Abstract

The Yamnaya expansions from the western steppe into Europe and Asia during the Early Bronze Age (~3000 BCE) are believed to have brought with them Indo-European languages and possibly horse husbandry. We analyze 74 ancient whole-genome sequences from across Inner Asia and Anatolia and show that the Botai people associated with the earliest horse husbandry derived from a hunter-gatherer population deeply diverged from the Yamnaya. Our results also suggest distinct migrations bringing West Eurasian ancestry into South Asia before and after but not at the time of Yamnaya culture. We find no evidence of steppe ancestry in Bronze Age Anatolia from when Indo-European languages are attested there. Thus, in contrast to Europe, Early Bronze Age Yamnaya-related migrations had limited direct genetic impact in Asia.

The vast grasslands making up the Eurasian steppe zones, from Ukraine through Kazakhstan to Mongolia, have served as a crossroad for human population movements during the last 5000 years (1–3), but the dynamics of its human occupation—especially of the earliest period—remain poorly understood. The domestication of the horse at the transition from the Copper Age to the Bronze Age ~3000 BCE, enhanced human mobility (4, 5) and may have triggered waves of migration. According to the “Steppe Hypothesis,” this expansion of groups in the western steppe related to the Yamnaya and Afanasievo cultures was associated with the spread of Indo-European (IE) languages into Europe and Asia (1, 2, 4, 6). The peoples who formed the Yamnaya and Afanasievo cultures belonged to the same genetically homogenous population, with direct ancestry attributed to both Copper Age (CA) western steppe pastoralists, descending primarily from the European Eastern hunter-gatherers (EHG) of the Mesolithic, and to Caucasian groups (1, 2), related to Caucasus hunter-gatherers (CHG) (7).

Within Europe, the “Steppe Hypothesis” is supported by the reconstruction of Proto-IE (PIE) vocabulary (8), as well as by archaeological and genomic evidence of human mobility and Early Bronze Age (3000–2500 BCE) cultural dynamics (9). For Asia, however, several conflicting interpretations have long been debated. These concern the origins and genetic composition of the local Asian populations encountered by the Yamnaya- and Afanasievo-related populations, including the groups associated with Botai, a site that offers the earliest evidence for horse husbandry (10). In contrast, the more western sites that have been supposed by some to reflect the use of horses in the Copper Age (4) lack direct evidence of domesticated horses. Even the later use of horses among Yamnaya pastoralists has been questioned by some (11) despite the key role of horses in the “Steppe Hypothesis.” Furthermore, genetic, archaeological, and linguistic hypotheses diverge on the timing and processes by which steppe genetic ancestry and the IE languages spread into South Asia (4, 6, 12). Similarly, in present-day Turkey, the emergence of the Anatolian IE language branch including the Hittite language remains enigmatic, with conflicting hypotheses about population migrations leading to its emergence in Anatolia (4, 13).

Ancient genomes inform upon human movements within Asia

We analyzed whole genome sequence data of 74 ancient humans (14, 15) (Tables S1 to S3) ranging from the Mesolithic (~9000 BCE) to Medieval times, spanning ~5000 km across Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and Western Asia (Anatolia) (Fig. 1). Our genome data includes 3 Copper Age individuals (~3500–3300 BCE) from Botai in northern Kazakhstan (Botai_CA; 13.6X, 3.7X, and 3X coverage, respectively), 1 Early Bronze Age (~2900 BCE) Yamnaya sample from Karagash, Kazakhstan(16) (YamnayaKaragash_EBA; 25.2X), 1 Mesolithic (~9000 BCE) EHG from Sidelkino, Russia (SidelkinoEHG_ML; 2.9X), 2 Early/Middle Bronze Age (~2200 BCE) central steppe individuals (~4200 BP) (CentralSteppe_EMBA; 4.5X and 9.1X average coverage, respectively) from burials at Sholpan and Gregorievka that display cultural similarities to Yamnaya and Afanasievo (12), 19 individuals of the Bronze Age (~2500–2000 BCE) Okunevo culture of the Minusinsk Basin in the Altai region (Okunevo_EMBA; ~1X average coverage; 0.1–4.6X), 31 Baikal Hunter-Gatherer genomes (~1X average coverage; 0.2–4.5X) from the cis-Baikal region bordering on Mongolia and ranging in time from the Early Neolithic (~5200–4200 BCE; Baikal_EN) to the Early Bronze Age (~2200–1800 BCE; Baikal_EBA), 4 Copper Age individuals (~3300–3200 BCE; Namazga_CA; ~1X average coverage; 0.1–2.2X) from Kara-Depe and Geoksur in the Kopet Dag piedmont strip of Turkmenistan, affiliated with the period III cultural layers at Namazga-Depe (Fig. S1), plus 1 Iron Age individual (Turkmenistan_IA; 2.5X) from Takhirbai in the same area dated to ~800 BCE, and 12 individuals from Central Turkey (Figs. S2 to S4), spanning from the Early Bronze Age (~2200 BCE; Anatolia_EBA) to the Iron Age (~600 BCE; Anatolia_IA), and including 5 individuals from presumed Hittite-speaking settlements (~1600 BCE; Anatolia_MLBA), and 2 individuals dated to the Ottoman Empire (1500 CE; Anatolia_Ottoman; 0.3–0.9X). All the population labels including those referring to previously published ancient samples are listed in Table S4 for contextualization. Additionally, we sequenced 41 high-coverage (30X) present-day Central Asian genomes, representing 17 self-declared ethnicities (Fig. S5) as well as collected and SNP-typed 140 individuals from 5 IE-speaking populations in northern Pakistan.

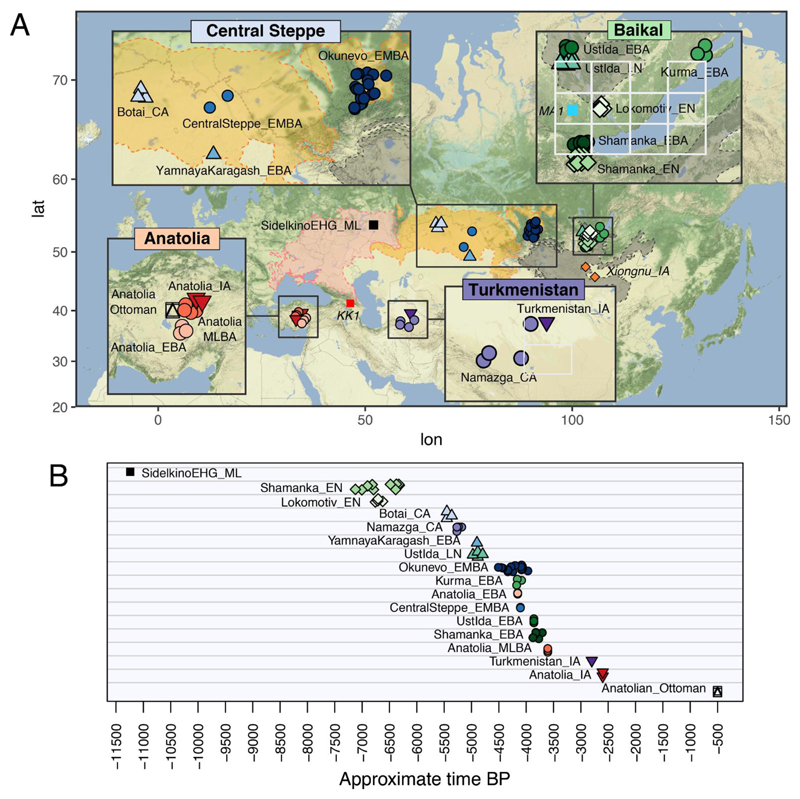

Fig. 1.

Geographic location and dates of ancient samples. A) Location of the 74 samples from the steppe, Lake Baikal region, Turkmenistan, and Anatolia analyzed in the present study. MA1, KK1, and Xiongnu_IA were previously published. Geographical background colors indicate the western steppe (pink), central steppe (orange) and eastern steppe (gray). B) Timeline in years before present (BP) for each sample. ML – Mesolithic, EHG – Eastern hunter-gatherer, EN – Early Neolithic, LN – Late Neolithic, CA – Copper Age, EBA – Early Bronze Age, EMBA – Early/Middle Bronze Age, MLBA – Middle/Late Bronze Age, IA – Iron Age.

Tests indicated that the contamination proportion of the data was negligible (14) (see Table S1), and we removed related individuals from frequency-based statistics (Fig. S6; Table S5). Our high-coverage Yamnaya genome from Karagash is consistent with previously published Yamnaya and Afanasievo genomes, and our Sidelkino genome is consistent with previously published EHG genomes, on the basis that there is no statistically significant deviation from 0 of D-statistics of the form D(Test, Mbuti; SidelkinoEHG_ML, EHG) (Fig. S7) or of the form D(Test, Mbuti; YamnayaKaragash_EBA, Yamnaya) (Fig. S8; additional D-Statistics shown on Figs. S9 to S12).

Genetic origins of local Inner Asian populations

In the Early Bronze Age around 3000 BCE, the Afanasievo culture was formed in the Altai region by people related to the Yamnaya, who migrated 3000 km across the central steppe from the western steppe (1), and are often identified as the ancestors of the IE-speaking Tocharians of 1st millennium northwestern China (4, 6). At this time, the region they passed through was populated by horse hunter-herders (4, 10, 17), while further east the Baikal region hosted groups that had remained hunter-gatherers since the Paleolithic (18–22). Subsequently, the Okunevo culture replaced the Afanasievo culture. The genetic origins and relationships of these peoples have been largely unknown (23, 24).

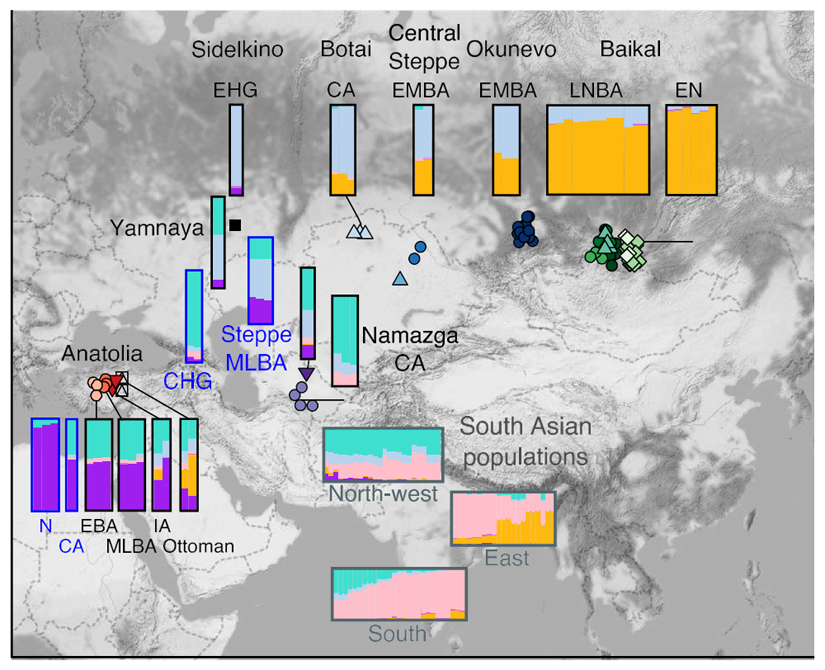

To address these issues we characterized the genomic ancestry of the local Inner Asian populations around the time of the Yamnaya and Afanasievo expansion. Comparing our ancient samples to a range of present-day and ancient samples with principal components analysis (PCA), we find that the Botai_CA, CentralSteppe_EMBA, Okunevo_EMBA, and Baikal populations (Baikal_EN and Baikal_EBA) are distributed along a previously undescribed genetic cline. This cline extends from the EHG of the western steppe to the Bronze Age (~2000–1800 BCE) and Neolithic (~5200–4200 BCE) hunter-gatherers of Lake Baikal in Central Asia, which are located on the PCA plot close to modern East Asians and two Early Neolithic (~5700 BCE) Devil’s Gate samples (25) (Fig. 2, and Fig. S13). In accordance with their position along the west-to-east gradient in the PCA, increased East Asian ancestry is evident in ADMIXTURE model-based clustering (Fig. 3; Figs. S14 and S15) and by D-statistics for Sholpan and Gregorievka (CentralSteppe_EMBA) and Okunevo_EMBA, relative to Botai_CA and the Baikal_EN sample: D(Baikal_EN, Mbuti; Botai_CA, Okunevo_EMBA) = -0.025 Z = -12; D(Baikal_EN, Mbuti; Botai_CA, Sholpan) = -0.028 Z = -8.34; D(Baikal_EN, Mbuti; Botai_CA, Gregorievka) = -0.026 Z = -7.1. The position of this cline suggests that the central steppe Bronze Age populations all form a continuation of the “Ancient North Eurasian” (ANE) population, previously known from the 24-kyr-old Mal’ta (MA1), the 17-kyr-old AG-2 (26), and the ~14.7- kyr-old AG-3 (27) individuals from Siberia.

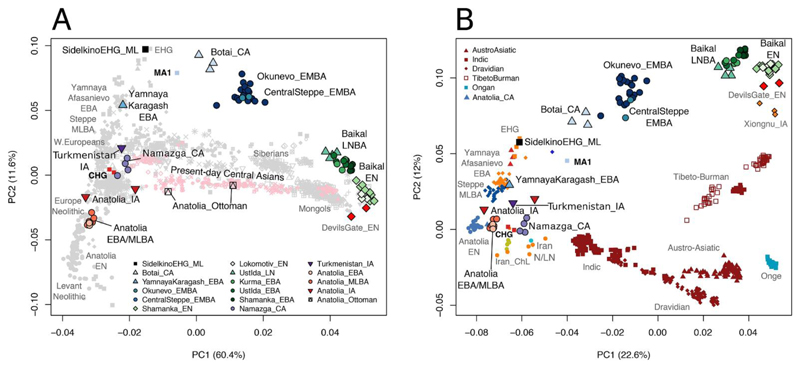

Fig. 2.

Principal component analyses using ancient and present-day genetic data. A) PCA of ancient and modern Eurasian populations. The ancient steppe ancestry cline from EHG to Baikal_EN is visible at the top outside present-day variation, while the YamnayaKaragash_EBA sample has additional CHG ancestry and locates to the left with other Yamnaya and Afanasievo samples. Additionally, a shift in ancestry is observed between the Baikal_EN and Baikal_LNBA, consistent with an increase in ANE-related ancestry in Baikal_LNBA. B) PCA estimated with a subset of Eurasian ancient individuals from the steppe, Iran, and Anatolia as well as present-day South Asian populations. PC1 and PC2 broadly reflect West-East and North-South geography, respectively. Multiple clines of different ancestry are seen in the South Asians, with a prominent cline even within Dravidians in the direction of the Namazga_CA group, which is positioned above Iranian Neolithic in the direction of EHG. In the later Turkmenistan_IA sample, this shift is more pronounced and towards Steppe EBA and MLBA. The Anatolia_CA, EBA and MLBA samples are all between Anatolia Neolithic and CHG, not in the direction of steppe samples.

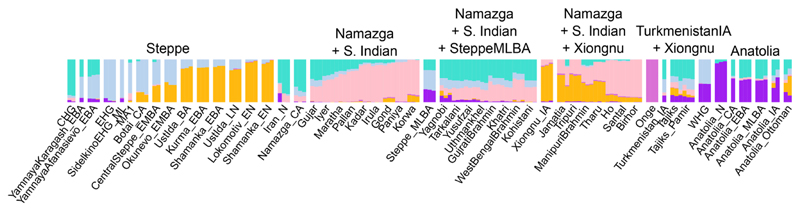

Fig. 3.

Model-based clustering analysis of present-day and ancient individuals assuming K = 6 ancestral components. The main ancestry components at K = 6 correlate well with CHG (turquoise), a major component of Iran_N, Namazga_CA and South Asian clines; EHG (pale blue), a component of the steppe cline and present in South Asia; East Asia (yellow ochre), the other component of the steppe cline also in Tibeto-Burman South Asian populations; South Indian (pink), a core component of South Asian populations; Anatolian_N (purple), an important component of Anatolian Bronze Age and Steppe_MLBA; Onge (dark pink) forms its own component.

To investigate ancestral relationships between these populations, we used coalescent modelling with the momi program (28) (Fig. 4; Figs S16 to S22; Tables S6 to S11). This exploits the full joint-site frequency spectrum and can separate genetic drift into divergence-time and population-size components, in comparison to PCA, admixture, and qpAdm approaches, which are based on pairwise covariances. We find that Botai_CA, CentralSteppe_EMBA, Okunevo_EMBA, and Baikal populations are deeply separated from other ancient and present-day populations and are best modelled as mixtures in different proportions of ANE ancestry and an Ancient East Asian (AEA) ancestry component represented by Baikal_EN with mixing times dated to approximately 5000 BCE. Although some modern Siberian samples lie under the Baikal samples in Fig. 2A, these are separated out in a more limited PCA, involving just those populations and the ancient samples (Fig. S23). Our momi model infers that the ANE lineage separated approximately 15 kya in the Upper Paleolithic from the EHG lineage to the west, with no independent drift assigned to MA1. This suggests that MA1 may represent their common ancestor. Similarly, the AEA lineage to the east also separated around 15 kya, with the component that leads to Baikal_EN and the AEA component of the steppe separating from the lineage leading to present-day East Asian populations represented by Han Chinese (Figs. S19 to S21). The ANE and AEA lineages themselves are estimated as having separated approximately 40 kya, relatively soon after the peopling of Eurasia by modern humans.

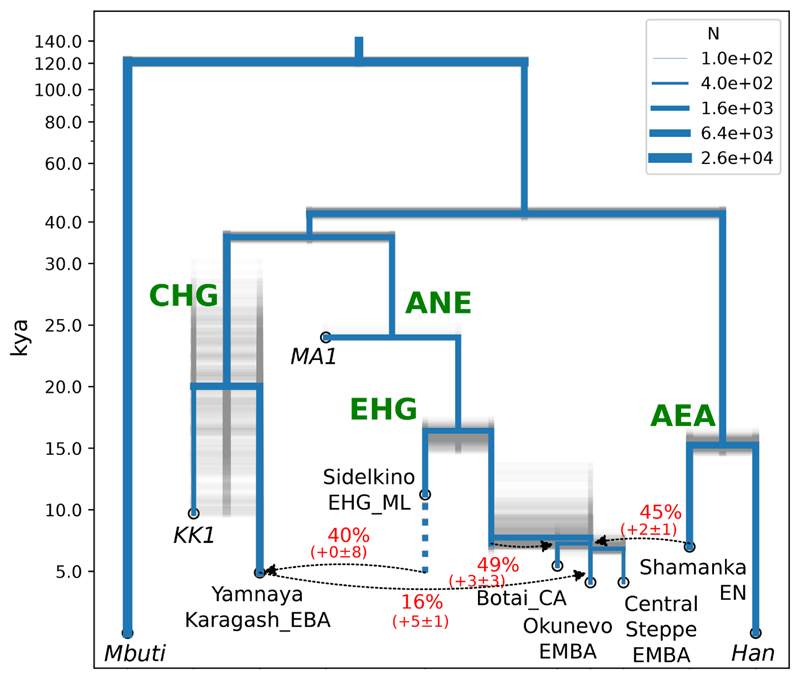

Fig. 4.

Demographic model of 10 populations inferred by maximizing the likelihood of the site frequency spectrum (implemented in momi).We used 300 parametric bootstrap simulations (shown in gray transparency) to estimate uncertainty. Bootstrap estimates for the bias and standard deviation of admixture proportions are listed beneath their point estimates. Note that the uncertainty may be underestimated here, due to simplifications or additional uncertainty in the model specification.

Since the ANE MA1 sample comes from the same cis-Baikal region as the AEA-derived Neolithic samples analyzed here, we thus document evidence for a population replacement between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic in this region. Furthermore, we observe a shift in genetic ancestry between the Early Neolithic (Baikal_EN) and the Late Neolithic / Bronze Age hunter-gatherers (Baikal_LNBA) (Fig. 2A), with the Baikal_LNBA cluster showing admixture from an ANE-related source. We estimate the ANE related ancestry in the Baikal_LNBA to be around ~5–11% (qpAdm; Table S12 (2)), using MA1 as a source of ANE, Baikal_EN as a source of AEA, and a set of 6 outgroups. However, neither MA1 nor any of the other steppe populations lie in the direction of Baikal_LNBA from Baikal_EN on the PCA plot (Fig. S23). This suggests that the new ANE ancestry in Baikal_LNBA stems from an unsampled source. Given that this source may have harbored East Asian ancestry, the contribution may be larger than 10%.

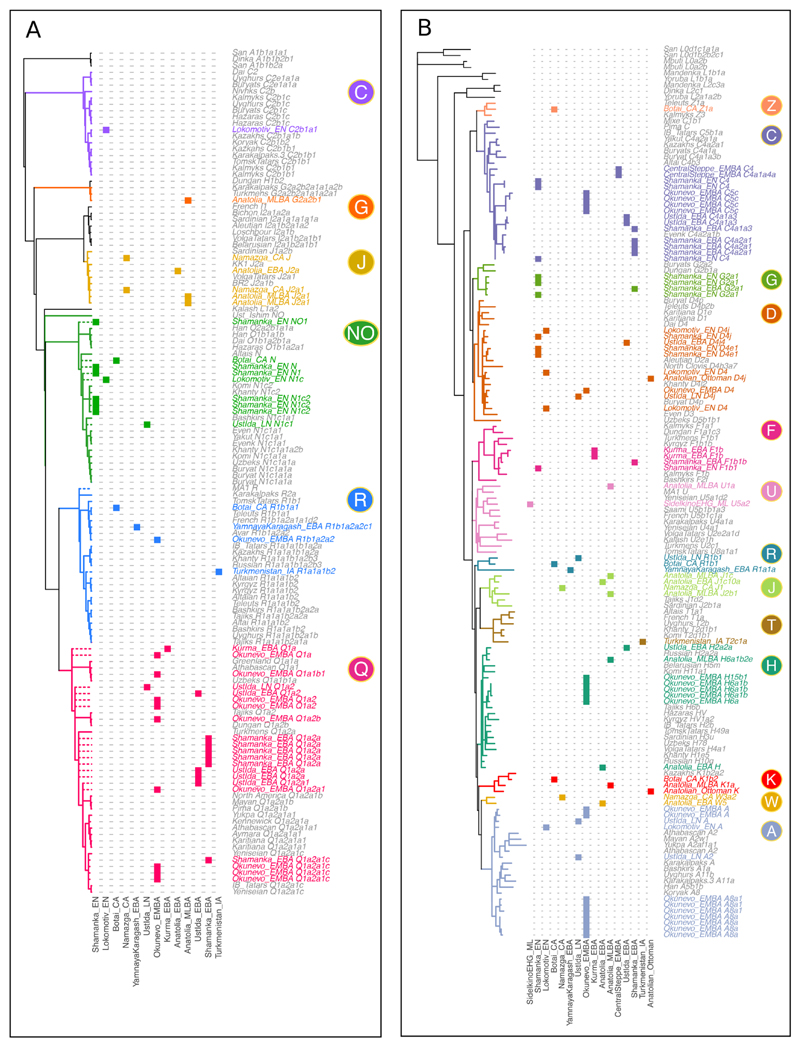

These serial changes in the Baikal populations are reflected in Y-chromosome lineages (Fig. 5A; Figs. S24 to S27; Tables S13 and S14). MA1 carries the R haplogroup, whereas the majority of Baikal_EN males belong to N lineages, which were widely distributed across Northern Eurasia (29), and the Baikal_LNBA males all carry Q haplogroups, as do most of the Okunevo_EMBA as well as some present-day Central Asians and Siberians. Mitochondrial haplogroups show less turnover (Fig. 5B; Table S15), which could either indicate male-mediated admixture or reflect bottlenecks in the male population.

Fig. 5.

Y-chromosome and mitochondrial lineages identified in ancient and present-day individuals. A) Maximum likelihood Y-chromosome phylogenetic tree estimated with data from 109 high coverage samples. Dashed lines represent the upper bound for the inclusion of 42 low coverage ancient samples in specific Y-chromosome clades on the basis of the lineages identified. B) Maximum likelihood mitochondrial phylogenetic tree estimated with 182 present-day and ancient individuals. The phylogenies displayed were restricted to a subset of clades relevant to the present work. Columns represent archaeological groups analyzed in the present study, ordered by time, and colored areas indicate membership of the major Y-chromosome and mtDNA haplogroups.

The deep population structure among the local populations in Inner Asia around the Copper Age / Bronze Age transition is in line with distinct origins of central steppe hunter-herders related to Botai of the central steppe and those related to Altaian hunter-gatherers of the eastern steppe (30). Furthermore, this population structure, which is best described as part of the “Ancient North Eurasian” metapopulation, persisted within Inner Asia from the Upper Paleolithic to the end of the Early Bronze Age. In the Baikal region the results show that at least two genetic shifts occurred: first, a complete population replacement of the Upper Paleolithic hunter-gatherers belonging to the “Ancient North Eurasians” by Early Neolithic communities of Ancient East Asian ancestry And second, an admixture event between the latter and additional members of the “Ancient North Eurasian” clade, occurring during the 1500-year period that separates the Neolithic from the Early Bronze Age. These genetic shifts complement previously observed severe cultural changes in the Baikal region (18–22).

Relevance for history of horse domestication

The earliest unambiguous evidence for horse husbandry is from the Copper Age Botai hunter-herder culture of the central steppe in Northern Kazakhstan around 3500–3000 BCE (5, 10, 23, 31–33). There was extensive debate over whether Botai horses were hunted or herded (33), but more recent studies have evidenced harnessing and milking (10, 17), the presence of likely corrals, and genetic domestication selection at the horse TRPM1 coat-color locus (32). Whilst horse husbandry has been demonstrated at Botai, it is also now clear from genetic studies this was not the source of modern domestic horse stock (32). Some have suggested that the Botai were local hunter-gatherers who learnt horse husbandry from an early eastward spread of western pastoralists, such as the Copper Age herders buried at Khvalynsk (~5150–3950 BCE), closely related to Yamnaya and Afanasievo (17). Others have suggested an in-situ transition from the local hunter-gatherer community (5).

We therefore examined the genetic relationship between Yamnaya and Botai. First, we note that whereas Yamnaya is best modelled as an approximately equal mix of EHG and Caucasian HG ancestry and that the earlier Khvalynsk samples from the same area also show Caucasian ancestry, the Botai_CA samples show no signs of admixture with a Caucasian source (Fig. S14). Similarly, while the Botai_CA have some Ancient East Asian ancestry, there is no sign of this in Khvalynsk or Yamnaya. Our momi model (Fig. 4) suggests that, although YamnayaKaragash_EBA shared ANE ancestry with Botai_CA from MA1 through EHG, their lineages diverge approximately 15,000 years ago in the Paleolithic. According to a parametric bootstrap, the amount of gene flow between YamnayaKaragash_EBA and Botai_CA inferred using the SFS was not significantly different from 0 (p-value 0.18 using 300 parametric bootstraps under a null model without admixture; Fig. S18). Additionally, the best-fitting SFS model without any recent gene flow fits the ratio of ABBA-BABA counts for (SidelkinoEHG_ML, YamnayaKaragash_EBA; Botai_CA, AncestralAllele), with Z-score = 0.45 using a block jackknife for this statistic. Consistent with this, a simple qpGraph model without direct gene flow between Botai_CA and Yamnaya, but with shared EHG-related ancestry between them, fits all f4 statistics (Fig. S28), and qpAdm (2) successfully fits models for Yamnaya ancestry without any Botai_CA contribution (Table S12).

The separation between Botai and Yamnaya is further reinforced by a lack of overlap in Y-chromosomal lineages (Fig. 5A). While our YamnayaKaragash_EBA sample carries the R1b1a2a2c1 lineage seen in other Yamnaya and present-day Eastern Europeans, one of the two Botai_CA males belongs to the basal N lineage, whose subclades have a predominantly Northern Eurasian distribution, while the second carries the R1b1a1 haplogroup, restricted almost exclusively to Central Asian and Siberian populations (34). Neither of these Botai lineages has been observed among Yamnaya males (Table S13; Fig. S25).

Using chromopainter (35) (Figs. S29 to S32) and rare variant sharing (36) (Figs. S33 to S35), we also identify a disparity in affinities with present-day populations between our high-coverage Yamnaya and Botai genomes. Consistent with previous results (1, 2), we observe a contribution from YamnayaKaragash_EBA to present-day Europeans. Conversely, Botai_CA shows greater affinity to Central Asian, Siberian, and Native American populations, coupled with some sharing with northeastern European groups at a lower level than that for Yamnaya, due to their ANE ancestry.

Further towards the Altai, the genomes of two CentralSteppe_EMBA women, who were buried in Afanasievo-like pit graves, revealed them to be representatives of an unadmixed Inner Asian ANE-related group, almost indistinguishable from the Okunevo_EMBA of the Minusinsk Basin north of the Altai through D-statistics (Fig. S11). This lack of genetic and cultural congruence may be relevant to the interpretation of Afanasievo-type graves elsewhere in Central Asia and Mongolia (37). However, in contrast to the lack of identifiable admixture from Yamnaya and Afanasievo in the CentralSteppe_EMBA, there is an admixture signal of 10–20% Yamnaya and Afanasievo in the Okunevo_EMBA samples (Fig. S21), consistent with evidence of western steppe influence. This signal is not seen on the X chromosome (qpAdm p-value for admixture on X 0.33 compared to 0.02 for autosomes), suggesting a male-derived admixture, also consistent with the fact that 1 of 10 Okunevo_EMBA males carries a R1b1a2a2 Y chromosome related to those found in western pastoralists (Fig. 5). In contrast, there is no evidence of western steppe admixture among the more eastern Baikal region Bronze Age (~2200–1800 BCE) samples (Fig. S14).

The lack of evidence of admixture between Botai horse herders and western steppe pastoralists is consistent with these latter migrating through the central steppe but not settling until they reached the Altai to the east (4). More significantly, this lack of admixture suggests that horses were domesticated by hunter-gatherers not previously familiar with farming, as were the cases for dogs (38) and reindeer (39). Domestication of the horse thus may best parallel that of the reindeer, a food animal that can be milked and ridden, which has been proposed to be domesticated by hunters via the “prey path” (40); indeed anthropologists note similarities in cosmological beliefs between hunters and reindeer herders (41). In contrast, most animal domestications were achieved by settled agriculturalists (5).

Origins of Western Eurasian genetic signatures in South Asians

The presence of Western Eurasian ancestry in many present-day South Asian populations south of the central steppe has been used to argue for gene flow from Early Bronze Age (~3000– 2500 BCE) western steppe pastoralists into the region (42, 43). However, direct influence of Yamnaya or related cultures of that period is not visible in the archaeological record, except perhaps for a single burial mound in Sarazm in present-day Tajikistan of contested age (44, 45). Additionally, linguistic reconstruction of proto-culture coupled with the archaeological chronology evidences a Late (~2300–1200 BCE) rather than Early Bronze Age (~3000–2500 BCE) arrival of the Indo-Iranian languages into South Asia (16, 45, 46). Thus, debate persists as to how and when Western Eurasian genetic signatures and IE languages reached South Asia.

To address these issues, we investigated whether the source of the Western Eurasian signal in South Asians could derive from sources other than Yamnaya and Afanasievo (Fig. 1). Both Early Bronze Age (~3000–2500 BCE) steppe pastoralists Yamnaya and Afanasievo and Late Bronze Age (~2300–1200 BCE) Sintashta and Andronovo carry substantial amounts of EHG and CHG ancestry (1, 2, 7), but the latter group can be distinguished by a genetic component acquired through admixture with European Neolithic farmers during the formation of the Corded Ware complex (1, 2), reflecting a secondary push from Europe to the east through the forest-steppe zone.

We characterized a set of 4 south Turkmenistan samples from Namazga period III (~3300 BCE). In our PCA analysis, the Namazga_CA individuals were placed in an intermediate position between Iran Neolithic and Western Steppe clusters (Fig. 2). Consistent with this, we find that the Namazga_CA individuals carry a significantly larger fraction of EHG-related ancestry than Neolithic skeletal material from Iran (D(EHG, Mbuti; Namazga_CA, Iran_N) Z = 4.49), and we are not able to reject a two-population qpAdm model in which Namazga_CA ancestry was derived from a mixture of Neolithic Iranians and EHG (~21%; p = 0.49).

Although CHG contributed both to Copper Age steppe individuals (e.g., Khvalynsk ~5150–3950 BCE) and substantially to Early Bronze Age (~3000–2500 BCE) steppe Yamnaya and Afanasievo (1, 2, 7, 47), we do not find evidence of CHG-specific ancestry in Namazga. Despite the adjacent placement of CHG and Namazga_CA on the PCA plot, D(CHG, Mbuti; Namazga_CA, Iran_N) does not deviate significantly from 0 (Z = 1.65), in agreement with ADMIXTURE results (Fig. 3; Fig. S14). Moreover, a three-population qpAdm model using Iran Neolithic, EHG, and CHG as sources yields a negative admixture coefficient for CHG. This suggests that while we cannot totally reject a minor presence of CHG ancestry, steppe-related admixture most likely arrived in the Namazga population prior to the Copper Age or from unadmixed sources related to EHG. This is consistent with the upper temporal boundary provided by the date of the Namazga_CA samples (~3300 BCE). In contrast, the Iron Age (~900–200 BCE) individual from the same region as Namazga (sample DA382, labelled Turkmenistan_IA) is closer to the steppe cluster in the PCA plot and does have CHG-specific ancestry. However, it also has European farmer-related ancestry typical of Late Bronze Age (~2300–1200 BCE) steppe populations (1–3, 47) (D(Neolithic European, Mbuti; Namazga_CA, Turkmenistan_IA) Z = -4.04), suggesting that it received admixture from Late (~2300–1200 BCE) rather than Early Bronze Age (~3000–2500 BCE) steppe populations.

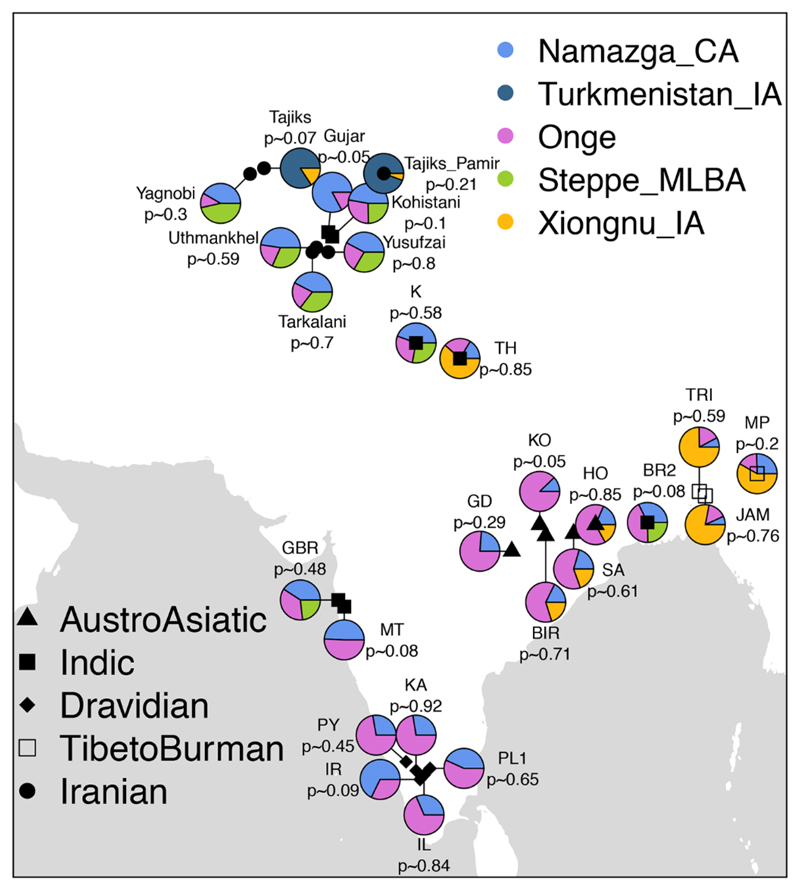

In a PCA focused on South Asia (Fig. 2B), the first dimension corresponds approximately to West-East and the second dimension to North-South. Near the lower right are the Andamanese Onge previously used to represent the “Ancient South Asian” component (12, 42). Contemporary South Asian populations are placed along both East-West and North-South gradients, reflecting the presence of three major ancestry components in South Asia deriving from “West Eurasians,” “South Asians,” and “East Asians.” Since the Namazga_CA individuals appear at one end of the West Eurasian / South Asian axis, and given their geographical proximity to South Asia, we tested this group as a potential source in a set of qpAdm models for the South Asian populations (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

A summary of the four qpAdm models fitted for South Asian populations. For each modern South Asian population, we fit different models with qpAdm to explain their ancestry composition using ancient groups and present the first model that we could not reject in the following priority order: 1. Namazga_CA + Onge, 2. Namazga_CA + Onge + Late Bronze Age Steppe, 3. Namazga_CA + Onge + Xiongnu_IA (East Asian proxy), and 4. Turkmenistan_IA + Xiongnu_IA. Xiongnu_IA were used here to represent East Asian ancestry. We observe that while South Asian Dravidian speakers can be modelled as a mixture of Onge and Namazga_CA, an additional source related to Late Bronze Age steppe groups is required for IE speakers. In Tibeto-Burman and Austro-Asiatic speakers, an East Asian rather than a Steppe_MLBA source is required.

We are not able to reject a two-population qpAdm model using Namazga_CA and Onge for 9 modern southern and predominantly Dravidian-speaking populations (Fig. 6; Fig. S36; Tables S16 and S17). In contrast, for 7 other populations belonging to the northernmost Indic- and Iranian-speaking groups this two-population model is rejected, but not a three-population model including an additional Late Bronze Age (~2300–1200 BCE) steppe source. Lastly, for 7 southeastern Asian populations, 6 of which were Tibeto-Burman or Austro-Asiatic speakers, the three-population model with Late Bronze Age (~2300–1200 BCE) steppe ancestry was rejected, but not a model in which Late Bronze Age (~2300–1200 BCE) steppe ancestry was replaced with an East Asian ancestry source, as represented by the Late Iron Age (~200 BCE–100 CE) Xiongnu (Xiongnu_IA) nomads from Mongolia (3). Interestingly, for two northern groups, the only tested model we could not reject included the Iron Age (~900–200 BCE) individual (Turkmenistan_IA) from the Zarafshan Mountains and the Xiongnu_IA as sources. These findings are consistent with the positions of the populations in PCA space (Fig. 2B), and further supported by ADMIXTURE analysis (Fig. 3) with two minor exceptions: in both the Iyer and the Pakistani Gujar we observe a minor presence of the Late Bronze Age (~2300–1200 BCE) steppe ancestry component (Fig. S14) not detected by the qpAdm approach. Additionally, we document admixture along the “West Eurasian” and “East Asian” clines of all South Asian populations using D-statistics (Fig. S37).

Thus, we find that ancestries deriving from 4 major separate sources fully reconcile the population history of present-day South Asians (Figs. 3 and 6), one anciently South Asian, one from Namazga or a related population, a third from Late Bronze Age (~2300–1200 BCE) steppe pastoralists, and lastly one from East Asia. They account for western ancestry in some Dravidian populations that lack CHG-specific ancestry while also fitting the observation that whenever there is CHG-specific ancestry and considerable EHG ancestry there is also European Neolithic ancestry (Fig. 3). This implicates Late Bronze Age (~2300–1200 BCE) steppe rather than Early Bronze Age (~3000–2500 BCE) Yamnaya and Afanasievo admixture into South Asia. The proposal that the IE steppe ancestry arrived in the Late Bronze Age (~2300–1200 BCE) is also more consistent with archaeological and linguistic chronology (44, 45, 48, 49). Thus, it seems that the Yamnaya- and Afanasievo-related migrations did not have a direct genetic impact in South Asia.

Lack of steppe genetic impact in Anatolians

Finally, we consider the evidence for Bronze Age steppe genetic contributions in West Asia. There are conflicting models for the earliest dispersal of IE languages into Anatolia (4, 50). The now extinct Bronze Age Anatolian language group represents the earliest historically attested branch of the IE language family and is linguistically held to be the first branch to have split off from PIE (53, 54, 58). One key question is whether Proto-Anatolian is a direct linguistic descendant of the hypothesized Yamnaya PIE language or whether Proto-Anatolian and the PIE language spoken by Yamnaya were branches of a more ancient language ancestral to both (49, 53). Another key question relates to whether Proto-Anatolian speakers entered Anatolia as a result of a “Copper Age western steppe migration” (~5000–3000 BCE) involving movement of groups through the Balkans into Northwest Anatolia (4, 71, 73), or a “Caucasian” route that links language dispersal to intensified north-south population contacts facilitated by the trans-Caucasian Maykop culture around 3700–3000 BCE (50, 54).

Ancient DNA findings suggest extensive population contact between the Caucasus and the steppe during the Copper Age (~5000–3000 BCE) (1, 2, 42). Particularly, the first identified presence of Caucasian genomic ancestry in steppe populations is through the Khvalynsk burials (2, 47) and that of steppe ancestry in the Caucasus is through Armenian Copper Age individuals (42). These admixture processes likely gave rise to the ancestry that later became typical of the Yamnaya pastoralists (7), whose IE language may have evolved under the influence of a Caucasian language, possibly from the Maykop culture (50, 55). This scenario is consistent with both the “Copper Age steppe” (4) and the “Caucasian” models for the origin of the Proto-Anatolian language (56).

The PCA (Fig. 2B) indicates that all the Anatolian genome sequences from the Early Bronze Age (~2200 BCE) and Late Bronze Age (~1600 BCE) cluster with a previously sequenced Copper Age (~3900–3700 BCE) individual from Northwestern Anatolia and lie between Anatolian Neolithic (Anatolia_N) samples and CHG samples but not between Anatolia_N and EHG samples. A test of the form D(CHG, Mbuti; Anatolia_EBA, Anatolia_N) shows that these individuals share more alleles with CHG than Neolithic Anatolians do (Z = 3.95), and we are not able to reject a two-population qpAdm model in which these groups derive ~60% of their ancestry from Anatolian farmers and ~40% from CHG-related ancestry (p-value = 0.5). This signal is not driven by Neolithic Iranian ancestry, since the result of a similar test of the form D(Iran_N, Mbuti; Anatolia_EBA, Anatolia_N) does not deviate from zero (Z = 1.02). Taken together with recent findings of CHG ancestry on Crete (57), our results support a widespread CHG-related gene flow, not only into Central Anatolia but also into the areas surrounding the Black Sea and Crete. The latter are not believed to have been influenced by steppe-related migrations and may thus correspond to a shared archaeological horizon of trade and innovation in metallurgy (66).

Importantly, a test of the form D(EHG, Mbuti; Anatolia_EBA, Anatolia_MLBA) supports that the Central Anatolian gene pools, including those sampled from settlements thought to have been inhabited by Hittite speakers, were not impacted by steppe populations during the Early and Middle Bronze Age (Z = -1.83). Both of these findings are further confirmed by results from clustering analysis (Fig. 3). The CHG-specific ancestry and the absence of EHG-related ancestry in Bronze Age Anatolia would be in accordance with intense cultural interactions between populations in the Caucasus and Anatolia observed during the late 5th millennium BCE that seem to come to an end in the first half of the 4th millennium BCE with the village-based egalitarian Kura-Araxes’ society (59, 60), thus preceding the emergence and dispersal of Proto-Anatolian.

Our results indicate that the early spread of IE languages into Anatolia was not associated with any large-scale steppe-related migration, as previously suggested (61). Additionally, and in agreement with the later historical record of the region (62), we find no correlation between genetic ancestry and exclusive ethnic or political identities among the populations of Bronze Age Central Anatolia, as has previously been hypothesized (63).

Discussion

For Europe, ancient genomics have revealed extensive population migrations, replacements, and admixtures from the Upper Paleolithic to the Bronze Age (1, 2, 27, 64, 65), with a strong influence across the continent from the Early Bronze Age (~3000–2500 BCE) western steppe Yamnaya. In contrast, for Central Asia, continuity is observed from the Upper Paleolithic to the end of the Copper Age (~3500–3000 BCE), with descendants of Paleolithic hunter-gatherers persisting as largely isolated populations after the Yamnaya and Afanasievo pastoralist migrations. Instead of western pastoralists admixing with or replacing local groups, we see groups with East Asian ancestry replacing ANE populations in the Lake Baikal region. Thus, unlike in Europe, the hunter/gathering/herding groups of Inner Asia were much less impacted by the Yamnaya and Afanasievo expansion. This may be due to the rise of early horse husbandry, likely initially originated through a local “prey route” (40) adaptation by horse-dependent hunter-gatherers at Botai. Since work on ancient horse genomes (32) indicates that Botai horses were not the main source of modern domesticates, this suggests the existence of a second center of domestication, but whether this second center was associated with the Yamnaya and Afanasievo cultures remains uncertain in the absence of horse genetic data from their sites.

Our finding that the Copper Age (~3300 BCE) Namazga-related population from the borderlands between Central and South Asia contains both “Iran Neolithic” and EHG ancestry but not CHG-specific ancestry provides a solution to problems concerning the Western Eurasian genetic contribution to South Asians. Rather than invoking varying degrees of relative contribution of “Iran Neolithic” and Yamnaya ancestries, we explain the two western genetic components with two separate admixture events. The first event, potentially prior to the Bronze Age, spread from a non-IE-speaking farming population from the Namazga culture or a related source down to Southern India. Then the second came during the Late Bronze Age (~2300–1200 BCE) through established contacts between pastoral steppe nomads and the Indus Valley, bringing European Neolithic as well as CHG-specific ancestry, and with them Indo-Iranian languages into northern South Asia. This is consistent with a long-range South Eurasian trade network around 2000 BCE (4), shared mythologies with steppe-influenced cultures (41, 60), linguistic relationships between Indic spoken in South Asia, and written records from Western Asia from the first half of the 18th century BCE onwards (49, 52).

In Anatolia, our samples do not genetically distinguish Hittite and other Bronze Age Anatolians from an earlier Copper Age sample (~3943-3708 BCE). All these samples contain a similar level of CHG ancestry but no EHG ancestry. This is consistent with Anatolian / Early European farmer ancestry, but not steppe ancestry, in the Copper Age Balkans (67) and implies that the Anatolian clade of IE languages did not derive from a large-scale Copper Age / Early Bronze Age population movement from the steppe (contra (4)). Our findings are thus consistent with historical models of cultural hybridity and “Middle Ground” in a multi-cultural and multi-lingual but genetically homogenous Bronze Age Anatolia (68, 69).

Current linguistic estimations converge on dating the Proto-Anatolian split from residual PIE to the late 5th or early 4th millennia BCE (58, 70) and place the breakup of Anatolian IE inside Turkey prior to the mid-3rd millennium (53, 71, 72). In (49) we present new onomastic material (51) that pushes the period of Proto-Anatolian linguistic unity even further back in time. We cannot at this point reject a scenario in which the introduction of the Anatolian IE languages into Anatolia was coupled with the CHG-derived admixture prior to 3700 BCE, but note that this is contrary to the standard view that PIE arose in the steppe north of the Caucasus (4) and that CHG ancestry is also associated with several non-IE-speaking groups, historical and current. Indeed, our data are also consistent with the first speakers of Anatolian IE coming to the region by way of commercial contacts and small-scale movement during the Bronze Age. Among comparative linguists, a Balkan route for the introduction of Anatolian IE is generally considered more likely than a passage through the Caucasus, due, for example, to greater Anatolian IE presence and language diversity in the west (73). Further discussion of these options is given in the archaeological and linguistic supplementary discussions (48, 49).

Thus, while the “Steppe hypothesis,” in the light of ancient genomics, has so far successfully explained the origin and dispersal of IE languages and culture in Europe, we find that several elements must be re-interpreted to account for Asia. First, we show that the earliest unambiguous example of horse herding emerged amongst hunter-gatherers, who had no significant genetic interaction with western steppe herders. Second, we demonstrate that the Anatolian IE language branch, including Hittite, did not derive from a substantial steppe migration into Anatolia. And third, we conclude that Early Bronze Age steppe pastoralists did not migrate into South Asia but that genetic evidence fits better with the Indo-Iranian IE languages being brought to the region by descendants of Late Bronze Age steppe pastoralists.

Supplementary Materials

One Sentence Summary.

We investigate the origins of Indo-European languages in Asia by coupling ancient genomics to archaeology and linguistics.

Introduction

According to the commonly accepted “Steppe Hypothesis,” the initial spread of Indo-European (IE) languages into both Europe and Asia took place with migrations of Early Bronze Age Yamnaya pastoralists from the Pontic–Caspian steppe. This is believed to have been enabled by horse domestication, which revolutionized transport and warfare. While in Europe there is much support for the Steppe Hypothesis, the impact of Western steppe pastoralists in Asia, including Anatolia, remains less well understood, with limited archaeological evidence for their presence. Furthermore, the earliest secure evidence of horse husbandry comes from the Botai culture of Central Asia, while direct evidence for Yamnaya equestrianism remains elusive.

Rationale

We investigate the genetic impact of Early Bronze Age migrations into Asia and interpret our findings in relation to the Steppe Hypothesis and early spread of IE languages. We generated whole-genome shotgun sequence data (~1-25 X average coverage) for 74 ancient individuals from Inner Asia and Anatolia as well as 41 high-coverage present-day genomes from 17 Central Asian ethnicities.

Results

We show that the population at Botai associated with the earliest evidence for horse husbandry derived from an ancient hunter-gatherer ancestry previously seen in the Upper Paleolithic Mal’ta (MA1), and was deeply diverged from the Western steppe pastoralists. They form part of a previously undescribed west-to-east cline of Holocene prehistoric steppe genetic ancestry in which Botai, Central Asians, and Baikal groups can be modeled with different amounts of Eastern hunter-gatherer (EHG) and Ancient East Asian (AEA) genetic ancestry represented by Baikal_EN.

In Anatolia, Bronze Age samples, including from Hittite speaking settlements associated with the first written evidence of IE languages, show genetic continuity with preceding Anatolian Copper Age (CA) samples and have substantial Caucasian hunter-gatherer (CHG)-related ancestry but no evidence of direct steppe admixture.

In South Asia, we identify at least two distinct waves of admixture from the west: the first occurring from a source related to the Copper Age Namazga farming culture from the southern edge of the steppe, the second by Late Bronze Age steppe groups into the northwest of the subcontinent.

Conclusions

Our findings reveal that the early spread of Yamnaya Bronze Age pastoralists had limited genetic impact in Anatolia as well as Central and South Asia. As such, the Asian story of Early Bronze Age expansions differs from that of Europe. Intriguingly, we find that direct descendants of Upper Paleolithic hunter-gatherers of Central Asia, now extinct as a separate lineage, survived well into the Bronze Age. These groups likely engaged in early horse domestication as a prey-route transition from hunting to herding, as otherwise seen for reindeer. Our findings further suggest that West Eurasian ancestry entered South Asia before and after, rather than during, the initial expansion of western steppe pastoralists, with the later event consistent with a Late Bronze Age entry of IE languages into South Asia. Finally, the lack of steppe ancestry in samples from Anatolia indicates that the spread of IE languages into that region was not associated with a steppe migration.

Figure Caption.

Model-based admixture proportions for selected ancient and present-day individuals, assuming k=6, shown with their corresponding geographical locations. Ancient groups are represented by larger admixture plots with those sequenced in the present work surrounded by black borders, and others used for providing context with blue borders. Present-day South Asian groups are represented by smaller admixture plots with dark grey borders.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kim Magnussen, Lillian Petersen, Cecilie Mortensen, and Andaine Seguin Orlando at the Danish National Sequencing Centre for conducting the sequencing, Paula Reimer and Stephen Hoper at the 14Chrono Center Belfast for providing the AMS dating. We thank Sturla Ellingvåg, Bettina Elisabeth Heyerdahl, and the Explico-Historical Research Foundation team as well as Niobe Thompson for involvement in field work. We thank the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Kaman-Kalehöyük Archaeology Museum, and Nevşehir Museum for the permission to samples of Kaman-Kalehöyük and Ovaören. We thank Jesper Stenderup, Pernille V. Olsen, and Tina Brand for technical assistance in the laboratory. We thank Thorfinn Korneliussen for helpful discussions. We thank the St. Johns College in Cambridge for providing the settings for fruitful scientific discussions. We thank all involved archaeologists, historians, and collaborators from Pakistan who assisted IU in the field. We thank Gabit Baimbetov (Shejire DNA), Ilyas Baimukhan, Batyr Daulet, Adbul Kusaev, Ainur Kopbassarova, Youldash Yousupov, Maksum Akchurin, and Vladimir Volkov for important assistance in the field.

Funding: The study was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation (EW), the Danish National Research Foundation (EW), and KU2016 (EW). Research at the Sanger Institute was supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant 206194). RM was supported by an EMBO Long-Term Fellowship (ALTF 133-2017). JK was supported by the Human Frontiers Science Program (LT000402/2017). Botai fieldwork was supported by University of Exeter, Archaeology Exploration Fund and Niobe Thompson, Clearwater Documentary. AB was supported by NIH grant 5T32GM007197-43. GK was funded by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond and European Research Council. MP was funded by Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), project number 276-70-028, IU was funded by the Higher education commission of Pakistan. Archaeological materials from Sholpan and Grigorievka were obtained with partial financial support of the budget program of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan “Grant financing of scientific research for 2018-2020” No. AP05133498 “Early Bronze Age of the Upper Irtysh”.

Footnotes

Author contributions: EW, KK, AO, and AW: initiated the study. EW, RD, KK, AO, and PBD: designed the study. EW and RD: led the study. KK and AO: led the archaeological part of the study. GK, MP, and GB: led the linguistic part of the study. PBD, CZ, FEY, IU, CdF, MI, HS, ASO, and MEA: produced data. PBD, RM, JK, JVMM, SR, KHI, MS, RN, AB, JN, EW, and RD: analyzed or assisted in analysis of data. PBD, RM, JK, JVMM, RD, EW, AO, KK, GK, MP, GB, BH, MS, and RN: interpreted the results. PBD, EW, RM, RD, AO, GK, JK, GB, JVMM, KK, and MP: wrote the manuscript with considerable input from BH, MS, MEA, and RN. PBD, VZ, VM, IM, NB, EU, VL, FEY, IU, AM, KGS, VM, AG, SO, SYS, CM, HA, AH, AS, NG, MHK, AW, LO, and AO: excavated, curated, sampled and/or described analyzed skeletons.

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: Genomic data are available for download at the ENA (European Nucleotide Archive) with accession numbers ERP107300 and PRJEB26349. Novel SNP array data from Pakistan can be obtained from EGA through the accession number EGAS00001002965. Y-chromosome and mtDNA data are available at Zenodo under DOI 10.5281/zenodo.1219431.

References

- 1.Allentoft ME, Sikora M, Sjögren K-G, Rasmussen S, Rasmussen M, Stenderup J, Damgaard PB, Schroeder H, Ahlström T, Vinner L, Malaspinas AS, et al. Population genomics of bronze age Eurasia. Nature. 2015;522:167–172. doi: 10.1038/nature14507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haak W, Lazaridis I, Patterson N, Rohland N, Mallick S, Llamas B, Brandt G, Nordenfelt S, Harney E, Stewardson K, Fu Q, et al. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature. 2015;522:207–211. doi: 10.1038/nature14317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damgaard PB, Marchi N, Rasmussen S, Peyrot M, Renaud G, Korneliussen Th, Moreno-Mayar JV, Pedersen MW, Goldberg A, Usmanova E, Baimukhanov N, et al. 137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppe. Nature. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2. (accepted) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anthony DW. The horse, the wheel, and language: how Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian steppes shaped the modern world. Princeton University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Outram AK. In: The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Hunter-Gatherers. Cummings V, Jordan P, Zvelebil M, editors. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2014. pp. 749–766. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mallory JP. In search of the Indo-Europeans: language, archaeology and myth. Thames & Hudson; London: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones ER, Gonzalez-Fortes G, Connell S, Siska V, Eriksson A, Martiniano R, McLaughlin RL, Gallego Llorente M, Cassidy LM, Gamba C, Meshveliani T, et al. Upper Palaeolithic genomes reveal deep roots of modern Eurasians. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8912. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mallory JP, Adams DQ. The Oxford introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European world. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kristiansen K, Allentoft ME, Frei KM, Iversen R, Johannsen NN, Kroonen G, Pospieszny Ł, Price TD, Rasmussen S, Sjögren K-G, Sikora M, et al. Re-theorising mobility and the formation of culture and language among the Corded Ware Culture in Europe. Antiquity. 2017;91:334–347. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Outram AK, Stear NA, Bendrey R, Olsen S, Kasparov A, Zaibert V, Thorpe N, Evershed RP. The earliest horse harnessing and milking. Science. 2009;323:1332–1335. doi: 10.1126/science.1168594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaiser E. Der Übergang zur Rinderzucht im nördlichen Schwarzmeerraum. Godišnjak Centar za balkanološka ispitivanja. 2010;39:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reich D, Thangaraj K, Patterson N, Price AL, Singh L. Reconstructing Indian population history. Nature. 2009;461:489–494. doi: 10.1038/nature08365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristiansen K. Europe before History. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.See Supplementary Online Materials

- 15.Outram AK, Polyakov A, Gromov A, Moiseyev V, Weber AW, Bazaliiskii VI, Goriunova OI. Supplementary discussion of the archaeology of Central Asian and East Asian Neolithic to Bronze Age hunter-gatherers and early pastoralists, including consideration of horse domestication. bioRxiv. 2018 DOI XXX. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evdokimov VV, Loman VG. Voprosy arheologii Central'nogo i Severnogo Kazahstana. Karaganda: 1989. Raskopki yamnogo kurgana v Karagandinskoj oblasti; pp. 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anthony DW, Brown DR. The secondary products revolution, horse-riding, and mounted warfare. J World Prehist. 2011;24:131–160. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazaliiskii VI. In: Prehistoric foragers of the cis-Baikal, Siberia. Weber A, McKenzie H, editors. Vol. 1 Northern Hunter-Gatherers Research Series, Canadian Circumpolar Institute Press; Edmonton: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bazaliiskii VI. In: Prehistoric hunter-gatherers of the Baikal region, Siberia: bioarchaeological studies of past life ways. Weber A, Katzenberg MA, Schurr TG, editors. University of Pennsylvania Press; Philadelphia: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber A. Social evolution among neolithic and early bronze age foragers in the Lake Baikal region: new light on old models. Arctic Anthropol. 1994;31:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber A. The Neolithic and Early Bronze Age of the Lake Baikal Region: a review of recent research. J World Prehist. 1995;9:99–165. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber A, Baziliiskii VI. Mortuary practices and social relations among the Neolithic foragers of the Angara and Lake Baikal region: retrospection and prospection. In: Meyer DA, Dawson PC, Hanna DT, editors. Debating complexity: proceedings of the 26th annual conference of the Archaeological Association of the University of Calgary; Calgary: University of Calgary; pp. 97–103. 1003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaibert VF. Botaiskaya Kultura. KazAkparat; Almaty: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Svyatko SV, Mallory JP, Murphy EM, Polyakov AV, Reimer PJ, Schulting RJ. New radiocarbon dates and a review of the chronology of prehistoric populations from the Minusinsk basin, southern Siberia, Russia. Radiocarbon. 2009;51:243–273. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siska V, Jones ER, Jeon S, Bhak Y, Kim H-M, Cho YS, Kim H, Lee K, Veselovskaya E, Balueva T, Gallego-Llorente M, et al. Genome-wide data from two early Neolithic East Asian individuals dating to 7700 years ago. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1601877. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1601877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raghavan M, Skoglund P, Graf KE, Metspalu M, Albrechtsen A, Moltke I, Rasmussen S, Stafford TW, Jr, Orlando L, Metspalu E, Karmin M, et al. Upper Palaeolithic Siberian genome reveals dual ancestry of Native Americans. Nature. 2014;505:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature12736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fu Q, Posth C, Hajdinjak M, Petr M, Mallick S, Fernandes D, Furtwängler A, Haak W, Meyer M, Mittnik A, Nickel B, et al. The genetic history of Ice Age Europe. Nature. 2016;534:200–205. doi: 10.1038/nature17993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamm JA, Terhorst J, Song YS. Efficient computation of the joint sample frequency spectra for multiple populations. J Comput Graph Stat. 2017;26:182–194. doi: 10.1080/10618600.2016.1159212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ilumäe A-M, Reidla M, Chukhryaeva M, Järve M, Post H, Karmin M, Saag L, Agdzhoyan A, Kushniarevich A, Litvinov S, Ekomasova N, et al. Human Y Chromosome Haplogroup N: A Non-trivial Time-Resolved Phylogeography that Cuts across Language Families. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kovaleva VT, Chairkina NM. Voprosy arkheologii Urala. Uralskii gosudarstvenyi universitet; Ekaterinburg: 1991. Etnokul’turnye i etnogeneticheskie protsessy v severnem zaurale v kontse kamennogo–nachale bronzovogo veka: Itogi i problemy issledovaniya; pp. 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anthony DW, Brown DR. The secondary products revolution, horse-riding, and mounted warfare. J World Prehist. 2011;24:131–160. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaunitz C, Fages A, Hanghøj K, Albrechtsen A, Khan N, Schubert M, Seguin-Orlando A, Owens IJ, Felkel S, Bignon-Lau O, de Barros Damgaard P, et al. Ancient genomes revisit the ancestry of domestic and Przewalski’s horses. Science. 2018 doi: 10.1126/science.aao3297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olsen SL, Grant S, Choyke AM, Bartosiewicz L. Horses and humans: the evolution of human-equine relationships. British Archeological Reports; Oxford: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myres NM, Rootsi S, Lin AA, Järve M, King RJ, Kutuev I, Cabrera VM, Khusnutdinova EK, Pshenichnov A, Yunusbayev B, Balanovsky O, et al. A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b Holocene era founder effect in Central and Western Europe. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:95–101. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawson DJ, Hellenthal G, Myers S, Falush D. Inference of population structure using dense haplotype data. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schiffels S, Haak W, Paajanen P, Llamas B, Popescu E, Loe L, Clarke R, Lyons A, Mortimer R, Sayer D, Tyler-Smith C, et al. Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon genomes from East England reveal British migration history. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms10408. 10408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovalev AA, Erdenebaatar D. Discovery of new cultures of the Bronze Age in Mongolia according to the data obtained by the International Central Asian Archaeological Expedition. In: Bemmann J, Parzinger H, Pohl E, Tseveendorzh D, editors. Current Archaeoligcal Research in Mongolia. Vor- und Frühgeschichtliche Archäologie Uni-Bonn; Bonn: 2009. pp. 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larson G, Karlsson EK, Perri A, Webster MT, Ho SYW, Peters J, Stahl PW, Piper PJ, Lingaas F, Fredholm M, Comstock KE, et al. Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8878–8883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203005109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Røed KH, Flagstad O, Nieminen M, Holand O, Dwyer MJ, Røv N, Vilà C. Genetic analyses reveal independent domestication origins of Eurasian reindeer. Proc Biol Sci. 2008;275:1849–1855. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeder MA. Pathways to animal domestication. Biodivers Agric Domest Evol Sustain. 2012:227–259. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willerslev R, Vitebsky P, Alekseyev A. Sacrifice as the ideal hunt: a cosmological explanation for the origin of reindeer domestication. J R Anthropol Inst. 2015;21:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lazaridis I, Nadel D, Rollefson G, Merrett DC, Rohland N, Mallick S, Fernandes D, Novak M, Gamarra B, Sirak K, Connell S, et al. Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East. Nature. 2016;536:419–424. doi: 10.1038/nature19310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Basu A, Sarkar-Roy N, Majumder PP. Genomic reconstruction of the history of extant populations of India reveals five distinct ancestral components and a complex structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:1594–1599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513197113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Francfort H-P. L’âge du bronze en Asie centrale: La civilisation de l’Oxus. Anthropol Middle East. 2009;4:91–111. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuz mina EE. The origin of the Indo-Iranians. Brill; Leiden: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parpola A. The roots of Hinduism: the early Aryans and the Indus civilization. Oxford University Press; USA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mathieson I, Lazaridis I, Rohland N, Mallick S, Patterson N, Roodenberg SA, Harney E, Stewardson K, Fernandes D, Novak M, Sirak K, et al. Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature. 2015;528:499–503. doi: 10.1038/nature16152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kristiansen K, Hemphill B, Barjamovic G, Omura S, Senyurt SY, Moiseyev V, Gromov A, Yediay FE, Ahmad H, Hameed A, Samad A, et al. Archaeological supplement A to Damgaard et al. 2018: Archaeology of the Caucasus, Anatolia, Central and South Asia 4000-1500 BCE. bioRxiv. 2018 DOI XXX. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kroonen G, Barjamovic G, Peyrot M. Linguistic supplement to Damgaard et al. 2018: Early Indo-European Languages, Anatolian, Tocharian and Indo-Iranian. bioRxiv. 2018 DOI XXX. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kristiansen K, Larsson TB. The rise of Bronze Age society: travels, transmissions and transformations. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bonechi M. Aleppo in età arcaica. A proposito di un’opera recente. SEL. 1990;7:15–37. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mayrhofer M. Die Indo-Arier im alten Vorderasien: mit einer analytischen Bibliographie. Harrassowitz; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Melchert HC. The dialectal position of Anatolian within Indo-European. Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society; 1998. pp. 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Puhvel J. Whence the Hittite, whither the Jonesian vision? In: Lamb SM, Mitchell ED, editors. Sprung from a common source. Stanford University Press; Stanford, Calif: 1991. pp. 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kortlandt F. CC Uhlenbeck on Indo-European, Uralic and Caucasian. Hist Sprachforsch. 2009;122:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Winn SM. Burial evidence and the kurgan culture in Eastern Anatolia c. 3000 BC: An interpretation. J Indo-Eur Stud Wash DC. 1981;9:113–118. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lazaridis I, Mittnik A, Patterson N, Mallick S, Rohland N, Pfrengle S, Furtwängler A, Peltzer A, Posth C, Vasilakis A, McGeorge PJP, et al. Genetic origins of the Minoans and Mycenaeans. Nature. 2017;548:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature23310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Darden B. On the question of the Anatolian origin of Indo-Hittite. In: Drews R, editor. Greater Anatolia and the Indo-Hittite language family. Journal of Indo-European Studies; Washington: 2001. pp. 184–228. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith AT. The political machine: assembling sovereignty in the Bronze Age Caucasus. Princeton University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sagona A. The Archaeology of the Caucasus: From Earliest Settlements to the Iron Age. Cambridge University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burney C, Lang DM. The Peoples of the Hills: Ancient Ararat and Caucasus. Weidenfeld and Nicolson; London: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Larsen MT. Ancient Kanesh: A merchant colony in bronze age Anatolia. Cambridge University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Forlanini M. An attempt at reconstructing the branches of the Hittite royal family of the Early Kingdom period. In: Cohen Y, Gilan A, Miller JL, editors. Pax Hethitica: Studies on the Hittites and their neighbours in honour of Itamar Singer. Harrasowitz; Wiesbaden: 2010. p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Skoglund P, Malmström H, Omrak A, Raghavan M, Valdiosera C, Günther T, Hall P, Tambets K, Parik J, Sjögren K-G, Apel J, et al. Genomic diversity and admixture differs for Stone-Age Scandinavian foragers and farmers. Science. 2014;344:747–750. doi: 10.1126/science.1253448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lazaridis, Patterson N, Mittnik A, Renaud G, Mallick S, Kirsanow K, Sudmant PH, Schraiber JG, Castellano S, Lipson M, Berger B, et al. Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature. 2014;513:409–413. doi: 10.1038/nature13673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rahmstorf L. Indications of Aegean-Caucasian relations during the third millennium BC. In: Hansen S, Hauptmann A, Motzenbäcker I, Pernicka E, editors. Von Maikop bis Trialeti. Gewinnung und Verbreitung von Metallen und Obsidian in Kaukasien im 4-2 Jt v Chr. Verlag Rudolf Habelt; Bonn: 2010. pp. 263–295. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mathieson I, Alpaslan-Roodenberg S, Posth C, Szécsényi-Nagy A, Rohland N, Mallick S, Olalde I, Broomandkhoshbacht N, Candilio F, Cheronet O, Fernandes D, et al. The genomic history of southeastern Europe. Nature. 2018;555:197–203. doi: 10.1038/nature25778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lumsden S. Old Assyrian studies in memory of Paul Garelli. Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije; Oosten: 2008. Material culture and the Middle Ground in the Old Assyrian Colony period; pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Larsen MT, Lassen AW. Extraction and control: studies in honor of Matthew W Stolper. Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago; 2014. Cultural exchange at Kültepe; pp. 171–88. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lehrman A. Reconstructing Proto-Indo-Hittite. In: Drews R, editor. Greater Anatolia and the Indo-Hittite Language Family. Vol. 38. Journal of Indo-European Studies monographs; 2001. pp. 106–130. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Watkins C. An Indo-European linguistic area and its characteristics: Anatolia. In: Aikhenvald AY, Dixon RMW, editors. Areal diffusion and genet inheritance: problems in comparative linguistics. Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 44–63. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oettinger N. Indogermanische Sprachträger lebten schon im 3. Jahrtausend v. Chr. in Kleinasien. In: Özgüç T, editor. Die Hethiter und ihr Reich: das Volk der 1000 Götter. Stuttgart: Theiss; 2002. pp. 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Melchert HC, editor. The Luwians. Brill; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 74.McKinley J. Compiling a skeletal inventory: disarticulated and co-mingled remains. In: Brickley M, McKinley J, editors. Guidelines to the Standards for Recording Human Remains. BABAO and IFA: Reading; 2004. pp. 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schwartz JH. Skeleton Keys: An Introduction to Human Skeletal Morphology, Development and Analysis. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Phenice TW. A newly developed visual method of sexing the os pubis. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1969;30:297–301. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330300214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ferembach D, Schwindezky I, Stoukal M. Recommendations for age and sex diagnoses of skeletons. J Hum Evol. 1980;9:517–549. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Loth SR, Henneberg M. Mandibular ramus flexure: a morphologic indicator of sexual dimorphism in the human skeleton. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1996;99:473–485. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199603)99:3<473::AID-AJPA8>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brooks ST, Suchey JM. Skeletal age determination based on the os pubis: a comparison of the Acsádi-Nemeskéri and Suchey-Brooks methods. Hum Evol. 1990;5:227–238. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lovejoy CO, Meindl RS, Pryzbeck TR, Mensforth RP. Chronological metamorphosis of the auricular surface of the ilium: A new method for the determination of age at death. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1985;68:15–28. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330680103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brothwell DR. Digging up Bones. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Trotter M. Estimation of stature from intact long bones. In: Stewart TD, editor. Personal Identification in Mass Disasters. Smithsonian Institution; Washington: 1970. pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mertz IV, Mertz VK. Novye materialy rannego bronzovogo veka iz Zapadnoj chasti Kulundinskoj ravniny. In: Kubareva GA, Semibratov VP, editors. Sohranenie i izuchenie kul'turnogo nasledija Altajskogo kraja: materialy XVIII XIX regional'nyh nauchno-prakticheskih konferencij. Azbuka; Barnaul: 2013. pp. 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Merz VK, Merz Pogrebeniya IV. ‘yamnogo’ tipa Vostochnogo i Severo-Vostochnogo Kazakhstana (k postanovke problemy) In: Stepanova NF, Polyakov AV, Tur SS, Shulga PI, editors. Afanasyevskiy Sbornik. Azbuka; Barnaul: 2010. pp. 134–144. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Maksimenkov GA. Okunevskaya Kultura. thesis abstract, Institute of History, Philology and Philosophy; Novosibirsk: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lazaretov IP. K voprosu o yamno-katakombnyh svyazyah okunevskoy kul’tury. In: Savinov DG, editor. Problemy izucheniya okunevskoy kul’tury. St. Petersburg State University; St. Petersburg: 1995. pp. 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Komarova MN. Burials of the Okunev Ulus. Sovetskaya archaeologia. 1947;9:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Weber AW, Schulting RJ, Ramsey CB, Bazaliiskii VI, Goriunova OI, Natal’ia EB. Chronology of middle Holocene hunter–gatherers in the Cis-Baikal region of Siberia: Corrections based on examination of the freshwater reservoir effect. Quat Int. 2016;419:74–98. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Moussa NM, Bazaliiskii VI, Goriunova OI, Bamforth F, Weber AW. Y-chromosomal DNA analyzed for four prehistoric cemeteries from Cis-Baikal, Siberia. J Arch Sci Rep. 2018;17:932–42. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ovchinnikov MP. Materialy dlia izucheniia drevnostei v okrestnostiakh Irkutska. Izvestia VSORGO Vol XXXV. Irkutskaia tipolitografiia; Irkutsk: 1904. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bazaliiskii VI, Savelyev NA. The wolf of Baikal: the “Lokomotiv” early Neolithic cemetery in Siberia (Russia) Antiquity. 2003;77(295):20–30. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Okladnikov AP, Konopatskiy AK. Hunters for seal on the Baikal Lake in the Stone and Bronze Ages. Folk Dan Ethnogr Tidsskr. 1974;16:299–308. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tiutrin AA, Bazaliiskii VI. Mogil’nik v ust’e reki Idy v doline Angary [A cemetery at the mouth of the Ida River in the Angara River Valley] Arkheologiia Paleoekologiia Ehnologiia Sib Dalnego Vostoka. 1996;1:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Weber AW, McKenzie HG, Lieverse AR, Goriunova OI, editors. Kurma XI, a Middle Holocene hunter-gatherer cemetery on Lake Baikal, Siberia: Archaeological and Osteological Materials. German Archaeological Institute; Berlin: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ramsey CB, Schulting R, Goriunova OI, Bazaliiskii VI, Weber AW. Analyzing radiocarbon reservoir offsets through stable nitrogen isotopes and Bayesian modeling: a case study using paired human and faunal remains from the Cis-Baikal region, Siberia. Radiocarbon. 2014;56(2):789–799. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nomokonova T, Losey RJ, Weber AW. A freshwater old carbon offset in Lake Baikal, Siberia and problems with the radiocarbon dating of archaeological sediments: evidence from the Sagan-Zaba II site. Quat Int. 2013;290:110–125. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schulting RJ, Ramsey CB, Bazaliiskii VI, Goriunova OI, Weber AW. Freshwater reservoir offsets investigated through paired human-faunal 14 C dating and stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis at Lake Baikal, Siberia. Radiocarbon. 2014;56(3):991–1008. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Omura S. Preliminary report on the ninth excavation at Kaman-Kalehöyük (1994) In: Mikasa T, editor. Essays on Ancient Anatolia and Syria in the second and third millennium BC. Harrassowitz; Wiesbaden: 1996. pp. 87–163. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hongo H. Continuity or changes: faunal remains from stratum IId at Kaman-Kalehöyük. In: Fischer B, Genz H, Jean É, Köroğlu K, editors. Identifying changes: the transition from Bronze to Iron Ages in Anatolia and its neighbouring regions. Türk Eskiçağ Bilimleri Enstitüsü; Istanbul: 2003. pp. 257–269. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Omura S. Kaman-Kalehöyük excavations in central Anatolia. In: McMahon G, Steadman S, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2011. pp. 1095–1111. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Şenyurt SY, Akcay A, Kamış Y. Ovaören 2013 Yılı Kazıları. In: Dönmez H, editor. 36. Kazı Sonuçları Toplantısı. II. T. C. Kültür ve turizm bakanlığı; Ankara: 2014. pp. 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Şenyurt SY, Akçay A, Kamış Y. Nevşehir-Ovaören Kazısı 2012. TEBE-Haberler. 2013;36:24–26. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Şener T. thesis, Gazi University; 2014. Ovaören/Topakhöyük ve Teras Yerleşimi Erken Tunç Çaği Mezarlarının Arkeolojik ve Antropolojik Açıdan Değerlendirilmesi. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Masson VM, Pugachenkova GA. Jeitun settlement (problems of the origin of the producing economy) Nauka; Moscow: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kuftin BA. Studies of the Southern Turkmenistan Archeological Complex Expedition on studies of the Anau culture in 1952. Izvestiya Akademii Nauk Turkmenskoy SSR. Seriya oschestvennye nauki. 1954;1:22–29. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kuftin BA. Report on excavations of the XIV excavation team of the Southern Turkmenistan Archeological Complex Expedition of agricultural settlements of the Eneolithic and Bronze Age in 1952. Trudy Uzhno-Turkmenistanskoy arkheologicheskoy kompleksnoy expeditsii. 1956;7:260–290. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Merpert NY. The Eneolithic of the Southern part of the USSR and Eurasian steppes. In: Mason VM, Merpert NY, editors. Eneolithic of the USSR. Nauka; Moscow: 1982. pp. 322–331. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Masson VM. Srednyaya Asiya i Drevniy Vostok. Nauka; Moscow-Leningrad: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Avanesova NA, Jurakulova DM. The ancient nomads of Zarafshan. Culture of nomadic peoples of Central Asia (Proceedings of the International Conference, Samarkand, MICAI); 2008. pp. 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Damgaard PB, Margaryan A, Schroeder H, Orlando L, Willerslev E, Allentoft ME. Improving access to endogenous DNA in ancient bones and teeth. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11184. doi: 10.1038/srep11184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Willerslev E, Cooper A. Ancient DNA. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;272:3–16. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Orlando L, Ginolhac A, Zhang G, Froese D, Albrechtsen A, Stiller M, Schubert M, Cappellini E, Petersen B, Moltke I, Johnson PLF, et al. Recalibrating Equus evolution using the genome sequence of an early Middle Pleistocene horse. Nature. 2013;499:74–78. doi: 10.1038/nature12323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sinha R, Stanley G, Gulati GS, Ezran C, Travaglini KJ. Index switching causes “spreading-of-signal” among multiplexed samples in Illumina HiSeq 4000 DNA sequencing. bioRxiv. 2017 125724. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Dabney J, Meyer M. Length and GC-biases during sequencing library amplification: a comparison of various polymerase-buffer systems with ancient and modern DNA sequencing libraries. Biotechniques. 2012;52:87–94. doi: 10.2144/000113809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wong EHM, Khrunin A, Nichols L, Pushkarev D, Khokhrin D, Verbenko D, Evgrafov O, Knowles J, Novembre J, Limborska S, Valouev A. Reconstructing genetic history of Siberian and Northeastern European populations. Genome Res. 2017;27:1–14. doi: 10.1101/gr.202945.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Schubert M, Lindgreen S, Orlando L. AdapterRemoval v2: rapid adapter trimming, identification, and read merging. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:88. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-1900-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv. 2013 1303.3997. [Google Scholar]

- 119.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, Philippakis AA, del Angel G, Rivas MA, Hanna M, McKenna A, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.García-Alcalde F, Okonechnikov K, Carbonell J, Cruz LM, Götz S, Tarazona S, Dopazo J, Meyer TF, Conesa A. Qualimap: evaluating next-generation sequencing alignment data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2678–2679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fu Q, Mittnik A, Johnson PLF, Bos K, Lari M, Bollongino R, Sun C, Giemsch L, Schmitz R, Burger J, Ronchitelli AM, et al. A revised timescale for human evolution based on ancient mitochondrial genomes. Curr Biol. 2013;23:553–559. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Green RE, Krause J, Briggs AW, Maricic T, Stenzel U, Kircher M, Patterson N, Li H, Zhai W, Fritz MH-Y, Hansen NF, et al. A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome. Science. 2010;328:710–722. doi: 10.1126/science.1188021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Rasmussen M, Guo X, Wang Y, Lohmueller KE, Rasmussen S, Albrechtsen A, Skotte L, Lindgreen S, Metspalu M, Jombart T, Kivisild T, et al. An Aboriginal Australian genome reveals separate human dispersals into Asia. Science. 2011;334:94–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1211177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Skoglund P, Storå J, Götherström A, Jakobsson M. Accurate sex identification of ancient human remains using DNA shotgun sequencing. J Archaeol Sci. 2013;40:4477–4482. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lipatov M, Sanjeev K, Patro R, Veeramah K K. Maximum likelihood estimation of biological relatedness from low coverage sequencing data. bioRxiv. 2015 023374. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wigginton JE, Cutler DJ, Abecasis GR. A note on exact tests of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:887–893. doi: 10.1086/429864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PIW, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Fu Q, Li H, Moorjani P, Jay F, Slepchenko SM, Bondarev AA, Johnson PLF, Aximu-Petri A, Prüfer K, de Filippo C, Meyer M, et al. Genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia. Nature. 2014;514:445–449. doi: 10.1038/nature13810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Delaneau O, Marchini J, Zagury J-F. A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nat Methods. 2011;9:179–181. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Leslie S, Winney B, Hellenthal G, Davison D, Boumertit A, Day T, Hutnik K, Royrvik EC, Cunliffe B, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2, International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium. Lawson DJ, et al. The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population. Nature. 2015;519:309–314. doi: 10.1038/nature14230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Palamara PF, Francioli LC, Wilton PR, Genovese G, Gusev A, Finucane HK, Sankararaman S, Genome of the Netherlands Consortium. Sunyaev SR, de Bakker PIW, Wakeley J, et al. Leveraging Distant Relatedness to Quantify Human Mutation and Gene-Conversion Rates. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97:775–789. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lipson M, Loh P-R, Sankararaman S, Patterson N, Berger B, Reich D. Calibrating the Human Mutation Rate via Ancestral Recombination Density in Diploid Genomes. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Patterson N, Moorjani P, Luo Y, Mallick S, Rohland N, Zhan Y, Genschoreck T, Webster T, Reich D. Ancient admixture in human history. Genetics. 2012;192:1065–1093. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.145037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Li H. A statistical framework for SNP calling, mutation discovery, association mapping and population genetical parameter estimation from sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2987–2993. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Poznik GD, Henn BM, Yee M-C, Sliwerska E, Euskirchen GM, Lin AA, Snyder M, Quintana-Murci L, Kidd JM, Underhill PA, Bustamante CD, et al. chromosomes resolves discrepancy in time to common ancestor of males versus females. Science. 2013;341:562–565. doi: 10.1126/science.1237619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Poznik GD. yHaplo: identifying Y-chromosome haplogroups in arbitrarily large samples of sequenced or genotyped men. bioRxiv. 2016 088716. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Rasmussen M, Anzick SL, Waters MR, Skoglund P, DeGiorgio M, Stafford TW, Jr, Rasmussen S, Moltke I, Albrechtsen A, Doyle SM, Poznik GD, et al. The genome of a Late Pleistocene human from a Clovis burial site in western Montana. Nature. 2014;506:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature13025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]