Sigma factors are utilized by bacteria to control and regulate gene expression. Some sigma factors are activated during times of stress to ensure the survival of the bacterium. Here, we report the presence of a sigma factor that is encoded on a plasmid that leads to cellular death after DNA damage.

KEYWORDS: sigma factor, RNAP, plasmid, LexA, cell death, RNA polymerases, plasmids, sigma factors

ABSTRACT

Laboratory strains of Bacillus subtilis encode many alternative sigma factors, each dedicated to expressing a unique regulon such as those involved in stress resistance, sporulation, and motility. The ancestral strain of B. subtilis also encodes an additional sigma factor homolog, ZpdN, not found in lab strains due to being encoded on the large, low-copy-number plasmid pBS32, which was lost during domestication. DNA damage triggers pBS32 hyperreplication and cell death in a manner that depends on ZpdN, but how ZpdN mediates these effects is unknown. Here, we show that ZpdN is a bona fide sigma factor that can direct RNA polymerase to transcribe ZpdN-dependent genes, and we rename ZpdN SigN accordingly. Rend-seq (end-enriched transcriptome sequencing) analysis was used to determine the SigN regulon on pBS32, and the 5′ ends of transcripts were used to predict the SigN consensus sequence. Finally, we characterize the regulation of SigN itself and show that it is transcribed by at least three promoters: PsigN1, a strong SigA-dependent LexA-repressed promoter; PsigN2, a weak SigA-dependent constitutive promoter; and PsigN3, a SigN-dependent promoter. Thus, in response to DNA damage SigN is derepressed and then experiences positive feedback. How cells die in a pBS32-dependent manner remains unknown, but we predict that death is the product of expressing one or more genes in the SigN regulon.

INTRODUCTION

Propagation and cultivation of bacteria in the laboratory have been shown to select for enhanced axenic growth and genetic tractability in a process called domestication. The model genetic organism Bacillus subtilis is an example of a commonly-used domesticated bacterium, as the laboratory strains differ substantially from the ancestor from which they were derived. For example, lab strains are defective for biofilm formation, are reduced in motility, are auxotrophic for one or more amino acids, and are deficient in the ability to synthesize multiple antibiotics, a potent surfactant, and a viscous slime layer (1–5). While many traits were lost during the domestication of laboratory strains, one important trait was gained: high-frequency uptake of extracellular DNA in a process called natural genetic competence. Later, it was shown that increased genetic competence was also due to genetic loss, in this case due to the loss of the endogenous plasmid pBS32 (6, 7).

pBS32 is a large, 84-kb, low-copy-number plasmid that has a separate replication initiation protein and a high-fidelity plasmid partitioning system (6, 8–10). Moreover, pBS32 has been shown to encode an inhibitor of competence for DNA uptake (ComI) (7) and an inhibitor of biofilm formation (RapP) that regulates cell physiology (11–13). In addition, approximately one-third of the pBS32 sequence encodes a cryptic prophage-like element, and cell death is triggered in a pBS32-dependent manner following treatment with the DNA-damaging agent mitomycin C (MMC) (7, 14–17). pBS32-dependent cell death upon mitomycin C treatment requires a plasmid-encoded sigma factor homolog, ZpdN, and artificial ZpdN induction was shown to be sufficient to trigger cell death (17). How ZpdN is activated by the presence of DNA damage and the mechanism by which ZpdN promotes cell death are unknown.

Here, we show that ZpdN functions as a bona fide sigma factor which directs RNA polymerase to transcribe a large regulon of genes carried on pBS32. Based on our findings, we rename ZpdN SigN and propose a SigN-dependent consensus sequence for transcriptional activation. We show that SigN induction triggers immediate loss of cell viability, even as cells continue to grow and the cell culture increases in optical density (OD). We characterize the sigN promoter region and find multiple promoters that activate its expression, including a DNA damage-responsive LexA-repressed promoter and a separate promoter that governs autoactivation. Finally, the SigN regulon does not appear to include the pBS32 putative prophage region, and thus, cell death may be prophage independent. The gene or genes responsible for pBS32-mediated cell death remain unknown, but we infer that they must reside within the plasmid, expressed by RNA polymerase and SigN.

RESULTS

SigN is repressed by LexA.

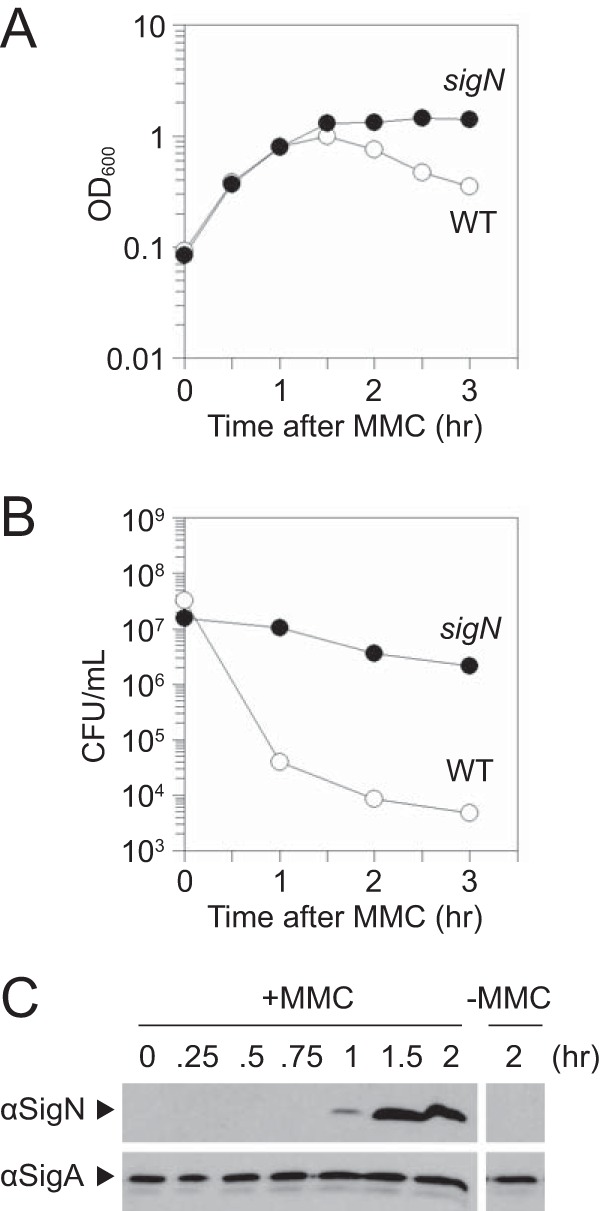

SigN (formerly ZpdN) is a sigma factor homolog encoded on the plasmid pBS32 that is necessary and sufficient for pBS32-mediated cell death (17). Consistent with previous results, treatment of cells deleted for the PBSX and SPβ prophages (14, 18–21) with the DNA-damaging agent mitomycin C (MMC) caused a 3-fold decrease in optical density (OD) from peak absorbance, and the decrease in OD was abolished in cells deleted for sigN (17) (Fig. 1A). To determine the effect of MMC on cell viability, viable counting was performed by dilution plating over a time course following MMC addition. Addition of MMC caused a rapid and immediate decline in CFU such that the number of viable cells decreased 3 orders of magnitude even as the OD increased for three doublings (compare Fig. 1A and B). As with loss of OD, mutation of sigN abolished the MMC-dependent decrease in cell viability (Fig. 1B). We conclude that pBS32-mediated cell death occurs prior to, and independently of, transient cell growth and the subsequent decline in OD. We further conclude that SigN is required for all pBS32-dependent death-related phenotypes thus far observed.

FIG 1.

SigN is required for loss of cell viability after MMC treatment. (A) Optical density (OD600) growth curve of wild type (open circles, DK607) and sigN mutant (closed circles, DK3287). The x axis is the time of spectrophotometry after MMC addition. (B) CFU growth curve of wild type (open circles, DK607) and sigN mutant (closed circles, DK3287). The x axis is the time of dilution plating after MMC addition. (C) Western blot analysis of wild-type DK607 cell lysates harvested at the indicated time after MMC addition and probed with either anti-SigN antibody or anti-SigA antibody. On the right is a single panel of the same strain for comparison 2 h after mock MMC addition.

To determine if and when SigN was expressed relative to MMC treatment, Western blot analysis was conducted. SigN protein was first detected 1 h after MMC treatment and continued to increase in abundance thereafter, whereas the vegetative sigma factor, SigA (σA), was constitutive and constant (Fig. 1C). Loss of cell viability appeared to occur soon after MMC addition prior to observable SigN protein (e.g., 0.5 h. after addition [Fig. 1B]), and thus we inferred that SigN was expressed and active at levels below the limit of protein detection. To determine whether sigN transcription occurs soon after MMC treatment, the upstream intergenic region of sigN (PsigN) (Fig. 2A) was cloned upstream of the gene encoding β-galactosidase, lacZ, and inserted at an ectopic site in the chromosome (aprE::PsigN-lacZ). Expression from PsigN was low but increased 10-fold within an hour after MMC addition (T1), and the increase in expression was not dependent on the presence of pBS32 (Fig. 3A).

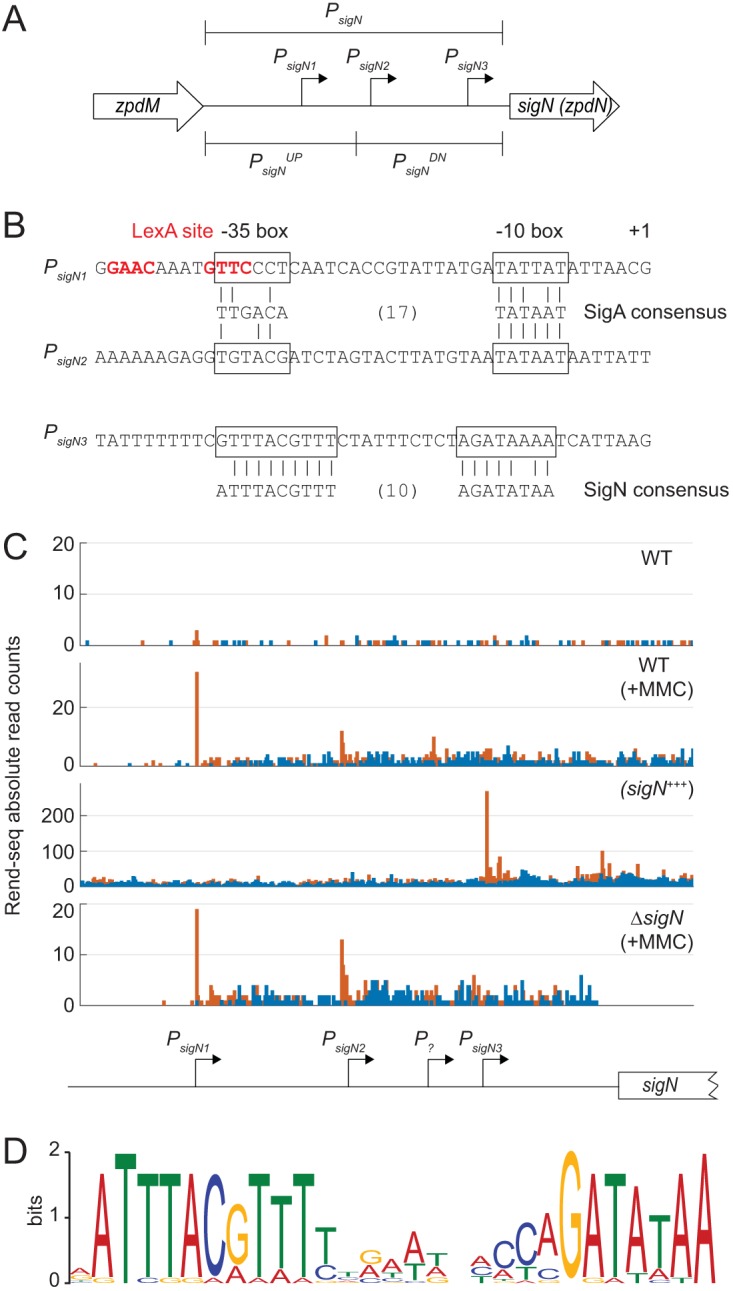

FIG 2.

The sigN promoter region. (A) A schematic of the promoter region of sigN. Open arrows indicate reading frames. Bent arrows indicate promoters. Promoter regions are indicated by brackets. (B) Promoter sequences. Boxes surround −35 and −10 regions relative to the +1 transcriptional start site. Below the promoters are SigA and SigN consensus sequences with vertical lines to indicate a consensus match. (C) Rend-seq data for the indicated genotypes: WT (DK607), WT+MMC (DK607 induced for 2 h with MMC), sigN+++ (DK1634 induced for 1 h with 1 mM IPTG), and ΔsigN+MMC (DK3287 induced for 2 h with MMC). Orange peaks represent absolute read counts for 5′ ends, and blue peaks represent absolute read counts for 3′ ends. Below is a cartoon indicating the location of the promoter believed to be responsible for the transcriptional start sites predicted above relative to the sigN coding region. Note that the peaks stop abruptly in the last panel due to deletion of the sigN gene. Information on Rend-seq is included in Table S3. Data that mapped to the plasmid in Fig. S2 are represented after normalization per million reads. (D) SigN consensus sequence generated by MEME sequence analysis using the promoters listed in Table 2.

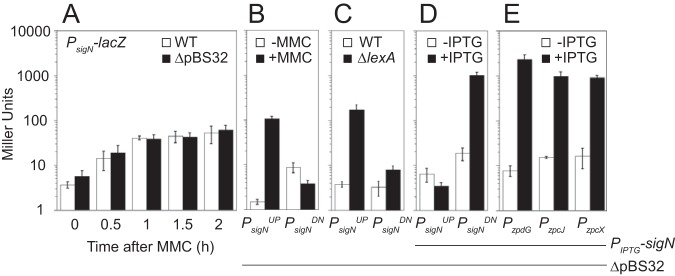

FIG 3.

The sigN promoter region is repressed by LexA and autoactivated. (A) β-Galactosidase activity of a PsigN-lacZ reporter in the presence (open bars) and absence (closed bars) of pBS32 measured at the indicated time points following 800 nM MMC addition. The following strains were used to generate this panel: DK4784 (WT) and DK5066 (ΔpBS32). (B) β-Galactosidase activity of either a PsigNUP-lacZ or PsigNDN-lacZ reporter in the presence (closed bars) and absence (open bars) of 800 nM MMC (1 h incubation). The following strains were used to generate this panel: DK5657 (PsigNUP-lacZ ΔpBS32) and DK5658 (PsigNDN-lacZ ΔpBS32). (C) β-Galactosidase activity of either a PsigNUP-lacZ or PsigNDN-lacZ reporter in the presence (open bars) and absence (closed bars) of LexA. The following strains were used to generate this panel: DK7291 (PsigNUP-lacZ ΔpBS32), DK7292 (PsigNDN-lacZ ΔpBS32), DK7259 PsigNUP-lacZ ΔpBS32 lexA), and DK7260 (PsigNDN-lacZ ΔpBS32 lexA). (D) β-Galactosidase activity of either a PsigNUP-lacZ or PsigNDN-lacZ reporter in a strain containing an IPTG-inducible SigN construct grown in the presence (closed bars) and absence (open bars) of 1 mM IPTG. The following strains were used to generate this panel: DK5657 (PsigNUP-lacZ ΔpBS32) and DK5658 (PsigNDN-lacZ ΔpBS32). (E) β-Galactosidase activity of a PzpdG-lacZ, PzpcJ-lacZ, or PzpcX-lacZ reporter in a strain containing an IPTG-inducible SigN construct grown in the presence (closed bars) and absence (open bars) of 1 mM IPTG. The following strains were used to generate this panel: DK5970 (PzpdG-lacZ ΔpBS32), DK5968 (PzpcJ-lacZ ΔpBS32), and DK5969 (PzpcX-lacZ ΔpBS32). Error bars are the standard deviation from three replicates. Data used to generate each panel are included in Table S5A to E. All panels use the same Y-axis.

Rend-seq analysis of the sigN promoter region. The same data as in Fig. 2C re-presented after normalization per million reads that mapped to the plasmid. Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.9 MB (932KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Rend-seq data table. List of primers used in the Rend-seq assay. Download Table S3, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (12.9KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

β-Galactosidase activity in Miller units. Each table (A to F) lists the numerical values of each β-galactosidase assay performed in Miller units and identifies the corresponding figure. Download Table S5, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (16.8KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

To map the MMC response within the sigN promoter region, we split PsigN into two fragments, an upstream fragment called PsigNUP and a downstream fragment called PsigNDN (Fig. 2A). Both fragments were cloned upstream of lacZ and separately integrated into an ectopic site of the chromosome in a strain deleted for pBS32 and both chromosomal prophages, PBSX and SPβ (all strains are shown in Table 1). Basal expression from PsigNUP was at background levels but increased 100-fold when MMC was added (Fig. 3B). In contrast, expression from PsigNDN was at a constitutively low level and did not increase upon addition of MMC (Fig. 3B). We conclude that transcription of sigN is activated by MMC treatment, that the PsigNUP region contains an MMC-responsive promoter, and that MMC-dependent expression was controlled by a chromosomally encoded regulator as induction was not dependent on the presence of pBS32.

TABLE 1.

Strains

| Strain | Genotype (reference) |

|---|---|

| 3610 | Wild type |

| DS4203 | rpoC-hisX6Ω neo(kan) |

| DK297 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX (17) |

| DK451 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔpBS32 (17) |

| DK607 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔcomI |

| DK1634 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔcomI amyE::Physpank-zpdNwkRBS spec (17) |

| DK2862 | aprE::Phag-lacZ cat comIQ12L |

| DK3287 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔcomI ΔsigN (17) |

| DK4401 | amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec aprE::PsigN-lacZ cat |

| DK4669 | amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PalfA-lacZ mls |

| DK4670 | amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PrepN-lacZ mls |

| DK4671 | amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PcomI-lacZ mls |

| DK4673 | amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PzpbK-lacZ mls |

| DK4725 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔcomI amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PcomI-lacZ mls |

| DK4784 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX aprE::PsigN-lacZ cat |

| DK4943 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔcomI amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec aprE::PsigN-lacZ cat |

| DK4948 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔcomI amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PalfA-lacZ mls |

| DK4949 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔcomI amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PrepN-lacZ mls |

| DK4994 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔcomI amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PzpbK-lacZ mls |

| DK5066 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔpBS32 aprE::PsigN-lacZ cat |

| DK5655 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔcomI amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PsigNUP-lacZ mls |

| DK5656 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔcomI amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PsigNDN-lacZ mls |

| DK5657 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔpBS32 amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PsigNUP-lacZ mls |

| DK5658 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔpBS32 amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PsigNDN-lacZ mls |

| DK5968 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔpBS32 amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PzpcJ-lacZ mls |

| DK5969 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔpBS32 amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PzpcX-lacZ mls |

| DK5970 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔpBS32 amyE::Physpank-sigNwkRBS spec thrC::PzpdG-lacZ mls |

| DK7259 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔpBS32 lexA::mls aprE::PsigNUP-lacZ cat |

| DK7260 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔpBS32 lexA::mls aprE::PsigNDN-lacZ cat |

| DK7291 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔpBS32 aprE::PsigNUP-lacZ cat |

| DK7292 | ΔSPβ ΔPBSX ΔpBS32 aprE::PsigNDN-lacZ cat |

One candidate for an MMC-responsive, chromosomally-encoded regulator is the transcriptional repressor protein LexA. LexA often binds sequences that overlap promoters to inhibit access of RNA polymerase holoenzyme (22, 23), and sequence analysis predicted a putative LexA-inverted repeat binding site located within the PsigNUP fragment (24, 25) (Fig. 2B). Moreover, target promoters are exposed and expression is derepressed when LexA undergoes autoproteolysis upon DNA damage like that caused by MMC (22, 23, 26). To determine if PsigNUP was LexA repressed, LexA was mutated in a background deleted for pBS32 and the two chromosomal prophages, PBSX and SPβ. Mutation of lexA dramatically increased expression from PsigNUP but not PsigNDN (Fig. 3C). We conclude that LexA either directly or indirectly inhibits expression of a promoter present in PsigNUP and that the MMC response was LexA mediated.

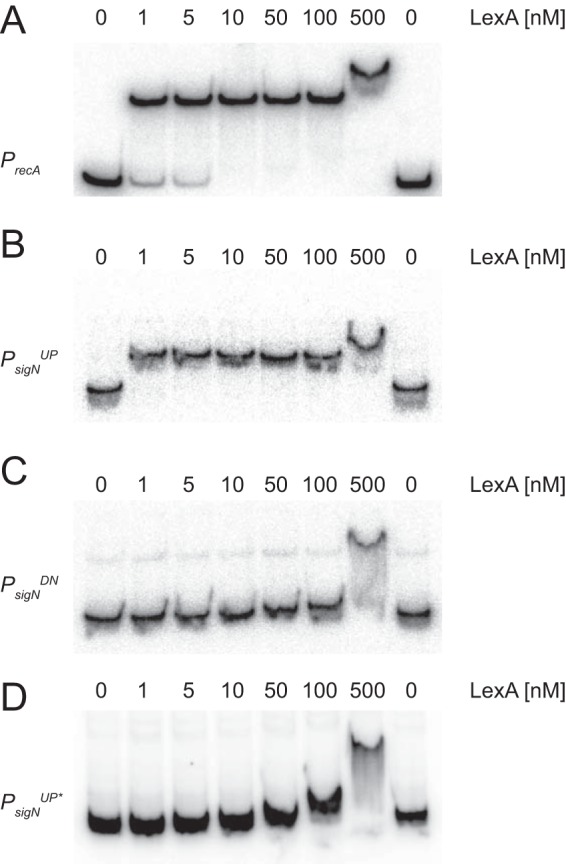

One way that LexA might inhibit expression from PsigNUP is if it bound directly to the DNA. To determine whether LexA bound directly to the PsigNUP region, LexA was purified and added to various labeled DNA fragments in an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). Consistent with direct, high-affinity binding, purified LexA caused an electrophoretic mobility shift in both the previously established target promoter PrecA (23) (Fig. 4A) and the PsigNUP promoter region (Fig. 4B) at protein levels as low as 1 nM. LexA binding was specific as the affinity was reduced 500-fold for the PsigNDN promoter (Fig. 4C). Moreover, LexA binding was specific for the putative LexA inverted repeat sequence as mutation of the sequence (GAAC>TTAC) within PsigNUP reduced binding affinity 100-fold (Fig. 4D). We conclude that LexA binds to the PsigNUP promoter region and represses transcription.

FIG 4.

LexA binds to the PsigNUP promoter region. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed with radiolabeled DNA of PrecA (A), PsigNUP (B), PsigNDN (C), and PsigNUP* (D) mutated for the putative LexA binding site. Purified LexA protein was added to each reaction mixture at the indicated concentration.

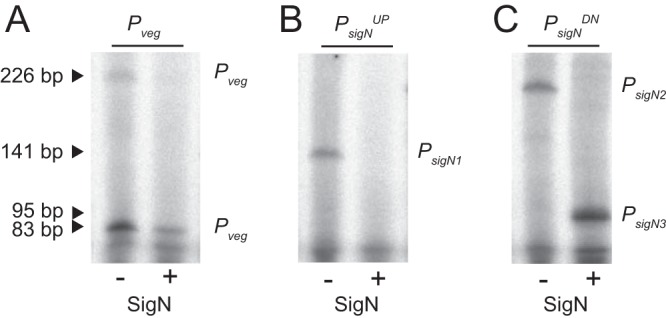

LexA often binds over the top of promoter elements (16), and sequence analysis suggested that the LexA inverted repeat in PsigNUP might rest immediately upstream of, and overlap, a putative SigA-dependent −35 promoter element (Fig. 2B). To determine whether PsigNUP contained a SigA-dependent promoter, RNA polymerase (RNAP) holoenzyme with SigA bound was purified from B. subtilis and used in in vitro transcription reactions (Fig. 5). Consistent with promoter activity, transcription product was observed when SigA-RNAP was mixed with either a known SigA-dependent promoter control, Pveg (Fig. 5A, left lane), or the experimental PsigNUP (Fig. 5B, left lane). A transcription product was also observed when SigA-RNAP was mixed with the PsigNDN promoter fragment (Fig. 5C, left lane), consistent with low-level constitutive expression observed from reporters with that fragment (Fig. 3B). We conclude that there are two SigA-dependent promoters within the PsigN region, one within the PsigNUP fragment and one within the PsigNDN fragment.

FIG 5.

SigN is a sigma factor that drives transcription in vitro. In vitro transcription assays using Pveg (left), PsigNUP (middle), and PsigNDN (right) promoter fragments in the presence (+) and absence (−) of a 5× molar ratio of SigN added to RNA polymerase holoenzyme purified from B. subtilis. The predicted transcriptional products resulting from PsigN1, PsigN2, and PsigN3 are indicated. Two products were observed from Pveg likely due to proper termination (short product) and terminator read-through (long product).

To determine transcriptional start sites, Rend-seq (end-enriched transcriptome sequencing [RNA-seq]) analysis was performed for the entire B. subtilis transcriptome in the presence and absence of MMC treatment. Rend-seq achieves end enrichment by sparse fragmentation of extracted RNAs, which generates fragments containing original 5′ and 3′ ends, as well as a smaller amount of fragments containing internal ends (27, 28). Rend-seq indicated that expression of sigN was low in the absence of induction (Fig. 2C) but a 5′ end appeared within the PsigNUP region when MMC was added, the location of which was consistent with the SigA −10 promoter element predicted earlier (Fig. 2B) and supported later by in vitro transcription (Fig. 5B, left lane). We define the SigA-dependent promoter within PsigNUP as PsigN1. Rend-seq also indicated a weak but MMC-independent 5′ end within PsigNDN that was consistent with the in vitro transcription product originating from that fragment (Fig. 5C, left lane). Moreover, sequences consistent with SigA-dependent −35 and −10 promoter elements were identified upstream of the 5′ end within PsigNDN (Fig. 2B). We define the weak constitutive SigA-dependent promoter within PsigNDN as PsigN2. We conclude that there are two SigA-dependent promoters driving sigN expression and that PsigN1 is both strong and LexA repressed.

SigN is a sigma factor that activates its own expression.

Rend-seq analysis also indicated a second 5′ end within the PsigNDN fragment that would result in a slightly shorter transcript (Fig. 2C, peak marked P?). The shorter transcript could indicate either a highly specific RNA cleavage site in the 5′ upstream untranslated region of sigN or the presence of a third promoter with an individual start site. If there was a second promoter within PsigNDN, the promoter was presumably not dependent on SigA, as only one SigA-dependent transcript was observed from this fragment in in vitro transcription assays (Fig. 5C, left lane). One candidate for an alternative sigma factor that could drive expression of the third putative promoter is SigN itself. SigN is weakly homologous to extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors, and ECF sigma factors are often autoregulatory (29). Consistent with autoactivation, induction of SigN increased expression from PsigNDN 100-fold but did not increase expression from PsigNUP (Fig. 3D). We conclude that sigN expression is controlled by at least three promoters: a LexA-repressed SigA-dependent promoter, PsigN1; a weak constitutive SigA-dependent promoter, PsigN2; and a third promoter that was SigN dependent.

One way in which a promoter could be SigN dependent is if SigN is a bona fide sigma factor that directs its own transcription. To determine whether SigN had sigma factor activity, RNAP-SigA holoenzyme was purified from B. subtilis and purified SigN protein was added in 5-fold excess to in vitro transcription reaction mixtures (30–32). Addition of SigN reduced levels of the SigA-dependent Pveg, PsigN1, and the PsigN2-derived transcripts, consistent with SigN competing with, and displacing, SigA from the RNA polymerase core (Fig. 5A and B, right lanes). Moreover, a new, shorter transcript appeared within PsigNDN that was SigN dependent (Fig. 5C, right lane). To map the location of the shorter transcript, Rend-seq was conducted on a strain that was artificially induced for SigN expression. Consistent with the in vitro transcription results, an intense SigN-dependent 5′ end was detected within the PsigNDN region which we infer is due to the presence of a promoter here called PsigN3 (Fig. 2C). We note that the PsigN3-dependent transcript did not align with the original transcript peak from P? indicated by Rend-seq analysis, and thus, at least three and possibly more promoters may be present upstream of sigN. Moreover, both the P? and PsigN3-dependent peaks in the MMC-treated Rend-seq were abolished in sigN mutant cells, but only PsigN3 was SigN stimulated (Fig. 2C). We conclude that SigN is a sigma factor that is necessary and sufficient for inducing expression from PsigN3.

Mapping of the Rend-seq transcriptional start site allowed prediction of the PsigN3 promoter sequence (Fig. 2B). To determine the SigN regulon and consensus sequence, 5′-end Rend-seq products that increased at least 10-fold after artificial SigN induction were collected, and 40 bp of sequence upstream was compiled by MEME (33) (Fig. 2D and Table 2). A consensus sequence emerged that was consistent with the −35 and −10 regions predicted for PsigN3 (Fig. 2B and D). Three separate promoter regions predicted to be regulated by SigN were cloned upstream of a promoterless lacZ gene and inserted at an ectopic site in the chromosome in a strain deleted for pBS32. In each case, the expression of the reporter was low during normal growth conditions but increased 100-fold when sigN was induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Fig. 3E). We conclude that SigN is a plasmid-encoded sigma factor that is necessary and sufficient for the expression of a regulon gene encoded on pBS32, and we infer that the expression of one or more genes within the SigN regulon is responsible for pBS32-mediated cell death.

TABLE 2.

SigN-dependent promoters on pBS32

| Promotera | Sequenceb | Operonc | Functiond | Fold changee |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sigN | TTTTCGTTTACGTTTCTATTTCTCTAGATAAAATCATTAAG | sigN | Sigma factor | 101 |

| zpaB | TTCTCATTTACGTTTTAGAAAGACTAGATATAAAGATTACG | zpaB | DNA gyrase | 152.5 |

| zpaD | TCTTATTTACATAACTGGTTATGCCGGATAAAAGAAGATAG | zpaDE | Unknown | 38 |

| zpbP | CTACCAATTTACGTTTCACCATTCTCAGATATAAATATATT | zpbP | Unknown | 158.4 |

| zpbS | TTTTGATTTACGAATTCATATTCATAGATATAAGTATAAAA | zpbS | PG interaction | 333.2 |

| zpbW | TCCATTAATTTACATATGGAAAATTACGGATATAATCGTTA | zpbW | Regulator | 178 |

| zpbY | GAAAATCAATTTACGTTTTCAAAGGCACAGATATAATAACA | zpbYZ zpcABCD | Unknown | 226 |

| zpcE | TTTTTGATTTACGTTTCTAAAACCCAAGATATAAAAGATAT | zpcEFGH | Nucleotide synth. | 339.6 |

| zpcJ | AATTAATTTACGTTTTCCAAGAACCAGATATAAATAAAAAG | zpcJK | Nucleotide synth. | 245.9 |

| zpcL | TTTTGATTTACGTTTTTAATACTCCAGATATAAATATTAAG | zpcLM | Nucleotide synth. | 202.5 |

| zpcN | TTATGATTTACGTTTTTGTTTACCCAGATAAAATAACAAAG | zpcNOP | Unknown | 356.7 |

| zpcU | GCTTGATTTACGTTTTAAAAACCCCAGATATAATAACGAAG | zpcUV | Exonuclease | 263 |

| zpcX | CATTAATTTACGTTTTCGAATCACCAGATATAAATAAAGAG | zpcXYZ | Nucleotide synth. | 309.2 |

| zpdB | TTTCAATTTACGTTTTCGAATCACCAGATATAAATACAAAG | zpdBCDEF | Nucleotide synth. | 176.3 |

| zpdG | ATCCAATTTACGTTTTTGCCGGTCCAGATATAAATACTTTG | zpdG | DNA Pol III | 401 |

| zpdH1 | TCATAATTTACATTTCTGTTATAACCGATATAATACCCTCA | zpdHIJKLM | Nucleotide synth. | 85 |

| zpdH2 | AAATGATTTACGTTTTTCAATAACCAGATATAAATATAAAG | zpdHIJKLM | Nucleotide synth. | 297.7 |

| zpbQ | TGTGGTTTACGTTTTAATAGAGCCAGATATAATCATACCAA | zpbQR | Unknown | Predicted |

| zpcR | AATTTACGTTTCAGGTGATCCAGATATAATAACAAAAAATA | zpcJKLMNOPQRSTUV | Unknown | Predicted |

Promoter named by the first gene carried on the transcript predicted by Rend-seq analysis.

Sequence of promoter obtained by taking the −40 to +1 position relative to the transcript predicted by Rend-seq analysis and used to generate Fig. 2D. Sequence matching the consensus is boldfaced.

Operon obtained by the 3’ end of the transcript predicted by Rend-seq analysis.

Function of gene/operon interpreted from BLAST results published in the work of Konkol et al. (7). PG, peptidoglycan; synth., synthesis; Pol, polymerase.

Fold change calculated from Rend-seq values (SigN+++/WT). “Predicted” indicates that the Rend-seq did not indicate that the gene was a direct SigN target but that sequences upstream of the coding region consistent with the SigN consensus sequence were detected by bioinformatics.

DISCUSSION

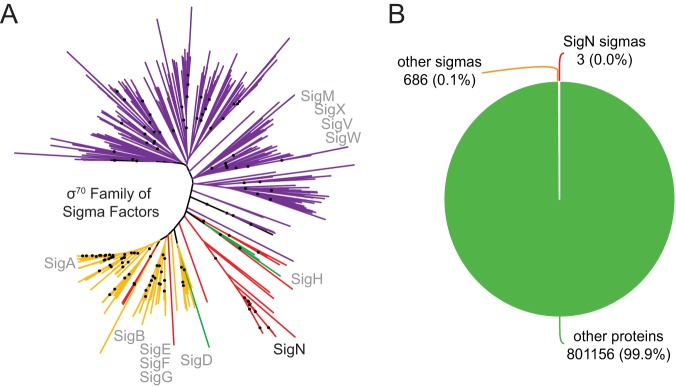

The pBS32-encoded protein SigN (formerly ZpdN) was shown to induce pBS32-mediated cell death and exhibit weak homology to sigma factors (17). Here, we show that SigN has sigma factor activity in vitro, and phylogenetic analysis suggests that SigN may represent a novel subclass of alternative sigma factors (Fig. 6A). Moreover, we used Rend-seq analysis to determine the regulon of genes under SigN control and the SigN consensus binding sequence (Fig. 2D and Table 2). Two additional SigN targets encoded on pBS32 were predicted using an unbiased search with the consensus sequence and may be subject to additional regulation (Table 2). A few seemingly unrelated chromosomal loci exceeded our threshold for determining SigN-induced targets, but subsequent bioinformatic analysis failed to find SigN promoters in the chromosome (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). Thus, the SigN regulon appears to be predominantly restricted to pBS32, at least in B. subtilis, and chromosomal effects could be either indirect or spurious.

FIG 6.

SigN distribution and phylogeny. (A) A phylogenetic tree indicating the relationships between members of the σ70 family of proteins. Sigma factors of the σ70 family were collected from 24 diverse bacterial genomes (Table S6). The colors represent which sigma factors were identified in the collection using the specified sigma factors from B. subtilis: gold, vegetative sigma, SigA (NCBI accession no. BAA25730.1); red, plasmid sigma, SigN (NCBI accession no. YP_008244202.1); green, stationary-phase sigma, SigH (NCBI accession no. QCJ19226.1); purple, extracytoplasmic (ECF) sigma, SigM (NCBI accession no. NP_388833.1). The relative location of SigN is labeled in black. The relative locations of other B. subtilis sigma factors are labeled in gray. Black dots indicate the locations of branches with bootstrap values greater than 70%. SigN homologs may represent a novel class of alternative σ70 sigma factors, but we cannot conclude this with certainty from the present analysis due to the absence of strong bootstrap values in the deepest branches of the tree. The tree can be visualized online at https://itol.embl.de/tree/1401827363250201560954077. (B) A pie chart indicating the frequency of sigma factors encoded on plasmids relative to the total number of plasmid-encoded proteins taken from a set of over 6,000 naturally occurring plasmids (34). The number of each class is given as an absolute value and as a percentage divided by all of the proteins encoded from the plasmid collection.

Rend-seq data of chromosomal genes. List of upregulated genes and corresponding fold change that was observed during SigN overexpression in the presence of pBS32. Download Table S4, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (13.6KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Genomes used for sigma 70 homolog sequence analysis. List of genomes used to obtain sigma 70 homologs for sequence analysis in Fig. 6B. Download Table S6, XLSX file, 0.01 MB (13.9KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

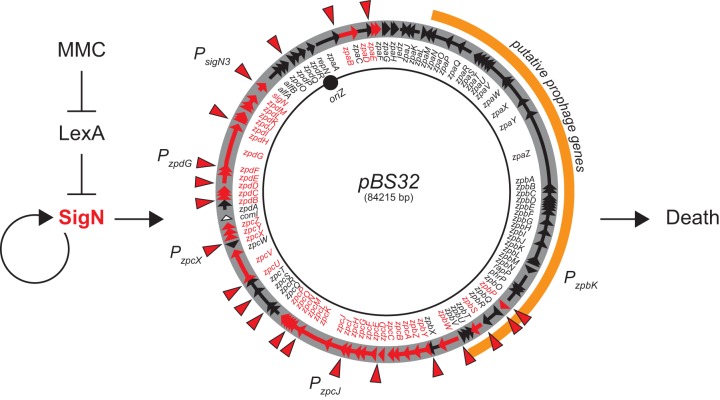

Plasmid-encoded sigma factors are rare (34) (Fig. 6B), and we note that SigN homologs were also found in the chromosomes of some bacteria. Moreover, alternative sigma factors or analogs thereof are sometimes encoded within prophage elements (35–38), and pBS32 appears to encode a cryptic prophage. Whether pBS32 is, in its entirety, a P1-like plasmid prophage (39) or whether a phage secondarily lysogenized into a preexisting plasmid is unknown (17). Similar to, and perhaps consistent with, other lysogenic prophages in B. subtilis, DNA damage by MMC triggers hyperreplication of pBS32 and initiates pBS32-mediated cell death (16, 17, 40). Here, we show that MMC induces SigN-directed plasmid gene expression via the chromosomally encoded transcriptional repressor LexA (Fig. 7). LexA represses the PsigN1 promoter, and MMC-mediated DNA damage promotes LexA autoproteolysis and derepression (26, 41–43). Derepression of PsigN1 leads to vegetative SigA-dependent expression of SigN, and SigN accumulation locks the system into an activated state by positive feedback at the PsigN3 promoter. SigN directs not only its own expression but an entire regulon on pBS32, which includes many genes homologous to those involved in nucleotide metabolism and DNA replication (7) (Table 2; Fig. 7). SigN activation causes pBS32 copy number to increase and either directly or indirectly promotes cell death (17).

FIG 7.

Model of pBS32-mediated cell death. MMC-mediated DNA damage causes LexA autoproteolysis and derepression of sigN expression. SigN is a sigma factor that directs RNA polymerase to increase its own expression (creating positive feedback) and the expression of a regulon of genes on pBS32. Activation of genes within the SigN regulon results in cell death. pBS32 is represented as a circle. Arrows within the circle indicate reading frames. The location of SigN-dependent promoters is indicated by red arrowheads. Reading frames and gene names that are expressed by SigN are indicated in red. T bars indicate inhibition, and arrows indicate activation. In black are the locations of specific promoters mentioned in the text.

How SigN promotes pBS32 hyperreplication is unknown. Replication of pBS32 requires the plasmid-encoded initiator protein RepN, and artificial overexpression of RepN was sufficient to increase plasmid copy number 100-fold (8). Thus, SigN could increase plasmid copy number by activating RepN expression, but repN did not increase in expression by Rend-seq analysis when SigN was artificially expressed. Moreover, the expression of a reporter in which the promoter of repN was fused to β-galactosidase also failed to increase when SigN was artificially induced (Fig. S1). We conclude that SigN does not directly activate repN transcription to promote plasmid hyperreplication. Moreover, pBS32 is normally a low-copy-number plasmid that requires active partitioning by the AlfAB system (10, 44, 45). Hyperreplication and/or imminent cell death may obviate active plasmid partitioning, and indeed, induction of SigN decreased expression from a reporter construct generated with the PalfAB promoter region (10, 44) (Fig. S1). Repression of alfAB appears to be indirect, however, as curing of pBS32 relieved SigN-dependent inhibition (Fig. S1). How SigN promotes hyperreplication remains unclear, but it may be an indirect effect caused by the mechanism of cell death.

SigN does not activate the replication initiator, partitioning system, competence inhibitor, or prophage structural genes. β-Galactosidase activity of strains containing either PsigN-lacZ, PrepN-lacZ (promoter of the replication initiator protein RepN), PalfA-lacZ (promoter of the partitioning system AlfAB), PcomI-lacZ (promoter of the competence inhibitor ComI), or PzpbK-lacZ (promoter of the long prophage structural gene operon) in the absence (open bars) or presence (closed bars) of IPTG. Reporter expression was measured in cells containing (left panel) or lacking (right panel) pBS32. The following strains were used to generate this panel: DK4401 (PsigN-lacZ ΔpBS32), DK4670 (PrepN-lacZ ΔpBS32), DK4669 (PalfA-lacZ ΔpBS32), DK4671 (PcomI-lacZ ΔpBS32), DK4673 (PzpbK-lacZ ΔpBS32), DK4943 (PsigNI-lacZ), DK4949 (PrepN-lacZ), DK4948 (PalfA-lacZ), DK4725 (PcomI-lacZ), and DK4994 (PzpbK-lacZ). Error bars are the standard deviation from three replicates. Data used to generate each panel are included in Table S5F. Download FIG S1, PDF file, 0.05 MB (49.5KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

How SigN and pBS32 promote cell death is complex. In the presence of pBS32, cells activated for SigN decrease in viability 1,000-fold even as cells increase in optical density for three generations. Thus, toxicity likely is not due to direct inhibition of a(n) essential component(s), and instead, something essential appears to be depleted and not replaced. Hyperreplication of the plasmid may deplete nucleotide pools, but at present we cannot determine whether hyperreplication and death are linked or separate phenotypes. Death might be mediated by the prophage structural and lytic genes, and we note that a SigN homolog is encoded by VPE25, a phage that infects Enterococcus (46). SigN-dependent promoters, however, appear to be largely excluded from the prophage region (Fig. 7), and while prophage gene expression increased in Rend-seq, the increase might have been due to the increase in plasmid copy number alone. Moreover, expression of a reporter in which the PzpbK promoter of the phage structural operon (as predicted by Rend-seq) was fused to β-galactosidase was found to be pBS32 dependent but SigN insensitive (Fig. S1). Finally, large deletions of the prophage structural genes did not abolish pBS32-mediated cell death (17). Thus, SigN-mediated cell death may be separate from prophage gene expression, at least in B. subtilis.

Alternative sigma factors may be activated to promote gene expression for the purpose of adapting to environment stress (47, 48). Here, we show that SigN is a sigma that is derepressed in response to DNA damage and in turn leads to cell death. Why a plasmid encodes a sigma factor that kills its host is unclear, unless perhaps the entire plasmid is a defective prophage and SigN, at one time, promoted lytic conversion (17). The pBS32 plasmid also encodes ComI, an inhibitor of horizontal transfer by natural competence (7). Perhaps, ComI was needed to suppress DNA uptake because the import of single-stranded DNA creates a low-level DNA damage response that could have derepressed LexA and spuriously initiated SigN-mediated cell death during transformation (40, 49). Alternatively, SigN might be activated independently of the DNA damage response. We note that there is a third weak but constitutive promoter (PsigN2) that also drives expression of SigN. The function of PsigN2 and the reason that PsigN2 is insufficient to promote SigN-mediated cell death are unknown. We speculate, however, that PsigN2 may either provide for additional environmental regulation on SigN or merely be a vestige of former regulation. Ultimately, why B. subtilis retains a potentially lethal plasmid and a sigma factor that promotes cell death is unknown.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

B. subtilis strains were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) (10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, 5 g NaCl per liter) or on LB plates fortified with 1.5% Bacto agar at 37°C. When appropriate, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: 5 μg/ml kanamycin, 100 μg/ml spectinomycin, 5 μg/ml chloramphenicol, 10 μg/ml tetracycline, and 1 μg/ml erythromycin with 25 μg/ml lincomycin (mls). Mitomycin C (MMC; DOT Scientific) was added to the medium at the indicated concentration when appropriate. Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG; Sigma) was added to the medium as needed at the indicated concentration.

Strain construction.

All constructs were first introduced into the domesticated strain PY79 or into the pBS32 cured strain (DS2569) by natural competence and then transferred into the 3610 background using SPP1-mediated generalized phage transduction (49). Strains were also produced by transforming directly into the competent derivatives of 3610: DK607 (ΔcomI) or DK1042 (Q-to-L change at position 12 encoded by comI). All strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. All primers used in this study are listed in Table S2.

Plasmids. List of plasmids used in this study. Download Table S1, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (12.8KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Primers. List of primers used in this study. Download Table S2, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (14.1KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

(i) lacZ reporter constructs.

To generate the β-galactosidase (lacZ) reporter construct aprE::PsigN-lacZ cat, PCR was utilized to amplify the promoter region of sigN using the primer set 4500/4528 from B. subtilis 3610 chromosomal DNA and primer set 4438/4501 was used to amplify the aprE up region and Catr from DK2862, while primer set 4527/4441 was used to amplify the aprE down region and lacZ from DK2862. These DNA fragments were ligated together in a Gibson isothermal assembly (ITA) reaction (see below) for 1 h at 60°C. Cementing PCR was performed using primer set 4438/4441 and the product was cleaned up using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). The resulting DNA fragment was transformed into DK1042.

To generate the PsigNUP and PsigNDN β-galactosidase reporter constructs at thrC, the promoter region of sigN was amplified via PCR with the primer set 6089/6090 for PsigNUP and 6087/6088 for PsigNDN from B. subtilis 3610 chromosomal DNA. Each PCR product was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and cloned independently into the EcoRI and BamHI sites of plasmid pDG1663, which carries an erythromycin resistance marker and a polylinker upstream of the lacZ gene between the two arms of the thrC gene to create pATB9 and pATB10, respectively. These plasmids were transformed into DK1042.

To generate the PsigNUP and PsigNDN β-galactosidase reporter constructs at aprE, the first half of the promoter was PCR amplified using primers 4500 and 4707 from B. subtilis 3610 chromosomal DNA. The second half of the promoter was amplified using primer set 4708/4528 from B. subtilis 3610 chromosomal DNA. For PsigNUP, the flanking regions of AprE were amplified as described above. For PsigNDN, the flanking regions were amplified with the following primer sets: aprE up region and Catr (4438/4498) and aprE down region and lacZ (4527/4441) from DK2862. Each promoter region was fused to the respective flanking arms of the aprE region using Gibson ITA as described above. The fused and amplified fragments were transformed into DK1042.

To generate the PzpcJ, PzpcX, and PzpdG β-galactosidase reporter constructs, primer sets were used in the following order to amplify each promoter region: 6276/6277 (PzpcJ), 6278/6279 (PzpcX), and 6280/6281 (PzpdG). Each promoter region was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and subsequently cloned independently into the EcoRI and BamHI sites of plasmid pDG1663, which carries an erythromycin resistance marker and a polylinker upstream of the lacZ gene between the two arms of the thrC gene to create pATB12, pATB13, and pATB14, respectively. These plasmids were transformed into DK1042.

To generate the PrepN, PalfA, PcomI, and PzpbK β-galactosidase reporter constructs, primer sets were used in the following order to amplify each promoter region: 5050/5051 (PrepN), 5048/5049 (PalfA), 5052/5053 (PcomI), and 5122/5123 (PzpbK). Each promoter region was digested with EcoRI and BamHI and subsequently cloned independently into the EcoRI and BamHI sites of plasmid pDG1663, which carries an erythromycin resistance marker and a polylinker upstream of the lacZ gene between the two arms of the thrC gene to create pDP477, pDP476, pDP478, and pDP480, respectively. These plasmids were transformed into DK1042.

(ii) lexA::mls.

The lexA::mls insertion deletion allele was generated using a modified “Gibson” isothermal assembly protocol (50). Briefly, the region upstream of lexA was PCR amplified using the primer pair 5661/5662 and the region downstream of lexA was PCR amplified using the primer pair 5663/5664. To amplify the erm resistance gene, pAH52 plasmid DNA was used in a PCR with the universal primers 3250/23251. Fragments were added in equimolar amounts to the Gibson ITA reaction mixture, and the reaction was performed as explained above. The mixture from the completed reaction was then PCR amplified using primers 5661/5664 to amplify the assembled product. The product was transformed into DK1042.

(iii) Isothermal assembly reaction buffer (5×).

A mixture containing 500 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM MgCl2, 50 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) (Bio-Rad), 31.25 mM polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000 (Fisher Scientific), 5.02 mM NAD (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 mM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) (New England BioLabs) was aliquoted and stored at −80°C. An assembly master mixture was made by combining prepared 5× isothermal assembly reaction buffer (131 mM Tris-HCl, 13.1 mM MgCl2, 13.1 mM DTT, 8.21 mM PEG 8000, 1.32 mM NAD, and 0.26 mM [each] dNTP) with Phusion DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs) (0.033 units/μl), T5 exonuclease diluted 1:5 with 5× reaction buffer (New England BioLabs) (0.01 units/μl), Taq DNA ligase (New England BioLabs) (5,328 units/μl), and additional dNTPs (267 μM). The master mix was aliquoted as 15 μl and stored at −80°C.

SPP1 phage transduction.

To an 0.2-ml dense culture grown in TY broth (LB supplemented with 10 mM MgSO4 and 100 μM MnSO4 after autoclaving), serial dilutions of SPP1 phage stock were added. This mixture was allowed to statically incubate at 37°C for 15 min. A 3-ml volume of TYSA (molten TY with 0.5% agar) was added to each mixture and poured on top of fresh TY plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C overnight. Plates on which plaques formed had the top agar harvested by scraping into a 50-ml conical tube. To release the phage, the tube was vortexed for 20 s and centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was passed through an 0.45-μm syringe filter and stored at 4°C.

Recipient cells were grown in 2 ml of TY broth at 37°C until stationary phase was reached. A 5-μl volume of SPP1 donor phage stock was added to 1 ml of cells, and 9 ml of TY broth was added to this mixture. The transduction mixture was allowed to stand statically at room temperature for 30 min. After incubation, the mixture was centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in the volume left. One hundred to 200 μl of the cell suspension was plated on TY fortified with 1.5% agar, 10 mM sodium citrate, and the appropriate antibiotic for selection.

Protein purification.

To create the SUMO-SigN fusion protein expression vector, the coding sequence of SigN was amplified from 3610 genomic DNA with primers that also introduced a SapI site at the 5′ end and a BamHI site at the 3′ end. This fragment was ligated into the SapI and BamHI sites of pTB146 to create pBM05.

To purify SigN, pBM05 was expressed in Rosetta Gami II cells and grown at 37°C until mid-log phase (∼0.5 OD600). IPTG was added to the cells to induce protein expression, and cells were allowed to grow overnight at 16°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed, and emulsified with EmulsiFlex-C3 (Avestin). Lysed cells were ultracentrifuged at 14,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C.The supernatant was mixed with Ni2+-NTA His·Bind resin (EMD Millipore) equilibrated with lysis/binding buffer (50 mM Na2HPO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM Imidazole, final pH 7.5) and allowed to incubate overnight at 4°C. The bead-lysate mixture was allowed to pack in a 1-cm separation column (Bio-Rad) and washed with wash buffer (50 mM Na2HPO4, 300 mM NaCl, 30 mM Imidazole, final pH 7.5). His-SUMO-SigN bound to the resin and was eluted using a stepwise elution of wash buffer with 50 to 500 mM imidazole and 10% glycerol to a final pH of 7.5. Eluates were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue to verify purification. Purified His-SUMO-SigN was combined with ubiquitin ligase (protease) and cleavage buffer and incubated at room temperature for 4 h to cleave the SUMO tag from the SigN protein (51). The cleavage reaction mixture was combined with Ni2+-NTA His·Bind resin, incubated for 1 h at 4°C, and centrifuged to pellet the resin. Supernatant was removed and dialyzed into lysis/binding buffer without the imidazole (50 mM Na2HPO4, 300 mM NaCl, 20% glycerol, final pH 7.5). Removal of the tag was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie brilliant blue.

To purify RNA polymerase, LB supplemented with kanamycin (5 μg/ml) was inoculated with an overnight culture of DK4203, which has the rpoC-hisX6 construct integrated into the native site of rpoC. The cells were grown at 37°C until they hit mid-log phase (∼0.5 OD600) and were harvested via centrifugation. The collected cells were washed with buffer I (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1 M KCl, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol) twice, resuspended in buffer G (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 20% [vol/vol] glycerol, 10 mM imidazole, 0.5 mg/ml lysozyme), and emulsified with EmulsiFlex-C3 (Avestin). The extracts were centrifuged for 30 min at 28,000 × g twice. The supernatant was mixed with Ni2+-NTA His·Bind resin (EMD Millipore) equilibrated with buffer G and allowed to go overnight at 4°C. The resin was collected by centrifugation and washed with buffer G. Buffer E (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 20% [vol/vol] glycerol, 500 mM imidazole) was used to elute the proteins associated with the resin and dialyzed in TGED buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA, 0.3 mM DTT, 20% [vol/vol] glycerol).

To create the SUMO-LexA fusion protein expression vector, the coding sequence of LexA was amplified from 3610 genomic DNA with primers that also introduced a SapI site at the 5′ end and a BamHI site at the 3′ end. This fragment was ligated into the SapI and BamHI sites of pTB146 to create pATB11.

For the purification of LexA, pATB11 was expressed in Rosetta Gami II cells and grown at 37°C until mid-log phase (∼0.5 OD600). Cells were treated the same as in the protein purification procedure for SigN (above).

SigN antibody purification.

One milligram of purified SigN protein was sent to Cocalico Biologicals for serial injection into a rabbit host for antibody generation. Anti-SigN serum was mixed with SigN-conjugated Affigel-10 beads and incubated overnight at 4°C. Beads were packed onto a 1-cm column (Bio-Rad), washed with 100 mM glycine (pH 2.5) to release the antibody, and neutralized immediately with 2 M Tris base. The antibody was verified using SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Purified anti-SigN antibody was dialyzed into 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 50% glycerol and stored at −20°C.

Western blotting.

B. subtilis strains were grown in LB and treated with mitomycin C (final concentration 0.3 μg/ml) as reported in the work of Myagmarjav et al. (17). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at the different time points after treatment. Cells were resuspended to an OD600 of 10 in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.0], 10 mM EDTA, 1 mg/ml lysozyme, 10 μg/ml DNase I, 100 μg/ml RNase I, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Twenty microliters of lysate was mixed with 4 μl 6× SDS loading dye. Samples were separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The proteins were electroblotted onto nitrocellulose and developed with a primary antibody used at a 1:5,000 dilution of anti-SigN, a 1:80,000 dilution of anti-SigA, and a 1:10,000 dilution secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G). The immunoblot was developed using the Immun-Star horseradish peroxidase (HRP) developer kit (Bio-Rad).

β-Galactosidase assay.

Biological replicates of B. subtilis strains were grown in LB and treated with mitomycin C to a final concentration of 0.3 μg/ml. Cells were allowed to grow, and 1 ml was harvested by centrifugation at the different time points indicated after treatment. When IPTG (final concentration, 1 mM) was used, cells grew to an OD600 of 0.6 and 1 ml was harvested. Cells were resuspended in 1 ml of Z buffer (40 mM NaH2PO4, 60 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM MgSO4, 10 mM KCl, and 38 mM β-mercaptoethanol) with 0.2 mg/ml of lysozyme and incubated at 30°C for 15 min. Each sample was diluted accordingly with Z buffer to 500 μl. The reaction was started with 100 μl of 4 mg/ml O-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (in Z buffer) and stopped with 1 M Na2CO3 (250 μl). The OD420 of each reaction mixture was noted, and the β-galactosidase specific activity was calculated using the equation [OD420/(time × OD600)] × dilution factor × 1,000.

Collection of cells for Rend-seq.

Overnight cultures were back diluted 1:100 in LB and grown at 37°C with shaking. When the cultures reached an OD600 of 0.1, they were treated with either 1 μg/ml MMC (DK297 and DK3287) or 1 mM IPTG (DK1634). The zpdN overexpression strain was harvested 1 h after induction by IPTG. Cells treated with MMC were collected after 2 h. After treatment, 10 ml of each culture was mixed with 10 ml of ice-cold methanol and spun down at 3,220 × g at 4°C for 10 min. Supernatant was discarded, and cell pellets were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. For RNA extraction, the thawed pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) and added to FastPrep Lysis Matrix B 2-ml tubes with beads (MP Biomedicals). Cells were disrupted in a Bead Ruptor 24 (Omni International, Kennesaw, GA) twice for 40 s at 6.0 M/s. Two hundred microliters of chloroform was and were kept at room temperature for 2 min after vigorous vortexing. The mixture was spun down at 18,200 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The aqueous phase (∼600 μl) was precipitated with 900 μl of isopropanol for 10 min at room temperature. The RNA pellet was collected and washed with 80% ethanol.

Rend-seq library preparation.

RNA was prepared for Rend-seq as described in detail in the work of Lalanne et al. (27) and DeLoughery et al. (28). In brief, 5 to 10 μg RNA was DNase treated (Qiagen) and rRNA was depleted (MICROBExpress; Thermo Fisher). rRNA-depleted RNA was fragmented by first heating the sample to 95°C for 2 min and adding RNA fragmentation buffer (1×; Thermo Fisher) for 30 s at 95°C and quenched by addition of RNA fragmentation stop buffer (Thermo Fisher). RNA fragments between 20 and 40 bp were isolated by size excision from a denaturing polyacrylamide gel (15%, Tris-borate-EDTA [TBE]–urea, 65 min, 200 V; Thermo Fisher). RNA fragments were dephosphorylated using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA), precipitated, and ligated to 5′-adenylated and 3′-end-blocked linker 1 (IDT; 5 μM) using T4 RNA ligase 2, truncated K227Q. The ligation was carried out at 25°C for 2.5 h using <5 pmol of dephosphorylated RNA in the presence of 25% PEG 8000 (Thermo Fisher). cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription of ligated RNA using Superscript III (Thermo Fisher) at 50°C for 30 min. with primer oCJ485 (IDT, Coralville, IA), and the RNA was hydrolyzed. cDNA was isolated by PAGE size excision (10% TBE-urea, 200 V, 80 min; Thermo Fisher). Single-stranded cDNAs were circularized using CircLigase (Illumina, San Diego, CA) at 60°C for 2 h. Circularized cDNA was the template for PCR amplification using Phusion DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs) with Illumina sequencing primers, primer o231 (IDT), and barcoded indexing primers (IDT). After 6 to 10 rounds of PCR amplification, the product was selected by size from a nondenaturing PAGE gel (8% TB (tris-borate), 45 min, 180 V; Life Technologies). For data set names and barcode information, see Table S3 in the supplemental material.

RNA sequencing and data analysis.

Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencer. The 3′ linker sequences were stripped. Bowtie v. 1.2.1.1 (options -v 1 -k 1) was used for sequence alignment to the reference genome NC 000964.3 (B. subtilis chromosome) and KF365913.1 (B. subtilis plasmid pBS32) obtained from the NCBI Reference Sequence Bank. To deal with nontemplate addition during reverse transcription, reads with a mismatch at their 5′ end had their 5′ end reassigned to the immediate next downstream position. The 5′ and 3′ ends of mapped reads between 15 and 45 nucleotides (nt) in size were counted separately at genomic positions to produce wig files. The wig files were normalized per million non-rRNA and non-tRNA reads for each sample. Shadows were removed from wig files first by identifying the position of peaks and then by reducing the other end of the aligned reads by the peak’s enrichment factor to produce the final normalized and shadow-removed wig files. Gene regions were plotted in Matlab.

Electromobility shift assays.

To perform electromobility shift assays, LexA was purified from Escherichia coli as outlined above. The control promoter, PrecA, was amplified using the primer set 6252/6253, PsigNUP was amplified using the primer set 6089/6090, PsigNDN was amplified using the primer set 6087/6088, and PsigNUP* (LexA site scrambled) was amplified using the primer sets 6089/6284 and 6090/6283 from B. subtilis 3610 genomic DNA. The PsigNUP* fragments were ligated using Gibson ITA as outlined above. All fragments were cleaned up using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Each DNA probe was end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP with T4 polynucleotide kinase (PNK) (New England BioLabs). Excess nucleotide was removed using G-50 microcolumns (GE Life Technologies). DNA binding reaction mixtures contained 4 nM DNA probe and a specific concentration of purified LexA protein (either 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, or 500 nM). Reactions were carried out in binding buffer (100 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM Tris-HCl, 50% glycerol, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT) supplemented with 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 10 ng/μl poly(dI-dC). All reaction mixtures were incubated for 45 min at room temperature. Protein-DNA complexes were resolved on a 6% TGE (tris-glycine EDTA) polyacrylamide gel. Gels were dried at 80°C for 90 min and exposed to a storage phosphor screen overnight. Gels were imaged with a Typhoon 9500 imager (GE Life Sciences).

In vitro transcription.

DNA template (50 ng) was mixed with either RNAP only (250 nM) or RNAP plus SigN (1,000 nM) per reaction. Each reaction mixture was incubated for 15 min at 37°C in a 25-μl total reaction volume including the transcription buffer (18 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM MgCl2, 30 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 250 μM GTP, 100 μM ATP, 100 μM CTP, 5 μM UTP, and ∼2 μCi [α-32P]UTP) to produce multiple-round transcription. To stop the reaction, 25 μl of 2× Stop/Gel loading solution (7 M urea, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 2× TBE, 0.05% bromophenol blue) was used. Samples were run on a 5% denaturing acrylamide gel (5% acrylamide [19:1 acryl:bis], 7 M urea, 1× TBE) for 3 h at 200 V. Gels were imaged with a Typhoon 9500 imager (GE Life Sciences).

Phylogenetic tree creation.

Sigma homologs to SigA, SigH, and SigM were identified in the genomes of 24 model organisms (listed in Table S6) using BLAST+ version 2.2.31 and an E value threshold of 1E−2 (52) and compared to all SigN homologs found in the database. The sequences were aligned using the default parameters of Muscle v3.8.31. The resulting alignment was used to generate a phylogenetic tree with RAxML version 8.1.3 set to perform 100 rapid bootstraps and subsequent maximum likelihood search using the GAMMA model of rate heterogeneity and the JTT substitution model (53). The data are presented using the Interactive Tree of Life visualization software (54).

Data and software availability.

Ribosome profiling and RNA sequencing are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE134424. Data were analyzed using custom Matlab scripts which are available upon request.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alyssa Ball, Ryan Chaparian, Felix Dempwolff, Masaya Fujita, Kate Hummels, Bat-Erdene Magyarjav, Reid Oshiro, Sundharraman Subramanian, Lauren Wahle, and Julia van Kessel for technical support.

This work was supported by NIH R35GM124732 to G.-W.L. and NIH grant R35GM131783 to D.B.K.

Footnotes

Citation Burton AT, DeLoughery A, Li G-W, Kearns DB. 2019. Transcriptional regulation and mechanism of SigN (ZpdN), a pBS32-encoded sigma factor in Bacillus subtilis. mBio 10:e01899-19. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01899-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stanley NR, Lazazzera BA. 2005. Defining the genetic differences between wild and domestic strains of Bacillus subtilis that affect poly-γ-dl-glutamic acid production and biofilm formation. Mol Microbiol 57:1143–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLoon AL, Guttenplan SB, Kearns DB, Kolter R, Losick R. 2011. Tracing the domestication of a biofilm forming bacterium. J Bacteriol 193:2027–2034. doi: 10.1128/JB.01542-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kearns DB, Chu F, Rudner R, Losick R. 2004. Genes governing swarming in Bacillus subtilis and evidence for a phase variation mechanism controlling surface motility. Mol Microbiol 52:357–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.03996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeigler DR, Prágai Z, Rodriguez S, Chevreux B, Muffler A, Albert T, Bai R, Wyss M, Perkins JB. 2008. The origins of 168, W23, and other Bacillus subtilis legacy strains. J Bacteriol 190:6983–6995. doi: 10.1128/JB.00722-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakano MM, Marahiel MA, Zuber P. 1988. Identification of a genetic locus required for biosynthesis of the lipopeptide antibiotic surfactin in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 170:5662–5668. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5662-5668.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Earl AM, Losick R, Kolter R. 2007. Bacillus subtilis genome diversity. J Bacteriol 189:1163–1170. doi: 10.1128/JB.01343-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konkol MA, Blair KM, Kearns DB. 2013. Plasmid-encoded ComI inhibits competence in the ancestral 3610 strain of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 195:4085–4093. doi: 10.1128/JB.00696-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka T, Ishida H, Maehara T. 2005. Characterization of the replication region of plasmid pLS32 from the natto strain of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 187:4315–4326. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.13.4315-4326.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka T, Ogura M. 1998. A novel Bacillus natto plasmid pLS32 capable of replication in Bacillus subtilis. FEBS Lett 422:243–246. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker E, Herrera NC, Gunderson FQ, Derman AI, Dance AL, Sims J, Larsen RA, Pogliano J. 2006. DNA segregation by the bacterial actin AlfA during Bacillus subtilis growth and development. EMBO J 25:5919–5931. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parashar V, Konkol MA, Kearns DB, Neiditch MB. 2013. A plasmid-encoded phosphatase regulates Bacillus subtilis biofilm architecture, sporulation, and genetic competence. J Bacteriol 195:2437–2448. doi: 10.1128/JB.02030-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bendori SO, Pollak S, Hizi D, Eldar A. 2015. The RapP-PhrP quorum-sensing system of Bacillus subtilis strain NCIB3610 affects biofilm formation through multiple targets, due to an atypical signal-insensitive allele of RapP. J Bacteriol 197:592–602. doi: 10.1128/JB.02382-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyons NA, Kolter R. 2018. A single mutation in rapP induces cheating to prevent cheating in Bacillus subtilis by minimizing public good production. Commun Biol 1:133. doi: 10.1038/s42003-018-0136-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okamoto K, Mudd JA, Marmur J. 1968. Conversion of Bacillus subtilis DNA to phage DNA following mitomycin C induction. J Mol Biol 34:429–437. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mauël C, Karamata D. 1984. Characterization of proteins induced by mitomycin C treatment of Bacillus subtilis. J Virol 49:806–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goranov AI, Kuester-Schoeck E, Wang JD, Grossman AD. 2006. Characterization of the global transcriptional responses to different types of DNA damage and disruption of replication in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 188:5595–5605. doi: 10.1128/JB.00342-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myagmarjav B-E, Konkol MA, Ramsey J, Mukhopadhyay S, Kearns DB. 2016. ZpdN, a plasmid-encoded sigma factor homolog, induces pBS32-dependent cell death in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 198:2975–2984. doi: 10.1128/JB.00213-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood HE, Dawson MT, Devine KM, McConnell DJ. 1990. Characterization of PBSX, a defective prophage of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 172:2667–2674. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2667-2674.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warner FD, Kitos GA, Romano MP, Hemphill HE. 1977. Characterization of SPβ: a temperate bacteriophage from Bacillus subtilis 168M. Can J Microbiol 23:45–51. doi: 10.1139/m77-006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lazarevic V, Düsterhöft A, Soldo B, Hilbert H, Mauël C, Karamata D. 1999. Nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus subtilis temperate bacteriophage SPβc2. Microbiology 145:1055–1067. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-5-1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seaman E, Tarmy E, Marmur J. 1964. Inducible phages of Bacillus subtilis. Biochemistry 3:607. doi: 10.1021/bi00893a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winterling KW, Levine AS, Yasbin RE, Woodgate R. 1997. Characterization of DinR, the Bacillus subtilis SOS repressor. J Bacteriol 179:1698–1703. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1698-1703.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groban ES, Johnson MB, Banky P, Burnett P-GG, Calderon GL, Dwyer EC, Fuller SN, Gebre B, King LM, Sheren IN, Von Mutius LD, O’Gara TM, Lovett CM. 2005. Binding of the Bacillus subtilis LexA protein to the SOS operator. Nucleic Acids Res 33:6287–6295. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raymond-Denise A, Guillen N. 1991. Identification of dinR, a DNA damage-inducible regulator gene of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 173:7084–7091. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7084-7091.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winterling KW, Chafin D, Hayes JJ, Sun J, Levine AS, Yasbin RE, Woodgate R. 1998. The Bacillus subtilis DinR binding site: redefinition of the consensus sequence. J Bacteriol 180:2201–2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller MC, Resnick JB, Smith BT, Lovett CM. 1996. The Bacillus subtilis dinR gene codes for the analogue of Escherichia coli LexA. J Biol Chem 271:33502–33508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lalanne J-B, Taggart JC, Guo MS, Herzel L, Schieler A, Li G-W. 2018. Evolutionary convergence of pathway-specific enzyme expression stoichiometry. Cell 173:749–761.e38. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DeLoughery A, Lalanne J-B, Losick R, Li G-W. 2018. Maturation of polycistronic mRNAs by the endoribonuclease RNase Y and its associated Y-complex in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:e5585–5594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1803283115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staroń A, Sofia HJ, Dietrich S, Ulrich LE, Liesegang H, Mascher T. 2009. The third pillar of bacterial signal transduction: classification of the extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factor protein family. Mol Microbiol 74:557–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujita M. 2000. Temporal and selective association of multiple sigma factors with RNA polymerase during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Cells 5:79–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujita M, Sadaie Y. 1998. Rapid isolation of RNA polymerase from sporulating cells of Bacillus subtilis. Gene 221:185–190. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujita M, Sadaie Y. 1998. Promoter selectivity of the Bacillus subtilis RNA polymerase sigmaA and sigmaH holoenzymes. J Biochem 124:89–97. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, Ren J, Li WW, Noble WS. 2009. MEME suite: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res 37:W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brooks L, Kaze M, Sistrom M. 2019. A curated, comprehensive database of plasmid sequences. Microbiol Resour Announc 8:e01325-18. doi: 10.1128/MRA.01325-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDonnell GE, Wood H, Devine KM, McConnell DJ. 1994. Genetic control of bacterial suicide: regulation of the induction of PBSX in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 176:5820–5830. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5820-5830.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pero J, Tjian R, Nelson J, Losick R. 1975. In vitro transcription of a late class of phage SP01 genes. Nature 257:248–251. doi: 10.1038/257248a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fox TD, Losick R, Pero J. 1976. Regulatory gene 28 of bacteriophage SPO1 codes for a phage-induced subunit of RNA polymerase. J Mol Biol 101:427–433. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Talkington C, Pero J. 1979. Distinctive nucleotide sequences of promoters recognized by RNA polymerase containing a phage-coded “sigma-like” protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76:5465–5469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.11.5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ikeda H, Tomizawa J. 1968. Prophage P1, an extrachromosomal replication unit. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol 33:791–798. doi: 10.1101/SQB.1968.033.01.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McVeigh RR, Yasbin RE. 1996. Phenotypic differentiation of “smart” versus “naive” bacteriophages of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 178:3399–3401. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3399-3401.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Little JW. 1984. Autodigestion of lexA and phage lambda repressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81:1375–1379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Little JW, Edmiston SH, Pacelli LZ, Mount DW. 1980. Cleavage of the Escherichia coli lexA protein by the recA protease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77:3225–3229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Butala M, Žgur-Bertok D, Busby S. 2009. The bacterial LexA transcriptional repressor. Cell Mol Life Sci 66:82–93. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8378-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanaka T. 2010. Functional analysis of the stability determinant AlfB of pBET131, a miniplasmid derivative of Bacillus subtilis (natto) plasmid pLS32. J Bacteriol 192:1221–1230. doi: 10.1128/JB.01312-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polka JK, Kollman JM, Mullins RD. 2014. Accessory factors promote AlfA-dependent plasmid segregation by regulating filament nucleation, disassembly, and bundling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:2176–2181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304127111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duerkop CA, Huo BA, Bhardwaj W, Palmer PL, Hooper KL. 2016. Molecular basis for lytic bacteriophage resistance in enterococci. mBio 7:1304-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01304-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Helmann JD. 2002. The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Adv Microb Physiol 46:47–110. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(02)46002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feklístov A, Sharon BD, Darst SA, Gross CA. 2014. Bacterial sigma factors: a historical, structural, and genomic perspective. Annu Rev Microbiol 68:357–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yasbin RE, Young FE. 1974. Transduction in Bacillus subtilis by bacteriophage SPP1. J Virol 14:1343–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang R-Y, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, Smith HO. 2009. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods 6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Butt TR, Edavettal SC, Hall JP, Mattern MR. 2005. SUMO fusion technology for difficult-to-express proteins. Protein Expr Purif 43:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Letunic I, Bork P. 2016. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res 44:W242–W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Rend-seq analysis of the sigN promoter region. The same data as in Fig. 2C re-presented after normalization per million reads that mapped to the plasmid. Download FIG S2, PDF file, 0.9 MB (932KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Rend-seq data table. List of primers used in the Rend-seq assay. Download Table S3, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (12.9KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

β-Galactosidase activity in Miller units. Each table (A to F) lists the numerical values of each β-galactosidase assay performed in Miller units and identifies the corresponding figure. Download Table S5, DOCX file, 0.02 MB (16.8KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Rend-seq data of chromosomal genes. List of upregulated genes and corresponding fold change that was observed during SigN overexpression in the presence of pBS32. Download Table S4, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (13.6KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Genomes used for sigma 70 homolog sequence analysis. List of genomes used to obtain sigma 70 homologs for sequence analysis in Fig. 6B. Download Table S6, XLSX file, 0.01 MB (13.9KB, xlsx) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

SigN does not activate the replication initiator, partitioning system, competence inhibitor, or prophage structural genes. β-Galactosidase activity of strains containing either PsigN-lacZ, PrepN-lacZ (promoter of the replication initiator protein RepN), PalfA-lacZ (promoter of the partitioning system AlfAB), PcomI-lacZ (promoter of the competence inhibitor ComI), or PzpbK-lacZ (promoter of the long prophage structural gene operon) in the absence (open bars) or presence (closed bars) of IPTG. Reporter expression was measured in cells containing (left panel) or lacking (right panel) pBS32. The following strains were used to generate this panel: DK4401 (PsigN-lacZ ΔpBS32), DK4670 (PrepN-lacZ ΔpBS32), DK4669 (PalfA-lacZ ΔpBS32), DK4671 (PcomI-lacZ ΔpBS32), DK4673 (PzpbK-lacZ ΔpBS32), DK4943 (PsigNI-lacZ), DK4949 (PrepN-lacZ), DK4948 (PalfA-lacZ), DK4725 (PcomI-lacZ), and DK4994 (PzpbK-lacZ). Error bars are the standard deviation from three replicates. Data used to generate each panel are included in Table S5F. Download FIG S1, PDF file, 0.05 MB (49.5KB, pdf) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Plasmids. List of plasmids used in this study. Download Table S1, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (12.8KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Primers. List of primers used in this study. Download Table S2, DOCX file, 0.01 MB (14.1KB, docx) .

Copyright © 2019 Burton et al.

This content is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.