Abstract

An HIV diagnosis may be associated with severe emotional and psychological distress, which can contribute to delays in care or poor self-management. Few studies have explored the emotional, psychological, and psychosocial impacts of an HIV diagnosis on women in low-resource settings. We conducted in-depth interviews with 30 women living with HIV in the Dominican Republic. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using the biographical disruption framework. Three disruption phases emerged (impacts of a diagnosis, postdiagnosis turning points, and integration). Nearly all respondents described the news as deeply distressful and feelings of depression and loss of self-worth were common. Several reported struggling with the decision to disclose—worrying about stigma. Postdiagnosis turning points consisted of a focus on survival and motherhood; social support (family members, friends, HIV community) promoted integration. The findings suggest a need for psychological resources and social support interventions to mitigate the negative impacts of an HIV diagnosis.

Keywords: Dominican Republic, diagnosis, biographical disruption, qualitative research, women living with HIV/AIDS

Introduction

An HIV-positive diagnosis can be a life-altering event with detrimental emotional and psychological effects. Research suggests that an HIV diagnosis can act as a traumatic stressor and is associated with mental distress and trauma.1,2 Those newly diagnosed may experience emotional distress, fear of HIV status disclosure, and anxiety about HIV-related stigma and discrimination.3-5 These impacts are of particular concern if they contribute to delays in seeking appropriate health-care services or impede appropriate self-management and adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART).6-10

Increased global access to ART and advances in treatment has transformed how individuals respond to an HIV-positive diagnosis. In the early years of the epidemic, individuals may have faced significantly direr impacts due to scarce to nonexistent treatment options and high levels of external stigma. Today, people with HIV are living longer and the condition has transitioned from an acute to chronic illness for many given the widespread availability of treatment.4,11-13 According to the biographical disruption framework, individuals diagnosed with a chronic illness may be confronted with a rupture in their sense of identity and in various domains of their life.11,14-18 Identity is an important element of psychological functioning for people living with HIV (PLHIV) and may influence decisions about treatment and self-management.13 Individuals can accept or reject aspects of the illness (and treatment) as they reshape their biography and sense of self and identity.4,19 HIV is also a stigmatized illness,13 and the stigma can be particularly disruptive if it leads to the disintegration of social relationships or loss of economic opportunities. To the best of our knowledge, all prior work that has employed the biographical disruption framework to study the experience of living with HIV/AIDS has been conducted in Europe,17,18,20-22 Africa,4,12,23 and the United States.11,15,16 Furthermore, limited qualitative research has been conducted with Caribbean people to examine the emotional, psychological, and psychosocial impacts after an HIV-positive diagnosis and related coping strategies in the Caribbean24,25 and elsewhere.18,26

What Do We Already Know about This Topic?

HIV is a stigmatized illness and individuals diagnosed with HIV may experience emotional distress, fear of HIV status disclosure, and anxiety about HIV-related stigma, which can contribute to delays in care and/or impede treatment and self-management.

How Does Your Research Contribute to the Field?

In-depth interviews with a sample of urban-dwelling women living with HIV in the Dominican Republic reveal 3 critical disruption phases after an HIV diagnosis (impacts of a diagnosis, postdiagnosis turning points, and integration). Fear of disclosure and stigma-related anxiety were key psychosocial barriers to treatment and appropriate self-management, whereas survival and motherhood identities served as motivators to engage in care.

What Are Your Research’s Implications toward Theory, Practice, or Policy?

Newly diagnosed individuals in low-resource countries need psychological resources and social support interventions to help newly diagnosed individuals mitigate the negative impacts following an HIV diagnosis.

How PLHIV reshape their identities may impact their decisions to engage in treatment or appropriate self-management. Certain types of coping strategies after an HIV diagnosis are associated with differential mental health outcomes and well-being. For instance, maladaptive coping behaviors (eg, extended rumination and avoidance) are associated with worse mental health outcomes.27 According to a meta-analysis, women living with HIV (WLHIV) seem to experience greater harm from maladaptive coping than men.28 How women experience and cope with an HIV diagnosis in a low-resource environment is not well understood, particularly in the context of their own narratives and daily circumstances.12 Women are also generally less likely to disclose their HIV status compared to men,29,30 potentially making them more vulnerable to isolation. Understanding how women process and cope with HIV as a chronic illness is valuable toward understanding their use of resources and disease self-management.14,16,20

Additional research is also needed to better understand coping mechanisms and their impact on women’s health, which can be compounded by poor social and economic environments that include high levels of stigma, gender inequality, and poverty. A qualitative study in rural South Africa explored how WLHIV (n = 19) coped with the disease; results emphasize the importance of taking into consideration the role of social context of emotional distress in resource-poor communities. For mothers, the distress caused by these social conditions resulted from the impact on their children (ie, not being able to feed their children) instead of concerns about their own personal health,31 thus highlighting the importance of examining how perceived roles and social context intersect when examining coping motivations and behaviors.

To address existing gaps in the literature, this qualitative study explores the various ways in which an HIV-positive diagnosis impacts the identity and behavior of urban-dwelling women in low-resource communities in the Dominican Republic (DR). The burden of HIV in the Caribbean region is relatively high, and the region has the second highest HIV prevalence rate in the world after sub-Saharan Africa. Among Spanish-speaking countries in the region, the DR has the highest general HIV prevalence rate, estimated at 1.0% among individuals aged 15 to 49 years (approximately 69 000 people).32 Reported HIV transmission is mostly driven by unprotected heterosexual sex and the infection rate has been disproportionately increasing among women.33 More than half of adults living with HIV in the DR and the Caribbean are women.34 In addition to exploring the impacts of an HIV diagnosis on identity and behavior among WLHIV, this study investigates how women cope with the diagnosis and self-manage their condition. Understanding these dimensions can lead to the development and integration of culturally appropriate behavioral and social support interventions to improve self-management behaviors, quality of life, and HIV outcomes.

Method

A qualitative approach was used to explore the impact of an HIV diagnosis on WLHIV in the DR and coping strategies after diagnosis. We conducted in-depth, semistructured interviews with a purposive sample of WLHIV (N = 30).

Setting

Eligible participants resided in 1 of 3 cities with medium to high HIV prevalence rates in the southeast part of the country (Santo Domingo, San Pedro de Macorís, and La Romana). Three clinics agreed to participate as the recruitment sites for the study (ie, 1 clinic per city). The first clinic is a government-operated HIV clinic with a longstanding history of providing care for PLHIV (beginning in the early 1990s). The second clinic is faith based and operates as part of the Health Ministry of an Episcopal Church. This clinic provides primary and specialty care to indigent populations and integrated HIV/AIDS services for PLHIV, including behavioral health services. The third clinic is a nonprofit health-care organization that primarily provides primary and specialty care to PLHIV.

Recruitment

Local study staff recruited females from HIV clinics located in the study cities. Eligibility criteria included being a minimum of 18 years or older, being a registered patient in an HIV clinic, residing in an urban or periurban area in 1 of the 3 selected cities, and reporting recent food insecurity. Food insecurity was assessed using 2 questions from the validated Latin American and Caribbean Food Security Scale/Escala Latinoamericana y Caribeña de Seguridad Alimentaria,35,36 namely, (1) In the past 3 months, was there a time when you were worried that you would not have enough food to eat because of a lack of money or other resources? (2) In the past 3 months, has your family been unable to eat healthy and nutritious food because of a lack of money or other resources? HIV clinic staff referred female patients on select recruitment days to learn about the study from a trained interviewer. The interviewer explained the purpose of the study and asked screening questions to confirm eligibility. Interviewers provided eligible women with additional information about the study and obtained verbal consent.

Data Collection

Two trained, local field workers conducted in-person, semistructured interviews in Spanish (range: 60-90 minutes). Both interviewers were women with considerable professional experience working with PLHIV and HIV programs. A total of 30 eligible women (10 per site) were recruited and consented to be interviewed and recorded. The average age of participants was 38 years (range: 20-56 years). All the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Table 1 lists the key interview themes and select questions.

Table 1.

Key Interview Themes and Sample Questions.

| Theme | Sample Question |

|---|---|

| HIV diagnosis and related impacts |

|

| Economic security |

|

| HIV treatment and related behaviors |

|

| Mental health |

|

Data Analysis

Spanish language transcripts were uploaded to Dedoose, a qualitative data management software program. During fieldwork, the interviewers and research team regularly debriefed and discussed the field notes to assess whether data saturation had been attained for the key themes and to document emergent findings. We employed content analysis methods37-39 and an inductive approach40,41 to identify principal and emergent themes. The full codebook is described in detail elsewhere.42 Key subcategories relevant to this article included mental health effects of a diagnosis, negative sentiments, positive sentiments, mental health, HIV diagnosis, HIV disclosure to others, external stigma, internal stigma, social support, economic changes related to HIV, ART adherence, and non-ART treatment adherence (eg, clinical visits).

Two researchers, fluent in Spanish, independently coded the transcripts using a systematic coding approach. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus. Detailed coding summaries were extracted for relevant categories and iteratively revised by the analysis team. A third researcher, the lead author, further examined how an HIV diagnosis disrupted respondents’ identity and lives using a 5-component biographical disruption model of HIV/AIDS identity (diagnosis, postdiagnosis turning point, immersion, postimmersion turning point, and integration)15 adapted from Bury14 to analyze relevant content within the summaries. Preliminary findings were discussed and interpreted with collaborators and stakeholders at various times to reduce the threat of researcher bias.43 For example, the lead author was not involved in data collection and reviewed the results with collaborators in the DR to corroborate and confirm the findings. Illustrative quotes were selected and translated to English for inclusion in this article.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

The study’s protocols and materials were approved by the RAND Corporation Human Subjects Protection Committee (2008-0345-AM02) and a local institutional review board (Consejo Nacional de Bioética en Salud del Ministerio de Salud Pública) in the DR. All participants provided verbal informed consent prior to enrollment in the study. The consent was audio-recorded in the presence of a trained research staff member. Written informed consent was not pursued as an option since obtaining documentation with participants’ names could pose a risk to protecting the confidentiality of the WLHIV.

Results

Nearly all respondents described an HIV-seropositive diagnosis as a highly stressful and emotionally impactful event. Several spoke of the life-changing nature of the diagnosis and severe psychological and emotional distress, which was often compounded by psychosocial stressors (eg, perceived HIV-related stigma, fear of disclosure). Nearly a quarter were diagnosed while pregnant, piquing mothers’ concerns about mother-to-child HIV transmission.

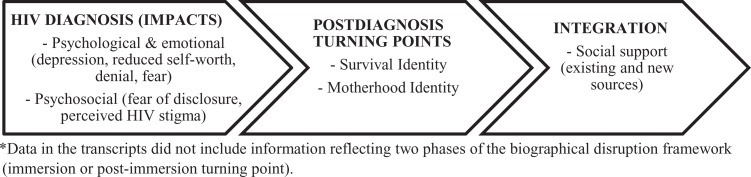

Three of the 5 biographical disruption phases were identified based on the data (ie, impacts of an HIV diagnosis, postdiagnosis turning points, and integration). Figure 1 shows the different biographical disruption phases and key findings from this study, which are explained in detail below.

Figure 1.

Impacts of an HIV diagnosis and biographical disruption phases for WLHIV in the Dominican Republic (N = 30). WLHIV indicates women living with HIV.

Perceived Psychological and Emotional Impacts of a Diagnosis

Most respondents described the immediate impacts of an HIV-positive diagnosis as being psychological and emotional. Many were deeply shocked and distressed upon receiving the news. The following quote illustrates the grief and disconnect several women expressed,

I sobbed so much. I left there and arrived home late. It was because I didn’t go home right away. I left [the clinic] and just walked and did not even pick up the car. I just walked, my thoughts were so far away.

For many, the diagnosis carried considerable mental anguish and immediate shock. One respondent said, “Look, at once this mind of mine was transformed in a way I can’t describe. I don’t know how to describe it. It was as though my spirit left, like they killed me.” Another felt as though she were in a foreign country when she was told and desired to leave the clinic:

Well, I went in my mind very far away for about 5 minutes, it was as though I was in Egypt. It wasn’t until a woman began to knock on the door that I could…well I couldn’t. I just wanted to stand up and go so far away and disappear.

Diagnosis during Pregnancy and Postpartum

Nearly a quarter of the women reported being diagnosed while receiving prenatal care or after giving birth. Being informed during pregnancy or postpartum was described as highly traumatic. One woman spoke about her feelings of depression:

At that moment, I felt extremely depressed. Oh yes, I felt so depressed and as if I was wandering on the street and headed somewhere very far away! I would go to the park and just sit there thinking, “My God, what will happen to me and my child.” I also thought about giving up my child for adoption.

Another said she felt “extremely traumatized” because she was pregnant when she was notified she was HIV positive and the news altered how those around her responded to the pregnancy. In her case, a health-care provider and her mother encouraged her to abort, which led to additional stress and anxiety. A third, who was diagnosed 20 years prior to the interview, said she was informed after her child was born and coped with alcohol:

They sent me to take all of these tests and then they told me…it was after the caesarian. I took all of the test results and there they said, “Do you know that you have HIV?” I didn’t know I had HIV. Then they explained, “HIV is AIDS” and I went crazy. I became so ill, so, so ill. It was horrible. I became an alcoholic.

In a few cases, women said a health-care provider tried to alleviate their anxiety by informing them of treatment options. A respondent said she was separated from her child after giving birth and told she could not breastfeed her child, however, “the psychologist told me they realized I had this [condition], but that it would not kill me and there was medication for it.” The respondent said she felt assured simply knowing HIV treatment existed.

Feelings of Depression and Reduced Self-Worth

Several respondents said their lives completely changed postdiagnosis. A respondent described this change by saying, “in every way, you live life differently.” Another felt she “died” on the day she was diagnosed. Many alluded to the disempowering effect of the diagnosis on their sense of identity and used phrases denoting reduced self-worth or self-efficacy, as in the case of the following respondent: “I felt like I was worthless. I said, ‘ah, well, I am no longer worth anything because I have HIV.’”

A deep sense of sadness and grief extended into a depressed state for some. They used the term “depressed” to characterize their emotional state postdiagnosis, whereas others described indicators of depression, including constant crying and expressions of grief, loss of appetite, social isolation, and reduced interest in regular activities. Among these respondents, some attributed these symptoms to the distressing nature of the diagnosis, as illustrated by the following quote, “Nothing was appetizing. Perhaps the news really hurt me emotionally.” Others ceased engaging in regular daily activities and isolated themselves. One woman shared, “Well, I stayed quiet and fell into depression. I didn’t shower, and I didn’t do anything.” For some, the diagnosis was conflated with questions about their moral condition, which contributed to extended grief and feelings of shame, “When I learned I was HIV positive, I wept so much. I wept every day and asked God, ‘why is this happening to me since I am not a bad person?’”

Denial and Fear

A few reported being in denial after learning of their diagnosis and coped by behaving as though they were not HIV positive. These women reported delaying care until they internalized and accepted the news or began to experience symptoms. The following quote reflects the narrative of a woman who delayed care until she experienced symptoms: “I began to cry and said I would not return [to the clinic] to get tested. I left and sobbed so much. Afterward, when I got worse and my CD4 was 24, then I decided to return to repeat the exam and it came out positive.” Another was in denial for nearly 4 years before she began treatment: “I did not want to accept it. I rejected it for 4 years, ha! Four years. And I said, ‘Do not talk to me about that.’ I went 4 years with a positive result without medication, nothing.”

Perceived Psychosocial Impacts of a Diagnosis: Fear of Disclosure and Perceived Stigma

Nearly all women expressed fear of disclosure and anxiety about HIV-related stigma and rejection as key concerns. They said they were either previously fearful or remained concerned about disclosing their status to members of their social network due to potential HIV-related stigma and rejection from family members, friends, and/or employers.

For some, fear of disclosure stemmed from a belief that others would not keep the information confidential or they would be rejected. Several believed they would be treated differently: “The changes occur when you have this illness and the family distances themselves. Your family treats you differently.” One said she felt she could not tell “her family or anyone because they talk too much” and constantly worried about rejection. Some reported feeling depressed, ashamed, or conflicted by not disclosing the diagnosis with family members. Others informed select individuals but continued to worry they would be rejected if others knew: “I was very careful not to let others know because I did not want to be rejected. I told my mother and my two children, but we all kept it a secret. It never left my house.”

Concern about disclosure and perceived stigma was described as a barrier to self-management and treatment adherence. One said she went to great lengths to avoid going to a local clinic out of fear that someone would find out she was HIV positive:

It was very difficult. I decided that I was not going to come here [the HIV clinic]. I would not go to places where I was referred since there were probably a lot of people and perhaps someone from my neighborhood would see me, and I would become a laughing stock.

Several women communicated a desire for others to view HIV as a “normal condition” that was akin to other chronic illnesses that were not stigmatized.

I wish it didn’t have this taboo…I wish we believed it was just a health condition like any other. It doesn’t matter how we got it, the important thing is that we have it. We should see this like something normal, like high blood pressure.

Postdiagnosis Turning Points

Most participants came to view an HIV diagnosis as a chronic illness requiring consistent treatment (ie, ART and regular clinical visits) over time and reported engaging in a variety of positive coping strategies after being diagnosed. Survival and motherhood identities emerged as facilitators to engaging in self-management and treatment.

Survival Identity

Most came to terms with their HIV-positive diagnosis and said they eventually accepted the diagnosis as a lifelong chronic illness that was a part of their new identity. For many, an HIV-positive diagnosis was seen as an ongoing ordeal and perceived as a constant struggle for survival. Survival was identified as a strong motivator for engaging in self-care and daily activities after being diagnosed: “But when you get this, it’s like something comes over you and you lose your pride in order to survive.” Several mentioned the importance of survival to overcome the initial phase of shock and emotional distress:

When you are first diagnosed, you stop eating and you cease all normal activities. You believe the world is going to overwhelm you. You believe you no longer have a future. But it’s a lie. You have your entire life in front of you and you have to survive. You have to survive HIV.

Survival appeared to motivate many to reengage in regular activities and cope with a new reality. Several described eating as a means of surviving and said eating—particularly eating healthily—was a necessary part of warding off illness and even death. One woman summarized this viewpoint, “You have to go through with your treatments and you also have to eat well. You have to eat healthy food to survive.” Some said they consumed food to “survive the virus” and to avoid “getting sicker.” Another spoke of the decreased enjoyment she received from food after being diagnosed and said she would now eat to survive: “Before I would eat, I would eat a lot. But not anymore. Now I only eat because it’s necessary.”

The survival lens persisted for many as motivation for taking care of oneself and extended beyond health to these other domains. One simply said, “I survive however I can,” referring to temporary jobs or seeking alternative sources of food to address issues stemming from poverty.

According to respondents, socioeconomic barriers posed difficulties to survival. Several said surviving with HIV was more difficult due to economic and material resource constraints, which made it challenging to adhere to appropriate self-management and recommended dietary guidelines.

Motherhood Identity

Motherhood was also frequently mentioned as a motivator for engaging in positive coping mechanisms and adhering to treatment. A woman who was tested and diagnosed with HIV during pregnancy said the negative effect of the diagnosis was buffered by her pregnancy, which provided her with a sense of purpose and a reason to live:

To tell you the truth, I don’t know what would have happened to me had I not been pregnant with my son. When they told me the news, they actually left me here by myself in the room until the afternoon so that I could take in the news. But to tell you the truth, I honestly don’t know if I would have come back had I not been pregnant.

Having children motivated some to pursue treatment. One woman began treatment at an HIV clinic due to her desire to see her children mature and thrive: “I said I would go [to the clinic] because I have my children and I want them to study and to grow old. I want to see them grow up so I have to finish my treatment. I am not going to give up.”

Integration: Mobilizing Support and Resources through Social Networks

Positive factors that facilitated WLHIV’s transition from a state of initial shock and fear to integration of the diagnosis into their sense of self and identity consisted of support from existing social networks and networks of PLHIV. Women mentioned the importance of family members and friends who provided support. Emotional support by family members and friends was the most common type of support mentioned. One woman found her older sister’s words of support and encouragement particularly helpful after disclosing her status, “she gave me hope. Yes, she said ‘don’t think about that. There are people who suffer through illnesses worse than that and you are not the only one. There are many just like you.’” Another was emotionally buoyed by words from a friend who counseled her: “She hugged me and then said that although I had [the virus], she was not going to abandon me. She said I had to take care of myself. She told me I had to use a condom when I had sex.”

A small number said their family members and friends encouraged them to seek treatment and facilitated self-management by reminding or accompanying them to clinical appointments. A woman’s teenage daughter frequently reminded her mother to take her medication and encouraged her to attend her appointments while helping her with household chores and duties. In another case, a woman’s husband regularly reminded her to take medication and attend clinical appointments.

A few also mentioned the economic and material support provided by members of their social networks, such as housing, food, and money. However, this type of support was rare, likely due to conditions of poverty or economic scarcity.

Positive Impact of Connecting with Networks of PLHIV

New social networks involving the broader community of PLHIV were described as comforting and valuable sources of empowerment. Perceived benefits of getting involved with HIV support groups included an increased sense of purpose, empowerment, and motivation to engage in positive coping strategies. Five spoke about the importance of interacting with other PLHIV and their involvement as attendees or counselors in the group. They said HIV support groups were instrumental in helping them cope by providing support and encouragement:

The support groups have helped me so much. I used to think that I was the one and only person with this condition but when I began to see how many people had HIV, I said “I have to fight for my life and not give up.”

This woman said she had learned from members of the support group and was now in a place to help newly diagnosed persons. Another said she greatly benefited from attending HIV support groups, “and my life changed when I started to attend those support groups.” A third worked as a counselor to encourage screening and treatment in high-risk neighborhoods and said the work resulted in “many beautiful memories,” which further motivated her to take care of herself.

Discussion

This study explored the impacts of an HIV diagnosis on Dominican WLHIV. The immediate psychological and emotional impacts of an HIV-positive diagnosis were described as severe, leading to feelings of depression and reduced self-worth. According to the accounts, several women were vulnerable to depression after their diagnosis and reported self-isolating or disengaging from regular activities (eg, eating). A few were in denial and nonadherent to treatment until they were symptomatic. Denial is also referred to as a state of submersion in other studies where PLHIV attempt to not think about their diagnosis.8,26,44,45 The tension to disclose their condition to family members was particularly straining, particularly for those who primarily relied on kin for social support. Further, self-management of the condition was challenging due to perceived stigma and lack of disclosure. Several reported coping with this stigma by masking their condition/treatment with family members, friends, and coworkers.

Studies on initial responses to an HIV diagnosis similarly identified shock, emotional distress, and withdrawal as reactions to an HIV-positive diagnosis in a variety of settings.4,11,12,18,19,26,44,46,47 For some, the immediate shock and distress may potentially reduce a newly diagnosed individual’s capacity to comprehend and absorb what they are being told and information about their treatment.48 The emotional burden and feelings of stress associated with living with and managing a chronic illness, including concerns about access to healthy food and treatment, can exacerbate perceptions of poor health and further propagate stress as found in a study with adults diagnosed with diabetes in the DR.49 Further research is needed to examine how HIV diagnoses are delivered50 to inform the development of culturally appropriate patient–physician communication interventions related to HIV notification in low-resource settings. For women who are diagnosed during pregnancy or postpartum, it may be valuable for providers to emphasize the effectiveness of ART in preventing mother-to-child transmission to reduce trauma.

Similar to prior research, we found a high level of fear of disclosure and anxiety about HIV-related stigma and rejection postdiagnosis.8,24,26,51-53 Another study with WLHIV in the DR referred to decisions related to disclosure as “HIV disclosure control” and referred to it as a stigma coping strategy.25 Fear of disclosure and stigma-related anxiety are important psychosocial factors that may act as barriers to treatment and appropriate self-management for stigmatized chronic illnesses such as HIV. The need to address such concerns is even more critical in this era of treatment as prevention.54,55 According to a meta-analysis examining the effects between stressors and coping mechanisms on behavioral health outcomes among WLHIV in the United States, those who cope by avoidance or social isolation are at risk for more severe mental health outcomes.28 Disclosure is an important component of how PLHIV manage their identity4,11,12,19 and may play an important role in facilitating the process of acceptance and support before seeking care.19 A systematic review found disclosure to a spouse was associated with improved treatment outcomes (ie, initiation, adherence, and retention in care) among pregnant and postpartum WLHIV.8 Worry associated with disclosure and lack of disclosure suggest a need to further explore disclosure processes and decision-making among WLHIV in Latin America and the Caribbean since few related studies have been conducted in these regions.25,29,56

Our study is the first to use the biographical disruption framework to assess how PLHIV integrate their diagnosis into their identity in the Caribbean. Interestingly, the same 3 biographical disruption components that emerged in our study (diagnosis, postdiagnosis turning point, and integration) were also identified in a study with PLHIV in the United States after medication was made readily available.11 In our study with WLHIV in a low-resource setting, important postdiagnosis turning points were characterized by a focus on survival and motherhood to overcome distress and engage in self-management strategies. The will to survive and motherhood may have encouraged respondents to engage in positive reappraisal, thus motivating them to initiate treatment and self-management. Although motherhood and concern for their children’s well-being has previously been mentioned as a motivator to engage in care,20,26,56 this is the first to identify a survival identity and its context as part of a postdiagnosis turning point during a period of adjustment. Future studies may wish to explore the potential interrelatedness of these identities (ie, survival for a child’s sake) postdiagnosis among expectant or new mothers diagnosed with HIV.20

The findings suggest a need for psychological and psychosocial resources for recently diagnosed WLHIV in the DR. Integrating HIV counseling or a behavioral health provider into primary care or the HIV care continuum could help facilitate positive coping strategies for newly diagnosed patients57 and help reduce the stigma of mental illness by focusing on prevention. This strategy can be particularly beneficial for women, given the prevalence of domestic abuse in the country58 and for WLHIV.42 However, this approach can be challenging in countries with limited behavioral health services47 such as the DR, which faces a shortage of behavioral health service providers and has insufficient funding for these services.58,59

In light of the limited availability of mental health services, nonclinical strategies may be of use.60 In our study, important facilitators to integration included receiving support from friends and family and, for some, the broader community of PLHIV. These sources of social support have also been identified in other studies4,5,11,15,25,47,51 and may help alleviate psychological distress postdiagnosis.61 According to women’s accounts, most support was provided in the form of encouragement and reminders from family members and friends to engage in treatment, and those who participated in HIV support groups reported feeling a sense of empowerment and improved self-efficacy. Support and counseling groups for newly diagnosed individuals is a potential mechanism to increase social support levels for WLHIV and also provide timely information and instructions regarding appropriate treatment and self-management. Peer health workers used in resource-limited settings have been found to be effective in reducing stigma, improving retention in care, and improving quality and outcomes of HIV care.60,62-66 In Nairobi, community health workers who serve PLHIV in specific regions are also an important source of social capital and support.4 These groups can help mitigate the trauma, distress, and social isolation associated with an HIV diagnosis. Our findings suggest interventions may be needed to help WLHIV in the DR develop new sources of social support to improve adherence and quality-of-life outcomes.

Limitations

The study has several limitations, including the use of a convenience sample. The sample may only reflect experiences of WLHIV who access ART and who are more adherent to treatment since they were recruited from HIV clinics. As such, we may have excluded the perspectives of those who have not linked to HIV care, attend infrequently, or have abandoned care altogether.18

Another limitation is that we did not ask respondents when they had been diagnosed. Future studies should collect this information as there is some evidence that long-term diagnosed respondents (ie, PLHIV diagnosed >10 years) use different coping strategies than those recently diagnosed.26

Conclusion

An HIV-positive diagnosis can be a life-altering event with harmful psychological and psychosocial effects. Emotional distress, fear about disclosure, and anxiety about HIV-related stigma and discrimination from others were common and of concern given that these factors have been found to be barriers to self-management and ART adherence. This study uses the biographical disruption framework to conceptualize these impacts and coping strategies after an HIV diagnosis. Key stages of biographical disruption consisted of the diagnosis, postdiagnosis turning points, and integration.

WLHIV in the DR may benefit from counseling and support services to improve their treatment adherence and quality of life. Culturally appropriate behavioral and social support interventions, such as mental health services and HIV peer support groups, are needed in low-resource settings to mitigate the negative impacts of an HIV-positive diagnosis that impede ART adherence, appropriate self-management, and quality of life among PLHIV. Continued efforts to reduce HIV-related stigma more broadly are also needed for improved outcomes across the HIV care continuum.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants who gave so generously of their time as well as Sergio Terrero and Ramón Acevedo for overall coordination of local data collection.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Financial support from the World Food Programme (WFP) for local data collection. For analysis and manuscript preparation, the authors received partial or full salary support from the following institutions: the National Institute of Mental Health or NIMH (grant number R34MH110325, Dr Derose), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or AHRQ (grant number T32HS00046, Dr Payán, Dr Palar), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or NIDDK (grant number K01 DK107335, Dr Palar). The contents of the manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of WFP, NIMH, AHRQ, or NIDDK.

ORCID iD: Denise D. Payán  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3236-862X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3236-862X

References

- 1. Nightingale VR, Sher TG, Hansen NB. The impact of receiving an HIV diagnosis and cognitive processing on psychological distress and posttraumatic growth. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(4):452–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martin L, Kagee A. Lifetime and HIV-related PTSD among persons recently diagnosed with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(1):125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Whetten-Goldstein K, Nguyen TQ. You’re the First One I’ve Told: New Faces of HIV in the South. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wekesa E, Coast E. Living with HIV postdiagnosis: a qualitative study of the experiences of Nairobi slum residents. BMJ Open. 2013;3(5):e002399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liamputtong P, Haritavorn N, Kiatying-Angsulee N. HIV and AIDS, stigma and AIDS support groups: perspectives from women living with HIV and AIDS in central Thailand. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(6):862–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hall BJ, Sou KL, Beanland R, et al. Barriers and facilitators to interventions improving retention in HIV care: a qualitative evidence meta-synthesis. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(6):1755–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mellins CA, Kang E, Leu CS, Havens JF, Chesney MA. Longitudinal study of mental health and psychosocial predictors of medical treatment adherence in mothers living with HIV disease. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2003;17(8):407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hodgson I, Plummer ML, Konopka SN, et al. A systematic review of individual and contextual factors affecting ART initiation, adherence, and retention for HIV-infected pregnant and postpartum women. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sweeney SM, Vanable PA. The association of HIV-related stigma to HIV medication adherence: a systematic review and synthesis of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(1):29–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ostermann J, Pence B, Whetten K, et al. HIV serostatus disclosure in the treatment cascade: evidence from Northern Tanzania. AIDS Care. 2015;27(suppl 1):59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baumgartner LM, David KN. Accepting being poz: the incorporation of the HIV identity into the self. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(12):1730–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wouters E, De Wet K. Women’s experience of HIV as a chronic illness in South Africa: hard-earned lives, biographical disruption and moral career. Sociol Health Illn. 2016;38(4):521–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Swendeman D, Ingram BL, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Common elements in self-management of HIV and other chronic illnesses: an integrative framework. AIDS Care. 2009;21(10):1321–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bury M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol Health Illn. 1982;4(2):167–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baumgartner LM. The incorporation of the HIV/AIDS identity into the self over time. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(7):919–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ciambrone D. Illness and other assaults on self: the relative impact of HIV/AIDS on women’s lives. Sociol Health Illn. 2001;23(4):517–540. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alexias G, Savvakis M, Stratopoulou I. Embodiment and biographical disruption in people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). AIDS Care. 2016;28(5):585–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Anderson M, Elam G, Gerver S, Solarin I, Fenton K, Easterbrook P. “It took a piece of me”: initial responses to a positive HIV diagnosis by Caribbean people in the UK. AIDS Care. 2010;22(12):1493–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Horter S, Thabede Z, Dlamini V, et al. “Life is so easy on ART, once you accept it”: acceptance, denial and linkage to HIV care in Shiselweni, Swaziland. Soc Sci Med. 2017;176:52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wilson S. ‘When you have children, you’re obliged to live’: motherhood, chronic illness and biographical disruption. Sociol Health Illn. 2007;29(4):610–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dorrell J, Katz J. . ‘You’re HIV positive’: perinatally infected young people’s accounts of the critical moment of finding out their diagnosis. AIDS Care. 2014;26(4):454–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carricaburu D, Pierret J. From biographical disruption to biographical reinforcement: the case of HIV-positive men. Sociol Health Illn. 1995;17(1):65–88. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ouedraogo R. AIDS and the transition to adulthood of young seropositive women in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso). Glob Health Promot. 2013;20(1 suppl):20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rivera-Diaz M, Varas-Diaz N, Padilla M, et al. Family interaction and social stigmatization of people living with HIV and AIDS in Puerto Rico. Glob Soc Work. 2017;7(13):3–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rael CT, Carballo-Dieguez A, Norton R, et al. Identifying strategies to cope with HIV-related stigma in a group of women living with HIV/AIDS in the Dominican Republic: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(9):2589–2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Anderson M, Elam G, Solarin I, Gerver S, Fenton K, Easterbrook P. Coping with HIV: Caribbean people in the United Kingdom. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(8):1060–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bader A, Kremer H, Erlich-Trungenberger I, et al. An adherence typology: coping, quality of life, and physical symptoms of people living with HIV/AIDS and their adherence to antiretroviral treatment. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12(12):Cr493–Cr500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McIntosh RC, Rosselli M. Stress and coping in women living with HIV: a meta-analytic review. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(8):2144–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Loutfy M, Johnson M, Walmsley S, et al. The association between HIV disclosure status and perceived barriers to care faced by women living with HIV in Latin America, China, Central/Eastern Europe, and Western Europe/Canada. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(9):435–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Abdool Karim Q, Dellar RC, Bearnot B, et al. HIV-positive status disclosure in patients in care in rural South Africa: implications for scaling up treatment and prevention interventions. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(2):322–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Burgess R, Campbell C. Contextualising women’s mental distress and coping strategies in the time of AIDS: a rural South African case study. Transcult Psychiatry. 2014;51(6):875–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Dominican Republic HIV and AIDS estimates. 2014. http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/dominicanrepublic. Accessed February 6, 2016.

- 33. Rojas P, Malow R, Ruffin B, Rothe EM, Rosenberg R. The HIV/AIDS epidemic in the Dominican Republic: key contributing factors. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care. 2011;10(5):306–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic: 2012. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Melgar-Quiñonez H, Uribe A, Fonseca Centeno Z, et al. Psychometric characteristics of the food security scale (ELCSA) applied in Colombia, Guatemala y México. SAN. 2010;17(1):48–60. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Perez Escamilla R, Melgar Quiñonez H, Nord M, Alvarez MC, Segall Correa AM. Escala latinoamericana y caribeña de seguridad alimentaria (ELCSA). Perspect Nutr Human. 2007:117–134. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Altheide DL. Qualitative Media Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Krippendorff KH. Content Analysis. An Introduction to its Methodology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Weber RP. Basic Content Analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Derose KP, Payan DD, Fulcar MA, et al. Factors contributing to food insecurity among women living with HIV in the Dominican Republic: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0181568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Noble H, Smith J. Issues of validity and reliability in qualitative research. Evid Based Nurs. 2015;18(2):34–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stevens PE, Hildebrandt E. Life changing words: women’s responses to being diagnosed with HIV infection. Adv Nurs Sci. 2006;29(3):207–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Barrington C, Kerrigan D, Urena FIC, Brudney K. La vida normal: living with HIV in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Cult Health Sex. 2018;20(1):40–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stevens PE, Tighe Doerr B. Trauma of discovery: women’s narratives of being informed they are HIV-infected. AIDS Care. 1997;9(5):523–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kako PM, Wendorf AR, Stevens PE, Ngui E, Otto-Salaj LL. Contending with psychological distress in contexts with limited mental health resources: HIV-positive Kenyan women’s experiences. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2016;37(1):2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hult JR, Maurer SA, Moskowitz JT. . “I’m sorry, you’re positive”: a qualitative study of individual experiences of testing positive for HIV. AIDS Care. 2009;21(2):185–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gonzalez Rodriguez H, Wallace DD, Barrington C. Contextualizing experiences of diabetes-related stress in Rural Dominican Republic. Qual Health Res. 2018. doi:10.1177/1049732318807207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Roth NL, Nelson MS. HIV diagnosis rituals and identity narratives. AIDS Care. 1997;9(2):161–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Paudel V, Baral KP. Women living with HIV/AIDS (WLHA), battling stigma, discrimination and denial and the role of support groups as a coping strategy: a review of literature. Reprod Health. 2015;12:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tam M, Amzel A, Phelps BR. Disclosure of HIV serostatus among pregnant and postpartum women in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. AIDS Care. 2015;27(4):436–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ahn JV, Bailey H, Malyuta R, Volokha A, Thorne C. Factors associated with non-disclosure of HIV status in a cohort of childbearing HIV-positive women in Ukraine. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(1):174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cohen MS, Smith MK, Muessig KE, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of HIV-1 prevents transmission of HIV-1: where do we go from here? Lancet. 2013;382(9903):1515–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vitalis D, Hill Z. Antiretroviral adherence perspectives of pregnant and postpartum women in Guyana. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2017;16(2):180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Meursing K, Sibindi F. HIV counselling—a luxury or necessity? Health Policy Plan. 2000;15(1):17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Caplan S, Little TV, Reyna P, et al. Mental health services in the Dominican Republic from the perspective of health care providers. Glob Public Health. 2018:13(7):874–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. World Health Organization and Pan American Health Organization. WHO-AIMS Report on Mental Health Systems in Central America and Dominican Republic. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wouters E, Van Damme W, Van Loon F, van Rensburg D, Meulemans H. Public-sector ART in the Free State Province, South Africa: community support as an important determinant of outcome. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(8):1177–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kalichman SC, DiMarco M, Austin J, Luke W, DiFonzo K. Stress, social support, and HIV-status disclosure to family and friends among HIV-positive men and women. J Behav Med. 2003;26(4):315–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Arem H, Nakyanjo N, Kagaayi J, et al. Peer health workers and AIDS care in Rakai, Uganda: a mixed methods operations research evaluation of a cluster-randomized trial. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(12):719–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chang LW, Kagaayi J, Nakigozi G, et al. Effect of peer health workers on AIDS care in Rakai, Uganda: a cluster-randomized trial. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e10923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gusdal AK, Obua C, Andualem T, et al. Peer counselors’ role in supporting patients’ adherence to ART in Ethiopia and Uganda. AIDS Care. 2011;23(6):657–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jerome G, Ivers LC. Community health workers in health systems strengthening: a qualitative evaluation from rural Haiti. AIDS. 2010;24(suppl 1):S67–S72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mukherjee JS, Eustache FE. Community health workers as a cornerstone for integrating HIV and primary healthcare. AIDS Care. 2007;19(suppl 1):S73–S82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]