ABSTRACT

Background

The frequency and presentation of each of the most common forms of spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) varies widely. In the case of the Americas, this diversity is particularly dynamic given additional social, demographic, and cultural characteristics.

Objective

To describe the regional prevalence and clinical phenotypes of SCAs throughout the continent.

Methods

A literature search was performed in both MEDLINE and LILACS databases. The research was broadened to include the screening of reference lists of systematic review articles for additional studies. Investigations dating from the earliest available through 2019. Only studies in English, Portuguese, and Spanish were included. We analyzed publications with genetically confirmed cases only, ranging from robust samples with epidemiological data to case reports and case series from each country or regions.

Results

Overall, SCA3 is the most common form in the continent. Region‐specific prevalence and ranking of the common forms vary. On the other hand, region‐specific phenotypic variations were not consistently found based on the available literature analyzed, with the exception of the absence of epilepsy in SCA10 consistently described in a particular cluster of cases in South Brazil.

Conclusion

Systematic, multinational studies analyzing in detail the true frequencies of SCAs across the Americas as well as distinct clinical signs and clues of each form would be ideal to look for these potential variations.

Keywords: spinocerebellar ataxias, SCAs, autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias, hereditary ataxias

Spinocerebellar ataxias (SCAs) represent a clinically heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by autosomal dominant degeneration and dysfunction of the cerebellum and its afferent and efferent connections.1 Despite their heterogeneity, some SCAs can be grouped according to a common molecular pathological mechanism, for example, expansion of polyglutamine encoding CAG repeats within their respective genes, expansion of intronic repeats, or molecular changes in other noncoding regions.2, 3 From a clinical perspective, SCAs present with a variable combination of cerebellar ataxia syndrome features.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 In addition, patients with SCAs can present with extracerebellar motor and nonmotor symptoms and signs, such as movement disorders, ocular dysfunctions, pyramidal tract signs, peripheral neuropathy, cognitive dysfunction, seizures, sleep disorders, olfactory loss, dysautonomia, and mood disorders.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Finally, systemic findings may be part of the phenotype of certain SCAs.6, 11

The worldwide prevalence of SCAs is in the range of 4/100.000 (from 2/100.000 to 43/100.000).1, 2, 12 To date, more than 40 SCA subtypes have been characterized (Table 1); however, the prevalence of specific subtypes depends on ethnic and geographical variables. A review published 15 years ago by Schöls and colleagues3 showed that despite 30% of SCAs remaining undiagnosed at the time, SCA3 was the most common form worldwide, representing 21% of all SCAs, followed by SCA2 and SCA6 (15% each), SCA1 (6%), SCA7 (5%), and SCA8 (3%), whereas SCA10, 12, 14, 17, and dentatorubro‐pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA) were considered exceedingly rare. Although rare, SCA10 proved to be one of the most common in certain geographic areas such as Peru, Mexico, and Brazil.12

Table 1.

SCAs–summary of genetic characteristics

| SCA | Locus | Gene | Mutation (Expansion) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCA1 | 6p22‐23 | ATXN1 | CAG |

| SCA2 | 12q23‐24.1 | ATXN2 | CAG |

| SCA3 | 14q32.1 | ATXN3 | CAG |

| SCA4 | 16q22.1 | SCA4 | – |

| SCA5 | 11q13.2 | SPTBN2 | – |

| SCA6 | 19p13 | CACNA1A | CAG |

| SCA7 | 3p21.1‐p12 | ATXN7 | CAG |

| SCA8 | 13q21 | ATXN80S | CAG/CTG |

| SCA10 | 22q13.31 | ATXN10 | ATTCT |

| SCA11 | 15q15.2 | TTBK2 | – |

| SCA12 | 5q32 | PPP2R2B | CAG |

| SCA13 | 19q13.33 | KCNC3 | – |

| SCA14 | 19q13.4 | PRKCG | – |

| SCA15 | 3p26.1 | ITPR1 | Allelic to SCAs 16, 29 |

| SCA16 | 3p26.1 | ITPR1 | Allelic to SCAs 15, 29 |

| SCA17 | 6q27 | TBP | CAG |

| SCA18 | 7q22‐q32 | IFRD1 | – |

| SCA19 | 1p13.2 | KCND3 | Allelic to SCA22 |

| SCA20 | 11p11.2‐q13.3 | SCA20 | Multiple gene duplication |

| SCA21 | 7p21.3‐p15.1 | SCA21 | – |

| SCA22 | 1p13.2 | KCND3 | Allelic to SCA19 |

| SCA23 | 20p13 | PDYN | – |

| SCA24 | – | – | – |

| SCA25 | 2p21‐p15 | SCA25 | – |

| SCA26 | 19p13.3 | EEEF2 | – |

| SCA27 | 13q34 | FGF14 | – |

| SCA28 | 18p11 | AFG3L2 | – |

| SCA29 | 3p26.1 | ITPR1 | Allelic to SCAs 15, 16 |

| SCA30 | 4q34.3‐q35.1 | SCA30 | – |

| SCA31 | 16q22 | SCA31 | TGGAA |

| SCA32 | 7q32‐q33 | SCA32 | – |

| SCA33 | – | – | – |

| SCA34 | 6q12.3‐q16.1 | ELOVL4 | – |

| SCA35 | 2Op13 | TGM6 | – |

| SCA36 | 20p13 | NOP36 | GGCCTG |

| SCA37 | 1p32 | SCA37 | – |

| SCA38 | 6p12.1 | ELOVLE5 | – |

| SCA39 | – | – | – |

| SCA40 | 14q32 | CCDC88C | – |

| SCA41 | 4q27 | TRPC3 | – |

| SCA42 | 17q21.33 | CACNA1G | – |

| SCA43 | 3q25.2 | MME | – |

| SCA44 | 6q24.3 | GRM1 | – |

| SCA45 | 5p33.1 | FAT2 | – |

| SCA46 | 19q13.2 | PLD3 | – |

| SCA47 | 1p35.2 | PUM1 | – |

| SCA48 | 16p13.3 | STUB1 | – |

| DRPLA | 12p13.31 | ATN1 | CAG |

SCA, spinocerebellar ataxia; DRPLA, dentatorubro‐pallidoluysian atrophy.

The Americas represent a unique continent with regard to its ethnic, social, demographic, and cultural diversity, with peculiar regional traits observed from the Alaska North Slope to Patagonia. The first humans in the continent, who crossed the Bering Strait from Asia in the Ice Age giving birth to the Amerindians, were later joined by the Vikings in Greenland and Atlantic Northeast, followed by the European settlers and later the Africans and European‐Arabian‐Asian immigrants (Table 2). The result is a melting pot, forming a diverse genetic landscape.13 This, among other factors, may play an important role and influence in the wide range of epidemiological and phenotypic diversity emerging from studies showing population‐specific and region‐specific aspects of SCAs in the continent. Recognizing that several questions remain unanswered on this topic, the aim of this study is to review the available published data and expert opinion on the geographic and phenotypic diversity of SCAs in the Americas.

Table 2.

Main ethnic origins of the countries with the highest number of patients with spinocerebellar ataxias

| Regions and Countries | Main Ethnic Origins |

|---|---|

| North America | |

| Canada | European: British, French, Irish, German, Italian, Slav, Dutch Native American Indian and Inuit Asian: Indian, Chinese, Philippian, Jew |

| United States | European: British, Irish, German, Italian, French, Dutch, Slav, Scandinavian African Native American Indian Asian: Chinese, Indian, Philippian, Jew |

| Mexico | Native American Indian European: Spanish, British, Irish, Italian, German, French, Dutch Asian: Arabian, Chinese, Korean, Jew |

| Central America | |

| Cuba | African European: Spanish, French, Portuguese, Italian, Slav, Dutch, Greek Native American Indian Asian: Chinese, Japanese |

| South America | |

| Venezuela | European: Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, German Native American Indian African |

| Colombia | European: Spanish, Italian, German Native American Indian African Asian: Arabian, Chinese, Japanese, Jew |

| Peru | Native American Indian European Spanish, Austrian, British, French, German, Croatian Asian: Chinese, Japanese, Arabian African |

| Chile | European: Spanish, German, Croatian, Greek Native American Indian Asian: Arabian, Chinese, Japanese |

| Argentina | European: Spanish, Italian, German, Slav, French Native American Indian Asian: Arabian, Jew |

| Brazil | European: Portuguese, German, Italian, Spanish, Slav, Dutch African Native American Indian Asian: Arabian, Japanese, Chinese, Jew |

Methods

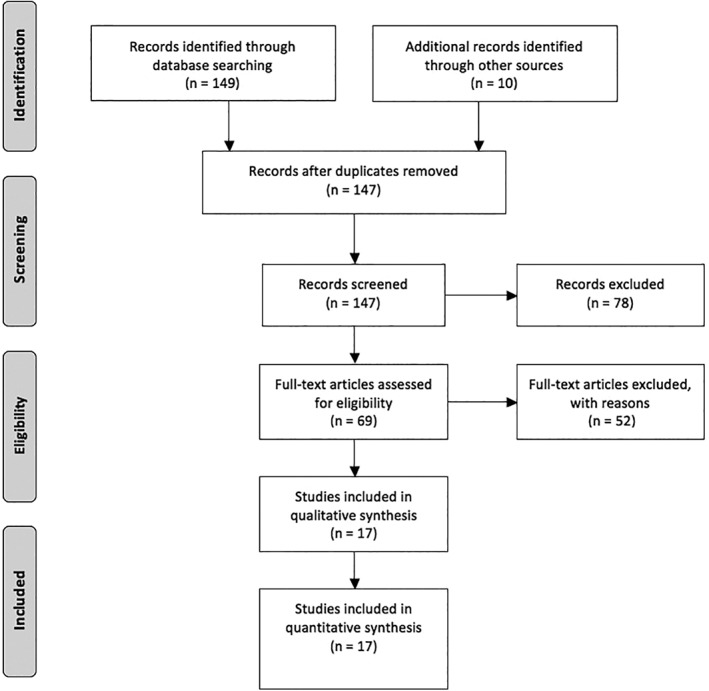

A literature search was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses guidelines in both MEDLINE and LILACS databases using “spinocerebellar ataxia,” “ataxia,” or specific SCA subtypes as search terms along with “epidemiology” and with the geographic designations “North America,” “Central America,” “Caribbean,” “South America,” and the individual names of all countries of the American continent in the medical subject headings, title, abstract, or author‐supplied keywords. The research was broadened to include screening of reference lists of systematic review articles for additional studies initially missed or presented only in abstract form. No restrictions were predetermined on the year of the study, with investigations dating from earliest available through 2019. Only studies in English, Portuguese, and Spanish were included. We analyzed publications with genetically confirmed cases only, ranging from robust samples with epidemiological data to case reports and case series from each country or regions. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram for inclusion of articles.14

Figure 1.

Inclusion of articles by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses 2009 flow diagram.14

Results

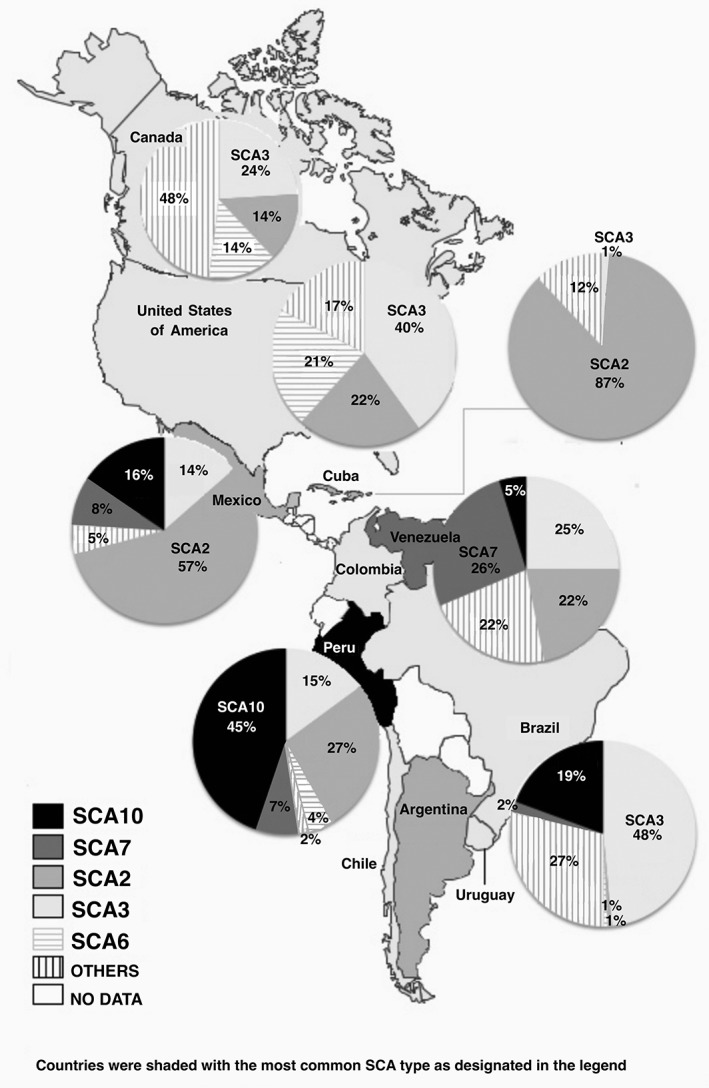

An overall assessment of the frequency of SCAs in North, Central, and South America shows that the most common subtype is SCA3, followed by SCA2, 10, and 7 (Fig. 2). SCAs subtypes 1 and 6 were generally less prevalent.2, 12

Figure 2.

Most frequent SCAs in the Americas. Drawn from data in Table 3 by one of the authors (C.H.F.C.). SCA, spinocerebellar ataxia.

The results for each individual country are described in the following sections (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of SCA in the Americas—main studies

| Country/Year | Patients (n) | Most common SCA | Other SCAs | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | ||||

| Canada, 2005 | 69 | SCA3 | SCAs 2, 6, 1, and 8 | Kraft et al15 |

| United States (Minnesota), 1998 | 178 | SCA3 | SCAs 2, 6, 1, and 7 | Moseley et al16 |

| United States, 2013 | 345 | SCA3 | SCAs 2, 6, and 1 | Ashizawa et al17 |

| 123 | SCA2 | SCAs 10, 3, 7, and 17 | Alonso et al25 | |

| Mexico (Gulf Coast), 2014 | 64 | SCA7 | SCA2 | Magaña et al27 |

| Central America | ||||

| Cuba, 2009 | 753 | SCA2 | SCAs 3 and 1 | Velázquez‐Pérez et al28 |

| South America | ||||

| Argentina, 2015 | 19 | SCA2 | SCAs 3, 1, 6, and 7 | Rodriguez‐Quiroga et al59 |

| Brazil, 1997 | 328 | SCA3 | SCAs 2 and 1 | Lopes‐Cendes et al50 |

| Brazil (South), 2006 | 66 | SCA3 | SCAs 7 | Jardim et al51 |

| Brazil (South), 2012 | 150 | SCA3 | SCAs 10, 2, 7, 1, and 6 | Teive et al52 |

| Brazil, 2014 | 544 | SCA3 | SCAs 2, 7, 1, 10, and 6 | de Castilhos et al55 |

| Brazil (Sao Paulo state), 2014 | 320 | SCA3 | SCAs 7, 1, 2, 6, 8, and 10 | Cintra et al54 |

| Brazil (South), 2018 | 460 | SCA3 | SCAs 10, 2, 7,1, and 6 | Camargo et al (personal communication) |

| Chile, 2015 | 50 | SCA3 | Not reported | Miranda47 |

| Chile, 2018 | 63 | SCA3 | Not reported | Saffie Awad et al48 |

| Peru, 2018 | 258 | SCA10 | SCAs 2, 3, 7, 6, and 1 | Cornejo‐Olivas et al (personal communication) |

| Venezuela, 2016 | 115 | SCA7 | SCAs 3, 2, 1, 10, and DRPLA | Paradisi et al37 |

SCA, spinocerebellar ataxia; DRPLA, dentatorubro‐pallidoluysian atrophy.

North America

In Canada, only 1 clinical study, a single‐center retrospective chart review with a total of 21 SCA families, was found in the literature.15 The study showed that SCA3, found in 23.8% of the families, was the most common molecular diagnosis, followed by SCA2 (14.3%) and SCA6 (9.5%), whereas SCA1 and SCA8 were identified in 1 family (4.8%) each. In terms of clinical profile, the presentations of the core features described in the study are typical, although more subtle details (ie, bulging eyes in SCA3) are not presented for comparison. Recently, ataxia with erythrokeratodermia as a result of ELOVL4 gene mutations (SCA34) was primarily described and characterized in a large French–Canadian family.11

In the United States, a study of 109 SCA cases with confirmed genetic diagnoses published more than 20 years ago found that the most common subtype was SCA3 detected in 33.9%, followed by both SCA2 and SCA6 in 24.8%, then SCA1 in 9.2%, and SCA7 in 7.3%.16 Similar figures were confirmed later in a broader 12‐center study of 345 patients in which SCA3 accounted for 40%, followed by SCA2 in 21.7%, SCA6 in 21%, and SCA1 in 17.4%.17 This study was able to perform an assessment of the phenotypes and rates of longitudinal progression, comparing their data with those from an earlier methodologically similar European study, finding no significant difference for any of the subtypes and variables. Despite the relatively large number of Americans who are Mexican immigrants or of Mexican heritage, SCA10 has only been rarely described in the United States, and its prevalence remains unknown. Case reports describe cases of Mexican Americans presenting seizures as part of their phenotype, but also a patient of Sioux Native American ancestry in whom no seizure was documented.18, 19 Still in the United States, SCA13 and SCA36 were tested in large samples of patients with undiagnosed sporadic or familial cerebellar ataxia, identifying 4 positive families each (<1%) from 2 distinct ethnic groups: white European and Asian (Japanese and Vietnamese).20, 21 SCA14, SCA18, and SCA20 have been described in single families.22, 23, 24

In Mexico, the largest published study analyzed SCA1–3, 6–8, 10, 12, and 17 and DRPLA on a total of 682 individuals, 559 of them belonging to 108 autosomal dominant families and 123 sporadic cases in which Friedreich's ataxia or a secondary cause were excluded.25 All cases were Mestizos, born in Mexico, as well as their parents and grandparents. The most frequent molecular diagnosis was SCA2 (45.4%), followed by SCA10 (13.9%), SCA3 (12%), SCA7 (7.4%), and SCA17 (2.8%). No cases of SCA6, 8, or 12 or DRPLA were found. In terms of clinical profile, although most of the SCAs were found to be rather typical, it is important to highlight the fact that SCA10 was originally described in Mexico with a phenotype of pure cerebellar ataxia and seizures, occasionally added by mild pyramidal and neuropsychiatric signs.26 A case‐finding study restricted to the genetic analysis of SCA1, 2, 3, 6, and 7 in 5 communities of Veracruz State identified 64 SCA cases from 10 families, most of them (8 families, 55 individuals) with SCA7 in addition to 2 families with SCA2, but none with the other forms tested.27

Central America

Our review did not find any publications, including case reports, describing SCAs in continental Central America: Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama.

In insular Central America, literature is also sparse, except for Cuba where the SCAs, particularly SCA2, have been well studied. These studies include a nationwide epidemiological survey for SCAs showing that SCA2 represents 86.8% of all SCAs, followed by SCA3 in 4.1% and rare (<1%) cases of SCA7 and SCA1.28, 29 The molecular, pathologic, and phenotypic profiles of the Cuban SCA2 patients have been thoroughly explored and are consistent with the typical presentation and longitudinal progression described elsewhere. In the case of SCA3, the subphenotype III with peripheral signs seems to be more common than previously reported in other series.29

A total of 3 unrelated SCA2 families were described in Martinique (French West Indies) in 2 publications by the same group, outlining typical features (ataxia, supranuclear ophthalmoplegia, and hyporeflexia) but also intrafamilial phenotypic heterogeneity.30, 31 Recently, a large family from Antigua with SCA3 was well documented, including affected individuals who moved to Barbados and Trinidad‐Tobago.32 Gwinn‐Hardy and colleagues33 also described an Antiguan SCA3 family of sub‐Saharan African descent, whereas Giunti and colleagues34 described SCA3 families from Jamaica living in the United Kingdom.

South America

Ecuador, Paraguay, Uruguay, Suriname, and Guyana have no published cases of SCAs. One SCA3 family from French Guiana was described as part of a large worldwide study. In this case, the disease was probably the result of independent mutation based on the presence of a unique intragenic haplotype not found in other populations.35 Similarly, only 1 reference was found in the literature describing SCAs in Bolivia, a unique report of a family with 3 ataxic patients, all with SCA10 mutations, and 2 of them also presenting molecular diagnosis of SCA2. Of the SCA10 cases, 2 had epilepsy, and both affected by SCA2 had supranuclear ophthalmoplegia.36

In Venezuela, a nationwide study found 115 unrelated SCA families. SCA7 was the most frequent subtype (26.6%), followed by SCA3 (25%), SCA2 (21.9%), SCA1 (17.2%), SCA10 (4.7%), and DRPLA (3.1%); no cases of SCA6, 8, or 17 were found, and in 43% of the families, a specific diagnosis was not identified.37 SCA7 mutations displayed strong geographic aggregation in 2 independent founder foci, and SCA1 showed a very remote founder effect for a subset of families. Most of the SCA10 present seizures similar to cases initially described in Mexico.

In Colombia, no systematic SCA study was found. An early retrospective study of 38 patients with “inherited ataxias” did not find cases of dominant inheritance or diagnoses of any form of SCAs.38 However, a unique SCA10 case of an adopted Colombian patient of mixed Amerindian (mother)/white European Australian descent presenting initially with epilepsy and ataxia has been described.39 This case later developed chorea and had a concomitant molecular diagnosis of Huntington's disease. Also, 2 adopted Colombian brothers diagnosed with SCA21 have recently been reported, presenting with a complex combination of ataxia, postural tremor, parkinsonism, myoclonus, motor and mental development delay, behavioral abnormalities, and early‐onset cataracts, broadening the clinical spectrum of this disorder previously only described in European and Asian families.40 As in Colombia, there are no studies on the prevalence of SCAs in the population of Uruguay. Despite this, it is believed that the most common SCA in both countries is SCA3 in view of unpublished data from specialized outpatient clinics (personal communication).

In Peru, information on specific forms of SCAs and their prevalence is becoming more appreciable during the past years. SCA10 seems to be the most frequent form, occurring in more than 20% of cases,41, 42 followed by either SCA2, detected in 7.8% of a sample of 231 cases, or SCA3, diagnosed in 9.7% of a smaller sample of 31 patients with dominant ataxias.43 The cases of SCA2 present with features common to what has been described worldwide; however, the SCA10 cases present much less frequently with epilepsy (if compared with Mexican cases), and no evidence of peripheral neuropathy (similar to Brazilian patients).43, 44 SCA7 and SCA6 have been described in 2 Peruvian kindreds each; SCA1 has been described in 1 family; all presenting phenotypes consistent with what has been described in the literature.44, 45 One Peruvian SCA10 family of Amerindian ancestry living in Italy presenting with ataxia and epilepsy was described in 2014.46

A total of 2 studies in preparation have also looked at nonpathogenic large normal alleles in ATXN1, ATXN3, CACNA1A, and ATXN10, a factor associated with disease prevalence in SCAs1, 3, 6, and 10 among healthy mestizo Peruvians. These studies, however, did not confirm the hypothesis of an association of the frequency of these diseases with mutation‐prone alleles (personal communication).

In Chile, 2 retrospective studies with limited data are available. The first was published in 2015, describing 50 patients with “inherited ataxias,” 10 (20%) of them with a molecular diagnosis of SCA3 belonging to 5 different families; no details of the diagnoses on the remaining cases are presented.47 Another more recent retrospective study of 22 patients presenting with “genetic ataxias” identified 14 with a molecular diagnosis of SCA3, and the remaining presenting recessive or X‐linked forms.48 One case of SCA1 has also been reported as an abstract.49

In Brazil, the most common forms of SCAs have been described in detail. However, because of the significant differences in terms of ethnic background from 1 state to another and even within the same state, the frequencies of each form cannot be generalized. For example, the first study that performed a genetic analysis of SCAs in Brazil was published in 1997 and was restricted to SCA1, SCA2, SCA3, and DRPLA, including 328 patients from the Southern states, finding mutations in 39%: SCA3 in 30% of them, followed by SCA2 in 9%, and SCA1 in 6%.50 Another early study including 66 patients from the Southern state of Rio Grande do Sul found an overwhelming frequency of SCA3 (92%), followed by SCA7 in 2%. One single case of SCA8 was found, and only 6% remained undiagnosed. The authors attribute the high prevalence of SCA3 to a probable Azorean founder effect.51 Still in South Brazil, a study based on a tertiary center in the state of Parana analyzed a total of 150 patients from 104 families with SCAs.52 This study confirmed that SCA3 was the most prevalent type (72.46%), but in this population, SCA10 represented the second most common form (11.60%), followed by SCA2 (7.25%), SCA7 (4.34%), SCA1 (2.90%), and SCA6 (1.45%). No cases were positive for SCA8, SCA12, SCA17, or DRPLA. Interestingly, this study and another by the same group created the notion that the Brazilian form of SCA10 did not typically present with seizures, as opposed to Mexican SCA10 cases.52, 53 A study from Ribeirão Preto, state São Paulo with 320 patients with dominant ataxias found a molecular diagnosis in 265 (82.8%) belonging to 131 unrelated families.54 SCA3 was by far the most common (70.7%), followed by SCA7 (6%), SCA1 (5.3%), SCA2 (2.7%), SCA6 (1.3%), SCA8 (0.7%), and SCA10 (0.7%). No cases of SCA12, SCA17, or DRPLA were found.53 The largest Brazilian study published so far included 544 SCA patients from 359 families from 11 tertiary urban centers from the South, Southeast, North, and Northeast states.55 Overall, SCA3 was the most common form, accounting for 59.6% of the whole sample, followed by SCA2 in 7.8%, SCA7 in 5.6%, SCA1 in 4.2%, SCA10 in 3.3% and SCA6 in 1.4%. Regional differences were evident; for example, SCA7 was the second most common in parts of the Southeast, whereas Sao Paulo had the highest prevalence of SCA2 and all cases of SCA6. Although the clinical and genotypic markers of these disorders were, for the most part, consistent with what was described elsewhere in the world, 1 striking exception was the fact that seizures were actually part of the phenotype among the SCA10 families, similar to what was described among Mexican cases.55 Finally, in a large sample of 167 SCA3 patients belonging to 68 pedigrees, Moro and colleagues7 studied the frequencies of SCA3 subphenotypes. Subphenotype 2 was the most common, with ataxia and pyramidal findings (67.5%), followed by subphenotype 3 with ataxia and peripheral signs (13.3%), and subphenotype 6 with pure cerebellar syndrome in 7.2%.7 Only 1 family with DRPLA has been reported in Brazil, among 487 patients with autosomal dominant ataxias (0.2%).56 This family had 6 affected members, all with late‐onset ataxia and associated with dementia in 2. A DRPLA case of Japanese ancestry has been confirmed in a report currently submitted for publication by our group. Finally, a family with SCA31 and a sporadic case of SCA34 with erythrokeratodermia were published recently.57, 58

In Argentina, a prospective study based on a center of neurogenetics found a total of 20 cases of SCAs, including 8 (40%) with SCA2, followed by SCA1 and SCA3, both with 5 cases each (20%), and the remaining being 1 case of SCA6 and 1 case of SCA7.59 SCA10 has also been described in an Argentinean family presenting a phenotype similar to that described in Mexicans60 (Table 2).

Discussion

Several assumptions can be made in view of the data presented in this review. The high frequency of SCA7 in the Mexican State of Veracruz and in Venezuela, both close to Caribbean, is quite intriguing because the disease is more commonly found in patients from countries such as Finland, Sweden, the Netherlands, and South Africa.27, 37 The Mexican cluster could be explained by the fact that the Mexican communities analyzed, founded by Spanish landowners and populated by Native Americans, were settled in a region in which the geography may have undermined communication with other populations and limited human migration. Of importance, the phenotype of the large group of SCA7 cases described in this study is quite typical when compared with other cases with this diagnosis elsewhere. Thus, it is likely that an ancestral mutation spread over the communities of Veracruz because of their geographical isolation as well as cultural habits, such as consanguineous marriages.27 In other words, a cluster of SCA7 patients as the result of a founder effect. In the case of Venezuelan families, 1 study showed that the mutations presented a strong geographic aggregation in 2 separate founder foci, but their correlation with the haplotype described in other populations, particularly the Mexican, has not been determined so far.37 Interestingly, SCA7 has been described with relatively high prevalence in the state of Ceara, Northeastern Brazil, also near the Caribbean.57

The highest prevalence of SCA2 worldwide is in the province of Holguin, Cuba, particularly in the municipality of Baguanos, also the place where the first description was performed.28 The majority of these cases are of Spanish Caucasian ancestry, consistent with the fact that SCA2 tends to be more prevalent among a few countries colonized by the Spanish throughout the Americas. On the other hand, an independent founder effect cannot be ruled out as Cubans also have the highest worldwide prevalence of what is designated “large normal SCA2 alleles,” a well‐defined factor linked to the expansion of CAG repeats and a higher prevalence of SCA2.61

The fact that pathogenic expansions of the SCA6 locus are associated with a common CACNA1A haplotype worldwide may indicate that cases of SCA6 across the globe are indeed eventually linked to a common founder in Japan. North and Latin America have the largest Japanese community outside Japan, especially in the United States, Brazil, Peru, and Mexico.62 Accordingly, Canada, the United States, Brazil, and Peru have documented cases of SCA6, as outlined previously in this review.15, 17, 55 In Brazil, cases are concentrated in the states of Parana and Sao Paulo, the 2 areas that received more dense immigration from the Japanese at the turn of the 20th century.55, 63

In the case of SCA3, the ancestral origin and spreading routes of mutational events were relatively well delineated using haplotype studies. As such, 2 independent de novo mutations have been identified, generating lineages with implications to the population of the Americas.64 The most ancient (Joseph lineage) first occurred in Asia around 7000 years ago, diffused throughout Europe much later, leading to founder effects in the Azorean island of Sao Miguel and Portugal's Northeastern mainland. The second, the Machado lineage, probably originated in the Island of Sao Miguel and along the Tagus river valley in the heart of the mainland about 1500 years ago. Worldwide, most affected families share the intragenic haplotypes of 1 of these lineages: Machado lineage dispersed almost exclusively by Portuguese emigration, whereas the Joseph lineage dispersed to additional parts of the world before the Portuguese founder effect occurred (Asia, Oceania, East Europe, etc.).64 On the other hand, both lineages converge in the Americas, more so, obviously, throughout Brazil with a particular high frequency in the coastal cities of the Santa Catarina state in the south. This area received a large wave of Portuguese immigrants during the middle of the 18th century, coming specifically from the islands of Madeira and Azores because of the serious economic difficulties and constant seismic activity.65

In theory, the presence of different lineages or the occurrence of SCA3 clusters in specific geographic areas could lead to different proportions of SCA3 subphenotypes or a more random presence of phenotypic variability in certain areas of the globe. Although the distribution of subphenotypes has not been consistently compared between different SCA3 populations, a cursory look at the most important studies of larger SCA3 samples does not reveal any major discrepancy, except for the proportionately higher frequency of subphenotype III among Cubans described in 1 study.7, 29 Other phenotypic variables, however, may present with different frequencies in different populations. One such example is the presence of “bulging eyes” (BE; Fig. 3). Although a single‐center study of 167 SCA3 from Brazil, most of the participants from the Santa Catarina state with families who originated from the Azorean island of São Miguel, found that almost two thirds had BE,10 other Brazilian studies with different populations of SCA3 found much lower frequencies, ranging from 27% to 30%,51, 55 figures similar to those described in Portugual.66 Interestingly, BE seems to be unusual among samples from countries such as Germany and France.67, 68

Figure 3.

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3–“bulging eyes.” From a personal collection (H.T.), with appropriate approvals.

SCA10 may be the 1 form of SCAs primarily originated in the Americas. Almeida and colleagues69 were the first to perform a detailed haplotype study in Brazilian and Mexican families showing several evidences of an ancestral common origin for SCA10 in Latin America, probably from an ancestral Amerindian population. Later, however, single families from China and Japan were identified, indicating that the original mutation may have occurred before the migration of Amerindians from East Asia to North America.70 Screenings for SCA10 among other populations are so far negative.

SCA10 was first described in 1998, and ensuing studies confirmed a phenotype combining ataxia and epilepsy.71, 72 The first Brazilian description done by our group, however, did not detect epilepsy as part of the clinical presentation, a finding that was later confirmed on a different study.53, 73 The later study found a 3.75% prevalence of epilepsy among this cluster of Southern Brazilian SCA10 cases,53 differing from patients from Mexico (72.2%), Argentina (100%), Venezuela (80%), and even among other regions of Brazil (65%).55, 74 Peruvian cases seem to present with epilepsy much less frequently, but the exact frequency is part of data currently been organized for publication (personal communication). So far, several potential variables that could influence this phenotypic discrepancy have been studied and proved to be irrelevant, including age, age of onset, and size of the pathogenic ATTCT expansion.74 One exception is the presence of a penta or heptanucleotide interruption motif, designated “ATCCT interruption” found within the SCA10 ATTCT expansions. So far, the most consistent study on this specific issue showed that cases with more “pure” expanded repeat mutations (ATCCT negative) had a lower likelihood for the development of seizures, whereas the ATCCT‐positive patients had a 6.3‐fold increased risk of presenting seizures and a 13.7‐fold greater chance of seizures within their first‐degree relatives.75

Conclusion

The heterogeneous and mixed ethnic background characteristic of the Americas is not the only challenge for a review of any topic related to genetic disorders in the continent. In addition to the existence of several geographically circumscribed clusters of specific SCA subtypes and founder effects, access to tertiary medical centers, genetic testing, dedicated specialists, and means to disseminate scientific data can markedly differ among neighboring areas in the subcontinent or even within the same country. As a result, several countries have no or poorly detailed published data related to this topic, a problem that is not exclusive to the least scientific or economically developed.

Despite these limitations, it seems evident that SCA3 is the most common form in the continent overall, although country‐specific prevalence and ranking of the common forms vary. Notable examples are the following: (1) SCA2, the most common form in Cuba and Mexico, whereas it is the second most common in Canada, the United States, Peru, Venezuela, and Brazil; (2) SCA10 is the most common SCA in Peru, the second most common subtype in Mexico, and part of Southern Brazil; (3) SCA7 seems to be the most common form in Venezuela.

In addition to guiding differential diagnosis and molecular testing by ranking the most common forms of SCAs in different parts of the continent, the other main objective of this review was to identify region‐specific phenotypic variations. To be noteworthy, these variations should be unique or at least peculiar, in contrast to the classic description, as consequences of molecular or, less commonly, environmental modifiers. Unfortunately, with the exception of what was already discussed with regard to the presence or absence of epilepsy in SCA10, no other evident differences could be observed for other forms of SCA based on the available literature. A systematic, multinational study analyzing in detail the discerning clinical signs and clues of each form (bulging eyes, other movement disorders, oculomotor abnormalities, etc.) would be ideal to look for these potential variations.

Author Roles

1. Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution. 2. Manuscript preparation: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and Critique

H.A.G.T.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A

A.T.M.: 1C, 2A

C.H.F.C.: 1A, 1C, 2B

R.P.M.: 1B, 2A, 2B

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement: The authors confirm that the approval of an institutional review board is not necessary for this review paper. The authors confirm that the patient consent to disclosure of his picture (Figure 3) was acquired. There was no human or animal research in this review study. Informed consent was not necessary. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: No specific funding was received for this work, and the authors declare that there is no conflict of interest to report.

Financial Disclosures of All Authors (for the Preceding 12 Months): No authors have received any funding from any institution, including personal relationships, interests, grants, employment, affiliations, patents, inventions, honoraria, consultancies, royalties, stock options/ownership, or expert testimony for the last 12 months.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ashizawa, Dr. Sheng‐Han, and Dr. Paulson from the United States; Dr. Rodriguez‐Violante from Mexico; Dr. Cornejo‐Olivas from Peru; Dr. Gatto, Dr. Arakaki, and Dr. Merello from Argentina; Dr. Bernal and Dr. Orozco from Colombia; Dr. Sommaruga from Uruguay; Dr. Miranda and Dr. Chaná‐Cuevas from Chile; and all the Brazilian researchers of ataxia.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Teive HAG, Ashizawa T. Primary and secondary ataxias. Curr Opin Neurol 2015;28:413–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hersheson J, Haworth A, Houlden H. The inherited ataxias: genetic heterogeneity, mutation databases and future directions in research and clinical diagnostics. Hum Mutat 2012;33:1324–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schöls L, Bauer P, Schmidt T, Schulte T, Riess O. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: clinical features, genetics, and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol 2004;3:291–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rossi M, Perez‐Lloret S, Doldan L, et al. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: a systematic review of clinical features. Eur J Neurol 2014;21:607–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moscovich M, Okun M, Favilla C, et al. Clinical evaluation of eye movements in spinocerebellar ataxias: a prospective multicenter study. J Neuroophthalmol 2015;35:16–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pedroso JL, França MC Jr, Braga‐Neto P, et al. Nonmotor and extracerebellar features in Machado‐Joseph disease: a review. Mov Disord 2013;28:1200–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moro A, Munhoz RP, Arruda WO, Raskin S, Moscovich M, Teive HAG. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3: subphenotypes in a cohort of Brazilian patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2014;72: 659–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moro A, Munhoz RP, Moscovich M, Arruda WO, Raskin S, Teive HAG. Movement disorders in spinocerebellar ataxias in a cohort of Brazilian patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2014;72: 360–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Teive HAG, Iwamoto FM, Camargo CHF, Lopes‐Cendes I, Werneck LC. Machado‐Joseph disease versus hereditary spastic paraplegia: case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2001;59:809–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moro A, Munhoz RP, Arruda WO, Raskin S, Teive HAG. Clinical relevance of “bulging eyes” for the differential diagnosis of spinocerebellar ataxias. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2013;71:428–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bourque PR, Warman‐Chardon J, Lelli DA, et al. Novel ELOVL4 mutation associated with erythrokeratodemia and spinocerebellar ataxia type 34. Neurol Genet 2018;4:e263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ruano L, Melo C, Carolina Silva M, Coutinho P. The global epidemiology of hereditary ataxia and spastic paraplegia: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Neuroepidemiology 2014;42:174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Teive HAG, Ashizawa T. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 10: from Amerindians to Latin Americans. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2013;13:393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, the PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kraft S, Furtado S, Ranawaya R, et al. Adult onset spinocerebellar ataxia in a Canadian movement disorders clinic. Can J Neurol Sci 2005;32:450–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moseley ML, Benzow KA, Schut LJ, et al. Incidence of dominant spinocerebellar and Friedreich triplet repeats among 361 ataxia families. Neurology 1998;51:1666–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ashizawa T, Figueroa KP, Perlman SL, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with spinocerebellar ataxias 1, 2, 3, and 6 in the US; a prospective observational study. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013;8:177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xia G, McFarland KN, Wang K, Sarkar PS, Yachnis AT, Ashizawa T. Purkinje cell loss is the major brain pathology of spinocerebellar ataxia type 10. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013;84:1409–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bushara K, Bower M, Liu J, et al. Expansion of the spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 (SCA10) repeat in a patient with Sioux Native American ancestry. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e81342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Figueroa KP, Waters MF, Garibyan V, et al. Frequency of KCNC3 DNA variants as causes of spinocerebellar ataxia 13 (SCA13). PLoS ONE 2011;6:e17811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Valera JM, Diaz T, Petty LE, et al. Prevalence of spinocerebellar ataxia 36 in a US population. Neurol Genet 2017;3:e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yabe I, Sasaki H, Chen DH,et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 14 caused by a mutation in protein kinase C gamma. Arch Neurol 2003;60:1749–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brkanac Z, Bylenok L, Fernandez M, et al. A new dominant spinocerebellar ataxia linked to chromosome 19q13.4‐qter. Arch Neurol 2002;59:1291–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lorenzo DN, Forrest SM, Ikeda Y, Dick KA, Ranum LP, Knight MA. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 20 is genetically distinct from spinocerebellar ataxia type 5. Neurology. 2006;67:2084–2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alonso E, Martinez‐Ruano L, De Biase I, et al. Distinct distribution of autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxia in the Mexico population. Mov Disord 2007;22:1050–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rasmussen A, Matsuura T, Ruano L, et al. Clinical and genetic analysis of 4 Mexican families with spinocerebellar ataxia type 10. Ann Neurol 2001;50:234–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Magaña JJ, Tapia‐Guerrero YS, Velázquez‐Pérez L, et al. Analysis of CAG repeats in five SCA loci in Mexican population: epidemiological evidence of a SCA7 founder effect. Clin Genet 2014;85:159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Velázquez Pérez L, Cruz GS, Santos Falcón N, et al. Molecular epidemiology of spinocerebellar ataxias in Cuba: insights into SCA2 founder effect in Holguin. Neurosci Lett 2009;454:157–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. González‐Zaldívar Y, Vázquez‐Mojena Y, Laffita‐Mesa JM, et al. Epidemiological, clinical, and molecular characterization of Cuban families with spinocerebellar ataxia type 3/Machado‐Joseph disease. Cerebellum Ataxias 2015;2:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dürr A, Smadja D, Cancel G, et al. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia type I in Martinique (French West Indies). Clinical and neuropathological analysis of 53 patients from three unrelated SCA2 families. Brain 1995;118(Pt 6):1573–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lezin A, Cancel G, Stevanin G, et al. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia type I in Martinique (French West Indies): genetic analysis of three unrelated SCA2 families. Hum Genet 1996;97:671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yearwood AK, Rethi S, Figueroa KP, Walker RH, Sobering AK. Diagnosis of spinocerebellar ataxia in the West Indies. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2018;8:567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gwinn‐Hardy K, Singleton A, O'Suilleabhain P, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 phenotypically resembling Parkinson disease in a black family. Arch Neurol 2001;58:296–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Giunti P, Sweeney MG, Harding AE. Detection of the Machado‐Joseph disease/spinocerebellar ataxia three trinucleotide repeat expansion in families with autosomal dominant motor disorders, including the Drew family of Walworth. Brain 1995;118(Pt 5):1077–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gaspar C, Lopes‐Cendes I, Hayes S, et al. Ancestral origins of the Machado‐Joseph disease mutation: a worldwide haplotype study. Am J Hum Genet 2001;68:523–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Baizabal‐Carvallo JF, Xia G, Botros P, et al. Bolivian kindred with combined spinocerebellar ataxia types 2 and 10. Acta Neurol Scand 2015;132:139–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Paradisi I, Ikonomu V, Arias S. Spinocerebellar ataxias in Venezuela: genetic epidemiology and their most likely ethnic descente. J Hum Genet 2016;61:215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pedraza OL, Prieto JC, Casasbuenas OL, Espinosa E. Clinical identification of hereditary ataxias. A study of 38 cases in Colombia. Rev Neurol 1997;25:1016–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roxburgh RH, Smith CO, Lim JG, Bachman DF, Byrd E, Bird TD. The unique co‐occurrence of spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 (SCA10) and Huntington disease. J Neurol Sci 2013;324:176–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Traschütz A, van Gaalen J, Oosterloo M, et al. The movement disorder spectrum of SCA21 (ATX‐TMEM240): 3 novel families and systematic review of the literature. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2019;62:215‐220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gheno TC, Furtado GV, Saute JAM, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 10: common haplotype and disease progression rate in Peru and Brazil. Eur J Neurol 2017;24:892–e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Figueroa‐Ildefonso E, Milla‐Neyra K, Inca‐Martinez M, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2: the second most frequent dominant ataxia in Peru. Neurology 2018;90(S15). [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cornejo MR, Timaná C, Chacón RD, et al. Frequency of spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3) or Machado Joseph disease in a Peruvian population. Mov Disord 2011;26:S2–S3.22021173 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gouw LG, Castañeda MA, McKenna CK, et al. Analysis of the dynamic mutation in the SCA7 gene shows marked parental effects on CAG repeat transmission. Hum Mol Genet 1998;7:525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Castañeda MA, Avalos C, Jerí FR. Clinical and genetic studies of a family from Peru affected by spinocerebellar ataxia type 7. Rev Neurol 2000;31:923–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Leonardi L, Marcotulli C, McFarland K, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 in Peru: the missing link in the Amerindian origin of the disease. J Neurol 2014;261:1691–1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Miranda CM. Diagnosis of spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (Machado‐Joseph disease) in Chile. Rev Med Chil 2015;143:126–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Saffie Awad P, Vial Undurraga F, Chaná‐Cuevas P. Clinical features of 63 patients with ataxia. Rev Med Chil 2018;146:702–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. León M, Chaná P. Changes in balance and gait after a single session of combined cerebellum and primary motor cortex transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in a person with SCA1. Mov Disord 2018;33(suppl 2). [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lopes‐Cendes I, Teive H, Calcagnotto ME, et al. Frequency of the different mutations causing spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA1, SCA2,MJD/SCA3 and DRPLA) in a large group of Brazilian patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 1997;55:519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jardim LB, Silveira I, Pereira ML, et al. A survey of spinocerebellar ataxia in South Brazil–66 new cases with Machado‐Joseph disease, SCA7, SCA8, or unidentified disease‐causing mutations. J Neurol 2001;248:870–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Teive H, Munhoz R, Arruda W, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxias–genotype‐phenotype correlations in 104 Brazilian families. Clinics 2012;67:443–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Teive HAG, Munhoz RP, Raskin S, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 10: Frequency of epilepsy in a large sample of Brazilian patients. Mov Disord 2010;25:2875–2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cintra V, Lourenço C, Marques S, de Oliveira L, Tumas V, Marques W. Mutational screening of 320 Brazilian patients with autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxia. J Neurol Sci 2014;347:375–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. de Castilhos R, Furtado G, Gheno T, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxias in Brazil–frequencies and modulating effects of related genes. Cerebellum 2014;13:17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Braga‐Neto P, Pedroso JL, Furtado GV, et al. Dentatorubro‐Pallidoluysian Atrophy (DRPLA) among 700 Families with ataxia in Brazil. Cerebellum 2017;16:812–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pedroso JL, Abrahao A, Ishokawa K, et al. When should we test patients with familial ataxias for SCA31? A misdiagnosed condition outside Japan? J Neurol Sci 2015;355:206–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bourassa CV, Raskin S, Serafini S, Teive HAG, Dion PA, Rouleau GA. A new ELOVL4 mutation in a case of spinocerebellar ataxia with erythrokeratodermia. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:942–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rodríguez‐Quiroga SA, Cordoba M, González‐Morón D, et al. Neurogenetics in Argentina: diagnostic yield in a personalized research based clinic. Genet Res (Camb) 2015;97:e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gatto E, Gao R, White M, et al. Ethinic origin and extrapyramidal signs in an Argentinian spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 family. Neurology 2007;69:216–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Laffita‐Mesa JM, Bauer PO, Kourí V, et al. Unexpanded and intermediate CAG polymorphisms at the SCA2 locus (ATXN2) in the Cuban population: evidence about the origin of expanded SCA2 alleles. Hum Genet 2012;131:625–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kunimoto I. Japanese migration to Latin America In: Stallings B, Szekely G, editors. Japan, the United States, and Latin America. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 1993;99–121. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Teive HAG, Munhoz RP, Raskin S, Werneck LC. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 in Brazil. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2008;66:691–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Martins S, Sequeiros J. Origins and spread of Machado‐Joseph disease ancestral mutations events. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018;1049:243–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Teive HAG, Moro A, Arruda WO, et al. Itajaí, Santa Catarina–Azorean ancestry and spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2016;74:858–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Vale J, Bugalho P, Silveira I, Sequeiros J, Guimarães J, Coutinho P. Autosomal dominant cerebelar ataxia: frequency analysis and clinical characterization of 45 families from Portugal. Eur J Neurol 2010;17:124–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Schöls L, Amoiridis G, Epplen JT, Langkafel M, Przuntek H, Riess O. Relations between genotype and phenotype in German patients with the Machado‐Joseph disease mutation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996;61:466–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Stevanin G, Dürr A, Brice A. Clinical and molecular advances in autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: from genotype to phenotype and physiopathology. Eur J Hum Genet 2000;8:4–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Almeida T, Alonso I, Martins S, et al. Ancestral Origin of the ATTCT repeat expansion in spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 (SCA10). PLoS ONE 2009;4:e4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Naito H, Takahashi T, Kamada M, et al. First report of a Japanese family with spinocerebellar ataxia type 10: the second report from Asia after a report from China. PLoS ONE 2017;12:e0177955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Grewal RP, Tayag E, Figueroa KP, et al. Clinical and genetic analysis of a distinct autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxia. Neurology 1998;51:1423–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Matsuura T, Achari M, Khajavi M, et al. Mapping of a gene for a novel spinocerebellar ataxia with pure cerebellar signs and epilepsy. Ann Neurol 1999;45:407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Teive H, Roa B, Raskin S, et al. Clinical phenotype of Brazilian families with spinocerebellar ataxia 10. Neurology 2004;63:1509–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Teive HAG, Munhoz RP, Arruda WO, Raskin S, Werneck LC, Ashizawa T. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 10–a review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2011;17:655–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. McFarland K, Liu J, Landrian I, et al. Repeat interruptions in spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 expansions are strongly associated with epileptic seizures. Neurogenetics 2014;15:59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]