Abstract

Liana Woskie and Mosoka Fallah use the Ebola outbreak in Liberia to better understand the role and consequences of distrust in health systems and how it affects universal health coverage

Key messages.

Acute disease outbreaks often shed light on underlying health system failures

High rates of distrust health system distrust have been exposed in both recent Ebola epidemics.

Health system distrust can make people less willing to use health services in both acute and non-acute situations

To build acceptability countries must routinely assess rates of distrust and its drivers, encourage efforts that build confidence, and trust patients’ decision making processes

Epidemics of infectious disease often highlight underlying weaknesses in health systems. The two most recent outbreaks of Ebola virus disease, for example, exposed high levels of distrust that contributed to the spread of disease but also have implications for universal health coverage. By the end of August 2019 just over a quarter of deaths from Ebola in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) had occurred outside treatment centres.1 Since the treatment protocol includes isolation, this suggests that people were refraining from seeking care when symptoms arise or not remaining in treatment for the suggested duration.

One reason for this is lack of trust in institutions, and specifically health systems. Surveys conducted in North Kivu, the centre of the outbreak, during late 2018 to early 2019 found that people viewed Ebola as a government scheme to marginalise certain groups or as part of a business to profit aid workers, researchers, and government officials.2 These findings parallel those of a similar study conducted in Liberia during the west African Ebola crisis in 2014-15.3 In Liberia the distrust was evident before the crisis, with another survey finding that about half of respondents did not believe that they could obtain needed services for themselves or their children if they became sick.4

Low rates of early care seeking are thought to have increased mortality from Ebola. But early presentation is also fundamental to mitigating unnecessary morbidity and mortality associated with diseases from diabetes to HIV/AIDs. We know surprisingly little about the state of health system distrust or what drives it. We use the Ebola outbreak in West Point, Liberia (the largest slum in the country’s capital city) to illustrate how distrust in the health system undermined care coverage when it was most needed and lay out three strategies to better understand and tackle distrust within the broader context of universal health coverage (UHC).

Distrust in the context of UHC

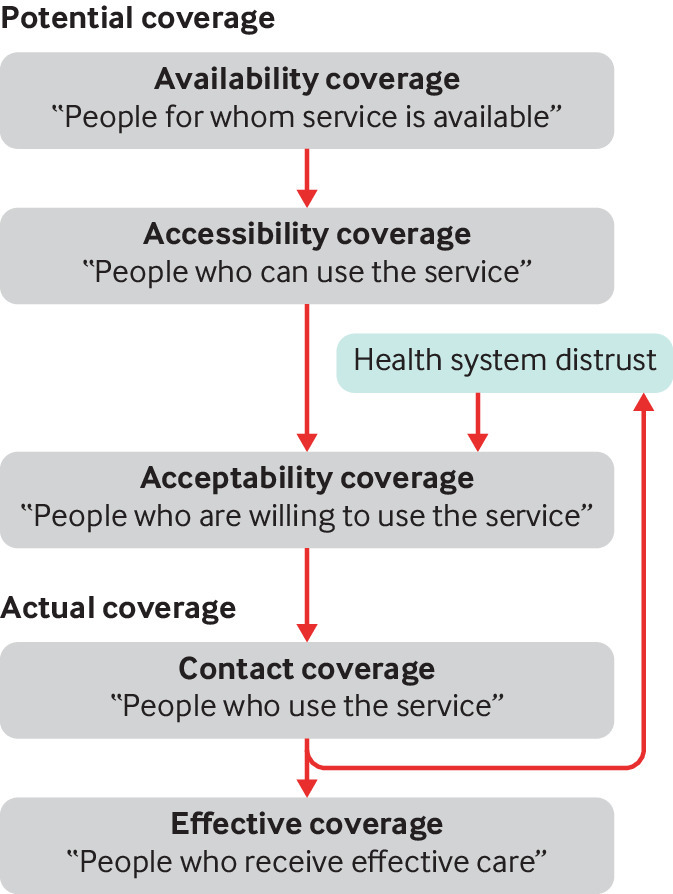

The goal of UHC is to ensure that the whole population, including the most disadvantaged groups, receives essential health services that are good quality. Tanehashi’s 1978 framework for assessing healthcare coverage sets out five stages from available to effective (fig 1).5 6 Health system distrust is a mediating factor that may drive down the willingness of people to use health services (“acceptability coverage”). If people find health services to be unacceptable and are unwilling to use them, they may remain uncovered even if services are technically in place.5

Fig 1.

Tanehashi’s stages of healthcare service coverage

Consequences of distrust

In August 2014, the transmission of Ebola in West Point was seen as a potentially insurmountable threat to containing the disease.7 The combined historical challenges of marginalisation, poor public health infrastructure, and poor healthcare had resulted in residents of West Point seriously doubting the health system (box 1).

Box 1. Health system context in West Point, Liberia before Ebola*.

Before the 2014 Ebola outbreak and after the Liberian civil war, West Point was known as a strong political base of George Weah, leader of the then opposition party Congress for Democratic Change. Residents of West Point felt that the government was not operating in their interests because of their political support for Weah and a history of low social service provision. The area had inadequate refuse collection, sewage infrastructure, and latrines. The population (about 80 000 residents) was served by only one health centre, a joint government and Catholic run clinic that provided free care.

The Liberian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MOHSW) developed its first national health policy and plan in 2007, which was centred on a basic package of health services. The policy was rolled out in about 80% of health facilities. However, communication about what was covered was unclear.8 The availability of services increased under the scheme,9 but the experience of residents of West Point was mixed. Although all government health facilities were meant to be free, a survey in 2014 by the Community-Based Initiative, an organisation set up to engage the community in tackling Ebola, found that many community members were paying large sums out of pocket. In addition, when people sought care, the clinic was often unable to meet their needs—for example, drugs to treat postpartum haemorrhage were often not available. Although not well documented, data from the national demographic and health survey suggested that maternal mortality had risen from a baseline of about 770/100 000 births to 970/100 000 in 2013. The poor service delivery was compounded by concerns that people would not be treated with respect when they did seek care.

A lack of clear expectations, miscommunication regarding what should be expected from the health system, and an inability to deliver quality services under earlier health schemes set a challenging baseline. When Ebola arrived, there was little reason for West Point residents to trust the system when told about a strange new disease that required strict isolation from their families.

Care seeking and cooperation

Distrust in government (including government provided healthcare) and exposure to negative Ebola related experiences were among the most important determinants of care seeking in Monrovia, Liberia, towards the end of the Ebola outbreak.10 In West Point this also extended to life saving medical advice, such as reporting of deaths and comprehensive contact tracing (box 2).

Box 2. Consequences of distrust in West Point—a personal account*.

During the Ebola outbreak I worked with the Community-Based Initiative (CBI), an organisation started to mitigate distrust and mobilise communities in the fight against Ebola. In August 2018 the CBI discovered that secret burials were taking place in West Point, and I alerted the WHO representative in Liberia, Nestor Ndayimirije. He proposed a secret meeting outside West Point to gather information and protect people who might provide us with valuable insight into what was going on. These people met us at a private location and confirmed the secret burials. As a result we moved in with the burial team and picked up nine corpses.

We then arranged a meeting with community leaders, youth leaders, and women’s leaders. They told us they did not think Ebola was in West Point. We asked them about the nine bodies we had taken in one day. An elder responded that nine deaths in a day is normal.

Our inability to initiate basic public health measures to reduce the disease burden among people in West Point who had major sanitation problems meant that death was normal. Why should they believe that these new deaths were due to a new phenomenon called Ebola? When Ebola services were introduced in West Point, many people interpreted these efforts, such as holding centres, as a government strategy to introduce Ebola to the population because of its political views.

Building trust

Perceptions about healthcare in the Ebola treatment unit began to shift in late October. We had worked on community engagement in West Point through the Community-Based Initiative (CBI), an organisation we started to mitigate distrust and mobilise communities in the fight against Ebola. As people recognised that Ebola was a real threat, there was some reversal of the distrust emanating from West Point, which had previously led to the ransacking of the centre used to treat residents with Ebola.

However, as late as mid-October, we found people were still hiding corpses and secretly taking them out of West Point for burial. We decided to hold a focus group discussion with the elders and community leaders. One of the key reasons people provided for secrecy around burial was rumours that no one ever returned from the Ebola treatment unit alive. They went on to inform us that they were told that when relatives went to the unit they were killed, after which their heads were cracked open and their bodies burnt without anyone informing their loved ones. One of the local chiefs looked at me and said, “Dr Fallah, I won’t lie to you, if my relative is sick or dying in West Point, I will run away with him instead of taking him to that unit.”

*Reflections from Mosoka P Fallah based on work conducted with the Community-Based Initiative (CBI) that was founded in 2014 to shift Ebola transmission dynamics and funded by the United Nations Development Programme.

More recently, a population based study in the DRC identified low trust in institutions and belief as being associated with a decreased likelihood of adopting preventive behaviours, including acceptance of Ebola vaccines.11 Similar findings were reported in a survey of other African countries: “A staggering proportion of citizens in most of the sampled countries reported having gone without medicines or medical treatment in the previous year, and going without health care was most strongly correlated with views on health services.”12 Distrust in the health system, and government more broadly, has been associated with underuse of recommended preventive services.13 This is relevant for Ebola, where timing of presentation greatly affects chances of survival, and for other acute and chronic conditions. Acceptance of and adherence to antiretrovirals, for example, have been found to be significantly associated with trust in medications, trust in the healthcare system, and a patient’s relationships with physicians and peers.14

Informal care seeking

A 2008 study in Liberia found that low confidence in the government was correlated with a greater reliance on the informal healthcare sector.4 In addition, people were less likely to report confidence in the health system if they were in the lowest wealth group.4 Earlier research found that informal healthcare visits in Liberia decreased with a person’s wealth and satisfaction with the formal health system.15 These factors may be related—wealthier people may get better care, be more satisfied with that care, and, in turn, be more trusting of the health system. Regardless, high rates of informal care seeking can be challenging for health ministries working to achieve UHC. How many people receive their care through informal sources, and how good that care is, is difficult to quantify. As such, it is rarely accounted for in assessments of coverage.16

In addition, when informal care seeking becomes normal, it is difficult to change this behaviour quickly in situations of population risk and acute individual need. Such situations require a centralised strategy to communicate to health providers, coordinate care, and ensure a high level of quality. Although a population may have “contact coverage” or, in some cases, even “effectiveness coverage” through the informal sector, high rates of informal care seeking therefore pose challenges to UHC.

Harm to the health system

In extreme instances, high levels of distrust may threaten health providers. For example, the city of Butembo in DRC saw armed assaults on Ebola treatment centres, the murder of a WHO doctor, and frequent attacks on Ebola vaccination teams.17 These attacks may have been motivated by misinformation, but high levels of underlying distrust in the health system seem to be an important factor.17 Responders were forced to pause activities such as active case finding, contact tracing, and even the administration of vaccines. The attacks affected who was willing to work in the area as well as the costs of providing health services.

Similar problems affect other countries that are striving to ensure universal coverage. Violence against doctors in both east and south Asia, for example, seems to have increased over the past 10 years with doctors in India, China, Pakistan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka all stating concern for their physical safety.18 The population’s lack of trust in medical institutions has been suggested to be a driver of this violence.18 In China, physicians have reported high exposure to verbal abuse, threats of assault, and physical assaults, leading to emotional exhaustion and lower job satisfaction, with many intending to leave their role.19 Nurses are also affected, with 7.8% of nurses in a 2015 Chinese study reporting physical violence and 71.9% reporting non-physical abuse in the preceding year.20 Most perpetrators were patients or their relatives. As news of these events spreads, there is concern that they may breed more fear and insecurity and contribute to further loss of confidence in the health system.21

Looking forward: a health systems approach

Many drivers of distrust in public institutions lie outside the purview of the health system, such as weak state capacity or history of civil unrest and war.22 It is logical that populations faced with geographical constraint who are poor and consistently neglected by the public sector will have limited trust in government. However, below we focus on historical betrayals of trust committed by or within the health system that could be targeted to help reach universal coverage.

Routinely assess rates of distrust and drivers

Pandemic risk models have begun to quantify the effect of non-epidemiological factors on disease spread.23 Efforts to assess the potential effect of UHC investments may benefit from a similar strategy. Although trust is often considered a qualitative concept, we do have methods to routinely assess it. In 2013, a systematic review of scales and indices identified 45 measures of trust within the health system.24 Among validated scales, the group-based medical mistrust scale, medical mistrust index, and healthcare system distrust scale were most commonly used.25 Table 1 give some examples of the questions and the different contexts in which they were applied.

Table 1.

Example questionnaire items that assess aspects of trust in health system24

| Example questionnaire items | Surveyed population | Object of trust |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence in service | “Despite my unfamiliarity with doctors, nurses, and hospitals, I feel very confident about my treatment.” | Elderly US population with chronic disease26 | Treatment |

| “If you or your child is very sick tomorrow, can you get the health care you need?” | General household sample, rural Liberia4 | Healthcare system | |

| Competence | “Patients receive high quality medical care from the Health Care System” | African American general sample, Philadelphia,USA27 | Healthcare system |

| “I think my doctor may not refer me to a specialist when needed” | General national population,USA28 | Physicians | |

| “How well is the government doing in providing health care?” | General household sample, rural Liberia4 | Government | |

| Honesty and integrity | “If a mistake were made in my health care, the health care system would try to hide it from me.” | General population (jurors waiting at Municipal Court of Philadelphia)29 | Healthcare system |

| “Patients have sometimes been deceived or misled at hospitals” | Random sample of residents with heart conditions in Baltimore City, USA30 | Hospitals | |

| “Medical decisions are influenced by how much money [my provider] can make” | General population: villagers with and without insurance, Cambodia31 | Healthcare providers |

Given the prevalence of distrust in historically marginalised populations, it is important to thoughtfully adapt these tools to new contexts and disaggregate data to identify what is driving that distrust. Patient level factors that drive distrust are not wholly predictable or consistent across contexts. Race may be an important factor in informing health system distrust in the US whereas caste or religion may be more relevant in India. Patient level factors can even have varying within countries. For example, in China a population based study found that high education tracked with high distrust, but another study among people who had received care in Shanghai hospitals found that more education was correlated with more trust.32 33 It also matters who measures distrust and how. It can be particularly problematic when a distrusted group (eg, government actors in a fragile state) is associated with data collection.

Regardless, we lack a comprehensive picture of what drives distrust in countries that are working to reach UHC. The drivers of distrust are diverse—people may doubt the integrity of a ruling party or may have been harmed when seeking healthcare in the past—and require different strategies. We currently lack the data to disentangle distrust and strategically address the problem.

Encourage efforts to build underlying confidence

Three global reports released in 2018 broadly defined high quality care as safe, effective, and patient centred; the reports highlighted strikingly high rates of poor quality care across low and middle income countries,34 accounting for between 5.7 and 8.4 million deaths a year.35 We lack a similar quantification for patient centred care, but studies indicate that disrespect and abusive treatment of patients is common.36 A study in Liberia found that people with low confidence in the health system were more likely to have been dissatisfied with their last health visit.4 Traumatic experiences during Ebola treatment were also found to be associated with distrust.37 Earlier work, such as a 2011 analysis of citizens’ perceptions of health systems in 20 sub-Saharan African countries found that quality of care was strongly associated with public opinion of the overall health system.38 There are limitations on how accurately patients can evaluate quality of care, but receipt of poor quality care and patients’ experiences of care seem to inform health system distrust.

Improving quality of care offers potential to counter distrust. For example, in Liberia, once people who survived Ebola returned to their communities shared their experiences, perceptions of the healthcare system shifted (box 3).

Box 3. Community input to counter distrust*.

By October 2014 West Point residents had began to understand that Ebola was real, but distrust in the system persisted and people still did not go to the Ebola treatment unit when they had symptoms. As Ebola spread, the Community-Based Initiative was faced with a serious dilemma and ran the risk of undermining the trust that we had built over the past two months. We asked residents of West Point whether showing them people from their community who had survived Ebola survivors would change their minds about the treatment unit, and they said it would.

The following week, West Point organised a large town hall meeting with local leaders, youth, women, and children. Eleven Ebola survivors from West Point shared their experience and the role that treatment played in their survival.

The chief who had previously told me he would run away with his relatives instead of going to the treatment unit (box 2) turned to us and said, “Now I see with my own eyes and believe in the unit.” By the end of October, we had moved 28 patients with Ebola to the unit by working with the elders and chiefs. They were the last group of confirmed Ebola cases in West Point. For us, this reinforced that access to high quality healthcare with visible results has the propensity to shift distrust in the health system.

*Reflections from Mosoka P Fallah based on work conducted with the Community-Based Initiative (CBI) that was founded in 2014 to shift Ebola transmission dynamics and funded by the United Nations Development Programme.

Simply put, health systems may need to prove their worth more actively. This can be done in various ways, such as providing incentives for known drivers of trust, including provision of correct and safe care and ensuring positive patient experiences. Highlighting success and improving transparency are also important.

Trust patients and engage in true partnership

For populations with low trust in the formal sector, it is critical to understand what patients do trust and why. Informal providers may be more readily accessible to rural populations or people living in slums, and they may also be more “acceptable” because of concerns about disrespect, abuse, or poor quality services. In some contexts, care provided in the informal sector may even be of comparable standard to that in the formal sector.39 It is important not to assume that patients are naive in their assessment of, and corresponding choices in, healthcare. Strategies that treat communities themselves as the primary barrier to ensuring care coverage (eg, through behaviour change) may lose sight of fundamental problems with the health system to which the population is responding.

It is critical to engage with communities—not just educate and inform. This should include an honest assessment of where people choose to seek care and why. It should take population concerns seriously and be guided by those who express distrust in the health system. This is challenging in conflict situations, which also highlights the need to more systematically capture strategies that work.

Conclusion

Ebola provides a stark example, but distrust undermines investments in UHC across the care continuum. Health system distrust is not fully understood but seems to be partly driven by the health system itself; it is both historically grounded and highly rational. This should raise concern, but it also provides cause for optimism. We must act on the modifiable causes of distrust if we want to deliver on the promise of UHC, providing not just superficial coverage but the high quality healthcare that people want.

Contributors and sources: LRW and MPF worked on the Harvard-LSHTM Independent Panel on the Global Response to Ebola in 2015 and 2016 as well as related work with the ministries of health from the three most affected countries. Building on this, LRW and MPF conceived of the paper. LRW drafted the paper. MPF reviewed, edited, and oversaw the paper. MPF led Ebola community based initiatives in West Point slum, where he grew up. These activities were run through the Community-Based Initiative that was founded in 2014 to shift Ebola transmission dynamics and funded by the United Nations Development Programme. Some aspects of this work have been described previously.7 LRW worked on the team commissioned by the National Academy of Medicine to generate data for its evaluation of low and middle income country health system quality in Crossing the Global Quality Chasm.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on an idea from the Harvard Global Health Institute. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication. Harvard Global Health Institute paid the open access fees.

References

- 1.Unicef. DRC Ebola situation report, 2 Sep 2019. https://www.unicef.org/appeals/files/UNICEF_DRC_Humanitarian_SitRep_Ebola_2_Sept_2019.pdf

- 2. Building trust is essential to combat the Ebola outbreak. Nature 2019;567:433-433. 10.1038/d41586-019-00892-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blair RA, Morse BS, Tsai LL. Public health and public trust: Survey evidence from the Ebola Virus Disease epidemic in Liberia. Soc Sci Med 2017;172:89-97. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Svoronos T, Macauley RJ, Kruk ME. Can the health system deliver? Determinants of rural Liberians’ confidence in health care. Health Policy Plan 2015;30:823-9. 10.1093/heapol/czu065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hogan DR, Stevens GA, Hosseinpoor AR, Boerma T. Monitoring universal health coverage within the Sustainable Development Goals: development and baseline data for an index of essential health services. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e152-68. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30472-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tanahashi T. Health service coverage and its evaluation. Bull World Health Organ 1978;56:295-303. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2395571/pdf/bullwho00439-0136.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fallah M, Dahn B, Nyenswah TG, et al. Interrupting Ebola transmission in Liberia through community-based initiatives. Ann Intern Med 2016;164:367-9. 10.7326/M15-1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Petit D, Sondorp E, Mayhew S, Roura M, Roberts B. Implementing a basic package of health services in post-conflict Liberia: perceptions of key stakeholders. Soc Sci Med 2013;78:42-9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Government of Liberia. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Community health survey for health seeking behaviour and health financing in Liberia. Monrovia, 2008.

- 10. Morse B, Grépin KA, Blair RA, Tsai L. Patterns of demand for non-Ebola health services during and after the Ebola outbreak: panel survey evidence from Monrovia, Liberia. BMJ Glob Health 2016;1:e000007. 10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vinck P, Pham PN, Bindu KK, Bedford J, Nilles EJ. Institutional trust and misinformation in the response to the 2018-19 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu, DR Congo: a population-based survey. Lancet Infect Dis 2019;19:529-36. 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30063-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abiola SE, Gonzales R, Blendon RJ, Benson J. Survey in sub-Saharan Africa shows substantial support for government efforts to improve health services. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:1478-87. 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O’Malley AS, Sheppard VB, Schwartz M, Mandelblatt J. The role of trust in use of preventive services among low-income African-American women. Prev Med 2004;38:777-85. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mostashari F, Riley E, Selwyn PA, Altice FL. Acceptance and adherence with antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected women in a correctional facility. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1998;18:341-8. 10.1097/00042560-199808010-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kruk ME, Rockers PC, Varpilah ST, Macauley R. Which doctor?: Determinants of utilization of formal and informal health care in postconflict liberia. Med Care 2011;49:585-91. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820f0dd4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hogan DR, Stevens GA, Hosseinpoor AR, Boerma T. Monitoring universal health coverage within the Sustainable Development Goals: development and baseline data for an index of essential health services. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e152-68. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30472-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beaumont P. “Most complex health crisis in history”: Congo struggles to contain Ebola. Guardian 2019 Jun 25. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/jun/25/most-complex-health-crisis-congo-struggles-ebola-drc

- 18. Ambesh P. Violence against doctors in the Indian subcontinent: a rising bane. Indian Heart J 2016;68:749-50. 10.1016/j.ihj.2016.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shi J, Wang S, Zhou P, et al. The frequency of patient-initiated violence and its psychological impact on physicians in china: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0128394. . 10.1371/journal.pone.0128394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jiao M, Ning N, Li Y, et al. Workplace violence against nurses in Chinese hospitals: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006719-006719. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu D, Wang Y, Lam KF, Hesketh T. Health system reforms, violence against doctors and job satisfaction in the medical profession: a cross-sectional survey in Zhejiang Province, Eastern China. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006431. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dhillon RS, Kelly JD. Community trust and the Ebola endgame. N Engl J Med 2015;373:787-9. 10.1056/NEJMp1508413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chowell G, Nishiura H. Transmission dynamics and control of Ebola virus disease (EVD): a review. BMC Med 2014;12:196. 10.1186/s12916-014-0196-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ozawa S, Sripad P. How do you measure trust in the health system? A systematic review of the literature. Soc Sci Med 2013;91:10-4. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Williamson LD, Bigman CA. A systematic review of medical mistrust measures. Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:1786-94. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mascarenhas OA, Cardozo LJ, Afonso NM, et al. Hypothesized predictors of patient-physician trust and distrust in the elderly: implications for health and disease management. Clin Interv Aging 2006;1:175-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shea JA, Micco E, Dean LT, McMurphy S, Schwartz JS, Armstrong K. Development of a revised health care system distrust scale. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:727-32. 10.1007/s11606-008-0575-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Doescher MP, Saver BG, Franks P, Fiscella K. Racial and ethnic disparities in perceptions of physician style and trust. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:1156-63. 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rose A, Peters N, Shea JA, Armstrong K. Development and testing of the health care system distrust scale. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:57-63. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21146.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. LaVeist TA, Isaac LA, Williams KP. Mistrust of health care organizations is associated with underutilization of health services. Health Serv Res 2009;44:2093-105. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01017.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ozawa S, Walker DG. Comparison of trust in public vs private health care providers in rural Cambodia. Health Policy Plan 2011;26(Suppl 1):i20-9. 10.1093/heapol/czr045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Duckett J, Hunt K, Munro N, Sutton M. Does distrust in providers affect health-care utilization in China? Health Policy Plan 2016;31:1001-9. 10.1093/heapol/czw024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhao D-H, Rao K-Q, Zhang Z-R. Patient trust in physicians: empirical evidence from Shanghai, China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2016;129:814-8. 10.4103/0366-6999.178971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berwick DM, Kelley E, Kruk ME, Nishtar S, Pate MA. Three global health-care quality reports in 2018. Lancet 2018;392:194-5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31430-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Academy of Medicine. Crossing the global quality chasm: improving health care worldwide . 2018. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2018/crossing-global-quality-chasm-improving-health-care-worldwide.aspx [PubMed]

- 36.Bowser D, Hill MPHK. Exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility-based childbirth report of a landscape analysis. 2010. https://www.ghdonline.org/uploads/Respectful_Care_at_Birth_9-20-101_Final1.pdf

- 37. Blair RA, Morse BS, Tsai LL. Public health and public trust: Survey evidence from the Ebola Virus Disease epidemic in Liberia. Soc Sci Med 2017;172:89-97. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Abiola SE, Gonzales R, Blendon RJ, Benson J. Survey in sub-Saharan Africa shows substantial support for government efforts to improve health services. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:1478-87. 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Das J, Hammer J, Leonard K. The quality of medical advice in low-income countries. J Econ Perspect 2008;22:93-114. 10.1257/jep.22.2.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]