Abstract

Background

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) yield is seriously influenced by panicle exsertion (PE) and the uppermost internode (UI) through panicle enclosure or energy transport during grain-filling stages. We evaluated the traits of PE and UI of 205 rice accessions in two independent environments and performed genome-wide association (GWAS) to explore the key genes controlling PE and UI, which could be used to improve panicle enclosure in rice breeding.

Results

In this study, extensive genetic variation was found in both PE and UI among the 205 rice accessions, and 10.7% of accessions had panicle enclosure (PE/UI ≤ 0). Correlation analysis revealed that PE was significantly positively correlated with 1000-grain weight (1000-GW) but negatively correlated with heading date (HD), and UI was significantly positively correlated with HD but no significantly correlated with 1000-GW. A total of 22 and 24 quantitative trait loci (QTLs) were identified for PE and UI using GWAS, respectively. Eight loci for PE and nine loci for UI were simultaneously detected both in 2015 and in 2016, seven loci had adjacent physical positions between PE and UI, and ten loci for PE and seven loci for UI were located in previously reported QTLs. Further, we identified the CYP734A4 gene, encoding a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, and the OsLIS-L1 gene, encoding a lissencephaly type-1-like protein, as causal genes for qPE14 and qUI14, and for qPE19, respectively. PE and UI were both significantly shorter in these two genes’ mutants than in WT. Allelic Hap.1/2/4 of CYP734A4 and Hap.1/2/4 of OsLIS-L1 increased PE, UI, PE/UI, and 1000-GW, but Hap.3 of CYP734A4 and Hap.3 of OsLIS-L1 reduced them. In addition, six candidate genes were also detected for four key novel loci, qPE16, qPE21, qUI1, and qUI18, that seemed to be related to PE and UI.

Conclusions

Our results provide new information on the genetic architecture of PE and UI in rice, confirming that the CYP734A4 and OsLIS-L1 genes participate in PE and UI regulation, which could improve our understanding of the regulatory mechanism of PE and UI for rice breeding in the future.

Keywords: Oryza sativa L., Genome-wide association study, Panicle exsertion (PE), Uppermost internode (UI), Panicle enclosure

Background

Rice is a staple food for nearly half of the world’s population. Rice yield is seriously reduced when panicle enclosure occurs in cultivated varieties, particularly in hybrid rice varieties (Guan et al. 2011; Duan et al. 2012). It is well known that panicle exsertion (PE) and the uppermost internode (UI) play a critical role in the regulation of panicle enclosure (da Cruz et al. 2008; Qiao et al. 2008; Duan et al. 2012). Panicle enclosure means that panicles are partly or fully enclosed within the flag leaf sheath, mainly caused by the shortening of UI (Yin et al. 2007; Guan et al. 2011). Simultaneously, both PE and UI are connected to the culm and panicle, controlling the transport efficiency of water and nutrients from the leaves and stems to grains and ultimately affecting grain filling and crop yield (Ma et al. 2002; da Cruz et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2008). Therefore, exploring the key genes related to PE and UI in rice is helpful for breeding high-yield rice varieties without panicle enclosure by the marker-assisted selection (MAS) approach.

PE and UI have been reported to be quantitative traits controlled by multiple genes, and some quantitative trait loci (QTLs) have been identified by the traditional mapping approach in rice (Qiao et al. 2008; Zhao et al. 2016; Herlina et al. 2016). Qiao et al. (2008) identified three QTLs for UI on chromosomes 1, 3 and 6 and four QTLs for panicle enclosure on chromosomes 1, 3, 5, and 10, respectively. Zhao et al. (2016) detected five QTLs, qPE1, qPE3, qPE6, qPE9, and qPE11, for PE. One QTL for incomplete panicle exertion was identified on chromosome 4 using a BC2F8 line derived from a cross between IR64 and Gajah Mungkur (Herlina et al. 2016). Recently, a qPE12 locus controlling rice panicle exsertion was fine-mapped using C115, a chromosome segment substitution line carrying introgression segments of Nipponbare on the genetic background of indica variety 9311 (Zhao et al. 2018).

So far, at least 6 mutants of PE and UI have been reported in rice, and their corresponding genes were mapped or cloned, such as ESP2 (Guan et al. 2011) and sui1/OsPSS-1 for UI on chromosome 1 (Zhu et al. 2011), HOX12 for PE and UI on chromosome 3 (Gao et al. 2016), EUI1 for UI on chromosome 5 (Lou et al. 2006), SUI4 for UI on chromosome 7 (Ji et al. 2014), and ESP1 for UI on chromosome 11 (Duan et al. 2012). Of these genes, the shortened uppermost internode 1 (SUI1) gene was belonged to the SUI family, which encodes base-exchange types of phosphatidyl serine synthases (PSS) (Yin et al. 2013). And, the SUI1 gene was found to negatively regulate rice UI by secreting cell wall components (Zhu et al. 2011; Ma et al. 2016). EUI1 was obtained by map-based cloning and corresponded to a P450 gene, CYP714D1, encoding a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, and elongated UI by causing accumulation of gibberellin (GA) (Ma et al. 2006; Lou et al. 2006; Zhu et al. 2006). Gao et al. (2016) found that the homeodomain-leucine zipper transcription factor HOX12 acted directly through EUI1 to regulate PE. In addition, the OsLIS-L1 gene (lissencephaly type-1-like 1) encodes the lissencephaly type-1-like protein containing the WD40 motif, which was reported to play an important role in rice UI (Gao et al. 2012).

With the rapid development of high-throughput sequencing technology, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are becoming an effective approach to identify genes underlying complex traits in rice. Huang et al. (2010) performed a GWAS to analyse 14 agronomic traits, including grain width, grain weight and heading date, via 517 sequenced rice landraces. Famoso et al. (2011) identified aluminium tolerance by a GWAS based on 383 rice accessions. Jia et al. (2012) reported that ten loci on seven chromosomes were significantly associated with the response to the sheath blight pathogen using 217 rice accessions. Many panels of high-density single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data have been built to explore new genes related to target traits by GWAS (Han and Huang, 2013; Li et al. 2014). Through 413 different accessions of O. sativa collected from 82 countries, high-resolution genotyping panels including 44,100 and 700,000 SNP variants were built for GWAS by Zhao et al. (2011) and McCouch et al. (2016), respectively. The 3000 Rice Genomes Project was carried out based on the sequencing of 3000 rice accessions that afforded a global representation of genetic and functional diversity (Li et al. 2014). Furthermore, the estimated effect of nucleotide polymorphisms was created to rapidly identify candidate genes with traits from GWAS (Yano et al. 2016). There are no reports about genes associated with PE and UI that have been identified via GWAS in rice.

In this study, PE and UI traits on a targeted population of 205 rice accessions (114 INDICA accessions, 57 JAPONICA accessions, and 34 ADMIX accessions) from rice diversity pane l (RDP1) (Zhao et al. 2011) were investigated to detect the associated loci via GWAS using a high-resolution, open-access research platform that included 700 K SNP data (McCouch et al. 2016). Heading date (HD) and 1000-grain weight (1000-GW) were also analysed to examine the relationships among PE, UI, HD and 1000-GW. The functional SNPs with each main peak-associated locus were estimated to refine the target candidate genes for further research. Our studies indicated that CYP734A4 and OsLIS-L1 genes could participate in PE and UI regulation, and six genes within four key novel loci seemed to be related to PE and UI.

Results

Phenotypic variance

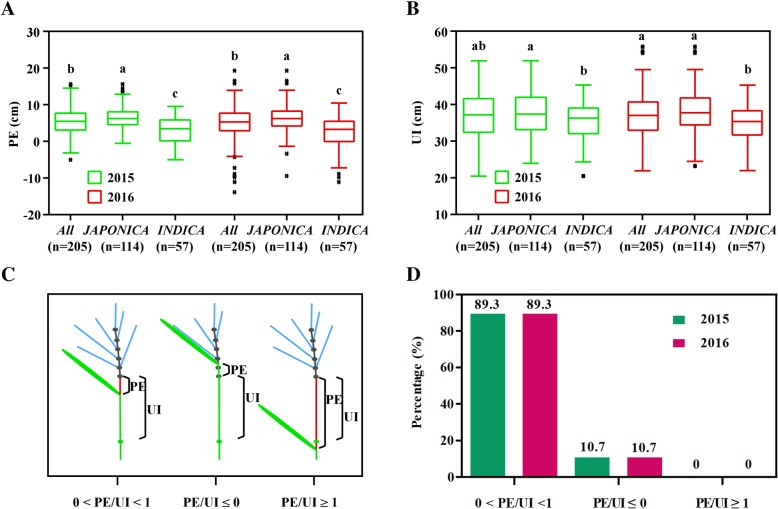

The PE and UI traits of 205 rice accessions from RDP1 (Zhao et al. 2011) were evaluated in 2015 and 2016 in the fields at Nanjing, China (Fig. 1a, b; Additional file 5: Table S2). Phenotype analysis showed that 89.3% of accessions had their flag leaves overlapping a part of PE (0 < PE/UI < 1), 10.7% had panicle enclosure (PE/UI ≤ 0), and none had its flag leaf under the node of UI (PE/UI ≥ 1) (Fig. 1c, d). The results revealed that this population had a large phenotypic variation in PE and UI traits, ranging from − 13.92 to 19.24 cm and 20.53 to 56.01 cm, respectively (Additional file 5: Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Phenotypic distribution in the RDP1 in 2015 and 2016. a, b Box plot of the phenotypic variation of PE and UI within the All, JAPONICA and INDICA groups. The horizontal lines represent the median values, box edges represent upper and lower quantiles, and whiskers are 1.5 times the quantile of the data. Outliers are shown as open dots. n represents the number of genotypes, and small letters above error bars indicate significant differences between subpopulations (LSD, P < 0.05). c Three pattern diagrams between PE and UI. 0 < PE/UI < 1 represents flag leaf overlapping a part of PE, PE/UI ≤ 0 represents flag leaf enclosing the panicle partly or fully, and PE/UI ≤ 0 represents flag leaf under the node of UI. d Analysis of frequency distribution for the three models between PE and UI

The coefficient of variation (CV) for PE ranged from 51.30 to 116.78% and 60.31 to 211.40%, with mean values of 3.00 to 6.34 cm and 2.30 to 6.38 cm in 2015 and 2016, respectively. The broad-sense heritability of PE was estimated to be 33.89 to 80.93%. The CV for UI ranged from 15.48 to 17.04% and 15.09 to 16.31%, with mean values of 35.31 to 37.75 cm and 34.83 to 37.95 cm in 2015 and 2016, respectively. The broad-sense heritability of UI was estimated to be 47.32 to 96.19% (Additional file 5: Table S1). 1000-GW and HD were also evaluated, and their broad-sense heritability was estimated as 81.32 to 85.14% and 79.82 to 84.90%, respectively (Additional file 5: Table S1). By comparison, the mean values of PE and UI in the INDICA group were both significantly lower than those in the JAPONICA group (Fig. 1a, b). These results indicated that the population had extensive genetic variation in PE and UI traits.

Correlation analysis

The correlation analysis was performed for twelve pairwise combinations derived from PE, UI, HD, and 1000-GW traits (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The results showed that there were similar correlations between them in 2015 and 2016. An extremely significantly positive correlation was found between PE and UI. Meanwhile, the correlation analysis showed that PE had a significantly positive correlation with 1000-GW and a significantly negative correlation with HD. UI had a significantly positive correlation with HD but no significant correlation with GW. In addition, there was a significantly negative correlation between 1000-GW and HD.

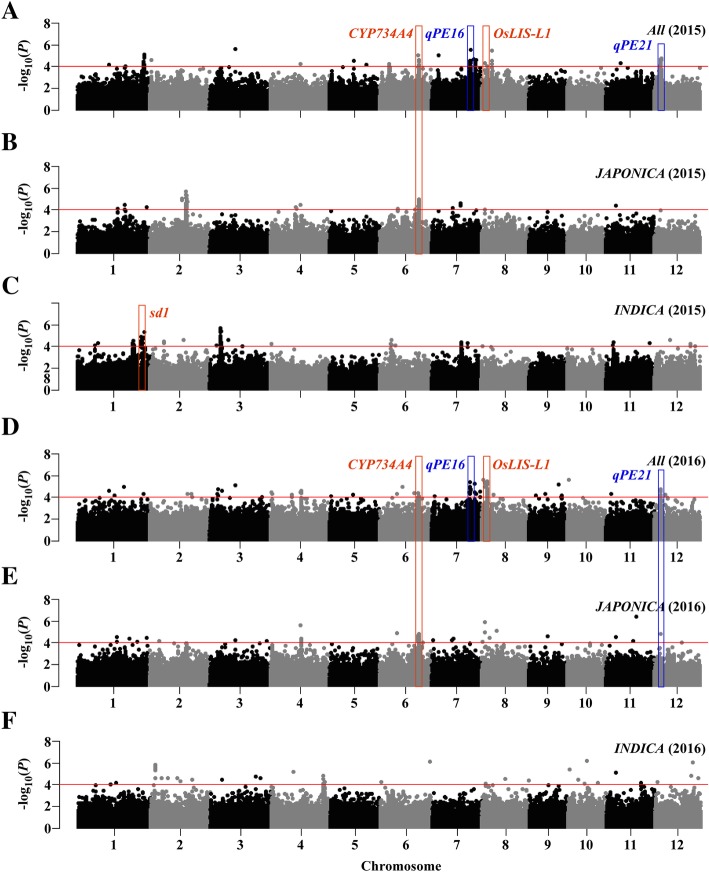

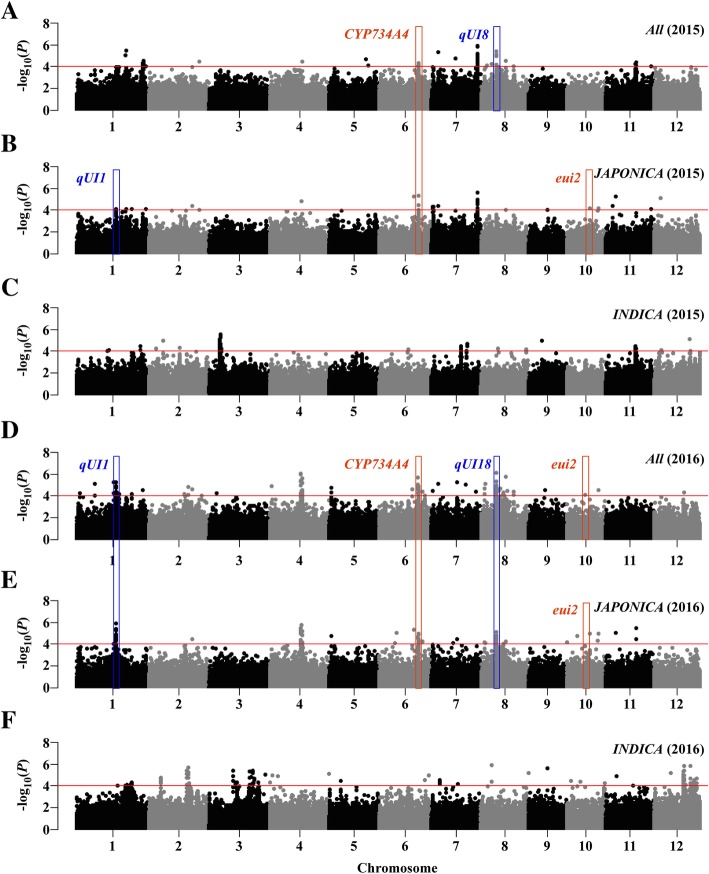

GWAS of PE and UI

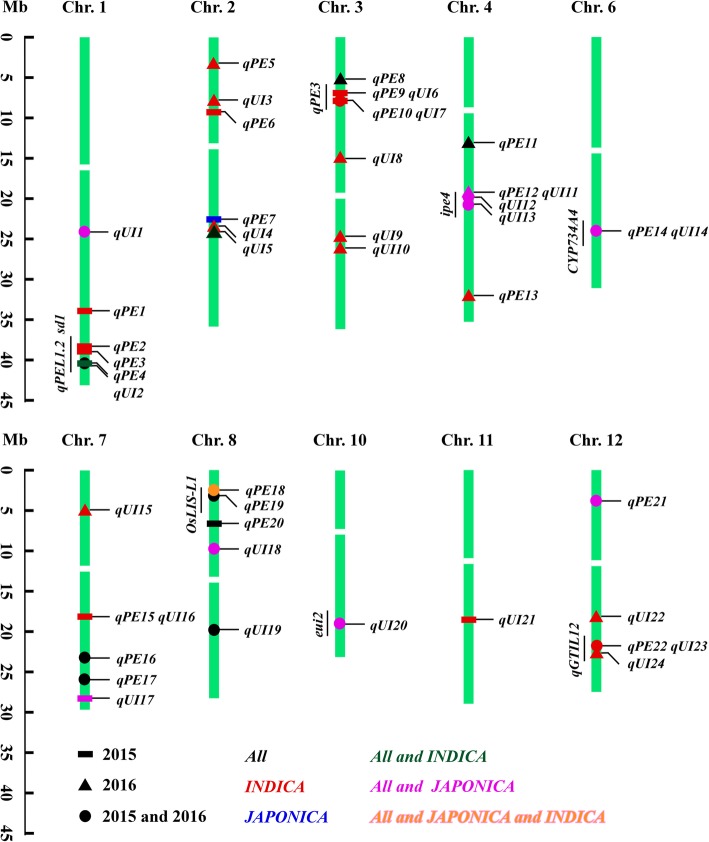

We carried out GWAS on the whole population as well on individual subpopulations based on large variation within the JAPONICA and INDICA subpopulations (Fig. 1a, b). The analysis showed that 22 loci within 261 SNPs on eight rice chromosomes were significantly associated with PE, and 24 loci within 278 SNPs on 10 chromosomes were significantly associated with UI (Figs. 2 and 3; Additional file 5: Table S3). Among those loci, eight PE-related and nine UI-related loci were co-located in both 2015 and 2016, and seven pairs of loci had adjacent physical positions between PE and UI (Figs. 2, 3 and 4; Additional file 5: Table S3). In our analysis of subpopulations, five loci for PE and eight loci for UI were detected in JAPONICA, and 12 loci for PE and 14 loci for UI were found in INDICA. Among them, five loci for PE and 11 loci for UI were found in both All and sub-populations (Figs. 2, 3 and 4; Additional file 5: Table S3).

Fig. 2.

Genome-wide Manhattan plots of association mapping for PE using the EMMAX model. Associations identified based on All (2015, a; 2016, d), JAPONICA (2015, b; 2016, e) and INDICA (2015, c; 2016, f) groups are depicted in separate panels. The red bar frames indicate the genes reported previously, and the blue bar frames indicate the key novel loci co-located in both 2015 and 2016. The x axis depicts the physical location of SNPs across the 12 chromosomes of rice, and the y axis depicts -log10(P value). Significant SNPs with P ≤ 0.0001 are denoted as red lines

Fig. 3.

Genome-wide Manhattan plots of association mapping for UI using the EMMAX model. Associations identified based on All (2015, a; 2016, d), JAPONICA (2015, b; 2016, e) and INDICA (2015, c; 2016, f) groups are depicted in separate panels. The red bar frames indicate that genes are reported, and the blue bar frames indicate the key novel loci co-located in both 2015 and 2016. The x axis depicts the physical location of SNPs across 12 chromosomes of rice, and the y axis depicts -log10(P value). Significant SNPs with P ≤ 0.0001 are denoted as red lines

Fig. 4.

Chromosomal positions of loci for PE and UI identified via GWAS in All, JAPONICA, and INDICA groups in 2015 and 2016. The mapped loci in this study are shown on the right, and previously mapped QTLs are shown on the left

By comparison, ten loci for PE and seven loci for UI were simultaneously identified with the reported mapped loci or characterized genes (Fig. 4; Additional file 5: Table S3). The remaining 12 loci for PE and 17 for UI might be novel. Of these novel loci, qPE16, qPE21, qUI1 and qUI18, were co-located in both 2015 and 2016 with significantly leading SNP (P < 1.0e-8) (Figs. 2 and 3), and were considered to be further analyzed for causal genes in our study.

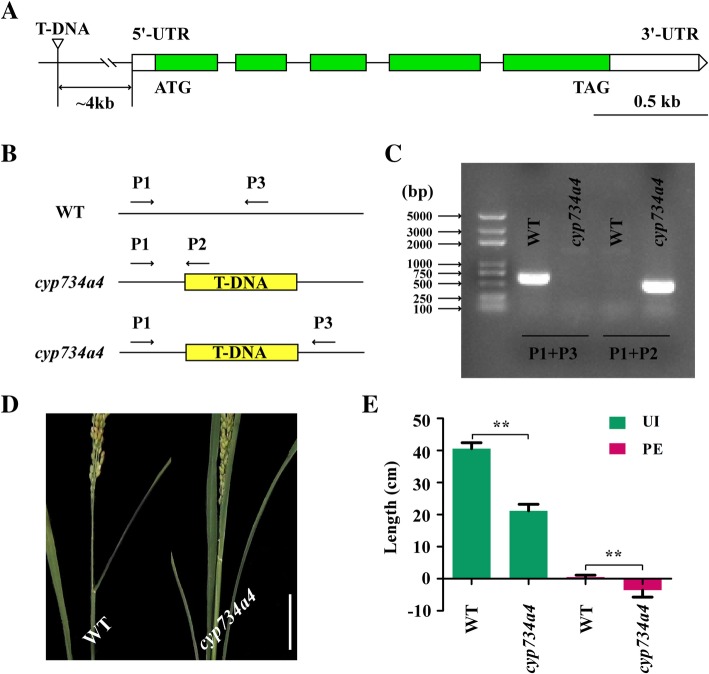

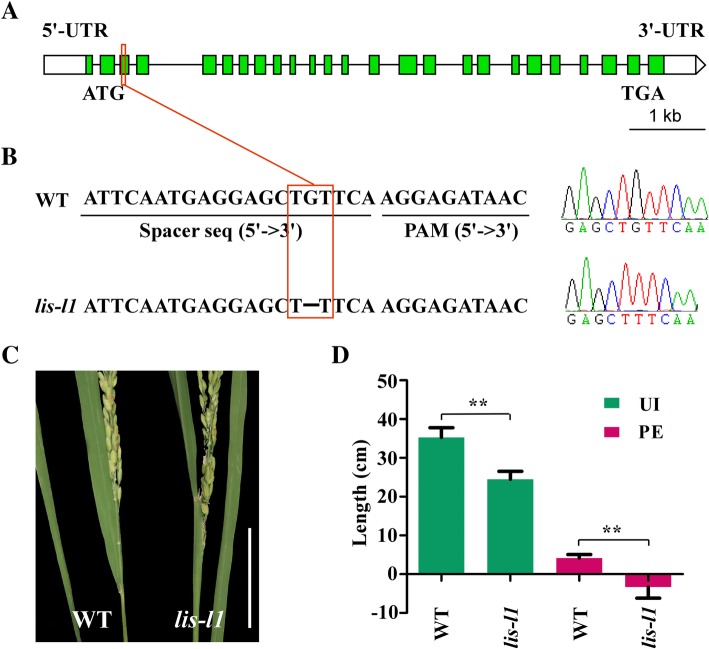

Effect of CYP734A4 and OsLIS-L1 on PE and UI

According to previous reports, all internodes of cyp734a4 mutants are significantly shortened by degrading brassinosteroids (BRs) (Qian et al. 2017), and the OsLIS-L1 gene can regulate cell proliferation in the first internodes under the panicle (Gao et al. 2012). In our study, we found that the CYP734A4 gene was located within qPE14 and qUI14, and OsLIS-L1 was located within qPE19 (Figs. 2, 3 and 4). Therefore, we obtained homozygous mutants of cyp734a4 containing a T-DNA insertion in the promoter region of the CYP734A4 gene in Zhonghua11 (Fig. 5a-c) and structured the oslis-l1 mutants by using the CRISPR/Cas9 system from the Nipponbare variety in this study (Fig. 6a, b). The results showed that PE and UI in cyp734a4 mutants were significantly shorter than those in WT (Fig. 5d, e), with significant panicle enclosure. In oslis-l1 mutants, PE and UI were also significantly reduced (Fig. 6d, e), which was similar to the results from Gao et al. (2012). These results indicate that the CYP734A4 and OsLIS-L1 genes might be target candidate genes for the qPE14 and qUI14, and qPE19 loci respectively.

Fig. 5.

Identification of CYP734A4 as the causal gene for qPE14 and qUI14. a Schematic presentation of the gene structure of CYP734A4 and T-DNA insertion sites in cyp734a4 mutants. b P1/P2 and P1/P3 are two pairs of primers used to amplify CYP734A4 DNA for PCR analysis. c PCR analysis of WT and cyp734a4 mutants. d, e PE and UI of WT and cyp734a4 mutants. ** indicates a significant difference compared to WT at the 1% level

Fig. 6.

Identification of OsLIS-L1 as the causal gene for qPE19. a Schematic presentation of the gene structure of OsLIS-L1 and b deletion sites in oslis-l1 mutants using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. c, d PE and UI of WT and oslis-l1 mutants. ** indicates a significant difference compared to WT at the 1% level

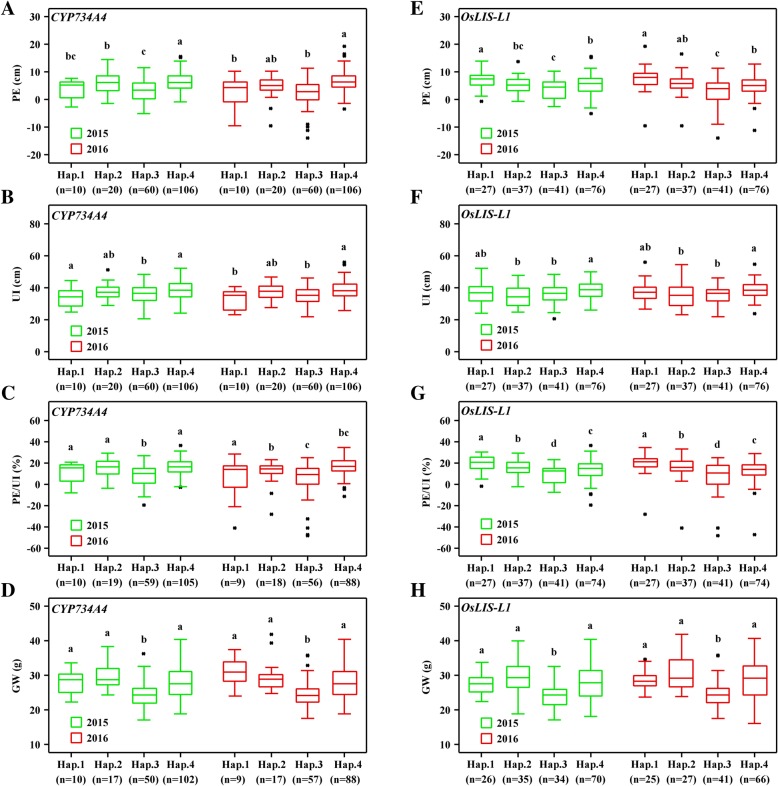

Haplotype analysis of CYP734A4 and OsLIS-L1

Based on all SNPs with an MAF > 0.05 within functional range of the 5′ flanking sequences of genes (≤2 kb from the first ATG), 4 and 4 major haplotypes in CYP734A4 and OsLIS-L1 were detected among the 205 accessions, respectively (Fig. 7). For the CYP734A4 gene, the PE of Hap.3 was significantly lower than those of Hap.2 and Hap.4 in 2015 and Hap.4 in 2016 (Fig. 7a). The UI of Hap.3 was significantly lower than those of Hap.1 and Hap.4 in 2015 and Hap.4 in 2016 (Fig. 7b). The PE/UI of Hap.3 was significantly lower than those of Hap.1, Hap.2, and Hap.4 in 2015 and those of Hap.1 and Hap.2 in 2016 (Fig. 7c). For the OsLIS-L1 gene, the PE of Hap.3 was significantly lower than those of Hap.1 and Hap.4 in 2015 and those of Hap.1, Hap.2, and Hap.4 in 2016 (Fig. 7e). The UI of Hap.3 was significantly lower than that of Hap.4 in both 2015 and 2016 (Fig. 7f). The PE/UI of Hap.3 was significantly lower than those of Hap.1, Hap.2, and Hap.4 in both 2015 and 2016 (Fig. 7g). The GW of Hap.3 for CYP734A4 and Hap.3 for OsLIS-L1 was significantly lower than those of Hap.1, Hap.2, and Hap.4 in both 2015 and 2016 respectively (Fig. 7d, h). These results suggest that Hap.3 of CYP734A4 and Hap.3 of OsLIS-L1 genes might result in lower values of PE, UI, PE/UI and 1000-GW via allelic variation within the promoter region (Additional file 2: Figure S2).

Fig. 7.

Box plots of PE, UI, PE/UI, and 1000-GW based on haplotypes of CYP734A4 (a-d) and OsLIS-L1 (e-h) in 2015 and 2016. n represents the number of accessions with a specific haplotype. The horizontal lines represent the median values, box edges represent upper and lower quantiles, and whiskers are 1.5 times the quantile of the data. Outliers are shown as open dots. Small letters above error bars indicate significant differences among haplotypes (LSD, P < 0.05). CYP734A4: Hap.1, AA; Hap.2, CN; Hap.3, AT; Hap.4, CA. OsLIS-L1: Hap.1, CCCAT; Hap.2, CTTAT; Hap.3, TCTGC; Hap.4, CCTAT

Candidate genes involved in four novel QTLs

To identify candidate genes within the two novel key PE-related (qPE16 and qPE21) and two UI-related QTLs (qUI1 and qUI18), we analysed a 200 kb genomic region by comparing the related regions with the Nipponbare reference genome (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu) by GWAS based on the results in 2015 and 2016 (Figs. 2 and 3). A total of 306 candidate genes were identified among the 4 association peaks in the surrounding genomic areas after removal of genes encoding unknown/trotransposon/retrotransposon proteins (Additional file 5: Table S4).

Gene Ontology analysis showed that there was significant enrichment in 11 functional categories (http://bioinfo.cau.edu.cn/agriGO/analysis.php) (LSD < 0.05), including 6 functional categories under biological process, 4 functional categories under cellular component, and 1 functional category under molecular function (Additional file 3: Figure S3). Among them, membrane functional type (GO: 0016020) possessed more significant differences compared to other categories(Additional file 3: Figure S3; Additional file 5: Table S5).

Further, all the significant SNPs in the candidate regions were classified into five functional groups according to Yano et al. (2016), and 28 candidate genes were screened out, including 11 genes for qPE16 on Chr. 7, six genes for qPE21 on Chr. 12, seven genes for qUI1 on Chr. 1, and four genes for qUI8 on Chr. 8 (Additional file 5: Table S5).

By comparative analysis, we found that six genes, LOC_Os01g41420 within qUI1, LOC_Os07g38530 and LOC_Os07g38810 within qPE16, LOC_Os08g15170 and LOC_Os08g15280 within qUI18, and LOC_Os12g07690 within qPE21, belonged to the membrane functional type in Gene Ontology analysis. Of these, one significant SNP was located in the coding sequence (CDS) of a gene, and five were located in promoter regions (Additional file 5: Table S5).

Discussion

In this study, none of the accessions with flag leaves under the node of the UI were found among 205 accessions from RDP1 (Zhao et al. 2011). Most of the accessions showed that the flag leaf overlapped a part of the UI, and only 10.7% of the accessions displayed panicle enclosure that would lead to reduced yield because of spikelet fertility. Statistical analysis revealed that RDP1 captures extensive natural variation in all accessions, possibly increasing the chance to identify new loci of PE and UI. Simultaneously, the extensive variation of both PE and UI were also found in either JAPONICA or INDICA groups in this study, which demonstrated that the two sub-populations could be used for GWAS. By comparison, we found that JAPONICA had significantly higher mean values than INDICA in both PE and UI, means that japonica varieties have longer PE and UI than indica varieties. Furthermore, most INDICA accessions with negative PE are from African countries (Additional file 5: Table S2), suggesting that INDICA rice may undergo panicle enclosure more easily, as reported by Guan et al. (2011).

As major components in the process of energy transportation, PE and UI have an important regulatory effect on grain filling and grain size (Zhao et al. 2016). In our study, we found that PE had a significantly positive correlation with 1000-GW, but UI had no significant correlation with 1000-GW. These results suggest that PE may be more important in the regulation of grain weight than UI. It is well known that HD is one of the most important agronomic traits in rice (Takahashi et al. 2009; Matsubara et al. 2011). Correlation analysis showed that HD had a significantly negative correlation with PE, which was similar to the results reported by Zhao et al. (2016), and a significantly positive correlation with UI. This suggests that HD has different impacts on PE and UI in rice in the field. Meanwhile, there was a significantly positive correlation between PE and UI, indicating that panicle enclosure can be prevented when extending UI in rice breeding.

To dig new QTLs controlling PE and UI would contribute to understanding its the genetic control and elucidating the phenomenon of panicle enclosure. In our study, we identified 46 associated loci based on 205 natural rice accessions from RDP1 via GWAS, including 22 loci from PE and 24 loci from UI. By comparing the chromosomal positions, 10 loci for PE and seven loci for UI in our study were located in the previously reported QTLs/genes. The qPE2 was near the region of qPE1 (Zhao et al. 2016), and qPE3 co-located with sd1 (Ayano et al. 2014). The qPE8, qPE9, qPE10, qUI6, and qUI7 locations were all close to the region of qPE3 (Zhao et al. 2016). qPE22, qUI23, and qUI24 were all located near the region of qGTIL12 (Nagai et al. 2014). qPE13 was near the region of ipe.4.1 (Herlina et al. 2016). qUI2 and qUI20 were located within qPEL1.2 and eui2, respectively (Dang et al. 2017). qPE19 was co-located with OsLIS-L1 (Gao et al. 2012). qPE14 and qUI14 were co-located with CYP734A4 (Qian et al. 2017). However, there were still 12 loci for PE and 17 loci for UI that had not been previously reported, which might be novel QTLs.

By comparing these QTLs, we found that more loci in INDICA were identified than in JAPONICA, and 15 loci for PE and 22 loci for UI were not shared between in INDICA and JAPONICA, supporting the earlier notion that JAPONICA and INDICA were domesticated independently from different geographical and ecological locations (Kovach et al. 2007). Eight PE-related and nine UI-related loci were showed to be simultaneously detected in both 2015 and 2016 as inter-year comparison, suggestting that they are relatively stable and less affected by the environment. Besides, we found that seven pairs of loci, including qPE4 and qUI2 on chromosome 1, qPE9 and qUI6 on chromosome 3, qPE10 and qUI7 on chromosome 3, qPE12 and qUI11 on chromosome 4, qPE14 and qUI14 on chromosome 6, qPE15 and qUI16 on chromosome 7, and qPE22 and qUI23 on chromosome 12, had consistent physical positions between PE and UI, implied that these loci could control both PE and UI.

The cloning of the key genes of PE and UI might be helpful to characterize the molecular mechanism. Hence, four novel loci (qPE16, qPE21, qUI1, and qUI18) were further explored to find causal genes for rice breeding. Through gene ontology analysis and functional classification, six potential functional candidate genes (LOC_Os01g41420, LOC_Os07g38530, LOC_Os07g38810, LOC_Os08g15170, LOC_Os08g15280, and LOC_Os12g07690) were ultimately identified, which were primarily involved in amino acid transport, energy metabolism, and protein kinases, suggesting they might be involved in regulating PE and UI in rice. However, whether they have a causal link to these traits remains to be further validated in transgenic plants in the future.

The OsLIS-L1 (Gao et al. 2012) gene within qPE19 was reported to regulate cell proliferation in UI, and the CYP734A4 gene within qPE14 and qUI14 were reported to cause dwarfism in the mutant plants (Qian et al. 2017). Plant dwarfism has a significant correlation with UI according to the reports by Guan et al. (2011) and Duan et al. (2012). In our study, we also found the similar results that PE and UI in either oslis-l1 or cyp734a4 mutants were significantly shorter than those of WT, suggesting that OsLIS-L1 and CYP734A4 genes may be the causal genes with important regulatory role in PE and UI.

Superior alleles play an important role in breeding. To identify superior alleles for rice MAS, the haplotypes of CYP734A4 and OsLIS-L1 genes were analysed on PE, UI, and 1000-GW traits in this study. We found that average values of PE, UI, and PE/UI associated with Hap.3 of CYP734A4 and Hap.3 of OsLIS-L1 were lower than other types in 2015 and 2016, respectively. The 1000-GW of Hap.3 of CYP734A4 and Hap.3 of OsLIS-L1 was also reduced, as were PE and UI. In other words, Hap.1, Hap.2, and Hap.4 of CYP734A4 and Hap.1, Hap.2, and Hap.4 of OsLIS-L1 both increased PE, UI and 1000-GW. Furthermore, we found that significant differences between Hap.3 and Hap. 1/2/4 of CYP734A4 and OsLIS-L1 were caused by the significant SNP-6.23703769, SNP-8.3664103, SNP-8.3665235, and SNP-8.3666556 in promoter areas. Hence, these SNPs could be exploited as molecular markers to screen the superior alleles of the CYP734A4 and OsLIS-L1 genes, reduce panicle enclose and improve yield for rice breeding.

Methods

Plant materials

The natural population used for GWAS was composed of 205 rice (Oryza sativa L.) accessions from RDP1 inputted by Dr. Susan McCouch at Cornell University (Zhao et al. 2011). These accessions were divided into the JAPONICA group, which included 52 tropical japonica (TRJ), 59 temperate japonica (TEJ) and 3 AROMATIC accessions, and the INDICA group, which included 24 AUS, 33 indica (IND), and 34 ADMIX accessions. Detailed information regarding accessions is shown in Additional file 5: Table S2. Seeds were obtained by Dr. Jian Hua at Cornell University from the McCouch lab. The T-DNA mutants of the CYP734A4 gene were provided by Dr. Wenzhen Liu (Qian et al. 2017), and the T-DNA insertion site and homozygous lines of cyp734a4 were identified by PCR analysis of genomic DNA using gene-specific primers (Additional file 5: Table S6). The CRISPR/Cas9 mutants of OsLIS-L1 were generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system in this study.

Field experiments

All accessions were grown in a paddy field at the Experimental Station of Nanjing Agricultural University (Jiangsu Province, China; 32.020° N, 118.500° E) in 2015 and 2016. Fifty plants of each accession were planted in one plot with a space of 17 cm between plants and 33 cm between rows, and each plot contained five rows (10 plants/row). For investigating of PE and UI traits, five plants in the middle two rows of each accession were randomly selected and were harvested at 35 days after heading. Their grains after 40 °C drying for 3 days were used for 1000-GW measurement.

Generation of transgenic plants

The CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid was designed according to the protocol described previously (Xing et al. 2014). Two target sites of OsLIS-L1 were confirmed via CRISPR-PLANT (http://www.genome.arizona.edu/crispr/CRISPRsearch.html). The target segment, totalling 964 bp, was obtained by amplifying the pCBC-MT1T2 vector using the BsF, F0, R0, and BsR primers, cloned into the pBUE411 vector, and then verified using the FD2, RD, and FD3 primers to develop transgenic plants. Genomic DNA was extracted from mutant seedlings using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Murray and Thompson, 1980). The PCR products were amplified with specific F and R primers and directly sequenced to detect the mutants. The positive mutants, in which that the second target site had a deletion mutant on the third coding exon, were finally selected. All primers are listed in Additional file 5: Table S6.

Phenotype assessment

The leading panicle of each plant were selected to measure the PE and UI using a ruler. PE (in cm) was defined as the length from the sheath of the flag leaf to panicle base. When the base of the panicle was under the sheath of the flag leaf, a negative value was assigned. UI (in cm) was measured from the uppermost node to panicle base. The averaged values were used for data analyses. PE/UI was defined as the ratio of PE to UI. when the flag leaf overlapped a part of the PE, the value of PE/UI was marked as 0 < PE/UI < 1; when the flag leaf enclosed the panicle partly or fully, the value of PE/UI was marked as PE/UI ≤ 0; and when the flag leaf was under the node of the UI, the value of PE/UI was marked as PE/UI ≥ 1. In addition, HD was defined as when 80% of the leading panicle emerged from the leaf sheath in each plot (Lu et al. 2011). 1000-GW was measured using an electronic balance (measured to the nearest 0.0001 g).

Genome-wide association analyses

The 700 K rice SNP marker set was used for GWAS as described by McCouch et al. (2016). Only the SNPs with nucleotide variations with missing rates < 0.25 and minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.05 were used for GWAS in INDICA, JAPONICA and All populations (Yano et al. 2016). The result was SNP genotype data with 386,251 biallelic markers selected. These filtering steps were performed using TAEELE software version 5.0 (Bradbury et al., 2007). A linear mixed-model GWAS was then carried out using the EMMAX suite in Linux (Kang et al. 2010). The significance threshold P < 1.0e-4 was used, as in previous studies (Zhao et al. 2011; McCouch et al. 2016). Manhattan (Figs. 2 and 3) and Quantile-Quantile plots (Additional file 4: Figure S4) of GWAS results were made using the package qqman in R (Rebolledo et al. 2015). Significant-SNP clusters, that had clear peak-like signals and physical regions of any two significant SNPs were less than 200 kb, were considered to be one associated locus (Lu et al. 2016). The corresponding locus regions were determined by the significant SNPs on both ends. Candidate genes were predicted according to the Rice Genome Annotation Project MSU7 database (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu), and were classified into five functional groups according to Yano et al. (2016) based on all the significant SNPs in their regions.

Haplotype analyses

For the CYP734A4 and OsLIS-L1 genes, the haplotypes were classified based on all SNPs with an MAF > 0.05 within functional range of the 5′ flanking sequence of a gene (≤2 kb from the first ATG) and the CDS of the target gene (Butardo et al. 2016). The haplotypes containing at least 5 investigated accessions were used for comparative analysis (Wang et al. 2015). Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test was conducted to compare the differences in PE, UI, and 1000-GW (He et al. 2015).

Gene ontology analysis

A total of 306 candidate genes from four QTLs, qPE16, qPE21, qUI1, and qUI18, were submitted to the ‘AgriGO’ ontology enrichment facility (http://bioinfo.cau.edu.cn/agriGO/analysis.php) (Additional file 5: Table S4), which was based on Fisher’s exact test and a Yekutieli multi-test adjustment, using a 5% false-positive detection threshold.

Statistical analyses

Phenotype data and variance (ANOVA) were analysed by Excel 2016 software. Broad-sense heritability (HB2) was calculated using the following equation:

where is the genotypic variance, στβ2 is the genotype-by-environment interaction variance, σ2 is the experimental error variance, n is the number of replicates and b is the number of environments. Correlation coefficients (LSD, P < 0.05) of PE, UI, PE/UI, 1000-GW, and HD were computed using PROC CORR in SAS software.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Fig. S1. A heat map depicting Pearson’s correlation coefficients among PE, UI, 1000-GW and HD in 2015 (lower triangle) and 2016 (upper triangle) for 205 accessions in the study. * and ** indicate significant correlations at the 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively.

Additional file 2. Fig. S2. Gene structure and haplotypes of CYP734A4 (A) and OsLIS-L1 (B) identified in the CDS or promoter region. Green boxes and solid lines represent exons and introns, respectively. -49 T SNP (A) and -2547 T SNP, −1415G SNP, and -94C SNP (B) are the most significantly negatively associated with PE and UI.

Additional file 3. Fig. S3. Ontology analysis of candidate genes from qPE16, qPE21, qUI1, and qUI18. Proportions are shown for enriched (P < 0.05) functional categories. Data are obtained from comparisons of numbers of genes in the experimental (Input) and reference sets at ‘AgriGO’ (http://bioinfo.cau.edu.cn/agriGO/analysis.php). The blue bar represents the target candidates selected genes, and the red bar represents the rice reference genome genes.

Additional file 4. Fig. S4. QQ plots for PE and UI observed versus expected -log10(P) in All (A), JAPONICA (B), and INDICA groups (C) in 2015 and 2016. The red dashed line in each plot represents an idealized case where the theoretical test statistic quartile matches the simulated test statistic quartile.

Additional file 5: Table S1. The descriptive statistics of PE and UI for the All, JAPONICA, and INDICA groups in 2015 and 2016. Table S2. Information about the 205 accessions used in this study and phenotypic data of PE and UI observed in 2015 and 2016. Table S3. Genome-wide significant association loci of PE and UI for the All, JAPONICA, and INDICA groups in 2015 and 2016. Table S4. All the candidate genes identified for key novel loci qPE16, qPE21, qUI1, and qUI18 (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu). Table S5. Candidate genes screened as functional classification of genes for key novel loci qPE16, qPE21, qUI1, and qUI18. Table S6. Primer pairs used for gene cloning and PCR analyses in this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would thank Dr. Jian Hua at Cornell University and Nanjing Agricultural University for providing rice seeds and Dr. Susan McCouch at Cornell University for inputting on using this panel for GWAS. Thanks to Dr. Wenzhen Liu at the China National Rice Research Institute for providing the T-DNA mutant seeds of CYP734A4.

Abbreviations

- 1000-GW

1000-grain weight

- GWAS

Genome-wide association studies

- HD

Heading date

- MAS

Marker-assisted selection

- PE

Panicle exsertion

- QTLs

Quantitative trait loci

- RDP1

Rice diversity panel

- SNP

Single-nucleotide polymorphism

- UI

Uppermost internode

Authors’ contributions

CF Zhan, and JP Cheng designed the experiment and wrote the manuscript. CF Zhan, JX Hu, and Q Pang conducted the experiments and performed data analysis. B Yang, YH Cheng, ES Xu, PW Zhu and YY Li participated in material development, sample preparation and data analysis. CF Zhan, JP Cheng and HS Zhang drafted proposals and corrected the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31601387, 31771757), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No. KJQN201727) and the Science and Technology Project of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BE2016380).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are provided within the article and its additional files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hongsheng Zhang, Email: hszhang@njau.edu.cn.

Jinping Cheng, Email: cjp@njau.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12284-019-0330-x.

References

- Ayano M, Kani T, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Kitaoka T, Kuroha T, Angeles-Shim RB, Kitano H, Nagai K, Ashikari M. Gibberellin biosynthesis and signal transduction is essential for internode elongation in deep water rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2014;37(10):2313–2324. doi: 10.1111/pce.12377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury PJ, Zhang ZW, Kroon DE, Casstevens TM, Ramdoss Y, Buckler ES. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(19):2633–2635. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butardo VM, Anacleto R, Parween S, Samson I, Guzman KD, Alhambra CM, Misra G, Sreenivasulu N. Systems genetics identifies a novel regulatory domain of amylose synthesis. Plant Physiol. 2016;173(1):01248.2016. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Cruz RP, Milach SCK, Federizzi LC. Inheritance of panicle exsertion in rice. Sci Agric. 2008;65:502–507. doi: 10.1590/S0103-90162008000500009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dang XJ, Fang BJ, Chen XG, Li DL, Sowadan O, Dong ZY, Liu EB, She D, Wu GC, Liang YY, Hong DL (2017) Favorable marker alleles for panicle exsertion length in rice (Oryza sativa L.) mined by association mapping and the RSTEP-LRT method. Front Plant Sci 8:2112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- DUAN Yuan-lin, GUAN Hua-zhong, ZHUO Ming, CHEN Zhi-wei, LI Wen-tao, PAN Run-sen, MAO Da-mei, ZHOU Yuan-chang, WU Wei-ren. Genetic Analysis and Mapping of an Enclosed Panicle Mutant Locus esp1 in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Journal of Integrative Agriculture. 2012;11(12):1933–1939. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(12)60449-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Famoso AN, Zhao K, Clark RT, Tung CW, Wright MH, Bustamante C, Kochian LV, McCouch SR. Genetic architecture of aluminum tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa) determined through genome-wide association analysis and QTL mapping. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao SP, Fang J, Xu F, Wang W, Chu CC. Rice HOX12 regulates panicle exsertion by directly modulating the expression of ELONGATED UPPERMOST INTERNODE1. Plant Cell. 2016;28(3):680–695. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.01021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao XQ, Chen ZH, Zhang J, Li XW, Chen GX, Li XH, Wu CY. OsLIS-L1 encoding a lissencephaly type-1-like protein with WD40 repeats is required for plant height and male gametophyte formation in rice. Planta. 2012;235(4):713–727. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1532-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan HZ, Duan YL, Liu HQ, Cheng ZW, Zhuo M, Zhuang LJ, Qi WM, Pan RS, Mao DM, Zhou YC, Wang F, Wu WR. Genetic analysis and fine mapping of an enclosed panicle mutant esp2 in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Chin Sci Bull. 2011;56(14):1476–1480. doi: 10.1007/s11434-011-4552-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han B, Huang XH. Sequencing-based genome-wide association study in rice. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2013;16(2):133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YQ, Cheng JP, Liu LF, Li XD, Yang B, Zhang HS, Wang ZF. Effects of pre-harvest chemical application on rice desiccation and seed quality. J Zhejiang Univ-Sci B. 2015;16(10):813–823. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1500032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlina L, Sobir S, Trijatmiko KR (2016) Identification of quantitative trait loci (QTL) for awn, incomplete panicle exertion and total spikelet number in an F2 population derived from a backcross inbred line, Bio-148, and the recurrent parent, IR64. Makara J Sci 21(1):17–27

- Huang XH, Wei XH, Sang T, Zhao Q, Feng Q, Zhao Y, Li CY, Zhu CR, Lu TT, Zhang ZW, Li M, Fan DL, Guo YL, Wang AH, Wang L, Deng LW, Li WJ, Lu YQ, Weng QJ, Liu KY, Huang T, Zhou TY, Jing YF, Li W, Lin Z, Buckler ES, Qian Q, Zhang QF, Li JY, Han B. Genome-wide association studies of 14 agronomic traits in rice landraces. Nat Genet. 2010;11(42):961–969. doi: 10.1038/ng.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji H, Kim H, Yun DW, Yoon UH, Kim TH, Eun MY, Lee GS. Characterization and fine mapping of a shortened uppermost internode mutant in rice. Plant Biotech Rep. 2014;8(2):125–134. doi: 10.1007/s11816-013-0280-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Yan W, Zhu C, Agrama HA, Jackson A, Yeater K, Li X, Huang B, Hu B, McClung A, Wu D. Allelic analysis of sheath blight resistance with association mapping in rice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HM, Sul JH, Service SK. Zaitlen NA, Kong SY, Freimer NB, Sabatti C, Eskin E. Variance component model to account for sample structure in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2010;42(4):348–354. doi: 10.1038/ng.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach MJ, Sweeney MT, McCouch SR. New insights into the history of rice domestication. Trends Genet. 2007;23(11):578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JY, Wang J, Zeigler RS. The 3,000 rice genomes project: new opportunities and challenges for future rice research. Gigascience. 2014;3(1):1–3. doi: 10.1186/2047-217X-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GL, Mei HW, Yu XQ, Zou GH, Liu HY, Hu SP, Li MS, Wu JH, Chen L, Luo LJ. QTL analysis of panicle neck diameter, a trait highly correlated with panicle size, under well-watered and drought conditions in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Plant Sci. 2008;174(1):71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2007.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Xie K, Yang C, Wang S, Liu X, Zhang L, Jiang L, Wan J. Mapping two major effect grain dormancy QTL in rice. Mol Breed. 2011;28:453–462. doi: 10.1007/s11032-010-9495-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Zhang MC, Niu XJ, Wang CH, Xu Q, Yue F, Shan W, Yuan XP, Yu HY, Wang YP, Wei XH. Uncovering novel loci for mesocotyl elongation and shoot length in indica rice through genome-wide association mapping. Planta. 2016;243(3):645–657. doi: 10.1007/s00425-015-2434-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Anding, Qian Qian, Yin Hengfu, Liu Xiaoqiang, Yin Changxi, Lan Ying, Tang Jiuyou, Tang Zuoshun, Cao Shouyun, Wang Xiujie, Xia Kai, Fu Xiangdong, Luo Da, Chu Chengcai. EUI1, Encoding a Putative Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenase, Regulates Internode Elongation by Modulating Gibberellin Responses in Rice. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2006;47(2):181–191. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma HL, Zhang SB, Ji L, Zhu HB, Yang SL, Fang XJ, Yang RC. Fine mapping and in silico isolation of the EUI1 gene controlling upper internode elongation in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;60:87–94. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-2762-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Cheng ZJ, Chen J, Shen JB, Zhang BC, Ren YL, Ding Y, Zhou YH, Zhang H, Zhou KN, Wang JL, Lei CL, Zhang X, Guo XP, Gao H, Bao YQ, Wan JM. Phosphatidylserine synthase controls cell elongation especially in the uppermost internode in Rice by regulation of exocytosis. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Zhou KD, Ma WB, Wang XD, Tian YH, Ming DF, Xu FY. The characteristics of the tissues of the first internode and their relations to the grain-filling for the different panicle types of rice. Acta Agron Sinica. 2002;28:215–220. [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara K, Yamanouchi U, Nonoue Y, Sugimoto K, Wang ZX, Minobe Y, Yano M. Ehd3, encoding a plant homeodomain finger-containing protein, is a critical promoter of rice flowering. Plant J. 2011;66(4):603–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCouch SR, Wright MH, Tung CW, Maron LG, Mcnally KL, Fitzgerald M, Singh N, Declerck G, Agosto-Perez F, Korniliev P. Open access resources for genome-wide association mapping in rice. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10532. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MG, Thompson WF. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8(19):4321–4325. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai K., Kondo Y., Kitaoka T., Noda T., Kuroha T., Angeles-Shim R. B., Yasui H., Yoshimura A., Ashikari M. QTL analysis of internode elongation in response to gibberellin in deepwater rice. AoB PLANTS. 2014;6(0):plu028–plu028. doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plu028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian WJ, Wu C, Fu YP, Hu GC, He ZQ, Liu WZ. Novel rice mutants overexpressing the brassinosteroid catabolic gene CYP734A4. Plant Mol Biol. 2017;93(1–2):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0558-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao BJ, Zhu XB, Wang YY, Hong DL. Mapping of QTL for three panicle exsertion-related traits in rice under different growing environments. Acta Agron Sin. 2008;34(3):389–396. [Google Scholar]

- Rebolledo MC, Dingkuhn M, Courtois B, Gibon Y, Clémentvidal A, Cruz DF, Duitama J, Lorieux M, Luquet D. Phenotypic and genetic dissection of component traits for early vigour in rice using plant growth modelling, sugar content analyses and association mapping. J Exp Bot. 2015;66(18):5555. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Teshima KM, Yokoi S, Shimamoto IH. Variations in Hd1 proteins, Hd3a promoters, and Ehd1 expression levels contribute to diversity of flowering time in cultivated rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(11):4555–4560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812092106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang QX, Xie WB, Xing HK, Yan J, Meng XZ, Li XL, Fu XK, Xu JY, Lian XM, Yu SB, Xing YZ, Wang GW. Genetic architecture of natural variation in rice chlorophyll content revealed by a genome-wide association study. Mol Plant. 2015;8(6):946–957. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing HL, Dong L, Wang ZP, Zhang HY, Han CY, Liu B, Wang XC, Chen QJ. A CRISPR/Cas9 toolkit for multiplex genome editing in plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14(1):327. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0327-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano K, Yamamoto E, Aya K, Takeuchi H, Lo PC, Hu L, Yamasaki M, Yoshida S, Kitano H, Hirano K, Matsuoka M. Genome-wide association study using whole-genome sequencing rapidly identifies new genes influencing agronomic traits in rice. Nat Genet. 2016;48(8):927. doi: 10.1038/ng.3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin CX, Gan LJ, Ng D, Zhou X, Xia K. Decreased panicle-derived indole-3-acetic acid reduces gibberellin A1 level in the uppermost internode, causing panicle enclosure in male sterile rice Zhenshan 97A. J Exp Bot. 2007;58(10):2441–2449. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HF, Gao P, Liu CW, Yang J, Liu ZC, Luo D. SUI-family genes encode phosphatidylserine synthases and regulate stem development in rice. Planta. 2013;237:15–27. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao CF, Chen T, Zhao QY, Zhou LH, Zhao L, Zhang YD, Zhu Z, Yao S, Wang CL (2016) Analysis of QTLs for panicle exsertion and its relationship with yield and yield-related traits in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Genet Mol Res 15(2):gmr.15027423 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhao CF, Zhao QY, Zhao L, Zhou LH, Chen T, Yao S, Liang WH, Zhang YD, Wang CL. Characterization and fine mapping of qPE12 , a new locus controlling rice panicle exsertion. Euphytica. 2018;214(3):47. doi: 10.1007/s10681-017-2104-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao KY, Tung CW, Eizenga GC, Wright MH, Ali ML, Price AH, Norton GJ, Islam MR, Reynolds A, Mezey J. Genome-wide association mapping reveals a rich genetic architecture of complex traits in Oryza sativa. Nat Commun. 2011;13(2):467. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Hu J, Zhu KM, Fang YX, Gao ZY, He YH, Zhang GH, Guo LB, Zeng DL, Dong GJ, Yan MX, Liu J, Qian Q. Identification and characterization of SHORTENED UPPERMOST INTERNODE 1, a gene negatively regulating uppermost internode elongation in rice. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;77:475–487. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9825-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu YY, Nomura T, Xu YH, Zhang YY, Peng Y, Mao BZ, Hanada A, Zhou HC, Wang RX, Li PJ, Zhu XD, Mander LN, Kamiya YJ, Yamaguchi S, He ZH. ELONGATED UPPERMOST INTERNODE encodes a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase that epoxidizesgibberellins in a novel deactivation reaction in rice. Plant Cell. 2006;2(18):442–456. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.038455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Fig. S1. A heat map depicting Pearson’s correlation coefficients among PE, UI, 1000-GW and HD in 2015 (lower triangle) and 2016 (upper triangle) for 205 accessions in the study. * and ** indicate significant correlations at the 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively.

Additional file 2. Fig. S2. Gene structure and haplotypes of CYP734A4 (A) and OsLIS-L1 (B) identified in the CDS or promoter region. Green boxes and solid lines represent exons and introns, respectively. -49 T SNP (A) and -2547 T SNP, −1415G SNP, and -94C SNP (B) are the most significantly negatively associated with PE and UI.

Additional file 3. Fig. S3. Ontology analysis of candidate genes from qPE16, qPE21, qUI1, and qUI18. Proportions are shown for enriched (P < 0.05) functional categories. Data are obtained from comparisons of numbers of genes in the experimental (Input) and reference sets at ‘AgriGO’ (http://bioinfo.cau.edu.cn/agriGO/analysis.php). The blue bar represents the target candidates selected genes, and the red bar represents the rice reference genome genes.

Additional file 4. Fig. S4. QQ plots for PE and UI observed versus expected -log10(P) in All (A), JAPONICA (B), and INDICA groups (C) in 2015 and 2016. The red dashed line in each plot represents an idealized case where the theoretical test statistic quartile matches the simulated test statistic quartile.

Additional file 5: Table S1. The descriptive statistics of PE and UI for the All, JAPONICA, and INDICA groups in 2015 and 2016. Table S2. Information about the 205 accessions used in this study and phenotypic data of PE and UI observed in 2015 and 2016. Table S3. Genome-wide significant association loci of PE and UI for the All, JAPONICA, and INDICA groups in 2015 and 2016. Table S4. All the candidate genes identified for key novel loci qPE16, qPE21, qUI1, and qUI18 (http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu). Table S5. Candidate genes screened as functional classification of genes for key novel loci qPE16, qPE21, qUI1, and qUI18. Table S6. Primer pairs used for gene cloning and PCR analyses in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are provided within the article and its additional files.