Abstract

Objective

Previous research has demonstrated a significant association between trauma and intimate partner aggression (IPA) perpetration. However, the precise mechanisms underlying this relationship have yet to be fully elucidated. In the present study, we examined the impact of several key factors implicated in Ehlers and Clark’s (2000) cognitive model of trauma (i.e., trauma cognitions, anger, hostility, and rumination) on IPA perpetration.

Method

Participants in this study were 271 male and female heavy drinkers at high risk for IPA from the community who completed measures of dysfunctional posttraumatic cognitions, dispositional rumination, trait anger and hostility, and IPA perpetration. A moderated mediational model was tested to determine how these variables interact to predict IPA perpetration.

Results

Results indicated that anger and hostility mediated the effect of negative cognitions about the world on IPA perpetration, with this indirect effect being stronger for individuals with higher levels of rumination.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that cognitive and affective processes that may result from trauma exposure are associated with IPA and should be targeted in prevention and intervention programs for individuals at risk for perpetration.

Keywords: trauma, cognitions, partner aggression, rumination, anger

Intimate partner aggression (IPA) is a serious public health problem that affects the lives of millions of men and women each year. IPA is associated with numerous negative consequences, including mental and physical health problems, increased use of legal and housing services, and financial burden of up to $5.8 billion annually (Black et al., 2011; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2003). According to a recent national survey, it is estimated that over their lifetime, approximately 24% of women and 14% of men in the United States experience severe physical violence from their intimate partner, while as many as one third (32.9%) of women and more than a quarter (28.2%) of men in the United States are victims of mild or severe physical IPA (Black et al., 2011). These estimates are consistent with rates of IPA obtained in international population-based surveys (World Health Organization, 2012). While the prevalence and negative consequences of IPA are well-known, it is clear that more research is needed to better understand the precise mechanisms through which IPA perpetration occurs. The purpose of the current study was to investigate one potential pathway through which dysfunctional cognitive and affective mechanisms may lead to IPA perpetration.

Past research has identified many possible risk factors for IPA perpetration, one of which is trauma exposure (Bell & Orcutt, 2009; Maguire et al., 2015; Parrott, Drobes, Saladin, Coffey, & Dansky, 2003; Taft, Watkins, Stafford, Street, & Monson, 2011). The relationship between trauma and IPA has been theorized to be driven by factors such as cognitive distortions and emotion dysregulation that arise as a result of experiencing trauma (Bell & Orcutt, 2009; Chemtob, Novaco, Hamada, Gross, & Smith, 1997; Ehlers & Clark, 2000; Taft et al., 2015). Although a substantial amount of research has been conducted in this area, most studies have used samples of either college students or military personnel and veterans with histories of combat-related trauma. In contrast, the current project sought to extend past research by employing a diverse community sample of adults at high risk for IPA to examine associations with trauma cognitions.

Trauma Cognitions and IPA

Cognitive models of the effects of trauma provide a basis for understanding negative reactions to trauma exposure (Berkowitz, 1993; Ehlers & Clark, 2000). One model proposes that individual differences in the appraisal of trauma and its consequences facilitate heightened perceptions of threat (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). Trauma appraisals include an overgeneralized sense of threat, which leads to interpreting normal activities as being dangerous, having an exaggerated sense of the probability of the occurrence of future traumatic events, and negative cognitions about others and the world (e.g., perceiving others as having violated one’s personal rules and treating one unfairly). The perception of threat subsequently triggers a variety of cognitive and emotional sequelae, including re-experiencing symptoms, anxiety, and arousal. In an effort to reduce the perceived threat and its associated distress, a set of behavioral, affective, and cognitive responses may be activated. However, these responses are often maladaptive and serve to maintain a cycle of threat perception and maladaptive response.

As noted above, the development of negative cognitions about the world is a key aversive outcome of trauma exposure (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). Negative cognitions that arise may take the form of viewing the world as a dangerous place, believing that people cannot be trusted, and feeling that one must always be on guard. Several empirically supported theories of interpersonal aggression suggest that such beliefs often lead to dysregulated emotions and increased anger and hostility, which in turn increase the likelihood of responding to a perceived threat in an aggressive manner (Beck, 1999; Berkowitz, 1993; Huesmann, 1998). One situation in which this may occur is in response to a perceived threat from an intimate partner. We are aware of only one study that directly examined the relationship between posttraumatic negative cognitions about the world and IPA perpetration (Marshall, Robinson, & Azar, 2011). This study, conducted with a sample of university students, found that negative cognitions about the world were directly associated with both physical and psychological IPA perpetration and that these relationships were mediated by anger misappraisal and emotion dysregulation. The current project sought to replicate and extend these findings by examining the impact of rumination on this mechanism in a high-risk, diverse community sample.

In line with Marshall and colleagues’ (2011) findings presented above, it has been theorized that hostility and anger are likely outcomes of harboring negative cognitions about the world, particularly as a response to perceived slights from others (Berkowitz, 1993; Ehlers & Clark, 2000). Hostility is a cognitive construct comprised of enduring cognitions that involve negative interpretations of the environment. Hostility on its own may not have a negative impact on others, but when coupled with the closely related affective state of anger, it can lead to a heightened risk of aggression (e.g., IPA; Buss, 1961). Research indicates that a history of exposure to a potentially traumatic event is associated with greater levels of hostility and violence (Jakupcak & Tull, 2005). Other studies have found maritally violent men to score higher on hostility inventories than non-violent or less violent men (e.g., Maiuro, Cahn, Vitaliano, Wagner, & Zegree, 1988). Together, these findings suggest that trauma exposure may put one at risk for becoming more hostile, which in turn may lead to heightened risk of perpetrating IPA.

Ample research has also illustrated a direct link between anger and IPA perpetration (Eckhardt, Barbour, & Stuart, 1997; Norlander & Eckhardt, 2005). A recent meta-analysis of 61 studies revealed a moderate association between trait anger and aggression, which increased with aggression severity (Birkley & Eckhardt, 2015). In studies examining anger expression, or the tendency to express anger through verbal or physical aggression, maritally violent men have been found to score higher on measures of maladaptive anger expression and to be more likely to engage in outward anger expression during an anger arousing situation compared to nonviolent men (Barbour, Eckhardt, Davison, & Kassinove, 1998; Eckhardt, Jamison, & Watts, 2002). Several studies have also found that daily self-reported intense anger predicted daily IPA perpetration, providing further evidence of a temporal relationship between proximal anger and IPA (Crane & Testa, 2014; Elkins, Moore, McNulty, Kivisto, & Handsel, 2013). Additionally, anger has been shown to mediate not only the relationship between negative cognitions about the world and IPA (Marshall et al., 2011), but also the relationship between rumination and general aggression (Borders, Barnwell, & Earleywine, 2007).

Rumination: A Potential Moderator of This Mechanism

Rumination, or neurotic “self-attentiveness motivated by perceived threats, losses, or injustices to the self” (Trapnell & Campbell, 1999; p. 297), is another dysfunctional cognitive process that may help explain the association between posttraumatic negative cognitions about the world and IPA. Rumination has been conceptualized as a maladaptive cognitive processing style that has the potential to strengthen problematic appraisals of a traumatic event and to trigger re-experiencing symptoms (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). Thus, rumination may focus one’s attention on perceived injustices, potentially strengthening the detrimental effects of negative cognitions about the world. This narrowing of attention has the potential to lead to increased hostility and anger towards others, which could subsequently heighten one’s risk of IPA perpetration. In a laboratory-based study of undergraduate students, self-focused rumination was associated with increased aggressive behavior, with this relationship mediated by angry affect and self-critical negative affect (Pederson et al., 2011). Studies also indicate that the joint effects of rumination and heavy alcohol consumption facilitate particularly high levels of aggression (Borders et al., 2007; Borders & Giancola, 2011). Together, these studies support the conclusion that dispositional rumination, or the tendency to dwell on past events or regrets, facilitates aggression by narrowing attention onto angry affect and hostile thoughts. Consistent with this conclusion, dispositional rumination may increase risk for IPA perpetration among individuals with previous trauma exposure by narrowing their attention onto distorted cognitions about the world which in turn leads to increased anger and hostility. As a result, they are more likely to react aggressively toward perceived threats from partners.

The Current Study

Previous research has established a strong link between trauma and IPA perpetration. However, there are gaps in the literature regarding the putative mechanism which explains this effect. In addition, a large proportion of studies that have examined the trauma-IPA relationship have employed either undergraduate or military samples. In the proposed study, we expanded on previous research by examining the mediating effect of anger and hostility on the relationship between posttraumatic negative cognitions about the world and IPA perpetration in a high-risk community sample with a history of IPA victimization. More specifically, we tested the following hypotheses:

We expected negative cognitions about the world to be positively associated with greater anger and hostility.

We hypothesized that anger and hostility would be positively associated with frequency of IPA perpetration.

We hypothesized that rumination would moderate the association between negative cognitions about the world and anger/hostility, such that the association between negative cognitions and anger/hostility would be greater for those high in rumination than for those low in rumination.

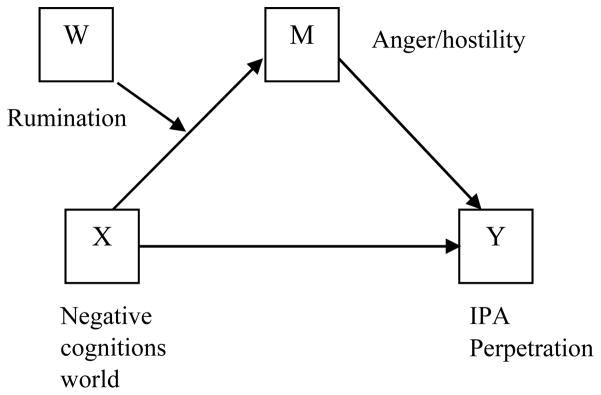

We expected the indirect effect of negative cognitions on IPA perpetration through anger and hostility to be moderated by rumination. Specifically, we hypothesized that the indirect effect of negative cognitions about the world on frequency of IPA perpetration via anger and hostility would be stronger among participants high in trait rumination relative to participants low in trait rumination (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of hypothesized moderated mediation

Method

The distinct set of hypotheses tested herein used data that were drawn from a larger investigation on the effects of acute alcohol intoxication and IPA. Thus, couples were required to meet eligibility criteria for an alcohol administration study (see below). The present hypotheses are novel, and the analytic plan was developed specifically to address these aims.

Participants and Recruitment

Intimate couples were recruited from two United States metropolitan areas through print and online advertisements. Couples were screened individually by telephone to establish initial eligibility, which was then verified by an in-person laboratory assessment. To be eligible, couples needed to have been dating for at least one month and both partners needed to be at least 21 years old and identify English as their native language. At least one partner was required to meet two additional criteria: (1) report consumption of an average of at least five (for men) or four (for women) alcoholic beverages at least twice per month during the past year; (2) report perpetrating psychological or physical IPA toward their current partner on the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). Couples were excluded from the study if either partner reported a serious head injury, a medical condition that rendered them unable to drink alcohol, or a desire to seek treatment for alcohol use.

Six hundred and seventeen couples (N = 1,234) were deemed initially eligible by the telephone screen and were brought into the laboratory for a more comprehensive assessment. Three hundred and twenty-one couples (n = 642) continued to meet inclusion criteria. Of the couples who completed the laboratory assessment, four same-sex couples (n = 8) were excluded, 93 couples (n = 186) were excluded for failing to meet minimum drinking requirements, 65 couples (n = 130) were excluded for endorsing severe physical IPA within their relationship, 10 couples (n = 20) were excluded for not endorsing any IPA, 99 couples (n = 198) were excluded for failing to meet both alcohol and IPA requirements, and 25 couples (n = 50) were excluded for failing to meet other eligibility requirements (e.g., physical or mental health problems, desire to seek treatment, weight). Additionally, 44 couples were excluded for not endorsing bidirectional IPA. An additional 6 couples were excluded because they failed to provide responses to items on the trauma cognitions and anger/hostility measures. For the purposes of the current study, we sought to examine how an individual’s own cognitive and affective processes, regardless of their partners’ behaviors, predicted their frequency of perpetrating IPA. Thus, only the member from each couple who reported greater frequency of IPA perpetration was included in the analyses for the current project. This resulted in a final sample of 271 heterosexual participants (see Table 1). The average relationship length was 53.86 (SD = 57.41) months. Most participants were not married and either non-cohabitating (40.2%) or cohabitating (37.0%), whereas only 13.8% were married. Most participants self-identified as African American (61.9%) or Caucasian (27.5%); 5.9% identified as Hispanic or Latino/a. Participants had a median income range of $10,000 to $20,000 per year. The relatively low income of participants in this study is a unique aspect of this sample, particularly compared to samples of college students who typically report family incomes falling within the middle to upper-middle classes. This study was approved by each university’s Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Descriptive Statistics

| %/M (SD) (N = 271) | |

|---|---|

| Female | 36.6 |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 40.2 |

| Married | 13.8 |

| Unmarried, living with partner | 37.0 |

| Divorced/Widowed | 6.2 |

| Separated | 2.9 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White/Caucasian | 27.5 |

| Black/African-American | 61.9 |

| Other/Multiracial | 10.6 |

| Hispanic | 5.9 |

| Annual Income | |

| <$10k | 33.5 |

| $10–20k | 25.8 |

| $20–30k | 17.1 |

| $30–40k | 10.2 |

| >$40k | 13.4 |

| Age | 33.14 (10.73) |

| Length of Relationship (months) | 53.86 (57.41) |

| Years of Education | 13.83 (2.98) |

| Negative Cognitions about the World | 27.48 (9.89) |

| Rumination | 34.91 (8.31) |

| Anger | 14.72 (5.04) |

| Hostility | 18.04 (6.64) |

| Physical IPA Perpetration | 7.67 (12.53) |

| Psychological IPA Perpetration | 25.38 (25.85) |

| Total IPA Perpetration | 33.05 (35.52) |

| IPA Victimization | 16.05 (21.00) |

Note. M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation

Measures

Negative cognitions about the world

The Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI; Foa, Ehlers, Clark, Tolin, & Orsillo, 1999) is a 36-item measure of maladaptive posttraumatic cognitions. The PTCI is comprised of three subscales that assess self-blame, negative cognitions about the self, and negative cognitions about the world following a traumatic event. In the current project, we were interested in how negative cognitions regarding others were related to aggression against one’s partner. Thus, we focused only on the 7-item subscale measuring negative cognitions about the world. Instructions for this measure require participants to rate the extent to which they agree or disagree with a number of statements that reflect possible responses to traumatic events. Response options for each item range from 1 (“totally disagree”) to 7 (“totally agree”) for a total score ranging from 7 to 49, with higher scores indicating stronger negative posttraumatic cognitions. A sample item from this subscale includes “People can’t be trusted.” The PTCI exhibits good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity with other measures of posttraumatic stress disorder (Foa et al., 1999). The internal consistency of the negative cognitions about the world subscale in the current sample was α = .83.

Rumination

Dispositional rumination was measured by the Rumination-Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ; Trapnell & Campbell, 1999). The RRQ consists of two 12-item subscales measuring rumination and reflection. The response format consists of a 5-point Likert scale, in which participants endorse their level of agreement with each item from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The rumination subscale is scored by summing the responses for each of the twelve items, with higher scores indicating higher levels of rumination. An example of an item on the rumination subscale is “I always seem to be rehashing in my mind recent things I’ve said or done.” This subscale has been found to be correlated with neuroticism, and has shown demonstrated high internal reliability and good convergent and discriminant validity (Trapnell & Campbell, 1999). The internal consistency of this scale in the current sample was α = .82.

Anger and hostility

The Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ; Buss & Perry, 1992) is a 29-item measure consisting of four subscales that measure the behavioral, cognitive, and affective components of aggressivity. Given our interest in examining both dysfunctional cognitions and dysregulated emotions, we aimed to capture both the cognitive and affective components of dispositional aggressivity. The Anger subscale consists of 7 items and measures trait anger, or the tendency to become angry more frequently and intensely than those low in trait anger (e.g., “I sometimes feel like a powder keg ready to explode”). The Hostility subscale consists of 8 items and measures the attitudinal or cognitive construct comprised of enduring cognitions that involve negative interpretations of the environment (e.g., “I wonder why sometimes I feel so bitter about things”). Response options for each item range from ‘1’ (“Extremely uncharacteristic of me”) to ‘5’ (“Extremely characteristic of me”). Each subscale is scored by summing the responses for each item, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anger and hostility. The BPAQ has been used widely and has demonstrated good reliability and internal consistency (Buss & Perry, 1992). The internal consistency of the anger and hostility subscales in the current sample were α = .74 and α = .82, respectively.

Initial analyses found a strong association between the Anger and Hostility subscales (r = .66, p < .01), suggesting that Anger may share considerable variance and conceptual overlap with Hostility. We formed a composite score by creating z-scores for each subscale and then summing them together. The composite score yielded a more comprehensive assessment of this multidimensional construct and similar approaches have been used in past studies of IPA (Leonard & Senchak, 1996). We repeated the analyses with Anger and Hostility considered separately and obtained similar results. Therefore, we only report the analyses using the composite Anger/Hostility score.

IPA

IPA perpetration was measured by the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996). The CTS2 is a 78-item scale that provides measures of physical, psychological, and sexual aggression perpetration and victimization within one’s intimate relationship as well as the use of negotiation and reasoning to deal with relationship conflicts. In the present study, we used the 5-item minor physical and 8-item psychological/verbal IPA perpetration subscales to examine frequency of perpetration within the past year. One item from the physical IPA subscale is “Have you thrown something at your partner that could hurt?” An example item from the psychological IPA subscale is “Have you shouted or yelled at your partner?” The CTS2 is a widely used instrument and has shown strong internal consistency and evidence of construct and discriminant validity (Straus et al., 1996).

Response options ranged from 0 (never in the past year) to 6 (more than twenty times in the past year) for each item. Three response options included a frequency range (i.e., 3 = 3–5 times in the past year, 4 = 6–10 times, 5 = 11–20 times), and we recoded these responses to reflect the midpoint of each range. We coded the response option “more than twenty times in the past year” as 25. Thus, possible sum scores for total IPA perpetration ranged from 0 to 325. In order to minimize the effect of underreporting, we calculated the total perpetration score by calculating maximum scores based on the highest report from either partner. Total perpetration scores obtained by the current sample ranged from 1 to 273. Physical perpetration scores ranged from 0 to 114, while psychological perpetration scores ranged from 1 to 159.

Procedures

Individuals who participated in the laboratory session completed a battery of self-report questionnaires assessing a number of behaviors and attitudes, including posttraumatic cognitions, rumination, anger, hostility, and IPA. They were then scheduled to return for a second laboratory session, after which they were debriefed and compensated for their time. The current project includes data from the first session only.

Analytic Approach

In order to test our hypothesized model of moderated mediation, we conducted data analyses using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013) for SPSS 23. The conceptual model for this analysis is presented in Figure 1. The PROCESS modeling technique produces an index of moderated mediation, which is the slope of the line reflecting the association between the moderator and the indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable through the mediator. This index has been established as the gold standard for estimating moderated mediation (Hayes, 2015). PROCESS uses an ordinary least squares or logistic regression-based path analytic framework for estimating direct and indirect effects. PROCESS does not assume that the data have a normal distribution and accounts for skewed distributions by using a bootstrapping procedure (5,000 bootstrap samples) to determine bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals. Each predictor variable was kept in its continuous form and was centered by subtracting the sample mean of that variable from each raw score. An interaction term was created using the centered independent variable (negative cognitions) and moderator (rumination). High and low values of the moderator that are used in the PROCESS moderation analysis are automatically generated by adding and subtracting one standard deviation from the centered sample mean of that variable.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive analyses and bivariate correlations were conducted in SPSS 23 and can be found in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Negative cognitions and rumination were both significantly positively correlated with the mediator, anger/hostility. All predictor variables (i.e., negative cognitions, rumination, anger/hostility) were significantly correlated with the dependent variable, IPA perpetration. Separate analyses were initially conducted with physical and psychological IPA perpetration as the dependent variables. Results from each analysis were virtually identical, so the two subscales were combined into a total IPA perpetration composite score for final analyses. T-tests revealed no significant gender differences for any of the variables, so we conducted all analyses with the full sample. However, it is notable that the male partner reported more frequent use of IPA than the female partner in 65% of the couples included in the present analyses.

Table 2.

Correlations among IPA Perpetration, Anger/Hostility, Rumination, and Negative Cognitions about the World

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Negative Cognitions | - | ||

| 2. Rumination | .279*** | - | |

| 3. Anger/Hostility | .485*** | .497*** | - |

| 4. IPA perpetration | .221*** | .265*** | .320*** |

Note.

p < .001

Simple mediation analysis

The first analysis tested the indirect effect of negative cognitions about the world (IV) on IPA perpetration (DV) through anger/hostility (mediator). The overall model was significant (F(2, 268) = 4.985, R2 = .036, p < .01). Results revealed significant effects of negative cognitions on anger/hostility (B = .090, SE = .010, 95% CI [.070, .109], p < .001; mean square error [MSE] = 2.558), and of anger/hostility on IPA perpetration (B = 3.156, SE = 1.296, 95% CI [.604, 5.708], p < .05; MSE = 1155.956), thus providing support for hypotheses 1 and 2. The direct effect of negative cognitions on IPA perpetration was not significant (B = .138, SE = .239, 95% CI [-.331, .609], p = .565). The indirect effect of negative cognitions on IPA perpetration through anger/hostility was significant (B = .283, SE = .130, 95% CI [.031, .549]), providing evidence of the hypothesized mediating effect.

Moderation analysis

The second analysis tested the moderating effect of rumination (moderator) on the effect of negative cognitions (IV) on anger/hostility (mediator). The overall model was significant (F(3, 267) = 60.513, p < .001, R2 = .405; MSE = 2.007). The main effects of negative cognitions (B = .067, SE = .009, 95% CI [.050, .085], p < .001) and rumination (B = .086, SE = .011, 95% CI [.065, .108], p < .001) were significant. The interaction term was also significant (B = .004, SE = .001, 95% CI [.002, .006], p < .001, ΔR2 = .028). These results provide evidence for a moderating effect of rumination on the relationship between negative cognitions and anger/hostility. Furthermore, the effect of negative cognitions on anger/hostility increased in strength from low (−1 SD; B = .038, SE = .013, 95% CI [.013, .063]) to moderate (Mean; B = .068, SE = .009, 95% CI [.050, .086]) to high (+1 SD; B = .098, SE = .012, 95% CI [.074, .121] levels of rumination, providing support for our third hypothesis.

Moderated mediation analysis

The index of moderated mediation, or the slope of the line relating the indirect effect to the moderator, was significant (B = .011, SE = .007, 95% CI [.001, .029]). More specifically, results indicated that the indirect effect of negative cognitions on IPA perpetration through anger/hostility strengthened as rumination increased from low (−1 SD; B = .120, SE = .070, 95% CI [.018, .303]) to moderate (Mean; B = .214, SE = .102, 95% CI [.032, .426]) to high (+1 SD; B = .308, SE = .149, 95% CI [.049, .636]) levels. Therefore, although the indirect effect of negative cognitions on IPA is significant at all levels of rumination, the index of moderated mediation indicates that these effects are significantly different from each other, thus providing support for our fourth hypothesis.

Discussion

The present study supports a theory-based pathway in which maladaptive anger and hostility mediate the association between negative posttraumatic cognitions and IPA perpetration more so for individuals high in rumination than individuals low in rumination. Findings suggest that rumination may increase the likelihood that individuals who already harbor negative cognitions about the world focus even more heavily on perceived slights and injustices from their partner, leading them to interpret conflict situations negatively. This attentional bias may have resulted in increased hostility and anger towards the partner, which in turn may increase the risk of perpetrating IPA. These results shed light on the trauma-IPA relationship and help to clarify one mechanism through which consequences of trauma may interact to predict IPA perpetration.

Limitations

Several limitations of the current study merit discussion. First, the measures employed were retrospective self-report questionnaires and thus are subject to selective reporting and memory biases. This may have led to underreporting of IPA perpetration frequency and aggressive tendencies. The use of only self-report measures in this study also poses the potential risk of shared method variance. While all participants experienced physical and/or psychological IPA victimization within the past year, we do not know whether these incidents were perceived as traumatic and thus cannot make a conclusive determination that all participants had experienced a Criterion A trauma. In addition, the cross-sectional nature of this study hinders our ability to make temporal conclusions about the events implicated in the tested pathway. Event-based methods are needed to address this limitation. However, past research has shown that personality traits are strongly linked with transient mood states and have strong predictive power in acute conflict situations (Rusting, 1998). Thus, although we measured trait variables in the current study, we have reason to believe that they still offer valuable insight into the contextual mechanisms involved in acute incidents of anger-related IPA perpetration. Finally, given the unique aspects of our sample (e.g., relatively low SES) and the specific inclusion criteria for the current study (e.g., heavy alcohol users, heterosexual couples), the present findings may not generalize to other populations (e.g., same-sex couples, upper SES).

Research Implications

The current findings are consistent with past research. Previous studies have shown a direct link between trauma exposure and IPA perpetration (Bell & Orcutt, 2009; Maguire et al., 2015; Taft et al., 2011). However, the processes underlying this connection have not been studied as widely. In their cognitive model of trauma, Ehlers and Clark (2000) theorized that cognitive distortions such as negative cognitions about the world and rumination, as well as emotion dysregulation (e.g., maladaptive anger response), may help to explain the relationship between trauma and aggression. Although aspects of this model have been empirically tested (e.g., Owens, Chard, & Cox, 2008; Sippel & Marshall, 2011), little research has examined IPA perpetration as a potential aggression-related outcome of trauma cognitions. The only study of which we are aware examined the effect of negative posttraumatic cognitions about the world on IPA perpetration a sample of university students (Marshall et al., 2011). Consistent with that study, our results found a positive association between negative posttraumatic cognitions about the world and IPA perpetration. The present findings are also consistent with past research that has found a link between anger and IPA. Anger has been demonstrated to mediate the separate effects of negative cognitions and rumination on IPA perpetration (Borders et al., 2007; Marshall et al., 2011). We found that both negative cognitions and rumination significantly predicted maladaptive anger and hostility and that anger and hostility subsequently mediated the relationship between negative cognitions and IPA perpetration, particularly for those high in rumination. Thus, the current study provides new data regarding a potential mechanism that may explain the relation between trauma exposure and IPA.

The current study helps to fill a gap in the literature by testing cognitive models of trauma and IPA in a high-risk, diverse, community sample of adults who have experienced IPA victimization. Additionally, this is the first study of which we are aware to examine the interaction among two types of maladaptive cognitive processes (i.e., negative cognitions about the world and rumination) as well as anger and hostility in predicting IPA perpetration.

Future research is needed to address the limitations of the current study and to examine the roles that other individual, social, and trauma-related factors play in the trauma-IPA relationship. Future studies should include measures of trauma history and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptomatology. Assessment of trauma-specific anger and ruminative outcomes is needed to establish more conclusive relationships among these cognitive processes and IPA perpetration. Conducting research with clinical populations with more severe PTSD symptoms and interpersonal problems may help to better elucidate these relationships. Additionally, the use of experimental methods could allow for the identification of causal relationships among these variables. Finally, relative to heterosexual couples, same-sex couples face unique IPA-promoting stressors, such as sexual minority stress (Edwards, Sylaska, & Neal, 2015; Lewis, Milletich, Keley, & Woody, 2012). That stated, it is clear that many variables are associated with IPV in both heterosexual and same-sex couples (Edwards et al., 2015). These variables include psychological distress, child abuse, and exposure to IPV as a child – all of which may contribute to trauma-related cognitive and affective processes. These data suggest that the present findings may generalize to same-sex couples. However, future research is clearly needed to support this hypothesis.

Clinical and Policy Implications

The present findings suggest that dispositional rumination and maladaptive anger and hostility may be key factors in the trauma-IPA association. Thus, future intervention programs for trauma-exposed individuals may benefit from targeting these maladaptive cognitive and affective processes, particularly rumination which was found to exacerbate the effects of trauma cognitions on anger and hostility. These processes may also be useful targets in IPA intervention and prevention programs. Given the high overlap between trauma and IPA perpetration (Bell & Orcutt, 2009; Taft et al., 2011), it is likely that some individuals attending IPA intervention or prevention programs have experienced trauma during their lifetimes and could benefit from techniques that target maladaptive hostile and ruminative cognitions (for a review, see Murphy & Eckhardt, 2005). In fact, a recent study of men receiving treatment for IPA perpetration found that a majority (77.5%) had experienced a traumatic event during their lifetime, suggesting a need to incorporate both routine screening for trauma exposure as well as trauma-related treatment components into IPA interventions (Semiatin, Torres, LaMotte, Portnoy, & Murphy, 2017).

Taft and colleagues’ Strength at Home program, a 12-week cognitive behavioral group therapy, has shown efficacy in reducing IPA perpetration and intimate relationship conflict among trauma-exposed military veterans (Taft et al., 2016). This manualized intervention targets maladaptive cognitive and affective processes and focuses on enhancing skills such as anger regulation and assertive communication. The Strength at Home program aims to help clients understand the impact of trauma on their relationships and to guide them in strengthening their coping mechanisms. Future research should focus on extending this program to non-military samples.

The current study provides a unique analysis of several trauma-related cognitive and affective processes and their associations with IPA perpetration. Present findings suggest that for high ruminators, maladaptive anger and hostility mediate the relationship between negative cognitions about the world and IPA perpetration. Additional work is needed to clarify the temporal ordering of these processes and to test the proposed model in a clinical population. It is hoped that future research will continue to investigate the cumulative impact of trauma-related outcomes in order to better inform the development of IPA intervention programs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant 1R01AA020578 awarded to the 2nd and 4th authors.

Contributor Information

Andrea A. Massa, Purdue University, Department of Psychological Sciences, West Lafayette, IN

Christopher I. Eckhardt, Purdue University, Department of Psychological Sciences, West Lafayette, IN

Joel G. Sprunger, Purdue University, Department of Psychological Sciences, West Lafayette, IN

Dominic J. Parrott, Georgia State University, Department of Psychology, Atlanta, GA

Olivia S. Subramani, Georgia State University, Department of Psychology, Atlanta, GA

References

- Barbour KA, Eckhardt CI, Davison GC, Kassinove H. The experience and expression of anger in maritally violent and maritally discordant-nonviolent men. Behavior Therapy. 1998;29:173–191. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(98)80001-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Prisoners of hate: The cognitive basis of anger, hostility, and violence. New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bell KM, Orcutt HK. Posttraumatic stress disorder and male-perpetrated intimate partner violence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302(5):562–564. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L. Towards a general theory of anger and emotional aggression: Implications of the cognitive-neoassociationistic perspective for the analysis of anger and other emotions. In: Wyer RS, Srull TK, editors. Perspectives on anger and emotion. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1993. pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Birkley EL, Eckhardt CI. Anger, hostility, internalizing negative emotions, and intimate partner violence perpetration: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;37:40–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Chen J, Stevens MR. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. Atlanta, GA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Borders A, Barnwell SS, Earleywine M. Alcohol-aggression expectancies and dispositional rumination moderate the effect of alcohol consumption on alcohol-related aggression and hostility. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33:327–338. doi: 10.1002/ab.20187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borders A, Giancola PR. Trait and state hostile rumination facilitate alcohol-related aggression. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:545–554. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH. The psychology of aggression. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Perry M. The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63(3):452–459. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemtob CM, Novaco RW, Hamada RS, Gross DM, Smith G. Anger regulation deficits in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10(1):17–36. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490100104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane CA, Testa M. Daily associations among anger experience and intimate partner aggression within aggressive and nonaggressive community couples. Emotion. 2014;14(5):985–994. doi: 10.1037/a0036884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CI, Barbour KA, Stuart GL. Anger and hostility in maritally violent men: Conceptual distinctions, measurement issues, and literature review. Clinical Psychology Review. 1997;17(4):333–358. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(96)00003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CI, Jamison TR, Watts K. Anger experience and expression among male dating violence perpetrators during anger arousal. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17(10):1102–114. doi: 10.1177/088626002236662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Sylaska KM, Neal AM. Intimate partner violence among sexual minority populations: A critical review of the literature and agenda for future research. Psychology of Violence. 2015;5:112–121. doi: 10.1037/a0038656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Clark DM. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:319–345. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins SR, Moore TM, McNulty JK, Kivisto AJ, Handsel VA. Electronic daily assessment of the temporal association between proximal anger and intimate partner violence perpetration. Psychology of Violence. 2013;3(1):100–113. doi: 10.1037/a0029927. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Ehlers A, Clark DM, Tolin DF, Orsillo SM. The Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (PTCI): Development and validation. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11(3):303–314. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.11.3.303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2015;50:1–22. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR. The role of social information processing and cognitive schema in the acquisition and maintenance of habitual aggressive behavior. In: Russell RG, Donnerstein E, editors. Human aggression: Theories, research, and implications for social policy. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 73–109. [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Tull MT. Effects of trauma exposure on anger, aggression, and violence in a nonclinical sample of men. Violence and Victims. 2005;20(5):589–599. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.2005.20.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Senchack M. Prospective prediction of husband marital aggression within newlywed couples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105(3):369–380. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.105.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ, Milletich RJ, Kelley ML, Woody A. Minority stress, substance use, and intimate partner violence among sexual minority women. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2012;17:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2012.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire E, Macdonald A, Krill S, Holowka DW, Marx BP, Woodward H, … Taft CT. Examining trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in court-mandated intimate partner violence perpetrators. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2015;7(5):473–478. doi: 10.1037/a0039253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiuro RD, Cahn TS, Vitaliano PP, Wagner BC, Zegree JB. Anger, hostility, and depression in domestically violent versus generally assaultive men and nonviolent control subjects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(1):17–23. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall AD, Robinson LR, Azar ST. Cognitive and emotional contributors to intimate partner violence perpetration following trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2011;24(5):586–590. doi: 10.1002/jts.20681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Eckhardt CI. Treating the abusive partner: An individualized cognitive-behavioral approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Costs of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Norlander B, Eckhardt CI. Anger, hostility, and male perpetrators of intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:119–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens GR, Chard KM, Cox TA. The relationship between maladaptive cognitions, anger expression, and posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans in residential treatment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma. 2008;17(4):439–452. doi: 10.1080/10926770802473908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott DJ, Drobes DJ, Saladin ME, Coffey SF, Dansky BS. Perpetration of partner violence: effects of cocaine and alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28(9):1587–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson WC, Denson TF, Goss RJ, Vasquez EA, Kelley NJ, Miller N. The impact of rumination on aggressive thoughts, feelings, arousal, and behaviour. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2011;50:281–301. doi: 10.1348/014466610X515696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusting CL. Personality, mood, and cognitive processing of emotional information: Three conceptual frameworks. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;124(2):165–196. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semiatin JN, Torres S, LaMotte AD, Portnoy GA, Murphy CM. Trauma exposure, PTSD symptoms, and presenting clinical problems among male perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Psychology of Violence. 2017;7(1):91–100. doi: 10.1037/vio0000041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sippel LM, Marshall AD. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, intimate partner violence perpetration, and the mediating role of shame processing bias. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;25(7):903–910. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby S, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman D. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2) Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Macdonald A, Creech SK, Monson CM, Murphy CM. A randomized controlled clinical trial of the Strength at Home Men’s Program for partner violence in military veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2016;77(9):1168–1175. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Watkins LE, Stafford J, Street AE, Monson CM. Posttraumatic stress disorder and intimate relationship problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79(1):22–33. doi: 10.1037/a0022196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Weatherill RP, Panuzio Scott J, Thomas SA, Kang HK, Eckhardt CI. Social information processing in anger expression and partner violence in returning U.S. veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2015;28:314–321. doi: 10.1002/jts.22017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell PD, Campbell JD. Private self-consciousness and the five-factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76(2):284–304. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.76.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Understanding and addressing violence against women: Intimate partner violence. 2012 Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77432/1/WHO_RHR_12.36_eng.pdf.