Abstract

Objective

This prospective, longitudinal investigation examined psychological violence across generations. We examined how parent psychological violence experienced during adolescence influenced the stability of one’s own intimate partner psychological violence perpetration across time and how psychological violence is related to harsh parenting in adulthood.

Method

Data came from 193 parents and their adolescent who participated from adolescence through adulthood. Parental psychological violence was assessed in early adolescence. Partner violence was assessed in late adolescence, emerging adulthood, and adulthood. Harsh parenting to their offspring was assessed in adulthood.

Results

Parent psychological violence in early adolescence was associated with one’s own intimate partner psychological violence in late adolescence. Partner psychological violence was stable from emerging adulthood to adulthood. Moreover, parental violence was also related to their own harsh parenting in adulthood.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that children exposed to parental psychological violence during adolescence may have greater difficulty developing acceptable behaviors in their own romantic relationships over time, as well as parenting their own child in adulthood. Findings highlight the importance for clinicians and policy makers to develop and utilize effective educational and preventive interventions designed toward not only adolescent behaviors, but also that of the parent. Understanding how the family environment impacts current and long-term functioning is important in helping stop the cycle of violence across generations.

Keywords: domestic violence, harsh parenting, psychological perpetration, stability of violence, intergenerational transmission

The intergenerational transmission of violence is well documented. Studies show that violence in the family of origin leads to violence in the family of procreation. For example, abusive parenting experienced during childhood may be related to long-term health consequences such as poor psychological outcomes, as well as higher levels of problem behavior (Norman, et al., 2012). Moreover, abusive parenting received in the family of origin has been linked to outcomes such as maltreatment of one’s own partners or children (Black, Sussman, & Unger, 2010). Indeed, as adults, children who grew up with abusive parents tend to emulate this type of behavior, as these early experiences may exacerbate tendencies toward aggressive conduct in general (Caspi & Elder, 1988). However, the literature is limited in investigations that are prospective and longitudinal across generations. Thus, the purpose of this study is to assess how parental behaviors experienced during adolescence influence one’s own intimate partner relationships over time and harsh parenting to one’s own offspring in adulthood.

The developmental-interactional model of aggression (Capaldi & Gorman-Smith, 2003) posits that social learning processes within the family of origin lead to the development of interpersonal characteristics common in aggression or violence, otherwise referred to as the intergenerational transmission of violence (Straus, Gelles, & Steinmetz, 1980; Capaldi & Clark, 1998). Indeed, children learn through observing the behaviors of others. Thus, children who experience abusive parenting could model that same behavior to their own family in adulthood. That is, children who were abused by their parents are more likely to grow up to behave aggressively toward a romantic partner or practice harsh parenting to their own children as adults (Hughes & Cossar, 2016; Lohman, Neppl, Senia, & Schofield, 2013; Neppl, Conger, Scaramella, & Ontai, 2009). Further, there is evidence that abusive parenting co-occurs with abusive interactions with a romantic partner and these behaviors may be stable over time (Greeson et al., 2014). Indeed, trait theory would suggest this is because aggression is a stable characteristic across time and circumstance (e.g., Huesmann, Eron, Lefkowitz, & Walder, 1984).

While the intergenerational transmission of violence toward intimate partners or children has been well documented, earlier studies have been predominately cross–sectional or retrospective and often limited by single reporters and non-population based samples (Hughes & Cossar, 2016; Lohman, et al., 2013). Studies may also be limited by the reliance of court records to quantify abuse which may not generalize to non-reported abuse cases (Berlin, Appleyard, & Dodge, 2011). Moreover, there is a lack of research conducted on psychological maltreatment, as earlier studies have mainly focused on the transmission of physical violence or neglect (Caetano, Rield, Ramisetty-Mikler, & McGrath, 2005; Hines, Malley-Morrison, & Dutton, 2013; Infurna et al., 2016; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Hankla, & Stormberg, 2004). This is important to examine because violence such as physical abuse often co-occurs with psychological abuse, and the prevalence of psychological violence may be higher in both community and at-risk samples (Lawrence, Yoon, Langer, & Ro, 2009).

Thus, the current study examined continuities in violence prospectively across two generations of families who were followed from adolescence to adulthood. Specifically, we examined the influence of generation 1 (G1) to generation 2 (G2) psychological violence experienced in early adolescence on the stability of G2 intimate partner psychological violence perpetration from late adolescence, to emerging adulthood, to adulthood. We also examined the relation between G1 to G2 psychological violence in adolescence and G2 harsh parenting to the third generation (G3) child when G2 reached adulthood. Moreover, we assessed whether G1 to G2 violence is indirectly related to G2 to G3 harsh parenting by way of G2 to partner violence over time. Indeed, others have found that abuse in childhood is related to emotional distress and aggressive behaviors with others, which then leads to poor parenting practices in adulthood (Becker, Stuewig, & McCloskey, 2010; Ehrensaft, Knous-Westfall, Cohen, & Chen, 2015; Simons, Whitbeck, Conger, & Wu, 1991).

Psychological Violence

Psychological violence is defined as the use of both verbal and nonverbal communication with the intent to mentally or emotionally harm, and/or exert control over your partner (CDC, 2014). This type of abuse has been associated with both emotional and behavioral problems such as depression and antisocial behaviors, as well as impairments in future relationships (see Arslan, 2016; Hughes & Cossar, 2016). According to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (Black et al., 2011), 40% of women experienced violence such as insults or name calling at least once in their lifetime and 41% had experienced coercive control in their lifetime. Psychological violence can be experienced independently but can also co-occur with other forms of maltreatment (see Hughes & Cossar, 2016).

Indeed, psychological violence has been identified as a predictor of physical violence in romantic relationships (Frye & Karney, 2006), and the impact of psychological violence may be as salient if not more so than physical abuse (Hattery & Smith, 2013). Thus, according to Hughes and Cossar (2016), psychological violence could be the most common form of maltreatment and have the most detrimental impact on later functioning. Moreover, although many studies have focused on psychological violence in adulthood, fewer have focused on psychological violence as experienced in adolescence (Arslan, 2016). Therefore, rather than focus on physical or other forms of abuse, the current study specifically examines psychological violence experienced during early adolescence on perpetrated intimate partner psychological violence and harsh parenting in adulthood.

The Influence of Family of Origin Violence

In general, early exposure to intimate partner violence in the family of origin has been linked to increased risk of intimate partner violence in both emerging adulthood and adulthood (Foshee, Bauman, & Linder, 1999; Renner & Slack, 2006). In addition, adolescents who commonly witness intimate partner violence are exposed to parental abuse at co-occurring rates up to 80 percent (Saunders, 2003). Studies examining the effects of abusive parenting and interparental violence in childhood on intimate partner violence in adulthood have found that parenting (as compared to interparental violence) is the more robust predictor of adulthood violence over time (Stith, Rosen, Middleton, Lundeberg, & Carlton, 2000), particularly among studies using prospective rather than cross-sectional or retrospective data (Capaldi & Clark, 1998; Donnellan, Larsen-Rife, & Conger, 2005). Indeed, earlier findings from the longitudinal study used for the present analyses showed that parent (G1) to adolescent (G2) psychological violence, rather than interparental (G1) violence, predicted adolescents’ (G2) perpetrating psychological violence during adulthood (Lohman et al., 2013). Thus, children may learn strategies for communication and conflict-resolution from interactions with their parents. That is, when parents are abusive, it may make it difficult to establish healthy romantic relationships as an adult, above and beyond the effect from children observing aggressive interactions (Bryant & Conger, 2002).

Moreover, there is a wealth of evidence that exposure to parental violence in the family of origin increases the likelihood they will parent harshly as an adult (Caspi and Elder, 1988; Neppl, et al., 2009; Pears & Capaldi, 2001; Van Ijzendoorn, 1992). For example, in the same longitudinal study used for the present analyses, Conger, Neppl, Kim, and Scaramella (2003) found an association between observed G1 aggressive parenting and observed G2 aggressive parenting 5 to 7 years later. Similarly, Shaffer, Burt, Obradovic, Herbers, and Masten (2009) studied a sample of 10 year olds and found that twenty years later, they were displaying similar parenting practices as experienced in childhood. In addition, exposure to violence by parents in the family of origin may lead to more aggressive interactions with others, which in turn leads to harsh parenting to one’s own child as an adult (Simons, Whitbeck, Conger, & Wu, 1991). Taken together, these studies show evidence to support the developmental-interactional model of aggression (Capaldi & Gorman-Smith, 2003). However, few studies have examined the association between parental psychological violence experienced in childhood and harsh parenting in adulthood (Hughes & Cossar, 2016). Indeed, in a recent review, Hughes and Cossar (2016) found mixed evidence for the relation between mother reported histories of emotional abuse and later parenting competencies. Thus, the current study addresses this gap by prospectively assessing how parental psychological violence is related to later harsh parenting, as well as the stability of intimate partner psychological violence over time.

Stability of Intimate Partner Violence

Research suggests that emerging adulthood is a time where romantic relationships develop and young adults assess what is acceptable behavior within their relationships (Fincham & Cui, 2011). However, not as much is known about the stability of such relationship behaviors across time. For example, some have found that abusive behavior in romantic relationships is relatively stable over time (Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Fritz & Slep, 2009; Lohman et al., 2013). Capaldi et al. (2003) found that stability of intimate partner violence across two time points (2.5 years) was higher for men (15.6 – 27.4 years old) who stayed with the same partner versus those who had a new partner. Others have found that intimate partner violence occurs at its highest levels in emerging adulthood and then decreases with age (Kim, Laurent, Capaldi, & Feingold, 2008).

Moreover, much of the literature has focused on changes in violent behavior within a single romantic relationship over time rather than patterns of intimate partner violence across several different relationships. For example, it may be that continuity in intimate partner violence occurs due to assortative mating, where adults tend to select partners who are similar to themselves in terms of exposure to family violence in the family of origin which are predictors of intimate partner violence in adulthood (Kim & Capaldi, 2004). All told, little work has addressed the stability of intimate partner violence across relationships over a significant period of time (Fritz & Slep, 2009). We address this gap by prospectively assessing the stability of intimate partner psychological violence perpetration from late adolescence to adulthood.

The Present Investigation

The present study evaluated how G1 to G2 psychological violence during early adolescence influences the stability of G2 psychological violence perpetration toward a partner from late adolescence to adulthood. Moreover, we evaluated how G1 to G2 and G2 to partner psychological violence relates to G2 harsh parenting to G3 in adulthood. Following our review of the literature, we expected that G1 to G2 psychological violence in early adolescence would be associated with G2 psychological violence toward a partner in late adolescence. We also expected that G2 violence toward a partner would be stable from late adolescence to emerging adulthood to adulthood. Moreover, we expected that G1 to G2 violence in early adolescence would be associated with G2 harsh parenting to G3 in adulthood. It was expected that this association might be explained through G2 to partner violence in emerging adulthood, with partner violence in adulthood co-occurring with harsh parenting in adulthood.

Method

Participants

Data come from the Iowa Youth and Families Project (IYFP) which were collected annually from the G1 family of origin (N = 451) from 1989 through 1992. Participants included the G2 adolescent (52% female), his or her G1 parents, and a sibling within 4 years of age of the adolescent. When families were interviewed for the first time in 1989, adolescents were in seventh grade (M age = 12.7 years; 236 females). Families were recruited from both public and private schools in eight rural counties in Iowa. Due to the rural nature of the sample there were few minority families; therefore, all participants were Caucasian. Seventy–eight percent of eligible families agreed to participate in the initial study. Families were primarily lower middle– or middle–class. When the study began in 1989, G1 parents averaged 13 years of schooling and had a median family income of $33,700. Families ranged in size from 4 to 13 members, with an average size of 4.94 members. Fathers’ average age was 40 and mothers’ average age was 38.

In 1994, families from the IYFP continued in another project, the Family Transitions Project (FTP). The same G2 adolescents were followed in their transition from adolescence to adulthood. Beginning in 1995, G2 adolescents (one year after completion of high school), now emerging adults, participated in the study with their romantic partner. By 1997, the project expanded to include the first-born child of the G2 adults. Overall, the FTP has followed G2s from 1989 to 2005 (M target age = 32 years), with a 90% retention rate.

The present study examines G2s who participated with their G1 parents, romantic partner, and G3 first born child from 1990 to 2005 (N = 193). These G2s differ from the original sample in that the present investigation only includes G2s who had a child by 2005 (43% of the original sample). A total of 108 2–5-year olds and 85 6–13-year-olds participated (M age = 5.55 years; 52% boys). The data were analyzed at four developmental periods. The first was when G2 was in early adolescence (13, 14, and 15 years old). The second development period was when G2 was in late adolescence (16, 18, and 19 years old). The third developmental period was when G2 was in emerging adulthood (21 and 23 years old) and the last development period occurred when G2 was in adulthood (age 29). The time gap between emerging adulthood and adulthood was to ensure an adequate number of G2s with children.

Throughout adulthood, G2s participated with a romantic partner at the time of the visit. A romantic partner could be a boy/girlfriend, a cohabitating partner, or a married spouse. Between ages 16–19, 75% (n = 144) of the adolescents were in an intimate relationship and 94% reported psychological violence. In emerging adulthood 58% were married, 21% were cohabiting, and 12% were dating, with 96% reporting psychological violence. Finally, in adulthood, 81% were married, 11% were cohabiting, and 4% were dating, with 97% reporting psychological violence within their relationship.

Measures

G1 to G2 psychological violence during early adolescence (age 13–15)

G1 parent psychological violence to the G2 adolescent was measured with information from two informants: G2 adolescent report of their father and mother behavior to him/her and observer report of mother and father behavior to the G2 adolescent. The G2 report of father and mother psychological violence included 4 items asking the adolescent how often during the past month their father and mother got angry at him/her, criticized him/her for his/her ideas, shouted or yelled at him/her because she was mad, or argued with him/her whenever she disagreed about something. Responses ranged from 1 = always to 7 = never. After being reverse coded, the items were averaged together. Internal consistency reliability was acceptable for adolescent report of father (mean α = .88) and mother (mean α = .88). The measure has been used in other studies with demonstrated validity (Cui, Durtschi, Donnellan, Lorenz, & Conger, 2010).

Observer report of G1 parental psychological violence to the G2 adolescent was measured using the parent–child discussion interaction task and the family problem solving interaction task. Trained observers coded the degree to which the father and mother engaged in verbal attacks toward the adolescent. Verbal attack was defined as personalized and unqualified disapproval of another person’s personal characteristics and criticism of an enduring nature. Observer ratings were scored on a 9-point scale, ranging from low (no evidence of the behavior) to high (the behavior is highly characteristic of the parent). Percentage of agreement for the observed scales for father behavior to adolescent and mother behavior to adolescent were .88 and .86 respectively. Since adolescent self–report of their father and mother, and observer ratings of parent’s behavior were measured using different scales, scores were standardized and then averaged into one manifest variable.

G2 psychological violence to partner during late adolescence (age 16 – 19)

G2’s psychological violence to their partner in adolescence was measured through self-report. Adolescent report of psychological violence to their partner included 4 items asking how often during the past month G2 got angry at their partner, criticized their partner for his/her ideas, shouted or yelled at their partner because he/she was mad, or argued with their partner whenever he/she disagreed about something. Responses ranged from 1 = always to 7 = never. After reverse coded, items were averaged together across the three time points to create one manifest variable. Internal consistency reliability was acceptable (α= .83).

G2 psychological violence to partner during emerging adulthood (ages 21 – 23) and adulthood (age 29)

G2’s psychological violence to their partner was measured with information from two informants: partner report of G2’s behavior to the partner and observer report of G2’s behavior to their partner. Partner report of G2’s psychological violence included 4 items asking how often during the past month G2 got angry at the partner, criticized the partner for his/her ideas, shouted or yelled at the partner because he/she was mad, or argued with the partner whenever he/she disagreed about something. Responses ranged from 1 = always to 7 = never. After being reverse coded, items were averaged together (for emerging adulthood items across the two time points were averaged) and the internal consistency reliability was acceptable (α = .88 for emerging adulthood and .90 for adulthood).

Trained observers coded the degree to which G2 engaged in verbal attacks to their romantic partner during a videotaped discussion task (described earlier). Verbal attack was defined and coded in the same manner as the previous observational tasks. Observer ratings were scored on a 9-point scale, ranging from low (no evidence of the behavior) to high (the behavior is highly characteristic). The percentage of agreement for the observed scales across the two time points were .79 and .80, respectively. Since partner report and observer ratings of G2’s behavior were measured using different scales, the scores were standardized and then averaged together to create one manifest variable.

G2 to G3 harsh parenting in adulthood (age 29)

Direct observations assessed G2 harsh parenting behaviors to their G3 child during videotaped interaction tasks (described earlier). Observer ratings were used to assess G2’s verbal attack, hostility, antisocial behavior, and angry coerciveness toward their G3 child. Each rating was scored on a 9-point scale, ranging from low (no evidence of the behavior) to high (the behavior is highly characteristic of the parent). Each scale was averaged across tasks and then averaged together to create one manifest variable. Verbal attack was defined and coded in the same manner as the previous observational tasks. Hostility measures hostile, angry, critical, disapproving and/or rejecting behavior. Antisocial is the demonstration of socially irresponsible behavior, including resistance, defiance, and insensitivity. Angry coercion is the attempt to control or change the behavior of another in a hostile manner. It includes demands, hostile commands, refusals, and threats. The scores for the harsh parenting construct were internally consistent (alpha = .89) and inter-rater reliability was substantial (.94). The measure also demonstrated adequate validity (Neppl et al., 2009).

Control Variables

The control variables included G1 and G2 per capita income, as family income is related to harsh parenting (Conger & Donnellan, 2007) and is a risk factor for intimate partner violence (Rennison & Planty, 2003); and G2 relationship status since single parents may be at greater risk for ineffective parenting than those parents who are married (Simons, Beaman, Conger, & Chao, 1993). Family of origin income was assessed by G1 mother and G1 father report of family per capita income in 1990 and 1991. The mean across both waves was divided by 1,000 for the ease of analysis and interpretation in this study. It should be noted that family per capita income included negative values because some families had negative net farm income. G2 income was assessed by G2 and romantic partner report of family per capita income in 2005 (age 29). G2 relationship status was reported by G2 (1 = married, 2 = cohabiting, 3 = part-time cohabiting, 4 = steady romantic relationship, 5 = dating, 6 = not dating) in 2005 (age 29). The means, standard deviations, and minimum and maximum scores for all study variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables (N = 193)

| Variables | M | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G2 to Partner Psychological Violence | ||||

| Late Adolescence Perpetration | ||||

| Self-report | 2.32 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 5.25 |

| Emerging Adulthood Perpetration | ||||

| Observer report | 1.65 | 0.94 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Partner report of Target | 2.59 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 5.50 |

| Adulthood Perpetration | ||||

| Observer report | 1.50 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 6.00 |

| Partner report of Target | 2.66 | 1.08 | 1.00 | 5.75 |

| G1 to G2 Psychological Violence during Early Adolescence | ||||

| Observer report of mother | 1.27 | 0.47 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Observer report of father | 1.31 | 0.47 | 1.00 | 3.00 |

| Adolescent report of mother | 2.84 | 0.92 | 1.08 | 6.08 |

| Adolescent report of father | 2.66 | 0.86 | 1.17 | 5.25 |

| G2 to G3 Harsh Parenting during Adulthood | ||||

| Verbal Attack | 1.36 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Hostility | 2.69 | 1.74 | 1.00 | 9.00 |

| Antisocial | 3.32 | 1.66 | 1.00 | 9.00 |

| Angry Coercion | 2.06 | 1.47 | 1.00 | 8.00 |

| Control Variables | ||||

| G1 Income | 8,330.15 | 5,097.98 | −1,058.11 | 39,200.00 |

| G2 Income | 18,738.34 | 10,021.27 | 3,340.00 | 63,375.00 |

Procedures

When G2 was in adolescence, all families of origin were visited twice in their homes each year by a trained interviewer. Each visit lasted approximately two hours, with the second visit occurring within two weeks of the first. During this first visit, each family member (G1 mother, G1 father, G2 adolescent) completed questionnaires pertaining to subjects such as parenting and quality of family interactions. During the second visit, each family member participated in four structured interaction tasks that were videotaped. In the present analyses, we used observer ratings from three of those tasks. The parent–adolescent discussion task involved G1 parents and the G2 adolescent engaging in a conversation about family rules and problems which lasted 30 minutes. The problem solving task lasted 15 minutes and involved all family members (G1, G2, and G2’s sibling) discussing and solving an issue they identified as problematic such as conflict over money or discipline. The marital interaction task involved only the G1 parents who engaged in a discussion of topics such as childrearing and other life events. Trained observers coded the quality of interactions using the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (Melby et al., 1998). These scales have been shown to demonstrate adequate reliability and validity across the different tasks (Melby & Conger, 2001).

When G2s were adults, they participated in the study with their romantic partner and G3 first born child. Each G2 adult and his or her partner were visited biennially in their home by a trained interviewer. During that visit, adults completed a series of questionnaires which included questions about their romantic relationship, as well as their own behavior and individual characteristics. In addition to questionnaires, the G2 adult and his or her romantic partner participated in a videotaped 25–minute discussion task that was essentially the same as that used for their G1 parents. The G2 adults (now parents themselves) were also asked to fill out questionnaires addressing parenting and child characteristics that were appropriate for their G3 child’s developmental age. In addition, each G2 participated in separate observed interaction tasks with their G3 child, depending on the child’s age. The parent-child interaction tasks consisted of a puzzle task (2–9 years old), clean-up task (2–5 years old), peanut butter task (6–7 years old), and parent to child discussion task (8–13 years old). Each task was designed to create a stressful environment to ascertain how parents handle these types of stressors with their children during a structured task.

For the puzzle task, G2 parents and their G3 children were presented with a puzzle that was too difficult for the child to complete alone. Parents were instructed that children must complete the puzzle alone, but they could provide any assistance necessary. The task lasted 5 minutes. Puzzles varied by age group so that the puzzle slightly exceeded the child’s skill level. The clean-up task was completed at the end of the in-home visit. The task began after the child played with a variety of toys, first alone and then with the interviewer present. The G2 parent was asked to return to the room and instructed that it was time for their child to clean-up the toys. The parent was informed that he or she could offer help to the child as necessary, but the child was expected to clean-up the toys alone. For the peanut butter task, the child was instructed to make as many peanut butter snacks as they could within 6 minutes. After the snacks were made, the child was expected to clean up. The G2 parent was instructed that he or she could offer help as necessary, but the child was expected to clean-up alone. The parent-child discussion task was essentially the same as that used for the G2 parent-child discussion task during adolescence.

Data Analysis

SEMs were analyzed using Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén) software package. Because missing cases on all variables were largely due to unavailability of data for a specific wave rather than participants no longer participating in the study, the present analyses used Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation processes to test hypothesized associations (Allison, 2003) rather than deleting cases with any missing data. All theoretical constructs were examined as manifest variables.

Evidence shows that females may perpetrate intimate partner violence more often than males (Feiring, Deblinger, Hoch-Espada, & Haworth. 2002; Kaura & Allen, 2004). Thus, gender was tested as a moderator. First, we examined an unconstrained multigroup model with the focal paths set to be unconstrained across gender. Next, we examined a constrained model with the focal paths set to be equal across gender. Chi-square difference tests were nonsignificant (p > .05) when comparing the unconstrained model to the constrained model across gender. Thus, gender was not supported as a moderator; we present the results for both male and female adolescents combined.

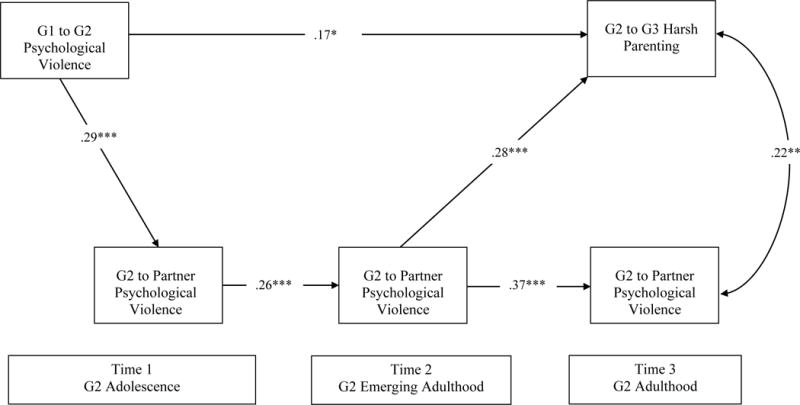

The SEMs were then estimated in two ways. First, models were estimated with all of the control variables in the analyses. Second, the models were refigured to exclude these control variables. Separate analyses generated similar findings; therefore, we present the results without the inclusion of the control variables. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993) and the comparative fit index (CFI; Hu & Bentler, 1999) were examined to evaluate the fit of the structural model to the data. RMSEA values under .05 indicate close fit to the data, and values between .05 and .08 represent reasonable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). For the CFI, fit index values should be greater than .90, and preferably greater than .95, to consider the fit of a model to data to be acceptable. This model showed an acceptable fit, χ2 (4) = 8.05, p < .10, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .072, and was the model used for our primary analyses. Standardized coefficients from the final model which reached statistical significance are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structure Equation Model

Note. Standardized coefficients for direct paths. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Results

Correlations

Correlations among study variables are presented in Table 2. G1 to G2 psychological violence in early adolescence was positively associated with G2 to partner psychological violence in late adolescence. Moreover, G2 to partner violence in late adolescence was positively related to G2 to partner violence in emerging adulthood, and G2 to partner violence in emerging adulthood was positively associated with G2 to partner violence in adulthood. In addition, G1 to G2 violence in early adolescence was associated with G2 to G3 harsh parenting in adulthood. G2 psychological violence in emerging adulthood was positively associated with G2 harsh parenting in adulthood, and G2 to partner violence in adulthood was also related to G2 to G3 harsh parenting in adulthood. The patterns of associations were generally supportive of the theoretical model, and justified the formal model testing that follows.

Table 2.

Correlations among Variables Used in Analyses

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. G2 to Partner Late Adolescence | |||||||||

| 2. G2 to Partner Emerging Adulthood | .30*** | ||||||||

| 3. G2 to Partner Adulthood | .14 | .40** | |||||||

| 4. G1 to G2 Psychological Violence | .31** | .11 | .23** | ||||||

| 5. G2 to G3 Harsh Parenting | .24** | .28** | .26** | .23** | |||||

| 6. G1 Per Capita Income | .05 | −.07 | −.14 | −.02 | −.10 | ||||

| 7. G2 Per Capita Income | .05 | −.01 | −.11 | −.18* | −.23** | .28** | |||

| 8. G2 Relationship Status | .18* | .09 | .02 | .18* | .16* | −.06 | −.11 | ||

| 9. G2 Gender | −.14 | −.38** | −.21** | −.18* | −.00 | .02 | −.03 | −.05 | |

| 10. G3 Gender | .00 | .13 | .02 | .21** | −.03 | −.02 | −.08 | .10 | .02 |

Notes.

p < .05.

p<.01.

Structural Equation Analyses

G1 to G2 psychological violence during G2’s early adolescence was significantly associated with G2 partner psychological violence perpetration in late adolescence (β = .29, SE = .07). G2 to partner violence in late adolescence was significantly associated with G2 to partner violence in emerging adulthood (β = .26, SE = .07), and G2 to partner violence in emerging adulthood was significantly associated with G2 to partner violence in adulthood (β = .37, SE = .07). G1 to G2 violence in early adolescence was associated with G2 harsh parenting to G3 in adulthood (β = .17, SE = .08). Finally, G2 to partner violence in emerging adulthood (β = .28, SE = .07) and G2 to partner violence in adulthood (β = .22, SE = .08) were both associated with G2 harsh parenting in adulthood. The following points were also tested and found to be non-significant: 1) G1 to G2 psychological violence to G2 emerging adulthood psychological violence; 2) G2 psychological violence in adolescence to G2 psychological violence in emerging adulthood; and, 3) G2 psychological violence in adolescence to harsh parenting from G1 towards G2.

Indirect effects

In addition to examining direct paths within the model, mediation analyses were conducted in Mplus with 95% CIs constructed by bias-corrected bootstrapping (1,000 samples) to provide a more accurate estimation of the SEs (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). G1 to G2 psychological violence during G2’s adolescence was indirectly associated with G2 partner psychological violence perpetration in adulthood via G2 to partner violence in late adolescence and emerging adulthood, 95% CI [.009, .058]. That is, psychological violence in late adolescence worked through psychological violence in emerging adulthood to predict adulthood psychological violence. In addition, G1 to G2 psychological violence during G2’s adolescence was also indirectly associated with G2 harsh parenting to G3 in adulthood via G2 to partner violence in late adolescence and emerging adulthood, 95% CI [.008, .046]. Furthermore, the effect of G2 to partner violence in adolescence on G2 harsh parenting in adulthood, as mediated by G2 partner psychological violence perpetration in emerging adulthood, was significant, 95% CI [.035, .127]. Moreover, the effect of G2 to partner violence in adolescence on G2 partner psychological violence perpetration in adulthood, as mediated by G2 partner psychological violence perpetration in emerging adulthood, was also significant, 95% CI [.038, .159].

Discussion

The current investigation examined the influence of parental psychological violence during early adolescence on the stability of one’s own intimate partner psychological violence perpetration from late adolescence to adulthood. We also examined the association between parental violence and adolescent intimate partner violence on the adolescent’s harsh parenting toward their offspring during adulthood. This study adds to the sparse literature that has prospectively examined psychological maltreatment across time. The lack of research may be due to the visible consequences of physical violence and the assumption that these consequences are more severe than those of psychological violence. Yet, psychological violence often predicts physical violence, can co-occur with physical violence, or occur in the absence of physical violence. Moreover, studies show that the emotional and long-term relationship consequences of psychological violence may actually be more severe than the consequences of physical violence as it instills fear, increases dependency on the abusive partner, and lowers self-esteem (see Hines, Malley-Morrison, & Dutton, 2013). This is not to say, however, that physical violence does not have major physical and emotional consequences, but that the influence of psychological violence is important to consider as well.

Also important, the current study employs a research design that overcomes some of the methodological limitations found in earlier studies of intimate partner violence and parenting. First, it uses a prospective, longitudinal research design thus eliminating retrospective biases inherent in measures based on recall of adolescent experiences. Second, the current investigation also used multiple informants, including observer report, self-report, and partner report of psychological violence. This approach reduces method variance biases produced by reliance on a single informant. It is particularly noteworthy that the magnitude of the association between parental psychological violence in adolescence and one’s own intimate partner psychological violence in adulthood was similar to psychological violence in emerging adulthood and harsh parenting in adulthood. This is remarkable given that one set of associations is primarily based on self-report and the other on observational report.

Research Implications

Altogether, the results replicate and extend previous studies examining the intergenerational transmission of violence. For example, abusive parenting in the family of origin has been linked to both intimate partner violence (Black et al., 2010) and harsh parenting (Neppl et al., 2009) in adulthood. It also adds to the sparse research on the stability of psychological violence perpetration across time (Fritz & Slep, 2009). The current study helps to expand previous research by not only focusing on exposure to parent psychological violence in the family of origin on harsh parenting in adulthood, but also the stability of partner psychological violence perpetration from adolescence through adulthood. Results suggest that parental psychological violence in early adolescence is related to one’s own intimate partner psychological violence perpetration in late adolescence, which remains stable across time. Parental violence in early adolescence is also associated with adolescent harsh parenting toward their offspring in adulthood, with a significant indirect effect through partner violence into emerging adulthood. Thus, it appears that the intergenerational transmission of violence may exist not only for harsh parenting in a subsequent generation, but also for psychological violence perpetration toward a partner which appears to be stable across time.

Limitations

It should be acknowledged the present findings may have been associated with additional factors that we did not measure here. For example, genetic influences may help account for individual differences in parenting and psychological violent behavior. Indeed, it has been found that dopamine is associated with antisocial personality traits (Ponce et al., 2003), conduct problems (Lahey et al., 2011), and impulsivity (Joyce et al., 2009); while serotonin genes are linked to neuroticism (Gonda et al., 2009) and aggression (Beitchman et al., 2006); all of which could impact harsh parenting and psychological violence. Thus, future research should explore not only the importance of parenting and psychological violence, but how genetics influence such behaviors. In addition, future work could assess the inclusion of other known risk factors for partner and parent to child violence, such as substance abuse (e.g., Feingold, Kerr, & Capaldi, 2008) and antisocial behavior (e.g., Moffitt, Caspi, Rutter, & Silva, 2001).

A further limitation of this study is the relatively low correlations between psychological violence across time. This could be due to multiple informants which may actually provide stronger evidence for these associations given that violence was measured by different reporters across time. In addition, using a likert scale for frequency of violence with an anchor of “always” may not be a valid indicator of frequency, as well as the use of past month as the indicator of psychological violence. However, similar measures have been used in other papers and have demonstrated validity and reliability (e.g., Arslan, 2016; Cui, et al., 2010; Fritz & Slep, 2009; Zhang, Ma, & Chen, 2016). Relatedly, in our measure of psychological violence, the items get angry and argues may potentially overlap with marital conflict. However, the general model remained unchanged with those items excluded from the measure. The sample was limited in terms of ethnic and racial diversity, as well as geographic location. Thus, results may not generalize to low income or ethnic minority families. In addition, all adolescents lived with both biological parents. Future research using more diverse samples is needed. Finally, because a limited number of adolescents were in dating relationships in middle adolescence, we were not able to assess parental violence and adolescent to partner violence during the same time frame.

Clinical and Policy Implications

Results suggest parent-to-child psychological violence experienced during adolescence has impacts that last into adulthood. Interactions between adolescents and their parents marked by high anger, yelling, and/or criticism not only influences psychological violence towards romantic partners, it also impacts their own later parenting. Moreover, psychological partner violence in adolescence impacts psychological violence in emerging adulthood and adulthood, suggesting continuity of behavior across time. These are important findings with potential applied implications that highlight the importance for clinicians and policy makers to use and develop effective educational and preventive interventions designed to promote healthy relationships. For example, adolescents exposed to parental abusive interactions may have greater difficulty developing acceptable behaviors in their own interpersonal and romantic relationships. When clinicians and educators teach healthy romantic relationships in adolescence, they must remember that it is not only adolescent behaviors that matter, but also the parent.

For example, the Safe Dates evidenced based school prevention program focuses on decreasing adolescent dating violence over time. This program targets adolescent behaviors by changing dating violence norms, gender stereotyping, conflict-management skills, and cognitive factors associated with help-seeking (Foshee et al., 1996). Safe Dates also includes an evidence-based family program. Given the current results, it is important that prevention programs implement a family component as the family environment may not only impact current functioning but also has long-term implications in regards to future parenting and romantic relationships. In short, programs should emphasize the continuity of psychological violence and its potential to impact future relationships with partners and adolescents’ own offspring.

Acknowledgments

This research is currently supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (AG043599). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. Support for earlier years of the study also came from multiple sources, including the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD064687), National Institute of Mental Health (MH00567, MH19734, MH43270, MH59355, MH62989, MH48165, MH051361), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA05347), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD027724, HD051746, HD047573), the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health (MCJ-109572), and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development Among Youth in High-Risk Settings.

Contributor Information

Tricia K. Neppl, Assistant Professor, Dept. of Human Development and Family Studies, Iowa State University, 4389 Palmer Suite 2358, Ames, IA 50011; phone: 515-294-8502

Brenda J. Lohman, Email: blohman@iastate.edu, Professor, Dept. of Human Development and Family Studies, Iowa State University, 4389 Palmer Suite 2356, Ames, IA 50011; phone: 515-294-6230.

Jennifer M. Senia, Email: jmsenia@tamu.edu, Post-Doctoral Student, Dept. of Psychology, Texas A&M University,, 4235 TAMU Psychology Building, College Station, TX, 77843; phone: 979-845-2581.

Shane Kavanaugh, Email: sfortner@iastate.edu, Doctoral Student, Dept. of Human Development and Family Studies, Iowa State University, 86 LeBaron, Ames, IA 50011.

Ming Cui, Email: mcui@fsu.edu, Associate Professor, Dept. of Family and Child Sciences, Florida State University, 216 Sandels Building, Tallahassee, FL 32306; phone: 850-644-3217.

References

- Allison PD. Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:545–557. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arslan G. Psychological maltreatment, emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents: The mediating role of resilience and self-esteem. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2016;52:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitchman JH, Baldassarra L, Mik H, De Luca V, King N, Bender D, Ehtesham S, Kennedy JL. Serotonin transporter polymorphisms and persistent, pervasive childhood aggression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1103–1105. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.6.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KD, Stuewig J, McCloskey LA. Traumatic stress symptoms of women exposed to different forms of childhood victimization and intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:1699–1715. doi: 10.1177/0886260509354578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Appleyard K, Dodge KA. Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development. 2011;82(1):162–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DS, Sussman S, Unger JB. A further look at the intergenerational transmission of violence: Witnessing interparental violence in emerging adulthood. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2010;25:1022–1042. doi: 10.1177/0886260509340539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Stevens MR. The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Vol. 25 Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CM, Conger RD. An intergenerational model of romantic relationship development. In: Vangelisti AL, Reiss HT, Fitzpatrick MA, editors. Stability and change in relationships. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Field CA, Ramisetty-Mikler S, McGrath C. The 5-year course of intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:1039–1057. doi: 10.1177/0886260505277783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Clark S. Prospective family predictors of aggression toward female partners for at-risk young men. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1175–1188. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Gorman-Smith D. The development of aggression in young male/female couples. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 243–278. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Crosby L. Physical and psychological aggression in at-risk young couples: Stability and change in young adulthood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2003;49(1):1–27. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2003.0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Elder GH. Emergent family patterns: The intergenerational construction of problem behavior and relationships. In: Hinde RA, Stevenson-Hinde J, editors. Relationships within families: Mutual influences. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1988. pp. 218–240. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Understanding intimate partner violence fact sheet. 2014 Retrieved from: http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/IPV-FactSheet.pdf.

- Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Neppl T, Kim KJ, Scaramella L. Angry and aggressive behavior across three generations: A prospective, longitudinal study of parents and children. Journal of abnormal child psychology. 2003;31:143–160. doi: 10.1023/A:1022570107457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Durtschi JA, Donnellan MB, Lorenz FO, Conger RD. Intergenerational transmission of relationship aggression: A prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:688–697. doi: 10.1037/a0021675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Larsen-Rife D, Conger RD. Personality, family history, and competence in early adult romantic relationships. Journal of personality and social psychology. 2005;88:562–576. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes E, Chen H, Johnson JG. Intergenerational transmission of partner violence: a 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:741–753. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Knous-Westfall HM, Cohen P, Chen H. How does child abuse history influence parenting of the next generation? Psychology of Violence. 2015;5(1):16. doi: 10.1037/a0036080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A, Kerr DCR, Capaldi DM. Associations of substance use problems with intimate partner violence for at-risk men in long-term relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:429–438. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Deblinger E, Hoch-Espada A, Haworth T. Romantic relationship aggression and attitudes in high school students: The role of gender, grade, and attachment and emotional styles. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31:373–385. doi: 10.1023/A:1015680625391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz PAT, Slep AMS. Stability of physical and psychological adolescent dating aggression across time and partners. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:303–314. doi: 10.1080/15374410902851671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Cui M. Emerging adulthood and romantic relationships: An introduction. In: Fincham D, Cui M, editors. Romantic relationships in emerging adulthood. Florida: Cambridge; 2010. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Linder GF. Family violence and the perpetration of adolescent dating violence: Examining social learning and social control processes. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:331–342. doi: 10.2307/353752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Linder GF, Bauman KE, Langwick SA, Arriaga XB, Heath JL, Bangdiwala S. The Safe Dates Project: theoretical basis, evaluation design, and selected baseline findings. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1996;12(5):39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye NE, Karney BR. The context of aggressive behavior in marriage: A longitudinal study of newlyweds. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:12–20. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonda X, Fountoulakis KN, Juhasz G, Rihmer Z, Lazary J, Laszik A, Akiskal HS, Bagdy G. Association of the s allele of the 5-HTTLPR with neuroticism-related traits and temperaments in a psychiatrically healthy population. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2009;259:106–113. doi: 10.1007/s00406-008-0842-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeson MR, Kennedy AC, Bybee DI, Beeble M, Adams AE, Sullivan C. Beyond deficits: intimate partner violence, maternal parenting, and child behavior over time. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2014;54:46–58. doi: 10.1007/s10464-014-9658-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattery A, Smith E. The social dynamics of family violence. Westview Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA, Malley-Morrison K, Dutton LB. Family violence in the United States: Defining, understanding, and combating abuse. Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff for fit indexed in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR, Eron LD, Lefkowitz MM, Walder LO. Stability of aggression over time and generations. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:1120–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M, Cossar J. The relationship between maternal childhood emotional abuse/neglect and parenting outcomes: A systematic review. Child Abuse Review. 2016;25(1):31–45. doi: 10.1002/car.2393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Infurna MR, Reichl C, Parzer P, Schimmenti A, Bifulco A, Kaess M. Associations between depression and specific childhood experiences of abuse and neglect: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016;190:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce PR, McHugh PC, Light KJ, Rowe S, Miller AL, Kennedy MA. Relationships between angry-impulsive personality traits and genetic polymorphisms of the dopamine transporter. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66:717–721. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaura SA, Allen CM. Dissatisfaction with relationship power and dating violence perpetration by men and women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:576–588. doi: 10.1177/0886260504262966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Capaldi DM. The association of antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms between partners and risk for aggression in romantic relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:82–96. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Laurent HK, Capaldi DM, Feingold A. Men’s aggression toward women: A 10-Year panel study. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2008;70:1169–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ, Lee SS, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pelham WE, Waldman ID, Cook EH. Interactions between early parenting and a polymorphism of the child’s dopamine transporter gene in predicting future child conduct disorder symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:33–45. doi: 10.1037/a0021133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Hankla M, Stormberg CD. The relationship behavior networks of young adults: A test of the intergenerational transmission of violence hypothesis. Journal of Family Violence. 2004;19:139–151. doi: 10.1023/B:JOFV.0000028074.35688.4f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Yoon J, Langer A, Ro E. Is psychological aggression as detrimental as physical aggression? The independent effects of psychological aggression on depression and anxiety symptoms. Violence and Victims. 2009;24:20–35. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohman BJ, Neppl TK, Senia JM, Schofield TJ. Understanding adolescent and family influences on intimate partner psychological violence during emerging adulthood and adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:500–517. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9923-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales: Instrument summary. Institute for Social and Behavioral Research, Iowa State University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger R, Book R, Rueter M, Lucy L, Repinski D, Rogers S, Rogers B, Scaramella L. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales. 5th. Institute for Social and Behavioral Research, Iowa State University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA. Sex, antisocial behavior, and mating: Mate selection and early childbearing. In: Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA, editors. Sex differences in antisocial behavior: Conduct disorder, delinquency, and violence in the Dunedin Longitudinal Study. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 184–197. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 7th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Neppl TK, Conger RD, Scaramella LV, Ontai LL. Intergenerational continuity in parenting behavior: mediating pathways and child effects. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1241–1256. doi: 10.1037/a0014850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2012;9:e1001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Capaldi DM. Intergenerational transmission of abuse: A two-generational prospective study of an at-risk sample. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25:1439–1461. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponce G, Jimenez-Arriero MA, Rubio G, Hoenicka J, Ampuero I, Ramos JA, Palomo T. The A1 allele of the DRD2 gene (TaqI A polymorphisms) is associated with antisocial personality in a sample of alcohol-dependent patients. European Psychiatry. 2003;18:356–360. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2003.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner LM, Slack KS. Intimate partner violence and child maltreatment: Understanding intra-and intergenerational connections. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2006;30:599–617. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennison CM, Planty M. Nonlethal intimate partner violence: Examining race, gender, and income patterns. Violence and Victims. 2003;18:433–443. doi: 10.1891/vivi.2003.18.4.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders BE. Understanding children exposed to violence: Toward an integration of overlapping fields. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:356–376. doi: 10.1177/0886260502250840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer A, Burt KB, Obradović J, Herbers JE, Masten AS. Intergenerational continuity in parenting quality: the mediating role of social competence. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1227–1240. doi: 10.1037/a0015361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Beaman J, Conger RD, Chao W. Childhood experience, conceptions of parenting, and attitudes of spouse as determinants of parental behavior. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;55:91–106. doi: 10.2307/352961. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Whitbeck LB, Conger RD, Wu CI. Intergenerational transmission of harsh parenting. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:159–171. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.27.1.159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slep AMS, O’Leary SG. Parent and partner violence in families with young children: Rates, patterns, and connections. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:435–444. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Rosen KH, Middleton KA, Busch AL, Lundeberg K, Carlton RP. The intergenerational transmission of spouse abuse: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:640–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00640.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MMA, Gelles RJ, Steinmetz SK, editors. Behind closed doors: Violence in the American family. Transaction Publishers; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ijzendoorn MH. Intergenerational transmission of parenting: A review of studies in nonclinical populations. Developmental review. 1992;12:76–99. doi: 10.1016/0273-2297(92)90004-L. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Ma Y, Chen J. Child psychological maltreatment and its correlated factors in Chinese families. Social Work in Public Health. 2016;31(3):204–214. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2015.1088813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]