Abstract

Background

Prostate cancer (PC) has the highest prevalence in men and accounts for a high rate of neoplasia-related death. Doxorubicin (DOX) is one of the most widely used anti-neoplastic drugs for prostate cancer among others. However, it has low specificity and many side effects and affects normal cells. More recently, there have been newly developed drug delivery tools which are graphene or graphene-based, used to increase the specificity of the delivered drug molecules. The graphene derivatives possess both π-π stacking and increased hydrophobicity, factors that increase the likelihood of drug delivery. Despite this, the hydrophilicity of graphene remains problematic, as it induced problems with stability. For this reason, the use of a chitosan coating remains one way to modify the surface features of graphene.

Method

In this investigation, a hybrid nanoparticle that consisted of a DOX-loaded reduced graphene oxide that is stabilized with chitosan (rGOD-HNP) was developed.

Result

The newly developed rGOD-HNP demonstrated high biocompatibility and efficiency in entrapping DOX (~65%) and releasing it in a controlled manner (~50% release in 48 h). Furthermore, it was also demonstrated that rGOD-HNP can intracellularly deliver DOX and more specifically in PC-3 prostate cancer cells.

Conclusion

This delivery tool offers a feasible and viable method to deliver DOX photo-thermally in the treatment of prostate cancer.

Keywords: graphene, photothermal, chitosan, hybrid nanoparticles, HNP, prostate cancer

Introduction

In the U.S., Canada, and Western Europe, prostate cancer (PC) accounts for the highest incidence of cancer among men and is the 3rd highest cause of neoplasia-related death.1 In fact, current treatment options include drug suppression of androgens using hormonal- or herbal-based drugs, alongside intravenous or oral drug delivery.2 However, these treatment methods are severely restricted in efficacy and specificity due to adverse side effects, short duration of effects. Current research methods in prostate cancer are aimed at improving the targeted delivery of therapeutic drugs, with the goal of reducing the side effects and improving drug specificity.3–5

In terms of improving therapeutic efficacy via targeted drug delivery, graphene and their derived drug delivery strategies are current innovations that can be used to achieve such goals.6 Derivatives of graphene demonstrate unique properties that predispose them to be optimally used as a targeted drug delivery tool, including their increased surface/volume ratio, and high loading ability.7 This high loading ability is thought to be due to the high degree of π-π ring stacking and interactions of hydrophobicity. Despite these advantages, the hydrophilic dispersion of graphene poses a stability problem which must be addressed if graphene is to be used as a drug delivery tool.8

In the current scenario, nanoparticles have made revolutionary changes in the field of drug delivery owing to their excellent properties9–11. Their nano-size architect, tailorable surface and capability to enhance the pharmacological effects of the loaded bio actives few of them.12,13 From last two decades, nanoparticles science has been developed to overcome the limitations of traditional delivery systems or materials as well as the ever increasing demand for the new materials in nanotechnology, biotechnology, biomedicine, and others.14,15 Owning to their high stability, biodegradability, low toxicity, and biocompatibility, biopolymer-based nanomaterials hold great promise for various biomedical applications.16,17

To increase the stability of graphene, chitosan was employed as a novel cationic polysaccharide that possesses excellent stabilizing properties. The use of chitosan coating provides an effective way to alter the surface modalities of graphene and improve their applications in drug targeting. Furthermore, the biological properties of chitosan, such as easy degradability, compatibility, and non-toxicity have contributed to its prevalent use in the last few years.18,19 Chitosan’s structure contains several amino acids, giving it a positive charge on its surface, and the ability to crosslink with molecules like tripolyphosphate (TPP). Due to this feature, chitosan cam also self-assemble with TPP using ionic gelation due to its negative charge.20

Doxorubicin (DOX) is a widely used anti-neoplastic for the treatment of a range of cancers including prostate cancer. Its mechanism of action is by decreasing the efficacy of topoisomerase in cells, which damages the structure of DNA.21 However, this mechanism acts in both cancer and non-cancer cells, contributing to its low specificity. Many researchers have worked on optimizing a DOX-loaded delivery system, which has been shown to improve preclinical efficacy and decrease the side-effects. As such, DOX was selected in this research, considering it is a widely used anti-neoplastic used in the treatment of cancer.

A suitable nanocarrier system is required to effectively deliver and localize drug therapy at the site of desire. In this study, chitosan-based hybrid nanoparticle (HNP) of DOX-loaded reduced form of graphene oxide (rGO) was developed and optimized as a novel nanocarrier system. Also, rGO was used in our studies as it has not only a high degree of drug loading but also had a high photothermal efficacy. Furthermore, HNP was stabilized with chitosan due to its low molecular weight and increased targeting ability.

Materials

Graphite flakes were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, MO, USA (lot #MKVZ2867). Chitosan was purchased from TCI America (lot # C0831; CAS # 9012-76-4; Viscosity# 200–600 mPas, 0.5% w/v in 0.5% v/v Acetic Acid at 20 °C; Cambridge, MA, U.S.A. Tripolyphosphate (TPP) was purchased from Strem Chemicals (Newburyport, MA, USA). Dialysis membrane (Spectra/Por® 300 kDa MWCO), the membrane filter (Millex pore size 0.45 μm), were purchased from Fisher Scientific UK Ltd. (Loughborough, UK). Corning Transwell® polycarbonate membrane inserts (pore size 3.0 μm, membrane diameter 12 mm), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM was purchased from Mediatech Inc. (Herndon, VA, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Gibco BRL (Grand Island, NY, USA). PC-3 cells (National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India

Preparation of GO and rGo core

To prepare GO, graphite flakes were used as the base, made some modifications to the Hummer’s.22 Briefly, 1 g of graphite flakes dissolved in 46 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid for 15 min and 1 g of NaNO3 was added into it. The ice bath was used to control the reaction. This reaction was stirred for 30 min and 6 g KMnO4 was then gradually added to terminate the reaction. Afterward, the reaction mixture containing KMnO4 was placed in a water bath at 35 °C and stirred for 1 h at 400 g. Subsequently, 92 mL of deionized water was gradually added to the mixture while the temperature was kept below 100 °C using an ice bath. The flask was then placed into an oil bath at 100 °C, and the reaction was maintained at this temperature for 15 min. The mixture was further treated with 150 mL deionized water and 5 mL H2O2 solution (30%) to obtain a bright yellow dispersion. The color change from black to bright yellow is indicative of the formation of GO. Afterward, GO was washed repeatedly with deionized water until the supernatant gives the neutral pH (indicative of the removal of acid traces) and treated by ultrasonic for 30 min to obtain rGO solution. Finally, the rGO solution was freeze-dried for use in further experiments.

Preparation of DOX-loaded rGO hybrid nanoparticle (rGOD-hNP)

DOX was loaded into rGO using simple incubation for 24 h to elicit loading.23 Then the rGOD-NPs were coated using 0.1 % w/v chitosan using the solvent gelation technique and stabilized the formed hybrid NPs using TPP (0.125% w/v) to produce TPP stabilized rGOD-HNPs. Finally, these hybrid NPs stabilized using TPP were collected by centrifugation (18,000 g; 35 min) and lyophilized using 2 % w/v lactose monohydrate as a cryo-protectant. The lyophilized powder was used for further experiments.

Determination of particle size, and zeta potential measurements

The particle size and zeta potential of prepared Go, rGO, rGOD and rGOD-HNP were measured using dynamic light scattering. Electrophoretic mobility was measured using a zetasizer nano as described previously by our group.24 For the evaluation of size and polydispersity, prepared formulations were suitably diluted in water. All measurements were recorded in triplicate.

Percent entrapment efficiency (% EE) measurement

The percent EE was measured by employing the ultracentrifugation technique.25 The formulation rGOD-HNP (equivalent to 1 mg/mL of DOX) was centrifuged at 12,000 g and the supernatant was collected. The collected supernatant was subjected to UV spectrophotometric analysis (Shimadzu, Columbia, MD, USA) to determine the concentration of unloaded DOX at (λmax 308 nm. The % EE was determined by using Equation 1).

Where, X1= Total amount of DOX (mg), and X2= Free DOX in mg determined after ultracentrifugation.

In vitro drug release study

The in vitro release of DOX from the developed formulations was carried out in the physiological pH range using phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) by employing a dialysis tube diffusion technique.26 Briefly, the plain DOX or rGOD-HNP dispersed in PBS pH 7.4 media and placed inside a dialysis membrane bag with a molecular weight cutoff of 300 kDa (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) at an equimolar DOX concentration. The dialysis bags were placed in 50 mL of pH 7.4 PBS release medium and maintained at 37±1 °C with continuous stirring at 400 rpm. Followed by this, at predetermined intervals of time of 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, and 48 hrs, 0.5 mL of release medium was aliquoted and estimated for DOX concentration employing UV visible spectrophotometer (λmax: 480 nm). Immediately after sampling, the release media was replenished with the same volume of fresh medium to maintain an experimental sink condition during the investigation of drug release. The DOX in vitro release contour was determined by plotting a grid between time (hr) vs. cumulative percent release (%) for plain DOX and rGOD-HNP. The obtained data was also applied to mathematical models to investigate the release mechanism of DOX from the formulations by fitting it into the zero order, first order, Higuchi square root, Korsmeyer-Peppas and, Higuchi kinetics models. The experimentations were done in replicates of three and the results are presented as an average of obtained results (Mean ± S.D; n=3).

NIR laser-mediated photothermal effect

Apart from nanocarrier properties, the most important use of rGOD-NP is to produce heat upon irradiation with NIR light.27 To demonstrate the photothermal efficiency of developed formulation NIR laser diode was used. Briefly, 1 mg/mL aqueous dispersion of rGOD-NP was placed in a quartz cuvette that is transparent to NIR. This dispersion was then irradiated with NIR 808 nm for the different time periods between 0–200 sec, and measurements were noted with respect to an increment of temperature. The experiment was carried out in triplicate.

Blood compatibility test

To evaluate the blood compatibility with the developed formulation, blood from the entire mouse was collected in heparinized tubes and centrifuged at 3500 g for 10 min to separate the RBCs from the blood. The collected RBCs were washed (normal saline 0.9 %w/v) and re-suspended in normal saline to make 5%v/v suspension. To prepare a positive control, we mixed 0.5 mL Triton X-100 (10%v/v) with 4.5 mL of RBCs.28 Similarly, to prepare negative control, we mixed RBCs with normal saline instead of Triton-X-100. The formulations equivalent to 1 mg/mL DOX were added to the 5% RBC suspension and kept aside for 2 hr with gentle shaking followed by centrifugation at 3500 g for 20 min. The % hemolysis was measured by collecting supernatants which were analyzed using a UV spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) at 540 nm. The degree of hemolysis was calculated using Equation 2.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cell viability experiment was conducted on PC-3 cells to check the cellular toxicity of the developed formulation. Briefly, the PC-3 cells were grown in DMEM medium supplemented with 10%v/v FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin.29 The PC-3 cells in growth phase were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 1×104 cells/well. The medium was then replaced with fresh medium containing plain DOX, plain rGO, laser irradiation rGO, rGOD-NP, laser irradiation rGOD-HNP (DOX at a concentration equivalent to 1 mg/mL). Finally, the medium was spiked and 100 μl DMSO and cell viability were recorded by analyzing absorbance at 575 nm on a UV-plate reader (MultiscanGo, Thermo scientific, USA). Relative cell viability was calculated by the formula mentioned represented in Equation 3.

Where A sample, Blank, A negative control represent the absorbance of samples, blank, and negative control, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate and the data were expressed as the mean ± S.D. Statistical analysis was calculated via one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons. Post-test and two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test to match were done using GraphPad Prism 6.01™ software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, California). A probability level of p<0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001 were used to indicate significant, more significant and highly significant, while non-significant is p>0.05.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of GO and rGOD-hNP

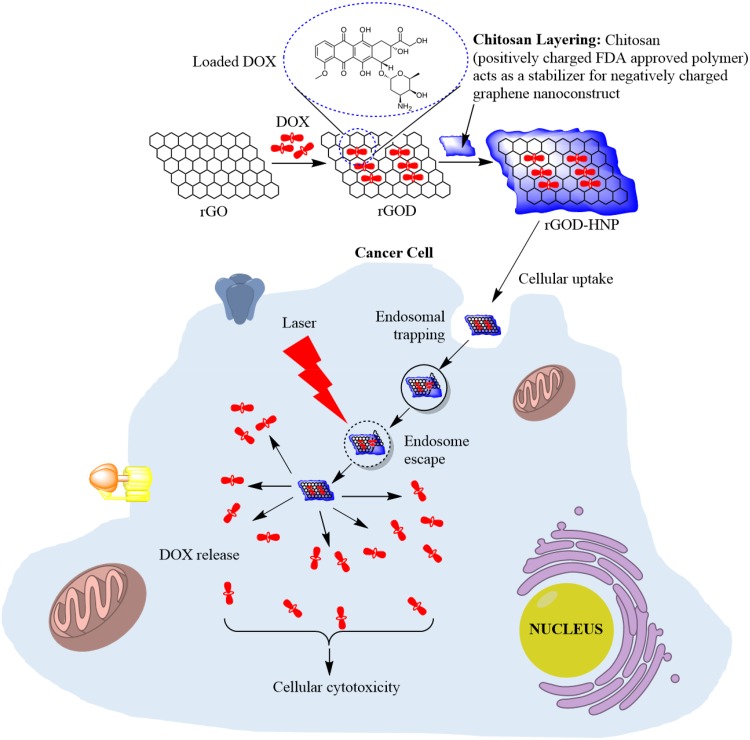

First, GO was prepared from flakes of graphite. The raw material was obtained using a modification of Hummer’s method in which we prolonged the probe sonication by 3 h to produce a reduced form of GO (rGO). A schematic of the synthesis of the formulation is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic for the synthesis and application of rGOD-HNP.

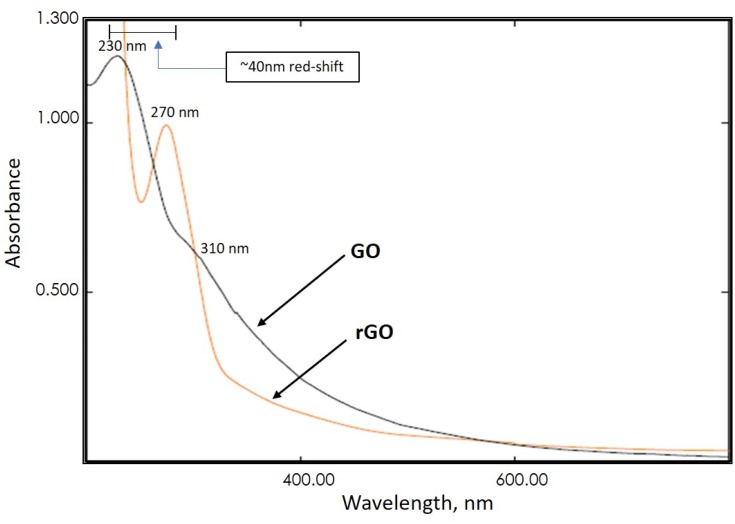

To confirm the formation of rGO from GO, we used UV-vis absorption and FT-IR spectroscopy. The spectra using UV-vis absorption on the GO sample demonstrated an absorption peak of ~230 nm, and was assigned to the π–π transition of C-C, while a shoulder peak of ~310 nm was recorded and assigned to the n–π* transition of C=O bonds (Figure 2). On the other hand, the rGO sample exhibited a broad peak at 270 nm, which indicated a ~40 nm red-shift as compared to the absorption peak of GO. We assigned these changes to be the deoxygenation of the GO sheets.

Figure 2.

Absorption spectra of GO and rGO. It represents the peak shifts during the conversion of GO to rGO.

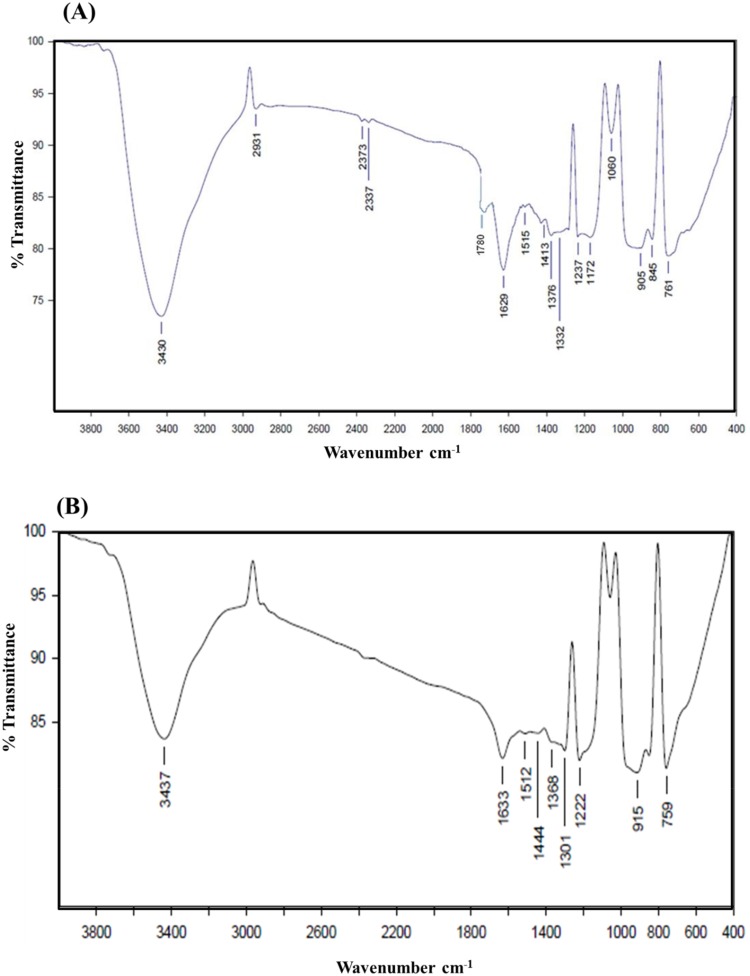

On further examination of the FTIR spectra of GO, we observed a sharp peak at 1780 cm−1, which we assigned to the C=O bond in carboxylic groups (Figure 3A). We also observed a peak at 1629 cm−1, which we believed was related to the C-C band. We found a band that vibrated 1060 cm−1, which represented the epoxy, and at 3430 cm−1, for the O-H band. After the reduction of graphene oxide was complete, the vibrational absorption band of carboxylic groups disappeared, while the C-O-C band appeared to be weakened (Figure 3B).

Figure 3 .

FT-IR spectra of (A) GO and (B) rGO. To further confirm the conversion of GO to rGO we perform FT-IR analysis.

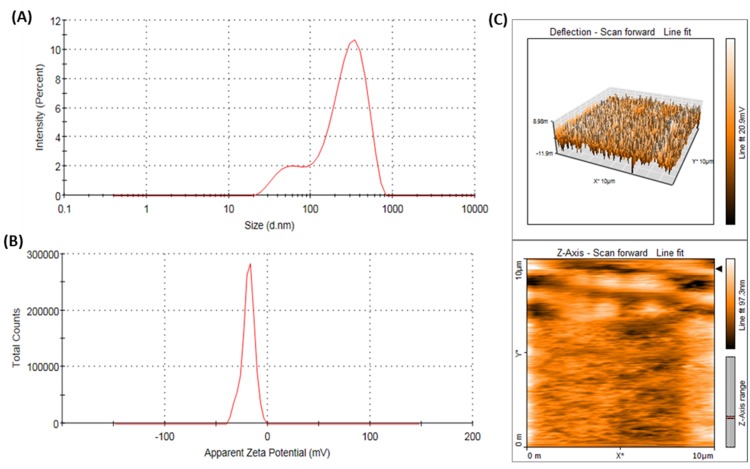

The reduced rGO has a size of 340.55±21.78 nm and a Zeta potential of −35.1±3.4 mV. We also loaded the DOX, and first stirred the aqueous dispersion for 24 h. The final DOX concentration was measured to be 1 mg/mL. The efficiency of entrapment returned as be 43.15±1.79%. Furthermore, we measured the efficiency of loading at pH 9.0 to be 58.72±2.91%. After DOX loading, there was a 20% increase in size to a final measurement of 410.51±19.83 nm (Figure 4A). We also noted a decrease (~5.3 mV) in zeta potential after DOX loading (Figure 4B). Finally, we hybridized the rGOD with 0.1% w/v chitosan by stirring 200 g for 24 h and stabilizing with TPP (0.125% w/v) to give a TPP tuned rGOD-HNP. The final particle size was measured to be 520.51±11.62 nm. A 2-dimensional (2D) and 3-dimensional (3D) atomic force microscopic (AFM) images of the rGOD-HNP are shown in Figure 4(C). It is evinced from the AFM report that the graphene oxide mixes well in the chitosan matrix during the layering process. The rGOD-HNP bears a rough and granular surface due to the presence of sheets of rGOD in its architect (Figure 4C). In agreement with our outcome, Hashemi et al have also reported high loading potential of DOX under basic pH. The authors also reported the efficient release of DOX from the GO-DOX complex and also cellular toxicity assay revealed that the best pH for loading of DOX on GO was 7.8.30

Figure 4.

(A) Hydrodynamic particle size and (B) average zeta potential, and (C) Atomic force microscopy (AFM) of rGOD-HNP.

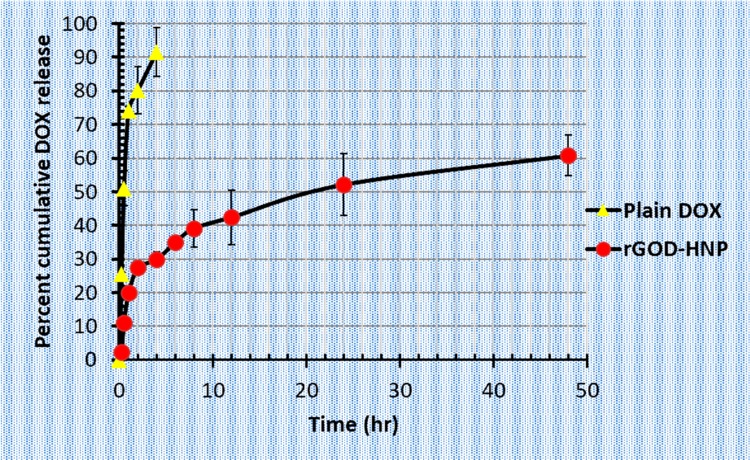

In vitro drug release study

To determine the bioavailability of DOX, we examined the in vitro release profile. We found a significant difference in the in vitro release profile of DOX as compared to rGOD-HNP at a pH of 7.4. In a time span of 4 h, DOX released less than 90% as compared to rGOD-HNP, which showed a sustained and slow release (Figure 5). We believe that this slow release of DOX is also due to core loading. As such, both attributes of rGOD-HNP may be due to the interaction between the aromatic rings of rGO and DOX. Previous research has also noted the same loading effect and pattern of drug release.31 Hashemi et al also developed a novel hydrogel nanocomposite films with anticancer properties via incorporation of graphene quantum dot (GQD) as a nanoparticle into carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC). In this work, the authors employed DOX as a model drug with broad-spectrum anticancer properties. Analogous to our observations on the pH sensitive release profile of DOX from graphene constructs, Namazi et al also observed the pH dependent release of DOX to be predominant under acidic pH.32

Figure 5.

The in vitro cumulative DOX from plain DOX as well as DOX bearing rGOD-HNP at physiological pH 7.4. Here, rGOD-HNP refers to the DOX-loaded reduced graphene oxide nanoformulation which is stabilized with chitosan. Results are represented as Mean ± S.D (n=3).

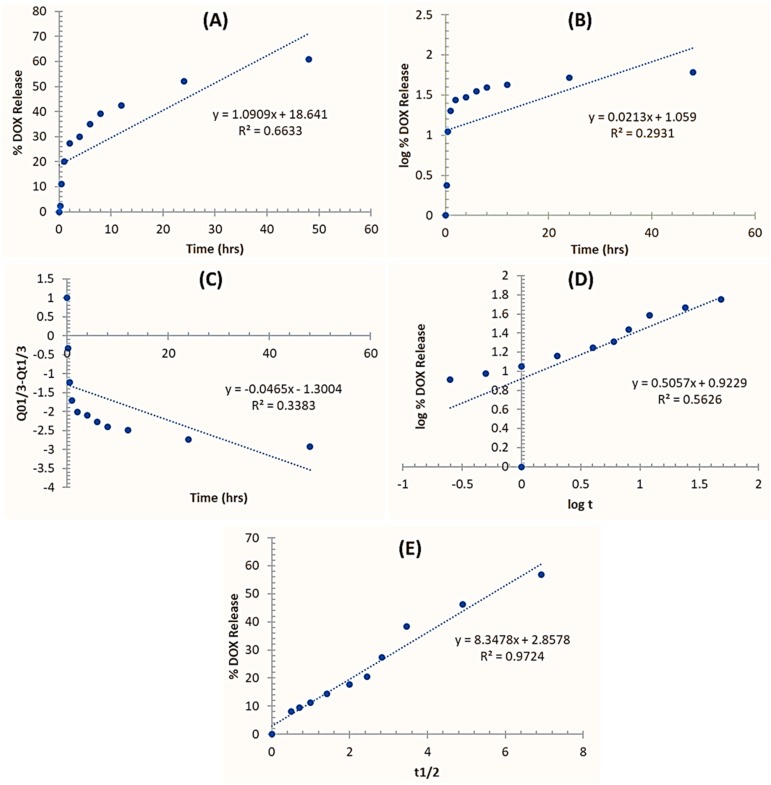

The typical order of drug release involved penetration, hydration, dissolution and finally diffusion. This usually occurs with a drug that needs to be released from a matrix, in our case chitosan played a role of matrix and helps in sustain the DOX release from rGOD-HNP. As such, due to this process, the erosion and swelling of a polymer are additional factors that affect drug release and its kinetics. We examined the DOX release behavior from our developed nano-formulation, specifically fitting for similar release models that include zero and first order, Korsmeyer–Peppas, Hixson–Crowell and Higuchi models. We demonstrated the kinetic models of the release behavior. We provided the regression coefficient (R2) and the relevant release kinetics in Table 1. Our data demonstrated the best fit with the Higuchi model with a linear regression coefficient value of 0.9724 (Figure 6E) as compared to 0.6632 (Figure 6A), 0.2931 (Figure 6B), 0.3383 (Figure 6C) and 0.5626 (Figure 6D) in cases of Zero-order kinetic model, First-order kinetic model, Hixson Model, and Korsmeyer–Peppas model, respectively.

Table 1.

The statistical regression coefficient (R2) as applied in different DOX release kinetic models

| Model | Equation | R2 Value of rGOD-HNP |

|---|---|---|

| Zero-order | Q = kt + b | 0.6633 |

| First-order | ln(100−Q) = −kt + b | 0.2931 |

| Hixson–Crowell | (100−Q)1/3= −kt + b | 0.3383 |

| Korsmeyer–Peppas | Qt/Q= ktn | 0.5626 |

| Higuchi | Q = kt1/2+ b | 0.9724 |

Note: Here, “t” is the time in which as definite fractional of drug “Q” is released from the formulation; “k” is the rate constant and “b” denotes a constant.

Figure 6.

The DOX release profiles from rGOD-HNP under physiological buffer pH 7.5 condition fitted to respective release kinetic models. (A) Zero-order kinetic model: cumulative % drug release vs. time; (B) First-order kinetic model: log % DOX release vs. time, (C) Hixson Model: Cube root of initial amount vs cumulative DOX release vs. time, (D) Korsmeyer–Peppas model: Log cumulative % DOX release vs. log time; (E) Higuchi model: Cumulative % DOX release vs. square root of time “t”. Q0 is the release at time 0 and Qt is the amount of drug release at time t.

We also found a time-dependent and sustained release of DOX from rGOD-HNP through the chitosan matrix, another role of chitosan apart from stabilizing nanosheets.33 We attribute this to the order of penetration, dissolution, and release from the chitosan polymeric matrix that occurs in a controlled manner.

NIR laser-mediated photothermal effect

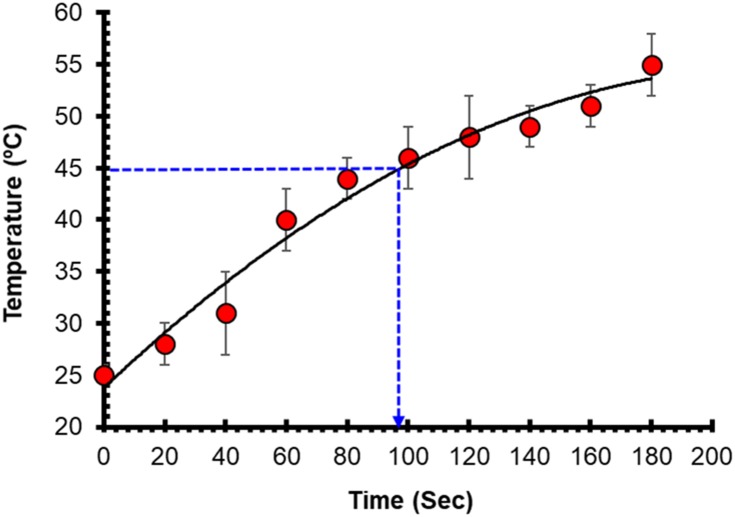

We examined the photothermal properties of synthesized rGOD-HNP using a NIR laser for irradiation for 200 seconds (Figure 7). We found a temperature increase in rGOD-HNP from a range of 25 °C to over 55 °C, most likely impacted by the absorption features of rGO. Over time, the temperature increased, and at 200 ms the highest temperature was noted to be 56 °C. This temperature is notable as the destruction of neoplastic cells can effective occur at the temperature, demonstrating their efficacy.

Figure 7.

A temperature rise in rGOD-HNP (50 μg/mL) following NIR laser of wavelength 808 nm irradiation. Here, the temperature increase was noted by dispersing rGOD-HNP in water. The thermometer was used for temperature measurement. Results are represented as Mean ± SD (n=3).

Hemolytic rate (blood compatibility test)

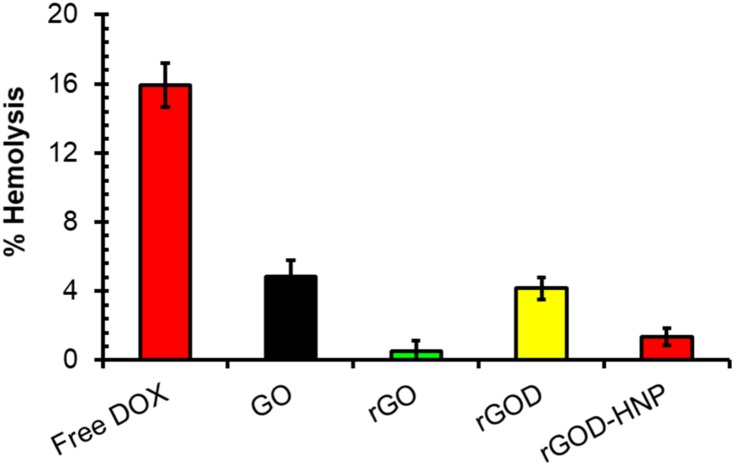

An early preclinical milestone for the development of a formulation that is to be administered intravenously is its biocompatibility with blood and its various components. We examined the effect of DOX, GO, rGO and rGOD-HNP on the hemolytic profile of red blood cells (RBC). From an analysis of RBC hemolysis, DOX (1ug/mL) demonstrated hemolysis at 16.4±0.12%. (Figure 8) However, GO, rGO and rGOD-HNP demonstrated hemolysis levels at 4.12±0.06%, 0.6±0.15%, and 1.21±0.16%, and had p-values >0.05, demonstrating insignificance. Overall, our data demonstrate justification for the safety of the formulation and its compatibility for IV administration.

Figure 8.

Hemolytic toxicity profile of different treatment groups. For the hemolytic assay, 5%v/v RBC suspension was incubated with test formulations, and the absorbance of test samples was taken at λmax 540 nm, against supernatant of normal saline as control. Results are represented as Mean ± SD (n=3).

Abbreviation: RBC, Red blood cell.

Cytotoxicity assay

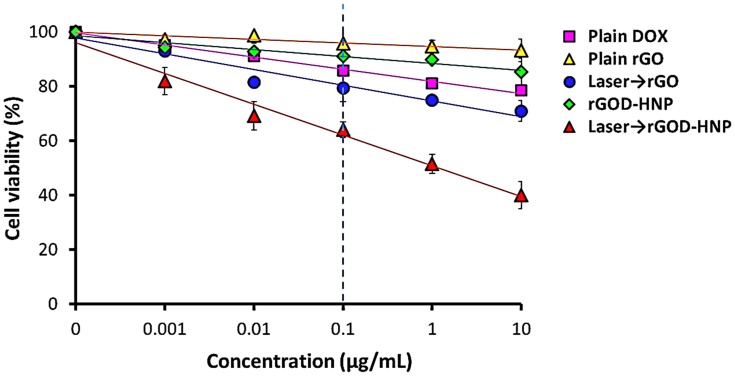

We performed an in vitro MTT cytotoxicity assay to examine the viability of a line of prostate cancer cells, PC-3, treated with DOX, rGO, laser irradiated rGO, rGOD-HNP and laser irradiated rGOD-HNP. Our results demonstrate that rGO has the highest degree of cytotoxicity in the activated and normal cells. We found an IC50 of 1 ug/mL (Figure 9; p<0.0001). In fact, laser irradiated rGOD-HNP (71.23±1.21%; p<0.0001) was more toxic, 2.53 times higher as compared to rGOD-HNP without laser irradiation (89.12±2.43%; p<0.0001). Our results could be explained by the photothermal influence of rGO. Furthermore, the acidic pH-triggered the release of DOX in PC-3 cells and could be the reason for why the laser irradiated formulations demonstrated enhanced toxicity.

Figure 9.

Percentage cell viability of PC-3 cells at 24 h (***; p<0.0001). Cell viability was performed on PC-3 cells per well in DMEM medium supplemented with 10%v/v FBS and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin mixture. Cell incubation was done in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37±0.5 °C. The absorbance of formazan crystals dissolved in lysis buffer was measured at 575 nm using microplate reader at 37±0.5 °C. Results are represented as Mean ± SD (n=6).

Abbreviations: DMEM, Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle medium; FBS, fetal bovine serum.

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated the formulation of a nanoscale therapeutic platform that uses chitosan as a matrix for stabilization. This therapeutic platform is a higher efficacious PTT that uses DOX as a model anti-neoplastic. We constructed HNP by loading DOX into rGO with high efficiency (>60%) and coating it with chitosan that was stabilized using TPP. We found that the HNP efficiently trapped and loaded the drug. Furthermore, our cell viability studies showed the ability of HNP to specifically target DOX to a site and were efficacious in the PC-3 cancer cell (cytotoxicity with hybrid HNP was >65%). The HNP efficiently converts energy to heat using irradiation with NIR 808 nm, most likely due to rGO. Furthermore, it was also demonstrated that rGOD-HNP can intracellularly deliver DOX and more specifically in PC-3 prostate cancer cells. Our examination of the in vitro drug release (60% in 48 h) demonstrates that the formulation can hold the drug for long durations and the formulation can be used for sustained delivery. This developed graphene-based drug delivery tool offers a feasible and viable approach to deliver DOX photo-thermally to offer a clinically translatable mode for the treatment of prostate cancer.

Acknowledgment

This research was funded by Deanship of Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia. Grant Number: 17122014.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Grizzi F, Taverna G, Cote RJ, Guazzoni G. Prostate cancer: from genomics to the whole body and beyond. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sumanasuriya S, De Bono J. Treatment of advanced prostate cancer—A review of current therapies and future promise. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8(6):a030635. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a030635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soni N, Soni N, Pandey H, Maheshwari R, Kesharwani P, Tekade RK. Augmented delivery of gemcitabine in lung cancer cells exploring mannose anchored solid lipid nanoparticles. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;481:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2016.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tekade RK, Maheshwari R, Soni N, Tekade M, Chougule MB. Chapter 1 - Nanotechnology for the development of nanomedicine A2 - Mishra, Vijay In: Kesharwani P, Amin MCIM, Iyer A, editors. Nanotechnology-Based Approaches for Targeting and Delivery of Drugs and Genes. Academic Press; 2017:3–61. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahajan S, Patharkar A, Kuche K, et al. Functionalized carbon nanotubes as emerging delivery system for the treatment of cancer. Int J Pharm. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zare-Zardini H, Taheri-Kafrani A, Amiri A, Bordbar A-K. New generation of drug delivery systems based on ginsenoside Rh2-, Lysine-and Arginine-treated highly porous graphene for improving anticancer activity. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):586. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18938-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zamani M, Rostami M, Aghajanzadeh M, Manjili HK, Rostamizadeh K, Danafar H. Mesoporous titanium dioxide@ zinc oxide–graphene oxide nanocarriers for colon-specific drug delivery. J Mater Sci. 2018;53(3):1634–1645. doi: 10.1007/s10853-017-1673-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCoy TM, de Campo L, Sokolova A, Grillo I, Pas EI, Tabor R. Bulk properties of aqueous graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide with surfactants and polymers: adsorption and stability. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2018. doi: 10.1039/C8CP02738B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang Z, Shan K, Song J, et al. Toxic effects of magnetic nanoparticles on normal cells and organs. Life Sci. 2019;220:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.01.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pugazhendhi A, Prabhu R, Muruganantham K, Shanmuganathan R, Natarajan S. Anticancer, antimicrobial and photocatalytic activities of green synthesized magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgONPs) using aqueous extract of Sargassum wightii. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2019;190:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saratale RG, Karuppusamy I, Saratale GD, et al. A comprehensive review on green nanomaterials using biological systems: recent perception and their future applications. Colloids Surf B. 2018;170:20–35. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.05.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sisubalan N, Ramkumar VS, Pugazhendhi A, et al. ROS-mediated cytotoxic activity of ZnO and CeO 2 nanoparticles synthesized using the Rubia cordifolia L. leaf extract on MG-63 human osteosarcoma cell lines. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;25(11):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Srinivasan M, Venkatesan M, Arumugam V, et al. Green synthesis and characterization of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) using Sesbania grandiflora and evaluation of toxicity in zebrafish embryos. Process Biochem. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2019.02.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pugazhendhi A, Edison TNJI, Karuppusamy I, Kathirvel B. Inorganic nanoparticles: a potential cancer therapy for human welfare. Int J Pharm. 2018;539(1–2):104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.01.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pugazhendhi A, Edison TNJI, Velmurugan BK, Jacob JA, Karuppusamy I. Toxicity of doxorubicin (Dox) to different experimental organ systems. Life Sci. 2018;200:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suganthy N, Ramkumar VS, Pugazhendhi A, Benelli G, Archunan G. Biogenic synthesis of gold nanoparticles from Terminalia arjuna bark extract: assessment of safety aspects and neuroprotective potential via antioxidant, anticholinesterase, and antiamyloidogenic effects. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;25(11):1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shanmuganathan R, Edison TNJI, LewisOscar F, Ponnuchamy K, Shanmugam S, Pugazhendhi A. Chitosan nanopolymers: an overview of drug delivery against cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.02.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maheshwari RG, Thakur S, Singhal S, Patel RP, Tekade M, Tekade RK. Chitosan encrusted nonionic surfactant based vesicular formulation for topical administration of ofloxacin. Sci Adv Mater. 2015;7(6):1163–1176. doi: 10.1166/sam.2015.2245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tekade RK, Maheshwari R, Tekade M. 4 - Biopolymer-based nanocomposites for transdermal drug delivery In: Jana S, Maiti S, Jana S, editors. Biopolymer-Based Composites. Woodhead Publishing; 2017:81–106. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsai W-H, Yu K-H, Huang Y-C, Lee C-I. EGFR-targeted photodynamic therapy by curcumin-encapsulated chitosan/TPP nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:903. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S177627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goswami U, Dutta A, Raza A, et al. Transferrin–copper nanocluster–doxorubicin nanoparticles as targeted theranostic cancer Nanodrug. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(4):3282–3294. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b15165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deb A, Vimala R. Natural and synthetic polymer for graphene oxide mediated anticancer drug delivery—A comparative study. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;107:2320–2333. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.10.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao X, Wei Z, Zhao Z, et al. Design and development of graphene oxide nanoparticle/chitosan hybrids showing pH-sensitive surface charge-reversible ability for efficient intracellular doxorubicin delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(7):6608–6617. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b16910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maheshwari RG, Tekade RK, Sharma PA, et al. Ethosomes and ultradeformable liposomes for transdermal delivery of clotrimazole: a comparative assessment. Saudi Pharm J. 2012;20(2):161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muniswamy VJ, Raval N, Gondaliya P, Tambe V, Kalia K, Tekade RK. ‘Dendrimer-Cationized-Albumin’encrusted polymeric nanoparticle improves BBB penetration and anticancer activity of doxorubicin. Int J Pharm. 2019;555:77–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maheshwari R, Sharma P, Tekade M, et al. Microsponge embedded tablets for sustained delivery of nifedipine. Pharm Nanotechnol. 2017;5(3):192–202. doi: 10.2174/2211738505666170921125549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tayyebi A, Akhavan O, Lee B-K, Outokesh M. Supercritical water in top-down formation of tunable-sized graphene quantum dots applicable in effective photothermal treatments of tissues. Carbon. 2018;130:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2017.12.057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Q, Wang H, Liu H, et al. Multifunctional dendrimer-entrapped gold nanoparticles modified with RGD peptide for targeted computed tomography/magnetic resonance dual-modal imaging of tumors. Anal Chem. 2015;87(7):3949–3956. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Y, Wang Y, Gong J, et al. Chitosan degradation products facilitate peripheral nerve regeneration by improving macrophage-constructed microenvironments. Biomaterials. 2017;134:64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hashemi M, Yadegari A, Yazdanpanah G, et al. Normalization of doxorubicin release from graphene oxide: new approach for optimization of effective parameters on drug loading. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2017;64(3):433–442. doi: 10.1002/bab.1487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang XX, Li CM, Li YF, Wang J, Huang CZ. Synergistic antiviral effect of curcumin functionalized graphene oxide against respiratory syncytial virus infection. Nanoscale. 2017;9(41):16086–16092. doi: 10.1039/c7nr06520e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Javanbakht S, Namazi H. Doxorubicin loaded carboxymethyl cellulose/graphene quantum dot nanocomposite hydrogel films as a potential anticancer drug delivery system. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2018;87:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campos EVR, De Oliveira JL, Da Silva CMG, et al. Polymeric and solid lipid nanoparticles for sustained release of carbendazim and tebuconazole in agricultural applications. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13809. doi: 10.1038/srep13809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]