Abstract

We wish to share our experience in echocardiographic assessment of the course of the aortic arch, illustrating it with multiple examples of the majority of possible variants. The course of the aortic arch and its branches may be visualized using high parasternal and suprasternal views in sagittal and transverse planes. It is hardly ever possible to visualize the entire aortic arch on a single ultrasonographic section, particularly in the case of pathological variations. Echocardiography should be performed in a dynamic mode, as in the case of CT angiography or magnetic resonance, by gradually moving the ultrasound beam and following the position of subsequent aortic segments and branches on the screen. Due to disturbances in ultrasound propagation caused by air-containing tissues, such as the trachea, bronchi and lungs as well as bones (sternum and ribs), each evaluation of the entire arch requires the use of a higher number of echocardiographic views. The presented data show that echocardiographic detection of the main details of aortic arch anomalies is possible in practically all cases. In the case of patients considered for surgical treatment, all unresolved issues should be clarified with CT angiography or MRI, enabling 3 dimensional reconstruction of vessels and other thoracic structures. Knowledge of the main elements of an abnormal arch is crucial for proper planning of this type of examination; therefore the diagnostic process should be always initiated with echocardiography. Echocardiography is often sufficient to answer all clinical questions and finalize the diagnostic process.

Keywords: echocardiography, right-sided aortic arch, double aortic arch, vascular ring, aberrant subclavian artery

Introduction

Anomalies of the aortic arch are common and well-defined developmental abnormalities varying in anatomy and clinical importance(1–10). They may form vascular rings encircling the esophagus and the trachea, which may cause dysphagia and respiratory difficulties, or remain asymptomatic and thus undiagnosed or diagnosed accidentally. An unexpected course of mediastinal arteries may cause difficulties during cardiac, thoracic or laryngological surgeries, as well as during catheterization of large vessels and various types of interventions. Therefore, the anatomy of the aortic arch and its branches as well as pulmonary arteries should be precisely defined before any planned chest and neck procedures, even in the absence of symptoms suggestive of a conflict between the respiratory tract, esophagus and arteries.

Mediastinal vessels are obscured by bony structures of the chest and the aerated lung tissue/respiratory tract throughout most of their course, which makes ultrasound imaging difficult. Computed tomography (CT) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) allow for much more precise imaging. These techniques offer the possibility of obtaining 3-dimensional reconstructions, which accurately reflect anatomical details of vessels and their spatial relationships with other thoracic organs. It is worth emphasizing that CT/NMR is not necessary in all patients as preliminary vascular assessment may be performed with a completely non-invasive ultrasonography. Despite significant limitations, careful and systematic ultrasonography of mediastinal arteries allows for obtaining a clear anatomical picture of most of these vessels(2–9). The paper presents echocardiographic methodology used in the Echocardiographic Laboratory in the Department of Cardiology in the Medical University of Warsaw to assess the aortic arch and its potential abnormalities. The methodology is supported with exemplary images of different types of anomalies.

Anatomical variations of the aortic arch (AA) are due to the variable course of the aortic arch, the arrangement and the course of its branches and, finally, the course of the ductus arteriosus (DA) or the ligamentum arteriosum(1,2).

The most common types of aortic arch are as follows(1–3):

-

1.

Left aortic arch (LAA)

-

A.

Typical branches: the right brachiocephalic trunk (RBCT), the left common carotid artery (LCCA), the left subclavian artery (LSA) (other variants are also possible)

-

B.

An aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA)

-

a.

Ductus arteriosus (DA) from the descending aorta (AoDesc) to the left pulmonary artery (LPA)

-

–

three separate equal aortic arch branches

-

–

two branches: a trunk formed by the common carotid arteries and a separate left subclavian artery

-

–

-

b.

Ductus arteriosus (DA) from the anomalous right subclavian artery (ARSA) to the right pulmonary artery (RPA)

-

a.

-

C.

Left aortic arch, right descending aorta

-

A.

-

2.

Right aortic arch (RAA)

-

A.

Typical branches (mirror image of normal left aortic arch): the left brachiocephalic trunk (LBCT), the right common carotid artery (RCCA), the right subclavian artery (RSA)

-

a.

Ductus arteriosus (DA) from LBCT to LPA

-

b.

Ductus arteriosus (DA) from the descending aorta to LPA

-

a.

-

B.

An aberrant left subclavian artery (ALSA)

-

a.

DA from ALSA to LPA (Kommerell’s diverticulum)

-

b.

DA from AoDesc to LPA

-

c.

DA from AoDesc to RPA

-

a.

-

C.

Right aortic arch, left descending aorta

-

a.

Normal transverse aortic arch

-

b.

Hypoplastic transverse aortic arch

-

a.

-

D.

RAA and complex vascular anomalies

-

A.

-

3.

Double aortic arch (DAA)

-

A.

Two patent aortic arches

-

a.

Both arches with a similar lumen diameter (symmetric flow)

-

b.

One of the arches significantly narrowed (hypoplastic)

-

a.

-

B.

One of the arches obstructed (or atretic)

-

A.

-

4.

Rare aortic arch anomalies

-

A.

Cervical aortic arch (CAA)

-

B.

Double lumen aortic arch (DLAA)

-

A.

Imaging of the left aortic arch

A thorough discussion on the imaging of proper ultrasonographic aortic arch anatomy seems to be crucial for understanding the differences found in other types of aortic arches.

Normal variant with typical successive branches: the right brachiocephalic trunk (RBCT), the left common carotid artery (LCCA), the left subclavian artery (LSA)

In this case, the ascending aorta runs upward from the aortic valve, which is located centrally in the heart, along the left sternal edge; then it curves posteriorly and left-wards, thereby forming the transverse part of the arch, after which it passes downward towards the abdominal cavity, along the left edge of the thoracic spine. The ascending part anteriorly crosses the right pulmonary artery. The superior vena cava runs parallel to this vessel, from the posterior and on the right side. The transverse part of the aortic arch usually gives rise to the right brachiocephalic trunk (RBCT), followed by the left common carotid artery (LCCA) and the left subclavian artery (LSA). The transverse part of aortic arch is usually crossed from above by the left brachiocephalic vein. The initial segment of the descending aorta, known as the isthmus, is a short segment between LSA and the aortic orifice of the ductus arteriosus (DA), which is already closed at the time of examination in a vast majority of patients and remains in the form of ligamentum arteriosum for the rest of life, which is of great importance in the case of a different course of the aortic arch than the one described above. Just below the origin of the DA, the descending aorta is anteriorly crossed by the left pulmonary artery (LPA) and the left main bronchus, which generates characteristic acoustic shadowing due to its location between the transducer and the aorta. In its further downward course, the aorta runs behind the wall of the left atrium and posteriorly crosses the left pulmonary veins.

Echocardiography is a two-dimensional imaging by its nature, which is the reason of the first difficulty in aortic arch imaging: the arch and its branches along with other mediastinal vessels are three-dimensional structures that are not arranged in one plain in the chest; therefore, it is not possible to capture them in a single image. A full assessment of aortic and pulmonary artery anatomy requires gradual, systematic following of the course of these vessels(2,4,5,9,11). The examination should begin with a suprasternal frontal view (Figs. 1 A–D), by positioning the ultrasound transducer in such a way so as to visualize the ascending aorta, optimally with the valve; then the ultrasonic beam should be moved upward, tilting the transducer down without changing its position. When moving the ultrasound beam, the course of aorta, which initially runs upwards with a slight rightward curve, then is directed leftwards and posteriorly, forming a pronounced convexity, gives off the left subclavian artery and runs downwards along the left edge of the thoracic spine, should be followed. Normally, aortic arch branches originate in its upper surface, from the major curvature. The first branch is the right brachiocephalic trunk, which is clearly wider than the other two, i.e. the left common carotid artery and the left subclavian artery. Further upward movement of the ultrasound beam makes it possible to follow the course of aortic arch branches, RBCT in particular, up to the division into the right subclavian artery and the right common carotid artery. In the initial phase of this scan (when analyzing the course of the ascending aorta), the relationships between the aorta and the right pulmonary artery and the pulmonary trunk, as well as the superior vena cava and right pulmonary veins should be evaluated. When analyzing the transverse part, the arrangement of branches and the relationships with neighboring veins (the brachiocephalic vein in particular) should be assessed, while the aortic isthmus, spatial relations with the ductus arteriosus, the left pulmonary artery and left pulmonary veins should be assessed as part of analysis of the descending portion.

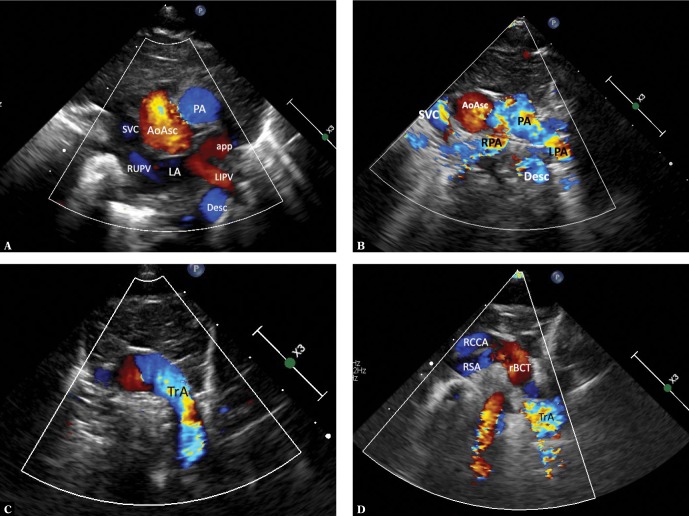

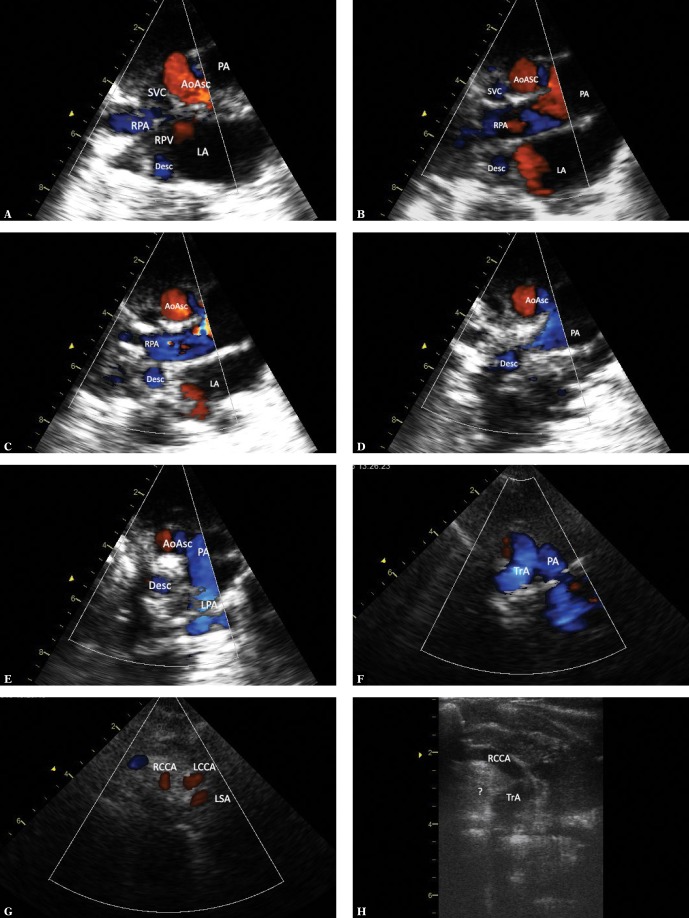

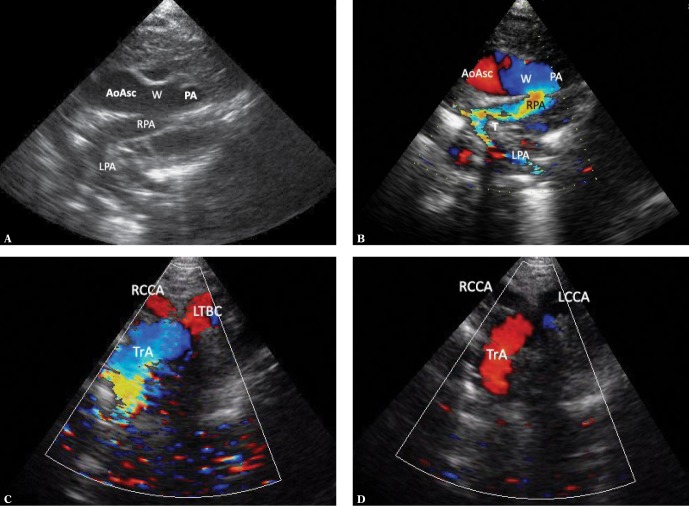

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound sections showing the thoracic aorta with left aortic arch in frontal and transverse planes. The images were obtained by gradually tilting the ultrasound beam (scan) from the frontal plane posteriorly and upwards, until reaching a horizontal plane: A. High para/suprasternal transverse view in a frontal-like plane. Centrally located ascending aorta is directed with its small convexity to the right; the upward flow is coded red. On the left – a transverse section of the pulmonary artery trunk (PA); below – the left atrium (LA) with visible orifices of the right upper (RUPV) and the left inferior pulmonary vein (LIPV) and the left atrial appendage (app). The left inferior pulmonary vein is posteriorly crossed by the descending aorta. B. A backward tilt of the ultrasound beam – to an intermediate plane between the frontal and horizontal planes. A transverse section of the upper segment of the ascending aorta (AoAsc) and, on its left, pulmonary artery trunk (PA) on the branching level and both branches (LPA and RPA) are visible. Superior vena cava (SVC) to the right of the aorta. The descending aorta (Desc) posteriorly crosses the left pulmonary artery at this level. C. Further, upward tilt of the ultrasound beam (up to the horizontal plane) visualizes the transverse part of the aortic arch (TrA), with its convexity characteristically directed to the left, slightly upwards and anteriorly; then it descends leftwards and posteriorly until reaching the anterior/left border of the thoracic spine. At this level, pulmonary arteries are no longer visible. D. Directing the ultrasound beam even higher shows branches of the arch, their typical arrangement and mutual proportions. For left aortic arch, the first branch is always directed to the right; in most cases this is the right brachiocephalic trunk (rBCT), clearly wider than the two vessels that follow, i.e. the left common carotid artery and the left subclavian artery; however, different anatomical variants are possible, including abnormalities, such as an aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA). Visualization of the division of the first aortic arch branch into two equal arteries almost certainly excludes ARSA

The precise analysis of left aortic arch anatomy, the measurements of the diameters of its individual segments in particular, should be performed in a suprasternal view showing the entire aortic arch (Figs. 2 A, B). However, it should be emphasized that this view rarely allows to clearly differentiate between left and right aortic arch or even double aortic arch variants.

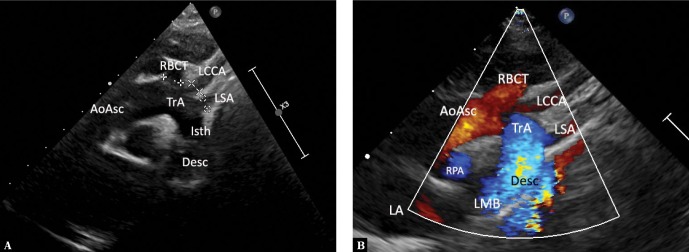

Fig. 2.

A typical left aortic arch en face. A. Normal, left aortic arch en face. High parasternal view (the transducer is placed just below the suprasternal notch, slightly to the right). Obtaining clear images is possible owing to the presence of conductive thymus an incomplete ossification of thoracic bony structures in an infant. The ultrasound beam directed obliquely so as to simultaneously visualize the ascending aorta, the aortic arch and the descending aorta as well as the branches of the arch. The right brachiocephalic trunk, which is wider than the other branches, is the first branch. AoAsc – ascending aorta, TrA – transverse aortic arch, Isth – isthmus, Desc – descending aorta, RPA – right pulmonary artery, LA – left atrium, LMB – acoustic shadow of the main left bronchus, RBCT – brachiocephalic trunk, LCCA – left common carotid artery, LSA – left subclavian artery. B. An analogous image with color-coded flow. Legends as in Fig. 1A

Following the course of aorta in sagittal-like planes (Figs. 3 A–D) may provide additional data. The scanning begins in high left parasternal view with the transducer tilted in such a way so as to visualize the ascending aorta along with the valve and the bulb; then the scan is gradually moved leftwards, which allows to investigate the course of aorta and its spatial relations with pulmonary arteries, trachea, pulmonary veins and the main bronchi.

Fig. 3.

Thoracic aorta in a patient with left aortic arch in sagittal-like parasternal views. The transducer located in the left parasternal line, slightly lower than in Fig. 1A and 1B (right-to-left scan). A. Ultrasound beam directed slightly rightwards, showing the ascending aorta (AoAsc) with the bulb. The right pulmonary artery (RPA) passes immediately behind the aorta. Other visible elements: left atrium (LA), right atrium with a fragment of its appendage (RA), an esophageal and tracheal shadow (Tr). B. A slightly more medial course of the ultrasound beam visualizes the initial segment of the transverse aortic arch and the initial segment of the brachiocephalic trunk (RBCT). Other legends as in Fig. 2A. C. A slight tilt of the transducer to the left of the medial plane with minimal rotation to the left visualizes the transverse aortic arch (TrA) and the initial segment of the descending aorta – the isthmus (Isth), as well as the pulmonary artery trunk (PA) and the initial segment of its left branch (LPA), which anteriorly crosses the descending aorta. D. A further slight tilt of the ultrasound beam to the left visualizes almost the entire descending aorta (Desc), as well as the distal segment of the aortic arch (TrA), the pulmonary artery (PA), the left upper pulmonary vein (LUPV) and the left ventricle (LV). The color-coded stream in the descending aorta is apparently interrupted at the level of the upper wall of the left atrium by an acoustic shadow produced by the left main bronchus (LMB), which anteriorly crosses the aorta and is located between the transducer and the aorta. The characteristic course of the individual aortic segments, which may be followed by performing maneuvers described in Fig. 2A, B and 3 A–D, is a decisive phenomenon for the assessment of aortic arch location and course. In the case of the left aortic arch, the aorta gradually travels to the front, rightwards and backwards, posteriorly crossing the left pulmonary artery. The characteristic convexity of the arch is directed to the left and upwards. The first branch, usually a wide brachiocephalic trunk, which divides after a short course, is directed to the right. In the case of the right aortic arch, the convexity of the arch is directed to the right, while the descending aorta remains on the right side of the chest and posteriorly crosses the right pulmonary artery, and the first branch is always directed to the left

The characteristic course of the individual aortic segments, which may be followed by performing maneuvers described in Fig. 2 A, B and Fig. 3 A–D, is decisive for the assessment of the location and course of the aortic arch. In the case of a left aortic arch, the aorta gradually travels on the screen from the right anterior aspect to the left posterior aspect, posteriorly crossing the left pulmonary artery. The characteristic convexity of the aortic arch is directed upward and to the left. The first branch – usually a wide brachiocephalic trunk, which divides after a short course, runs to the right. In the case of a right aortic arch, the convexity of the arch is directed to the right, with the descending aorta remaining on the right side of the chest and posteriorly crossing the right pulmonary artery, while the first branch always runs to the left.

An aberrant right subclavian artery (LAA, ARSA)

An aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA) is an anomaly in which the right subclavian artery arises directly from the aortic arch, following its branching into the left subclavian artery(1,2). It has a retroesophageal course and may potentially cause dysphagia and respiratory disorders(11–15); however, formation of a complete vascular ring is very rare (only when the DA connects ARSA with the right pulmonary artery)(2,11); therefore, clinical manifestations, usually in childhood, are very rare. Symptoms and complications are significantly more common in adults, mainly in elderly patients, which is due to atherosclerotic complications (aneurysm and/or ARSA dissection)(11–15). Patients with ARSA present with the course of the aortic arch which does not seem to differ from the one under normal conditions. Since the aberrant artery arises in the posteromedial aortic surface, its imaging in a typical suprasternal view is very difficult. Our experience indicates that the visualization of ARSA is easier in the high left parasternal view (Fig. 4 A, B), crossing the chest in a transverse-like plane (2D and color imaging). Since this is not a standard view, it is very easy to overlook ARSA, even when aortic arch anatomy is carefully assessed, particularly when examining a restless infant. A different branching pattern is a suggestive symptom(2,6): absence of a typical wide RBCT, instead there are three successive vessels with nearly identical diameters (Fig. 4 C), of which the first vessel is not divided; or, alternatively, a short trunk divided into two common carotid arteries is the first branch, while the left subclavian artery is the second branch.

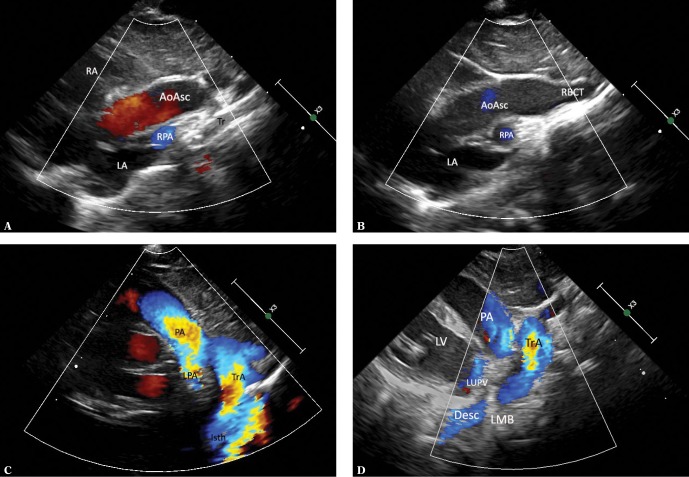

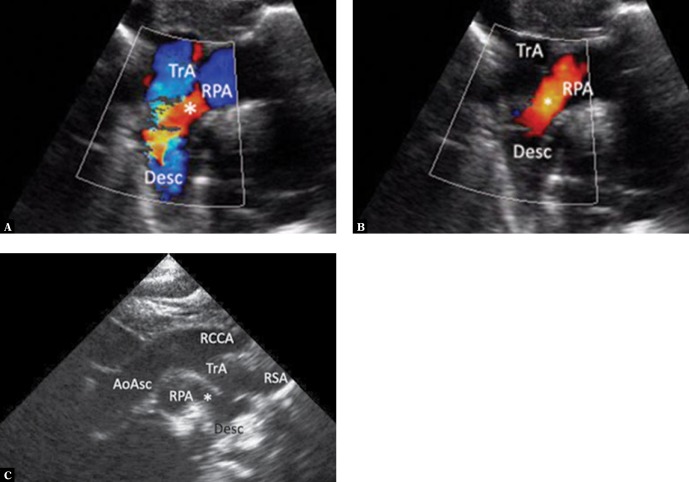

Fig. 4.

Imaging of the aortic arch in the case of the left aortic arch with an aberrant right subclavian artery. A. High parasternal view showing the upper mediastinum in the horizontal plane analogous to the image in Fig. 2B. The right subclavian artery (ARSA) passing to the right, anteriorly and upwards, arises from the posteromedial surface of the aortic arch (TrA). The color disappears at the level of crossing with the esophagus (E) and trachea as the ultrasound beam is completely reflected by the trachea. The ARSA segment located right to the trachea is situated higher; hence its visualization in the same image is impossible. LIV – left innominate vein. B. The same image without color coding. Also, the ARSA segment located immediately behind the esophagus was not visualized. C. Suprasternal view showing the aortic arch en face. Typical left aortic arch forming three branches. The absence of differences in the diameters of the subsequent arteries is noticeable. RCCA – right common carotid artery, LCCA – left common carotid artery, LSA – left subclavian artery. D. The image in this figure is substantially the same as in Fig. 4 C. Apart from a slightly elongated aortic arch, minor disproportion in the diameters of branches (the first branch is wider than the two subsequent branches), which could suggest a typical pattern, is noticeable. E. An analysis of the course of the first branch of the aortic branch could suggest normal arterial anatomy. In reality, the right common carotid artery (RCCA) formed the vertebral artery (VA). Other legends as in Fig. 4 C. F. In a view showing the apex of the aortic arch (TrA), an abnormal origin of the right subclavian artery (*) TrA was visualized in the horizontal plane. G. Another variant possibly indicating normal pattern of aortic arch branches. A trunk formed by both common carotid arteries is the first branch, followed by the left subclavian artery, while the right subclavian artery (invisible in this view) is the last branch. AoAsc – ascending aorta, TrA – transverse aortic arch, RCCA – right common carotid artery, LCCA – left common carotid artery, LSA – left subclavian artery. H. In the case of difficulty visualizing the distal part of the aortic arch, it is usually possible to visualize the peripheral, abnormal segment of ARSA. High right horizontal suprasternal or parasternal view enables following the course of ARSA between the clavicle and the trachea; the proximal segment disappears behind ultrasound-impermeable trachea and esophagus (E). The right common carotid artery runs almost parallel and anteriorly to ARSA. Legends: ARSA – anomalous (aberrant) right subclavian artery, RCCA – right common carotid artery, LCCA – left common carotid artery, LSA – left subclavian artery. I. ARSA in a child with aortic coarctation. Increased narrowing of the aortic isthmus. This view is not suggestive of an additional vascular anomaly. TrA – transverse arch, * – coarctation, PA – pulmonary artery trunk, AoDesc – descending aorta, LSA – left subclavian artery. J. A two-dimensional image in a horizontal plane clearly showing the distal part of the aortic arch “dragged” to the right, and atypical dilation of this segment, as well as the initial part of ASRA (*). K. Color Doppler shows flow directed to the right, which disappears behind the trachea – an image typical of ARSA, but very difficult to interpret due to respiratory artifacts. Legends as in previous figures

The lack of a clear disproportion between the first branch and subsequent branches of the aortic arch is relatively easy to detect and requires further, more detailed analysis. First of all, the course of the first arterial branch, which runs high, up to the neck without giving rise to the subclavian artery, but which only divides to the internal and external carotid artery. If an early division is visualized, it is almost certainly possible to exclude an aberrant artery; however it may happen that the common carotid artery untypically gives rise to the vertebral artery(2,13) (Fig. 4 D–G), which may mask ARSA. Detection of abnormalities is difficult due to the second variant of branching pattern, i.e. with the trunk composed of common carotid arteries. Since this is a relatively wide vessel, the image may appear normal, especially in a restless patient (Fig. 4 H).

If direct visualization of ARSA origin from the aorta is impossible, following the course of the right subclavian artery (RSA) from the periphery to the aorta may be of help. Under normal conditions, the RSA passes horizontally and arises relatively high from the RBCT. The ARSA runs from the level of the clavicle to the left and downward; therefore it is usually possible to visualize two parallel vessels – the upper located common carotid artery and the lower subclavian artery, which eventually disappears behind the lung apex and trachea (Fig. 4 J). Since an isolated ARSA is rarely the cause of significant clinical manifestations, the lack of diagnosis does not expose patients to complications; however, in the case of coexistence with some other heart defects, such as aortic coarctation (Fig. 4 I–K) or hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), it may significantly complicate the course of surgery, as in the case of defects requiring other thoracic surgeries. Therefore, a precise assessment of the aortic arch and its branches is necessary, especially when planning this type of surgery.

There was no case of a complete vascular ring in the course of ARSA (LAA, ARSA, DA from ARSA to RPA) in our material. If such a pathology occurs, increased flow in the para-aortic RSA segment causing its dilation is observed in fetal life, and compression on the esophagus and trachea, which may cause clinical manifestations, may occur after birth, especially after DA closure(2,11).

Left aortic arch with right descending aorta (LAA)

This is an extremely rare anomaly(2,16,17), in which the initial segment of the aortic arch shows a typical course (with a leftward convexity of the arch, RBCT or RCCA arising first); however, after giving rise to the left subclavian artery, the arch turns right and passes downwards after another crossing of the esophagus and the trachea. In addition to this crossing, the aorta may also give rise to the right subclavian artery (Fig. 5 A–H); isolated cases of a completely normal arrangement of aortic branches have also been described(2), however such branching patterns were not observed in our study.

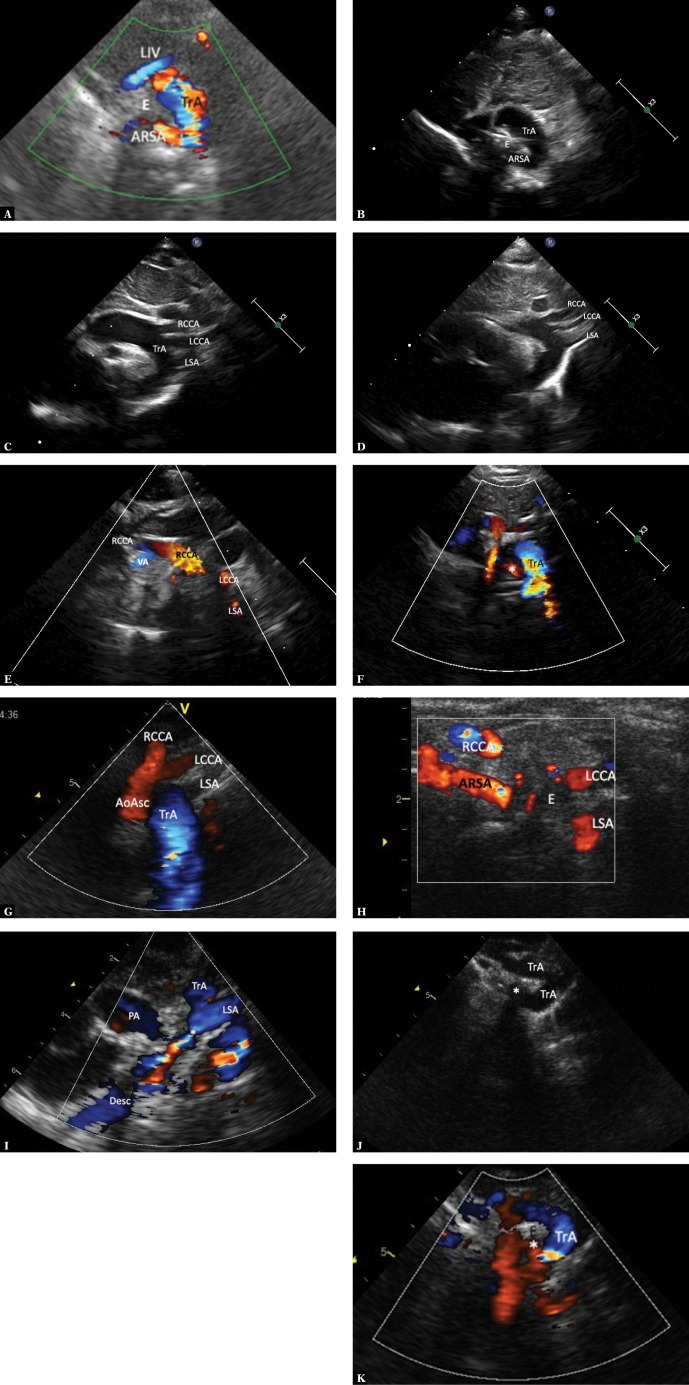

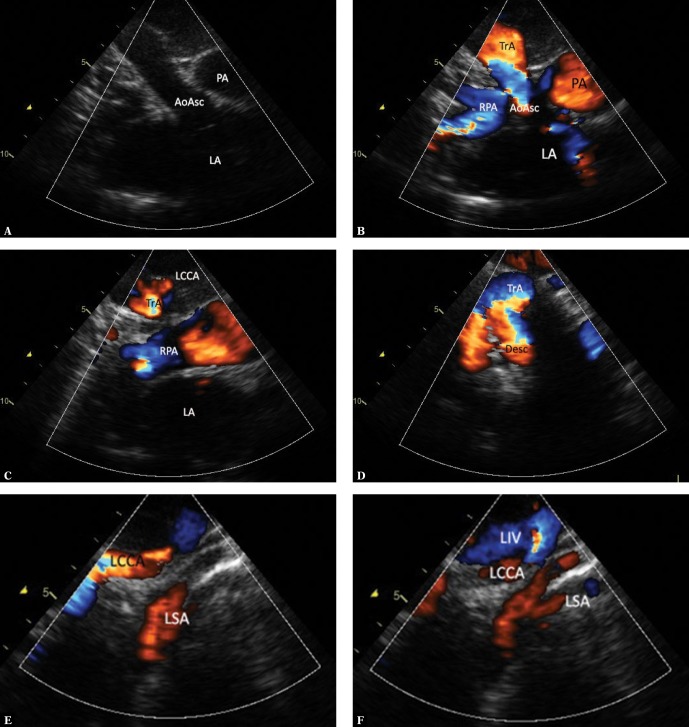

Fig. 5.

Imaging of the left aortic arch with the right descending artery. The images were obtained by gradually tilting the ultrasound beam posteriorly and upwards from the frontal plane until reaching a horizontal plane. A. Suprasternal view – frontal plane. Systolic phase. The ascending aorta (AoAsc) is seen in the centre, with the left atrium (LA) located below. The transverse section of the descending aorta (AoDesc) is seen behind the right wall of the left atrium, posteriorly from the orifice of the right pulmonary veins (RPV). Furthermore, the pulmonary artery trunk (PA) is located left to the aorta; on the right side – the superior vena cava (SVC) and a part of the right pulmonary artery (RPA). It is noteworthy that the descending aorta is located exactly posteriorly from the superior vena cava – to the right from the midline – a phenomenon typical of right aortic arch. B. Ultrasound beam shifted slightly more posteriorly and horizontally. Legends as in previous figures. At this level, the descending aorta is adjacent to the posterior wall of the right pulmonary artery and is also located exactly posteriorly from the SVC. C. A slightly more horizontal plane – legends as in previous figures. The descending aorta is slightly closer to the ascending aorta, which is now seen in a transverse section. D. Continued upward scanning – the descending aorta is located just below the right pulmonary artery and is gradually approaching the ascending artery, still on the right side of the midline. E. A nearly horizontal plane. It is only at this level that the untypically coursing left pulmonary artery (LPA) directed posteriorly instead of leftwards in its initial course is visible. Although the descending aorta is closer to the ascending aorta, it is still located on its right side. A strongly hyperechoic trachea is located between the ascending and descending aorta. F. A section at the level of aortic arch (TrA). The convexity of the aortic arch is directed to the left, which is typical of the left aortic arch. G. A cross-section at the level of arch branches. The first branch is directed rightwards, the two other branches are directed to the left. This pattern points to a left aortic arch. A similar diameter of these vessels is noticeable (the first vessel and the two other vessels have similar diameters); therefore, the presence of an aberrant right subclavian artery is very likely. RRCA – right common carotid artery, LCCA – left common carotid artery, LSA – left subclavian artery. H. The first branch of the aortic arch in the frontal plane passes to the right and upwards; since no division within this vessel was visualized, this is the right common carotid artery (RCCA). A hyperechoic area, which could correspond to an aberrant right subclavian artery (marked [?]), is visible in the distal part of the aortic arch; however, none of the obtained images could clearly confirm this assumption (respiratory artifacts prevented Doppler flow assessment in this region)

Right aortic arch (RAA)

The main characteristic is that the ascending and descending aorta are on the same side of the chest: the aortic arch encircles the right pulmonary artery and the right bronchus, while the descending aorta initially runs at the right spinal edge and is directed to the left side of the chest only after reaching a lower level(1). The first branch of the RAA is an artery running towards the left part of the chest; the left brachiocephalic trunk or the left common carotid artery. The occurrence of symptoms of tracheal and esophageal compression depends on the branching pattern and the course of the ductus arteriosus. The echocardiographic analysis of the direction of RAA should be analogous to the right aortic arch. Gradual movement of the ultrasound beam in the suprasternal view or high parasternal view showing the ascending aorta in the frontal plane visualizes the rightward aortic course, with the convexity of the arch directed upwards and to the right. The image of the first branch, which runs much more horizontally than in the case of the right trunk in the left aortic arch, is very characteristic. If the brachiocephalic artery (TBC) is the first branch, it is wide and its division into common carotid artery and subclavian artery may be easily visualized. In the case of an aberrant LSA, the diameter of the first aortic arch branch is very small; after a short horizontal course it is arched upwards without forming any branches. The aortic arch first gives rise to RCCA followed by RSA. The RAA is crossed from above by the left brachiocephalic vein (in extremely rare cases it may run under the arch). The ascending aorta anteriorly crosses the right pulmonary artery (RPA); the superior vena cava runs typically, parallel to this vessel. The descending aorta also crosses thorough the RPA (posteriorly) and the right pulmonary veins (also posteriorly) (Fig. 6 A–F).

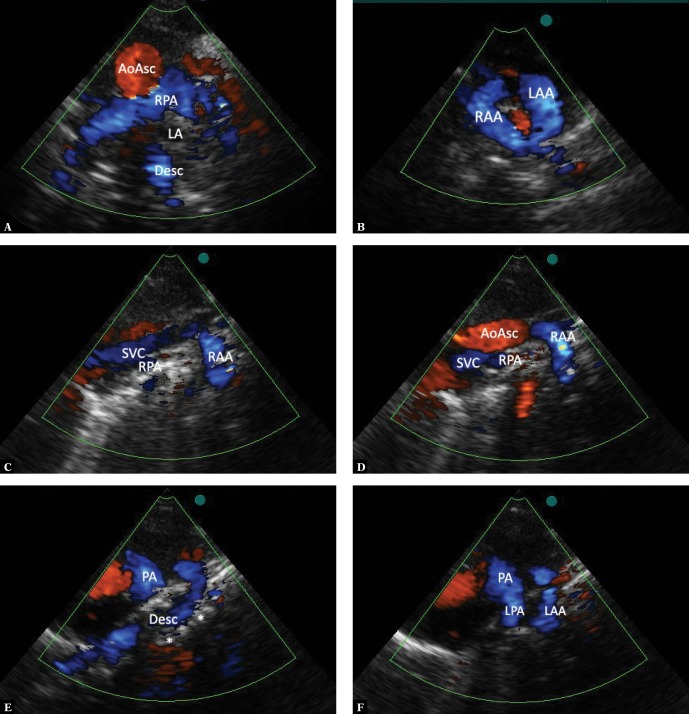

Fig. 6.

Imaging of the right aortic arch. A. A suprasternal view, mediastinal section in the frontal plane. Diastolic phase. Elements visualized: ascending aorta (AoAsc), pulmonary artery trunk (PA), left atrium (LA). B. The view and legends as in Fig. 5A, a slight posterior tilt of the ultrasound beam, systole. Elements that are still visible: ascending aorta up to the apex of the transverse aortic arch, pulmonary trunk, the right pulmonary artery crossing the ascending aorta, with its division into upper lobar artery, middle artery, and the left atrium. C. Further posterior movement of the ultrasound beam no longer shows the aorta; the right pulmonary artery and the pulmonary trunk, as well as the transverse part of the aortic arch along with the first, leftward branch are still visible. It is difficult to decide in this view whether this is the left brachiocephalic trunk or the left subclavian artery. D. A definite backward tilting of the transducer shows the right aortic arch with its convexity directed to the right and the initial segment of the descending aorta. E. A wide, strong tracheal shadow significantly obscures the descending aorta; therefore, precise assessment of its lower segment in the image from the previous figure is not possible. Slight parallel movement of the transducer to the left visualizes both the longer segment of the first arch branch – a relatively narrow and arched upwards left common carotid artery (LCCA) – as well as the left subclavian artery (LSA) emerging from the tracheal acoustic shadow, initially wide and narrowing towards the periphery. The image is indicative of the presence of an aberrant left subclavian artery, arising from the descending aorta. F. Continued movement to the left allows following further course of the left branches of the aortic arch. LIV – left innominate vein

Differentiation between RAA variants

RAA with left brachiocephalic trunk (RAA, LBCT)

Ductus arteriosus from LTBC or LSA

In this case, no vascular ring is formed – the ductus runs forward and to the left from the trachea(2,18–24). In our material, this type was observed in a vast majority of patients with tetralogy of Fallot or pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect (VSD), which corresponds to literature data(18–20). The ECHO shows a first wide horizontal branch of the aortic arch (the left brachiocephalic trunk, LBCT), which, after a short course, divides into LCCA and LSA. In the case of patent DA, an increased continuous flow may be seen in the LBCT; it is not uncommon to visualize the downward flow (from the pulmonary trunk) in the ductus arteriosus (Fig. 7 A–G). In such cases, the visualization of RAA and its branching pattern are important when planning Blalock-Taussig shunt (location of choice – opposite to the descending aorta), while the assessment of DA patency and course is of importance for both neonatal treatment in patients with duct-dependent pulmonary circulation, as well as for the course of total correction.

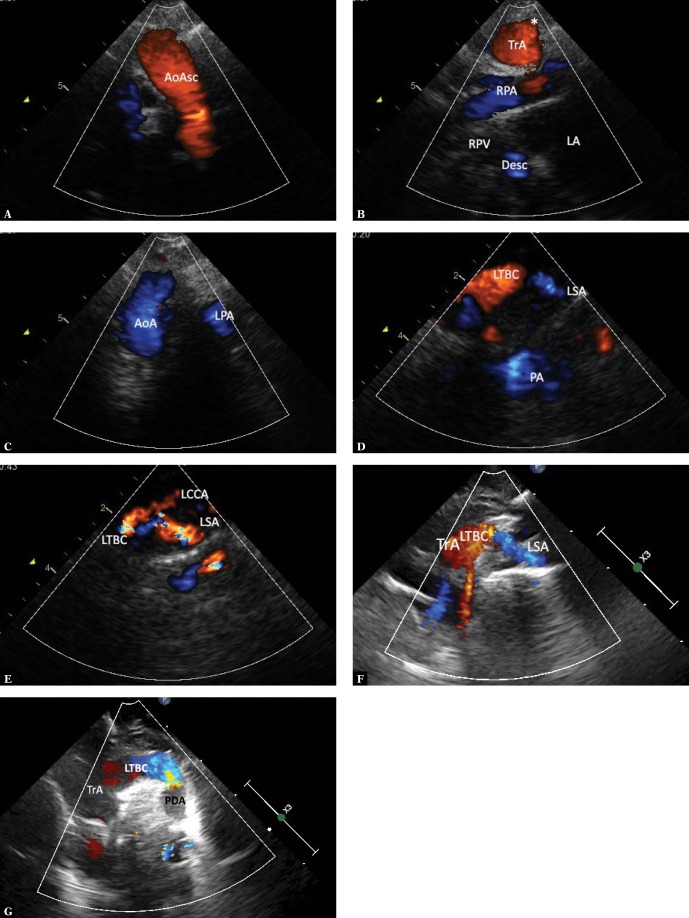

Fig. 7.

RAA with the brachiocephalic trunk forming the ductus arteriosus to LPA (most often the tetralogy of Fallot and pulmonary valve atresia with VSD). A. The view as in Fig. 5A (frontal plane). Systolic phase, the upward flow in the ascending aorta (AoAsc) is visible. B. Slight posterior movement of the ultrasound beam allows visualizing the right pulmonary artery with its division into upper lobar and middle artery, the transverse aortic arch at the site of first branch formation, as well as the middle segment of the descending aorta (Desc), which passes behind the left atrium (LA), posteriorly crossing two right pulmonary veins (RPV). C. Further posterior tilt of the ultrasound beam visualizes the transverse portion of the right aortic arch (AoA) with typical rightward convexity. Also, a small fragment of the left pulmonary artery (LPA) is visible. D. A slight movement of the transducer to the left is usually needed for a more detailed visualization of the first branch, which in this case is the left brachiocephalic trunk (LBCT). The left subclavian artery (LSA) runs on the left and slightly downwards from the trunk; visualization of the left common carotid artery often requires further movement and/or rotation of the transducer. E. A further slight movement of the transducer to the left allows to visualize LTBC division into LCCA and LSA. F. A newborn with pulmonary trunk atresia and VSD – ductus-dependent pulmonary circulation. Frontal-like plane section. Systole. The middle segment of the aortic arch (TrA), which forms a wide left brachiocephalic trunk (LTBC), which in turn gives rise to the left subclavian artery (LSA), is shown. The left common carotid artery is not visible in this figure. G. A slight posterior tilt of the transducer shows the initial segment of a tortuous ductus arteriosus (PDA) – which is too large fit in one plane

Ductus arteriosus from the descending aorta, running to the initial segment of the left pulmonary artery

The paraaortic portion of the duct forms a wide Kommerell’s diverticulum, which, together with a tight ligamentum arteriosum, completes the vascular ring and usually causes significant compression of the trachea(10,19,21–24) (Fig. 8 A–C).

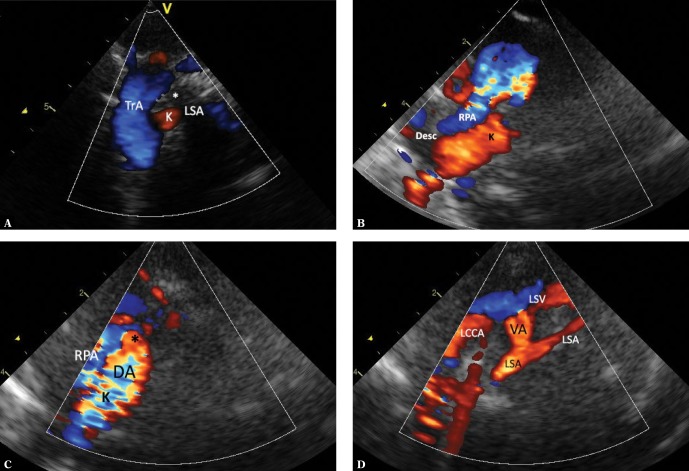

Fig. 8.

RAA with brachiocephalic trunk, the ductus arteriosus arising from the descending aorta and passing to LPA. A. A view showing the transverse portion of the aortic arch (TrA) with a clear rightward convexity. A very wide and short left brachiocephalic trunk dividing into a horizontal left subclavian artery (LSA) and the left common carotid artery (LCCA), which bends upwards. The distal part of the aortic arch is deformed by a wide Kommerell’s diverticulum (K), which is largely obscured by the trachea (*). B. A view showing the right aortic arch in a similar way as in Fig. 1A. Color-coded flow; however, branches of the aortic arch are not visible. C. A view showing the ascending aorta (AoAsc) in a sagittal plane. The trachea (*) is located just behind the aorta, slightly above the crossing with the right pulmonary artery (RPA), significantly deformed by a hyperechoic structure – the Kommerell’s diverticulum (K)

Ductus arteriosus from the descending aorta to the right pulmonary artery

In this form, no vascular ring is formed as the DA remains on the same side of the spine and is practically impossible to diagnose after DA closure. The isolated form of the anomaly is asymptomatic (Fig. 9 A–C). This type may also coexist with aortic coarctation and tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary valve atresia(2).

Fig. 9.

RAA – the ductus arteriosus from the descending aorta to the right pulmonary artery. A. Suprasternal view, frontal view; systole. The descending aorta (Desc) connects to the right pulmonary artery (RPA) via a wide vessel (*) with flow visible during both systole and diastole – a typical feature of the ductus arteriosus. B. The view and legends as in Fig 10 A. Diastole. Flow limited to the DA. C. A high right parasternal view, a section in the sagittal-like plane. Visible elements: the ascending aorta (AoAsc), the aortic arch (TrA), the right common carotid artery (RCCA), the right subclavian artery (RSA), the ductus arteriosus (*) arising from the descending aorta (Desc) and connecting to the right pulmonary artery (RPA)

An aberrant left subclavian artery (ALSA)

This type of RRA also has several variants, with the course of the ductus arteriosus being the primary differentiating factor, which also determines the clinical presentation.

An aberrant left subclavian artery (ALSA) giving rise to the ductus arteriosus

The ALSA segment between the aorta and the origin of the ductus is wide as a result of increased fetal flow, and is referred to as the Kommerell’s diverticulum(1,2,10,11,14,16,18,19,24–27). Along with the ductus (ligamentum) arteriosus, which connects to the pulmonary trunk near the origin of the left pulmonary artery, it completes the vascular ring, causing compressive symptoms. During the period of DA patency, the initial retrotracheal segment of ALSA is easier to visualize as it carries a large blood volume. Once the DA is closed, LSA perfusion drops; therefore it is difficult to visualize, especially in the proximal segment, which is obscured by the trachea. Since ALSA is very common in the right aortic arch, this anomaly should be always sought in RAA. The presence of a first narrow branch which runs in an arch directed upwards and forms no branches makes the diagnosis easier (Fig. 10 A–D).

Fig. 10.

RAA ALSA Kommerell’s diverticulum. A. A horizontal mediastinal section showing the right aortic arch (TrA) and its final branch – the left subclavian artery (LSA) located retrotracheally in its initial segment (*), which makes it very difficult to visualize its course. B. A slight parallel downward movement of the transducer allows for more precise visualization of the initial, wide segment of the left subclavian artery (Kommerell’s diverticulum – K) arising from the distal portion of the aortic arch (Desc; it runs approximately parallel, slightly above the right pulmonary artery – RPA). Furthermore, a transverse section of the pulmonary trunk is visible. C. The ductus arteriosus (DA) is still patent, representing a nearly smooth continuation of the Kommerell’s diverticulum (K). The ductal orifice to the pulmonary trunk (*) and a fragment of the right pulmonary artery (RPA) are visible. D. A parallel leftward movement of the transducer shows the further course of the LSA, which becomes significantly narrower after forming the ductus. A division into the distal LSA and the vertebral artery (VA) is seen. The left common carotid artery (LCCA) and the left subclavian vein (LSA) are visible anteriorly to the LSA

An aberrant left subclavian artery (ALSA) – ductus arteriosus from the descending aorta to the left pulmonary artery

In this case, the LSA does not carry an increased blood volume and is not dilated during fetal life (Fig. 11 A–C). Other elements do not differ from the above described variant. Furthermore, the ductus (ligamentum) arteriosus completes the vascular ring and may cause compressive symptoms.

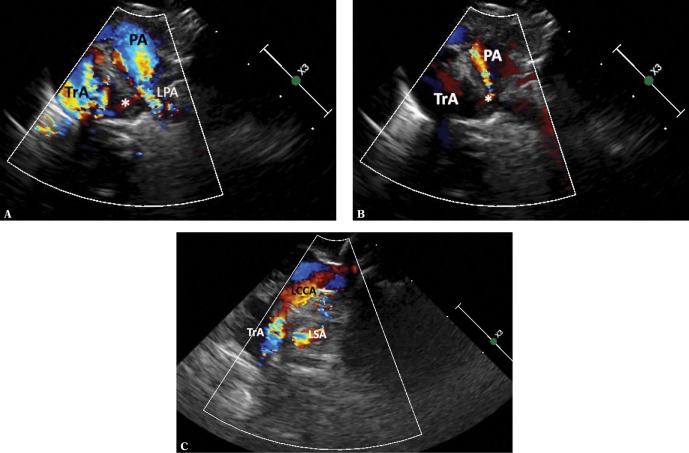

Fig. 11.

RAA with an aberrant subclavian artery, the ductus arteriosus arising directly from the descending aorta and connecting to the LPA. A. A high parasternal view showing the upper mediastinum in a transverse plane. Systole. Visible elements: the pulmonary artery trunk (PA), its left branch (LPA), distal transverse portion of the aortic arch (TrA). These vessels are coded blue. Red-coded flow in the ductus arteriosus (*) is seen between the descending aorta and the initial segment of the left pulmonary artery. The vascular structures form a complete vascular ring around the trachea and esophagus. B. View and legends as in Fig. 11 A. Diastole. Ductus arteriosus shunt into the initial segment of the left pulmonary artery and the pulmonary trunk is more visible during this phase of the cardiac cycle. C. A slight upward movement of the ultrasound beam visualizes both left-sided branches of the aortic arch: the left common carotid artery (LCCA) and the left subclavian artery (LSA), which arises separately from the distal part of the aortic arch

Right aortic arch with left descending aorta

In this case, the transverse part of the aortic arch first forms the left common carotid artery (the left brachiocephalic trunk in exceptional cases) and both right-sided branches, then it runs retroesophageally and retrotracheally and passes horizontally towards the left side of the chest, where it forms the left subclavian artery from a usually wide Kommerell’s diverticulum, after which it is directed vertically downwards, along the left spinal border(2,17,28). The Kommerell’s diverticulum also gives rise to the ligamentum arteriosus closing the vascular ring, which is usually loose and causes no evident compression (Fig. 12 A–C). It is worth noting that although the left subclavian artery meets the diagnostic criteria for an aberrant artery (it is the last branch of the right aortic arch), it has no retroesphageal course; therefore, it should not be referred to as retroesophageal (the term is often used for aberrant subclavian arteries). In this case, the transverse part of the right aortic arch has a retroesophageal course; cases of hypoplasia and even atresia of this segment have been described in literature(28).

Fig. 12.

RAA – the left descending aorta. A series of images from scanning in the suprasternal, frontal view. A. Systole. Visible are both blue-coded pulmonary arteries, the right pulmonary artery is crossed by the ascending aorta (AoAsc), and the initial segment of the transverse part of the aortic arch, which gives rise to its first branch – the left common carotid artery (LCCA) directed to the left and upwards. A pathognomonic picture for right aortic arch. B. A slight posterior tilt of the ultrasound beam. The ascending aorta is no longer visible. Only the transverse part of the aortic arch with the left common carotid artery is still visible. C. Further posterior movement of the ultrasound beam reveals a wide transverse part of the aortic arch (TrA), which is obscured by the tracheal acoustic shadow (T). The aortic arch is directed leftward, while the descending aorta has a typical course, on the left side of the chest. The right common carotid artery (RCCA) arises from the arch most to the right. The left subclavian artery (LSA) is the final branch of the aortic arch; therefore it meets the criteria for an aberrant artery. It should be emphasized that it has no retroesphageal course, which is present in a typical form of right aortic arch with left aberrant subclavian artery as it arises from the aorta following the intersection with the esophagus and trachea; therefore, it causes no compression of any of these structures

Complex vascular anomalies

The right aortic arch may occur in many configurations of vascular anomalies, e.g. in a child with an aortopulmonary window, pulmonary sling, persistent left superior vena cava and ventricular septal defect (Fig. 13 A–D).

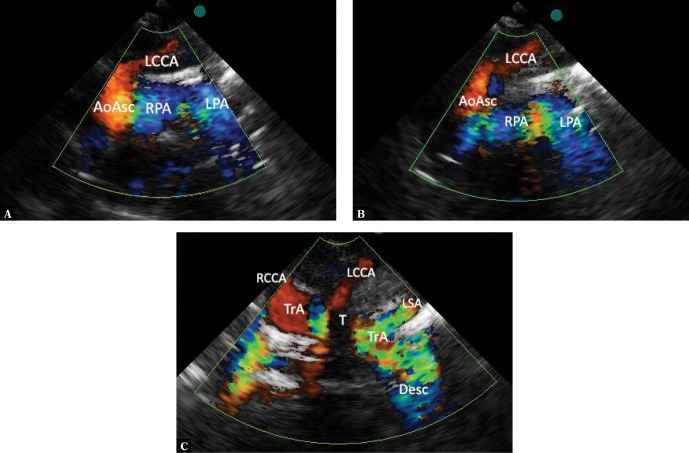

Fig. 13.

RAA, complex forms. A. High parasternal view showing large arteries in a transverse section. On the right – the ascending aorta (AoAsc), on the left – the pulmonary artery (PA), with no wall between these vessels – an aortopulmonary window (W). The pulmonary artery gives rise to only one artery, i.e. the right pulmonary artery (RPA) dividing (after a long course) into the left pulmonary artery (LPA), which passes in an arch to the left, and typically coursing right pulmonary artery (RPA). A hyperechoic trachea is seen on the left from the site of left pulmonary artery origin – the arrangement of pulmonary arteries is typical for pulmonary sling. B. View and legends as in Fig. 13A, color-coded flow, systole. C. A view showing the upper mediastinum in a transverse section. The aortic arch (TrA) with its rightward convexity is shown; the first branch (the brachiocephalic trunk) runs leftwards (LTBC) – a pathognomonic picture for right aortic arch. Limited flow in the aortic arch coded in blue – the flow is directed downwards, moving away from the transducer. D. The flow in the aortic arch is reversed during diastole (coded in red), which is due to significant steal into the aortopulmonary window

Double aortic arch (DAA)

Double aortic arch is a congenital vascular defect characterized by the persistence of both aortic arches (left and right). Both aortic arches connect to the ascending aorta from the anterior aspect, and with the descending aorta from the posterior aspect, thereby completely encircling the esophagus and trachea(1–10). Among all types of vascular rings, compression symptoms are most common in the double aortic arch(1–3,6–10,25–27). DAA variants with full patency of both arches, or where one arch (usually the left one) is narrower or completely atretic with a fibrous tissue band connecting the neighboring arch segments and completing the ring have been encountered(17–19).

DAA, preserved flow in both arches

An optimal visualization of the double aortic arch is achieved in suprasternal views and high parasternal views, which enable a simultaneous visualization of flow in both arches, especially when their diameters are similar (Fig. 14 A–F).

Fig. 14.

A double aortic arch with preserved flow in both branches: A. A suprasternal projection showing the mediastinum in an intermediate plane between the frontal and transverse plane. A cross-section of the ascending aorta (AoAsc), the right pulmonary artery (RPA) crossing it from behind, a part of the left atrium (LA), and the descending aorta (Desc) located in the midline, behind its posterior wall, are visible. B. An upward tilt of the ultrasound beam, reaching a horizontal plane, visualizes the double aortic arch with a nearly symmetrical flow in both branches (RAA and LAA). Figures C–F are a series of images obtained in a high left parasternal view by gradually moving the ultrasound beam right-to-left in a sagittal plane: C. Structures located most to the right: the superior vena cava (SVC), the right pulmonary artery (RPA), a convex (to the right) part of the right-sided branch of the aortic arch (RAA). The ascending and descending aorta are not visible. D. A slight leftward tilt of the ultrasound beam shows the ascending aorta (AoAsc), the right branch of the aortic arch, and only the lower (pericardial) segment of the inferior vena cava. E. Further leftward tilt of the beam shows the pulmonary artery trunk (PA), the distal part of the left aortic arch and the segment passing medially, anteriorly to the spine (*), and the descending aorta behind pulmonary trunk bifurcation. F. Even further leftward movement of the ultrasound beam shows a longer segment of the left pulmonary artery (LPA) and the left convex part of the aortic arch (LAA). Again, the descending and ascending aorta are no longer visible

DAA, with one arch hypoplastic or completely atresic

Flow visualization with color Doppler may be very difficult if not impossible in the case of significant hypoplasia (Fig. 15 A–D). In such cases, CT angiography or MRI may be of pivotal importance. It may be even much more difficult differentiating between double aortic arch with atretic left or right arch and brachiocephalic trunk as none of the currently available imaging modalities enables visualization of narrow tissue bands with no blood flow. A much more arched, posteriorly directed course of the patent part of the double aortic arch may be helpful in the differentiation(7,8,28–30). In most cases, only direct visualization by a cardiac surgeon makes it possible to establish a reliable diagnosis(2,10).

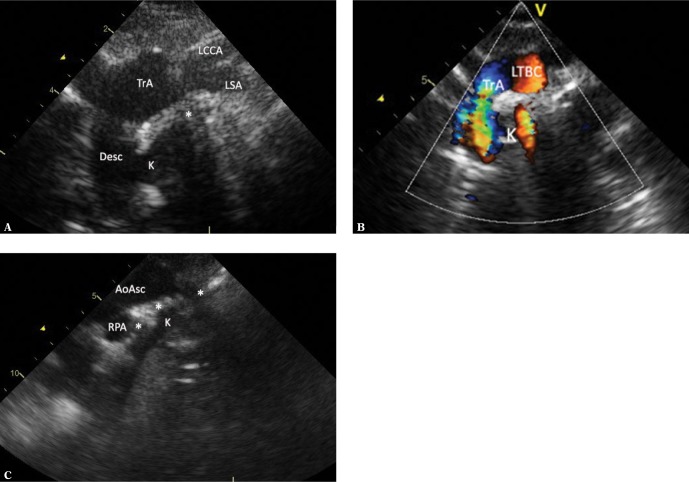

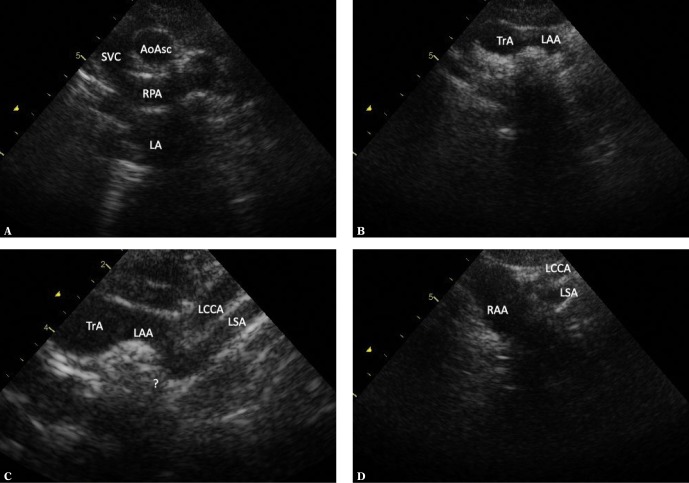

Fig. 15.

A double aortic arch with one of the segments being hypoplastic or atretic. The images were obtained by frontal-to-horizontal plane scanning: A. A suprasternal view, an intermediate plane between the frontal and horizontal plane. A cross-section of the ascending aorta (AoAsc), which is posteriorly crossed by the right pulmonary artery (RPA) is visible. The superior vena cava is seen on the right side of the aorta; the left atrium (LA) is located below and posteriorly to the RPA. The brachiocephalic vein is seen anteriorly and above the AoAsc. B. Horizontal plane: a wide vessel with a horizontal, leftward course is visible. C. An enlarged image for better visualization of the branch of the aortic arch from the previous image. A slight leftward and upward movement of the ultrasound beam shows the division of this vessel and its pronounced posterior curve. In particular, the more posteriorly located artery forms a pronounced pointed elbow. D. A slight rightward movement of the transducer shows a wide right aortic arch. It is not possible to show a vascular structure connecting the right aortic arch with elbow-like bended left subclavian artery

Conclusions

In our opinion, systematic ultrasonographic evaluation of the aortic arch and its branches allows for the detection of virtually all types of anomalies of the thoracic segment of the main artery. Innominate (brachiocephalic) artery syndrome, in which anterior tracheal compression due to untypical course of this vessel is observed, is an exception. Since the RBCT forms normally, i.e. as the first branch in the aortic arch, in such cases, there are no echocardiographic markers for the conflict between RBCT and the trachea. In the case of patients with a clinical picture indicative of mechanical obstruction located in the central respiratory tract, the diagnosis may be based on CT or NMRI and tracheoscopy. It should be noted that since the abnormally coursing artery in this syndrome is not adjacent to the esophagus, it does not cause its typical deformity seen in vascular rings. Normal appearance of the aortic arch and its branches makes it possible to exclude a classical vascular ring and confirm normal morphology of the pulmonary trunk – pulmonary sling. Depending on the patient’s symptoms, the obtained echocardiographic data may be sufficient for making therapeutic decisions. First of all, it is possible to exclude most anatomical anomalies of the aortic arch (as well as pulmonary arteries) and redirect the diagnostic process to other areas in symptomatic children. Secondly, in the case of aortic arch abnormalities detected in children with mild clinical symptoms or in whom the diagnosis was not associated with compressive symptoms and no surgical intervention is planned (and also for other reasons), there is no need for extended diagnosis. In the case of patients planned for surgical treatment, whether to divide the vascular ring and relieve the esophageal and tracheal compression or due to other thoracic abnormalities, CT or NMRI is needed for precise visualization of all vascular elements and their relationships with adjacent organs. These techniques are not limited by the impact of non-conductive tissues and allow for an excellent three-dimensional reconstruction of all thoracic organs. It is advisable to plan these diagnostic evaluations based on possibly accurate knowledge of the anomaly, which in turn may be acquired from a carefully performed ultrasonography.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors do not report any financial or personal connections with other persons or organizations, which might negatively affect the contents of this publication and/or claim authorship rights to this publication.

References

- 1.Edwards JE: Anomalies of the derivatives of the aortic arch system. Med Clin North Am 1948; 32: 925–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoo SJ, Bradley TJ: Vascular rings, pulmonary arterial sling, and related conditions. In: Anderson RH, Baker EJ, Redington A, Rigby ML, Penny D, Wernovsky G (eds.): Paediatric Cardiology. Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, PA: 2009: 967–989. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Godtfredsen J, Wennevold A, Efsen F, Lauridsen P: Natural history of vascular ring with clinical manifestations. A followup study of eleven unoperated cases. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1977; 11: 75–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murdison KA, Andrews BA, Chin AJ: Ultrasonographic display of complex vascular rings. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990; 15: 1645–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lillehei CW, Colan S: Echocardiography in the preoperative evaluation of vascular rings. J Pediatr Surg 1992; 27: 1118–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shanmugam G, Macarthur K, Pollock J: Surgical repair of double aortic arch: 16year experience. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2005; 13: 4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma G, Li Z, Li X, Peng Y, Du Z, Jin L et al.: Congenital vascular rings: a rare cause of respiratory distress in infants and children. Chin Med J 2007; 120: 1408–1412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leonardi B, Secinaro A, Cutrera R, Albanese S, Trozzi M, Franceschini A et al.: Imaging modalities in children with vascular ring and pulmonary artery sling. Pediatr Pulmonol 2015; 50: 781–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huhta JC, Gutgesell HP, Latson LA, Huffines FD: Twodimensional echocardiographic assessment of the aorta in infants and children with congenital heart disease. Circulation 1984; 70: 417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Backer CL, Mavroudis C, Rigsby CK, Holinger LD: Trends in vascular ring surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005; 129: 1339–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kouchoukos NT, Masetti P: Aberrant subclavian artery and Kommerell aneurysm: surgical treatment with a standard approach. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007; 133: 888–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atay Y, Engin C, Posacioglu H, Ozyurek R, Ozcan C, Yagdi T et al.: Surgical approaches to the aberrant right subclavian artery. Tex Heart Inst J 2006; 33: 477–481. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karcaaltincaba A, Haliloglu M, Ozkan E, Kocak M, Akinci D, Ariyurek M: Noninvasive imaging of aberrant right subclavian artery pathologies and aberrant right vertebral artery. Br J Radiol 2009; 82: 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kieffer E, Bahnini A, Koskas F: Aberrant subclavian artery: surgical treatment in thirtythree adult patients. J Vasc Surg 1994; 19: 100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kopp R, Wizgall I, Kreuzer E, Meimarakis G, Weidenhagen R, Kühnl A et al.: Surgical and endovascular treatment of symptomatic aberrant right subclavian artery (arteria lusoria). Vascular 2007; 15: 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hassan W, Omrani AA, Neimatallah M, Fadley FA, Halees ZA: Dysphagia lusoria caused by aberrant right subclavian artery, Kommerell’s diverticulum, legamentum ring, right descending aorta, and absent left pulmonary artery: a report of a unique vascular congenital disease undetected until adulthood and a review of the literature. Pediatr Cardiol 2005; 26: 851–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philip S, Chen SY, Wu MH, Wang JK, Lue HC: Retroesophageal aortic arch: diagnostic and therapeutic implications of a rare vascular ring. Int J Cardiol 2001; 79: 133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McElhinney DB, Hoydu AK, Gaynor JW, Spray TL, Goldmuntz E, Weinberg PM: Patterns of right aortic arch and mirrorimage branching of the brachiocephalic vessels without associated anomalies. Pediatr Cardiol 2001; 22: 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanne JP, Godwin JD: Right aortic arch and its variants. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2010; 4: 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craatz S, Künzel E, SpanelBorowski K: Rightsided aortic arch and tetralogy of Fallot in humans – a morphological study of 10 cases. Cardiovasc Pathol 2003; 12: 226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zachary CH, Myers JL, Eggli KD: Vascular ring due to right aortic arch with mirrorimage branching and left ligamentum arteriosus: complete preoperative diagnosis by magnetic resonance imaging. Pediatr Cardiol 2001; 22: 71–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han JJ, Sohn S, Kim HS, Won TH, Ahn JH: A vascular ring: right aortic arch and descending aorta with left ductus arteriosus. Ann Thorac Surg 2001; 71: 729–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao J, Liao Y, Gao S: Right aortic arch with retroesophageal left ligamentum arteriosum. Tex Heart Inst J 2006; 33: 218–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higashikuni Y, Nagashima T, Ishizaka N, Kinugawa K, Hirata Y, Nagai R: Right aortic arch with mirror image branching and vascular ring. Int J Cardiol 2008; 130: e53–e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kocis KC, Midgley FM, Ruckman RN: Aortic arch complex anomalies: 20-year experience with symptoms, diagnosis, associated cardiac defects, and surgical repair. Pediatr Cardiol 1997; 18: 127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruzmetov M, Vijay P, Rodefeld MD, Turrentine MW, Brown JW: Followup of surgical correction of aortic arch anomalies causing tracheoesophageal compression: a 38year single institution experience. J Pediatr Surg 2009; 44: 1328–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cinà CS, Althani H, Pasenau J, Abouzahr L: Kommerell’s diverticulum and rightsided aortic arh: a cohort study and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg 2004; 39: 131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oddone M, Granata C, Vercellino N, Bava E, Tomà P: Multimodality evaluation of the abnormalities of the aortic arches in children: techniques and imaging spectrum with emphasis on MRI. Pediatr Radiol 2005; 35: 947–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dillman JR, Attili AK, Agarwal PP, Dorfman AL, Hernandez RJ, Strouse PJ: Common and uncommon vascular rings and slings: a multimodality review. Pediatr Radiol 2011; 41: 1440–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hilmes M, Hernandez R, Devaney E: Markedly hypoplastic circumflex retroesophageal right aortic arch: MR imaging and surgical implications. Pediatr Radiol 2007; 37: 63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]