Abstract

This cross-sectional survey study assesses knowledge of human papillomavirus by age and sex.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage (48.6% in 2017) in the United States remains far below the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80%, and a 10% difference in coverage between boys (44.3%) and girls (53.1%) has been reported.1 Knowledge of HPV among vaccine-eligible individuals and their parents is critical to vaccine uptake. Furthermore, the recommendation to receive an HPV vaccine from health care professionals can help parents in their decision-making to vaccinate children.2 Therefore, we evaluated the national-level estimates of (1) HPV knowledge and (2) receipt of HPV vaccine recommendation from a health care professional.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of the Health Information National Trend Survey (HINTS-5) data, cycles 1 (conducted between January and May 2017) and 2 (conducted between January and May 2018). Analysis was conducted from December 1, 2018, to February 29, 2019. HINTS is a nationally representative survey administered by the National Cancer Institute that collects data on health-related behaviors and knowledge among US adults.3 We evaluated questions regarding (1) knowledge of HPV, HPV vaccine, and the relationship between HPV and cervical, oral, anal, and penile cancers and (2) receipt of HPV vaccine recommendation from a health care professional among vaccine-eligible persons and those with vaccine-eligible family members. Given the current vaccination age eligibility criteria and the recent approval of the HPV vaccination for adults aged 27 to 45 years,4 the outcomes were estimated for 3 age groups: (1) age 18 to 26 years (vaccine-eligible), (2) age 27 to 45 years (vaccine-approved), and (3) 46 years and older (not eligible/approved). This study was deemed exempt from review by the institutional review board of the University of Texas Health Science Center because it uses publicly available deidentified data.

Descriptive statistics were computed to describe HPV knowledge and receipt of an HPV vaccine recommendation. A survey-design adjusted Wald F test was used for bivariate analyses. All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and were adjusted for sample weights and the complex survey design. Statistical significance was assessed at 2-sided P < .05.

Results

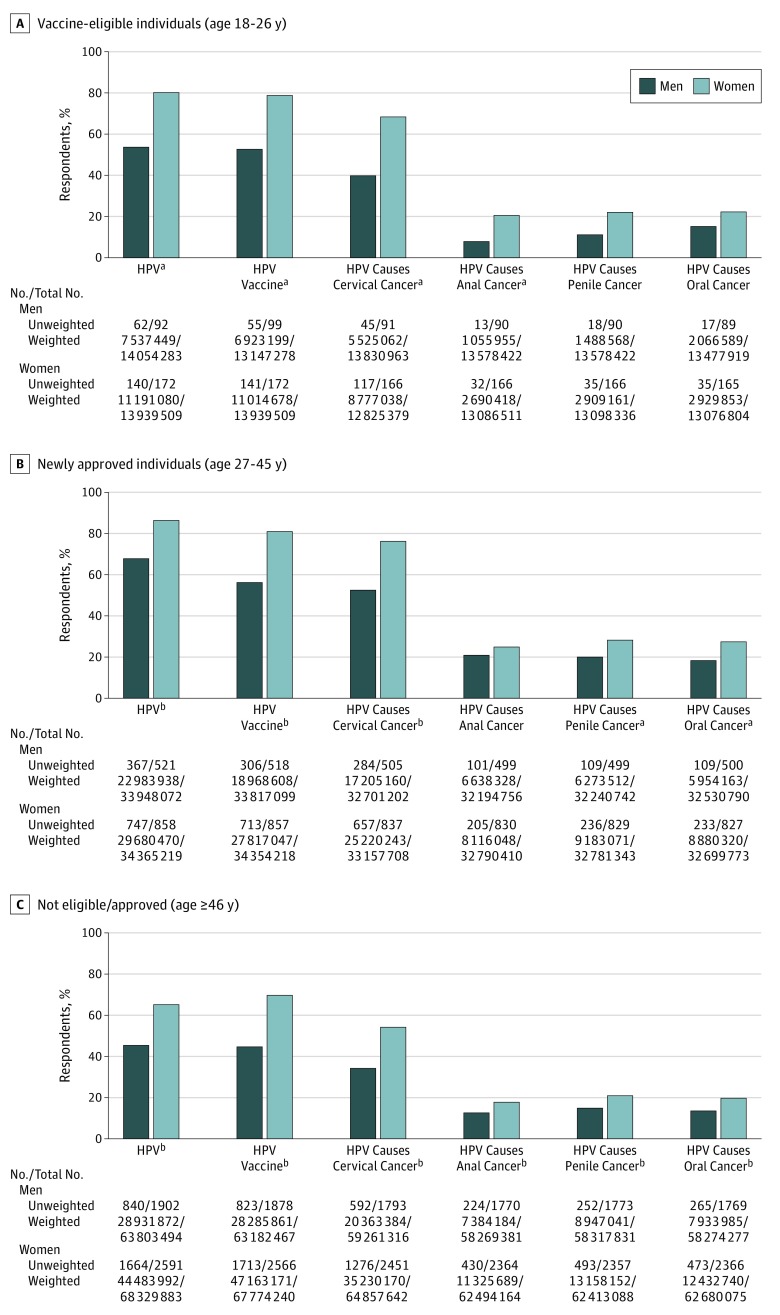

A total of 2564 men and 3697 women responded to HPV knowledge questions in HINTS-5. Fewer men aged 18 to 26 years (vaccine-eligible) were knowledgeable about HPV (men: 53.6% [95% CI, 36.2%-71.0%] vs women: 80.3% [95% CI, 71.5%-89.1%]; P < .05) and the HPV vaccine (men: 52.7% [95% CI, 36.9%-68.4%] vs women: 79.0% [95% CI, 70.3%-87.8%]; P < .05) than women (Figure 1A). Overall, 60.1% (95% CI, 43.0%-77.2%) of men and 31.6% (95% CI, 21.4%-41.7%) of women in this age category did not know that HPV causes cervical cancer. In addition, 92.2% (95% CI, 87.1%-97.3%), 89.0% (95% CI, 82.7%-95.4%), and 84.7% (95% CI, 74.1%-95.2%) of men and 79.4% (95% CI, 68.6%-90.3%), 77.8% (95% CI, 66.5%-89.1%), and 77.6% (95% CI, 66.8%-88.4%) of women did not know that HPV causes anal, penile, or oral cancers, respectively.

Figure 1. Knowledge of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection, HPV Vaccination, and the Relationship Between HPV and Cancer.

Participants responded yes to: “Have you ever heard of HPV?”; “Before today, have you ever heard of the cervical cancer vaccine or HPV shot?”; and “Do you think HPV can cause cervical/oral/anal/penile cancer?”

aP < .05.

bP < .001.

Among individuals aged 27 to 45 years, HPV and HPV vaccination knowledge was lower among men than women (Figure 1B): HPV (67.7% [95% CI, 62.3%-73.1%] vs 86.4% [95% CI, 82.7%-90.0%]; P < .001), HPV vaccination (56.1% [95% CI, 50.2%-62.0%] vs 81.0% [95% CI, 76.4%-85.5%]; P < .001). Over half of men and women did not know that HPV causes anal, penile, and oral cancers. The proportion of men vs women who were not knowledgeable about the relationship between HPV and cancers is as follows: cervical (47.4% [95% CI, 41.3%-53.5%] vs 23.9% [95% CI, 19.4%-28.5%]; P < .001), anal (79.4% [95% CI, 73.3-85.4] vs 75.2% [95% CI, 70.9%-79.6%]; P = 0.31), penile (80.5% [95% CI, 75.6%-85.4%] vs 72.0% [95% CI, 67.2-76.7]; P < .05), and oral (81.7% [95% CI, 77.3%-86.1%] vs 72.8% [95% CI, 68.5%-77.2%]; P < .05).

A similar level of knowledge and significant sex differences were observed among individuals 46 years and older (Figure 1C). Notably, an overwhelming number of individuals in this age group were not knowledgeable about HPV and HPV vaccine. The proportion of men vs women not knowledgeable were: HPV (54.7% [95% CI, 51.2%-58.1%] vs 34.9% [95% CI, 32.3%-37.5%]; P < .001), HPV vaccine (55.2% [95% CI, 51.3%-59.1%] vs 30.4% [95% CI, 27.9%-32.9%]; P < .001), HPV and cervical cancer (65.6% [95% CI, 62.1%-69.2%] vs 45.7% [95% CI, 43.2%-48.1%]; P < .001), HPV and anal cancer (87.3% [95% CI, 84.9%-89.7%] vs 81.9% [95% CI, 79.6%-84.2%]; P < .001), HPV and penile cancer (84.7% [95% CI, 81.8%-87.5%] vs 78.9% [95% CI, 76.6%-81.3%]; P < .001), and HPV and oral cancer (86.4% [95% CI, 83.8%-88.9%] vs 80.2% [95% CI, 77.8%-82.5%]; P < .001).

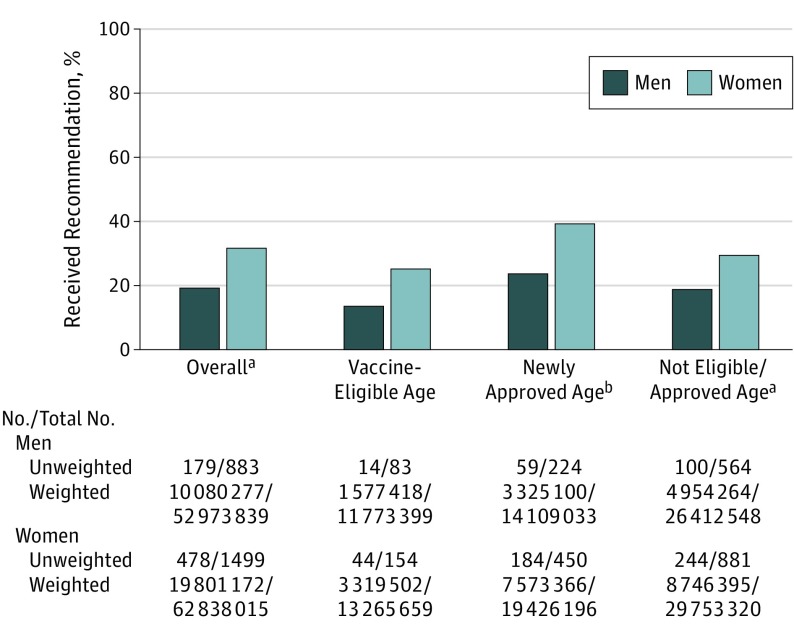

Results for receipt of HPV vaccine recommendations from a health care professional in the subgroup of vaccine-eligible persons or those with vaccine-eligible family members are presented in Figure 2. Overall, fewer men (19% [95% CI, 15.2%-22.8%]) than women (31.5% [95% CI, 28.1%-34.9%]) received an HPV vaccine recommendation (P < .001).

Figure 2. Receipt of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Recommendation From Health Care Professional to Vaccine-Eligible Persons or Those With Vaccine-Eligible Family Members.

Participants responded yes to: “In the last 12 months, has a doctor or health care professional recommended that you or someone in your immediate family get an HPV shot or vaccine?”

aP < .001.

bP < .05.

Discussion

Findings from this national survey revealed that men are less knowledgeable than women about HPV, HPV vaccination, and the relationship between HPV and cancer. Low HPV knowledge in men may be attributed to the message framing of HPV vaccination campaigns that historically have focused on cervical cancer prevention in women.5 Notably, more than 70% of US adults irrespective of their age and sex did not know that HPV causes oral, anal, and penile cancers.

In particular, the lack of HPV knowledge among adults aged 27 to 45 years and 46 years and older is concerning given that adults in these age groups are (or will likely be) the parents responsible for making HPV vaccination decisions for their children. Effective communication between patients and clinicians regarding the importance of HPV vaccination for cancer prevention is crucial to address this issue. A limitation of our study is that the data are self-reported and may be prone to recall bias. In summary, educational campaigns that target both sexes and convey the benefits of HPV vaccination for cancer prevention are urgently needed to accelerate HPV vaccine initiation and completion in the United States.

References

- 1.Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. . National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years: United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):909-917. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6733a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(1):76-82. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finney Rutten LJ, Davis T, Beckjord EB, Blake K, Moser RP, Hesse BW. Picking up the pace: changes in method and frame for the health information national trends survey (2011-2014). J Health Commun. 2012;17(8):979-989. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.700998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.FDA approves expanded use of Gardasil 9 to include individuals 27 through 45 years old [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food & Drug Administration; October 5. 2018. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-expanded-use-gardasil-9-include-individuals-27-through-45-years-old?utm_campaign=10052018_PR_FDA+approves+expanded+use+of+Gardasil+9+to+include+individuals+27+through+45+years+old. Accessed August 7, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daley EM, Vamos CA, Thompson EL, et al. . The feminization of HPV: how science, politics, economics and gender norms shaped U.S. HPV vaccine implementation. Papillomavirus Res. 2017;3:142-148. doi: 10.1016/j.pvr.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]