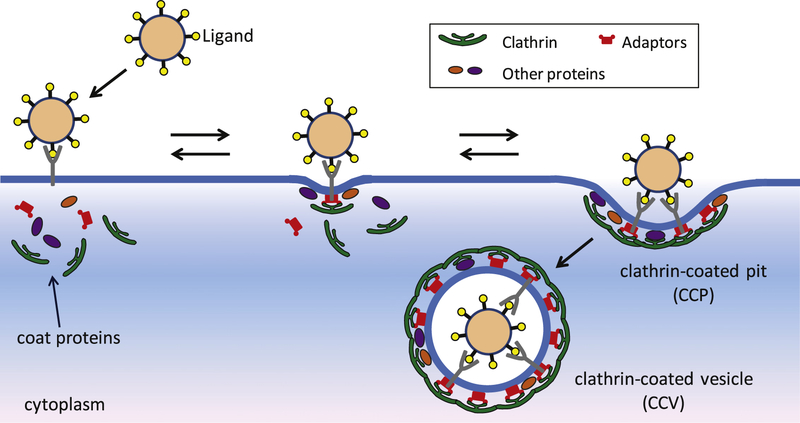

CME is one of the most important and best characterized forms of receptor-mediated endocytosis [9, 10]. Eukaryotic cells use this pathway to internalize nutrients, growth factors, transmembrane receptors, etc. Internalization of these molecules occurs through specialized regions of the plasma membrane called clathrin-coated pits (CCPs), which form by the assembly of a protein coat on the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane. The assembly of the coat—which contains clathrin, adaptors (AP-2), and several other accessory proteins—drives the bending of the membrane [11, 12], eventually leading to the formation of a cargo-containing clathrin-coated vesicle. The internalization of NPs/viruses (henceforth referred to as NPs unless stated otherwise) via CME involves two main steps. First, the formation of bonds between receptors on the cell surface and ligands on a NP anchors the particle to the plasma membrane. Second, the assembly of a CCP drives the formation of a vesicle containing the NP (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of NP internalization via clathrin-mediated endocytosis. A NP first binds to a specific cell surface receptor, forming a NP–receptor complex. The complex binds the coat proteins, and clathrin-coated pit (CCP) assembly begins. The CCP either grows to form a vesicle, in which case the NP is internalized, or grows only up to a certain size and subsequently disassembles. In such an event the NP fails to be internalized and the complex becomes free of coat proteins.

Several theoretical and computational models of receptor-mediated endocytosis of NPs, as well as passive wrapping of NPs by flexible membrane, have been proposed [13–18]. An assumption common to all these models is that the wrapping of the membrane around the NP is solely controlled by the formation of bonds between receptors on the membrane and ligands on the NPs. The models do not take clathrin coat assembly into explicit consideration. Since coat assembly plays a key role in CME of NPs, the above mentioned models are insufficient for understanding CME of these nano-objects.

To fill the gap, we here present a theoretical framework for studying CME of single NPs that focuses on protein coat assembly. We characterize the internalization process by the mean time between the binding of a NP to the membrane and its entry into the cell, and derive an analytical formula for this quantity. The formula contains two terms with a clear physical meaning: the first, τw, corresponds to the mean time that a NP spends bound to the membrane waiting for an ultimately-successful CCP assembly event (leading to the formation of a vesicle) to begin, and the second, τs, corresponds to the mean time required for a successful CCP assembly event, once begun, to go to completion. Our analysis of the sensitivity of these times to the parameters describing coat assembly shows that τw is much more sensitive to the parameter values than τs, and therefore could potentially be a target for improving NP design. We also study the dependence of the two times on the NP size to address the question: how the kinetics of CME of a NP is affected by the size of the particle.

2. General theory

2.1. Mean internalization time

As mentioned in section 1, we characterize the internalization process by the mean time between the binding of a NP to the membrane and its entry into the cell. We call this time the mean internalization time and denote it by τ. In order to calculate this time, like in previous models [13, 16], we assume that the binding of NP to the plasma membrane through the formation of a receptor–ligand bond is irreversible.

To derive a formula for τ, consider an ensemble of NP–receptor complexes formed on the cell membrane at time t = 0. Let τ0 be the mean time required for the initiation of CCP assembly around a NP–receptor complex. CCP assembly is a reversible process which has two possible outcomes [19, 20]. One is that the assembly is successful, in which case the CCP grows in size to form a vesicle and the NP is internalized. The other possibility is that the assembly is unsuccessful, and the CCP grows only up to a certain size and then disassembles, in which case the NP fails to be internalized.

Let Ps and Pf = 1 − Ps be the probabilities that a CCP assembly process is successful or failed, respectively, and τs and τf be the mean durations of these events. Then the mean internalization time can be written as

| (1) |

The first term on the right-hand side of the above equation is the contribution from the fraction (Ps) of complexes which bind to coat proteins and are internalized on the first attempt, i.e., without experiencing complete disassembly. The second term is the contribution from the fraction (Pf Ps) of complexes that are internalized on the second attempt, i.e., they first bind to coat proteins but fail to get internalized and then bind for the second time and are internalized. Subsequent terms can be understood in the same way.

Upon summing the series in equation (1), we find that the internalization time can be written as the sum of two terms

| (2) |

Here τw is the mean waiting time defined as the mean duration between the initial attachment of a NP to a receptor on the cell membrane and the commencement of a successful CCP assembly event. This time is given by

| (3) |

In the above equation, τ0/Ps, is the mean cumulative time that a NP–receptor complex spends when disconnected from coat components, and Pf τf/Ps is the mean cumulative time a complex spends bound to CCPs that fail to grow into a complete vesicle.

In experiments studying CME of individual viral particles using TIRF microscopy, the times between viral binding and the onset of CCP formation, as well as the time between the onset of CCP formation and clathrin-coated vesicle uncoating, are measured [5–8]. These times are closely related to the times τw and τs described above. It is also worth mentioning that τ is identical to the ‘wrapping time’ calculated in previous models [13, 16, 17]. However, the wrapping mechanism based on receptor–ligand bonding considered in these models is completely different from the coat assembly based mechanism considered in the present paper.

2.2. Coarse grained model

The formula in equation (1), giving the mean internalization time as a sum of two times, τw and τs, is simple and intuitively appealing. But the calculation of τw and τs in the case of CME is nontrivial. To obtain these quantities we adapt the approach developed in [26] and [27] to study the lifetime distribution of events corresponding to unsuccessful CCP assembly. Such CCPs typically contain no cargo and are called abortive [19, 20]. Here we briefly describe the approach and list the underlying assumptions.

The coat that forms during CCP assembly is made up of several proteins and has a complex structure. Clathrin (in the form of a three-legged, triskelion-shaped complex) is the most abundant protein in the coat. Clathrin triskelions polymerize to form a polyhedral scaffold which is linked to the membrane through adaptor proteins (typically AP-2 at the plasma membrane). The scaffold stabilizes membrane curvature, and its growth is governed by the topological constraints imposed by the intrinsic shape of a triskelion. Other proteins like epsin and amphiphysin bind to the cell membrane and impart local curvature. In addition to the structural and geometrical complexity, the temporal order in which these proteins arrive at the site of CCP assembly also plays an important role.

Modeling the spatiotemporal dynamics of such a multicomponent system is an extremely difficult task. Nevertheless, by using a coarse-grained approach different phenomena related to vesicle formation have been studied. These include the dynamical coupling between coat assembly and membrane shape change during CME in yeast [21], the dynamics of COP vesicle formation in the Golgi [22], the effects of actin forces and proteins containing Bin-Amphiphysin-Rvs (BAR) domains on endocytosis in yeast [23], and the rearrangement of clathrin-shaped polyhedral elements during vesicle budding from flat lattices [24, 25]. However, these models do not focus on the stochastic nature of the coat assembly process, and therefore cannot not be readily used to calculate our quantity of interest—the mean internalization time, τ.

We previously developed a coarse-grained description of the assembly dynamics to analyze the lifetime distribution of abortive CCPs [26]. Here we adapt that model to study endocytosis of NPs. The main idea of the model was to replace the real protein coat by a coat made up of identical units referred to as monomers (figure 2(a)). We assumed that (1) the coat made up of monomers has a bending rigidity and a spontaneous curvature, (2) the shape of the model CCP is a spherical cap, and (3) pit assembly proceeds via reversible binding of monomers on the edge of the pit. Due to coarse-graining, the finer details of the assembly process were lost, but nevertheless the model was able to capture the lifetime distribution of abortive CCPs very well [26].

Figure 2.

(a) Coarse-grained model for the assembly of a clathrin-coated pit (CCP). In a real CCP the protein coat contains clathrin, adaptors and several other accessory proteins. In our model of a CCP the coat is made of identical monomeric units. The shape of the CCP is assumed to be a spherical cap, and the average area of a monomer is chosen to be the same as that occupied by a clathrin triskelion in a real CCP. (b) Kinetic scheme of the pit assembly shown in (a). Symbols n and N refer to the number of monomers in a pit and a complete vesicle, respectively. The rate constants αn and βn characterize the growth and decay rates of a pit of size n. k0 is the rate at which the first monomer binds to the NP–receptor complex, and kN is the rate of scission of a vesicle from the membrane.

The coarse-grained model discussed above allows us to describe the dynamics of CCP assembly around a NP–receptor complex as a nearest-neighbor random walk on a one-dimensional lattice containing N + 1 sites. The kinetic scheme of such a random walk is shown in figure 2(b), where n is the number of monomers in a pit and n is the number of monomers needed for a complete vesicle. The rate constants αn and βn characterize the growth and decay rates of a pit of size n, k0 = 1/τ0 is the rate constant for binding of the first monomer to the NP–receptor complex, and kN is the rate constant for the scission of a vesicle from the membrane. Analysis of CCP dynamics in living cells shows that scission is a fast process [19, 20]. Therefore, to keep things simple we choose kN = ∞. Note that a finite scission rate can be easily incorporated in our analysis.

For the kinetic scheme in figure 2(b), the quantities Ps and Pf entering into equation (3) are the probabilities that a random walk, starting from site n = 1, eventually reaches sites n = n and n = 0, respectively, and the times τs and τf are the mean durations of the two processes (which formally are conditional mean first-passage times [28, 29]). Analytical expressions for these quantities are given by [28]

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

Here, the functions Ψn and Φn are

| (7) |

where is the formation free energy for a pit containing n monomeric units, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature. The above formulas are obtained assuming that the forward and backward rate constants are related through detailed balance,

| (8) |

3. Model details

To calculate the mean internalization time by means of equations (2)–(6) we need to know the rate constants αn and βn, as well as the free energy of pit formation, F(n). We now discuss these quantities.

3.1. Rate constants

A pit grows by the addition of a monomer to its edge, which has multiple binding sites. We assume that all the binding sites are identical and the monomer can bind to any one of them with equal probability. Keeping this in mind, we choose the forward rate constants to be

| (9) |

where γ is a kinetic parameter, and the functionf(n, N) gives the number of available binding sites on the edge of a pit of size n. Using the approximation that the shape of a pit is a spherical cap, this function can be written as

| (10) |

where ρ is a dimensionless parameter whose value is chosen to be 2 (see the appendix).

The rate constant β1 describes the dissociation constant of the first monomer. This rate constant is unknown, and we treat it as a free parameter. As shown later, β1 plays an important role as it significantly affects the mean internalization time, our main quantity of interest. Other dissociation rate constants, βn, n = 2, 3, …,N, are given by equation (8).

3.2. Free energy of pit formation

The formation free energy of a pit made of n monomers and having a curvature c can be written as [22, 26]

| (11) |

The first term in the right-hand side is the Helfrich energy [30] describing the energetic cost of bending the cell membrane assuming that its spontaneous curvature is zero. The second term represents the bending energy of the protein coat. The third term represents the effective binding energy of a monomer to the coat, and the fourth term is the line tension energy. The parameters κm and κp are the bending rigidities of the cell membrane and the coat, respectively, cp is the spontaneous curvature of the protein coat (in the absence of the membrane), ∈b is the effective monomer binding energy, i.e., the difference between the binding energy and entropic cost of immobilizing the monomers, σ is the edge-energy constant, and λ is the average area occupied by a monomer.

In our model the vesicle size is characterized by the number of monomers needed to complete a vesicle. This number, N, is related to the curvature of the pit by 4π/c2 = λN. Similarly the natural curvature of the protein coat, cp, and the natural number of monomers in the coat, Np, are related by . By substituting these relations into equation (11), we can write the formation free energy of a pit made of n monomers as

| (12) |

where

| (13) |

3.3. Parameter values

The values of the parameters used in our calculation are summarized in table 1. The rationale behind the choices is as follows: the value of κm typically lies between 10 and 25 kB T[31]; we choose κm = 20 kB T. The size distribution of clathrin baskets assembled in vitro using adaptor protein AP-2 is typically narrow and has a peak close to dp = 90 nm in diameter [32].

Table 1.

Parameter values.

| Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| κm | Membrane bending rigidity | 20 kBT |

| κp | Protein coat bending rigidity | 200 kBT |

| Np | Number of monomers in a typical vesicle | 80 |

| ϵb | Binding energy per monomer | 10 kBT |

| 2σ | Edge energy constant | 5 kBT |

| γ | Kinetic parameter | 0.18 s−1 |

| τ0 | Average time for initiation of a CCP | 5 s |

| kN | Vesicle scission rate | ∞ |

| λ | Average area occupied by a monomer | 310 nm2 |

| lb | Length of receptor ligand bond | 15 nm |

Using the average area occupied by a clathrin molecule, λ = 310 nm2, and the relation , we find that a 90 nm basket would have approximately 80 clathrin triskelions, which we take to be the natural coat size, i.e, Np = 80. The value of λ = 310 nm2 was estimated using the relation between diameters of clathrin baskets of different sizes and the number of clathrin triskelions they contain [33].

In [26], using experimental data on the lifetime distribution of abortive CCPs (CCPs with no cargo), we estimated the value of the effective binding energy per monomer, ∈b, to be approximately 5 kB T. Experiments show that with cargo (present case) the binding energy increases [34]. An approximate range for its value can be determined using the following argument: for a clathrin-coated vesicle to be energetically stable, the effective binding energy has to be greater than the membrane bending energy (8πκm ≈ 500 kB T). Since a typical vesicle has 80 monomers, the binding energy per monomer should be greater than 500/80 ≈ 6 kB T. To get an upper bound to the binding energy we consider the interaction energy between proteins containing a BAR domain, which produce membrane curvature during CME, and the cell membrane. The electrostatic binding energy between BAR domains and membrane is estimated to be approximately 15kB T [35]. We choose a number between these values and set ∈b = 10 kB T.

The parameter, κp, captures the effective bending rigidity of the protein coat. This parameter, together with the natural curvature of the coat, determines the typical size of a vesicle. In [26], using the typical size of a vesicle to be 100 nm in diameter (which is somewhat larger than the average size of a basket), we estimated the value of this parameter to be approximately κp = 200 kB T; here we use the same value. We choose the edge energy constant 2σ = 5 kB T [22] and the length of a receptor ligand bond to be lb = 15 nm [36]. Parameters γ and ρ have the same values as in [26]: ρ = 2, γ = 0.18 s−1.

4. Quantities of interest

Next we look at the dependences of the quantities of interest on the NP size and the parameter β1. When drawing these dependences we relate the number of monomers in a vesicle, N, to the NP diameter, dNP, by the relationship

| (14) |

where lb is the length of the receptor–ligand bond between the NP and the cell membrane. Note that this assumes that there is only one NP inside a vesicle, as illustrated in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Relation between NP and vesicle diameters. The vesicle diameter, dV, and the NP diameter, dNP, are related by dV = dNP + 2lb, where lb is the length of a receptor–ligand bond.

4.1. Free energy of pit formation

As mentioned earlier, the energetics of coat formation (see equation (12)) plays an important role in determining the fate of the coat assembly process (successful or failed). The dominant term in that equation is E(N) n. The function E(N), given in equation (13), contains the membrane bending energy per monomer (the first term on the right-hand side), which opposes coat assembly, and the energy gained due protein coat formation per monomer (the sum of the second and third terms on the right-hand side), which favors coat assembly. Figure 4 shows the dependence of these energies and E(N) on the NP size.

Figure 4.

Average energy per monomer, E(N), equation (13), (solid curve) as a function of NP size. E(N) is the sum of the membrane bending energy per monomer (dashed curve) and the energy due to coat formation per monomer (dashed–dotted curve). Dashed vertical lines atdmin ≈ 46 nm and dmax ≈ 105 nm correspond to the NP sizes at which E (N) = 0. The arrow at nm indicates the size of the NP whose carrier vesicle is energetically most stable.

The membrane bending energy per monomer (the dashed curve in figure 4) decreases monotonically with dNP. The energy gained due to coat formation (the dashed–dotted curve) attains a minimal value when the vesicle has the same curvature as the natural curvature of the protein coat (90 nm). Using the relation between NP and vesicle sizes we find that such a vesicle would carry a 60 nm NP. The total energy attains a minimum at . An analytical formula for this size can be found by solving the equation ∂E (N)/∂N = 0, which leads to

| (15) |

The vertical dashed lines at dmin ≈ 46 nm and dmax ≈ 105 nm show the NP sizes at which E(N) = 0. At these sizes, the factors favoring and opposing coat assembly balance out. The lower size is mainly determined by the competition between the membrane bending energy and the coat binding energy, whereas the upper size is determined by the coat bending energy and coat binding energy. Analytical expressions for dmin and dmax can be obtained by solving the equation E(N) = 0, which leads to

| (16) |

where , , and .

4.2. Probability of successful CCP assembly

Next we consider the probability of succesful CCP assembly, Ps, given in equation (4). Figure 5 shows the dependence of this probability on the NP size for different values of the parameter β1. The dependence of Ps on the NP size can be understood by considering the energy function shown in figure 4. In regions where E > 0, pit assembly is energetically unfavorable and Ps is negligibly small. In contrast, in the middle region where E < 0, pit assembly becomes energetically favorable, and Ps rises sharply. Interestingly, sizes of several viruses which are internalized via CME, including dengue virus (40–60 nm), semliki forest virus (50–70 nm), reovirus (60–80 nm), and influenza A (80–120 nm) roughly fall in this range where Ps is relatively high.

Figure 5.

The probability of successful CCP assembly around a NP–receptor complex, Ps, as a function of the NP size. Ps is high in the region where E < 0, and pit assembly is energetically favorable. The maximum value of Ps is sensitive to the parameter β1, the values of which in s−1 are given near the curves. The dashed vertical lines are the same as in figure 4.

The maximum value of Ps decreases with increasing β1, which is not surprising since a higher value of β1 means a higher dissociation rate of the NP–receptor complex from the first monomer. As discussed later, using the data on internalization kinetics of viruses, we estimate the value of β1 to be somewhere between 2 and 8 s−1. Note, for this range of β1 the maximum value of Ps is small, which means that a virus makes many failed attempts (1/Ps) before being internalized.

The probability of sucessful CCP assembly becomes negligibly small for NPs smaller than dmin or larger than dmax. Thus, these sizes correspond to the smallest and largest NPs that can be internalized via CME. The lower estimate, dmin ≈ 46 nm, cannot be compared with experimental data since our model assumes that there is only one NP per vesicle, whereas in reality small NPs may enter CCPs in clusters [37] or along with other cargo molecules. Nevertheless, our estimate of the smallest vesicle size of 76 nm, obtained using the relation dV = dNP + 2lb (see figure 3), compares very well with the size of smallest clathrin-coated vesicles observed in experiments [38]. Our estimate of dmax ≈ 105 nm is somewhat smaller than the reported value of 200 nm for NPs [39, 40]. We comment on the possible reasons for this discrepancy in section 5.

4.3. Mean waiting time, and mean time for successful CCP assembly

The mean internalization time, τ, is the sum of two terms (see equation (2)): the mean waiting time τw, and the mean time for successful CCP assembly, τs. Figure 6 shows the dependences of these two times on NP size, calculated using equations (3)–(6). We focus on the region between dmin and dmax, where the probability Ps is not too low. We found that τs changes very little when we vary β1. Therefore, we show only the curve for β1 = 5 s−1. The trend of τs can be understood by considering the dynamics of coat assembly. As seen in figure 6, the time τs attains a minimum at ds ≈ 55 nm (shown by the arrow). For this value of the NP size, E ≈ −3 kB T (see figure 4) and, hence, according to the condition of detailed balance, αn/βn ≈ 20 ≫ 1. This implies that during the endocytosis of a NP of size ds, the growth of the coat proceeds with a low probability of monomer dissociation. Thus, τs is determined by the rate of arrival of a new monomer. When the NP diameter is slightly larger than ds the inequality αn/βn ≫ 1 is still true, but the number of monomers needed to wrap a NP increases and, hence, τs increases with NP size. As the NP size approaches dmin or dmax, the rate constants αn and βn become comparable. Consequently, during coat assembly the dissociation of monomers becomes more frequent, which causes τs to increase markedly. Values of τs predicted by our model fall in the same range as the experimentally measured times needed for clathrin-coated vesicle formation [20], as well as the τs values for viruses which are internalized via CME (given in table 2).

Figure 6.

Mean time for successful CCP assembly, τs (solid curve) and the mean waiting time, τw, (curves with symbols) for different values of β1, as functions of the NP size, calculated using equations (3)–(6). In contrast to the time τs (only the curve for β1 = 5s−1 shown), the time τw changes significantly with β1. The dashed vertical lines are the same as in figure 4. The arrow indicates the NP diameter ds, at which τs is minimum.

Table 2.

Values of the mean waiting time, τw, and the mean time for successful CCP assembly, τs, measured for virus and virus-like particles. Internalization of these particles via clathrin-mediated endocytosis was monitored using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy [5–8]. The acronyms IHNV and DI-T stand for infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus and defective interfering particle, respectively.

Figure 6 also shows the mean waiting time, τw = (τ0 + Pf τf)/Ps, for different values of parameter β1. In contrast to τs, the time τw changes significantly with the variation of β1. To calculate τw we need the values of τ0 and β1, both of which are not known. To make a reasonable choice for these parameters we use the fact that during the assembly process the average growth rate of a CCP is between one and two triskelions per second [19]. This means the time interval between the arrival of triskelions is approximately 1 s. We assume that the CCP initiation time is slightly longer than the clathrin arrival time but much shorter than τs, and choose τ0 = 5 s. Then, to get a range for β1, we make use of the fact that, in the case of viruses, the magnitude of experimentally-determined times τw and τs are comparable (see table 2). Our analysis shows that the two times have similar values when β1 falls in the range 2–8 s−1 (see figure 6). Moreover, we find that the numerator in the formula for the mean waiting time, τ0 + Pf τf, is small compared to τs, and depends weakly on the NP size. Thus, the dependence of τw on the NP size is mainly determined by the factor 1/Ps (see equation (3)).

4.4. Mean internalization time

Figure 7 shows the dependence of the mean internalization time, given in equation (2), on NP size, for different values of the parameter β1. This is our main quantity of interest. The mean internalization time attains a minimum at a diameter which we designate to be dopt (shown with arrows). The curves in figure 7 show that dopt does not change much with β1, although the value of τ at dopt changes appreciably. For example, as β1 varies from 2 to 8 s−1, the value of dopt changes from 58 to 63 nm, but the value of τ at dopt changes from 109 to 202 s.

Figure 7.

The mean internalization time, τ, given in equation (2), as a function of the NP size, for different values of β1. The arrows point to the NP diameters corresponding to the shortest values of the mean internalization time, which we refer to as dopt. The value of dopt is weakly sensitive to changes in β1, but the value of τ at dopt varies significantly. The dashed vertical lines are the same as in figure 4.

From the above analysis we find that the dependence of τ on the NP size can be characterized by four quantities, namely dmin, dmax, dopt and, τ (dopt), where the latter is the value of τ at dopt. These quantities are functions of the coat parameter values, which, in principle, can change from one cell type to another. Figure 8 illustrates the dependence of these quantities on the coat parameters κp, Np, and ∈b. Among the characteristic sizes, the maximum NP size dmax, shows appreciable variation whereas the other sizes show only weak dependences on the coat parameters. The value of τ (dopt) is most sensitive to the parameter ∈b. It rises rapidly as ∈b decreases, and becomes less than 8 kB T. Figures 8 (b), (d), (f) also contain plots of τs (dopt), which is the value of τs at dopt. The weak dependence of this quantity on coat parameters shows that the increase in the value of τ (dopt) is mainly due to the increase in the value of τw at dopt. Thus, similar to its sensitivity to the parameter β1, the time τw is more sensitive than is τs to other coat parameters.

Figure 8.

Plots of dmin, dmax (equation (16)), dopt, τ (dopt), and τs (dopt) (calculated numerically), as functions of κp—the bending rigidity of the protein coat ((a) and (b)), ∈b—effective monomer binding energy ((c) and (d), and Np—the natural number of monomers in the coat ((e) and (f)). Among the characteristic sizes only the maximum NP size dmax shows significant variation. The time τ (dopt) is the sum of τs (dopt) and τw (dopt). The weak dependence of τs (dopt) on coat parameters shows that the increase in τ (dopt) is mainly due to the increase in τw (dopt). The arrows show the parameter values used in our calculations.

5. Summary and discussion

In this paper we provide a theoretical framework for studying endocytosis of NPs and viruses via CME. Our model, which focuses on coat assembly, captures the stochastic dynamics of coat formation around a NP–receptor complex and the resulting probabilistic nature of the NP internalization process. Briefly, if the assembly is successful the CCP grows to form a vesicle and the NP is internalized. In contrast, if the assembly fails, then the NP–receptor complex has to wait for the initiation of a new CCP. We derive an analytical formula for the mean internalization time, defined as the mean time between the binding of a NP to the membrane and its entry into the cell. The formula has two terms; the first, τw, which we refer to as the mean waiting time, corresponds to the mean time a complex spends on the membrane before successful CCP assembly starts, and the second term, τs, is the mean duration of a successful CCP assembly event.

Experiments show that in the case of different viruses internalized via CME, the time τw is of the same order of magnitude as τs (see table 2). Based on this we infer that the probability of successful CCP assembly, Ps, is small; therefore, even though the time spent in a single failed event is relatively short, the total time in failed attempts becomes large and comparable to the time for successful CCP assembly. Analysis of the dependence of the times τw and τs on the parameters describing coat assembly shows that the former is more sensitive than the latter, because Ps depends strongly on the coat parameters. This brings forth an important point which has not emerged from previous models—the mean waiting time should be the focus of studies trying to improve the internalization efficiency of NPs.

As discussed earlier, there is an upper bound on the size of NPs which can be internalized via CME. When the diameter of the NP exceeds 105 nm, the coat has to be distorted significantly from its natural curvature in order to accommodate the NP inside a vesicle. Due to the increase in coat distortion energy, the probability of successful CCP assembly becomes very small and the mean internalization time becomes extremely large. Our estimate dmax ≈ 105 nm is smaller than the reported value 200 nm for NPs [39, 40]. There could be different reasons for this discrepancy. For example, dmax is sensitive to coat parameter values (see figure 8), and in our coarse-grained model the parameter values might be somewhat inaccurate. Alternatively, it could be that during internalization of larger NPs, only a partial clathrin coat, rather than a complete clathrin-coated vesicle, forms. Indeed, such fractional clathrin-containing coats are known to form around Listeria bacteria [47] and vesicular stomatitis virus [8]. However, in such cases actin is required for internalization [8]. The previously-mentioned theoretical models do not take the clathrin coat assembly into explicit consideration and therefore fail to capture the constraint imposed by coat energetics. In these models the upper bound is determined by a combination of factors including the binding energy, the number of receptors available on the cell membrane, and the membrane tension [13, 14, 17]. These models predict that NPs significantly larger than 200 nm can be internalized, which is inconsistent with experimental observations from [39] and [40].

We find that the mean internalization time is shortest when the NP size is close to 60 nm, and that this optimal size is weakly sensitive to variations in the values of the coat parameters. This observation is consistent with the findings of several experiments done to study size dependence of NP endocytosis. In these experiments different cells, NPs, and ligands were used, yet the optimal size was always found to be close to 50 nm (see table 3). Different models have been used to explain this observation. Certain models indicate that the time it takes for a NP to be wrapped by the membrane via receptor–ligand bond formation is shortest for 50 nm NPs [13]. Other models calculate the number of NPs a cell can internalize, and conclude that the number is highest for 50 nm NPs [14]. The fact that such different approaches predict the same optimal size, while interesting, makes it difficult to discriminate between the applicability of different theoretical models solely based on the predicted optimal NP size.

Table 3.

Summary of experiments on the size dependence of cellular uptake of NPs. NPs smaller than 200 nm are internalized via receptor-mediated endocytosis, whereas for larger NPs other internalization mechanisms are involved [39, 40]. Bold faced numbers indicate the NP size for which the cellular uptake is highest.

| Cells | NPtype | NP size (diameter nm) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| B16-F10 | Latex beads | 50,100,200,500 | [39] |

| MNNG/HOS | Metal hydroxide | 50,100,200,350 | [40] |

| Hela,STO,SNB19 | Gold | 14,30,50,74,100 | [41] |

| Hela | Quantum dots | 5,15,50 | [42] |

| CLl-0,Hela | Gold | 45,75,110 | [43] |

| HeLa | Mesoporous silica | 30,50,110,170,280 | [44] |

| A549,HeLa,MDA | Gold | 15,30,45 | [45] |

| Caco-2 | Liposomes | 40,72,86,97,162 | [46] |

Some limitations of our approach are as follows. Like in other models, we assumed that NP–receptor binding is irreversible. However this assumption is valid only if the lifetime of receptor–ligand bond is much larger than the mean internalization time of a NP. Otherwise, the dissociation of the complex should be taken into consideration. Also, we do not consider in detail the initial step of CME, where multiple bonds between ligands on the NP and receptors on membrane may form. This would lead to clustering of receptors in a CCP, which is important in early stages of CCP assembly, as the binding of the cytoplasmic parts of the receptors to the coat proteins is known to stabilize the clathrin coat. In this context, it has been shown that the chances of successful CCP assembly around transferrin receptors (which are internalized via CME) increases when the receptors are clustered [48], and also that the internalization rate of virus-like particles increases when the number of ligands on the virus are increased [49]. Although, our model does not account for these factors, based on our sensitivity analysis (see figures 5 and 8), we think that increasing the number of ligands increases the probability of successful CCP assembly around the NP, leading to a decrease in the mean waiting time and the mean internalization time (as observed in [49]).

To conclude, in order to capture a complete picture of NP internalization via CME, a comprehensive theory which couples both aspects of the cellular endocytic machinery—bond formation and coat assembly—is needed. We believe our work is a step in that direction.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the Center for Information Technology.

Appendix. Derivation of f (n, N), as given by equation (10)

Using spherical coordinates (see figure 9), the surface area of the pit can be written as

| (17) |

where R is the radius of a sphere having the same curvature as the pit, and λ is the average area occupied by a monomer. This leads to the relation between cos (θ) and the number of monomers, n, in the pit,

| (18) |

We use the above equation to infer the radius, r(n), of the circular growing edge of a pit as a function of n,

| (19) |

Introducing the average linear span of the monomer, denoted by L, we find that the number of available binding sites on the periphery of the pit is

| (20) |

By changing variables from R to N using the relation 4πR2 = λN, we arrive at

| (21) |

where ρ is a dimensionless parameter given by . The value ρ = 2 gives the correct number of available binding sites for n = 1.

Figure 9.

Spherical cap model of a pit.

References

- [1].Bareford LM and Swaan PW 2007. Endocytic mechanisms for targeted drug delivery Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 59 748–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Iversen TG, Skotland T and Sandvig K 2011. Endocytosis and intracellular transport of nanoparticles: present knowledge and need for future studies Nano Today 6 176–85 [Google Scholar]

- [3].Akinc A and Battaglia G 2013. Exploiting endocytosis for nanomedicines Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 5 a016980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Blanchard E, Belouzard S, Goueslain L, Wakita T, Dubuisson J, Wychowski C and Rouille Y 2006. Hepatitis C virus entry depends on clathrin-mediated endocytosis J. Virol 80 6964–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rust MJ, Lakadamyali M, Zhang F and Zhuang X 2004. Assembly of endocytic machinery around individual influenza viruses during viral entry Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 11 567–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].van der Schaar HM, Rust MJ, Chen C, van der Ende-Metselaar H, Wilschut J, Zhuang X and Smit JM 2008. Dissecting the cell entry pathway of dengue virus by single-particle tracking in living cells PLoS Pathog. 4 e1000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liu H, Liu Y, Liu S, Pang DW and Xiao G 2011. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis in living host cells visualized through quantum dot labeling of infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus J. Virol 85 6252–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cureton DK, Massol RH, Whelan SPJ and Kirchhausen T 2010. The length of vesicular stomatitis virus particles dictates a need for actin assembly during clathrin-dependent endocytosis PLoS Pathog. 6 e1001127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mousavi SA, Malerod L, Berg T and Kjeken R 2004. Clathrin-dependent endocytosis Biochem. J 377 1–6 116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].McMahon HT and Boucrot E 2011. Molecular mechanism and physiological functions of clathrin-mediated endocytosis Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12 517–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zimmerberg J and Kozlov MM 2006. How proteins produce cellular membrane curvature Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 7 9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ungewickell EJ and Hinrichsen L 2007. Endocytosis: clathrin-mediated membrane budding Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 19 417–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gao H, Shi W and Freund LB 2005. Mechanics of receptor-mediated endocytosis Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102 9469–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhang S, Li J, Lykotrafitis G, Bao G and Suresh S 2009. Size-dependent endocytosis of nanoparticles Adv. Mater 21 419–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yuan H, Li J, Bao G and Zhang S 2010. Variable nanoparticle– cell adhesion strength regulates cellular uptake Phys. Rev. Lett 105 138101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Decuzzi P and Ferrari M 2007. The role of specific and non-specific interactions in receptor-mediated endocytosis of nanoparticles Biomaterials 28 2915–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mirigian S and Muthukumar M 2013. Kinetics of particle wrapping by a vesicle J. Chem. Phys 139 044908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vacha R, Martinez-Veracoechea FJ and Frenkel D 2011. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of nanoparticles of various shapes Nano Lett. 11 5391–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ehrlich M, Boll W, Oijen AV, Hariharan R, Chandran K, Nibert ML and Kirchhausen T 2004. Endocytosis by random initiation and stabilization of clathrin-coated pits Cell 118 591–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Loerke D, Mettlen M, Yarar D, Jaqaman K, Jaqaman H, Danuser G and Schmid SL 2009. Cargo and dynamin regulate clathrin-coated pit maturation PLoS Biol. 7 e57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Liu J, Sun Y, Drubin DG and Oster GF 2009. The mechanochemistry of endocytosis PLoS Biol. 7 e1000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Foret L and Sens P 2008. Kinetic regulation of coated vesicle secretion Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105 14763–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Walani N, Torres J and Agrawal A 2015. Endocytic proteins drive vesicle growth via instability in high membrane tension environment Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 423–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].den Otter WK and Briels WJ 2011. The generation of curved clathrin coats from flat plaques Traffic 12 1407–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cordella N, Lampo TJ, Melosh n and Spakowitz AJ 2015. Membrane indentation triggers clathrin lattice reorganization and fluidization Soft Matter 11 439–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Banerjee A, Berezhkovskii A and Nossal R 2012. Stochastic model of clathrin-coated pit assembly Biophys. J 102 2725–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Banerjee A, Berezhkovskii A and Nossal R 2012. Distributions of lifetime and maximum size of abortive clathrin-coated pits Phys. Rev. E 86 031907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Van Kampen n G 2011. Stochastic Processes in Physics and Chemistry (Amsterdam: North-Holland; ) [Google Scholar]

- [29].Redner S 2001. A Guide to First-Passage Processes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ) [Google Scholar]

- [30].Helfrich W 1973. Elastic properties of lipid bilayers: theory and possible experiments Z. Naturforsch. C 28 693–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Boal DH 2002. Mechanics of the Cell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ) [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zaremba S and Keen JH 1983. Assembly polypeptides from coated vesicles mediate reassembly of unique clathrin coats J. Cell Biol. 97 1339–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nossal R 2001. Energetics of clathrin basket assembly Traffic 2 138–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jackson LP, Kelly BT, McCoy AJ, Gaffry T, James LC, Collins BM, Honing S, Evans PR and Owen DJ 2010. A large-scale conformational change couples membrane recruitment to cargo binding in the AP2 clathrin adaptor complex. Cell 141 1220–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Parthasarathy R, Yu CH and Groves JT 2006. Curvature-modulated phase separation in lipid bilayer membranes Langmuir 22 5095–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bell GI, Dembo M and Bongrand P 1984. Cell adhesion. Competition between nonspecific repulsion and specific bonding Biophys. J 45 1051–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chithrani BD and Chan WCW 2007. Elucidating the mechanism of cellular uptake and removal of protein-coated gold nanoparticles of different sizes and shapes Nano Lett. 11 71542–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kirchhausen T 2009. Imaging endocytic clathrin structures in living cells Trends Cell Biol. 19 596–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Rejman J, Oberle V, Zuhorn IS and Hoekstra D 2004. Size-dependent internalization of particles via the pathways of clathrin- and caveolae-mediated endocytosis Biochem. J 377 159–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Oh J, Choi S, Lee G, Kim J and Choy J 2009. Inorganic metal hydroxide nanoparticles for targeted cellular uptake through clathrin-mediated endocytosis Chem. Asian J 4 67–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Chithrani BD, Ghazani AA and Chan WCW 2006. Nano Lett. 6 662–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Osaki F, Kanamori T, Sando S, Sera T and Yasuhiro A 2004. Determining the size and shape dependence of gold nanoparticle uptake into mammalian cells J. Am. Chem. Soc 126 6520–115161257 [Google Scholar]

- [43].Wang SH, Lee CW, Chiou A and Wei PK 2010. Size-dependent endocytosis of gold nanoparticles studied by three-dimensional mapping of plasmonic scattering images J. Nanobiotechnol 8 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lu F, Wu SH, Hung Y and Mou CY 2009. Size effect on cell uptake in well-suspended, uniform mesoporous silica nanoparticles Small 5 1408–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Albanese A and Chan WCW 2011. Effect of gold nanoparticle aggregation on cell uptake and toxicity. ACS Nano 5 5478–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Andar AU, Hood RR, Vreeland WN, Devoe DL and Swaan PW 2013. Microfluidic preparation of liposomes to determine particle size influence on cellular uptake mechanisms. Pharm. Res 31 401–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Veiga E and Cossart P 2005. Listeria hijacks the clathrin-dependent endocytic machinery to invade mammalian cells. Nature 7 894–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Liu AP, Aguet F, Danuser G and Schmid SL 2010. Local clustering of transferrin receptors promotes clathrin-coated pit initiation. J. Cell Biol. 191 1381–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Banerjee D, Liu AP, Voss nR, Schmid SL and Finn MG 2010. Multivalent display and receptor-mdiated endocytosis pf transferrin on virus-like particle Chem. Biochem 11 1273–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]