Abstract

Context:

Adolescents constitute nearly 21% of the population in India. They are more likely to be constrained than adults from access to and timely use of appropriate care. Adolescence in girls is a turbulent period. The changes that take place during this period need to be made stress free. These are mostly physiological, for which simple family remedies can be found out.

Objectives:

1. Assessing the health needs of adolescent girls living in an urban slum. 2. Identifying the barriers in accomplishing the health needs.

Methodology:

This was a community-based cross-sectional study with mixed method approach. A focus group discussion was held with 13 adolescent girls. FGD results were used to prepare a questionnaire to interview 80 adolescent girls.

Results:

The FGD revealed adolescent girls needed more information on menstrual hygiene, reproductive health, and its associated illness. Totally, 45% of the adolescent girls belonged to the age group 17–19 years. About 90% had inadequate knowledge on reproductive health. They preferred group sessions over one-to-one session on these topics and their mother as the source of information.

Conclusion:

The reproductive and sexual healthcare education that is currently being imparted to the girls need to be devised in such a way that it empowers them. A family member—the mother needs to be trained so that she can make this age transition smooth and stress free. The correct scientific knowledge will help in ensuring sustainable development.

Keywords: Adolescent girls, focused group discussion, health needs, menstrual hygiene, mixed method, urban slum

Introduction

The adolescents and the youth are a critical segment of any nation. The future of the nation depends on them. In India, 243 million adolescents constitute 21% of its population.[1] The 50% adolescent population is girl population which is approximately 10% of the total population.[2] Change is the hallmark of adolescence, which is characterized by rapid physical growth and significant physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual changes. It is a period of transition and influenced by major decisions.[3]

Adolescence in girls is a decisive age for all girls; the decisions taken during this period shape her life as well as that of her family. It is a turbulent period; it includes many stressful events one of them being menarche. The mere onset of puberty heightens the vulnerability—to leaving school, child marriage, early pregnancy, HIV, sexual exploitation, coercion, and violence.[4]

Adolescent girls unlike women are less likely to access sexual and reproductive health care services. They consider themselves grown up and mature enough to have sex, yet they have inadequate knowledge about the consequences of unprotected sex. They do not reveal their reproductive health problems and tend not to use the health care services they actually need. This may be due to inadequate information, limited access to financial resources or negative attitudes of health care workers.[5]

The problems of this age group are known to every health personnel, yet there has been no correct solution identified to tackle them. The adolescent girls staying in slums from sub urban area severely lack reliable resources to build knowledge regarding their health-related queries. It is very important to understand and empower the adolescents as it will not only help in reduction of morbidity and mortality but also indirectly in progress of the nation in many ways like—boosting economy of the nation keeping the population under check. The investment in the health, education, and employment of young people, particularly adolescent girls are among the most cost effective development expenditures in terms of social returns.[4] An empowered and physically fit adolescent girl will not only improve all her dimensions of health but also the family she was born into and the one she will be married into. This study has been designed to identify the health needs of adolescent girls with special reference to reproductive health needs.

Methodology

Study design

A community-based cross-sectional study using mixed method approach.

Study setting

The study was conducted in urban field practice area of a medical college in Mumbai, which is a slum area. NGO working for betterment of adolescents living in the slum area, helped us coordinate with the study participants. The duration of the study was 1 year.

Sample size

According to NFHS 4 data for India, the prevalence of women in the age group 15–19 years who were already mothers or pregnant at the time of survey was 5.0.[6] The sample size was computed to be 76, this was rounded of to 80.

Sampling technique

Simple random sampling. From the register containing the details of all adolescent living in the urban slum area, 80 adolescent girls were selected using random number table.

Study procedure

The purpose of the study was explained using an informed consent document. Assent was obtained from the parents of girls less than 18 years of age.

Ethics approval

Ethical clearance was obtained from Institutional Ethics Committee of Seth GSMC and KEM Hospital, Mumbai.

Data collection

Was done in two phases:

A. Focus Group Discussion and B. Interview

A. Focus Group Discussion (FGD) was conducted in the Balwadi, with 13 adolescent girls, the moderator introduced herself and the recorder, explained the purpose of conducting the session. Participants for FGD were chosen by convenience sampling. All participants and the investigators formed a circle and sat on the floor to avoid any barrier of communication. The standard operative procedure for conducting a focus group discussion was followed.[7] It was conducted in the presence of a female NGO coordinator to ease the atmosphere. The topics chosen for discussion were the common adolescent health problems like nutrition, exercise, mental health and reproductive and menstrual health. These were chosen to understand what the adolescent girls perceive as their health need. Audio recording of the discussion was done along with taking notes of all information including the change of expression and body language of the participants. A transcript of the obtained data was prepared the very same day after translating the recording to English as the FGD was conducted in the local language.

B. Interview -Based on the results of the FGD we prioritized the interview on reproductive and menstrual health. A semi structured questionnaire was prepared for the same, which was then validated. Eighty adolescent girls were interviewed.

Data analysis

Data obtained using interview schedule was entered in Microsoft Excel and statistical analysis was done using SPSS. The knowledge and practices associated with menstrual hygiene, contraception and safe sexual was assessed, 2-3 questions were asked under each category. Data was measured on Likert scale each was scored out of 3, a participant who scored between 1 and 3 was graded as poor, 4 and 6 as good, and 7 and 9 as excellent. For the qualitative analysis, the themes generated were knowledge, frequency of discussion about topic in educational institution/home and inquisitiveness, we also observed for confidence the participants had while discussing the theme, the level of comfort/ease in discussion and group dynamics. To ensure comprehensive reporting of findings COREQ and STROBE checklists are used.[8,9]

Results

Qualitative method

The focus group had adequate representation from all adolescent age groups; it had girls attending school and college. Topics were slowly introduced into group. Some of the young adolescents were very enthusiastic and were eager to voice their opinion. The participants had adequate knowledge about nutrition and exercise. They liked discussing these topics and discussed comfortably with the researcher because same topics were also discussed at length in school by their teachers. All girls were familiar and comfortable with mental health issues but, showed no much interest in knowing more. On the topic of Reproductive and Sexual health not all participated in the discussion, the moment this topic was brought up, the very interactive group suddenly fell silent and each started looking at their peers prompting the other to talk, there was hesitation. The girls in the 12–14 years age group expressed that they have concerns about menstruation as many have just attained menarche. Girls in the age group of 15–19 years mentioned that information about menstrual hygiene was given in schools/colleges but they could not clarify doubts and added there is no place where it can be privately discussed with teachers. They also mentioned that the session was never discussed again in the class. A group of college going adolescents in the FGD also asked the investigators if they could come and talk to them about the issues of menstrual and reproductive health. Hence from the above discussion it was concluded that the need of adolescent girls is to know more about their reproductive and sexual health.

A 16-year-old girl said, “I really want to talk to you about this but not in front of the young girls, I’m not comfortable here.”

“I want to know what periods mean, my sisters talk about it secretly, but they don’t tell me.” – 12-year-old girl.

Quantitative method

The socio demographic variables of the adolescent girls were studied, and it was seen [Table 1] that 45% of girls in the study group belonged to the age group 17–19 years. The information of monthly income of the families of the adolescent girls was provided to us either by the parent or by the NGO co-ordinator. Majority (48.75%) of the adolescents, belonged to Class I socio economic status as per B G Prasad's classification (2016). In the study group most girls (67.50%) were either pursuing or had completed their high school education. The most prevalent (78.75%) type of family structure in our study was nuclear. It was observed that 3 girls (>18 years of age) were married.

Table 1.

Socio demographic profile

| VARIABLE | (n) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) (n=80) | ||

| 10-13 | 23 | 28.75 |

| 14-16 | 21 | 26.25 |

| 17-19 | 36 | 45.00 |

| Education (n=80) | ||

| Primary | 13 | 16.25 |

| Secondary | 54 | 67.50 |

| Higher secondary | 13 | 16.25 |

| Reason for discontinuing education (n=35) | 35 | 43.75 |

| Family problem | 9 | 25.71 |

| Financial problem | 18 | 51.43 |

| Not interested | 6 | 17.14 |

| Health problem | 2 | 5.71 |

| Parents educational status (n=80) | ||

| Mother | ||

| Illiterate | 41 | 51.25 |

| School (upto 10) | 34 | 42.50 |

| College | 5 | 6.25 |

| Father | ||

| Illiterate | 35 | 43.75 |

| School (upto 10) | 39 | 48.75 |

| College | 6 | 7.50 |

| Occupation (n=80) | 14 | 17.50 |

| Socio-economic status (B G Prasad’s classification 2016[10]) (n=80) | ||

| I | 39 | 48.75 |

| II | 5 | 6.25 |

| III | 18 | 22.5 |

| IV | 16 | 20.0 |

| V | 2 | 2.5 |

| Religion (n=80) | ||

| Hindu | 32 | 40.0 |

| Muslim | 39 | 48.75 |

| Buddha | 9 | 11.25 |

| Type of family (n=80) | ||

| Nuclear | 63 | 78.75 |

| Joint | 16 | 20.00 |

| Three generation | 1 | 1.25 |

| Total number of family members (n=80) | ||

| <6 | 49 | 61.25 |

| >6 | 31 | 38.75 |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried | 77 | 96.25 |

| Married | 3 | 3.75 |

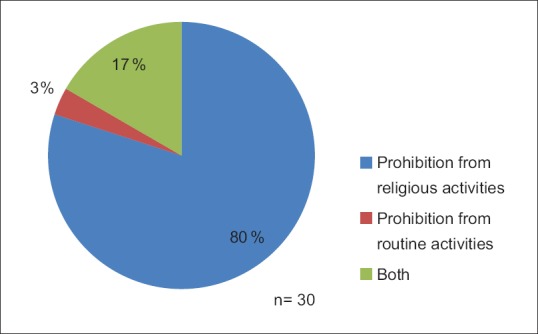

Majority of the adolescents had attained menarche by 14 years of age (88.75%); menstrual cycles were regular in 62% of the girls. Certain cultural practices associated with menstruation, were prevalent in 37.5% of the families. It included prohibition from routine activities or prohibition from religious activities and in some cases both. [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Distribution of cultural practice associated with menstruation

Majority of the girls had very little knowledge about their reproductive health. Only one married adolescent girl in the 17- to 19-year age group was graded excellent. Totally, 90% of the girls had poor knowledge about these topics. [Table 2]

Table 2.

Assessment of knowledge of menstrual hygiene, contraception and safe sexual practice

| Age (yrs) | Poor (1-3) | Good (4-6) | Excellent (7-9) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17-19 | 28 | 7 | 1 | 36 (45%) |

| 14-16 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 21 (26.25%) |

| 12-13 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 23 (28.75%) |

| Total | 72 (90%) | 7 (8.75%) | 1 (1.25%) | 80 (100%) |

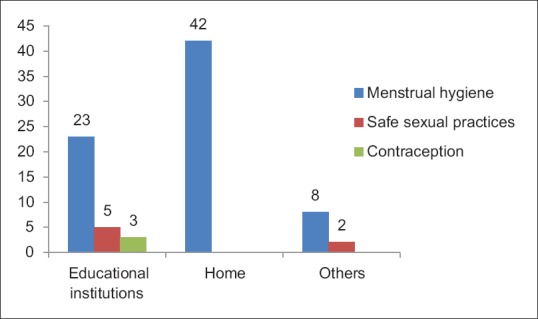

The awareness of reproductive health and related health issues was present in 91% of the girls. Among the girls who were aware of reproductive health 57.5% got this information at home from mothers and elders in the family. A very small proportion of girls got the information from magazines and internet. The information provided in these sessions which were conducted in school mostly focused on menstrual hygiene only. [Figure 2]

Figure 2.

Distribution of the source of information. (Multiple responses considered)

Most of the adolescent girls (84%) demanded that information be provided to them not only on menstrual hygiene but also on reproductive and sexual health. The preferred provider of information was mother in 41% of the girls; followed by 37% responding both mother and teacher. Majority of the girls, that is 91%, did not want to talk to doctor about issues relating to menstrual and reproductive health, 63% stated the reason as—not comfortable and the rest 37% stated it was not required to discuss these issues with a doctor as the visit to a doctor is mostly for illness. The lack of privacy in school was stated as a reason by 65% of the girls for not discussing concerns about their reproductive and sexual health with teachers.

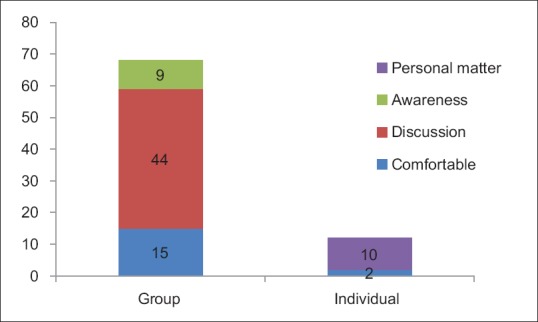

Group session over one to one session was preferred by 85% of the girls on topics related to reproductive and sexual health, as they would be able to discuss the same among themselves after the session (64.7%) while 22% were comfortable in group session [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Distribution of session preference and reason

Discussion

The rationale for conducting the study was to assess the health needs and identify the barriers in obtaining scientific information about reproductive and sexual health needs. Thirteen girls participated in focus group discussion and 80 girls were interviewed. Various programs are currently focusing on reproductive health issues of adolescent girls, yet the girls expressed their health need to be reproductive and sexual health. A quantitative study using an interview schedule followed the FGD, in which most girls want a group health education session on the topic.

Most girls in the study group attained menarche by 14 years of age which is consistent with the findings of study conducted by Pagadpally Srinivas.[11] Despite the financial hardships most of the girls (67.5%) were completing/had completed their formal school education. These findings are similar to a study conducted by Awasthi R, et al.[12] The main reason for discontinuing education as stated by girls in our study group was financial problems (51.43%). These findings are in coherence with a study conducted by B Maithly and Vartika Saxena, in which majority of the participants (34% (40% male and 30% female)) gave financial reason for dropping out of school.[13] In our study only 3 girls (3.75%) above the age of 18 years were married this was a best case scenario to witness considering the social, cultural and economic problems of people living in urban slums. These findings are different from study conducted by T Rajaretnam and Jyoti S Hallad wherein 12% girls from the urban areas in the age of 18–19 years were married.[14]

The adolescent girls did have knowledge about menstrual hygiene as an NGO working for welfare of youth conducts these sessions under the ARSH programme at regular intervals. The awareness about safe sexual practices was absent in many. The family members, most often the mother, when the girl attains menarche make the girls aware about the menstrual hygiene but do not divulge information about safe sex or contraception, which needs to be imparted to these adolescent girls. A study conducted by Bekkalale Chikkalingaiah Sowmya et al. reports mother as the first informant.[15] All the elders, family members and teachers who play a major role in the lives of adolescent girls, are imparting them with information of menstrual hygiene but, the information is insufficient, it is not empowering them. By giving complete information on reproductive and sexual health this empowerment can be achieved. Focus group discussions can be planned with the mothers of adolescent girls as well as other information providers to understand the difficulties or barriers being faced by them in imparting information. Further, classes can be conducted for mothers on how and what information needs to be communicated to the adolescent girls. The role of parents and other family members in health education of adolescents has been highlighted in various reports.[16]

Schools have been recognized as preferred place for health education and promotion because of the important interactions between health, academic success, and education, and also because it is where a vast majority of an age group can be reached the same approach is being reported by our study participants wherein the health education sessions on sexual and reproductive health almost always conducted in the schools and colleges. As per the results of qualitative and quantitative sessions should also be planned in the community where the adolescent girls live. The adolescent girls seem to be in the habit of discussing most of the issues with their peers. Sessions in the locality will ensure discussion occurs only after the correct information is available. Session in educational institution and community will further reinforce the information as well as create additional opportunity for clarification of any doubts. It might also make the topics more acceptable for people to talk. As expressed by the participants that they prefer the mother to provide information, sensitization/training session should be organized for the mothers on how to make their children aware of the menstrual hygiene, safe sex practices, and contraception.

It was understood that it is not only the need for information but also to be able to clarify doubts regarding these matters is the requirement of these adolescents. Education of mothers on these topics so that they can empower their adolescent girls with the right scientific knowledge will definitely help.

Conclusion

In this study group most adolescents belonged to the age group of 17–19 years and most had completed their schooling. Almost all adolescents had at least some knowledge about menstrual hygiene, but knowledge on sexual health was very poor. More than 80% of the girls felt having the correct knowledge about reproductive and sexual health is important to stay healthy. Adolescents although healthy, their health problems and needs are different from that of young children and adults. Orientation/training programs on what education needs to given to the girls regarding reproductive and sexual health can be planned for mothers of adolescent girls so that they will be in a position to empower them. Empowering them with scientific knowledge and improving their health status are essential in ensuring sustainable development. The understanding of adolescent health will also aid in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals 2030[17] (especially goal 3, 4, and 5) directly or indirectly.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient (s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

All staff of the urban health training centre, Malvani for their cooperation and the NGO working in the urban area for betterment of youth.

References

- 1.Sivagurunathan C, Umadevi R, Rama R, Gopalakrishnan S. Adolescent health: Present status and its related programmes in India. Are we in the right direction? J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:LE01–6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/11199.5649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNFPA India | Action for Adolescent Girls initiative in one block of Udaipur. [Last accessed in 2019 Apr 20]. Available from: https://india.unfpa.org/en/submission/action-adolescent-girls-initiative-one-block-udaipur .

- 3.World Health Organization. Adolescent Health and Development. World Health Organization, South-East Asia Regional Office. New Delhi: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNFPA. From childhood to womanhood: Meeting the sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescent girls. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atuyambe LM, Kibira SPS, Bukenya J, Muhumuza C, Apolot RR, Mulogo E. Understanding sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents: Evidence from a formative evaluation in Wakiso district, Uganda. Reprod Health. 2015;12:35. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0026-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. NFHS 4-India-Key Indicators. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conducting Focus Group Discussions. [Last accessed on 2019 Apr 21]. Available from: http://www.nhm.ac.uk/content/dam/nhmwww/our-science/our-work/sustainability/deworm3/2_DeWorm3_SOP_805_Conducting focus group discussions_2017_08_24.pdf .

- 8.COREQ (Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research) Checklist. [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 01]. Available from: http://cdn.elsevier.com/promis_misc/ISSM_COREQ_Checklist.pdf .

- 9.STROBE (Strengthening The Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology) Checklist. [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 01]. Available from: http://www.annals.org/, and Epidemiology at http://www.epidem.com/9 .

- 10.Vasudevan J, Mishra A, Singh Z. An update on B.G. Prasad's socioeconomic scale: May 2016. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016;4:4183–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srinivas P. Perception, knowledge and practices regarding menstruation among School going girls in Karaikal. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2016;15:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Awasthi R, Srivastava A, Dixit A, Sharma M. Nutritional status of adolescent girls in urban slums of Moradabad: A cross sectional study. Int J Community Med Public Heal. 2015;3:276–80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maithly B, Saxena V. Adolescent's educational status and reasons for dropout from the school. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:127–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.40885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajaretnam T, Hallad JS. Nutritional status of adolescents in Northern Karnataka, India. J Fam Welf. 2012;58:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manjunatha S, Kumar J. Menstrual hygiene practices among adolescent girls: A cross sectional study. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2014;3:28. [Google Scholar]

- 16.INSERM Collective Expertise Centre. INSERM Collective Expert Reports [Internet]. Paris: Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale; 2000-. Health education for young people: Approaches and methods. 2001. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7118/ [PubMed]

- 17.United Nations. About the Sustainable Development Goals-United Nations Sustainable Development n.d. [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 09]. Available from: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/