Abstract

Purpose:

Acceptance and coverage of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in the United States has been suboptimal. We implemented a multifaceted provider and staff intervention over a 1-year period to promote HPV vaccination in a regional health care system.

Methods:

The intervention was conducted in nine clinical departments from February 2015 to March 2016; 34 other departments served as controls. The intervention included in-person provider and staff education, quarterly feedback of vaccine coverage, and system-wide changes to patient reminder and recall notifications. Change in first-dose HPV vaccine coverage and series completion were estimated among 11- to 12-year-olds using generalized estimating equations adjusted for age and sex.

Results:

HPV vaccine coverage in the intervention departments increased from 41% to 59%, and the increase was significantly greater than that seen in the control departments (32%—45%, p = .0002). The largest increase occurred in the quarter after completion of the provider and staff education and a patient reminder and recall postcard mailing (p = .004). Series completion also increased significantly system wide among adolescents aged 11—12 years following mailing of HPV vaccine reminder letters to parents of adolescents aged 12 years rather than 16 years.

Conclusions:

HPV vaccine uptake can be improved through a multifaceted approach that includes provider and staff education and patient reminder/recall. System-level change to optimize reminder and recall notices can have substantial impact on HPV vaccine utilization.

Keywords: HPV, Human papillomavirus vaccines, Health care providers, Intervention, Quality improvement, Health system

Since its introduction in 2006, acceptance and uptake of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in the United States has been slower than other recommended adolescent vaccines and remains well below the 2020 goal of 80% coverage of three doses of HPV vaccine [1,2], Recommended evidence-based strategies to increase vaccination coverage include multicomponent interventions that include provider education, assessment and feedback, and patient reminder and recall [3], For HPV vaccination in adolescents, recent reviews support both patient reminder and recall programs and provider assessment and feedback interventions [4], Systems-level approaches have also been identified as a promising strategy [5], Subsequently, multicomponent interventions targeting providers through education and assessment and feedback have resulted in significant increases in HPV vaccine initiation at two health centers [6] and increased opportunities for HPV vaccination among participants from a primary care network [7], Although these studies are promising, additional studies are needed in diverse health systems, where system-level changes may be required to reach and maintain high HPV vaccine coverage, We implemented and evaluated a multicomponent intervention to improve HPV vaccine utilization in a large, rural Midwestern health care system,

Methods

Setting

The intervention was implemented in the Marshfield Clinic Health System (MCHS), MCHS is a regional health care system with 49 locations in central, northern, and western Wisconsin, In early 2013, MCHS introduced several initiatives focused on increasing adolescent vaccinations, These included making adolescent vaccine coverage data available to providers and clinical staff, sending reminder and recall notices for the HPV vaccine to parents of 16-year-olds, and implementing a pediatric (including adolescents) immunization protocol that permitted vaccination, per schedule, with only a protocol order,

Intervention

We targeted seven locations within MCHS with the largest volume of adolescent patients for the intervention with the objective to reach as many adolescents as possible with the resources available, At each of the seven locations, departments with the largest adolescent population were selected (i,e,, intervention departments), Two departments that work closely with a selected department were also included as intervention departments (total nine departments: six pediatric and three family practice/other), All other departments that provide primary care and vaccinations to adolescents were included as control departments (34 departments) (Table 1), The intervention had three components: (1) in-person provider and staff education; (2) quarterly feedback to providers; and (3) patient reminder and recall notices, The intervention period began in the first quarter of 2015 and extended through the first quarter of 2016 (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of intervention and control departments at the beginning of the intervention (quarter 1, 2015)

| Intervention departments |

Control departments |

|

|---|---|---|

| Total adolescent population | 16,041 | 8,617 |

| Department characteristics | ||

| Number of primary care departments | 9 | 34 |

| Department type | ||

| Pediatric | 6 | 1 |

| Family practice/other | 3 | 33 |

| Median number of adolescents (IQR) | 1,833 (1,057–2,348) | 201.5 (104–338) |

| Median number of providers (IQR) | 9 (4–12) | 3 (2–4) |

| Provider specialty (%) | ||

| Pediatric, MD or DO | 44 | 2 |

| Family medicine, MD or DO | 36 | 52 |

| Internal medicine, MD or DO | 1 | 11 |

| Nurse practitioner | 13 | 24 |

| Physician assistant | 6 | 11 |

| Patient characteristics | ||

| Age | ||

| 11–12 y | 4,722 (29) | 2,227 (26) |

| 13–15y | 7,151 (45) | 3,718 (43) |

| 16–17y | 4,168 (26) | 2,672 (31) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 7,879 (49) | 4,253 (49) |

| Male | 8,162 (51) | 4,364 (51) |

| Percent of preventive care visits during study period (%) | 27 | 19 |

| Tdap vaccine coverage, % (95% CI) | 96.0 (95.7–96.3) | 95.5 (95.1–95.9) |

| Meningococcal conjugate vaccine coverage | 88.9 (88.4–89.5) | 86.0 (85.3–86.7) |

CI = confidence interval; DO = doctor of osteopathic medicine; IQR = interquartile range; MD = doctor of medicine; Tdap = tetanus/diphtheria/pertussis.

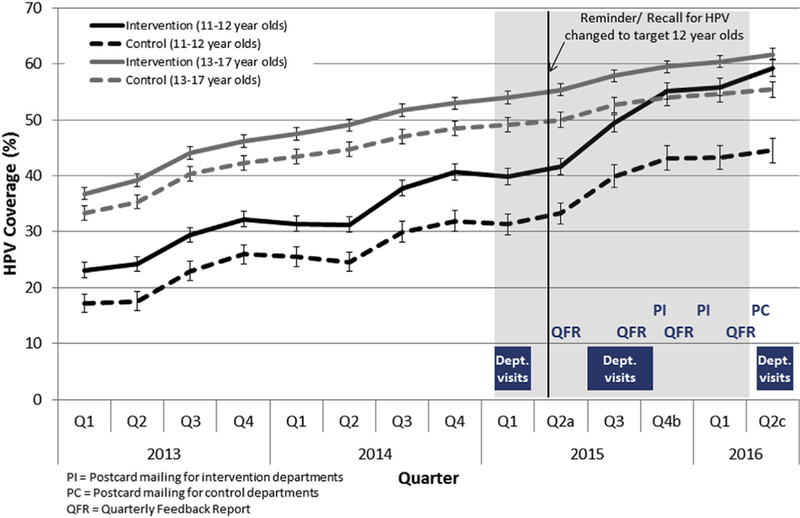

Figure 1.

HPV vaccine coverage among 11- to 12-year-olds and 13- to 17-year-olds by quarter and intervention and control departments, 2013—2016. Shaded area represent intervention period. ap = .03 for comparison between differences in the increase in coverage from Q1 to Q2 2015 between intervention and control departments among 13- to 17-year-olds. bp = .004 for comparison between differences in the increase in coverage from Q3 to Q4 2015 between intervention and control departments among 11- to 12-year-olds. cp = .0002 and p = .02 for comparison between differences in the increase in coverage from Q1 to Q2 2016 between intervention and control departments among 11- to 12-year-olds and 13- to 17-year-olds, respectively.

Provider and staff education.

Each intervention department was visited at least three times by project staff. These visits were held (1) at the beginning of the intervention period (quarter 1, 2015) to provide baseline feedback and introduce the study; (2) during quarters 3 and 4 of 2015 for the academic detailing sessions; and (3) after the intervention period to share preliminary study findings. The academic detailing sessions were led by a physician and/or immunization expert and consisted of didactic and discussion sections tailored to the specific department. The didactic component was the same for all departments (except for department-level data) and consisted of a brief presentation covering the reason for our visit (low HPV vaccine coverage); department’s performance on HPV vaccinations compared with other recommended adolescent vaccines, other departments, the state, and the United States; updates on new recommendations for use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in adolescents [8]; and how to make an effective recommendation for HPV vaccine based on CDC’s “You are the Key to HPV Cancer Prevention” presentation [9]. The discussion component varied at each visit, but generally focused on adolescent vaccination processes in the department, barriers to HPV vaccination, and successful strategies for promoting HPV vaccination based on anecdotal experience from other providers in the department and health system. These sessions were typically held during regularly scheduled department meetings, lasted 30—40 minutes, and were eligible for 0.5 credits of continuing medical education (CME) or continuing education units (CEU). Resources for providers and patient educational materials for HPV and other adolescent vaccinations (e.g., posters, patient education sheets, and links to resources available from the CDC, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Immunization Action Coalition) were also distributed as hard copies during the meeting and electronically to managers for distribution to all members of the department after the meeting.

Quarterly feedback.

Providers in the intervention departments received reports on their performance for all recommended adolescent vaccines via email, sent quarterly throughout the intervention period (total four reports). Each report included the provider’s coverage rates for first and third dose of HPV vaccine, meningococcal conjugate vaccine, and tetanus/diphtheria/pertussis vaccine booster by age group (11—12 and 13—17 years), as well as a comparison to their department and MCHS overall. Patients were assigned to a specific provider based on the provider the patient/parent identified as the primary provider in the electronic health record (EHR). If patients did not have a primary provider identified (approximately 7%—8% of the adolescent population), the patient was assigned to a provider based on an algorithm that considers number and timing of preventive (well-child) visits (and other visits, if no preventive visit) with a provider.

Patient reminder and recall notices.

Before the intervention, MCHS targeted 16-year-olds for reminder and recall letters for HPV vaccine. To be consistent with current recommendations and coincide with other recommended adolescent vaccines, the age group targeted for these letters was lowered in April 2015. The letters specified vaccines that were due (or overdue) for each child and were mailed to parents of 12-year-olds monthly from April 2015 to October 2015, and thereafter every other month, unless an opt-out request was received. Letters were generated from the MCHS population-based immunization registry that is linked to the EHR with real-time updates on immunization data and addresses (www.recin.org).

With the change in the target age for the HPV vaccine reminder and recall letters, adolescents aged 13—16 years who were coming due or overdue for HPV vaccine would have missed receiving the system-level reminder letters. Therefore, we sent a one-time postcard reminder to all parents of adolescents aged 11—17 years in the intervention departments who had not completed the HPV vaccine series after the completion of the academic detailing sessions. Based on the department’s preference, postcards were mailed out for seven of nine intervention departments on October 23, 2015 and for the remaining intervention departments on January 15, 2016. The postcard mailing in the control departments occurred after the active intervention period (April 4, 2016). The postcard had general information on all recommended adolescent vaccines, the patient’s primary care department’s phone number, and a weblink to obtain more information and schedule an appointment.

Evaluation

The primary outcome measure for intervention effectiveness was changed in HPV vaccine coverage from preintervention to postintervention in intervention versus control departments. We also assessed provider and staff participation in intervention activities, vaccine counseling from clinicians, parent/guardian receipt of vaccine reminder notices for their adolescent child, and appointment scheduling rates following postcard mailings.

Human papillomavirus vaccine coverage.

HPV vaccine (first-dose) coverage and series completion were estimated in quarterly time intervals from January 2013 through June 2016, in the intervention and control departments, using data available from the EHR and population-based immunization registry. Estimates were stratified by 11—12 and 13—17 year age groups, using generalized estimating equations adjusted for age (within age strata) and sex. We stratified by age group because intervention activities primarily focused on increasing uptake among 11- to 12-year-olds, the population the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends for routine HPV vaccination [10]. HPV vaccine coverage was estimated as the proportion of adolescents who had received the first HPV vaccine dose by the end of the measurement period among the eligible adolescent population. The adolescent population was composed of actively enrolled patients whose age at the end of each quarter was ≥11 and <18 years. Actively enrolled patients were defined as patients who had ≥1 preventive or ≥2 evaluation and management visits with an MCHS primary care provider in the prior 36 months. Therefore, for each quarter, although there was significant overlap, a different patient population was identified, as patients aged into and outside of the eligible age range, and thus, their qualifying visits may have changed from one measurement period to another. Series completion was estimated as the proportion of adolescents who initiated the HPV series >7 months before the end of the measurement period (to be eligible for completion) and who received three HPV vaccine doses.

For the primary outcome, differences in HPV vaccine coverage in the intervention versus control departments were assessed using the ratio of estimates for intervention versus control departments for the quarter after the intervention compared with the ratio of estimates for intervention versus control departments in the quarter before the intervention. Quarterly rates were also compared with the previous quarter to assess potential impact of the timing of intervention activities and because vaccine uptake varied throughout the year (highest during the third quarter, corresponding to the beginning of the school year, and lowest during the first and second quarter). p values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Provider and staff participation in intervention activities.

Adolescent primary care providers and staff were surveyed at the end of the intervention period via email and/or interoffice mail to assess participation/receipt (yes/no) and usefulness (four-point scale from no help at all to very helpful) of each intervention activity.

Vaccine counseling and receipt of reminders.

Weekly telephone surveys of parents/guardians of adolescent patients were used to assess vaccine counseling from clinicians and parent/guardian receipt of a vaccine reminder notice. Parents of adolescents aged 11—17 years were eligible for the survey if their child had a health care visit with a provider in the intervention department during the survey period and had not received HPV vaccine before that visit. A list of eligible patients, stratified by type of visit (preventive and other), was generated each week for each intervention department. Patients were selected randomly and parents/guardians of selected patients were invited to participate in the survey, starting with patients seen for a preventive visit, until the target sample size was reached for each department (~5 completed surveys per week per department) or all eligible patients were contacted. Receipt of vaccine counseling was defined as a positive response from parent/guardian to the question, “Did anyone recommend that [child’s name] get the HPV vaccine at that visit?” A positive response to the question, “Before the visit, did you or your child receive a reminder by mail, phone call, or email that [child’s name] was due or overdue for some of his/her vaccination?” was used to define receipt of vaccine reminders. To assess trends over time, surveys were grouped based on visit dates: early (first 5 months, January 2015—May 2015), middle (June 2015—October 2015) and end (November 2015—March 2016). The proportion of respondents who received HPV vaccine counseling and vaccine reminders during the middle and end periods were compared with those with the early period using chi-square tests.

Appointment scheduling rates.

Effectiveness of the reminder and recall postcard mailing was assessed by comparing appointment scheduling rates, defined as the proportion of patients who made an appointment for a preventive (well-child) or vaccination visit, during the 2 weeks following the mailing date between patients included and not included in the mailing. Patients who had completed the HPV vaccine series as of the mailing date and those with appointments made within 2 days of the mailing date were excluded. Proportions were compared using chi-square tests.

The Marshfield Clinic institutional review board determined this work as not human subjects research and did not require institutional review board review.

Results

At the beginning of the intervention (quarter 1, 2015), patients in the nine selected intervention departments represented 65% of the 24,658 adolescents aged 11—17 years who received primary care from MCHS. Department and patient characteristics of the intervention and control departments were different with respect to all characteristics examined except sex distribution of adolescents (Table 1). In general, intervention departments had a larger adolescent patient volume, more providers per department, higher proportion of providers with pediatric specialty, and higher vaccination coverage for recommended adolescent vaccinations.

Human papillomavirus vaccine coverage

Before the intervention, HPV vaccine coverage was generally higher in intervention departments than in control departments. Coverage gradually increased over time in both intervention and control departments (Figure 1). Among adolescents aged 11—12 years in the intervention departments, coverage increased from 40.6% before the intervention to 59.3% after the intervention and was significantly greater than that seen in the control departments (from 31.9% to 44.5%, p = .0002). The largest increase occurred during quarter 4, 2015, after the completion of the provider and staff education and postcard reminder mailing (p = .004).

Among adolescents aged 13—17 years, coverage in the intervention departments increased from 53.0% before the intervention to 61.7% after the intervention and was significantly greater than the control departments (from 48.4% to 55.4%, p = .001).

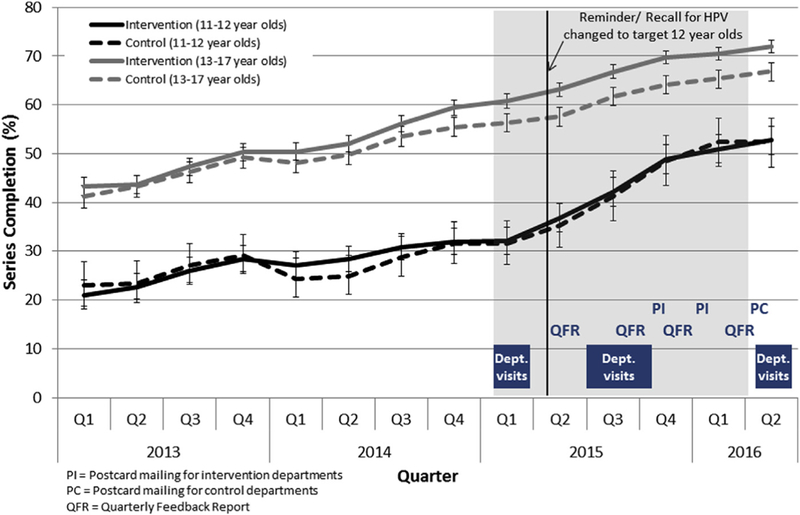

Series completion

HPV vaccine series completion increased throughout the intervention among adolescents aged 11—12 and 13—17 years (Figure 2). Among adolescents aged 11—12 years, series completion in the intervention departments increased from 32.0% before the intervention to 52.7% after the intervention. A similar level of increase was observed in the control departments, from 31.6% to 52.3% (p = 1.0). Among adolescents aged 13—17 years, the increase in series completion was similar in the intervention and control departments, from 59.4% to 71.9% and 55.5% to 66.9%, respectively (p = .08).

Figure 2.

HPV vaccine series completion among 11- to 12-year-olds and 13- to 17-year-olds who have initiated the HPV series >7 months before the end of the measurement period by quarter and intervention and control departments, 2013—2016.

Provider and staff education

Among 88 adolescent primary care providers and staff who completed the postintervention survey from the intervention departments, 47 (53%) reported attending an academic detailing visit and 44 (50%) acknowledged receipt of quarterly feedback reports. Among respondents, 68% and 43% found the in-person department visits and quarterly reports to be fairly to very helpful, respectively.

Human papillomavirus vaccine counseling

The proportion of parents/guardians who received HPV vaccine counseling at the most recent visit increased from 63% during the first 5 months of the intervention to 78% and 69% (p < .001 and .04) during the middle and end periods of the intervention, respectively (Table 2). The proportion of those who received HPV vaccine counseling and the HPV vaccine also increased from 20% during the early period to 28% and 26% (p = .0002 and .02) during the middle and end periods of the intervention, respectively. Similar patterns were observed when we stratified by adolescents aged 11—12 and 13—17 years, but increases in both receipt of a recommendation and HPV vaccine itself during the end periods among adolescents aged 13—17 years were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Parent postvisit survey results regarding clinician recommendation for HPV vaccine, receipt of HPV vaccine, and receipt of vaccine reminder notice before visit, by child age

| Study perioda | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Early | Middle | End | |

| Age 11–17y | |||

| n | 638 | 976 | 489 |

| Parent received recommendation, n (%) | 405 (63) | 766 (78) | 339 (69) |

| Received recommendation and HPV vaccine, n (%) | 128 (20) | 276 (28) | 126(26) |

| Receipt of vaccine reminder, n (%) | 169 (26) | 311(32) | 157 (32) |

| Age 11–12 y | |||

| n | 294 | 485 | 239 |

| Parent received recommendation, n (%) | 182 (62) | 390 (80)b | 170 (71)b |

| Received recommendation and HPV vaccine, n (%) | 76 (26) | 175 (36)b | 82 (34)b |

| Receipt of vaccine reminder, n (%) | 77 (26) | 197 (41)b | 84 (35)b |

| Age 13–17 y | |||

| n | 344 | 491 | 250 |

| Parent received recommendation, n (%) | 223 (65) | 376 (77)b | 169 (68) |

| Received recommendation and HPV vaccine, n (%) | 52 (15) | 101 (21)b | 44 (18) |

| Receipt of vaccine reminder, n (%) | 92 (27) | 114 (23) | 73 (29) |

HPV = human papillomavirus.

Surveys were grouped based on visit dates where the early, middle, and end periods represent the first 5 months (January 2015–May 2015), middle 5 months (June 2015–October 2015), and last 5 months (November 2015–March 2016) of the intervention period, respectively.

p < .05 comparing to early period.

Vaccine reminders

From January 2013 through March 2015, an average of 583 individualized letters per month were mailed system wide to parents of 12-year-olds who were due or overdue for recommended adolescent vaccines; HPV reminders were not sent until age 16 during this time period. After HPV vaccines were added to the reminder list for age 12, the monthly average increased to 2,384 (April 2015 through March 2016).

General adolescent vaccine postcards were mailed to 8,916 and 1,536 patients in the intervention departments in October 2015 and January 2016, respectively; a further 7,946 postcards were sent to patients in the control departments in April 2016, after the intervention ended. After the first mailing, 4.3% of patients included in the mailing made an appointment for a preventive/vaccination visit within 2 weeks of the mailing date compared with 3.5% of patients who were not included in the mailing (p = .01). However, appointment scheduling rates were higher among those who were not included in the second mailing compared with those who were included (1.9% vs. 1.1%, p = .03), and there was no difference in rates after the third mailing among those who were and were not included in the mailing (p = .5).

Parental/guardian reported receipt of a vaccine reminder notice increased from 26% during the first 5 months to 41% and 35% during the middle and end periods of the intervention (p < .02 and .04, respectively) for adolescents aged 11—12 years (Table 2). In contrast, there was not a similar increase reported for adolescents aged 13—17 years. Reported receipt of a vaccine reminder was associated with higher likelihood of receipt of HPV vaccine (36% vs. 27%, p < .0001, data not shown).

Discussion

We implemented a multifaceted approach to increase HPV vaccine uptake in adolescent patients of a regional health system. The intervention included provider and staff education, quarterly assessment and feedback, and patient reminder and recall notices. During the study period, HPV vaccine coverage increased in both intervention and control departments, but 11- to 12-year-olds in the intervention departments had significantly greater improvement in coverage relative to the control departments.

The increase in HPV vaccine coverage and series completion in adolescents aged 11—12 years may have been particularly influenced by the change in the age group targeted by the centralized, system-wide reminder and recall notices, which was lowered from age 16 to 12 years as part of the intervention. In contrast, the increase seen in adolescents aged 13—17 years during the active intervention period was lower and of similar magnitude to that seen in the previous year. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that have shown significant increases in series initiation [11,12] and completion [12—16] among adolescents with multiple reminder notices. In addition, the magnitude of the increase in coverage and completion rates are consistent with the median percentage point change of 16% for interventions that include a reminder and recall component in studies among infants and adults [17].

Although patient reminder and recall activities are recommended by the Task Force on Community Preventive Services for increasing vaccine coverage, few providers have incorporated this into their practices. Automated reminder/recall systems are complex and expensive and may be more feasible at a large health care systems level. At MCHS, immunization information is managed through our regional population-based registry and is linked to the state registry. This permits timely reminder and recall notifications for MCHS patients that can be customized at the practice level. Health systems with electronic access to immunization information should consider implementing centralized reminder and recall systems for adolescents to increase HPV vaccination coverage. Such systems have been shown to be cost-effective in improving vaccination rates among preschool children [18].

The method and timing of reminder and recall should also be considered. We saw significant increases in coverage and completion among 11- to 12-year-old adolescents, targeted parents reporting receipt of vaccine reminders, and appointment scheduling rates. However, scheduling rates were low (<4%) and we did not see a similar increase in appointment scheduling rates following the postcard mailing in the control departments at the end of the intervention period. The general postcard approach may not be as effective as repeated personalized letters that indicate specific vaccinations that are due [14,15,19]. The timing of the general mailing, at the start of the influenza vaccination season, may have also been influential in boosting general interest in vaccination. Text messaging is another promising technology for promoting timely vaccination. The latter is an effective method to increase series completion [14,15], and it was the preferred method for 40% of parents in a recent study regarding reminders for subsequent doses of HPV vaccine [19].

The provider- and staff-focused intervention may have provided an additional boost in adolescent HPV vaccination in the intervention departments. The significant increase in HPV vaccine coverage in 11- to 12-year-olds between intervention and control departments followed the completion of the education sessions and postcard mailing, and the increase continued beyond the intervention period. About half of the providers and staff in the intervention departments reported both attending the education sessions and receipt of the quarterly assessment and feedback reports. Previous interventions that included provider-focused education/training and assessment and feedback have also been successful [6,20,21] with significant increases after 1 month in one study [21].

Several methodological challenges limited our evaluation. Given national priorities and related efforts to promote HPV vaccination [22,23], it was virtually impossible to assemble a true control group or prevent “contamination” by some intervention activities within the same health system. The intervention was designed to increase coverage using multiple approaches; therefore, relative contributions cannot be attributed to individual activities. Also, intervention departments were selected based on their large adolescent population and were not necessarily comparable to control departments by design. Departments with a high volume of adolescent patients may have been more skilled or comfortable with adolescent vaccination and may not represent the typical provider’s practice environment. In addition, pediatric departments and providers with a pediatric specialty were over-represented in the intervention group. The rate of adoption of immunization recommendations is typically higher among pediatricians than family medicine physicians [24—28]. Results from this study may not be generalizable to other populations and health systems, as the intervention was conducted in one health system in a largely rural area of Wisconsin. However, findings from this study are consistent with previous studies. This intervention was supported by grant funding from CDC and similar system-based interventions may not be feasible in other health systems without additional resources. Finally, the intervention period was 1 year in duration and evaluation occurred concurrently. We were unable to evaluate long-term sustainability of the intervention; however, long-term results have varied with previous interventions [6,20]. Attention to HPV vaccination may wane in the absence of HPV vaccine-specific department visits and ongoing monitoring. Additional time would also be needed to examine the full impact of the intervention on series completion as all persons require a minimum of 6 months to complete the series.

System-based, multicomponent interventions are a key approach to increasing HPV vaccination coverage in adolescents [3,5]. First-dose HPV vaccine coverage and series completion rates increased from 13 to 21 percentage points following the intervention in our system. Efforts to achieve high HPV vaccine uptake should include strategies that focus on provider and staff education, as well as reminder and recall systems. Targeting and implementing system changes, such as inclusion or optimizing timing of and patient preferred methods for reminder and recall at the health system level are likely to be sustainable long term, and could increase effectiveness. Replication studies in smaller and more diverse practices are needed, along with continued monitoring, to ensure sustained increases in HPV vaccine coverage.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

System-based interventions can increase human papillomavirus vaccination in adolescents. These results show combined efficacy of strategies that focus on provider and staff education and optimize reminder and recall systems. Replication studies in smaller and more diverse practices are needed, along with continued monitoring, to ensure sustained increases in human papillomavirus vaccine coverage.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following for their contributions to the study: Burney Kieke, M.S., Sarah Kopitzke, M.S., Carla Rottscheit, Deanna Cole, Jacklyn Salzwedel, Jillette Peterson, and Suellyn Murray from the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Population Health, Darcy Vanden Elzen and Meranda Eggebrecht from the Center for Community Outreach, Marshfield Clinic, James H. Conway, M.D., FAAP, from the University of Wisconsin, School of Medicine & Public Health, Stephanie Schauer, Ph.D., from the Wisconsin Immunization Program, and Lisa H. Randall, J.D., M.P.H., Stefani Kloiber, M.S., C.H.E.S., and Lara Hillard, M.P.H., C.H.E.S., from the Minnesota Department of Health. Everyone who contributed significantly to the work has been acknowledged. This work was presented in part at the 2016 Wisconsin HPV Summits, Wausau and Milwaukee, WI, May 11—12, 2016 and the 47th National Immunization Conference, Atlanta, GA, September 13—15, 2016.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [200–2012-53587–0006].

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- [1].Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Immunization and Infectious Diseases. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives. Accessed July 27, 2016.

- [2].Reagan-Steiner S, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:850–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Recommendations regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med 2000;18(1 Suppl):92–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Oliver K, Frawley A, Garland E. HPV vaccination: Population approaches for improving rates. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016;12:1589–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Niccolai LM, Hansen CE. Practice- and community-based interventions to increase human papillomavirus vaccine coverage: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:686–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Perkins RB, Zisblatt L, Legler A, et al. Effectiveness of a provider-focused intervention to improve HPV vaccination rates in boys and girls. Vaccine 2015;33:1223–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fiks AG, Luan X, Mayne SL. Improving HPV vaccination rates using maintenance-of-certification requirements. Pediatrics 2016;137:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].MacNeil JR, Rubin L, Folaranmi T, et al. Use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in adolescents and young adults: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:1171–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preteen and teen vaccines for health care professionals/clinicians. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/who/teens/for-hcp.html. Accessed January 4, 2017.

- [10].Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination. MMWR Recomm Rep 2014;63(RR-05):1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Suh CA, Saville A, Daley MF, et al. Effectiveness and net cost of reminder/recall for adolescent immunizations. Pediatrics 2012;129:e1437–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Szilagyi PG, Humiston SG, Gallivan S, et al. Effectiveness of a citywide patient immunization navigator program on improving adolescent immunizations and preventive care visit rates. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2011;165:547–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cassidy B, Braxter B, Charron-Prochownik D, Schlenk EA. A quality improvement initiative to increase HPV vaccine rates using an educational and reminder strategy with parents of preteen girls. J Pediatr Health Care 2014;28:155–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kharbanda EO, Stockwell MS, Fox HW, et al. Text message reminders to promote human papillomavirus vaccination. Vaccine 2011;29:2537–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Matheson EC, Derouin A, Gagliano M, et al. Increasing HPV vaccination series completion rates via text message reminders. J Pediatr Health Care 2014;28:e35–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Szilagyi PG, Albertin C, Humiston SG, et al. A randomized trial of the effect of centralized reminder/recall on immunizations and preventive care visits for adolescents. Acad Pediatr 2013;13:204–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Briss PA, Rodewald LE, Hinman AR, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med 2000;18(1 Suppl):97–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kempe A, Saville A, Dickinson LM, et al. Population-based versus practice-based recall for childhood immunizations: A randomized controlled comparative effectiveness trial. Am J Public Health 2013;103:1116–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kempe A, O’Leary ST, Shoup JA, et al. Parental choice of recall method for HPV vaccination: A pragmatic trial. Pediatrics 2016;137:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gilkey MB, Dayton AM, Moss JL, et al. Increasing provision of adolescent vaccines in primary care: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2014; 134:e346–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Moss JL, Reiter PL, Dayton A, Brewer NT. Increasing adolescent immunization by webinar: A brief provider intervention at federally qualified health centers. Vaccine 2012;30:4960–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Accelerating HPV vaccine uptake: Urgency for action to prevent cancer A report to the President of the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2014. Available at: https://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/Advisory/pcp/annualReports/HPV/index.htm. Accessed March 27, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Call to action HPV vaccination as a public health priority. Bethesda, MD: National Foundation for Infectious Diseases; 2014. Available at: http://www.nfid.org/publications/cta/hpv-call-to-action.pdf. Accessed March 27, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Daley MF, Crane LA, Markowitz LE, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination practices: A survey of US physicians 18 months after licensure. Pediatrics 2010;126:425–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kempe A, Patel MM, Daley MF, et al. Adoption of rotavirus vaccination by pediatricians and family medicine physicians in the United States. Pediatrics 2009;124:e809–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Schaffer SJ, Szilagyi PG, Shone LP, et al. Physician perspectives regarding pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatrics 2002;110:e68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Davis MM, Ndiaye SM, Freed GL, Clark SJ. One-year uptake of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: A national survey of family physicians and pediatricians. J Am Board Fam Pract 2003;16:363–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Freed GL, Bordley WC, Clark SJ, Konrad TR. Universal hepatitis B immunization of infants: Reactions of pediatricians and family physicians over time. Pediatrics 1994;93:747–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]