Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Fast magnetic resonance imaging (fsMRI) sequences are single-shot spin echo images with fast acquisition times that have replaced CT scans for many conditions. Introduced as a means of evaluating children with hydrocephalus and macrocephaly, these sequences reduce the need for anesthesia and can be more cost-effective, especially for children who require multiple surveillance scans. However, the role of fsMRI has yet to be investigated in evaluating the posterior fossa in patients with Chiari I abnormality (CM-I). The goal of this study was to examine the diagnostic performance of fsMRI in evaluating the cerebellar tonsils in comparison to conventional MRI.

METHODS

The authors performed a retrospective analysis of 18 pediatric patients with a confirmed diagnosis of CM-I based on gold-standard conventional brain MRI and 30 controls without CM-I who had presented with various neurosurgical conditions. The CM-I patients were included if fsMRI studies had been obtained within 1 year of conventional MRI with no surgical intervention between the studies. Two neuroradiologists reviewed the studies in a blinded fashion to determine the diagnostic performance of fsMRI in detecting CM-I. For the CM-I cohort, the fsMRI and T2-weighted MRI exams were randomized, and the blinded reviewers performed tonsillar measurements on both scans.

RESULTS

The mean age of the CM-I cohort was 7.39 years, and 50% of these subjects were male. The mean time interval between fsMRI and conventional T2-weighted MRI was 97.8 days. Forty-four percent of the subjects had undergone imaging after posterior fossa decompression. The sensitivity and specificity of fsMRI in detecting CM-I was 100% (95% CI 71.51%–100%) and 92.11% (95% CI 78.62%–98.34%), respectively. If only preoperative patients are considered, both sensitivity and specificity increase to 100%. The authors also performed a cost analysis and determined that fsMRI was significantly cost-effective compared to T2-weighted MRI or CT.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite known limitations, fsMRI may serve as a useful diagnostic and surveillance tool for CM-I. It is more cost-effective than full conventional brain MRI and decreases the need for sedation in young children.

Keywords: Chiari malformation type I, Chiari I abnormality, magnetic resonance imaging, fast MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging with rapid acquisition times, also known as “fast MRI” (fsMRI), was introduced to evaluate ventricle size in children with shunt-dependent hydrocephalus.1,4,5,8,12 Fast MRI is derived from T2-weighted MRI with very short acquisition times, often aimed at answering very specific clinical questions.12 While fast sequences have image contrast and resolution inferior to those of conventional T2-weighted MRI sequences, fsMRI has shown utility in the evaluation of ventricle size and extraaxial CSF spaces. Prior to fsMRI, the mainstay methods for monitoring patients who required serial imaging were CT and/or conventional brain MRI. However, CT can expose patients to radiation, which raises clinical concerns when monitoring young children or those who require multiple follow-up exams.2 Conventional brain MRI, on the other hand, has longer acquisition times and often requires sedation in young children or clinically unstable patients who are prone to movement or unable to tolerate lengthy exams.6,11 Therefore, fsMRI can be particularly beneficial in such patient populations.

The main indication for fsMRI has traditionally been for evaluating ventricle size in hydrocephalus.10 However, the use of fsMRI has been increasingly expanded to evaluate other neurosurgical conditions such as macrocephaly, intracranial cysts, and select congenital abnormalities, as well as in postoperative settings.9

Chiari I abnormality (CM-I), also referred to as Chiari malformation type I, is defined as cerebellar tonsillar descent > 5 mm inferior to the McRae line at the foramen magnum. In contrast to CM-II, cerebellar vermian herniation and obstructive hydrocephalus are rare in CM-I. Syringomyelia can be associated with CM-I and is usually an operative indication for decompression. The herniated tonsils often have a “peg-like” appearance, and mild caudal displacement and flattening or kinking of the medulla may be present. Unlike other known clinical indications for fsMRI, at present, the diagnostic performance of fsMRI for the CM-I population is unknown.

At our institution, we have routinely performed fsMRI since 2014 for neurosurgical clinical decision-making; and currently, fsMRI is approved for the evaluation of hydrocephalus, ventricular shunts, intracranial cysts, trauma follow-up, and postoperative gross complications. We have also worked with our pediatric radiology department to create a new billing procedure specific to fsMRI. However, CM-I or follow-up of low-lying tonsils is currently not an approved clinical indication for fsMRI since the clinical utility of fsMRI for CM-I is unknown. To address this issue, our study goal was to examine the potential clinical utility of fsMRI for the CM-I population. Specifically, we hypothesized that fsMRI performance can match that of the conventional T2-weighted MRI protocol and can serve to screen and monitor structural abnormalities associated with CM-I.

Methods

Patient Population

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we performed a retrospective analysis of 337 pediatric patients who had undergone fsMRI at our institution between April 2014 and January 2017. Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) patient had a diagnosis of CM-I based on the presence of low-lying tonsils (> 5 mm below the foramen magnum) on radiology reports of conventional MRI; and 2) both fsMRI and conventional T2-weighted MRI studies had been obtained in the patient within 1 year and without intervening neurosurgical intervention between the two studies. Both preoperative and postoperative subjects with CM-I were included. Nondiagnostic images on either fsMRI or conventional T2-weighted MRI due to the presence of metal hardware or dental braces were excluded.

Imaging Protocol

Subjects were scanned using either 1.5- or 3-T MRI systems (Optima MR450, Discovery MR750, GE Healthcare) with an 8-channel head coil. The fsMRI protocol consisted of 3 orthogonal planes of single-shot fast spin echo (SSFSE; constant refocusing flip angle of 130°). For the SSFSE sequences, parameters were as follows: ASSET (SENSE) parallel imaging factor 2, half and full Fourier with homodyne reconstruction, effective TE 86 msec at 3-T MRI and 135 msec at 1.5-T MRI, matrix 256 × 256, and bandwidth 83 kHz. Consecutive 4-mm-thick slices with interleaved slice ordering were used. The FOV (18–22 cm) was adjusted to each patient’s anatomy. Conventional T2-weighted FSE MRI protocol was as follows: TR 2700 msec, TE 100 msec, slice thickness 5 mm, 0.5 mm skip.

Image Interpretation

Identification of CM-I

We constructed an fsMRI data set from both the 1) pre- and postoperative CM-I subjects (18 subjects) and 2) random subjects presenting with other neurosurgical conditions and without low-lying tonsils (30 controls). Clinical conditions for the entire cohort (48 subjects) are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Among the CM-I cohort, patients with low-lying tonsils (> 5 mm) and without surgical intervention were considered to have CM-I (true positives). Patients who underwent suboccipital decompression but still had low-lying tonsils were still considered to have CM-I (true positives). Patients with a prior history of CM-I but who had undergone suboccipital decompression and thus no longer had low-lying tonsils were considered to have resolved CM-I (true negatives). Subjects with other neurosurgical conditions and without low-lying tonsils were considered to be true negatives.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of CM-I patients who underwent fsMRI

| Case No. | Sex | Age at Scan (mos) | Duration of fsMRI Study (mins) | Op Status | fsMRI Field Strength (T) | Indication for Scan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 99 | 8 | Postop | 3 | avs: 2 days post-decompression |

| 2 | M | 129 | 12 | Postop | 1.5 | aVPSp: 3 days postop placement |

| 3 | M | 45 | 14 | Postop | 3 | avs: new-onset symptoms 6 mos postop decompression |

| 4 | F | 184 | 27 | Postop | 3 | avs: 1 day postop decompression |

| 5 | M | 55 | 1 | Preop | 1.5 | avs: evaluation for CM-I 1 day preop decompression |

| 6 | F | 63 | 1 | Postop | 3 | avs: 1 mo postop decompression |

| 7 | F | 33 | 16 | Preop | 1.5 | avs: routine FU 2 yrs post-VP shunt placement |

| 8 | M | 28 | 60 | Preop | 3 | avs: 1 day postop decompression |

| 9 | F | 39 | 10 | Postop | 3 | avs: 1 day postop decompression |

| 10 | M | 13 | 9 | Preop | 3 | avs: new-onset symptoms 7 mos postop VP shunt placement |

| 11 | M | 205 | 1 | Preop | 3 | avs: new-onset symptoms 1 mo postop decompression |

| 12 | F | 22 | 21 | Preop | 1.5 | aVPSp: 10 days postop VP shunt placement |

| 13 | F | 130 | 15 | Preop | 3 | avs: evaluation for possible CM-I |

| 14 | M | 31 | 23 | Preop | 3 | avs: routine FU for CM-I |

| 15 | M | 238 | 21 | Postop | 1.5 | avs: routine FU 2 yrs post-decompression & congenital VP shunt |

| 16 | F | 200 | 4 | Postop | 3 | avs: 2 days postop decompression |

| 17 | M | 36 | 1 | Preop | 3 | avs: 1 day postop ETV but no prior suboccipital decompression |

| 18 | F | 48 | 27 | Preop | 1.5 | avs: preop for CM-I decompression |

aVPSp = assess VP shunt position; avs = assess ventricle size; ETV = endoscopic third ventriculostomy; FU = follow-up; VP = ventriculoperitoneal.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of control patients who underwent fsMRI

| Case No. | Sex | Age at Scan (mos) | Duration of fsMRI Study (mins) | Op Status | fsMRI Field Strength (T) | Indication for Scan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 312 | 10 | Preop | 3 | avs: evaluation of aqueductal stenosis |

| 2 | M | 154 | 12 | Postop | 1.5 | aVPSp: 4 days postop shunt placement |

| 3 | M | 79 | 9 | Preop | 3 | avs: evaluation for tumor progression |

| 4 | F | 203 | 10 | Preop | 3 | avs: evaluation for inflammation |

| 5 | M | 46 | 17 | Preop | 1.5 | avs: evaluation of aqueductal stenosis |

| 6 | M | 80 | 22 | Postop | 3 | avs: evaluation after tumor resection |

| 7 | F | 111 | 8 | Postop | 1.5 | aVPSp: 1 mo postop |

| 8 | M | 119 | 8 | Preop | 3 | avs: 1 day preop VP shunt placement |

| 9 | F | 49 | 10 | Postop | 3 | avs: 1 mo postop decompressive hemicraniectomy |

| 10 | M | 186 | 19 | Postop | 3 | avs: 3 days postop ventriculostomy |

| 11 | M | 1 | 15 | Preop | 3 | avs: evaluation of pst fossa cyst |

| 12 | M | 0 | 16 | Preop | 1.5 | avs: evaluation of parenchymal density |

| 13 | F | 137 | 5 | Preop | 3 | avs: evaluation of intracranial cyst |

| 14 | M | 54 | 8 | NA | 3 | avs: evaluation of hamartoma |

| 15 | F | 3 | 19 | Postop | 3 | avs: 1 day postop ventriculostomy |

| 16 | F | 159 | 17 | Postop | 3 | avs: 1 day postop resection |

| 17 | M | 165 | 19 | Preop | 3 | avs: 13 days before VP shunt |

| 18 | F | 104 | 11 | NA | 3 | avs: FU for intraparenchymal hemorrhage |

| 19 | F | 3 | 6 | NA | 1.5 | avs: evaluation of intracranial cyst |

| 20 | F | 40 | 13 | NA | 3 | avs: evaluation of intracranial cyst |

| 21 | F | 93 | 42 | NA | 1.5 | avs: evaluation of intracranial cyst |

| 22 | F | 85 | 8 | Postop | 3 | avs: 15 days postop external ventricular drain placement |

| 23 | F | 62 | 7 | Postop | 3 | aVPSp: 3 yrs after shunt placement |

| 24 | M | 166 | 26 | NA | 1.5 | avs: evaluation of ependymoma |

| 25 | F | 114 | 0 | Postop | 3 | avs: 1 day postop ventriculostomy |

| 26 | M | 44 | 15 | NA | 1.5 | avs: evaluation for increased ICP |

| 27 | M | 169 | 11 | Postop | 1.5 | aVPSp: 1 day postop shunt placement |

| 28 | F | 21 | 5 | Postop | 3 | aVPSp: 1.5 yrs postop shunt placement |

| 29 | F | 183 | 10 | Postop | 3 | avs: 8 days postop tumor resection |

| 30 | M | 23 | 21 | Postop | 3 | aVPSp: 1 day postop shunt revision |

ICP = intracranial pressure; NA = not applicable; pst = posterior.

The data set was presented in random order and was independently reviewed by two board-certified second-year neuroradiology fellows (B.L. and A.C.). Both reviewers were blinded to patients’ medical history and clinical indication and were not aware of the context of their interpretation or the study design. Each reviewer was asked to associate each scan with what was most consistent among diagnoses in a multiple-choice list that included hemorrhage, ventriculomegaly, CM-I, syrinx, intracranial cyst, or other. The reviewers were also asked to provide a brief impression of the study.

Measurement of Tonsils

In the next step, the reviewers were provided a randomized series of fsMRI and T2-weighted MRI studies for the 18 subjects with CM-I and were asked to independently measure the tonsillar position below the foramen magnum in order to assess the clinical capability of fsMRI in measuring tonsillar position.

Cases with disagreement between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion with an independent board-certified pediatric neuroradiology attending (K.W.Y.) for a final diagnosis.

Data Analysis

Cohen’s kappa was calculated to determine the interrater agreement for identifying a CM-I on fsMRI. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated for each reviewer. Confidence intervals for sensitivity and specificity are “exact” Clopper-Pearson confidence intervals. The confidence intervals for the predictive values are the standard logit confidence intervals, as described previously.7 The Pearson correlation coefficient, which measures the linear correlation between two measurement techniques, was calculated for the measurement of tonsillar descent (distance of cerebellar tonsils below the McRae line) between the two reviewers for fsMRI versus T2-weighted MRI (agreement between MRI methods within the same reviewer) and between the two MRI methods for reviewer 1 versus reviewer 2 (agreement between the two reviewers, within the same MRI method). All statistical analysis was performed using the Python programming language.

Results

Subjects With CM-I

A total of 18 children met inclusion criteria for the study. These patients had a prior history of CM-I and had undergone fsMRI for the evaluation of ventricle size, ventriculoperitoneal shunt position, or posterior fossa anatomy (Table 1). Patient ages ranged from 1 month to 19.8 years, with a mean age of 7.39 years. Nine (50%) patients were male. Eight patients had undergone suboccipital surgical decompression, and according to conventional MRI, 7 patients were considered to have resolved CM-I. Eight patients had associated syrinx visible on conventional sagittal T2-weighted MRI. The time interval between the fsMRI and conventional T2-weighted FSE MRI ranged from 0 to 364 days (mean 97.8 days).

Image Quality

Fast MRI was considered to have adequate diagnostic quality to answer the clinical multiple-choice questions for all 18 CM-I subjects. For example, the size and configuration of the ventricles, extraaxial collections, and postsurgical changes were all successfully evaluated in these patients. Regarding hindbrain morphology, tonsillar descent visualized on fsMRI was comparable and consistent with that on T2-weighted MRI in all cases. No subjects had dental braces or metal artifacts resulting in nondiagnostic MRI. Three subjects in the control cohort had programmable shunts, which only manifested as a localized susceptibility artifact at the site of the shunt reservoir and did not compromise imaging quality for the purposes of ventricular assessment or evaluation of the posterior fossa. Other hardware such as nonprogrammable shunts (4 in the control group) or external ventricular drains (7 in the control group) did not result in susceptibility artifact or degradation of image quality.

Imaging Analysis

Using Cohen’s kappa, the interrater agreement in identifying CM-I on fsMRI studies was substantial at 0.66. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of the consensus read for identifying CM-I was 100%, 92.11%, 78.57%, and 100% (Table 3). False positives, where the reviewers identified CM-I where it did not exist or was surgically corrected, were only observed in patients who had prior posterior fossa decompression and not in any patients without a history of CM-I. If only preoperative scans are considered (10 scans), sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV increased to 100%.

TABLE 3.

Diagnostic quality of fsMRI in identifying CM-I

| Parameter | Reviewer 1 | Reviewer 2 | Consensus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 100% (71.51%–100%) | 90.91% (58.72%–99.77%) | 100% (71.51%–100%) |

| Specificity | 94.74% (82.25%–99.36%) | 84.21% (68.75%–93.98%) | 92.11% (78.62%–98.34%) |

| PPV | 84.62% (58.8%–95.49%) | 62.50% (43.86%–78.05%) | 78.57% (55.31%–91.57%) |

| NPV | 100% (100%–100%) | 96.67% (83.09%–99.52%) | 100% (100%–100%) |

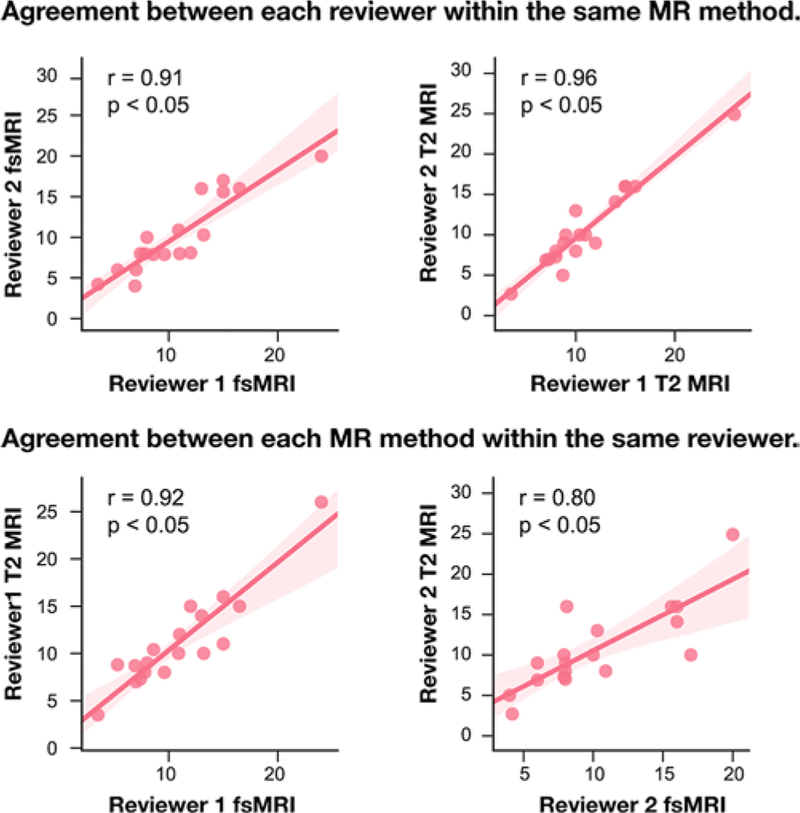

The Pearson correlation coefficient for tonsillar measurement consistency between fsMRI and T2-weighted MRI was 0.92 (p < 0.05) for reviewer 1 and 0.80 (p < 0.05) for reviewer 2. Similarly, Pearson coefficients for interrater agreement were 0.91 (p < 0.05) for fsMRI and 0.96 (p < 0.05) for T2-weighted MRI (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Pair plots showing the Pearson correlation between fsMRI and T2-weighted MRI and interrater reliability in measuring cerebellar tonsillar descent (in mm). Figure is available in color online only.

Time and Cost Analysis

The average total procedure time for our fsMRI protocol was 15.06 minutes (including patient positioning, localizer imaging acquisition, and multiplanar sagittal, coronal, and axial SSFSE fsMRI). In comparison, the average time for full conventional MRI for the same cohort (including conventional T2-weighted FSE MRI and other MRI sequences) was 64.72 minutes. At the time of our study, the mean cost of obtaining a single fsMRI study was $1736.00. In comparison, the mean cost of a standard CT was $5143.00 and that of a conventional brain MRI study consisting of sagittal T1, axial T2 FSE, axial T2 FLAIR, axial gradient recalled echo (GRE) or other T2* imaging, axial T1 spoiled gradient (SPGR), diffusion weighted imaging (DWI), coronal T2 FSE, and arterial spin labeling (ASL) perfusion was $8462.00. For patients undergoing anesthesia, there were additional fees associated with medication, monitoring, provider fees, and recovery room monitoring. In our cohort of CM-I subjects, 14 had conventional MRI performed at our institution, and 9 (64%) of them required anesthesia. Conversely, no subject undergoing fsMRI required any sedation.

Selected Cases

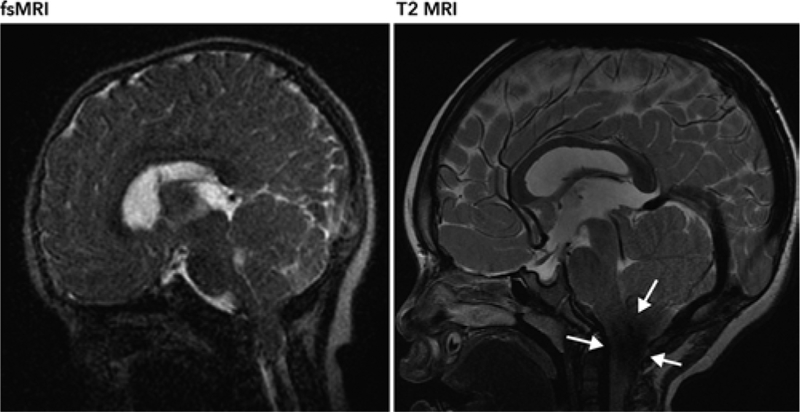

The patient in case 7 is a 3-year-old girl with a history of Crouzon syndrome, shunted hydrocephalus, and a mild CM-I that has not required surgical intervention. This patient has been followed up with serial fsMRI to evaluate for shunt positioning and ventriculomegaly. The posterior fossa was also adequately demonstrated on fsMRI. Tonsillar descent measured on the fsMRI study by two neuroradiologists was 16.5 and 16 mm. The same measurements obtained from a comparable T2-weighted MRI study were 15 and 16 mm. A CSF jet flow artifact at the foramen magnum on conventional T2-weighted MRI limits evaluation of the tonsillar position (Fig. 2). Although we did not systematically evaluate CSF jet flow artifact issues associated with T2-weigthed MRI compared to fsMRI given the small sample size, we often observed fewer CSF jet flow artifacts at the foramen magnum on fsMRI than on T2-weighted MRI.

FIG. 2.

A CSF jet flow artifact (arrows) was observed on the T2-weighted MR image, which obscured visualization of the foramen magnum. This was less severe on fsMRI, rendering better visualization of the tonsils.

The potential value of fsMRI in evaluating associated syrinx in CM-I warrants further investigation. The patients in cases 6 and 9 have CM-I, ventriculomegaly, and associated syrinx of the cervical cord. Although fsMRI studies were obtained to assess ventricle size and tonsillar anatomy after posterior fossa decompression, associated cervical syrinx was well visualized on fsMRI (Fig. 3). Of note, there has been an interval decrease in the cervical syrinx in case 9 in comparing the earlier scan (T2-weighted FSE MRI) to the follow-up scan (fsMRI).

FIG. 3.

Sagittal fsMRI studies demonstrating clear visualization of associated syrinx of the cervical spine.

Discussion

Although a large number of institutions in North America have implemented rapid-sequence MRI protocols,5 they have largely focused on evaluating hydrocephalus,1,10 ventriculoperitoneal shunt position,12 and macrocephaly.9 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the diagnostic capability and potential cost-effective role of fsMRI in the evaluation and follow-up of CM-I.

Since its clinical implementation at our institution in 2014, fsMRI has been primarily applied to neurosurgical patients with CSF-related disorders, such as hydrocephalus, ventriculomegaly, macrocephaly and the associated benign extracerebral spaces of infancy, arachnoid cysts, and postoperative evaluation, with the aim of answering specific clinical questions. Other institutions have employed fsMRI in additional contexts such as the surveillance of congenital abnormalities, evaluation for intracranial hypertension prior to lumbar puncture, and postoperative evaluation.9

At present, given the unknown performance of fsMRI for evaluating the CM-I population, CM-I is not an approved clinical indication for fsMRI associated with a specific billing code at our institution. Therefore, the cohort of CM-I subjects captured in our study reflects patients who had undergone fsMRI evaluation for other neurosurgical indications, such as ventriculomegaly, ventricular shunt placement, or in a postoperative setting (that is, the conditions listed above that are pre-approved for fsMRI), and were found to concomitantly have CM-I findings. In cases of suboccipital decompression, while it is possible that the surgeon observed adequate decompression, clinical decision-making directly relating to CM-I at the time of the fsMRI acquisitions was not performed. Given that we occasionally observe abnormal, low-lying tonsils on fsMRI studies obtained for various other pre-approved reasons, we sought to examine the diagnostic performance of fsMRI in evaluating cerebellar tonsils by comparing it to clinical gold-standard T2-weighted brain MRI.

Our study results showed that fsMRI can provide accurate assessment of posterior fossa anatomy and tonsillar position for both presurgical and postsurgical CM-I patients. Anatomical landmarks such as the basion and opisthion, which are used to construct McRae’s line, were well visualized on fsMRI studies, allowing for both accurate and concordant measurements of tonsillar positions comparable to those obtained with conventional MRI. Anecdotally, we observed diminished CSF jet flow-related artifacts at the foramen magnum on the fsMRI studies compared to those on conventional T2-weighted MRI studies, rendering fsMRI more facile in measuring tonsillar position. In cases in which a cervical syrinx was present on T2-weighted FSE MRI, all fsMRI studies correctly demonstrated the syrinx as well. We believe there is a potential clinical role for fsMRI as a single combined study of both the posterior fossa and the cervical spine in patients with CM-I.

Some motion artifacts were present in 2 subjects who had undergone fsMRI sequences, but they did not adversely affect the image quality and render the study nondiagnostic. No fsMRI exams required conversion to full diagnostic MRI or CT for evaluation of the posterior fossa.

This study has limitations including the retrospective nature of its design and overall small sample size. However, since CM-I is currently not a recognized clinical indication for fsMRI, only those CM-I subjects who had undergone fsMRI for other pre-approved neurosurgical conditions were available for inclusion in the study. Future larger prospective cohort studies and technical optimization of fsMRI could more systematically assess the clinical utility of fsMRI (for example, based on calculation methods described previously,3 a recruitment of 401 subjects could achieve a 95% confidence interval at 5% precision, using the expected sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 92.11%, respectively, derived from our study and a prevalence estimate of 0.25%13). At our institution, our pediatric neurosurgery team screens for an individual patient’s overall ability to tolerate MRI without sedation, which probably contributed to a high success rate in performing diagnostic-quality fsMRI exams. The resolution of fsMRI is inferior to that of conventional T2-weighted FSE MRI; thus, it is important to recognize potential pitfalls when a patient presents with low-lying tonsils not related to CM-I, such as in the setting of brain herniation, cerebellar neoplasm, or edema/infection. Finally, preoperative planning will still require the need for formal MRI studies that can be registered with the surgical navigation system.

Based on the encouraging results of this study, it would be prudent to perform a prospective study in which both fsMRI and T2-weighted MRI data on CM-I patients are collected in a single MRI session. In addition, given general concerns regarding fsMRI quality, we are currently investigating a new fsMRI technique that utilizes a variable refocusing flip angle in SSFSE to improve image quality (that is, image contrast, sharpness, and so forth) to best match that of conventional T2 sequences.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that fsMRI may be useful as an initial screening and surveillance tool for pediatric patients presenting with symptoms of CM-I. Such a strategy affords advantages such as quicker acquisition times, lower costs, and a decreased need for anesthesia. Future goals include improving the image quality of fsMRI, conducting prospective studies examining fsMRI and T2-weighted MRI sequences acquired in the same imaging session, and studying the impact of fsMRI data on the clinical decision-making process. Finally, the utility of fsMRI for other abnormalities of the posterior fossa, hindbrain, or spinal cord, such as CM-II, syringomyelia, and myelomeningocele, warrants consideration and future investigations.

Acknowledgments

A portion of this study was funded by NIH Grant No. R21HD083803.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CM-I

Chiari I abnormality

- FSE

fast spin echo

- fsMRI

fast magnetic resonance imaging

- NPV

negative predictive value

- PPV

positive predictive value

- SSFSE

single-shot FSE

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the finding specified in this paper.

References

- 1.Ashley WW Jr, McKinstry RC, Leonard JR, Smyth MD, Lee BC, Park TS: Use of rapid-sequence magnetic resonance imaging for evaluation of hydrocephalus in children. J Neurosurg 103 (2 Suppl):124–130, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner DJ: Estimating cancer risks from pediatric CT: going from the qualitative to the quantitative. Pediatr Radiol 32:228–244, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buderer NM: Statistical methodology: I. Incorporating the prevalence of disease into the sample size calculation for sensitivity and specificity. Acad Emerg Med 3:895–900, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forbes KP, Pipe JG, Karis JP, Farthing V, Heiserman JE: Brain imaging in the unsedated pediatric patient: comparison of periodically rotated overlapping parallel lines with enhanced reconstruction and single-shot fast spin-echo sequences. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 24:794–798, 2003 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iskandar BJ, Sansone JM, Medow J, Rowley HA: The use of quick-brain magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of shunt-treated hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg 101 (2 Suppl):147–151, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malviya S, Voepel-Lewis T, Prochaska G, Tait AR: Prolonged recovery and delayed side effects of sedation for diagnostic imaging studies in children. Pediatrics 105:E42, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mercaldo ND, Lau KF, Zhou XH: Confidence intervals for predictive values with an emphasis to case-control studies. Stat Med 26:2170–2183, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller JH, Walkiewicz T, Towbin RB, Curran JG: Improved delineation of ventricular shunt catheters using fast steady-state gradient recalled-echo sequences in a rapid brain MR imaging protocol in nonsedated pediatric patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 31:430–435, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Missios S, Quebada PB, Forero JA, Durham SR, Pekala JS, Eskey CJ, et al. : Quick-brain magnetic resonance imaging for nonhydrocephalus indications. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2:438–444, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel DM, Tubbs RS, Pate G, Johnston JM Jr, Blount JP: Fast-sequence MRI studies for surveillance imaging in pediatric hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg Pediatr 13:440–447, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramaiah R, Bhananker S: Pediatric procedural sedation and analgesia outside the operating room: anticipating, avoiding and managing complications. Expert Rev Neurother 11:755–763, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rozovsky K, Ventureyra ECG, Miller E: Fast-brain MRI in children is quick, without sedation, and radiation-free, but beware of limitations. J Clin Neurosci 20:400–405, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Speer MC, Enterline DS, Mehltretter L, Hammock P, Joseph J, Dickerson M, et al. : Chiari type I malformation with or without syringomyelia: prevalence and genetics. J Genet Couns 12:297–311, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]