Abstract

Natural products are of paramount importance in human medicine. Not only are most antibacterial and anticancer drugs derived directly from or inspired by natural products, many other branches of medicine, such as immunology, neurology, and cardiology, have similarly benefited from natural product-based drugs. Typically, the genetic material required to synthesize a microbial specialized product is arranged in a multigene biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC), which codes for proteins associated with molecule construction, regulation, and transport. The ability to connect natural product compounds to BGCs and vice versa, along with ever-increasing knowledge of biosynthetic machineries, has spawned the field of genomics-guided natural product genome mining for the rational discovery of new chemical entities. One significant challenge in the field of natural product genome mining is how to rapidly link orphan biosynthetic genes to their associated chemical products. This review highlights state-of-the-art genetic platforms to identify, interrogate, and engineer BGCs from diverse microbial sources, which can be broken into three stages: (1) cloning and isolation of genomic loci, (2) heterologous expression in a host organism, and (3) genetic manipulation of cloned pathways. In the future, we envision natural product genome mining will be rapidly accelerated by de novo DNA synthesis and refactoring of whole biosynthetic pathways in combination with systematic heterologous expression methodologies.

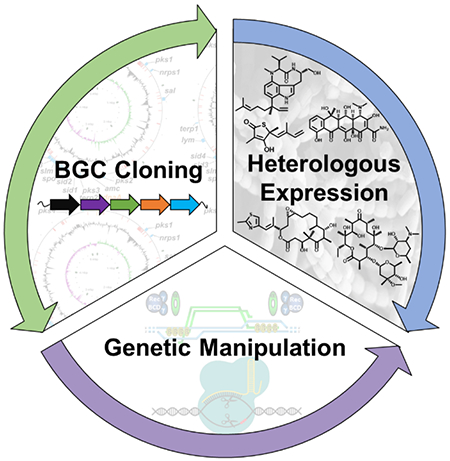

Graphical Abstract

This review covers current genetic technologies for accessing and manipulating natural product biosynthetic gene clusters through heterologous expression.

1. Introduction

Natural products, or specialized small molecules produced by living organisms, have long fascinated chemists due to their complex three-dimensional structures, which make them challenging to produce using synthetic organic chemistry.1 Perhaps more importantly, structural complexity and multidimensionality confer many natural products with potent and specific biological activities, making them privileged scaffolds in the quest to develop new medicines.2 Natural products have played an invaluable role in deepening our understanding of various cellular processes and even facilitated the discovery of important and evolutionarily conserved macromolecules, such as the protein kinase mTOR, or mechanistic target of rapamycin, which is blocked by the Streptomyces natural product rapamycin.3 Rapamycin has become a life-saving immunosuppressant drug, and the discovery of mTOR spawned a vibrant field of study uncovering its central role in physiology, metabolism, aging, and common diseases such as cancer and epilepsy.4

The ability of all living organisms to biosynthesize endogenous, specialized small molecules is genetically encoded. Making connections between isolated small molecules and the genes responsible for their construction has been particularly productive in microorganisms, which generally cluster elements involved in natural product biosynthesis along their genomes in “biosynthetic gene clusters” (BGCs).

Clustering of specialized genetic elements carries an additional benefit: the ability to clone and transfer whole BGCs to heterologous host organisms for expression and characterization. Heterologous expression of BGCs for characterization or identification of new chemical entities is advantageous for several reasons. As more and more genome sequences from diverse microbial sources become available, heterologous expression circumvents the need to develop new genetic tools to interrogate pathways from each new genus or species of interest. Furthermore, it enables characterization of BGCs from microbes that have yet to be cultured such as those identified from obligate symbionts or environmental DNA (eDNA). Successful heterologous reconstitution of a BGC allows rapid delineation of all essential specialized genes involved in the production of a microbial bio-chemical. Finally, genetic platforms for interrogation of BGCs that are developed can be optimized and universally applied, both for heterologous expression as well as rapid genetic manipulation of cloned pathways to perform biosynthetic investigations or BGC refactoring.

In this article, we review genetic platforms that have been established for heterologous expression of microbial natural products. Integrated platforms include three stages: 1) cloning and isolation of selective genomic loci containing BGCs, 2) expression in a heterologous host organism, and 3) genetic manipulation of cloned pathways for interrogation or activation (Fig. 1). Following this workflow, we highlight advancements in cloning methods, heterologous hosts, and genetic manipulation of large microbial BGCs used for successful heterologous reconstitution of various natural products (Fig. 2). Lastly, we highlight recent studies that utilize BGC refactoring, DNA synthesis, and de novo pathway design to access new chemical entities.

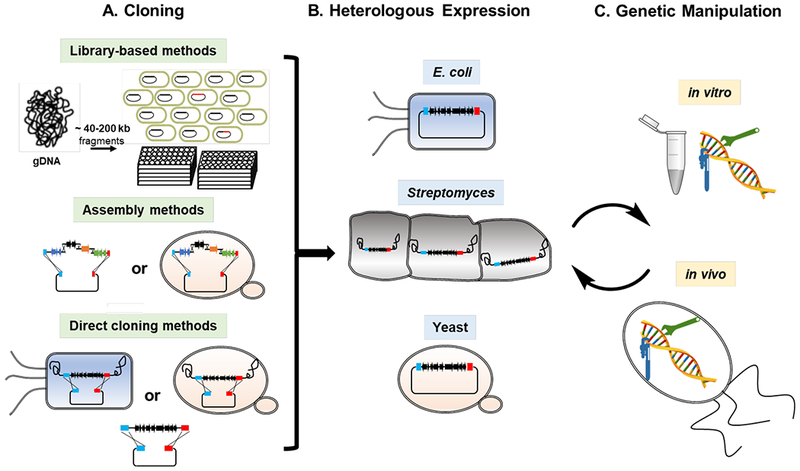

Fig. 1.

General workflow for (A) cloning, (B) heterologous expression, and (C) genetic manipulation of microbial BGCs.

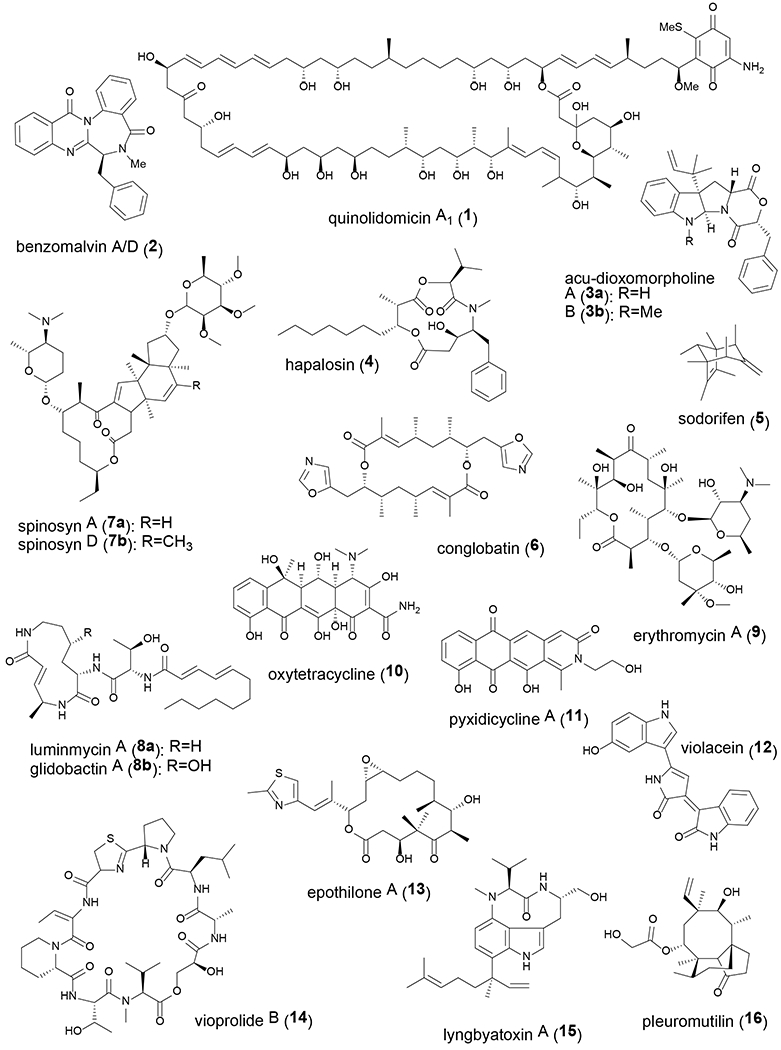

Fig. 2.

Chemical structures of natural products mentioned in this article.

2. Cloning of microbial BGCs

Due to the large size, repetitive nature, and high GC-content of many microbial BGCs, cloning has remained a challenging step in heterologous reconstitution of natural product pathways. While advancements in genome sequencing, bioinformatics, and molecular biology techniques have changed the landscape of BGC cloning over the years, many different types of cloning methods, including library-based methods, assembly methods, and direct cloning methods, have been developed and continue to be used successfully today. In this section, we highlight these techniques and their associated advantages and limitations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of BGC cloning methods and their associated advantages and disadvantages.

| Examples | Advantages | Disadvantages | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Library-based | |||||

| Cosmid/fosmid | - | Sequence-independent, whole genome cloning | Untargeted; BGCs may be split across multiple library clones | 5–14 | |

| eDNA | - | Access BGCs from uncultured microbes | Unknown producer and final product; laborious screening necessary | 15–21 | |

| BAC/PAC | LEXAS | Large insert stability | Technically challenging | 23–33 | |

| FAC | - | Library can be readily screened in A. nidulans | Requires extensive screening, some false positives | 34–37 | |

| Assembly | |||||

| in vitro | Gibson, DiPAC, TPA, SIRA, SSRTA, AREs | Technically easier; rapid and potential to be automated | Impractical or cumbersome for large BGCs | 38–54 | |

| in vivo | DNA assembler, ExRec, yTREX, AGOS | Can assemble many DNA fragments (10+) | Difficult to troubleshoot; risk of mutation | 55–70 | |

| Direct cloning | |||||

| TAR | - | Robust direct cloning of whole BGCs | Can be technically challenging; must use yeast | 72–82, 84–86 | |

| LLHR | ExoCET | Utilizes E. coli as a cloning host | Technically challenging | 88–95 | |

| in vitro | SSOA, Gibson, CATCH, plasmid rescue/recovery | Streamlined in vitro approach | Requires careful preparation and/or manipulation of gDNA | 96–106 | |

eDNA, environmental DNA; BAC, bacterial artificial chromosome; PAC, P1 artificial chromosome; FAC, fungal artificial chromosome; TAR, transformation-associated recombination; LLHR, linear-linear homologous recombination; LEXAS, library expression analysis system; DiPAC, direct pathway cloning; TPA, twin-primer assembly; SIRA, serine integrase recombinational assembly; SSRTA, site-specific recombination-based tandem assembly; ARE, artificial restriction enzyme; ExRec, overlap extension PCR-yeast homologous recombination; yTREX, yeast recombinational cloning-enabled pathway transfer and expression tool; AGOS, artificial gene operon assembly system; ExoCET, exonuclease combined with RecET recombination; SSOA, single-strand overlapping annealing; CATCH, Cas9 assisted targeting of chromosome segments.

2.1. Library-based methods

Early efforts to clone microbial BGCs relied heavily on library-based methods, which involve the generation of a clone library of random genomic DNA (gDNA) fragments in Escherichia coli. Library generation is particularly useful when complete genome sequence information is lacking, or when it is advantageous to catalogue the complete genetic material from an organism or metagenomic sample. Furthermore, library generation breaks the chromosome into smaller chunks that can be more easily sequenced and assembled than whole chromosomes and has therefore been a vital component of numerous genome sequencing efforts. Many BGCs have been cloned from cultured organisms into cosmid5–9 and fosmid10–14 libraries, which hold inserts of approximately 40 kb in size and are packaged and delivered to E. coli by bacteriophages. While these libraries hold similar sized inserts, fosmids exist at low or single copy number in E. coli cloning hosts and are therefore considered more stable than cosmids, particularly for highly repetitive DNA. Brady and colleagues have pioneered the generation of cosmid libraries for discovery and characterization of BGCs from soil metagenomic DNA,15–21 thus accessing pathways from organisms that have yet to be cultured. Cosmid libraries from environmental DNA (eDNA) can be maintained and continually re-screened for new categories of specialized biosynthetic genes.16, 19–21 Cloning of metagenomic DNA is particularly challenging due to the low enrichment and potentially low quality of genetic material from an individual microbe within a heterogeneous population, but library cloning has proven to be a successful approach for accessing BGCs from eDNA. However, BGCs cloned using these methods are often split across multiple library clones and thus need to be stitched together and trimmed before subsequent use.8, 10, 19, 21 Analysis of 540 full BGCs deposited in the MIBiG database22 as of August 2018 revealed that these pathways range in size from 204 bp (representing a small ribosomally encoded peptide) to 148,229 bp, with an average of approximately 36 kb. Although this is below the 40 kb threshold, it is likely that an average-sized BGC will be split across multiple fosmid or cosmid clones.

Library vectors that hold larger inserts include those based on bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) and P1 artificial chromosomes (PACs). Unlike cosmid and fosmid libraries, BAC and PAC libraries are prepared by direct transfer of DNA to E. coli via electroporation. High molecular weight DNA can be isolated using special techniques to promote uniform insert sizes above 100 kb, which are stably maintained within low copy number vector backbones. Several recent studies have utilized BAC library clones to characterize large BGCs (>55 kb) encoding assembly line biosynthetic pathways, which include modular polyketide synthase (PKS) and nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) gene clusters.23–27 The quinolidomicin A1 (1) BGC, which encodes a PKS and spans over 200 kb in size, was very recently cloned in a BAC library and represents the largest BGC cloned and heterologously expressed to-date.28 However, uniform, high molecular weight DNA can be difficult to isolate, and low copy number plasmids can also be more challenging to work with. Because of these technical difficulties, research groups are increasingly outsourcing large-insert library generation to companies. Several reports of large BGC cloning have leveraged PAC libraries generated by the Canadian company Bio S&T using vector pESAC13, which can be readily transferred to various Streptomyces heterologous hosts by conjugation.29–33

Recently, a group of researchers studying fungal secondary metabolism retrofitted a BAC vector backbone with an autonomously replicating sequence from Aspergillus (AMA1) to generate a self-replicating fungal artificial chromosome (FAC) that can be used for library generation.34 FAC libraries generated using this vector can be directly transferred to the host Aspergillus nidulans for heterologous expression and mass spectrometry screening for identification of new chemical entities. Libraries were constructed and screened from the gDNA of A. terrus, A. aculeatus, and A. wentii and resulted in the identification of 15 unique mass signals produced by cryptic biosynthetic machinery, a few of which have been characterized in greater detail, including benzomalvin A/D (2) and acu-dioxomorpholines A (3a) and B (3b).35–37

Library-based cloning methods have contributed greatly to our understanding of microbial BGCs and continue to be used routinely and successfully. However, library cloning is an untargeted approach in which most library clones do not contain genomic regions of interest and thus must be extensively screened. With the proliferation of publicly available genome sequence information, more targeted approaches, such as assembly and direct cloning methods, are being utilized with greater frequency.

2.2. Assembly methods

Methods that rely on in vitro assembly of BGCs from smaller fragments represent an attractive alternative to library-based approaches, as small fragments of DNA can be generated quickly and cheaply using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and are easy to work with. In 2009, Gibson and co-workers reported the in vitro assembly of very large DNA molecules leveraging the concerted action of three enzymes – a 5’ exonuclease, a DNA polymerase, and a DNA ligase – in an isothermal, single-reaction method.38 Gibson assembly kits can be purchased commercially and are used ubiquitously in molecular biology. Within the field of natural products research, Gibson assembly has been successfully used to reconstruct small BGCs, usually around 10 kb in length.39–43 Direct pathway cloning, or DiPaC, which relies on Gibson assembly, has been successfully used to clone small but also larger (20 to 55 kb) BGCs in a stepwise, combinatorial fashion for heterologous production of compounds such as hapalosin (4) and sodorifen (5).44–46 Alternatively, a method called twin-primer assembly, or TPA, is designed for assembly of PCR-amplified fragments without the use of enzymes.47 TPA relies of annealing of complementary single-stranded overhangs designed into PCR primer sequences and has been used to assemble a 31 kb plasmid at approximately 50% fidelity.47

Phage recombinases have also been used to assemble BGCs. Also referred to as integrases, these enzymes catalyze recombination across relatively short recognition sequences, often referred to as attP and attB sites, to generate new attL and attR sequence junctions. In this way, DNA fragments can be stitched together in a specific order and orientation into a self-replicating construct and selected for using selectable markers. Serine integrase recombinational assembly, or SIRA, utilizes purified bacteriophage integrases ΦC31 and Bxb1 as well as their recombination directionality factors (RDFs) to assemble multiple DNA fragments into functional plasmids.48, 49 Site-specific recombination-based tandem assembly, or SSRTA, is a similar approach that leverages other serine integrases, including ΦBT1, TG1, and ΦRv1 in addition to Bxb1.50, 51 However, when directly compared, Bxb1 displayed the highest in vitro assembly efficiency.52 Homing endonucleases, which recognize long asymmetric sequences that are therefore rarely present in natural DNA, have also been used for the iterative assembly of standardized DNA parts through a cut-and-paste mechanism similar to standard restriction-digestion and ligation cloning in a method called iBrick.53 Recently, programmable DNA-guided restriction enzymes have been developed leveraging the Argonaute enzyme from Pyrococcus furiosus, which enables the cleavage of virtually any DNA sequence and generation of defined sticky ends for facile DNA assembly.54 These artificial restriction enzymes, or AREs, are easily programmable and will likely find broad utility in biological research.

In vivo DNA assembly methods have been widely used to reconstruct large microbial BGCs. DNA assembly leveraging high rates of in vivo homologous recombination in yeast has been shown to be accurate for assembly of up to 10 fragments of DNA, which is particularly useful for large and high GC-content gene clusters that can only be amplified in 2-5 kb pieces.55–59 Several named methods, including DNA assembler,60–67 overlap extension PCR-yeast homologous recombination (ExRec),68 and yeast recombinational cloning-enabled pathway transfer and expression tool (yTREX),69 all rely on homologous recombination in yeast for assembly of multiple fragments of DNA into functional plasmids for heterologous expression of natural product BGCs. Although not as naturally recombinant as yeast, E. coli strains equipped with Red/ET recombineering machinery have also been used for in vivo assembly of BGCs in a method called artificial gene operon assembly system, or AGOS.70

While assembly methods generally require the least technical expertise and have the greatest potential for automation, they are often not feasible or cumbersome for large BGCs and present the greatest risk for introducing mutations into cloned pathways. Direct cloning methods, in which whole BGCs are directly targeted for cloning, represent the most elegant approach to obtaining BGCs for heterologous expression and are becoming increasingly user friendly.

2.3. Direct cloning methods

Yeast homologous recombination, in addition to catalyzing multi-part DNA assembly, has been extensively leveraged for direct cloning of whole BGCs with pre-defined boundaries. Transformation-associated recombination (TAR) cloning in Saccharomyces cerevisiae can be used for the selective isolation of any genomic fragment into a circular yeast artificial chromosome (YAC), which can propagate, segregate, and be selected for in yeast.71 YAC clones arise from homologous recombination between gDNA fragments, which can be prepared by random shearing or enzymatic digestion, and a linearized TAR cloning vector containing two targeting hooks with sequences identical to those flanking the genomic loci of interest. Following successful cloning in yeast, constructs are shuttled to E. coli for detailed characterization and verification by PCR, sequencing, and/or restriction digestion. For the purposes of cloning BGCs for heterologous expression, TAR cloning vectors can also include elements for transfer to and maintenance in a heterologous host organism. Moore and colleagues developed first-generation TAR cloning vectors, pCAP0172 and pCAPB02,73 which are yeast-E. coli-Streptomyces and yeast-E. coli-Bacillus shuttle vectors, respectively, and can be assembled into a cluster-specific capture vector by addition of two long homology arms of ~1 kb each. Many bacterial BGCs have been directly cloned and interrogated using these first-generation TAR vectors.73–82 However, pCAP vector backbones possess yeast origins of replication, which are essential for cloning bacterial DNA but also result in high rates of plasmid recircularization via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) to greatly increase the number of empty vectors that must be screened against. By adapting a previously established method utilizing counterselection to select against plasmid recircularization via NHEJ,83 two second-generation vectors, pCAP0384 and pCAP05,55 were developed and used to clone and express bacterial BGCs.85 These vectors also employ much shorter homology arms of 50 bp each, which simplifies the procedure for preparing cluster-specific capture vectors in addition to significantly improving the efficiency of the TAR cloning experiment by introducing a mechanism for counterselection.84 Furthermore, pCAP05 is a broad-host-range expression vector for Gram-negative host organisms, thus expanding the host range of the pCAP vector series to include organisms such as Pseudomonas and Agrobacterium.86

TAR cloning is most efficient when homologous sequences are located as closely as possible to DNA ends,87 perhaps because homologous recombination is a mechanism to repair DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) that arise during mitosis. Thus, the success of TAR cloning is also greatly enhanced if restriction sites can be identified just beyond the boundaries of the BGC of interest and the targeting hooks are designed as closely as possible to these sites. Unfortunately, this may not be feasible for many BGCs due to a lack of available restriction sites associated with commercially available restriction enzymes that do not also cut within the BGC. Recently, Lee, Larionov, and Kouprina reported a method combining CRISPR/Cas9-mediated in vitro digestion of DNA with TAR cloning, which resulted in a dramatic increase in the fraction of positive clones.88 Although this method has not yet been reported for TAR cloning of a microbial BGC for heterologous expression, the use of CRISPR/Cas9 for in vitro digestion of gDNA is generally applicable for a number of direct cloning methods and has already been used in combination with RecE catalyzed linear-linear homologous recombination (LLHR) as well as Gibson assembly (detailed below).

Reconstitution of Rac prophage enzymes RecE and RecT in E. coli enables in vivo homologous recombination of two linear DNA fragments in a method called LLHR,89 which is highly analogous to TAR cloning in yeast. While arguably not as robust, LLHR is more attractive than TAR because it uses E. coli as a cloning host, which makes it faster and also eliminates a step compared to the TAR cloning process. LLHR has been pioneered as a method for BGC cloning by Zhang, Stewart, Mϋller and colleagues and has been applied for investigation of BGCs from various microbial sources.89–93 Exonuclease combined with RecET recombination, or ExoCET, is based on the principle that direct cloning efficiencies can be improved by pre-annealing of linear vectors and target DNA using the exonuclease T4 DNA polymerase before delivery to E. coli cells.94, 95 Furthermore, LLHR operates on the same principle as homologous recombination in yeast, wherein precise digestion of gDNA prior to cloning using either commercially available restriction enzymes or CRISPR/Cas9 programmed restriction digestion greatly enhances cloning efficiencies.94

Finally, various in vitro methods have been used for direct cloning of BGCs. Single-strand overlapping annealing, or SSOA, is an in vitro approach that, like ExoCET, also utilizes restriction digestion coupled with exonuclease treatment, but does not leverage any in vivo recombination machinery.96 Direct cloning of large pathways from complex mixtures of gDNA using Gibson assembly has also been reported.97–99 In work by Leadlay and colleagues on expression of the anticancer compound conglobatin (6), a precise 41 kb fragment of DNA was generated by gDNA digestion using restriction enzymes XhoI and EcoRI, and digested DNA was carefully purified by gel electrophoresis to remove fragments less than 20 kb in size.97 Alternatively, CRISPR/Cas9 can be used for programmed DNA digestion in agarose gel plugs prior to Gibson assembly, as has been reported for Cas9 assisted targeting of chromosome segments, or CATCH, which has been successfully used for targeting up to 100 kb in a single step.98, 99 Thus, like in vivo methods, in vitro direct cloning approaches greatly benefit from careful preparation of DNA through pre-treatment and purification.

If natural restriction sites are not present at the boundaries of a BGC of interest, researchers have also relied on genetic manipulation to introduce unique sites for restriction enzymes or homing endonucleases so that BGCs can be precisely targeted for digestion and self-ligation; in various reports, this process has been referred to as plasmid recovery,100 plasmid rescue,101 or iCATCH.102 Editing of chromosomal sequences upstream and downstream of BGCs has also been used to introduce ΦBT1 or Cre-lox recombination sites to excise genomic loci via in vitro or in vivo recombination.103–106 However, an important drawback to relying on genetic manipulation is that it is a labor-intensive approach that not all natural product producing organisms are amenable to, which may be the reason why cloning and heterologous expression were pursued for BGC characterization in the first place.

While still not trivial, cloning of large BGCs has become increasingly accessible, and many viable approaches have been developed and used to isolate DNA from complex genetic backgrounds. Following successful cloning, BGCs must be transferred to a heterologous host that can stably maintain and express the exogenous DNA. Furthermore, successful heterologous reconstitution also requires that the host is equipped with all biosynthetic building blocks and non-clustered enzymatic machinery or accessory factors essential for natural product production. In the next section, we highlight various host organisms that have been developed, optimized, and used for heterologous expression of natural product BGCs.

3. Hosts for heterologous expression

There are several obvious features of a good heterologous host organism: it grows fast, is genetically manipulatable, and is easy to work with in the laboratory. However, there are many additional traits that organisms must carry, either naturally or through engineering, to enable heterologous reconstitution of natural product BGCs. Some genera of host organisms have been developed and used more extensively than others, particularly Streptomyces, as this genus has been a naturally rich source of antibiotics and other small molecule natural products over the years. There is an underlying assumption, pervasive throughout the natural products research community, that BGCs are best expressed in organisms most closely related to their original source. Although this assumption is theoretically sound, it has not been rigorously proven, in part because it becomes completely irrelevant once a suitable host organism has been identified. Although it remains essentially impossible to predict host compatibility, educated guesses can be made, particularly as we understand more about biosynthetic mechanism and regulation. For all BGCs, there will be an assortment of additional elements that need to be “borrowed” from the host organism, ranging from biosynthetic precursors such as fatty acids, amino acids, and acyl-CoAs, to enzymes that post translationally modify biosynthetic enzymes such as phosphopantetheinyl transferases (PPTases), to regulatory genes that control BGC expression. These host elements must be compatible with exogenous BGCs or independently supplied from alternative sources. It has been shown that BGCs often move by horizontal gene transfer; thus, they are frequently not conserved throughout a taxonomic group.107, 108 Conversely, this means that similar BGCs can naturally function in organisms that are not closely related phylogenetically. Regardless of whether a more closely related host is truly “superior”, it is ideal to have many different types of heterologous hosts available, particularly as we identify new BGCs from diverse microbial sources. Many studies have shown this empirically through successful expression of BGCs in some hosts but not others.15, 58, 109–112

Heterologous hosts can be engineered for enhanced expression of microbial BGCs in a background devoid of competing or contaminating pathways. General strategies for host optimization include genome minimization through deletion of native BGCs, nucleases, and proteases, as well as introduction of chromosomal integration elements, PPTases and other post translational modifying enzymes, or genes involved in precursor biosynthesis. In this section we review microbial heterologous host systems that have been developed, optimized, and used to successfully reconstitute natural product BGCs. Various bacterial and fungal genera are discussed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of heterologous hosts used for BGC expression.

| Phylum | Genus | Details | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||||

| Gram-positive | ||||

| Actinobacteria | ||||

| Streptomyces | Most widely used host, extensively optimized; site-specific BGC integration catalyzed by actinophage recombinases |

109, 113–136 | ||

|

Nonomuraea Amycolatopsis Salinispora |

All compatible with ΦC31 integrase; engineered strain S. tropica CNB-4401 represents first marine actinomycete host |

6, 137 138 139 |

||

| Saccharopolyspora | S. erythraea, native erythromycin producer, engineered for spinosad production | 140 | ||

| Firmicutes | ||||

| Bacillus | Harbors Sfp PPTase, easily transformed and integrated with BGCs but underutilized | 73, 82, 142–147 | ||

| Lactococcus | Leveraged for expression of small bacteriocin BGCs | 148–149 | ||

| Gram-negative | ||||

| Proteobacteria | ||||

| γ | Escherichia | Strains include Nissle 1917, BL21(DE3), BAP1, GB05-MtaA; also optimized for precursor flux and genetic stability | 44, 58, 74, 89, 151–167 | |

| Pseudomonas | Talented host; potential for expression of myxobacterial and Streptomyces BGCs | 40, 58, 110–111, 170–178 | ||

| δ |

Myxococcus Stigmatella Corallococcus |

M. xanthus, S. aurantiaca leveraged for expression of many myxobacterial BGCs using transposition and phage integration; can be difficult to work with and grow slowly C. macrosporus is moderately thermophilic |

99, 111–112, 171, 173, 181–183, 185–186 186 184 |

|

| α |

Agrobacterium Caulobacter Rhodobacter |

Leveraged for expression of violacein, zeaxanthin, and prodigiosin pigments, various eDNA library clones |

58, 110 110 172 |

|

| β |

Ralstonia Burkholderia |

Used for expression of carotenoid, type III PKS products from eDNA; also epothilones and vioprolides |

110, 187 110, 173, 188 |

|

| Cyanobacteria | ||||

|

Synechococcus Anabaena |

S. elongatus PCC7942, S. sp. PCC6803 Anabaena sp. PCC7120 used for expression of cyanobacterial pathways |

190–193 190, 195–196 |

||

| Fungi | ||||

| Saccharomyces | HEx platform developed for high-throughput functional evaluation of fungal BGCs | 197–211 | ||

|

Aspergillus Fusarium |

More naturally suited for expression of BGCs from filamentous fungi |

34–37, 213–218 220–223 |

2.1. Actinobacteria

To date, actinobacterial hosts of the genus Streptomyces have been most widely used for BGC expression, primarily because many bioactive natural products have been isolated from Streptomyces and therefore the greatest attention has been paid to studying their secondary metabolism and developing optimized Streptomyces hosts. Streptomyces species that have been used as heterologous hosts include S. coelicolor,113 S. avermitilis,114, 115 S. lividans,116 S. albus,117, 118 S. venezuelea,119 S. ambofaciens and S. roseosporus,120 S. flavogriseus,109, 121 S. chattanoogensis,122 and S. chartreusis.123 Additionally, fast-growing and moderately thermophilic strains of Streptomyces have been isolated and tested for heterologous expression, although these organisms have not been characterized at the strain level.124 Streptomyces hosts have been optimized to various extents using several general strategies. Genome minimization through curing of self-replicating plasmids and deletion of non-essential genes, including native BGCs, has been widely applied. Deletion of endogenous BGCs has the two-fold effect of removing sinks for biosynthetic precursors and simultaneously simplifying the host’s chemical profile.113–115, 117, 122 Additionally, empirically identified mutations in rpoB and rpsL (which encode the RNA polymerase β-subunit and ribosomal protein S12, respectively) of S. coelicolor and S. lividans pleiotropically enhance secondary metabolite production and have been introduced.113 Remodeling of global regulatory circuits through introduction of new positive regulators or up- and down-regulation of native positive and negative regulators, respectively, has also been leveraged,116, 118 in addition to expression of codon-optimized efflux pumps to reduce toxicity and aid in natural product purification.116 Please note that the Streptomyces hosts and references listed in this section are not comprehensive, as in depth review of optimized Streptomyces hosts is covered elsewhere in this issue.

Long and often repetitive natural product BGCs must be stably maintained in the host, either as an autonomously replicating sequence or integrated into the host genome. Replicative expression plasmids such as pOJ446, which is an E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vector based on the S. coelicolor A3(2) plasmid SCP2*, have been widely used.125–127 However, chromosomal integration of BGCs is more stable and, if irreversible, circumvents the need to use antibiotics for plasmid maintenance. Many BGCs have been integrated into Streptomyces genomes leveraging recombinases from actinophages, most notably ΦC31.128–130 The ΦC31 attB attachment site is naturally present in the genome of many Streptomyces species and enables site-specific integration of large BGCs into the host chromosome. Other actinophages, including TG1, SV1, ΦBT1, R4, ΦHau, and ΦJoe, have been identified, characterized, and in some cases used for BGC integration.131–133 Having access to multiple attachment sites is helpful for performing complementation experiments to confirm that gene deletion mutants do not carry polar effects. Furthermore, BGCs can be split and integrated into multiple genomic loci to simplify cloning and assist in BGC engineering.134, 135 The precise site of genomic integration could be important in a heterologous expression experiment, as it has recently been shown that gene expression can vary up to eight-fold depending on the position of chromosomal integration in S. albus.136 Thus, having access to multiple attachment sites leveraging different actinophages can be a valuable asset for heterologous expression of BGCs in Streptomyces.

ΦC31 attachment sites are also naturally present in the genomes of several other Actinobacteria and have been leveraged for BGC expression in the rare actinomycete Nonomuraea sp. strain ATCC 397276, 137 and the nocardioform actinomycete Amycolatopsis japonicum.138 Alternatively, the marine actinomycete Salinispora tropica CNB-440, which possesses several pseudo ΦC31 attachment sites, was engineered to introduce an authentic ΦC31 attachment site for integration of BGCs into the salinosporamide (sal) biosynthetic locus, simultaneously abolishing salinosporamide production to free up biosynthetic precursors.139 The resulting strain, S. tropica CNB-4401, represents the first marine actinomycete heterologous host and is readily compatible with expression vectors containing the ΦC31 integrase. Finally, Saccharopolyspora erythraea, the original producer of the antibiotic erythromycin, was used as a host for heterologous expression of the spinosad BGC, encoding production of spinosyns A (7a) and D (7b), from Saccharopolyspora spinosa via chromosomal integration by double-crossover homologous recombination.140

2.2. Firmicutes

The rod-shaped, low G+C content Firmicute Bacillus subtilis has many desirable qualities of a heterologous host organism. It produces the cyclic lipopeptide surfactin and thus harbors the promiscuous PPTase Sfp, which has been used to activate carrier proteins from diverse microbial sources.141 Thus, B. subtilis is naturally equipped with an important element for expression of assembly line BGCs. Furthermore, it has the capacity for natural genetic competence and homologous recombination, making it easy to transform and genetically manipulate, and it grows relatively fast, particularly in comparison to Streptomyces. Despite these attractive features, Bacillus has been used relatively infrequently for heterologous expression of BGCs, perhaps due to a natural reluctance to test non-Bacillus pathways in a Bacillus host organism. Consequently, there has not been the same level of investment in development and optimization of Bacillus heterologous hosts. B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens have been used to express a number of BGCs, primarily those encoding peptide products originating from other Bacilli.73, 82, 142–147 In most cases, gene clusters have been integrated into the amyE locus of B. subtilis hosts via double-crossover homologous recombination. Interestingly, Li et al. attempted to express the surfactin BGC in B. subtilis ROM77, in which the native surfactin locus is disrupted, from a self-replicating plasmid but encountered insurmountable plasmid instability, prompting the authors to build an integratable heterologous expression plasmid instead.73 Beyond Bacillus, Lactococcus lactis is another Firmicute that has been leveraged for heterologous expression of small bacteriocin BGCs responsible for production of lactococcin Z and plantaricyclin A, which are produced by other Lactococci and Lactobacilli, respectively.148, 149

2.3. Proteobacteria

Although the majority of isolated natural products have been sourced from Gram-positive Actinobacteria, Gram-negative organisms such as Proteobacteria and Cyanobacteria are increasingly being recognized as capable and underexplored producers of bioactive small molecules.150 Gram-negative Proteobacteria include many dangerous pathogens such as Salmonella, Vibrio, and Yersinia, which are difficult to treat using standard antibiotics. Conversely, Proteobacteria are also important commensals found within the microbiomes of many higher organisms, including humans. Thus, heterologous expression of proteobacterial BGCs represents an important tool for studying secondary metabolism of microorganisms that greatly influence human health and disease.

The disparate GC-content between microorganisms has often been cited as a reason for host-BGC incompatibility, although robust evidence supporting this claim is lacking. More likely, host factors that must be borrowed for heterologous production, whether regulatory or biosynthetic, may be missing or incompatible between BGC and host. Currently, it is not clear whether Gram-positive hosts can robustly express Gram-negative BGCs or vice versa, as this has not been rigorously tested or reported. Regardless, many Gram-negative bacteria are easier to work with than Streptomyces, and thus expansion of heterologous expression platforms to include more proteobacterial hosts represents a valuable endeavor, particularly for those species that grow fast, are easy to manipulate, and are more naturally suited to natural product production than E. coli.

Of course, the most obvious proteobacterial expression host is the laboratory workhorse E. coli, which belongs to the class of γ-proteobacteria. E. coli is very amenable to laboratory manipulation and, under ideal conditions, has a doubling time of only 20 minutes. Unfortunately, commonly used strains of E. coli are not naturally equipped to support expression of many natural product BGCs for several reasons; in some cases, specific pitfalls have been addressed and overcome. The luminmycin A (8a) BGC from the γ-proteobacterium Photorhabdus luminescens and the glidobactin A (8b) BGC from the β-proteobacterium Burkholderia DSM7029, both encoding hybrid NRPS/PKS pathways, have been expressed in the probiotic strain E. coli Nissle 1917 under the control of a tetracycline inducible promoter.151, 152 Transcriptional regulation appears to be a common challenge that must be overcome for BGC expression in laboratory strains of E. coli;153 for this reason, E. coli BL21(DE3), equipped with the T7 RNA polymerase (RNAP), has been used to express pathways retrofitted with the orthogonal and inducible T7 promoter. BGCs tested include those originating from other Proteobacteria,58, 74, 154 but importantly also include NRPS and PKS pathways from Streptomyces.155, 156 T7 is used extensively, particularly for E. coli protein expression, but is limited for BGC expression as it can only reliably promote transcripts up to 20 kb in length.153 In BL21(DE3), T7 is controlled by arabinose induction, which is amplified in an engineered strain, BT2, through genetic disruption of the endogenous arabinose catabolism pathway.157

Post-translational activation of biosynthetic enzymes represents another common challenge for heterologous expression of BGCs in E. coli. As the native PPTases of E. coli are often not able to effectively activate acyl or peptidyl carrier proteins involved in natural product biosynthesis,158 E. coli BAP1, which harbors a genomically integrated copy of the Sfp PPTase from B. subtilis,157 and GB05-MtaA, which harbors the MtaA PPTase from Stigmatella aurantiaca,89 were generated. Use of these strains has proven essential for heterologous expression of several assembly line biosynthetic pathways.44, 159–163 BAP1 is derived from BL21(DE3) and, in addition to Sfp, harbors a re-engineered prp operon to enhance supply of the polyketide precursor propionyl-CoA.157 Additional genetic manipulations have been made in BAP1 to further enhance precursor supply for production of the antibiotic erythromycin A (9), a glycosylated polyketide macrolide. These manipulations include deletion of ygfH, resulting in generation of E. coli TB3 to further support propionyl-CoA supply,164 and introduction of pccAB, resulting in generation of E. coli BTRAP for conversion of propionyl-CoA to methylmalonyl-CoA.157 Finally, E. coli LF01 was generated from TB3 via sequential deletion of genes from pathways capable of siphoning carbon from deoxysugar biosynthesis to improve erythromycin glycosylation.165 Although these manipulations were made specifically for enhanced heterologous erythromycin production, they demonstrate the potential versatility of E. coli to be engineered for optimal heterologous expression of any natural product BGC given a comprehensive understanding of biosynthetic processes.

Despite challenges associated with heterologous expression of assembly line biosynthetic pathways, laboratory strains of E. coli are generally well suited for production of ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides, or RiPPs. RiPPs represent an important and growing class of natural products;166 RiPP BGCs are also relatively small, making them tractable for heterologous expression and engineering. Recently, van der Donk, Tavassoli, and colleagues reported the generation of a vast library of 106 lanthipeptide analogs in E. coli, which was screened for inhibitory activity against a key protein-protein interaction involved in HIV infection.167

Because most heterologous expression experiments in E. coli rely on self-replicating plasmids as opposed to chromosomal integration, strains of E. coli have also been engineered for enhanced plasmid stability, for example E. coli BT3 and BTRA, which are also derivatives of BAP1.157 Tools for chromosomal integration of large DNA fragments in E. coli have also been developed, including a Cre-lox based system called recombinase-assisted genome engineering, or RAGE.168, 169 In theory, RAGE can be applied to a range of organisms to enable chromosomal integration of large BGCs for heterologous expression.

Beyond E. coli, the γ-proteobacterium Pseudomonas has been used extensively for BGC heterologous expression. Pseudomonas grows fast, is genetically manipulatable, and species such as P. putida are generally recognized as safe (GRAS). Furthermore, Pseudomonas appears to be more naturally suited to BGC expression than E. coli, as most Pseudomonas used for heterologous expression to-date have not been purposefully modified.40, 58, 110, 111, 170–176 P. putida KT2440 harbors only a single PPTase, but in vivo testing revealed that this PPTase was capable of effectively activating carrier proteins from S. coelicolor and several Myxobacteria.177 P. putida KT2440 has been metabolically engineered for methylmalonyl-CoA biosynthesis to enable heterologous production of PKS pathways that require this extender unit.178 Furthermore, P. putida KT2440 has been modified more extensively through a series of genomic deletions to enhance its ability to serve as a chassis for gene expression, resulting in the generation of P. putida EM383, which displays superior growth properties and improved genetic stability.179 Despite this enhanced stability, expression of large BGCs in P. putida from self-replicating plasmids is still not as reliable as chromosomal integration, and therefore robust methods for site-specific integration of large BGCs need to be further developed and optimized for this host. It is worth reiterating that, because P. putida grows fast and can be transformed quickly and easily using electroporation, testing of genetic variants using this heterologous host can be performed in a much shorter time frame than for even the fastest growing Streptomyces. Furthermore, as P. putida has demonstrated ability to activate S. coelicolor carrier proteins, it may be worthwhile to test Streptomyces BGCs in Pseudomonas heterologous hosts.

Outside of γ-proteobacteria, δ-proteobacteria of the order myxobacteria have also been leveraged as heterologous hosts. Myxobacteria are incredibly interesting bacteria that exhibit social behaviors, moving and feeding in multicellular groups called swarms. Furthermore, analogous to Streptomyces and Aspergillus, myxobacteria undergo complex morphological and developmental changes during their life cycle, forming spore-producing structures, or fruiting bodies, under conditions of starvation.180 Myxobacteria have large genomes (9-10 Mbp) relative to other bacteria and are prolific producers of natural products. Unfortunately, many species of myxobacteria do not make ideal expression hosts, as are difficult to work with and require extensive microbiological experience to culture and manipulate. Nevertheless, a few model myxobacteria have been successfully leveraged for expression of BGCs primarily from other myxobacteria, although the oxytetracycline (10) BGC from Streptomyces rimosus was also successfully reconstituted in a myxobacterial host.181 Myxococcus xanthus DK1622 has been the most widely used myxobacterial host, and a strain of M. xanthus has been generated in which the native myxochromide A BGC has been inactivated in an attempt to improve heterologous production.173, 182 Single- or double- crossover homologous recombination has been used for site-specific chromosomal integration of BGCs;181, 183 however, this can be difficult, especially for large constructs. Transposition has also been used in both M. xanthus111, 171 and Corallococcus macrosporus GT-2,184 a moderately thermophilic, faster growing myxobacteria. While more efficient than homologous recombination, integration via transposition, which is stochastic, can change host transcriptomes, leading to varying levels of heterologous compound production and preventing reproducibility between experiments.173, 185 This also makes it impossible to compare results between experiments, for example if BGCs are genetically manipulated and re-transferred to the heterologous host. Thus, Mx9 and Mx8 integrases, identified from bacteriophages, have also been successfully applied for site-specific BGC integration.100, 112, 186 It is noteworthy that the pyxidicycline A (11) BGC from Pyxidicoccus fallax An d48, which was expressed in both M. xanthus and Stigmatella aurantiaca DW4/3-1, displayed distinct, host-specific production profiles, where different analogs were favored in the hosts and native producer.186 This has also been observed for other BGCs and may indicate key differences in precursor availability, biosynthesis, or regulation across host organisms.139

Finally, various α- and β-proteobacterial hosts have been used for heterologous expression, albeit much more rarely. An eDNA library prepared using a broad-host-range cosmid vector was screened in the β-proteobacterium Ralstonia metallidurans, resulting in the identification of terpene and type III PKS products that could not be produced in E. coli.187 Subsequently, broad-host-range eDNA clones were screened in a more diverse range of proteobacterial hosts, including the α-proteobacteria Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Caulobacter vibrioides and the β-proteobacterium Burkholderia graminis, in addition to R. metallidurans, P. putida, and E. coli.110 eDNA expressed across these six hosts showed minimal overlap in host compatibility.110 A similar broad-host-range approach was taken for expression of the violacein (12) BGC from the γ-proteobacterium Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea 2ta16 and demonstrated that although the α-proteobacterium A. tumefaciens was the least phylogenetically related host organism tested, it produced the greatest yield of violacein due to differences in BGC regulation.58 Finally, Rhodobacter capsulatus was successfully engineered for expression of various pigment BGCs,172 and Burkholderida DSM 7029 has been used for heterologous production of epothilone A (13) and vioprolide B (14), which both originate from myxobacteria.173, 188

2.4. Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria are photosynthetic bacteria, found in freshwater and marine ecosystems, that have historically been a rich source of bioactive natural products and toxins.189 The cyanobacterial phylum is diverse, but unfortunately most Cyanobacteria grow slowly and are difficult to genetically manipulate. Despite these challenges, recent advances have been made toward developing genetic tools and cyanobacterial hosts for heterologous expression of intransigent BGCs. A broad-host-range vector was constructed and tested in an array of “model” cyanobacterial hosts, including Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942, Synechocystis sp. PCC6803, Anabaena sp. PCC7120, Leptolyngbya sp. BL0902, and Nostoc punctiforme ATCC29133.190 More recently, S. elongatus PCC7942 was used for heterologous expression of polybrominated diphenyl ethers, through integration of PBDE biosynthetic genes, identified in sponge-derived metagenomic cyanobacterial DNA sequences, via homologous recombination into neutral sites in the S. elongatus genome.191 Gene expression was driven by a synthetic promoter-riboswitch, providing precise control over protein production. S. elongatus PCC7942 has also been optimized specifically for polyketide production via introduction of modules that aid in PKS extender unit production, regulation (via the T7 RNAP), and post-translational modification (via the Sfp PPTase).192 S. sp. PCC6803 was successfully engineered for photosynthetic overproduction of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAA) through promoter refactoring and co-expression of the Anabaena sp. PCC7120 PPTase (APPT).193 APPT has been characterized and displays broad substrate scope and good catalytic efficiency against a range of cyanobacterial and Streptomyces carrier proteins.194 Finally, Anabaena sp. PCC7120 has been further explored for heterologous expression of BGCs using replicative plasmids, resulting in successful heterologous production of lyngbyatoxin A (15) from Moorea producens and MAA from Nostoc flagelliforme.195, 196

2.5. Fungi

Filamentous fungi, like filamentous bacteria, produce many bioactive natural products and harbor scores of uncharacterized NRPS, PKS, and miscellaneous BGCs. However, many important differences underly bacterial and fungal transcription, translation, and basic cell biology. Therefore, it seems reasonable that identifying viable fungal hosts would be very important for heterologous expression of fungal BGCs. Fungal hosts carry more biological complexity than bacteria but in most cases are easy to cultivate, genetically manipulatable, and much more tractable than higher eukaryotes.

The baker’s yeast Sacchromyces cerevisiae has been successfully used for expression of many biosynthetic genes and gene clusters from filamentous fungi.197–207 Like E. coli, S. cerevisiae is genetically tractable, grows quickly, and has been a longstanding laboratory workhorse and model organism. Also like E. coli, it is not a naturally gifted natural product producer. For this reason, S. cerevisiae has been outfitted with the NpgA PPTase from Aspergillus nidulans specifically for expression of NRPS and PKS genes.208 S. cerevisiae has also undergone extensive metabolic engineering to increase PKS precursor supply, specifically acetyl-CoA.197, 198 The majority of heterologous expression experiments in S. cerevisiae have involved only a single or few individual genes expressed from replicative vectors,199–204 although entire pathways involving more than three or four genes have also been reconstituted in their entirety.205–207 Most BGCs expressed in S. cerevisiae to date originate from other fungi, but it has also been used to reconstitute the bacterial NRPS BpsA from Streptomyces lavendulae.209 Recently, HEx (Heterologous EXpression) was established as a high-throughput platform for expression of fungal BGCs in S. cerevisiae.210 Using this platform, 41 orphan BGCs from diverse fungal species were interrogated, resulting in 22 detectable compounds.210 Finally, new methods for BGC integration into yeast chromosomes are being developed, for example a method called delta integration CRISPR-Cas, or Di-CRISPR.211

Despite many successes, there are significant differences between intron processing in filamentous fungi and yeast.212 Although intron sequences can be effectively removed by cloning from cDNA, this requires RNA isolation and also makes it difficult to clone and express multi-gene pathways. Thus, filamentous fungal hosts have also been developed. Aspergillus nidulans is a model organism that can be genetically manipulated and is highly recombinant; it has been used extensively for expression of BGCs from Aspergilli and other ascomycete fungi.34–37, 213–216 A. nidulans has been engineered through deletion of endogenous BGCs, and characterized promoters can be leveraged in this host.217 Aspergillus oryzae has been successfully used for heterologous reconstitution of the antibiotic pleuromutilin (16), a diterpene produced by the basidiomycete Clitopilus passeckerianus.218 Finally, Fusarium heterosporum ATCC 74349, an ascomycete that produces high levels of the natural product equisetin,219 has been leveraged to express BGCs from Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus terreus, Hapsidospora irregularis, and an uncharacterized fern endophyte isolated from Papua New Guinea.220–222 Furthermore, fusions of fungal PKS/NRPS genes were tested in this host strain to determine guidelines for engineering hybrid PKS/NRPS pathways.223

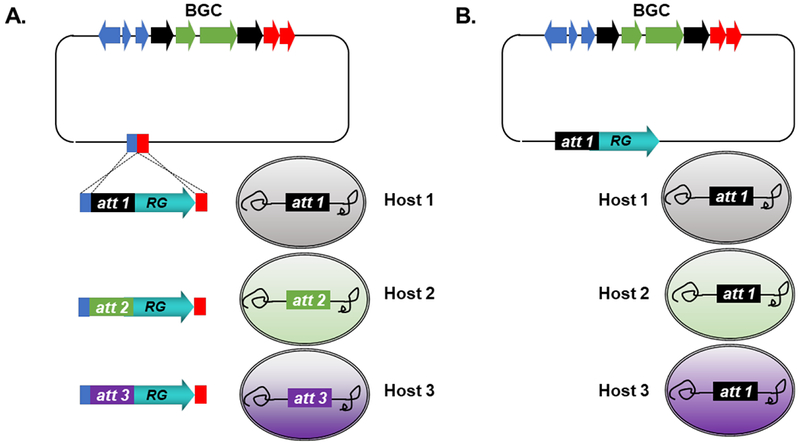

Heterologous expression of microbial BGCs, enabled by the diverse range of hosts reviewed in this section, has greatly expanded our knowledge of natural product biosynthesis, bioactivity, and regulation. While it is worthwhile to develop new and diverse host organisms, current platforms are not designed to be broadly applicable, as dual cloning and expression vectors outfitted with host-specific elements make it difficult to test expression of cloned BGCs in different hosts, particularly across bacterial and fungal phyla. More universal systems would greatly streamline the ability to test BGC expression across multiple hosts. One potential approach involves introduction of modular expression elements (ideally for site-specific chromosomal integration) after cloning, enabling vectors to be easily retrofitted for expression testing across different hosts (Fig. 3A). Alternatively, diverse hosts can be engineered to carry the same BGC integration site, such that a single vector system is broadly compatible with many different expression hosts (Fig. 3B). This could be achieved, for example, leveraging a system like recombinase-assisted genome engineering (RAGE) to introduce the same attachment site in diverse hosts organisms.169

Fig. 3.

Streamlined design of universal BGC expression platforms. (A) Modular expression vector system, leveraging knock-in of modular expression elements for BGC integration across many hosts. (B) Single vector system, compatible across several engineered hosts. RG: resistance gene; att: attachment site.

4. Genetic manipulation of cloned BGCs

Cloned constructs can be quickly edited leveraging E. coli recombineering tools such as PCR targeting and λ-Red recombination.224, 225 Therefore, cloning of BGCs also enables rapid genetic manipulation of biosynthetic pathways through gene knock-in or knock-out experiments. Edited constructs can then be re-introduced to heterologous hosts to test for expression. In this manner, BGCs can be engineered for activation or enhanced production of chemical products,226 generation of new analogs,227 or interrogation of biosynthetic mechanism.228, 229 This process can be iterated to quickly connect biosynthetic genotype and chemotype. Standard E. coli recombineering leveraging antibiotic resistance cassettes makes most gene deletion and insertion experiments routine, although care should be taken to avoid polar effects in bacteria. Alternatively, yeast can also be used, leveraging natural recombination and various auxotrophic markers or resistance cassettes, for deletion or insertion.72 This is particularly attractive for large, highly repetitive BGCs cloned into high copy number E. coli vectors, since recombineering strains of E. coli are inherently less genetically stable and could catalyze unwanted plasmid recombination resulting in BGC rearrangements or deletions. However, yeast manipulations take longer and are only possible with vectors containing yeast origins of replication and selection markers.

Selection markers flanked by FRT (flippase recognition target) sequences can be removed using Flp (flippase) recombinase-mediated excision, leaving behind a small scar sequence. This adds an additional step, and clones must be carefully screened since there is no mechanism to select for excision. Recently, marker-less deletions were successfully made in vitro using CRISPR-Cas9 in a method termed ICE (in vitro CRISPR/Cas9 mediated editing).230 While this report simplifies the process of generating marker-less deletion mutants, it remains significantly challenging to make subtle marker-less changes, for example point mutations, within large DNA constructs, as these types of manipulations would usually be performed using PCR mutagenesis. One potential application for improved marker-less mutation methods is for editing assembly line BGCs, as these generally involve large, multigene pathways. Recently, we developed a method for facile generation of point mutations in large cloned constructs, which paves the way for easy editing of large BGCs in the future.231

5. Conclusions and future perspectives

With advances in DNA sequencing technology and bioinformatics tools, researchers have identified huge untapped microbial biosynthetic potential in silico, and genomics-based approaches have become routine for natural product discovery. The diverse strategies summarized in this review are advancing our ability to leverage microbial genome sequence information for the purpose of discovering new metabolites and understanding biosynthetic logic.

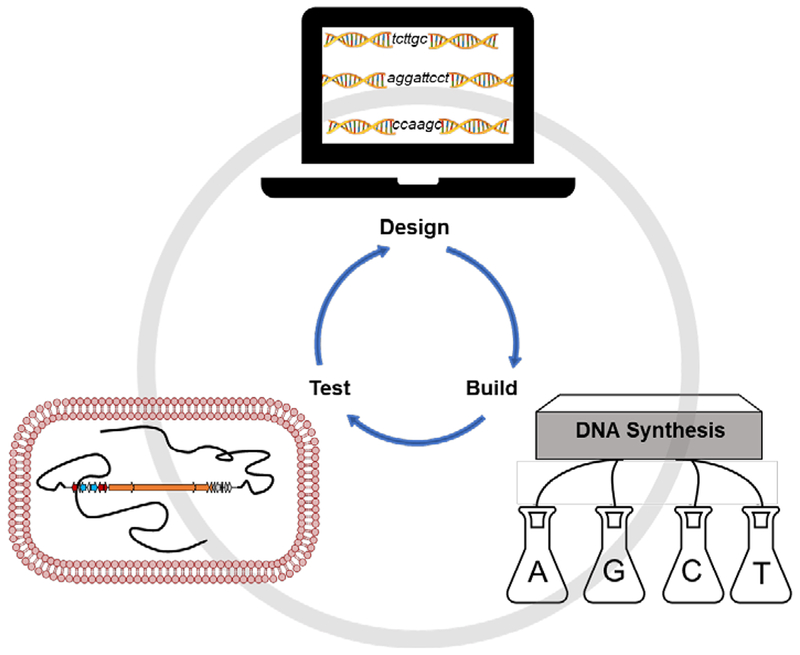

Over the past few decades, hundreds of natural product BGCs have been cloned and expressed in various heterologous hosts, the vast majority associated with known natural products (estimate based on analysis of the MIBiG database).22 Thus, the next frontier lies in eliciting expression of so-called “silent” or “cryptic” BGCs to identify their chemical products and understand their biological activity. One promising approach has been the swapping of native promoters of “silent” BGCs with well-characterized constitutive or inducible promoters. This so-called “promoter refactoring’ strategy is particularly compatible with heterologous expression platforms, in which undetermined native transcriptional regulation systems can be replaced with well-characterized and controllable regulatory elements. While this approach has garnered significant interest and enthusiasm,57, 232–236 current cloning and editing methods make it impractical to perform large-scale BGC refactoring, requiring substantial investments in time, energy, and money. In the future, we envision that DNA synthesis will play an outsized role in obtaining BGCs for functional characterization. Although currently costly and impractical for large, repetitive, and high GC-content BGCs, a small number of studies have already used de novo DNA synthesis to access and refactor BGCs less than 10 kb in size.237–239 With increasing demand for synthetic DNA driven by the field of synthetic biology,240 technical advances will likely spur decreased cost and enhanced capabilities of large-scale de novo DNA synthesis.241 Conceivably, this will shift the natural product genome mining paradigm from an empirical “clone-edit-test” workflow to a streamlined and hypothesis-driven “design-build-test” workflow (Fig. 4). De novo DNA synthesis will enable experimental characterization of numerous BGCs identified from metagenomic sequence datasets, which represent the largest genomic reservoir for small molecule discovery and currently remains largely untapped.242 Furthermore, establishing various synthetic transcriptional regulatory elements, including promoter sequences, ribosome binding sites, and terminator sequences, will expand the toolbox for BGC re-design and even enable generation of artificial biosynthetic pathways.243–249 Finally, multi-omics techniques, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, can be integrated within heterologous expression platforms to diagnose production bottlenecks in a systematic manner.250

Fig. 4.

“Design, build, test” workflow for future natural product genome mining.

One hurdle BGC re-design cannot overcome is missing or incompatible “host factors” or biosynthetic elements essential for heterologous reconstitution of natural product production, especially when working with unconventional biosynthetic pathways where we may not know that a missing factor exists at all. As mentioned previously, current host selection and testing is limited and largely based on the assumption that the ideal heterologous host is most closely phylogenetically related to the native producing organism. However, this hypothesis has not been rigorously tested and there is limited empirical evidence to support this notion, particularly for “silent” or “cryptic” BGCs. Expanding the spectrum of heterologous hosts that can be tested for BGC expression in a streamlined manner will likely enhance our ability to characterize novel BGCs. Beyond phylogeny, other biological factors such as down-scale cultivability, growth speed, transformation efficiency, and genetic amenability should also be considered in terms of the development of new heterologous hosts with potential for high-throughput screening campaigns. Finally, hosts extending into vastly distant biological domains, including archaea251 and eukaryotes such as Chlamydomonas reinhardtii,252 a green microalga, and Nicotiana benthamiana,253 a wild relative of tobacco, will hopefully experience greater development and use as we continue to explore natural product biosynthesis across the tree of life.

Briefly, although this review focuses on heterologous expression-based genome mining strategies, we would also like to direct readers to a small number of studies that have pioneered the quest for mining natural products from native producers, including genetic and chemical induction-based approaches.254–257 Furthermore, cell-free natural product biosynthesis, also referred to as enzymatic total synthesis or in vitro biosynthesis, has become a powerful approach to truly test our understanding of biosynthetic mechanism.258–263 Cell-free methods also hold potential for obtaining scalable quantities of valuable bio-chemicals.264, 265

Over the past few decades, we have witnessed a renaissance within the field of natural products research, reinvigorated by the development of genomics-guided identification of microbial BGCs. The cloning methods, heterologous hosts, and genetic editing tools cited in this review will continue to be developed and utilized for BGC characterization. We remain in the infancy of investigating natural product biosynthesis and biological activity, with many challenges still to be addressed and even greater discoveries yet to be made.

7. Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the generosity of the National Institutes of Health (N.I.H.) grants R01-GM085770 and R01-AI117712 for supporting our work on developing genetic platforms to mine microbial natural products. J.J.Z. was supported by a graduate fellowship from the National Science Foundation (N.S.F.) and N.I.H. grant F31-AI129299.

Biographies

Author Biographies

Jia Jia Zhang studied biomedical engineering at Harvard College, earning her bachelor’s degree in 2013. She completed her PhD in Marine Chemical Biology in 2019 at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (University of California San Diego), where she was an NSF graduate research fellow and NIH predoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Prof. Bradley S. Moore. Her PhD work focused on development of genetic tools for heterologous expression and genetic manipulation of natural product biosynthetic gene clusters.

Xiaoyu Tang is a research scientist at the biotech company Ginkgo Bioworks in Boston. He received his Ph.D. in Pharmaceutical Sciences from the Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen (Germany) in August 2013, where he discovered, for the first time, the genuine sulfate donors for an arylsulfate sulfotransferase. Before moving to Boston, he was a postdoc at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and J. Craig Venter Institute in the laboratories of Prof. Bradley S. Moore and Prof. Anna Edlund. His research at Scripps and JCVI focused on development of new genome mining strategies and genetics tools for discovery of genetically encoded small molecules from marine bacteria and the human microbiota, as well as study of their biosynthesis and biological roles.

Bradley Moore is Professor of Marine Chemical Biology at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Professor of Pharmaceutical Chemistry at the Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at UC San Diego. He received his B.S. in chemistry from the University of Hawaii, his PhD from the University of Washington, and was a postdoc at the University of Zurich. His research focuses on the molecular and genomic basis of natural product biosynthesis and the application of new genetic tools and biocatalysts to produce bioactive molecules.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

8. References

- 1.Nicolaou KC and Rigol S, J. Antibiot. (Tokyo), 2018, 71, 153–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman DJ and Cragg GM, J. Nat. Prod, 2016, 79, 629–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heitman J, Movva NR and Hall MN, Science, 1991, 253, 905–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabatini DM, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 2017, 114, 11818–11825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flinspach K, Westrich L, Kaysser L, Siebenberg S, Gomez-Escribano JP, Bibb M, Gust B and Heide L, Biopolymers, 2010, 93, 823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foulston LC and Bibb MJ, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 2010, 107, 13461–13466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaysser L, Tang X, Wemakor E, Sedding K, Hennig S, Siebenberg S and Gust B, Chembiochem, 2011, 12, 477–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamanaka K, Ryan KS, Gulder TA, Hughes CC and Moore BS, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2012, 134, 12434–12437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pait IGU, Kitani S, Roslan FW, Ulanova D, Arai M, Ikeda H and Nihira T, J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol, 2018, 45, 77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaysser L, Bernhardt P, Nam SJ, Loesgen S, Ruby JG, Skewes-Cox P, Jensen PR, Fenical W and Moore BS, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2012, 134, 11988–11991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantovani SM and Moore BS, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2013, 135, 18032–18035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schorn M, Zettler J, Noel JP, Dorrestein PC, Moore BS and Kaysser L, ACS Chem. Biol, 2014, 9, 301–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leipoldt F, Santos-Aberturas J, Stegmann DP, Wolf F, Kulik A, Lacret R, Popadic D, Keinhorster D, Kirchner N, Bekiesch P, Gross H, Truman AW and Kaysser L, Nat Commun, 2017, 8, 1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolf F, Leipoldt F, Kulik A, Wibberg D, Kalinowski J and Kaysser L, Chembiochem, 2018, 19, 1189–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMahon MD, Guan C, Handelsman J and Thomas MG, Appl. Environ. Microbiol, 2012, 78, 3622–3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owen JG, Charlop-Powers Z, Smith AG, Ternei MA, Calle PY, Reddy BV, Montiel D and Brady SF, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 2015, 112, 4221–4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iqbal HA, Low-Beinart L, Obiajulu JU and Brady SF, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2016, 138, 9341–9344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bitok JK, Lemetre C, Ternei MA and Brady SF, FEMS Microbiol. Lett, 2017, 364, fnx155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hover BM, Kim SH, Katz M, Charlop-Powers Z, Owen JG, Ternei MA, Maniko J, Estrela AB, Molina H, Park S, Perlin DS and Brady SF, Nat Microbiol, 2018, 3, 415–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peek J, Lilic M, Montiel D, Milshteyn A, Woodworth I, Biggins JB, Ternei MA, Calle PY, Danziger M, Warrier T, Saito K, Braffman N, Fay A, Glickman MS, Darst SA, Campbell EA and Brady SF, Nat Commun, 2018, 9, 4147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng Z, Kim JH and Brady SF, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2010, 132, 11902–11903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medema MH, Kottmann R, Yilmaz P, Cummings M, Biggins JB, Blin K, de Bruijn I, Chooi YH, Claesen J, Coates RC, Cruz-Morales P, Duddela S, Dusterhus S, Edwards DJ, Fewer DP, Garg N, Geiger C, Gomez-Escribano JP, Greule A, Hadjithomas M, Haines AS, Helfrich EJ, Hillwig ML, Ishida K, Jones AC, Jones CS, Jungmann K, Kegler C, Kim HU, Kotter P, Krug D, Masschelein J, Melnik AV, Mantovani SM, Monroe EA, Moore M, Moss N, Nutzmann HW, Pan G, Pati A, Petras D, Reen FJ, Rosconi F, Rui Z, Tian Z, Tobias NJ, Tsunematsu Y, Wiemann P, Wyckoff E, Yan X, Yim G, Yu F, Xie Y, Aigle B, Apel AK, Balibar CJ, Balskus EP, Barona-Gomez F, Bechthold A, Bode HB, Borriss R, Brady SF, Brakhage AA, Caffrey P, Cheng YQ, Clardy J, Cox RJ, De Mot R, Donadio S, Donia MS, van der Donk WA, Dorrestein PC, Doyle S, Driessen AJ, Ehling-Schulz M, Entian KD, Fischbach MA, Gerwick L, Gerwick WH, Gross H, Gust B, Hertweck C, Hofte M, Jensen SE, Ju J, Katz L, Kaysser L, Klassen JL, Keller NP, Kormanec J, Kuipers OP, Kuzuyama T, Kyrpides NC, Kwon HJ, Lautru S, Lavigne R, Lee CY, Linquan B, Liu X, Liu W, Luzhetskyy A, Mahmud T, Mast Y, Mendez C, Metsa-Ketela M, Micklefield J, Mitchell DA, Moore BS, Moreira LM, Muller R, Neilan BA, Nett M, Nielsen J, O’Gara F, Oikawa H, Osbourn A, Osburne MS, Ostash B, Payne SM, Pernodet JL, Petricek M, Piel J, Ploux O, Raaijmakers JM, Salas JA, Schmitt EK, Scott B, Seipke RF, Shen B, Sherman DH, Sivonen K, Smanski MJ, Sosio M, Stegmann E, Sussmuth RD, Tahlan K, Thomas CM, Tang Y, Truman AW, Viaud M, Walton JD, Walsh CT, Weber T, van Wezel GP, Wilkinson B, Willey JM, Wohlleben W, Wright GD, Ziemert N, Zhang C, Zotchev SB, Breitling R, Takano E and Glockner FO, Nat. Chem. Biol, 2015, 11, 625–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tu Q, Herrmann J, Hu S, Raju R, Bian X, Zhang Y and Muller R, Sci. Rep, 2016, 6, 21066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu M, Wang Y, Zhao Z, Gao G, Huang SX, Kang Q, He X, Lin S, Pang X, Deng Z and Tao M, Appl. Environ. Microbiol, 2016, 82, 5795–5805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deng Q, Zhou L, Luo M, Deng Z and Zhao C, Synth Syst Biotechnol, 2017, 2, 59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crusemann M, Reher R, Schamari I, Brachmann AO, Ohbayashi T, Kuschak M, Malfacini D, Seidinger A, Pinto-Carbo M, Richarz R, Reuter T, Kehraus S, Hallab A, Attwood M, Schioth HB, Mergaert P, Kikuchi Y, Schaberle TF, Kostenis E, Wenzel D, Muller CE, Piel J, Carlier A, Eberl L and Konig GM, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl, 2018, 57, 836–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H, Jiang H, Haltli B, Kulowski K, Muszynska E, Feng X, Summers M, Young M, Graziani E, Koehn F, Carter GT and He M, J. Nat. Prod, 2009, 72, 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hashimoto T, Hashimoto J, Kozone I, Amagai K, Kawahara T, Takahashi S, Ikeda H and Shin-Ya K, Org Lett, 2018, 20, 7996–7999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones AC, Gust B, Kulik A, Heide L, Buttner MJ and Bibb MJ, PLoS One, 2013, 8, e69319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castro JF, Razmilic V, Gomez-Escribano JP, Andrews B, Asenjo JA and Bibb MJ, Appl. Environ. Microbiol, 2015, 81, 5820–5831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qin Z, Munnoch JT, Devine R, Holmes NA, Seipke RF, Wilkinson KA, Wilkinson B and Hutchings MI, Chem. Sci, 2017, 8, 3218–3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tu J, Li S, Chen J, Song Y, Fu S, Ju J and Li Q, Microb Cell Fact, 2018, 17, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kepplinger B, Morton-Laing S, Seistrup KH, Marrs ECL, Hopkins AP, Perry JD, Strahl H, Hall MJ, Errington J and Allenby NEE, ACS Chem. Biol, 2018, 13, 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bok JW, Ye R, Clevenger KD, Mead D, Wagner M, Krerowicz A, Albright JC, Goering AW, Thomas PM, Kelleher NL, Keller NP and Wu CC, BMC Genomics, 2015, 16, 343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clevenger KD, Bok JW, Ye R, Miley GP, Verdan MH, Velk T, Chen C, Yang K, Robey MT, Gao P, Lamprecht M, Thomas PM, Islam MN, Palmer JM, Wu CC, Keller NP and Kelleher NL, Nat. Chem. Biol, 2017, 13, 895–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robey MT, Ye R, Bok JW, Clevenger KD, Islam MN, Chen C, Gupta R, Swyers M, Wu E, Gao P, Thomas PM, Wu CC, Keller NP and Kelleher NL, ACS Chem. Biol, 2018, 13, 1142–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clevenger KD, Ye R, Bok JW, Thomas PM, Islam MN, Miley GP, Robey MT, Chen C, Yang K, Swyers M, Wu E, Gao P, Wu CC, Keller NP and Kelleher NL, Biochemistry, 2018, 57, 3237–3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA 3rd and Smith HO, Nat Methods, 2009, 6, 343–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Linares-Otoya L, Linares-Otoya V, Armas-Mantilla L, Blanco-Olano C, Crusemann M, Ganoza-Yupanqui ML, Campos-Florian J, Konig GM and Schaberle TF, Microbiology, 2017, 163, 1409–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vior NM, Lacret R, Chandra G, Dorai-Raj S, Trick M and Truman AW, Appl. Environ. Microbiol, 2018, 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mevaere J, Goulard C, Schneider O, Sekurova ON, Ma H, Zirah S, Afonso C, Rebuffat S, Zotchev SB and Li Y, Sci. Rep, 2018, 8, 8232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cai X, Challinor VL, Zhao L, Reimer D, Adihou H, Grun P, Kaiser M and Bode HB, Org Lett, 2017, 19, 806–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yurkovich ME, Jenkins R, Sun Y, Tosin M and Leadlay PF, Chem. Commun. (Camb.), 2017, 53, 2182–2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greunke C, Duell ER, D’Agostino PM, Glockle A, Lamm K and Gulder TAM, Metab Eng, 2018, 47, 334–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.D’Agostino PM and Gulder TAM, ACS Synth Biol, 2018, 7, 1702–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duell ER, D’Agostino PM, Shapiro N, Woyke T, Fuchs TM and Gulder TAM, Microb Cell Fact, 2019, 18, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liang J, Liu Z, Low XZ, Ang EL and Zhao H, Nucleic Acids Res, 2017, 45, e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colloms SD, Merrick CA, Olorunniji FJ, Stark WM, Smith MC, Osbourn A, Keasling JD and Rosser SJ, Nucleic Acids Res, 2014, 42, e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olorunniji FJ, Merrick C, Rosser SJ, Smith MCM, Stark WM and Colloms SD, Methods Mol. Biol, 2017, 1642, 303–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang L, Ou X, Zhao G and Ding X, J. Bacteriol, 2008, 190, 6392–6397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang L, Zhao G and Ding X, Sci. Rep, 2011, 1, 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang X, Tang B, Ye Y, Mao Y, Lei X, Zhao G and Ding X, Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai), 2017, 49, 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu JK, Chen WH, Ren SX, Zhao GP and Wang J, PLoS One, 2014, 9, e110852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Enghiad B and Zhao H, ACS Synth Biol, 2017, 6, 752–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim JH, Feng Z, Bauer JD, Kallifidas D, Calle PY and Brady SF, Biopolymers, 2010, 93, 833–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bilyk O, Sekurova ON, Zotchev SB and Luzhetskyy A, PLoS One, 2016, 11, e0158682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bauman KD, Li J, Murata K, Mantovani SM, Dahesh S, Nizet V, Luhavaya H and Moore BS, Cell Chem Biol, 2019, 26, 724–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang JJ, Tang X, Zhang M, Nguyen D and Moore BS, MBio, 2017, 8, e01291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shi Y, Jiang Z, Li X, Zuo L, Lei X, Yu L, Wu L, Jiang J and Hong B, Acta Pharm Sin B, 2018, 8, 283–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shao Z, Zhao H and Zhao H, Nucleic Acids Res, 2009, 37, e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shao Z, Luo Y and Zhao H, Mol. Biosyst, 2011, 7, 1056–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shao Z, Luo Y and Zhao H, Methods Mol. Biol, 2012, 898, 251–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shao Z and Zhao H, Methods Enzymol, 2012, 517, 203–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shao Z, Rao G, Li C, Abil Z, Luo Y and Zhao H, ACS Synth Biol, 2013, 2, 662–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shao Z and Zhao H, Methods Mol. Biol, 2013, 1073, 85–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luo Y, Huang H, Liang J, Wang M, Lu L, Shao Z, Cobb RE and Zhao H, Nat Commun, 2013, 4, 2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]