Abstract

Background

Nursing has a reputation for being a predominantly stressful profession. Prior studies focus on the overt antecedents of stress like bullying, harassment, and verbal aggression from patients as well as colleagues. Employee stress has been receiving attention for decades, yet there is a research gap on the role of workplace ostracism as an antecedent of stress for nurses. This study aimed to consider the effect of workplace ostracism on the perceived stress of nurses while considering the moderating role of perceived organizational support.

Methods

This study is quantitative. A time-lagged survey was conducted in private and public hospitals of Pakistan. Data were collected from 241 nurses. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software and analysis of a moment structures (AMOS) software were employed for data analysis, such as bootstrapping analysis, Sobel test, and regression analysis.

Results

Results demonstrated that workplace ostracism is positively associated with stress, while perceived organizational support has a moderating relationship. Perceived organizational support mitigates the adverse effects of workplace ostracism on nurses.

Conclusion

This study contributes significantly to nursing literature by identifying workplace ostracism as one of the significant antecedents of stress for nurses. Perceived organizational support shows that employees are cared for and appreciated by the organization, which lessens the strength of perceived stress due to workplace ostracism.

Keywords: nurses, stress, perceived organizational support, workplace ostracism, Pakistan

Introduction

Human, social, manufactured, and financial capital are organization resources.1 In the current business era, social and relationship capitals have gained vital importance in contemporary workplaces. It signifies the social relations that permit people and groups to collaborate2 and uphold associations with pertinent stakeholders.3 Its significance is highlighted by the fact that appropriate job relations between organizational stakeholders and social work-settings are deemed to be strategically vital for positive work outcomes.4 Mistreatment is related to several undesirable outcomes from physical and mental health,5 turnover intentions,6 and interpersonal deviance.7 It provides a sense of social rejection and segregation to personnel, which potentially impede their ability to promote organizational benefits.

Nursing is particularly renowned as a stressful profession.8,9 Nurses face non-stop exposure to emotionally charged-up and demanding circumstances and are mandated to provide compassionate care frequently in adverse surroundings.11 They are anticipated to control their sentiments as well as soften the anxiety and suffering of patients and their families alike.12 In such a situation, a covert form of mistreatment from colleagues and supervisors in work settings can prove to aggravate the mental pressure that nurses face and can result in stress.

The role of workplace ostracism in aggravating stress and the effect of perceived organizational support as a moderator in the relationship above is mostly unknown in the case of nurses. To maintain personal health and well-being, recovering from stress is vital.13 In the absence of complete recovery, a person might be susceptible to critical health risks likes hypertension14 and in more severe cases, cardiovascular death.15 The harmful effects of such stress might lead to deteriorated performance and un-helping behavior toward patients.4 Perceived organizational support might act as a vital recovery resource, that may help in lessening the adverse effects of stress.

Conservation of resources theory provides a perfect avenue for understanding the influence of workplace ostracism. It proposes that individuals try to increase, preserve, advance, and defend the belongings they cherish the most. The extent of belongingness, social controls, self-esteem, and meaningful existence govern the level of people’s personal and social resources. Risk of danger to such resources might cause a tend-and-befriend reaction16 and leads to stress.17 Moreover, in the grounds of conservation of resources theory, personal, situational and other positive resources like self-control and self-belief may prove to assist in reducing the negative influence of resource loss that might eventually result in inferior performance.

Workplace ostracism has been indicated to be an interpersonal stressor8,18; however, scholars have not yet studied it from a stress viewpoint.4 It is essential to study the connection between workplace ostracism and stress-related outcomes.19 Therefore, the present study will focus on the relationship between workplace ostracism and stress to fill this empirical gap. This study comprises perceived organizational support as a real job resource which would serve as a mitigating agent and buffer the detrimental effect of workplace ostracism on nurse’s stress in the health care industry of Pakistan.

The stress that nurses’ face during work can contribute negatively toward patient satisfaction. Little is known about ostracism as a source of stress in nurses. Therefore, it is imperative to study ostracism as the antecedent of stress and boundary condition of organizational support as a mitigating agent of ostracism–stress relationship.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses development

Conservation of resources theory

Conservation of resources theory is amongst the most commonly cited theories in organizational behavior and psychology. It embarks on the principle that people endeavor to attain, preserve, foster, and defend the belongings they centrally value.20 Conservation of resources theory posits that stress arises with a threat of resource loss; with the actual resource loss or failure to attain crucial additional resource despite efforts.17 In the premises of conservation of resources theory, resources are generally defined as the total ability a person possess to realize his or her valuable needs.21 Hobfoll has defined resources as:

objects, personality characteristics, conditions or energies that are valued by the individual or that serve as a means for the attainment of these objects, personal characteristics or energies. (pp. 516)20

Resources might stem from personal self and/or the surroundings, and include physiological resources (like biological well-being, fitness, muscle strength), motivational resources (like purpose orientation, self-efficacy, goal commitment), financial resources (like income, assets), cognitive resources (like experience, knowledge) and social resources (like aid from supervisors, social support).22–24 The conservation of resources theory posits that the path to resource conservation consists of a couple of parallel mechanisms. The resource accumulation mechanism activates when individuals utilize their resources to adjust their behaviors, actions, and reactions and exercise control over their surroundings to expand their resource bases vital for the fulfillment of their valued needs.25

Workplace ostracism

Ostracism indicates the degree to which people perceive a feeling of being ignored or left out by others.26 In workplaces, it takes the shape of exclusion, avoiding eye contact, departing the room on arrival of a person, transferring someone to a distant place, and failing to answer coworkers’ greetings.27,28 Ostracism differs from interpersonal deviance, bullying, social undermining, aggression, and harassment in several ways. First, the following notions are interactional, whereas the absence of an interaction recognizes ostracism. Secondly, the social background and relevant customs validate the social acceptance of ostracism.16,18,29

Job stress

Stress is frequently expressed as a sense of being overwhelmed, concerned, or run-down. Hans Selye coined the term “stress” in 1936.30 Hans defined it as “the non-specific response of the body to any demand for change.” In the existing literature, quite a few definitions have been used to describe stress. The current study operationalizes stress by the “Encyclopedia of Stress,” where stress is defined as “real or an interpreted threat to the physiological or psychological integrity of an individual that results in physiological and behavioral response.”31

Workplace ostracism and job stress

According to Chung, comprehensive studies have not yet inspected the connections between workplace ostracism and perceived stress of personnel.4 Workplace ostracism has a detrimental effect on employee’s well-being as it instigates pain and is a disliked experience.26 Researchers have confirmed that ostracism is associated with negative affect,32 frustration, sadness, nervousness,33,34 emotional exhaustion19 and adverse emotional conditions, for example, sorrow, despair, solitude, envy, culpability, indignity, embarrassment and social apprehension.35,36 Conservation of resources theory offers a perfect avenue to test the validity of such an idea. Theory starts on the principle that individuals try to get, preserve, foster, and protect the possessions they centrally value.20 Conservation of resources theory puts forward that:

stress occurs (a) when central, or key resources are threatened with loss, (b) when central or key resources are lost, or (c) when there is a failure to gain central or key resources following significant effort.17

H1: Workplace ostracism is positively related to job stress.

Perceived organizational support

The perceived organizational support is defined as the sense or feeling of being valued and cared for by the organization in return for one’s contributions. It means that a person’s well-being is accounted for by the organization in exchange for his/her work efforts.37 Perceived organizational support is contemplated as the firm’s input in positive reciprocity dynamic with personnel, as personnel tends to do a better job to return the favors of obtained rewards and promising treatment. This concept was originated by Eisenberger and Rhoades’ organizational support theory.37,38 Perceived organizational support includes support from the organization in the form of the environment of justice, meaningful rewards, positive job settings, and supervisory relations that indicate to personnel the degrees to which they are valued and respected by the organization and provides them with a motive to trust the organization.37

Perceived organizational support, ostracism, and stress

Previous studies have established that support has an allaying influence on the association between stressors and stress reactions, like anxiety, despair, annoyance, well-being, job discontent, tension, and personal productivity.39–43 High level of perceived organizational support might lessen the harmful influence of workplace ostracism as stress. The strain is likely to be felt in greater strength when perceived organizational support is lower. In case of higher perceived organizational support, the strain is usually perceived as lesser, though it might just be as present.44,45 Similarly, Richardson found perceived organizational support to be significantly correlated with all the stressor and strains.46 The correlation was found to be even stronger for cognitive/emotional strains.

According to the conservation of resources theory, support can be considered as a social resource. More specifically perceived organizational support would be better regarded as a positive job resource which may be mobilized to compensate the harmful effects (like burnout, deviant employee behaviors) of initial resource loss arising from stressful work environments.25,47,48 Perceived organizational support can act as a vital resource to deal with the stressful situation and lessen the influence of such stress due to workplace ostracism.

H2: Perceived organizational support moderates the association between workplace ostracism and stress.

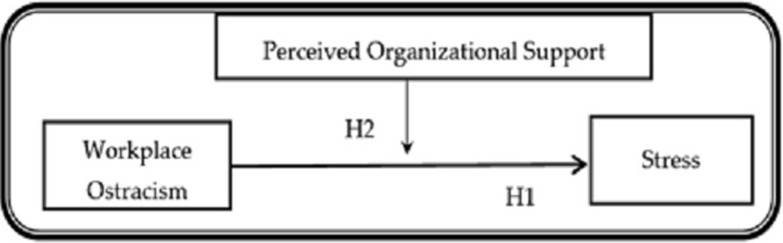

Figure 1 shows study theoretical framework. Workplace ostracism is an independent variable which has relation with stress. Perceived organizational support is moderating variable.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

Research methodology

According to Abubakar, employees in the services sector of developing countries often face mistreatment in the absence of a robust legislative framework.49 Nurses employed in southern Punjab’s hospitals participated in this study. Nurses have daily interaction with their colleagues and patients, and stress levels are usually high due to workload, interdependence, maltreatment, and disharmonious relations.

The researchers adopted non-probability convenience sampling for conducting the study. The quantitative approach has been adopted to check the relationship between workplace ostracism, stress and perceived organizational support. Online and paper questionnaires were developed for data collection. We distributed 100 online questionnaires via web link, and 62 correctly filled questionnaires were received from the participants. Two hundred and fifty printed questionnaires were circulated among the nurses out of which 179 questionnaires found to filled correctly. The sample size for the current study is 241 nurses of Pakistani health care centers.

Data were collected in different in two phases. There was 20 days gap between phase 1 and phase 2. In phase 1, workplace ostracism and demographic/control variable-related questionnaires were floated, and data related to stress and perceived organizational support was collected in the second phase. The idea was to decrease the common method bias.50 Data collection in more than one wave influences the measurement context (environment, location, etc.). Codes were generated to match the same respondents’ responses to questionnaires at both phases. This data collection method is previously adopted by different researchers.8,51 Quantitative research methodology approach was adopted in this study. Process Macros latest technique was utilized for data analysis.52 Since it a useful method to deal with latent variables. The study aimed to find out the direct and interactive influence of workplace ostracism on stress by utilizing perceived organizational support as a moderating variable. Process Macros model-1 was applied in this study. Several tests were carried out in SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and AMOS (IBM, USA) softwares to check the validity and reliability of the date before testing the primary hypotheses. These tests involved exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis, descriptive statistics, validity & reliability analysis, correlation analysis, and hierarchical regression analysis.

Instruments

Workplace ostracism

Workplace ostracism was measured by adopting Ferris scale.26 Ferris scale obtain several items such as “Others ignored me at work,” “Others left the area when I entered,” and “My greetings have gone unanswered at work.” In previous studies, the scale shows the reliability value of 0.974 and 0.89.53

Perceived organizational support

Perceived organizational support was measured by adopting the eight-item scale from Eisenberger.38 This scale is balanced by adopting positive and negative questions such as “This organization cares about my well-being,” and “This organization shows very little concern for me.” Previous studies have shown high scale reliability, such as 0.89.54

Job stress

The Bond seven-item scale was utilized for measuring stress variable.55 The range queried about how frequently respondents felt in various ways during the last 3 months (e.g., “nervous or stressed,” “emotionally drained from work”). The response options were in the form of 5-point options and were coded in such a way that more significant number specify more stress. Previously, Behson has adopted the same scale for measurement. Scholars have used the scale in the previous studies.56

Control variables

In this study, gender, age, education, and job experience were considered as control variables. Prior studies revealed these variables as influencers of ostracism and burnout-related outcomes in the recent studies. And have controlled them in recent studies.4,57

Data analysis and results

Table 1 shows that on average, the respondents were above 29 years of age with a deviation of 7–8 years. Additionally, their experience was, on average, above 6 years with a deviation of 4 years, which implies that they were a mix of young and experienced personnel. Their education level was above graduation, and comparatively, more respondents were female (131; 54%) as compared to male (110; 46%). The values show a moderate correlation between the constructs (see Table 1), which is in line with guidelines (Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2014).

Table 1.

Descriptive and correlation analysis

| Constructs | Mean | SD | AG | EP | EL | WO | POS | ST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (AG) | 29.03 | 7.69 | 1 | |||||

| Experience (EP) | 6.78 | 4.36 | 0.99** | 1 | ||||

| Education level (EL) | 2.15 | 0.64 | 0.28** | 0.41** | 1 | |||

| Workplace ostracism (WO) | 3.43 | 0.87 | −0.13 | −0.09 | −0.12 | 1 | ||

| Perceived organizational support | 3.35 | 0.88 | 0.07 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.55** | 1 | |

| Stress (ST) | 3.34 | 0.65 | 0.18* | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.62** | −0.66** | 1 |

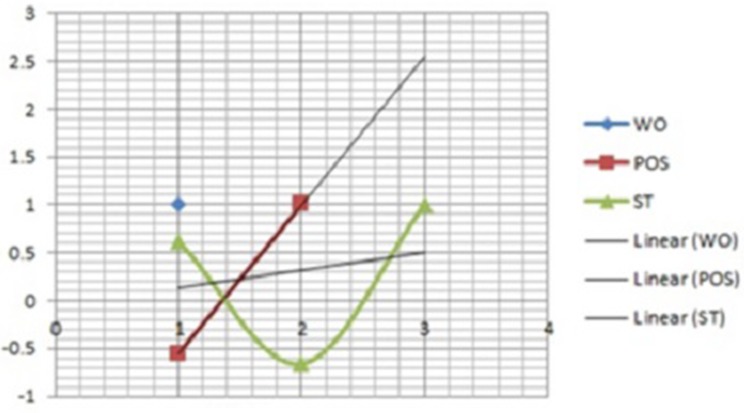

Figure 2 shows correction relationship among all the variables. Correlation analysis shows that there is significantly negative relationship between workplace ostracism and perceived organizational support. Moreover, there is significantly positive relationship between workplace ostracism and stress. It also shows that perceived organizational support and stress are negatively correlated.

Figure 2.

Correlation analysis.

Exploratory factor analysis

EFA was conducted by using SPSS-version 22. As a prerequisite to EFA, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity were performed (see Table 2). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin has a significant value of 0.681, which shows that data are appropriate to proceed with EFA. Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value range is between 0.5 and 1. According to Kline, Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value should be more than 0.6 for factor analysis.58 Statistical experts have set various benchmarks for conducting EFA.

Table 2.

KMO and Bartlett’s test

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy | 0.681 | |

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | Approx. Chi-square | 3854.234 |

| Df | 300 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 |

Confirmatory factor analysis

AMOS-Version 20 was utilized to carry out confirmatory factor analysis. It ensures the validity of the instrument and its appropriateness in the given context since it is vital to generalize the obtained results of the study.59 McArdle guidelines were followed to conduct confirmatory factor analysis.60 The current study includes three latent variables; workplace ostracism having 10 items scale; perceived organizational support having eight items scale; and stress with seven items scale. The fit indices have been attained by following Byrne.61 The results show that all constructs have been satisfactorily operationalized.

Table 4 shows the confirmatory factor analysis and scale reliability analysis results. The model fit indices show suitable results within acceptable ranges, i.e., Chi-square/df =2.37<3.00, RMSEA =0.058<0.08 and GFI =0.932−BBNNFI =0.952−CFI =0.914−IFI =0.916>0.90. Additionally, Table 3 also explains the average variance explained used for assessing the convergent validity. All the values were found to be more than the minimum acceptable criterion of 0.5.

Table 4.

Pattern matrix and reliability coefficients

| Items | Factor | Alpha value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| WPO1 | 0.774 | 0.85 | ||

| WPO2 | 0.691 | |||

| WPO3 | 0.719 | |||

| WPO4 | 0.747 | |||

| WPO5 | 0.841 | |||

| WPO6 | 0.703 | |||

| WPO7 | 0.622 | |||

| WPO8 | 0.771 | |||

| WPO9 | 0.564 | |||

| WPO10 | 0.655 | |||

| POS1 | 0.641 | 0.83 | ||

| POS2 | 0.716 | |||

| POS3 | 0.664 | |||

| POS4 | 0.721 | |||

| POS5 | 0.717 | |||

| POS6 | 0.703 | |||

| POS7 | 0.656 | |||

| POS8 | 0.704 | |||

| ST1 | 0.763 | 0.77 | ||

| ST2 | 0.632 | |||

| ST3 | 0.783 | |||

| ST4 | 0.604 | |||

| ST5 | 0.742 | |||

| ST6 | 0.649 | |||

| ST7 | 0.717 | |||

Abbreviations: WPO, workplace ostracism; POS, perceived organizational support; ST, stress.

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis and scale reliability

| Construct descriptions | Chi-square/df | RMSEA | GFI | CFI | BBNNFI | IFI | CR | AVE | MSV | ASV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fit indices | 2.37 | 0.058 | 0.932 | 0.914 | 0.952 | 0.916 | ||||

| WO | 0.87 | 0.60 | 0.41 | 0.21 | ||||||

| POS | 0.85 | 0.61 | 0.40 | 0.20 | ||||||

| ST | 0.77 | 0.56 | 0.38 | 0.17 |

Notes: Acceptable range of indices Chi-square/df <3.0, GFI-CFI-BBNNFI-IFI >0.90, RMSEA <0.08.

Abbreviations: CR, composite reliability; AVE, average variance extracted; WO, workplace ostracism; POS, perceived organizational support; ST, stress; MSV, maximum shared variance; ASV, average shared variance.

Table 4 shows factor loading values of workplace ostracism, perceived organizational support, and stress. According to DeCoster, the items with more than 0.4-factor loading should be included. As per criteria.62 Workplace ostracism was measured on the 10-items scale, and it has 0.85 Alpha value. Perceived organizational support was measured on an 8-items scale, and it has an Alpha value of 0.83. Similarly, stress was measured on the 7-items scale, and it has an Alpha value of 0.77.

Hypotheses testing

Hayes method was adopted for hypotheses testing, and it was conducted through SPSS software.52 It is also known as the Process Macros (Model-1). Preliminary tests were conducted before carrying out hierarchical linear regression to ensure the appropriateness of the data. Skewness and kurtosis tests were carried out to certify the normality of the data. The data is acceptable within standards set by Hair as the values of skewness & kurtosis were found to be between −1 and +1. Moreover, the standardized residuals centrality to zero with linear relationship guaranteed that there was no element of heteroscedasticity in data. The results were also of tolerance since the variance inflation factor (VIF) was also within the acceptable ranges, i.e., tolerance 0.41 and VIF 2.15. It was confirmed that there was no multicollinearity in the data after conducting heteroscedasticity, tolerance, and VIF analysis.

Direct effect

Hierarchical linear regression analysis was conducted through SPSS software for checking the relationship between workplace ostracism and stress. The moderating effect of perceived organizational support on workplace ostracism and stress was also tested.

Table 5 represents the results of a direct effect. It reveals that workplace ostracism is positively related to stress as there was 36% variation found in stress due to workplace ostracism (R2=0.36, t=9.31, ρ<0.05). The results of the F-statistics confirmed the general viability of the overall-regressed model (F=144.122, ρ<0.05). Therefore, it can be concluded that nurses ostracized at the workplace remain under stress.

Table 5.

Regression analysis

| Relationship | R2 | ∆R2 | f-value | β | t-value | ρ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WO→ST | 0.36 | 144.122 | 0.55 | 9.31 | ** | |

| WO*POS (ST) | 0.059 | 0.420, 0.612, 0.832 | ** |

Note: **P<0.05.

Abbreviations: WO, workplace ostracism; POS, perceived organizational support; ST, stress.

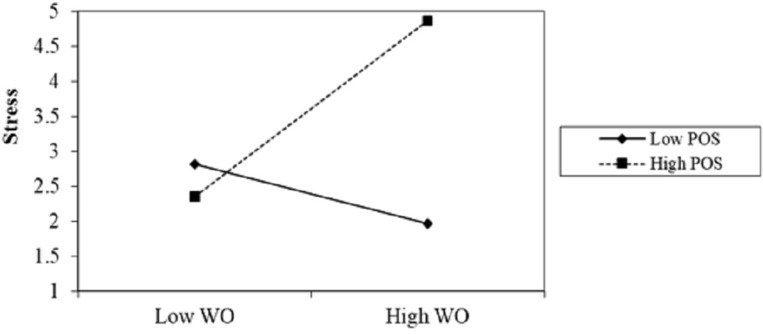

Figure 3 represents the graphical representation of perceived organizational support as a moderator variable. It also shows that the high level of perceived organizational support helps nurses to reduce their stress level induced by workplace ostracism.

Figure 3.

Interaction effect.

Moderating effect

In the second phase, the interactive effect of perceived organizational support on the relationship between workplace ostracism and stress was analyzed. The results reflected that perceived organizational support buffers the adverse effect of workplace ostracism on stress (∆R2=0.059, ρ<0.05). The nurses had high perceptions of organizational support, which can avert the negative consequences of workplace ostracism. At the second level, the results of hierarchical linear regression results were reconfirmed through Process Macros, and results are shown in Table 6. The results indicate that perceived organizational support could be a tool used by health care managers to safeguard its nurses from the harmful effects of workplace ostracism. The process of bootstrapping was executed at the level of 5000 and used the Model-1 of the Process Macros. The process took values of the moderator at 18th, 54th and 85th percentiles. Results indicated that the overall interaction term caused 6.3% change in R-square.

Table 6.

Moderating effect through bootstrapping process

| Outcome | Predictor | R2 | ∆R2 | Effects | f-value | β | SE | t-value | LLCI | ULCI | ρ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST | 0.36 | 144.1 | ** | ||||||||

| WO | 0.41 | 0.13 | 9.310 | 1.464 | 2.991 | ** | |||||

| POS | 0.61 | 0.12 | 7.743 | 1.875 | 3.141 | ** | |||||

| WO*POS | 0.603 | 167.48 | 0.83 | 0.03 | 10.321 | 2.123 | 3.550 | ** |

Note: **Ρ<0.05. Applied Model 59 of Hayes (2017) with 5000 bootstrapping process,52 M values at 18th, 54th and 85th percentiles.

Abbreviations: IV, workplace ostracism (WO); DV, stress (ST); M, perceived organizational support (POS); LLCI, lower level CI; ULCI, upper-level CI.

Discussions

Study findings demonstrate that the social context in work settings is vital. It can critically distract the employees mental and emotional well-being. Pakistani health care sector is facing serious challenges such as employees’ performance and motivation. According to prior studies, workplace ostracism is positively related to anxiety and depression26 but present study has revealed workplace ostracism positive relationship to stress. Exclusion and silent treatment can produce negative self-perceptions among employees. Such emotional state can act supplementary in authorizing a person to sense a shortage of control. When employees feel ostracized, they will sense a shortage of mutual support from colleagues and supervisor. Thus, resource loss is perceived because social support has been deemed to be a vital resource.20 Ostracized people will possibly feel stressed due to undesirable events, consequently.

Contemporary study results show that workplace ostracism is a passive form of mistreatment. It has an impact on the nurse’s mental state, and as a result, it leads to stress. Previously, researchers have demonstrated stress to be linked with detrimental outcomes.4 Workplace ostracism has seldom been linked to stress and needed to be explored further from stress standpoint.4,19 So, current study has a significant contribution to the existing literature.

Workplace ostracism drains valuable resources which are vital to assist personnel at the workplace.63 Study presented valuable insights on nurses working in a developing country with collectivist, power distant and risk-averse culture. Another significant contribution of this study is the validation of perceived organizational support as a moderating variable in the association between workplace ostracism and job stress. Study hypotheses have been accepted.

Additionally, prior studies have shown that individuals belonging from collectivistic societies are inclined to give undue importance to harmonious interpersonal relations64 and therefore such individuals might be more susceptible to workplace mistreatment in the form of ostracism.65 The study shows that employees swallow agitation caused by workplace ostracism and continue working on the same job. In harmony with the basic tenets of conservation of resources theory, the occurrence of workplace ostracism, job resource perceived organizational support is principally valuable in mitigating the employees stress sense due to maltreatment. The more important is the sense of perceived support from the organization; the lesser are the chances of them feeling overburdened due to emotional/mental exhaustion as they believe that organization is their significant beneficiary and can be trusted to improve their well-being.37 Study demonstrated that employees trust an organization concerning support lessen stress because they are less occupied in worries about the anti-social work-context and focus more on job resources presented the organization. Study results have vital implications in the health care sector of Pakistan. There is positive relationship between workplace ostracism and job stress. The moderating role of organizational support cannot be neglected. Managers should develop an engaged workforce for better output, besides this, employees’ self and social capabilities should also be taken into account at the workplace. Managers should provide organizational support to their employees. Such policies should be adopted by the managers those can reduce ostracism.

Study limitations

The study focuses on the relationship between workplace ostracism and stress while considering the moderating role of perceived organizational support. Further studies could consider other moderating variables such as self-efficacy and trait competitiveness. The similar association can be examined by adding non-work-related outcomes such as work-family conflict. Additionally, cross-country investigations might offer a profound understanding of comparative analysis of unpleasant workplace environments for leveraging specific job resources.

Theoretical contribution

The Conservation of Resources theory endorsed the relationship between workplace ostracism, stress, and perceived organizational support in the context of the health care industry. Conservation of resources theory points out that:

stress occurs when central or key resources are threatened with loss, when central or key resources are lost or when there is a failure to gain central or key resources following significant effort.17

The current study outcomes are in line with conservation of Resources theory. Workplace ostracism creates a sense of threat to employees about one of their valued resource (e.g., need for affiliation, belongingness, socialization, etc.) and therefore results in stress.

The study also uses perceived organizational support as a positive job resource in the premises of conservation of resources theory for mitigating the negative effect of resource loss arising from workplace ostracism. Perceived organizational support represents support from the organization in the form of organizational justice, equitable rewards, positive work settings, and managerial relations.37 All these resources are favorable for the employees. That signal to employees that they are valued and respected members of the organization. When employees perceive this support, they are expected to attest access to essential job resources.

Conclusion

The current study shows that workplace ostracism is related to stress, and perceived organizational support has a moderating role between workplace ostracism and stress. The study has established that perceived organizational support signifies a positive job resource. The study has contributed to the emergent frame of knowledge regarding perceived organizational support.37,66 The findings demonstrate that health care centers can assist employees to feel advantageous as organizational members by advancing supportive organizational perceptions and perform in the work settings even when relations at the workplace might not be perfect. The upper management might make use of perceived organizational support to mitigate the negative effects of workplace ostracism since such behavior cannot be evaded. Supportive work culture environment should be provided by the leaders, managers, supervisors, and HR department.37 The organization can make better use of perceived organizational support to mitigate the adverse effects of workplace ostracism.

Acknowledgment

The study was funded by the China National Social Science Fund (grant: 18BGL129).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interests in this work.

References

- 1.Bebbington A. Capitals and capabilities: a framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty. World Dev. 1999;27(12):2021–2044. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00104-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roseland M. Sustainable community development: integrating environmental, economic, and social objectives. Prog Plann. 2000;54(2):73–132. doi: 10.1016/S0305-9006(00)00003-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhakal SP. The five capitals framework for exploring the state of friends’ groups in Perth, Western Australia: implications for urban environmental stewardship. Int J Environ Cult Econ Soc Sustain. 2011;7(2):135–147. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung YW. Workplace ostracism and workplace behaviors: a moderated mediation model of perceived stress and psychological empowerment. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2018;31(3):304–317. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2018.1424835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harnois CE, Bastos JL. Discrimination, harassment, and gendered health inequalities: do perceptions of workplace mistreatment contribute to the gender gap in self-reported health? J Health Soc Behav. 2018;59(2):283–299. doi: 10.1177/0022146518767407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhry NI, Mahesar HA, Pathan SK, Arshad A, Butt A. The mediating role of workplace interpersonal mistreatment: an empirical investigation of banking sector of Pakistan. Journal of Business Studies – JBS 2017;13(1);73–88. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu H, Lyu Y, Deng X, Ye Y. Workplace ostracism and proactive customer service performance: a conservation of resources perspective. Int J Hosp Manag. 2017;64:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.04.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jahanzeb S, Fatima T. How workplace ostracism influences interpersonal deviance: the mediating role of defensive silence and emotional exhaustion. J Bus Psychol. 2017;33:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martos Á, Del Carmen Pérez-Fuentes M, Del Mar Molero M, Gázquez JJ, Del Mar Simón M, Barragán AB. Burnout y engagement en estudiantes de Ciencias de la Salud. Eur J Investig Heal Psychol Educ. 2018;8(1):23–36. doi: 10.30552/ejihpe.v8i1.223 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunsaker S, Chen H, Maughan D, Heaston S. Factors that influence the development of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in emergency department nurses. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015;47(2):186–194. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolton S. Changing faces: nurses as emotional jugglers. Sociol Health Illn. 2001;23(1):85–100. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.00242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diefendorff JM, Erickson RJ, Grandey AA, Dahling JJ. Emotional display rules as work unit norms: a multilevel analysis of emotional labor among nurses. J Occup Health Psychol. 2011;16(2):170. doi: 10.1037/a0021725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geurts SA, Sonnentag S. Recovery as an explanatory mechanism in the relation between acute stress reactions and chronic health impairment. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32(6):482–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hocking SJL, O’BRIEN WH. Cardiovascular recovery from stress and hypertension risk factors: a meta‐analytic review. Psychophysiology. 1997;34(6):649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kivimäki M, Virtanen M, Elovainio M, Kouvonen A, Väänänen A, Vahtera J. Work stress in the etiology of coronary heart disease – a meta-analysis. Scand J Work Environ Health.2006. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams KD. Ostracism. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:425-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hobfoll SE, Halbesleben J, Neveu J-P, Westman M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav. 2018;5:103–128. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams KD: Social ostracism. In Kowalski R (ed), Aversive Interpersonal Behaviors. New York: Plenum Press, 1997, 133–170. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu L, Yim FH, Kwan HK, Zhang X. Coping with workplace ostracism: the roles of ingratiation and political skill in employee psychological distress. J Manag Stud. 2012;49(1):178–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2011.01017.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44(3):513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hobfoll SE. The influence of culture, community, and the nested‐self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl Psychol. 2001;50(3):337–421. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao Y, Shi J, Niu Q, Wang L. Work–family conflict and job satisfaction: emotional intelligence as a moderator. Stress Heal. 2013;29(3):222–228. doi: 10.1002/smi.2451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang M. Profiling retirees in the retirement transition and adjustment process: examining the longitudinal change patterns of retirees’ psychological well-being. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(2):455. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang M, Liao H, Zhan Y, Shi J. Daily customer mistreatment and employee sabotage against customers: examining emotion and resource perspectives. Acad Manag J. 2011;54(2):312–334. doi: 10.5465/amj.2011.60263093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hobfoll SE. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Rev Gen Psychol. 2002;6(4):307. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferris DL, Brown DJ, Berry JW, Lian H. The development and validation of the workplace ostracism scale. J Appl Psychol. 2008;93(6):1348. doi: 10.1037/a0012743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson SL, O’Reilly J, Wang W. Invisible at work: an integrated model of workplace ostracism. J Manage. 2013;39(1):203–231. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu E, Huang X, Robinson SL. When self-view is at stake: responses to ostracism through the lens of self-verification theory. J Manage. 2017;43(7):2281–2302. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brinsfield CT, Edwards MS, Greenberg J. Lustenberger DE, Williams KW. Ostracism in organizations. In: Greenberg J, Edwards M, editors. Voice and silence in organizations: Historical review and current conceptualizations. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing; 2009:245–274.. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selye H. The evolution of the stress concept: the originator of the concept traces its development from the discovery in 1936 of the alarm reaction to modern therapeutic applications of syntoxic and catatoxic hormones. Am Sci. 1973;61(6):692–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fink G. Encyclopedia of Stress. Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams KD, Govan CL, Croker V, Tynan D, Cruickshank M, Lam A. Investigations into differences between social-and cyberostracism. Gr Dyn Theory, Res Pract. 2002;6(1):65. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.6.1.65 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson P, Pulich M. Managing workplace stress in a dynamic environment. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2001;19(3):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colligan TW, Higgins EM. Workplace stress: etiology and consequences. J Workplace Behav Health. 2006;21(2):89–97. doi: 10.1300/J490v21n02_07 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gruter M, Masters RD. Ostracism as a Social and Biological Phenomenon: An Introduction. Ethology & Sociobiology 1986;7(3-4):149-158. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leary MR. Interpersonal Rejection. Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rhoades L, Eisenberger R. Perceived organizational support: a review of the literature. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(4):698. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eisenberger R, Huntington R, Hutchison S, Sowa D. Perceived organizational support. J Appl Psychol. 1986;71(3):500. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaufmann GM, Beehr TA. Interactions between job stressors and social support: some counterintuitive results. J Appl Psychol. 1986;71(3):522. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirmeyer SL, Dougherty TW. Work load, tension, and coping: moderating effects of supervisor support. Pers Psychol. 1988;41(1):125–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1988.tb00635.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scott KL, Zagenczyk TJ, Schippers M, Purvis RL, Cruz KS. Co‐worker exclusion and employee outcomes: an investigation of the moderating roles of perceived organizational and social support. J Manag Stud. 2014;51(8):1235–1256. doi: 10.1111/joms.12099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viswesvaran C, Sanchez JI, Fisher J. The role of social support in the process of work stress: a meta-analysis. J Vocat Behav. 1999;54(2):314–334. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1998.1661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robblee MA. Confronting the Threat of Organizational Downsizing: Coping and Health [Dissertation]. Ottawa: Carleton University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Venkatachalam M. Personal Hardiness and Perceived Organizational Support as Links in the Role Stress-outcome Relationship: A Person-environment Fit Model. Washington, DC, USA; American Psychological Association. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richardson HA, Yang J, Vandenberg RJ, DeJoy DM, Wilson MG. Perceived organizational support’s role in stressor-strain relationships. J Manag Psychol. 2008;23(7):789–810. doi: 10.1108/02683940810896349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halbesleben JRB. Sources of social support and burnout: a meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources model. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91(5):1134. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hobfoll SE, Johnson RJ, Ennis N, Jackson AP. Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(3):632. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abubakar AM, Yazdian TF, Behravesh E. A riposte to ostracism and tolerance to workplace incivility: a generational perspective. Pers Rev. 2018;47(2):441–457. doi: 10.1108/PR-07-2016-0153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lyu Y, Zhu H. The predictive effects of workplace ostracism on employee attitudes: a job embeddedness perspective. J Bus Ethics. 2017;158(4):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayes AF, Rockwood NJ. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav Res Ther. 2017;98:39–57. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fatima T. Interactive effects of workplace ostracism and belief in reciprocity on fear of negative evaluation. Pak J Commer Soc Sci. 2017;11:3. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dawley D, Houghton JD, Bucklew NS. Perceived organizational support and turnover intention: the mediating effects of personal sacrifice and job fit. J Soc Psychol. 2010;150(3):238–257. doi: 10.1080/00224540903365463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bond JT, Galinsky E, Swanberg JE. The National Study of the Changing Workforce, 1997. Vol. 2 ERIC; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Behson SJ. The relative contribution of formal and informal organizational work–family support. J Vocat Behav. 2005;66(3):487–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2004.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee JJ, Ok CM. Understanding hotel employees’ service sabotage: emotional labor perspective based on conservation of resources theory. Int J Hosp Manag. 2014;36:176–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.08.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kline P. An Easy Guide to Factor Analysis. Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoyle RH. Evaluating measurement models in clinical research: covariance structure analysis of latent variable models of self-conception. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59(1):67. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McArdle JJ. Current directions in structural factor analysis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 1996;5(1):11–18. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772681 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Byrne BM. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. Taylor & Francis (Routledge); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 62.DeCoster J. Overview of Factor Analysis. 1998.Available from: http://www.stat-help.com/. Accessed September 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leung ASM, Wu LZ, Chen YY, Young MN. The impact of workplace ostracism in service organizations. Int J Hosp Manag. 2011;30(4):836–844. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang KS. Chinese Social Orientation: An Integrative Analysis. In: Lin TY, Tseng WS, Yeh YK, editors. Chinese Societies and Mental Health Hong Kong: Oxford University Press; 1995:19–39. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Powell GN, Francesco AM, Ling Y. Toward culture‐sensitive theories of the work–family interface. J Organ Behav. 2009;30(5):597–616. doi: 10.1002/job.568 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eisenberger R, Stinglhamber F. Perceived Organizational Support: Fostering Enthusiastic and Productive Employees. American Psychological Association; 2011. [Google Scholar]