Abstract

Objectives:

Previous studies have shown that brief mindfulness trainings can have significant analgesic effects. However, the effects of the various components of mindfulness on pain analgesia are not well understood. The objective of this study was to examine the effects of two components of mindfulness interventions - attention and acceptance on pain analgesia.

Methods:

One hundred and nineteen healthy college students without prior mindfulness experience underwent a cold pressor test to measure pain tolerance before and after the training. Pain intensity, tolerance, distress, threshold and endurance time were also tested. Participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: (1) acceptance of pain, (2) attention to pain, (3) acceptance of and attention to pain, or (4) control.

Results:

The results showed that both the acceptance strategy and the combined acceptance and attention group increased pain endurance and tolerance after training. Furthermore, acceptance group had longer pain endurance time and tolerance time than attention group and control group.

Conclusions:

These results suggest that acceptance of pain is more important than attention to pain. Study limitations and future research directions are discussed.

Keywords: mindfulness, acceptance, attention, pain, mechanism, short-term

Mindfulness is a mental state that can be achieved by focusing one’s conscious awareness purposefully and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of the moment by moment experience (Kabat-Zinn 2003; Zeidan et al., 2012). Previous studies have shown that mindfulness-based therapies are particularly promising for treating pain (Grant 2014; Zeidan and Vago 2016). Some studies suggest that even short-term mindfulness training can have significant analgesic effects (Liu et al., 2013; Zeidan et al., 2010). For example, Liu et al. (2013) demonstrated that a 15-minute mindfulness practice improved participants’ pain tolerance and reduced distress in a cold pressor test. Despite these promising results, the underlying mechanisms are not well understood.

Short-term mindfulness meditation has been found to relieve pain through a number of possible mechanisms including acceptance, coping, and reappraisal. For example, Kingston et al. (2007) found that six, 1-h mindfulness meditation training sessions significantly increased pain tolerance during the cold pressor test as compared to a control group. The authors postulated that mindfulness modifies the subjective pain experience by enhancing acceptance and coping. In another study, Zeidan et al. (2010) found that three days of a brief mindfulness meditation training (20 min/day) significantly reduced pain intensity as compared to math distraction and relaxation. The authors postulated that mindfulness mediation, but not distraction, may regulate the affective appraisal system. Taken together, these behavioral studies provide evidence that mindfulness meditation practice can change the manner in which noxious stimuli are experienced.

Despite these advances, relatively little research links the mindfulness components with the mindfulness related pain relief. Contemporary conceptualizations of mindfulness emphasize two components: (1) attention, defined as ongoing awareness of present moment sensory and perceptual experiences; and (2) acceptance, defined as a mental attitude of nonjudgment, openness, receptivity, and equanimity toward internal and external experiences (Baer, 2009; Bishop et al., 2004; Lindsay & Creswell, 2017). Lindsay and Creswell’s (2017) Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT) posits that paying attention to one’s experiences trains attentional processes and enhances these experiences leading to both greater negative and positive experiences, as they occur in the present moment. Acceptance further modifies the way one relates to the content of the experience, thereby regulating the reactivity to this affective experience. According to MAT, without concomitant training in acceptance, development in attention may increase attention to salient distressing stimuli, intensifying the pain intensity, whereas attention and acceptance is expected to improve the pain tolerance and reduce distress induced by pain. However, MAT mainly describes mechanisms of mindfulness for cognition, affect, stress and health. Much less is known about the effects of attention and acceptance components on pain analgesia. Furthermore, MAT does not discuss the effect of acceptance on pain as an individual strategy.

It has been shown that paying close attention to the pain sensations may increase pain intensity (Grant and Rainville 2009; McCaul and Haugtvedt 1982). For example, McCaul and Haugtvedt (1982) found that during a 4-minute cold pressor task the attention strategy increased pain intensity in the first two minutes. Grant and Rainville (2009) found that novices increased the pain intensity during the concentration meditation (focusing their attention on the pain stimulation).

In contrast, compared with other strategies (e.g., distraction, suppression, spontaneous coping, placebo, and reappraisal), the acceptance strategy can significantly increase people’s tolerance of pain, (Keogh, Bond, Hanmer, & Tilston, 2005; Kohl, Rief, & Glombiewski, 2012; Kohl, Rief, & Glombiewski, 2013; Masedo & Esteve, 2007; McMullen et al., 2008). For example, McMullen et al. (2008) found that subjects applying the acceptance strategy could increase tolerance for electric pain more than subjects using the distraction strategy. Kohl et al. (2013) reported that acceptance was superior to reappraisal at increasing tolerance for experimentally induced pain. A meta-analysis showed a small to medium effect size suggesting that acceptance strategies were superior to other strategies for pain tolerance (Kohl, Rief, & Glombiewski, 2012).

Interestingly, although mere attention increased the pain intensity, the combination of attention and acceptance may increase the pain tolerance. In a previous study, pain intensity during the concentration meditation increased in novice meditators. However, it should be noted that the pain intensity decreased in the same condition for experts (Grant and Rainville, 2009). Compared to novices, the expert meditators scored higher on attention (observation) and acceptance (non-reactivity), which were associated with lower pain sensitivity (Grant, 2014).

We examined the differential effects of attention and acceptance in mindfulness intervention for pain. We employed a short-term attention training, acceptance training, and a combined attention and acceptance training to investigate the effect of these strategies on the pain experience. In this study, we explored pain threshold and distress outcomes, with primary predictions centered on pain intensity, tolerance, and endurance. Based on the aforementioned studies, we predict that if novice mediators are only trained to pay attention to pain, pain intensity will increase. However, those who utilize an acceptance strategy are expected to have greater pain tolerance than attention training and control. For participants who are trained in both, acceptance and attention strategies, we hypothesize that acceptance will help participants to tolerate pain for longer and that it will result in less pain intensity and distress.

Method

Participants

A power analysis using the software G*Power 3.1 revealed that 76 participants were needed to detect a small to medium effect size (f = 0.25) of a Time × Group interaction with 95% power (ANOVA: repeated measures, within – between interaction; at the 0.05 significance level; see Faul et al., 2007). The expected effect size was based on a recent meta-analysis of mindfulness intervention (Bohlmeijer et al., 2010) and a recent review of acceptance-based treatments (including mainly mindfulness studies) in pain (Veehof et al., 2011). Because more than 30% of participants were excluded from our earlier study with pain task (Liu et al., 2013), we oversampled and recruited 119 university students to participate in this experiment. Ninety participants were undergraduates, and 29 were graduate students (88 of them were females). The mean age was 21.08 years (SD: 2.05; range: 18–30). Exclusion criteria included a history of chronic pain, frostbite on the left hand, heart disease, prior meditation experience, and Raynaud’s disease (i.e., excessively reduced blood flow in response to cold or emotional stress). All participants signed informed consent forms prior to participation. The experimental protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the College of Psychology, Capital Normal University.

Procedure

Participants underwent the cold pressor task at baseline. Then, they were randomized into four groups: pain-attention group, pain-acceptance group, combined acceptance and attention group, and control group. After the training or waiting period, participants were tested with the cold pressor task again at post-test. The instructions of the four groups were as follows:

Participants in the pain-attention group were instructed to pay close attention to the situation. During the brief training, they were instructed to close their eyes and pay attention to their breath, continuously attending to each breathing cycle as well as the pause between breathing cycles. If their attention was drawn away, participants were asked to gently bring their attention back and refocus on their breathing (Frewen et al., 2007). They practiced for 10 breathing cycles. The experimenter then asked participants about their experience and provided corrective information as necessary. The experimenter then left the room and participants practiced the breathing-focused meditation for 15 minutes. To enhance the effect of the practice and prevent participants from becoming too drowsy or falling asleep, a bell rang every 90 s signaling the participants to reflect on whether they were fully concentrated on their breathing and to refocus their attention if necessary. Participants were then asked to rate how many times they were breathing on their breath from 0–5. This Meditation Breath Attention Score (MBAS) has been used in previous studies (Frewen et al., 2007, 2011; Wang et al., 2017). After the 15-minute practice, participants reflected back on the practice and wrote down how they felt. Following this training, participants were asked to use the same strategy to cope with the pain induced by the cold pressor task, such as to focus their attention on the quality of the pain sensations (e.g. sharp or dull) and on any changes in pain intensity. If distracted, participants were asked to refocus their attention on the pain.

Participants in the pain-acceptance group were instructed to accept their thoughts and feelings without being controlled by them, in line with the acceptance intervention by McMullen et al. (2008). During the training, participants were asked to recall three thoughts related to the desire to take their hands out of the ice water during the pre-test (e.g., “I can’t stand this pain”). Then, subjects recited loudly “I can’t walk” while walking around the testing room (7 m × 2.5 m) three times. The purpose of this exercise was to illustrate to the subjects that they could continue a task, including the pain-inducing cold pressor task, while noticing pain and pain-related thoughts, regardless of the content of their thoughts and feelings. Moreover, adopting a radical acceptance approach (e.g., Hayes et al., 1999), participants were asked to compare the cold pressor task with crossing a muddy swamp; the best way to cross the swamp is to just notice any unpleasant thoughts and feelings and carry on walking toward the other side of the swamp, despite any negative thoughts or impulses to stop (Hayes et al., 1999). Participants were then asked to describe this acceptance process by writing and reflecting upon it. Finally, participants were asked to adopt the following general strategy for the cold pressor task: “When there are negative thoughts or feelings, take an open and accepting attitude; don’t be controlled by them, just proceed with the task.”

Participants in the combined acceptance and attention group were instructed to use both the acceptance and attention strategies to cope with the pain. The order in which these strategies were taught was counter-balanced. The instructions of this group for the cold pressor task were as follows: “Focus your attention on the pain in the hand, and continuously observe the pain over time and at different locations in the hand. If you get distracted, gently redirect the attention back to the pain. Should there be any negative thoughts or feelings, take an open and accepting attitude and don’t be controlled by them.”

Participants in the control group were given neutral reading materials in general science. After the reading period, participants were provided with general instructions for the cold pressor task (i.e., to put the hand in the water and to leave it in as long as possible).

The entire instruction time lasted 30 minutes per condition. To ensure that the duration of the three conditions was identical, the pain-attention group and the pain-acceptance group also received neutral reading materials in general science in addition to reading materials describing the specific instructions. The combined acceptance and attention group received reading materials from both the pain-attention group and the pain-acceptance group. In all three groups, the order of the reading materials was balanced across the subjects.

Measures

The cold pressor task is a widely used, reliable, and valid task to induce pain. As part of this task, participants are asked to submerge their hand in ice-cold water in order to induce pain (Keogh et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2013; Mitchell et al., 2004). The task includes two rectangular shaped plastic containers (39 cm × 30 cm × 12 cm). One of the containers is filled with warm water at 37 degrees Celsius, and the other is filled with iced water at 5 degrees Celsius. The ice is wrapped in a plastic net attached to the side of the container in order to prevent the subjects’ hand from touching the ice directly. A small pump constantly circulates the cold water to keep its temperature within the range of 5–6 degrees Celsius. The instructions for the cold pressor task were given through a set of PowerPoint slides. The cold pressor task consisted of two stages.

For the initial baseline period, participants are asked to put their left hands up to the wrist into the warm water (37 degrees Celsius) for 2 minutes. After 2 minutes, a sound signaled the participants to immerse their hand in the cold water. For the ice water period, participants pressed the space bar on a computer when they started feeling pain, and then pressed the space bar again when they needed to take their hands out because the pain became intolerable. Regardless of whether participants pressed the space bar a second time, the experimenter instructed subjects to take their hands out of the water after 5 minutes elapsed (Mitchell et al., 2004). Immediately after participants took their hands out of the ice water, the following measures were taken:

Pain intensity.

Subjective pain was assessed using a visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from 0 = “no pain” to 10 = “the worst pain”. Participants were asked to report these ratings verbally.

Pain distress.

Subjective distress was assessed using a VAS on a scale from 0 = “no distress” to 10 = “the worst distress” verbally.

Threshold.

The time interval from when participants submerged their hands in the ice water to when they pressed the space bar to indicate that they began to feel pain.

Pain tolerance.

The time interval from when participants submerged their hands in the ice water to when they took the hands out of the water (Feldner et al., 2006).

Pain endurance.

The difference between pain threshold and tolerance times served as an index of participants’ pain endurance (Feldner et al., 2006).

Participants were encouraged to keep their hands in the water for as long as they could but were allowed to terminate the task at any time for any reason.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 19.0. Group differences in gender and education were checked with Chi-square tests. Baseline differences among groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA tests. Pain intensity, endurance time and tolerance time were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVAs (within group variable: pre-test, post-test; between group variable: groups). For ANOVAs, a Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied if data failed the Mauchly’s test of sphericity. A Bonferroni correction was applied as a post-hoc test. Partial eta square (η2p) and Cohen’s d were used as effect size measures. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

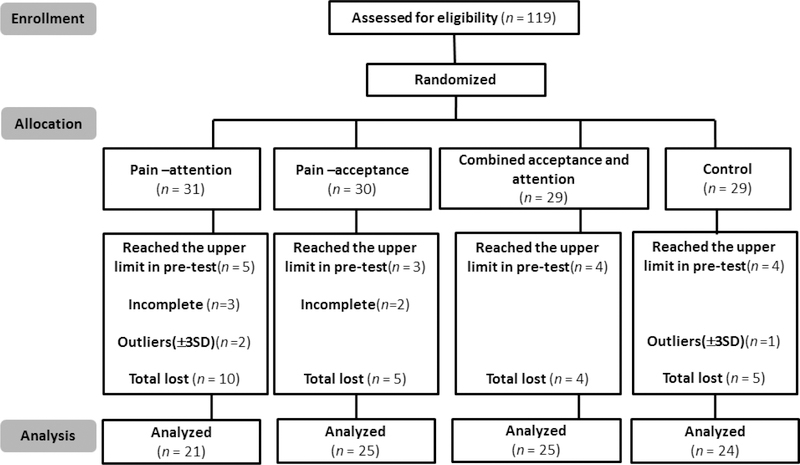

Of the 119 participants, 24 were removed from the analyses for the reasons below. Given ethical considerations, the maximum time was set at 5 minutes (Mitchell et al., 2004). Sixteen of the participants (attention group: 5; acceptance group: 3; combined group: 4; control group: 4) reached the upper time limit (5 minutes) at the pre-test. Therefore, we could not obtain their pain tolerance time data and pain intensity measures (Hayes et al., 1999; Masedo & Esteve, 2007). Furthermore, 5 participants did not follow the experimental procedure and took their hands out of the water without stopping the timer. Finally, 3 participants (attention group: 2; control group: 1) were outliers (out of ± 3SD); 2 outliers rated their unbearable pain feelings as 2 (1-no pain, 10-worst pain; Mean score of all the participants at the pre-test and post-test were 7.29 and 8.05), and another withdrew his hand at the 11th second (Mean tolerance time of all the participants in the pre-test and post-test were 109.76s and 94.09s). All results remained consistent, regardless of whether these participants were included in analyses. The total sample for the analyses consisted of 95 participants (Figure 1). The average age of the sample was 21.03 years (range: 18–30, SD = 2.09), and 21 of them were males (22.11%) and 74 were females (77.89%).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram showing trial enrollment, allocation,ans analysis.

As shown in Figure 1, there were no significant differences in gender distribution, χ2(3) = 3.135, p = 0.371, or educational background, χ2 (3) =1.872, p = 0.599. Similarly, no pre-test difference was observed in any of the other demographic variables, Fpain (3, 91) = 1.257, p = 0.294; Ftolerance (3, 91) = 1.712, p = 0.170, Fdistress (3, 91) = 0.085, p = 0.968; Fthreshold (3, 91) = 0.952, p = 0.419; Fendurance (3, 91) = 1.783, p = 0.156 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the pre- and post-test for each group

| Pain-attention (N=21) | Pain-acceptance (N=25) | Acceptance and Attention (N=25) | Control (N=24) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Age | 20.57 (1.75) | 21.60 (2.81) | 20.84 (1.70) | 21.04 (1.81) | ||||

| Intensity | 7.29 (2.15) | 8.05 (2.16) | 7.88 (1.87) | 7.17 (2.46) | 8.32 (2.08) | 8.52 (1.75) | 8.21 (1.72) | 7.50 (2.06) |

| Distress | 7.05 (2.60) | 7.19 (2.36) | 6.75 (2.07) | 6.21 (2.93) | 6.76 (2.18) | 6.68 (2.70) | 6.75 (2.54) | 6.21 (2.57) |

| Threshold | 16.79 (9.89) | 16.52 (7.96) | 15.37 (10.67) | 17.39 (12.26) | 16.52 (13.69) | 15.48 (13.57) | 21.62 (19.19) | 19.06 (13.70) |

| Endurance time | 64.91 (40.65) | 64.10 (43.06) | 91.76 (68.25) | 148.01 (105.02) | 66.89 (35.12) | 107.99 (74.54) | 88.14 (51.72) | 75.03 (51.95) |

| Tolerance time | 81.71 (44.26) | 80.63 (45.91) | 107.13 (70.11) | 165.40 (109.39) | 83.41 (41.25) | 123.47 (77.20) | 109.76 (60.31) | 94.09 (60.05) |

Note: the numbers in parentheses are standard deviations

Pain Intensity.

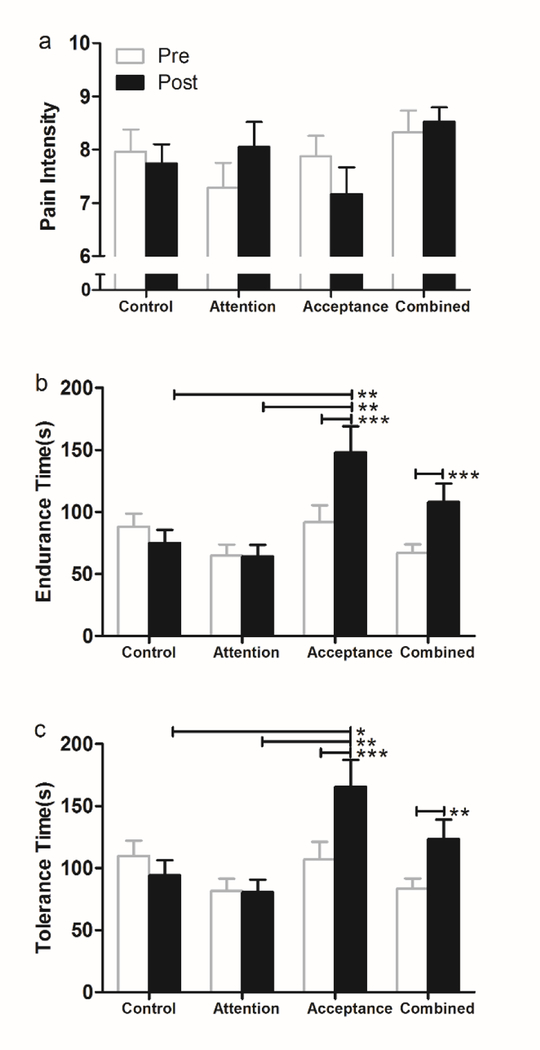

There were no main effects of Time, F (1, 91) = 0.304, p = 0.583, η2p = 0.003, or Group, F (3, 91) = 1.262, p = 0.292, η2p = 0.040, but we observed a significant Time × Group interaction effect, F (3, 91) = 2.975, p = 0.036, η2p = 0.090. Post-hoc paired t tests revealed that pain intensity did not significantly change from pre- to post-intervention in all groups (Means ± SDs of attention group: 7.29 ± 2.15 vs. 8.04 ± 2.16, p = 0.083; acceptance group: 7.88 ±1.87 vs. 7.16 ± 2.46, p = 0.085; combined group: 8.32± 2.08 vs. 8.52 ± 1.36, p = 0.617; control group: 8.21 ± 1.72 vs. 7.50 ± 2.04, p = 0.085). No significant between-group differences were found (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Mean ± SEM scores for pain intensity, endurance time and tolerance time in each condition. (a) no significant changes in pain intensity ratings. (b) Within group analysis showed that both the acceptance group and the combined group significantly increased the pain endurance time (p < 0.001). Between group analysis revealed that in the post-test acceptance group significantly increased the endurance time than attention group (p = 0.001) as well as control group (p = 0.005). (c) Within group analysis showed that both the acceptance group and the combined group significantly increased the pain tolerance time (acceptance group: p < 0.001; combined group: p = 0.001). Between group analysis revealed that in the post-test acceptance group significantly increased the tolerance time than attention group (p = 0.002) as well as control group (p = 0.012). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. SEM = standard error of the mean.

Pain endurance.

There was a significant main effect of Time, F (1, 91) = 13.569, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.130, and Group, F (3, 91) = 3.853, p = 0.012, η2p = 0.113. The Time × Group interaction effect was also significant, F (3, 91) = 8.684, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.223. Post hoc paired t test showed that both the acceptance group and the combined group significantly increased the pain endurance time (acceptance group: 91.76 ± 68.25 vs. 148.01 ± 105.02, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.635; combined group: 66.89±35.12 vs.107.99 ± 74.54, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.705). Between group analysis revealed that in the post-test acceptance group significantly increased the endurance time than attention group (148.01 ± 105.02 vs. 64.10 ± 43.06, p = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.045) as well as control group (148.01 ± 105.02 vs. 75.03 ± 51.95, p = 0.005, Cohen’s d = 0.881, Figure 2b).

Pain Tolerance.

There were significant main effects of Time, F (1, 91) = 11.659, p = 0.001, η2p = 0.114, and Group, F (3, 91) = 3.227, p = 0.026, η2p = 0.096. The Time × Group interaction effect was also significant, F (3, 91) = 8.526, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.219. Post hoc paired t test showed that both the acceptance group and the combined group significantly increased the pain tolerance time (acceptance group: 107.13 ± 70.11 vs. 165.40 ± 109.39, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.634; combined group: 83.41±41.25 vs.123.47 ± 77.20, p = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.647). Between group analysis revealed that in the post-test acceptance group significantly increased the tolerance time than attention group (165.40 ± 109.39 vs. 80.63 ± 45.91, p = 0.002, Cohen’s d = 1.011) as well as control group (165.40 ± 109.39 vs. 94.09 ± 60.05, p = 0.012, Cohen’s d = 0.808, Figure 2c).

Pain distress and Threshold.

None of the main or interaction effects reached statistical significance (see Table 1).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the differential effects of two components of mindfulness intervention - attention and acceptance strategies - on pain analgesia. Pain intensity, endurance time and tolerance time are main outcomes. The results showed both pain-acceptance and combined acceptance-attention strategies increased pain tolerance and endurance. Furthermore, acceptance group had longer pain endurance time and tolerance time than attention group and control group. These results suggest that acceptance of pain is more important than attention to pain.

In line with other studies and our hypotheses, we found that the acceptance strategy was effective for increasing pain tolerance, which is consistent with previous studies (Kingston et al., 2007; Kohl et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2013; Masedo & Esteve, 2007; McMullen et al., 2008). In the context of our study, acceptance means actively embracing unpleasant physical and psychological experiences while acting consistent with one’s goals (Masedo and Esteve 2007). When employing such an acceptance strategy, participants showed more tolerance to pain and less avoidance to the pain stimulus, which is consisted with other studies (Branstetter-Rost et al., 2009; Gutiérrez et al., 2004; Keogh et al., 2005). Consistent with the result of a meta-analysis, the acceptance strategy can significantly increase people’s tolerance of pain, but has no significant effect on the intensity or distress the subjects experienced (Kohl, Rief, & Glombiewski, 2012). This is in line with ACT, suggesting that reducing pain sensations is not the aim of ACT. Rather, acceptance in ACT encourages people to act in ways that are not determined by their pain experience, but rather in line with their values, so that patients are willing to tolerate pain for longer despite their thoughts and unpleasant feelings (Branstetter-Rost et al., 2009; Gao, Curtiss, Liu, & Hofmann, 2018; Gutiérrez et al., 2004; McCracken et al., 2005).

This study failed to support the hypothesis that attention would increase pain intensity. The results of the current study suggest that attention skill can neither increase nor decrease an individual’s pain intensity. It should be noted that the attention strategy group in our study differed from that in other investigations in a number of important ways. We did not instruct subjects to keep their hands in the ice water for long enough to observe a change in pain intensity as in the McCaul (1982) study. Moreover, we did not instruct subjects to focus on other tasks, such as one’s breath (Forsyth and Hayes 2014). Instead, we asked participants to focus on their pain experience because in our opinion, it is difficult to separate the confounding component (e.g. distraction) from the attention to breath under the pain condition (Zeidan et al., 2010), whereas attention to the pain sensations can rule out the possibility.

Our results showed that the combined acceptance and attention strategy did, indeed, show relatively greater pain tolerance, which is consistent with other studies (Liu et al., 2013; Zeidan et al., 2010, 2012). However, the combined training did not prove to be a better intervention than the acceptance-only strategy in the other indicators of the pain experience. The unanticipated findings may be due to the brief duration of submersion time for novices, which was only about two minutes (127 s) at post-test. In fact, McCaul and Haugtvedt (1982) showed that the attention strategy was only superior when subjects tolerated pain for more than 2 minutes. Below the 2-minute time frame, attention increased the pain intensity for novices. It would be interesting to investigate the analgesic effect of attention, acceptance, and combine training during longer periods of the cold pressure task.

The study had some limitations. First, although we matched the training in length as much as possible, the combined group received twice the amount of active training as the other training groups, which limits the conclusions that can be drawn from these comparisons. However, it also suggests that a more intensive training does not seem to increase pain tolerance in this brief training context. Second, for the attention group and the acceptance group, half of the subjects first received the training program and then the reading material, the other half of the subjects received the reverse order. Therefore, only half of the subjects immediately participated in the post-test, which might have attenuated the effect of the intervention. Third, the strategy for training attention by counting breaths may be somewhat difficult to translate into the distressing experience of paying attention to pain sensations; we did not directly train participants to pay attention to their unpleasant physical sensation and observe the change of the sensation during the training. Moreover, it is quite possible that demand characteristics of the experiment might have influenced the results (Hayes et al., 1999, McMullen et al., 2008). The brief intervention may result in state-like changes. In fact, it had been shown that such demand characteristics can have a positive effect on cold pressor performance (Roche, Forsyth, & Maher, 2007). Despite these limitations, the current study adds to the literature by examining the process of mindfulness training on pain. Our results suggest that acceptance of pain is more important than paying attention to it during the early stage of pain management.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Johann D’Souza for the proof-reading work.

Funding sources

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (Project 31271114).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Hofmann receives financial support from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (as part of the Humboldt Prize), NIH/NCCIH (R01AT007257), NIH/NIMH (R01MH099021, U01MH108168), and the James S. McDonnell Foundation 21st Century Science Initiative in Understanding Human Cognition – Special Initiative. He receives compensation for his work as an advisor from the Palo Alto Health Sciences and for his work as a Subject Matter Expert from John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and SilverCloud Health, Inc. He also receives royalties and payments for his editorial work from various publishers.

Ethics Statement

The study received ethical approval from the Academic Committee of College of Psychology, Capital Normal University. No adverse events were reported in this study.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

References

- Baer RA (2009). Self-focused attention and mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based treatment. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38 Suppl 1, 15–20, doi: 10.1080/16506070902980703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, et al. (2004). Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241, doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmeijer E, Prenger R, Taal E, & Cuijpers P (2010). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on mental health of adults with a chronic medical disease: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 68(6), 539–544, doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branstetter-Rost A, Cushing C, & Douleh T (2009). Personal values and pain tolerance: Does a values intervention add to acceptance? The Journal of Pain, 10(8), 887–892, doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, & Buchner A (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191, doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldner MT, Hekmat H, Zvolensky MJ, Vowles KE, Secrist Z, & Leen-Feldner EW (2006). The role of experiential avoidance in acute pain tolerance: a laboratory test. Journal of Behaviour Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 37(2), 146–158, doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth L, & Hayes LL (2014). The Effects of Acceptance of Thoughts, Mindful Awareness of Breathing, and Spontaneous Coping on an Experimentally Induced Pain Task. The Psychological Record, 64(3), 447–455, doi: 10.1007/s40732-014-0010-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frewen PA, Evans EM, Maraj N, Dozois DJA, & Partridge K (2007). Letting Go: Mindfulness and Negative Automatic Thinking. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32(6), 758–774, doi: 10.1007/s10608-007-9142-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frewen PA, Lundberg E, MacKinley J, & Wrath A (2011). Assessment of response to mindfulness meditation: Meditation breath attention scores in association with subjective measures of state and trait mindfulness and difficulty letting go of depressive cognition. Mindfulness, 2(4), 254–269, doi: 10.1007/s12671-011-0069-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Curtiss J, Liu X, & Hofmann S (2018). Differential Treatment Mechanisms in Mindfulness Meditation and Progressive Muscle Relaxation. Mindfulness, 9(4), 1268–1279. [Google Scholar]

- Grant JA (2014). Meditative analgesia: the current state of the field. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1307, 55–63, doi: 10.1111/nyas.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JA, & Rainville P (2009). Pain sensitivity and analgesic effects of mindful states in Zen meditators: A cross-sectional study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(1), 106–114, doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818f52ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez O, Luciano C, Rodríguez M, & Fink BC (2004). Comparison between an acceptance-based and a cognitive-control-based protocol for coping with pain. Behavior Therapy, 35(4), 767–783. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, & Wilson KG (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (2003). Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Context: Past, Present, and Future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156, doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh E, Bond FW, Hanmer R, & Tilston J (2005). Comparing acceptance- and control-based coping instructions on the cold-pressor pain experiences of healthy men and women. European Journal of Pain, 9(5), 591–598, doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston J, Chadwick P, Meron D, & Skinner TC (2007). A pilot randomized control trial investigating the effect of mindfulness practice on pain tolerance, psychological well-being, and physiological activity. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 62(3), 297–300, doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl A, Rief W, & Glombiewski JA (2012). How effective are acceptance strategies? A meta-analytic review of experimental results. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 43(4), 988–1001, doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl A, Rief W, & Glombiewski JA (2013). Acceptance, cognitive restructuring, and distraction as coping strategies for acute pain. Journal of Pain, 14(3), 305–315, doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay EK, & Creswell JD (2017). Mechanisms of mindfulness training: Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT). Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 48–59, doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Wang S, Chang S, Chen W, & Si M (2013). Effect of Brief Mindfulness Intervention on Tolerance and Distress of Pain Induced by Cold-Pressor Task. Stress and Health, 29(3), 199–204, doi: 10.1002/smi.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masedo AI, & Esteve MR (2007). Effects of suppression, acceptance and spontaneous coping on pain tolerance, pain intensity and distress. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(2), 199–209, doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul KD, & Haugtvedt C (1982). Attention, distraction, and cold-pressor pain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(1), 154–162, doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.43.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken LM, Vowles KE, & Eccleston C (2005). Acceptance-based treatment for persons with complex, long standing chronic pain: A preliminary analysis of treatment outcome in comparison to a waiting phase. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(10), 1335–1346, doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen J, Barnes-Holmes D, Barnes-Holmes Y, Stewart I, Luciano C, & Cochrane A (2008). Acceptance versus distraction: brief instructions, metaphors and exercises in increasing tolerance for self-delivered electric shocks. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(1), 122–129, doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell LA, MacDonald RA, & Brodie EE (2004). Temperature and the cold pressor test. Journal of Pain, 5(4), 233–237, doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche B, Forsyth JP, & Maher E (2007). The Impact of Demand Characteristics on Brief Acceptance- and Control-Based Interventions for Pain Tolerance. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 14(4), 381–393. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2006.10.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Veehof MM, Oskam MJ, Schreurs KM, & Bohlmeijer ET (2011). Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain, 152(3), 533–542, doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Xu W, Zhuang C, & Liu X (2017). Does Mind Wandering Mediate the Association Between Mindfulness and Negative Mood? A Preliminary Study. Psychological Reports, 120(1), 118–129, doi: 10.1177/0033294116686036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidan F, Gordon NS, Merchant J, & Goolkasian P (2010). The effects of brief mindfulness meditation training on experimentally induced pain. Journal of Pain, 11(3), 199–209, doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidan F, Grant JA, Brown CA, McHaffie JG, & Coghill RC (2012). Mindfulness meditation-related pain relief: evidence for unique brain mechanisms in the regulation of pain. Neuroscience Letters, 520(2), 165–173, doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.03.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidan F, & Vago DR (2016). Mindfulness meditation-based pain relief: a mechanistic account. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1373(1), 114–127, doi: 10.1111/nyas.13153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.