Abstract

Stem cells are generally believed to contain a small number of mitochondria, thus accounting for their glycolytic phenotype. We demonstrate here, however, that despite an indispensable glucose dependency, human dermal stem cells (hDSCs) contain very numerous mitochondria. Interestingly, these stem cells segregate into two distinct subpopulations. One exhibits high, the other low-mitochondrial membrane potentials (Δψm). We have made the same observations with mouse neural stem cells (mNSCs) which serve here as a complementary model to hDSCs. Strikingly, pharmacologic inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) increased the overall Δψm, decreased the dependency on glycolysis and led to formation of TUJ1 positive, electrophysiologically functional neuron-like cells in both mNSCs and hDSCs, even in the absence of any neuronal growth factors. Furthermore, of the two, it was the Δψm-high subpopulation which produced more mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and showed an enhanced neuronal differentiation capacity as compared to the Δψm-low subpopulation. These data suggest that the Δψm-low stem cells may function as the dormant stem cell population to sustain future neuronal differentiation by avoiding excessive ROS production. Thus, chemical modulation of PI3K activity, switching the metabotype of hDSCs to neurons, may have potential as an autologous transplantation strategy for neurodegenerative diseases.

Subject terms: Cell biology, Physiology

Introduction

Energy metabolism is fundamental for survival and normal function of living organisms. Similar to glycolysis-dependent cancer cells [1, 2], human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) and human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) are known to have a glycolytic phenotype to avoid excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thus protecting the cells from ROS-induced genomic damage [3–6]. In addition, a high level of type I phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling has been shown to ensure the glycolytic metabotype of stem cells to enhance biosynthesis-supporting metabolic activities, e.g., increased expression of nutrient transporters [3, 7–9]. Interestingly, a metabolic switch upon cellular differentiation, as well as during the reprogramming of fibroblasts to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has also been observed [10].

In contrast to generally consistent reports about the glycolytic phenotype of hPSCs and hESCs, descriptions about the different features of the mitochondria in these cells are conflicting. Earlier investigators had described a low mitochondrial content, whereas recent work has suggested a comparable mitochondrial content for stem cells and their differentiated counterparts [6, 11–13]. Interestingly, a very recent work demonstrated that the efflux of mitochondrial dye by hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) was the reason for the misleading conclusion that these cells had a low mitochondrial content [14]. Besides their prominent role in OXPHOS-coupled energy production, mitochondria are also directly involved in the determination of cell fate. Inhibiting mitochondrial function favors pluripotency and hinders differentiation [15], whereas stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis reduces pluripotency and promotes cell differentiation [16]. Moreover, mitochondrial maturation is needed for stem cell differentiation [10].

Among other adult stem cells, hDSCs are multipotent adult stem/progenitor cells in the dermis of the skin. They promise great therapeutic potential due to their easy accessibility and capability for differentiation to adipocytes, smooth muscle cells, as well as “neuron-like cells” [17–19]. They can be isolated from the dermis of human skin and cultured as floating spheres in serum-free medium using appropriate growth factors [20]. In contrast to other adult stem cells, such as HSCs and iPSCs, the metabolism of hDSCs is so far poorly characterized.

Here we show that hDSCs exhibit a high-mitochondrial content, but actually represent two subpopulations of cells, which can be characterized as having either a low or a high-mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm). These two subpopulations were also identified in mouse neural stem cells (mNSCs), which were subsequently studied as a complementary model for additional mechanistic studies. During neuronal differentiation, mNSCs consolidate into a single Δψm-high population exhibiting a continuous increase in Δψm. The two subpopulations of mNSCs do not differ in their expression of the stem cell marker Nestin nor in their proliferation status, but they do show differences in their potential for neuronal differentiation, i.e., the Δψm-high stem cells are prone to neuronal differentiation. Moreover, whereas PI3K activity normally declines during differentiation of mNSCs to neurons, a deliberate block of PI3K signaling in mNSCs or hDSCs actually induces an increased Δψm and a coincident reduction in the dependence on glycolysis, thereby inducing neuronal characteristics. Strikingly, the application of pharmacological inhibitors of PI3K in hDSCs induces the formation of electrophysiologically functional neurons in the absence of any neuronal growth factors. Our work emphasizes the activity, rather than the number of mitochondria as the leading cause for the glycolytic metabolism and suggests that the stem cell population with low Δψm represents the dormant stem cells needed to sustain a neuronal precursor pool. Furthermore, our data reveal the importance of metabolic control in cell fate determination and provide a simple alternative to current protocols for inducing neuronal differentiation of hDSCs, demonstrating that the inhibition of PI3K elicits a subsequent modulation of stem cell metabolism with the accompanying accession of neuronal phenotype.

Results

Despite having a glycolytic metabolism, hDSCs exhibit a high mitochondrial content and represent a heterogeneous cell population containing Δψm-low and Δψm-high subpopulations

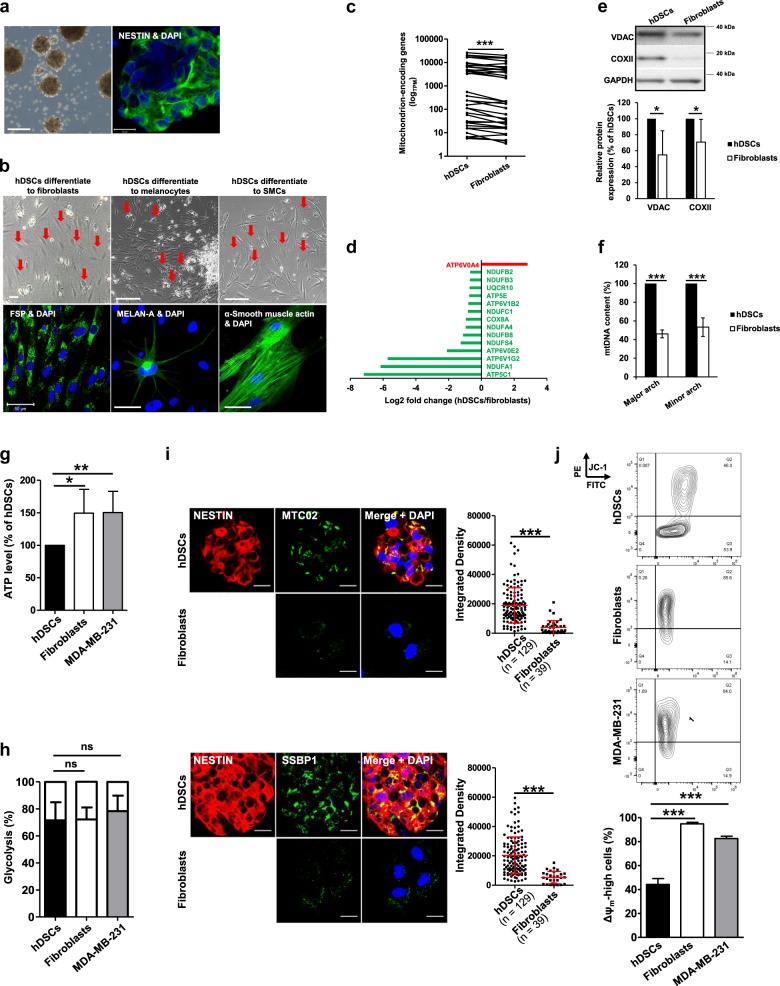

Given the apparent discrepancy in reports on the mitochondrial content in different types of stem cells [11, 13, 21], we decided to investigate this content and to characterize the metabolic behavior of hDSCs isolated from 30 healthy women and men with ages ranging from 23 to 86 years. hDSCs cultured in vitro formed floating spheres (Fig. 1a), which express the intermediate filament protein NESTIN (Fig. 1a) typical for neuroectodermal stem cells [17, 22]. The differentiation of hDSCs to fibroblasts, melanocytes, and smooth muscle cells (SMCs) was demonstrated by immunofluorescence staining of fibroblast surface protein (FSP), MELAN A, and smooth muscle actin (Fig. 1b), respectively, indicating the multipotency of hDSCs, as previously described [17, 22, 23].

Fig. 1.

hDSCs have a higher mitochondrial content than the autologous fibroblasts; hDSCs, however, represent a heterogeneous population with cells exhibiting either low or high Δψm. a hDSCs are characterized by sphere formation and the expression of the neuronal progenitor marker NESTIN. Representative images show the hDSC spheres (scale bar: 100 μm) and NESTIN expression of hDSCs (scale bars: 20 μm). b hDSCs were able to differentiate to FSP positive fibroblasts, MELAN-A positive melanocytes, as well as smooth muscle actin-positive smooth muscle cells (SMCs). Scale bars: 50 µm. c RNA of hDSCs and the autologous fibroblasts of 3 different donors was assessed with transcriptome analysis by next generation sequencing using the low input RNA-seq protocol (Clontech SMARTer). Among differentially expressed genes, 37 mitochondrion-encoded genes were found to be highly expressed in hDSCs (padjusted < 0.05). TPM transcripts per kilobase million. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed for statistical analysis. Detailed information about these genes can be found in Supplementary Table S1. d Fifteen genes involved in the mitochondrial ETC were significantly expressed differentially (p adjusted < 0.05) and are presented as the log2 fold change with hDSCs as compared to fibroblasts. Color code: red and green indicate genes which are more highly or less expressed, respectively, in hDSCs. e Proteins were isolated from hDSCs and the autologous fibroblasts for Western blotting to investigate the expression of mitochondrially localizing proteins. A representative Western blot result is shown at the top. The expression levels of these proteins were quantified using ImageJ software. Data shown are means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments with 3 different donors. A two-way paired ANOVA was performed (pANOVA cell type = 0.045). f DNA of hDSCs and the autologous fibroblasts were isolated and applied to real-time PCR to quantify the mtDNA content in these cells as described in the Materials and the Methods. Data shown are means ± SDs with 4 independent experiments of 4 different donors. A two-way paired ANOVA was performed (pANOVA cell type < 0.0001). g Cellular ATP contents were measured and normalized to protein amounts in these cells, then further normalized to the ATP content in hDSCs as described in the Materials and Methods. Data are shown as means ± SDs of >5 experiments using samples from 5 different donors. An unpaired one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed. h Glucose consumption and lactate production were measured and the bioenergetics of these cells was calculated as described in the Materials and Methods. Data shown are means ± SDs with 3 independent experiments of 3 different donors. An unpaired one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed. i hDSCs were co-stained with NESTIN and the mitochondrially localizing proteins, MTC02 or SSBP1. Images were prepared with the confocal microscope. Scale bars: 20 μm. The staining intensities of these proteins were quantified by ImageJ software and are represented by the integrated density (ID). Dots and squares in the graphs represent single cells of hDSCs or fibroblasts respectively. Data shown are means ± SDs with 3 independent experiments of 3 different donors. P values were obtained with Mann–Whitney test. j hDSCs and fibroblasts were stained with JC-1 to investigate the Δψm. Data shown are means ± SDs of 5 independent experiments with 5 different donors. An unpaired one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed

From the dermis of adult human skin, fibroblasts were also isolated and cultured in parallel to hDSCs to serve as an autologous differentiated counterpart. Transcriptome analysis of hDSCs and autologous fibroblasts revealed 37 mitochondrion-encoding genes, which show differential expression. We observed a general trend to upregulation of these genes in hDSCs as compared with fibroblasts (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table S1), suggesting a high-mitochondrial content in hDSCs. In addition, we also found that expression of genes encoding subunits of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) was lower in hDSCs as compared to fibroblasts (Fig. 1d and Fig. S1a), indicating a possibly diminished capability of hDSCs to perform OXPHOS.

In line with the RNAseq data, hDSCs expressed more mitochondrial proteins, such as the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) and complex IV/cytochrome C oxidase subunit II (CoxII) than autologous fibroblasts (Fig. 1e). Mitochondrial content was further examined by analyzing the amount of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) using quantitative real-time PCR as described [24, 25]. The mtDNA content per cell was larger in hDSCs than in fibroblasts (Fig. 1f), again indicating that hDSCs had a larger mitochondrial content.

When the bioenergetic dependency of the cells was characterized, as previously described [26], hDSCs showed a lower ATP level in comparison with the differentiated fibroblasts and exhibited a glycolytic metabotype, similar to the breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231, which was used as a control (Fig. 1g, h and Fig. S1b). Interestingly, despite their differentiated state, fibroblasts were still relatively dependent on glycolysis for their energy supply (Fig. 1h and Fig. S1b).

Morphologically, we observed condensed, globular, perinuclear mitochondria in hDSCs, evidenced by the immunofluorescence staining of two mitochondrial marker proteins: single strand DNA binding protein (SSBP1) [27] and the 60-kDa non-glycosylated protein component of mitochondria, MTC02 (Fig. S1c). In contrast, autologous fibroblasts showed mainly long, fibrillary mitochondria spreading along the cell axis, although some small globular structures were also visible at the cell extremities (Fig. S1c). Moreover, a more intense staining of these mitochondrial proteins was evident in hDSCs as compared with autologous fibroblasts (Fig. 1i, images). Quantification of the integrated densities (ID) of the mitochondrial staining in single cells again indicated that hDSCs had a larger mitochondrial content than fibroblasts (Fig. 1l, diagram). However, we noticed an obvious inter-cellular variance (Fig. 1l, diagram), suggesting a possible heterogeneity among cells within the hDSC spheres.

To study the Δψm, we stained the cells with the potential-dependent mitochondrial dye tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) that consists of green fluorescent monomers and forms red aggregates in polarized mitochondria. The red fluorescence of JC-1 aggregates can be detected in the PE channel of flow cytometry/fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) [21]. Intriguingly, the hDSCs were found to be made up of two subpopulations of cells with either high or low Δψm. This was in contrast to autologous fibroblasts and MDA-MB-231 cells, which showed rather homogenous cell populations with high Δψm (Fig. 1j). Culturing fibroblasts in hDSC medium did not lead to the formation of two separated subpopulations, despite obvious cell death and morphological changes (Fig. S2), indicating that culture medium with hDSCs is not the leading cause for the heterogeneous cell population of hDSCs.

In contrast to previous reports emphasizing the low content of mitochondria as the leading cause for the preponderantly glycolytic metabolism [28, 29], our data suggest that the reliance on glycolysis to meet the energy demands of stem cells is probably not owing to the quantity, but the quality of the mitochondria as reflected by the low Δψm.

mNSCs are glycolytic and have an abundant mitochondrial content, but segregate into two subpopulations with either low or high Δψm

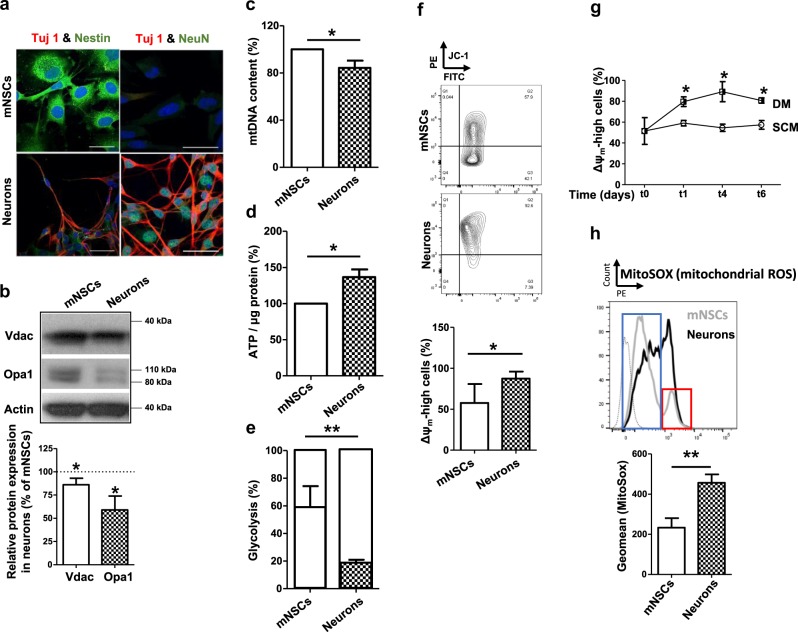

To study in more detail the two subpopulations of hDSCs with different Δψm, we employed a complementary model, the multipotent mNSC line C17.2 [30], which behaves similarly to hDSCs. C17.2 cells have proved to be a simple model, but complex enough to serve as convenient alternative to primary brain tissue cultures [31–35]. MNSCs expressed the stem cell and neuroectodermal marker Nestin and were able to differentiate to Tuj1 and NeuN (a neuronal nuclear antigen) double positive (Fig. 2a and Fig. S3a) and electrophysiologically functional neurons (Fig. S3b).

Fig. 2.

mNSCs contain a higher amount of mitochondria than differentiated neurons and are composed of two distinct cell populations with either low or high Δψm. a mNSCs express Nestin and are able to differentiate to Tuj1 and NeuN double positive neurons. Scale bars: 50 µm. b Proteins were isolated from mNSCs and their differentiated neurons and protein expression assessed with Western blotting. Quantification was done with ImageJ software by measuring the intensity of the bands detected. The relative expression of Vdac and Opa1 were normalized to expression in mNSCs (see diagram on the right). Data shown are means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed student t test was performed. c Total cellular DNA was isolated from mNSCs and their differentiated neurons, and analyzed with qPCR. Data shown are means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed student t test was performed. d ATP levels in mNSCs and differentiated neurons were measured as described in Materials and Methods. Data shown are means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test was performed. e Cellular bioenergetics of mNSCs and differentiated neurons were calculated by measuring glucose consumption and lactate production. Data shown are means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test was performed. f Mitochondrial polarization was detected by staining cells with JC-1 in mNSCs in comparison with differentiated neurons. Data shown are means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed student t test was performed. g Δψm was detected by staining cells with JC-1 during neuronal differentiation at different time points. DM differentiation medium. SCM: stem cell medium. Data shown are means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test was performed. h Mitochondrial ROS was measured by staining cells with MitoSox (5 µM) at 37 °C for 25 min and assessed by FACS. The geometric means are presented as means ± SDs of more than 3 independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test was performed. mNSCs show two subpopulations of cells exhibiting either high, or low mitochondrial ROS (red and blue rectangles)

Quantification of mitochondrion-localizing proteins, such as Vdac and optic atrophy 1 (Opa1) [36], and quantification of mtDNA indicated that mNSCs also had a large mitochondrial content similar to that observed in hDSCs (Fig. 2b, c and Fig. S3c). In contrast to the clear OXPHOS-dependence of differentiated neurons, mNSCs produced less ATP and were largely dependent on glycolysis for ATP production (Fig. 2d, e). Recalling our observation of a glycolytic metabotype for fibroblasts (Fig. 1h), it seems that differentiation does not necessarily determine the metabotype of the cells. As with hDSCs, mNSCs also exhibited two distinct subpopulations displaying either low or high Δψm, whereas differentiated neurons represented exclusively the Δψm-high phenotype (Fig. 2f). Interestingly, we observed a continuous increase in Δψm during neuronal differentiation of mNSCs (Fig. 2g). The slight decrease in Δψm-high cells on the 6th day of differentiation was probably due to a confluence-induced cell detachment (Fig. 2g). Furthermore, using MitoSox that detects mitochondrial superoxide [37], we observed that mNSCs produced less mitochondrial ROS compared to differentiated neurons (Fig. 2h), suggesting that the mitochondria in mNSCs were not as active as in neurons despite the large mitochondrial content. There were also two ROS subpopulations apparent within mNSCs, one exhibiting low, the other high mitochondrial ROS levels (Fig. 2h, blue and red rectangles).

In line with what we observed in hDSCs, mNSCs were found to exhibit a high mitochondrial content.

Δψm-high mNSCs show enhanced neuronal differentiation capacity

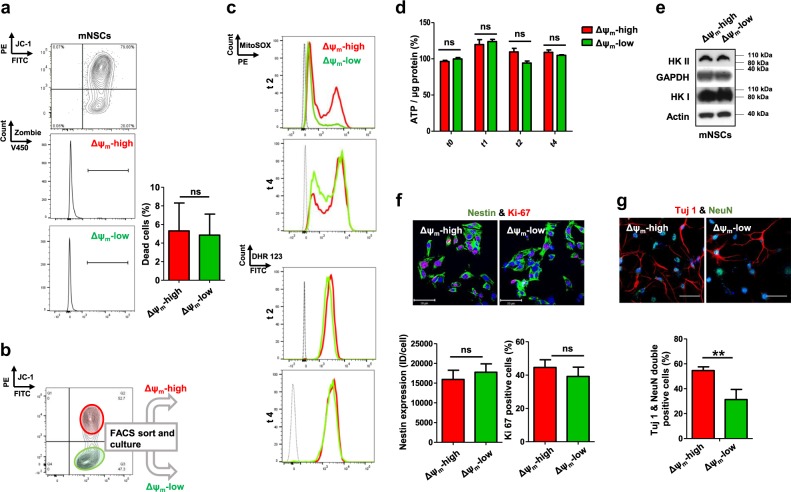

Since collapse of Δψm is often associated with cell death, we stained the cells with the amine-reactive fluorescent dye Zombie that accumulates in dead cells [38] in combination with JC-1 to see whether Δψm-low cells were dead. Cell death within the Δψm-low subpopulation was negligible (˂ 5 ± 5%) and was similar to that in the Δψm-high subpopulation (Fig. 3a). Thus, Δψm-low mNSCs were viable.

Fig. 3.

High-Δψm mNSCs produce more ROS and show enhanced neuronal differentiation capacity as compared to the low-Δψm mNSCs. a mNSCs were stained with JC-1 and Zombie. The Zombie positive cells (dead cells) were compared between the gated PE-positive (Δψm-high) and the gated PE-negative (Δψm-low) cell populations. Data shown are means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed student t test was performed. b mNSCs were FACS-sorted according to their Δψm and cultured in corresponding stem cell or neuronal differentiation medium. c Mitochondrial and intracellular levels of ROS were measured by staining the FACS-sorted cells (Δψm-low and Δψm-high) with MitoSox and DHR, respectively. d mNSCs were FACS-sorted according to Δψm and ATP content in the cells was measured over time. Data shown are means ± SDs of one representative experiment. e Cell lysates were extracted from the Δψm-low and Δψm-high mNSCs and applied for Western blot analysis. f FACS-sorted cells were stained for Nestin and Ki-67 and assessed by confocal microscopy. The intensity of Nestin was quantified as ID per cell and the percentage of Ki-67-positive cells was obtained by counting more than 200 cells. Scale bars: 50 µm. Data shown are means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test was performed. g FACS-sorted cells were cultured in neuronal differentiation medium for 7 days and the neuron markers, Tuj1 and NeuN were stained. Expression of these markers were observed with confocal microscopy and the double-positive cells (neurons) were quantified by evaluating more than 200 cells. Scale bars: 50 µm. Data shown are means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test was performed

To better characterize the two distinct cell populations within mNSCs, we FACS-sorted mNSCs according to their Δψm (Fig. 3b). Δψm-low and Δψm-high mNSCs were separately cultured in mNSC stem cell medium. In order to see whether two subpopulations would reestablish, we examined the mitochondrial ROS production as an indicator of active or polarized mitochondria to exclude the interference of residual JC-1 dye on the outcome. Two days after sorting, we observed that Δψm-high mNSCs produced more mitochondrial ROS than the Δψm-low (Fig. 3c) as expected. Interestingly, two distinct subpopulations with respect to mitochondrial ROS levels appeared again after culturing of Δψm-low mNSCs for 4 days in stem cell medium (Fig. 3c), suggesting a possible re-establishment of the Δψm-low and Δψm-high subpopulations previously observed. Using dihydrorhodamine 123 (DHR 123) that detects intracellular hydrogen peroxide and peroxynitrite [39], no difference between Δψm-low and Δψm-high mNSCs was observed (Fig. 3c).

The higher mitochondrial ROS levels in Δψm-high mNSCs suggested that this subpopulation might be more dependent on OXPHOS for energy production. However, the levels of ATP measured were comparable between the two subpopulations over time (Fig. 3d). In addition, the expression of proteins regulating glycolysis, such as hexokinase (HK) I, HK II, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) [40–42] did not differ (Fig. 3e), suggesting no metabolic differences between the two subpopulations of mNSCs. Furthermore, no difference was observed in the expression of Nestin and the proliferation marker, Ki-67, between Δψm-low and Δψm-high mNSCs (Fig. 3f). Intriguingly, however, the two subpopulations of mNSCs differed significantly in their capacity to differentiate, since the Δψm-high subpopulation was more prone to differentiate to neurons than the Δψm-low one evidenced by the larger fractions of Tuj1 and NeuN double positive neurons (Fig. 3g).

Pharmacologic inhibition of PI3K increases Δψm of mNSCs, inducing OXPHOS, thereby metabocopying the bioenergetic profile of neurons and, thus inducing neuronal differentiation

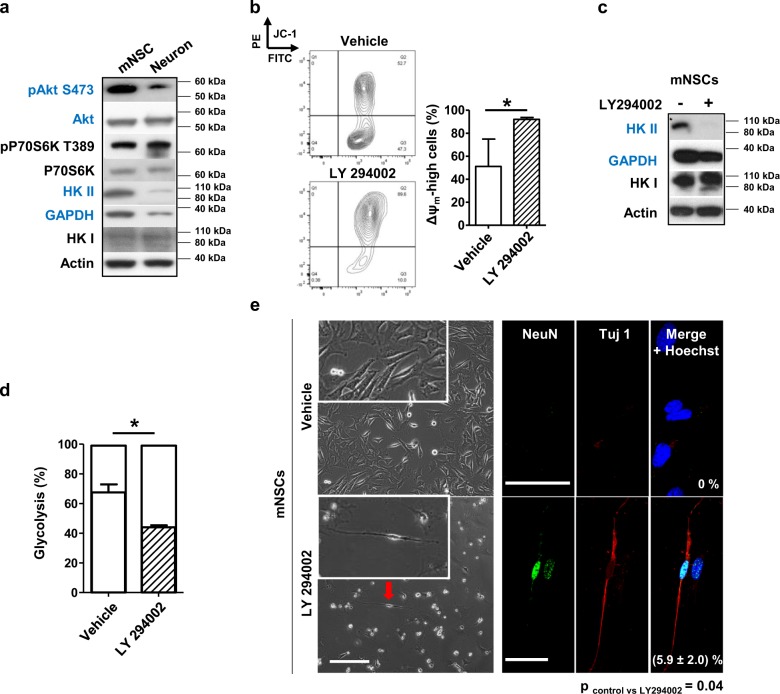

Mechanistically, we investigated the PI3K-mTOR signaling which plays an essential role in controlling the glycolysis required for pluripotency [3, 7]. Following growth factor-required neuronal differentiation, we observed a significant decrease in PI3K activity accompanied by a significant reduction in glycolysis-regulating proteins, e.g., HK II and GAPDH, in differentiated neurons compared with the undifferentiated mNSCs (Fig. 4a). To see whether an alteration just in PI3K signaling would also change the mitochondrial polarization, thereby altering the metabolism of mNSCs, we cultured mNSCs in a control medium (DMEM/F12), deprived of all neuronal growth factors, in the presence or absence of the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 for 4 days and examined their mitochondrial polarization. Intriguingly, we observed a significant increase in Δψm after mNSCs were treated with LY294002 (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

PI3K signaling is reduced in differentiated neurons as compared to mNSCs. Inhibition of PI3K increases the Δψm, diminishes the reliance on glycolysis and induces neuronal differentiation of mNSCs. a Total cell lysates of mNSCs and differentiated neurons were prepared for Western blot analysis. PI3K signaling and proteins associated with glycolysis were investigated. b mNSCs were cultured in stem cell medium in the presence or absence of LY294002 (1 µM) for 4 days and mitochondrial polarization was examined by JC-1 staining with FACS. The Δψm-high cell subpopulation was quantified and data are presented in the bar diagram on the right. Data shown are means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test was performed. c mNSCs were cultured in the presence or absence of LY294002 (1 µM) for 4 days. Cell lysates were collected for Western blot analysis. d mNSCs were cultured in stem cell medium in the presence or absence of LY294002 (1 µM) for 4 days. Glucose consumption and lactate production were measured and the bioenergetic profiles of the cells were calculated as described in the Materials and Methods. Data shown are means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed student t test was performed. e mNSCs were cultured in stem cell medium in the presence or absence of LY294002 (1 µM) for 4 days. Neuronal markers, NeuN and Tuj1 were stained and images obtained by confocal microscopy. NeuN and Tuj1 double positive neurons were calculated as a percentage of the total cell number by evaluating more than 5 images per condition of 3 independent experiments. An unpaired, two-tailed student t test was performed. Scale bars: 200 µm (phase contrast images) and 50 µm (confocal images)

To confirm that the observed increase in Δψm is specific for neuronal differentiation, we treated cells with the MEK inhibitor PD98059 that blocks neuronal differentiation [43, 44] or the ROCK inhibitor dimethylfasudil, which induces neuronal differentiation [45, 46]. Neuron-like morphology was not observed, nor was the increase in Δψm seen after treatment of mNSCs with PD98059 (Fig. S4a). In contrast, Tuj1 and NeuN double positive neuron-like cells appeared after ROCK was blocked (Fig. S4b). Interestingly, we also observed an increase in Δψm of mNSCs following inhibition of ROCK (Fig. S4b). These data suggested that increasing Δψm was not a unique feature of PI3K inhibition, rather a general event in neuronal differentiation.

Inhibition of PI3K decreased the expression of HK II and GAPDH (Fig. 4c), suggesting a likely reduction in glycolysis in treated mNSCs. Indeed, bioenergetic characterization showed a significantly reduced reliance on glycolysis in mNSCs once PI3K signaling was blocked (Fig. 4d), producing a metabotype resembling that of the differentiated neurons (Fig. 2e). Importantly, we observed Tuj1 and NeuN double positive neurons once mNSCs were treated with LY294002 in the absence of any neuronal growth factors (Fig. 4e).

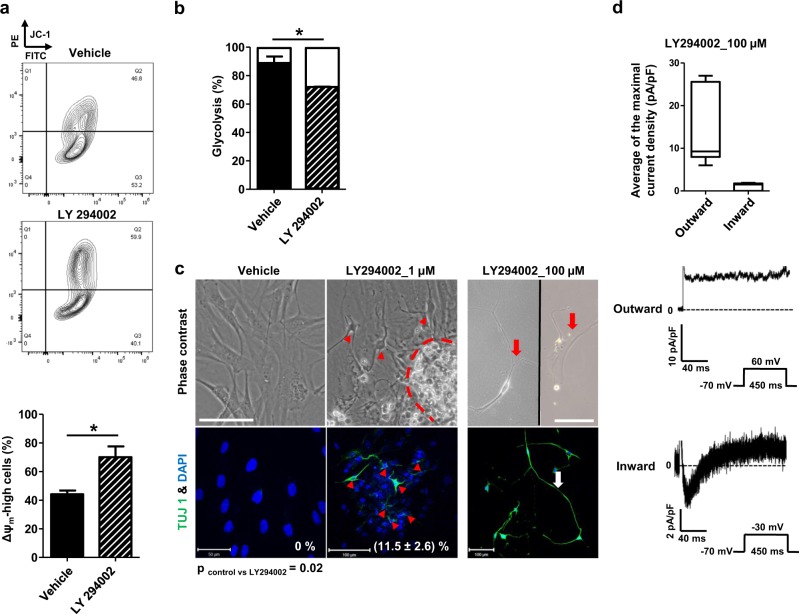

Pharmacologic inhibition of PI3K increases Δψm, reduces the reliance on glycolysis, and induces differentiation of hDSCs to electrophysiologically functional neurons

To reproduce in hDSCs our finding that inhibition of PI3K induced neuronal differentiation of mNSCs, we treated hDSCs with LY294002 and cultured the cells in DMEM/10% FCS medium lacking any neuronal growth factors for 7 days, replacing culture media containing the drug every second day. Similar to what we observed in mNSCs, LY294002 increased the Δψm (Fig. 5a) and reduced the dependency on glycolysis (Fig. 5b). Applying 1 μM LY294002 to hDSCs allowed the observation of TUJ1-positive cells with dendrite-like protrusions growing out of hDSC spheres overlying a layer of flattened cells (Fig. 5c; red arrowheads). After increasing the drug concentration to 100 μM, only cells with elongated cell shape and bipolar or multipolar protrusions remained in the culture without any residual contamination with underlying flattened cells (Fig. 5c, red arrows). In addition, the neurite-like protrusions further elongated and developing cell-to-cell contacts became visible (Fig. 5c, white arrow). Most importantly, we detected inward and outward currents in these cells in whole-cell patch clamp experiments (Fig. 5d). TUJ1-positive, electrophysiologically functional neuron-like cells were also observed when hDSCs were treated with other PI3K inhibitors, including 3-methyladenine and wortmannin (Fig. S5), confirming that the inhibition of PI3K facilitates neuronal differentiation.

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of PI3K increases Δψm, reduces the reliance on glycolysis and facilitates neuronal differentiation of hDSCs. a hDSCs were cultured in the presence or absence of LY294002 (1 µM) for 4 days and JC-1 staining was performed to monitor Δψm. Data shown are means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments with 3 different donors. An unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test was performed. b The bioenergetics of hDSCs cultured in hDSC stem cell medium in the presence or absence of LY294002 (1 µM) for 4 days were analyzed as described in the Materials and methods. Data shown are means ± SDs of 3 independent experiments with 3 different donors. An unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test was performed. c hDSCs were cultured in DMEM/10% FCS in the presence or absence of 1 or 100 µM LY294002 for 7 days. Neuron-like cells (red arrowheads) growing out of the hDSC sphere (dashed line) were observed by light microscopy (upper images; scale bars: 100 µm). TUJ1-positive neurons (red arrowheads) were calculated as percentage of the total cell number by evaluating more than 5 images per condition in 3 independent experiments (lower images; scale bars: 50 µm). An unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test was performed. Developing neuron-like cells following treatment with 100 µM LY294002 exhibited long dendrites (red and white arrows). d hDSCs treated with 100 µM of LY294002 were employed for patch clamp experiments. Averages for the maximal current density (pA/pF) were obtained by whole-cell currents in voltage-clamp mode; cells were held at −70 mV; step depolarization from −90 mV to +60 mV at 10-mV intervals was delivered. Representative traces of outward and inward currents are shown. Data were obtained from 3 independent experiments with 3 different donors

Discussion

Our work underlines the reality that stem cells maintain a low level of mitochondrial ROS in order to reduce oxidative stress that is detrimental for the lifespan of these cells [5]. This is probably not owing to a low amount of mitochondria, but rather the “inactive state” of their mitochondria resulting from a low Δψm. It should be noted that the terms “Δψm-low” and “Δψm-high” stem cells have been reported previously, e.g., in mouse ESCs by gating a homogeneous cell population, but without carrying out a physical separation according to Δψm [47]. However, there have been conflicting reports with respect to the definition of which population is one-step further along towards differentiation. For instance, it has been shown in stem-like cells that high-quality (high Δψm) mitochondria are required for maintaining the stem cell pool, suggesting that differentiation is initiated from those with low Δψm [48]. On the other hand, a high Δψm is beneficial for neuronal differentiation, because an abundant supply of ATP is required for mitochondrial transport in neurons [49, 50]. Furthermore, mouse HSCs with low mitochondrial activity maintain long-term self-renewal activity and those with high mitochondrial activity are more committed to differentiation [51]. However, owing to technical limitations, in particular FACS sorting followed by culturing hDSCs with particular Δψm properties, the mechanistic study and characterization of the two cell populations could not be performed with hDSCs. Future study aiming at elucidating the role of heterogeneity among hDSCs would give a clear picture of the above-mentioned discrepancies, i.e., which population is one-step further towards neuronal differentiation. A possible mechanism for maintaining Δψm low cells would be a high level of uncoupling protein 2 in stem cells that reduces Δψm by pumping protons from mitochondrial intermembrane space to the matrix [6].

But why is the increase in Δψm required within the process of neuronal differentiation? The increase in Δψm likely reflects an improvement in mitochondrial fitness, which might well be a prerequisite for the upcoming metabolic switch from glycolysis to OXPHOS, triggering an exit from the stem cell state. Indeed, the two subpopulations of stem cells did not differ in cellular metabolism as evidenced by comparable ATP levels and the HK II and GAPDH expression, supporting the assumption that increased mitochondrial polarization occurs prior to the metabolic switch.

Mechanistically, we have recognized that inhibition of PI3K in both hDSCs and mNSCs caused an increased Δψm, simultaneously decreasing the dependency on glycolysis and inducing neuronal differentiation. Given the important role of autophagy in stemness and differentiation of adult stem cells [20], as well as the involvement of PI3K-mTORC1 in regulating autophagy [52], it is possible that alterations in autophagic activity play a role during neuronal differentiation of mNSCs and hDSCs. Preliminary data, however, suggest that rapamycin, an mTOR inhibitor and an activator of autophagy, also promoted neuronal differentiation in our system (data not shown). It has been reported that prolonged administration of rapamycin does not block mTORC1, acting rather on mTORC2 in certain cell types and tissues [53, 54]. Interestingly, blocking ROCK that acts distal to mTORC2 also induced neuronal differentiation in mNSCs, suggesting that mTORC2 is central in this case. Clearly, the exact signaling pathway required for increasing Δψm and the subsequent decrease in the dependence on glycolysis in stem cells remains to be investigated.

Whether the knowledge obtained from our study could be extrapolated to other stem cell types remains uncertain. A large mitochondrial content has been recently shown in HSCs. However, segregation of two subpopulations of cells with different Δψm was not described in this work [14]. It is therefore possible that the segregation of the two stem cell populations with different Δψm, which we report here is a distinct feature of neuroectoderm-derived stem cells, such as mNSCs and hDSCs. In any case, our study on the role of mitochondrial polarization and the metabolic switch by PI3K inhibition in the neuronal differentiation of neuroectoderm-derived stem cells helps to understand the essential role of cellular metabolism in stem cell biology. Moreover, the essential role of mitochondria in stem cell differentiation rather than energy generation is underlined through this work. Finally, the successful differentiation of hDSCs to neurons using PI3K inhibitors emphasizes the importance of using hDSCs as an easily accessible source of adult stem cell types in translational medicine.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

hDSCs and human dermal fibroblasts were isolated and cultured from normal adult skin obtained from body contouring procedures performed in the Clinic for Plastic Surgery, University Hospital of Bern, with the consent of patients using protocols as previously described [17, 20, 22] with our own modifications. The skin samples originated from breast, medial thigh, or lower abdomen resection specimens of healthy individuals aged from 23 to 86 and were harvested under sterile conditions in the operating theater.

Skin pieces were cut free of fat and blood vessels and washed intensively with PBS supplemented with 2% penicillin-streptomycin (P/S) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The clean skin without fat and blood was then cut into small pieces, incubated in Petri dishes filled with 2.5 mg/ml of Dispase II (Roche) at room temperature (RT) overnight. Next day, the Dispase II-treated skin pieces were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h and then washed with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 1% P/S to remove Dispase. The epidermis was separated from the dermis using forceps. The remaining dermis was washed with DMEM, cut into small pieces (1–3 mm) and incubated with 0.25% trypsin at 37 °C for 2 h with gentle agitation. The digested dermis was then passed through strainers (100–70 µm, Millipore) after inactivating trypsin with fetal calf serum (FCS). The strained cell suspension was washed once with DMEM. Cells were counted and cultured either in DMEM with 10% FCS and 1% P/S (fibroblast medium) to obtain fibroblasts or in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with FGF2 (40 ng/ml), EGF (20 ng/ml), B27 (1:50), P/S (1%), as well as fungizone (1 ug/ml) and gentamycin (10 µg/ml) (all obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific) to expand hDSCs (hDSC medium).

hDSCs were first cultured in coated flasks for 1 week to remove the contaminated fibroblasts from the starting culture, then transferred to ultra-low attachment plates (Corning) to grow spheres in “3D”. Fresh growth factors were added every 3 days into the conditioned culture medium of hDSCs.

mNSCs were cultured in DMEM/10% FCS/1% P/S/5% horse serum/fungizone (1:2000) [55]. To differentiate mNSCs to neurons, cells were first seeded in stem cell medium for 2 days to allow an optimal attachment of mNSCs. After that, stem cell medium was replaced with the neuronal differentiation medium consisting of DMEM/F12/2.5% FCS/1% P/S/B27 (1:50). The differentiation medium was changed to 1:1 conditioned medium: fresh medium every 3–4 days. The differentiation process took 6–12 days.

MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FCS and 1% P/S.

Immunofluorescence

hDSCs were first spun down onto glass slides; fibroblasts, mNSCs and their differentiated neurons were first seeded on coverslips in a 24-well plate allowing them to adhere before staining. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at RT for 10 min and washed once with PBS. Cells were permeabilized with 10% saponin for 5 min followed by acetone treatment at −20 °C for 10 min. After washing the slides with PBS, cells were blocked with normal goat serum at RT for 1 h. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in the blocking solution at 4 °C overnight. The primary antibodies were: rabbit anti-NESTIN (1:200; Millipore), mouse anti-Nestin (1:200; Gene Tex), rabbit anti-SSBP1 (1:100; Novus Biologicals), mouse-anti-MTC02 (1:100; Abcam), mouse anti-Ki-67 (1: 500; Dako), mouse anti-MELAN A (1:100; Dako) and mouse anti-smooth muscle actin (Abcam). For experiments where Mitotracker Orange was co-stained with NESTIN, cells were first incubated with Mitotracker Orange (1:10,000; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C for 20 min; thereafter, we proceeded as described above. After incubation with primary antibodies, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 488, goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 563, goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 555 and goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at RT for 1 h, protected from the light. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and slides were mounted with fluorescence mounting medium (Dako), and subsequently analyzed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (LSM 510).

Quantification of the mitochondrial content was performed using ImageJ software by automatically calculating the integrated density (ID) of the selected mitochondrial staining areas after manually selecting the cells. The calculated values of ID of cells per image from 3 independent experiments were plotted.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total cellular DNA samples of cells were isolated using a commercially available kit as described by the manufacture (Macherey-Nagel). The mtDNA content of mNSCs and differentiated neurons was quantified, as previously described [56] using the following primers: mouse mitochondrial DNA region, 5′-CTA GAA ACC CCG AAA CCA AA-3′ and 5′-CCA GCT ATC ACC AAG CTC GT-3′, mouse genomic nuclear DNA control region (β2M gene), 5′-ATG GGA AGC CGA ACA TAC TG -3′ and 5′-CAG TCT CAG TGG GGG TGA AT -3′.

The mtDNA content of hDSCs and human fibroblasts was quantified as previously described using primer pairs specific for the major or minor arch of the mitochondrial DNA and normalized to the genomic region of β2M gene [25, 57]. The following primers were used: major arch: 5′-CTG TTC CCC AAC CTT TTC CT-3′ and 5′- CCA TGA TTG TGA GGG GTA GG -3′; minor arch: 5′- CTA AAT AGC CCA CAC GTT CCC-3′ and 5′-AGA GCT CCC GTG AGT GGT TA-3′ and β2M: 5′-GCT GGG TAG CTC TAA ACA ATG TAT TCA-3′ and 5′- CCA TGT ACT AAC AAA TGT CTA AAA TGG T-3′. The qPCR reaction was performed using the CFX Connect detection system (Bio-Rad).

Western blotting

Cells were washed with cold PBS and lysed with lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 50 mM sodium fluoride, and 200 µM sodium orthovanadate. Shortly before beginning with the lysis, a protease inhibitor cocktail and 100 µM PMSF (Sigma Aldrich) were freshly added to the lysis buffer. The cell pellet was incubated in lysis buffer on ice with frequent vortexing for 15 min. Thereafter, the supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. The protein concentration was measured with the BCA Protein Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Thirty micrograms of protein of each sample were loaded on NuPage gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes (Immobilion-P; Millipore). Membranes were incubated with a blocking buffer containing Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.4) with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) and 5% non-fat dry milk at RT for 1 h and then incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. The primary antibodies were: rabbit anti-pAKT S473, rabbit anti-AKT, rabbit anti-pP70S6K T389, P70S6K, rabbit anti-HK II, rabbit anti-HK I (all 1:1000, Cell Signaling) rabbit anti-VDAC (1:1000; Millipore), mouse anti-complex IV subunit II (COX II) (1:1000; Thermo Fisher Scientific), mouse anti-MTC02 (1:1000; Abcam), rabbit anti-Actin (1:1000; Cytoskeleton) and mouse anti-GAPDH (1:10000; Chemicon International, Inc.). Membranes were then incubated with the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) in TBST with 5% non-fat dry milk at RT for 1 h and developed using an ECL approach (ECL-kit, Amersham).

Measurement of cellular ATP content

Cells, 3000/microplate well of fibroblasts and 5000/microplate well of mNSCs or MDA-MB-231, were seeded 2 d before the experiment to allow optimal attachment. Approximately 10 hDSC spheres were seeded on the day of the experiment after dissociation with a 0.45 mm syringe. Cellular ATP was measured as described [26] with the CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega) according to the protocol provided. The values of the relative luminescence units were normalized to the amount of protein.

Analysis of the metabolic phenotype by measuring glucose consumption and lactate production

Calculation of the bioenergetic phenotype of cells was performed as previously described with slight modifications [26]. Briefly, the corresponding cell culture media were changed 24 h after seeding cells in a 24-well plate. Cells were either left untreated or treated with 100 ng/ml of oligomycin for 6 h. The cell culture media was then collected and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm at 4 °C for 5 min; the remaining cells in the well were used to prepare lysates. The hDSCs were spun down in a tube, the supernatant collected as culture media and the remaining cell pellet was used as the cell lysate. The collected media were then deproteinized with 1 M perchloric acid, thereafter neutralized with 2 M potassium hydroxide until the pH reached ~6.5–8. The amounts of glucose and lactate present in these deproteinized samples were then measured using the Glucose Hexokinase Kit and the Lactate Assay Kit II, respectively, according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer (Sigma Aldrich). The calculated amount of glucose or lactate was normalized to the total protein values for the cells.

The contribution of glycolysis and OXPHOS to cellular bioenergetics was calculated, as described [26]. Briefly, glycolysis (%) = (lactate control/lactate oligomycin) × 100% and OXPHOS (%) = 100%−glycolysis (%).

Measurement of Δψm by JC-1 staining

The procedure was adapted as described [58] with slight modifications. Briefly, dissociated hDSCs and other cells (200,000/condition) were incubated with 2 µM of JC-1 in DMEM medium with 1% P/S (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37 °C for 20 min. After washing with DMEM, cells were resuspended in this washing medium and analyzed by FACS (FACSverse, BD).

Quantification and statistical analysis

The integrated density of the protein of interest in a single cell was measured with ImageJ software from the pixel intensities of the respective channel.

Data were presented as means ± SDs of at least 3 independent experiments from multiple donors (for hDSCs and human fibroblasts). The individual statistics are described in the corresponding figure legends and were adjusted for multiple testing if applicable. Differences between means were considered significant at the level of p < 0.05.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Stefano Di Santo, Department of Neurosurgery, Research Unit, University of Bern, Switzerland, for his helpful discussions and technical assistance. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (310030_166473 to HUS), Swiss Cancer league (KFS-3703-08-2015 to HUS), and European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant No. 642295; MEL-PLEX). Images were acquired on equipment supported by the Microscopy Imaging Centre of the University of Bern.

Author contributions:

Conceptualization, HL and HUS; Methodology and Investigation, HL, ZYH, SLA, MFT, JSR, and SS; Materials and Reagents, RO, HRW, and HUS; Data Analysis and Interpretation, HL, ZYH, SLA, MFT, JSR, and HUS; Writing-Review and Editing, HL and HUS; Supervision, Project Administration and Funding Acquisition, HUS.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by M Piacentini.

These authors contributed equally: Simon Leonhard April, Marcel Philipp Trefny.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41418-018-0182-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Potter M, Newport E, Morten KJ. The Warburg effect: 80 years on. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016;44:1499–505. doi: 10.1042/BST20160094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warburg O, Wind F, Negelein E. The metabolism of tumors in the body. J Gen Physiol. 1927;8:519–30. doi: 10.1085/jgp.8.6.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J, Nuebel E, Daley GQ, Koehler CM, Teitell MA. Metabolic regulation in pluripotent stem cells during reprogramming and self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:589–95. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varum S, Momcilovic O, Castro C, Ben-Yehudah A, Ramalho-Santos J, Navara CS. Enhancement of human embryonic stem cell pluripotency through inhibition of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Stem Cell Res. 2009;3:142–56. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prigione A, Fauler B, Lurz R, Lehrach H, Adjaye J. The senescence-related mitochondrial/oxidative stress pathway is repressed in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:721–33. doi: 10.1002/stem.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Khvorostov I, Hong JS, Oktay Y, Vergnes L, Nuebel E, et al. UCP2 regulates energy metabolism and differentiation potential of human pluripotent stem cells. EMBO J. 2011;30:4860–73. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, Daikhin E, Nissim I, Yudkoff M, Wehrli S, et al. Beyond aerobic glycolysis: transformed cells can engage in glutamine metabolism that exceeds the requirement for protein and nucleotide synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19345–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wieman HL, Wofford JA, Rathmell JC. Cytokine stimulation promotes glucose uptake via phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt regulation of Glut1 activity and trafficking. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1437–46. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e06-07-0593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu RH, Pelicano H, Zhang H, Giles FJ, Keating MJ, Huang P. Synergistic effect of targeting mTOR by rapamycin and depleting ATP by inhibition of glycolysis in lymphoma and leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2005;19:2153–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folmes CDL, Nelson TJ, Martinez-Fernandez A, Arrell DK, Lindor JZ, Dzeja PP, et al. Somatic oxidative bioenergetics transitions into pluripotency-dependent glycolysis to facilitate nuclear reprogramming. Cell Metab. 2011;14:264–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Facucho-Oliveira JM, Alderson J, Spikings EC, Egginton S, St John JC. Mitochondrial DNA replication during differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:4025–34. doi: 10.1242/jcs.016972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.St John JC, Ramalho-Santos J, Gray HL, Petrosko P, Rawe VY, Navara CS, et al. The expression of mitochondrial DNA transcription factors during early cardiomyocyte in vitro differentiation from human embryonic stem cells. Cloning Stem Cells. 2005;7:141–53. doi: 10.1089/clo.2005.7.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birket MJ, Orr AL, Gerencser AA, Madden DT, Vitelli C, Swistowski A, et al. A reduction in ATP demand and mitochondrial activity with neural differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:348–58. doi: 10.1242/jcs.072272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Almeida MJ, Luchsinger LL, Corrigan DJ, Williams LJ, Snoeck HW. Dye-independent methods reveal elevated mitochondrial mass in hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:725–9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Folmes CD, Terzic A. Energy metabolism in the acquisition and maintenance of stemness. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;52:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prowse AB, Chong F, Elliott DA, Elefanty AG, Stanley EG, Gray PP, et al. Analysis of mitochondrial function and localisation during human embryonic stem cell differentiation in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toma JG, McKenzie IA, Bagli D, Miller FD. Isolation and characterization of multipotent skin-derived precursors from human skin. Stem Cells. 2005;23:727–37. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandes KJ, Toma JG, Miller FD. Multipotent skin-derived precursors: adult neural crest-related precursors with therapeutic potential. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:185–98. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biernaskie JA, McKenzie IA, Toma JG, Miller FD. Isolation of skin-derived precursors (SKPs) and differentiation and enrichment of their Schwann cell progeny. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2803–12. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salemi S, Yousefi S, Constantinescu MA, Fey MF, Simon HU. Autophagy is required for self-renewal and differentiation of adult human stem cells. Cell Res. 2012;22:432–5. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.St John JC, Amaral A, Bowles E, Oliveira JF, Lloyd R, Freitas M, et al. The analysis of mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA in human embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;331:347–74. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-046-4:347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toma JG, Akhavan M, Fernandes KJ, Barnabe-Heider F, Sadikot A, Kaplan DR, et al. Isolation of multipotent adult stem cells from the dermis of mammalian skin. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:778–84. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinbach SK, El-Mounayri O, DaCosta RS, Frontini MJ, Nong Z, Maeda A, et al. Directed differentiation of skin-derived precursors into functional vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2938–48. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.232975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu W, Zhu H, Gu M, Luo Q, Ding J, Yao Y, et al. DHTKD1 is essential for mitochondrial biogenesis and function maintenance. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:3587–92. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malik AN, Shahni R, Rodriguez-de-Ledesma A, Laftah A, Cunningham P. Mitochondrial DNA as a non-invasive biomarker: accurate quantification using real time quantitative PCR without co-amplification of pseudogenes and dilution bias. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;412:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hao W, Chang CP, Tsao CC, Xu J. Oligomycin-induced bioenergetic adaptation in cancer cells with heterogeneous bioenergetic organization. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12647–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.084194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bogenhagen DF, Rousseau D, Burke S. The layered structure of human mitochondrial DNA nucleoids. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3665–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708444200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varum S, Rodrigues AS, Moura MB, Momcilovic O, Easley CAt, Ramalho-Santos J, et al. Energy metabolism in human pluripotent stem cells and their differentiated counterparts. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e20914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wanet A, Arnould T, Najimi M, Renard P. Connecting mitochondria, metabolism, and stem cell fate. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24:1957–71. doi: 10.1089/scd.2015.0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mi R, Luo Y, Cai J, Limke TL, Rao MS, Hoke A. Immortalized neural stem cells differ from nonimmortalized cortical neurospheres and cerebellar granule cell progenitors. Exp Neurol. 2005;194:301–19. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu P, Jones LL, Snyder EY, Tuszynski MH. Neural stem cells constitutively secrete neurotrophic factors and promote extensive host axonal growth after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2003;181:115–29. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riess P, Zhang C, Saatman KE, Laurer HL, Longhi LG, Raghupathi R, et al. Transplanted neural stem cells survive, differentiate, and improve neurological motor function after experimental traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:1043–52. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200210000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang M, Stull ND, Berk MA, Snyder EY, Iacovitti L. Neural stem cells spontaneously express dopaminergic traits after transplantation into the intact or 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rat. Exp Neurol. 2002;177:50–60. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lundqvist J, El Andaloussi-Lilja J, Svensson C, Gustafsson Dorfh H, Forsby A. Optimisation of culture conditions for differentiation of C17.2 neural stem cells to be used for in vitro toxicity tests. Toxicol Vitr. 2013;27:1565–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akerud P, Canals JM, Snyder EY, Arenas E. Neuroprotection through delivery of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor by neural stem cells in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8108–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08108.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belenguer P, Pellegrini L. The dynamin GTPase OPA1: more than mitochondria? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:176–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mailloux RJ. Teaching the fundamentals of electron transfer reactions in mitochondria and the production and detection of reactive oxygen species. Redox Biol. 2015;4:381–98. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vom Berg J, Vrohlings M, Haller S, Haimovici A, Kulig P, Sledzinska A, et al. Intratumoral IL-12 combined with CTLA-4 blockade elicits T cell-mediated glioma rejection. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2803–11. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Djiadeu P, Azzouz D, Khan MA, Kotra LP, Sweezey N, Palaniyar N. Ultraviolet irradiation increases green fluorescence of dihydrorhodamine (DHR) 123: false-positive results for reactive oxygen species generation. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2017;5:e00303. doi: 10.1002/prp2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petrucci D, Cesare P, Colafarina S. Mitochondria, hexokinase and pyruvate kinase isozymes in the aerobic glycolysis of tumor cells. Ital J Biochem. 1997;46:131–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pedersen PL. Warburg, me and Hexokinase 2: Multiple discoveries of key molecular events underlying one of cancers’ most common phenotypes, the “Warburg Effect”, i.e., elevated glycolysis in the presence of oxygen. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2007;39:211–22. doi: 10.1007/s10863-007-9094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolf A, Agnihotri S, Micallef J, Mukherjee J, Sabha N, Cairns R, et al. Hexokinase 2 is a key mediator of aerobic glycolysis and promotes tumor growth in human glioblastoma multiforme. J Exp Med. 2011;208:313–26. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Z, Theus MH, Wei L. Role of ERK 1/2 signaling in neuronal differentiation of cultured embryonic stem cells. Dev Growth Differ. 2006;48:513–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2006.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y, Yang F, Fu Y, Huang X, Wang W, Jiang X, et al. Spatial phosphoprotein profiling reveals a compartmentalized extracellular signal-regulated kinase switch governing neurite growth and retraction. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18190–201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.236133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lingor P, Teusch N, Schwarz K, Mueller R, Mack H, Bahr M, et al. Inhibition of Rho kinase (ROCK) increases neurite outgrowth on chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan in vitro and axonal regeneration in the adult optic nerve in vivo. J Neurochem. 2007;103:181–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamishibahara Y, Kawaguchi H, Shimizu N. Promotion of mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation by Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632. Neurosci Lett. 2014;579:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schieke SM, Ma M, Cao L, McCoy JP, Jr., Liu C, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism modulates differentiation and teratoma formation capacity in mouse embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28506–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802763200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katajisto P, Dohla J, Chaffer CL, Pentinmikko N, Marjanovic N, Iqbal S, et al. Stem cells. Asymmetric apportioning aged mitochondria daughter cells is required stemness. Science. 2015;348:340–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1260384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Esteves AR, Gozes I, Cardoso SM. The rescue of microtubule-dependent traffic recovers mitochondrial function in Parkinson’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:7–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacAskill AF, Kittler JT. Control of mitochondrial transport and localization in neurons. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:102–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vannini N, Girotra M, Naveiras O, Nikitin G, Campos V, Giger S, et al. Specification of haematopoietic stem cell fate via modulation of mitochondrial activity. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Liu H, He Z, Simon HU. Targeting autophagy as a potential therapeutic approach for melanoma therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23:352–60. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, et al. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell. 2006;22:159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schreiber KH, Ortiz D, Academia EC, Anies AC, Liao CY, Kennedy BK. Rapamycin-mediated mTORC2 inhibition is determined by the relative expression of FK506-binding proteins. Aging Cell. 2015;14:265–73. doi: 10.1111/acel.12313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Snyder EY, Deitcher DL, Walsh C, Arnold-Aldea S, Hartwieg EA, Cepko CL. Multipotent neural cell lines can engraft and participate in development of mouse cerebellum. Cell. 1992;68:33–51. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90204-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Malik AN, Czajka A, Cunningham P. Accurate quantification of mouse mitochondrial DNA without co-amplification of nuclear mitochondrial insertion sequences. Mitochondrion. 2016;29:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phillips NR, Sprouse ML, Roby RK. Simultaneous quantification of mitochondrial DNA copy number and deletion ratio: a multiplex real-time PCR assay. Sci Rep. 2014;4:3887. doi: 10.1038/srep03887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jang SY, Kang HT, Hwang ES. Nicotinamide-induced mitophagy: event mediated by high NAD+/NADH ratio and SIRT1 protein activation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:19304–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.363747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.