Abstract

Akt1–3 (Akt) are a subset of the AGC protein Ser/Thr kinase family and play important roles in cell growth, metabolic regulation, cancer and other diseases. We describe some of the roles of Akt in cell signaling and the biochemical and structural mechanisms of regulation of Akt catalysis by the phospholipid PIP3 and by phosphorylation. Recent findings highlight a diverse set of strategies to control Akt catalytic activity to ensure its normal biological functions.

Background biology of Akt and AGC kinases

Discovery of the Akt subfamily of protein kinases can be traced to pioneering experiments from over three decades ago involving the identification of an oncogene of the AKT8 retrovirus [1]. The Akt subfamily consists of three protein Ser/Thr kinases, Akt1, Akt2, and Akt3 which are closely related in sequence and structure [2]. Akt1–3 are members of the protein kinase superfamily which consists of over 500 genes in humans and these enzymes catalyze the direct transfer of the gamma-phosphoryl group from ATP to the hydroxyl group of a Ser, Thr, or Tyr sidechain through a dissociative transition state [3,4]. There are about 400 protein Ser/Thr kinases in the kinome and among these, the AGC kinases which include Akt1–3 represent a major family [5].

The AGC family kinases, named after protein kinase A, protein kinase G, and protein kinase C, include about 60 enzymes that can be further divided into 16 sub-families [6]. The best characterized member of these enzymes, protein kinase A, also known as the cyclic AMP dependent protein kinase has served as the paradigm for our understanding of AGC kinases. Many of the AGC kinases including protein kinase A, protein kinase C, Akt1–3, PDK1, SGK, GRK, LATS1/2 have been linked to major cell signal transduction pathways allowing cells to respond to extracellular stimuli [6]. Dysregulation of these enzymes are hallmarks of many clinical disorders including cardiovascular diseases, neurologic diseases, inflammation, and cancer [7] and inhibitors are under development to target protein kinases [8].

The AGC kinases all possess a conserved kinase domain composed of an N-terminal lobe involved in ATP binding and a C-lobe that participates in peptide/protein substrate recognition [9•]. Most AGC kinase domains include an activation loop that is typically phosphorylated by an upstream kinase, often PDK1, and one or two C-terminal phosphorylation sites that can regulate activity [10]. AGC enzymes are usually ‘basophilic’ kinases and prefer substrates with Lys/Arg residues N-terminal to the Ser/Thr that is targeted [11].

Akt1–3 are special examples of AGC kinases in being comprised of an N-terminal PH (pleckstrin homology) domain which can bind the phospholipid phosphatidyl-inositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3), a centrally located kinase domain, and a regulatory C-terminal tail [2]. Akt1 (focused on here as the best studied representative) is activated indirectly by insulin and other growth factors and is downstream of the phospholipid kinase PI3-K which converts the membrane embedded substrate phosphatidyl-inositol-4,5-diphosphate (PIP2) to PIP3 [12,13] (Figure 1). The production of PIP3 drives the recruitment of PDK1 and Akt1 to membranes via their PH domains where Akt1 can be phosphorylated by PDK1 on its activation loop (Thr308) [14,15]. In the context of this activation, Akt1 is also phosphorylated by the mTORC2 kinase complex on its C-terminus (Ser473) [16]. Levels of PIP3 are tightly controlled by the lipid phosphatase PTEN which transforms PIP3 into PIP2 [17]. Activating mutations in PI3-K isoforms and loss of function mutations are commonly observed in cancer, underscoring the importance of maintaining PIP3 membrane concentrations in a narrow window to prevent unregulated cell proliferation [18]. Beyond this canonical PIP3 activation mechanism, Akt1–3 have been reported to be regulated by a wide swathe of PTMs and by mutation [2].

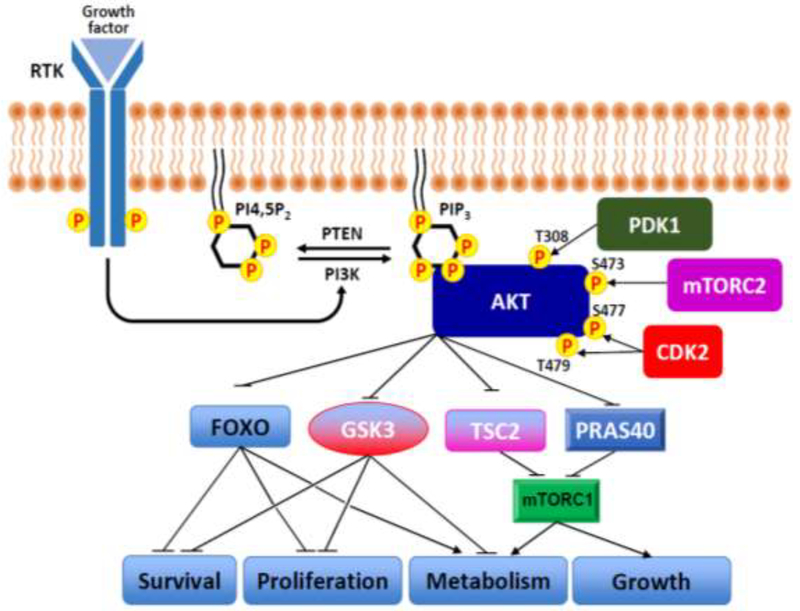

Figure 1. PI3-K/Akt signaling pathway.

Upon activation by growth factors, PI3-K recruitment to a receptor tyrosine kinase leads to a transient increase in PIP3 levels. This phospholipid serves as an anchor point to recruit Akt1 to the plasma membrane where it undergoes phosphorylation at residues Thr308 and Ser473 by PDK1 and mTORC2, respectively. In addition, the more recently identified dual phosphorylations at residues Ser477 and Thr479 by Cdk2 that may occur in the cell nucleus can be an alternative mechanism for activating Akt1. Once activated, Akt1–3 phosphorylate downstream substrates that are involved in a diverse of cellular functions. Several of the well-characterized Akt1–3 substrates including FoxO, GSK3, TSC2 and PRAS40 are shown. P indicates phosphorylation.

Akt substrates

From numerous studies over the past two decades, over 100 protein substrates of Akt1–3 have been reported, although the extent of validation of these has been variable [19]. Since there are many cellular kinases that are activated with growth factor receptor stimulation, it is difficult to establish direct Akt1–3 substrates. However, using a rigorous combination of genetic, pharmacological, structure-based, and kinetic assays, there are approximately twenty substrates that can be assigned to be phosphorylated by Akt1–3 with high confidence [19,20•]. The consensus sequence for Akt1–3 substrates is R-X-R-X-X-S/T-ϕ where X is any amino acid and ϕ is a large hydrophobic residue [19]. Some of the well-accepted examples of these are GSK3, FoxO1/3, PRAS40, and TSC2 (Figure 1) [2].

Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) is inhibited by Akt1–3 phosphorylation of GSK3’s N-terminus, creating a pseudosubstrate motif that intramolecularly obstructs GSK3’s catalytic activity [21]. As active GSK3 is responsible for phosphorylating pro-growth protein substrates that are often then targeted for degradation, turning off GSK3 tends to enhance cell proliferation [22].

Forkhead O (FoxO) transcription factors help cells adapt to low insulin levels associated with fasting states by regulating gene expression [23]. Upon phosphorylation of FoxO1/3 by Akt1–3, these transcription factors are recruited out of the nucleus and are sequestered by binding to 14–3-3 adaptor proteins [24]. This inhibition of FoxO1/3 function helps promote cell cycle progression and altered metabolism [23]. Loss of FoxO1/3 phosphorylation in response to growth factors is a hallmark of genetic deletion of Akt1–2 in Hct116 colon cancer cells, providing strong evidence of the critical importance of this signaling mechanism [25].

Proline-rich Akt1–3 substrate 40 (PRAS40) is an inhibitory component of the mTORC1 complex [26]. Upon phosphorylation by Akt1–3, PRAS40’s negative influence on mTORC1 is removed [27]. Thus, mTORC1 can be activated. This is also the case with phosphorylation of the tuberous sclerosis protein 2 (TSC2). Phosphorylation of TSC2 prevents its GTPase promoting function toward the small G-protein Rheb [28,29]. An increase in GTP-bound Rheb then stimulates mTORC1 [30]. Stimulated mTORC1 drives cell proliferation.

Regulation of Akt by its PH domain

There are two major functions of the Akt1–3 PH domain that have been demonstrated. One is to bind phospholipid PIP3 leading to the recruitment of Akt1–3 to the plasma membrane [31]. Localization of Akt1–3 at the plasma membrane facilitates their proximity to mTORC2 and PDK1 where they are phosphorylated on their C-terminus and activation loop by these kinases, respectively [19]. In addition, the Akt1–3 PH domain binds to the kinase domain intramolecularly and helps maintain the kinase in an inactive state [32,33].

The structure of the Akt1 PH domain in complex with inositol 1,3,4,5-tetraphosphate (IP4) was determined by X-ray crystallography 17 years ago and it possesses a basic pocket where the 3-phosphate and 4-phosphate of IP4 make extensive interactions with the PH domain sidechains of Lys14, Arg23, Arg25, and Arg86 [34]. This structure explains why PI(3,4)P2 can bind to the Akt PH domain about as well as PIP3 in vesicle assays. Recent fluorescent binding studies of the Akt1 PH domain with soluble PIP3 and PI(3,4)P2 analogs have confirmed that they both have ~1 μM Kd values for the Akt PH domain [35••].

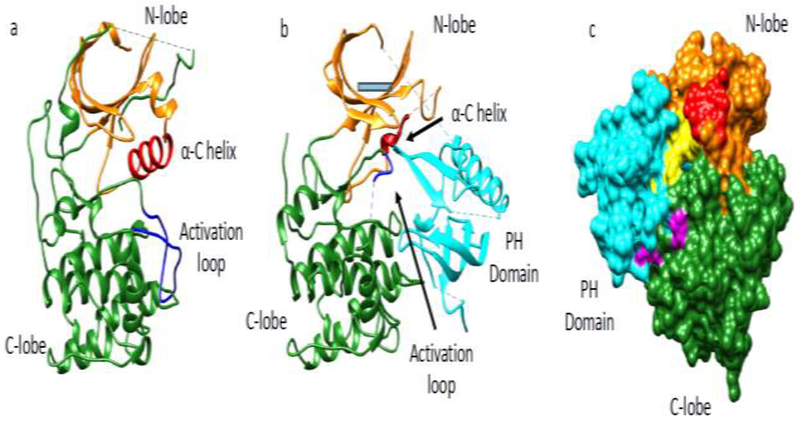

Crystallographic analysis of an unphosphorylated C-terminally truncated Akt1 form (aa1–443) that contains the PH and kinase domains in the presence of a small molecule allosteric inhibitor VIII has been reported (Figure 2) [36]. This structure depicts the interface of the PH-kinase interaction with the kinase domain in its inactive conformation with 1526 Å of buried surface area between the PH domain and the kinase domain (Figure 2). The inactive kinase conformation is marked by major conformational differences between the αC-helix and the activation loop highlighted in red and blue, respectively, in Figure 2 when comparing with the active conformation. The aa49–55 loop of the PH domain in this structure shows a different conformation compared with the free PH domain. The structure of the VIII-bound Akt1 suggests that binding of PIP3 to the PH domain might compete with the C-lobe of the kinase domain. This structure leads to the reasonable hypothesis that PIP3 binding to the PH domain of the full-length Akt1 can promote catalytic activity by displacing the PH domain from the kinase domain. In fact, such direct activation of purified Akt1 by PIP3 was reported in 2017 [37]. However, in 2018, this was re-evaluated by our lab and no such PIP3-mediated activation of Akt1 was observed [35••].

Figure 2. X-ray crystal structures of Akt1.

(a) Active conformation of Akt1 kinase domain aa144–480 (PDB: 3o96) where the N-lobe (orange), C-lobe (green), a-C helix (red) and activation loop (blue) are highlighted. (b) Inactive conformation of Akt31 aa1–443 (PDB: 6c0I) in complex with compound VIII (compound VIII not shown) highlighting the same features as in panel a. In addition, the PH domain (cyan) binds intramolecularly between the N and C lobes in the inactive state. (c) Surface representation of Akt1 in its inactive state (PDB: 6c0I) showing key residues in the interface of the PH and kinase domains. Potentially important residues mediating autoinhibition at the interface are highlighted: residues colored in yellow are part of the PH domain (E17, R23, N53, F55, L78, Q79, W80, T81) and residues in magenta are part of the kinase domain (V270, V271, L321, D323, D325, R328).

There were some methodologic differences which can account for the opposing findings. The 2017 effort used an indirect kinase assay which measures ADP product formation rather than phosphopeptide production so this 2017 study may have been monitoring ATPase rather than kinase activity [37]. In addition, the 2017 study did not measure kcat and Km values so the precise catalytic behavior was difficult to discern [37]. Perhaps most importantly, the 2017 study used very low (<1 mM, sub-physiologic) Mg2+ concentration and this low concentration would be expected to suppress catalytic turnover [37]. Mg2+ divalent ion is critical for protein kinase reactions [38]. Such low Mg2+ concentration in the 2017 study was said to be employed to avoid the impact of Mg2+ impeding PIP3-PH domain interaction [37]. However, we determined that 10 mM Mg2+ only slightly weakens PIP3-PH domain affinity in a fashion that should be negligible for assessing PIP3’s effects on kinase activity [35••]. Importantly, we also found that inactive (non-phosphorylated) and active (phosphorylated) forms of full-length Akt1 show similar affinity for soluble PIP3 [35••]. Based on a thermodynamic loop argument, it would have been expected that if PIP3 enhanced Akt1 kinase catalysis, it would show greater affinity for the PH domain in the active form of the enzyme. Thus, these recent studies suggest that the binding of PIP3 to Akt1–3 is principally important for membrane recruitment rather than allosteric activation. How then to rationalize the Akt1 crystal structure in complex with VIII [36]? We speculate that the presence of VIII may be promoting an Akt1 conformation that does not strictly correspond to the natural inactive state of Akt1–3, and hence VIII may obstruct PIP3 interaction with Akt1 in a manner that does not correspond to non-phosphorylated Akt1 without the small molecule.

Regulation of Akt by C-tail Ser/Thr phosphorylation

As mentioned, fully activated Akt1, like several AGC kinases, possesses phosphorylation on its activation loop (pThr308) and C-terminus (pSer473) as well as a constitutive phosphorylation at Thr450 thought to be important for stability [19]. The role of phosphorylation of the activation loop has long been deduced from a number of structures of AGC kinases including Akt1 as helping to fasten the activation loop to the two kinase lobes, facilitating the active conformation of the kinase domain [6]. The regulatory influence of pSer473 had until recently been understood to be exclusively related to promoting binding of the C-terminus to the kinase N-lobe, thereby driving the active conformation [2]. This model was based on crystal structures of the Akt1 kinase domain carrying the mutation S473D, thought to be a phospho-mimetic of pSer473. In these Akt1 structures, Asp473 makes two hydrogen bonds with sidechain and backbone with the N-lobe residue Gln218 [39]. However, this model does not explain how Ser473 and Asp473 Akt1 kinase domain forms show similar catalytic power [35••].

It has been challenging to study the impact of Akt1 phosphorylation at Ser473 using purified proteins because in vitro experiments with mTORC2 kinase have apparently not been successful at recapitulating its apparent cellular selectivity [30]. Two recent studies used chemical biology technologies to generate pSer473 phospho-forms, one involving unnatural amino mutagenesis by nonsense suppression [40] and the other expressed protein ligation (EPL) [35••]. EPL involves the chemoselective reaction between a recombinant protein C-terminal thioester and a synthetic peptide containing an N-terminal Cys [41]. EPL is conveniently applied to Akt1 since there is a natural Cys at aa460 which can be employed as the ligation site. Studies with pSer473-Akt produced by unnatural amino acid mutagenesis and EPL gave strikingly different results [35••,40]. Whereas the pSer473 form of Akt1 was a modest 4-fold more active compared with Ser473 based on experiments using unnatural amino acid mutagenesis Akt1 [40], the activity ratio of pSer473/Ser473 with EPL-generated Akt1 enzymes was about 500-fold [35••]. Close scrutiny of these two studies revealed that the overall activity of the pSer473 Akt1 form produced by unnatural amino acid mutagenesis was about equal to the Ser473 Akt1 form generated by EPL [35••,40]. We believe that the basis for these very different impacts stems from the sources of the recombinant proteins. Whereas the unnatural amino acid approach employed E. coli as the expression host [40], EPL involved an SF9 insect cell expression system to generate the major portion of Akt1 [35••]. Production in insect cells permits phosphorylation of Akt1 at its constitutive and stabilizing site Thr450 which does not occur in E. coli [35••], where yields of Akt1 protein are about 100-fold lower than in insect cells . We thus think that the physiologic impact of Ser473 phosphorylation is of major importance in stimulating kinase activity, about the same 500-fold as phosphorylation of Thr308 [35••].

It was also shown with EPL produced Akt1 that Asp473 was unable to simulate the pSer473 protein and showed similar activity to Ser473 Akt1 [35••]. The basis for this difference was ultimately revealed using a combination of crystallography (see Figure 2) and mutagenesis to involve a key hydrogen bond between the phosphate of pSer473 and the sidechain of Arg144 of the linker between the PH domain and the kinase domain (see Figure (b) Inactive conformation of Akt3). The model from these studies is that C-terminal phosphorylation of Akt1 at Ser473 engages the PH-kinase domain linker and exerts tension that peels off the PH domain from the kinase domain, fostering full catalytic activity (see Figure (b) Inactive conformation of Akt3) [35••]. We speculate that the role of pSer473 in Akt may be exploited more widely as a strategy to relieve autoinhibition in the AGC kinase family in which C-terminal phosphorylation contacts segments outside the kinase domain, although this remains to be established.

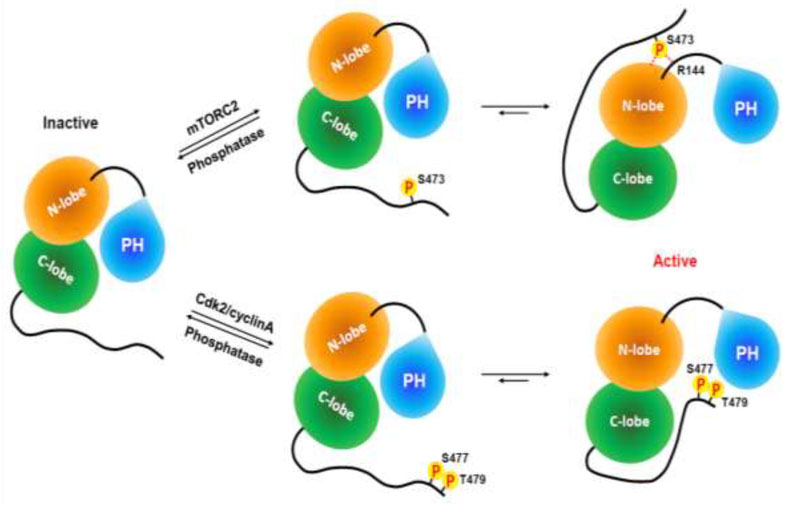

In 2014, Akt1 was reported to be phosphorylated by cyclin dependent kinase 2 on two C-terminal residues, Ser477 and Thr479 as a mode of activation of nuclear Akt1 [42]. In this original study, it was suggested that the mechanism of pSer477 and pSer479 mediated activation of Akt1 was the same as that for pSer473 induced activation, namely N-lobe engagement [43]. Using EPL, our lab recently prepared single and multiply C-terminally phosphorylated Akt1 at Ser477 and Thr479 including the triply phosphorylated 473/477/479 form [35••]. These experiments showed that the mono-phosphorylated Akt1 at Ser477 or Thr479 possessed similar activity to that of non-phosphorylated C-tail Akt1 protein but the dual pSer477/pThr479 Akt1 showed a similar kcat to that of pSer473, although pSer477/pThr479 Akt1 displayed ~10-fold higher Km for ATP [35••]. Catalytic parameters of the triply tail-phosphorylated Akt were similar to singly pSer473 Akt1 indicating that when pSer473 is present, it dominates the C-terminal effects [35••].

Interestingly, dual pSer477/pThr479 Akt1 activity was not significantly lessened by Gln218 or Arg144 mutation in contrast to the behavior of pSer473 Akt1 [35••]. Therefore, pSer477/pThr479 modifications promote a different mechanism of activation compared to the canonical mode of pSer473-mediated activation of Akt1 (see Figure (b) Inactive conformation of Akt3). Crosslinking and other biochemical analysis led to a proposed model that pSer477/pSer479 tail may lie near the activation loop and PH domain to disrupt the PH-kinase domain autotinhibitory interaction [35••] (see Figure (b) Inactive conformation of Akt3). Based on the different catalytic parameters, presumed nuclear localization, and diminished PIP3 affinity of the pSer477/pSer479 form of Akt1, it seems possible that this activation state may target a distinct set of protein substrates compared with pSer473 Akt and have a unique signaling role.

Regulation of Akt1–3 by other PTMs

In addition to the aforementioned phosphorylation events that activate Akt1–3, phosphorylation at several other Akt1–3 residues has been reported as influencing its kinase activity [2]. Some of the kinases that phosphorylate these residues are still unknown and the mechanism by which these activate Akt1–3 is uncertain at this time. Akt1–3 have been shown to be ubiquitinated by various E3 ubiquitin ligases [2]. Although in some cases these ubiquitinations may target Akt1–3 for degradation, it has also been proposed that in certain circumstances ubiquitinations may be activating. It was reported that Akt1 ubiquitination by the E3 ligase TRAF6 on the PH domain promotes Akt1 translocation to the plasma membrane and stimulates activation by allowing phosphorylation of Thr308 and Ser473 [44]. If this is the case, perhaps such ubiquitinations can disrupt the PH-kinase domain interface to relieve autoinhibition. There have also been a number of PTMs that have been mapped to the PH domain-kinase linker in Akt1–3 including Pro hydroxylation (leading to dephosphorylation of Akt1 and Akt2) [45], Cys oxidation [46], and Lys methylation [47•,48•]. One can surmise that such modifications could influence the pSer473-linker interaction, thereby regulating activation state. We believe that extending the use of EPL along with other newly developed chemical strategies may prove useful in illuminating these mechanisms [49,50].

Summary

Akt1–3 are widely recognized as central nodes in cell signaling throughout physiology and pathology, and it is apparent that evolutionary forces have driven their intricate regulation by phospholipids and PTMs. Recent studies on Akt1–3 have uncovered a rich tapestry of activation mechanisms of Akt1–3 which all seem to result in loosening PH domain-kinase domain autoinhibition. The distinct catalytic behaviors and activation mechanisms of the different C-terminal Akt1–3 phospho-forms are somewhat reminiscent of the histone code in regulating chromatin state and gene expression [51]. Future studies will be needed to illuminate the full details of the diverse PTM impacts on biological function and therapeutics development.

Figure 3. Cartoon models of Akt1 activation induced by mono-phosphorylation at Ser473 or dual-phosphorylation at Ser477 and Thr479.

Without phosphorylation at its C-terminus, Akt1 has an autoinhibited conformation through a PH domain-kinase domain interaction. The interaction of phosphorylated Ser473 with the kinase domain N-lobe (Gln218) and the PH-kinase linker (Arg144) relieves tautoinhibition and activates Akt1. Dual phosphorylation of Ser477 and Thr479 also activates Akt1 by relieving PH domain-mediated autoinhibition via a different molecular mechanism.

Acknowledgements:

We thanks Cole lab members, W. Wei, A. Toker, and S. Gabelli for helpful discussion and advice. We are grateful to the NIH (CA74305) and the Kwanjeong Educational Foundation for financial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Staal SP: Molecular cloning of the akt oncogene and its human homologues AKT1 and AKT2: amplification of AKT1 in a primary human gastric adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1987, 84:5034–5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manning BD, Toker A: AKT/PKB Signaling: Navigating the Network. Cell 2017, 169:381–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor SS, Kornev AP: Protein kinases: evolution of dynamic regulatory proteins. Trends Biochem Sci 2011, 36:65–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parang K, Till JH, Ablooglu AJ, Kohanski RA, Hubbard SR, Cole PA: Mechanism-based design of a protein kinase inhibitor. Nat Struct Biol 2001, 8:37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin J, Anamika K, Srinivasan N: Classification of protein kinases on the basis of both kinase and non-kinase regions. PloS One 2010, 5:e12460–e12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearce LR, Komander D, Alessi DR: The nuts and bolts of AGC protein kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010, 11:9–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lahiry P, Torkamani A, Schork NJ, Hegele RA: Kinase mutations in human disease: interpreting genotype–phenotype relationships. Nature Reviews Genetics 2010, 11:60–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson FM, Gray NS: Kinase inhibitors: the road ahead. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018, 17:353–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.•.Arencibia JM, Pastor-Flores D, Bauer AF, Schulze JO, Biondi RM: AGC protein kinases: From structural mechanism of regulation to allosteric drug development for the treatment of human diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1834:1302–1321.of special interest: Very comprehensive review about the AGC kinase family with detailed discussion about patterns of C-tail phosphorylation and effects.

- 10.Kannan N, Haste N, Taylor SS, Neuwald AF: The hallmark of AGC kinase functional divergence is its C-terminal tail, a cis-acting regulatory module. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104:1272–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douglass J, Gunaratne R, Bradford D, Saeed F, Hoffert JD, Steinbach PJ, Knepper MA, Pisitkun T: Identifying protein kinase target preferences using mass spectrometry. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2012, 303:C715–C727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franke TF, Yang S-I, Chan TO, Datta K, Kazlauskas A, Morrison DK, Kaplan DR, Tsichlis PN: The protein kinase encoded by the Akt proto-oncogene is a target of the PDGF-activated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Cell 1995, 81:727–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgering BMT, Coffer PJ: Protein kinase B (c-Akt) in phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase signal transduction. Nature 1995, 376:599–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alessi DR, James SR, Downes CP, Holmes AB, Gaffney PRJ, Reese CB, Cohen P: Characterization of a 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase which phosphorylates and activates protein kinase Bα. Curr Biol 1997, 7:261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stokoe D, Stephens LR, Copeland T, Gaffney PRJ, Reese CB, Painter GF, Holmes AB, McCormick F, Hawkins PT: Dual Role of Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate in the Activation of Protein Kinase B. Science 1997, 277:567–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM: Phosphorylation and Regulation of Akt/PKB by the Rictor-mTOR Complex. Science 2005, 307:1098–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee Y-R, Chen M, Pandolfi PP: The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor: new modes and prospects. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018, 19:547–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanhaesebroeck B, Guillermet-Guibert J, Graupera M, Bilanges B: The emerging mechanisms of isoform-specific PI3K signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010, 11:329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manning BD, Cantley LC: AKT/PKB Signaling: Navigating Downstream. Cell 2007, 129:1261–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.•.Domanova W, Krycer J, Chaudhuri R, Yang P, Vafaee F, Fazakerley D, Humphrey S, James D, Kuncic Z: Unraveling Kinase Activation Dynamics Using Kinase-Substrate Relationships from Temporal Large-Scale Phosphoproteomics Studies. PloS One 2016, 11:e0157763.of special interest-A nice integration of approaches to classify substrates for protein kinases as direct or indirect.

- 21.Cross DAE, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA: Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature 1995, 378:785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaidanovich-Beilin O, Woodgett J: GSK-3: Functional Insights from Cell Biology and Animal Models. Front Mol Neurosci 2011, 4:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vos KE, Coffer PJ: The Extending Network of FOXO Transcriptional Target Genes. Antioxid Redox Signal 2011, 14:579–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webb AE, Brunet A: FOXO transcription factors: key regulators of cellular quality control. Trends Biochem Sci 2014, 39:159–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paradis S, Ruvkun G: Caenorhabditis elegans Akt/PKB transduces insulin receptor-like signals from AGE-1 PI3 kinase to the DAF-16 transcription factor. Genes Dev 1998, 12:2488–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sancak Y, Thoreen CC, Peterson TR, Lindquist RA, Kang SA, Spooner E, Carr SA, Sabatini DM: PRAS40 Is an Insulin-Regulated Inhibitor of the mTORC1 Protein Kinase. Mol Cell 2007, 25:903–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haar EV, Lee S-i, Bandhakavi S, Griffin TJ, Kim D-H: Insulin signalling to mTOR mediated by the Akt/PKB substrate PRAS40. Nat Cell Biol 2007, 9:316–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan K-L: TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol 2002, 4:648–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, Blenis J, Cantley LC: Identification of the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex-2 Tumor Suppressor Gene Product Tuberin as a Target of the Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Akt Pathway. Mol Cell 2002, 10:151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saxton RA, Sabatini DM: mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168:960–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellacosa A, Chan TO, Ahmed NN, Datta K, Malstrom S, Stokoe D, McCormick F, Feng J, Tsichlis P: Akt activation by growth factors is a multiple-step process: the role of the PH domain. Oncogene 1998, 17:313–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calleja V, Alcor D, Laguerre M, Park J, Vojnovic B, Hemmings BA, Downward J, Parker PJ, Larijani B: Intramolecular and Intermolecular Interactions of Protein Kinase B Define Its Activation In Vivo. PLoS Biol 2007, 5:e95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calleja V, Laguerre M, Parker PJ, Larijani B: Role of a Novel PH-Kinase Domain Interface in PKB/Akt Regulation: Structural Mechanism for Allosteric Inhibition. PLoS Biol 2009, 7:e1000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas CC, Deak M, Alessi DR, van Aalten DMF: High-Resolution Structure of the Pleckstrin Homology Domain of Protein Kinase B/Akt Bound to Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-Trisphosphate. Curr Biol 2002, 12:1256–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.••.Chu N, Salguero AL, Liu AZ, Chen Z, Dempsey DR, Ficarro SB, Alexander WM, Marto JA, Li Y, Amzel LM, et al. : Akt Kinase Activation Mechanisms Revealed Using Protein Semisynthesis. Cell 2018, 174:897–907.of outstanding interest-A detailed investigation of the role of C-terminal phosphorylation in modulating Akt1.

- 36.Wu W-I, Voegtli WC, Sturgis HL, Dizon FP, Vigers GPA, Brandhuber BJ: Crystal Structure of Human AKT1 with an Allosteric Inhibitor Reveals a New Mode of Kinase Inhibition. PloS One 2010, 5:e12913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ebner M, Lučić I, Leonard TA, Yudushkin I: PI(3,4,5)P3 Engagement Restricts Akt Activity to Cellular Membranes. Mol Cell 2017, 65:416–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Z, Cole PA: Chapter One - Catalytic Mechanisms and Regulation of Protein Kinases In Methods Enzymol. Edited by Shokat KM: Academic Press; 2014:1–21. vol 548.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang J, Cron P, Good VM, Thompson V, Hemmings BA, Barford D: Crystal structure of an activated Akt/Protein Kinase B ternary complex with GSK3-peptide and AMP-PNP. Nat Struct Biol 2002, 9:940–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balasuriya N, Kunkel MT, Liu X, Biggar KK, Li SS-C, Newton AC, O’Donoghue P: Genetic code expansion and live cell imaging reveal that Thr-308 phosphorylation is irreplaceable and sufficient for Akt1 activity. J Biol Chem 2018, 293:10744–10756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muir TW, Sondhi D, Cole PA: Expressed protein ligation: A general method for protein engineering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998, 95:6705–6710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Z, Wei W: Phosphorylation of Akt at the C-terminal tail triggers Akt Activation AU - Liu, Pengda. Cell Cycle 2014, 13:2162–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu P, Begley M, Michowski W, Inuzuka H, Ginzberg M, Gao D, Tsou P, Gan W, Papa A, Kim BM, et al. : Cell-cycle-regulated activation of Akt kinase by phosphorylation at its carboxyl terminus. Nature 2014, 508:541–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang W-L, Wang J, Chan C-H, Lee S-W, Campos AD, Lamothe B, Hur L, Grabiner BC, Lin X, Darnay BG, et al. : The E3 Ligase TRAF6 Regulates Akt Ubiquitination and Activation. Science 2009, 325:1134–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo J, Chakraborty AA, Liu P, Gan W, Zheng X, Inuzuka H, Wang B, Zhang J, Zhang L, Yuan M, et al. : pVHL suppresses kinase activity of Akt in a prolinehydroxylation–dependent manner. Science 2016, 353:929–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wani R, Qian J, Yin L, Bechtold E, King SB, Poole LB, Paek E, Tsang AW, Furdui CM: Isoform-specific regulation of Akt by PDGF-induced reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108:10550–10555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.•.Wang G, Long J, Gao Y, Zhang W, Han F, Xu C, Sun L, Yang S-C, Lan J, Hou Z, et al. : SETDB1-mediated methylation of Akt promotes its K63-linked ubiquitination and activation leading to tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol 2019, 10 10.1038/s41556-018-0266-1.of special interest: This study describes methylation of the PH domain of Akt as an activation mechanism.

- 48.•.Guo J, Dai X, Laurent B, Zheng N, Gan W, Zhang J, Guo A, Yuan M, Liu P, Asara JM, et al. : AKT methylation by SETDB1 promotes AKT kinase activity and oncogenic functions. Nat Cell Biol 2019, 10 10.1038/s41556-018-0261-6.of special interest: This paper discusses how linker methylation of Akt may activate the kinase activity

- 49.Dempsey DR, Jiang H, Kalin JH, Chen Z, Cole PA: Site-Specific Protein Labeling with N-Hydroxysuccinimide-Esters and the Analysis of Ubiquitin Ligase Mechanisms. J Am Chem Soc 2018, 140:9374–9378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhat S, Hwang Y, Gibson MD, Morgan MT, Taverna SD, Zhao Y, Wolberger C, Poirier MG, Cole PA: Hydrazide Mimics for Protein Lysine Acylation To Assess Nucleosome Dynamics and Deubiquitinase Action. J Am Chem Soc 2018, 140:9478–9485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jenuwein T, Allis CD: Translating the Histone Code. Science 2001, 293:1074–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]