Abstract

Objectives

Recently, the incidence of alcohol-related liver disease has been rising alarmingly in India with late presentation and short survival. Better delineation of factors affecting mortality is needed for optimal utilization of constrained resources like liver transplantation.

Methods

Baseline data of 395 patients with alcohol-related liver disease including age, clinical presentation, alcohol parameters (amount, duration, type), laboratory parameters for detecting organ failure, and prognostic scores were compared between survivor and deceased groups. Further subgroup analysis of deceased patients was done to identify factors associated with early mortality in acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) and cirrhosis groups by multivariate analysis and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Only best supportive medical therapy was offered to all.

Results

80 (20.3%) patients had alcoholic hepatitis (without cirrhosis) and recovered completely with abstinence. 315 (79.7%) had evidence of either cirrhosis (n = 182, 46.1%) or ACLF (n = 133, 33.6%) at presentation and all died within the next 2 years of follow-up, earlier in the ACLF cases. All deceased patients had been heavy drinkers for long periods (>85 g/day for >17 years). Higher age, amount of alcohol consumption, number of organ failures and discriminant function score predicted severe disease and early mortality, the latter being the best predictor. The European Foundation for the study of chronic liver failure consortium (CLIF-C) score has good applicability in Indian ACLF cohorts. Serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase was normal in 73.8% of deceased patients compared to only 12.5% of survivors. Abstinence did not result in complete normalization of deranged laboratory parameters in those who died.

Conclusion

Alcohol-related liver disease is serious with high short-term mortality, which has early identifiable but mostly irreversible factors. Urgent measures need to be taken to curb this rising menace.

Keywords: Alcohol, Hepatitis, Acute-on-chronic liver failure, Cirrhosis, Mortality

Introduction

Alcohol-related disorders constitute one of the significant health problems worldwide of which cirrhosis of the liver is a major contributor and staggering health costs are incurred on it all over the world [1, 2]. The recent Global Burden of Disease Study has shown a similar trend in India with alcohol appearing among the first 10 causes of maximum disability-adjusted life years (DALY) in 2016, with a rise of 76% from 1990 [3]. Other series on cirrhosis [4, 5, 6, 7, 8] and liver transplant [9, 10] from India show alcohol to have become the commonest cause of cirrhosis. The incidence of alcohol-related liver disease has been rising alarmingly in India in recent times [11, 12] mostly due to the rising quantity and duration of consumption starting from early age. Hence the majority of patients are young in their most productive years of life socioeconomically, which negatively impacts society. Due to late presentation and short survival after presentation, there is an increased demand for liver transplantation (mostly from a live donor in the family) as an urgent life-saving measure in spite of ethical and socioeconomic dilemmas. The menace further strains the limited organ resources of the country in addition to the high cost of liver transplant and its ancillary support and with unnecessary wastage of organs (due to recidivism and relapse) [13] and health hazards for the donor. Apart from cirrhosis, the other chief cause of early mortality in alcohol-related liver diseasepatients that is increasingly being recognized is acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) where compensated cirrhosis undergoes a sudden dip in function (mostly due to continuing alcohol intake causing superadded alcoholic hepatitis) with high short-term mortality related to systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis, and multiorgan failure [14, 15, 16]. Thus, the entities of alcohol-related cirrhosis, ACLF and hepatitis, are actually not distinct but may exist simultaneously in the same patient. Recent studies from Europe have shown ACLF to occur in >65% of patients presenting with “alcoholic hepatitis” [17]. In India, because of the late presentation, ACLF is likely to be even more prevalent. As per the 2014 APASL criteria [18], ACLF is defined as “acute hepatic insult manifesting as jaundice (bilirubin ≥5 mg/dL) and coagulopathy (INR ≥1.5), complicated within 4 weeks by clinical ascites (grade 2–3) and/or encephalopathy in a patient with previously diagnosed or undiagnosed chronic liver disease.” Patients with prior decompensated cirrhosis (e.g., worsening of chronic hepatic encephalopathy or uncontrolled ascites) are not considered to be having ACLF. Better delineation of factors which affect mortality in these groups is needed for deciding on early organ allocation versus best supportive medical therapy for optimal utilization of resources.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective single-center study from January 2011 to December 2016 where data of all patients suffering from alcohol-related liver diseaseattending the outpatient liver clinic or admitted to hospital were collected prospectively till death or last follow-up and analyzed for delineation of factors affecting the outcome. Patients with clinical and/or investigational evidence of liver dysfunction and significant alcohol intake (i.e., daily intake of more than 40 g for a prolonged period in men) were included. Other causes of cirrhosis like viral, autoimmune, biliary, metabolic disorders and drugs were excluded by appropriate history, clinical examination, and laboratory testing. Any patient having additional etiology of liver disease or significant systemic disease diagnosed before the entry into the study was excluded. All patients were advised strict abstinence and monthly follow-up. Patients with improper follow-up or missing data were excluded from analysis but their status till last follow-up was considered separately (Fig. 1). Active alcoholism was defined as per DSM-V criteria [19] and its frequency, amount, and type were elicited (including history of binge drinking, i.e., >5 drinks within 2 h at any time and drinking outside meal times) from the patient, spouse, relatives or friends. Type of alcohol was classed into local (country liquor), Indian-made foreign liquor (spirits) or mixed (combination of the two). The amount of alcohol intake was calculated from the concentration: e.g., 10 g of pure alcohol roughly equals 30 mL of Indian-made foreign liquor (concentration 40% by volume, e.g., spirits), 100 mL of wine or 250 mL of beer. Alcohol concentration in local country-made liquor is variable (25–50% by volume). Hence, the similar 10 g = 30 mL formula was also applied in this case.

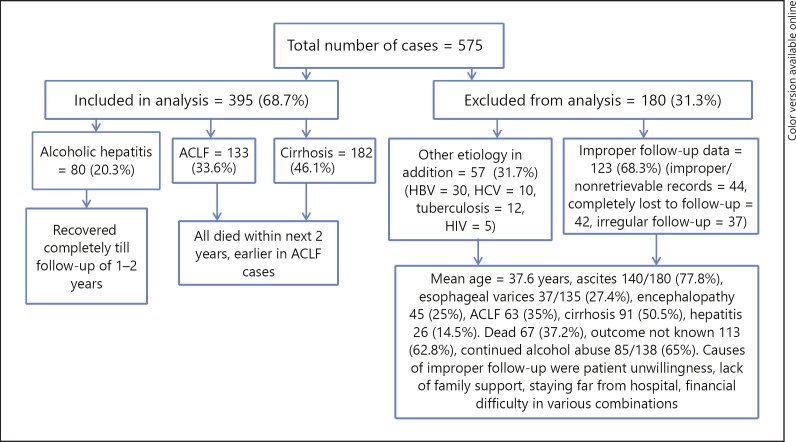

Fig. 1.

Breakup of patients with their outcome. ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure.

All patients underwent thorough clinical examination and baseline biochemical testing. Cirrhosis was diagnosed based on clinical (presence of jaundice, ascites, encephalopathy, variceal bleed, splenomegaly or history of previous such complaints), biochemical (high bilirubin, low albumin, deranged prothrombin time or altered liver enzyme with serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase [SGOT]/serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase [SGPT] >1), radiological (ultrasonogram or computerized tomography scan of the abdomen showing altered liver size with coarse echotexture and irregular surface, splenomegaly, ascites and features of portal hypertension) and endoscopic (esophageal or gastric varices, portal hypertensive gastropathy) criteria considered together or if documented on previous liver biopsy. ACLF was defined as per APASL criteria [18]. Apart from alcohol, other causes of acute hepatic insult like hepatotropic viruses (A, B, C, and E) and drugs (including complementary and alternative medicines) were excluded by appropriate history and laboratory tests. Organ failures were defined as (a) renal (creatinine >1.5 mg/dL in the absence of other causes of kidney disease), (b) hepatic encephalopathy (as per West Haven criteria) in the absence of other acute neurological disease, and (c) circulatory dysfunction (mean arterial pressure <70 mm Hg or needing inotrope support). Sepsis was diagnosed in the presence of high total leukocyte count with neutrophilia and procalcitonin/C-reactive protein level (>0.5 μg/mL/>10 mg/L) and/or features of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Infections were diagnosed either by culture (of blood, urine, ascitic fluid) positivity or by evidence of infection on chest imaging, urine microscopy, ascitic fluid polymorphonuclear count more than 250 cells/mL, clinical examination compatible with cellulitis or bacterial infection at any other site. Alcoholic hepatitis was defined as recent onset of jaundice with SGOT/SGPT (both in 100s) >1.5–2 without clinical/ultrasonological evidence of cirrhosis or liver decompensation (i.e., ascites and/or encephalopathy) in patients with recent (within 1 month) heavy consumption of alcohol and they were followed for future signs of decompensation. Baseline data included age, sex, clinical presentation, alcohol parameters (amount, duration, type), laboratory parameters (hemogram, liver function tests, including gamma glutamyl transferase, renal function tests, prothrombin time, viral and autoimmune markers of liver disease for exclusion), chest X-ray, findings on abdominal sonography and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. To address the severity of liver disease, prognostic scores like Maddrey's discriminant function (DF), Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP), Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-sodium (MELD-Na) were calculated from the above clinical and biochemical parameters. Incremental ranges of DF and MELD scores above that considered as mild disease (i.e., 32 for DF and 15 for MELD) were considered for analyzing their effect on outcome. We also calculated the European Foundation for the study of chronic liver failure consortium (CLIF-C) ACLF score [20] after 48 h of hospital entry (used for prognostication of ACLF in European cohorts) in our cohort of ACLF for comparison with other prognostic scores. Liver biopsy was not done for diagnosis because of risk or refusal by the patient.

All patients of alcoholic hepatitis were first offered the best supportive medical care in form of lactulose, ursodeoxycholic acid, metadoxine, S-adenosyl methionine, rifaximin, and pentoxifylline for at least 2 weeks with serial monitoring of liver function tests weekly. If it improved, drugs were continued till complete recovery. Steroid was reserved only for those who did not improve and had a DF score >32. Patients with ACLF or cirrhosis were also given the above drugs along with spironolactone for ascites, L-ornithine L-aspartate for hepatic encephalopathy, variceal banding, injection of octreotide and beta blockers for esophageal varices, inotropic agents for circulatory failure, dialysis and ventilator support in the intensive care unit, and intravenous antibiotics, albumin, and vitamins in various combinations as appropriate for each patient. Steroid was avoided in patients having ascites and/or sepsis even if their DF score was >32 for risk of worsening sepsis or hepatic failure. Nutritional management in hospital included a balanced diet with protein 1–1.5 g/kg body weight (in those without encephalopathy), vitamins, and calcium with intravenous nutritional support if needed. Patients were also advised a similar diet at discharge. Follow-up investigations included monthly hemogram, liver function tests, renal function tests, and prothrombin time till recovery or death. Subsequent follow-up interval depended on the clinical condition of the patient. All patients were also free to attend the hospital any time they felt necessary or in case of any emergency.

Statistics

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (range) and compared with Student's t test, whereas categorical variables were expressed as proportions (%) and compared with the χ2 test. All the baseline factors were analyzed together between the groups dead versus alive, CLD versus ACLF and among patients with ACLF between those who survived <30 days versus >90 days by binary logistic regression to determine those predicting worse outcome. Two-sided p < 0.05 was considered significant. Area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curves with the best cutoff value for predicting mortality/worse disease outcome were computed for the prognostic scores. All statistics were calculated using SPSS version 13 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, MI, USA).

Results

A total of 575 cases with alcohol-related liver disease were seen in this period of which the data of 395 cases were finally analyzed. All the patients were males. The breakup is shown in Figure 1.

All the cases of alcoholic hepatitis had a bilirubin level of 4–8 mg/dL, 27 (33.7%) had deranged prothrombin time (difference compared to controls 3–7 s), 16 (20%) had a DF score >32 but all recovered completely with conservative treatment only, without the need of steroid within 1–3 months. None had decompensation till the last follow-up. Of the patients with ACLF, 35 (26.3%) had a prior history of decompensation with subsequent recovery and all were males of young age (mean 38.9 years). All patients who died consumed alcohol heavily, i.e., >85 g per day for >17 years, being significantly higher than the amount consumed by those alive. 305 (96.8%) drank daily among those who died compared to only 25 (31.3%) who were alive (p < 0.0001). Binge drinking was present in 65/133 (48.9%) of ACLF versus in 49/182 (26.9%) of cirrhosis patients (p < 0.0001) and 237/315 (75.2%) drank outside meal times (in many occasions on an empty stomach). Abdominal pain was present in 188 (47.5%), hepatomegaly in 269 (68.1%), and splenomegaly in 106 (26.8%), esophageal varices in 178 (45%), and portal hypertensive gastropathy in 218 (55.2%) patients. 75 (19%) presented with deranged liver function tests only, mostly belonging to the alcoholic hepatitis group. Gamma glutamyl transferase was elevated in all cases suggestive of active alcoholism.

In those who died, SGOT/SGPT was >2 in all ACLF (3–4 times normal in 32) and 1.5–2 in 155 (85.2%) cirrhotic patients at presentation. SGPT was normal (<40 IU/mL) in 100 (75.2%) ACLF and 132 (72.5%) cirrhotic patients. Bilirubin was elevated in all ACLF patients (mean 10.41 ± 5.12 [5.1–24.6] mg/dL) and in 147 (80.2%) cirrhotic patients (mean 3.09 ± 1.13 [1.2–4.8] mg/dL). In those who survived, SGOT/SGPT was 1–1.3 in 68 (85%, <1 in the remaining 15%) but SGPT was normal in only 10 (12.5%) and bilirubin was elevated in 20 (25%) (overall 0.8–3.5 mg/dL) with less deranged INR (<1.2). As all ACLF patients had ascites and/or sepsis, steroid was not administered to them. All deceased patients had low serum albumin levels at entry (also had clinical sarcopenia) that did not normalize with in-hospital treatment and they also did not follow the prescribed nutrition after discharge due to varying reasons of poverty, illiteracy, lack of family support or their addiction. Only 4/80 (5%) patients with alcoholic hepatitis had low albumin levels which normalized with recovery.

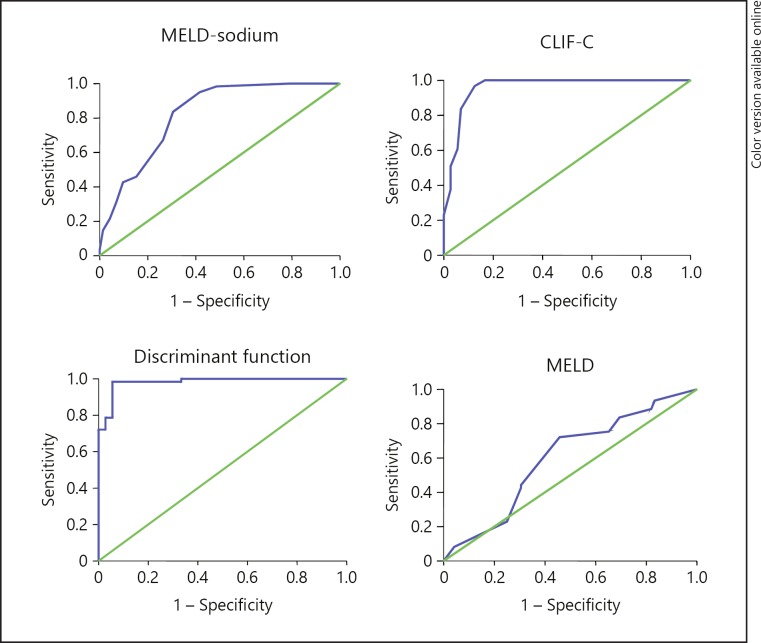

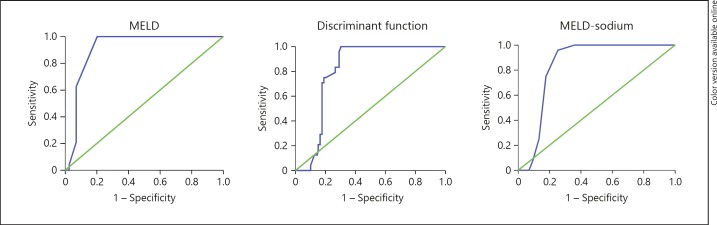

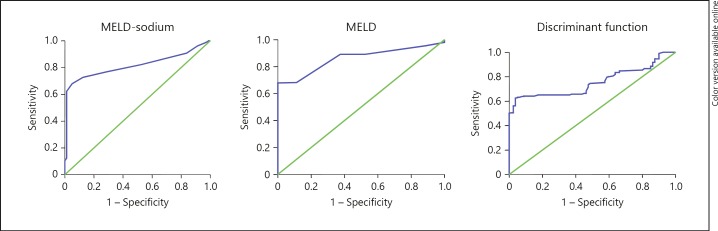

The baseline parameters of different groups of patients with univariate analysis of differences are shown in Tables 1, 2, 3 and factors significant on multivariate analysis are presented in Table 4. The AUROC values for prediction of mortality/worse outcome by different prognostic scores are listed in Table 5 and the curves are depicted in Figures 2, 3, 4. Between the groups age, DF, CTP, MELD and MELD-Na scores, the amount and duration of alcohol consumption were all significantly higher in more severe disease (dead vs. alive, ACLF vs. cirrhosis and <30-day vs. >90-day mortality groups of ACLF) but the type of alcohol consumed was not different between all these groups. Ascites and gastrointestinal bleed was similar between cirrhosis and ACLF groups. The number of organ failures including sepsis was higher in ACLF versus cirrhosis and in <30-day versus >90-day mortality groups of ACLF and it predicted mortality in both. Higher age and the amount of alcohol consumed predicted overall mortality and occurrence of cirrhosis. DF was the best overall predictor of severity and survival in alcohol-related liver disease, especially in cases of ACLF. A cutoff value of >56 strongly predicted early mortality in ACLF and a cutoff value of 42.35 predicted ACLF versus cirrhosis (i.e., such patients were more likely to have ACLF than cirrhosis only) with 91% sensitivity and specificity (AUROC 0.96 [0.94–0.98]). CLIF-C score fared slightly worse than DF but was still a very good predictor at a score >48. Though the MELD score predicted <6-month mortality in the cirrhotic group better than others, it did not perform well in all cirrhotic patients in predicting earlier mortality, e.g., in those with ACLF (acute hepatitis superimposed on cirrhosis where the highest survival was only 134 days) it had the lowest AUROC value (Table 5). An unrelated but interesting finding was the presence of chronic pancreatitis in 29 (7.3%) patients.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of all patients

| Item | Overall (n = 395) | Dead (n = 315, 79.7%) | Alive (n = 80, 20.3%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 38.94±10.19 (20–64) | 41.26±9.28 (32–64) | 27.50±4.98 (20–37) | <0.001 |

| DF | 39.59±15.66 (18.4–89.5) | 43.48±18.08 (20.2–89.5) | 32.72±6.21 (18.4–40.8) | <0.001 |

| <32 | 146 (37%) | 122 (38.7%) | 40 (50%) | 0.08 |

| 32–60 | 187 (47.3%) | 131 (41.6%) | 40 (50%) | 0.2 |

| 61–80 | 48 (12.1%) | 48 (15.3%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| >80 | 14 (3.6%) | 14 (4.4%) | 0 | 0.1 |

| CTP score | 8.31 ±1.8 5 (5–13) | 9.28±1.54 (7–13) | 6.50±0.84 (5–8) | <0.001 |

| <7 | 4 (1.1%) | 0 | 4 (5%) | <0.001 |

| 7–9 | 189 (47.8%) | 113 (35.9%) | 76 (95%) | <0.001 |

| >9 | 202 (51.1%) | 202 (64.1%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| MELD score | 13.55±5.13 (7–30) | 15.88±4.88 (8–30) | 8.95±0.95 (7–10) | <0.001 |

| <15 | 252 (63.8%) | 172 (54.6%) | 80 (100%) | <0.001 |

| 15–20 | 90 (22.8%) | 90 (28.6%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| >20 | 53 (13.4%) | 53 (16.8%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| MELD-Na score | 21.95±4.93 (10–34) | 23.02±4.86 (13–34) | 17.7±2.14 (10–25) | <0.001 |

| Amount of alcohol, mL/day | 78.20±19.46 (40–120) | 89.38±12.21 (80–120) | 56.18±7.93 (40–88) | <0.001 |

| Duration of alcohol consumption, years | 16.68±7.19 (5–32) | 19.83±6.50 (14–32) | 8.50±4.19 (5–20) | <0.001 |

| Type of alcohol | ||||

| Country | 153 (40.2%) | 121 (38.4%) | 32 (40%) | 0.9 |

| Mixed | 195 (49.4%) | 155 (49.2%) | 40 (50%) | 0.9 |

| IMFL | 47 (10.4%) | 39 (12.4%) | 8 (10%) | 0.7 |

| Presentation | ||||

| Jaundice | 380 (96.2%) | 315 (100%) | 65 (80.3%) | <0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 350 (88.6%) | 315 (100%) | 35 (43.8%) | <0.001 |

| Ascites | 299 (75.7%) | 291 (92.4%) | 8 (10 %, minimal) | <0.001 |

| GI bleed | 165 (41.8%) | 165 (52.4%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| HE | 107 (27.1%) | 107 (34.%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Renal dysfunction | 106 (26.8%) | 106 (33.7%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 199 (50.4%) | 181 (57.5%) | 18 (22.5%) | <0.001 |

| Infections | 65 (16.4%) | 65 (20.6%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Respiratory | 48 (12.2%) | 48 (15.2%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| SBP | 15 (3.8%) | 15 (4.8%) | 0 | 0.09 |

| Urine | 2 (0.4%) | 2 (0.6 %) | 0 | 0.9 |

| SGOT (5–40 IU/L) | 91.87±16.36 (46–155) | 95.84±17.12 (46–155) | 81.21±7.52 (58–108) | <0.001 |

| SGPT (5–40 IU/L) | 54.37±10.64 (25–88) | 40.34±5.64 (25–58) | 61.18±7.98 (36–88) | <0.001 |

| GGT (9–48 IU/L) | 118.3±21.8 (85–166) | 114.7±17.4 (90–166) | 121.4±18.6 (85–164) | 0.002 |

| INR | 1.5±0.3 (1–2.1) | 1.7±0.3 (1.3–2.1) | 1.1±0.1 (1–1.3) | <0.001 |

| Albumin, mg/dL | 2.5±0.6 (1.6–4.5) | 2.16±0.2 (1.6–2.4) | 3.1±0.5 (2.3–4.5) | <0.001 |

| Follow - up, years | 1–3 | up to 2 | 1–2 | |

HE, hepatic encephalopathy; DF, discriminant function; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; MELD-Na, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-sodium; INR, international normalized ratio; SGOT, serum glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase; SGPT, serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase; GGT, gamma glutamyl transferase; GI, gastrointestinal; IMFL, India-made foreign liquor.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of dead patients

| Item | Dead (n = 315) | ACLF (n = 133, 42.2%) | CLD (n = 182, 57.8%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 41.26±9.28 (32–64) | 42.46±6.49 (34–64) | 46.43±6.21 (32–60) | <0.001 |

| DF score | 43.48±18.08 (20.2–89.5) | 58.79±15.23 (36–89.1) | 32.3±0.95 (20.2–48.4) | <0.001 |

| <32 | 122 (38.7%) | 0 | 122 (67%) | <0.001 |

| 32–60 | 131 (41.6%) | 71 (53.4%) | 60 (33%) [>40 = 2] | <0.001 |

| 61–80 | 48 (15.3%) | 48 (36.1%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| >80 | 14 (4.4%) | 14 (10.5%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| CTP score | 9.28±1.54 (7–13) | 10.18±1.49 (7–13) | 8.54±1.10 (7–11) | <0.001 |

| <7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7–9 | 113 (35.9%) | 16 (12%) | 97 (53.3%) | <0.001 |

| >9 | 202 (64.1%) | 117 (88%) | 85 (46.7%) | <0.001 |

| MELD score | 15.88±4.88 (8–30) | 19.11 ±5.32 (10–30) | 13.52±2.70 (8–22) | <0.001 |

| <15 | 172 (54.6%) | 32 (24.1%) | 140 (76.9%) | <0.001 |

| 15–20 | 90 (28.6%) | 52 (39.1%) | 38 (20.9%) | <0.001 |

| >20 | 53 (16.8%) | 49 (36.8%) | 4 (2.2%) | <0.001 |

| MELD–Na score | 23.02±4.86 (13–34) | 27.19±3.17 (22–34) | 19.97±3.4 (13–28) | <0.001 |

| Amount of alcohol, mL/day Duration of alcohol consumption, | 89.38±12.21 (80–120) | 93.19±12.48 (85–120) | 86.6±11.25 (80–110) | <0.001 |

| years | 19.83±6.5 0 (14–32) | 19.71±4.06 (14–28) | 21.61 ±4.16 (15–32) | <0.001 |

| Survival, days | 205.33±161.77 (5–602) | 51.08±41.23 (5–134) | 318.05±117.90 (114–602) | <0.001 |

| <30 | 61 (19.4%) | 61 (45.9%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| 30–90 | 40 (12.7%) | 40 (30.1%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| >90 | 214 (67.9%) | 32 (24%) | 182 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Type of alcohol | ||||

| Country | 121 (38.4%) | 44 (33.1%) | 77 (42.3%) | 0.1 |

| Mixed | 155 (49.2%) | 77 (57.9%) | 78 (42.9%) | 0.07 |

| IMFL | 39 (12.4%) | 12 (9%) | 27 (14.8%) | 0.16 |

| Presentation | ||||

| Jaundice | 315 (100%) | 133 (100%) | 147 (80.8%) | <0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 315 (100%) | 133 (100%) | 160 (87.9%) | <0.001 |

| Ascites | 291 (92.4%) | 124 (93.2%) | 187 (91.8%) | 0.9 |

| GI bleed | 165 (52.4%) | 69 (51.9%) | 96 (52.7%) | 0.9 |

| Renal dysfunction | 106 (33.7%) | 89 (66.9%) | 17 (9.3%) | <0.001 |

| HE | 107 (34.%) | 73 (54.9%) | 46 (25.3%) | <0.001 |

| Circulatory dysfunction | 50 (15.9%) | 35 (26.3%) | 15 (8.2%) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 181 (57.5%) | 101 (75.9%) | 80 (44%) | <0.001 |

| Infections | 65 (20.6%) | 14 (10.5%) | 51 (28%) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory | 48 (15.2%) | 4 (3%) | 44 (24.2%) | <0.001 |

| SBP | 15 (4.8%) | 10 (7.5 %) | 5 (2.7%) | 0.08 |

| Urine | 2 (0.6 %) | 0 | 2 (1.1%) | 0.6 |

| Number of organ failures | 0 = 104 | 0 = 0 | 0 =104 (57.2%) | <0.001 |

| 1 = 47 | 1 = 0 | 1= 47 (25.8%) | <0.001 | |

| 2 = 48 | 2 = 27 (20.3%) | 2= 21 (11.5%) | 0.04 | |

| 3 = 50 | 3 = 40 (30.1%) | 3= 10 (5.5%) | <0.001 | |

| 4 = 48 | 4 = 48 (36.1%) | 4 = 0 | <0.001 | |

| 5 = 18 | 5 = 18 (13.5%) | 5 = 0 | <0.001 | |

| SGOT, IU/mL | 95.8±17.12 (46–155) | 97.2±16.63 (48–155) | 66.61±7.14 (46–94) | <0.001 |

| SGPT, IU/mL | 40.34±5.64 (25–58) | 34.12±3.65 (25–47) | 41.56±4.34 (27–58) | <0.001 |

| GGT, IU/L | 114.7±17.4 (90–166) | 118.2±14.8 (90–166) | 107.6±12.8 (90–148) | <0.001 |

| Albumin, mg/dL | 2.16±0.2 (1.6–2.4) | 2.1±0.2 (2–2.4) | 2±0.2 (1.6–2.3) | <0.001 |

| INR | 1.7±0.3 (1.3–2.1) | 1.8±0.3 (1.3–2.1) | 1.4±0.1 (1.3–1.7) | <0.001 |

HE, hepatic encephalopathy; DF, discriminant function; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; MELD-Na, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-sodium; INR, international normalized ratio; SGOT, serum glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase; SGPT, serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase; GGT, gamma glutamyl transferase; GI, gastrointestinal; IMFL, India-made foreign liquor.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of ACLF patients according to survival

| Item | <30 days (n = 61, 45.9%) survival | >90 days (n = 32, 24%) survival | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 45.34±7.79 (37–64) | 39.94±4.07 (34–47) | <0.001 | |

| DF score | 72.81±9.08 (47.8–89.1) | 46.38±7.91 (36–67.4) | <0.001 | |

| <32 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 32–60 | 3 (4.9%) | 30 (93.7%) | <0.001 | |

| 61–80 | 44 (72.1%) | 2 (6.3%) | <0.001 | |

| >80 | 14 (23%) | 0 | <0.001 | |

| CTP score | 10.98±1.5 (8–13) | 9.47±1.16 (7–11) | <0.001 | |

| <7 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 7–9 | 3 (4.9%) | 8 (25%) | <0.001 | |

| >9 | 58 (95.1%) | 24 (75%) | <0.001 | |

| MELD score | 23.66±3.02 (20–30) | 14.91±3.78 (10–20) | <0.001 | |

| <15 | 0 | 16 (50%) | <0.001 | |

| 15–20 | 11 (65.6%) | 16 (50%) | <0.001 | |

| >20 | 21 (34.4%) | 0 | <0.001 | |

| MELD-Na score | 29.13±2.68 (24–34) | 25.41±2.7 (22–32) | <0.001 | |

| Amount of alcohol, mL/day | 97.45±13.22 (80–120) | 89.34±11.61 (80–120) | 0.004 | |

| Duration of alcohol consumption, years | 21.29±4.29 (17–28) | 17.97±3.31 (14–25) | <0.001 | |

| Survival, days | 11.66±5.59 (5–28) | 109.22±10.74 (91–134) | <0.001 | |

| Type of alcohol | ||||

| Country | 16 (26.2%) | 12 (37.5%) | 0.3 | |

| Mixed | 41 (67.2%) | 19 (59.4%) | 0.6 | |

| IMFL | 4 (6.6%) | 1 (3.1%) | 0.8 | |

| Presentation | ||||

| Jaundice | 61 (100%) | 32 (100%) | 1 | |

| Coagulopathy | 61 (100%) | 32 (100%) | 1 | |

| Ascites | 61 (100%) | 28 (87.5%) | 0.02 | |

| GI bleed | 34 (55.7%) | 9 (28.1%) | 0.02 | |

| Renal dysfunction | 48 (78.7%) | 10 (31.3 %) | <0.001 | |

| HE | 46 (75.4%) | 9 (28.1%) | <0.001 | |

| Circulatory dysfunction | 26 (42.6%) | 4 (12.5%) | <0.001 | |

| Sepsis | 61 (100%) | 13 (40.6%) | <0.001 | |

| Infections | 14 (23%) | 0 | 0.008 | |

| Respiratory | 4 (6.6%) | 0 | 0.3 | |

| SBP | 10 (16.4%) | 0 | 0.03 | |

| Number of organ failures | 2 = 0 | 2 = 24 (75%) | <0.001 | |

| 3 = 16 (26.2%) | 3 = 8 (25%) | 0.9 | ||

| 4 = 28 (45.9%) | 0 | <0.001 | ||

| 5 = 17 (27.9%) | 0 | 0.002 | ||

| SGOT, IU/mL | 98.61±17.31 (48–155) | 95.25±12.04 (56–132) | 0.007 | |

| SGPT, IU/mL | 31.72±2.72 (25–40) | 37.43±2.63 (31–47) | <0.001 | |

| GGT, IU/L | 120.2±12.8 (90–166) | 117.3±15.1 (95–160) | 0.33 | |

| Albumin, mg/dL | 2.1±0.1 (2–2.3) | 2.2±0.1 (2–2.4) | <0.001 | |

| INR | 1.7±0.1 (1.5–2.1) | 1.5±0.1 (1.3–1.8) | <0.001 | |

HE, hepatic encephalopathy; DF, discriminant function; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; MELD, Model for End-Stage liver disease; MELD-Na, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-sodium; INR, international normalized ratio; SGOT, serum glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase; SGPT, serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase; GGT, gamma glutamyl transferase; GI, gastrointestinal; IMFL, India-made foreign liquor.

Table 4.

Factors significant on multivariate analysis between groups

| Dead versus alive | Cirrhosis versus ACLF mortality | <30-day versus > 90-day mortality in ACLF |

|---|---|---|

| Age 1.15 (1.01–1.31), discriminant function 1.32 (1.14–1.56), amount of alcohol 1.04 (1.002–1.09) | Age 1.38 (1.11–1.71), amount of alcohol 1.39 (1.08–1.8), hepatic encephalopathy 0.43 (0.12–0.63), renal dysfunction 0.1 (0.01–0.31), discriminant function 0.43 (0.23–0.70), sepsis 0.02 (0.001–0.46) | Discriminant function 1.35 (1.18–1.54), number of organ failures 1.97 (1.23–3.12) |

ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure.

Table 5.

AUROC (confidence intervals) with best cutoff scores (sensitivity, specificity)

| Item | DF score | CLIF-C score | MELD score | MELD-Na score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACLF <30-day | 0.98 (0.96–1.0) | 0.96 (0.92–0.99) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | 0.82 (0.75–0.89) |

| mortality | 56.75 (98.4%, 94.4%) | 48.5 (96.7%, 87.5%) | 19 (72%, 54%)* | 26.5 (83.6%, 70%) |

| Cirrhosis <6-month | 0.82 (0.78–0.86) | 0.90 (0.86–0.93) | 0.84 (0.78–0.89) | |

| mortality | 33.25 (100%, 70%) | 15 (100%, 80%) | 21.5 (96%, 75%) | |

| Overall mortality | 0.79 (0.74–0.85) | 0.84 (0.8–0.9) | 0.82 (0.77–0.86) | |

| 36.3 (73%, 85%) | 14.9 (68%, 100%) | 18.5 (77%, 71%) |

p = 0.05, all others are significant at p < 0.05. ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; DF, discriminant function; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; MELD-Na, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-sodium; CLIF-C, European Foundation for the study of chronic liver failure consortium.

Fig. 2.

ROC curves for ACLF <30-day mortality for different scores. ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; MELD-Na, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-sodium; CLIF-C, European Foundation for the study of chronic liver failure consortium.

Fig. 3.

ROC curves for cirrhosis <6-month mortality for different scores. MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; MELD-Na, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-sodium.

Fig. 4.

ROC curves for overall mortality for different scores. MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; MELD-Na, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-sodium.

Most patients practiced abstinence after they had been hospitalized except 24/182 (13.2%) patients with cirrhosis who continued to imbibe alcohol after discharge and died within 3 months. Those with alcoholic hepatitis recovered completely but in the others with ACLF (who survived >90 days) and cirrhosis, liver function tests and prothrombin time improved but did not completely normalize and they had prolonged survival compared to those who continued drinking. However, liver function tests either deteriorated or remained static at admission levels in those patients of ACLF who survived <30 days even with abstinence.

Discussion

This study shows the serious nature of alcohol-related cirrhosis and ACLF with high short-term mortality after presentation in spite of abstinence. It has identifiable but mostly irreversible factors that predict mortality. Continuous abstinence is mandatory and may lead to complete recovery in the early milder stages, especially cases of alcoholic hepatitis (without cirrhosis). Unfortunately, most patients present late when salvage is unlikely without liver transplantation. In a subset of patients drinking continues in spite of having a quite advanced disease. Causes include dependence, lack of family and social support, increasing stress at workplace and home without time for adequate relaxation. Our study also shows that the prognosis worsens with an increasing amount and duration of drinking but is unrelated to the type of alcohol consumed, similar to other recent studies [7, 21, 22]. Thus, clinical interventions should focus on early detection by screening and timely treatment in the initial reversible stages. Our finding becomes further important in light of the recently published data on the disease burden in different states of India [23] which showed that alcohol-related disorders has increased more in this state in the period 1990–2016 (compared to other states) such that it is now the 9th contributor to DALY number compared to the 11th in 1990 with a rise of 86%.

ACLF is an important cause of early mortality in cirrhotics, and this needs early recognition and intervention before the systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis, and multiorgan failure set in. Compared to the other causes of cirrhosis and precipitants of ACLF, alcohol as cause and precipitant portends high early mortality (46% die within a month), as has been shown in other studies [7, 13, 14, 15]. Binge drinking results in more ACLF. A higher DF score (which includes serum bilirubin and prothrombin time) and a higher number of organ failures (including sepsis) [8, 13, 16, 24] are the strongest predictors of early mortality in alcohol-related ACLF and these are unlikely to respond to supportive medical care alone. Traditionally, the DF score has been used for prognosticating alcoholic hepatitis and a score ≥32 on admission predicts 1-month mortality of 30–50% in the absence of specific pharmacotherapy. The main drawback of DF is its interpretation using a threshold of 32 (which has converted it essentially into a categorical way of classification though it is a continuous measure) exceeding which increases the risk of dying but in an unspecified measure [25]. We therefore used continuous incremental values to observe its effect on outcome.

From our study, DF appears to be the best predictor of severity of ACLF (compared to other scores) as its increasing values are associated with more severe disease and earlier mortality. A DF score >56 predicted early mortality and >42 predicted the presence of ACLF so these groups may need aggressive interventions including liver transplant. A DF score >32 is currently used as threshold for starting steroid or pentoxifylline therapy. However, >65% cases of alcoholic hepatitis (with a DF score >32) may turn out to be ACLF with poor response to steroid [17]. We did not use steroid in our patients of ACLF even if the DF score was >32 as all had ascites and/or sepsis and were at high risk of clinical worsening. Though not validated for the prognostication of ACLF, a DF score >32 was present in all our patients with ACLF and in 60 (32.8%) patients with cirrhosis (overall 193 [61.3%] patients who died). Thus, it prognosticated ACLF (with the component of alcoholic hepatitis) much better than cirrhosis as is evidenced from the AUROC values as well. Recent studies have found the DF to be a good predictor of severity of ACLF though slightly less than the CLIF-SOFA score [26]. We compared the recently upgraded version of CLIF-SOFA, i.e., the CLIF-C score with the DF score in our cohort and found similar results though DF had a slight edge in our results. However, the cutoff value of CLIF-C score for predicting mortality was much lower than in European cohorts. MELD-Na performed better than MELD score in the ACLF group.

The MELD score has also been proposed to stratify alcoholic hepatitis patients and its diagnostic abilities have been tested against the DF and CTP score. Optimal cutoff points are not clearly established, suggested ones being as variable as 11, 18, 19, and 21. We used a cutoff score of 20 for severe disease as suggested recently [27] and a value <15 as mild disease. A baseline score >15 was present in 45.4% who ultimately died and in 75.9% of ACLF patients (including 100% ACLF patients who survived <30 days), though its performance was the worst in ACLF patients as previously reported [28]. It also predicted <6-month mortality in the cirrhotic group and better than the other scores, though not significant on multivariate analysis in either group unlike the DF score. The performance of MELD-Na was mostly parallel to the MELD score for overall mortality.

An important observation is the SGOT/SGPT ratio of 2–4 with normal SGPT in 73.4% cases who died. Such a finding should raise strong suspicion of alcohol-related cirrhosis and a higher SGOT/SGPT ratio forfends ACLF if there are other abnormalities in the liver function test (like high bilirubin, low albumin) and deranged prothrombin time. This results from the inability of cirrhosed liver to produce SGPT in addition to the vitamin B1 deficiency induced by alcohol which causes decreased SGOT metabolism. On the other hand, a lower SGOT/SGPT ratio with high SGPT might indicate early liver injury by alcohol or another additional cause.

Most patients die in their prime of life when they are socioeconomically most productive, and this negatively affects the socioeconomic status of the patient's family and of the country due to loss of workforce. Apart from cirrhosis, alcohol is related to psychiatric morbidity, accidents, violence and sickness absenteeism, which furthers the negative impact. Ironically, it is one of the few absolutely preventable diseases and time has come for taking stern steps to curb this increasing and formidable menace. In addition to early detection and treatment, interventions by policy makers to decrease the consumption of alcohol may include increasing the cost of alcohol (including increase in taxation) and reduction of availability (e.g., areawise distribution only through few specific outlets in limited quantities), prohibition of alcohol advertisement, glorification and marketing campaigns, regulation of the environment in which alcohol is marketed and consumed (e.g., restricting function time of bars at night, prohibition of sale through small shops) and formulation of strong legislation (e.g., action against drunk driving, punishment for work attendance in a drunk state, stringent purchase laws and government monopoly on alcohol). Health education may include advice on alcohol consumption for individuals at risk for alcoholism, school-based and public education campaigns on the short- and long-term bad effects of alcohol drinking. Steps should also be taken to increase the treatment of alcohol-related disorders including psychiatric counselling.

Conclusion

Alcohol-related liver disease is serious with high short-term mortality after presentation. It has early identifiable but mostly irreversible factors. DF value can be used to identify patients at higher risk of mortality as also separate patients of predominant ACLF from cirrhosis. Urgent measures need to be taken to curb this rising menace.

Statement of Ethics

The study was approved by the hospital ethics committee and all patients (or their relatives) consented in writing to be included in the study.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Financial Sources

No financial sources to declare.

References

- 1.WHO Global status report on alcohol and health. September. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kröner PT, Mankal PK, Dalapathi V, Shroff K, Abed J, Kotler DP. Alcohol-Attributable Fraction in Liver Disease: Does GDP Per Capita Matter? Ann Glob Health. 2015 Sep-Oct;81((5)):711–7. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dandona L, Dandona R, Kumar GA, Shukla DK, Paul VK, Balakrishnan K, et al. India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Collaborators Nations within a nation: variations in epidemiological transition across the states of India, 1990-2016 in the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2017 Dec;390((10111)):2437–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32804-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maharshi S, Sharma BC, Srivastava S. Malnutrition in cirrhosis increases morbidity and mortality. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Oct;30((10)):1507–13. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain J, Singh R, Banait S, Verma N, Waghmare S. Magnitude of peripheral neuropathy in cirrhosis of liver patients from central rural India. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2014 Oct;17((4)):409–15. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.144012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamza RE, Villyoth MP, Peter G, Joseph D, Govindaraju C, Tank DC, et al. Risk factors of cellulitis in cirrhosis and antibiotic prophylaxis in preventing recurrence. Ann Gastroenterol. 2014;27((4)):374–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhattacharyya M, Barman NN, Goswami B. Survey of alcohol-related cirrhosis at a tertiary care center in North East India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2016 May;35((3)):167–72. doi: 10.1007/s12664-016-0651-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agrawal S, Duseja A, Gupta T, Dhiman RK, Chawla Y. Simple organ failure count versus CANONIC grading system for predicting mortality in acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Mar;30((3)):575–81. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choudhary NS, Saigal S, Saraf N, Mohanka R, Rastogi A, Goja S, et al. Sarcopenic obesity with metabolic syndrome: a newly recognized entity following living donor liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2015 Mar;29((3)):211–5. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagaraja R, Mehta N, Kumaran V, Varma V, Kapoor S, Nundy S. Readmission after living donor liver transplantation: predictors, causes, and outcomes. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2014 Jul;33((4)):369–74. doi: 10.1007/s12664-014-0462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prasad R. Alcohol use on the rise in India. Lancet. 2009 Jan;373((9657)):17–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61939-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray G. Trends of chronic liver disease in a tertiary care referral hospital in Eastern India. Indian J Public Health. 2014 Jul-Sep;58((3)):186–94. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.138630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choudhary NS, Kumar N, Saigal S, Rai R, Saraf N, Soin AS. Liver Transplantation for Alcohol-Related Liver Disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2016 Mar;6((1)):47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shalimar., Saraswat V, Singh SP, Duseja A, Shukla A, Eapen CE, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure in India: The Indian National Association for Study of the Liver consortium experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Oct;31((10)):1742–1749. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pati GK, Singh A, Misra B, Misra D, Das HS, Panda C, et al. Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure (ACLF) in Coastal Eastern India: “A Single-Center Experience”. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2016 Mar;6((1)):26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amarapurkar D, Dharod MV, Chandnani M, Baijal R, Kumar P, Jain M, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: a prospective study to determine the clinical profile, outcome, and factors predicting mortality. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2015 May;34((3)):216–24. doi: 10.1007/s12664-015-0574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sersté T, Cornillie A, Njimi H, Pavesi M, Arroyo V, Putignano A, et al. The prognostic value of acute-on-chronic liver failure during the course of severe alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2018 Aug;69((2)):318–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarin SK, Kedarisetty CK, Abbas Z, Amarapurkar D, Bihari C, Chan AC, et al. APASL ACLF Working Party Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) 2014. Hepatol Int. 2014 Oct;8((4)):453–71. doi: 10.1007/s12072-014-9580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association . 5th Edition: DSM-5 2017. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jalan R, Saliba F, Pavesi M, Amoros A, Moreau R, Ginès P, et al. CANONIC study investigators of the EASL-CLIF Consortium Development and validation of a prognostic score to predict mortality in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2014 Nov;61((5)):1038–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nand N, Malhotra P, Dhoot DK. Clinical Profile of Alcoholic Liver Disease in a Tertiary Care Centre and its Correlation with Type, Amount and Duration of Alcohol Consumption. J Assoc Physicians India. 2015 Jun;63((6)):14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray S, Khanra D, Sonthalia N, Kundu S, Biswas K, Talukdar A, et al. Clinico-biochemical correlation to histological findings in alcoholic liver disease: a single centre study from eastern India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014 Oct;8((10)):MC01–05. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8763.4968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Indian Council of Medical Research, Public Health Foundation of India, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation . New Delhi, India: ICMR, PHFI and IHME; 2017. India: Health of the Nation's States - The India State-level Disease Burden Initiative. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maiwall R, Chandel SS, Wani Z, Kumar S, Sarin SK. SIRS at admission is a predictor of AKI development and mortality in hospitalized patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016 Mar;61((3)):920–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3921-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ, Practice Guideline Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010 Jan;51((1)):307–28. doi: 10.1002/hep.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim HY, Kim CW, Kim TY, Song DS, Sinn DH, Yoon EL, et al. Korean Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure Study Group Assessment of scoring systems for acute-on-chronic liver failure at predicting short-term mortality in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 Nov;22((41)):9205–13. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i41.9205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singal AK, Bataller R, Ahn J, Kamath PS, Shah VH. ACG Clinical Guideline: Alcoholic Liver Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Feb;113((2)):175–94. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engelmann C, Thomsen KL, Zakeri N, Sheikh M, Agarwal B, Jalan R, et al. Validation of CLIF-C ACLF score to define a threshold for futility of intensive care support for patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Crit Care. 2018 Oct;22((1)):254–61. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]