Key Points

Question

Does combining perioperative behavioral and pelvic floor muscle therapy with midurethral sling result in greater improvement in mixed urinary incontinence symptoms than does a sling alone?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 480 women, incontinence symptoms (measured by the Urogenital Distress Inventory Long Form; range, 0-300 points; minimal clinically important difference, 35 points) decreased by 128.2 points in the combined therapy group and 114.7 points in the surgery alone group, resulting in a statistically significant between-group difference that did not meet the threshold for clinical importance.

Meaning

Among women with mixed urinary incontinence, the addition of perioperative behavioral and pelvic floor muscle therapy to midurethral sling surgery resulted in a difference in urinary incontinence symptoms that may not be clinically important.

Abstract

Importance

Mixed urinary incontinence, including both stress and urgency incontinence, has adverse effects on a woman’s quality of life. Studies evaluating treatments to simultaneously improve both components are lacking.

Objective

To determine whether combining behavioral and pelvic floor muscle therapy with midurethral sling is more effective than sling alone for improving mixed urinary incontinence symptoms.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized clinical trial involving women 21 years or older with moderate or severe stress and urgency urinary incontinence symptoms for at least 3 months, and at least 1 stress and 1 urgency incontinence episode on a 3-day bladder diary. The trial was conducted across 9 sites in the United States, enrollment between October 2013 and April 2016; final follow-up October 2017.

Interventions

Behavioral and pelvic floor muscle therapy (included 1 preoperative and 5 postoperative sessions through 6 months) combined with midurethral sling (n = 209) vs sling alone (n = 207).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was change between baseline and 12 months in mixed incontinence symptoms measured by the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) long form; range, 0 to 300 points; minimal clinically important difference, 35 points, with higher scores indicating worse symptoms.

Results

Among 480 women randomized (mean [SD] age, 54.0 years [10.7]), 464 were eligible and 416 (86.7%) had postbaseline outcome data and were included in primary analyses. The UDI score in the combined group significantly decreased from 178.0 points at baseline to 30.7 points at 12 months, adjusted mean change −128.1 points (95% CI, −146.5 to −109.8). The UDI score in the sling-only group significantly decreased from 176.8 to 34.5 points, adjusted mean change −114.7 points (95% CI, −133.3 to −96.2). The model-estimated between-group difference (−13.4 points; 95% CI, −25.9 to −1.0; P = .04) did not meet the minimal clinically important difference threshold. Related and unrelated serious adverse events occurred in 10.2% of the participants (8.7% combined and 11.8% sling only).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among women with mixed urinary incontinence, behavioral and pelvic floor muscle therapy combined with midurethral sling surgery compared with surgery alone resulted in a small statistically significant difference in urinary incontinence symptoms at 12 months that did not meet the prespecified threshold for clinical importance.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01959347

This superiority trial compared behavioral and pelvic floor muscle therapy plus midurethral sling surgery with midurethral sling surgery alone in treating women with mixed urinary incontinence.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence is common, affecting up to 58% of women and has a negative effect on quality of life.1 Up to half of women with urinary incontinence have mixed urinary incontinence, which includes both stress and urgency urinary incontinence, termed mixed urinary incontinence. Mixed incontinence is often considered more severe because it is more challenging to manage than either urinary condition alone and responds poorly to treatment.2,3,4 Treatment guidelines are largely based on the logic that women with mixed incontinence are eligible for treatments used for either stress or urgency incontinence. First-line treatment can include behavioral and pelvic floor muscle training, followed by overactive bladder medication.5,6,7,8 A combination of conservative approaches can also be used, but many women eventually undergo surgery.

Guidelines and recommendations for mixed urinary incontinence treatment caution that surgery could worsen the urgency component.5,6,8 Observational data supporting that midurethral sling surgery remains effective for treating the stress component exists.9 However, limited studies have evaluated approaches to improve urgency incontinence outcomes after midurethral sling among women with mixed incontinence.

One strategy used successfully for other conditions that has the potential to treat stress and urgency incontinence concurrently includes combining conservative therapy with surgery,10,11,12 but the efficacy among women with mixed incontinence remains unclear. The Effects of Surgical Treatment Enhanced With Exercise for Mixed Urinary Incontinence (ESTEEM) trial was conducted to test whether perioperative behavioral and pelvic floor muscle therapy combined with midurethral sling surgery would improve symptoms at 12 months compared with sling alone.

Methods

Study Design and Oversight

This was a multicenter, randomized, superiority trial. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of 9 clinical recruiting sites in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. All participants provided written informed consent. Interval review of safety was conducted by an independent data and safety monitoring board. Study methods have previously been published,13 and the study protocol appears in Supplement 1. The final statistical analysis plan appears in Supplement 2.

Patients

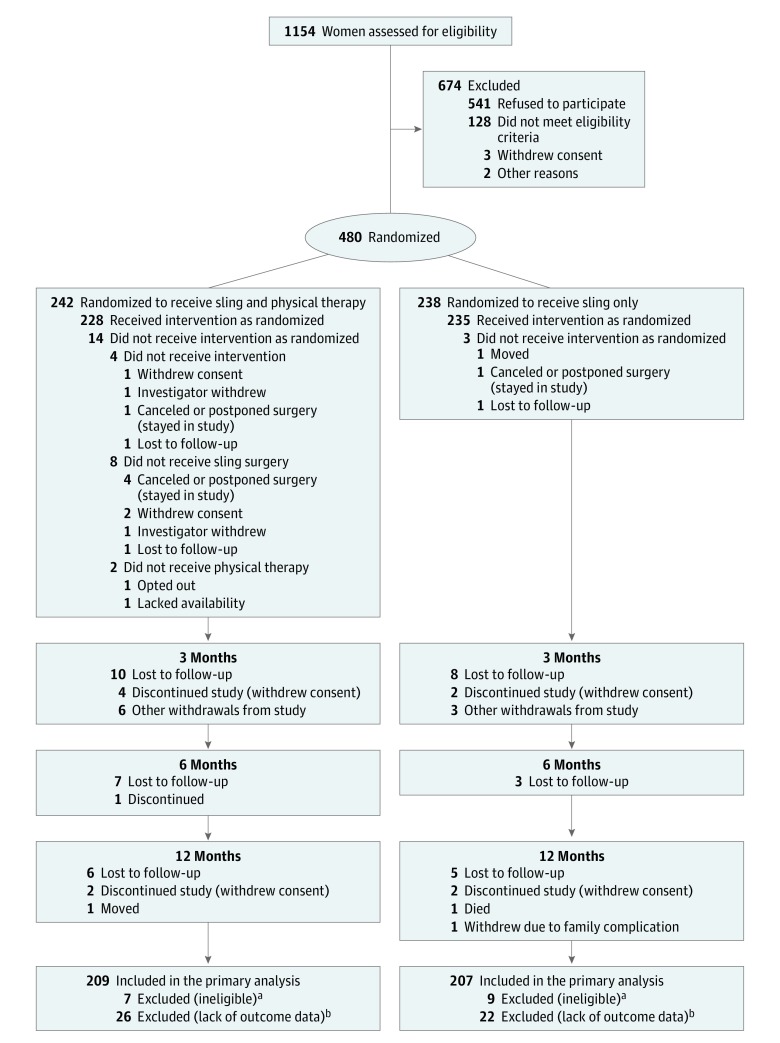

Eligibility was designed to include patients with a wide range of clinically bothersome mixed urinary incontinence symptoms (Figure 1). Women 21 years or older, reporting moderately to severely bothersome stress and urgency incontinence symptoms for at least 3 months and documenting at least 1 stress and 1 urgency incontinence episode on a 3-day bladder diary were eligible. These criteria provided both subjective and objective documentation. Exclusion criteria included anterior or apical prolapse at or beyond the hymen, planned concomitant surgery for anterior or apical prolapse, prior sling, or current overactive bladder medication use (patients were eligible after a 3-week washout of overactive bladder medication). We collected race/ethnicity data to help describe the study population, based on patient self-identification and categorized by National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Figure 1. Screening, Randomization, Treatment, and Follow-up of Women Participating in the Effects of Surgical Treatment Enhanced With Exercise for Mixed Urinary Incontinence (ESTEEM) Trial.

aIneligible participants are included in the adverse event analysis population. Randomized patients were determined to be ineligible during site audits based on invalid baseline bladder diaries, improper washouts from over active bladder medication, or Urogenital Distress Inventory scores.

bParticipants without outcome data were included in the dichotomous re-treatment analysis and were conservatively assumed to have not been retreated.

Interventions and Randomization

Both retropubic and transobturator midurethral sling techniques were allowed because previous trials support equivalent outcomes.14,15,16,17 The combined treatment included the addition of 1 preoperative and 5 postoperative visits through 6 months, was conducted by centrally trained interventionists, and included (1) education on pelvic floor anatomy, bladder function, and voiding habits; (2) pelvic floor muscle training; (3) bladder training; and (4) strategies to control stress and urgency symptoms. Details of the trial intervention have been published.18 Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 within the electronic data management system using a randomly permuted block design (randomly ordered blocks of 2 and 4), stratified by clinical site and urgency severity. Surgeons and outcome assessors were masked. Patients and interventionists were not masked.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

All outcomes reported herein (primary, secondary, and exploratory) were prespecified. The study was powered for primary and secondary outcomes. The primary outcome was change in symptoms at 12 months, measured using the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) long from total score (range, 0-300 points; minimal clinically important difference [MCID], 35; SD, 50.4).19 The UDI is a validated patient-reported outcome questionnaire that includes 3 symptom subscales: irritative symptoms (urgency incontinence, frequency, nocturia, and urgency); stress incontinence; and obstructive symptoms. Each subscale ranges from 0 to 100 points, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity.20 Secondary outcomes included change in UDI-stress (MCID, 8 points; SD, 21.5)21 and UDI-irritative (MCID, 15 points; SD, 25.6)19 subscale scores between groups at 12 months.

Other Prespecified (Exploratory) Outcomes

Other outcomes included 3-day bladder diary measures: total number of incontinence episodes, number of urgency and stress incontinence episodes, number of voids, and number of pads used per day. Women reporting on average more than 8 voids over 24 hours were considered to have high voiding frequency. Normalization of voiding frequency was defined as improving from high voiding frequency to 8 or fewer voids over 24 hours. Incontinence–specific quality of life was measured using the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire20,21 (IIQ), a score range from 0 to 400 points (MCID, 16 points). Higher scores indicate worse quality of life. Patients completed the Patient Global Impression of Improvement22 (PGI-I score range response from 1, very much better to 7, very much worse), which was dichotomized into 2 categories for analysis as responses 1 or 2 (much better and very much better) compared with all other categories. The PGI of Severity22 (PGI-S range response, 1 normal to 4 severe) was dichotomized into 2 categories as responses 1 or 2 (normal or mild) compared with all other categories. Overactive bladder–specific questionnaires included the Overactive Bladder Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire23 (OAB-q-SS responses are presented on 4-, 5-, and 6-point Likert scales; range, 0-100 points; higher scores indicate greater satisfaction) and the Symptom and Health-Related Quality of Life (OAB-q-HRQL) questionnaires24 (range, 0-100 points; MCID, 10 points for both25). Higher scores on the symptoms questionnaire indicate increased severity; higher scores on the HRQL questionnaire indicate better quality of life. Additional lower urinary tract symptom treatments, clinically important complications, and adverse events were collected. All questionnaires were administered at 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery and prior to initiating any off-protocol urinary treatment. Participants completed questionnaires on paper.

Statistical Analysis

Using simulated data accounting for the possibility of additional urinary treatments (estimated to be 30% after sling only in women with mixed urinary incontinence26), sample sizes were estimated to detect published MCIDs for the UDI total score, UDI-irritative, and UDI-stress subscale scores to allow assessment of urgency and stress symptom outcomes separately.13 Assuming a 2-sided α of .05, 75 women per group provided 90% power to detect a mean between-group difference of 35 points (SD, 50.4)19 in change from baseline in UDI total scores at 12 months (primary outcome). For the UDI-irritative subscale (MCID, 15 points; SD, 25.6),19 and UDI-stress subscale (MCID, 8 points; SD, 21.5),21 92 and 200 women per group, respectively, were needed for 90% power with a 2-sided α of .05 (secondary outcomes). After adjusting 200 per group for 15% dropout, 472 was the target sample size. These published MCIDs were based on predominantly stress or predominantly urgency urinary incontinence populations and not a mixed incontinence population; therefore, an exploratory analysis was planned to estimate the MCIDs in the current study population and compare these estimates with observed between-group differences (eMethods Supplement 3).

Baseline characteristics were compared between groups using t tests for continuous variables, and χ2 for categorical variables. The primary analysis population included eligible, randomized participants with outcome data at 1 time point or more. A general linear mixed-model estimated change from baseline in UDI total score at 3, 6, and 12 months. Treatment group, time as a linear effect, site, urgency severity, additional treatment for urinary symptoms, and interactions between treatment group, time, and additional treatment were included as fixed effects. Correlation between repeated measures on the same participant was modeled using a compound symmetry covariance structure with different estimates for participants with and without additional treatment. Because any additional urinary treatment after surgery was expected to improve outcomes, the protocol specified that outcomes after additional treatment would be treated as missing, and the randomized treatment effect was estimated as a weighted average that accounted for the percent of women in each group who underwent additional treatment. Treatment groups were compared at 12 months using a 2-sided test at an α level of .05. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using multiple imputation to estimate missing values including outcomes following additional treatment, and (post hoc) including site as a random effect.

Other outcomes were analyzed with the methods used for the primary analysis for continuous variables, or analogous generalized linear mixed models for categorical outcomes. Time to additional treatment was assessed using Kaplan-Meier curves and compared using a log-rank test. Proportionality was confirmed by examining Schoenfeld residuals. All randomized patients were included in adverse event assessment. No α adjustments were made for evaluation of multiple outcomes. Seventy-one comparisons were conducted, which could result in 3 to 4 differences with P values <.05 by chance alone. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, findings for analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Study Population

Between November 2013 and July 2017, 480 women were randomized (242 combined, 238 sling only) (Figure 1). Sixteen women discovered to be ineligible after randomization were excluded from efficacy analysis but included in adverse event analyses (7 combined, 9 sling only). The analysis population included 416 of the 464 eligible women (209 combined, 207 sling only), 402 of whom were assessed at 12 months (198 of 235 [84%] combined, 204 of 229 [89%] sling only).

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are provided in Table 1; and eTable 1 (in Supplement 3). Overall the mean daily total incontinence episodes was 5.6 (SD, 3.4); stress, 2.4 (SD, 2.0); and urgency, 2.8 (SD, 2.5).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Eligible and Randomized Patients.

| Characteristic | No./Total (%) of Women | |

|---|---|---|

| Combined Sling and Training (n = 235) | Sling Only (n = 229) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 54.3 (11.0) | 53.6 (10.4) |

| Race, No. (%) | 233 | 228 |

| White | 181 (77.7) | 181 (79.4) |

| Black/African American | 22 (9.4) | 19 (8.3) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 7 (3.0) | 3 (1.3) |

| Asian | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| >1 Race | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| Othera | 19 (8.2) | 23 (10.1) |

| Hispanic/Latina ethnicity | 49/233 (21.0) | 56/225 (24.9) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 31.7 (6.5) | 32.3 (7.1) |

| Current smoker | 32/235 (13.6) | 28/228 (12.3) |

| Stress urinary incontinence diagnosis by positive stress test | 163/235 (69.4) | 159/227 (70.0) |

| Stress urinary incontinence diagnosis by urodynamic assessment | 224/233 (96.1) | 209/229 (91.3) |

| No. of vaginal deliveries, median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) | 2.0 (2.0-3.0) |

| Total number of deliveries, median (IQR) | 2.0 (2.0-3.0) | 2.0 (2.0-3.0) |

| Menopausal status, No. (%)b | 235 | 228 |

| Premenopausal | 65 (27.7) | 76 (33.3) |

| Postmenopausal | 138 (58.7) | 124 (54.4) |

| Not sure | 32 (13.6) | 28 (12.3) |

| Previous overactive bladder medication tried | 92/234 (39.3) | 88/229 (38.4) |

| Diabetes (type 1 or 2) | 27/234 (11.5) | 33/229 (14.4) |

| Prior supervised behavioral or pelvic floor muscle training | 24/234 (10.3) | 28/229 (12.2) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; IQR, interquartile range.

Participants were able to select an “other” race category, which was accompanied by a free response field. The primary other race response was Hispanic/Latina followed by some multiple race specifications not included in the other categories.

Participants were able to select premenopausal, postmenopausal, or that they were unsure of menopausal status.

Primary Outcome

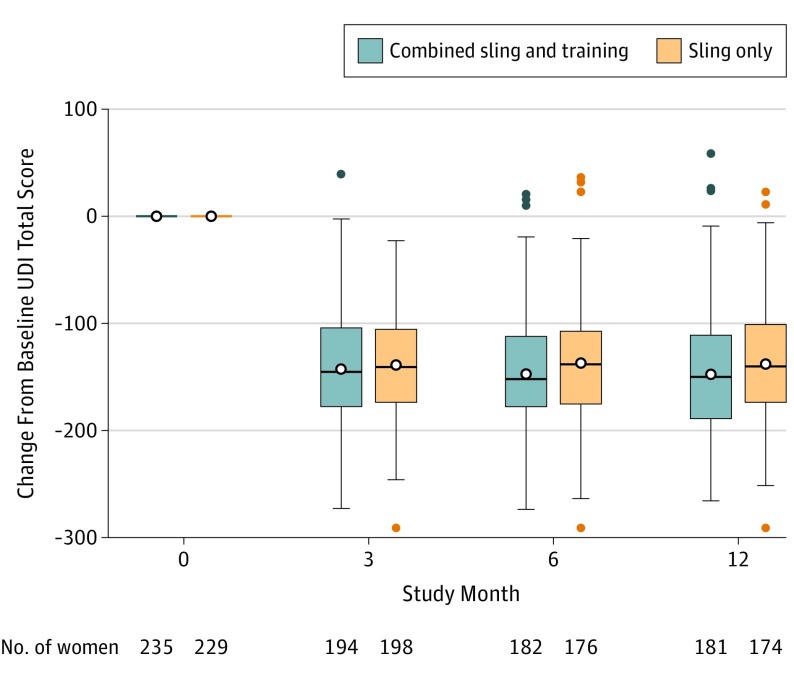

Primary and secondary outcomes appear in Table 2. For the primary outcome, the unadjusted mean UDI total scores for the combined group at baseline was 178.0 and at 12-months, 30.7 points, for an adjusted mean change of −128.1 points (95% CI, −146.5 to −109.8) vs the sling group unadjusted mean scores of 176.8 at baseline and 34.5 points at 12 months, for an adjusted mean change of −114.7 points (95% CI, −133.3 to −96.2). Compared with the sling-only group, the combined group had greater improvements in the UDI total score (Figure 2), but the model-estimated between-group difference (−13.4 points, 95% CI, −25.9 to −1.0, P = .04; Table 2) did not meet the MCID threshold. Sensitivity analyses were consistent with the primary analysis (multiple imputation results and site as random-effect results appear in eTables 2 and 3, in Supplement 3).

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Outcomes Through 12 Monthsa.

| Outcome Type | Baselineb | 3 Monthsb | 6 Monthsb | 12 Monthsb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined Sling and Training (n = 235) | Sling Only (n = 229) | Combined Sling and Training (n = 194) | Sling Only (n = 198) | Combined Sling and Training (n = 182) | Sling Only (n = 176) | Combined Sling and Training (n = 181) | Sling Only (n = 174) | |

| UDI Total Score (Primary)c | ||||||||

| Score, unadjusted, mean (SD) | 178.0 (42.8) | 176.8 (40.5) | 35.4 (44.1) | 37.2 (44.4) | 30.4 (40.1) | 36.6 (49.6) | 30.7 (42.6) | 34.5 (44.7) |

| Difference from baseline, adjusted mean (95% CI) | −125.7 (−143.4 to −107.9) |

−119.9 (−137.6 to −102.3) |

−126.5 (−144.2 to −108.8) |

−118.2 (−135.8 to −100.7) |

−128.1 (−146.5 to −109.8) |

−114.7 (−133.3 to −96.2) |

||

| Difference-in-difference, adjusted mean (95% CI) | −5.7 (−15.8 to 4.4) | −8.3 (−18.0 to 1.5) | −13.4 (−25.9 to −1.0) | |||||

| P value | .27 | .10 | .04 | |||||

| UDI-Irritative Score (Secondary)d | ||||||||

| Score, unadjusted mean (SD) | 66.0 (19.6) | 67.6 (19.7) | 15.5 (20.5) | 16.9 (21.9) | 12.2 (17.7) | 16.4 (24.0) | 12.2 (18.7) | 15.1 (21.2) |

| Difference from baseline, adjusted mean (95% CI) | −42.7 (−50.7 to −34.6) |

−41.1 (−49.1 to −33.1) |

−43.4 (−51.5 to −35.4) |

−40.4 (−48.3 to −32.4) |

−45.0 (−53.4 to −36.6) |

−38.9 (−47.4 to −30.3) |

||

| Difference in difference, adjusted mean (95% CI) | −1.6 (−6.2 to 3.1) | −3.1 (−7.5 to 1.4) | −6.1 (−12.1 to −0.2) | |||||

| P value | .51 | .18 | .04 | |||||

| UDI-Stress Score (Secondary)d | ||||||||

| Score, unadjusted mean (SD) | 86.0 (17.6) | 84.9 (18.0) | 14.6 (22.7) | 14.6 (21.0) | 14.1 (21.5) | 15.3 (23.9) | 13.3 (22.0) | 15.3 (23.5) |

| Difference from baseline, adjusted mean (95% CI) | −66.4 (−75.2 to −57.7) |

−65.1 (−73.8 to −56.4) |

−66.6 (−75.3 to −58.0) |

−64.0 (−72.6 to −55.3) |

−67.1 (−76.1 to −58.1) |

−61.6 (−70.7 to −52.6) |

||

| Difference in difference, adjusted mean (95% CI) | −1.3 (−6.4 to 3.8) | −2.7 (−7.5 to 2.2) | −5.5 (−11.5 to 0.6) | |||||

| P value | .62 | .28 | .08 | |||||

Abbreviation: UDI, Urogenital Distress Inventory.

Difference from baseline, difference in difference, and P values are derived from longitudinal treatment models that accounted for multiple observations per participant and were adjusted for time since baseline and interaction between treatment and time, re-treatment and interactions with treatment and time, baseline incontinence severity, and clinical site, which accounted for multiple observations per participant.

Sample sizes present the number of participants with observed data at each time point excluding data after retreatment.

The UDI total score ranges from 0 to 300; the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) is 35 points, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity.

The UDI subscales range from 0 to 100; the MCID is 15 points for irritative and 8 points for stress incontinence, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity.

Figure 2. Unadjusted Reduction From Baseline in Urinary Symptoms Based on Total Score From Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) Long Form Total.

The unadjusted change from baseline of the primary outcome of the study is shown in the analysis population at each time point after baseline by treatment group. See the Methods section for UDI total score range definitions.

Secondary Outcomes

The unadjusted mean UDI-irritative scores for the combined group were 66.0 points at baseline and 12.2 points, at 12 months, for an adjusted mean change of −45.0 points (95% CI, −53.4 to −36.6) vs sling-group unadjusted mean scores of 67.6 points at baseline and 15.1 points at 12 months, for an adjusted mean change of −38.9 points (95% CI, −47.4 to −30.3). The model-estimated between-group difference (−6.1 points; 95% CI, −12.1 to −0.2; P = .04) did not meet the MCID threshold. The unadjusted mean UDI-stress scores for the combined group were 86.0 at baseline and 13.3 at 12 months, for an adjusted mean change of −67.1 points (95% CI, −76.1 to −58.1) vs the sling group unadjusted mean scores of 84.9 at baseline and 15.3 at 12 months, for an adjusted mean change of −61.6 (95% CI, −70.7 to −52.6). The model-estimated between-group difference (−5.5 points; 95% CI, −11.5 to 0.6; P = .08) was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Other Outcomes

Prespecified exploratory and adverse event outcomes appear in Table 3 and Table 4. Bladder diary outcomes were more favorable for the combined group, including significantly greater mean reductions in urgency incontinence episodes (−1.1 vs −0.4 daily episodes; adjusted difference, −0.7; 95% CI, −1.2 to −0.1; P = .02) and total incontinence (−2.4 vs −1.4; daily episodes difference, −1.0; 95% CI, −1.7 to −0.2; P = .009). The combined group had significantly greater improvements in IIQ scores, which reached the MCID.21

Table 3. Prespecified Exploratory Through 12 Monthsa.

| Outcome Type | Combined Sling and Training | Sling Only | P Value | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 12 Months, Unadjusted | Difference From Baseline, Adjusted Mean (95% CI) | Baseline | 12 Months, Unadjusted | Difference From Baseline, Adjusted Mean (95% CI) | Difference in Difference or Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||||||

| No.b | Mean (SD) No. (%) |

No. | Mean (SD) No. (%) |

No. | Mean (SD) No. (%) |

No. | Mean (SD) No. (%) |

|||||

| Bladder Diary Outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Incontinence episodes per day | ||||||||||||

| Stress | 235 | 2.4 (2.2) | 164 | 0.1 (0.5) | −1.2 (−1.9 to −0.5) |

229 | 2.4 (1.7) | 161 | 0.1 (0.5) | −1.0 (−1.6 to −0.3) |

−0.2 (−0.6 to 0.1) |

.22 |

| Urge | 235 | 2.7 (2.3) | 164 | 0.4 (0.9) | −1.1 (−1.8 to −0.3) |

229 | 2.8 (2.7) | 161 | 0.6 (1.7) | −0.4 (−1.2 to 0.4) |

−0.7 (−1.2 to −0.1) |

.02 |

| Total | 235 | 5.6 (3.3) | 164 | 0.7 (1.4) | −2.4 (−3.5 to −1.3) |

229 | 5.6 (3.4) | 161 | 0.9 (2.0) | −1.4 (−2.5 to −0.3) |

−1.0 (−1.7 to −0.2) |

.009 |

| Pads, No. per day | 235 | 3.6 (3.2) | 164 | 0.8 (1.5) | −1.8 (−2.7 to −0.9) |

229 | 3.3 (2.8) |

161 | 0.8 (1.7) | −0.9 (−1.8 to 0.0) |

−0.9 (−1.5 to −0.3) |

.003 |

| Voids, No. per day | ||||||||||||

| Daytime | 235 | 8.1 (2.6) | 164 | 6.1 (1.4) | −2.2 (−3.1 to −1.4) |

229 | 8.2 (2.6) |

161 | 7.1 (2.2) | −1.3 (−2.1 to −0.5) |

−0.9 (−1.5 to −0.4) |

<.001 |

| Nighttime | 235 | 1.6 (1.3) | 164 | 0.9 (1.0) | −0.6 (−0.9 to −0.2) |

229 | 1.5 (1.2) | 161 | 1.0 (1.2) | −0.3 (−0.7 to 0.0) |

−0.2 (−0.5 to 0.0) |

.07 |

| Void frequency, No. (%)c | ||||||||||||

| Normalization | 108 | 80 (74.1) | 105 | 48 (45.7) | 4.75 (2.18 to 10.37) |

<.001 | ||||||

| High voiding | 164 | 34 (20.7) | 161 | 68 (42.2) | 0.33 (0.18 to 0.61) |

<.001 | ||||||

| Other Outcomes at 12 Months | ||||||||||||

| IIC total scored | 233 | 184.6 (95.8) | 180 | 24.3 (58.3) | −131.7 (−165.8 to −97.5) |

229 | 181.1 (95.8) | 174 | 28.0 (61.8) | −102.0 (−136.5 to −67.5) |

−29.7 (−51.9 to −7.4) |

.009 |

| OAB score | ||||||||||||

| Symptom severitye | 232 | 62.2 (21.3) | 179 | 12.9 (18.2) | −36.5 (−44.8 to −28.1) |

228 | 63.8 (21.7) | 173 | 15.4 (20.2) | −32.6 (−41.0 to −24.1) |

−3.9 (−9.6 to 1.8) |

.18 |

| HRQLe | 233 | 50.9 (23.7) | 179 | 93.1 (15.6) | 33.8 (25.2 to 42.4) |

228 | 50.7 (23.9) | 172 | 92.1 (15.7) | 29.1 (20.4 to 37.8) |

4.7 (−1.0 to 10.4) |

.10 |

| Treatment satisfactionf | 178 | 82.7 (22.4) | 77.0 (69.8 to 84.2) |

174 | 81.9 (26.5) | 73.2 (65.7 to 80.8) |

3.8 (−2.5 to 10.0) |

.24 | ||||

| PGI, No. (%) | ||||||||||||

| Severityg | 234 | 47 (20.1) | 179 | 163 (91.1) | 229 | 41 (17.9) | 174 | 155 (89.1) | 1.65 (0.80 to 3.39) |

.17 | ||

| Improvementh | 180 | 158 (87.8) | 174 | 147 (84.9) | 1.73 (0.92 to 3.25) |

.09 | ||||||

| Additional treatment, No. (%) | 235 | 20 (8.5) | 229 | 36 (15.7) | 0.47 (0.26 to 0.85) |

.01 | ||||||

Abbreviation: HRQL, health-related quality of life; IIC, Incontinence Impact Questionnaire; MCID minimally clinically important difference; OAB, Overactive Bladder Questionnaire; PGI Patient Global Impression questionnaire.

Difference from baseline, difference in difference, odds ratios, and P values were derived from longitudinal treatment models that accounted for multiple observations per participant and were adjusted for time since baseline and interaction between treatment and time, re-treatment and interactions with treatment and time, baseline incontinence severity, and clinical site.

Sample sizes present the number of participants with observed data at each time point excluding data after re-treatment.

High voiding frequency indicates more than 8 voids per day; normalization of voiding frequency was calculated for participants with high-voiding frequency at baseline; and normalization occurred if voids decreased to 8 or fewer per day.

Score ranges from 0 to 400 points; MCID is 16 points (higher scores indicate worse quality of life).

Score ranges from 0 to 100, MCID is 10 points (higher scores indicate greater symptom severity), and HRQL score ranges from 0 to 100, MCID is 10 points (higher scores indicate better HRQL).

Score ranges from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating greater treatment satisfaction.

Normal to mild are compared with moderate to severe.

Much better to very much better are compared with all other categories.

Table 4. Adverse Events Through 12 Months.

| Combined Sling and Training | Sling Only | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients | No. (%) of Events | No. of Patients | No. (%) of Events | |

| Worsening urgencya | 242 | 11 (4.5) | 238 | 5 (2.1) |

| New or worsening symptoms | ||||

| Abdominal or genital paina | 242 | 28 (11.6) | 238 | 36 (15.1) |

| Dyspareuniaa | 242 | 29 (12.0) | 238 | 35 (14.7) |

| Sensation of difficulty emptying bladdera | 242 | 32 (13.2) | 238 | 31 (13.0) |

| Vaginal mesh exposure | 242 | 4 (1.7) | 238 | 1 (0.4) |

| ED for complicationb | 242 | 5 (2.1) | 238 | 0 |

| Reoperationc | 242 | 3 (1.2) | 238 | 4 (1.7) |

Abbreviation: ED, emergency department; MCID minimally clinically important difference.

Adverse symptoms reported at or beyond 3 months were defined based on patient verbal report to clinician or a reported response on a postbaseline patient questionnaire of urgency incontinence, abdominal or genital pain, or difficulty emptying bladder or dyspareunia that was worse than the baseline reported response.

Reasons for ED visits were urinary retention (n = 3), acute pyelonephritis (n = 1), lower abdominal pain (n = 1).

Reoperations were for sling release (n = 3), mesh excision (n = 2), cystotomy (n = 2).

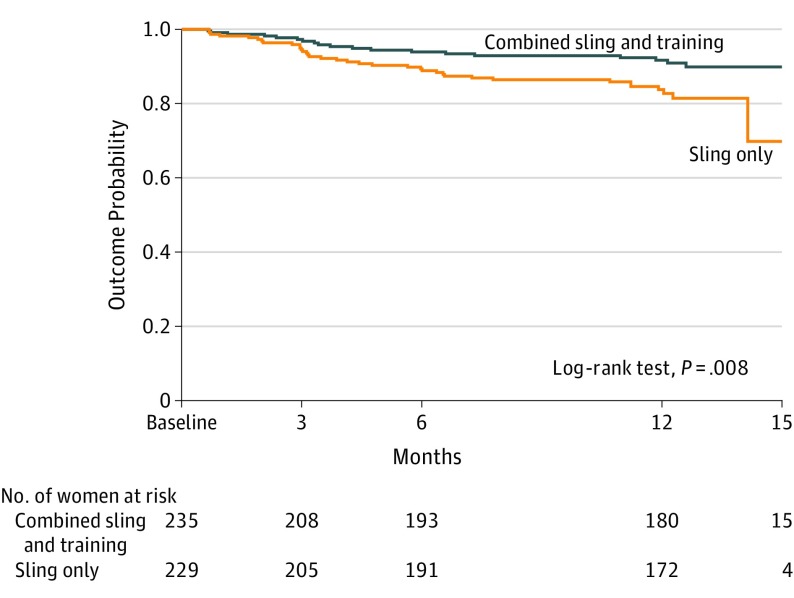

At 12 months, the combined group was significantly less likely to receive additional treatment for lower urinary tract symptoms than were the sling-only group (8.5% vs 15.7%, adjusted odds ratio, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.26-0.85). Time to additional treatment was greater in the combined group, as shown in the Kaplan-Meier curve, Figure 3 (log-rank test, P = .008). Additional treatments for lower urinary tract symptoms included overactive bladder medication (18 combined, 30 sling only), sling revision for incomplete bladder emptying (1 combined, 1 sling only), or referral to physical therapy (1 combined, 1 sling only). Other treatments in the sling-only group included posterior tibial nerve stimulation (n=1), continence pessary (n=1), and voiding dysfunction medication (n=2). The last time point at which each re-treated participant was included in statistical models appear in eTable 4 in Supplement 3.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier Probability Curve for Additional Treatment Between Groups.

The probability-of-outcome curve shows length of time after initiation of the intervention until occurrence of receiving additional treatment for any urinary symptom. There was a significant difference in survival times between the treatment groups. The median time to treatment for retreated individuals was 122 days (interquartile range [IQR], 87-210) for the combined treatment group (sling and behavioral and pelvic muscle training) and 113 days (IQR, 72-223) for the sling-only group.

Complications related to the intervention appear in eTable 5 in Supplement 3 and all collected adverse events (related or unrelated as determined by the site investigator at the time of event reporting) appear in eTable 6 in Supplement 3. Serious adverse events occurred in overall 10.2% of the study population (8.7% combined and 11.8% sling only). Of these, 2.3% were considered to be possibly, probably, or definitely related to the intervention per the site investigator. Vaginal mesh exposure occurred in overall 1% (1.7% of combined and 0.4% sling only). Worsening urgency incontinence occurred in 4.5% of combined and 2.1% in the sling-only group.

MCID Estimates From Study Data

The PGI-I measure was selected as the most clinically relevant anchor with MCIDs of 26.1 for the UDI total score, 10.2 for the UDI-irritative, and 5.4 for the UDI-stress subscale scores. These estimates did not change the overall findings.

Discussion

In this clinical trial involving women with mixed urinary incontinence, behavioral and pelvic floor muscle therapy combined with midurethral sling surgery, compared with surgery alone, resulted in a small statistically significant difference in urinary incontinence symptoms at 12 months. However, this difference did not meet the prespecified threshold for clinical importance.

This intervention was designed to concurrently improve both components of mixed urinary incontinence, a difficult-to-treat condition. Previous studies have shown that combined treatment improves continence after prostatectomy27,28 and recovery after hip arthroplasty.29 For pelvic floor disorders, the data are inconsistent. In 1 study,12 pelvic organ prolapse, stress incontinence, or both resulted in better urinary and quality-of-life outcomes 3 months after surgery for those who received combined treatment. Alternatively, another study10 found combined treatment did not improve outcomes among women undergoing surgery for prolapse and stress incontinence compared with surgery alone.

Previous studies and treatment guidelines have reported that the sling procedure can worsen urgency urinary incontinence,5,6,7,8 resulting in additional treatment rates to be as high as 25%.9,26 Clinical guidelines recommend treating the urgency component prior to consideration of surgery because of this concern. Both groups in this study reported large reductions in urgency symptoms and had a lower rate (12%) of undergoing additional urinary treatments. Although the ESTEEM trial did not specifically evaluate whether treating urgency incontinence before surgery is beneficial, this study population was not actively receiving treatment for bothersome urgency incontinence, yet still improved. It is possible that time spent medically managing the urgency component may unnecessarily delay surgery. Additionally, overactive bladder medications can have limited efficacy, poor adherence, and adverse effects including potentially irreversible anticholinergic cognitive changes.30 This information may help to guide patient care, referral patterns, and future research.

The overall number of serious adverse events and complications in this study is comparable with previous studies evaluating midurethral sling.15,17 Although the overall serious adverse event rate was 10% in this trial, the majority were not deemed to be related to the intervention. The rate of vaginal mesh exposure in this study was 1%, comparable with previously reported rates between 0.3% and 2.7%, and the reoperation rate was less than 2%, also consistent with prior studies.15,17 The overall rate of worsening urgency incontinence was low at less than 5%.

There is currently no objective criterion standard or clinically meaningful marker for measuring mixed urinary incontinence severity.31,32 Patient-reported outcomes were chosen as the primary outcome because the severity of urinary incontinence is primarily dependent on patient perspective. This trial was powered to detect published MCIDs to guide interpretation of a clinically meaningful difference between groups. For any individual woman, the published MCID estimate may not correlate with her personal perception and definition of improvement. Patients with changes in scores less than these estimates may still perceive important improvements. Important secondary and exploratory outcomes may also be informative, and it is important to interpret a trial based on the totality of findings.33 In this study, prespecified exploratory outcomes including bladder diary parameters, additional lower urinary tract treatments, and quality of life were improved in the combined group. Other subjective outcomes including the PGI-I and OAB symptom questionnaires were not significantly different between groups.

Strengths of the study include a large, nationally representative sample, adequately powered to determine differences in mixed, stress, and urgency urinary incontinence symptoms separately, and the use of patient-reported outcomes that account for the individual’s own symptom assessment. Inclusion criteria for symptom severity included patient report of bother and objective evidence of stress and urgency incontinence by bladder diary, increasing the generalizability of the study findings. The study intervention was standardized with centralized training of interventionists, including a published description of the program focused on evidence-based components. In addition, the surgical treatment of mixed urinary incontinence has remained controversial and the current study provides information needed for patient counseling and treatment guidelines.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, there was a lack of well-established MCIDs for women with mixed urinary incontinence when this study was designed. Recognizing this, MCID estimates were explored for this population with no effect on the findings. Second, participants were not masked, although it would be expected that masking would result in even smaller differences between groups. Third, a ceiling effect for the UDI as it relates to the population with mixed urinary incontinence is possible, limiting the ability to detect larger differences. Fourth, the combined intervention was perioperative and did not assess a postoperative approach that could be reserved for women who have persistent symptoms. Future analyses can help inform which patients are at risk of having persistent symptoms after midurethral sling and help focus future treatment efforts on this high-risk group.

Conclusions

Among women with mixed urinary incontinence, behavioral and pelvic floor muscle therapy combined with midurethral sling surgery, compared with surgery alone, resulted in a small statistically significant difference in urinary incontinence symptoms at 12 months that did not meet the prespecified threshold for clinical importance.

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plant

eMethods. Estimation of minimal clinical important differences for the Urogenital Distress Inventory in the ESTEEM population – description of methods

eTable 1. Other Baseline Characteristics of Eligible and Randomized Participants

eTable 2. Comparison of Primary Analysis and Multiple Imputation Results

eTable 3. Primary and Secondary Outcomes Through 12 Months, Post-Hoc Sensitivity Analysis with Site as a Random Effect

eTable 4. Timepoint at which Each Retreated Participant was Included in Statistical Models

eTable 5. Post-operative Complications

eTable 6. All Adverse Events by System Organ Class and Preferred Term Reported

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Minassian VA, Bazi T, Stewart WF. Clinical epidemiological insights into urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(5):687-696. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3314-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dooley Y, Lowenstein L, Kenton K, FitzGerald M, Brubaker L. Mixed incontinence is more bothersome than pure incontinence subtypes. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(10):1359-1362. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0637-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dmochowski R, Staskin D. Mixed incontinence: definitions, outcomes, and interventions. Curr Opin Urol. 2005;15(6):374-379. doi: 10.1097/01.mou.0000183946.96411.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myers DL. Female mixed urinary incontinence: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(19):2007-2014. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobashi KC, Albo ME, Dmochowski RR, et al. Surgical treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: AUA/SUFU Guideline. J Urol. 2017;198(4):875-883. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.06.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrams P, Andersson KE, Birder L, et al. ; Members of Committees; Fourth International Consultation on Incontinence . Fourth International Consultation on Incontinence Recommendations of the International Scientific Committee: evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and fecal incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29(1):213-240. doi: 10.1002/nau.20870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kammerer-Doak D, Rizk DE, Sorinola O, Agur W, Ismail S, Bazi T. Mixed urinary incontinence: international urogynecological association research and development committee opinion. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(10):1303-1312. doi: 10.1007/s00192-014-2485-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welk B, Baverstock RJ. The management of mixed urinary incontinence in women. Can Urol Assoc J. 2017;11(6Suppl2):S121-S124. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.4584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain P, Jirschele K, Botros SM, Latthe PM. Effectiveness of midurethral slings in mixed urinary incontinence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(8):923-932. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1406-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network . Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023-1034. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClurg D, Hilton P, Dolan L, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training as an adjunct to prolapse surgery: a randomised feasibility study. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(7):883-891. doi: 10.1007/s00192-013-2301-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarvis SK, Hallam TK, Lujic S, Abbott JA, Vancaillie TG. Peri-operative physiotherapy improves outcomes for women undergoing incontinence and or prolapse surgery: results of a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;45(4):300-303. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2005.00415.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung VW, Borello-France D, Dunivan G, et al. ; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network . Methods for a multicenter randomized trial for mixed urinary incontinence: rationale and patient-centeredness of the ESTEEM trial. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(10):1479-1490. doi: 10.1007/s00192-016-3031-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford AA, Rogerson L, Cody JD, Aluko P, Ogah JA. Mid-urethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD006375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):611-621. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318162f22e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moalli PA, Papas N, Menefee S, Albo M, Meyn L, Abramowitch SD. Tensile properties of five commonly used mid-urethral slings relative to the TVT. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(5):655-663. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0499-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richter HE, Albo ME, Zyczynski HM, et al. ; Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network . Retropubic versus transobturator midurethral slings for stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(22):2066-2076. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newman DK, Borello-France D, Sung VW. Structured behavioral treatment research protocol for women with mixed urinary incontinence and overactive bladder symptoms. Neurourol Urodyn. 2018;37(1):14-26. doi: 10.1002/nau.23244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dyer KY, Xu Y, Brubaker L, et al. ; Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network (UITN) . Minimum important difference for validated instruments in women with urge incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(7):1319-1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shumaker SA, Wyman JF, Uebersax JS, McClish D, Fantl JA; Continence Program in Women (CPW) Research Group . Health-related quality of life measures for women with urinary incontinence: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(5):291-306. doi: 10.1007/BF00451721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barber MD, Spino C, Janz NK, et al. ; Pelvic Floor Disorders Network . The minimum important differences for the urinary scales of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(5):580.e1-580.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yalcin I, Bump RC. Validation of two global impression questionnaires for incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):98-101. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margolis MK, Fox KM, Cerulli A, Ariely R, Kahler KH, Coyne KS. Psychometric validation of the overactive bladder satisfaction with treatment questionnaire (OAB-SAT-q). Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28(5):416-422. doi: 10.1002/nau.20672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coyne KS, Matza LS, Thompson CL. The responsiveness of the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire (OAB-q). Qual Life Res. 2005;14(3):849-855. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0706-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coyne KS, Matza LS, Thompson CL, Kopp ZS, Khullar V. Determining the importance of change in the overactive bladder questionnaire. J Urol. 2006;176(2):627-632. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.03.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdel-fattah M, Mostafa A, Young D, Ramsay I. Evaluation of transobturator tension-free vaginal tapes in the management of women with mixed urinary incontinence: one-year outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(2):150.e1-150.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goode PS, Burgio KL, Johnson TM II, et al. Behavioral therapy with or without biofeedback and pelvic floor electrical stimulation for persistent postprostatectomy incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(2):151-159. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacDonald R, Fink HA, Huckabay C, Monga M, Wilt TJ. Pelvic floor muscle training to improve urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy: a systematic review of effectiveness. BJU Int. 2007;100(1):76-81. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06913.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Husby VS, Helgerud J, Bjørgen S, Husby OS, Benum P, Hoff J. Early postoperative maximal strength training improves work efficiency 6-12 months after osteoarthritis-induced total hip arthroplasty in patients younger than 60 years. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89(4):304-314. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181cf5623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.This document was developed by the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) Guidelines Committee with the assistance of Tonya N. Thomas, MD, and Mark D. Walters, MD. This document reflects clinical and scientific advances as of the date issued and is subject to change. The information should not be construed as dictating an exclusive course of treatment or procedure to be followed. Its content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical judgment, diagnosis, or treatment. The ultimate judgment regarding any specific procedure or treatment is to be made by the physician and patient in light of all circumstances presented by the patient. AUGS Consensus Statement: Association of anticholinergic medication use and cognition in women with overactive bladder. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23(3):177-178.28441276 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brubaker L, Lukacz ES, Burgio K, et al. Mixed incontinence: comparing definitions in non-surgical patients. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(1):47-51. doi: 10.1002/nau.20922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brubaker L, Stoddard A, Richter H, et al. ; Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network . Mixed incontinence: comparing definitions in women having stress incontinence surgery. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28(4):268-273. doi: 10.1002/nau.20698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pocock SJ, Stone GW. The primary outcome fails—what next? N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):861-870. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1510064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

Statistical Analysis Plant

eMethods. Estimation of minimal clinical important differences for the Urogenital Distress Inventory in the ESTEEM population – description of methods

eTable 1. Other Baseline Characteristics of Eligible and Randomized Participants

eTable 2. Comparison of Primary Analysis and Multiple Imputation Results

eTable 3. Primary and Secondary Outcomes Through 12 Months, Post-Hoc Sensitivity Analysis with Site as a Random Effect

eTable 4. Timepoint at which Each Retreated Participant was Included in Statistical Models

eTable 5. Post-operative Complications

eTable 6. All Adverse Events by System Organ Class and Preferred Term Reported

Data Sharing Statement