Abstract

Clausena lansium Lour. Skeels (Rutaceae) is widely distributed in South China and has historically been used as a traditional medicine in local healthcare systems. Although the characteristic components (carbazole alkaloids and coumarins) of C. lansium have been found to possess a wide variety of biological activities, little attention has been paid toward the other components of this plant. In the current study, phytochemical analysis of isolates from a water-soluble stem and leaf extract of C. lansium led to the identification of 12 compounds, including five aromatic glycosides, four sesquiterpene glycosides, two dihydrofuranocoumarin glycosides, and one adenosine. All compounds were isolated for the first time from the genus Clausena, including a new aromatic glycoside (1), a new dihydrofuranocoumarin glycoside (6), and two new sesquiterpene glycosides (8 and 9). The phytochemical structures of the isolates were elucidated using spectroscopic analyses including NMR and MS. The existence of these compounds demonstrates the taxonomic significance of C. lansium in the genus Clausena and suggests that some glycosides from this plant probably play a role in the anticancer activity of C. lansium to some extent.

Keywords: Clausena lansium, aromatic glycosides, sesquiterpene glycosides, dihydrofuranocoumarin glycosides

1. Introduction

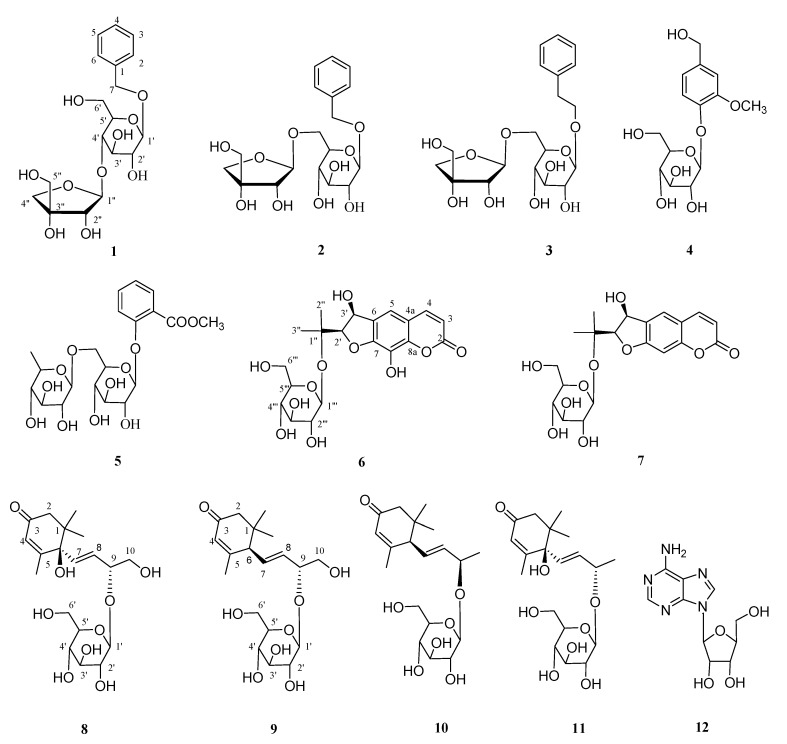

The genus Clausena (Rutaceae) is comprised of approximately 30 species that are scattered throughout the subtropical and tropical regions, including China, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines [1,2]. There are approximately 10 species as well as 2 varieties in China, which appear in Southern China. Clausena lansium Lour. Skeels (Rutaceae), belonging to the genus Clausena of the family Rutaceae, is a fruit tree and a species of strongly scented evergreen tree growing in South China [1,2]. C. lansium is famous for their fruits, which are usually very popular tropical, health-promoting fruits, while their roots, stems, leaves, and seeds have also been extensively applied in folk medicine or traditional Chinese medicine for the treatments of abdominal pain, malaria, cold, dermatopathy, and snake bites [2,3]. Various biological studies, on the alkaloids, coumarins, and sesquiterpenes from this plant have reported the neuroprotective [4,5], antitumor [6,7], hepatoprotective [8], anti-inflammatory [9], antifungal [10], antioxidant [11], antiobesity [12], nematicidal [13], antimicrobial [14], and hypoglycemic [15] effects of the C. lansium. In our previous studies, some carbazole alkaloids [16] and coumarins [17] were separated from the stem and leaf of C. lansium. As a part of our ongoing research into the natural products possessing structural and biological diversity from C. lansium, a systematic phytochemical study on the stem and leaf of C. lansium was accordingly carried out. The investigation resulted in the separation and characterization of five aromatic glycosides (1–5), two dihydrofuranocoumarin glycosides (6,7), four sesquiterpene glycosides (8–11), and one adenosine (12) (Figure 1). All compounds were isolated for the first time from the genus Clausena, including a new aromatic glycoside (1), a new dihydrofuranocoumarin glycoside (6), and two new sesquiterpene glycosides (8 and 9). The molecular structures of new compounds were established using comprehensive spectroscopic studies. The known compounds were determined by comparing their experimental data with those described in the literature. The existence of these compounds demonstrates the taxonomic significance of C. lansium in the genus Clausena and suggests that some glycosides from this plant probably play a role in the anticancer activity of C. lansium to some extent.

Figure 1.

The chemical structures of compounds 1–12 from the stem and leaf of Clausena lansium.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Elucidation of Chemical Structures of Four New Compounds 1,6,8,9

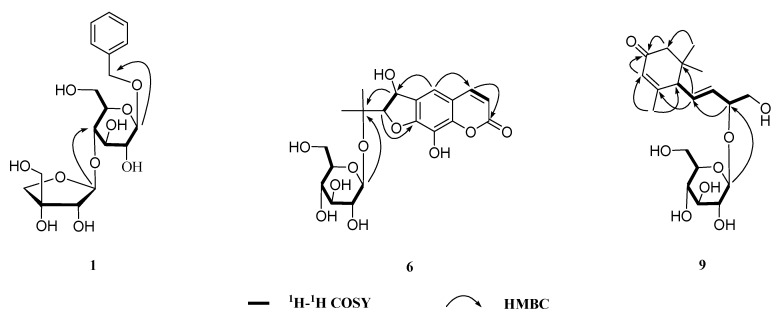

Claulanaroside (1) was obtained as a white amorphous powder, and its elemental composition was determined to be C18H26O10 by HRESIMS m/z: 425.1623 (Calculated for: [C18H26O10 + Na]+, 425.1628) with 6 degrees of unsaturation. The Infrared Radiation (IR) spectrum exhibited absorptions for hydroxyl groups (3441 and 1062 cm−1) and the aromatic ring (1618, 1547, and 1498 cm−1). The 1H NMR data of 1 (Table 1) showed clear signals for five aromatic protons (δH 7.31 (2H, d, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.23 (2H, m), and 7.18 (1H, d, J = 7.3)), indicating a monosubstituted benzene ring in 1. The 13C-NMR spectroscopic data (Table 1) showed the presence of a six-carbon sugar (δC 100.8, 77.2, 76.6, 76.5, 70.3, and 61.4), a five-carbon sugar (δC 109.3, 79.2, 77.6, 73.9, and 64.6), a benzene ring (δC 137.6, 127.8, 127.8, 127.9, 127.9, and 127.3) and an oxymethylene (δC 70.4). Coupled with the above evidence, comparison of the 1H- and 13C NMR data of 1 and icariside F2 [18] implied that the aglycone of 1 was methylbenzene and the C-7 position was glycosylated. Acid hydrolysis of 1 afforded d-glucose and d-apiose, which were detected by derivatization and HPLC analysis [19,20]. The anomeric configurations of monosaccharide units were confirmed to be β for the d-glucose and d-apiose according to their 3JH1-H2 coupling constants (7–8 and 2–3 Hz, respectively) [18,21,22]. Detailed comparison of the NMR data of 1 with those of icariside F2 revealed that the positions of the β-d-apiofuranosyl linkage were different in 1 and icariside F2. The β-d-apiofuranosyl was located at C-4′ of the β-d-glucopyranosyl of 1 from the HMBC spectrum (Figure 2), which showed that H-1″ (δH 5.27) was correlated to C-4′ (δC 76.6), according to the β-d-glucopyranosylation-induced downfeld shift on the α-carbon [23]. The above deduction was further supported by downfeld shift observed for C-4′ (δC 76.6 ppm) and upfeld shift for C-6′ (δC 61.4 ppm) in 1. Consequently, compound 1 was identified as a methylbenzene-7-O-β-d-apiofuranosyl-(1→4)-O-β-d-glucopyranoside and named as claulanaroside, as shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) and 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) spectroscopic data of 1.

| Position | δH (J in Hz) | δ C | Position | δH (J in Hz) | δ C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 137.6 (s) | 4′ | 3.84 (m) | 76.6 (d) | |

| 2 | 7.31 (d, 7.2) | 127.8 (d) | 5′ | 3.51 (m) | 77.2 (d) |

| 3 | 7.23 (m) | 127.9 (d) | 6′ | 3.78 (m) | 61.4 (t) |

| 4 | 7.18 (d, 7.3) | 127.3 (d) | 3.60 (m) | ||

| 5 | 7.23 (m) | 127.9 (d) | 1″ | 5.27 (d, 2.1) | 109.3 (d) |

| 6 | 7.31 (d, 7.2) | 127.8 (d) | 2″ | 3.31 (m) | 77.6 (d) |

| 7 | 4.56 (d,11.6) | 70.4 (t) | 3″ | 79.2 (s) | |

| 4.80 (d,11.6) | 4″ | 3.81 (m) | 73.9 (t) | ||

| 1′ | 4.30 (d,7.5) | 100.8 (d) | 3.55 (m) | ||

| 2′ | 3.16 (m) | 76.5 (d) | 5″ | 3.45 (d, 12.2) | 64.6 (t) |

| 3′ | 3.38 (m) | 70.3 (d) | 3.41 (d, 12.2) |

Figure 2.

Some key HMBC and 1H–1H COSY correlations of 1, 6, and 9.

Claulancoumside (6) was obtained as a white powder crystallization with a blue fluorescence under the ultraviolet lamp (254 nm). The structure of 6 was deduced for one new dihydrofuranocoumarin glycoside mainly by its blue fluorescence and experimental data. In the 1H NMR spectrum (Table 2), the resonance characteristics for a cis-double bond (δH 7.91 (1H, d, J = 9.5 Hz) and 6.25 (1H, d, J = 9.5 Hz)) and a singlet aromatic proton (δH 7.21 (1H, s)), coupled with the blue fluorescence, suggested the presence of a trisubstituted coumarin skeleton in 6 [24,25,26]. The 13C-NMR spectrum (Table 2) of 6 showed 20 C-atom signals, including a coumarin skeleton (δC 161.3, 150.1, 144.9, 144.1, 129.3, 127.8, 114.3, 113.8, and 110.7), a six-carbon sugar (δC 97.2, 76.1, 75.6, 73.1, 69.3, and 59.9), two oxymethines (δC 91.5 and 71.1), two methyls (δC 23.3 and 22.2), and an oxygenated quaternary carbon (δC 77.5 (s)). The 1H and 13C NMR data of 6 and 8-hydroxysmyrindiol [24] demonstrated that the aglycone of 6 was equivalent to 8-hydroxysmyrindiol and the C-1″ position of 6 was glycosylated, which was further confirmed by the HMBC correlation (Figure 2) from H-1‴ to C-1″ and the downfeld shift observed for C-1″ (δC 77.5 ppm) in 6 [23]. Acid hydrolysis and HPLC analysis of 6 afforded a d-glucose [19,20]. The anomeric configuration of the d-glucose was confirmed to be β according to its large 3JH1-H2 coupling constants (J = 7.5 Hz) [25,26]. In addition, coupled with the 1H-1H COSY (Figure 2) correlations of H-2′/H-3′, a large vicinal coupling constant (6.5 Hz) of two doublets at δH 4.57 (H-2′) and 5.35 (H-3′) supported the cis orientation. The absolute configurations of 6 at C-2′ and C-3′ were established by comparing its specific rotation with 1′-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl-(2S,3R)-3-hydroxynodakenetin (−14.0° (pyridine; c 0.5)) [25] and 1′-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl (2R,3S)-3-hydroxynodakenetin ( +15.1° (MeOH; c 0.05)) [26]. With a specific rotation value of +24.3 (MeOH; c 1.1), compound 6 was assigned to the 2′R,3′S configurations. Therefore, compound 6 was deduced as a 1″-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl (2′R,3′S)-3′,8-dihydroxyarmesin and named as claulancoumside, as shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) and 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) spectroscopic data of 6.

| Position | δH (J in Hz) | δ C | Position | δH (J in Hz) | δ C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 161.3 (s) | 1″ | 77.5 (s) | ||

| 3 | 6.25 (d, 9.5) | 110.7 (d) | 2″ | 1.64 (3H, s) | 23.3 (q) |

| 4 | 7.91 (d, 9.5) | 144.9 (d) | 3″ | 1.63 (3H, s) | 22.2 (q) |

| 4a | 113.8 (s) | 1‴ | 4.85 (d, 7.5) | 97.2 (d) | |

| 5 | 7.21 (s) | 114.3 (d) | 2‴ | 3.16 (m) | 73.1 (d) |

| 6 | 127.8 (s) | 3‴ | 3.41 (m) | 76.1 (d) | |

| 7 | 150.1 (s) | 4‴ | 3.40 (m) | 69.3 (d) | |

| 8 | 129.3 (s) | 5‴ | 3.19 (m) | 75.6 (d) | |

| 8a | 144.1 (s) | 6‴ | 3.50 (m) | 59.9 (t) | |

| 2′ | 4.57 (d, 6.5) | 91.5 (d) | 3.17 (m) | ||

| 3′ | 5.35 (d, 6.5) | 71.1 (d) |

Clausesquiside A (8) was obtained as an amorphous powder with −113.4° (MeOH; c 0.68). The UV spectrum showed absorption maxima at 237 nm. The IR spectrum indicated the presence of carbonyl (1668 cm−1) and hydroxyl (3447 and 1043 cm−1) groups. The 1H NMR spectrum of 8 (Table 3) showed two trans-olefinic protons (δH 6.92 (1H, dd, J = 15.6 Hz) and 5.79 (1H, dd, J = 15.6, 7.4 Hz)), one olefinic proton singlet (δH 5.85 (1H, s)), and three methyl singlets (δH 1.91 (3H, s), 0.95 (3H, s), and 0.93 (3H, s)). The 13C NMR spectrum of 8 (Table 3) exhibited a ketonic carbonyl at δC 199.5; four olefinic carbons at δC 165.3, 133.9, 127.0, and 125.3; an oxymethine at δC 77.6; an oxygenated quaternary carbon at δC 78.4; an oxymethylene at δC 64.1; three methyls at δC 22.9, 21.6, and 17.7; a quaternary carbon at δC 40.5; a methylene at δC 48.8; and a six-carbon sugar at δC 99.5, 76.2, 76.2, 73.0, 69.6, and 60.8. The 1H and 13C NMR spectral data of 8 were very similar to those of (6R,9R)-roseoside [27], differing only in the presence of an oxymethylene at δC 64.1 in 8, instead of a methyl at δC 21.2 that is found in (6R,9R)-roseoside. The absolute configuration at the 6-position in 8 was determined to be R, judging from the negative and positive Cotton effects at 241 and 322 nm, respectively, in the CD spectrum [27]. The β-d-glucopyranosylation-induced shift-trend rule suggested the absolute configuration at the 9-position of 8 to be R [23,28], which was further supported by the remarkable chemical shift difference between C-7 (δC 133.9) and C-8 (δC 127.0) of 8, as shown in [27]. So, compound 8 was elucidated as a (6R,9R,4Z,7E,)-6,9,10-trihydroxy-4,7-megastigmadien-3-one-9-O-β-d-glucopyranoside and named as clausesquiside A, as shown in Figure 1.

Table 3.

1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) and 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) spectroscopic data of 8 and 9.

| Position | 8 | Position | 9 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH (J in Hz) | δ C | δH (J inHz) | δ C | ||

| 1 | 40.5 (s) | 1 | 36.8 (s) | ||

| 2 | 2.61 (d, 16.6) | 48.8 (t) | 2 | 2.48 (d, 15.8) | 48.4 (t) |

| 2.16 (d, 16.6) | 2.11 (d, 15.8) | ||||

| 3 | 199.5 (s) | 3 | 200.8 (s) | ||

| 4 | 5.85 (s) | 125.3 (d) | 4 | 5.79 (br s) | 124.9 (d) |

| 5 | 165.3 (s) | 5 | 164.3 (s) | ||

| 6 | 78.4 (s) | 6 | 2.72 (d, 9.8) | 57.1 (d) | |

| 7 | 6.92 (dd, 15.6, 6.3) | 127.0 (d) | 7 | 5.82 (dd, 15.4, 9.8) | 130.7 (d) |

| 8 | 5.79 (dd, 15.6, 7.4) | 133.9 (d) | 8 | 5.55 (dd, 15.4, 7.1) | 132.1 (d) |

| 9 | 4.45 (m) | 77.6 (d) | 9 | 4.30 (m) | 78.2 (d) |

| 10 | 3.60 (dd, 11.8, 4.2) | 64.1 (d) | 10 | 3.61 (dd, 11.6, 4.1) | 64.6 (t) |

| 3.57 (dd, 11.8, 4.2) | 3.57 (dd, 11.6, 4.1) | ||||

| 11 | 0.95 (3H, s), | 21.6 (q) | 11 | 0.93 (3H, s), | 26.7 (q) |

| 12 | 0.93 (3H, s), | 22.9 (q) | 12 | 0.88 (3H, s), | 26.2 (q) |

| 13 | 1.91 (3H, s), | 17.7 (q) | 13 | 2.04 (3H, s), | 22.6 (q) |

| 1′ | 4.26 (d, 7.6) | 99.5 (d) | 1′ | 4.21 (d, 7.3) | 99.9 (d) |

| 2′ | 3.25 (m) | 73.0 (d) | 2′ | 3.32 (m) | 73.5 (d) |

| 3′ | 3.24 (m) | 76.2 (d) | 3′ | 3.25 (m) | 76.7 (d) |

| 4′ | 3.23 (m) | 69.6 (d) | 4′ | 3.22 (m) | 70.2 (d) |

| 5′ | 3.13 (m) | 76.2 (d) | 5′ | 3.14 (m) | 76.7 (d) |

| 6′ | 3.81 (dd, 11.2, 2.1) | 60.8 (t) | 6′ | 3.73 (dd, 12.1, 2.2) | 61.3 (d) |

| 3.64 (dd, 11.2, 2.1) | 3.68 (dd, 12.1, 2.2) | ||||

Clausesquiside B (9), a yellowish amorphous powder, possessed the virtually identical NMR (Table 3) and MS data as opuntiside A [29]. Its plane structure is determined by the HMBC and 1H-1H COSY spectrums (Figure 2). The CD data (321 (Δε –7.1), 254 (Δε +186.2) nm) showed a positive maximum at 254 nm, which was identical to the CD data of opuntiside A, indicating that the C-6 of 9 had an absolute R-configuration. According to the β-d-glucopyranosylation-induced shift-trend rule [23,28], the absolute configuration of C-9 was deduced for R from the downfeld shift observed for C-9 (δC 77.6 ppm). Based upon the results of the combined spectroscopic analyses, the structure of this compound 9 was established as (6R,9R,4Z,7E)-9,10-dihydroxy-4,7-megastigmadiene-3-one-9-O-β-d-glucopyranoside and named as clausesquiside B. As a result, the absolute structure of 9 at C-9 was substantiated for the first time in this study.

2.2. Structural Identification and Function of the Known Compounds 2–5,7,10–12

Comparing the experimental data of the known compounds with those described in the literatures, the phytochemical structures of the eight known compounds were identified as: Icariside F2 (2) [18], Icariside D1 (3) [30], Vanilloloside (4) [31], methyl benzoate-2-(6-O-α-l-rhanmopyranosyl)-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (5) [32], 1′-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl (2S,3R)-3-hydroxyarmesin (7) [24], (6R,9R,4Z,7E)-9,10-dihydroxy-4,7-megastigmadien-3-one-9-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (10) [33], (6R,9S)-Roseoside (11) [27], and adenosine (12) [34]. The eight known compounds were obtained from the genus Clausena for the first time, but the aglycone analogs of compounds 2–5,10,11 have been isolated from Clausena excavata [35,36] in our previous research about the phytochemical constituents of the genus Clausena, which may exhibit the chemical relationship between C. lansium and C. excavata. In addition, the analogs of compound 7 and its aglycone have been previously isolated from three different families such as Angelica archangelica (Apiaceae) [25], Pleurospermum rivulorum (Apiaceae) [26], Ferulago asparagifolia (Apiaceae) [37], Notopterygium incisum (Apiaceae) [38], Glehnia littoralis (Apiaceae) [39], Streblus indicus (Moraceae) [40], Dorstenia brasiliensis (Moraceae) [41], and Aegle marmelos (Rutaceae) [24], which may revealed a genetic relationship between the Apiaceae, Moraceae, and Rutaceae families. To the best of our knowledge, the phytochemical constituents of the plant are mainly affected by the genetic and environmental factors during plant growth, extraction, and isolation. Therefore, further phytochemical study on the water-soluble extract of C. lansium from different regions should be performed to achieve a full understanding of the chemical composition of C. lansium. As a predictable result, more and more chemical constituents will be used as evidence to support the taxonomic significance of C. lansium in the genus Clausena.

As mentioned in the introduction, as the characteristic components of the genus Clausena, the carbazole alkaloids and coumarins have been found to possess a variety of structures and biological activities [42,43]; however, little attention has been paid toward the other components of this plant, especially the water-soluble components. The current study demonstrates the presence of the aromatic glycosides, sesquiterpene glycosides, and coumarin glycosides. The carbazole alkaloids are considered to be the main anti-cancer components of the genus Clausena [6,7,44,45,46]. However, several reports demonstrated that the analogs of aromatic glycosides [47,48] and sesquiterpene glycosides [49] also possessed a certain degree of anti-cancer activity. Therefore, it is suggested that some glycosides from this plant probably play a role in the anticancer activity of C. lansium to some extent. At the same time, this also provides some clues about testing anticancer activity and expanding the biological scope of this work for our future research.

2.3. Characterization of Compounds 1–12

Claulanaroside (1): UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε): 218 (6.31), 265 (6.00), 294(5.76) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3441, 1618, 1547, 1498, 1248, 1062 cm−1; NMR data (SI 1–SI 5 in Supplementary Material) found in Table 1; positive ESIMS m/z: 425 [M + Na]+; HRESIMS m/z: 425.1623 (Calculated for: [C18H26O10 + Na]+, 425.1628).

Icariside F2 (2): ESIMS m/z: 425 [M + Na]+; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, MeOD): δ 7.44 (2H, d, J = 7.2 Hz, H-3,5), 7.35 (2H, m, H-2,6), 7.30 (1H, m, H-4), 5.08 (1H, d, J = 2.6 Hz, H-1″), 4.93 (1H, d, J = 12.0 Hz, H-7a), 4.66 (1H, d, J = 12.0 Hz, H-7b), and 4.35 (1H, d, J = 7.4 Hz, H-1′). 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ: 137.5 (s, C-1), 128.0 (d, C-2,6), 127.9 (d, C-3,5), 127.4 (d, C-4), 70.4 (t, C-7), 101.8 (d, C-1′), 73.6 (d, C-2′), 76.7 (d, C-3′), 70.5 (d, C-4′), 75.6 (d, C-5′), 67.3 (d, C-6′), 109.6 (d, C-1″), 76.6 (d, C-2″), 79.2 (s, C-3″), 73.7 (d, C-4″), and 64.2 (d, C-5″) (NMR spectrogram SI 6–SI 7 in Supplementary Material).

Icariside D1 (3): ESIMS m/z: 439 [M + Na]+; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, MeOD): δ: 7.29 (2H, J = 7.8 Hz, H-2,6), 7.28 (2H, m, H-3,5), 7.18 (1H, m, H-4), 5.04 (1H, d, J = 2.5 Hz, H-1″), 4.62 (1H, d, J = 7.7 Hz, H-1′), 4.31 (1H, m, H-8a), 3.83 (1H, m, H-8b), and 3.00 (2H, t, J = 7.3 Hz, H-7); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ: 138.2 (s, C-1), 127.5 (d, C-2,6), 128.1 (d, C-3,5), 125.3 (d, C-4), 35.4 (d, C-7), 69.9 (d, C-8), 102.5 (d, C-1′), 73.2 (d, C-2′), 76.2 (d,C-3′), 69.8 (d, C-4′), 75.0 (d, C-5′), 66.8 (d, C-6′), 109.1 (d, C-1″), 76.1 (d, C-2″), 78.6 (s, C-3″), 73.1 (d, C-4″), and 63.7 (d, C-5″) (NMR spectrogram SI 8–SI 9 in Supplementary Material).

Vanilloloside (4): ESIMS m/z: 339 [M + Na]+; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, MeOD): δ: 7.14 (lH, d, J = 8.2 Hz, H-5), 7.04 (lH, d, J = 2.1 Hz, H-2), 6.89 (lH, dd, J = 2.1, 8.2 Hz; H-6), 4.63 (1H, d, J = 7.4 Hz, H-1′), 4.56 (2H, s; H-7), and 3.97 (3H, s, OCH3); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ: 136.3 (s, C-1), 111.2 (d, C-2), 149.4 (s, C-3), 145.8 (s, C-4), 116.5 (d, C-5), 119.3 (d, C-6), 63.6 (t, C-7), 101.5 (d, C-1′), 76.8 (d, C-2′), 76.4 (d, C-3′), 73.5 (d, C-4′), 69.9 (d, C-5′), 61.1, (d, C-6′), and 55.3 (Q, OCH3) (NMR spectrogram SI 10–SI 14 in Supplementary Material).

Methyl benzoate 2-(6-O-α-l-rhanmopyranosyl)-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (5): ESIMS m/z: 483 [M + Na]+; 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ: 7.79 (1H, dd, J = 7.8, 1.6 Hz, H-3), 7.59 (1H, ddd, J = 8.4, 7.8, 1.6 Hz, H-5), 7.36 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H-6), 7.17 (1H, dd, J = 7.8, 7.8 Hz, H-4), 4.90 (1H, d, J = 7.3 Hz, H-1′), 4.67 (1H, d, J = 1.3 Hz, H-1″), 3.92 (1H, d, J = 9.8 Hz, Hb-6′), 3.91 (3H, s, H-8), 3.81 (1H, m, H-2″), 3.77 (1H, dd, J = 9.7, 3.4 Hz, H-3″), 3.70 (2H, m, Ha-6′, H-5″), 3.64 (2H, m, H-2′, H-4′), 3.62 (1H, t, J = 8.9 Hz, H-3′), 3.50 (1H, t, J = 9.1 Hz, H-5′), 3.35 (1H, t, J = 9.6 Hz, H-4″), and 1.14 (1H, d, J = 6.2 Hz, H-6″); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ: 157.2 (s, C-1), 120.9 (d, C-2), 130.8 (d, C-3), 122.3 (d, C-4), 133.8 (d, C-5), 117.5 (d, C-6), 167.1 (s, C-7), 102.3 (d, C-1′), 73.5 (d, C-2′), 75.8 (d, C-3′), 71.0 (d, C-4′), 76.2 (d, C-5′), 66.53 (t, C-6′), 100.8 (d, C-1″), 68.5 (d, C-2″), 70.8 (d, C-3″), 72.6 (d, C-4″), 70.0 (d, C-5″), 16.53 (q, C-6″), and 51.43 (q, OCH3) (NMR spectrogram SI 15–SI 16 in Supplementary Material).

Claulancoumside (6): +24.3 (MeOH; c 1.1), UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε): 325 (4.18), 256 (3.53), 223(4.18) nm; IR (KBr, νmax, cm−1): 3341, 2903, 2834, 1702, 1618, 1527, 1471; NMR data (SI 17–SI 21 in Supplementary Material) found in Table 2; positive ESIMS m/z: 463 [M + Na]+.

1′-O-β-d-Glucopyranosyl (2S,3R)-3-hydroxyarmesin (7): ESIMS m/z: 447 [M + Na]+; 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ: 7.79 (1H, d, J = 9.6 Hz, H-4), 7.45 (1H, s, H-5), 6.70 (1H, s, H-8), 6.03 (1H, d, J = 9.6 Hz, H-3), 5.02 (1H, d, J = 6.2 Hz, H-3′), 4.31 (1H, d, J = 6.2 Hz, H-2′), 4.31 (1H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, H-1‴), 3.14 (2H, m, H-6‴), 2.94 (1H, d, J = 6.2 Hz, H-3‴), 2.83 (1H, br s, H-5‴), 2.82 (1H, m, H-4‴), 2.66 (1H, m, H-1‴), 1.23 (3H, s, H-3″), and 1.22 (3H, s, H-2″); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ: 160.9 (s, C-2), 112.2 (d, C-3), 145.4 (d, C-4), 113.3 (s, C-4a), 126.1 (d, C-5), 129.1 (s, C-6), 162.8 (s, C-7), 98.2 (d, C-8), 156.5 (s, C-8a), 92.3 (d, C-2′), 70.6 (d, C-3′), 78.0 (s, C-1″), 25.1 (q, C-2″), 23.3 (q, C-3″), 97.8 (d, C-1‴), 73.9 (d, C-2‴), 77.4 (d, C-3‴), 70.3(d, C-4‴), 77.1 (d, C-5‴), and 61.3 (t, C-6‴) (NMR spectrogram SI 22–SI 26 in Supplementary Material).

Clausesquiside A (8): −113.4° (MeOH; c 0.68); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε): 237 (3.21); CD (c 0.0042, MeOH) Δε (λ nm): −15.6 (241) and +0.8 (322) nm; IR (KBr, νmax, cm−1): 3447, 2981, 1668, 1105, 1043, 961; NMR data (SI 27–SI 28 in Supplementary Material) found in Table 3; positive ESIMS m/z: 425 [M + Na]+, HRESIMS m/z: 425.1933 (Calculated for: [C19H30O9 + Na]+, 425.1928).

Clausesquiside B (9): −101.3° (MeOH; c 0.71); CD (c 0.0036, MeOH) Δε (λ nm): −7.1 (321), +186.2 (254) nm; IR (KBr, νmax, cm−1): 3439, 2979, 1675, 1100; NMR data (SI 29–SI 33 in Supplementary Material) found in Table 3; positive ESIMS m/z: 409 [M + Na]+.

(6R,9R,4Z,7E)-9,10-Dihydroxy-4,7-megastigmadien-3-one-9-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (10): : −63.13 (c 0.82, MeOH); ESIMS m/z: 393 [M + Na]+; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, MeOD): δ 5.85 (1H, br s, H-4), 5.83 (1H, dd, J = 15.4, 9.4 Hz, H-7), 5.66 (1H, dd, J = 15.4, 7.4 Hz, H-8), 4.43 (1H, m, H-9), 4.31 (1H, d, J = 7.1 Hz, H-1′), 3.90 (1H, dd, 12.0, 2.1 Hz, H-6′a), 3.63 (1H, dd, J = 11.0, 3.9 Hz, H-10a), 3.57 (1H, dd, J = 11.0, 3.9 Hz, H-10b), 3.54 (1H, m, H-6′b), 3.30–3.13 (4H, m, H-2′, 3′, 4′ and 5′), 2.71 (1H, d, J = 9.4 Hz, H-6), 2.43 and 2.00 (1H each, d, J = 16.6 Hz, H-2), 1.95 (3H, s, H-13), 1.01 (3H, s, H-12), and 0.97 (3H, s, H-11); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD): δ 35.7 (s, C-1), 48.3 (t, C-2), 200.6 (s, C-3), 124.9 (d, C-4), 164.1 (s, C-5), 55.6 (d, C-6), 128.9 (d, C-7), 134.1 (d, C-8), 78.3 (d, C-9), 7 (t, C-10), 26.7 (q, C-11), 26.2 (q, C-12), 22.4 (q, C-13), 99.7 (d, C-1′), 3.4 (d, C-2′), 76.7 (d, C-3′), 770.3 (d, C-4′),76.7 (d, C-5′), and 61.4 (d, C-6′) (NMR spectrogram SI 34–SI 35 in Supplementary Material).

(6R,9S)-Roseoside (11): : −75.6 (c 1.00, MeOH); ESIMS m/z: 409 [M + Na]+; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, MeOD): δ: 5.90 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-7), 5.78 (1H, br s, H-4), 5.64 (1H, dd, J = 15.6, 7.1 Hz, H-8), 4.44 (1H, m, H-9), 4.18 (1H, d, J = 7.5 Hz, H-1′), 3.78 (1H, dd, J = 10.5, 2.2 Hz, H- H-6′a), 3.63 (1H, dd, J = 10.5, 2.2 Hz, H-6′b), 3.21–3.17 (3H, m, H-2′, 3′ and 4′), 3.11 (1H, m, H-5′), 2.55 (1H, d, J = 16.7 Hz, H-2a), 2.16 (1H, d, J = 16.7 Hz, H-2b), 1.84 (3H, s, H-13), 1.19 (3H, d, J = 6.4 Hz, H-10), 0.94 (3H, s, H-11), and 0.92 (3H, s, H-12); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ: 41.1 (s, C-1), 49.4 (t, C-2), 200.0 (s, C-3), 125.8 (d, C-4), 165.9 (s, C-5) 78.7 (s, C-6), 132.3 (d, C-7), 132.4 (d, C-8), 73.5 (d, C-9), 23.4 (q, C-10), 20.9 (q, C-11), 22.2 (q, C-12), 18.3 (q, C-13), 99.9 (d, C-1′), 73.3 (d, C-2′), 76.9 (d, C-3′), 70.1 (d, C-4′), 76.8 (d, C-5′), and 61.4 (t, C-6′) (NMR spectrogram SI 36–SI 37 in Supplementary Material).

Adenosine (12): ESIMS m/z: 304 [M + Na]+; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, MeOD): δ 8.07 (1H, s, H-8), 7.90 (1H, s, H-2), 7.13 (2H, br s, 6-NH2), 5.64 (1H, d, J = 6.1 Hz, H-1′), 4.38 (1H, m, H-2′), 3.90 (1H, m, H-3′), 3.73 (1H, m, H-4′), 3.41 (1H, m, H-5′a), and 3.35 (1H, m, H-5′b); 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 153.0 (d, C-2), 149.6 (s, C-4), 119.9 (s, C-5), 156.7 (s, C-6), 140.5 (d, C-8), 88.5 (d, C-1′), 74.1 (d, C-2′), 71.2 (d, C-3′), 86.5 (d, C-4′), and 62.2 (t, C-5′) (NMR spectrogram SI 38–SI 42 in Supplementary Material).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations and UV spectra were measured using a Horiba SEPA-300 polarimeter (Horiba, Tokyo, Japan) and shimadzu UV-2401 A spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan), respectively. IR spectra were recorded with a Tensor 27 Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) spectrometer with KBr pellets (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Mass Spectrometry (MS) were recorded on an API QSTAR Pular-1 mass spectrometer (VG, Manchester, UK). High Resolution Electrospray Ionization mass Spectroscopy (HRESIMS) were obtained with a Bruker Daltonics, Inc. micro-TOF-Q spectrometer. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra were acquired with a Bruker AV-400 (1H: 400 MHz, 13C: 101 MHz) spectrometer in CD3OD with tetramethylsilane as the internal standard at room temperature (Bruker, Bremerhaven, Germany). Semipreparative reversed-phase High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) was performed on an Agilent 1260 apparatus equipped with a UV detector and an Agilent Eclipse (XDB-C18, 5μm, 9.4 × 250 mm) column at a flow rate of 2 mL/min (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Column chromatography (CC) was performed on silica gel (100–200 mesh, 200–300 mesh) and TLC was carried out on precoated silica gel GF254 glass plates (Qingdao Marine Chemical, Inc., Qingdao, China). Column chromatography (CC) was performed on sephadex LH-20 (Pharmacia, New Jersey, NJ, USA).

3.2. Plant Material

The stems and leaves of C. lansium (three-year-old) were collected by pruning and air-dried in Qingyuan (Latitude N 23°70′; Longitude E 113°03′; altitude 71 m), Guangdong Province, China, in September 2015, which were identified by Professor Zhang Zhi-Yong (a botanist) of College of Agriculture, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang, China. A voucher specimen (no. 2015912) has been deposited in College of Agriculture, Jiangxi Agricultural University.

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

The air dried and powdered stems and leaves of C. lansium (11 Kg) were extracted by refluxing 95% methanol (20 L each) three times. This process yielded methanol-soluble extracts, which were suspended in water and subsequently extracted with PE, EtOAc, and n-BuOH (3 × 5 L, each), respectively. The n-BuOH part (130 g) was subjected to a reversed-phase column (RP-18) eluting with MeOH-Water (10%–100%) to four sub-fractions (A1–A4). A3 was subjected to normal phase silica gel CC (200–300 mesh) with a gradient system of CH2Cl2-MeOH (9:1-7:3, v/v) to give six fractions A3-1–A3-6. A3-2 was further separated by normal phase silica gel CC (200–300 mesh) with a isocratic system of CH2Cl2-MeOH (9:1) to give four fractions A3-2-1–A3-2-4. A3-2-2 was separated by HPLC (mobile phase: H2O: MeOH (75:25, v/v)) to give 2 (8 mg), 4 (6 mg), and 5 (9 mg). In the same way, A3-2-3 was separated by HPLC [H2O: MeOH (80:20, v/v)] to give 1 (6 mg) and 3 (11 mg). Similarly, A3-2-4 gave 6 (4 mg) and 7 (10 mg). A3-3 was separated by repeated CC (200–300 mesh) with an isocratic mixture of CH2Cl2-MeOH (9:1, v/v) to produce five fractions A3-3-1–A3-3-5. After HPLC separation, A3-3-2 gave 8 (6 mg) and 10 (9 mg), A3-3-3 gave 9 (5 mg), and A3-3-4 produced 11 (8 mg) and 12 (13 mg) [35,36,48].

3.4. Determination of Absolute Configurations of Sugars

Compounds 1,6,8,9 (each compound 2–3 mg) were dissolved in 1 N HCl (4 mL) and heated at 90 °C under condition of reflux for 6 h. The reaction product was dissolved in H2O after evaporation and partitioned with CH2Cl2. The aqueous layer containing sugars was concentrated, and then was mixed with L-cysteine methyl ester hydrochloride. Anhydrous pyridine (1 mL) was added to the mixture and heated at 60 °C for 2 h. The product was added to isothiocyanate (3 mg) and heated at 60 °C for another 2 h. The final reaction mixture was analyzed by HPLC under the following conditions: an Agilent 1260 chromatograph equipped an Eclipse XDB-C18 column (5 µm, 4.6 × 250 mm); column temperature: 35 °C; mobile phase: isocratic elution of 25% CH3CN–H2O (V:V) in 50 mmol/L HCl; flow rate: 0.8 mL/min; injection volume: 10 µL; and UV detection wavelength: 250 nm. The standard d-glucose and d-apiose were subjected under the same conditions. After the comparison of the retention times of monosaccharide derivatives, the samples were confirmed to comprise of d-glucose (19.25 min) and d-apiose (30.34 min), respectively [19,20].

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, 12 compounds were isolated from C. lansium. They were obtained from the genus Clausena for the first time, including four new glycosides. The existence of these compounds demonstrates the taxonomic significance of C. lansium in the genus Clausena and suggests that some glycosides from this plant probably play a role in the anticancer activity of C. lansium to some extent.

Acknowledgments

We have a special thanks to Zhang Zhi-Yong (a botanist of College of Agriculture, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang, China) for the collection and identification of C. lansium.

Supplementary Materials

The 1D- and 2D-NMR spectroscopic data of compounds 1–12 in the paper are available online.

Author Contributions

W.P. and B.L. designed and supervised the research. W.P. and X.F. analyzed spectroscopic data. Y.L., Z.X., and X.S. performed the experiment and W.P., X.F., Y.L., Z.X., X.S., F.Z., G.H. and B.L. wrote, reviewed, and approved the final version of manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Funds of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31660094), NSFC-Jiangxi Province (No. 20181BAB204002) and National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFD0301604).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors.

References

- 1.Editorial Committee of Flora of China, Chinese Academy of Sciences . Flora of China. Volume 43. Science Press; Beijing, China: 1997. p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arbab I.A., Abdul A.B., Aspollah M., Abdullah R., Abdelwahab S.I., Ali M.L.Z. A review of traditional uses, phytochemical and pharmacological aspects of selected members of Clausena genus (Rutaceae) J. Med. Plants Res. 2012;6:5107–5118. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y.P., Guo J.M., Liu Y.Y., Hu S., Yan G., Qiang L., Fu Y.H. Carbazole Alkaloids with Potential Neuroprotective Activities from the Fruits of Clausena lansium. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019;67:5764. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b00961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu H., Li C.J., Yang J.Z., Ning N., Si Y.K., Li L., Chen N.H., Zhao Q., Zhang D.M. Carbazole alkaloids from the stems of Clausena lansium. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:677–682. doi: 10.1021/np200919a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu H., Li F., Li C.J., Yang J.Z., Li L., Chen N.H., Zhang D.M. Bioactive furanocoumarins from stems of Clausena lansium. Phytochemistry. 2014;107:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen D.Y., Chao C.H., Chan H.H., Huang G.J., Hwang T.L., Lai C.Y., Lee K.H., Thang T.D., Wu T.S. Bioactiveconstituents of Clausena lansium and a method for discrimination ofaldose enantiomers. Phytochemistry. 2012;82:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song W.W., Zeng G.Z., Peng W.W., Chen K.X., Tan N.H. Cytotoxic amides and quinolones from Clausena lansium. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2014;97:298–305. doi: 10.1002/hlca.201300323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du Y.Q., Liu H., Li C.J., Ma J., Zhang D., Li L., Sun H., Bao X.Q., Zhang D.M. Bioactive carbazole alkaloids from the stemsof Clausena lansium. Fitoterapia. 2015;103:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen D.Y., Chan Y.Y., Hwang T.L., Juang S.H., Huang S.C., Kuo P.C., Thang T.D., Lee E.J., Damu A.G., Wu T.S. Constituents of the roots of Clausena lansium and their potential antiinflammatory activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2014;77:1215–1223. doi: 10.1021/np500088u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng H.D., Mei W.L., Wang H., Guo Z.K., Dong W.H., Wang H., Li S.P., Dai H.F. Carbazole alkaloids from the peels of Clausena lansium. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2014;16:1024–1028. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2014.930442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu X.Y., Xie H.H., Wei X.Y. Jasmonoid glucosides, sesquiterpenes and coumarins from the fruit of Clausena lansium. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2014;59:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.04.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang L., Li D., Xu Y.S., Feng Z.L., Meng F.C., Zhang Q.W., Gan L.S., Lin L.G. Clausoxamine, an alkaloid possessing a 1,3-oxazine-4-one ring from the seeds of Clausena lansium and the antiobesity effect of lansiumamide B. RSC Adv. 2017;7:46900–46905. doi: 10.1039/C7RA09793J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fan Y.J., Chen H.Q., Mei W.L., Kong F.D., Li F.X., Chen P.W., Cai C.H., Huang M.J., Dai H.F. Nematicidal amidealkaloids from the seeds of Clausena lansium. Fitoterapia. 2018;128:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2018.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan H., Xiong Z., Xie N., Liu S.Z., Zhang L.L., Xu F., Guo W.H., Feng J.T. Bioassay-guided isolation of antifungal amidesagainst sclerotinia sclerotiorum from the seeds of Clausena lansium. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018;121:352–359. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.05.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng H.D., Mei W.L., Guo Z.K., Liu S., Zuo W.J., Dong W.H., Li S.P., Dai H.F. Monoterpenoid coumarins from the peels of Clausena lansium. Planta Med. 2014;80:955–958. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1382839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng W.W., Zheng L.X., Ji C.J., Shi X.G., Xiong Z.H., Shangguan X.C. Carbazole alkaloids isolated from the branch and leaf extracts of Clausena lansium. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2018;16:509–512. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(18)30087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng W.W., Zheng L.X., Huo G.H. A new furan-coumarin from Clausena lansium. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2019;55:440–442. doi: 10.1007/s10600-019-02709-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang M.F., Li J.G., Rangarajan M., Shao Y., LaVoie E.J., Huang T.C., Ho C.T. Antioxidative phenolic compounds from Sage (Salvia officinalis) J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998;46:4869–4872. doi: 10.1021/jf980614b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka T., Nakashina T., Ueda T., Tomii K., Kouno I. Facile discrimination of aldose enantiomers by reversed-phase HPLC. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007;55:899–901. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim A., Choi J., Htwe K.M., Chin Y.W., Kim J., Yoon K.D. Flavonoid glycosides from the aerial parts of Acacia pennata in Myanmar. Phytochemistry. 2015;118:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agrawal P.K. NMR Spectroscopy in the structural elucidation of oligosaccharides and glycosides. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:3307–3330. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(92)83678-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokosuka A., Sano T., Hashimoto K., Sakgami H., Mimaki Y. Triterpene glycosides from the whole plant of anemone hupehensis var. japonica and their cytotoxic activity. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2009;57:1425–1430. doi: 10.1248/cpb.57.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kasai R., Suzuo M., Asakawa J.I., Tanaka O. Carbon-13 chemical shifts of isoprenoid-β-d-glucopyranosides and -β-d-mannopyranosides. Stereochemical influences of aglycone alcohols. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977;2:175–178. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)92581-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemmich J., Havelund S., Thastrup O. Dihydrofurocoumarin glucosides from angelica archangelica and angelica szlvestris. Phytochemistry. 1983;22:553–555. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(83)83044-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao Y.Q., Li L., Masahiko T., Kimiye B. Glucosides from pleurospermum rivulorum. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2001;36:519–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chakthong S., Weaaryee P., Puangphet P., Mahabusarakam W., Patimaporn P., Voravuthikunchai S.P., Kanjana-Opas A. Alkaloid and coumarins from the green fruits of Aegle marmelos. Phytochemistry. 2012;75:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamano Y., Ito M. Synthesis of optically active vomifoliol and roseoside stereoisomers. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005;53:541–546. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pabst A., Barron D., Sbmons E., Schreier P. Two diastereomeric 3-OXO-α-ionol β-d-glucosides from raspberry fruit. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:1649–1652. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(92)83121-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saleem M., Kim H.J., Han C.K., Jin C., Lee Y.S. Secondary metabolites from Opuntia ficus-indica var. saboten. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:1390–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kil H.W., Rho T., Yoon K.D. Phytochemical study of aerial parts of Leea asiatica. Molecules. 2019;24:1733. doi: 10.3390/molecules24091733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Da Y., Satoh Y., Ohtwka M., Nagasao M., Shoji J. Phenolic constituents of phellodezvdron amurense Bark. Phyrochmisrry. 1994;35:209–215. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chassagne D., Crouzet J., Bayonove C.L., Baumes R.L. Glycosidically bound eugenol and methyl salicylate in the fruit of edible Passiflora species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997;45:2685–2689. doi: 10.1021/jf9608480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greger H., Pacher T., Brem B., Bacher M., Hofer O. Insecticidal flavaglines and other compounds from Fijian Aglaia species. Phytochemistry. 2001;57:57–64. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00471-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breimaier E., Voelter W. Konfigurations-und konformations-untersuchungen von adenosinanalogen mit 13C-resonanz. Tetrahedron. 1973;29:227–232. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)99400-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng W.W., Song W.W., Huang M.B., Zeng G.Z., Tan N.H. Twelve benzene derivatives from Clausena excavate. Acta Pharm. Sin. 2014;49:1689–1693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peng W.W., Song W.W., Huang M.B., Tan N.H. Monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes from Clausena excavata. Chin. J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2014;39:1620–1624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alkhatib R., Hennebelle T., Roumy V., Sahpaz S., Suzge S., Akalın E., Meriçl A.H., Bailleul F. Coumarins, caffeoyl derivatives and a monoterpenoid glycoside from Ferulago asparagifolia. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2009;37:230–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bse.2009.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu K., Jiangb S., Sunc H., Zhou Y., Xub X., Penga S., Dinga L. New alkaloids from the seeds of Notopterygium incisum. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012;26:1898–1903. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2011.628177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ishikawa T., Sega Y., Kitajima J. Water-Soluble Constituents of Glehnia littoralis Fruit. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2001;49:584–588. doi: 10.1248/cpb.49.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.He R.J., Zhang Y.J., Wu L.D., Nie H., Huang Y., Liu B.M., Deng S.P., Yang R.Y., Huang S., Nong Z.J., et al. Benzofuran glycosides and coumarins from the bark of Streblus indicus (Bur.) Corner. Phytochemistry. 2017;138:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2017.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uchiyama T., Hara S., Makino M., Fujimoto Y. seco-Adianane-type triterpenoids from Dorstenia brasiliensis (Moraceae) Phytochemistry. 2002;60:761–764. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peng W.W., Song W.W., Liu X.Y., Tan N.H. Reseach progress on carbazole alkaloids from plants of Clausena Burmf. Chin. Tradi. Herbal Drugs. 2017;48:2761. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peng W.W., Song W.W., Tan N.H. Reseach progress on from Clausena and their pharmacological activities. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2017;29:1428. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ito C., Itoigawa M., Katsuno S., Omura M., Tokuda H., Nishino H., Furukawa H. Chemical constituents of Clausena excavata: Isolation and structure elucidation of novel furanone-coumarins with inhibitory effects for tumor-promotion. J. Nat. Prod. 2000;63:1218–1224. doi: 10.1021/np990619i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaichantipyuth C., Pummangera S., Naowsaran K., Thanyavuthi D., Anderson J., McLaughlin J.L. Two new bioactive carbazole alkaloids from Clausena harmandiana. J. Nat. Prod. 1988;51:1285–1288. doi: 10.1021/np50060a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu T.S., Huang S.C., Wu P.L., Lee K.D. Structure and synthesis of clausenaquinone A. A novel carbazolequinone alkaloid and bioactive principle from Clausena excavata. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1994;4:2395–2398. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(01)80397-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng Z.J., Zhangb X.H., Zhanga J.P., Shanga X.H., Gao Y., Lu X.L., Liu X.Y., Jiao B.H. A new aromatic glycoside from Glehnia littoralis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014;28:551–554. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2014.886206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He D.H., Slebodnick C., Rakotondraibe L.H. Bioactive drimane sesquiterpenoids and aromatic glycosides from Cinnamosma fragrans. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017;27:1754–1759. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu Y., Guan W., Lu Z.K., Guo R., Xia Y.G., Lv S.W., Yang B.Y., Kuang H.X. New sesquiterpenoids from the stems of Datura metel L. Fitoterapia. 2019;134:417–421. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2019.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.