Abstract

Surveys of egocentric networks are especially vulnerable to methods effects. This study combines a true experiment-random assignment of respondents to receive essentially identical questions from either an in-person interviewer or an online survey--with audio recordings of the in-person interviews. We asked over 850 respondents from a general population several different name-eliciting questions. Face-to-face interviews yielded more cooperation and higher quality data but fewer names than did the web surveys. Exploring several explanations, we determine that interviewer differences account for the mode difference: Interviewers who consistently prompted respondents elicited as many alters as did the web survey and substantially more than did less active interviewers. Although both methods effects substantially influenced the volume of alters listed, they did not substantially modify associations of other variables with volume.

As cost, access, and low response rates drive researchers to abandon in-person interviews for online surveys, attention has turned to understanding how mode affects respondents’ participation and answers (e.g., Public Opinion Quarterly, 2017). We focus here specifically on whether, how, and why online surveys and face-to-face (FTF) interviews may yield different information about egocentric networks. Such data are particularly vulnerable to procedure (e.g., Valente et al., 2017; Paik and Sanchagrin, 2013; Eagle and Proeschold-Bell, 2014; Fischer, 2012), in great measure because answering network questions is long and difficul. This study advances on earlier work by (a) randomly assigning hundreds of diverse adults to either a FTF interview or to an almost identical online survey using name-eliciting questions and (b) coding audio recordings of FTF interviews. FTF interviews yielded more respondent cooperation and higher-quality data but fewer alters than the web survey. We also found sizeable interviewer effects. Both the statistical and the recording evidence suggest that the web advantage in elicited names largely arose—despite design efforts—from the low prompting styles of some interviewers.

Previous Studies

Prior research concludes that self-administered surveys-mail or web-elicit more honest answers, while interviewers, particularly in person, yield higher response rates, induce more engagement, and more accuracy (summaries in Buelens, et al 2012, and de Leeuw and Berzelak, 2016; see also Burkill et al 2016; Kreuter et al 2008; Liu et al 2017; Gravell et al 2013; Pew 2015; 2017). A few studies have examined mode effects specifically on network data. Matzat and Snijders (2010) found that web interviews yielded fewer names than telephone interviews. Vriens and van Ingen (2017) found no web versus FTF effects on the number named, but that web respondents reported more turnover. Bowling’s (2005) review stresses the paucity of proper experimental studies on the topic. Kolenikov and Kennedy (2014), who did use random assignment, found that web respondents provided about one fewer “close” tie than did telephone respondents. Eagle and Proeschold-Bell’s (2015) panel study of clergy found that web interviews yielded many more names (and less variance) than did telephone interviews. In sum: (a) controlled mode comparisons for network studies are rare; and (b) results are mixed but tend to show web surveys yielding fewer names than telephone surveys.

Interviewer Effects.

Studies have found substantial interviewer effects on the number of elicited names. Paik and Sanchagrin (2013, 354) conclude that every study that has looked for them, including their own, has found interviewer effects accounting for 10 to 25 percent of the variance (e.g., van Tilburg 1998; van der Zouwen and van Tilburg 2001; Cornwell and Laumann 2013; Herz and Petermann 2017). Marsden (2003) reported interviewer effects of 15 percent in answers to the “important matters” question, “despite the extensive training of NORC interviewers and [our] high quality standards.” Moreover, Paik and Sanchagrin (2013) find that such effects explain away the controversial McPherson, et al (2006) finding of an historical loss in confidants. In sum, researchers find differences between FTF and web surveys but the direction and explanation seem uncertain. Researchers find strong interviewer effects, but how they operate is also uncertain.

The Present Study: Overview

This study adds several elements to the literature: a mode experiment with random assignment to a FTF or web condition; multiple opportunities to list alters with a variety of connections; and the audio recordings that also allow us to hear what happened in the FTF condition. We ask a sequence of research questions: First, did mode affect respondent cooperation and data quality? Second, did mode affect how many and which alters were elicited? We anticipated that web respondents would satisfice more and care about desirability less (Holbrook et al., 2003) and therefore name fewer alters. Finding, however, that online respondents gave more names led us to ask: Third, what might explain why the web condition yielded more alters? We test several explanations, including self-selection, variations in effort, and interviewer differences. Fourth, finding sizeable interviewer effects, we ask what dynamics in the FTF situation might account for them. Fifth, how much do the mode and interviewer effects influence our substantive understandings of respondents’ networks?

Data and Method

Sample.

The data are drawn from the 2015 wave of the UCNets egocentric network survey conducted in the San Francisco Bay Area (public access: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NACDA/studies/36975/version/1). We look only at wave 1 data here because this is when the respondents were naïve. Pursuing other aims of the study, the project drew participants from two distinct age groups: 21-to-30 year-olds and 50-to-70 year-olds, with—for this analysis—samples of 195 and 674 respondents respectively. (See Supplement, Part A.)

Describing the Egocentric Networks.

In accord with best practices (Paik and Sanchagrin 2013), name-eliciting questions come early in the instrument. Several ask respondents to list the people with whom they are engaged in at least one of several ways: as spouse or romantic partner, household member, social companion, confidant, advisor on important decisions, practical helper, likely helper in a major emergency, recipient of the respondent’s help, and someone whom the respondent finds difficult (Supplement Part B). The 869 respondents analyzed here provided from zero (n=2) to 26 names (n=2), yielding an average of 10.2 names (IQR = 6, from 7 to 13), normally distributed. The survey then asks several questions to obtain descriptions of the alters and the ties: relationship--e.g., parent, neighbor, friend--and various descriptors--e.g., distance, gender, when met, racial homophily (Supplement Part C).

The Mode Experiment.

During the screening interview prospective panel members were randomly assigned, at a 3:1 ratio, to either the FTF or the online condition.1 Ninety-seven percent of the respondents who completed the study used the mode initially assigned to them. (Older women were a bit likelier than older men to end up online, but we confirmed our results by controlling for that.) The findings are the same for actual mode as intended mode, so we largely use actual mode: 647 FTF, 222 on the web.

Consistent with recommendations (Martin et al 2007), the FTF and online instruments are substantively identical. The same custom-written software guided both the interviewers and the web respondents. We used a simple text questionnaire on the web to further standardize across conditions. (See further comment in the Conclusion.) We modified the FTF condition in two general ways: When questions offered many answer options, respondents could see them on a mini-tablet screen (rather than a physical card). In addition, FTF respondents privately answered a battery of sensitive questions on the interviewers’ laptops. (The network data were complete by that point.) Critically, concerned about the possible prompting effects on web respondents of viewing several blank lines ready for names, we provided a comparable verbal prompt in the FTF condition. Interviewers were to read, “I can take up to six names” (Supplement, Part B). As we shall see, this became the leverage point for interviewer effects.

Interviewers.

We were able to use a relatively small number of largely experienced interviewers—10 in all, five of whom completed at least 50 cases. We have audio recordings of 421 of the 647 FTF interviews. Respondents who permitted recording are not a random subset; they gave more names. Who agreed to be recorded was partly a function of the interviewer. Nonetheless, the recordings provide rare insights into the dynamics of the interviews.

Mode Effects on Data Quality

Completion.

To save space, a detailed report on data quality appears as Supplement Part J. We tracked how far people who answered the invitation and began the screening process eventually got in the survey. The table in Supplement Part J presents these data, divided by age cohort. Young respondents were much less likely to proceed than the older respondents and they displayed a mode difference: Many fewer in the web condition continued on in each step; older respondents differed little by mode. Thus, the web interviews appear inferior in sustaining the commitment of reluctant subjects, in this case, 20-somethings (see Kreuter at al, 2008, for similar findings).

Quality.

Poor quality in this context means, in particular, not adhering to instructions about naming--for example, listing couples or groups (e.g., “my family”); duplicating the same alter with a different name—for example, once as “William” and later as “Billy.” We identified that about 3-plus percent of alters listed in the FTF condition versus 13-plus percent in the web condition required hand correction.

“Pagebacks.”

We can track how often respondents or interviewers paged back, presumably to correct an earlier answer, which we interpret as an effort to correct the interview. Paging back was about twice as common in the FTF mode (mn = 23 v. 13; median = 15 v. 6).

All three quality assessments suggest that the FTF condition was clearly superior.

Mode Effects on Number of Names Elicited

Network Counts.

Table 1 presents the number of names—in a few configurations—that respondents gave, by mode. (A fuller table is in Supplement Part D.) There are no significant interaction effects with cohort, so we merge the data. The top line is the total number of unique alters listed across the survey (including spouses and partners). On average, web respondents provided 1.2 more unique names, about one-third of a standard deviation more, than FTF respondents did. An alternative measure of volume is the average number of names respondents gave to the seven activity-based name-eliciting questions, from social companion through “difficult.” (The two volume measures correlate highly, r=.78, but differ.) The mode difference here is larger, about half an SD. In a robustness test, we trimmed and recoded outliers; the results were essentially identical.

Table 1.

Average number of Alters Named by Type, by Mode.

| Face-to-Face (n=647) |

Web (n=222) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | SD | Mean | SD | Diff. | Test | |

| Total N of unique alters | 9.9 | 4.3 | 11.1 | 4.5 | 1.2 | ** |

| Mn. N of alters per name-elicit. Questiona | 2.9 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 0.6 | *** |

| N listed in household | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.1 | |

| N kin (excl. spouse) | 3.2 | 2.4 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 0.2 | |

| N nonkin (excl. partner) | 6.0 | 3.8 | 7.1 | 4.2 | 1.1 | ** |

Notes:

Mode effects significant at p<. 01,

p< .001 based on two-way ANOVA with cohort as a crossed factor.

Questions listed in Supplement Part B.

Mode affected the number of nonkin named–1.1 more in the web condition–but not the number of kin named–only 0.2 more. One plausible explanation is that any mode effect would be weaker for core ties and that kin are more often core. However, mode affected the number of alters described as “close” (Δ= 1.2, ~ 1/4 s.d.), so it may normative centrality rather than emotional centrality that resists a mode effect. Or, perhaps, kin are structured for more robust recall; for example, each sib remembered elicits any others (see also Brashears, 2013). Finally, the finding may reflect a primacy effect: Before the name-eliciting questions, respondents answered questions about how many close kin they had; that may have primed web and FTF respondents equally to list relatives.

The mode effect is specific to name-eliciting. We tested mode effects on 20 different items across the interview instrument (Supplement Part E). Two mode differences are significant at p<.01, both suggesting social desirability in the web condition. And yet: social desirability pressures should have led FTF respondents to provide more names than web respondents; they provided fewer.

The literature suggests that, despite any differences in network size, summary descriptions of the networks should be similar across modes. We test that in Table 2 with 10 attributes of networks. The results are mixed. Six mode comparisons are not significant. On the other hand, web respondents listed slightly higher percentages of geographically and emotionally close alters (for reasons we could not explain). Two other measures show modest differences: exchange multiplexity--the average number of different questions to which each alter was named--and role multiplexity--the average number of different role labels the respondent applied to each name. The findings imply that web respondents were more complete in describing their networks. Later, we explore whether mode (and interviewer) differences affected predictors of network attributes.

Table 2.

Network Descriptions by Mode.

| Face-to-Face (n=645) | Web (n=222) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attributes of Networks | mean | SD | mean | SD | Diff. | Test |

| Prop. kin | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.24 | −0.01 | |

| Prop. feel close to | 0.45 | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.24 | 0.07 | ** |

| Prop. within 5 minutes | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.04 | *** |

| Prop. met in last year | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.02 | |

| Prop. same gender | 0.63 | 0.24 | 0.64 | 0.19 | 0.01 | |

| Prop. same age | 0.48 | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.26 | 0.04 | |

| Prop. same race | 0.74 | 0.29 | 0.75 | 0.26 | 0.01 | |

| Prop. same politics | 0.81 | 0.25 | 0.83 | 0.22 | 0.01 | |

| Mn. exch. Multiplexitya | 2.09 | 0.65 | 2.33 | 0.64 | 0.24 | *** |

| Mn. role multiplexityb | 1.35 | 0.39 | 1.44 | 0.45 | 0.10 | *** |

Notes:

Question texts are in Online Supplement, Section C. Mode effects significant at

** p<.01,

*** p<. 001.

Statistical tests are based on two-way ANOVA with cohort sample as a crossed factor. There is a significant interaction effect (p<.05) for Prop. same race (.61 vs. .71 for the young; .78 vs. .77 for the older respondents).

The “exchange multiplexity” of each alter is the number of active name-eliciting questions (social to difficult) the alter was nominated to. The mean here is the average of those alter scores for each respondent.

The “role multiplexity” of each alter is the number of different kinds of relationships (e.g., sibling, coworker, friend) ego reported having with that person. The mean here is the average of those alter scores for each respondent

In sum, although the FTF mode elicited more respondent effort to be complete and accurate, it elicited fewer alters—specifically, fewer nonkin alters—than did the web. The mode effects are specific to name elicitation and have real but small effects on point estimates for network attributes.

Explaining the Mode Effect

We address four explanations for the mode effect on alter volume: self-selection, differential effort, technical differences, interviewer effects.

Self-Selection.

Perhaps the dropouts from the web condition (see above) were disproportionately people who would have reported small networks had they continued. Perhaps people uncomfortable on the web have fewer social ties. Supplement Part F describes our efforts to test that idea by drawing using information on dropouts. The exercise provides little support for self-selection as an explanation. We also constructed a model to predict how many names the dropouts would have, based on demographics, given. This exercise, too, suggests that selective dropping out explains little, if any, of the mode effect.2

Effort.

Interviewers should be better able to encourage effort than a web program and so garner more alters (Perry et al, 2018). Although our results were the opposite, differential effort might still be a factor. A web survey allows respondents to move at their own pace and pause longer to recall names—or even, as a reviewer notes, to look them up. Perhaps, then, respondent fatigue in the FTF condition explains the fewer names. In Supplement Part G, we examine three indicators of effort: time spent on the survey; willingness to answer optional questions; and any drop-off in the number of names listed as the survey proceeded. These measures do not indicate more fatigue or less effort by the FTF respondents.

Technical Differences.

One mechanical feature that might explain the mode effect is “backfilling,” respondents going back to give a name that had slipped their minds. Perhaps, FTF respondents were more reluctant to confess error and to ask the interviewer to backtrack. Paging back, as discussed earlier, was indeed associated with providing more names, but it actually occurred much more often in FTF interviews and so cannot explain the FTF deficit in names.

One technical explanation follows from literature on web survey administration: the prompting effect of seeing six blank lines on a screen may press web respondents toward giving more names (e.g., Vehovar et al 2008). As noted earlier, we inserted a phrase i in the FTF version for interviewers to read each time: “I can take up to six names.” As it turns out-and as we discuss immediately-interviewers’ following of this script was highly inconsistent, which leads us to consider differential prompting as the major explanation for the mode effect.

Interviewer Effects

We first exam interviewer effects across our ten interviewers and afterwards ask whether they help explain the mode effect on the volume of names. Studies suggest that interviewer effects result from differences among interviewers in building rapport, persuading respondents to answer sensitive questions (West and Blom 2017), probing for detail (Van der Zouwen and Van Tilburg 2001; Houtkoop-Seenstra 1996), and getting clarifications (Mittereder et al 2017). Other studies suggest that network differences arise if some interviewers learn to shorten interviews by eliciting fewer names (Harling et al 2018; Josten and Trappman 2016; Valente et al. 2017).

Our data show significant interviewer variation in the total number of unique names elicited--from a mean of 8.2 to one of 12.2--and in the average number of names elicited per question−−2.1 to 3.7. Interviewer differences account for about eight percent of the variance in total unique names and about 22 percent in the variance in average number of names per question--comparable to Paik and Sanchagrin’s (2013, 354) estimate from previous studies of 10 to 25 percent of the variation in total names. Adding several covariates--age, gender, race, education, zip code--does not alter the effect sizes. And unlike some other studies, there were no consistent time trends.

We had too few interviewers to systematically analyze what about the interviewers mattered (cf. Van Tilburg 1998; Harling et al 2017), but we found out what was actually happening in the interviews by listening to audio recordings. About two-thirds of the FTF respondents permitted us to record the interviews. Following work on differential probing behavior (West and Blom 2017; Mittereder et al., 2017; van der Zouwen and van Tilburg 2001; Houtkoop-Seenstra 1996), we examined interviewers’ probing for each of six name-eliciting questions in the survey. Did interviewers, as instructed, invite respondents to give up to six names (nine names for the sociability question)? Did they prompt respondents for names in any other way, for example, asking “Is there anyone else?” after respondents listed one or two names? We coded a random sample of 10 recordings for each of nine interviewers. Table 3 displays the average percentage of questions each interviewer accompanied with a prompt, along with other data by interviewer.

Table 3:

Interviewer Differences in Prompting Behavior (Based on Ten Recordings Each), Number of Names Elicited, and Mean Time in Eliciting Section.

| Interviewer | Average percent of questions prompteda |

Percent of q’s using other promptingb |

Mean number unique names elicitedc |

Mean number of names per questiond |

Mean number of minutes in name-eliciting sectione |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31 | 10 | 10.7 | 3.3 | 8.5 |

| 2 | 63 | 3 | 12.2 | 3.6 | 7.3 |

| 3 | 11 | 2 | 8.7 | 2.1 | 6.5 |

| 4 | 4 | 36 | 12.0 | 3.7 | 8.9 |

| 5 | 45 | 33 | 10.3 | 3.2 | 8.9 |

| 6 | 12 | 3 | 9.5 | 2.8 | 7.6 |

| 7 | 1 | 12 | 8.2 | 2.2 | 8.2 |

| 8 | 61 | 9 | 11.5 | 3.6 | 9.3 |

| 9 | 60 | 53 | 11.7 | 3.7 | 10.0 |

Notes: Interviewer 10 only conducted two interviews, so was not included in the analysis.

We consider interviewers “prompting” respondents when they mimicked the web administration of the survey by reading the entire prompt and—in particular—telling respondents how many names they could list for a question.

“Other prompting language” included instances where the interviewer asked the respondent questions such as, “Is there anyone else?”, “Is that all?”, or “How about your sister?”, or if interviewers told respondents “I have space for x more names.”

The average number of total unique names respondents provided to that interviewer.

The average, across respondents, of the mean number of names provided per question for that interviewer.

The average, across respondents, of the mean number of minutes in the main name-eliciting section for that interviewer. (The mean for web respondents is 9.6, with a higher skew than among interviewers.)

On average, interviewers read the explicit prompt (“I can take....”) only 32 percent of the time, with substantial variation between interviewers. We identified four ways that interviewer prompting influenced the number of names. First, interviewers linguistically cued how many names they expected. For example, the lowest-prompting interviewer regularly asked respondents for “a” name without telling them how many slots were available. Here are two passages.

(Respondent says that she goes to movies about once a month.)

Interviewer: “And who might you do that with?” (abbreviating the written question—see Supplement Part B).

Respondent: “My friends.”

I: “Can I get a name? Or names?”

(Respondent gives two names, and interviewer moves on to the next question. The respondent may not have understood that the question concerned all sorts of social activities.)

And:

I: “Sometimes there are people in our lives who are demanding or difficult. Who are some people you find demanding or difficult?”

R: [Pause] “People’s names? Do you need a name?”

I: “Mmm-hmm.”

R: “How about D.? My sister.”

I: “Ok, D. it is. So, next question...”

High-prompting interviewers, in contrast, either told respondents how many slots they had available, or asked how many names a respondent wanted to list in an open-ended fashion, such as “Who do you help?”.

Second, interviewers could prompt respondents by asking for additional names, particularly during pauses or after sets of related names (such as family). Low-prompting interviewers almost never asked for additional names. They also did not give respondents much time to list names, taking every pause in conversation as a cue to move on.

I: “Has anyone given you any practical help?... And who would that person be?”

R: [Lists a name]

I: “Very good.” (Moves on to the next question.)

In contrast, high-prompting interviewers regularly asked respondents for additional names, occasionally multiple times in the same question. They also reminded respondents about specific people whom they may have forgotten. Such prompting could overcome lack of clarity about the number of slots available. For example, the interviewer who elicited the highest average number of names prompted respondents the least with how many slots remained available, but she regularly followed up by asking whether respondents had additional names.

I: “Who do you confide in?”

R: “My friend Chris.”

I: “Do you confide in K. (respondent’s husband) too?”

R: “Yeah, I guess, depending on what it is.” (laughs)

I: “Anyone else?”

R: “Not really anymore--that’s about it.”

And:

I: “Please think about the people that you typically do these types of things with, orother social things as well, such as . . . . . Who are the people that you do these types of things with? I can take up to nine names.”

R: (laughs) “Well, it’s actually a much shorter list. K. L. J. (Interviewer confirms spelling after each name) And then my sister E. Oh, and then my neighbor N.

I: “Anyone else?”

R: “No, that’s the main core. Oh, D.!”

I: “We got it?”

R: “Yeah.”

I: “Ok.” (begins to move on)

R: “Well...”

I: “I can go back.”

R: “So. . . ask me the question again.”

I: (repeats the question)

R: “So then I need to add a couple more. D. (spells)”

I: “I can take two more after this, and then I’m full up.”

R: “E.”

I: “I can have one more if you want.”

R: “Yeah, let me think.” (Six-secondpause) R.

I: “Ok.”

Finally, although rare, some interviewers made explicit statements that might have discouraged respondents from giving more names.

I: “Is there anyone who’s given you practical help recently?”

R: [pauses to think]

I: “Probably not then, if it hasn’t come to you yet.”

R: “It’s just hard to think. I mean we haven’t moved, we haven’t done anything like that.”

I: “I got a ‘don’t know’ button too.”

R: “Don’t know!” [Interviewer moves on]

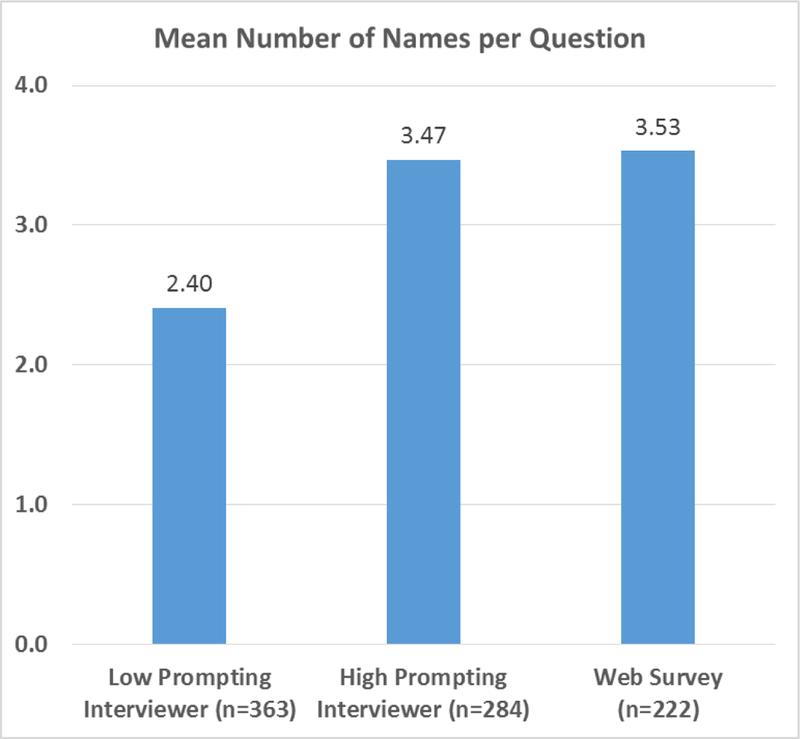

No particular interviewer(s) can account for the mode difference. (Supplement Part H shows the results from repeated in which we dropped each interviewer’s cases.) However, prompting style—measured independently by listening to the recordings--can account for much of the mode effect. Drawing on Table 3, above, we dichotomized the FTF cases between those of interviewers who were active prompters and those of interviewers who were less active prompters.3 Figure 1 compares the mean number of names elicited per question for respondents of low-prompting, high-prompting interviewers, the web. (Age cohort did not interact with mode and so is not shown.) Low-prompting interviewers’ results were distinctively low, which is also true for the total number of unique names listed. The overall pattern is significant at p<.001, eta-squared = .18, but the high-prompting vs. web contrast is not significant. For the total number of unique alters, not shown, low prompting = 8.8, high-prompting = 11.2, web = 11.1 (p<.001, eta squared = .07). The high-prompting vs. web contrast is not significant. That a few interviewers could not or chose not to replicate verbally the level of prompting provided by six blank lines on a screen seems to explain the mode effect.

Figure 1.

Mean Number of Names Elicited per Question Elicited for Respondents Interviewed by High-Prompting Interviewers, Interviewed by Low-Prompting Interviewers, and Surveyed on the Web.

A reviewer asked, reasonably, whether what mattered was interviewer prompting or interviewer patience in waiting for names. The two are, of course, connected. But our eavesdropping and some limited statistical data—average time spent eliciting names is shown in Table 3--suggest that active prompting was the more important (see Supplement Part K). Also, high prompters engaged in significantly more paging back during the interviews.

We also examined the correlations with name volume of various attributes of the FTF situation—where it took place, who else was present, interruptions, and the like. A few modest associations appeared,4 but they neither changed the interviewer differences nor the implications for understanding the mode effect.

How Much Do Mode and Interviewer Matter?

Both mode and especially interviewer style are substantially associated with the number of names respondents provided. But how much do they affect substantive results? To wrap up our analysis, we estimated predictive models using basic demographics and then added mode and interviewer effects (low- vs. high-prompters) to the models. As shown in Supplement Part I, adding the methods variables—especially, low- versus high-prompting interviewer--increases the R-squared notably. However, adding them to the models does not meaningfully change the other effects estimates nor the substantive implications—for example, that men reported about one fewer names than did women. In addition, we tested whether mode and/or interviewer affected the associations of key demographic variables with several network counts. They did not. Using two-way ANOVAs, we tested 20 interactions: the effects of method (low-prompter v. high-prompter v. web) crossed by, separately, age cohort, gender, having less than a BA degree, and partner status on the number of alters, number of nonkin alters, mean number of alters per question, number of sociability partners, and number of confidants. No interaction effects were significant at p<.05; one reached p<.10.5

Conclusion

The good news is that an online egocentric network survey can generate as many names as can a vigorous interviewer; the bad news is that less vigorous interviewers can substantially reduce the observed size of networks and that online surveys have quality issues. By combining a true experiment with listening in on interviews, we found that: (1) FTF interviews yielded more completions, cooperation, and higher quality data—although we have also found that neither mode nor interviewer affected the chances that respondents participated in the next wave (contra Pickery et al 2001). (2) FTF interviews yielded about 10 percent fewer total alters—specifically, about 15 percent fewer nonkin alters--than did the web condition and, even more sharply, yielded almost 20 percent fewer alters per name-eliciting question than the web (Table 2). (3) Large interviewer differences were the key to understanding the mode effect: Those interviewers who actively prompted elicited as many total names as did the blank lines on the web screen. (4) Mode and interviewer significantly affected the volume of alters elicited but did not change the observed effects of other variables on that volume or on other network counts.

As one reviewer noted, there are many new, visually interactive, online name-generator packages available (Stark and Krosnick 2017; Hogan et al. 2016; Tubaro et al. 2014; McCarty and Govindaramanujam 2005). Such formats might yield different data quality or quantity than we observed. Given that our web questionnaire was probably less engaging and motivating than such programs are, they might elicit even more names than our online format did.

The implication for practitioners is that the much cheaper web survey can yield the volume of alters that conscientious FTF interviewers can, but with trade-off of fewer completions and more errors in the data. The ideal although highly expensive option is that well-trained, -motivated, and –supervised interviewers can yield both quality data and longer lists of alters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This research is supported by National Institute of Aging Grant R01 AG041955–01. We thank the UCNets project’s executive director, Leora Lawton, and UCNets’ many participants for support and comments; the Center for Economic and Social Research at the University of Southern California for development and data management, especially programmer Bart Orriens; and Nexant fieldwork managers, Kenric Erickson and Cat Conti.

Footnotes

Subsequent waves of the survey move some respondents from FTF to web so that we will eventually have a 1:3 ratio and will eventually be able to do both between- and within-respondent mode comparisons.

Nor are personality differences implicated. Mode is unassociated with Big-5 personality items.

Combining both types of prompting in Table 3, we coded interviewers 9, 5, 8, 2, 1, and 4 (and #10) as high prompters (n = 284 respondents) and interviewers 3, 6, and 7 as low prompters (n= 363).

For example, more names per question emerged when the interview took place in a sitting room than outside a home or in a commercial venue, fewer names when there were no interruptions. Controlling for such factors does not alter the low- versus high-prompter difference. One reviewer noted that we have no comparable information about the setting in which web respondents answered. True. Perhaps a future study could ask web respondents or extract their permission to have a web camera record.

Respondents with a spouse or partner generally reported more names (more kin, actually) than those without one, but the difference is minimal for respondents of low-prompting interviewers.

Contributor Information

Claude S. Fischer, University of California, Berkeley

Lindsay Bayham, University of California, Berkeley.

References

- Bowling A 2005. Mode of Questionnaire Administration Can Have Serious Effects on Data Quality. Journal of Public Health 27:281–91. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brashears ME 2013. Humans Use Compression Heuristics to Improve the Recall of Social Networks. Scientific Reports 3. doi: 10.1038/srep01513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buelens B, van der Laan J, Schouten B, et al. 2012. Disentangling Mode-Specific Selection and Measurement Bias in Social Surveys Discussion Paper. Statistics Netherlands: The Hague. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkill S, Copas A, Couper MP, et al. (2016) Using the Web to Collect Data on Sensitive Behaviours: A Study Looking at Mode Effects on the British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. PLoS ONE 11(2): e0147983. 10.1371/journal.pone.0147983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw E, Berzelak N 2016. Survey Mode or Survey Modes? In Wolf C, Joye D, Smith TW, Fu Y-C (Eds.), Pp. 142–156. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Eagle DE, Proeschold-Bell RJ 2014. Methodological Considerations in the Use of Name Generators and Interpreters. Social Networks 40:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer CS 2012. Results of 2010 GSS Network Experiment. INSNA Listserv, SOCNET Archives, https://lists.ufl.edu/cgi-bin/wa?A2=S0CNET;0A5sjw;20120902180053-0700.

- Gravell CC, Bernard HR, Maxwell CR, Jacobsohn A 2013. Mode Effects in Free-List Elicitation. Social Science Computer Review 31: 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Harling G, Perkins JM, Gómez-Olivé FX, et al. 2018. Interviewer-Driven Variability in Social Network Reporting: Results from Health and Aging in Africa: a Longitudinal Study of an INDEPTH community (HAALSI) in South Africa. Field Methods 30(2): 140–54 http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1525822X18769498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerwegh D 2009. Mode Differences Between Face-to-Face and Web Surveys: An Experimental Investigation of Data Quality and Social Desirability Effects. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 21: 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Herz A, Petermann S 2017. Beyond Interviewer Effects in the Standardized Measurement of Ego-Centric Networks. Social Networks 50: 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan B, and others. 2016. “Evaluating the Paper-to-Screen Translation of Participant-Aided Sociograms with High-Risk Participants.” CHI ‘16 Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems: 5360–71 DOI: 10.1145/2858036.2858368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homola J, Jackson N, Gill J 2016. A Measure of Survey Mode Differences. Electoral Studies 44:255–74. 10.1016/j.electstud.2016.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook AL, Green MC, Krosnick JA 2003. Telephone Versus Face-to-Face Interviewing of National Probability Samples with Long Questionnaires: Comparisons of Respondent Satisficing and Social Desirability Response Bias. Public Opinion Quarterly 67(1):79–125. doi: 1 [Google Scholar]

- Houtkoop-Steenstra H 1996. Probing behaviour of interviewers in the standardised semi-open research interview. Quality and Quantity 30: 205–230. [Google Scholar]

- Josten M, Trappmann M 2016. Interviewer Effects on a Network Size Filter Question. Journal of Official Statistics 32: 349–373. [Google Scholar]

- Kolenikov S, Kennedy C 2014. Evaluating Three Approaches to Statistically Adjust for Mode Effects. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology 2(2):126–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter F, Presser S, and Tourangeau R. 2008. Surveys: The Effects of Mode and Question Sensitivity. Public Opinion Quarterly 72: 847–865. 10.1093/poq/nfn063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Conrad FG, Sunghee S 2017. Comparing Acquiescent and Extreme Response Styles in Face-to-Face and Web Surveys. Quality & Quantity 51:941–58. doi: 10.1007/s11135-016-0320-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden PV 2003. Interviewer Effects in Measuring Network Size Using a Single Name Generator. Social Networks 25:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Martin E, Childs JH, DeMaio T, et al. 2007. Guidelines for Designing Questionnaires for Administration in Different Modes. U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Matzat U, Snijders C 2010. Does the Online Collection of Ego-Centered Network Data Reduce Data Quality? An Experimental Comparison. Social Networks 32(2):105–11. 10.1016/j.socnet.2009.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty C, & Govindaramanujam S (2005). A Modified Elicitation of Personal Networks Using Dynamic Visualization. Connections 26(2), 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Brashears ME 2006. Social Isolation in America: Changes in Core Discussion Networks over Two Decades. American Sociological Review 71(3): 353–75 [Google Scholar]

- Mittereder F, Durow J, West BT, et al. 2017. Interviewer-Respondent Interactions in Conversational and Standardized Interviewing. Field Methods. Online: http://iournals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1525822X17729341. [Google Scholar]

- Paik A, Sanchagrin K 2013. Social Isolation in America: An Artifact. American Sociological Review 78: 339–360. [Google Scholar]

- Perry BL, Pescosolido BA, Borgatti SP 2018. Egocentric Network Analysis: Foundations, Methods, and Models. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2015. From Telephone to the Web: The Challenge of Mode of Interview Effects in Public Opinion Polls. Washington: Pew. http://www.pewresearch.org/2015/05/13/from-telephone-to-the-web-the-challenge-of-mode-of-interview-effects-in-public-opinion-polls/.

- Pew Research Center. 2017. Personal Finance Questions Elicit Slightly Different Answers in Phone Surveys than Online. Washington: Pew. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/08/04/personal-finance-questions-elicit-slightly-different-answers-in-phone-surveys-than-online

- Pickery J,Loosveldt G, Carton A 2001. The Effects of Interviewer and Respondent Characteristics on Response Behavior in Panel Surveys. Sociological Methods and Research 29: 509–523. [Google Scholar]

- Public Opinion Quarterly. 2017. Special Issue: Survey Research, Today and Tomorrow. Vol. 81. [Google Scholar]

- Stark TH, & Krosnick JA (2017). GENSI: A New Graphical Tool to Collect Ego-Centered Network Data. Social Networks 48, 36–45. https://doi.org/10.10167j.socnet.2016.07.007 [Google Scholar]

- Tubaro P, Casilli AA, & Mounier L (2014). Eliciting Personal Network Data in Web Surveys through Participant-generated Sociograms. Field Methods 26(2), 107–125. 10.1177/1525822X13491861 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW, Dougherty L, Stammer E 2017. Response Bias over Time: Interviewer Learning and Missing Data in Egocentric Network Surveys. Field Methods. http://journals.sagepub.com/eprint/wAvkQ72fBVwVUJmJGKuR/full. [Google Scholar]

- van der Zouwen J, van Tilburg T 2001. Reactivity in Panel Studies and Its Consequences for Testing Causal Hypotheses. Sociological Methods & Research 30:35–56. [Google Scholar]

- van Tilburg T 1998. Losing and Gaining in Old Age: Changes in Personal Network Size and Social Support in a Four-Year Longitudinal Study. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 53B:S313–S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vehovar V, Manfreda KL, Koren G, Hlebec V 2008. Measuring Ego-Centered Social Networks on the Web: Questionnaire Design Issues. Social Networks 30: 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Vriens E, van Ingen E 2017. Does the Rise of the Internet Bring Erosion of Strong Ties? Analyses of Social Media Use and Changes in Core Discussion Networks. New Media & Society: 1–18. doi: 10.1177/1461444817724169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West BT, Blom AG 2017. Explaining Interviewer Effects: A Research Synthesis. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology 5: 175–211. 10.1093/jssam/smw024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.