Abstract

Background:

The federal Title X Family Planning Program supports the delivery of family planning services and related preventive care to 4 million individuals annually in the United States. The implementation of the 2010 Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) Medicaid expansion and provisions expanding access to health insurance, which took effect in January 2014, resulted in higher rates of health insurance coverage in the U.S. population; the ACA’s impact on individuals served by the Title X program has not yet been evaluated.

Methods:

Using administrative data we examined changes in health insurance coverage among Title X clinic patients during 2005–2015.

Results:

We found that the percentage of clients without health insurance decreased from 60% in 2005 to 48% in 2015, with the greatest annual decrease occurring between 2013 and 2014 (63% to 54%). Meanwhile, between 2005 and 2015, the percentage of clients with Medicaid or other public health insurance increased from 20% to 35% and the percentage of clients with private health insurance increased from 8% to 15%.

Conclusions:

Although clients attending Title X clinics remained uninsured at substantially higher rates compared with the national average, the increase in clients with health insurance coverage aligns with the implementation of ACA-related provisions to expand access to affordable health insurance.

Keywords: Title X, insurance coverage, Medicaid expansion, health reform, reproductive health

Introduction

The Title X Family Planning Program, administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Population Affairs (OPA), is the only federal program solely dedicated to providing individuals with comprehensive family planning and related preventive health services.1 The Title X program served 4 million women and men in 2015 through a network of ~4,000 service sites (i.e., health clinics).2 This network serves as a core safety net provider for a patient population with a substantial share of low-income, uninsured, and Medicaid-insured patients, as well as those in need of confidential reproductive health services. While studies using national-level data have found a decrease in the percentage of people without health insurance since the implementation of health insurance expansion provisions included in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA),3,4 it is unclear whether these findings can be generalized to the population served by the Title X family planning network. Health system changes nationally could have a paradoxical effect on the Title X network, leading to a higher percentage of uninsured clients in Title X, as clients gaining health insurance seek reproductive health services from other public or private providers.5

In this study, we examine how the insurance status of Title X clients has changed over time, with a focus on shifts in the percentage of clients with public or private insurance following the implementation of key ACA-related health coverage expansion provisions, namely the inception of ACA-enabled Medicaid expansions and state and federal health insurance Marketplaces. In addition, we assess how changes in public and private insurance coverage differed over time by ACA-enabled state Medicaid expansion status.

Study Data and Methods

We analyzed data from 2005 through 2015 from the Family Planning Annual Report (FPAR), an annual data reporting requirement of all Title X funding recipients (i.e., grantees).6 Using a secure electronic website, grantees aggregate and report annual performance data from ~4,000 health clinics that receive Title X funding. FPAR data are reviewed during data entry for internal consistency and after electronic submission, for consistency with previous year’s data; out-of-range values and missing data are flagged for review and correction. The national summary report presents aggregated data from Title X grantees in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and eight U.S. territories and jurisdictions. FPAR does not contain any client-level data.

FPAR data on Title X client characteristics include self-reported sex, age, race, ethnicity, and annual family income level. Income level is reported on FPAR as a percentage of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services poverty guidelines7 and is calculated by Title X service sites and grantees using client-reported information on family size, annual household income, state of residence, and year of service visit. For this analysis, we organized client income into three categories: <101%, 101% to 250%, and >250% of the poverty guidelines. Federal law requires that all Title X-funded health clinics provide family planning services at no charge to individuals with incomes <101% of the poverty guidelines (e.g., $24,250 for a family of four in the 48 contiguous states plus DC in 20157). For individuals with incomes between 101% and 250% of the poverty guidelines who self-pay for services, Title X-funded health clinics are required to charge for services based on a sliding fee scale.8

FPAR also collects information on each client’s health insurance coverage status at the time of visit. Title X clients are classified as insured if they have health insurance that covers a broad set of primary medical care benefits, even if their insurance is not billed for services rendered. Insured clients are further classified by whether the coverage is private or public. Private insurance includes health insurance coverage purchased through an employer, union, direct purchase, or insurance purchased for public employees, retirees, military personnel, or their dependents. Public insurance includes federal, state, or local government health insurance programs, such as Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program. In 2013, in anticipation of the enactment of ACA-related health insurance provisions, “public-paid or public-subsidized private insurance programs” were added as descriptions to the public insurance category. This definition was intended to capture subsidized private insurance plans purchased through the ACA-enabled state and federal health insurance Marketplaces as a type of public insurance. Clients with single service insurance plans (e.g., vision, dental, or family planning services only) are considered uninsured, as are clients with coverage through the Indian Health Service (IHS) who received care in non-IHS facilities. FPAR began collecting client health insurance data in 2005.

Using data from the Kaiser Family Foundation on Medicaid expansion, we grouped Title X funding recipients according to whether their Title X service network operated in a state that adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion and, if so, when that expansion took place.9 States that adopted Medicaid expansions as of January 1, 2014, were classified as “2014 expansion states” (n = 24, plus the District of Columbia); states that adopted Medicaid expansions after January 1, 2014, and by January 1, 2015, were classified as “2015 expansion states” (n = 3); and states that did not adopt Medicaid expansion as of January 1, 2015, were considered “non-expansion states” (n = 23). Territories were excluded from this specific analysis, as they did not have the option to expand their Medicaid programs under the ACA.

Statistical analysis

For each year (2005–2015), we tabulated the total number of Title X clients and calculated the percentage distribution by demographic and social characteristics, health insurance coverage status, and state Medicaid expansion status. We also calculated the percentage of clients with public and private health insurance, separately, by state Medicaid expansion status for each year. FPAR data collection is considered a census, as it includes data from all Title X funding recipients. Therefore, we did not calculate estimates of precision or perform statistical significance testing.

Results

During 2005–2015, an annual average of 4.8 million clients received services at Title X-funded health clinics, with annual client volume declining from ~5.0 to 4.0 million during that period (Table 1). On average for this period, most clients were female (93%), less than 30 years old (73%), had low income (69% with family incomes less than 101% of the poverty guidelines), and received services at Title X clinics operating in a 2014 expansion state (57%). Between 2005 and 2015, the percentage of male clients increased from 5% to 10%, clients less than 20 years old decreased from 26% to 18%, clients aged 30–39 years increased from 17% to 23%, and clients receiving care from clinics operating in a 2014 expansion state increased from 52% to 61%. The percentage of clients with annual family incomes less than 101% of the poverty guidelines remained relatively stable during the study period (between 66% and 70%); the percentage with annual family incomes from 101% to 250% of the poverty guidelines decreased from 27% to 22% between 2005 and 2015. The number of grantees ranged from 87 to 95, and the number of service sites decreased from 4,426 to 3,951.

Table 1.

Demographics of Clients Receiving Services at Health Clinics Funded by Title X, Family Planning Annual Reports 2005–2015

| Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Client demographicsa | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | All |

| Total, n | 5,002,961 | 4,987,238 | 5,186,267 | 5,021,711 | 4,557,824 | 4,018,015 | 4,812,522b |

| Sex (%) | |||||||

| Female | 95 | 94 | 93 | 92 | 92 | 90 | 93 |

| Male | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 7 |

| Age, years (%) | |||||||

| Less than 20 | 26 | 25 | 24 | 21 | 18 | 18 | 22 |

| 20–29 | 50 | 51 | 50 | 51 | 51 | 49 | 51 |

| 30–39 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 21 | 23 | 19 |

| 40 and older | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 8 |

| Ethnicity and race (%) | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 19 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 47 | 47 | 43 | 41 | 40 | 36 | 42 |

| Non-Hispanic other | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| Hispanic | 24 | 26 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 32 | 28 |

| Unknown/not reported | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Poverty guidelinesc (%) | |||||||

| Less than 101% | 66 | 69 | 70 | 69 | 70 | 66 | 69 |

| 101–250% | 27 | 25 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 23 |

| Over 250% | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| Not reported | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| State Medicaid expansion statusd (%) | |||||||

| Expanded on January 1, 2014 | 52 | 54 | 56 | 57 | 60 | 61 | 57 |

| Expanded between January 1, 2014 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 9 |

| and January 1, 2015 | |||||||

| No expansion as of January 1, 2015 | 37 | 35 | 34 | 33 | 31 | 30 | 34 |

| Title X network information | |||||||

| Title X grantees | 87 | 89 | 89 | 91 | 95 | 91 | |

| Title X service sites | 4,426 | 4,542 | 4,515 | 4,382 | 4,168 | 3,951 | |

Data for even years not shown. Categories may not sum to 100% due to rounding. All categories include data from Title X projects in U.S. territories except for client demographics by state Medicaid expansion status categories.

All Family Planning Annual reports may be accessed here: www.hhs.gov/opa/title-x-family-planning/research-and-data/fp-annual-reports/index.html

Mean annual client volume.

Family income as a percentage of federal poverty guidelines.

Expanded as of January 1, 2014, includes the following: AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DC, DE, HI, IA, IL, KY, MA, MD, MN, ND, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, RI, VT, WA, and WV. Expanded after January 1, 2014, and as of January 1, 2015, includes: MI, NH, and PA. The remaining states were considered non-expansion states after January 1, 2015. U.S. territories were excluded from state expansion status categorization.

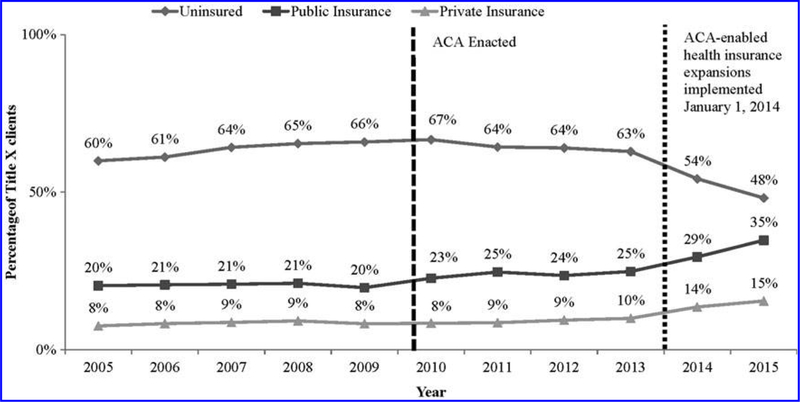

The percentage of Title X clients without health insurance decreased from 60% in 2005 to 48% in 2015, with the greatest annual decreases occurring between 2013 and 2014 (63% to 54%) and between 2014 and 2015 (54% to 48%) (Fig. 1). From 2005 to 2015, the percentage of clients with public health insurance coverage increased from 20% to 35% and the percentage of clients with private health insurance coverage increased from 8% to 15%. The largest annual increase in the percentage of clients with public insurance occurred between 2014 and 2015 (29% to 35%) and the largest annual increase in the percentage of clients with private insurance occurred between 2013 and 2014 (10% to 14%). During 2005–2009, the percentage of clients whose insurance status was unknown in FPAR declined from 12% to 6%. In following years (2010–2015), the percentage of clients with unknown insurance coverage was between 2% and 3%.

FIG. 1.

Percentage of clients receiving services at health clinics funded by Title X by insurance coverage status, Family Planning Annual Reports, 2005–2015. The dashed vertical line in the middle of the chart indicates 2010, when the ACA legislation was signed (March 23, 2010) and some provisions took effect, including the measure allowing children to stay on parent’s insurance plans until age 26. The dashed line on the right indicates January 1, 2014, when ACA-enabled Medicaid when expansions first took effect in 24 states and Washington, D.C. Private insurance plans purchased between October 1, 2013, and December 15, 2013, through the state or federal Marketplaces also began to take effect on January 1, 2014. ACA, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

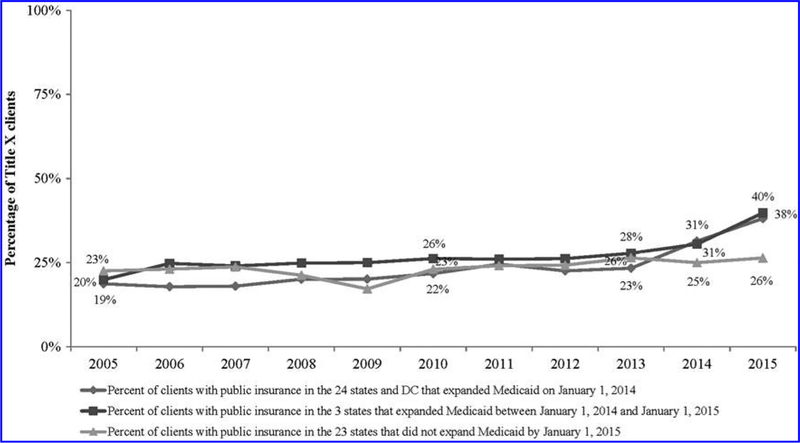

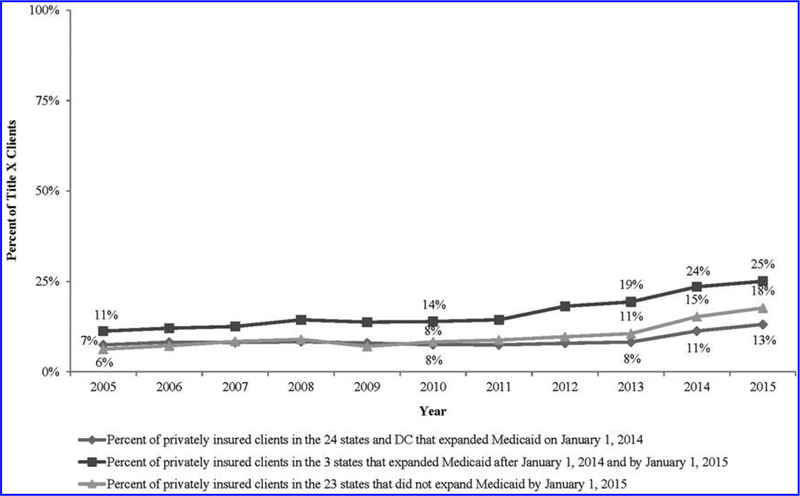

In the 2014 expansion states, the percentage of Title X clients with public insurance increased from 19% in 2005 to 38% in 2015, with the largest increases occurring between 2013 and 2014 (23% to 31%) and between 2014 and 2015 (31% to 38%) (Fig. 2). The percentage of clients with public insurance in the 2015 expansion states increased from 20% in 2005 to 40% in 2015, with the largest increase occurring between 2014 and 2015 (31% to 40%). Among the non-expansion states, the percentage of clients with public insurance was 23% in 2005 and 26% in 2015. Among the 2014 expansion states, the percentage of Title X clients with private insurance increased from 7% in 2005 to 13% in 2015, with the largest increase occurring between 2013 and 2014 (8% to 11%) (Fig. 3). For the 2015 expansion states, the percentage of clients with private insurance increased from 11% in 2005 to 25% in 2015, with the largest increase occurring between 2013 and 2014 (19% to 24%). For non-expansion states, the percentage of clients with private insurance increased from 6% in 2005 to 18% in 2015, with the largest increase occurring between 2013 and 2014 (11% to 15%).

FIG. 2.

Percentage of clients with public insurance receiving services at health clinics funded by Title X by state Medicaid expansion status, Family Planning Annual Reports 2005–2015. See the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation’s Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision for more information on state Medicaid expansion decisions.9

FIG. 3.

Percentage of clients with private insurance receiving services at health clinics funded by Title X by state Medicaid expansion status, Family Planning Annual Reports 2005–2015. See the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation’s Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision for more information on state Medicaid expansion decisions.9

In 2015, 47% of Title X clients were uninsured in the 2014 expansion states, 33% were uninsured in the 2015 expansion states, and 54% were uninsured in the non-expansion states.

Discussion

Using administrative data reported by recipients of the Title X Family Planning Program, we examined trends in client health insurance coverage. Between 2013 and 2014, there was a 9-point decline in the percentage of uninsured clients, and increases of 4 points each in the percentages with public and private coverage. The declines in the percentage uninsured and increases in public and private coverage continued into 2015. These shifts in the distribution of health insurance coverage status coincided with full rollout of the ACA insurance expansion provisions in January 2014. In addition, clients who received services in states that opted to expand Medicaid coverage had rates of public health insurance coverage that were 12–14 points higher than in non-expansion states in 2015.

Our results are consistent with other studies that have found a decrease in the percentage of people without health insurance since implementation of the ACA health insurance expansion provisions. Analyses of national data have found decreases in uninsured young adults beginning with the ACA-related provision, implemented in 2010, which allowed children younger than 26 years to stay on parental insurance plans.3,10 Decreases in uninsured nonelderly adults (ages 19–64) were observed beginning in 2014, with gains in health insurance coverage seen in private coverage obtained through ACA-enabled Marketplaces.4,11 Decreases in uninsured patients have also been noted at certain safety net providers, such as Federally Qualified Health Centers and clinics receiving Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program support.12–14 Data from the National Health Information Survey showed little change between 2005 (18.9%) and 2013 (20.4%) in the percentage of nonelderly adults (18–64 years) without health insurance, and an almost 8-point drop between 2013 (20.4%) and 2015 (12.8%).11 While we observed a substantial decrease in the percentage of Title X clients without health insurance, Title X clients remain uninsured at a higher rate compared with the national average (i.e., 48% of Title X clients were uninsured in 2015 compared with the national average of 12.8% for persons aged 18–64).11

The increase in percentage of Title X clients with health insurance coverage beginning in 2014 aligns with the implementation of key ACA provisions—namely the inception of the ACA-enabled Medicaid expansions and of state and federal health insurance Marketplaces, which commenced operation in October 2013. States have long had the option to determine Medicaid eligibility levels and expand access to family planning and reproductive health services through temporary Medicaid family planning waiver demonstration projects or permanent State Plan Amendments, which only cover family planning and related preventive care. However, the ACA-enabled Medicaid expansions allowed individuals at higher qualifying income levels (typically up to 138% of the poverty guidelines) to obtain full Medicaid benefits.15 As clients with partial health insurance coverage (i.e., single service insurance plans) were considered uninsured in our analysis, it seems likely that the increase in public coverage we observed was due to expanded Medicaid enrollment. The increase we observed in Title X clients with private insurance coverage may also be related to various changes stemming from the ACA, including the opportunity to purchase private plans through the federal or state health insurance Marketplaces, the extended coverage for young adults on their parents’ health insurance plans, and the individual and employer mandates for health insurance coverage.3,4,10,16,17 We found that states that expanded Medicaid in either 2014 or 2015 experienced increases in the percentage of privately insured clients after Marketplace plans began taking effect; however, non-expansion states experienced the largest relative increases between 2013 and 2015, which is consistent with previous findings.18

Another factor that may have contributed to the increases in health insurance coverage among Title X clients could have been OPA’s efforts, beginning in 2013, to encourage Title X clinic staff to help clients enroll in health insurance plans for which they were eligible. OPA issued competitive grants in 2014 and 2015 that provided additional funds to 28 grantees (encompassing 98 individual clinics) to provide health insurance enrollment assistance to Title X clients. While clinics that participated in this grant program saw increases in insurance enrollment, it is unlikely that those targeted efforts had a substantial impact on the national trends we observed in our study because these clinics only accounted for ~2% of the total clinics in the Title X network.

Our study is not without limitations. First, because FPAR data are aggregated and reported at the grantee level, we could not characterize uninsured clients and analyze how this group may have changed over time, which would have helped us to understand better the trends we observed. To address this limitation in the future, OPA is working on developing a data collection system that will capture standardized, encounter-level data from electronic health record systems at health clinics receiving Title X funding. Second, there were some shifts in client demographics over time, as well as a decrease in overall client volume (from ~5 million in 2005 to 4 million in 2015), which could have contributed to the trends we observed. However, many demographic factors remained consistent: the percentage of low-income clients (<101% of the poverty guidelines) and the absolute number of clients without insurance decreased over time (from ~3 million in 2005 to 1.9 million in 2015), while the absolute number of clients with public and private insurance increased (public: from ~1 million in 2005 to 1.4 million in 2015; private: from ~400,000 in 2005 to 600,000 in 2015). Third, changes in the composition of grantees and service sites by state also may have impacted trends overall and in non-expansion and expansion states over time. Finally, instructions for reporting client insurance status became more complex in 2013, when a new version of reporting guidelines stated that clients with public-paid or publicly subsidized private plans should be classified as publicly insured.19 Although the intent of this guidance was to classify private plans purchased in the Marketplaces that were subsidized by public funds, it is unknown how these reporting guidelines were implemented by the network. We presume that in practice many of these subsidized plans were actually classified as private insurance.

In addition, although our categorization of states’ Medicaid expansion is nearly identical to that used by the National Health Interview Survey,11 the primary source of national trends in insurance coverage in the United States, it differs from other analyses14,20 because of the classification of states whose expansions occurred partway through the calendar year. The two differences were as follows: we classified Michigan (expanded on April 1, 2014) as a 2015 Medicaid expansion state, while NHIS classified this state as a 2014 expander, and we classified Indiana (expanded on February 1, 2015) as a non-expansion state in our analysis, while NHIS classified this state as a 2015 expander. We also categorized six states (CA, CT, DC, MN, NJ, and WA) as 2014 Medicaid expansion states even though they had implemented elements of ACA-related Medicaid expansion before January 1, 2014.21,22 These early adopters subsequently adopted full Medicaid expansion on January 1, 2014, but the impacts from their early actions may be captured in our analysis as early as 2011, when we first observed a decline in the percentage of uninsured clients (67% in 2010 to 64% in 2011).22

Our study had several strengths. Title X data represent a federal program serving a large number of uninsured and low-income individuals, which may be generalizable to other federal safety net provider programs. Indeed, trends in insurance coverage observed in our analyses are similar to those found in a recent study of the impacts of Medicaid expansions on the national network of federally funded community health centers.14 The health insurance data captured by FPAR have been measured using a largely consistent set of definitions for health insurance coverage over time. In addition, reporting requirements ensure that all Title X grantees must report these data each year for health clinics receiving Title X funding. Furthermore, the data verification procedures employed during FPAR data entry and after electronic submission likely enhanced the quality and accuracy of the data.

Implications for practice and/or policy

Our study’s findings have implications at the individual level, as increases in health insurance coverage may mean individuals can then access a broad range of preventive healthcare services beyond reproductive health and family planning services. However, nearly half of Title X clients (~2 million persons) remained uninsured in 2015. Many may lack access to healthcare services beyond those provided at Title X clinics, since a 2011–2012 study found that 40% of women utilized family planning clinics as their only source for healthcare in the previous year.23

Our study’s findings highlight the issue of financial sustainability of Title X clinics, which has long been a concern for the Title X program. Total program revenue has declined 16% ($244 million in 2015 dollars) from 2010 to 2015, with reductions in the program’s two major sources—Medicaid and Title X—accounting for approximately half of this decline.2 The drop in revenue since 2010 has been accompanied by a 10% drop (n = 438) in the number of service sites and a 23% (n = 1.2 million) decline in the number of clients served. While other federally funded health providers, such as Section 330 grantees and the Community Health Center Program, have noted substantial improvements in their capacity to serve patients, they have also received considerable increases in federal funding,13 while Title X has experienced decreases in federal appropriations, from $317 million in 2010 to $286 million in 2015. On average, only 20% of Title X grantee revenue comprised Title X grant funding, indicating that Title X recipients rely heavily upon Medicaid reimbursements, state and local government revenue, and private third-party payers to sustain their clinical services.2 A recent analysis estimated that the Title X appropriation would need more than double to provide adequate funding for family planning and related preventive services to all low-income, uninsured women in the United States in need of these services, even after taking into account the increases in insurance coverage following the implementation of the ACA.24

Conclusion

This study of trends in health insurance coverage among Title X clients suggests that the ACA has increased access to health insurance for low-income individuals who rely on Title X for their family planning and related preventive healthcare. In fact, 2015 marked the first year since Title X began collecting health insurance coverage data that the percentage of clients with health insurance (50%) exceeded the percentage without coverage (48%). The large increase in public insurance coverage among clients receiving care in Title X health centers in Medicaid expansion states is noteworthy, as is the increase in private insurance among non-expansion states. In addition to meeting the reproductive healthcare needs of low-income insured clients, Title X health centers also provide care to a disproportionately high percentage of clients who remain uninsured, highlighting the important role of safety net providers.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Title X family planning network, which collected, compiled, and submitted the Title X Family Planning Annual Report data to the Office of Population Affairs.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Office of Population Affairs.

Author Disclosure Statement

This work was performed under employment of the U.S. Government for all authors except for Christina Fowler; the authors did not receive any outside funding. Christina Fowler works as technical lead on U.S. Department of Health and Human Services contract No. HHSP23320095651WC, Family Planning Annual Report (FPAR) Compilation Project.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Population Affairs. Office of Population Affairs. 2017. Available at: https://hhs.gov/opa Accessed December 6, 2017.

- 2.Fowler CI, Gable J, Wang J, Lasater B Family planning annual report: 2015. National Summary. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMorrow S, Kenney GM, Long SK, Anderson N Uninsurance among young adults continues to decline, particularly in Medicaid expansion states. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34:616–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMorrow S, Kenney GM, Long SK, Gates JA Marketplaces helped drive coverage gains in 2015; affordability problems remained. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:1810–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chokshi DA, Chang JE, Wilson RM Health reform and the changing safety net in the United States. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1790–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Population Affairs. Title X Family Planning Annual Report Forms and Instructions (Reissued October 2016). 2016. Available at: www.hhs.gov/opa/title-x-family-planning/research-and-data/fp-annual-reports/index.html Accessed December 6, 2017.

- 7.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2015 Poverty Guidelines. September 2015. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/2015-poverty-guidelines. Accessed January 19, 2017.

- 8.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Population Affairs. Program Requirements for Title X Funded Family Planning Projects (Version 1.0). 2014. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/opa/guidelines/program-guidelines/index.html Accessed December 6, 2017.

- 9.The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision. 2017. Available at: http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/?currentTimeframe=0 Accessed February 17, 2017.

- 10.Sommers B, Kronick R The affordable care act and insurance coverage for young adults. JAMA 2012;307:913–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zammitti E, Cohen R, Martinez M Health insurance coverage: early release of estimates from the National Health Insurance Survey January-June2016. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berry SA, Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, et al. Healthcare coverage for HIV provider visits before and after implementation of the affordable care act. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63: 387–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallace SP, Young ME, Rodriguez MA Community Health Centers play a critical role in caring for the remaining un-insured in the Affordable Care Act Era. Los Angeles, CA: Policy brief (UCLA Center for Health Policy Research), 2016(Pb2016–7):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han X, Luo Q, Ku L Medicaid expansion and grant funding increases helped improve community health center capacity. Health Affairs 2017;36:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ranji U, Bair Y, Salganicoff A Medicaid and family planning: background and implications of the ACA. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.The White House. Young adults and the affordable care act: Protecting young adults and eliminating burdens on families and businesses. Washington, DC, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sobel L, Beamesderfer A, Salganicoff A Private Insurance Coverage of Contraception. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2016. Available at: www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/private-insurance-coverage-of-contraception Accessed December 6, 2017.

- 18.Courtemanche C, Marton J, Yelowitz A Who gained insurance coverage in 2014, the first year of full ACA implementation? Health Econ 2016;25:778–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Population Affairs. Title X Family Planning Annual Report Forms and Instructions. 2013. Available at: www.hhs.gov/opa/sites/default/files/fpar-reissued-oct13_0.pdf Accessed December 6, 2017.

- 20.Courtemanche C, Marton J, Ukert B, Yelowitz A, Zapata D Early Impacts of the Affordable Care Act on Health Insurance Coverage in Medicaid Expansion and Non-Expansion States. J Pol Anal Manag 2017;36:178–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sommers B, Arntson E, Kenney G, Epstein A Lessons from early medicaid expansions under health reform: Interviews with medicaid officials. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev 2013;3:E1–E19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. The Affordable Care Act Three Years Post-Enactment. 2013. Available at: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/84291.pdf Accessed December 6, 2017.

- 23.Frost J, Gold RB, Bucek A Specialized family planning clinics in the United States: Why women choose them and their role in meeting women’s healthcare needs. Womens Health Issues 2012;22:e519–e525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.August EM, Steinmetz E, Gavin L, et al. Projecting the unmet need and costs for contraception services after the Affordable Care Act. Am J Public Health 2015;106:334–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]