Abstract

Background:

From 2003 to 2012, the Philadelphia High School STD Screening Program screened 126,053 students, identifying 8089 Chlamydia trachomatis (CT)/Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) infections. We examined sociodemographic and behavioral factors associated with CT/GC diagnoses among a sample of this high-risk population.

Methods:

Standardized interviews were given to infected students receiving in-school CT/GC treatment (2009–2012) and to uninfected students calling for results (2011–2012). Sex-stratified multivariable logistic models were created to examine factors independently associated with a CT/GC diagnosis. A simple risk index was developed using variables significant on multivariable analysis.

Results:

A total of 1489 positive and 318 negative students were interviewed. Independent factors associated with a GC/CT diagnosis among females were black race (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 2.27; confidence interval, 1.12–4.58), history of arrest (AOR, 2.26; 1.22–4.21), higher partner number (AOR, 1.75; 1.05–2.91), meeting partners in own neighborhood (AOR, 1.92; 1.29–2.86), and meeting partners in venues other than own school, neighborhood, or through friends (“all other”; AOR, 9.44; 3.70–24.09). For males, factors included early sexual debut (AOR, 1.99; 1.21–3.26) and meeting partners at “all other” venues (AOR, 2.76; 1.2–6.4); meeting through friends was protective (AOR, 0.63;0.41–0.96). Meeting partners at own school was protective for both sexes (males: AOR, 0.33; 0.20–0.55; females: AOR, 0.65; 0.44–0.96).

Conclusions:

Although factors associated with a GC/CT infection differed between males and females in our sample, partner meeting place was associated with infection for both sexes. School-based screening programs could use this information to target high-risk students for effective interventions.

Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) infections are the 2 most commonly reported sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in the United States and disproportionately affect adolescents and minorities.1 In 2003, the Philadelphia Department of Public Health (PDPH) initiated a voluntary, school-based education and screening program intended to identify and treat CT and GC infections among the adolescents attending Philadelphia public high schools. In the ensuing 10 years, the Philadelphia High School STD Screening Program (PHSSSP) provided an educational presentation to approximately 300,000 students, screened 126,053, and identified 8089 CT and GC infections, ensuring treatment for approximately 98% of them.

School-based screening programs have been shown to identify large pools of infected adolescents.2–5 A clearer understanding of the “risk space” that exists in American high schools as it pertains to STD acquisition and transmission could help inform the development of prevention programs targeting this population. In addition, further refinement of the epidemiology of GC/CT among this population and the development of tools that can identify students or schools that might most benefit from screening could help better target bacterial STD screening in school-based settings. Building on the robust structure of the PHSSSP, we collected additional sociodemographic and behavioral risk data to explore factors associated with a GC/CT diagnosis in students who choose to test in the program and to determine whether a simple method able to identify students or school populations who might benefit from testing could be developed.

METHODS

Between 2009 and 2012, students attending PHSSSP presentations submitted urine specimens, as previously described.2 All students who attended PHSSSP presentations were instructed to call PDPH for their test results in 1 week. Approximately one-third of students who tested subsequently called PDPH for their test results; numbers of CT/GC-positive and CT/GC-negative students who called were proportional to the total testing population. Students who called for results spoke directly to STD Control Program staff members. Those who tested negative for CT/GC were given their results; those who tested positive for CT/GC were given their results and advised to either receive treatment from their own physician or to receive treatment from PDPH treatment and counseling teams who returned to all schools to perform in-school treatment (typically within 2 weeks of testing date). CT/GC positive students who did not call for results were actively contacted by PDPH to arrange treatment. In-school treatment and counseling consisted of appropriate oral antibiotic therapy, condoms, and the elicitation of student risk behaviors and provision of Partner Services (obtaining partner contact information so that partners can be notified of their exposure) by trained disease intervention specialists (DISs). Risk behaviors were elicited so that appropriate, brief counseling by DIS could be provided.

Interviews and Interview Tool

To better explain factors associated with infection, additional risk questions were standardized into a brief face-to-face interview tool, used between 2009 and 2012. Questions were drawn from behaviors found to be associated with an increased risk of STD in youth6–10; sex partner meeting place questions were asked to determine potential locations for public health intervention. The tool contained 5 yes/no questions on history of arrest,6,11,12 prior STD diagnosis,13 and history of sex in the last 3 months14; 1 check-all-that-apply question about typical location of sex partner meeting place (own school, other school, Internet, neighborhood, friends, and other); and 1 question on age at first sex.9 Interviews were conducted at the time of in-school treatment during provision of partner services and counseling. Interview records of students who tested positive were cross-checked with reported STD history as recorded in the PDPH citywide STD surveillance database.

To collect information on students who were not infected with GC/CT, the same interview was conducted among a convenience sample of all students who tested negative in the PHSSSP, contacted PDPH to be given their negative results, and were asked to consent to interview in the 2011 to 2012 school year. If they did not consent, the call was ended. During the interview, the STD surveillance database was checked and any documented history of reportable STD was recorded on the interview sheet. Interviews for students who tested negative were recorded without personal identifiers and could not be traced back to individual students. This research study was approved by the institutional review board of the City of Philadelphia.

Data Analysis

Interview data were recorded in MS Access databases, and positive interviews were de-identified before analysis. Data analysis was performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). χ2 Tests of independence were used to compare students with and without GC/CT on demographic and behavioral factors; analyses were stratified by sex. Odds ratios (ORs) for each place where students met their partners were obtained using those who answered “no” to that place as the referent. All statistical tests were considered to be statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level. Multivariable logistic analyses using significant variables from the bivariate analysis were computed to obtain adjusted ORs (AORs). Significant bivariate variables were assessed for multicollinearity where highly correlated variables were selected for final inclusion in the model using the one that had the highest correlation to the outcome variable.

Risk Index

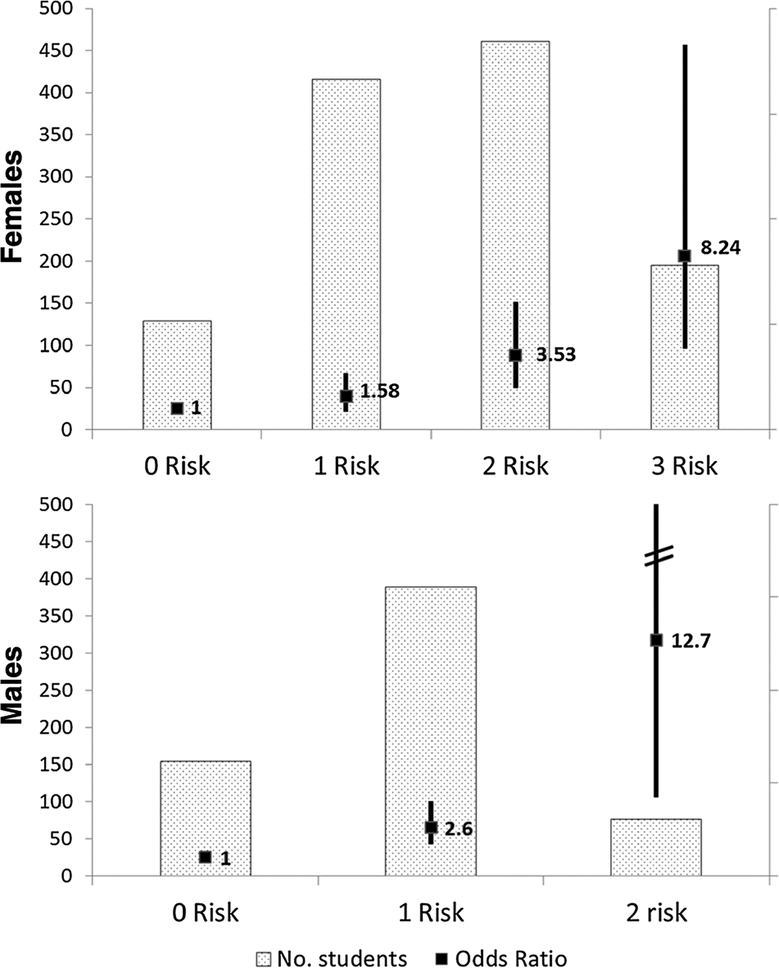

Simple index scores were calculated by summing the presence of a variable indicating risk that was obtained from the logistic regression. Each variable was assigned a value of 1. Risk scores were calculated by sex for all students that took the survey. The scores were validated with CT and/or GC infection status outcomes of the surveyed students. Odds ratios and confidence intervals were calculated (Fig. 1). Protective variables were not included in the index score calculations (SAS/STAT 9.2 User’s Guide, 2008; Logistic Regression Examples Using SAS® System, Version 6. 1995, Cary, NC).

Figure 1.

Risk Index. ORs of infection (black box) are compared with students of the same sex with 0 risk factors. Confidence intervals (CIs) are shown as solid black line; dotted bars indicate the number of students with given number of risk factors. ORs of females with 4 or 5 risk factors not shown, as none of the 21 females with 4 risks and 3 females with 5 risks were uninfected. CI for males with 2 risk factors was 4.22 to 52.98.

RESULTS

During the 3 school years examined, 34,448 students were tested and 2356 individuals tested positive for either GC or CT. Of these, 1489 (63.2%) were interviewed. In 2011 to 2012, 318 adolescents who tested CT/GC negative completed interviews out of 7930 students who tested negative (Table 1). There were no significant differences in the distribution of race, sex, or age at time of test among the population of all CT/GC positives (n = 2356) versus the interviewed positives (data not shown). When compared with the approximately 40,000 Philadelphia public high school students enrolled yearly (65.0% black, 16.0% white, 11.0 Hispanic, 6.0% Asian, and 51.2%female),2 interviewed students were more likely to be black (83.0% of positives and 75.5% of negatives) and female (65.7% of positives and 62.0% of negatives).

TABLE 1.

Demographics of Interviewed Positive and Negative Students Who Tested in the PHSSSP, 2009–2012*

| Positive Males (n = 503) | Negative Males (n = 119) | Positive Females (n = 977) | Negative Females (n = 199) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | ||||

| White | 8 (1.6) | 8 (6.7) | 34 (3.5) | 15 (7.5) |

| Black | 447 (88.9) | 89 (74.8) | 794 (81.3) | 151 (75.9) |

| Hispanic | 30 (6.0) | 18 (15.1) | 67 (6.9) | 23 (11.6) |

| Other | 5 (1.0) | 4 (3.4) | 21 (2.2) | 8 (4.0) |

| Unknown | 13 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 61 (6.2) | 2 (1.0) |

| Ever had sex | 495 (98.4) | 107 (89.9) | 976 (99.9) | 186 (93.5) |

| Age at first sex, y | ||||

| ≤14 | 361 (71.8) | 63 (52.9) | 469 (48.0) | 72 (36.2) |

| ≥15 | 123 (24.5) | 44 (37.0) | 486 (49.7) | 114 (57.3) |

| Never had sex | 4 (0.8) | 12 (10.1) | 1 (0.1) | 10 (5.0) |

| Sex in last 90 d | 457 (90.9) | 81 (68.1) | 856 (87.6) | 139 (69.9) |

| ≥2 partners in last 90 d | 241 (47.9) | 45 (37.8) | 203 (20.8) | 22 (11.1) |

| Previous reportable STD | 84 (16.7) | 12 (10.1) | 255 (26.1) | 26 (13.1) |

| Previous arrest | 176 (35.0) | 33 (27.7) | 163 (16.7) | 13 (6.5) |

| Previous pregnancy | N/A | N/A | 168 (17.2) | 22 (11.1) |

| Met partners… | ||||

| Own school | 149 (29.6) | 57 (47.9) | 240 (24.6) | 78 (39.2) |

| Through friends | 125 (24.9) | 43 (36.1) | 269 (27.5) | 67 (33.7) |

| Neighborhood | 263 (52.3) | 47 (39.5) | 175 (17.9) | 6 (3.0) |

| Other school | 45 (9.0) | 1 (0.8) | 56 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Internet | 36 (7.2) | 11 (9.2) | 18 (1.8) | 3 (1.5) |

| Other | 64 (12.7) | 8 (6.7) | 120 (12.3) | 6 (3.0) |

| More than 1 location | 146 (29.0) | 45 (37.8) | 157 (16.0) | 17 (8.5) |

Data are presented as n (%).

N/A indicates not available.

Behaviors thought to contribute to risk of STD were very common in all interviewed adolescents. More than half (55.6%) of males with a GC/CT infection reported young age at sexual debut (e14 years); 47.4% of females with a GC/CT infection also reported this behavior. Having had 2 or more sexual partners in the past 3 months was more commonly reported by males with a GC/CT infection (47.9%; range, 2–20 partners) than by females with a GC/CT infection (20.8%; range, 2–6 partners). A history of arrest was reported in 35.0% of males with a GC/CT infection and 16.7% of females with a GC/CT infection. Pregnancy (including current pregnancy) had occurred in 17.2% of females with a GC/CT infection (compared with 11.1% of negative females). Most adolescents (both infected and not) met their partners either in their own school (44.7%), in their neighborhood (32.1%), or through friends (34.6%); other venues were far less common. Males were more likely than females to report meeting partners in more than 1 location (positive males 29.0%, negative males 37.8%; positive females 16.0%, negative females 8.5%).

Results of bivariate and multivariable analyses are shown in Table 2. Among females, factors significantly associated with GC/CT infection were black (compared with white) race (OR, 2.32), age of ≤14 years at first sex (OR, 1.51), 2 or more partners (compared with 1 partner) in the past 3 months (OR, 1.81), history of reportable STD (OR, 2.30), and history of arrest (OR, 2.84). Among males, factors significantly associated with infection were black race (OR, 5.02) and young age at first sex (OR, 2.05). Having had no partners in the last 3 months or never having had sex was protective among both males (ORs, 0.23 and 0.21, respectively) and females (ORs, 0.48 and 0.09, respectively).

TABLE 2.

Univariate and Multivariate ORs of STD Risk in Positive Versus Negative Students by Sex

| Male | Female | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95%CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | AOR | 95% CI | P | |

| Risk | ||||||||||||

| Race | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | ||||||||||

| Hispanic | 1.67 | 0.53–5.22 | 1.29 | 0.60–2.78 | ||||||||

| Asian | 1.25 | 0.24–6.44 | 1.16 | 0.42–3.20 | ||||||||

| Black | 5.02 | 1.84–13.74* | 2.32 | 1.23–4.36* | 2.27 | 1.124.58 | 0.034 | |||||

| White (referent) | ||||||||||||

| Ever had sex† | 13.88 | 4.39–43.86* | <0.0001 | 17.49 | 4.77–64.16* | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Age at first sex | <0.0001 | <0.0001* | ||||||||||

| Never had sex | 0.21 | 0.08–0.56* | 0.09 | 0.03–0.30* | 0.13 | 0.026–0.67 | 0.0088 | |||||

| Age ≤14 y | 2.05 | 1.33–3.17* | 1.99 | 1.21–3.26 | 0.0018 | 1.51 | 1.09–2.08* | ‡ | ||||

| Age ≥15 y (referent) | ||||||||||||

| Sex in last 90 d† | 5.25 | 3.21–8.58 | <0.0001* | 3.00 | 2.09–4.31 | <0.0001* | ||||||

| Partners in last 90 d | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | ||||||||||

| ≥2 partners | 1.1 | 0.68–1.77 | 1.81 | 1.12–2.92* | 1.75 | 1.05–2.91 | 0.0014 | |||||

| No partners | 0.23 | 0.13–0.40* | 0.22 | 0.11–0.45 | <0.0001 | 0.48 | 0.32–0.70 | 0.57 | 0.37–0.90 | 0.0005 | ||

| 1 partner (referent) | ||||||||||||

| Previous reportable STD | 1.81 | 0.96–3.44 | 0.0655 | 2.30 | 1.49–3.56 | <0.0001* | ||||||

| Previous arrest | 1.44 | 0.93–2.24 | 0.10 | 2.84 | 1.58–5.10 | <0.0003* | 2.26 | 1.22–4.21 | 0.0097 | |||

| Previous pregnancy | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.68 | 1.05–2.70 | 0.0297* | ||||||

| Places met partners | ||||||||||||

| Own school | 0.39 | 0.26–0.59 | <0.0001* | 0.33 | 0.20–0.55 | <0.0001 | 0.54 | 0.39–0.74 | 0.0001* | 0.65 | 0.44–0.96 | 0.0294 |

| Through friends | 0.63 | 0.41–0.96 | 0.032* | 0.55 | 0.34–0.91 | 0.0194 | 0.81 | 0.58–1.12 | 0.20 | |||

| Neighborhood | 1.85 | 1.23–2.78 | 0.003* | 2.23 | 1.59–3.12 | <0.0001* | 1.92 | 1.29–2.86 | 0.0013 | |||

| Other school§ | 12.24 | 1.67–89.75 | 0.0017* | 26.09 | 1.61–424.02 | 0.0004* | ||||||

| Internet§ | 0.80 | 0.40–1.63 | 0.54 | 1.31 | 0.38–4.49 | 0.67 | ||||||

| Other§ | 2.14 | 1.00–4.60 | 0.046* | 4.82 | 2.09–11.12 | <0.0001* | ||||||

| More than one location¶ | 0.72 | 0.47–1.09 | 0.119 | 2.07 | 1.23–3.51 | 0.0056* | ||||||

| All other | 4.04 | 1.91–8.53 | 0.0001* | 2.76 | 1.20–6.36 | 0.0175 | 7.52 | 3.28–17.23 | <0.0001* | 9.44 | 3.70–24.09 | <0.0001 |

Significant on univariate analysis.

“Ever had sex,” “age at first sex,” and “sex in last 90 days” highly correlated; only “age at first sex” included in multivariate analysis.

Borderline significant.

Combined to form “all other” variable used in multivariate analysis.

Not included in multivariate analysis because of confounding.

N/A indicates not available.

Locations where adolescents met their partners were consistently associated with STD in both males and females. Meeting a partner in their own school was protective among both males (OR, 0.39) and females (OR, 0.54), whereas meeting a partner in their neighborhood was associated with increased odds of GC/CT diagnosis in both males (OR, 1.85) and females (OR, 2.23). Meeting a partner through friends was protective among males (OR, 0.63), but was not significantly associated with GC/CT diagnosis in females. Few students reported meeting partners in other venues; however, meeting partners in another school or “other” venue was associated with infection in both males (ORs, 12.24 and 2.14) and females (ORs, 26.09 and 4.82). When responses from those who met partners at another school, on the Internet, or “other” were combined, the resulting variable (“all other”) was highly associated with infection in both males (OR, 4.04) and females (OR, 7.52). Meeting partners in more than 1 location was associated with infection in females only (OR, 2.07).

On multivariable analysis, variables associated with infection in females included black race (AOR, 2.27), higher partner number (AOR, 1.75), history of arrest (AOR, 2.26), meeting partners in the neighborhood (AOR, 1.92), and particularly meeting a partner in “all other” venues (AOR, 9.44). In males, meeting a partner in “all other” venues (AOR, 2.76) and earlier sexual debut (AOR, 1.99) continued to be associated with infection. When compared with sexual debut at age 15 years or greater, females who reported never having had sex were significantly less likely to have an infection (AOR, 0.13); sexual debut at age 14 years or earlier was associated with infection, but statistical significance was borderline. Having reported no sexual partners within the past 3 months was associated with decreased risk of infection in both males (AOR, 0.22) and females (AOR, 0.57), as was meeting partners at their own school (for males: AOR, 0.33; for females: AOR, 0.65). For males, meeting partners through their friends remained protective (AOR, 0.55).

Risk Index

When compared with males with no risk factors, males with 1 risk factor were 2.60 times as likely to be infected, and males with 2 risk factors were 12.67 times as likely to be infected. Females with 1, 2, and 3 risk factors were 1.58, 3.53, and 8.24 times as likely to be infected when compared with those without risk factors. No uninfected females had 4 or 5 risk factors, whereas 21 infected females had 4 and 2 had 5, so OR could not be computed (Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

In this population of urban public high school adolescents testing in a large school-based CT/GC screening program, we found that the places where students met their sex partners were consistently associated with risk of infection in both males and females, even after adjusting for sociodemographic factors. Our study is similar to others that have found an association with STD and early age at sexual debut (males, borderline significant for females),9 history of arrest (females only),6,11,15 black race (females only),16 and higher partner number (females only).17 However, we found that a history of CT or GC infection did not predict current infection, an association found by some previous studies18,19 but not by others.13 In addition, we were able to construct a simple risk index demonstrating increasing odds of infection with increasing numbers of risk factors in both males and females.

In the population we sampled, male and female students who met partners at their own school were less likely to be infected with CT or GC. Meeting partners through friends was also protective for males, whereas meeting a partner in their neighborhood was significantly risky for females only. Similar data exist for adolescents in Chicago and San Francisco, where it was most common for adolescents to meet their sex partners at their own school or through friends, and where these venues were less likely to result in a risky partner (i.e., a partner who was age discordant, casual, or more likely to use alcohol before sex).20,21 In these studies, partner-meeting venues were associated with differences in risky behavior, such as age- and risk-discordant partnerships, but unlike our study, these other studies did not link this behavior to actual STD outcomes.

Partner meeting places may determine entrance into particular sexual networks.20,22 Our finding that females who meet partners in their neighborhood are at increased STD risk may, in part, be because adolescent females can easily attract the attention of older neighborhood males21; adolescent girls with older male partners are more likely than other girls to be younger at first sex23 and use condoms inconsistently.23,24 Older male partners are also more likely to have concurrent partners and may pose additional risk of STD acquisition to members of their sexual network, possibly through involvement in drug markets or other activities of the underground economy.10,23,25 In addition, we can not exclude a protective effect of having in-school sexual health services (the PHSSSP) available to partners who meet in school but not in the neighborhood. Interestingly, in our analysis, both male and female adolescents who met their partners in “all other” venues had the highest risk of STD of all, which may suggest small, but dense and high prevalence networks. In addition, we found that female adolescents who met their partners in more than 1 location were also at significantly increased odds of infection.

This analysis provides several new insights into behaviors that may pose a risk for CT/GC infection in urban adolescents. Most importantly, we provide biological validation of the hypothesis that the venues where adolescents meet their sex partners are determinants of risk for STD. Findings are limited by several factors. Sex was not specifically defined or analyzed as oral, anal, or vaginal sex. Students who tested positive were asked about past behaviors and multiple DISs performed the interviews; answers are therefore subject to recall and interviewer bias. Students may also have intentionally minimized socially stigmatizing behavior to interviewers. However, we would expect both positive and negative students to have minimized behavior, and therefore, the ORs are less likely to have changed. Students who tested positive were interviewed in person, whereas students with negative results were interviewed over the telephone; students may have been more or less likely to disclose risky behavior in person. However, if in-person interviews increase social desirability bias, we may have underestimated the actual difference between infected and uninfected students. The uninfected students were interviewed in a different year from some of the infected students. However, we found that the demographics and risk behaviors of the positive students from year to year, so it is unlikely that the responses of the negative students would be very different. Interviews from negative students were obtained via a convenience sample; individuals who consented to a telephone interview may behave differently from those who did not call in for results or did not consent to interview. However, students who call in may well be more worried about their test results than those who do not, possibly due to risky behavior; if this were the case, the magnitude of the difference between students who tested positive and students who tested negative might be even larger than shown by our study. In addition, a small percentage of uninfected students were interviewed, and we do not have data to examine how this small sample may or may not differ from the larger pool of students who were not diagnosed as having GC or CT in our screening program. Lastly, adolescents may feel social pressure to overreport or underreport sexual behavior.26 However, questions about partner meeting place seem unlikely to be perceived as sensitive or stigmatizing, so responses to these questions and their significant association with infection likely remain valid.

To date, school-based STD screening programs have not been shown to decrease prevalence of STD in the school population.4,25,27,28 Importantly, in our analysis less than half of all students in our study reported meeting partners at their own school, which may highlight the inability of screening programs to target the partners of infected students. If this were true in all schools, school screening programs by their nature may be unable to target most partners of those being screened. Indeed, longitudinal data from the PHSSSP do not demonstrate a reduction in the yearly percentage of students who test positive; in fact, the percentage of students who tested positive for CT and GC in the PHSSSP increased from 5.3% in 2003 to 6.6% in 2009 (when the current project was planned),27 and overall reported rates of CT and GC among Philadelphians aged 15 to 24 years has also increased since 2003.29 During this analysis, from 2009 to 2012, the average percent positivity in the PHSSSP remained consistent, at 9.9% (range, 9.7%−10.1%) for females and 4.3% (range, 3.9%−4.5%) for males.

However, our study also demonstrates the potential for a school screening program to identify students at increased risk for STD. The Risk Index we have constructed is an easy tool that, if validated, could be used by adolescent screening programs to identify and target high-risk students for condom distribution, rescreening reminders, or high-quality behavioral interventions, or to identify schools where there is a large percentage of students with high index scores. In addition, our study identifies behaviors that could be targeted by public health messages, such as informing adolescents about the risks of partners from nonschool venues (the neighborhood). School screening programs such as the PHSSSP provide an opportunity to disseminate these or other effective prevention messages during their presentations.

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest identified for any of the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 2011. December 2012; Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats11/Surv2011.pdf.

- 2.Asbel L, Newbern E, Salmon M, et al. School-based screening for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae Among Philadelphia public high school students. Sex Transm Dis 2006; 33:614–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen D, Nsuami M, Martin D, et al. Repeated school-based screening for sexually transmitted diseases: A feasible strategy for reaching adolescents. Pediatrics 1999; 104:1281–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nsuami M, Nsa M, Brennan C, et al. Chlamydia positivity in New Orleans public high schools, 1996–2005: Implications for clinical and public health practices. Acad Pediatr 2013; 13:308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mettey A, Anschuetz G, Lewis F, et al. Seven Years, 112,000 Tests Later: Trends From the Philadelphia High School STD Screening Program, in National STD Prevention Conference. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devieux J, Malow R, Stein J, et al. Impulsivity and HIV risk among adjudicated alcohol- and other drug-abusing adolescent offenders. AIDS Educ Prev 2002; 14(5 suppl B):24–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bunnell R, Dahlberg L, Rolfs R, et al. High prevalence and incidence of sexually transmitted diseases in urban adolescent females despite moderate risk behaviors. J Infect Dis 1999; 180:1624–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halfors D, Iritani B, Miller W, et al. Sexual and drug behavior patterns and HIV and STD racial disparities: The need for new directions. Am J Public Health 2007; 97:125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaestle C, Halpern C, Miller W, et al. Young age at first sexual intercourse and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. Am J Epidemiol 2005; 161:774–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Begley E, Crosby R, DiClemente R, et al. Older partners and STD prevalence among pregnant African American teens. Sex Transm Dis 2003; 30:211–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horvath P, Zuckerman M. Sensation seeking, risk appraisal, and risky behavior. Pers Individ Diff 1993; 14:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spitalnick J, DiClemente R, Wingood G, et al. Brief Report: sexual sensation-seeking and its relationship to risky sexual behavior among African-American adolescent females. J Adolesc 2007; 30:165–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DiClemente R, Wingood G, Sionean C, et al. Association of adolescents’ history of sexually transmitted disease (STD) and their current high-risk behavior and STD status: A case for intensifying clinic-based prevention efforts. Sex Transm Dis 2002; 29:503–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dean D, Suchland R, Stamm W. Evidence for long-term cervical persistence of Chlamydia trachomatis by omp-1 genotyping. J Infect Dis 2000; 182:909–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swartzendruber A, Sales J, Brown J, et al. Predictors of repeat Chlamydia trachomatis and/or Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections among African-American adolescent women. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89:76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seidman S, Aral S. Subpopulation differentials in STD transmission. Am J Public Health 1992; 82:1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joffe G, Foxman B, Schmidt A, et al. Multiple partners and partner choice as risk factors for sexually transmitted disease among female college students. Sex Transm Dis 1992; 19:272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anschuetz GL, Beck JN, Asbel L, et al. Determining risk markers for gonorrhea and chlamydial infection and reinfection among adolescents in public high schools. Sex Transm Dis 2009; 36:4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salerno J, Darling-Fisher C, Hawkins N, et al. Identifying relationships between high-risk sexual behaviors and screening positive for chlamydia and gonorrhea in school-wide screening events. J School Health 2013; 83:99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Staras S, Maldonado-Molina M, Livingston M, et al. Association between sex partner meeting venues and sexual risk taking among urban adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2012; 51:566–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J, Jennings J, Ellen J. Discordant sexual partnering: a study of high-risk adolescents in San Francisco. Sex Transm Dis 2003; 30: 234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doherty I, Padian N, Marlow C, et al. Determinants and consequences of sexual networks as they affect the spread of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis 2005; 191(Suppl 1):S42–S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein C, Kaufman J, Ford C, et al. Partner age difference and prevalence of chlamydial infection among young adult women. Sex Transm Dis 2008; 35:447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DiClemente R, Wingood G, Crosby R, et al. Sexual risk behaviors associated with having older sex partners. Sex Transm Dis 2002; 29:20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jennings J, Taylor R, Salhi R, et al. Neighborhood drug markets: A risk environment for bacterial sexually transmitted infections among urban youth. Soc Sci Med 2012; 74:1240–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenbaum J Truth or consequences: The intertemporal consistency of adolescent self-report on the Youth Behavior Risk Survey. Am J Epidemiol 2009; 169:1388–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis F, Mettey A, Anschuetz G, et al. Risk Assessment in a Large Cohort of Urban Public High School Students Infected With CT or GC—Philadelphia, 2009–2010 Quebec, Canada: International Society for Sexually Transmitted Disease Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisman D, Spain C, Salmon M, et al. The Philadelphia High School STD Screening Program: Key insights from dynamic transmission modeling. Sex Transm Dis 2008; (Suppl 35):S61–S68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.City of Philadelphia, Division of Disease Control, Annual Report. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Department of Public Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]