Abstract

Members of the genus Penicillium are commonly isolated from various terrestrial and marine environments, and play an important ecological role as a decomposer. To gain insight into the ecological role of Penicillium in intertidal zones, we investigated the Penicillium diversity and community structure using a culture-dependent technique and a culture independent metagenomic approach using ITS (ITS-NGS) and partial β-tubulin (BenA-NGS) as targets. The obtained isolates were tested for halotolerance, enzyme activity, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) degradation. A total of 96 Penicillium species were identified from the investigated intertidal zones. Although the BenA-NGS method was efficient for detecting Penicillium, some species were only detected using conventional isolation and/or the ITS-NGS method. The Penicillium community displayed a significant degree of variation relative to season (summer and winter) and seaside (western and southern coast). Many Penicillium species isolated in this study exhibited cellulase and protease activity, and/or degradation of PAHs. These findings support the important role of Penicillium in the intertidal zone for nutrient recycling and pollutant degradation.

Subject terms: Microbial ecology, Microbial ecology, Taxonomy, Taxonomy, Fungi

Introduction

The genus Penicillium is commonly isolated from various terrestrial environments such as indoor environments, soil, and food, and is known to play an important ecological role as a decomposer1–3. Recently, Penicillium species have been reported from various marine environments such as sand, seawater, and macroalgae4–7 and have proven to be valuable biological resources due to producing secondary metabolites and enzymes5,8,9. This suggests that Penicillium also plays an important role in the marine environment. Previous studies of marine environments focused on screening for applicable enzymes as well as novel bioactive compounds through the isolation of Penicillium species5,6,8,9. Studying the diversity and ecological roles is needed to enhance our understanding of Penicillium in marine environments.

The application of culture-independent techniques has provided new insights into a greater diversity and ecological role of fungi in marine habitats10–12. When comparing a variety of molecular methods such as ribosomal RNA (rRNA) clone libraries, denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE), and terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) analysis to culture-dependent method, higher fungal diversities have been reported for the latter from deep sea sediment13, sea cucumber farming systems14, and sponges15. Recently, metagenomic analysis using next generation sequencing (NGS) has been used to further understand microbial characteristics in environments and has shown its usefulness in discovering fungal diversity in marine environments such as coral10 and mangrove sediments16. Hurdles to overcome are that taxonomic assignment of sequence data depends on the quality and comprehensiveness of available databases, as well as the resolution of the molecular marker17. Three loci (18S nuclear ribosomal small subunit rRNA gene [SSU], 28S nuclear ribosomal large subunit rRNA gene [LSU], and internal transcribed spacer [ITS] region) have been used in metagenomic studies due to high PCR amplification and sequencing success18–20. However, these loci have low resolution for species identification in the genera Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Trichoderma. Specific protein-coding genes sequence are recommended for species identifications in these genera3,21–23.

Intertidal zones play an important role in the marine nutrient cycling, decomposition, harboring biodiversity, and pollutant degradation24. Microbes are essential in the intertidal zone for mineralization of organic matter and degradation of pollutants25,26. Given their roles and activities in marine environments, fungal communities in the intertidal zone may be distinctive and have important ecological functions. Although reports of Penicillium in marine environment are increasing, there is no comprehensive study on species diversity and what roles they play.

In this study, we investigated Penicillium in intertidal zones (mudflat and sand) in South Korea. Penicillium is a good model genus for investigating fungal diversity and functional roles in the environment because of its frequent occurrence, high enzyme activity, and ability to grow on artificial media. Reliable species identification is possible because a standardized method has been outlined to identify Penicillium at the species level using morphology and the β-tubulin (BenA) gene3. To understand Penicillium diversity, community structure, and ecological roles, we used and compared a variety of methods: a culture-dependent approach with three different media, and a culture-independent metagenomic approach using ITS and BenA as targets. To understand the ecological roles of Penicillium in intertidal zones, we evaluated the halotolerance, enzyme activities (extracellular endoglucanase, β-glucosidase, and protease), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) degradation for cultured species.

Results

Penicillium diversity from culture-dependent approach

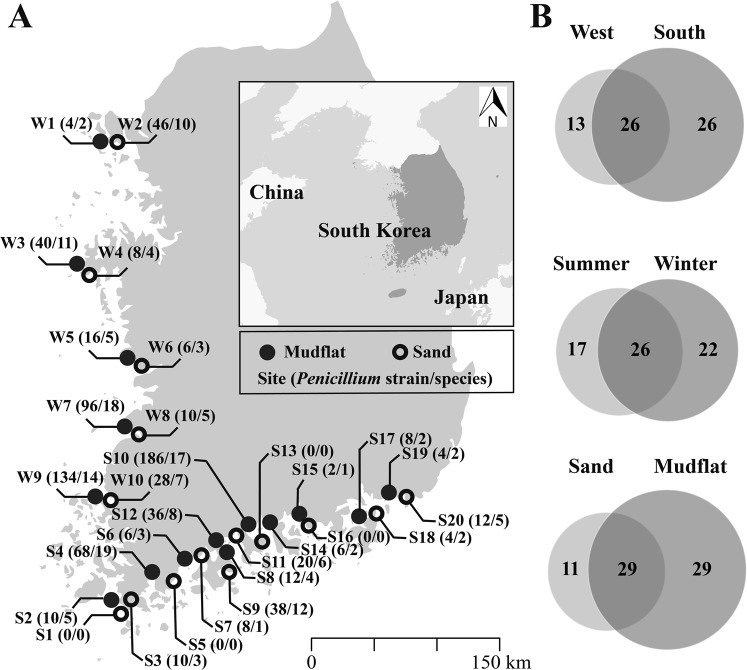

A total of 818 Penicillium strains were isolated from mudflat (626 strains) and sand (192 strains), collected along the western (388 strains) and southern coast (430 strains) of Korea (Table S1). On the basis of morphological comparisons and ITS sequences, 818 strains were categorized in 65 groups. One to three representative strains of each group were identified to the species level based on a section-by-section phylogenetic analysis using BenA, with a total of 187 strains chosen. These strains were identified as 57 species, with eight strains that could not be identified that represent eight potential new species. The species numbers of Penicillium differed depending on season, seaside, and substrate, although it was not statistically significant. The differences of Penicillium according to season, seaside, and substrate are shown in Fig. 1 and Table S2.

Figure 1.

The number of identified Penicillium species from each sampling sites. (A) Map showing the number of (strains/species) at each location. (B) The number of Penicillium species isolated depended on season (summer and winter), seaside (western and southern coast), and substrate (mudflat and sand). Raw map was obtained from https://freevectormaps.com/ and edited in Adobe Illustrator CS6 (Adobe Systems Inc., CA, USA).

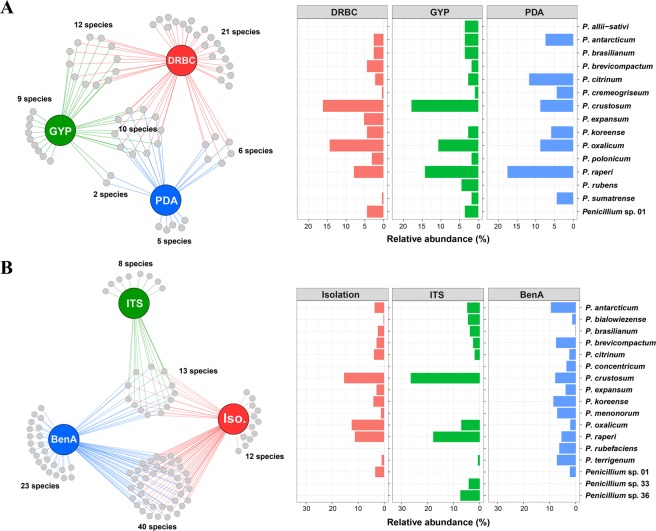

Different numbers of Penicillium species were isolated depending on the isolation medium: 49 species were isolated on DRBC, 33 species on GYP, and 23 species on PDA (Table S1). Ten species were isolated on all media. A total of 21, 9, and 5 species were exclusively isolated on DRBC, GYP, and PDA, respectively (Fig. 2A). Penicillium crustosum was the predominant species, followed by P. oxalicum and P. raperi.

Figure 2.

Penicillium diversity detected from intertidal zone. (A) Total, unique, and shared Penicillium species and relative abundance of major species (3%) from three different media (DRBC, GYP, and PDA). (B) Total, unique, and shared Penicillium species and relative abundance of major species (3%) obtained from isolation, NGS using ITS, and NGS using benA.

Penicillium diversity from culture-independent approach

For ITS-NGS, a total of 2,363,934 fungal sequence reads were obtained, of which 1,813,137 reads were retained after filtering low quality sequences. Most Good’s coverage estimates were 0.955–0.997, indicating a sufficient coverage for diversity analysis. One sample had a score of 0.890. Among the total number of sequences, Penicillium sequences accounted for 1,301 reads, and 21 mOTUs (99% threshold) were assigned to 21 species based on the phylogenetic analysis (Table S2 and Fig. S1). The mOTUs were identified to the species level based on a section-by-section phylogenetic analysis using ITS sequences. A total of 13 species were identified to known Penicillium species, and the remaining eight species could not be confidently identified because of unclear phylogenetic relationships. Penicillium crustosum (27.8%) was the predominant species, followed by P. raperi (18.7%), Penicillium sp. 36 (7.8%), and P. oxalicum (7.4%) (Fig. 2B).

For BenA-NGS, a total of 1,513,345 fungal sequence reads were obtained, of which 860,499 reads were retained after filtering the low quality and non-Penicillium sequences. A total of 970 mOTUs (99% threshold) were detected, representing 76 species based on the phylogenetic analysis (Table S2 and Fig. S2). All Good’s coverage estimates were 0.989–1.000, indicating that sequencing depth was appropriate for the representing Penicillium diversity. Penicillium antarcticum (9.5%) was the predominant species, followed by P. koreense (8.6%), P. crustosum (7.9%), P. brevicompactum (7.6%), P. terrigenum (7.3%), P. menonorum (7.2%), P. rubefaciens (6.3%), and P. raperi (5.5%) (Fig. 2B).

Comparison of culture-dependent and –independent approaches

In total, 96 Penicillium species were detected from mudflat and sand using the three different methods (conventional isolation, ITS-NGS, and BenA-NGS) (Fig. 2B and Table S2). Each method identified a different number of species: 65 species from isolation, 21 species from ITS-NGS, and 76 species from BenA-NGS. A total of 13 species were shared across all three methods. Particularly, P. antarcticum, P. crustosum, and P. raperi were commonly detected from mudflat and sand in all methods. Several species were detected by only one method: isolation (12 species), ITS-NGS (8 species), and BenA-NGS (23 species) (Fig. 2B). Penicillium rubefaciens and P. concentricum were commonly detected in BenA-NGS, but not detected in isolation and ITS-NGS.

Community structure of Penicillium

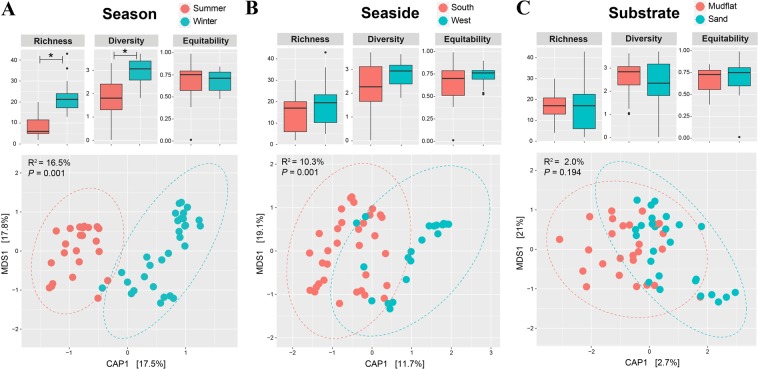

Diversity and community analyses were conducted based on the BenA-NGS dataset because it represents Penicillium communities the best, with exact species-level identification and high coverage power for detecting Penicillium species compared to other methods. Alpha diversity indices for Penicillium communities were compared between season (summer and winter), seaside (western and southern coast), and substrate (mudflat and sand) (Fig. 3). Species richness and diversity were significantly different based on season (Richness: P < 0.001; Diversity: P < 0.001), while evenness was comparable (P = 0.702). The winter season had a higher richness and diversity compared to the summer season. However, no index showed a significant difference for seaside (Richness: P = 0.189; Diversity: P = 0.164; Equitability: P = 0.180) and substrate (Richness: P = 0.634; Diversity: P = 0.634; Equitability: P = 0.634).

Figure 3.

Alpha diversity and Constrained Analysis of Principal coordinates (CAP) plots for Penicillium communities in season, seaside, and substrate. Significance of difference in diversity indices was tested by Wilcox rank sum test with FDR correction (*P < 0.05). CAP plots for Penicillium communities based on Bray-Curtis distance were constrained by (A) season, (B) seaside, or (C) substrate. Significance of CAP models was evaluated using ANOVA with 999 permutations.

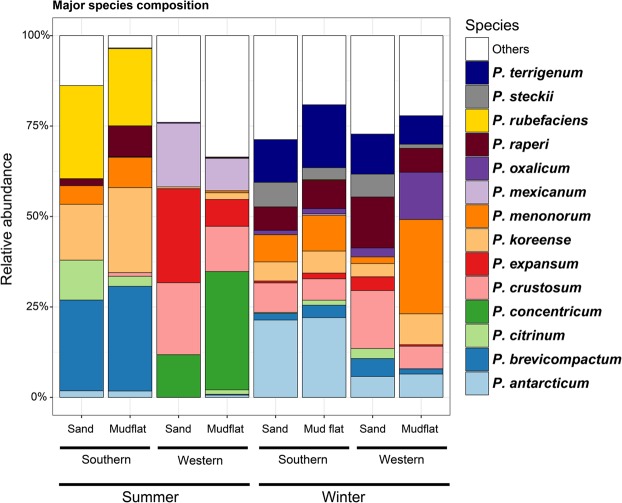

Penicillium communities were compared between season, seaside, and substrate using CAP analysis (Fig. 3). The community structure of Penicillium was significantly different depending on season (P = 0.001, 16.5% explanatory power) (Fig. 3A). Penicillium brevicompactum, P. concentricum, P. expansum, P. koreense, P. mexicanum, and P. rubefaciens were more abundant in the summer than the winter (Fig. 4). In contrast, P. antarcticum and P. terrigenum were more abundant in the winter. Seaside had a significant effect on the clustering of communities (P = 0.001, 10.3% explanatory power) (Fig. 3B). Among major species, P. antarcticum, P. brevicompactum, P. koreense, P. rubefaciens, and P. terrigenum were significantly more abundant from the southern coast compared to the western coast (Fig. 4). In contrast, P. concentricum, P. expansum, and P. mexicanum were significantly more abundant on the western coast. Substrate did not significantly influence the Penicillium community structures (P = 0.194, 2.0% explanatory power) (Fig. 3C).

Figure 4.

Composition of major Penicillium species obtained from NGS using benA. Relative abundance of major species obtained in season (summer and winter), seaside (western and southern coast), and substrate (mudflat and sand) from South Korea.

Halotolerance, enzyme activity, and PAH degradation

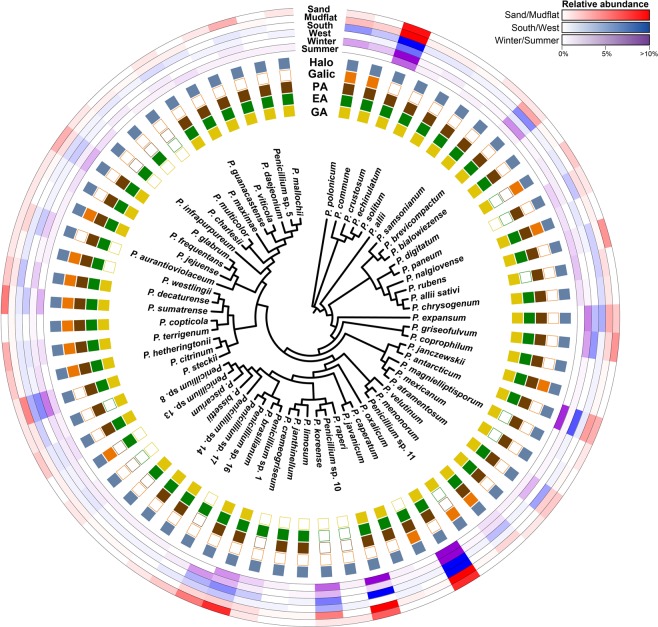

All species recovered from isolation showed halotolerance (Fig. 5). Among the 65 species, 54 species showed β-glucosidase activity, with P. citrinum (SFC20151118-M02) and P. raperi (SFC20150915-M08) exhibiting the strongest activity. Fifty species showed endoglucanase activity, with P. bialowiezense (SFC20151014-M03), P. rubens (SFC20151014-M07), and P. hetheringtonii (SFC20151014-M08) exhibiting relatively strong endoglucanase activity. Among 53 species showing protease activity, P. guanacastense (SFC100711) and Penicillium sp. 5 (SFC100716) showed the strongest activity. For PAH degradation, 16 species showed a positive reaction as indicated by a brown color. Penicillium caperatum (SFC20151118-M06), P. decaturense (SFC20150303-M14), P. hetheringtonii (SFC20151014-M08), and P. janczewskii (SFC20151014-M10) showed the strongest positive reaction (Table S1).

Figure 5.

The relative abundance and physiological characteristics (halotolerance, enzyme activity, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [PAHs] degradation) of the Penicillium strains in a phylogenetic context. The neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was based on partial BenA gene sequences. The relative abundance of Penicillium isolated from intertidal zone is color coded on the outer ring (substrate – red; season – blue; seaside – purple). Halotolerance, enzyme activity, and PAH degradation of the Penicillium is color coded on the inner ring (Halotolerance – light blue; gallic acid reaction – orange; protease – brown; endoglucanase – green; β-glucosidase - yellow).

Discussion

Penicillium diversity using culture-dependent and –independent approaches

We conducted a comphrensive study to determine the species richness of Penicillium found in the intertidal zone along the Korean coast, testing for impact of season, seaside, and substrate. A total of 96 Pencillium species were identified using three different methods (isolation, ITS-NGS, BenA-NGS). We identified 54 more species than the number of Penicillium species previously recorded in Korea27 and 58 more species than the number of Penicillium species reported from the marine environment globally4–6,28–31. Most of the previous studies of marine Penicillium from intertidal zones focused on screening for industrially useful enzymes as well as novel bioactive compounds. Therefore, these studies primarily identified strains to the genus level only and a handful to the species level (Penicillium chrysogenum, Penicillium citrinum) using ITS sequences32,33. Compared to our previous studies5,34, we identified 41 species new to intertidal zones, as well as 17 new species candidates.

Most previous studies used either a culture-dependent method35,36 or a culture-independent method using a single locus (e.g. ITS)37,38. We employed three methods to detect as many Penicillium species as possible and to compare the effectiveness of the three methods. Generally, a culture-dependent method isolates only a small subset of the microbial diversity from environments39. In our study, a relatively high proportion of Penicillium species (63.1%) were detected using a culture-dependent method. This is likely due to the fact that we focused on Penicillium, which are generally easy to culture; many Penicillium species are isolated from various substrates from terrestrial environments1,2,40,41 and marine environments4–7. Another reason for the high detection is that we used three different media for isolation. More Penicillium species were isolated from the DRBC medium compared to the other two media. DRBC medium suppresses fast growing fungi, while the other isolation media do not42. Some Penicillium species grow slowly and may be covered by fast growing fungi43. Several species were only isolated on one agar medium (Fig. 2A), but there was no apparent tendency for them to prefer certain media. Therefore, more different media have the opportunity to isolate the more diverse Penicillium species.

Although NGS methods help to detect more diverse fungi within the environment, molecular marker selection has a significant impact on NGS methods. The ITS region is less discriminative in identifying species of Penicillium than BenA. However, we use ITS, as well as BenA, since it is widely accepted fungal barcode22. In our study, certain species have been detected only in ITS-NGS. Among the 84 species detected in the NGS analysis, 15.5% of the Penicillium species were shared between ITS-NGS and BenA-NGS, while 9.5% were exclusive to ITS-NGS and 75.0% exclusive to BenA-NGS. A total of 20 Penicillium species were not detected in BenA-NGS (8 species from ITS-NGS and 12 species from isolation). The phenomenon of mismatched fungal diversity depending on the survey methods has been seen in previous studies44–47, which can result from the technical bias associated with DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing48. Low abundance species were generally prone to technical bias, which agrees with our results (Table S2). In the case of ITS-NGS, low sequence variation of the ITS2 region can be one of the sources of diversity difference to BenA-NGS; some Penicillium species cannot be assigned to species level based on the ITS2 region. If we consider the potential species based on ITS2 similarity (Table S2 and Fig. S1), five more species can be added to the number of shared mOTUs (Penicillium sp. 33, 34, 36, 38, 39). The unique species detected using the isolation method may correspond to the species occurring at low concentration; the culture-dependent method has been shown to detect bacteria at a broader range of concentrations that is 102–104 times lower than that of the culture-independent method49. The higher number of mOTU detected by BenA-NGS compared to ITS-NGS suggests that it is useful to develop genus-specific primers for protein-coding genes (compared to ITS) for species identification and species richness studies. This is the first study using BenA-NGS for Penicillium diversity, and demonstrates its usefulness for detecting Penicillium in the environment. However, as with using multiple media for culture studies, combining multiple molecular markers will likely identify a greater species richness.

Penicillium community structure depends on environmental factors

We found that Penicillium diversity was significantly higher in winter than summer. Given that the diversity did not differ between substrate and seaside, seasonal variation seems to be an important factor influencing Penicillium diversity. High diversity in winter was also detected in studies of terrestrial fungi50,51, which may relate to severe environmental conditions. Various species can co-exist together in harsh environments, and, when conditions are relaxed, a single or small number of species are able to dominate and exclude other species50. In the winter season, Penicillium may be in spore state or grow slowly, which prevents the dominance of a single species. On the other hand, nutrient deficiency may occur in winter. Since coastal zones are influenced by river flows and oceanic currents, nutrient supply can fluctuate seasonally; nutrient supply from rivers is high in summer and low in winter52,53. Oligotrophic condition in winter may lead to co-existence of various Penicillium species.

There were different patterns of the Penicillium community between the western and southern coasts. The difference in Penicillium community between seasides is likely influenced by the difference in oceanic currents in each region. The western coast is influenced by the cold currents of West Korea Coastal Current during winter and summer, whereas the southern seaside is influenced by both the Jeju Warm Current and Taiwan Warm Current during winter and summer54. Ocean current patterns influence on the community structure of bacteria, ammonia-oxidizing archaea, and animal biodiversity55–57. Previous studies showed that temperature influences fungal community in marine environments58,59. The ocean currents likely provide temperature and physical barriers limiting Penicillium dispersal and affect Penicillium diversity. Some marine fungi have shown the differential preference on the plant species60,61, thus the vegetation composition in the coasts can be another environmental factor that influences on the fungal community structure. In South Korea, the flora of western and southern coasts is different62,63, which likely influences the Penicillium communities.

Considering physiochemical differences between mudflat and sand (e.g. texture and nutrient composition), different Penicillium communities were expected. However, the substrate did not significantly influence the diversity and community structure of Penicillium (Fig. 3C). Though environmental filtering by substrates is important factor to differentiate fungal communities64–67, marine fungal community structures usually depend on the biological substrate such as animal, algae, or plant15,35,68. Macroalgae, sponge, and animal debris have been known to harbor high Penicillium diversity5,7,69,70. High enzyme activity associated with alginate, cellulose, and protein detected in Penicillium isolates supports this speculation.

Ecological roles of Penicillium associated with enzyme activities

Penicillium species from various environments produce a variety of enzymes such as alginase, cellulase, chitinase, and proteasee5,7,71,72. Protease activity has been reported in fungi isolated from various marine environments73,74. Particularly, members in Penicillium are known for their biotechnological potential in the production of proteases72. In our study, a relatively high proportion of Penicillium from the intertidal zone exhibited endoglucanase, β-glucosidase, and protease activity. A high proportion of species having enzyme activities and halotolerance implies that these species play an important role as decomposers of cellulose and protein in the intertidal zone. Macroalgae (over 400 species reported to date)75 and animal debris such as crab, fish, shells, and sponges are frequently found in the intertidal zone. Penicillium species that have a high enzyme activity can use this abundant algae and animal debris on the intertidal zone as a their favorite nutrient source. Although the species in the Penicillium sections Brevicompacta, Citrina, Canescentia, Fasciculata, and Sclerotiora showed relatively higher enzyme activity than the species in the other sections, there was no distinct pattern of enzyme activity based on a phylogenetic group.

Microbes are known to degrade various pollutants that result from human activities in intertidal zones76. Members in the genus Penicillium have been shown to degrade environmental pollutants such as synthetic dyes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)72. PAHs are produced by the incomplete combustion of organic matter such as oil and wood77. Penicillium canescens, P. chrysogenum, P. frequentans, P. italicum, P. janthinellum, P. montanense, P. simplicissimum, and P. restrictum are known to degrade PAHs78, but these species did not show PAHs degrading ability in our study. The PAHs-degrading ability of fungi varies by strain and species. The capability of PAHs degradation was observed in only a few Penicillium species in this study. Particularly, the species (P. decaturense and P. hetheringtonii) in section Citrina showed a relatively higher ability to degrade the PAHs compared to species in other sections.

Conclusions

The number of studies investigating marine fungi has increased in recent years and Penicillium are one of the many fungi reported from this environment. In this study, we detected 96 Penicillium species from mudflat and sand from Korea using three different analysis techniques (conventional isolation, ITS-NGS, and BenA-NGS). Although BenA-NGS detected the highest number of Penicillium species, some Penicillium species were only detected by isolation and/or ITS-NGS method. If the goal is to identify the total species diversity, we suggest combining various approaches to detect more species. Many of the isolated Penicillium exhibited cellulase activity, protease activity, and/or degradation of PAHs. Penicillium is a decomposer of a variety of marine organisms and it is thought to play an important role in nutrient recycling and pollutant degradation in intertidal environments. However, it is unclear whether the Penicillia identified in this study are in an active or inactive form in the marine environment. An additional study will be needed to further identify what is the actual function of the Penicillia in the marine environment. We expect that this study will provide basic information regarding the Penicillium diversity and improve interest in the functional role of Penicillia in marine environments.

Materials and Methods

Sample collections

During summer (July and August in 2014) and winter (February 2015), mudflat and sand samples were collected from 30 coastal sites around Korea (10 western coast, 20 southern coast) for each season (Fig. 1). Samples were collected during low tide. To fully characterize each site, each sample contained five subsamples collected approximately 20 m from each other. Each subsample was collected at 2–3 cm depth after removing the top soil to avoid surface contamination. Samples were transported on ice and stored at 4 °C for isolation and at −80 °C for DNA extraction.

Diversity analysis by culture-dependent approach

Isolation of fungi

For each sample, 5 g was tenfold diluted with sterilized artificial sea water (ASW)79. For each dilution, 100 μL was plated on potato dextrose agar (PDA, Difco, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA), glucose yeast extract agar (GYP; 1 g L−1 glucose, 0.1 g L−1 yeast extract, 0.5 g L−1 peptone, and 15 g L−1 agar), and dichloran rose bengal chloramphenicol agar (DRBC; Difco, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA). We performed a preliminary test for screening the growth of Penicilium at different temperatures (10 °C, 15 °C, 20 °C, 25 °C, 30 °C) on malt extract agar (MEA; Oxoid) and chose 25 °C for incubation since most species grew well at 20–30 °C (Table S3). In particular, several species (P. brasilianum, P. decaturense, P. griseofulvum, P. solitum, and Penicillium sp. 13 were detected only during winter, but showed optimal growth at 25–30 °C. All plates were incubated at 25 °C for 7–14 days. We transferred all Penicillium to a new PDA plate. The isolated strains were stored in 20% glycerol at −80 °C at the Seoul National University Fungus Collection (SFC) (Table S1).

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing from isolates

Genomic DNA was extracted from isolated Penicillium strains using the modified cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) extraction protocol80. The PCR amplifications of the ITS and BenA region were performed using primers ITS1F/ITS481 and Bt2a/Bt2b82, respectively. Each PCR reaction was performed in a C1000 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA) following previously described methods5. The PCR products were purified using the ExpinTM PCR Purification Kit (GeneAll Biotechnology, Seoul, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed in both forward and reverse directions using the corresponding PCR primers at Macrogen (Seoul, Korea), using an ABI Prism 3730 genetic analyzer (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA).

Identification of Penicillium isolates

Sequences were assembled, proofread, edited, and aligned using MEGA583. Consensus sequences were deposited in GenBank (Table S1). Molecular identification of species was performed in two steps. First, the sectional position of the strains was determined by comparison of the ITS sequences in a dataset containing sequences of type strains. Next, the BenA sequence data were compared with type strain sequences to identify strains at the species level. Multiple alignments were performed using MAFFT v. 784 and the L-INS-I algorithm. Neighbor joining (NJ) trees were constructed with MEGA 5 using Kimura 2-parameter model85 with 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Diversity analysis by culture-independent approach

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing from environmental DNA (eDNA)

For the culture-independent approach, eDNA was extracted directly from 500 mg of substrate samples (mudflat or sand) using the MoBio PowerSoil DNA isolation kit (MoBio laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Each PCR reaction was performed in a C1000 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) using AccuPower® PCR PreMix (Bioneer) in a final volume of 20 μL, containing 10 pmol of each primer and 1 μl of DNA. For ITS, PCR amplification was performed using the primers ITS3 and ITS481 attached with Illumina sequencing adaptors. The PCR program was as follows: 5 min at 94 °C; 35 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, and 40 s at 72 °C; and a final extension step of 5 min at 72 °C. For BenA amplification, we designed Penicillium specific primers: forward primers BenA-F (ATCGGTGCTGCTTTCTGGTA) and BenA-2F (CGGTGCTGCTTTCTGGTANGT); reverse primers BenA-2R (TGRCCGAARACRAARTTRTCGG) and BenA 300R (GCRTCCATRGTRCCRGGYTC).

The first PCR was performed using primers BenA-F and BenA-2R, followed by a second PCR using primers BenA-2F and BenA 300 R attached with Illumina sequencing adaptors. The program of the first PCR was as follows: 5 min at 94 °C; 35 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 58 °C, and 40 s at 72 °C; and a final extension step of 5 min at 72 °C; the second PCR program was 5 min at 94 °C; 35 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 68 °C, and 40 s at 72 °C; and a final extension step of 5 min at 72 °C. PCR products were confirmed using gel electrophoresis and purified using the ExpinTM PCR Purification Kit (GeneAll Biotechnology, Seoul, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Individual PCR products were quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo, USA) and a total of 300 libraries were pooled. Sequencing was performed with the Illumina MiSeq system (Illumina) at Macrogen (Seoul, Korea). Paired-end sequences were generated and deposited at NCBI Sequence Read Archive (PRJNA529042).

Bioinformatics process and statistical analysis

The Illumina MiSeq generated ITS (ITS-NGS) and BenA (BenA-NGS) sequence data sets were processed using Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) v. 1.8.086. Sequence pairs were assembled using fastq-join and low quality (QV < 20), short (<200 bp) sequences filtered during the de-multiplexing process. Molecular operational taxonomic units (mOTUs) were clustered with 99% similarity threshold and chimera sequences were filtered using de novo clustering in USEARCH 5.2.23687. For each mOTU, the most abundant sequence was chosen as the representative sequence and used for pre-identification using BLAST against type sequences of Penicillium for ITS and BenA. Final identification was conducted based on phylogenetic analysis as described above. Additional chimeric sequences were filtered based on each database using by UCHIME v4.288. Non-fungal, non-Penicillium sequences, and mOTU with less than 10 reads were removed from the analysis. Before the next step, sequences were rarified based on the minimum number of sequences for normalizing dataset. Indices of alpha diversity were calculated for richness (Chao1), diversity and evenness (Shannon’s index) in QIIME.

Statistical tests and graphical plotting were conducted using ggplot289, phyloseq90, and basic packages in R91. Alpha diversities were compared between categories (season, seaside, and substrate) using Wilcox rank sum test adjusted by the false discovery rate (FDR)92. Community structures were compared by Constrained Analysis of Principal coordinates (CAP) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarities. CAP models were constrained by each category with conditioning by the other factors (e.g. ~Seaside + Condition [Season + Source]), and significance was tested by ANOVA-like tests with 999 permutations.

Halotolerance, enzyme activity, and PAH degradation

Halotolerance was determined by measuring the colony diameter of a representative strain of each species on MEA supplemented with ASW instead of distilled water. Each species was inoculated in three-point fashion on MEA with and without ASW using spore suspensions. The plates were incubated at 25 °C and colony diameter was measured after 5 days. Growth difference between MEA with and without ASW was compared.

Endoglucanase, β-glucosidase, and protease activity were assessed for a representative strain of each species using a modified plate screening method69. Endoglucanase and β-glucosidase activity were assayed on Mandels’ medium71, with 1% carboxymethylcellulose (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) and 0.5% D-cellobiose (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) as the primary carbon source, respectively. Protease activity was assayed by growing the fungi for five days on yeast extract agar (Oxoid, MD, USA) supplemented with 1.5% skim milk (Difco-Becton, MD, USA) as the primary carbon source93. To indicate the enzyme activity, the diameters (mm) of clear zones surrounding colonies were measured.

A gallic acid reaction was used as a screening method to determine the capability of degradation of PAHs94. The gallic acid reaction was assayed by growing the fungi on 1.5% MEA (Difco-Becton, MD, USA) supplemented with 5 g L−1 of gallic acid. Each plate was incubated at 25 °C for 14 days. The capability of degradation of PAHs was identified by a color change surrounding the colony. Each value for a strain is the average result from three experiments.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Marine Biotechnology Program of the Korea Institute of Marine Science and Technology Promotion (KIMST) funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (MOF) (No. 20170431).

Author Contributions

M.S.P. and Y.W.L. conceived of the study and design. M.S.P. conducted all experimental work. M.S.P. and S.-Y.O. contributed to data analyses. All authors discussed the results. M.S.P. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors were involved in writing and gave final approval for publication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-49966-5.

References

- 1.Pitt, J. I. The genus Penicillium and its teleomorphic states Eupenicillium and Talaromyces (Academic Press, 1979).

- 2.Frisvad JC, Samson RA. Polyphasic taxonomy of Penicillium subgenus Penicillium. A guide to identification of food and air-borne terverticillate Penicillia and their mycotoxins. Stud. Mycol. 2004;49:1–174. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Visagie CM, et al. Identification and nomenclature of the genus Penicillium. Stud. Mycol. 2014;78:343–371. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paz Z, et al. Diversity and potential antifungal properties of fungi associated with a Mediterranean sponge. Fungal Divers. 2010;42:17–26. doi: 10.1007/s13225-010-0020-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park MS, et al. Marine-derived Penicillium in Korea: diversity, enzyme activity, and antifungal properties. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2014;106:331–345. doi: 10.1007/s10482-014-0205-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicoletti R, Trincone A. Bioactive compounds produced by strains of Penicillium and Talaromyces of marine origin. Mar. Drugs. 2016;14:37. doi: 10.3390/md14020037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park MS, Lee S, Lim YW. A New record of four Penicillium species isolated from Agarum clathratum in Korea. J. Microbiol. 2017;55:237–246. doi: 10.1007/s12275-017-6405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edrada RA, et al. Online analysis of xestodecalactones A–C, novel bioactive metabolites from the fungus Penicillium cf. montanense and their subsequent isolation from the sponge Xestospongia exigua. J. Nat. Prod. 2002;65:1598–1604. doi: 10.1021/np020085c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubrovskaya YV, et al. Extracellular b-D-glucosidase of the Penicillium canescens marine fungus. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2012;48:401–408. doi: 10.1134/S0003683812040059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amend AS, Barshis DJ, Oliver TA. Coral-associated marine fungi form novel lineages and heterogeneous assemblages. ISME J. 2012;6:1291. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richards TA, Jones MD, Leonard G, Bass D. Marine fungi: their ecology and molecular diversity. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2012;4:495–522. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120710-100802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manohar CS, Raghukumar C. Fungal diversity from various marine habitats deduced through culture-independent studies. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2013;341:69–78. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh P, Raghukumar C, Verma P, Shouche Y. Fungal community analysis in the deep-sea sediments of the Central Indian Basin by culture-independent approach. Microb. Ecol. 2011;61:507–517. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9765-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo X, Zhang Q, Zhang X, Zhang J, Gong J. Marine fungal communities in water and surface sediment of a sea cucumber farming system: habitat-differentiated distribution and nutrients driving succession. Fungal Ecol. 2015;14:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.funeco.2014.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao Z, Li B, Zheng C, Wang G. Molecular detection of fungal communities in the Hawaiian marine sponges Suberites zeteki and Mycale armata. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:6091–6101. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01315-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arfi Y, Marchand C, Wartel M, Record E. Fungal diversity in anoxic-sulfidic sediments in a mangrove soil. Fungal Ecol. 2012;5:282–285. doi: 10.1016/j.funeco.2011.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nilsson RH, et al. Taxonomic reliability of DNA sequences in public sequence databases: a fungal perspective. PLoS One. 2006;1:e59. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buée M, et al. 454 Pyrosequencing analyses of forest soils reveal an unexpectedly high fungal diversity. New Phytol. 2009;184:449–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amend AS, Seifert KA, Bruns TD. Quantifying microbial communities with 454 pyrosequencing: does read abundance count? Mol. Ecol. 2010;19:5555–5565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim YW, et al. Assessment of soil fungal communities using pyrosequencing. J. Microbiol. 2010;48:284–289. doi: 10.1007/s12275-010-9369-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samuels GJ, et al. The Trichoderma koningii aggregate species. Stud. Mycol. 2006;56:67–133. doi: 10.3114/sim.2006.56.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoch CL, et al. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:6241–6246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117018109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samson RA, et al. Phylogeny, identification and nomenclature of the genus Aspergillus. Stud. Mycol. 2014;78:141–173. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levin LA, et al. The function of marine critical transition zones and the importance of sediment biodiversity. Ecosystems. 2001;4:430–451. doi: 10.1007/s10021-001-0021-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Musat F, Harder J, Widdel F. Study of nitrogen fixation in microbial communities of oil‐contaminated marine sediment microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;8:1834–1843. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azam F, Malfatti F. Microbial structuring of marine ecosystems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;5:782–791. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim HJ, et al. Species list of Aspergillus, Penicillium and Talaromyces in Korea, based on ‘One Fungus One Name’ system. Kor. J. Mycol. 2016;44:207–219. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sonjak S, Frisvad JC, Gunde-Cimerman N. Penicillium mycobiota in Arctic subglacial ice. Microb. Ecol. 2006;52:207–216. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ding B, Yin Y, Zhang F, Li Z. Recovery and phylogenetic diversity of culturable fungi associated with marine sponges Clathrina luteoculcitella and Holoxea sp. in the South China Sea. Mar. Biotechnol. 2011;13:713–721. doi: 10.1007/s10126-010-9333-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh P, Raghukumar C, Meena RM, Verma P, Shouche Y. Fungal diversity in deep-sea sediments revealed by culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches. Fungal Ecol. 2012;5:543–553. doi: 10.1016/j.funeco.2012.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X, et al. Phylogenetic survey and antimicrobial activity of culturable microorganisms associated with the South China Sea black coral Antipathes dichotoma. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012;336:122–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Behera BC, Mishra RR, Thatoi HN. Diversity of soil fungi from mangroves of Mahanadi delta, Orissa, India. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Res. 2012;2:375–378. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, et al. A high-level fungal diversity in the intertidal sediment of Chinese seas presents the spatial variation of community composition. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:2098. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee S, et al. Fungal diversity and enzyme activity associated with the macroalgae, Agarum clathratum. Mycobiology. 2019;47:50–58. doi: 10.1080/12298093.2019.1580464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suryanarayanan TS, et al. Internal mycobiota of marine macroalgae from the Tamilnadu coast: distribution, diversity and biotechnological potential. Bot. Mar. 2010;53:457–468. doi: 10.1515/bot.2010.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rämä T, et al. Fungi ahoy! Diversity on marine wooden substrata in the high North. Fungal Ecol. 2014;8:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.funeco.2013.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu W, Pang KL, Luo ZH. High fungal diversity and abundance recovered in the deep-sea sediments of the Pacific Ocean. Microb. Ecol. 2014;68:688–698. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0448-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang T, Wang NF, Zhang YQ, Liu HY, Yu LY. Diversity and distribution of fungal communities in the marine sediments of Kongsfjorden, Svalbard (High Arctic) Sci. Rep. 2015;5:14524. doi: 10.1038/srep14524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amann RI, Ludwig W, Schleifer KH. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Visagie CM, et al. Aspergillus, Penicillium and Talaromyces isolated from house dust samples collected around the world. Stud. Mycol. 2014;78:63–139. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Visagie CM, et al. Fifteen new species of Penicillium. Persoonia. 2016;36:247–280. doi: 10.3767/003158516X691627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.King AD, Hocking AD, Pitt JI. Dichloran-rose bengal medium for enumeration and isolation of molds from foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1979;3:959–964. doi: 10.1128/aem.37.5.959-964.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elad Y, Chet I, Henis Y. A selective medium for improving quantitative isolation of Trichoderma spp. from soil. Phytoparasitica. 1981;9:59–67. doi: 10.1007/BF03158330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edel-Hermann V, Gautheron N, Mounier A, Steinberg C. Fusarium diversity in soil using a specific molecular approach and a cultural approach. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2015;111:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2015.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamad I, et al. Culturomics and amplicon-based metagenomic approaches for the study of fungal population in human gut microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:16788. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17132-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 46.Mendoza LM, Neef A, Vignolo G, Belloch C. Yeast diversity during the fermentation of Andean chicha: A comparison of high-throughput sequencing and culture-dependent approaches. Food Microbiol. 2017;67:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dissanayake AJ, et al. Direct comparison of culture-dependent and culture-independent molecular approaches reveal the diversity of fungal endophytic communities in stems of grapevine (Vitis vinifera) Fungal Divers. 2018;90:85–107. doi: 10.1007/s13225-018-0399-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lindahl BD, et al. Fungal community analysis by high‐throughput sequencing of amplified markers–a user’s guide. New Phytol. 2013;199:288–299. doi: 10.1111/nph.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lagier JC, et al. Microbial culturomics: paradigm shift in the human gut microbiome study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012;18:1185–1193. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dumbrell AJ, et al. Distinct seasonal assemblages of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi revealed by massively parallel pyrosequencing. New Phytol. 2011;190:794–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vargas-Gastélum L, et al. Impact of seasonal changes on fungal diversity of a semi-arid ecosystem revealed by 454 pyrosequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015;91:fiv044. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiv044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lim DI, et al. Temporal-spatial variations of water quality in Gyeonggi Bay, west coast of Korea, and their controlling factor. Ocean Polar Res. 2007;29:135–153. doi: 10.4217/OPR.2007.29.2.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeong DH, Shin HH, Jung SW, Lim DI. Variations and characters of water quality during flood and dry seasons in the eastern coast of South Sea, Korea. Korean J. Environ. Biol. 2013;31:19–36. doi: 10.11626/KJEB.2013.31.1.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Korea Hydrographic and Oceanographic Administration (KHOA), 2015, Current chart. http://www.khoa.go.kr/koofs/kor/seawf/sea_wflow.do?menuNo=02&link= (April 10th 2018).

- 55.Taylor MW, Schupp PJ, De Nys R, Kjelleberg S, Steinberg PD. Biogeography of bacteria associated with the marine sponge Cymbastela concentrica. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;7:419–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ali JR, Huber M. Mammalian biodiversity on Madagascar controlled by ocean currents. Nature. 2010;463:653–657. doi: 10.1038/nature08706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cao H, Hong Y, Li M, Gu JD. Phylogenetic diversity and ecological pattern of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in the surface sediments of the Western Pacific. Microb. Ecol. 2011;62:813–823. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9901-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jones EBG. Marine fungi: some factors influencing biodiversity. Fungal Divers. 2000;4:53–73. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li W, et al. Fungal communities in sediments of subtropical Chinese seas as estimated by DNA metabarcoding. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:26528. doi: 10.1038/srep26528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kivlin SN, Winston GC, Goulden ML, Treseder KK. Environmental filtering affects soil fungal community composition more than dispersal limitation at regional scales. Fungal Ecol. 2014;12:14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.funeco.2014.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nikolcheva LG, Barlocher F. Seasonal and substrate preferences of fungi colonizing leaves in streams: traditional versus molecular evidence. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;7:270–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xing XK, Chen J, Xu MJ, Lin WH, Guo SX. Fungal endophytes associated with Sonneratia (Sonneratiaceae) mangrove plants on the south coast of China. For. Pathol. 2011;41:334–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0329.2010.00683.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maciá-Vicente JG, Ferraro V, Burruano S, Lopez-Llorca LV. Fungal assemblages associated with roots of halophytic and non-halophytic plant species vary differentially along a salinity gradient. Microb. Ecol. 2012;64:668–679. doi: 10.1007/s00248-012-0066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Min BM, Je JG. Typical coastal vegetation of Korea. Ocean Polar Res. 2002;24:79–86. doi: 10.4217/OPR.2002.24.1.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee YH, et al. Phytosociological classification of coastal vegetation in Korea. Korean J. Environ. Biol. 2016;34:41–47. doi: 10.11626/KJEB.2016.34.1.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Glassman SI, Wang IJ, Bruns TD. Environmental filtering by pH and soil nutrients drives community assembly in fungi at fine spatial scales. Molecular ecology. 2017;26:6960–6973. doi: 10.1111/mec.14414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oh SY, et al. Guild patterns of basidiomycetes community associated with Quercus mongolica in Mt. Jeombong, Republic of Korea. Mycobiology. 2018;46:13–23. doi: 10.1080/12298093.2018.1454009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.El-Morsy EM. Fungi isolated from the endorhizosphere of halophytic plants from the Red Sea Coast of Egypt. Fungal Divers. 2000;5:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park MS, Lee S, Oh SY, Cho GY, Lim YW. Diversity and enzyme activity of Penicillium species associated with macroalgae in Jeju Island. J. Microbiol. 2016;54:646–654. doi: 10.1007/s12275-016-6324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li Q, Wang G. Diversity of fungal isolates from three Hawaiian marine sponges. Microbiol. Res. 2009;164:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lee H, et al. Halo-tolerance of Marine-derived Fungi and their Enzymatic Properties. Bioresources. 2015;10:8450–8460. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bonugli-Santos RC, et al. Marine-derived fungi: diversity of enzymes and biotechnological applications. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:269. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Damare S, Raghukumar C, Muraleedharan UD, Raghukumar S. Deep-sea fungi as a source of alkaline and cold-tolerant proteases. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2006;39:172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2006.03.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kamat T, Rodrigues C, Naik CG. Marine-derived fungi as a source of proteases. Indian J. Mar. Sci. 2008;37:326–328. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee, Y. Marine algae of Jeju. (Academy Publication, 2008).

- 76.Delille D, Delille B, Pelletier E. Effectiveness of bioremediation of crude oil contaminated subantarctic intertidal sediment: the microbial response. Microb. Ecol. 2002;44:118–126. doi: 10.1007/s00248-001-1047-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arun A, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) biodegradation by basidiomycetes fungi, Pseudomonas isolate, and their cocultures: comparative in vivo and in silico approach. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2008;151:132–142. doi: 10.1007/s12010-008-8160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Leitão AL. Potential of Penicillium species in the bioremediation field. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2009;6:1393–1417. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6041393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang XL, et al. Streptomycindole, an indole alkaloid from a marine Streptomyces sp. DA22 associated with South China Sea sponge Craniella australiensis. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2011;94:1838–1842. doi: 10.1002/hlca.201100104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rogers S. O. & Bendich, A. J. Extraction of total cellular DNA from plants, algae and fungi in Plant molecular biology manual (eds Gelvin, S & Schilperoort, R. A.) 1–8 (Kluwer Academic, 1994).

- 81.White, T. J., Bruns. T., Lee, S. &Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics in PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications (eds Innis, M. A., Gelfand, H., Sninsky, J. J. & White, T. J.) 315–322 (Academic Press, 1990).

- 82.Glass NL, Donaldson GC. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995;61:1323–1330. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1323-1330.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tamura K, et al. MEGA 5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kimura M. A. simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wickham, H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. (Springer, 2016).

- 90.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, https://www.R-project.org/ (2017).

- 92.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Teng WL, Khor E, Tan TK, Lim LY, Tan SC. Concurrent production of chitin from shrimp shells and fungi. Carbohydr. Res. 2001;332:305–316. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(01)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lee H, et al. Biotechnological procedures to select white rot fungi for the degradation of PAHs. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2014;97:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.