Abstract

Background:

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) is now globally accepted as an Indian disease. It has one of the highest rates of malignant transformation among potentially malignant oral lesions and conditions, therefore, a cause of concern for oral healthcare professionals. The present study aims to evaluate the prevalence of OSMF among betel nut chewers in different age groups in patients visiting Dental College and Hospital Kanpur city, India.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 860 patients of OSMF visiting the dental outpatient clinic of the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology Rama Dental College Hospital and research center, Kanpur over a period of 24 months (1 January 2016 to 31 December 2018) were selected for the study. A detailed case history and clinical examination was carried out under visible light. The diagnosis of OSMF was based on difficulty in opening the mouth and associated blanched oral mucosa, with palpable fibrous bands. Other diagnostic features included burning sensation, salivation, tongue protrusion, habits, and associated malignant changes. Study was done on the basis of age group, habit duration, frequency of habit, and type of habit. Simple correlation analysis was performed.

Results:

Of the 860 cases of OSF studied, 390 (46.42%) cases were stage II, 290 (34.52%) were stage III, 90 (10.73%) stage I, and 70 (8.33%) stage IV. Based upon age group, group III (30--40 years) showed more prevalence than the others. Areca nut (gutkha) was a significant etiological factor (55.8%) as compared with other etiological factors.

Conclusion:

The high prevalence of OSMF requires significant awareness and management of these lesions among general population. Primary healthcare professionals and dentists should be knowledgeable and familiar with the etiopathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of these lesions.

Keywords: Areca nut, clinical staging, oral submucous fibrosis, prevalence

Introduction

In ancient medicine, Shushrutha described a condition, “vidari” under mouth and throat diseases. He noted progressive narrowing of mouth, depigmentation of oral mucosa, and pain on taking food. These features precisely fit in with the symptomatology of oral submucous fibrosis.[1] Schwartz (1952) for the first time reported a case of “atrophica idiopathica tropica mucosae oris” occurring in Indians in East Africa. Lal and Joshi (1953) first described this condition in India. Joshi coined the term “oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF).”[2] Pindborg and Sirsat (1966) described histologically, the four consecutive stages of the OSMF.[3] Seedat and Van Wyk (1988) have reported about irreversible nature of the disease, that is, once OSMF induced by the habit of chewing betel nut, the reversal of the disease after cessation of the habit could not occur.[4]

The magnitude of the situation can be gauged by facts stated in a 2004 review that India ranks the highest among all the registries in the world for incidence of oral cancer with 75,000--80,000 cases reported each year. For many years, this condition had been confined to countries like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, etc., but now due to higher rates of immigration this condition is being reported from Western countries as well.[5,6,7]

This epidemic in part is due to the sudden spurt in the number of industries involved in the convenient and inexpensive packaging and vigorous advertising of products like gutkha and pan masala which was commercially started in 1980 in India. Major steps in curbing this serious health issue by the Government are missing mainly due to the fear of affecting the livelihood of farmers and others involved in this industry. Karnataka, a state of India grows about 65% of the total areca nut produced in the country, yet a ban was just recently imposed on gutkha after several other states banned the product under the Food safety and standards act. Farmers need to be educated regarding the ill effects and encouraged to grow other crops which can bring them profits.[5,8,9,10,11]

The World Health Organization predicts that tobacco deaths in India may exceed 1.5 million annually by 2020. Oral cancer progress through the transformation of tobacco exposed normal oral mucosa to potentially malignant lesions which ultimately changes to carcinoma. OSMF is now globally accepted as an Indian disease. It has one of the highest rates of malignant transformation among potentially malignant oral lesions.[12,13]

Primary healthcare physician can play a very vital role in early diagnosis of OSMF considering its progressive nature. It is a restrictive condition of oral cavity with multifactorial etiology with areca nut chewing most common one. Prevalence of this deleterious habit in India is on rise so this disease which once used to be rare has become very common, hence the awareness of the clinical features, diagnosis, and management is the main stay to curb this menace. Hence, role of primary healthcare physician, being the first point of contact for general population, becomes paramount. The present study was conducted to evaluate the prevalence of OSMF among betel nut chewers in different age groups among north Indian population.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Outpatient Department of the Oral Medicine and Radiology for 24 months. Approval from the Ethical Committee of the Institute was obtained and informed consent was taken from the participants. OSMF patients were divided according to gender. A total of 860 OSMF patients were screened out. All oral examinations were done by specialist examiners who were familiar with oral mucosal lesions in the local population. A sterile mouth mirror was used for retraction of tissues, and examination of oral cavity was done using examination gloves. The selected patients were divided into four groups according to their clinical stage:

Stage I: Interincisal mouth opening up to or greater than 35 mm, stomatitis, and blanching of oral mucosa.

Stage II: Interincisal mouth opening between 25 and 35 mm, presence of palpable fibrous band in buccal mucosa and/or oroparynx, with/without stomatitis.

Stage III: Interincisal mouth opening between 15 and 25 mm; presence of palpable fibrous bands in buccal mucosa and/or or pharynx, and in any other parts of the oral cavity.

Stage IV: Interincisal mouth opening less than 15 mm.

A. Any other stage along with other potentially malignant disorders, for example, oral leukoplakia, oral erythroplakia, etc.

B. Any other stage along with oral carcinoma.

The OSMF patients were divided in four categories on the basis of age groups:

Group I: 10–20 years

Group II: 20–30 years

Group III: 30–40 years

Group IV: 40–50 years.

Prevalence of OSMF was also recorded on the basis of habit duration and divided in three groups:

Group A: 2–5 years

Group B: 5–10 years

Group C: More than 10 years.

This study was conducted on the basis of the type of habit and divided into three groups:

Group 1: Guthka, pan masala.

Group 2: Betal quid.

Group 3: Tobacco, smoking.

Patients suffering from any systemic diseases and children below the age of 10 years were excluded from this study. Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). Descriptive statistics included calculation of means and standard deviation. Data distribution was assessed for normality using Shapiro--Wilk test. Chi-square test was used for comparing the categorical data. All values were considered statistically significant for a value of P < 0.05.

Results

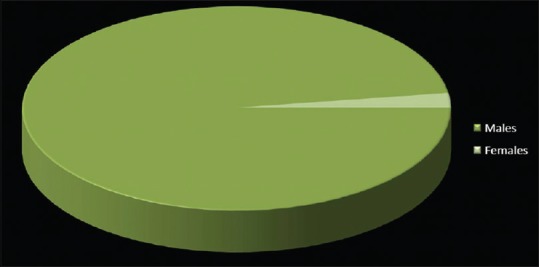

There were 31,570 subjects in total being screened up, 860 subjects were found to be suffering from OSMF. Figure 1 shows out of 860 subjects, 840 were males (97.33%) and 20 were females (2.33%). According to mouth opening, OSMF was divided in four stages. Table 1 shows more prevalence in stage II 402 (46.74%), followed by stage III 298 (34.66%), stage I 90 (10.47%), and stage IV 70 (8.14%). Table 2 shows the prevalence on the basis of age groups, more prevalence of OSMF was found in group III (34.42%), followed by group II (30.70%), group IV (27.91%), group I (4.65%), and group V (2.33%). In Group I, more prevalence was found in stage II (75%) OSMF than stage I (25%). In Group II, approximately equal prevalence was found in stage II (34.09%) and stage III (35.61%). Less prevalence was recorded in stage I (30.30%) under group II. In Group III, more prevalence was found in stage II (54.73%) OSMF than stage III (45.27%) OSMF. No prevalence was found in stage I and stage IV. In Group IV, more prevalence was found in stage II (50%) OSMF followed by than stage III (29.17%) and stage IV (20.83%) OSMF. Finally, in group V, all 20 patients were found in stage IV. (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Gender wise distribution of OSMF

Table 1.

Prevalence of OSMF on the basis of clinical staging

| OSMF stage | Number | Percentage | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I | 90 | 10.47% | 215 | 161.77 |

| Stage II | 402 | 46.74% | ||

| Stage III | 298 | 34.66% | ||

| Stage IV | 70 | 8.14% | ||

| Total | 860 |

Table 2.

Prevalence of OSMF on the basis of age group

| Age group (in years) | Total | Percentage | Stage | Number | Percentage | Mean±SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-20 years (Group I) | 40 | 4.65% | Stage I | 10 | 25% | 10±0.142 |

| Stage II | 30 | 75% | ||||

| Stage III | 00 | - | ||||

| Stage IV | 00 | - | ||||

| 20-30 years (Group II) | 264 | 30.70% | Stage I | 80 | 30.30% | 66±7.79 |

| Stage II | 90 | 34.09% | ||||

| Stage III | 94 | 35.61% | ||||

| Stage IV | 00 | - | ||||

| 30-40 years (Group III) | 296 | 34.42% | Stage I | 00 | 74±11.25 | |

| Stage II | 162 | 54.73% | ||||

| Stage III | 134 | 45.27% | ||||

| Stage IV | 00 | - | ||||

| 40-50 years (Group IV) | 240 | 27.91% | Stage I | 00 | - | 60±5.23 |

| Stage II | 120 | 50% | ||||

| Stage III | 70 | 29.17% | ||||

| Stage IV | 50 | 20.83% | ||||

| 50-60 years (Group V) | 20 | 2.32% | Stage I | 00 | - | 5±0.11 |

| Stage II | 00 | - | ||||

| Stage III | 00 | - | ||||

| Stage IV | 20 | 100% | ||||

| P<0.05 | 860 |

Table 3 shows the prevalence of OSMF on the basis of duration of habit. Group A consisted of people with a habit duration of 2–5 years. Group B consisted of people with a habit duration of 5–10 years, and Group C consisted of people with habit duration of more than 10 years. High prevalence was found in Group C (48.84%) in comparison to Group B (47.67%) and Group A (3.49%). This prevalence was statically significant (P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Prevalence of OSMF on the basis of duration of habits

| Duration of habit | Total | Percentage | Stage | Number | Percentage | Mean±SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-5 years (Group A) | 30 | 3.49% | Stage I | 30 | 100% | 7.5±0.12 |

| Stage II | 00 | - | ||||

| Stage III | 00 | - | ||||

| Stage IV | 00 | - | ||||

| 5-10 years (Group B) | 410 | 47.67% | Stage I | 60 | 14.63% | 102.5±13.56 |

| Stage II | 156 | 38.05% | ||||

| Stage III | 174 | 42.44% | ||||

| Stage IV | 20 | 4.88% | ||||

| More than 10 years (Group C) | 420 | 48.84% | Stage I | 0 | - | 105±15.02 |

| Stage II | 246 | 58.57% | ||||

| Stage III | 124 | 29.52% | ||||

| Stage IV | 50 | 11.90% | ||||

| P<0.05 | 860 |

Table 4 shows the frequency of the habit (per day), it was divided in three groups. Group A had a habit frequency of 2–5 times/day; Group B had a habit frequency of 5–10 times/day, and Group C had a habit frequency of more than 10 times/day. Prevalence was more in Group C (45.81%) in comparison to Group B (41.86%) and Group A (12.33%). The prevalence was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Table 4.

Prevalence of OSMF on the basis of frequency of habit per day

| Frequency habit/day | Total | Percentage | Stage | Number | Percentage | Mean±SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-5 times/day (Group A) | 106 | 12.33% | Stage I | 60 | 56.60% | 26.5±3.82 |

| Stage II | 46 | 43.40% | ||||

| Stage III | 00 | - | ||||

| Stage IV | 00 | - | ||||

| 5-10 times/day (Group B) | 360 | 41.86% | Stage I | 30 | 8.33% | 90±20.04 |

| Stage II | 210 | 58.33% | ||||

| Stage III | 105 | 29.17% | ||||

| Stage IV | 15 | 4.17% | ||||

| More than 10 times/day (Group C) | 394 | 45.81% | Stage I | 0 | - | 98.5±21.11 |

| Stage II | 146 | 37.05% | ||||

| Stage III | 193 | 48.98% | ||||

| Stage IV | 55 | 13.96% | ||||

| P<0.05 | 860 |

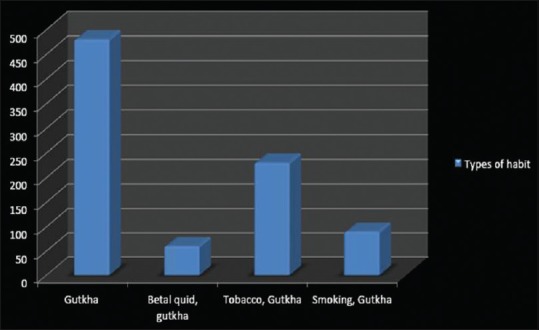

Figure 2 shows prevalence of OSMF on the basis of type of habits. Out of 860 habituated subjects, 480 (55.81%) were in the habit of taking gutkha, 60 (6.98%) were in the habit of taking betal quid and gutkha, 230 (26.74%) were in the habit of taking tobacco and gutkha, 90 (10.46%) were in the habit of smoking and gutkha.

Figure 2.

Types of habit

Discussion

Yang assessed the prevalence, gender distribution, age, income, and urbanization status of OSF patients in Taiwan. Patients were diagnosed with OSMF during the period between January 1, 1996 and December 31, 2013. It showed that the prevalence of OSMF increased significantly from 8.3 (per 10 (5)) in 1996 to 16.2 (per 10 (5)) in 2013 (P < 0.0001). Men had a significantly higher OSMF prevalence than women.[14] Sinor et al. in India found male predominance in OSMF cases.[15] In present study, male predominance can be due to easy accessibility for males to use areca nut and its products more frequently than females. Male patients were more in comparison to females, with a prevalence of OSMF 97.67% compared with 2.33% in females.

Mehrotra conducted a study to evaluate the prevalence rates of oral mucosal lesions in this hospital from 1990 to 2001 in Allahabad, North India. Data was collected year wise with reference to age, sex, site involved, and histopathological findings. It showed that potentially malignant and malignant oral lesions were widespread in the patients visiting the hospital in this region.[16] Similarly, in a population-based case control study in rural and urban Lucknow, it was found that patients who use pan masala were at higher risk of developing OSMF.[17]

The findings of Babu et al., among OSF patients in Hyderabad, showed that people were more addicted to gutkha than any other related areca nut and tobacco products such as pan, pan masala, and raw areca nut. They found a strong association between gutkha chewing and OSMF and pointed that gutkha consumption led to OSMF.[18] Nigam et al. determined the prevalence and severity of OSMF among habitual gutkha, areca nut, and pan chewers of Moradabad, India. The prevalence of OSF was 6.3% and gutkha chewing was the most common abusive habit among OSF patients in the study.[19] Similarly, in the present study, habitual gutkha chewing was more prevalent than gutkha with tobacco.

In this study, the 860 patients were in the age range of 15–60 years, with a peak incidence in 30--40 years (34.88%), followed by 20–30 years (30.23%). Hence, it can be concluded that the occurrence of OSMF is seen most commonly in age group 30--40 years followed by 20–30 years. The youngest patient was 16-year-old, and the eldest was 60-year-old. The observation of present study was similar to study conducted by Nigam, who reported the maximum number of OSMF cases were in the age group of 36--40 years.[19] This could be because of increased social encounters and economic liberty they get at this age in a rapidly developing nation like India. Therefore, during this age, they indulge in various chewing habits such as betel nut, guthka, pan masala, smoking, alcohol, etc., either to relieve stress, as a fashion or due to peer pressure.

Shah found the relationship between OSMF to various chewing and smoking habits. It was found that chewing of areca nut/quid or pan masala (a commercial preparation of areca nuts, lime, catechu and undisclosed coloring, flavoring, and sweetening agents) was directly related to OSMF and frequency of chewing rather than the total duration of the habit was directly correlated to OSMF.[20] Ali et al. evaluated the effect of frequency, duration, and type of areca nut products on the incidence and severity of OSMF. It showed that the duration and frequency of its use and type of areca nut product has effect on the incidence and severity of OSMF. Gutkha and pan masala have more deleterious and faster effects on oral mucosa. The gutkha-chewing habit along with the other habits does not have any significant effect on the rate of occurrence and incidence and severity of the OSMF.[21] Present study showed significant effect of duration and frequency of use of areca nut products on the incidence and severity of OSMF.

In present study, clinical staging of all 860 OSMF patients was assessed. It was found that maximum patients were seen in stage II (46.42%) and stage III (34.52%), followed by stage I (10.73%) and stage IV (8.33%). Kumar found in his study of 1,006 OSMF patients, 422 (41.94%) cases were stage II. Two hundred and twenty six (22.29%) were stage IV, 184 (18.29%) stage III, and 174 (17.29%) stage I which is somewhat different to present study.[22] This could be on the grounds that in the early cases significant changes particularly, limited mouth opening are not seen, and unless there is a significant affection of the functions patient's body, patients won’t approach the doctor, and furthermore an absence of information about the illness can likewise ascribe to this.

The conversion of premalignant to malignant condition varies from 3% to 19%. A recent study from India has reported that 25.77% OSF cases converted to oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) which indicates the alarming malignant potential of OSMF.[23]

Epidemiological data accumulated over a wide geographical area will help to determine the overall incidence and prevalence rates and formulate appropriate prevention and control measures. High risk individual and population for tobacco usages needs to be targeted and intervention should be done at community level. Policies need to be laid down by concerned policy makers to curb this ever progressing menace. Primary healthcare professionals and dentists should play an active role in prevention and control of tobacco induced lesions as they are generally the first point of contact with patients who are at increased risk.

Conclusion

The easy availability and promotions of these areca nut products especially gutkha and pan masala in social places has impacted general population in India which has led to the increased occurrence of OSMF, a premalignant condition. In present study, the occurrence of OSMF in gutkha chewers is far faster and more severe as compared with other forms of areca nut products chewers. Frequency of the habit showed statistical significance indicating that as frequency of habit increases, severity of the disease also increased. The high prevalence of OSMF requires significant awareness and management of these lesions among general population. Primary healthcare professionals including dentists should be knowledgeable and familiar with the etiopathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of these lesions.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gupta SC, Yadav YC. “MISI” an etiologic factor in oral submucous fibrosis. Indian J Otolaryngol. 1978;30:5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murti PR, Bhonsle RB, Gupta PC, Daftary DK, Pidborg JJ, Mehta FS. Etiology of oral submucous fibrosis with special reference to the role of arecanut chewing. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:145–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1995.tb01156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pindborg JJ, Sirsat SM. Oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Med Oral Pathol. 1966;22:764–79. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(66)90367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seedat HA, Van Wyk CW. Submucous fibrosis (SF) in exbetel nut chewers: A report of 14 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 1988;17:226–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1988.tb01529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nair U, Bartsch H, Nair J. Alert for an epidemic of oral cancer due to use of the betel quid substitutes gutkha and pan masala: A review of agents and causative mechanisms. Mutagenesis. 2004;19:251–62. doi: 10.1093/mutage/geh036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pickwell SM, Schimelpfening S, Palinkas LA. ‘Betelmania’. Betel quid chewing by Cambodian women in the United States and its potential health effects. West J Med. 1994;160:326–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van der Waal I. Potentially malignant disorders of the oral and oropharyngeal mucosa; terminology, classification and present concepts of management. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:317–23. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hazarey VK, Erlewad DM, Mundhe KA, Ughade SN. Oral submucous fibrosis: Study of 1000 cases from central India. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:12–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta PC, Ray CS. Smokeless tobacco and health in India and South Asia. Respirology. 2003;8:419–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tilakaratne WM, Klinikowski MF, Saku T, Peters TJ, Warnakulasuriya S. Oral submucous fibrosis: Review on aetiology and pathogenesis. Oral Oncol. 2006;42:561–8. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pai SA. Gutkha banned in Indian states. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:521. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00862-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard School of Public Health; 1996. The global burden of disease: A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bansal SK, Leekha S, Puri D. Biochemical changes in OSMF. J Adv Med Dent Sci. 2013;1:101–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang SF, Wang YH, Su NY, Yu HC, Wei CY, Yu CH, et al. Changes in prevalence of precancerous oral submucous fibrosis from 1996 to 2013 in Taiwan: A nationwide population-based retrospective study. J Formos Med Assoc. 2018;117:147–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinor PN, Gupta PC, Murti PR, Bhonsle RB, Daftary DK, Mehta FS, et al. A case-control study of oral submucous fibrosis with special reference to the etiologic role of areca nut. J Oral Pathol Med. 1990;19:94–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1990.tb00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehrotra R, Pandya S, Chaudhary AK, Kumar M, Singh M. Prevalence of oral pre-malignant and malignant lesions at a tertiary level hospital in Allahabad, India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9:263–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehrotra D, Kumar S, Agarwal GG, Asthana A, Kumar S. Odds ratio of risk factors for oral submucous fibrosis in a case control model. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:e169–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babu S, Bhat RV, Kumar PU, Sesikaran B, Rao KV, Aruna P, et al. A comparative clinico-pathological study of oral submucous fibrosis in habitual chewers of pan masala and betelquid. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1996;34:317–22. doi: 10.3109/15563659609013796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nigam NK, Aravinda K, Dhillon M, Gupta S, Reddy S, Srinivas Raju M. Prevalence of oral submucous fibrosis among habitual gutkha and areca nut chewers in Moradabad district. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2014;4:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah N, Sharma PP. Role of chewing and smoking habits in the etiology of oral submucous fibrosis (OSF): A case-control study. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27:475–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1998.tb01915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ali FM, Aher V, Prasant MC, Bhushan P, Mudhol A, Suryavanshi H. Oral submucous fibrosis: Comparing clinical grading with duration and frequency of habit among areca nut and its products chewers clinical grading of OSMF in Arecanut and its products chewers. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:471–6. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.119353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar S. Oral submucous fibrosis: A demographic study. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2016;28:124–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acharya S, Rahman S, Hallikeri K. A retrospective study of clinicopathological features of oral squamous cell carcinoma with and without oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2019;23:162. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_275_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]