Abstract

Nucleic acid sensing pathways have likely evolved as part of a broad pathogen sensing strategy intended to discriminate infectious agents and initiate appropriate innate and adaptive controls. However, in the absence of infectious agents, nucleic acid sensing pathways have been shown to play positive and negative roles in regulating tumorigenesis, tumor progression and metastatic spread. Understanding the normal biology behind these pathways and how they are regulated in malignant cells and in the tumor immune environment can help us devise strategies to exploit nucleic acid sensing to manipulate anti-cancer immunity.

Keywords: Innate immunity, STING, RIG-I, TLR, cancer, tumor, vaccine

Introduction

Cancer arises from dysregulated expansion of our own cells due to an accumulation of gene mutations that divert cells from their normal function. The progressive nature of tumorigenesis means that at various points, cancer cells have an array of mutations but are not yet malignant, and the final malignant clone may arise out of a premalignant state that may have been present for a prolonged period of time (Fearon and Vogelstein, 1990). Recently, with the rapid acceptance of immunotherapy, we have seen clinical validation of the power of the immune system to recognize and control tumors via targeting of mutated genes as antigenic targets (Tran et al., 2017). As an example, these antigenic targets can include mutated K-ras (Tran et al., 2016), which is considered an early common mutation in tumorigenesis (Fearon and Vogelstein, 1990). In this case, these data imply that there is an extended interaction between mutated cancer cells and a host immune system that has the capacity to recognize these mutations as antigens, yet cancer continues to progress and acquire further mutations until it develops into symptomatic disease.

This disconnect between the capacity of the immune system to recognize antigens and whether they actually do so is well known in immunology. Antigens are not sufficient to initiate immune responses. Immunology is all about the involvement of the right cells, in the right places, with the right signals to support immunity. While we continue to discover novel immune regulatory molecules, pathways and cells, certain features remain true. One truism is the core principle of antigen plus adjuvant being critical to initiate immune responses. This principal explains why systemic application of antigenic peptides alone results in antigen specific tolerance and eventual deletion of antigen specific T cells (Liblau et al., 1996). However, systemic application of a virus expressing this antigenic peptide or the peptide pulsed on an activated dendritic cell results in powerful antigen-specific responses. The difference lies in the context in which the antigen-specific T cells see their antigens, which is dominated by the influences of the cells that present the antigen, the adjuvant signals that influence the context of antigen presentation and the specific molecular interactions between antigen presenting cells and T cells. The role of nucleic acids in activating the immune system has been of interest to scientists ever since Isaacs et al. discovered that mouse cells infected with chicken nucleic acids produced interferons (Isaacs et al., 1963). As we will discuss, it is in this context that nucleic acid sensing mechanisms play a critical role in vaccination-based strategies to engender anti-cancer immunity.

In view of the capacity of immune cells to recognize and destroy cancer cells, it is now recognized that negative regulation of immune responses is a critical feature that allows mutated cells to develop into advanced malignancies (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). This requirement to suppress or control anti-cancer immunity is in addition to the positive role that inflammation can provide in driving tumorigenesis through constant remodeling of the epithelium (DeNardo et al., 2010). As we will discuss, nucleic acid sensors have been shown to influence tumorigenicity in animal models in part by regulating tumorigenic inflammation. These mechanisms remain influential throughout malignant progression, and as we will discuss, there are a range of autophagic and cell-death related processes that result in activation of nucleic acid sensors that activate inflammatory mechanisms to continuously remodel the tumor immune environment. However, the majority of the studies on nucleic acid sensing and cancer have focused on treatment of advanced malignancies. Here there are two dominant approaches. In the first, exogenous ligands for nucleic acid sensors are applied to tumors to activate inflammatory pathways in the tumor environment. In the second, treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy influence endogenous nucleic acid processing mechanisms to activate nucleic acid sensors in the tumor environment. We will discuss the current status of each of these interventions and how they likely impact control of tumors by immune mechanisms. A list of abbreviations used in this review is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Name |

|---|---|

| AIM2 | absent in melanoma 2 |

| ALR | AIM2-like receptors |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BER | Base excision repair |

| CDA | cyclic di-AMP |

| CDG | cyclic di-GMP |

| CDN | cyclic dinucleotide |

| cGAMP | cyclic GMP-AMP |

| cGAS | Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase |

| CLR | C-type lectin receptors |

| CpG | cytosine triphosphate deoxynucleotide followed by a guanine triphosphate deoxynucleotide with a phosphodiester link |

| CTLA4 - | cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 |

| DMBA | dimethylbenz[a]anthacene |

| DRibble | DriPs- and SLiPs-filled autophagosomes |

| DRiPs | defective ribosomal products |

| dsRNA | double stranded RNA |

| ERAdP | endoplasmic reticulum adaptor protein |

| GTP | Guanosine-5’-triphosphate |

| HNSCC | head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| HPV | human papilloma virus |

| HR | homologous recombination |

| IFN | interferon |

| IRF3 | interferon regulatory factor 3 |

| M1 macrophage | classically differentiated macrophage |

| M2 macrophage | Alternatively differentiated macrophage |

| MAVS | Mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein |

| MDA5 | Melanoma Differentiation-Associated protein 5 |

| MMR | mismatch repair |

| MyD88 | Myeloid differentiation primary response 88 |

| NAP | NF-κB-activating kinase associated protein |

| NER | nucleotide excision repair |

| NFkB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NHEJ | Non-homologous end joining |

| NLR | NOD-like receptor |

| NOD | Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein |

| ODN | oligodeoxynucleotides |

| PD1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| RECON | reductase controlling NF-κB |

| RIG-I | retinoic acid-inducible gene I |

| RLR | RIG-I- like receptors |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SHP | Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase |

| SLiPs | short-lived proteins |

| SSBR | Single-strand break repair |

| ssRNA | single stranded RNA |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| STING | Stimulator of Interferon Genes |

| TBK1 | TANK-binding kinase 1 |

| Th1 | Type 1 CD4 T helper cell |

| Th2 | Type 2 CD4 T helper cell |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| TRAF | TNF receptor associated factor |

| TRAM | TRIF-related adaptor molecule |

| Treg | regulatory CD4 T cell |

| TREX1 | Three prime repair exonuclease 1 |

| TRIF | TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

Overview of nucleic acid sensors

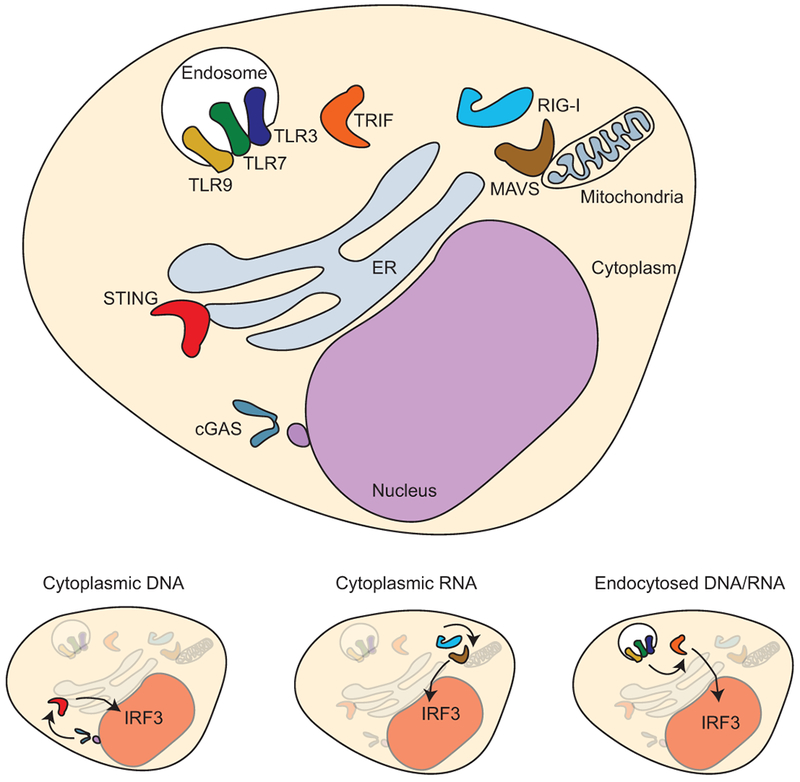

Nucleic acid sensing can be viewed as a subset of innate mechanisms to detect viral and bacterial infection. The prototypic innate sensors are the Toll-like receptors (TLR) (Medzhitov et al., 1997), a hugely influential family of molecules that activate inflammatory mechanisms in response to a wide variety of targets, from lipopolysaccharide (TLR4) to unmethylated CpG dinucleotides (TLR9) (reviewed in (Yin et al., 2015, Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2004)). In general, TLR share a common cytoplasmic signaling domain, thought to oligomerize and recruit adaptor proteins, which include critical signaling molecules such as MyD88, TRIF, and TRAM (O’Neill and Bowie, 2007). It is notable that TLRs that recognize nucleic acids – TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 – have an intracellular localization, predominantly within endosomal compartments (reviewed in (Blasius and Beutler, 2010)) (Figure 1). Broadly, TLR3 recognizes dsRNA, TLR7 recognizes ssRNA, and TLR9 recognizes unmethylated CpG links; however, each can recognize synthetic ligands that are important experimental cancer therapeutics. Not only do these receptors have an endosomal localization, but they also require endosomal acidification for activation (Häcker et al., 1998), which would correlate with destruction of internalized material and permit the host to distinguish an internalized infectious agent from inert material. While the signal transduction elicited by the TLRs that sense nucleic acids are not dissimilar from those sensing bacterial wall components – in that they utilize TIR domain-containing adaptors such as MyD88, TRIF, or TRAM – TLR3 is entirely Myd88-independent and only signals via TRIF (Hoebe et al., 2003). TRIF signaling is not unique to TLR3, but interestingly the other TLR members that use TRIF signaling may engage this pathway following receptor-mediated uptake and internalization of the TLR (Kagan et al., 2008, Tanimura et al., 2008). TRIF signal transduction differs somewhat from MyD88 signaling in that it recruits TRAF3 and TRAF6 to the signaling complex. While TRAF3 recruits TBK1 to the signaling complex and activates IRF3, TRAF6 recruits RIP-1 to the signaling complex, which activates TAK1 and subsequent NFκB and MAPK signaling (reviewed in (Kawasaki and Kawai, 2014)). TRAF6 also plays a role in Myd88 signaling, but Myd88-dependent signaling does not activate signal transduction pathways that lead to induction of IRF3 despite in some cases activating TBK1. The distinguishing mechanism is that IRF3 activation is dependent on it binding to the phosphorylated adaptor protein, in this case TRIF, allowing it to become phosphorylated by TBK1 (Liu et al., 2015). This mechanism is shared by the nucleic acid sensors MAVS and STING (Liu et al., 2015), such that one distinguishing feature of nucleic acid sensing pathways is IRF3 activation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Nucleic acid sensing mechanisms are dominantly located inside cells and consistently signal the presence of nucleic acids through activation and nuclear translocation of IRF3.

MAVS and STING represent relatively recent additions to the signal transduction pathways activated following nucleic acid sensing in cells. MAVS (also known as IPS-1, Cardif, and VISA) is an adaptor protein that links the cytoplasmic sensors of viral RNA RIG-I, MDA5 and LGP2 to signaling pathways (Kawai et al., 2005, Meylan et al., 2005, Xu et al., 2005). STING functions similarly as an adaptor protein linked to signals from the DNA sensor cGAS (Liu et al., 2015), though as discussed later this can be bypassed via STING innate sensing of exogenously derived cyclic dinucleotides. In each case, IRF3 is activated, forms a homodimer and translocates to the nucleus to activate gene transcription. IRF3 is one of a family of transcription factors that participate in IFN gene transcription (reviewed in (Honda et al., 2006)). IRF3 is most homologous to IRF7, and these proteins can form heterodimers. IRF3 is expressed at higher levels at baseline, is more stable than IRF7, and IRF3 homodimers are strong inducers of IFNβ gene transcription. By contrast IRF7 is induced by initial IRF3-induced gene expression and permits induction of a broader range of IFNα genes (Sato et al., 2000, Marié et al., 1998). In this way, continued detection of nucleic acids can generate a distinct early and late response in the vicinity of an infected cell.

While STING is commonly discussed as a nucleic acid sensor, it is not STING, but cGAS that directly binds DNA. Once cGAS binds to cytosolic double-stranded DNA, it catalyzes the formation of the second messenger molecule cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) from ATP and GTP (Gao et al., 2013, Sun et al., 2013, Wu et al., 2013). cGAMP is an endogenous high-affinity ligand for the adaptor protein STING (also known as MITA, MPYS, ERIS, and TMEM173) which allows innate activation to endogenous nucleic acids as well as following viral or bacterial infection (Ishikawa and Barber, 2011, Ishikawa et al., 2009). cGAMP binding to STING homodimers embedded within the endoplasmic reticulum triggers a conformational change in STING, activating the receptor. Activated STING translocates to punctate structures in the cytoplasm via interaction with autophagy-related proteins (Saitoh et al., 2009), where it interacts with TBK1 and forms a complex for the activation of NFκB and IRF3 (Abe and Barber, 2014, Tanaka and Chen, 2012). This phosphorylation allows NFκB and IRF3 to translocate to the nucleus and activate target genes associated with cytokine production. In this way, endogenous DNA can be sensed in the cytoplasm and cross-activate the STING-based pathway of bacterial and viral sensing. Following this cascade, STING is rapidly degraded, which prevents sustained cytokine production (Prabakaran et al., 2018). In addition, alternate STING isoforms have been described that can sequester functional STING molecules and decrease responsiveness to cGAMP (Wang et al., 2018a). In addition to STING, alternate sensors for cyclic dinucleotides has been described. ERAdP is activated in macrophages infected by cyclic dinucleotides released by Listeria monocytogenes and independently results in NFκB activation and production of inflammatory cytokines (Xia et al., 2018). ERAdP has specificity for CDA (cyclic di-AMP) rather than cGAMP (cyclic GMP-AMP) (Xia et al., 2018), which means it is not able to respond to endogenous DNA sensed by cGAS. Nevertheless, this remains a potent cellular sensor of infection, which plays a significant response following bacterial infection (Xia et al., 2018). RECON is another recently described sensor for cyclic dinucleotides, and at steady state negatively regulates NFκB activation (McFarland et al., 2017). Following binding of cyclic dinucleotides, its activity is suppressed, resulting in increased NFκB activity in cells (McFarland et al., 2017). RECON has a higher affinity for CDA than STING, but does not bind cGAMP (McFarland et al., 2017), meaning that like ERAdP, it will not be influenced by cGAS-mediated endogenous DNA sensing.

Cells of the immune system, as well as epithelial cells that come in contact with invading pathogens have evolved these nucleic acid sensing mechanisms to combat foreign material present or mis-localized within cells. Pattern recognition receptors and damage-associated molecular pattern receptors expressed by these cell types include STING, TLRs, RIG-I-like receptors, DDX41, IFI16, IFI204, DAI, and components of the inflammasome (e.g. NLRs and AIM2) that regulate secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, type I and type II interferon responses, and pyroptosis. As we have discussed in a prior review, TLR and nucleic acid sensors are not ubiquitously expressed, but immune cells, and in particular myeloid cells are extremely well provisioned with pattern recognition receptors and damage-associated molecular pattern sensors (Baird et al., 2017b). This would suggest that direct infection of myeloid cells would be required to detect infection, which doesn’t support the concept of non-immune cells as early direct sensors of infection. However, myeloid sensors can be sufficient in many circumstances, since for example, TLR3 need not be expressed in infected cells to initiate an immune response following viral infection (Schulz et al., 2005). Cross-presenting dendritic cells expressing TLR3 can recognize viral nucleic acids following phagocytosis of infected cell material, resulting in improved dendritic cell activation, cross presentation and expansion of antiviral T cells (Schulz et al., 2005). By contrast, STING is much more widely expressed, but still not ubiquitous. For example, we have found that STING is expressed in basal cells of the epithelium, but is lost on differentiation into squamous cells (Baird et al., 2017a). This pattern is conserved during tumorigenesis, such that HPV+ head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, which is thought to originate from infected basal cells, has a high level of STING expression, while HPV-head and neck squamous cell carcinoma does not express STING (Baird et al., 2017a). In the pancreas, in a small set of samples we found that pancreatic acinar cells poorly express STING, but normal ductal cells and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells both express STING (Baird et al., 2016). In colorectal carcinoma, STING is expressed in both normal colorectal cells and in most colorectal carcinoma cell lines tested, though these cells respond poorly to endogenous DNA due to lack of additional components of the sensory and signaling cascades including lack of cGAS (Xia et al., 2016a). Epigenetic modulation was able to restore functional responses to DNA in some, but not all cell types (Xia et al., 2016a). These data would suggest that when considering the capacity of cancer cells to directly respond to nucleic acids, we can expect a very divergent response according to the cell type of origin and any epigenetic regulation of critical sensing and signaling components.

In view of the critical role of nucleic acid sensing in the response to infection, it seems surprising that some of our cells appear poorly protected. In the skin, it perhaps makes sense that differentiated squamous cells lack STING, since these are generally post-replicative and undergoing increased keratinization to form the skin barrier layer. Viral infection of these cells may occur, but would be of little consequence. However, viral infection of the basal cells is required for initiation of productive infection, which depends on access to the basal layer via a wound (reviewed in (Stanley, 2012)). In this setting, it is logical to focus antiviral protection in the basal cell. Interestingly, Human papilloma virus (HPV) E7 has been shown to antagonize STING activation, as does Adenovirus E1A (Lau et al., 2015). These data seem to confirm a functional role for STING in critical cell types to control viral infection, but also demonstrate a mechanism by which viruses can evade direct detection.

RIG-I, MDA5 and LGP2 family members are thought to be expressed by most cells and act as cytoplasmic sensors of viral RNA (reviewed in (Loo and Gale, 2011)). Under normal conditions, RIG-I has a conformation that results in auto-inhibition; however, following ligand binding interaction with ubiquitin, the formation of a tetramer structure results, which functions to recruit and activate MAVS (Peisley et al., 2014). The ligand preference for RIG-I is dsRNA containing 5’ triphosphates and biphosphates (Goubau et al., 2014). These dsRNA forms are present in the nucleus of cells early following transcription, but are removed before entry into the cytoplasm. Following viral infection, these unmodified RNA structures can be present in the cytoplasm, and thereby trigger the RIG-I sensor and induce type I IFN production (Goubau et al., 2013).

An alternative sensors for cytoplasmic RNA share the helicase activities of RIG-I-like receptors and can initiate anti-viral immunity (Zhang et al., 2011). Study of this pathway demonstrated that there is overlap in the function of the nucleic acid sensors. While STING itself functions as a direct sensor for cyclic dinucleotides generated endogenously or from infectious agents (Zhang et al., 2013), it also functions as an adapter protein downstream of DDX41 (Zhang et al., 2011). Similarly STING has been shown to be critical for signaling downstream of DAI (Takaoka et al., 2007), IFI16 (Unterholzner et al., 2010) , and also RIG-I (Ishikawa and Barber, 2008). In addition, while RIG-I has a specificity for 5’ triphosphorylated (50ppp) ends, these ends are not sufficient to activate RIG-I (Schlee et al., 2009). Additional motifs in the RNA backbone are required for functional activation of RIG-I, suggesting that RIG-I can serve to integrate recognition of foreign RNA structures (Loo and Gale, 2011). These data suggest that while we have the opportunity to target pathways individually though synthetic ligands, the signaling cascade in cells may be designed to integrate complex inputs through common pathways, or distinguish patterns of infection to generate appropriate responses. Information on how these regulatory pathways work with one another may be critical to effectively initiate and control immune responses to cancer.

This information is especially relevant since to generate anti-cancer immunity we are generally seeking cytotoxic CD8 T cells differentiated in the presence of Th1-type CD4 T cell responses to recognize endogenous tumor antigens presented on MHC class I. Stating a goal such as this is critical, since our immune system integrates information about the nature of its target and generates appropriate responses. For example, current anti-viral vaccines work by generating neutralizing antibodies that function to remove free virions, not to kill infected cells. This has proved a limitation in the usefulness of vaccination once virus is resident in our cells. In the case of HPV, the HPV vaccine is an effective prophylactic, but does not influence HPV integrated into infected cells. Once inside cells, CD8 T cells are required to recognize viral antigens presented on MHC class I and kill infected targets. So the optimum vaccine to generate protective antibody responses may not be the optimum vaccine to generate cytotoxic T cell mediated immunity, just as the appropriate immune response to a parasite isn’t the same as that to a virus. While effective antibody responses and T cell responses can be linked (Hulett et al., 2018), the nucleic acid sensors with their cytoplasmic localization specifically tell the immune system that the infectious agents are inside cells. These signals can form part of specific response algorithms that generate immune responses that can kill infected cells. So, if our goal is to generate immune responses that can recognize cancer cells with mutated antigens, these are much more likely to be presented as peptides on MHC class I rather than form extracellular structures that can be recognized by antibodies. To generate immune responses like those that kill virally-infected cells to instead target cancer, we likely need to recapitulate in tumors the kinds of signals associated with viral infection.

DNA sensing in tumorigenesis versus treatment

Cells of the immune system, as well as epithelial cells that come in contact with invading pathogens have evolved these nucleic acid sensing mechanisms to combat foreign material present or mislocalized within cells. As discussed, pathogen-associated molecular pattern receptors and damage-associated molecular pattern receptors expressed by these cell types include STING, TLRs, RIG-I-like receptors, HMGB1, DDX41, IFI16, IFI204, DAI, and components of the inflammasome (e.g. NLRs and AIM2) that regulate secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, type I and type II interferon responses, and pyroptosis. While these nucleic acid sensors are critical for control and clearance of infections, we now appreciate that some of these processes also regulate tumorigenesis, as well as responses to cytotoxic therapies. As we will discuss, it is possible that cancer cells have a propensity to activate nucleic acid sensing mechanisms due to aberrant regulation of DNA repair and chromosome segregation, as well as necrotic release of nucleic acids into the tumor microenvironment, thereby regulating inflammation. This inflammation is generally discussed in the context of cancer treatment, but inflammation is also an extremely important feature of tumorigenesis.

As discussed above, the STING pathway is one of the primary mechanisms by which cytoplasmic DNA is sensed, either via direct activation by cGAS-generated cyclic dinucleotides (Zhang et al., 2013), or as an adapter protein downstream of DAI (Takaoka et al., 2007), RIG-I (Ishikawa and Barber, 2008), IFI16 (Unterholzner et al., 2010), and DDX41 (Zhang et al., 2011). Activation of STING results in activation of IRF3 and production of type I interferons, as well as activation of NF-κB and production of inflammatory mediators, such as TNFα (Ishikawa and Barber, 2008). Together, these downstream mediators function in maturation of APCs, as well as priming of antitumor CD8+ T cell responses (Woo et al., 2014) that underlie the efficacy of chemotherapy (Sistigu et al., 2014), radiation therapy (Burnette et al., 2011, Lim et al., 2014, Deng et al., 2014), and anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody immunotherapy (Wang et al., 2017a). Because activation of the STING pathway is important for type I interferon production and adaptive T cell responses, STING expression has been shown to correlate to clinical outcomes for several tumor types (reviewed in (He et al., 2017)). STING has been shown to be decreased or defective by various mechanisms in breast cancer (Bhatelia et al., 2014), colorectal cancer (Xia et al., 2016a), melanoma (Xia et al., 2016b), gastric cancer (Song et al., 2017), and hepatocellular carcinoma (Bu et al., 2016) and decrease in STING is associated with poor clinical outcomes. Similarly, several other nucleic acid sensors have also been shown to limit oncogenesis. Decreased RIG-I expression was observed in hepatocellular carcinoma and led to poor outcomes, including shorter survival (Hou et al., 2014). While these studies implicate loss of nucleic acid sensors as a mechanism of immune escape, there are reports that STING can also contribute to cancer-associated inflammation in the chronic setting. In the DMBA mouse model of skin carcinogenesis, DMBA treatment leads to DNA adduct formation and nucleosome leakage of DNA into the cytoplasm where it activates the STING pathway and its downstream inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα (Ahn et al., 2014). In the context of chronic inflammation in skin carcinogenesis, TNFα has been shown to be a promoting force in squamous cell carcinoma development (Schioppa et al., 2011), and loss of STING rendered mice resistant to carcinogenesis (Ahn et al., 2014). As we will discuss, chromosomal instability is a common feature of tumors that results in production of micronuclei that easily rupture, and as we will discuss, this can release DNA into the cytosol (Hatch et al., 2013), thereby activating the cGAS-STING pathway (Bakhoum et al., 2018). However, in patients with tumors that have high chromosomal instability, instead of activating type I interferon and NF-κB signaling, a proinflammatory, non-canonical NF-κB signaling pathway can be activated and result in expression of genes associated with a mesenchymal phenotype and generate increased numbers of metastases (Bakhoum et al., 2018). This contrasts with another study, where it was found that decreased STING expression correlated with gastric cancer progression and more aggressive disease (Song et al., 2017). Knockdown of STING in gastric cancer cells resulted in increased migration, invasion, and colony formation, indicating its role in suppressing metastasis (Song et al., 2017). While the results of these studies on the metastatic properties of cancer cells are contradictory, it is evident that depending on the phenotype of the impacted cell (e.g. high chromosomal instability), there can be activation of either canonical or noncanonical NF-κB signaling, resulting in differential outcomes; however, the precise mechanism by which this occurs remains to be determined. In addition, prolonged exposure to IFN can engender an intrinsic resistance of cancer cells to immune control (Benci et al., 2016), thus a chronically inflamed site may permit outgrowth of cancer through a range of mechanisms.

Exogenous activation by administration of ligands

Given that the aforementioned studies demonstrate that nucleic acid sensing within tumors generally acts as a tumor suppressor, emerging studies are exploiting these pathways for its therapeutic potential. Synthetic cyclic dinucleotides have recently been developed for preclinical and clinical use as potent modulators of STING for anticancer therapy. Use of these agonists has been used successfully to induce tumor regression in preclinical models of pancreatic cancer (Baird et al., 2016), HNSCC (Moore et al., 2016, Baird et al., 2018), melanoma (Corrales et al., 2015) as well as in benign papilloma (Baird et al., 2018). Each of these models required intratumoral injection of cyclic dinucleotides as systemic administration fails to induce tumor regression (Baird et al, submitted), which could be problematic for widely metastatic tumors or tumors that are otherwise inaccessible. Given that intratumoral injection of cyclic dinucleotides induces rapid regression of tumors, several groups are studying the effects of cyclic dinucleotide administration on minimal residual disease at time of tumor resection (Park et al., 2018)(Baird et al, submitted). This technique could be particularly useful in instances where the tumor is near critical structures and cannot be fully removed, or instead as a neoadjuvant therapy to induce tumor regression that can render the patient eligible for potentially curative resection. STING ligands have entered the clinical arena in a Phase Ib study whereby a synthetic cyclic dinucleotide is administered with anti-CTLA4 () or with anti-PD-1 (). Additional preclinical studies are ongoing to identify clinical compounds that synergize with STING ligands in an effort to optimize the antitumor immune response while minimizing off-target immune effects.

In considering the role of nucleic acid sensors in cancer therapy, it is important to also discuss their role as vaccine adjuvants. Adjuvants help vaccines improve the antigen-specific immune response by providing signals that encourage presentation of antigens on activated professional antigen presenting cells. These adjuvants can include damage-associated molecular patterns and/or pathogen-associated molecular patterns that activate various pattern recognition receptors of innate immune cells including TLRs, STING – either directly or via cGAS, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs), absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2)-like receptors (ALRs), retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptors (RLRs) or C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) (Kawai and Akira, 2010). Sensing of the damage-associated molecular patterns or pathogen-associated molecular patterns, such as microbial components (e.g. microbial DNA or LPS), by innate immune cells in the context of antigenic foreign proteins or peptides initiates a cascade of immune responses resulting in the elicitation of potent innate and adaptive immune responses against the invading pathogens. Exploitation of this process to target immune responses to tumor antigens is a well-established approach to direct the immune response to clear tumors (Mocellin et al., 2004). This comes with certain caveats, as thus far cancer vaccines have not fulfilled their promise in the clinic (Rosenberg et al., 2004).

In this context, nucleic acid-sensing is an essential strategy employed by the innate immune system to detect both pathogen-derived nucleic acids and self-DNA released by host apoptotic or necrotic cells. This exploits the fact that the presence of nucleic acids that gain access to the cytoplasm is perceived by mammalian cells as “stranger” or “danger” signals that trigger immunological responses. These can be exploited to generate non-specific antiviral states in cells treated with agents that stimulate STING (Sali et al., 2015, Lau et al., 2015, Ishikawa and Barber, 2011, Ishikawa et al., 2009), RIG-I (Goubau et al., 2014, Kato et al., 2005) or TRIF (Sali et al., 2015), but these can also be applied to improve responses to co-administered cancer-associated antigens. In this way, oligonucleotide or small-molecule agonists of nucleic acid sensors are being used in clinical trials to boost the immune response against poorly immunogenic cancers, as adjuvants in therapeutic immunizations against cancer, or in prophylactic vaccines against infections (reviewed in (Coffman et al., 2010, Temizoz et al., 2016)). As we will discuss, one current limitation is that despite extensive study of vaccine adjuvants, there are few clinically approved options that are designed to direct Th1-type T cell responses. The majority of clinically-used vaccine adjuvants, such as alum, are designed to promote antibody-mediated neutralizing immunity to infectious diseases (Oleszycka and Lavelle, 2014). More efficacious cancer vaccine adjuvants can be developed both by developing totally new compounds with adjuvant activities that are optimum for cytotoxic T cell immunity, or by optimizing the formulation using various combinations of existing adjuvants. There are ongoing clinical studies aiming to characterize the types of immune responses elicited by these novel adjuvants to ensure they induce the optimal kind of anti-tumor immune responses in patients.

Poly I:C is a synthetic TLR3 ligand that has been reported to function as a potent type 1 adjuvant capable of activating antigen-specific antibody, CTL and Th1 type immune responses. TLR3 is an endosomal TLR that senses RNA virus infection in the cells by recognizing intracellular dsRNA. In addition to activating the TLR3-mediated signaling pathway, Poly I:C also was found to activate intracellular RNA sensors, RIG-I and MDA5, which is associated with its toxic effects, such as induction of systemic cytokine storms (Kato et al., 2006). Recently, ARNAX, a synthetic DNA–dsRNA hybrid molecule consisting of 140bp of measles virus vaccine strain-derived dsRNA with a 5′ GpC-type phosphorothioated oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) that binds to TLR3 but not to RIG-I or MDA5 in mouse, has been developed to avoid the toxic effects of Poly I:C (Matsumoto et al., 2015). This specific TLR3 ligand can induce potent NK cell- and CTL-mediated anti-tumor immune responses in mouse tumor models when provided along with a model tumor antigen (Matsumoto et al., 2015). This TLR3-aduvant-tumor-associated antigen vaccine approach synergizes well with anti-PD1 monoclonal antibody therapy to treat tumors that are resistant to vaccine therapy alone (Takeda et al., 2017). Polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid stabilized with poly-L-lysine and carboxymethylcellulose (Poly ICLC, Hiltonol) is another modified Poly I:C that is stabilized for protecting it from degradation by nucleases. In mice it showed that when used as an adjuvant, Poly I:C and Poly ICLC can induce potent tumor-specific CTL, NK and NKT cell responses providing significant tumor regression and prolonged survival of tumor-bearing mice (Damo et al., 2015). Clinical trials involving patients with different types of tumors showed that repetitive intramuscular injections of Poly ICLC without any antigen has low toxicity and promotes anti-tumor immune responses (Salazar et al., 2014). An alternative modified nontoxic Poly I:C analogue is Poly (I:C12C) (Ampligen) developed by introducing regular mismatching bases (G and U) into Poly I:C. These modifications make it more susceptible to hydrolysis and concomitantly decreasing its toxicity (reviewed in (Jasani et al., 2009)). It was shown that systemic administration (intravenous) of Poly (I:C12C) was nontoxic and well tolerated in HIV+ patients. Furthermore, clinical trials in patients with metastatic malignancies, such as renal cancer, revealed that Poly (I:C12C) can boost anti-tumor immune responses to provide clinical benefit and prolonged survival to patients via mechanisms activating potent NK and T-cell responses (Jasani et al., 2009).

As with TLR3, synthetic TLR9 ligands have been used as cancer vaccine adjuvants. CpG ODN is a synthetic TLR9 ligand capable of activating the TLR9–MyD88–IRF7 signaling pathway to induce type I interferons in addition to activating the TLR9–MyD88–NF-κB signaling pathway to induce pro-inflammatory cytokine production from immune cells (reviewed in (Krieg, 2006)). Clinical trials evaluating the adjuvant activities of CpG ODNs demonstrated that CpG ODNs can induce Th1-type immune responses, thereby becoming potential cancer vaccine adjuvants (reviewed in (Temizoz et al., 2016)). Among the different types of CpG ODNs, D type ODN (class A ODN) can potently induce type I interferon production from pDCs but fails to activate B cells for antibody production. However, because of the presence of poly-G tails, D type ODN can form aggregates, limiting its applications for clinical use. On the other hand, K type CpG ODN (class B ODN), such as K3 CpG, doesn’t form aggregates in solution, and it is capable of potently activating B cells for antibody and IL-6 production while only weakly inducing type I interferon production from pDCs (reviewed in (Krieg, 2006). Therefore, the clinically available CpG ODN is a K type ODN. Clinical trials using CpG ODN as immunotherapeutic agents in cancer patients, such as melanoma and NSCLC, suggested that combination with chemotherapy or CpG ODN monotherapy can induce potent anti-tumor immune responses that correlate with clinical benefit (reviewed in (Temizoz et al., 2016)).

Similarly, anti-cancer vaccines are being built around TLR7 ligands. TLR7 recognizes viral single-strand RNA and imidazoquinoline derivatives, including resiquimod (R848) and imiquimod. Although the mode of action of imiquimod is not completely understood, induction of type I interferons via the TLR7–MyD88–IRF7 pathway is known to play a major role for mediating its anti-viral and anti-tumor activities. An imiquimod based liquid formulation, TMX-101 (Vesimune), is currently being tested in a phase II clinical trial for noninvasive bladder cancer patients as an immunotherapeutic agent (reviewed in (Temizoz et al., 2016, Vacchelli et al., 2012)).

One limitation on the application of adjuvants as cancer vaccines is the necessity to identify a suitable tumor associated antigen. While patients can exhibit diverse mutations that can be included in antigenic peptides, there are few mutated tumor antigens that are shared between different individuals, particularly in view of MHC diversity. Thus, more common approaches have tested vaccines against cancer testes antigens, such as MAGE antigens, those with differential expression, such as MUC1, or targets overexpressed in cancer, such as telomerase (reviewed in (Vacchelli et al., 2012)). While these have generated antigen-specific responses, clinical success has been more elusive (Katakami et al., 2017, Butts et al., 2014). One issue is that they are not truly cancer specific, and we do not know whether responses to normal tissue blunts the anti-cancer immune response. When highly effective CAR T cells for melanoma-specific antigens were transferred to patients, they resulted in toxicity due to recognition of normal melanocytes (Johnson et al., 2009). These data suggest that when the response to antigens shared by normal cells is highly effective, toxicity becomes a limiting factor. Nevertheless, there are potential cancer specific shared antigens. EGFRvIII is a constitutively active and tumor-specific deletional mutant of EGFR found in a range of cancers including glioblastoma multiforme (GBM). The deletion of EGFR exons 2-7 results in a novel glycine at the junction and yields a tumor-specific antigen with demonstrated immunogenicity (Choi et al., 2009). Sampson et al. demonstrated that a peptide vaccine for the EGFRVIII antigenic peptide (CDX110) was safe and generated detectable peptide specific DTH responses in approximately half of the patients (Sampson et al., 2009). This approach was also effective in phase II clinical studies (Sampson et al., 2010), but did not show efficacy in a randomized phase III study (Weller et al., 2017). One caveat here is that the vaccine approach focused on humoral responses to EGFRvIII rather than T cell responses. By contrast, vaccine strategies based around engineered Listeria monocytogenes (Brockstedt et al., 2004, Brockstedt et al., 2005), which generate strong CD8 T cell-mediated responses to expressed antigens (Pamer, 2004), can generate strong protective immunity to EGFRvIII-expressing tumors in preclinical models (Zebertavage et al. submitted). Preliminary patient studies with CAR T cells targeting EGFRvIII have also shown promising results (O’Rourke et al., 2017). Therefore, common shared deletional mutants such as EGFRvIII may remain promising targets for cell-mediated approaches to control tumors. With the advent of large scale sequencing, it has become possible to identify patient-specific antigenic mutations using computational pipelines, and synthesis polyepitope vaccines for each patient (reviewed in (Tran et al., 2017)). This is a potential solution to develop true tumor-specific cancer vaccines and will be dependent on an appropriate combination with immune adjuvants capable of driving Th1-type cytotoxic T cell responses, such as synthetic ligands of nucleic acid sensors.

Endogenous nucleic acid sensor activation by host ligands

In view of our limited ability to develop cancer vaccines that apply to many different patients due to the great variation in antigenic mutations between people, an alternative approach is to use the patients own tumor as the nexus to initiate anti-tumor immunity (Crittenden et al., 2005). As discussed above, initial immune recognition of infection is often triggered through the recognition of conserved microbial patterns including those based on nucleic acids.

Of course, under normal conditions double-stranded DNA would not be anticipated to enter the cytosol. In healthy cells DNA is restricted to the nucleus and mitochondria, which avoids inappropriate activation of the immune system. The presence of both DNA damage responses and mechanisms to detect and destroy endogenous DNA play an important role in normal cell behavior to protect the fidelity of an organism’s genetic material. Thus, failure to correct damaged DNA can result in an array of diseases. Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) both remove double stranded breaks, most commonly caused by radiation damage, replication errors and certain mutagens (reviewed in (West, 2003)). Single-strand break repair (SSBR) ligates nicked DNA strands whereas mismatch repair (MMR) restores errors that occur during replication (reviewed in (Caldecott, 2008, Jiricny, 2006)). Base excision repair (BER) and nucleotide excision repair (NER) reverse oxidative base modifications caused by free radicals and other oxidative stressors (reviewed in (Hoeijmakers, 2009, Bauer et al., 2015)). The interruption of these processes can result in abnormal accumulation and distribution of endogenous DNA fragments that have the potential to activate endogenous nucleic acid sensors. Thus, under stressful conditions modified endogenous DNA can trigger immune responses. In response to genomic stress yielding from a wide variety of sources: Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) (Gehrke et al., 2013), redox-cycling events, ultraviolet light (Gao et al., 2013), ionizing radiation (Vanpouille-Box et al., 2017, Harding et al., 2017), and wide variety of chemical agents along with replication stress (Mackenzie et al., 2017), genomic DNA can accumulate in the cytoplasm.

The process by which genomic DNA gains access to the innate immune sensors residing in the cytoplasm has been recently addressed by a series of papers (Mackenzie et al., 2017, Harding et al., 2017, Bartsch et al., 2017). Chromosomal damage that occurs either by a normal cellular process such as mitosis or by exogenous physical or chemical stressors, can result in fragmentation of chromosomes that are separated from the main chromatin mass. These can become enveloped by the nuclear membrane to form micronuclei that are separate from the primary nucleus. cGAS localizes to micronuclei and breakdown of the micronuclei membrane provides access of cGAS to DNA, resulting in activation of IFN pathways in these cells (Mackenzie et al., 2017, Bartsch et al., 2017). Therefore, this breakdown of the micronuclei membrane is a limiting factor in activation of cytoplasmic nucleic acid sensors. Closer examination of these micronuclei reveals that they contain an incomplete nuclear lamina, a fibrillar network composed of intermediate filaments and associated proteins that collectively function to give structure and maintain the structural integrity of the nucleus (Hatch et al., 2013). Fluorescence microscopy reveals sites of weakness in the micronuclear lamina, holes where the nuclear membrane can provide access to the chromatin within (Hatch et al., 2013). Thus, cGAS accumulates specifically in micronuclei with ruptured nuclear envelopes (Mackenzie et al., 2017), and does not necessarily require entry of DNA into the cytosol. However, ensuing micronuclear collapse can result in exposed chromatin in the cytoplasm (Hatch et al., 2013). These data indicate that while the primary nucleus remains intact, micronuclei formed following DNA damage can become disrupted, providing access to cGAS and endogenous synthesis of the STING ligand cGAMP. Similar mechanisms are necessary to explain how RIG-I, an endogenous sensor of viral RNA, can be activated in the absence of infection. It is plausible that micronuclei similarly carry triphosphorylated RNA ends that are present in the nucleus of cells early following transcription to the cytoplasm to activate RIG-I. RIG-I (Ranoa et al., 2016) and LGP2 (Widau et al., 2014), but not MDA5, (Sun et al., 2006) have been shown to detect endogenous nuclear material that has translocated to the cytoplasm following radiation therapy. Recent studies demonstrated that following radiation, cells produce type I IFN in a RIG-I dependent manner (Ranoa et al., 2016). LGP2 was shown to have an opposite effect and following radiation therapy LGP2 suppressed type I IFN induction (Widau et al., 2014). Interestingly, IFN induction was shown to contribute to the death of the irradiated cells, such that mice lacking RIG-I are protected against gastrointestinal epithelial cell death following total body radiation (Ranoa et al., 2016). However, it may not be necessary for RIG-I to directly recognize nucleic acids in order to contribute to local inflammation. RIG-I can physically associate with STAT1 and prevent SHP1-mediated inactivation of STAT1 (Hou et al., 2014). In this way, RIG-I can accentuate an initial IFN signal in cells, resulting in prolonged local inflammation without requiring interaction with viral RNA (Hou et al., 2014).

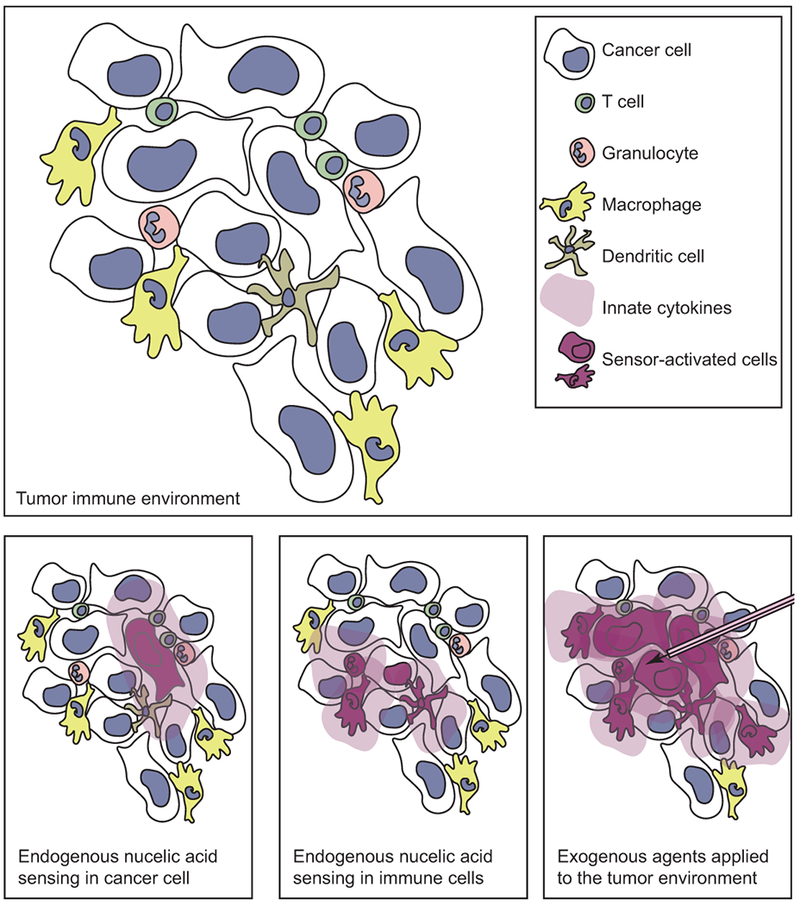

Despite the potential for DNA to enter the cytosol, cells have intrinsic mechanisms to degrade cytoplasmic DNA, which also exist in part as mechanisms to control infection. These include DNase I and DNase II, which degrade DNA in the cytoplasm. However, TREX1 (DNase III) appears a critical molecule that regulates extranuclear DNA activation of immune pathways (Lehtinen et al., 2008, Stetson et al., 2008). Mice lacking TREX1 exhibit inflammatory diseases (Morita et al., 2004) and develop lupus-like autoimmunity (Grieves et al., 2015) via increased IFN production (Stetson et al., 2008). If not degraded by DNA exonucleases, cytosolic genomic DNA will be recognized by cGAS, leading to cyclic dinucleotide production, STING activation and ultimately the activation of the immune system via type I IFN (Hartlova et al., 2015). Thus, in cells lacking TREX1, cGAS is still required for IFN induction (Ablasser et al., 2014). Importantly, TREX-mediated destruction of cytoplasmic DNA has been shown to be a limiting factor in innate immune activation following irradiation of cancer cells, and while increasing doses of radiation result in increasing DNA in the cytosol, increased TREX expression counteracts any benefit of increased dose (Vanpouille-Box et al., 2017). The quality of cytoplasmic DNA also influences the consequence to the cells, since DNA that has undergone oxidative damage limits TREX1 degradation and potentiates sensing via cGAS and STING (Gehrke et al., 2013). These data indicate that despite careful regulatory pathways to control access of DNA to the cytoplasm, under unconventional conditions, during damage, or in transformed cells, the endogenous nucleic acid sensing can be activated, resulting in activation of immune mechanisms (Figure 2). These can lead to pathologic autoimmunity, or be exploited to engender anti-cancer immunity.

Figure 2.

The tumor can contain a heterogenious cell population including cancer cells and immune cell types that can respond to nucleic acids. Nucleic acid sensing in cancer cells can result in inflammatory cytokine secretion to the microenvironment, or cancer cell material can be transfered to the neighboring immune cells, which can themselves sense nucleic acids and secrete inflammatory cytokines. Alternatively, exogenous administration of agents that activate nucleic acids can result in activation of multiple cell types in the tumor environment.

Does cancer have a particular tendency to activate nucleic acid sensors?

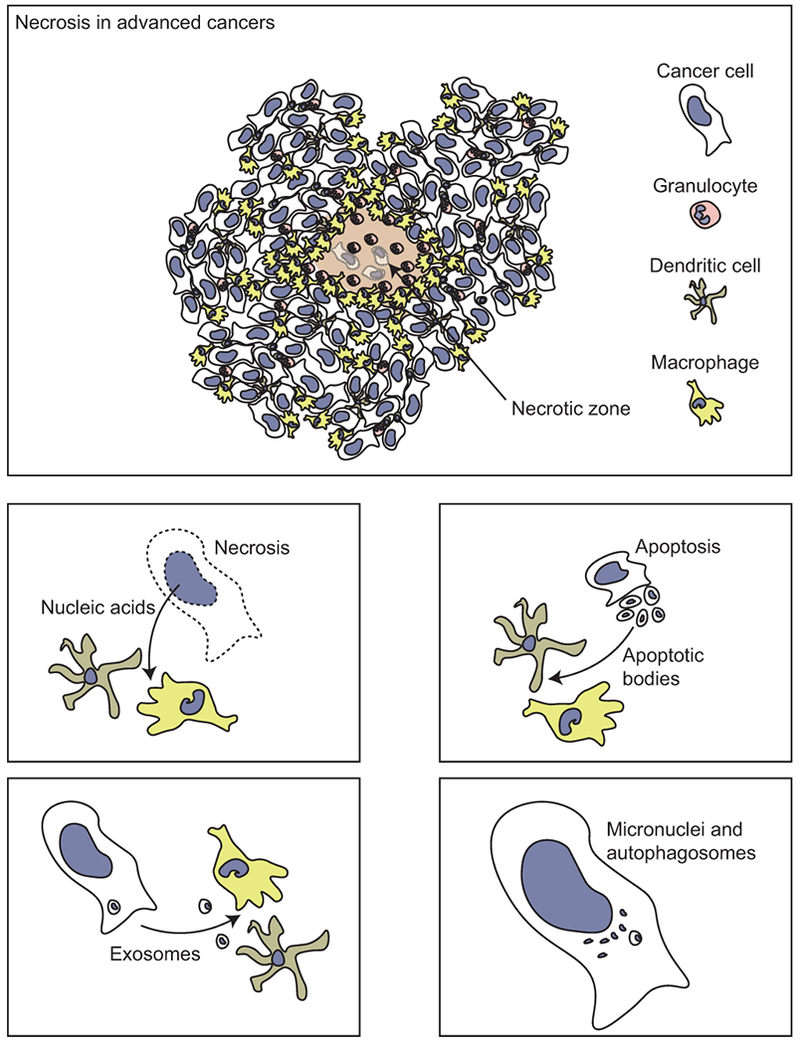

Since cancer cells fit into a number of the categories described above that can result in endogenous activation of nucleic acid sensors, and there is evidence that these sensors can regulate tumorigenesis and progression, it begs the question as to whether these sensors are constantly active in cancer cells. However, in addition to cell-intrinsic nuclear material, cancer can have an abundant supply of extrinsic nuclear material, since areas of necrosis are frequently detectable in growing tumors (Figure 3). Necrotic material includes a range of endogenous adjuvants with varying ability to stimulate immune responses to associated proteins (Melcher et al., 1999). There is extensive literature that correlates prognosis of cancer patients with the presence of pathological necrosis in their tumor. While there can be conflicting results (reviewed in (Gkogkou et al., 2014, Richards et al., 2011)), there is a propensity that the presence of necrosis is associated with poor outcomes across a range of malignancies (Pichler et al., 2012, Pollheimer et al., 2010, Atanasov et al., 2017, Maiorano et al., 2010). If the release of cancer associated antigens and nucleic acids is a positive feature to generate anti-tumor immunity though associated activation of nucleic acid sensing pathways, these clinical data suggest the opposite. The presence of necrosis is often associated with larger tumors of higher grade, suggesting that these tumors have aggressively outstripped their supporting vasculature and stroma resulting in necrotic zones, but may also be sufficiently resistant to immune mechanisms so that innate immune activation either does not occur or does not impact tumor growth.

Figure 3.

Necrosis is a common feature in advanced cancers, due to aggressive growth of cancer cells outstripping the vascular supply. Necrosis can supply endogenous nucleic acids to surrounding immune cells. In addition, nucleic acids can be provided by apoptotic bodies, exosomes, or detected endogenously via micronuclei or autophagosomes.

It is plausible that the response to necrotic material is limited by prior exposure of immune cells in the tumor environment to apoptotic cells. The presence of high levels of apoptotic cell death in the tumor has had mixed value as a prognostic tool to predict outcome across cancers (de Jong et al., 1999, Ghosh et al., 2001). The apoptotic index a complicated gauge to interpret, since there are many ways to measure apoptosis. Broadly it would be assumed that more dying cancer cells is a benefit, and yet high levels of apoptosis often go along with high levels of cancer cell proliferation (Michael-Robinson et al., 2001). Therefore, as with measures of necrosis, patients with abundant dying cells are similarly not showing evidence of improved outcome, but instead associate with poor outcome. In view of these data, it is perhaps more critical to consider the cells that respond to endogenous adjuvants released from dying cancer cells, in addition to the presence or the quality of this antigen (Gough et al., 2001). While there are many phagocytes, only a subset of these can cross-present antigen to CD8 T cells. Similarly, while many cells can respond with pro-inflammatory signals to the presence of endogenous or exogenous adjuvants, phagocytes in tumors are commonly differentiated into phenotypes with a poor response to adjuvant signals. In mice, the progressive macrophage infiltration of tumors has been shown to be critical for neoangiogenesis, tumor progression and establishment of distant metastases (Lin et al., 2006, Lin et al., 2001) and larger macrophage infiltrates correlate with poor prognosis in patients (Leek et al., 1996). Macrophage infiltration is associated with necrotic areas in patient tumors (Leek et al., 1999) and the presence of these macrophages results in high levels of VEGF and increased microvessel density in patient tumors (Leek et al., 2000), likely as a biological attempt to overcome the hypoxia present in necrotic regions. Tumor macrophages are generally differentiated into phenotypes that can suppress T cell activation (Rodriguez et al., 2004), and treatment of these tumor macrophages with immunological adjuvants results in production of anti-inflammatory rather than pro-inflammatory cytokines (Crittenden et al., 2012). There is often a reciprocal relationship between T cell infiltration and macrophage infiltration in tumors, and where T cells are low and macrophages are high, the prognosis is especially poor (Mitchem et al., 2013, DeNardo et al., 2011). The mechanisms by which macrophages become suppressive to T cells may relate to the degree of cell death in the tumor. In vitro, apoptotic cells drive differentiation of macrophages into suppressive phenotypes that involve secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as TGFβ and IL-10 and upregulation of suppressive molecules such as arginase I (Freire-de-Lima et al., 2006). In vivo, systemic administration of apoptotic cells is an efficient means to generate antigen-specific tolerance (A-Gonzalez et al., 2009) Thus, the data supports a model where an aggressive tumor that outstrips its supportive structures can result in death of cancer cells, resulting in local necrosis. This, in turn, results in macrophage recruitment and following local interaction with dying cancer cells, these macrophages undergo M2 differentiation, secrete VEGF and precursors of collagen biosynthesis (Rodriguez et al., 2004, Rodriguez et al., 2003), and direct revascularization and reorganization of the damaged tumor environment.

In this setting, the effect of tumor-derived material on nucleic acid sensors in the tumor environment may be unpredictable. However, nucleic acid sensors can also be activated by particles released by cells within the tumor microenvironment (Figure 3). These particles include exosomes, microparticles/vesicles and autophagosomes that all vary in size. Exosomes are 60-100 nm vesicles that originate from multivesicular bodies and fuse with the plasma membrane upon release into the extracellular space (Zhang et al., 2015, Kurywchak et al., 2018). Microparticles, on the other hand, are larger in size (100–1000 nm) and are usually created in response to stress in which the parental cellular membrane encapsulates cytoplasm (Mause and Weber, 2010, Zhang et al., 2015). Autophagosomes vary in size (200–900 nm) and are vesicles produced upon autophagy induction (Yi et al., 2012). Despite the differences in formation of these tumor-derived particles, they contain a variety of material from the parental cell from which they derive from, including many proteins, RNA and DNA (Kurywchak et al., 2018, Thakur et al., 2014, Yi et al., 2012). Exosomes and autophagosomes are also replete with mitochondrial nuclear acids (Thakur et al., 2014, Medeiros et al., 2018). Given the presence of RNA and DNA found within these vesicles, activation of nucleic acid sensors within recipient cells that phagocytose and engulf these particles is expected; however, the resulting outcome may lead contrastingly to tumor progression and metastasis, or antitumor immune responses that can control tumor progression and metastases.

Particles found within the tumor microenvironment have been associated with tumor progression and metastasis through nucleic acid sensing (Figure 3). Exosomes derived from stromal cells were shown to contain RNA, which when transferred to breast cancer cells, activated RIG-I and antiviral signaling, leading to tumor progression that was resistant to therapy (Boelens et al., 2014). Nabet et al. further showed that the exosomes derived from stromal cells contained unshielded RNA, which did not have RNA-binding proteins attached as is found in the parental cells (Nabet et al., 2017). The unshielded RNA led to RIG-I activation in recipient breast cancer cells leading to inflammation that promoted metastases. In addition, if immune cells were the recipients of the exosomes with unshielded RNA, myeloid and dendritic cell subsets showed increased expression of activation markers and an inflammatory response was generated suggesting that the unshielded RNA found within the exosomes acted as a damage associated molecular pattern. Furthermore, Liu et al. showed that lung cancer-derived exosomes contain small nuclear RNAs which activate TLR3 in recipient alveolar type II cells (Liu et al., 2016). This TLR3 activation led to chemokine secretion that recruited neutrophils and promoted lung metastasis. Interestingly, only exosomal RNA, which was enriched with non-coding RNAs, and not tumor cell RNA, was responsible for the TLR3 activation (Liu et al., 2016, Antonopoulos et al., 2017). Moreover, microRNA found in tumor-derived exosomes can trigger murine TLR7 and human TLR8 in macrophages, also leading to tumor progression and metastases (Fabbri et al., 2012). Therefore, different forms of RNA found within exosomes have shown to promote tumor progression through activation of nucleic acid sensors in recipient cells, thus also promoting the use of exosomes as negative diagnostic biomarkers (Skog et al., 2008).

On the other hand, tumor-derived particles can also lead to antitumor immune responses. Kitai et al. used topotecan, a topoisomerase I inhibitor that triggers cell death, to treat breast cancer cells (Kitai et al., 2017). Topotecan treatment resulted in exosomes released from the breast cancer cells that contained DNA, which in turn activated the STING and IRF3 pathway when cultured with dendritic cells. Breast cancer-bearing mice treated with exosomes derived from topotecan-treated cells showed delayed tumor growth, which was abrogated in STING knockout mice showing a dependency on STING for antitumor immunity generated by the exosomes. In a similar manner, tumor cells exposed to ultraviolet radiation led to the release of tumor microparticles (Zhang et al., 2015). These tumor microparticles contained DNA, which when transferred to dendritic cells, led to Type I IFN production through the cGAS-STING pathway. The DNA found within these tumor microparticles were of genomic and mitochondrial origin. The microparticles also contained RNA, however Type I IFN production by dendritic cells was unaffected by RIG-I knockdown. Another pathway of IRF3 activation through exosomes was shown with exosomes derived from oral cancer cells (Wang et al., 2018b). The formation of these oral cancer-derived exosomes was not induced but purified from the supernatants of cultured oral cancer cells. These exosomes were found to be enriched with NAP1 (NF-κB-activating kinase associated protein 1), which acts upstream of IRF3. When NK cells internalized these exosomes, increased IRF3 phosphorylation and type I IFN production resulted, which further augmented NK cell cytotoxicity. In addition to exosomes and microparticles, tumor-derived autophagosomes or DRibbles (defective ribosomal products and short-lived protein-filled autophagosomes) have also shown to activate nucleic acid sensors, in particular TLR7 and TLR8, as well as TLR2, TLR4 and NOD2 (Xing et al., 2016). DRibbles are prepared by inducing autophagy and preventing lysosomal function in tumor cells resulting in the release of autophagosomes in the supernatant after mild sonication (Li et al., 2011). These resulting autophagosomes contain a wide variety of proteins and damage associated molecular patterns that induce pro-inflammatory cytokine production by immune cells (Xing et al., 2016), T-cell activation (Yi et al., 2012, Li et al., 2008) and therapeutic efficacy in vaccinated tumor-bearing mice (Li et al., 2011, Su et al., 2015).

Therefore, exosomes or particles found within the tumor microenvironment, derived from either tumor cells or surrounding stromal cells, can also activate nucleic acid sensors. In this case, nucleic acid sensor activation can result in either a pro-tumor or anti-tumor response. The response generated depends on the type of cells to which the particles are transferred to as well as how the particle production is induced and released, by which immune stimulating anti-tumor properties usually result when particles are produced from cells exposed to stress (Thery et al., 2009, Chen et al., 2011).

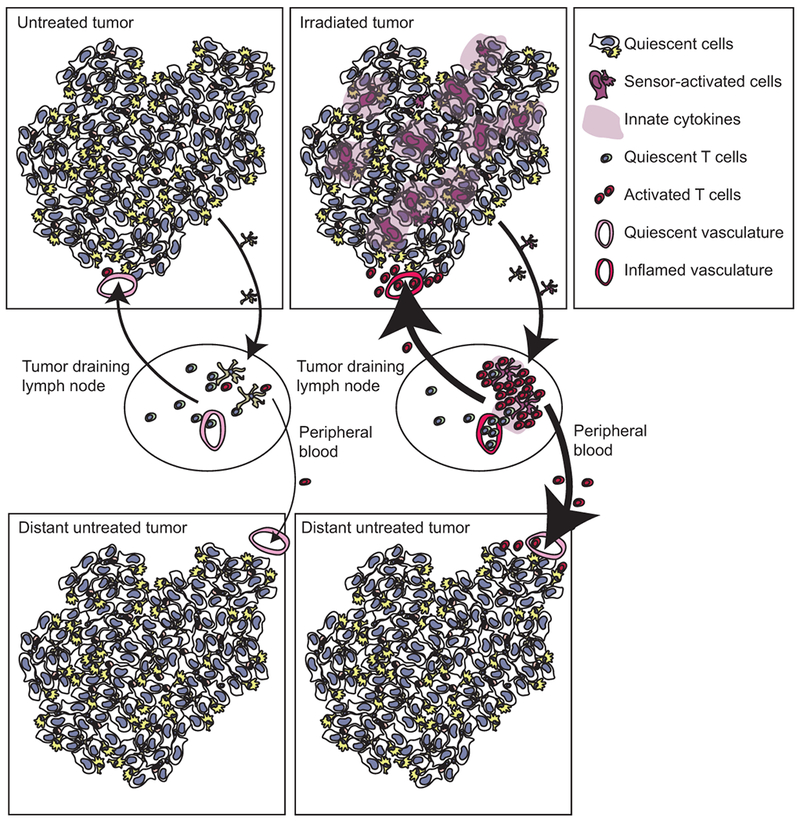

Role of DNA damaging agents in cancer treatment

As discussed above, there is an abundance of data indicating that delivering agents that activate nucleic acid sensors in tumors can activate anti-cancer immunity in part by triggering nucleic acid sensing mechanisms within damaged cells. In view of these data, it would suggest that nucleic acid sensing mechanisms may contribute to immune activation following conventional cytotoxic therapies. Recent data suggest that this may be true (Vanpouille-Box et al., 2017, Harding et al., 2017). Radiation therapy was shown to activate STING in cancer cells via cGAS recognition of endogenous DNA in the cytoplasm (Vanpouille-Box et al., 2017, Harding et al., 2017). These effects were shown to be critical for immune-mediate control of residual cancer cells in the treated animals (Figure 4). In view of these positive benefits of radiation therapy on anti-tumor immune responses it is puzzling that the overwhelming experience of treating millions of cancer patients over the course of decades is that radiation very, very rarely results in immune control of untreated tumors (Abuodeh et al., 2015). The combination of radiation therapy with other immunotherapies has changed that situation, with multiple case studies (Stamell et al., 2012, Postow et al., 2012) or early phase clinical trials (Golden et al., 2015, Seung et al., 2012) demonstrating immune mediated control of distant disease following radiation therapy of a limited subset of tumors. These data suggest that additional immunological interventions are needed to translate radiation-mediated activation of nucleic acid sensors in the tumor environment into distant responses. In addition, the contribution of nucleic acid sensors to tumor control varies according to the specific features of the tumor. In highly immunogenic tumors that are spontaneously rejected in mice with a competent immune system, the loss of STING in host dendritic cells allows these tumors to grow (Woo et al., 2014). In immunogenic tumors that grow in immune competent mice, but can be effectively cured by radiation therapy alone, endogenous activation of STING via the activity of cGAS in antigen-presenting cells is required for radiation-mediated local control (Deng et al., 2014). In our experience using poorly immunogenic tumors, the presence or absence of STING in the host does not affect tumor growth, but this could be substituted by local application of exogenous synthetic STING ligands in combination with radiation therapy (Baird et al., 2016). These data suggest that the immunogenicity of tumors – their ability to be rejected by immune mechanisms – is linked to endogenous nucleic acid sensing. However, with poorly immunogenic tumors the combination of exogenously applied STING ligands combined with radiation therapy had a limited ability to control distant tumors despite an increase in systemically circulating tumor antigen-specific T cells (Baird et al., 2016). This is consistent with the preclinical data showing that radiation therapy can activate cGAS-mediated activation of STING directly in irradiated cancer cells, since in this setting radiation therapy did not affect distant tumors without the addition of anti-CTLA4 monoclonal antibodies (Vanpouille-Box et al., 2017, Harding et al., 2017). Even without radiation therapy, the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors has been shown to be dependent on nucleic acid sensing machinery for optimal tumor control (Wang et al., 2017b). These data suggest that while nucleic acid sensing machinery can contribute to local control of tumors by radiation therapy, effective control of distant disease remains susceptible to the same checkpoint regulations that suppress adaptive immunity in tumors (Figure 4). However, the critical event here is that local activation of nucleic acid sensing machinery by radiation therapy improves the generation of antigen specific T cells, and without these, checkpoint inhibitors may have no effectors to assist.

Figure 4.

Following radiation therapy, tumor associated antigens can be released to antigen-presenting cells that can travel to draining lymphatics and activate antigen-specific T cells. Activation of nucleic acid sensors can improve the fuction of antigen-presenting cells, permitting increased T cell expansion and improved recruitment of T cells to the draining lymphatics and back to the tumor via inflamed endothelia. Increased antigen specific T cells in the peripheral circulation can also travel to distant, untreated tumors, but their recruitment will be limited by poorly inflamed vasculature and ongoing negative regulation in the untreated site.

This dependence of checkpoint inhibitors on pre-existing immunity or immune responses generated by radiation therapy makes sense, since they act to block suppressive mechanisms rather than to generate de novo T cells. Consistent with this, we recently demonstrated that where pre-existing immunity is blocked, the combination of radiation therapy and checkpoint inhibitors is no longer able to control tumors (Crittenden et al., 2018). These data match prior studies using implantation of tumors as fragments rather than cell suspensions, which is an approach that can avoid implantation-mediated immunity to the tumor (Ochsenbein et al., 2001, Ochsenbein et al., 1999). Where tumors are implanted as fragments, radiation therapy plus checkpoint inhibition first required tumor antigen-specific vaccination before the combination was able to fully control of tumors (Zheng et al., 2016). In studies using tumors with lower levels of antigen that do not generate sufficient pre-existing immunity to allow tumor control, additional tumor antigen-specific vaccination was necessary for tumor control by radiation therapy (Kudo-Saito et al., 2005, Hodge et al., 2012). Therefore, nucleic acid sensing may be essential to initiate new immune responses as part of vaccines, as discussed above, or to propagate responses via IFN induction in irradiated cancer cells; however, it remains likely that additional interventions will be required to permit full immune-mediated control of residual cancer cells, and particularly where those residual cancer cells are outside the treatment field.

Conclusions

Nucleic acid sensors represent a particularly potent group of molecular pathways capable of initiating anti-bacterial and anti-viral immunity both via innate mechanisms as well as via induction of cell-mediated immunity. These pathways can also play a role in tumorigenesis, but triggering these pathways in advanced cancers can generate protective anti-tumor immune responses. There is a long history of combining innate adjuvants as part of anti-cancer vaccines (reviewed in (Coffman et al., 2010, Temizoz et al., 2016)) or with cytotoxic therapies (reviewed in (Baird et al., 2017b)); however, it has recently become clear that many of our conventional cancer therapies themselves trigger these innate immune mechanisms, and that this plays a role in their success. Understanding how best to manipulate these pathways to optimize local control for tumors, and amplify systemic control of metastatic disease, will likely require an improved understanding of the context of immune activation in the tumor environment, as well as the key cells that control positive and negative outcomes following combination therapies. In view of the key role of nucleic acid sensors in directing cell-mediated immunity, these likely remain potent targets for cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by NCI R01CA182311 (MJG), and an American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowship award (JRB).

References

- A-GONZALEZ N, BENSINGER SJ, HONG C, BECEIRO S, BRADLEY MN, ZELCER N, DENIZ J, RAMIREZ C, DIAZ M, GALLARDO G, DE GALARRETA CR, SALAZAR J, LOPEZ F, EDWARDS P, PARKS J, ANDUJAR M, TONTONOZ P & CASTRILLO A 2009. Apoptotic cells promote their own clearance and immune tolerance through activation of the nuclear receptor LXR. Immunity, 31, 245–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ABE T & BARBER GN 2014. Cytosolic-DNA-Mediated, STING-Dependent Proinflammatory Gene Induction Necessitates Canonical NF-κB Activation through TBK1. Journal of Virology, 88, 5328–5341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ABLASSER A, HEMMERLING I, SCHMID-BURGK JL, BEHRENDT R, ROERS A & HORNUNG V 2014. TREX1 deficiency triggers cell-autonomous immunity in a cGAS-dependent manner. J Immunol, 192, 5993–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ABUODEH Y, VENKAT P & KIM S 2015. Systematic review of case reports on the abscopal effect. Curr Probl Cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AHN J, XIA T, KONNO H, KONNO K, RUIZ P & BARBER GN 2014. Inflammation-driven carcinogenesis is mediated through STING. Nat Commun, 5, 5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANTONOPOULOS D, BALATSOS NAA & GOURGOULIANIS KI 2017. Cancer’s smart bombs: tumor-derived exosomes target lung epithelial cells triggering pre-metastatic niche formation. J Thorac Dis, 9, 969–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATANASOV G, DIETEL C, FELDBRUGGE L, BENZING C, KRENZIEN F, BRANDL A, MANN E, ENGLISCH JP, SCHIERLE K, ROBSON SC, SPLITH K, MORGUL MH, REUTZEL-SELKE A, JONAS S, PASCHER A, BAHRA M, PRATSCHKE J & SCHMELZLE M 2017. Tumor necrosis and infiltrating macrophages predict survival after curative resection for cholangiocarcinoma. Oncoimmunology, 6, e1331806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAIRD JR, FENG Z, XIAO HD, FRIEDMAN D, COTTAM B, FOX BA, KRAMER G, LEIDNER RS, BELL RB, YOUNG KH, CRITTENDEN MR & GOUGH MJ 2017a. STING expression and response to treatment with STING ligands in premalignant and malignant disease. PLoS One, 12, e0187532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAIRD JR, FENG Z, XIAO HD, FRIEDMAN D, COTTAM B, FOX BA, KRAMER G, LEIDNER RS, BELL RB, YOUNG KH, CRITTENDEN MR & GOUGH MJ 2018. Correction: STING expression and response to treatment with STING ligands in premalignant and malignant disease. PLoS One, 13, e0192988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAIRD JR, FRIEDMAN D, COTTAM B, DUBENSKY TW JR., KANNE DB, BAMBINA S, BAHJAT K, CRITTENDEN MR & GOUGH MJ 2016. Radiotherapy Combined with Novel STING-Targeting Oligonucleotides Results in Regression of Established Tumors. Cancer Res, 76, 50–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAIRD JR, MONJAZEB AM, SHAH O, MCGEE H, MURPHY WJ, CRITTENDEN MR & GOUGH MJ 2017b. Stimulating Innate Immunity to Enhance Radiation Therapy-Induced Tumor Control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 99, 362–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAKHOUM SF, NGO B, LAUGHNEY AM, CAVALLO JA, MURPHY CJ, LY P, SHAH P, SRIRAM RK, WATKINS TBK, TAUNK NK, DURAN M, PAULI C, SHAW C, CHADALAVADA K, RAJASEKHAR VK, GENOVESE G, VENKATESAN S, BIRKBAK NJ, MCGRANAHAN N, LUNDQUIST M, LAPLANT Q, HEALEY JH, ELEMENTO O, CHUNG CH, LEE NY, IMIELENSKI M, NANJANGUD G, PE’ER D, CLEVELAND DW, POWELL SN, LAMMERDING J, SWANTON C & CANTLEY LC 2018. Chromosomal instability drives metastasis through a cytosolic DNA response. Nature, 553, 467–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARTSCH K, KNITTLER K, BOROWSKI C, RUDNIK S, DAMME M, ADEN K, SPEHLMANN ME, FREY N, SAFTIG P, CHALARIS A & RABE B 2017. Absence of RNase H2 triggers generation of immunogenic micronuclei removed by autophagy. Hum Mol Genet, 26, 3960–3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAUER NC, CORBETT AH & DOETSCH PW 2015. The current state of eukaryotic DNA base damage and repair. Nucleic Acids Res, 43, 10083–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BENCI JL, XU B, QIU Y, WU TJ, DADA H, TWYMAN-SAINT VICTOR C, CUCOLO L, LEE DSM, PAUKEN KE, HUANG AC, GANGADHAR TC, AMARAVADI RK, SCHUCHTER LM, FELDMAN MD, ISHWARAN H, VONDERHEIDE RH, MAITY A, WHERRY EJ & MINN AJ 2016. Tumor Interferon Signaling Regulates a Multigenic Resistance Program to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cell, 167, 1540–1554 e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BHATELIA K, SINGH A, TOMAR D, SINGH K, SRIPADA L, CHAGTOO M, PRAJAPATI P, SINGH R, GODBOLE MM & SINGH R 2014. Antiviral signaling protein MITA acts as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer by regulating NF-kappaB induced cell death. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1842, 144–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLASIUS AL & BEUTLER B 2010. Intracellular Toll-like Receptors. Immunity, 32, 305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOELENS MC, WU TJ, NABET BY, XU B, QIU Y, YOON T, AZZAM DJ, TWYMAN-SAINT VICTOR C, WIEMANN BZ, ISHWARAN H, TER BRUGGE PJ, JONKERS J, SLINGERLAND J & MINN AJ 2014. Exosome transfer from stromal to breast cancer cells regulates therapy resistance pathways. Cell, 159, 499–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROCKSTEDT DG, BAHJAT KS, GIEDLIN MA, LIU W, LEONG M, LUCKETT W, GAO Y, SCHNUPF P, KAPADIA D, CASTRO G, LIM JY, SAMPSON-JOHANNES A, HERSKOVITS AA, STASSINOPOULOS A, BOUWER HG, HEARST JE, PORTNOY DA, COOK DN & DUBENSKY TW JR. 2005. Killed but metabolically active microbes: a new vaccine paradigm for eliciting effector T-cell responses and protective immunity. Nat Med, 11, 853–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROCKSTEDT DG, GIEDLIN MA, LEONG ML, BAHJAT KS, GAO Y, LUCKETT W, LIU W, COOK DN, PORTNOY DA & DUBENSKY TW JR. 2004. Listeria-based cancer vaccines that segregate immunogenicity from toxicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101, 13832–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BU Y, LIU F, JIA QA & YU SN 2016. Decreased Expression of TMEM173 Predicts Poor Prognosis in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. PLoS One, 11, e0165681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURNETTE BC, LIANG H, LEE Y, CHLEWICKI L, KHODAREV NN, WEICHSELBAUM RR, FU YX & AUH SL 2011. The efficacy of radiotherapy relies upon induction of type i interferon-dependent innate and adaptive immunity. Cancer Res, 71, 2488–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUTTS C, SOCINSKI MA, MITCHELL PL, THATCHER N, HAVEL L, KRZAKOWSKI M, NAWROCKI S, CIULEANU TE, BOSQUEE L, TRIGO JM, SPIRA A, TREMBLAY L, NYMAN J, RAMLAU R, WICKART-JOHANSSON G, ELLIS P, GLADKOV O, PEREIRA JR, EBERHARDT WE, HELWIG C, SCHRODER A & SHEPHERD FA 2014. Tecemotide (L-BLP25) versus placebo after chemoradiotherapy for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer (START): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol, 15, 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CALDECOTT KW 2008. Single-strand break repair and genetic disease. Nature Reviews Genetics, 9, 619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN T, GUO J, YANG M, ZHU X & CAO X 2011. Chemokine-containing exosomes are released from heat-stressed tumor cells via lipid raft-dependent pathway and act as efficient tumor vaccine. J Immunol, 186, 2219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHOI BD, ARCHER GE, MITCHELL DA, HEIMBERGER AB, MCLENDON RE, BIGNER DD & SAMPSON JH 2009. EGFRvIII-targeted vaccination therapy of malignant glioma. Brain Pathol 19, 713–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COFFMAN RL, SHER A & SEDER RA 2010. Vaccine adjuvants: putting innate immunity to work. Immunity, 33, 492–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORRALES L, GLICKMAN LH, MCWHIRTER SM, KANNE DB, SIVICK KE, KATIBAH GE, WOO SR, LEMMENS E, BANDA T, LEONG JJ, METCHETTE K, DUBENSKY TW JR. & GAJEWSKI TF 2015. Direct Activation of STING in the Tumor Microenvironment Leads to Potent and Systemic Tumor Regression and Immunity. Cell Rep, 11, 1018–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRITTENDEN M, ZEBERTAVAGE L, KRAMER G, BAMBINA S, FRIEDMAN D, TROESCH V, BLAIR T, BAIRD J, ALICE A & GOUGH M 2018. Tumor cure by radiation therapy and checkpoint inhibitors depends on pre-existing immunity. Scientific Reports. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRITTENDEN MR, COTTAM B, SAVAGE T, NGUYEN C, NEWELL P & GOUGH MJ 2012. Expression of NF-kappaB p50 in tumor stroma limits the control of tumors by radiation therapy. PLoS One, 7, e39295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRITTENDEN MR, THANARAJASINGAM U, VILE RG & GOUGH MJ 2005. Intratumoral immunotherapy: using the tumour against itself. Immunology, 114, 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAMO M, WILSON DS, SIMEONI E & HUBBELL JA 2015. TLR-3 stimulation improves anti-tumor immunity elicited by dendritic cell exosome-based vaccines in a murine model of melanoma. Sci Rep, 5, 17622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE JONG JS, DIEST PJV & BAAK JPA 1999. Number of apoptotic cells as a prognostic marker in invasive breast cancer. British Journal Of Cancer, 82, 368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENARDO DG, ANDREU P & COUSSENS LM 2010. Interactions between lymphocytes and myeloid cells regulate pro-versus anti-tumor immunity. Cancer metastasis reviews, 29, 309–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]