Abstract

The apparently near-term effects of the monoclonal antibody BAN2401 in slowing the progression of prodromal Alzheimer's disease (AD) has created cautious optimism about the therapeutic use of antibodies that neutralize cytotoxic soluble amyloid-β aggregates, rather than removing plaque. Plaque being protective, as it immobilizes cytotoxic amyloid-β, rather than AD's causative agent. The presence of natural antibodies against cytotoxic amyloid-β implies the existence of a protective anti-AD immunity. Hence, for vaccines to induce a similar immunoresponse that prevents and/or delays the onset of AD, they must have adjuvants that stimulate a sole anti-inflammatory Th2 immunity, plus immunogens that induce a protective immunoresponse against diverse cytotoxic amyloid-β conformers. Indeed, amyloid-β pleomorphism may explain the lack of long-term protection by monoclonal antibodies that neutralize single conformers, like aducanumab. A situation that would allow new cytotoxic conformers to escape neutralization by previously effective monoclonal antibodies. Stimulation of a vaccine's effective immunoresponse would require the concurrent delivery of immunogen to dendritic cells and their priming, to induce a polarized Th2 immunity. An immunoresponse that would produce besides neutralizing antibodies against neurotoxic amyloid-β oligomers, anti-inflammatory cytokines; preventing inflammation that aggravates AD. Because of age-linked immune decline, vaccines would be significantly more effective in preventing, rather than treating AD. Considering the amyloid-β's role in tau's pathological hyperphosphorylation and their synergism in AD, the development of preventive vaccines against both amyloid-β and tau should be considered. Due to convenience and cost, vaccines may be the only option available to many countries to forestall the impending AD epidemic.

1. Introduction

Among the methods considered for treating Alzheimer's disease (AD), active immunotherapy (also known as vaccination) against amyloid β (Aβ) has been one of the most frequently tried [1]. This approach to AD therapy, which was first tested over 20 years ago with the AN1792 vaccine, has so far failed to show beneficial effects in humans. Indeed, the Aβ vaccines developed and tested to date induced production of antibodies that solubilize Aβ immobilized as plaque, but without tangible benefits on the patient's cognitive function. A consequence of the vaccine approach has been passive immunotherapy with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against Aβ. An approach based on the perception that administering targeted antibodies is more effective than trying to induce their production in vivo. After repeated setbacks with this approach, a new mAb, BAN2401, in the opinion of several researchers has shown to slow down the progression of early AD, creating cautious optimism in the field [2–5]. Another mAb, aducanumab, a replica of a protective antibody isolated from cognitively normal elderly humans, was found in a near-term phase 2 study to slow the progression of AD [3, 5, 6]. Yet, recently a long-term phase 3 clinical aducanumab study was ended, because of the unlikelihood that it would meet primary endpoints (http://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/biogen-and-eisai-discontinue-phase-3-engage-and-emerge-trials). The differences between the results of aducanumab's near-term phase 2 and long-term phase 3 clinical studies highlight the difficulties of treating AD after its onset, as discussed later in this review. Nonetheless, BAN24101 and aducanumab, differ from previous mAbs targeting monomeric Aβ [7], in that they recognize soluble cytotoxic Aβ protofibrils and oligomers (AβOs) [2, 3, 5–7], blocking their cytotoxicity. Their initial effects agree with reports from Klein et al. [8, 9] that the AβOs, and not the Aβ monomers or plaque, are the true culprits responsible for killing neurons. Subsequently, Klein et al. showed that antibodies against the AβOs rather than monomers, were the protective antibodies [10]. Later, Liu et al. [11] proved that nonprotective mAbs against regions like the Aβ N-terminal sequence (Aβ1-15) caused the release of cytotoxic AβOs that had been immobilized as plaque, an event known as the “dust-raising effect” [11, 12]. While anti-Aβ antibodies can solubilize plaque [13], this solubilization also can be achieved by methods like sonication [14]. Hence, it is apparent that plaque is a protection mechanism that immobilizes toxic soluble AβOs and Aβ protofibrils [15, 16]. Indeed, some people with high levels of Aβ plaque deposition are cognitively normal [17] further casting doubt on the putative role of plaque as the cause of AD.

From reports that antibodies against soluble AβOs, but not monomeric Aβ, protect neural cells against the cytotoxic effects of these amyloid-β aggregates, it is feasible to theorize that antibodies capable of neutralizing AβO cytotoxicity may be beneficial in preventing and/or treating AD. This objective apparently was achieved in transgenic mouse models with antibodies induced by vaccination, as well as the administration of certain mAbs directed against monomeric Aβ; results that could not be reproduced in humans. Therefore, it is likely that a vaccine capable of stimulating the production of antibodies blocking the cytotoxic properties of soluble Aβ aggregates could delay or prevent the onset of AD. Evidently, the reason for the reported clinical failure of AD vaccines is that they were designed to induce plaque removal rather than neutralize the cytotoxicity of Aβ soluble aggregates [12]. Besides, those vaccines had the wrong Aβ-derived antigen, i.e., Aβ1-14, combined with adjuvants that elicited an undesirable proinflammatory immunity rather than the required anti-inflammatory one [12]. The fact that soluble toxic Aβ aggregates have a large structural diversity that cannot be represented by the single linear epitope Aβ1-14 may explain why these vaccines failed to induce a protective immunity. A situation exacerbated by the fact that these vaccines were tested as therapeutic agents in elderly patients suffering of AD, where the immune system is weakened and the neurological damage may be beyond repair.

In this review, multiple issues concerning the development of effective AD vaccines will be discussed, taking into account past experiences with AD vaccines as well as new developments in AD passive immunotherapy. A significant body of information suggests that an effective AD preventive vaccine may be feasible, which would be radically different from the older vaccines. Considering the problems associated with aging, such as increase of inflammatory immunity and immunosenescence, it is doubtful that an effective therapeutic AD vaccine may be developed. Consequently, the AD vaccine development efforts should be focused on prevention rather than treatment.

2. Amyloid β, a Likely Vaccine Target

Since Alois Alzheimer reported a link between Aβ plaques and dementia, plaque deposits have become a hallmark of AD, considered by many to be the main causative agent of AD [16]. But recent information indicates that plaque may be a protection mechanism rather than the cause of AD [15–17]. Indeed, new evidence points to soluble AβOs and protofibrils, collectively Aβ aggregates, as the true AD etiological agents. Support for the role of Aβ aggregates as AD causative agents is provided by the work of Busche and Konnerth [18], which showed that AD's major functional impairments, e.g., excess neuronal activity and altered brain oscillations, are caused by AβOs in the absence of plaque. They also showed in transgenic mouse models that while mAbs against the Aβ1-15 region reduce plaque, they also aggravate neural disfunction [19]. This is likely a result of the released soluble cytotoxic Aβ aggregates from plaque, as explained in previous reports [11]. Bai et al. [20] provided further support for the proposition that AβOs and protofibrils, but not plaque, are AD's etiological agents. These scientists reported that abnormal dendritic calcium activity and synaptic depotentiation, which are associated with AD, occur before any Aβ plaque formation and that those abnormalities can also be induced by exogenous AβOs. The important role of AβOs in AD is further supported by the observation that AβOs isolated from the brains of AD patients caused impaired synaptic plasticity and memory when administered/injected in rats [21]. That coadministration of anti-AβO antibodies prevented those damaging changes, supports the use of immunotherapy as an option to prevent/treat AD. Accordingly, it is apparent that removal or solubilization of plaque by antibodies has no therapeutic value unless the cytotoxicity of soluble AβOs and Aβ protofibrils is neutralized, as appears to be the case with BAN2401 and aducanumab initial near-term results [3, 5, 6]. Since binding of antibodies to plaque results in plaque solubilization, the observation that BAN2401 and aducanumab reduce plaque was expected [6, 22].

Hence, the preliminary results obtained during the near-term phase 2 studies with aducanumab and BAN2401 point to new directions concerning the immunogen(s) needed to develop effective AD vaccines. Numerous reports have indicated that the immunogens needed to induce a protective immunity are the soluble AβOs and protofibrils, rather than either monomeric Aβ or plaque [8, 9, 23, 24]. These studies suggest that the critical epitope(s) is a conformational or three-dimensional one, rather than a linear one, such as the linear epitopes used in most AD vaccines tested to date except for AN1792 (Table 1). Support for an Aβ conformational epitope(s) is derived from studies using different soluble Aβ aggregates and the murine mAb precursor of the humanized mAb BAN2401. Indeed, this mAb recognizes the same common protofibril conformational epitope in all of the Aβ aggregates, regardless of differences in their amino acid sequences and N-terminal truncation [25]. Another important finding from the clinical and immunological studies with intravenous immunoglobulin preparations (IVIG) is that while natural antibodies (nAbs) recognize AβOs, they seldom recognize the Aβ monomer or its N-terminal region [23]. In contrast, vaccination with aggregated Aβ1-42 induces antibodies against both the oligomers and Aβ1-15 region [26]. Hence, AβO immunogens have been constructed with the Aβ1-15 region deleted, to prevent adverse antibody responses [27]; paradoxically, these undesirable immunoresponses are the ones being induced by practically all of the AD vaccines clinically tested or under development (Table 1).

Table 1.

Alzheimer's disease vaccines at the clinical or preclinical stage.

| Vaccine | Immunogen | Carrier | Adjuvant | Immunity◊ | Status |

|

| |||||

| AN1792 | Aβ1-42 | None | QS-21 | Th1/Th2 | Terminated |

| ACC-001 | Aβ1-7 | CRM197∗ | QS-21 | Th1/Th2 | Terminated |

| Affiris AD02 | mimic Aβ1-6 | KLH | Alum∗∗ | Th2 | Terminated |

| CAD106 | Aβ1-6 | VLP§ | None | - - - - | Phase 2 |

| V950 | Aβ N-terminal | ISCOMATRIX | Quil A | Th1/Th2 | Terminated |

| UB-311 | Aβ1-14 | UBITh¶ | CpG+Alum | Th1/Th2 | Phase 2 |

| AdvaxCpG | Aβ1-11 | Th epitopes | δ-inulin+CpG | Th1/Th2 | Pre-clinical |

| ABvac40 | C-term. Aβ40 | KLH | Alum∗∗ | Th2 | Phase 2 |

| ACI-24 | Aβ1-15 | Liposomes | MPLA▲ | Th1/Th2 | Phase 2 |

| Lu AF20513 | [Aβ1-112]3 | Tetanus toxin | - - - - | - - - - | Phase 1 |

| AADvac1 | Tau-C- 294-305 | KLH | Alum∗∗ | Th2 | Phase 1 |

(◊) Immunity means the type of immunity induced by the adjuvant, as reported in the literature and not the one described for the vaccine in question. (∗) CRM197 nontoxic diphtheria toxin. (∗∗) Alum a traditionally assumed Th2 adjuvant has many proinflammatory properties [67, 68]. (§) VLP are virus-like-particles derived from Qβ phage. (¶) UBITh is a proprietary set of T helper epitopes derived from MVT, PT and TT [75]. (▲) MPLA monophosphoryl lipid A.

Of significance for AD vaccines is that the immunoresponse elicited must be a systemic anti-inflammatory Th2 immunity, regardless of the presence of T-cell epitopes in the Aβ immunogen. Actually, those T-cell epitopes comprise the peptide sequences required to assemble the AβOs that stimulate the immune system to produce antibodies against the soluble Aβ aggregates. Indeed, nAbs and mAbs are being used in HIV-1 research to identify protective epitopes and create immunogens to induce a protective immunoresponse in HIV-1 vaccines [28, 29]. This situation supports the use of nAbs and mAbs, like aducanumab and BAN24021, to validate the selection of the soluble Aβ aggregates as immunogens for an AD vaccine. However, different from HIV-1 where there are no protective nAbs and the structures of the immunogens are still being determined, in AD the presence of protective nAbs and nature of the critical immunogens, i.e., AβOs and protofibrils, are known [9]. Hence, as with most vaccines, an effective AD vaccine should elicit a protective immunity rather similar to the natural one, but very unlikely a therapeutic one.

A consequence of the disappointing clinical results observed with Aβ-immunogens has been the development of alternative constructs that aim to mimic the epitopes responsible for Aβ neurotoxicity. Hence, besides the clinically unsuccessful Aβ1-15 derived immunogens [30, 31], certain constructs based on this sequence have been developed, which show beneficial effects in transgenic mouse models [32, 33]. Nonetheless, the fact that all of the clinically failed human vaccines and mAbs were found initially to be effective in AD transgenic mouse models raises serious concerns. The discrepancies between preclinical (mouse) and clinical (human) results may be explained by the fact that mice are more resilient than humans to the side effects of proinflammatory adjuvants, e.g., QS-21 and CpG [34], and that transgenic animals are artificial partial models of AD. Nonetheless, a new approach to develop novel immunogens is the use of Aβ oligomer-specific mimotopes, such as a dodecapeptide unrelated to Aβ and identified by Wang et al. [35]. This mimotope, as expressed on the surface of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, stimulates in mice the production of antibodies that recognize AβOs. However, if this dodecapeptide is expressed as a virus-like-particle or is conjugated to a protein carrier like KLH, it does not induce antibodies against AβOs [35]. These results indicate that both peptide and yeast are contributing to form a structure that mimics the AβO toxic conformational epitope. Though this new mimotope has beneficial effects in transgenic mice, it would need to be purified and its tridimensional-structure stabilized and tested in humans in order to become clinically acceptable. Nonetheless, that the protective antibodies induced by this mimotope target the AβOs rather than the monomeric forms strengthens the idea that soluble Aβ aggregates are one of the critical etiological agents in AD. The fact that the dodecapeptide forming the mimotope, when used by itself, can bind to Aβ monomers and inhibit the formation of cytotoxic AβOs [36], highlights its therapeutic potential to prevent the damaging Aβ aggregation leading to neurotoxicity.

A problem that has contributed to the uncertainties of AD research is Aβ's pleomorphism and that its different assemblies correlate with distinct AD phenotypes [37, 38], a situation seldom encountered with other self-antigens. Apparently, the size and conformation of AβOs play a role in their cytotoxicity and, probably, though not being well understood, in inflammation [39]. This condition raises concerns about the therapeutic value of a limited number of mAbs, considering the potential heterogeneity of the neurotoxic Aβ conformers. Another topic that has raised additional doubts about the role of Aβ in AD has been the failure of β secretase 1 (BACE1) inhibitors to improve cognitive function in AD patients [40]. But BACE1 inhibitors, while reducing the production of Aβ and thus plaque formation, do not prevent the Aβ oligomerization leading to the production of the soluble cytotoxic AβOs, which occurs before plaque formation [18–20]. Although the BACE1 inhibitors have been tested in AD patients as a therapeutic, the current consensus is that their administration should start in a preventive mode during the presymptomatic phase of AD [40, 41]. Hence, targeting plaque formation while ignoring the early production of AβOs most likely would not result in beneficial effects. Indeed, a significant body of evidence [3, 8–10, 18–20, 24, 39] indicates that cytotoxic soluble Aβ aggregates are the relevant immunogen for a preventive AD vaccine, rather than the nontoxic monomers or plaque.

3. The Case for a Natural Protective Immunity

The existence of a natural protective immunity is essential for the successful development of an AD vaccine. It follows that the onset of AD could be prevented and/or delayed by eliciting or boosting that immunity. During the past two decades, a significant body of evidence has been gathered that supports the presence of such immune protection against AD in healthy individuals.

3.1. Substantiation of a Protective Immunity

The existence of protective autoantibodies against AD has been previously demonstrated preclinically and clinically using IVIG [42]. However, fractionation of IVIG by affinity chromatography yielded a fraction containing anti-AβO antibodies that when administered to AD transgenic mice improved their cognitive function to a higher degree than whole IVIG [23, 43, 44]. These anti-AβO antibodies bind to Aβ oligomers, but not monomers, and, different from antibodies induced by previous AD vaccines, they do not readily clear plaque [43]. The beneficial effects of the anti-AβO antibody fraction on cognitive functions in mouse models backs the presence of protective anti-AD natural antibodies (nAbs) that, due to immunosenescence, decrease with age when AD starts to appear [45]. Some neutralizing antibodies from IVIG and mAbs, like aducanumab and BAN2401, also facilitate plaque removal, besides binding to Aβ oligomers and blocking their cytotoxicity. The fact that plaque removal occurs with both protective and nonprotective antibodies [11, 19] shows that plaque clearing and protection against cytotoxic AβOs are unrelated phenomena. Plaque solubilization may be explained by the formation of Aβ-IgG complexes, where the more hydrophilic IgG disrupts the ionic-hydrophobic interactions holding the plaque together, regardless of where the antibody binds to Aβ. Incidentally, the fact that the protective anti-AD effects of whole IVIG preparations depend largely on the diversity of the IgG pools and their content of anti-AβOs neutralizing nAbs can explain the variability in the reported IVIG clinical results [46].

While the IVIG studies support the existence of a natural protective anti-AD immunity and its beneficial effects in delaying this disease's progression, the challenges of producing the IVIG needed to treat a large population would be burdensome [39]. An alternative method would be the use of chromatographically isolated nAbs with anti-AβO activity, instead of whole IVIG [23, 43, 44]; indeed, preclinical studies have shown the superiority of this approach compared to whole IVIG [43]. Yet, the logistic problems associated with the procurement of IVIG from which nAbs would be isolated and their administration to large populations will persist, a situation that backs the development of a preventive AD vaccine. Liu et al. [47] have described some of the characteristics needed for effective AD therapeutic antibodies, which can also be applied to the nAbs induced by preventive vaccination.

3.2. Inferences from the mAbs Clinical Studies

The encouraging preliminary results for BAN2401, as well as aducanumab [3, 5, 6], disagree with those from previous mAbs and AD vaccines which targeted the wrong Aβ-species, i.e., monomers and plaque, rather than the cytotoxic Aβ aggregates [12, 48]. Preliminary results from the BAN24101 study showed that at 18 months there was a dose-dependent slowing in cognitive decline from baseline [5]. At the highest dose, 10 mg/kg biweekly, the reduction was 30% on the ADCOM scale and 47% in the clinical decline, according to the ADAS-Cog scale [5, 49]. A concern with the BAN2401 study is the uneven distribution of APOE4 carriers, since the carriers were removed from the high-dose group, but not from the placebo one. But, in the opinion of some experts while that imbalance may create a possible bias, it does not seem to be a major concern [49]. Another issue with those results is that they may be artifacts due to the Bayesian statistical analysis used to interpret the clinical data rather than a frequentist statistical analysis [2]. But, a comparison of both methods shows the Bayesian analysis, which applies probabilities to statistical problems, to be more rigorous. By incorporating past information into the analysis, the Bayesian approach benefits from previous data [50], allowing deciding, based on early analysis of the responses, if a study offers strong signals of success or failure which may warrant its continuation or termination, respectively [51]. Different from frequentist statistics where a single parameter determines the clinical endpoint, the end point in the Bayesian adaptive phase 2 evaluation of BAN2401 is decided by the AD Composite Score (ADCOMS) [52]. ADCOMS, composed of 12 items that measure mild cognitive decline and none or limited functional impairment, apparently provides an improved sensitivity to determine minor cognitive changes [52], a reasonable approach considering the variety of pathological effects mediated by the cytotoxic Aβ aggregates. Hence, from the available information, it is possible to assume that the BAN2401 results are not a result of artifacts caused by the Bayesian statistics.

The fact that BAN2401 and aducanumab [53], like the nAbs isolated from IVIG, recognize Aβ soluble cytotoxic aggregates, apparently protecting neural cells from their damaging effects bolsters the role of immunity as a defense against AD. But for an effective protection, the antibody response must be targeted to the soluble aggregates, while avoiding the Aβ1-15 region, which causes the release from plaque of sequestered cytotoxic aggregates.

3.3. Aβ Clearance: Immunological Implications

An important issue in AD is the fate of the AβOs and IgG-AβO complexes, like those formed during plaque removal which occurs by several mechanisms. Soluble Aβ aggregates can be removed from the brain by enzymatic degradation and cellular uptake, transport across the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB), interstitial fluid (ISF) bulk flow, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) absorption into the circulatory and lymphatic systems [54, 55], processes that may take place concurrently. While BAN2401 and aducanumab appear to facilitate clearance of IgG-AβO complexes via Fc-dependent microglial phagocytosis [22, 56], extracellular Aβ also can be cleared by the other mechanisms [54]. The ‘peripheral sink hypothesis' is a safe antibody-mediated mechanism for reduction of AβO where anti-Aβ antibodies circulating in the blood bind and sequester plasma Aβ, thus preventing its entry into the brain [47]. By disrupting the equilibrium across the BBB, the Aβ content inside the brain would remain low, preventing the formation of toxic AβOs. However, the peripheral sink clearance is not supported by results obtained with BACE1 inhibitors, where lowering Aβ production did not improve cognitive function, possibly because these drugs were used as a treatment, rather than in a preventive mode before the onset of disease [40, 41].

The need for Th2 immunity in AD immune therapy is emphasized by the association of the microglia phagocytic activity with the M2 activation phenotype, which is anti-inflammatory, and that such activity can be decreased by proinflammatory cytokines [57]. Although binding of IgG's Fc region to the high-affinity human Fc-receptor on microglia, FcγR1, could promote IgG-mediated inflammation [55], that appears not to be the case with BAN2401 or aducanumab, as shown by safety studies [2, 6]. Thus, it is feasible that the Fc regions of these mAbs bind to low-affinity IgG FcγRs, which are less likely to induce an inflammatory immunoresponse [58]. Important for AD vaccine development is that AβOs and perhaps protofibrils can initiate AβO neurotoxicity by interacting with the FcγRIIb receptor on neurons, a damaging effect that may be inhibited by antibodies blocking AβO interactions with that receptor [59]. The effects of interactions between IgG's Fc and FcγR on the type of immunity, i.e., Th1/Th17 or Th2, bolster the prerequisite that anti-AD vaccines must induce a systemic anti-inflammatory Th2 immunity, an immunity that would allow the production of neutralizing antibodies and clearance of Aβ by microglia's phagocytosis, without adverse Th1 proinflammatory immunoresponses.

The safety of nAbs against cytotoxic AβOs is supported by the fact that clinical studies have failed to show differences in the rate of serious adverse effects among individuals receiving IVIG and 0.9% isotonic sodium chloride solution [60]. Based on the information available from clinical studies with IVIG-derived nAbs, and mAbs like aducanumab and BAN-2401, it is evident that safe and effective AD preventive vaccines should induce a sole anti-inflammatory Th2 immunity. However, some vaccines under development use proinflammatory adjuvants to elicit an immunoresponse, a strategy that ignores the damaging effects of an inflammatory immunity on AD progression [61, 62].

4. AD Vaccines: Clinical Outcome

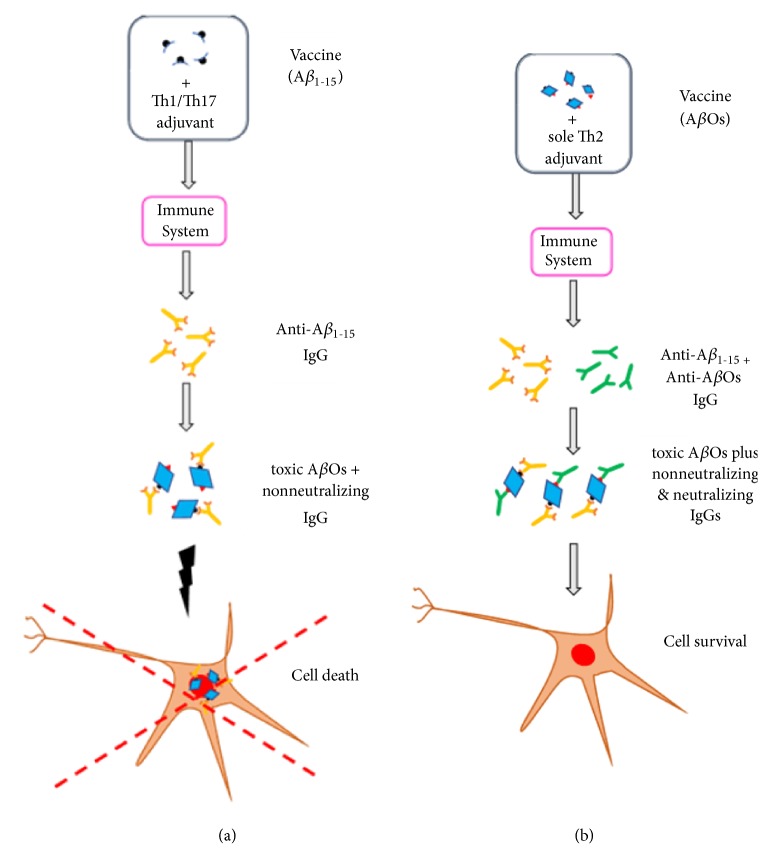

The apparent near-term benefits of the mAbs aducanumab and BAN2401 on prodromal AD as shown by the phase 2 clinical studies [3] implies that the cytotoxic soluble Aβ aggregates are the etiological agents of AD, and also explains the disappointing results of past AD vaccines [63]. Due to their immunogens derived from the Aβ1-15 region, the B-cell epitope, those vaccines induced antibodies against the Aβ monomers and exposed N-terminal region in cytotoxic AβOs and protofibrils (Figure 1(a)). Although such antibodies recognized Aβ aggregates, they failed to neutralize the conformational epitope(s) responsible for toxicity. This resulted in plaque removal by solubilizing the immobilized cytotoxic AβOs [11, 19], but without neutralizing them [48]. A special situation was observed with the AN1792 vaccine, which had aggregated Aβ42 plus the strongly proinflammatory adjuvant QS-21. This vaccine caused meningoencephalitis during phase 2 clinical studies, which prompted the termination of the study [64]. Evidently, the damaging proinflammatory Th1/Th17 autoimmune response induced by QS-21 [65] was boosted significantly higher during phase 2 by the addition of the detergent polysorbate 80 to the vaccine formulation [12, 48]. One outcome of this study has been the belief that despite its problems, AN1792 reduced plaque and also improved cognitive decline as compared to the group receiving placebo with QS-21 [66]. But, as reported by Von Bernhardi [67], those receiving placebo with QS-21 had an abnormally high rate of cognitive decline, i.e., 6 to 7 points loss in the Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE), which is greater than the average loss of 3.5 to 4 points for AD patients. These results show that a systemic proinflammatory immunity, like that induced by QS-21, exacerbates AD even in the absence of an autoimmune response [68].

Figure 1.

Immune response induced by different Aβ vaccines. (a) Vaccines having the Aβ N-terminal region (Aβ1-15) as an immunogen induced the production of antibodies (orange) that while binding to Aβ monomers and AβOs, are not protective. Similar to the ineffective mAbs that bound Aβ1-15, these antibodies cannot neutralize the cytotoxic AβOs, and protect neural cells from death. That these antibodies release toxic AβOs, which were immobilized as plaque, increase their harmful levels in the brain. Use of proinflammatory adjuvants in these vaccines, induces a systemic Th1/Th17 immunity, which increases the damage associated with AD. (b) Vaccines having AβOs as an immunogen and a sole Th2 adjuvant, elicit an anti-inflammatory immunity characterized by the production of antibodies against the Aβ N-terminal region (black) and AβOs cytotoxic conformational epitopes (red). Different from previous AD vaccines, which only induced production of anti-Aβ1-15 antibodies (orange), the antibodies against the AβOs' cytotoxic epitopes will be neutralizing ones (green), thus protecting the neural cells from death. Since the elicited neutralizing antibodies are against different conformational epitopes, it is feasible to expect some cooperative effects among the different antibodies. A synergism that would increase their protective effects on neural cells. Stimulation of a sole systemic anti-inflammatory immunity will prevent and/or delay some of the AD pathological changes associated with inflammation.

Clinical studies have shown that vaccines having Aβ-derived immunogens without T-cell epitopes, but formulated with Th1 adjuvants, despite exhibiting beneficial effects in AD transgenic mouse models; they did not benefit humans [30, 31]. Another factor contributing to these vaccines' poor performance and side effects s has been the absence of effective sole anti-inflammatory Th2 adjuvants [34, 69]. Alum, the traditionally assumed sole Th2 adjuvant induces production of proinflammatory cytokines, activates complement, and stimulates the activation of monocytes [70, 71], all adverse proinflammatory activities in vaccines against proteopathies. The presumed solution to the damaging T-cell mediated autoimmunity from past AD vaccines, had been to use the B-cell epitope Aβ1-15 or peptides from that sequence, conjugated to carrier proteins or peptides [72, 73], combined with Th1 adjuvants to yield high antibody titers (Table 1). This solution ignores that these adjuvants induce a systemic proinflammatory immunity, regardless of the absence or presence of an immunogen, as shown by the detrimental effects of QS-21 alone on the cognitive function of individuals affected by AD [67]. Hence, it is premature to conclude from the past failures of AD passive and active immunotherapy that Aβ is the wrong therapeutic target for vaccine development. Actually, the poor results are those expected for AD vaccines having the incorrect immunogen and adjuvant, as discussed in this review.

A problem affecting AD vaccine development has been the lack of information about their composition. For instance, the immunogen for most AD vaccines had been short Aβ peptide sequences linked to a carrier. But crosslinkers may have groups like maleimide, which due to their high immunogenicity, suppress the immune response against the peptide [48, 74]. The fact that vaccines like Affitope AD02, and presumably CAD106, have peptides mimicking Aβ1-15, conjugated to a KLH or virus-like-particle carrier by maleimide crosslinkers, indicates that the potential maleimide's interference with the immunoresponse was not considered [48, 74]. Thus, there is little information to explain these vaccines' failures, a deficiency that may have contributed to the disappointments, since all the vaccines had related immunogens based on the Aβ1-15 region (Table 1) [31, 72, 75]. The results for the vaccines ACC-001 and CAD106 [76, 77], having immunogens derived from Aβ1-15, show that they induced antibodies against that sequence which removed plaque, causing brain volume's loss. But apparently those antibodies did not neutralize cytotoxic AβOs, which cause the death of neural cells [11, 19, 20]. Thus, the released cytotoxic AβOs may aggravate the course of AD in the long-term (Figure 1(a)). An unexpected result of the ACC-001 vaccine study is the absence of cognitive differences among individuals receiving saline solution, QS-21-only, or the immunogen plus QS-21 [76]. These results contrast those from the AN1792 study, where QS-21-alone worsened cognitive functions as compared to the decrease in untreated AD patients [67]. This discrepancy may be explained by the fact that both studies used the same 50 μg dose of QS-21 as a placebo, but with and without polysorbate. It is well-known that addition of some detergents increases QS-21 adjuvanticity by several folds, inducing a higher and damaging systemic proinflammatory Th1/Th17 immunity [12, 48].

A vaccine undergoing clinical studies, UB-311, has an immunogen comprising the B-cell epitope, Aβ1-14, linked to two different T helper (Th) peptides [33, 78]. It has been reported that UB-311, which contains alum plus CpG ODN as an adjuvant, induces Th2 immunity [78]. But, the selection of CpG as an adjuvant is unexpected, since the CpG motif is a TLR9 ligand well-known to induce a strong proinflammatory Th1 immunity against cancer and pathogens [79, 80]; an immune response that would antagonize the desirable effects of an AD vaccine. Actually, another vaccine containing Aβ1-14 linked to pathogen-derived Th epitopes as an immunogen and the adjuvant δ-inulin/CpG ODN, induced both strong Th1 and Th2 immune responses, rather than a noninflammatory Th2 immunity [81]. Hence, the reported Th2 immunoresponse induced by UB-311 might be due to the Th peptides to which the Aβ1-14 is linked [78]. The antibodies induced by UB-311 in humans are reported to bind Aβ monomers, oligomers and fibrils, inhibiting fibril formation and associated cytotoxic effects [78]. According to the investigators, the results of the cognitive studies, while being apparently promising, are not statistically significant due to the small number of patients.

Consequently, it is evident from the poor results of AD vaccine clinical studies that progress in this area has been negligible, most likely the result of the vaccine formulations used [12, 34, 48]. The majority of AD vaccines to date have used the Aβ1-15 region as the immunogen. This selection ignores that the anti-AβO nAbs shown to protect neural cells from the toxic effects of AβOs and fibrils, and improve cognitive functions in AD transgenic mice, recognize the Aβ mid-/C-terminal rather than the Aβ1-15 region. [23, 44]. Unlike most self-antigens in autoimmune diseases, Aβ is pleomorphic and its different assemblies correlate with distinct AD phenotypes that may cause various pathological effects [37, 38]. Thus, vaccines targeting only the Aβ1-15 region may be of no value, since effective AD vaccines should target other relevant epitopes found in Aβ oligomers, an approach that requires using the whole Aβ as an immunogen, including the T-cell epitopes' sequences, to form the different conformational epitopes of AβOs and fibrils (Figure 1(b)). This comment may be also applied to mAb therapy, where the antibody recognizes a single conformational epitope. Finally, effective AD vaccines will require sole anti-inflammatory Th2 adjuvants that inhibit detrimental, inflammatory Th1/Th17 immune responses, while inducing the DCs responsible for regulating immunity, towards a tolerogenic phenotype, thereby biasing the immune response towards an antibody one [82, 83].

5. Feasibility of an Effective AD Vaccine

An examination of the relationships between Aβ and AD reveals a complexity beyond that of the conventional theory that an excess of Aβ and plaque deposits are AD's causative agents [7, 9, 24], a theory clouded by the fact that all of the studies attempting to treat AD by plaque removal and/or lowering Aβ levels in the brain have failed to show beneficial effects clinically. Hence, some authors have raised questions about the validity of the Aβ hypothesis, as well as the design of the studies, e.g., the drugs being tested and target population [84], which may have contributed to the poor results. Yet, it is evident that those studies did not take into account the damaging effects that soluble Aβ aggregates, i.e., AβOs and protofibrils, inflict on neural cells leading to AD [18–20, 37, 39]. Thus, based on the information derived from the IVIG's anti-AD nAbs, the initial near-term results with the mAbs aducanumab and BAN2401, and the structural characteristics of the different Aβ aggregates, the likelihood of developing a different but useful preventive AD vaccine seems reasonable. Here, the characteristics of the key components of such a vaccine, i.e., the immunogen and the adjuvant, will be addressed.

5.1. Amyloid β Derived Immunogens

While AD vaccine development has been biased towards the use of the Aβ1-15 (B-cell epitope) as a safe immunogen (Table 1), a large body of evidence points to the Aβ soluble aggregates as the proper antigen. Actually, immunogens based on the Aβ1-15 peptide would induce a damaging antibody response [11, 47] (Figure 1(a)). Instead, a suitable immunogen might contain a wide distribution of AβOs, from ~ 10 kDa to more than 100 kDa, i.e., the cytotoxic ones [27, 85–87]. But, since oligomerization depends on both concentration and time, a long-term incubation may alter the vaccine formulations with concomitant changes in their immune stimulatory properties. One solution to the instability problem could be cross-linking of the oligomeric forms in a manner that does not alter their immunogenic properties. Glutaraldehyde [27] has been used to stabilize these oligomers, but while sound, this approach may have complications due to glutaraldehyde polymerization. An alternative method is the use of 1,5-difluoro-2,4 dinitrobenzene (DFDNB), a cross-linking agent that reacts with lysine's amino groups [88]. In fact, DFDNB cross-linked AβOs are particularly potent in inducing memory dysfunction in mice, an AD associated disorder.

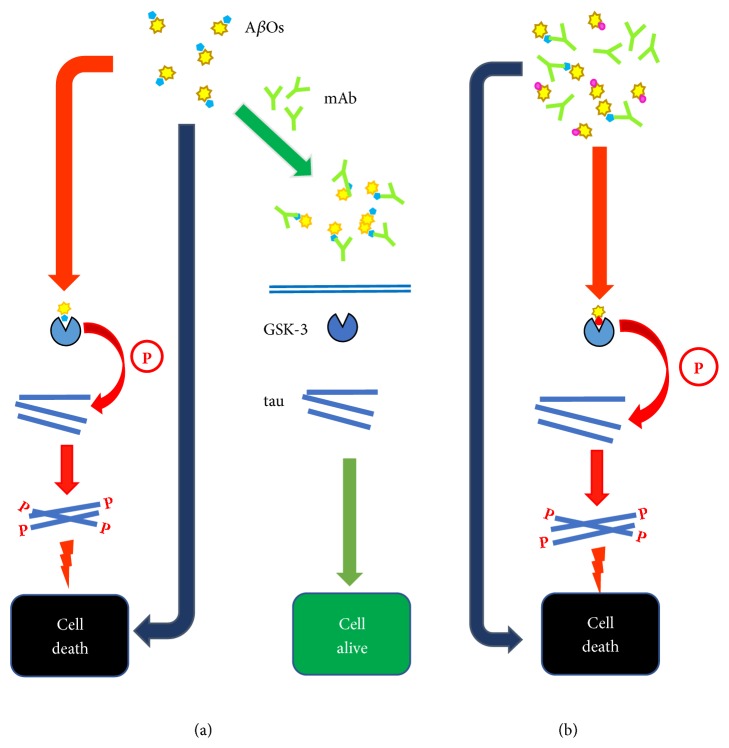

Since the polymorphic AβOs may show a diversity of pathological effects, it would be advantageous if the immunogen presents to the immune system an array of Aβ conformers responsible for those effects, to induce a broad antibody response. Indeed, it has been suggested that similar to vaccines against pathogens, the various Aβ conformational epitopes are comparable to strains showing different neurotoxicity [38, 89]. The presence of different conformational epitopes would explain the polymorphism and various pathophysiological effects of AβOs of similar size [85]. From the available information, it is evident that small AβOs, e.g., dimers, to tetramers, are extremely cytotoxic and serve as building blocks for larger oligomers [85]. The complex composition of Aβ based immunogens is confirmed by reports of cell membrane disruption by AβOs and the structural characteristics of oligomers with increased affinity for cell membranes [90]. Hence, it is obvious that immunogens derived from the Aβ1-15 region cannot produce the conformers needed to induce a protective anti-Aβ antibody response capable of neutralizing the various cytotoxic AβOs (Figure 1(b)). This conclusion must also apply to passive immunotherapy, where mAbs recognize a single epitope (Figure 2). This limitation may be minimized by using a combination of mAbs against diverse epitopes, a costly solution.

Figure 2.

Effects of mAbs targeting AβOs on their neurotoxicity. (a) Neurocytotoxic AβOs cause damage by acting at the neural cell membrane level and upon uptake, intracellularly (red arrows). But AβOs also amplify their cytotoxicity by activating tau kinases, e.g., GSK-3, which hyperphosphorylate tau (blue rods). Like Aβ, the aberrant phosphorylated tau (P) forms oligomers that are cytotoxic; but, the mechanism(s) by which tau-P causes neurodegeneration is still unclear. The AβOs' damaging effects may be prevented by mAbs (green), which upon binding to AβOs block the conformational epitopes responsible for cytotoxicity and activation of tau kinases. This situation would explain the near-term benefits achieved by using mAbs like aducanumab. (b) The presence of AβOs as various conformers having different epitopes explains why the protection provided by mAbs against AβOs is limited to near-term. While some cytotoxic AβOs are being neutralized by the administered mAbs (green), new ones showing diverse epitopes (magenta) and thus able to escape neutralization by those mAbs are being produced. However, these new AβOs are cytotoxic and hence able to damage neural cells (red arrows), as the previously neutralized AβOs. Consequently, the development of these new populations of cytotoxic AβO conformers (magenta) would explain why the protective effects of mAbs, e.g., aducanumab, are limited in duration.

Therefore, effective immunogens based on AβOs should have a composition that includes various oligomeric forms presenting different conformers. Although the methods to prepare those oligomers, i.e., recombinant DNA technology and organic synthesis, are available, the challenge would be to produce them in a reproducible manner to elicit a useful immune response against a set of dominant AβOs, a difficult task as proven by the fact that the polymorphism of different AβO preparations largely depends on the making and purification of the Aβ42 polypeptide [91]. Because of the effects of excipients on the immunogen and adjuvant properties, utmost care must be taken in their selection to avert injurious situations like those observed with the AN1792 vaccine [12, 48]. Finally, characterization of the immunogen must employ methods like electron microscopy, NMR, and X-ray crystallography to assess the conformation of the multiple AβOs [92].

5.2. Adjuvant's Role on the Immune Response

Adjuvants by acting on DCs and T-cells modulate the immune response to a proinflammatory Th1/Th17 or anti-inflammatory Th2 immunity. An effective AD vaccine must elicit a sole anti-inflammatory Th2 immunity, to avert damaging inflammatory T-cell mediated autoimmune responses, like those induced by the AN1792 vaccine. This requirement resembles that for vaccines against T-cell mediated autoimmune diseases, which also need a sole anti-inflammatory immunity [93]. Therefore, an obstacle in AD vaccine development has been that the available adjuvants, e.g., QS-21, CpG DNA, monophosphoryl lipid A and dsRNA, are mainly TLR ligands that stimulate a proinflammatory Th1/Th17 immune response, irrespective of the presence of T-cell epitopes in the immunogen [30, 31, 34]. A fact that is seldom recognized in AD vaccine development is that the adjuvants used in the current AD vaccines are largely proinflammatory ones (Table 1). Hence, vaccination methods that may not need adjuvants are being investigated, like DNA vaccines, where the immunogen is administered as a DNA gene encoding for the Aβ antigen [94]. After a transient transfection, the body's cells express the Aβ, inducing a noninflammatory immune response against toxic Aβ, a response that also reduces tau pathology [94]. While promising, a problem might be the deteriorating effects of immunosenescence on the immune system; i.e., the DNA vaccine's efficacy against infectious agents decreases in aged mice [79]. This immune decline may be ameliorated by coadministration of the adjuvant CpG ODN, as shown in aged mice. But, CpG DNA preferentially promotes a Th1 differentiation, which is proinflammatory and damaging in the case of AD [95].

Another approach to AD vaccines is the ex vivo use of DCs sensitized by an Aβ42 having mutated T-cell epitopes. Unlike normal Aβ42, an Aβ42 having mutated T-cell epitopes can induce an antibody response without inflammation [96]. Because of their beneficial effects in AD transgenic mice and lack of proinflammatory side effects, the use of DCs as a vaccination method has been proposed to prevent or treat AD [96, 97]. This approach requires isolating the patient's DC precursor cells, which after ex vivo maturation and stimulation with the mutated Aβ, are reinjected back into the patient, a complex and costly method for use in large populations in a preventive mode. Yet, use of DCs seems to avert some of the problems associated with the classic AD vaccines, like inflammatory responses. Indeed, the DC's role in regulating the brain's inflammatory status and the advantages of DC-based vaccines to treat AD have been the subject of extensive discussion [98]. One conclusion is that DCs' function may be modulated by adjuvants, a strategy that may increase the efficacy of DC vaccines for AD therapeutic purposes.

Although alum has been considered a Th2 adjuvant and used as a safe anti-inflammatory adjuvant in some AD vaccines, it shares many properties with Th1 adjuvants [70]. Alum's mechanism of action is complex, involving Th1 and Th2 associated processes, inducing a state of so called proinflammatory preparedness [70, 71]. Actually, the type of immunity induced by alum, seems to depend on numerous factors [71]. This situation raises questions about its use in AD vaccines, alone or combined with other adjuvants [33, 34]. A valuable option is the use of sole Th2 adjuvants, like the fucosylated glycoside QT-0101 [34, 69], to boost the immunoresponse of DC-based vaccines and bias T-cell activation towards Th2 immunity [98]. In fact, any protein antigen attached to a fucosyl glycan, like LNFPIII, would bind the lectin receptor DC-SIGN on DCs [99], which acts as an endocytic receptor and deliver the immunogen for intracellular processing by DCs. Binding of a fucosyl residue to DC-SIGN would induce in DCs a tolerogenic phenotype, which biases the response towards Th2 immunity [82, 83]. Delivery of the immunogen to the same DC being activated by the fucosyl residue binding to DC-SIGN after repeated immunizations will favor the production of antibodies with enhanced neutralizing properties [100]. Also, use of adjuvant-immunogen complexes would allow the in vivo, rather than ex vivo, targeting of immunogens to maturing DCs, a process that would significantly improve vaccination and allow for its use at a large scale in a preventive mode.

The glycoside QT-0101 has some advantages over the other Th2 adjuvants. Because of its amphipathicity and detergent-like properties it should form complexes with protein antigens, which are stabilized by a combination of ionic/hydrophobic interactions. This characteristic eliminates the need for the covalent linking used with LNFPIII [99]. The formation of AβO/QT-0101 complexes could also help to preserve the structural integrity of the AβOs, by avoiding their further aggregation. In effect, similar to other saponin adjuvants, addition of a detergent, like polysorbate, to QT-0101 vaccine formulations, may alter its adjuvanticity [69]. Hence, the ability of QT-0101 to inhibit Th1/Th17 immunities while eliciting a systemic Th2 anti-inflammatory immunity [65, 69] would help to slow the neurodegenerative process that may be exacerbated by inflammatory signaling responses [101].

6. Outstanding Issues

Increasing evidence shows that plaque is a protection mechanism that immobilizes cytotoxic AβOs rather than a causative agent of AD. The fact that high brain plaque buildup occurs in normally cognitive aging people and that some AD related pathophysiological effects befall in the absence of plaque [15–17] questions the role of these structures in AD. Actually, the process of removing plaque by releasing damaging AβOs could aggravate the course of this disease. Thus, the assessment of plaque removal as an indicator of AD treatment efficacy should be reconsidered in view of the available information.

While the current evidence shows that soluble Aβ aggregates are the neurotoxic agents leading to AD, only two studies, aducanumab and BAN2401 [2, 4], have targeted these aggregates. With the exception of AN1792, AD vaccine development has been essentially focused on the Aβ1-15 region, despite the fact that antibodies against that region may aggravate AD [11]. Considering the convincing evidence indicating that AβOs, and not monomeric Aβ, induce the damaging effects linked to AD, it would be logical to reconsider the relevance of past vaccine studies in the development of preventive vaccines against AD.

Until recently, AD vaccine development has been largely based on the belief that immunogens lacking T-cell epitopes, e.g., antigens like Aβ1-15, can be used safely with adjuvants that induce a systemic proinflammatory immunoresponse. But this belief cannot be applied to AβOs since oligomer formation requires the entire Aβ amino acid sequence, including B and T-cell epitopes. Besides, a proinflammatory immune response will exacerbate the damaging effects associated with AD. Accordingly, a useful AD vaccine would require adjuvants that induce a sole anti-inflammatory Th2 immunity, while inhibiting without abrogating proinflammatory immunity, needed for protection against infectious agents and cancer. This constraint makes the identification of new sole Th2 adjuvants critical for the development of vaccines against AD and other proteopathies.

It is apparent that AD is a multifactorial syndrome that results from independent, age-related pathologies, which justifies the use of a multiprong therapy approach [84]. Thus, preventive immune therapies may include more than one target. A review of the potentially most important causative agents of AD shows that, besides Aβ, the tau protein is also critical. Indeed, the available information strongly suggests that immunotherapy is an effective option to deal with the effects of aberrant tau [89]. Hence, as it would be discussed here, the question is how to block the damaging effects of both the abnormal Aβ and tau forms to prevent and/or delay the onset of AD.

7. Discussion and Perspectives

The preliminary phase 2 encouraging near-term clinical results of AD immunotherapy with BAN2401 and aducanumab support the development of preventive vaccines against this disease. Vaccines that induce an anti-inflammatory Th2 immunity with production of neutralizing antibodies against the cytotoxic Aβ soluble aggregates to protect neural cells from death. An immunoresponse that none of the clinically tested vaccines were able to induce, despite the seemingly convincing results from transgenic mouse models [12]. Misleading results that led the development of vaccines and mAb immunotherapy to focus on the N-terminal region of the Aβ monomer rather than the most likely cause of AD, the AβOs. A condition aggravated by the vaccines' induction of a proinflammatory immunity, which would exacerbate the course of AD. Thus, effective AD vaccines will require adjuvants that induce a sole systemic Th2 anti-inflammatory immunity and immunogens that have the dominant cytotoxic conformers for presentation to the immune system [34].

Actually, the fucosylated glycoside QT-0101 has several advantages; its fucosyl residue can bind to DC-SIGN, inducing an intracellular signaling that biases the response to Th2 immunity, while inhibiting the proinflammatory Th1/Th17 immunities [65, 69]. A stable immunogen and QT-0101 complex would allow in vivo targeting of the immunogen to DC-SIGN and its uptake by receptor-mediated endocytosis, followed by its intracellular processing. This pathway would induce a systemic Th2 immunity with production of anti-inflammatory cytokines and antibodies that neutralize cytotoxic soluble Aβ aggregates. A response that would improve with repeated vaccinations, which favor the selection of higher-avidity antibodies with better neutralizing properties [102]. The immune response will be influenced by the adjuvant, particularly if it facilitates delivery of the antigen to DCs [100], as QT-0101 does. Like previous anti-Aβ antibodies, the newly induced antibodies would most likely remove plaque, regardless of their effects, underscoring the fact that plaque removal is a phenomenon unrelated to protection against AD.

Although AD vaccines have been considered as therapeutics, the age-associated immune decline and resulting disturbances in antibody production make that option unlikely. While patients' immune competence may be of no concern in mAb therapy, it is critical in vaccination, a situation complicated by the development of a damaging chronic inflammation associated with aging [103]. Thus, immunizations to boost natural immunity should start years before the immune decline that occurs by age 65 [104]. Most likely, earlier immunizations may be needed for those having known risk factors, like carrying the APOE4 gene and diagnosis of type 2 diabetes [105], which may develop AD before 65 years of age. A vaccine's effectiveness in overcoming immunosenescence will solely depend on the adjuvant component. Hence, effective adjuvants should ameliorate some of the changes caused by immunosenescence, like the loss of ligands and receptors on T-cells and DCs, and the capacity to deliver the costimulatory signals needed for T-cell activation [106]. While it is doubtful that vaccination would totally prevent the onset of AD, boosting the protective anti-AD immunity would most likely delay the onset of this disease by several years.

Although soluble Aβ aggregates play a critical role in AD development, the likely role of tau protein in this disease cannot be ignored. Current information shows a close but intricate relation between tau and Aβ, with potential synergy in causing neurodegeneration [107]. For instance, an abnormal phosphorylation of tau renders this protein neurotoxic [108], a modification induced by monomeric Aβ1-42 [109], which is more prone to oligomerization than the shorter Aβ1-40. Meta-analysis studies show that cognitive decline is more affected by the increase in phosphorylated tau than that of Aβ soluble oligomers [110]. It also validated that plaque or immobilized Aβ has no role in the cognitive decline, strengthening the opinion that plaque does not cause AD. Application of statistical methods indicates that AβOs have a strong influence in activating kinases for tau's phosphorylation [106, 110], most likely by increasing the activity of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3) [111]. An enzymatic step that would result in an amplification of tau's phosphorylation process, an expected outcome because enzymes are biological catalysts. This process may explain the long-term disappointing aducanumab phase 3 clinical results; i.e., while blocking of AβOs initially reduces tau phosphorylation, it cannot stop it (Figure 2(a)). Besides, Aβ's polymorphism [37, 38] may yield new conformers that cannot be blocked by aducanumab [37–39]; hence, they would be able to induce a damaging enzymatic tau phosphorylation (Figure 2(b)), a situation that may explain the lack of long-term AD protection in the presence of aducanumab, an observation that may apply to other mAbs.

That GSK-3 is under the control of soluble AβOs, reinforces the fact that their neutralization will halt the damaging tau's phosphorylation process (Figure 2(a)), an argument that supports the concept of a preventive vaccine to inactivate soluble AβOs, blocking a cascade of damaging events. Concerns regarding the use of phosphorylated tau as a therapeutic target stem from the fact that several tau phosphorylation sites are linked to its normal physiological role. To obviate this difficulty, Kovak et al. [112] identified an epitope unique to the aberrant tau forms which is phosphorylation independent. This epitope has been used to develop a vaccine that interferes with the tau-tau interactions essential for tau's pathological effects in AD. Considering the apparently close interactions among tau and Aβ and their potential synergism, an effective approach would be to block both of them, using mAb immunotherapy and/or vaccination, in order to prevent or delay the onset of AD.

It is estimated that by the year 2050 there will be worldwide 125 million AD cases, emphasizing the importance of developing an effective AD vaccine. Seventy-five percent of the world's cases are predicted to occur in developing countries from Asia and Latin America, while the incidence of AD in the developed countries is expected to stabilize or show a slight decrease [Prince MJ. World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia. London: Alzheimer's Disease International; 2015. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/worldreport]. Epidemiological data shows that the onset of AD in Latin Americans occurs on the average seven years earlier than in white Americans and that they also have a higher incidence of diabetes, which is an AD risk factor [113, 114]. Yet, many countries lack the public health infrastructure and financial resources needed for prevention/treatment campaigns based on mAbs, which are considered costly even in wealthier countries. An approach to deal with this crisis would be to develop preventive vaccines against AD that would induce neutralizing antibodies against the cytotoxic AβOs, rather than removing plaque and increasing the pool of cytotoxic Aβ soluble forms. By delaying the onset of AD, an effective vaccine would mitigate the negative impact of this disease on the socioeconomic fabric of many countries.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Dr. Robert A. Agler, from the Department of Public Health, The Ohio State University, for helpful discussions concerning Bayesian analysis in clinical trials. I am also thankful to Dr. Karina R. Marciani for helpful discussions and review of the article.

Conflicts of Interest

Dante Marciani is a founder, President, and Chief Scientific Officer of Qantu Therapeutics, Inc., a company developing proprietary adjuvants. He has several issued patents and applications covering the uses of acylated and deacylated Quillaja saponins as adjuvants for Alzheimer's disease and autoimmune disease vaccines.

References

- 1.Sterner R. M., Takahashi P. Y., Yu Ballard A. C. Active vaccines for alzheimer disease treatment. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2016;17(9):862.e11–862.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Topline results: 18 months of BAN2401 might work, Alzforum 2018, https://www.alzforum.org/news/research-news/topline-results-18-months-ban2401-might-work.

- 3.Selkoe D. J. Light at the end of the amyloid tunnel. Biochemistry. 2018;57(41):5921–5922. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbasi J. Promising results in 18-month analysis of alzheimer drug candidate. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2018;320(10):p. 965. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panza F., Lozupone M., Dibello V., et al. Are antibodies directed against amyloid-β (Aβ) oligomers the last call for the Aβ hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease? Immunotherapy. 2019;11(1):3–6. doi: 10.2217/imt-2018-0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Budd Haeberlein S., O'Gorman J., Chiao P., et al. Clinical development of aducanumab, an anti-Aβ human monoclonal antibody being investigated for the treatment of early Alzheimer's disease. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer's Disease. 2017;4(4):255–263. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2017.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Dyck C. H. Anti-amyloid-β monoclonal antibodies for Alzheimer’s disease: pitfalls and promise. Biological Psychiatry. 2018;83(4):311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambert M. P., Barlow A. K., Chromy B. A., et al. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1-42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(11):6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cline E. N., Bicca M. A., Viola K. L., Klein W. L. The Amyloid-β Oligomer Hypothesis: Beginning of the Third Decade. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2018;64(1):S567–S610. doi: 10.3233/JAD-179941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambert M. P., Viola K. L., Chromy B. A., et al. Vaccination with soluble Aβ oligomers generates toxicity-neutralizing antibodies. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2001;79(3):595–605. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu Y. H., Bu X. L., Liang C. R., et al. An N-terminal antibody promotes the transformation of amyloid fibrils into oligomers and enhances the neurotoxicity of amyloid-beta: the dust-raising effect. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2015;12(1):p. 153. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0379-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marciani D. J. Rejecting the Alzheimer's disease vaccine development for the wrong reasons. Drug Discovery Today. 2017;22(4):609–614. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasilevko V., Xu F., Previti M. L., Van Nostrand W. E., Cribbs D. H. Experimental investigation of antibody-mediated clearance mechanisms of amyloid-β in CNS of Tg-SwDI transgenic mice. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(49):13376–13383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2788-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jimenez S., Navarro V., Moyano J., et al. Disruption of amyloid plaques integrity affects the soluble oligomers content from alzheimer disease brains. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114041.e114041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H.-G., Casadesus G., Zhu X., Takeda A., Perry G., Smith M. A. Challenging the amyloid cascade hypothesis: Senile plaques and amyloid-β as protective adaptations to Alzheimer disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1019:1–4. doi: 10.1196/annals.1297.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Treusch S., Cyr D. M., Lindquist S. Amyloid deposits: Protection against toxic protein species? Cell Cycle. 2009;8(11):1668–1674. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aizenstein H. J., Nebes R. D., Saxton J. A., et al. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. JAMA Neurology. 2008;65(11):1509–1517. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Busche M. A., Konnerth A. Impairments of neural circuit function in Alzheimer's disease. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2016;371 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0429.20150429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busche M. A., Grienberger C., Keskin A. D., et al. Decreased amyloid-β and increased neuronal hyperactivity by immunotherapy in Alzheimer's models. Nature Neuroscience. 2015;18(12):1725–1727. doi: 10.1038/nn.4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bai Y., Li M., Zhou Y., et al. Abnormal dendritic calcium activity and synaptic depotentiation occur early in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2017;12(1):p. 86. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0228-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shankar G. M., Li S., Mehta T. H., et al. Amyloid-β protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nature Medicine. 2008;14(8):837–842. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sevigny J., Chiao P., Bussière T., et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2016;537(7618):50–56. doi: 10.1038/nature19323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dodel R., Balakrishnan K., Keyvani K., et al. Naturally occurring autoantibodies against β-amyloid: Investigating their role in transgenic animal and in vitro models of Alzheimer's disease. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(15):5847–5854. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4401-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selkoe D. J., Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease at 25 years. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2016;8:595–608. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sehlin D., Englund H., Simu B., et al. Large aggregates are the major soluble Aβ species in AD brain fractionated with density gradient ultracentrifugation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032014.e32014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee M., Bard F., Johnson-Wood K., et al. Aβ42 immunization in Alzheimer's disease generates Aβ N-terminal antibodies. Annals of Neurology. 2005;58(3):430–435. doi: 10.1002/ana.20592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barghorn S., Nimmrich V., Striebinger A., et al. Globular amyloid β-peptide1-42 oligomer—a homogenous and stable neuropathological protein in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;95(3):834–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briney B., Sok D., Jardine J. G., et al. Tailored immunogens direct affinity maturation toward HIV neutralizing antibodies. Cell. 2016;166(6):1459.e11–1470.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zolla-Pazner S., DeCamp A., Gilbert P. B., et al. Vaccine-induced IgG antibodies to V1V2 regions of multiple HIV-1 subtypes correlate with decreased risk of HIV-1 infection. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087572.e87572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wisniewski T., Drummond E. Developing therapeutic vaccines against Alzheimer's disease. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2016;15(3):401–415. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2016.1121815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marciani D. J. Alzheimer’s disease: Toward the rational design of an effective vaccine. Revista de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 2015;78(3):140–152. doi: 10.20453/rnp.v78i3.2572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu Y., Xu Q. Prophylactic immunotherapy of Alzheimer's disease using recombinant amyloid-β B-cell epitope chimeric protein as subunit vaccine. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2016;12(11):2801–2804. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1197456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang C. Y., Wang P., Chiu M., et al. UB-311, a novel UBITh ® amyloid β peptide vaccine for mild Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2017;3(2):262–272. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marciani D. J. Alzheimer's disease vaccine development: A new strategy focusing on immune modulation. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2015;287:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang S., Liu D., Zhang L., et al. A vaccine with Aβ oligomer-specific mimotope attenuates cognitive deficits and brain pathologies in transgenic mice with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer's Research & Therapy. 2017;9(1):p. 41. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0267-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y.-X., Wang S.-W., Lu S., et al. A mimotope of Aβ oligomers may also behave as a β-sheet inhibitor. FEBS Letters. 2017;591(21):3615–3624. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deshpande A., Mina E., Glabe C., Busciglio J. Different conformations of amyloid β induce neurotoxicity by distinct mechanisms in human cortical neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(22):6011–6018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1189-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Fede G., Catania M., Maderna E., et al. Molecular subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease. Scientific Reports. 2018;8(1):p. 3269. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21641-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sengupta U., Nilson A. N., Kayed R. The role of amyloid-β oligomers in toxicity, propagation, and immunotherapy. EBioMedicine. 2016;6:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burki T. Alzheimer's disease research: the future of BACE inhibitors. The Lancet. 2018;391(10139):p. 2486. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coimbra J. R., Marques D. F., Baptista S. J., et al. Highlights in BACE1 inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease treatment. Frontiers in Chemistry. 2018;6:p. 178. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2018.00178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Du Y., Wei X., Dodel R., et al. Human anti-β-amyloid antibodies block β-amyloid fibril formation and prevent β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. Brain. 2003;126(9):1935–1939. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mengel D., Röskam S., Neff F., et al. Naturally occurring autoantibodies interfere with β-amyloid metabolism and improve cognition in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease 24 h after single treatment. Translational Psychiatry. 2013;3(3):e236–e236. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang T., Xie X., Ji M., et al. Naturally occurring autoantibodies against Aβ oligomers exhibited more beneficial effects in the treatment of mouse model of Alzheimer's disease than intravenous immunoglobulin. Neuropharmacology. 2016;105:561–576. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Britschgi M., Olin C. E., Johns H. T., et al. Neuroprotective natural antibodies to assemblies of amyloidogenic peptides decrease with normal aging and advancing Alzheimer's disease. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(29):12145–12150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904866106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Nuallain B., Williams A. D., McWilliams-Koeppen H. P., et al. Anti-amyloidogenic activity of IgGs contained in normal plasma. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2010;30(1):S37–S42. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9413-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Y. H., Giunta B., Zhou H.-D., Tan J., Wang Y. J. Immunotherapy for Alzheimer disease-the challenge of adverse effects. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2012;8(8):465–469. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marciani D. J. A retrospective analysis of the Alzheimer's disease vaccine progress—the critical need for new development strategies. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2016;137(5):687–700. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collins T. R. The hope, the hype, and cautious optimism around an anti-amyloid antibody that slows cognitive decline. Neurology Today. 2018;18(1):18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gupta S. Use of Bayesian statistics in drug development: Advantages and challenges. International Journal of Applied and Basic Medical Research. 2012;2(1):3–6. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.96789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Satlin A., Wang J., Logovinsky V., et al. Design of a Bayesian adaptive phase 2 proof-of-concept trial for BAN2401, a putative disease-modifying monoclonal antibody for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's and Dementia: Translational Research and Clinical Interventions. 2016;2(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang J., Logovinsky V., Hendrix S. B., et al. ADCOMS: A composite clinical outcome for prodromal Alzheimer's disease trials. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2016;87(9):993–999. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-312383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kastanenka K. V., Bussiere T., Shakerdge N., et al. Immunotherapy with aducanumab restores calcium homeostasis in Tg2576 mice. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2016;36(50):12549–12558. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2080-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tarasoff-Conway J. M., Carare R. O., Osorio R. S., et al. Clearance systems in the brain - Implications for Alzheimer disease. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2015;11(8):457–470. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ries M., Sastre M. Mechanisms of Aβ clearance and degradation by glial cells. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2016;8:p. 160. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Swanson C., Kaplow J. M., Mastroeni D., et al. Pharmacology of BAN2401: A monoclonal antibody selective for beta-amyloid protofibrils. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2013;9(4):P4–P286. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.05.1679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang Y., Le W. Differential roles of M1 and M2 microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecular Neurobiology. 2016;53(2):1181–1194. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-9070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bruhns P. Properties of mouse and human IgG receptors and their contribution to disease models. Blood. 2012;119(24):5640–5649. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-380121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kam T.-I., Song S., Gwon Y., et al. FcγRIIb mediates amyloid-β neurotoxicity and memory impairment in Alzheimer's disease. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2013;123(7):2791–2802. doi: 10.1172/JCI66827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dodel R., Rominger A., Bartenstein P., et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin for treatment of mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding trial. The Lancet Neurology. 2013;12(3):233–243. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70014-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cappellano G., Carecchio M., Fleetwood T., et al. Immunity and inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. American Journal of Neurodegenerative Diseases. 2013;2(2):89–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meraz-Ríos M. A., Toral-Rios D., Franco-Bocanegra D., Villeda-Hernández J., Campos-Peña V. Inflammatory process in Alzheimer's disease. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2013;7(7):p. 59. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Knight E. M., Kim S. H., Kottwitz J. C., et al. Effective anti-Alzheimer Aβ therapy involves depletion of specific Aβ oligomer subtypes. Neurology - Neuroimmunology Neuroinflammation. 2016;3(3) doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000237.e237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vellas B., Black R., Thal L. J., et al. Long-term follow-up of patients immunized with AN1792: Reduced functional decline in antibody responders. Current Alzheimer Research. 2009;6(2):144–151. doi: 10.2174/156720509787602852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heidari A. R., Boroumand-Noughabi S., Nosratabadi R., et al. Acylated and deacylated quillaja saponin-21 adjuvants have opposite roles when utilized for immunization of C57BL/6 mice model with MOG35-55 peptide. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 2019;29:68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hock C., Konietzko U., Streffer J. R., et al. Antibodies against β-amyloid slow cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2003;38(4):547–554. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Von Bernhardi R. Immunotherapy in Alzheimer's disease: Where do we stand? Where should we go? Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2010;19(2):405–421. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heneka M. T., Carson M. J., Khoury J. E., et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2015;14(4):388–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marciani D. J. New Th2 adjuvants for preventive and active immunotherapy of neurodegenerative proteinopathies. Drug Discovery Today. 2014;19(7):912–920. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.He P., Zou Y., Hu Z. Advances in aluminum hydroxide-based adjuvant research and its mechanism. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2015;11(2):477–488. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2014.1004026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kooijman S., Brummelman J., van Els C. A. C. M., et al. Novel identified aluminum hydroxide-induced pathways prove monocyte activation and pro-inflammatory preparedness. Journal of Proteomics. 2018;175:144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2017.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lemere C. A. Developing novel immunogens for a safe and effective Alzheimer's disease vaccine. Neurotherapy: Progress in Restorative Neuroscience and Neurology. 2009;175:83–93. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17506-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mandler M., Santic R., Gruber P., et al. Tailoring the antibody response to aggregated aβ using novel Alzheimer-vaccines. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115237.e0115237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Boeckler C., Frisch B., Muller S., Schuber F. Immunogenicity of new heterobifunctional cross-linking reagents used in the conjugation of synthetic peptides to liposomes. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1996;191(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Delrieu J., Ousset P. J., Caillaud C., Vellas B. ‘Clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease’: immunotherapy approaches. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2012;120(supplement 1):186–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hull M., Sadowsky C., Arai H., et al. Long-term extensions of randomized vaccination trials of ACC-001 and QS-21 in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Current Alzheimer Research. 2017;14:1–13. doi: 10.2174/1567205014666170117101537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vandenberghe R., Riviere M.-E., Caputo A., et al. Active Aβ immunotherapy CAD106 in Alzheimer's disease: A phase 2b study. Alzheimer's and Dementia: Translational Research and Clinical Interventions. 2017;3(1):10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang C. Y., Finstad C. L., Walfield A. M., et al. Site-specific UBITh® amyloid-β vaccine for immunotherapy of Alzheimer's disease. Vaccine. 2007;25(16):3041–3052. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bode C., Zhao G., Steinhagen F., Kinjo T., Klinman D. M. CpG DNA as a vaccine adjuvant. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2011;10(4):499–511. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mirotti L. C., Alberca Custódio R. W., Gomes E., et al. CpG-ODN shapes alum adjuvant activity signaling via MyD88 and IL-10. Frontiers in Immunology. 2017;8:p. 47. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Davtyan H., Zagorski K., Rajapaksha H., et al. Alzheimer’s disease AdvaxCpG- adjuvanted MultiTEP-based dual and single vaccines induce high-titer antibodies against various forms of tau and Aβ pathological molecules. Scientific Reports. 2016;6(1) doi: 10.1038/srep28912.28912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gringhuis S. I., Kaptein T. M., Wevers B. A., Mesman A. W., Geijtenbeek T. B. H. Fucose-specific DC-SIGN signalling directs T helper cell type-2 responses via IKKε-and CYLD-dependent Bcl3 activation. Nature Communications. 2014;5, article 3898 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]