Abstract

Minimising the health harms of climate change and optimising universal health coverage will only be achieved through an integrated agenda and aligned solutions, say Renee Salas and Ashish Jha

Key messages.

Climate change is threatening to undermine the achievement of universal health care (UHC) through negative health outcomes and healthcare system disruptions

Climate change and UHC agendas bolster each other as they both strive to improve health and achieve health equity

Many regions of the world with the highest vulnerability to climate change are also those with the lowest UHC coverage. These regions stand to have enormous gains through an integrated approach

UHC plans should work to improve the understanding of climate change, use novel climate sensitive financial frameworks, and incorporate the mitigation of greenhouse gases

They should strive for evidence based climate adaptation that protects health and prioritise health system climate resiliency

The sustainable development goals (SDGs) target many different aspects of human wellbeing; they are interconnected and some might seem to create tension (such as economic growth in SDG 8 and ecological stewardship in SDGs 12 and 15).1 These interconnections are particularly clear for universal health coverage (UHC) (SDG 3.8), which will be substantially harder to achieve without climate action (SDG 13). Climate change threatens the very tenets of UHC; the regions of the world most vulnerable to climate change face the greatest difficulties in achieving it.

United Nations countries agreed to achieve UHC by 2030, which requires optimal access to essential, high quality services without sacrificing affordability.2 This extends beyond merely providing “coverage” and has three main components: a broad set of healthcare services must be accessible, affordable, and of sufficiently high quality to improve health outcomes. To track progress on SDG 3.8, the World Health Organization (WHO) and World Bank created a service coverage index to measure the extent of coverage of “essential health services.” Although coverage has increased globally, only 22 countries currently have a “high coverage” index.2

Climate change is already threatening many health achievements of the past 50 years and will continue to do so at an accelerated pace unless we take action.3 WHO estimates that climate change will cause an additional 250 000 deaths a year by 2030, when taking into account just five exposure pathways (undernutrition, malaria, diarrheal disease, dengue, and heat).4

Our understanding of how climate change affects health is still growing, but we know it will have multiple direct and indirect negative effects, including greater heat related morbidity, undernutrition, increasing water and foodborne illnesses, and mental health problems.5 The largest driver for greenhouse gases globally is the combustion of fossil fuels,6 7 and the resultant air pollution leads to an additional seven million deaths annually.6 Although the health effects of climate change are wide reaching, they can still be mitigated if we take action now.

Beyond direct health effects, climate change will make it more difficult to achieve UHC. The global community has the urgent opportunity to tackle two pressing challenges of our time: UHC and climate change. In this piece, we discuss the pathways through which climate change will create barriers for achieving UHC and how policy makers should mitigate these harms.

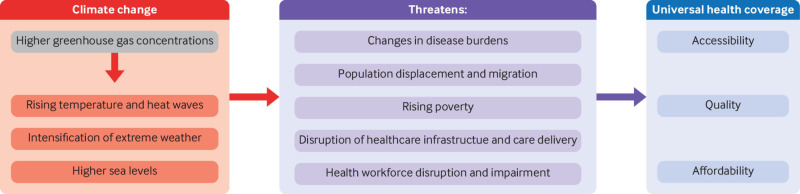

How climate change threatens UHC

Achieving effective UHC even in the absence of climate change is difficult.8 Climate change is a “meta problem,” creating strong headwinds that will make ensuring access to affordable, high quality care more challenging (fig 1). Climate change threatens UHC through five key pathways.

Fig 1.

How climate change threatens the achievement of universal health coverage

Changes in disease burdens (type and distribution)

The effects of climate change will interact with other forces that affect health (box 1). Non-communicable diseases accounted for 71% of global deaths in 2016, and three of the top causes (cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, and diabetes) are exacerbated by climate change, as is mental health.5 9 10 11 Climate change is also increasing the frequency and geographic spread of infectious diseases.

Box 1. Effects of climate change on disease burden.

Non-communicable diseases

A temperature rise of 1°C is linked to a 3.4% rise in cardiovascular mortality, a 3.6% rise in respiratory mortality, and a 1.4% rise in cerebrovascular mortality13

High temperatures are linked to a 6% increase in hospital admissions for coronary artery disease14; cardiovascular events are also associated with exposure to air pollution—such as byproducts from the burning of fossil fuels (for example, fine particulate matter (PM2.5)) and ozone—which is amplified by temperature changes15

Higher temperatures, increased intensity of wildfires, more severe and longer pollen seasons, and ground level air pollution like ozone and PM2.5 increase the burden of respiratory disease6 15

Early data found that diabetes incidence increases by 0.314 per 1000 people for every 1°C rise in temperature,9 although more research is needed

Extreme weather, forced displacement, and violence can precipitate mental health concerns; extreme heat can exacerbate existing conditions11

Chronic kidney disease of unknown origin has been linked to increasing heat stress in many regions, especially in agricultural communities16

Infectious diseases

Vectorial capacity for the transmission of malaria has increased by over 20% in higher elevations in Africa since 1950.3 WHO predicts major future rises in mortality due to climate change related increases in malaria in central and eastern regions of sub-Saharan Africa4

Since the 1950s, vectorial capacity for the transmission of dengue has increased by 7.8-9.6%3

Warmer ambient temperatures have been associated with foodborne illnesses, like salmonella17

A 1°C rise in temperature may lead to a 0.8-2.1% increase in hand, foot, and mouth disease18

Occupational injuries

These disease burdens related to climate change pose added obstacles to UHC by increasing overall use and costs of healthcare.12 As UHC programmes seek to define the essential services that they will cover and to build financial models for their costs, these growing and novel burdens will make appropriate coverage more challenging. In addition, tools used by policy makers for prioritisation in coverage decisions will need to be updated to reflect shifts in disease burdens from climate change.

Population displacement and migration

The number of displaced people is predicted to be 143 million by 2050 in just three regions (Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia), in part because of climate change.21 Displacement might be driven by property loss, resource shortages, and conflicts. These consequences of climate change occur on the backdrop of broader political and societal issues, such as immigration policies and conflict, showing the complexities of the problem.22

Ensuring that a largely stationary population can access a broad set of high quality services is hard enough; delivering UHC to a migratory population is substantially more challenging. Chad, for example, is experiencing increased migration secondary to drought with concerns for strain on public health services and health complications.23 Displaced populations have distinct health related needs, as they may have different rates of conditions, face mental health problems, and bring novel diseases. The influx of people alone might pose a challenge to local healthcare systems—particularly in locations with no or low coverage—as they struggle to manage the increased patient volume and provide culturally sensitive care.

Rising poverty

The World Bank estimates that climate change will push 100 million more people into poverty by 2030 due to factors like property loss, increased health burdens, and decreased crop yields.24 Poorer populations are particularly susceptible to the threats posed by climate change, creating a cycle in which climate change exacerbates existing social and political issues by both creating poverty and trapping people within it.

Worsening poverty will contribute to higher burdens of disease, placing more stress on healthcare systems, and will put greater strains on government budgets for countries seeking to provide affordable, accessible care.

Disruption of healthcare infrastructure and care delivery

Extreme weather events related to climate change, like more intense hurricanes and floods, can cause structural damage or power outages at healthcare facilities (box 2). Even undamaged facilities can be affected by supply chain disruptions—due to factory disruption, increased demand, or transportation disruptions—and subsequent resource shortages.

Box 2. Effects of climate change on healthcare systems.

Low health risk country: hurricane Maria in the United States

Hurricane Maria struck the US in 2017, causing major damage to Puerto Rico. Devastating rainfall and landslides, both attributed to climate change, battered the island.25 Combined with ineffective governance and disaster relief from the US government, the storm took a major toll on the island. The initial death count was 64, but subsequent household survey estimates place the loss of life at nearly 5700.26 The average household went 84 days without electricity, 68 days without water, and 41 days without cellular phone coverage.26

Nearly a third of households reported a disruption to health services, including 14% who were unable to access medications, 10% who were unable to use medical device equipment that required power, 9% who reported closed medical facilities, and 6% who found a lack of doctors. Nearly 9% of the most remote households could not reach emergency medical services by phone.26

Healthcare disruption was not limited to Puerto Rico. Approximately 44% of US intravenous fluid was produced on this island, and damage to the factory led to shortages that lasted months at hospitals throughout the US and other countries.27 The cascading effects of this one storm show how vulnerable supply chains are and the importance of fortifying climate resilience in healthcare systems.

High health risk country: Bangladesh and flooding of the Brahmaputra River

Bangladesh is a low lying, densely populated country with enormous vulnerability to rising sea levels and climate driven extreme weather, including flooding, cyclones, and drought.28 In 2017, climate change (along with other factors, such as deforestation and higher population density) contributed to the flooding of the Brahmaputra River, which destroyed nearly 500 community health clinics. This is catastrophic in a country with approximately five medical doctors and eight hospital beds per 10 000 people.29 The destruction of already limited healthcare infrastructure had a drastic effect on access to care.

Solutions are difficult, as the climate driven weather is constantly creating and destroying floating islands, which makes establishing permanent clinics or hospitals impossible. Forced to develop innovative solutions, some communities have launched “floating hospitals.”28 These consist of boats that bring basic medical services to people who live in the riverine islands. A boat can see about 60 000 patients a year over hundreds of miles. Countries already at extreme risk, like Bangladesh, represent early examples of the enormous climate change related healthcare challenges we face and the need for creative solutions.

Infrastructure damage limits a facility’s ability to deliver essential, high quality services. People might be unable to access care due to transportation difficulties, caused by road damage or the unavailability of emergency medical services. Systems might face barriers to maintaining public health and preventive strategies, such as the surveillance of emerging threats. These many obstacles are likely to place additional cost burdens on health systems, which will trickle down to the individual or insurance provider, further exacerbating affordability concerns.

Health workforce disruptions and impairments

There is already a shortage and maldistribution of well trained healthcare workers around the world.30 This is likely to be exacerbated by climate change, as the workforce is also affected by the forces driving migration. Quality of care is poor in many settings, with high rates of misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatments, which is probably due to inadequate training.31 As outlined in box 3, the workforce might be further impaired through cognitive effects of climate change and knowledge deficits, causing substantial problems in areas that already lack high quality training.

Box 3. Effects of climate change on the health workforce.

Climate sensitive health and travel concerns

Healthcare workers might provide lower quality of care if they have impaired cognitive function due to climate change (extreme heat,32 nutritional deficiencies, and infectious diseases). Heat is of particular concern where air conditioning is permanently or frequently unavailable or water for cooling is scarce. Healthcare workers might also have difficulty reporting to work during extreme weather situations, such as when flooding disrupts roadways.

Climate change and health knowledge deficits

Climate change alters existing disease burdens through various routes. Although a growing proportion of the healthcare workforce recognises that climate change negatively affects health, there are gaps in understanding around the details.33 34 Only 19% of disease control workers in China understood that poor people were at greater risk of climate change related health problems. In addition, only one-third had a good understanding of how climate change affects the transmission of infectious diseases.34

The healthcare workforce is one of the most important factors in UHC—both the availability of providers and the quality of care they provide. Shortages caused by geographic redistribution of providers might hinder access to care, whereas inadequate training might lead to misdiagnosis, ineffective disease surveillance, and, ultimately, harm to patients.

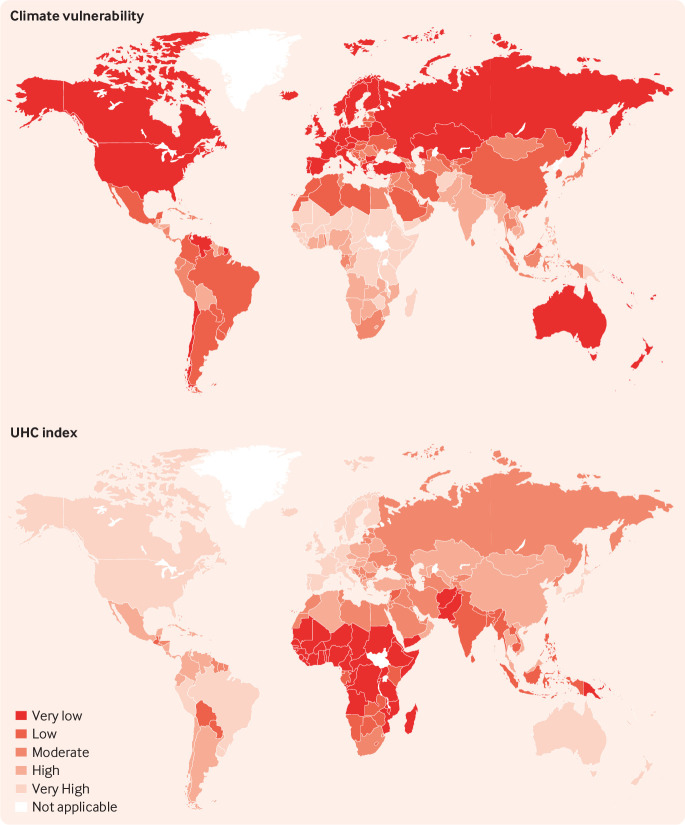

Vulnerable countries

The countries that are most vulnerable to climate change35 are often those that face the greatest barriers to achieving UHC (fig 2). This is not surprising—both are related to the country’s economic strength and availability of resources. Because of the unique challenges they face, these regions have enormous opportunity to take a more integrated approach to their agendas. This would not be easy; given the financial restraints many of these countries already face related to healthcare, they might see tackling climate change as impossible. Implementing and optimising UHC, however, is a key strategy to minimise the health burdens of climate change and will probably be financially beneficial in the long run. Some countries might benefit more than others, but all can make immense gains from taking an integrated systems approach.

Fig 2.

A: Global map of climate change vulnerability. This map uses climate change vulnerability data from the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN) Country Index,35 which is based on indicators of adaptive capacity, sensitivity, and exposure and includes health, food, ecosystems, habitat, water, and infrastructure. Countries are categorised by quintile. B: Global map of universal health coverage. This map uses the universal health coverage index of essential service coverage data from the World Health Organization,36 which is based on indicators for reproductive, maternal/newborn/child health, infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases, service capacity, and access. Countries are categorised by quintile.

Integrated solutions

Countries have already taken important steps towards tackling climate change through the Paris Agreement, which was called “the strongest health agreement of this century” by WHO and outlines the benefits of climate mitigation for health and development.6 Global leaders can and must incorporate climate related threats into their considerations related to UHC (box 4).

Box 4. Sample solutions that tackle both the universal health coverage (SDG 3.8) and climate action (SDG 13).

Improved understanding and integrated agendas

Understand how individuals use healthcare for climate sensitive conditions and determine how different UHC models will affect this

Gather experts across sectors (as in the One Health approach) to develop an agenda for tackling these issues together

Develop joint metrics tracking both SDGs (3 and 13)

Novel financial frameworks

Use carbon pricing that includes climate driven health and healthcare system costs

Finance UHC from the elimination of fossil fuel subsidies37 and carbon pricing

Climate change mitigation

Frame transition to renewable energy around the anticipated health and health equity benefits

Ensure that transition to renewable energy is urgent and extensive in healthcare facilities, fuelled by advocacy from healthcare professionals and political leaders

Broad divestment from fossil fuel companies to numerous sectors, especially healthcare

Adaptation to climate change

Data driven approach to identifying those most vulnerable to heat exposure in a city, how they access care, and how the public health infrastructure can best protect them through adaptation interventions

Translate data into effective surveillance systems and efficient sharing of emerging health concerns across borders

Train medical professionals in skills that transcend current specialty boundaries, such as disaster preparedness training for hospitalists, and knowledge of emerging climate sensitive threats, such as new geographic distributions of infectious diseases

Health system resilience

Map out climate hazards, such as flooding and other extreme weather implications, for local regions using different future climate models (eg, moderate to severe)

Redesign facilities (eg, protection from flooding), relocate generators (eg, roof placement), and engage with the local health community (eg, coordination between local hospitals)

Create incentives for strategic geographic placement of the health workforce and use health technologies like predictive staffing models and telemedicine

Improved understanding and integrated agendas

New research to facilitate data driven solutions would be helpful, but we already have sufficient understanding to integrate the UHC and climate action agendas. These two communities need open dialogue with each other—with cross sectorial representation—and to push jointly for bold and innovative solutions.

Novel financial frameworks

Financial limitations are often seen as a major barrier to climate action, but this field actually provides a major opportunity for economic benefit. We need forward thinking financial solutions to stimulate action in conjunction with political will. By 2030, climate action is estimated to create $23 trillion (£19 trillion; €21 trillion) in investment opportunity in just 21 emerging market economies21—and this may translate to healthcare. We also need to include health and healthcare climate burdens in discussions around the economics of climate action. As of February 2019, 46 national and 28 subnational jurisdictions have implemented or planned carbon pricing, with novel opportunities to integrate with UHC (box 4).21

Climate change mitigation

A rapid transition to renewable energy, which is both feasible and cost effective, would have direct health benefits now and would minimise health burdens in the future. But we need political will to take the urgent and bold steps necessary. Mitigation must also specifically occur in the health sector, which contributes to a disproportionate amount of carbon emissions.39 Health professionals can play an important role in advocating for policies that will incentivise this transition.

Adaptation to climate change

UHC is itself a fundamental adaptation intervention as it mitigates the negative health burdens of climate change. Meanwhile, we need investment in research to understand the health risks of climate change in local populations. There then needs to be political and fiscal support to translate this research into interventions and infrastructure that protect the most vulnerable. Another essential component of achieving UHC is the development of a dynamic health workforce that can respond to the changing needs of a region. Healthcare workers will be on the front lines of disaster response and disease surveillance efforts, so appropriate education on local climate health is critical to improve their adaptive capacity.

Health system climate resiliency

As climate change exacerbates existing threats and exposes new vulnerabilities, health systems must introduce forward thinking, data driven resiliency measures that are based on the unprecedented challenges of the future. This mandates global assessments of climate hazards and health system vulnerabilities, which can then be tailored to unique local environments. The results of these assessments can then be implemented into strategic capital investment priorities and appropriate health workforce management. Meanwhile, creative workforce models and integration of technology will further bolster health system capacities.

Conclusions

We are at an important point in time where action—or inaction—on the intersecting issues of climate change and UHC will drive the health of nations for decades to come. Estimates show that we have about a decade to decrease greenhouse gas emissions to avoid the most catastrophic health outcomes.40 Thus, the opportunities to transform health are enormous, and the time to act is now. As global decision makers aim to improve the health and quality of life for all people, they must not overlook the effects that climate change will have on disease burden and healthcare infrastructure. Only through bold, innovative, and cross disciplinary action can we tackle these unprecedented complex challenges and ensure a healthier world for future generations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathryn Horneffer and Robert J Redelmeier for their assistance.

Contributors and sources: RNS is an emergency medicine physician and researcher focused on the health and healthcare system effects of climate change. AKJ is an internal medicine physician and researcher focused on quality and cost effectiveness of healthcare, both globally and in the United States. Both authors contributed to the conception, preparation, review, and approval of this manuscript. The sources of information used to create this manuscript include the peer-reviewed literature and governmental or agency reports. AKJ is the guarantor.

Patient involvement: No patients were involved.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no competing interests to declare.

This article is part of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on an idea from the Harvard Global Health Institute. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication. Harvard Global Health Institute paid the open access fees.

References

- 1. Hickel J. The contradiction of the sustainable development goals: Growth versus ecology on a finite planet [in press]. Sustain Dev 2019. 10.1002/sd.1947 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO), The World Bank Tracking universal health coverage: 2017 global monitoring report. World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, et al. The 2018 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: shaping the health of nations for centuries to come. Lancet 2018;392:2479-514. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32594-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization (WHO) Climate and health country profiles: a global overview. World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haines A, Ebi K. The imperative for climate action to protect health. N Engl J Med 2019;380:263-73. 10.1056/NEJMra1807873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization (WHO) COP24 special report: health and climate change. World Health Organization, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Global greenhouse gas emissions data. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data

- 8. Bloom G, Katsuma Y, Rao KD, Makimoto S, Yin JDC, Leung GM. Next steps towards universal health coverage call for global leadership. BMJ 2019;365:l2107. 10.1136/bmj.l2107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blauw LL, Aziz NA, Tannemaat MR, et al. Diabetes incidence and glucose intolerance prevalence increase with higher outdoor temperature. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2017;5:e000317. 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization (WHO) World health statistics 2018: monitoring health for the sustainable development goals (SDGs). World Health Organization, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berry HL, Bowen K, Kjellstrom T. Climate change and mental health: a causal pathways framework. Int J Public Health 2010;55:123-32. 10.1007/s00038-009-0112-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wondmagegn BY, Xiang J, Williams S, Pisaniello D, Bi P. What do we know about the healthcare costs of extreme heat exposure? A comprehensive literature review. Sci Total Environ 2019;657:608-18. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bunker A, Wildenhain J, Vandenbergh A, et al. Effects of air temperature on climate-sensitive mortality and morbidity outcomes in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence. EBioMedicine 2016;6:258-68. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bai L, Li Q, Wang J, et al. Increased coronary heart disease and stroke hospitalisations from ambient temperatures in Ontario. Heart 2018;104:673-9. 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Watts N, Adger WN, Agnolucci P, et al. Health and climate change: policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 2015;386:1861-914. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60854-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sorensen C, Garcia-Trabanino R. A new era of climate medicine—addressing heat-triggered renal disease. N Engl J Med 2019;381:693-6. 10.1056/NEJMp1907859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Milazzo A, Giles LC, Zhang Y, Koehler AP, Hiller JE, Bi P. Factors influencing knowledge, food safety practices and food preferences during warm weather of Salmonella and Campylobacter cases in South Australia. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2017;14:125-31. 10.1089/fpd.2016.2201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wei J, Hansen A, Liu Q, Sun Y, Weinstein P, Bi P. The effect of meteorological variables on the transmission of hand, foot and mouth disease in four major cities of Shanxi province, China: a time series data analysis (2009-2013). PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015;9:e0003572. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Varghese BM, Barnett AG, Hansen AL, et al. The effects of ambient temperatures on the risk of work-related injuries and illnesses: Evidence from Adelaide, Australia 2003-2013. Environ Res 2019;170:101-9. 10.1016/j.envres.2018.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Varghese BM, Hansen A, Bi P, Pisaniello D. Are workers at risk of occupational injuries due to heat exposure? A comprehensive literature review. Saf Sci 2018;110:380-92. 10.1016/j.ssci.2018.04.027 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The World Bank. Climate change. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/climatechange/overview

- 22. Bowles DC, Butler CD, Morisetti N. Climate change, conflict and health. J R Soc Med 2015;108:390-5. 10.1177/0141076815603234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stapleton S, Nadin R, Watson C, Kellett J. Climate change, migration and displacement: the need for a risk-informed and coherent approach. Overseas Development Institute, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hallegatte S, Bangalore M, Bonzanigo L, et al. Shock Waves: Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty. World Bank Group, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Keellings D, Ayala JJH. Extreme rainfall associated with hurricane Maria over Puerto Rico and its connections to climate variability and change. Geophys Res Lett 2019;46:2964-73 10.1029/2019GL082077 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kishore N, Marqués D, Mahmud A, et al. Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. N Engl J Med 2018;379:162-70. 10.1056/NEJMsa1803972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Salas RN, Knappenberger P, Hess J. Lancet countdown on health and climate change brief for the United States of America. Lancet Countdown, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sampath N. Floating hospitals treat those impacted by rising seas. Natl Geogr 2017. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2017/03/floating-hospitals-bangladesh-climate-change-refugees/

- 29.Global Health Observatory. Countries: Bangladesh. https://www.who.int/countries/bgd/en/

- 30. Guilbert JJ. The World Health Report 2006: working together for health. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2006;19:385-7. 10.1080/13576280600937911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Das J, Woskie L, Rajbhandari R, Abbasi K, Jha A. Rethinking assumptions about delivery of healthcare: implications for universal health coverage. BMJ 2018;361:k1716. 10.1136/bmj.k1716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cedeño Laurent JG, Williams A, Oulhote Y, Zanobetti A, Allen JG, Spengler JD. Reduced cognitive function during a heat wave among residents of non-air-conditioned buildings: an observational study of young adults in the summer of 2016. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002605. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wei J, Hansen A, Zhang Y, et al. Perception, attitude and behavior in relation to climate change: a survey among CDC health professionals in Shanxi province, China. Environ Res 2014;134:301-8. 10.1016/j.envres.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wei J, Hansen A, Zhang Y, et al. The impact of climate change on infectious disease transmission: perceptions of CDC health professionals in Shanxi Province, China. PLoS One 2014;9:e109476. 10.1371/journal.pone.0109476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.University of Notre Dame. ND-GAIN: Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative. https://gain.nd.edu/

- 36.World Health Organization (WHO). Universal health coverage index of essential service coverage (%). http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.imr.UHC_INDEX_REPORTED?lang=en

- 37. Gupta V, Dhillon R, Yates R. Financing universal health coverage by cutting fossil fuel subsidies. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e306-7. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00007-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pichler P-P, Jaccard IS, Weisz U, Weisz H. International comparison of health care carbon footprints. Environ Res Lett 2019;14:064004 10.1088/1748-9326/ab19e1 . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Special report on global warming of 1.5°C (SR15). 2018. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/