This systematic review and meta-analysis investigates the association between obesity treatment interventions, with a dietary component, and symptoms of depression and anxiety in children and adolescents with overweight/obesity.

Key Points

Question

What is the association between pediatric obesity treatment with a dietary component and the change in depression and anxiety?

Findings

In this meta-analysis of 44 pediatric obesity treatment interventions, symptoms of depression and anxiety were reduced at postintervention and follow-up. Interventions of longer duration had a larger reduction in anxiety, and studies including participants with a higher baseline body mass index z score had a larger reduction in symptoms of depression.

Meaning

Pediatric obesity treatment is not associated with an increased risk of depression or anxiety over a 16-month follow-up.

Abstract

Importance

Children and adolescents with obesity are at higher risk of developing depression and anxiety, and adolescent dieting is a risk factor for the development of depression. Therefore, determining the psychological effect of obesity treatment interventions is important to consider.

Objective

To investigate the association between obesity treatment interventions, with a dietary component, and the change in symptoms of depression and anxiety in children and adolescents with overweight/obesity.

Data Sources

Searches of MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, and PsychINFO were conducted from inception to August 2018. Hand searching of references was conducted to identify missing studies.

Study Selection

Obesity treatment interventions, with a dietary component, conducted in children and adolescents (age <18 years) with overweight/obesity, and validated assessment of depression and/or anxiety were included.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data were independently extracted by 1 reviewer and checked for accuracy. Meta-analysis, using a random-effects model, was used to combine outcome data and moderator analysis conducted to identify intervention characteristics that may influence change in depression and anxiety. The meta-analyses were finalized in May 2019.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Change in symptoms of depression and anxiety postintervention and at the latest follow-up.

Results

Of 3078 articles screened, 44 studies met inclusion criteria with a combined sample of 3702 participants (age range, 5.6 to 16.6 years) and intervention duration of 2 weeks to 15 months. Studies reported either no change or a statistically significant reduction in symptoms of depression or anxiety. Meta-analyses of 36 studies found a reduction in depressive symptoms postintervention (standardized mean difference [SE], −0.31 [0.04]; P < .001), maintained at follow-up in 11 studies at 6 to 16 months from baseline (standardized mean difference [SE], −0.25 [0.07]; P < .001). Anxiety was reduced postintervention (10 studies; standardized mean difference [SE], −0.38 [0.10]; P < .001) and at follow-up (4 studies; standardized mean difference [SE], −0.32 [0.15]; P = .03). Longer intervention duration was associated with a greater reduction in anxiety (R2 = 0.82; P < .001). Higher body mass index z score at baseline was associated with a greater reduction in depression (R2 = 0.19; P = .03).

Conclusions and Relevance

Structured, professionally run pediatric obesity treatment is not associated with an increased risk of depression or anxiety and may result in a mild reduction in symptoms. Treatment of weight concerns should be considered within the treatment plan for young people with depression and obesity.

Introduction

In addition to increased physiological risk,1 children and adolescents with obesity experience poorer psychological well-being compared with their peers with healthy weight, including increased rates of depression2,3 and anxiety.4 A 2017 meta-analysis found that children and adolescents younger than 21 years with obesity have a 34% higher risk of developing depression and are more likely to present with depressive symptoms than their peers with healthy weight.5 Treatment-seeking children with obesity may display even higher levels of psychopathology,6 with one study reporting up to 50% of children and adolescents (N = 155) identified as having depression or anxiety-related psychiatric disorders.7

Obesity treatment aims to prevent or delay the progression of physiological comorbidities through lifestyle intervention, incorporating dietary change, increased physical activity, and behavior-modification strategies. Consequently, interventions aiming to reduce adiposity focus on weight and markers of cardiometabolic risk as measures of effectiveness.8,9,10 However, in light of the relationship between obesity and depression and anxiety, it is important to also consider the effect on psychological well-being.

Dieting during adolescence, defined as deliberate food restrictions for the purpose of weight loss, is also associated with higher levels of depression.11 Given that a hallmark of obesity treatment involves dietary restriction, it is important to consider the effects on depression. Although several studies report on depression and anxiety outcomes, the change in these following dietary obesity treatment has not been systematically reviewed in pediatric populations, to our knowledge. Thus, the aim of this systematic review with meta-analysis was to assess the association of obesity treatment, including a dietary component, with the change in depression and anxiety in children and adolescents with overweight or obesity.

Method

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline.12 This protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42017069496).13

Eligibility Criteria

Eligible studies recruited treatment-seeking children and/or adolescents (age ≤18 years) with overweight or obesity and were published in English. Randomized clinical trials (RCT), non-RCTs, noncontrolled trials, and retrospective medical record reviews were included. Interventions included a dietary component and excluded online interventions, pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgery. Individual-, family-, and group-based programs conducted in any setting were included. Studies were required to report the prevalence or symptoms of depression or anxiety using a validated assessment tool, at preintervention and postintervention or follow-up. Data at the latest follow-up were collected. Studies addressing prevention of overweight, treating psychological morbidity, or secondary or syndromic causes of obesity were excluded. No limitation was placed on date, intervention duration, or follow-up.

Search Strategy

Electronic databases MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, and PsychINFO were searched from inception to August 2018 (eTable 1 in the Supplement; search strategy). Hand searching of references was conducted to identify missing studies. Screening for eligible studies were conducted using Covidence online software (Vertitas Health Innovation Ltd). Records were independently assessed for inclusion in duplicate by title and abstract, then full text, based on the defined criteria, with discrepancies resolved through discussion.

Data Extraction

Data were independently extracted from eligible studies by 1 reviewer (H.J., M.L.G., and others) and cross-checked for accuracy. Extracted data included sample characteristics, intervention design and setting, outcome assessment tool, and preintervention to postintervention and follow-up data. Authors were contacted where pertinent data was not reported; studies were excluded if the required data could not be obtained.

Risk of Bias

Study quality was assessed using the US Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Quality Criteria Checklist: Primary Research14 by 2 reviewers (H.J., M.L.G., N.B.L., and others), with discrepancies resolved through discussion. The checklist allows an objective rating (positive, neutral, or negative) of quality. Studies receiving a neutral or positive outcome were included in meta-analysis. Publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of funnel plot symmetry, and the classic fail-safe N statistic15 interpreted as suggested by Rosenthal.16

Data Synthesis

Meta-analyses were performed to determine the change in symptoms of depression and anxiety from baseline to postintervention and follow-up using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis package, version 3.0 (Biostat) and presented as forest plots. A standardized mean difference (SMD) was used to combined outcome measures as a range of tools were used (where 0.2 indicates small; 0.5, medium; 0.8, large effect).17 All intervention arms were included in the meta-analysis. Meta-analysis of RCTs including a no-treatment control group was conducted to assess intervention effect. Moderator analysis was conducted to identify characteristics that are associated with a change in symptoms of depression and anxiety. Categorical moderators included setting, frequency of contact, physical activity, and energy prescription. Meta-regression of continuous variables included mean age and body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) z score at baseline, duration of intervention (weeks), and change in weight-related outcomes. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the I2 statistic. A random-effect model was used owing to assumed heterogeneity between studies. Two-sided P values of .05 or less were considered statistically significant.

Results

Included Studies

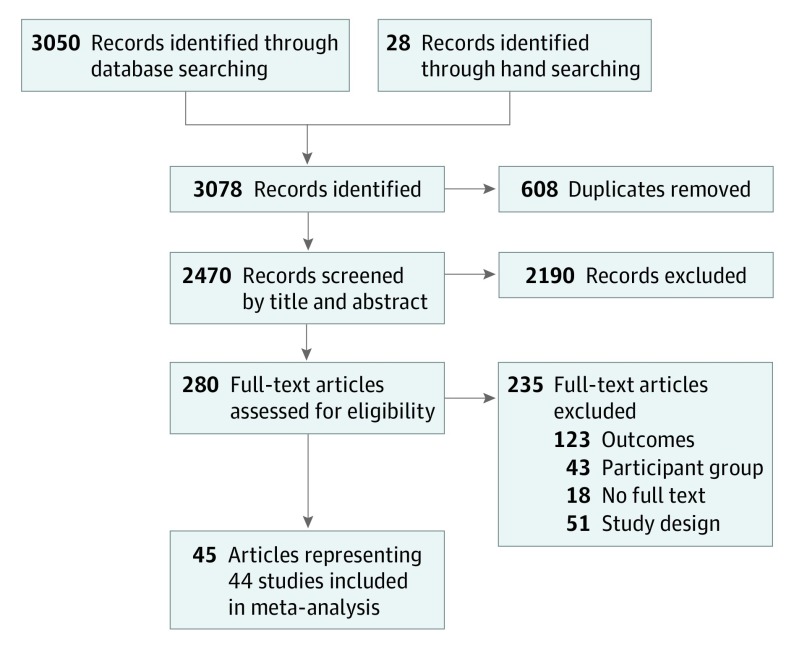

The search identified 3078 articles of which 44 studies, published between 1987 and 2018, were included (Figure 1). Study characteristics are in eTable 2 in the Supplement. Included study designs were noncontrolled trials in 21 studies,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39 16 RCTs,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55 6 non-RCTs,56,57,58,59,60,61 and 1 retrospective medical record review.62 Twenty studies were conducted in the United States,18,19,26,27,28,29,30,31,34,36,37,38,40,44,46,47,48,50,51,53,54 6 in the United Kingdom,21,33,42,55,57,62 3 each in Canada45,58,60 and Brazil,20,32,61 2 each in Australia41,56 and Belgium,24,39 with the remaining studies conducted in Germany,35 Iceland,25 Iran,52 Israel,22 Korea,59 Norway,43 Portugal,23 and Switzerland.49 Studies were conducted in community settings,19,25,28,30,31,33,41,43,45,46,48,51,52,55,56,61,62 tertiary hospital outpatient clinics,18,20,21,29,32,35,36,38,47,49,50,53,57,58,60 primary care facilities,26,27,42,44 hospitals (inpatient),24,39 residential camps,23,34,37 schools,54,59 and 1 study combining hospital inpatient and outpatient components.22

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram of the Literature Search and Screening Process.

Study sample size ranged from 12 to 435 participants with a mean age range of 5.6 to 16.6 years, BMI range of 24.6 to 44.9, and BMI z score range of 1.91 to 3.23 at baseline. Intervention duration ranged from 2 weeks to 15 months, with follow-up outcome measures in 16 studies.18,21,24,25,31,40,42,43,44,47,48,50,51,53,55,56 One study reported a 6-year follow-up,24 with the remaining studies reporting follow-up of 6 to 16 months from baseline. Frequency of contact ranged from daily to monthly.

Intervention Design

Nutrition education provided was based on local dietary guidelines, the Traffic Light Diet, and/or a range of specific topics including fruit and vegetable intake, reduced sugar-sweetened beverages, and portion sizes. A prescriptive energy target ranging from 800 to 1800 kcal per day was reported in 10 studies22,23,24,31,37,38,39,44,46,53 and an energy deficit of 250 kcal per day in 1 study.45 Energy intake was set to recommended energy requirements for participants with low levels of physical activity in 1 study,20 and another34 provided participants with individualized energy targets. Physical activity education alone was reported in 17 studies,18,21,26,27,33,40,41,42,43,44,46,47,49,50,51,53,57,59 with the inclusion of a supervised exercise program in 23 studies.20,22,23,24,28,29,30,31,32,34,35,37,38,39,45,48,52,55,56,58,60,61,62 Four studies25,36,40,54 did not report a physical activity component. Behavior modification strategies were addressed in 33 studies,18,20,21,22,23,24,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,46,48,49,51,55,56,58,59,60,62 including group-based or 1-on-1 counselling, goal setting, problem solving, self-monitoring, and stimulus control. The use of cognitive behavioral therapy22,24,26,27,34,38,39,41,43,44,46,48,49,51,55,62 or dialectical behavioral therapy18 as part of the intervention was reported in 16 studies. Depression,20,44 anxiety,19,20 or mental health58 were specifically addressed in 4 studies. Interventions were led by multidisciplinary teams (2 or more health care professionals) in 22 studies,19,20,22,23,24,25,28,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,42,44,45,47,52,56,58,60 including pediatricians, endocrinologist, dietitians/nutritionists, exercise physiologists/personal trainers or physiotherapists, and psychologists/counsellors. Eight studies did not report personnel involved in delivering the intervention,21,26,27,29,30,31,35,40,57 and 14 studies18,41,43,46,48,49,50,51,53,54,55,59,61,62 were delivered by a single health care professional or researcher. Depression and anxiety were measured using 21 validated assessment tools,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84 with the Children’s Depression Inventory72 most frequently used (14 studies).21,23,25,28,31,33,35,42,43,50,53,55,57,58

Risk of Bias Assessment

Ten of 45 articles obtained a positive quality rating, and 34 articles had a neutral rating (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Many studies received a neutral quality rating owing to the absence of a comparator group, or the intervention and participant selection procedures being poorly described. One study61 was excluded from meta-analysis owing to a negative quality rating.

Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety

The prevalence of depression and anxiety, assessed by clinical interview,76 was reported in 1 study.39 From 76 adolescents participating in a 10-month inpatient treatment program, the resolution of mood disorders was reported in 2 of 3 participants identified at baseline and anxiety disorder in 1 of 5 participants.39 One adolescent with no psychiatric disorder at baseline developed a major depressive disorder.

Change in Depressive Symptoms

The change in depressive symptoms was reported in 48 intervention arms within 40 studies; 20 intervention arms reported no change,22,24,26,27,28,32,34,37,40,41,42,45,46,47,50,51,54,56,59,60,61 and 2818,20,21,23,25,29,30,31,32,33,35,36,38,39,43,44,45,47,48,49,51,52,53,56,57,58,61,62 reported a statistically significant reduction in depressive symptoms postintervention (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Two studies reported that study completers had less depressive symptoms at baseline than noncompleters.28,57

Movement within and between categories of depressive symptoms were reported in 3 studies.35,44,52 DeBar et al44 reported a reduction in participants with a mood disorder from 10.6% to 6.4%. Toulabi et al52 reported a reduction in the number of participants with mild (20.5% to 14.5%) and moderate (7.2% to 2%) depression. In the study by Pott et al,35 25 of 136 enrolled participants were above the clinical cutoff for depression at baseline. At postintervention, 14 had reduced scores to below the cutoff postintervention, and 8 children had increased levels of depression to above the clinical cutoff. The authors noted that these participants came from families with higher psychosocial risk.

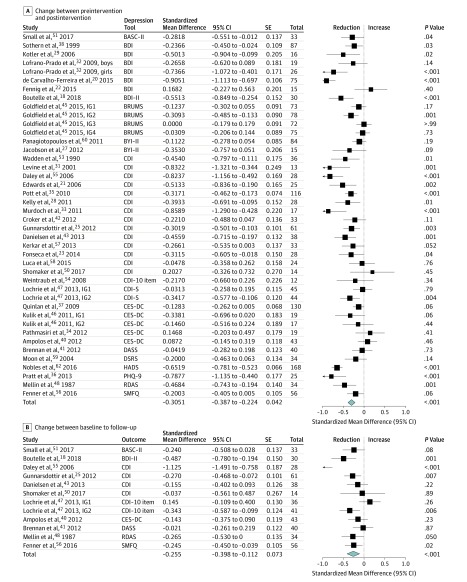

A meta-analysis of the intervention arms from 36 studies18,20,21,22,23,25,27,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,48,50,51,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,62 (n = 1878) demonstrated a small reduction in depressive symptoms (Figure 2A; SMD [SE], −0.31 [0.04]; P < .001; I2 = 77%) postintervention, which was maintained at follow-up of up to 16 months from baseline in 11 studies18,25,40,41,43,47,48,50,51,55,56 (Figure 2B; n = 454; SMD [SE], −0.26 [0.07]; P < .001; I2 = 72%). Publication bias is unlikely at postintervention (funnel plot symmetry; fail-safe n = 2482 studies) and follow-up (funnel plot symmetry; fail-safe n = 119 studies). Meta-analysis of 9 RCTs41,42,43,48,51,55,56,58,59 with an intervention arm (n = 327) and no-treatment control group (n = 288) indicated that there was no difference between groups (SMD [SE], −0.12 [0.10]; P = .23; I2 = 26%; favoring intervention group).

Figure 2. Change in Depressive Symptoms .

BASC-II indicates Behavioral Assessment System for Children, Second Edition; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory, Second Edition; BRUMS, Brunel Mood Scale; BYI-II, Beck Youth Inventories Second Edition; CDI, Children’s Depression Inventory; CDI-10 item, 10-Item Children's Depression Inventory; CDI-S, Children's Depression Inventory–Short Version; CES-DC, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children; DASS, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, Second Edition; DSRS, Depression Self-Rating Scale; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IG, intervention group; PHQ-9, 9-Item Patient Health Questionnaire; RDAS, Rosenberg’s Depressive Affect Scale; SMFQ, Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire.

Four studies were not included in the meta-analysis.24,30,49,61 Two studies30,49 reported a significant reduction in depressive symptoms postintervention. Stella et al61 reported a significant reduction in depressive symptoms in the aerobic exercise group and no change in the other groups. Goossens et al24 reported no change in depression at 6-year follow-up. Two studies32,37 reported a significant reduction in depression for girls but not for boys, and 2 studies20,23 found a significant reduction for both boys and girls.

There was a significant association between the change in depression and the intervention setting (Q = 18.66; P = .002), frequency of contact (Q = 13.12; P = .02), and use of an energy prescription (Q = 6.88; P = .009). Tertiary hospital outpatient programs were associated with the largest reduction in depressive symptoms (14 studies; SMD [SE], −0.40 [0.07]; P < .001) followed by community programs (16 studies; SMD [SE], −0.30 [0.05]; P < .001), with no significant change for studies conducted in a school,54 inpatient setting,22 or camp,23,34,37 although the number of studies is small and these findings should be interpreted with caution. No change in depression was found in the 5 studies providing daily contact (camps and inpatient programs; SMD [SE], −0.13 [0.10]; P = .21). Studies that had contact with participants weekly or biweekly (25 studies; SMD [SE], −0.34 [0.05]; P < .001) or as a staged approach, beginning weekly and reducing to monthly (2 studies; SMD [SE], −0.23 [0.10]; P = .01), were associated with a greater reduction in depressive symptoms. The 27 studies providing nutrition education (SMD [SE], −0.36 [0.05]; P < .001) were associated with a greater reduction in depressive symptoms than 9 studies reporting use of an energy prescription (SMD [SE], −0.17 [0.05]; P = .001). Interventions without a physical activity component did not have a change in depressive symptoms (4 studies; SMD [SE], −0.29 [0.18]; P = .10), but interventions with structured exercise classes (18 studies; SMD [SE], −0.33 [0.06]; P < .001) and interventions providing physical activity education alone (15 studies; SMD [SE], −0.28 [0.05]; P < .001) were associated with reduced depressive symptoms, although the difference between groups was not statistically significant (Q = 18.66; P = .002). One study included in the meta-analysis specifically addressed depression during the intervention20 and had a large effect size for reducing depressive symptoms (SMD [SE], −0.91 [0.11]; P < .001), following a 1-year intervention delivered weekly, compared with a smaller combined effect (SMD [SE], −0.29 [0.04]; P < .001) for the remaining studies, which did not address depression.

Meta-regression found higher mean BMI z score at baseline to be associated with a greater reduction in depressive symptoms (eFigure 1 in the Supplement) (R2 = 0.19; P = .03). No influence was found based on age or intervention duration.

Change in Anxiety

Of 13 studies19,25,26,27,31,32,39,41,49,50,51,60,61,62 that reported anxiety, 4 studies reported no change,26,27,41,50,51 8 reported a statistically significant reduction,19,25,31,32,39,49,60,62 and 1 study61 reported no change in the exercise groups and a reduction in the nutrition education group between preintervention and postintervention (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

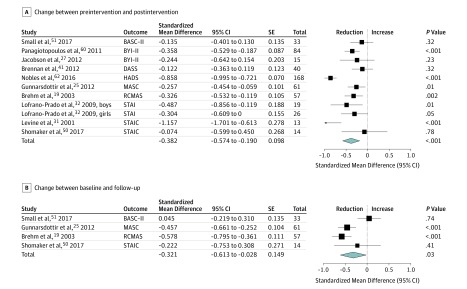

Meta-analysis of the intervention arms from 10 studies19,25,27,31,32,41,50,51,60,62 (n = 530; Figure 3A) found a small to medium reduction in anxiety postintervention (SMD [SE], −0.38 [0.10]; P < .001; I2 = 84%). Publication bias is unlikely postintervention (some funnel plot asymmetry; fail-safe n = 294 studies). The reduction in anxiety was maintained at follow-up of up to 16 months from baseline in 4 studies19,25,50,51 (Figure 3B; SMD [SE], −0.32 [0.15]; P = .03; I2 = 79%). Publication bias is possible at follow-up (funnel plot symmetry; fail-safe n = 23 studies). No difference between intervention and control groups was found postintervention in the 2 RCTs41,51 that measured anxiety. Two studies were not included in meta-analysis. One study49 reported a significant linear decrease of all anxiety measures between baseline and 6-month follow-up, and another61 reported a significant decrease in trait anxiety in the nutrition education group but not intervention groups with an exercise component.

Figure 3. Change in Anxiety .

BASC-II indicates Behavioral Assessment System for Children, Second Edition; BYI-II, Beck Youth Inventories Second Edition; DASS, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, Second Edition; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MASC, Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; RCMAS, Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; STAIC, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children.

There was a significant association between the change in anxiety and the included physical activity component (Q = 5.52; P = .02). Studies including structured exercise classes (4 studies; SMD [SE], −0.60 [0.15]; P < .001) had a greater reduction in anxiety compared with studies providing physical activity education alone (6 studies; SMD [SE], −0.22 [0.05]; P < .001). Although the difference was not statistically significant (Q = 1.27; P = .26), 2 studies with an energy prescription were associated with a greater reduction in anxiety (SMD [SE], −0.60 [0.22]; P = .007) compared with 8 interventions providing nutrition education alone (SMD [SE], −0.33 [0.11]; P = .004). No association for intervention setting or frequency of contact was found. Intervention duration was associated with change in anxiety, with longer interventions having a greater reduction (eFigure 2 in the Supplement) (R2 = 0.82; P < .001). No association was found for age or mean BMI z score at baseline.

Change in Weight-Related Outcomes

The intervention arms from 35 studies18,19,20,21,22,23,25,27,28,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,44,46,47,48,50,51,52,53,54,55,57,58,60,62 (n = 2077) found a reduction in weight-related outcomes (predominately BMI or BMI z score) postintervention (eFigure 3A in the Supplement) (SMD [SE], −0.41 [0.07]; P < .001; I2 = 91%). This was maintained in 14 studies18,19,24,25,31,40,41,43,44,47,48,50,51,55 up to 6 years from baseline (eFigure 3B in the Supplement) (SMD [SE], −0.27 [0.06]; P < .001; I2 = 80%). The mean difference (SE) for change in BMI z score in 20 studies was −0.13 (0.03) (P < .001) and BMI in 22 studies was −1.65 (0.47) (P < .001) postintervention. There was no difference in the change in weight-related outcomes between intervention and no-treatment control groups in 7 RCTs41,42,43,48,51,55,58 (SMD [SE], −0.14 [0.22]; P = .52; I2 = 79%; favoring intervention group). There was no association between change in depressive symptoms (R2 = −0.01; P = .37) or anxiety (R2 = 0.02; P = .32) with change in weight-related outcomes.

Discussion

This systematic review demonstrated that participation in structured and professionally run obesity treatment interventions with a dietary component was associated with a reduction in symptoms of depression and anxiety in the short term. This review, together with another review that assessed the association between pediatric obesity treatment interventions and eating disorder risk85 (12 studies overlap with this review), provides evidence that pediatric obesity treatment is not associated with adverse effects on psychological well-being.

Participation in obesity treatment, particularly during adolescence, may disrupt the progression of depressive symptoms. The natural trajectory of depressive symptoms from childhood to young adulthood peaks at age 14 to 17 years, followed by a reduction into early adulthood.86,87 Even a small reduction during obesity treatment may reduce the susceptibility to a worsening of symptoms at this vulnerable age, particularly as higher body weight is associated with an increased risk of developing depression.5 This should be considered an important treatment outcome. Our results indicate that a greater reduction in depressive symptoms was found in studies including participants with more severe obesity at baseline. This is consistent with a meta-analysis of 32 depression prevention programs that showed that programs targeting high-risk individuals resulted in a larger effect on depression.88 Access to professionally run treatment services for children and adolescents with more severe obesity is crucial to prevent both physiological and psychological comorbidity.

The safety profile of dieting undertaken by adolescents independently, compared with professionally administered interventions, can vary. Observational data suggest that adolescent dieting increases the risk of developing depression11 and is associated with weight gain,89 in contrast to this review, which show reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety following obesity treatment coupled with a reduction in weight-related outcomes. Interestingly, we did not find an association between the change in depressive symptoms and change in weight-related outcomes. Considering obesity treatment aims to address broader aspects of health affected by increased weight, it is possible that changes in depression and anxiety are mediated by changes in dietary intake and/or specific intervention components rather than weight loss per se.

Previous studies in children and adolescents have found an association between a healthy diet and reduced depression11,90 and lower-quality or unhealthy diets with increased depression and anxiety.90 This association may be mediated by adiposity and inflammation. In an Australian population-based longitudinal study of 843 adolescents, higher BMI at age 14 years was associated with higher BMI, higher leptin and highly sensitivity C-reactive protein concentrations, depressive symptoms, and mental health at age 17 years.91 A healthy dietary pattern appeared protective with less adiposity, inflammation, and mental health problems.91 In addition, consumption of nutrients consistent with a healthy diet (eg, magnesium, fiber, polyunsaturated fatty acids) is associated with decreased levels of inflammatory markers,92 and intake of saturated and trans fatty acids, carbohydrates with a high glycemic index, and a high ω-6/ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid ratio, consistent with poorer diet quality, is associated with increased levels of inflammation.92 It is possible that the nutrition education provided during the interventions included in this systematic review contributed to an improved quality of the diet, mediating the reduction in symptoms of depression and anxiety.

This review identified specific intervention components that may promote improved psychological well-being. Interventions with weekly or fortnightly contact with the study team showed the greatest reduction in depressive symptoms, and longer intervention duration was associated with a larger reduction in anxiety. This may be due to the regular and extended support of a health care team. This is supported by meta-analyses of depression88 and anxiety93 prevention programs conducted in children and adolescents that highlight that professionally delivered programs had a greater association compared with those delivered by lay providers. The inclusion of physical activity components may also influence depression and anxiety. Meta-analyses have shown that regular physical activity11,94 is associated with fewer depressive symptoms. Consistent with these findings, we found that interventions with a structured exercise program had a greater reduction in anxiety than physical activity education alone. A similar trend, although not statistically significant, was found for depressive symptoms. Exercise programs were often provided 2 to 3 days per week, increasing contact with study personnel. In addition, exercise was often delivered in a group format, which may create a positive peer experience.

Although most studies reported an overall reduction in depression, 2 studies reported a worsening of symptoms in a small number of participants. As trajectories of depressive symptoms normally increase across adolescence,86,87 these new cases may have occurred independent of involvement in obesity treatment, but this cannot be determined from available data. In addition, 2 studies28,57 highlighted that those with higher symptoms of depression were more likely to withdraw from the intervention. It is possible that young people with a higher degree of depressive symptoms may find engagement with the service and adherence to treatment more difficult and require additional support. Identification of those at risk of developing depression and provision of additional support to these young people should be considered.

Recommendations for Clinical Practice

Overall, obesity treatment interventions are not associated with increased symptoms of depression and anxiety. However, clinicians should be aware that a small proportion of participants may be at risk of developing worsening pathology. Identification of these young people and provision of additional support may improve treatment outcomes. Improvements in psychological well-being following treatment should also be used to identify treatment success.

Recommendations for Future Research

Obesity treatment interventions should include measurement of depression and anxiety preintervention and postintervention and at follow-up to build the evidence base in treatment-seeking populations. In particular, longer duration of follow-up is required. Reviews using individual patient data may provide a more accurate representation of predictive and protective factors and to identify red flags for those at risk of worsening pathology.

Strengths and Limitations

This review included a comprehensive search of the literature and addressed concerns about professionally run obesity treatment interventions with a dietary component in the short term. There are also some limitations. Only a small proportion of obesity treatment interventions include a measure of depression at preintervention and postintervention; fewer interventions measure anxiety and provide follow-up data. Many studies reported completer analysis so participants who withdrew from treatment are not well represented in these data (retention ranged from 42% to 100%). Publication bias is always possible. Use of the fail-safe N statistic provided a rigorous assessment of bias compared with funnel plots alone. A small number of participants may experience a worsening in symptoms of depression and anxiety, and these outliers are not well represented in sample means.

Conclusions

Structured and professionally run obesity treatment with a dietary component is associated with improvements in depression and anxiety for most participants. A small proportion of young people may be at risk of worsening pathology and may require additional support. Treatment of weight concerns should be considered within the treatment plan for young people with depression and obesity.

eTable 1. Search strategy used on the Ovid platform with the Medline database

eTable 2. Characteristics of included studies

eFigure 1. Meta-regression of the effect size for change in symptoms of depression between pre- and post-intervention and mean participant BMI z-score at baseline following professionally administered obesity treatment with a dietary component in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity (R2=0.18, p=0.02)

eFigure 2. Meta-regression of the effect size for change in symptoms of anxiety between pre- and post-intervention and intervention duration following professionally administered obesity treatment with a dietary component in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity (R2=0.82, p<0.001)

eFigure 3. Meta-analysis of the change in weight-related outcomes between pre- and post-intervention (A) and between baseline and the latest follow-up timepoint (B), following obesity treatment with a dietary component in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity

eReferences.

References

- 1.Steinbeck KS, Lister NB, Gow ML, Baur LA. Treatment of adolescent obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(6):-. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0002-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mühlig Y, Antel J, Föcker M, Hebebrand J. Are bidirectional associations of obesity and depression already apparent in childhood and adolescence as based on high-quality studies? a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2016;17(3):235-249. doi: 10.1111/obr.12357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders RH, Han A, Baker JS, Cobley S. Childhood obesity and its physical and psychological co-morbidities: a systematic review of Australian children and adolescents. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(6):715-746. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2551-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puder JJ, Munsch S. Psychological correlates of childhood obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010;34(suppl 2):S37-S43. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quek YH, Tam WWS, Zhang MWB, Ho RCM. Exploring the association between childhood and adolescent obesity and depression: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2017;18(7):742-754. doi: 10.1111/obr.12535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puhl RM, Latner JD. Stigma, obesity, and the health of the nation’s children. Psychol Bull. 2007;133(4):557-580. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vila G, Zipper E, Dabbas M, et al. Mental disorders in obese children and adolescents. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(3):387-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Khudairy L, Loveman E, Colquitt JL, et al. Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese adolescents aged 12 to 17 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD012691. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mead E, Brown T, Rees K, et al. Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese children from the age of 6 to 11 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD012651. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho M, Garnett SP, Baur L, et al. Effectiveness of lifestyle interventions in child obesity: systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1647-e1671. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cairns KE, Yap MBH, Pilkington PD, Jorm AF. Risk and protective factors for depression that adolescents can modify: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Affect Disord. 2014;169:61-75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The impact of weight management interventions on psychological wellbeing in children and adolescents with overweight/obesity: a systematic review. PROSPERO. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=69496. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- 14.Handu D, Moloney L, Wolfram T, Ziegler P, Acosta A, Steiber A. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics methodology for conducting systematic reviews for the evidence analysis library. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(2):311-318. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Card NA. Applied Meta-Analysis for Social Science Research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(3):638-641. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Science & Technology; 2013. doi: 10.4324/9780203771587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boutelle KN, Braden A, Knatz-Peck S, Anderson LK, Rhee KE. An open trial targeting emotional eating among adolescents with overweight or obesity. Eat Disord. 2018;26(1):79-91. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2018.1418252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brehm BJ, Rourke KM, Cassell C, Sethuraman G. Psychosocial outcomes of a pilot multidisciplinary program for weight management. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(4):348-354. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.27.4.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Carvalho-Ferreira JP, Masquio DC, da Silveira Campos RM, et al. Is there a role for leptin in the reduction of depression symptoms during weight loss therapy in obese adolescent girls and boys? Peptides. 2015;65:20-28. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards C, Nicholls D, Croker H, Van Zyl S, Viner R, Wardle J. Family-based behavioural treatment of obesity: acceptability and effectiveness in the UK. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60(5):587-592. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fennig S, Brunstein-Klomek A, Sasson A, Halifa Kurtzman I, Hadas A. Feasibility of a dual evaluation/intervention program for morbidly obese adolescents. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2015;52(2):107-112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fonseca H, Palmeira AL, Martins S, Ferreira PD. Short- and medium-term impact of a residential weight-loss camp for overweight adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2014;26(1):33-38. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2012-0107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goossens L, Braet C, Verbeken S, Decaluwé V, Bosmans G. Long-term outcome of pediatric eating pathology and predictors for the onset of loss of control over eating following weight-loss treatment. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44(5):397-405. doi: 10.1002/eat.20848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gunnarsdottir T, Njardvik U, Olafsdottir AS, Craighead L, Bjarnason R. Childhood obesity and co-morbid problems: effects of Epstein’s family-based behavioural treatment in an Icelandic sample. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18(2):465-472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01603.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobson D. A Primary Care School age Healthy Choices Intervention Program [dissertation]. Tempe: Arizona State University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobson D, Melnyk BM. A primary care healthy choices intervention program for overweight and obese school-age children and their parents. J Pediatr Health Care. 2012;26(2):126-138. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2010.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly NR, Mazzeo SE, Evans RK, et al. Physical activity, fitness and psychosocial functioning of obese adolescents. Ment Health Phys Act. 2011;4(1):31-37. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2010.11.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotler LA, Etu SF, Davies M, Devlin MJ, Attia E, Walsh BT. An open trial of an intensive summer day treatment program for severely overweight adolescents. Eat Weight Disord. 2006;11(4):e119-e122. doi: 10.1007/BF03327576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lane-Tillerson C, Davis BL, Killion CM, Baker S. Evaluating nursing outcomes: a mixed-methods approach. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2005;16(2):20-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levine MD, Ringham RM, Kalarchian MA, Wisniewski L, Marcus MD. Is family-based behavioral weight control appropriate for severe pediatric obesity? Int J Eat Disord. 2001;30(3):318-328. doi: 10.1002/eat.1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lofrano-Prado MC, Antunes HK, do Prado WL, et al. Quality of life in Brazilian obese adolescents: effects of a long-term multidisciplinary lifestyle therapy. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:61. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murdoch M, Payne N, Samani-Radia D, et al. Family-based behavioural management of childhood obesity: service evaluation of a group programme run in a community setting in the United Kingdom. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(6):764-767. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pathmasiri W, Pratt KJ, Collier DN, Lutes LD, McRitchie S, Sumner SCJ. Integrating metabolomic signatures and psychosocial parameters in responsivity to an immersion treatment model for adolescent obesity. Metabolomics. 2012;8(6):1037-1051. doi: 10.1007/s11306-012-0404-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pott W, Albayrak O, Hebebrand J, Pauli-Pott U. Course of depressive symptoms in overweight youth participating in a lifestyle intervention: associations with weight reduction. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31(8):635-640. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181f178eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pratt KJ, Lazorick S, Lamson AL, Ivanescu A, Collier DN. Quality of life and BMI changes in youth participating in an integrated pediatric obesity treatment program. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:116. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinlan NP, Kolotkin RL, Fuemmeler BF, Costanzo PR. Psychosocial outcomes in a weight loss camp for overweight youth. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2009;4(3):134-142. doi: 10.1080/17477160802613372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sothern MS, von Almen TK, Schumacher HD, Suskind RM, Blecker U. A multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of childhood obesity. Del Med J. 1999;71(6):255-261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vlierberghe LV, Braet C, Goossens L, Rosseel Y, Mels S. Psychological disorder, symptom severity and weight loss in inpatient adolescent obesity treatment. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2009;4(1):36-44. doi: 10.1080/17477160802220533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ampolos L. The Role of Nutritional Intake in Weight and Depressive Symptomatology on Children Participating in Family-Based Therapy for Weight Reduction [dissertation]. San Diego: Alliant International University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brennan L, Wilks R, Walkley J, Fraser SF, Greenway K. Treatment acceptability and psychosocial outcomes of a randomised controlled trial of a cognitive behavioural lifestyle intervention for overweight and obese adolescents. Behav Change. 2012;29(1):36-62. doi: 10.1017/bec.2012.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Croker H, Viner RM, Nicholls D, et al. Family-based behavioural treatment of childhood obesity in a UK National Health Service setting: randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012;36(1):16-26. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Danielsen YS, Nordhus IH, Júlíusson PB, Mæhle M, Pallesen S. Effect of a family-based cognitive behavioural intervention on body mass index, self-esteem and symptoms of depression in children with obesity (aged 7-13): a randomised waiting list controlled trial. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2013;7(2):e116-e128. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2012.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeBar LL, Stevens VJ, Perrin N, et al. A primary care-based, multicomponent lifestyle intervention for overweight adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e611-e620. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldfield GS, Kenny GP, Alberga AS, et al. Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on psychological health in adolescents with obesity: the HEARTY randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(6):1123-1135. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kulik N. Social Support and Weight Loss Among Adolescent Females [dissertation]. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lochrie A, Wysocki T, Hossain J, et al. The effects of a family-based intervention (FBI) for overweight/obese children on health and psychological functioning. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol. 2013:1(2);159–170. doi: 10.1037/cpp0000020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mellin LM, Slinkard LA, Irwin CE Jr. Adolescent obesity intervention: validation of the SHAPEDOWN program. J Am Diet Assoc. 1987;87(3):333-338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munsch S, Roth B, Michael T, et al. Randomized controlled comparison of two cognitive behavioral therapies for obese children: mother versus mother-child cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(4):235-246. doi: 10.1159/000129659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Matherne CE, et al. A randomized, comparative pilot trial of family-based interpersonal psychotherapy for reducing psychosocial symptoms, disordered-eating, and excess weight gain in at-risk preadolescents with loss-of-control-eating. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(9):1084-1094. doi: 10.1002/eat.22741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Small L, Thacker L II, Aldrich H, Bonds-McClain D, Melnyk B. A pilot intervention designed to address behavioral factors that place overweight/obese young children at risk for later-life obesity. West J Nurs Res. 2017;39(8):1192-1212. doi: 10.1177/0193945917708316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toulabi T, Khosh Niyat Nikoo M, Amini F, Nazari H, Mardani M. The influence of a behavior modification interventional program on body mass index in obese adolescents. J Formos Med Assoc. 2012;111(3):153-159. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2011.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, Rich L, Rubin CJ, Sweidel G, McKinney S. Obesity in black adolescent girls: a controlled clinical trial of treatment by diet, behavior modification, and parental support. Pediatrics. 1990;85(3):345-352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weintraub DL, Tirumalai EC, Haydel KF, Fujimoto M, Fulton JE, Robinson TN. Team sports for overweight children: the Stanford Sports to Prevent Obesity Randomized Trial (SPORT). Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(3):232-237. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daley AJ, Copeland RJ, Wright NP, Roalfe A, Wales JK. Exercise therapy as a treatment for psychopathologic conditions in obese and morbidly obese adolescents: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):2126-2134. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fenner AA, Howie EK, Davis MC, Straker LM. Relationships between psychosocial outcomes in adolescents who are obese and their parents during a multi-disciplinary family-based healthy lifestyle intervention: one-year follow-up of a waitlist controlled trial (Curtin University’s Activity, Food and Attitudes Program). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0501-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kerkar N, D’Urso C, Van Nostrand K, et al. Psychosocial outcomes for children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease over time and compared with obese controls. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56(1):77-82. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31826f2b8c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luca P, Dettmer E, Khoury M, et al. Adolescents with severe obesity: outcomes of participation in an intensive obesity management programme. Pediatr Obes. 2015;10(4):275-282. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moon YI, Park HR, Koo HY, Kim HS. Effects of behavior modification on body image, depression and body fat in obese Korean elementary school children. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45(1):61-67. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2004.45.1.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Panagiotopoulos C, Ronsley R, Al-Dubayee M, et al. The centre for healthy weights: shapedown BC: a family-centered, multidisciplinary program that reduces weight gain in obese children over the short-term. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(12):4662-4678. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8124662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stella SG, Vilar AP, Lacroix C, et al. Effects of type of physical exercise and leisure activities on the depression scores of obese Brazilian adolescent girls. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2005;38(11):1683-1689. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2005001100017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nobles J, Radley D, Dimitri P, Sharman K. Psychosocial interventions in the treatment of severe adolescent obesity: The SHINE program. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(5):523-529. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4(6):561-571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Beck A, Steer R. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory San Antonio. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beck J, Beck A, Beck J. Youth Inventories for Children and Adolescents: Manual. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavior Assessment System for Children, (BASC-2) Handout. Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing; 2004:55014-51796. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Terry PC, Lane AM, Lane HJ, Keohane L. Development and validation of a mood measure for adolescents. J Sports Sci. 1999;17(11):861-872. doi: 10.1080/026404199365425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Faulstich ME, Carey MP, Ruggiero L, Enyart P, Gresham F. Assessment of depression in childhood and adolescence: an evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC). Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(8):1024-1027. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.8.1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory: Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression, Inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985;21(4):995-998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Psychology Foundation of A. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. 2nd ed Sydney, Australia: Psychology Foundation of Australia; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Steinsmeier-Pelster J, Schürmann M, Duda K. Depressions-Inventar für Kinder und Jugendliche (DIKJ): Handanweisung. Göttingen, Bern, Toronto, Seattle: Hogrefe-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Birleson P, Hudson I, Buchanan DG, Wolff S. Clinical evaluation of a self-rating scale for depressive disorder in childhood (Depression Self-Rating Scale). J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1987;28(1):43-60. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1987.tb00651.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hien D, Matzner F, First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-child edition (version 1.0). New York, NY: Columbia University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(4):554-565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Richardson LP, McCauley E, Grossman DC, et al. Evaluation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Item for detecting major depression among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):1117-1123. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. Revised children’s manifest anxiety scale. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. doi: 10.1515/9781400876136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Costello EJ, Angold A. Scales to assess child and adolescent depression: checklists, screens, and nets. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27(6):726-737. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198811000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Spielberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Self-Evaluation Questionnare). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychogyists Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Spielberger CD, Edwards CD. STAIC Preliminary Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (“How I Feel Questionnaire”). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jebeile H, Gow ML, Baur LA, Garnett SP, Paxton SJ, Lister NB. Treatment of obesity, with a dietary component, and eating disorder risk in children and adolescents: A systematic review with meta-analysis [published online May 26, 2019]. Obes Rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rawana JS, Morgan AS. Trajectories of depressive symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood: the role of self-esteem and body-related predictors. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43(4):597-611. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9995-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Natsuaki MN, Biehl MC, Ge X. Trajectories of depressed mood from early adolescence to young adulthood: the effects of pubertal timing and adolescent dating. J Res Adolesc. 2009;19(1):47-74. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00581.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stice E, Shaw H, Bohon C, Marti CN, Rohde P. A meta-analytic review of depression prevention programs for children and adolescents: factors that predict magnitude of intervention effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(3):486-503. doi: 10.1037/a0015168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Field AE, Austin SB, Taylor CB, et al. Relation between dieting and weight change among preadolescents and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):900-906. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Khalid S, Williams CM, Reynolds SA. Is there an association between diet and depression in children and adolescents? a systematic review. Br J Nutr. 2016;116(12):2097-2108. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516004359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Oddy WH, Allen KL, Trapp GSA, et al. Dietary patterns, body mass index and inflammation: pathways to depression and mental health problems in adolescents. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;69:428-439. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Galland L. Diet and inflammation. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25(6):634-640. doi: 10.1177/0884533610385703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fisak BJ Jr, Richard D, Mann A. The prevention of child and adolescent anxiety: a meta-analytic review. Prev Sci. 2011;12(3):255-268. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0210-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Korczak DJ, Madigan S, Colasanto M. Children’s physical activity and depression: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):e20162266. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Search strategy used on the Ovid platform with the Medline database

eTable 2. Characteristics of included studies

eFigure 1. Meta-regression of the effect size for change in symptoms of depression between pre- and post-intervention and mean participant BMI z-score at baseline following professionally administered obesity treatment with a dietary component in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity (R2=0.18, p=0.02)

eFigure 2. Meta-regression of the effect size for change in symptoms of anxiety between pre- and post-intervention and intervention duration following professionally administered obesity treatment with a dietary component in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity (R2=0.82, p<0.001)

eFigure 3. Meta-analysis of the change in weight-related outcomes between pre- and post-intervention (A) and between baseline and the latest follow-up timepoint (B), following obesity treatment with a dietary component in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity

eReferences.