Globally, 23% of persons with mental illness who are admitted to mental hospitals for treatment stay there for more than one year.[1] Such patients are in a state of “handicaptivity"[2] and are left with little options other than accepting the security of a hospital, due to lack of better available alternatives. This population has been termed by some experts as “unwanted patients."[3]

THE LIFE OF A LONG-STAY PATIENT

Like most mental hospitals across India, National Institute of Mental health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bengaluru has long-stay patients who are in the hospital ward for many years because they do not have a family or a place to go back to. This is in spite efforts to place them in agencies and homes outside the hospital. In many instances, the hospital has made multiple attempts to trace the families of these patients, albeit unsuccessfully.

Each of them has a story that they narrate about how they got here and how the wards have gradually become their home. For most of these patients, hope does not lie in big things but in the very small gestures, they receive. Most find happiness in fulfilling small needs like having something special to eat or some old ornaments to wear.

Many of them spend their time in activities in the wards and at vocational sections at daycare facility of psychiatric rehabilitation services, to keep themselves engaged. Patients who attend the psychiatric rehabilitation services get incentives for the work they carry out. Some of the patients are very old and are assisted by the nursing staff and the hospital attenders in activities of daily living.

THE IMPETUS FOR AADHAAR ENROLLMENT FOR LONG-STAY PATIENTS

In a study on long-stay, female patients attending the daycare services at NIMHANS, most common rehabilitation need expressed by the patients, the nursing staff, the vocational instructors, and the treating team was more monetary incentives to enable patients to have food of their choice occasionally and to buy items for personal care and hygiene.[4]

Hospital authorities were sensitized about the study findings, and the incentive was increased from Rs 60/month to Rs 700/month in March 2015.[4] The nursing staff in the ward maintains a register of money received, and it is used to procure food or personal care items as per the preference of the patients.

Other options for ensuring remuneration are to facilitate employment opportunities (within or outside the hospital) or pension if the patient fulfills criteria for benchmark disability. Both require proof of identity and address. Enrolment in Aadhaar would solve the issue.

AADHAAR FOR LONG-STAY PATIENTS

Aadhaar, an identity document, is a 12-digit random number issued by the Unique Identity Authority of India (UIDAI) to the residents of India on satisfying the verification process.[5] Any individual, irrespective of age and gender, who is a resident of India, may voluntarily enroll to obtain Aadhaar. During the enrolment process, which is free of cost, minimal demographic and biometric information has to be provided by the person willing to enroll. Aadhaar serves both as proofs of identity and address. The first Aadhaar card of the country was issued on 29th September 2010.[6] Most long-stay patients were admitted to the hospital before the Aadhaar era began. Aadhaar enrolment for a long-stay patient could serve as proofs of identity and address and facilitate other steps such as disability certification, voter card enrollment, and opening a bank account.

DILEMMA IN PROVIDING HOSPITAL ADDRESS FOR AADHAAR

Although it is ideal to get an Aadhaar card in their home address, there are logistic difficulties for a hospital to verify the home address the patient remembers and getting an address proof document for that address. The patient may have left home long back (several decades in some cases), may be from a different state, or may not remember the address. The address may no longer exist, or no family member is alive at the last known address.

In such a situation, it appeared pragmatic to get the hospital address as address proof. It does not mean that the patient will stay at the hospital forever. When the circumstances arise, the address can be changed to the place where the patient can be discharged to.

THE PROCEDURE FOLLOWED FOR AADHAAR ENROLLMENT FOR LONG-STAY PATIENTS

After being appraised about the issues, Institute authorities accorded permission to provide the hospital address as address proof for enrolment in Aadhaar. The process of enrolment of decertified (i.e. not under reception order as per the Mental Health Act, 1987) long-stay patients was initiated toward the end of 2016. UIDAI authorities in Bengaluru were contacted. The Institute authorities issued a letter containing the name, age, sex, latest photo, and hospital address/contact details in the format desired by UIDAI. For patients whose date of birth was not known, first January was given as date and month of birth, and the year was calculated from the age recorded in the case file.

Owing to logistic difficulties in transporting long-stay patients to the Aadhaar enrolment center, UIDAI authorities kindly consented to enroll these patients at the hospital premises itself. On 6th April 2017, biometric verification for Aadhaar enrolment was done in the ward for 21 long-stay patients. Patients were oriented about the procedure and made comfortable prior to and during Aadhaar enrolment. The enrolment number was used to follow-up with UIDAI portal, and e-Aadhaar was downloaded when it was available. The copy was given to the nursing staff in the ward for filing in the case records.

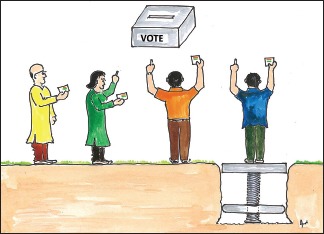

VOTING RIGHTS OF A LONG-STAY PATIENT

According to the World Health Organization Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR) Matrix, political participation is one of the sub-components of empowerment needs of persons with disabilities.[7]

In India, the following are relevant clauses pertaining to voting by a person with mental illness:

Representation of People Act 1951 (Chapter IV, Section 62(2)): It states that “No person shall vote at an election in any constituency if he is subject to any of the disqualifications referred to in section 16 of the Representation of the People Act, 1950 (43 of 1950)”[8]

The Representation of the People Act, 1950 (Section 16 (1b): One reason for disqualification for registration in an electoral roll is if “he is of unsound mind and stands so declared by a competent court.”[9]

A diagnosis of mental illness is neither necessary nor sufficient for a finding of unsound mind.[10] United Nations Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) also states that persons with mental illness cannot be denied right and opportunity to vote.[11] Legally, persons with mental illness can, unless declared to be of unsound mind by a competent court, exercise their constitutional right to vote. This holds true for a long-stay patient as well.

THE PROCEDURE FOLLOWED FOR FACILITATING VOTING FOR LONG-STAY PATIENTS

After obtaining the Institute's permission, the process of getting voter cards was initiated in April 2018 for Karnataka assembly elections scheduled on 12th May 2018. Among patients enrolled in Aadhaar with hospital address, only five were in a position to vote. Some patients did not have the capacity to understand “voting,” and one person had been declared to be of “unsound mind” by the court. Out of the five patients, only three (two females and one male) expressed an interest and were in a position to vote. None of them had voted in the past. The duration of hospital stay was 4, 10, and 19 years, respectively.

The online application was filled for enrolment as a voter and submitted with supporting documents (Aadhaar, which served as both proofs of identity and address). House number was a mandatory column to be filled while applying for voter card. The ward number was given as house number. In spite follow-up, voter cards had not come till 11th May evening. The issue was brought to the attention of Chief Electoral Officer by an official email on 11th May after the working hours. The election officials swiftly responded to the email. Voter ID and polling station details were shared by email.

The patients were sensitized about the voting process. One among them would speak well only to a particular therapist, and that therapist sensitized him. They were accompanied to the polling booth on 12th May 2018. The polling booth officials and the general public were very helpful and permitted the patients to skip the queue and vote. When the voter cards came (after the elections), the three patients were thrilled to see a laminated card with their photo. The voter cards are in safe custody.

All the three patients voted for the second time in Lok Sabha elections in 18th April 2019, for which government officials themselves arranged a car for transporting the patients to the polling booth.[12]

CHALLENGES FACED

As this was a unique initiative done for the first time in a government institute, it took time to clarify the procedure, obtain the necessary permissions, contact the key personnel for Aadhaar and voter cards, gather the documents in the prescribed format, facilitate the paperwork, follow-up on the progress, and coordinate with the stakeholders to take it to the logical conclusion.

During the process, concerns were raised about the ability of the patients to understand the political situation to cast their vote, privacy concerns of using the hospital address, and about “utility” of the entire exercise. While approaching the three patients for voting for the second time, there were doubts if the novelty of voting would have worn-off and if they would be interested in voting again. However, the patients were keen and excited to vote again.

FACILITATORS

The permission of the Institute, enthusiasm of the long-stay patients, encouragement from our colleagues, and the support of the election officials and the general public kept us going. The three votes cast on 12th May 2018 are “a small step,” which can and needs to be replicated across the country. After the NIMHANS initiative, voting was facilitated for more than 150 long-stay patients at the Institute of Mental health, Chennai on 18th April 2019.[13] With such initiatives, hospitals are acknowledging the person in every “patient” and empowering them in sync with the recent rights-based legislations.

THE WAY FORWARD

A lively and dedicated endeavor to rehabilitate this population both inside and outside the hospital needs to be attempted.[14] Clarity and affirmative action are also needed for certifying long-stay patients for disability, facilitating access to disability pension, and credit to their own bank accounts opened by the hospital.

National Human Rights Commission has advised that hospital authorities may find some jobs for the fully recovered patients on nominal remunerations within the hospital, to rehabilitate them.[15]

The Mental Healthcare Act, 2017[16] states that “long term care for patients in mental health establishments shall be used only in exceptional circumstances, for as short a duration as possible, and only as a last resort when appropriate community-based treatment has been tried and shown to have failed” (Clause 18 (5c)). It also affirms that long-stay patients have a right to community living in their family home or in less restrictive community-based establishments, including half-way homes and group homes. Enrolment in Aadhaar and getting voter card are steps toward facilitating social inclusiveness and community reintegration. Further, it is important to develop services such as supported housing, supported education, and supported employment to cater to their complex needs.[4]

CONCLUSION

Persons with mental illness need to be able to exercise their rights as citizens of the country, including their right to vote. It is the duty and responsibility of mental health professionals to facilitate appropriate opportunities for the “voiceless” population.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

NIMHANS Institute and Hospital administration and Department of Psychiatry for support to the initiative.

Ms. Amrita Roy (PhD scholar in Mental Health Rehabilitation), Dr. Rashmi (Fellow in Psychiatric Rehabilitation), Ms. Lydia (M. Phil Psychiatric Social Work Trainee) and Dr. Manjushree (Junior Resident in Psychiatry) for facilitating voting of long-stay patients in 2018 and 2019 elections.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. Mental Health Atlas 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deegan P. Silence: What We Don't Talk About in Rehabilitation [Internet] 2005. [Last cited on 2019 Feb 17]. Available from: https://www.patdeegan.com/pat.deegan/lectures/silence .

- 3.Bhaskaran K. The unwanted patient. Indian J Psychiatry. 1970;12:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waghmare A, Sherine L, Sivakumar T, Kumar CN, Thirthalli J. Rehabilitation needs of chronic female inpatients attending day-care in a tertiary care psychiatric hospital. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38:36. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.175104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unique Identity Authority of India [Internet] Unique Identification Authority of India | Government of India. [Last cited on 2019 May 24]. Available from: https://uidai.gov.in/

- 6.Byatnal A. Tembhli becomes first Aadhar village in India. The Hindu [Internet] 2010. Sep 29, [Last cited on 2019 May 24]. Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/Tembhli-becomes-first-Aadhar-village-in-India/article13673162.ece .

- 7.WHO/UNESCO/ILO/IDDC. Community Based Rehabilitation: CBR Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Government of India. The Representation of the people act, 1951. [Internet] 1951. [Last cited on 2019 May 24]. Available from: http://www.legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/04_representation%20of%20the%20people%20act%2C%201951.pdf .

- 9.Government of India. The Representation of the People Act, 1950 [Internet] 1950. [Last cited on 2019 May 24]. Available from: http://legislative.gov.in/sites/default/files/A1950-43.pdf .

- 10.Pathare S. Widely cited, but still undefined. The Hindu [Internet] 2017. Apr 23, [Last cited on 2019 May 24]. Available from: https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/health/widely-cited-but-still-undefined/article18191442.ece .

- 11.United Nations. United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities [Internet] United Nations. 2006. [Last cited on 2019 May 24]. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html .

- 12.Rao S. Three Nimhans in-patients exercised their franchise-Times of India. The Times of India [Internet]. Bengaluru. 2019. Apr 20, [Last cited on 2019 May 24]. Available from: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/elections/lok-sabha-elections-2019/karnataka/news/three-nimhans-in-patients-exercised-their-franchise/articleshow/68962270.cms .

- 13.Rahman S. Chennai's mental health Institute scripts history, its 159 inmates vote for first time. The Indian Express [Internet]. Chennai. 2019. Apr 18, [Last cited on 2019 May 24]. Available from: https://indianexpress.com/elections/chennais-mental-health-institute-scripts-history-its-159-inmates-vote-for-first-time-5682061/

- 14.Somasundaram O, Jayachandran P, Kumar R. Long stay patients in a state mental hospital. Indian J Psychiatry. 1982;24:346–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Human Rights Commission. Care and Treatment in Mental Health Institutions– Some Glimpses in the Recent Period. National Human Rights Commission. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mental Healthcare Act 2017 [Internet] Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India. 2017. [Last cited on 2019 Mar 07]. Available from: https://indiacode.nic.in/handle/123456789/2249?view_type=search&sam_handle=123456789/1362 .