Abstract

SRY is the master regulator of male sex determination in eutherian mammals. In mice, Sry expression is transcriptionally and epigenetically controlled in a developmental stage-specific manner. The Sry promoter undergoes demethylation in embryonic gonadal somatic cells at the sex-determining period. However, its molecular mechanism and in vivo significance remain unclear. Here, we report that the Sry promoter is actively demethylated during gonadal development, and TET2 plays a fundamental role in Sry demethylation. Tet2-deficient mice showed absence of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the Sry promoter. Furthermore, Tet2 deficiency diminished Sry expression, indicating that TET2-mediated DNA demethylation regulates Sry expression positively. We previously showed that the deficiency of the H3K9 demethylase Jmjd1a compromises Sry expression and induces male-to-female sex reversal. Tet2 deficiency enhanced the sex reversal phenotype of Jmjd1a-deficient mice. Thus, TET2-mediated active DNA demethylation and JMJD1A-mediated H3K9 demethylation contribute synergistically to sex determination.

Subject terms: DNA methylation, Developmental biology

Introduction

Expression of developmental genes is tuned through crosstalk between transcription factors and epigenetic regulation. The mammalian sex determining gene, Sry, is expressed in a certain population of somatic cells, termed as pre-Sertoli cells, in sexually undifferentiated embryonic gonads, thereby triggering the male development pathway1–3. Sry is expressed in a highly time-specific manner, i.e., its expression starts around embryonic day 10.5 (E10.5), peaks at around E11.5, and almost disappears by E12.54–8. Sry expression is positively regulated by several transcription factors9. However, research on epigenetic mechanisms that contribute to Sry regulation is in its infancy. We previously reported that the H3K9 demethylase JMJD1A (also known as TSGA/JHDM2A/KDM3A) plays a pivotal role in mouse sex determination through Sry activation10. Recently, it was reported that histone acetyltransferases are also involved in Sry activation11.

In addition to histone modification, DNA methylation plays a pivotal role in developmental gene regulation12,13. DNA methylation is found to occur predominantly on cytosine followed by guanine residues (CpG)14–16. DNA methylation is induced by the de novo DNA methyltransferases DNMT3A/DNMT3B, and is maintained by a maintenance DNA methyltransferase DNMT1 during DNA replication. CpG methylation marks can be removed by replication-dependent and independent mechanisms17. The former is regulated by inhibition of DNA methyltransferase activity during de novo DNA synthesis, whereas the latter (also known as active demethylation) is induced by the oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) by ten-eleven translocation proteins (TET1/TET2/TET3) to produce 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC)18. 5hmC is further oxidized to 5-formylcytosine (5fC) and 5-carboxycytosine (5caC) by TET enzymes, both of which can be repaired by the base excision repair (BER) pathway to produce unmodified cytosine19. Previous studies have reported that the CpG sequences of the Sry promoter are demethylated in gonadal somatic cells at the sex-determining period20,21. These observations indicated that DNA demethylation in Sry promoter preceded Sry expression onset and that DNA demethylation was more pronounced in the Sry promoter region than in other Sry loci20. Furthermore, promoter activity assay showed that in vitro methylation of the 5′-flanking region of Sry suppressed reporter activity21. Although these results suggest a possible link between DNA demethylation and Sry expression, the regulatory mechanism of DNA demethylation in Sry promoter and its functional significance for sex determination remain elusive.

Here, we show that the active DNA demethylation pathway is involved in Sry regulation. 5hmC levels on Sry promoter were increased with increasing Sry expression in the somatic cells of developing gonads. Deficiency of Tet2, but not Tet1/Tet3, induced an increase in DNA methylation and disappearance of 5hmC in Sry promoter, indicating the pivotal role of TET2 in the dynamic regulation of DNA methylation in Sry promoter. Importantly, Sry expression was diminished in Tet2-deficient gonadal somatic cells at the sex-determining period. Furthermore, Tet2 deficiency had a synergistic effect on the sex reversal phenotype, observed in a Jmjd1a-deficient background. These results identify TET2 as a responsible enzyme for DNA demethylation in Sry promoter and reveal that active DNA demethylation acts synergistically with histone modifications for epigenetic regulation of Sry and male sex determination.

Results

5-hydroxymethylcytosine is preferentially enriched in NR5A1-positive gonadal somatic cells

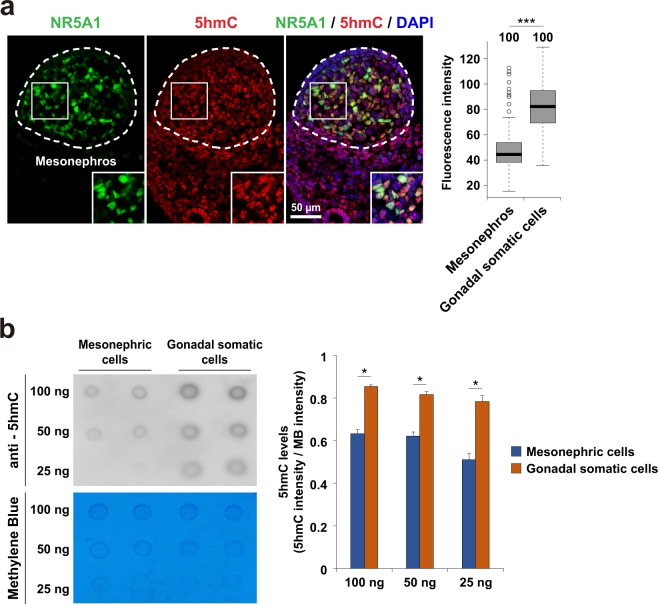

Active DNA demethylation plays important roles in the processes of development and differentiation in mammals22. 5hmC, an intermediate in the active DNA demethylation pathway, is generated by oxidation of 5mC. To elucidate whether active DNA demethylation occurs during embryonic gonadal development, we performed double immunostaining analyses on XY embryonic gonad sections at the sex-determining period (E11.5) with antibodies against 5hmC and NR5A1 (also known as AD4BP/SF-1), which is transcription factor expressed in gonadal somatic cells but not in germ cells and mesonephric cells. We observed strong 5hmC signals in NR5A1-positive gonadal somatic cells, whereas these were weak in mesonephric cells (Fig. 1a, left). Quantitative analysis indicated that the average intensity of 5hmC was about two-fold higher in NR5A1-positive gonadal somatic cells compared to that in mesonephric cells (Fig. 1a, right). These data suggest that active DNA demethylation might arise in developing gonads around the sex-determining period.

Figure 1.

5-hydroxymethylcytosine is preferentially enriched in NR5A1-positive gonadal somatic cells. (a) Co-immunostaining profiles of NR5A1 and 5hmC in the central regions of XY E11.5 gonads. Enlarged boxes indicate co-localization of NR5A1 and 5hmC in gonadal somatic cells. Fluorescence intensity values of 5hmC in every 100 gonadal somatic cells and mesonephric cells were examined and summarized in a box plot (right). Signal intensity was quantified using ImageJ software. ***P < 0.001. n = 100. (b) Comparison of 5hmC amounts between mesonephric cells and gonadal somatic cells. Mesonephric cells and gonadal somatic cells were separated from XY embryos at E11.5 that carried Nr5a1-hCD271-transgene (see Materials and Method section) and were introduced into Dot-blot analysis. The relative amounts of 5hmC were calculated by dividing the signal intensity of 5hmC by that of methylene blue (right). Signal intensity was quantified using ImageJ software. Error bars indicate the SEM values of duplicates of the dot signal intensity. *P < 0.05.

To confirm the previous result, we measured global 5hmC levels in gonadal somatic cells and mesonephric cells by dot-blot analysis. We previously established Nr5a1-hCD271-transgenic (tg) mice in which NR5A1-positive gonadal somatic cells were tagged with a cell surface antigen, hCD27110,23. Using this tg line, we isolated NR5A1-positive cells (hereafter referred as gonadal somatic cells) from gonad-mesonephros pairs of E11.5 XY embryos, and then used them for 5hmC quantification. 5hmC levels in gonadal somatic cells were higher than those in mesonephric cells (Fig. 1b, left). Quantification analysis showed that 5hmC content was about 1.5-fold higher in gonadal somatic cells than that in mesonephric cells (Fig. 1b, right). These findings support the fact that active demethylation occurs preferentially in the gonadal somatic cell population at the sex-determining period.

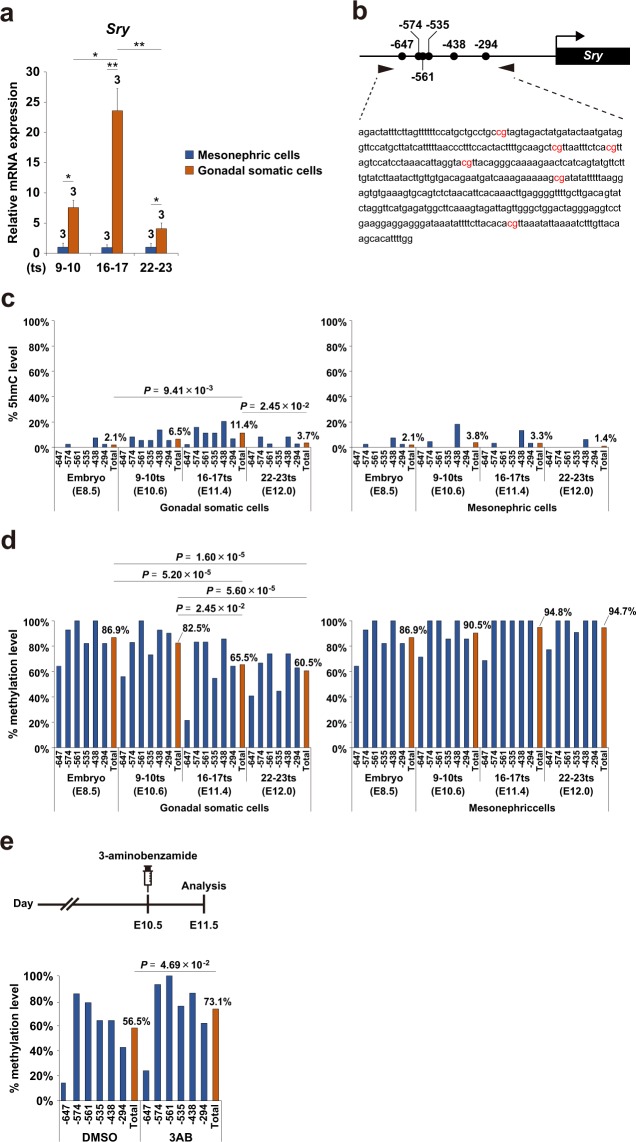

Sry promoter undergoes active DNA demethylation during gonadal development

To examine the kinetic relationship between Sry expression and DNA methylation/demethylation of Sry, we collected gonadal somatic cells from XY embryos at the tail somite (ts) stages 9 to 23 (E10.6-E12.0). In accordance with the known expression profile of Sry, its transcripts were highly enriched in the gonadal somatic cell fraction with a peak at the ts stage 16–17 (E11.4) (Fig. 2a). As shown in Fig. 2b, the Sry promoter contains 6 CpG sites. Genomic DNA isolated from gonadal somatic cells was used for Tet-assisted bisulfite (TAB) sequencing analysis, by which 5hmC can be quantitatively detected at single-base resolution24 (Fig. 2c). We found that 5hmC was detected in the Sry promoter in gonadal somatic cells, whereas it was barely detectable in E8.5 embryos and mesonephric cells (Fig. 2c). Notably, 5hmC levels in the Sry promoter in gonadal somatic cells fluctuated with kinetics similar to those of Sry expression during gonadal development (compare Fig. 2a with Fig. 2c). To confirm the correlation between 5hmC enrichment and DNA demethylation dynamics, we next examined DNA methylation (5mC + 5hmC) levels in the Sry promoter in gonadal somatic cells by bisulfite sequencing (Fig. 2d). With the development of gonads, DNA methylation levels of the Sry promoter were reduced progressively in gonadal somatic cells, whereas those of in E8.5 embryos and mesonephric cells were constantly close to 100% (Fig. 2d). These results collectively suggest that active DNA demethylation through 5mC oxidation might account for the reduction of DNA methylation in Sry promoter in the developing gonads, at least in part.

Figure 2.

Sry promoter undergoes active DNA demethylation during gonadal development. (a) qRT-PCR analysis of Sry in XY mesonephric cells and gonadal somatic cells at the indicated ts stages. mRNA expression levels in mesonephric cells at the 9–10 ts stage (E10.6) were defined as 1. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. n = 3. (b) Schematic representation of Sry promoter. Sry promoter contains 6 CpG sites. The positions of CpG sites are indicated relative to the start codon. (c and d) DNA methylation kinetics on Sry promoter in XY E8.5 embryos and XY mesonephric/gonadal somatic cells at the indicated developmental stages by Tet-assisted bisulfite sequencing analysis (c) and bisulfite sequencing analysis (d). Blue bars show the average percentage of methylation at individual CpG sites respectively and the red bar indicates that on total CpG sites. P values for bisulfite sequencing were obtained using the non-parametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. (e) Administration of BER inhibitor inhibits DNA demethylation in the Sry promoter in developing gonads. The experimental scheme is shown in the upper panel. A BER inhibitor 3-aminobenzamide (3-AB) was intraperitoneally injected into pregnant females carrying E10.5 embryos. At 24 hours after injection, gonadal somatic cells were purified from XY embryos and used for bisulfite sequencing analysis. The lower panel shows DNA methylation levels of Sry promoter in 3-AB-treated and DMSO-treated (as vehicle control) XY gonadal somatic cells. The blue bar shows the average percentage of methylation at individual CpG sites and the red bar shows that of total CpG sites. P values for bisulfite sequencing were obtained using the non-parametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test.

To confirm the involvement of the active DNA demethylation pathway in Sry regulation, we utilized 3-aminobenzamide (3-AB), a pharmacological inhibitor of the BER components PARP1. Several studies showed that 3-AB preserves 5mC levels by blocking the BER-dependent DNA demethylation pathway in primordial germ cells and embryonic stem cells25–27. 3-AB was intraperitoneally injected into pregnant females carrying E10.5 XY Nr5a1-hCD271-tg embryos (Fig. 2e). Gonadal somatic cells were isolated from the corresponding embryos 24 hours after injection and used for bisulfite sequence analysis (Fig. 2e). The averages of DNA methylation at the Sry promoter were 56.5% and 73.1% in the control and 3-AB treated gonadal somatic cells, respectively (Fig. 2e). The higher level of DNA methylation in 3-AB-treated cells supports the involvement of the active DNA demethylation pathway in the Sry regulation of gonadal somatic cells.

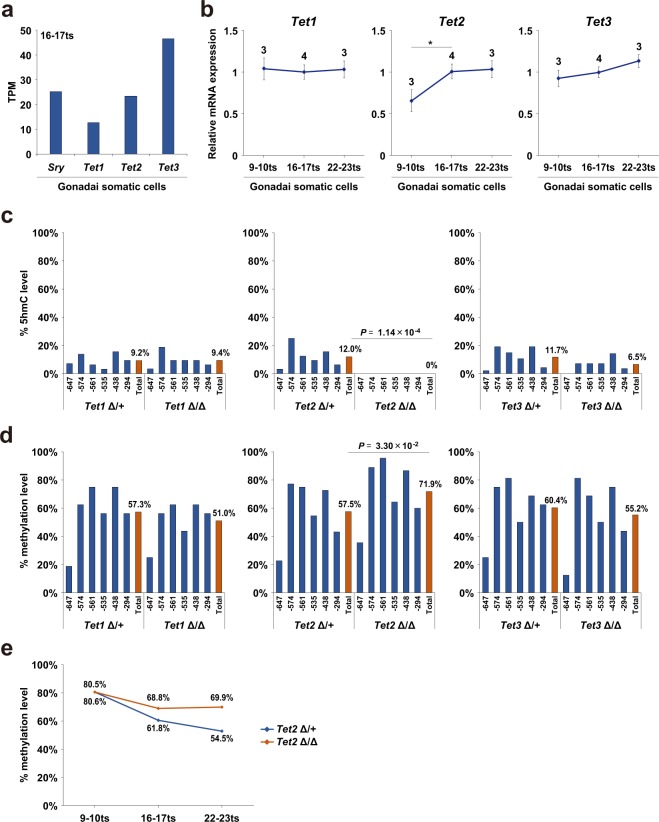

TET2 plays a pivotal role in active DNA demethylation of the Sry promoter

Active DNA demethylation is triggered by hydroxylation of 5mC to 5hmC, which is catalyzed by TET proteins18. Because all Tet subfamily proteins, TET1, TET2, and TET3, have an enzymatic activity toward 5hmC production, we aimed to identify the enzyme responsible for Sry demethylation. mRNAs for Tet1, Tet2, and Tet3 were detected in the gonadal somatic cells at the 16–17ts stage when Sry expression reached a peak (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table S1). As shown in Fig. 3b, we found that mRNAs of Tet2 were gradually increased, whereas those of Tet1 and Tet3 were unchanged in the somatic cells of developing gonads. To address the loss of function phenotype of TET enzymes, we generated mice carrying each mutant allele for Tet1, Tet2, and Tet3 (hereafter described as Tet1Δ, Tet2Δ, and Tet3Δ) using the CRISPR/cas9 system (Supplementary Fig. S1). Each of the Tet-mutant lines was crossed with the Nr5a1-hCD271-tg line for further analysis. Gonadal somatic cells were immuno-magnetically collected from corresponding mutant embryos at the 16–17ts stage and used for TAB and bisulfite sequencing analysis (Fig. 3c,d, respectively). Strikingly, TAB sequence analysis demonstrated that 5hmC at the Sry promoter was completely abolished in Tet2Δ/Δ gonadal somatic cells, whereas it was unchanged in Tet1Δ/Δ or Tet3Δ/Δ cells (Fig. 3c). As shown in Fig. 3d, bisulfite sequencing analysis indicated that homozygous mutation of Tet2 induced a significant increase in DNA methylation in the Sry promoter of gonadal somatic cells, whereas mutation of Tet1 and Tet3 did not (Fig. 3d). We next examined the kinetics of DNA methylation in Sry promoter during gonadal development from ts stages 9 to 23. As summarized in Fig. 3e, DNA methylation levels were progressively decreased in control cells but were almost unchanged in Tet2Δ/Δ gonadal somatic cells. From these results, we conclude that TET2 is the bona fide enzyme responsible for active demethylation at Sry promoter during gonadal development.

Figure 3.

TET2 plays a pivotal role in active DNA demethylation of Sry promoter. (a) RNA-seq based gene expression values (TPM) of Sry, Tet1, Tet2, and Tet3 in gonadal somatic cells at the sex-determining period. n = 2. (b) Expression kinetics of Tet1, Tet2, and Tet3 in gonadal somatic cells. mRNAs were collected from XY gonadal somatic cells at the indicated ts stages and introduced into qRT-PCR analysis. mRNA expression levels in gonadal somatic cells at 16–17 ts stage were defined as 1. Data are presented as mean ± SD. * P < 0.05. n ≥ 3. (c and d) DNA methylation levels in the Sry promoter in E11.5 XY gonadal somatic cells of the indicated genotypes were measured by TAB sequencing (c) and bisulfite sequencing. (d) Blue bar shows the average percentage of methylation at individual CpG sites and red bar shows the average percentage of methylation on total CpG sites. P values for bisulfite sequencing were obtained using the non-parametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test. (e) Comparison of DNA methylation kinetics in the Sry promoter in develoing gonads. Gonadal somatic cells were purified from XY Tet2Δ/+ and Tet2Δ/Δ embryos at the indicated ts stages and were then used for bisulfite sequencing analysis.

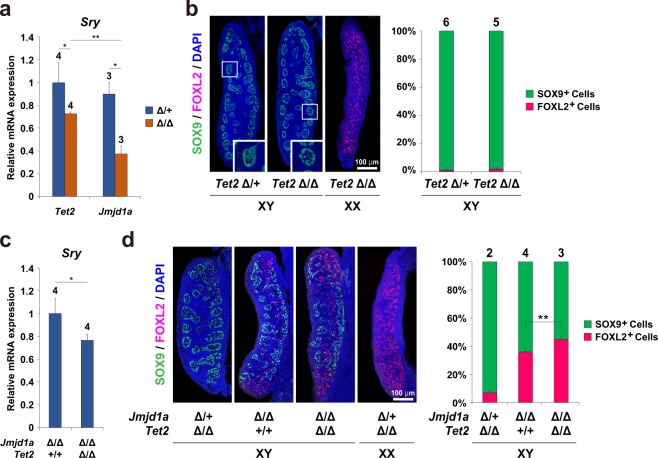

Tet2 mutation diminishes Sry expression in gonadal somatic cells and enhances sex-reversal in XY Jmjd1aΔ/Δ mice

We next aimed to address the role of TET2-mediated DNA demethylation in mouse sexual development. We first examined whether Sry expression was affected in Tet2Δ/Δ gonadal somatic cells at the sex-determining period. As shown in Fig. 4a, quantitative mRNA expression analysis indicated that Sry expression was significantly reduced in Tet2Δ/Δ gonadal somatic cells, indicating involvement of TET2-mediated DNA demethylation in regulating Sry expression. Our previous study demonstrated that JMJD1A-mediated H3K9 demethylation contributes to the regulation of Sry expression in developing gonads26. Comparative and quantitative analysis of Sry mRNA demonstrated that the decreased level of Sry expression by Tet2Δ/Δ mutation was moderate compared to that by Jmjd1a mutation (Fig. 4a). We next examined whether Tet2 deficiency influences sexual development in embryonic gonads. For this, we performed co-immunostaining analysis on E13.5 gonad sections using antibodies against the testicular Sertoli cell marker SOX9 and the ovarian somatic cell marker FOXL2. As shown in Fig. 4b, Tet2Δ/Δ gonads possessed typical features of embryonic testis, in which SOX9-positive cells were abundant and testicular tubule formation proceeded, indicating that Tet2 mutation alone does not induce sex reversal in embryonic gonads. It is possible that Tet2 deficiency might affect DNA methylation levels of Sox9 and Foxl2, and thereby influence this expression. To address this issue, we examined DNA methylation levels at the Sox9 and Foxl2 promoters in E11.5 gonadal somatic cells. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, Tet2 deficiency did not alter the DNA methylation levels of Sox9 and Foxl2 promoters in gonadal somatic cells.

Figure 4.

Tet2 mutation diminishes Sry expression in gonadal somatic cells and enhances sex-reversal in XY Jmjd1aΔ/Δ mice. (a) Comparison of Sry mRNA levels between genotypes at the sex-determining period. Gonadal somatic cells were purified from E11.5 embryos of the indicated genotypes and were then used for qRT-PCR analysis. mRNA expression levels in Tet2Δ/+ gonadal somatic cells were defined as 1. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. n ≥ 3. (b) Evaluation of sex development of Tet2-deficient E13.5 gonads by immunofluorescence analysis using antibodies against SOX9 and FOXL2. SOX9 and FOXL2 are markers for testicular Sertoli cells and ovarian somatic cells, respectively. The enlarged box demonstrates testicular tubule-like structures (left). The ratio of SOX9-positive cells to FOXL2-positive cells is summarized in the right. Numbers of embryos examined are shown above the bars. Data are presented as mean ± SD. (c) qRT-PCR analysis of Sry in XY Jmjd1a-deficient gonads and Jmjd1a/Tet2-deficient gonads at E11.5. Each of the samples included one pair of gonads/mesonephros. mRNA expression levels in Jmjd1a-deficient gonads were defined as 1. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05. n = 4. (d) Sex development of E13.5 embryonic gonads of the indicated genotypes was evaluated as in Fig. 4b. The ratio of SOX9-positive cells to FOXL2-positive cells is summarized in the right. Numbers of embryos examined are shown above the bars. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05.

Our previous study demonstrated that Jmjd1a deficiency does not induce a significant increase in the DNA methylation of Sry promoter in gonadal somatic cells, suggesting that active DNA demethylation in Sry promoter occurs independently of JMJD1A-mediated H3K9 demethylation28. To address the synergistic effect between TET2-mediated DNA demethylation and JMJD1A-mediated H3K9 demethylation on gonadal sex development, we generated Tet2/Jmjd1a-double deficient mice and examined their gonadal sex development. Sry expression levels of Tet2/Jmjd1a-double deficient gonads were significantly lower than those of Jmjd1a-deficient gonads at the sex-determining period (Fig. 4c). Jmjd1a-deficient gonads at E13.5 were ovotestes composed of testicular cells and ovarian cells (Fig. 4d). Importantly, the ratio of FOXL2-positive cells to SOX9-positive cells was increased in Tet2/Jmjd1a-double deficient gonads as compared to Jmjd1a-deficient gonads (Fig. 4d). These results indicate that TET2-mediated DNA demethylation controls testicular development positively and synergistically with JMJD1A-mediated H3K9 demethylation.

Discussion

The CpG sites of Sry promoter are demethylated in gonadal somatic cells at the sex-determining period20,21. However, its molecular mechanism and in vivo significance remain elusive. Here, we discovered that 5hmC was highly enriched in XY gonadal somatic cells at the sex-determining period and that the 5hmC level was increased in Sry promoter concomitantly with Sry expression in these cells. We also identified TET2 as the enzyme responsible for active DNA demethylation in Sry promoter. Finally, we revealed that TET2-mediated active DNA demethylation is involved in regulating Sry expression and sex development. Here we discuss the role of DNA demethylation in the epigenetic regulation of Sry.

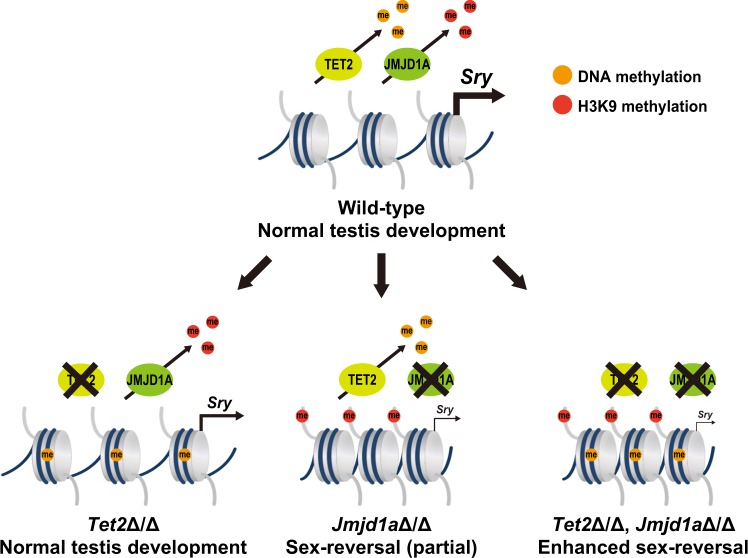

Our previous results have shown that Sry mRNA is not completely abolished in XY Jmjd1a-deficient embryos. We therefore speculated that along with H3K9 demethylation, other epigenetic regulatory mechanism might also control Sry expression10. Our present study revealed that Sry activation is ensured by active DNA demethylation as well as by H3K9 demethylation (Fig. 5). In this model, JMJD1A-mediated H3K9 demethylation substantially contributes to Sry activation whereas TET2-mediated DNA demethylation acts supportively. Tet2 deficiency leads to reduced Sry expression levels, whereas subsequent gonadal sex development proceeds normally. These facts strongly suggest that Sry expression levels in Tet2-deficient gonadal somatic cells are still higher than the threshold required for triggering the testis formation pathway3. In contrast, we found that Tet2 deficiency synergistically enhances the sex reversal phenotype of Jmjd1a-deficient mice, indicating that TET2-mediated DNA demethylation practically contributes to mouse sex development.

Figure 5.

A schematic diagram for the regulation of Sry expression by TET2 and JMJD1A. Epigenetic regulation of Sry expression through H3K9 demethylation and DNA demethylation in male gonad development. TET2 catalyzes DNA demethylation in the Sry promoter. It is conceivable that Sry expression levels in Tet2-deficient gonads might be higher than the threshold required for testis development. JMJD1A-mediated H3K9 demethylation plays a dominant role in Sry activation. Jmjd1a deficiency lead to substantial reduction of Sry expression, thereby inducing sex-reversal. We found that Tet2 deficiency synergistically enhanced the sex reversal phenotype of Jmjd1aΔ/Δ embryos.

Although Tet1 and Tet3 were expressed in gonadal somatic cells at the sex-determining period, DNA methylation at the Sry promoter was not affected by Tet1 or Tet3 deficiency (Fig. 3a,b). These results suggest that there might be an unrevealed mechanism by which Sry is demethylated specifically by TET2. Interestingly, the protein structure of TET2 differs from those of TET1 and TET3, as TET1/TET3, but not TET2, contain the CxxC domain that is essential for CpG site recognition. Therefore, it is plausible that recruitment of TET2 to its target loci depends on its interacting factor29. A zinc finger-type transcription factor WT1 plays an essential role in male sex-determination30. In vitro analysis has shown that WT1 (-KTS), one of the WT1 protein isoforms, can bind and activate Sry promoter31–36. Another study reported that WT1 directly binds to TET2, but not TET1, and recruits TET2 to the target genes37. In addition, WT1 displays high affinity for sequences containing 5mC rather than 5hmC or 5fC38. Considering these previous reports, it is possible that a specific DNA binding molecule mediates the recruitment of TET2 to the Sry promoter in gonadal somatic cells, and WT1 may be a promising candidate. We found that Wt1 mRNA was constantly expressed in the developing XY gonads (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Although we showed that TET2 catalyzes active DNA demethylation at Sry promoter in gonadal somatic cells at the sex-determining period (Fig. 3c), we could not rule out the possibility that the TET protein-independent pathway also contributes to DNA demethylation at Sry promoter. For example, activation-induced deaminase (AID)/APOBEC-family cytosine deaminases are known to be involved in another pathway of active DNA demethylation. AID/APOBEC-family enzymes do not produce 5hmC but produce 5-methyluracil by deaminating the cytidine of 5mC39, which eventually converts to unmodified cytosine through the BER pathway40,41. Several studies have shown that APOBEC3 can discriminate against 5mC39,42. In fact, our mRNA expression analysis has demonstrated higher expression of Apobec3 in gonadal somatic cells than that in mesonephric cells during gonadal development (Supplementary Fig. S3). Therefore, it is worth investigating whether the APOBEC3-mediated DNA demethylation pathway also plays a role in active DNA demethylation at the Sry promoter.

Sry demethylation is the earliest event in male embryonic gonad development20. Our data showed that the Sry promoter is demethylated during Sry induction through TET2-mediated active demethylation. Interestingly, we found that methylation of Sry promoter was maintained at low levels even at E12.0 (Fig. 2d), whereas Sry expression became diminished until this stage. These results were consistent with a previous report20. mRNA expression analysis demonstrated constant expression of Dnmt3b and increased expression of Dnmt1 and Dnmt3a in the developing XY gonads from E10.6 to E12.0 (Supplementary Fig. S4). Taking these results together, we postulate that DNA methylation/demethylation are required for Sry induction but not for its repression. Instead, Sry repression might be achieved independently of epigenetic regulation. Transient expression of SRY initiates Sox9 expression43. Once SOX9 reaches a critical threshold, Sry is repressed by a SOX9-dependent negative-feedback loop43,44. It is conceivable that Sry repression might be achieved by such feedback loop of transcription factors.

Other than JMJD1A and TET2, we previously demonstrated that an H3K9 methyltransferase complex, GLP/G9a is involved in Sry regulation with an antagonistic function against JMJD1A28. Moreover, recent studies have revealed that histone acetyltransferases p300/CBP play a crucial role in Sry activation11 and that polycomb-group protein CBX2 is involved in testis development by repressing Wnt signal45. These findings indicate that multiple epigenetic modifiers contribute to the complicated process of gonadal sex differentiation in mammals. However, it is still unclear and further study is required to determine how these enzymes are recruited to specific target loci including Sry, during gonadal sex development.

Methods

Animals

All animal experiments and methods were approved and performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Animal Care Committee of Tokushima University (T29-62) and Osaka University (FBS-18-014). Mice (C57BL/6J and ICR) were supplied by SLC (Shimizu Laboratory Supplier, Kyoto) in Japan. Mouse lines of Jmjd1a-deficient mice and Nr5a1-hCD271-transgenic mice10 were sequentially backcrossed with C57BL/6J, and the F5 or later generation was used. Embryos were staged by counting tail somites as described, where approximately E10.6, E11.4, and E12.0 correspond to 9–10 ts, 16–17 ts, and 22–23 ts, respectively.

Generation of Tet mutant mice using a CRISPR/Cas9 system

Mutant mice for each Tet (Tet1/2/3) were produced by electroporating Cas9 mRNA and gRNA into mouse zygotes according to the protocol published recently46. Briefly, 400 ng/µl Cas9 mRNA and 100 ng/µl each gRNAs targeting Tets (shown in Supplementary Fig. S2) were introduced into zygotes (C57BL/6 J × C57BL/6 J) by electroporation using Genome Editor GEB15 (BEX, Tokyo, Japan). The electroporation conditions were 30 V (3 msec ON + 97 msec OFF) × 4 times. The surviving 2-cell-stage embryos were transferred to the oviducts of pseudopregnant females (ICR). Mutant mice were backcrossed for more than three generations into the C57BL6/J background.

Magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS)

MACS was performed as described previously18. Briefly, a single cell suspension was prepared by trypsinizing the gonads and mesonephros isolated from embryos carrying the Nr5a1/CD271-transgene. Immunomagnetic isolation of CD271-expressing cells was performed according to the standard protocol (Miltenyi Biotech).

RNA expression analysis

Total RNA from hCD271-positive/-negative cells and a pair of gonads/mesonephros was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen). ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Kit (TOYOBO) was used for cDNA synthesis, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, cDNA was used as the template for RT-qPCR using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) and SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa) with gene-specific primers. The primer sets used in this analysis were as follows:

Sry forward 5′-TACCTACTTACTAACAGCTGACATCAC-3′

Sry reverse 5′-TGTCATGAGACTGCCAACCACAGGG-3′

Tet1 forward 5′-CCATTCTCACAAGGACATTCACA-3′

Tet1 reverse 5′-GCAGGACGTGGAGTTGTTCA-3′

Tet2 forward 5′-GCCATTCTCAGGAGTCACTGC-3′

Tet2 reverse 5′-CTTCTCGATTGTCTTCTCTATTGAGG-3′

Tet3 forward 5′-TCAGGGATGCTTTCTGTAGGG-3′

Tet3 reverse 5′-ATTTGGGATGTCCAGATGAGC-3′

Apobec3 forward 5′-AGCATGCAGAAATCCTCTTCC-3′

Apobec3 reverse 5′-AGATCTGGACGATCCCTTTTG-3′

Dnmt1 forward 5′-ATCAGGTGTCAGAGCCCAAAG-3′

Dnmt1 reverse 5′-TGGTGGAATCCTTCCGATAAC-3′

Dnmt3a forward 5′- CAGACGGGCAGCTATTTACAG-3′

Dnmt3a reverse 5′- TGGTTCTCTTCCACAGCATTC-3′

Dnmt3b forward 5′-TCGCAAGGTGTGGGCTTTTGT-3′

Dnmt3b reverse 5′-CTGGGCATCTGTCATCTTTGCA-3′

Wt1 forward 5′-ATGGCCACACGCCCTCGCATCACGC-3′

Wt1 reverse 5′-AGCGAGCCCTGCTGGCCCATGGGGT-3′

Gapdh forward 5′-ATGAATACGGCTACAGCAACAGG-3′

Gapdh reverse 5′-CTCTTGCTCAGTGTCCTTGCTG-3′

Bisulfite sequencing analysis

Total genomic DNA was isolated from hCD271-positive/-negative gonad-mesonephros pairs of 3 embryos or from 3 whole embryos (E8.5). Genomic DNA was extracted using the Wizard SV Genomic DNA Purification System (Promega). Genomic DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite using the MethylEasy Xceed Rapid DNA Bisulfite Modification Kit (Human Genetic Signatures) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The bisulfite-treated DNA was PCR-amplified using respective primer sets. PCR products were subcloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) and sequenced. Methylation levels of Sry promoter analyzed by every >30 sequencing. The primer sets used in this analysis were as follows:

Sry 1st forward 5′-TTTATATTGGGTTATAGAGTTAGAATAGAT-3′

Sry 2nd forward 5′-AGATTATTTTTTAGTTTTTTTTATGT-3′

Sry 1st and 2nd reverse 5′-CCAAAATATACTTATAACAAAAATTTTAAT-3′

Sox9 1st forward 5′-GTAGTAGAAGTTTTAGTTATTAT-3′

Sox9 2nd forward 5′-GATTATTTTTAAGTATTTTTTTT-3′

Sox9 1st and 2nd reverse 5′-ATATAAATTTACTCTCTACTCTC-3′

Foxl2 1st forward 5′-GGTTTTGTTTTTTTTTATTTGAA-3′

Foxl2 2nd forward 5′-GAGGTTTGGATTATTTTTTTTT-3′

Foxl2 1st and 2nd reverse 5′-ATTTTCTTAACTAAACTCTCCC-3′

Tet-assisted bisulfite sequencing analysis

The 5hmC TAB-seq kit (WiseGene) was used for converting 5mC to 5caC, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 5hmC in genomic DNA was first protected with glycosylation by β-glycosyltransferase for 6 h at 37 °C. Genomic DNA was then treated with Tet protein overnight at 37 °C. Tet oxidized DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite using the same method as in bisulfite sequencing analysis. For verification, 5mC control DNA and 5hmC control DNA were mixed at 0.5% and 0.3% volume of total gDNA, respectively.

Immunohistochemical staining

This method was performed as described previously26. Briefly, tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in Tissue-Tek OTC compound (Sakura Finetek Japan) and cut into 10-μm sections. The sections were incubated with primary antibodies (rat anti-Nr5a1 (Trans Genic Lnc, KO610), rabbit anti-5hmC (Active Motif, #39791), anti-Sox9 (Millipore, AB5535), goat anti-Foxl2 (Abcam, ab-5096)), overnight at 4 °C. For fluorescence staining, the sections were incubated with Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies) at room temperature for 1 h and counterstained with DAPI. The sections were mounted in Vectashield (Vector) and observed with a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM700, Carl Zeiss). Co-immunostaining for Nr5a1 and 5hmC was performed in the order: antibody reaction for Nr5a1 (1st: 4 °C, O/N and 2nd: RT, 1 h) → 2 N HCl treatment (RT, 20 min) → antibody reaction for 5hmC (1st: RT, 1 h and 2nd: RT, 1 h).

In vivo inhibitor analysis

3-AB (Sigma) was prepared as a 2.5 g/ml stock solution with DMSO; 4 ml of the 3-AB stock solution was diluted with 500 ml of PBS47. Pregnant females at E10.5 were intraperitoneally administered 500 ml of the inhibitor solution.

Dot-blot analysis

Total genomic DNA was isolated from hCD271-positive/-negative cells of the gonad-mesonephros pairs of 3 embryos. Sonicated genomic DNA was prepared as 25, 50, 100 ng/µl. 1 µl of sample was spotted onto the nitrocellulose membrane. After baking at 80 °C for 1 h and blocking with 5% non-fat milk PBS-T for 1 h at room temperature, the membrane was incubated overnight with anti-5hmC antibody (Active Motif, #39791, 1:10,000) at 4 °C. Following the primary antibody reaction, the membrane was incubated with secondary horseradish peroxidase-coupled antibody. Detection was performed using the Western Lighting Plus-ECL (PerkinElmer). To ensure equal loading, the membrane was stained with methylene blue post-immunoblotting.

RNA-seq analysis

Total RNA from hCD271-positive cells of 3 embryos was extracted using the Direct-zol RNA MicroPrep kit (ZYMO RESEACH). Quality control check for length distribution and concentration of RNA fragments in the prepared libraries was performed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). The cDNA library was constructed using standard methods (Illumina TruSeq mRNA stranded kit) with index adapters (Illumina TruSeq indexes). DNA was sequenced as single-end, 50 base-length reads on the Illumina HiSeq. 1500 instrument (Illumina Inc.) with 10 million reads. Raw sequence reads were mapped to mm10 by STAR (v2.6.0a) with mostly default parameters except the following:–outFilterMultimapNmax 1. TPM (Transcripts Per Kilobase Million) for Sry, Tet1, Tet2, and Tet3 was estimated using the rsem-calculate-expression command of RSEM (v1.3.1). The TPM values for all genes are listed in Supplementary Table 1. RNA sequencing data have been uploaded to NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the accession number PRJNA557299.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Hitoshi Miyachi and Satsuki Kitano for providing technical assistance with embryo manipulation. We are especially grateful to the members of the Tachibana laboratory for technical support and stimulating discussions. This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant number 16K18429 (NO), 17H06423 (MT), 17H06424 (MT), 18H02419 (MT), and the Senri Life Science Foundation (NO).

Author Contributions

S.K. performed immunohistochemical staining. R.M. and S.K. contributed RNA-seq analysis. N.O. performed most analyses. N.O. and M.T. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-50058-7.

References

- 1.Nikolova G, Vilain E. Mechanisms of disease: transcription factors in sex determination-relevance to human disorders of sex development. Nat Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;2:231–238. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sekido R, Lovell-Badge R. Sex determination and SRY: down to a wink and a nudge? Trends Genet. 2009;25:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kashimada K, Koopman P. Sry: the master switch in mammalian sex determination. Development. 2010;137:3921–3930. doi: 10.1242/dev.048983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koopman P, Münsterberg A, Capel B, Vivian N, Lovell-Badge R. Expression of a candidate sex-determining gene during mouse testis differentiation. Nature. 1990;348:450–452. doi: 10.1038/348450a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hacker A, Capel B, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R. Expression of Sry, the mouse sex determining gene. Development. 1995;121:1603–1614. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.6.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeske YW, Bowles J, Greenfield A, Koopman P. Expression of a linear Sry transcript in the mouse genital ridge. Nat. Genet. 1995;10:480–482. doi: 10.1038/ng0895-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bullejos M, Koopman P. Spatially dynamic expression of Sry in mouse genital ridges. Dev. Dyn. 2001;221:201–205. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilhelm D, et al. Sertoli cell differentiation is induced both cell-autonomously and through prostaglandin signaling during mammalian sex determination. Dev. Biol. 2005;287:111–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larney C, Bailey TL, Koopman P. Switching on sex: transcriptional regulation of the testis-determining gene Sry. Development. 2014;141:2195–2205. doi: 10.1242/dev.107052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuroki S, et al. Epigenetic regulation of mouse sex determination by the histone demethylase Jmjd1a. Science. 2013;341:1106–1109. doi: 10.1126/science.1239864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carré GA, et al. Loss of p300 and CBP disrupts histone acetylation at the mouse Sry promoter and causes XY gonadal sex reversal. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018;27:190–198. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Smet C, Lurquin C, Lethé B, Martelange V, Boon T. DNA methylation is the primary silencing mechanism for a set of germ line- and tumor-specific genes with a CpG-rich promoter. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999;19:7327–7335. doi: 10.1128/MCB.19.11.7327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber M, et al. Distribution, silencing potential and evolutionary impact of promoter DNA methylation in the human genome. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:457–466. doi: 10.1038/ng1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruenbaum Y, Stein R, Cedar H, Razin A. Methylation of CpG sequences in eukaryotic DNA. FEBS Lett. 1981;124:67–71. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(81)80055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Razin A, et al. Variations in DNA methylation during mouse cell differentiation in vivo and in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:2275–2279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.8.2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyes J, Bird A. Repression of genes by DNA methylation depends on CpG density and promoter strength: evidence for involvement of a methyl-CpG binding protein. EMBO J. 1992;11:327–333. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05055.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu SC, Zhang Y. Active DNA demethylation: many roads lead to Rome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010;11:607–620. doi: 10.1038/nrm2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito S, et al. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333:1300–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1210597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He YF, et al. Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science. 2011;333:1303–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1210944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gierl MS, Gruhn WH, von Seggern A, Maltry N, Niehrs C. GADD45G functions in male sex determination by promoting p38 signaling and Sry expression. Dev. Cell. 2012;23:1032–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishino K, Hattori N, Tanaka S, Shiota K. DNA methylation mediated control of Sry gene expression in mouse gonadal development. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:22306–22313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309513200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasmussen KD, Helin K. Role of TET enzymes in DNA methylation, development, and cancer. Genes Dev. 2016;30:733–750. doi: 10.1101/gad.276568.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuroki S, et al. Development of a general-purpose method for cell purification using Cre/loxP-mediated recombination. Genesis. 2015;53:387–393. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu M, et al. Base-resolution analysis of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in the mammalian genome. Cell. 2012;149:1368–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hajkova P, et al. Genome-wide reprogramming in the mouse germ line entails the base excision repair pathway. Science. 2010;329:78–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1187945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ciccarone F, et al. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation acts in the DNA demethylation of mouse primordial germ cells also with DNA damage-independent roles. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46927. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okashita N, et al. PRDM14 promotes active DNA demethylation through the ten-eleven translocation (TET)-mediated base excision repair pathway in embryonic stem cells. Development. 2014;141:269–280. doi: 10.1242/dev.099622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuroki S, et al. Rescuing the aberrant sex development of H3K9 demethylase Jmjd1a-deficient mice by modulating H3K9 methylation balance. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1007034. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ko M, et al. Modulation of TET2 expression and 5-methylcytosine oxidation by the CXXC domain protein IDAX. Nature. 2013;497:122–126. doi: 10.1038/nature12052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammes A, et al. Two splice variants of the Wilms’ tumor 1 gene have distinct functions during sex determination and nephron formation. Cell. 2001;106:319–329. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00453-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ladomery M. Multifunctional proteins suggest connections between transcriptional and post-transcriptional processes. BioEssays. 1997;19:903–909. doi: 10.1002/bies.950191010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ladomery M, Dellaire G. Multifunctional zinc finger proteins in development and disease. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2002;66:331–342. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.2002.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hossain A, Saunders GF. The human sex-determining gene SRY is a direct target of WT1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:16817–16823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hossain A, Saunders GF. Role of Wilms’ tumor 1 (WT1) in the transcriptional regulation of the Mullerian-inhibiting substance promoter. Biol. Reprod. 2003;69:1808–1814. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.015826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuzawa-Watanabe Y, Inoue J, Semba K. Transcriptional activity of testis-determining factor SRY is modulated by the Wilms’ tumor 1 gene product, WT1. Oncogene. 2003;22:7900–7904. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyamoto, Y., Taniguchi, H., Hamel, F., Silversides, D. W. & Viger, R. S. A GATA4/WT1 cooperation regulates transcription of genes required for mammalian sex determination and differentiation. BMC Mol. Biol. 44 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Wang Y, et al. WT1 recruits TET2 to regulate its target gene expression and suppress leukemia cell proliferation. Mol. Cell. 2015;57:662–673. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hashimoto H, et al. Wilms tumor protein recognizes 5-carboxylcytosine within a specific DNA sequence. Genes Dev. 2014;28:2304–2313. doi: 10.1101/gad.250746.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nabel CS, et al. AID/APOBEC deaminases disfavor modified cytosines implicated in DNA demethylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8:751–758. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu JK. Active DNA demethylation mediated by DNA glycosylases. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009;43:143–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teperek-Tkacz M, Pasque V, Gentsch G, Ferguson-Smith AC. Epigenetic reprogramming: is deamination key to active DNA demethylation? Reproduction. 2011;142:621–632. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wijesinghe P, Bhagwat AS. Efficient deamination of 5-methylcytosines in DNA by human APOBEC3A, but not by AID or APOBEC3G. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:9206–9217. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sekido R, Bar I, Narváez V, Penny G, Lovell-Badge R. SOX9 is up-regulated by the transient expression of SRY specifically in Sertoli cell precursors. Dev Biol. 2004;274:271–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chaboissier MC, et al. Functional analysis of Sox8 and Sox9 during sex determination in the mouse. Development. 2004;131:1891–1901. doi: 10.1242/dev.01087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia-Moreno SA, et al. CBX2 is required to stabilize the testis pathway by repressing Wnt signaling. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:e1007895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashimoto M, Takemoto T. Electroporation enables the efficient mRNA delivery into the mouse zygotes and facilitates CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:11315. doi: 10.1038/srep11315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawasaki Y, et al. Active DNA demethylation is required for complete imprint erasure in primordial germ cells. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:3658. doi: 10.1038/srep03658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.