Key Points

Question

What are the prevalence and motivations surrounding courtesy authorship in current surgical academia?

Findings

This survey study found that courtesy authorship remains prevalent (17%). The rates and motivations of courtesy authorship vary greatly between first and senior authors as well as in high and low impact factor journals.

Meaning

Courtesy authorship remains a common practice in surgical academia, and by understanding the motivations and incentives, clinicians can work to eliminate its occurrence.

Abstract

Importance

Courtesy authorship is defined as including an individual who has not met authorship criteria as an author. Although most journals follow strict authorship criteria, the current incidence of courtesy authorship is unknown.

Objective

To assess the practices related to courtesy authorship in surgical journals and academia.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A survey was conducted from July 15 to October 27, 2017, of the first authors and senior authors of original articles, reviews, and clinical trials published between 2014 and 2015 in 8 surgical journals categorized as having a high or low impact factor.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The prevalence of courtesy authorship overall and among subgroups of authors in high impact factor journals and low impact factor journals and among first authors and senior authors, as well as author opinions regarding courtesy authorship.

Results

A total of 203 first authors and 254 senior authors responded (of 369 respondents who provided data on sex, 271 were men and 98 were women), with most being in academic programs (first authors, 116 of 168 [69.0%]; senior authors, 173 of 202 [85.6%]). A total of 17.2% of respondents (42 of 244) reported adding courtesy authors for the surveyed publications: 20.4% by first authors (32 of 157) and 11.5% by senior authors (10 of 87), but 53.7% (131 of 244) reported adding courtesy authorship on prior publications and 33.2% (81 of 244) had been added as a courtesy author in the past. Although 45 of 85 senior authors (52.9%) thought that courtesy authorship has decreased, 93 of 144 first authors (64.6%) thought that courtesy authorship has not changed or had increased (P = .03). There was no difference in the incidence of courtesy authorship for low vs high impact factor journals. Both first authors (29 of 149 [19.5%]) and senior authors (19 of 85 [22.4%]) reported pressures to add courtesy authorship, but external pressure was greater for low impact factor journals than for high impact factor journals (77 of 166 [46.4%] vs 60 of 167 [35.9%]; P = .04). More authors in low impact factor journals than in high impact factor journals thought that courtesy authorship was less harmful to academia (55 of 114 [48.2%] vs 34 of 117 [29.1%]). Overall, senior authors reported more positive outcomes with courtesy authorship (eg, improved morale and avoided author conflicts) than did first authors.

Conclusions and Relevance

Courtesy authorship use is common by both first and senior authors in low impact factor journals and high impact factor journals. There are different perceptions, practices, and pressures to include courtesy authorship for first and senior authors. Understanding these issues will lead to better education to eliminate this practice.

This survey study assesses the practices related to courtesy authorship in surgical journals and academia.

Introduction

Publishing scientific and scholarly work in peer-reviewed journals remains a cornerstone of modern academic surgical practice and is also a commonly used metric to assess and compare performance between peers.1,2,3 The oft-used adage to “publish or perish” creates a number of pressures and incentives for violating strict authorship criteria and guidelines.4,5,6,7 Courtesy authorship is defined as including an individual as an author in a scientific article even though he or she has not made a contribution that meets the 4 criteria as defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE): (1) substantial contributions to conception or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; (2) drafting of the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; (3) final approval of the version to be published; and (4) agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.8

As a result of the ICMJE, most academic surgical journals now have strict guidelines regarding authorship criteria, but the incidence of courtesy authorship (ie, honorary authorship) is poorly studied. Flanagin et al9 mailed surveys to corresponding authors of 3 large circulation journals and 3 small circulation journals. Of the respondents, 19% confirmed that a courtesy author had been added to their publication; the survey also found that 11% of publications included a “ghost author” or an author who had contributed substantially to the article but was not included in the list of authors. Other studies report similar findings, with courtesy authorship rates ranging between 17% and 44%.7,10,11 Few data exist on this practice among academic surgeons and in surgical journals.

Specific authorship guidelines set by each journal may play a role in courtesy authorship as found by Bates et al,12 who examined author contributions for the Annals of Internal Medicine, BMJ, and JAMA to determine courtesy authorship based on the defined ICMJE criteria. They found courtesy authorship ranging from 60% in the Annals of Internal Medicine to 4% in JAMA. An additional study surveyed corresponding authors from 5 high impact factor surgical journals and found that 44% of respondents reported that at least 1 author did not meet ICMJE standards.10 This study also revealed large variability in courtesy authorship rates among these high impact factor journals but did not capture any data about the underlying associated factors and opinions regarding courtesy authorship.

The motivations driving courtesy authorship are debatable and not well studied in any setting, particularly in academic surgery. One group offered explanations for these practices based on 3 categories of courtesy authorship (gift authorship, guest authorship, and coercive authorship).13 Gift authorship simply means adding an author out of respect or gratitude for that individual. Guest authorship includes adding a well-known author to the article to increase the validity or value of the article. Coercive authorship consists of pressure from a senior researcher to a more junior researcher to include a gift author or guest author. Each of these categories has unique pressures that overall likely contribute to the ongoing practice of courtesy authorship.

We hypothesized that the incidence of courtesy authorship continues to occur with relative frequency and that this practice is prevalent in both high impact factor and low impact factor surgical journals. The goals of our study were to evaluate the incidence, perceptions, and motivations of courtesy authorship and make direct comparisons between first author and senior author respondents as well as the differences in high impact factor and low impact factor surgical journals.

Methods

We chose 8 surgical journals to include in the study. Five high impact factor journals and 3 low impact factor journals were included based on the 2017 impact factor rankings and diversity within the field of surgery. The high impact factor journals included were the Annals of Surgery (impact factor, 9.2), JAMA Surgery (impact factor, 8.5), Journal of the American College of Surgeons (impact factor, 4.8), Society for Obesity and Related Diseases (impact factor, 3.9), and Diseases of the Colon and Rectum (impact factor, 3.5). The low impact factor journals included were The American Journal of Surgery (impact factor, 2.4), Journal of Surgical Research (impact factor, 2.2), and Journal of Surgical Education (impact factor, 1.4). This study was reviewed and approved by the Legacy Emanuel Medical Center Institutional Review Board, Portland, Oregon. As the surveys were anonymous and no personal data were linked to the survey in any way, participant consent was waived.

Names were collected of the first authors and senior authors of US and Canadian original articles, reviews, and clinical trials published in each journal between 2014 and 2015. We defined first author as the first author listed on the line of authors and senior author as the last author listed. Articles that were attributed to a group authorship and where the first author and senior author could not reliably be established were excluded. Using PubMed, Google Scholar, and the American College of Surgeons websites, we obtained the authors’ email addresses. Duplicate entries were excluded when the authors were listed either in the same year or different journal; these authors were asked to respond in reference to their most recent publication.

The surveys were created and distributed from July 15 to October 27, 2017, using SurveyMonkey (http://www.surveymonkey.com). Separate anonymous surveys were created for first authors and senior authors, with each survey containing the same core questions and several unique questions specific to that group, for a total of 34 questions for first authors and 36 questions for senior authors, with an additional comment section for both. The first 10 questions assessed the demographics of our respondents and their respective article. The next 7 questions evaluated the prevalence of courtesy authorship from the author’s perspective. The next 4 questions focused on opinions of courtesy authorship. The final 7 to 9 questions specific to either the first author or senior author further addressed author selection and motivations regarding courtesy authorship.

The online survey was sent to the authors beginning July 15, 2017, and left open for 3 months, with 4 reminder emails sent to nonresponders every 3 weeks. The survey was closed October 27, 2017. Using Predictive Analysis Software, version 25.0 (SPSS Inc), we first explored the demographics of our study population using descriptive data analysis for continuous variables. χ2 Tests were used to compare the respondents’ characteristics and the variations between subgroups. All P values were from 2-sided tests, and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05. To assess for any obvious response bias, we compared the demographics of the responding authors from the entire solicited population in terms of author rank and order, journal impact factor, type of publication, and high vs low impact factor journal. There were no significant differences noted between the 2 populations on these basic demographic variables.

Results

Responses/Demographics

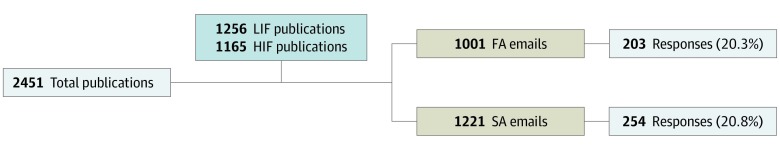

A total of 2451 journal publications met inclusion for analysis (Figure 1). Our survey response rate was 20.6% (457 of 2222). A total of 203 first authors and 254 senior authors responded (of 369 respondents who provided data on sex, 271 were men and 98 were women), with most being in academic programs (first authors, 116 of 168 [69.0%]; senior authors, 173 of 202 [85.6%]). Demographics for respondents are shown in the Table.

Figure 1. Total Responses and Response Rate.

FA indicates first author; HIF, high impact factor; LIF, low impact factor; and SA, senior author.

Table. Characteristics of Respondents.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex (n = 369) | |

| Male | 271 (73.4) |

| Female | 98 (26.6) |

| Rank (n = 370) | |

| Faculty (≥11 y) | 181 (48.9) |

| Faculty (6-10 y) | 63 (17.0) |

| Faculty (≤5 y) | 49 (13.2) |

| Resident | 34 (9.2) |

| Fellow | 21 (5.7) |

| Other | 22 (5.9) |

| Type of practice (n = 370) | |

| University or academic | 289 (78.1) |

| Community, teaching | 33 (8.9) |

| Military | 12 (3.2) |

| Veterans Affairs | 10 (2.7) |

| Other | 26 (7.0) |

| Articles/y, mean, No. (n = 371) | |

| 1-3 | 114 (30.7) |

| 4-6 | 100 (27.0) |

| 7-9 | 54 (14.6) |

| ≥10 | 103 (27.8) |

| Authors of article, No. (n = 366) | |

| 1-3 | 31 (8.5) |

| 4-6 | 220 (60.1) |

| 7-9 | 82 (22.4) |

| ≥10 | 33 (9.0) |

| Type of study (n = 365) | |

| Single-center | 283 (77.5) |

| Multicenter | 82 (22.5) |

Courtesy Authorship

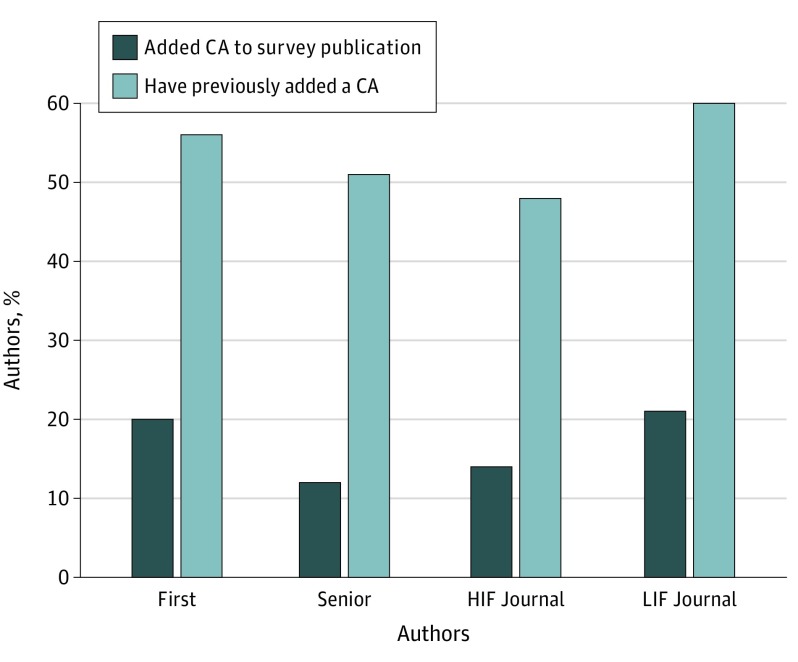

A total of 17.2% of respondents (42 of 244) reported adding courtesy authors for the surveyed publications: 20.4% by first authors (32 of 157) and 11.5% by senior authors (10 of 87). Comparisons in incidence of courtesy authorship between first authors and senior authors is shown in Figure 2. More than half (53.7% [131 of 244]) of the respondents reported previously adding a courtesy author to a peer-reviewed article. Almost half (48.0% [59 of 123]) of all respondents believe that up to 50% of their prior peer-reviewed articles have included courtesy authors, with 52.5% of those respondents (64 of 122) reporting only 1 courtesy authorship usually added per article. In addition, 33.2% (81 of 244) of both first authors and senior authors reported that they have previously been added to a publication as a courtesy author. There were no differences in courtesy authorship rates between male and female first authors and senior authors.

Figure 2. Prevalence of Courtesy Authorship Among Surveyed Authors in Comparison With Authors Who Have Previously Added a Courtesy Author (CA).

HIF indicates high impact factor; LIF, low impact factor.

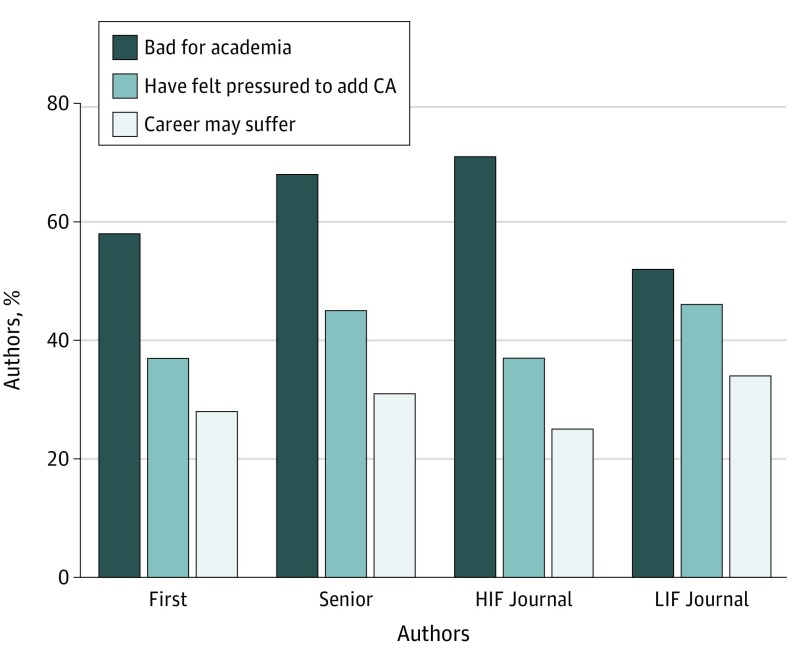

First authors’ and senior authors’ opinions regarding courtesy authorship as being bad for academia, whether they felt pressured to add courtesy authorship, or that their career may suffer if they did not add courtesy authors are shown in Figure 3. Although 52.9% of senior authors (45 of 85) thought that the practice of courtesy authorship has decreased over time, 64.6% of first authors (93 of 144) believe that the practice has actually stayed the same or increased (P = .03). In addition, 19.5% of first authors (29 of 149) vs 22.4% of senior authors (19 of 85) reported an expectation in their practice to add a courtesy authorship. Both reported that a senior partner, section or division chief, or chair are the most common individuals added to a publication (156 of 234 [66.7%]) vs a colleague or junior author (35 of 234 [15.0%]). In regard to sex, 46% of female first authors (23 of 50) felt pressured to add a courtesy author to their article compared with 32.0% of male first authors (32 of 100), which was not statistically significant. Of first authors, 85.8% (121 of 141) reported that they had an active role in choosing the courtesy authors, and 89.4% (126 of 141) reported that they had an active role in determining authorship order. Only 14.2% of first authors (20 of 141) responded that the senior author chose courtesy authors independently, whereas 51.8% of the senior authors (43 of 83) reported that this was their decision alone.

Figure 3. Opinions and Pressures of Surveyed Authors.

CA indicates courtesy author; HIF, high impact factor; and LIF, low impact factor.

As for attempts by surgical journals to minimize courtesy authorship, 55.4% of senior authors (46 of 83) believe that authorship guidelines set by the journals have caused courtesy authorship to decline, while 64.6% of first authors (93 of 144) think that this practice has not caused any change in prevalence (P = .04). Similarly, when asked if listing authors’ contributions in the manuscript has led to a change in courtesy authorship, 49.4% of senior authors (42 of 85) think that this practice has caused it to decline, while 58.3% of first authors (84 of 144) do not believe that it made a difference.

High Impact Factor Journals vs Low Impact Factor Journals

Comparisons in the incidence of courtesy authorship between high impact factor journals and low impact factor journals is shown in Figure 2. The results of low impact factor journal vs high impact factor journal authors’ opinions on courtesy authorship as bad for academia, whether they have felt pressured to provide courtesy authorship, and whether failing to provide courtesy authorship will be harmful to their career is shown in Figure 3. There was no difference reported between authors in high impact factor journals vs low impact factor journals that courtesy authorship improves the morale of their practice (high impact factor, 33 of 80 [41.3%] vs low impact factor, 45 of 89 [50.6%]; P = .07). More first authors and senior authors from low impact factor journals were from single-center studies (low impact factor, 161 of 188 [85.6%] vs high impact factor, 122 of 177 [68.9%]; P < .001) and thought that courtesy authorship was less harmful to academia (low impact factor, 55 of 114 [48.2%] vs high impact factor, 34 of 117 [29.1%]; P = .003). More authors from low impact factor journals believe that listing of the authors’ contributions has caused courtesy authorship to decline (low impact factor, 77 of 113 [68.1%] vs high impact factor, 49 of 114 [43.0%]; P = .06), but there was no difference between authors from high impact factor journals and authors from low impact factor journals as a result of authorship guidelines (high impact factor, 58 of 114 [50.9%] vs low impact factor, 72 of 113 [63.7%]; P = .15).

Discussion

This study sought to analyze the practices and incidence of courtesy authorship from 8 surgical journals and to add to the relatively sparse literature on this important but little-discussed issue. We focused on US and Canadian studies to avoid misinterpretations of differences in academic rank, structure, and culture in other countries. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine opinions from both the first authors and senior authors in a cohort of academic surgical journals. This study not only provides a current estimate of the prevalence of courtesy authorship in the surgical literature but also provides unique results that evaluate the motivations for the use of courtesy authorship. In addition, our survey compares results between higher impact factor journals and lower impact factor journals. Our hypotheses were correct that there would be significantly different results in the use of courtesy authorship, as well as underlying perceptions of and motivations for the use of courtesy authorship, based on the author level and journal impact factor.

Although there are a number of professional authorship guidelines available and all peer-reviewed medical journals now outline the strict and well-defined criteria that should be met for authorship on a submitted article, the practice of courtesy authorship remains common in the medical and surgical literature.2,8,9,11,13,14 For a practice that is widely discouraged and considered a form of academic fraud by some, the continued frequent use of courtesy authorship in academic surgery highlights that there must be some major existing incentives or supporting pressures to use courtesy authorship. These incentives are well known to anyone in modern academia, where peer-reviewed publications serve as a form of career currency and even a professional status symbol.6,15,16,17 In academic medicine, decisions regarding promotion and/or tenure typically weigh the applicant’s track record of peer-reviewed publications heavily. In many cases, the total number of publications is used as a proxy for the applicant’s “academic productivity” and likelihood for future publications,17,18 which can have significant implications for promotions, key assignments, salary raises and other financial rewards, and academic status relative to peers. In addition, increasing the number of publications attributed to a surgeon can serve to significantly bolster his or her reputation outside of his or her home institution and may be used as a factor in selection for local and national leadership roles, invited lectureships, and other national or international opportunities.

In support of the “publish or perish” mantra, one Danish study found that the number of authors per publication has increased in all types of articles during the past 50 years.19 Another editorial contemplates the motivations for clinicians and scientists to continue to publish regardless of their academic status.20 The author explains, “the larger the number the better,”20(p183) or the academic accomplishments are often highlighted as the author has “published over X papers.”20(p183) Both suggest that the academic surgeon is no longer defined by surgical mastership but by easily quantifiable metrics of academic productivity, such as the number of peer-reviewed publications he or she has authored. One obvious criticism of this approach is that there may be little to no focus on the quality or true impact of a given author’s journal publications and that volume is being rewarded over substance. This possibility is supported by the overall negative perceptions and opinions of courtesy authorship based on our survey results.

Although the use of courtesy authorship is often viewed as a “victimless crime,” it can clearly have multiple negative effects that go beyond the simple falsely inflated academic reputation of the courtesy authorship. These effects include the recognition or promotion of less-qualified personnel vs a more qualified peer, the marginalization of populations who are already underrepresented in academic surgery, and the misuse of salary or research funds based on a falsely inflated publication history.21,22,23 As highlighted in a very thorough review and opinion piece on courtesy authorship, “despite its general acceptance among many scientists, honorary authorship is unethical.”14(p76) Although a discussion of ways to minimize these practices but continue to incentivize high-quality academic productivity and collaboration is beyond the scope of this article, we believe that there are potential viable partial solutions.

Strategies to mitigate the practice of courtesy authorship are needed. As described by Gasparyan et al,5 multiple society and editorial policy statements, including ICMJE, have been proposed to reduce inappropriate authorship. However, an abundance of literature presents evidence that, even though many medical journals abide by ICMJE authorship criteria (or similar standards), adherence is actually quite low, ranging from 16% to 59%.24,25,26 One solution is for journals to strictly adhere to ICMJE authorship and nonauthor contributorship guidelines. The ICMJE recommends that authors must meet all 4 of the following criteria: “(1) substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; (2) drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; (3) final approval of the version to be published; and (4) agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.”8 Nonauthor contributors are defined as follows: “Contributors who meet fewer than all 4 of the above criteria for authorship should not be listed as authors, but they should be acknowledged. Examples of activities that alone (without other contributions) do not qualify a contributor for authorship are acquisition of funding; general supervision of a research group or general administrative support; and writing assistance, technical editing, language editing, and proofreading. Those whose contributions do not justify authorship may be acknowledged individually or together as a group under a single heading (eg, “Clinical Investigators” or “Participating Investigators”), and their contributions should be specified (eg, “served as scientific advisors,” “critically reviewed the study proposal,” “collected data,” “provided and cared for study patients,” “participated in writing or technical editing of the manuscript”).”8 Although many journals have the ICMJE authorship criteria in the instructions for authors, we believe both authorship criteria and nonauthor contributor criteria should be included and adhered to by authors. Nonauthor contributors are then included in the acknowledgments section of the manuscript. As much as authors must be aware of the ethics of inappropriate authorship, journals must continue to set a high standard for authorship vs nonauthor contributors and, importantly, must enforce this standard to the best of their ability. The inclusion of checkboxes verifying the role of each individual author is one method that many journals use. This practice forces the corresponding author or senior author to actively think about the inclusion of each author. Institutions could play a larger role in increasing awareness of authorship and nonauthor contributor roles among their faculty. If both the institution and journal strive to clarify these roles and force the author to really think about the merits of their contribution during manuscript submission, this may prevent intentional courtesy authorship or incidents of inappropriate inclusion of authors who do not meet the strict authorship guidelines. Ideally, an international consensus acknowledging the role of nonauthor contributorship would also help to mitigate the problem. If promotion and tenure committees recognized the value of nonauthor contributorship toward promotion, the pressure to inappropriately include authors may be diminished. Further detailed study and adequate controlling for those major confounders will be required to definitively answer this and other key questions about the use of courtesy authorship.

A consensus on punitive measures for this unethical activity has yet to be made. Recommendations may include redaction of the publication from the journal, notifying the authors’ institutional officials of the practice, referral to the institution’s ethics committee, and prohibiting the author(s) from publishing in the journal for a set period of time. However, we also recognize the difficulty in identifying or proving a charge of courtesy authorship because there are no objective screening tools available as found for detecting plagiarism.

Limitations

This study has several important limitations. The first limitation includes the retrospective nature by addressing a single article that was published up to 2 years prior to the start of our survey. However, many of our questions were designed to assess the current practices of courtesy authorship. Another limitation of our study includes the moderate response rate, which is characteristic of many survey studies. Our response rate was 21%, which is overall comparable with other articles addressing the practices of courtesy authorship and which is common among internet-based surveys. However, we recognize that this response rate introduces the potential for significant response bias, and these survey results may not be fully representative of the cohort from which the sample was drawn. Another limitation of our study might be nonresponse bias, which has been described as an element of research surveys and is applicable to our survey given the sensitivity of commenting on courtesy authorship.27 We were clear in our survey directions that the survey was completely anonymous, but nonresponse bias may have contributed to our response rate. Finally, although our study addresses and characterizes courtesy authorship as a problem in surgical journals, our study does not address mitigation strategies or punitive measures for confirmed courtesy authorship.

Conclusions

Courtesy authorship has not been well studied in the current literature, and our findings suggest that it remains prevalent despite ICMJE authorship guidelines. There are clear differences in the rates of courtesy authorship between first authors and senior authors and between high impact factor journals and low impact factor journals that should be explored further to better characterize this practice and the underlying motivations or incentives that are driving it. By understanding the perceptions, opinions, and motivations of courtesy authorship as well as the differences between categories of authors and journals, we can better work to discourage and eliminate this practice in surgical literature. Future studies on mitigation strategies are of paramount importance.

References

- 1.Schimanski LA, Alperin JP. The evaluation of scholarship in academic promotion and tenure processes: past, present, and future. F1000Res. 2018;7:1605. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.16493.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mentzelopoulos SD, Zakynthinos SG. Research integrity, academic promotion, and attribution of authorship and nonauthor contributions. JAMA. 2017;318(13):1221-1222. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warner ET, Carapinha R, Weber GM, Hill EV, Reede JY. Faculty promotion and attrition: the importance of coauthor network reach at an academic medical center. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):60-67. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3463-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gast KM, Kuzon WM Jr, Waljee JF. Bibliometric indices and academic promotion within plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(5):838e-844e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasparyan AY, Ayvazyan L, Kitas GD. Authorship problems in scholarly journals: considerations for authors, peer reviewers and editors. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(2):277-284. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2582-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dempsey JA. Impact factor and its role in academic promotion: a statement adopted by the International Respiratory Journal Editors Roundtable. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009;107(4):1005. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00891.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mowatt G, Shirran L, Grimshaw JM, et al. Prevalence of honorary and ghost authorship in Cochrane reviews. JAMA. 2002;287(21):2769-2771. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.21.2769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Committee of Medical Journal Editors Defining the role of authors and contributors. http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- 9.Flanagin A, Carey LA, Fontanarosa PB, et al. Prevalence of articles with honorary authors and ghost authors in peer-reviewed medical journals. JAMA. 1998;280(3):222-224. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.3.222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luiten JD, Verhemel A, Dahi Y, Luiten EJT, Gadjradj PS. Honorary authorships in surgical literature. World J Surg. 2019;43(3):696-703. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-4831-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wislar JS, Flanagin A, Fontanarosa PB, DeAngelis CD. Honorary and ghost authorship in high impact biomedical journals: a cross sectional survey. BMJ. 2011;343:d6128. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bates T, Anić A, Marusić M, Marusić A. Authorship criteria and disclosure of contributions: comparison of 3 general medical journals with different author contribution forms. JAMA. 2004;292(1):86-88. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.1.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feeser VR, Simon JR. The ethical assignment of authorship in scientific publications: issues and guidelines. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(10):963-969. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00239.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moffatt B. Responsible authorship: why researchers must forgo honorary authorship. Account Res. 2011;18(2):76-90. doi: 10.1080/08989621.2011.557297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adler KB. Impact factor and its role in academic promotion. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41(2):127. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.R09ED1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arenson RL, Lu Y, Elliott SC, Jovais C, Avrin DE. Measuring the academic radiologist’s clinical productivity: applying RVU adjustment factors. Acad Radiol. 2001;8(6):533-540. doi: 10.1016/S1076-6332(03)80628-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixon AK. Publishing and academic promotion. Singapore Med J. 2009;50(9):847-850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gjerde C, Clements W, Clements B. Publication characteristics of family practice faculty nominated for academic promotion. J Fam Pract. 1982;15(4):663-666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vinther S, Rosenberg J. Authorship trends over the past fifty years in the Journal of the Danish Medical Association (Danish: Ugeskrift for Læger). Dan Med J. 2012;59(3):A4390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pile K. Publish or perish. Int J Rheum Dis. 2009;12(3):183-185. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2009.01408.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fabbri LM. Rank injustice and academic promotion. Lancet. 1987;2(8563):860. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(87)91051-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kenna H, Swanson AN, Roberts LW. Evidence-based metrics and other multidimensional considerations in promotion or tenure evaluations in academic psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(4):467-470. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0741-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez SA, Svider PF, Misra P, Bhagat N, Langer PD, Eloy JA. Gender differences in promotion and scholarly impact: an analysis of 1460 academic ophthalmologists. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):851-859. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaykaran YP, Yadav P, Chavda N, Kantharia ND. Survey of ‘instructions to authors’ of Indian medical journals for reporting of ethics and authorship criteria. Indian J Med Ethics. 2011;8(1):36-38. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2011.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wager E. Do medical journals provide clear and consistent guidelines on authorship? MedGenMed. 2007;9(3):16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samad AKT, Siddiqui AA. Do the instructions to authors of Pakistani medical journals convey adequate guidance for authorship criteria? Pak J Med Sci. 2009;25(6):879-882. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson TP, Wislar JS. Response rates and nonresponse errors in surveys. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1805-1806. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]