Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Orthotopic vascularized lymph node transplant has been successfully used to treat lymphedema. A second, heterotopic lymph node transplant in the distal extremity may provide further improvement. The vascularized omentum lymphatic transplant (VOLT) provides adequate tissue for two simultaneous flap transfers to one limb. The purpose of this study was to review our experience with this technique.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective study of patients who underwent VOLT, with a subgroup analysis of patients who underwent double VOLT. Technical aspects of the procedure, complications, and early outcomes were reviewed.

Results:

From May 2015 to August 2017, 54 VOLTs were performed in 38 patients, of whom 16 received double VOLT. Among patients in the double VOLT group with postoperative imaging at 1 year, uptake into the transplanted omentum was seen in three of six (50%) patients on lymphoscintigraphy and in one of five (20%) patients on indocyanine green lymphangiography. One patient (3.1%) in the double VOLT group required a return to the operating room. There were no donor site complications in the double VOLT group. The overall complication rate was 15.8%.

Conclusions:

Double VOLT to the mid-level and proximal extremity is a safe and viable option.

Keywords: lymphedema, double omentum, omentum, vascularized lymph node transfer, VOLT

INTRODUCTION

Vascularized omentum lymphatic transplant (VOLT) is a promising technique in the surgical treatment of lymphedema.[1–7] The omentum contains an abundant supply of lymphatic tissue[8–10] over a large surface area, making it a viable option for lymphatic reconstruction, especially for patients who have limited peripheral donor site options because of prior surgery and radiation. It is also an appealing alternative to donor sites such as the groin, axilla, and supraclavicular lymph node basins because it eliminates the risk of donor site lymphedema, which has been reported in peripheral sites.[11–14] The risk of iatrogenic lymphedema at these donor sites may be minimized with reverse lymphatic mapping,[15] but it requires a technetium injection and involves a significant learning curve.

VOLT is based on the right gastroepiploic vessels along which the lymphatic tree and lymph nodes draining the greater curvature of the stomach reside. The gastroepiploic vessels run in continuity along the greater curvature with a consistent caliber enabling division into two separate free flaps. This approach allows for two simultaneous lymph node transplants in the same limb, augmenting the total surface area in contact with stagnant lymph. In our experience, there have been patients with global lymphedema of an extremity who have benefitted from an initial, proximal lymph node transplant and have further improved with a second, mid-level transplant. The proposed mechanism for proximal lymph node transplant is bridging of the defect caused by the prior lymphadenectomy.[16] The proximal recipient site also allows for scar removal and decompression of the axillary vein. In contrast, Cheng and colleagues have described the shunting mechanism for distal lymph node transplant whereby lymph is shunted into the venous circulation through lymphatic interconnections within the lymph node.[17] We have seen positive results using both approaches. The rationale behind a proximal and mid-level double VOLT is to gain the potential benefits of both a bridge and a shunt. The purpose of this paper is to review our experience with this approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Following institutional review board approval (16–275), we retrospectively studied the records of patients who underwent VOLT from May 2015 to August 2017, which were retrieved from a prospectively maintained registry. Demographic and clinical information was collected, including age; sex; body mass index (BMI); cellulitis history; etiology, location, and duration of lymphedema; follow-up time; and recipient site of VOLT. Postoperative complications were recorded. Preoperative and 1-year postoperative lymphoscintigraphy and indocyanine green (ICG) lymphangiography were also evaluated. These outcomes were assessed for all patients who underwent VOLT—whether double or single—to determine the overall complication rate for this donor site. The clinical indication for a double VOLT was global as opposed to focal lymphedema of the limb. All patients were under the care of a certified lymphedema therapist before and after surgery.

Operative Technique: Upper Extremity Lymphedema

A two-team approach is used to harvest the omentum while preparing the axillary recipient site. The omentum is harvested prior to exposing the forearm vessels to ensure there is enough healthy omentum available for two recipient sites. Even in cases without prior abdominal surgery, scarring of the omentum may be present. An open approach is preferred to allow for the use of microsurgical instruments and finer control. The peritoneal cavity is entered through an 8-cm epigastric midline incision. The omentum, transverse colon, and stomach are delivered into the field. The right portion of the omentum is gently dissected from the transverse mesocolon, carefully preserving its blood supply. Dissection is carried up to the greater curvature of the stomach, where the gastroepiploic vessels are clipped and divided. In most cases, the left and right gastroepiploic vessels are in continuity, but in some instances there may be no direct connection.[18] The short gastric vessels are divided, as dissection continues to the proximal right gastroepiploic vessels. There are typically some palpable lymph nodes around the proximal pedicle, which are included as long as the dissection stops a safe distance from the pancreas. ICG angiography is performed to assess perfusion of the flap, as we have observed that about 50% of omentum flaps have regions of ischemia, which should be discarded.

The axillary scar is completely removed through a transverse axillary incision. Scar is excised from the axillary vein and thoracodorsal vessels from the lateral chest wall until normal fat is encountered in the proximal upper arm. If preoperative lymphoscintigraphy demonstrates active lymph nodes in the axilla, a more conservative dissection is performed. Filtered technetium is injected into the affected limb, and a gamma probe is used intraoperatively to avoid compromising the remaining functional lymph nodes.

The forearm recipient site is prepared with a 6- to 8-cm longitudinal incision from the antecubital crease along the ulnar border of the flexor muscle wad. The septum between the brachioradialis and flexor carpi radialis muscles is opened, exposing the radial artery and venae comitantes. The recurrent radial artery branching radially is used for arterial inflow, and either a vena comitans or the cephalic vein is used for venous outflow. The forearm skin is undermined, carefully avoiding sensory nerves, and some subcutaneous fat is removed to allow room for the flap.

The flap is harvested, and the proximal right gastroepiploic vessels are typically anastomosed to the thoracodorsal vessels in the axilla. After the flap is reperfused, a point along the gastroepiploic vessels is selected as the division site for the second flap. Care is taken to respect the angiosome and lymphosome of these segments, and the second flap is harvested. The distal gastroepiploic vein of the revascularized flap is anastomosed to a second recipient vein, commonly the circumflex scapular vein. This restores the normal bidirectional venous drainage of the omentum and addresses potential venous hypertension, which has been observed with this flap.[1] As we gained experience with the VOLT flap, in some cases we observed that there was significant venous hypertension after conventional microanastamosis of the primary artery and vein. This was clinically evident, with almost pulsatile-like flow through the end of the distal gastroepiploic vein. To avoid venous hypertension, we now routinely anastomose the distal gastroepiploic vein to a second recipient vein.[19]

The second portion of the omentum flap is then transferred to the forearm. Arterial anastomosis is usually performed to the radial recurrent artery, and venous anastomosis is performed to a deep vena comitans or to the cephalic vein. A second venous anastomosis is performed, or the entire gastroepiploic vein of the omentum can be used as a venous flow-through flap, replacing a segment of the cephalic vein. Flap angiography using ICG is performed to confirm adequate perfusion, and the skin is closed over closed suction drains at each recipient site. Although the axilla is often used for the proximal omentum, if most of the lymphedema is present in the forearm, it may be preferable to use this lymph node-rich proximal segment in the forearm. Postoperatively, the patient takes sips of clear fluids only until the first passage of flatus, after which a normal diet is given. Two weeks postoperatively, the patient begins compression wrapping and manual lymphatic drainage of the entire limb without restriction by a certified lymphedema therapist. Once the limb has plateaued in volume, the patient is placed in a compression garment.

Operative Technique: Lower Extremity Lymphedema

The omentum is prepared in an identical manner as in the upper extremity. In the thigh, an incision is made along the posterior border of the abductor longus muscle. Dissection through the muscle fascia exposes the gracilis pedicle and profunda artery perforator pedicle, either of which can be exposed for length.[20] In the calf, an 8-cm incision is made directly over the center of the medial gastrocnemius muscle from the popliteal crease downward. Once a perforator is identified, it is traced to the medial sural artery and vein. These vessels are dissected and mobilized. In all of the recipient sites, fat and fascia are removed to accommodate the flap. ICG flap angiography is used to confirm vessel patency and perfusion of the transplant. The patient is out of bed by postoperative day 3, but remains non-weight bearing for 2 weeks with a walker. Because of limited postoperative mobility, 40 mg of subcutaneous enoxaparin is given daily for 1 month to reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism. A certified lymphedema therapist starts compression wrapping of the entire limb 2 weeks postoperatively.

RESULTS

From May 2015 to August 2017, 54 VOLTs were performed in 38 patients. Sixteen of these patients had double VOLT: 12 for upper extremity lymphedema and four for lower extremity lymphedema. Of 12 patients in the double VOLT group with upper extremity lymphedema, 11 had VOLTs to the axilla and forearm and one to the bilateral forearms for primary lymphedema. Of the four patients in the double VOLT group with lower extremity lymphedema, all VOLTs were to the thigh and calf. Bidirectional venous anastomosis was used in eight flaps in five of the patients in the double VOLT group and 11 flaps in eight patients overall.

The demographic and clinical information for the all VOLTs and double VOLT groups is shown in Table I. All patients were female. Among patients in the double VOLT group, the average duration of lymphedema was 3.8 years, and breast cancer was the cause of lymphedema among 62.5%.

Table I:

Demographic and clinical information of patients with lymphedema who underwent double VOLT, as a subgroup of all patients who underwent any VOLT

| Double VOLT (n=16 patients) |

All VOLTs (n=38 patients) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (range) | 55.4 (34–69) | 54.9 (27–72) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (range) | 26.2 (23.2–31.2) | 25.6 (20.2–31.5) |

| Duration of lymphedema (months), mean (range) | 45.3 (5–168) | 38.5 (0–168) |

| Follow-up (months), mean (range) | 7.6 (0.5–18) | 9.6 (0.5–24) |

| Cause of lymphedema | ||

| Breast cancer | 10 (62.5%) | 30 (78.9%) |

| Gynecologic cancer | 2 (12.5%) | 4 (10.5%) |

| Benign lymph node excision | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (2.6%) |

| Melanoma | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (2.6%) |

| Primary lymphedema | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (2.6%) |

| Sarcoma | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (2.6%) |

| Location of lymphedema | ||

| Upper extremity | 12 (75%) | 30 (78.9%) |

| Lower extremity | 4 (25%) | 6 (15.8%) |

| Breast | 0 (0%) | 2 (5.3%) |

| History of cellulitis preoperatively | 9 (56.3%) | 17 (44.7%) |

| Recipient site of VOLT | Total flaps= 32 | Total flaps= 54 |

| Axilla | 11 (34.4%) | 27 (50%) |

| Axilla/breast | 0 (0%) | 2 (3.7%) |

| Forearm | 13 (40.6%) | 15 (27.8%) |

| Thigh/Groin | 4 (12.5%) | 6 (11.1%) |

| Calf | 4 (12.5%) | 4 (7.4%) |

VOLT, vascularized omentum lymphatic transplant

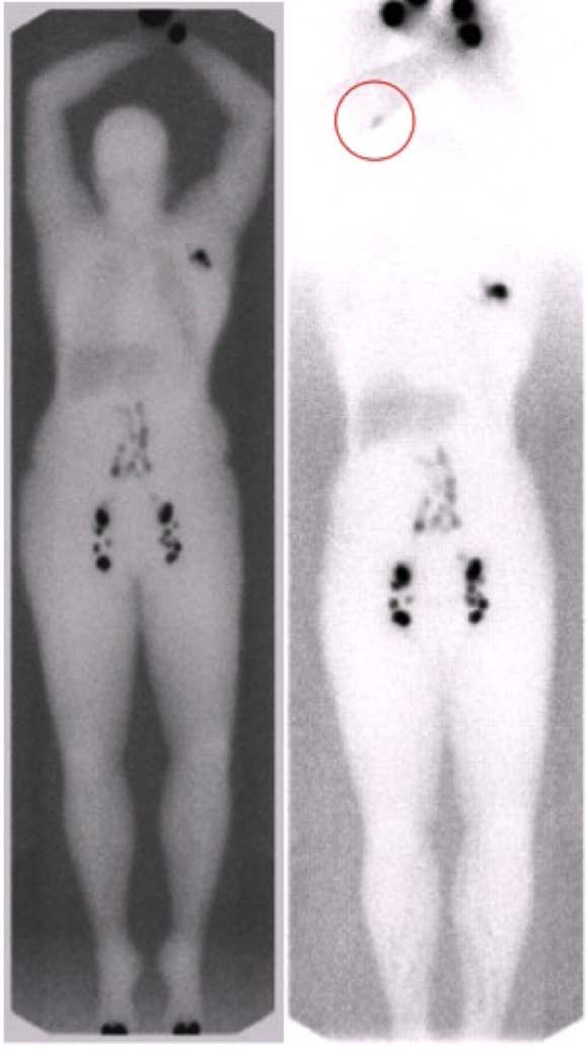

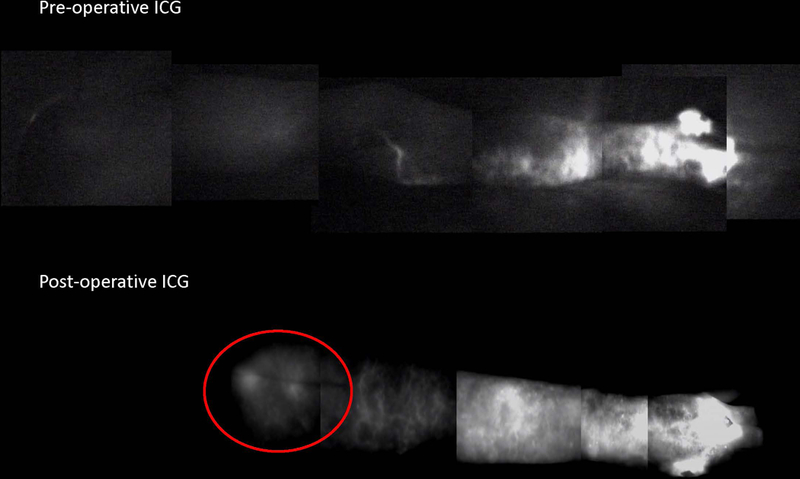

One-year follow up was available for 18 patients who underwent any type of VOLT, including six who underwent a double VOLT. Uptake into transplanted lymphatic tissue was seen on lymphoscintigraphy in three of six (50%) patients in the double VOLT group (Figure 1) and nine of 16 (56.3%) in the overall group. Uptake into the transplanted omentum was seen on ICG lymphangiography in one of five (20%) patients in the double VOLT group (Figure 2) and in four of 13 (30.8%) in the overall group.

Figure 1:

Pre- (left) and 1-year postoperative (right) lymphoscintigraphy after double omentum transfer to the right axilla and right forearm. Postoperative imaging (right) demonstrating uptake into the VOLT in the forearm (red circle). Both pre- and postoperative images were standardized and obtained at 3 hours after injection. VOLT, vascularized omentum lymphatic transplant

Figure 2:

Pre- (upper) and 1-year postoperative (lower) ICG lymphangiography demonstrating flow (red circle) into the transplanted omentum lymph tissue in the proximal forearm postoperatively. ICG, indocyanine green

There were complications in six of 38 patients (Table II), for an overall complication rate of 15.8%. Donor site complications included one patient with transient pancreatitis (2.6%) and two patients with ileus of 4 to 5 days (5.3%), one of whom required a nasogastric tube for 24 hours. Both of these complications occurred in patients who received a single VOLT. Recipient site complications included one flap loss (1.9%) among 54 flaps and two of 38 (3.7%) patients requiring a return to the operating room for suspicion of hematoma. The one late flap loss occurred as a result of a soft-tissue infection in a patient with particularly severe radiation damage and end-stage lymphedema with a severely compromised limb. The two patients who returned to the operating room included one for avulsion of the arterial anastomosis due to activity, which was successfully salvaged, and the other for a negative exploration for suspected hematoma. Preoperatively, patient-reported cellulitis occurred in 17 of 38 (44.7%) patients in the all VOLTs group (Table I). Postoperatively, five of 38 (13.2%) patients in the all VOLTs group had cellulitis of the affected extremity.

Table II:

Complications in patients who underwent double VOLT, as a subgroup of all patients who underwent any VOLT

| Complication | Double VOLT (n=16 patients) |

All VOLTs (n=38 patients) |

|---|---|---|

| Pancreatitis | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.6%) |

| Ileus | 0 (0%) | 2 (5.3%) |

| Hernia | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Small bowel obstruction | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Return to the operating room | 1 (3.1%) | 2 (3.7%) |

| Total flaps= 32 | Total flaps= 54 | |

| Flap loss | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.9%) |

VOLT, vascularized omentum lymphatic transplant

Complications were minimal among the 16 patients in the double VOLT group (Table II), with only one (3.1%) return to the operating room for a hematoma. There were no flap losses and no donor site complications in the double VOLT group. Postoperative appearance is shown in Figures 3 to 7.

Figure 3:

One-year postoperative abdominal scar

Figure 7:

One-year postoperative calf scar

DISCUSSION

The use of a pedicled omentum flap for the treatment of lymphedema was first described 40 years ago.[21] One end of the gastroepiploic pedicle was kept intact, and the omentum was delivered extra-peritoneally into the affected site. This approach resulted in an iatrogenic hernia, which led to some severe complications and limited widespread adoption of this technique.[22,23] The advent of microsurgery has reignited interest in the omentum flap, as this approach would allow transplantation to virtually anywhere in the body and the abdomen to be closed completely.[1–7,24] Although laparoscopic harvest of the omentum has also been described,[1,25] in our experience open harvest through a limited incision is more precise and remains the preferred approach.

Major advantages of the omentum are its large surface area and long, consistent pedicle, which allow it to be split into two flaps for simultaneous transfer into the same limb. The rationale behind this approach is to provide more than one exit for lymph in a limb with poor proximal movement of lymph. We have observed this in our clinic in patients with ICG lymphangiography in which the dye never reaches the axilla or takes a long time to do so. Hung-Chi Chen and colleagues first described splitting the omentum for transfer to the knee and ankle in patients with lower extremity lymphedema and to the elbow and wrist in patients with upper extremity lymphedema.[6] Their early experience of seven patients with follow-up ranging from 8 to 11 months concluded that this is a safe and promising technique. The rationale for distal transfer to the wrist or ankle is that it is the most dependent region of the limb and may be more efficacious.[17] However, distal transfer requires a skin graft at the recipient site, which may be unsightly and unacceptable to some patients. In contrast to a mid-level and distal transplant, the technique described in our study involves a proximal and mid-level transplant in 16 patients. The midlevel recipient site avoids the need for a skin graft, as it is buried and does not cause a noticeable bulge. The proximal component of the transfer also allows the surgeon to remove scar, decompress the axillary vein, and potentially improve shoulder range of motion, if relevant. Currently there are no conclusive data regarding the efficacy of proximal, mid-level, and distal recipient sites.

Postoperative imaging results for patients in the double VOLT group, although limited in number, demonstrated physiologic function in 50% of patients on lymphoscintigraphy and 20% on ICG lymphangiography. However, we have observed clinical improvement of lymphedema in patients who do not have uptake into their transplant on either of these imaging studies. This can be due to a number of factors, including the limited sensitivity of lymphoscintigraphy, the limited depth of visualization of ICG lymphangiography, and the location of the dye injection.

The results in this study of 54 VOLTs in 38 patients suggest that the omentum is a safe option as a donor site for lymphatic transplant. The more commonly cited abdominal complications—including hernia, small-bowel obstruction, and donor site infection, which were reported using a pedicled omentum[22,23] —have not been observed in this series to date. The one episode of transient pancreatitis in our study occurred early in our experience with the omentum, and it was likely related to dissection close to the pancreas in an effort to capture more lymph nodes at the hilum of the gastroepiploic vessels. Our approach has become more conservative, and there have not been any further episodes of pancreatitis. Although 44.7% of patients reported cellulitis of the affected extremity preoperatively, on preliminary review this was reduced to 13.2% of patients postoperatively. Each of the patients with cellulitis postoperatively had been affected preoperatively; further long-term follow-up is needed. The low complication rate in the double VOLT group may reflect the increased experience with this technique, compared with our earlier experience using a single VOLT.

Long-term data are needed to assess the overall clinical outcomes of double VOLT. We are currently recruiting patients for a prospective study comparing vascularized lymph node transplant with conservative treatment to better understand the risks, benefits, and outcomes for patients with lymphedema.

CONCLUSION

The double VOLT is a safe and reliable technique for the treatment of lymphedema. Benefits include the option of treating scar contracture and vein compression at the proximal recipient site and improved cosmesis at the mid-level as opposed to distal recipient site. Prospective study will further refine the outcomes and indications of this procedure.

Figure 4:

One-year postoperative axilla scar

Figure 5:

One-year postoperative forearm scar

Figure 6:

One-year postoperative thigh scar

Synopsis for Table of Contents:

The double vascularized omentum lymphatic transplant (VOLT) is a promising surgical technique for the treatment of lymphedema. Complications and early outcomes of 54 free flaps are reviewed.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 and research grants from the NIH/NCI (R21CA194882) and NIH/NHLBI (R01HL111130). This research was also funded in part through an Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program award.

The authors thank Dagmar Schnau of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center for her editorial assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

Disclosures and Funding Sources: This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 and research grants from the NIH/NCI (R21CA194882) and NIH/NHLBI (R01HL111130). This research was also funded in part though an Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program award.

References:

- 1.Nguyen AT, Suami H, Hanasono MM, et al. Long-term outcomes of the minimally invasive free vascularized omental lymphatic flap for the treatment of lymphedema. J Surg Oncol 2017;115:84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen AT, Suami H. Laparoscopic free omental lymphatic flap for the treatment of lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015;136:114–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lasso JM, Pinilla C, Castellano M. New refinements in greater omentum free flap transfer for severe secondary lymphedema surgical treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2015;3:e387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Attash SM, Al-Sheikh MY. Omental flap for treatment of long standing lymphoedema of the lower limb: can it end the suffering? Report of four cases with review of literatures. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benoit L, Boichot C, Cheynel N, et al. Preventing lymphedema and morbidity with an omentum flap after ilioinguinal lymph node dissection. Ann Surg Oncol 2005;12:793–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciudad P, Manrique OJ, Date S, et al. Double gastroepiploic vascularized lymph node tranfers to middle and distal limb for the treatment of lymphedema. Microsurgery 2017;37:771–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Brien BM, Hickey MJ, Hurley JV, et al. Microsurgical transfer of the greater omentum in the treatment of canine obstructive lymphoedema. Br J Plast Surg 1990;43:440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liebermann-Meffert D The greater omentum. Anatomy, embryology, and surgical applications. Surg Clin North Am 2000;80:275–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meza-Perez S, Randall TD. Immunological functions of the omentum. Trends Immunol 2017;38:526–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimotsuma M, Shields JW, Simpson-Morgan MW, et al. Morpho-physiological function and role of omental milky spots as omentum-associated lymphoid tissue (OALT) in the peritoneal cavity. Lymphology 1993;26:90–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sulo E, Hartiala P, Viitanen T, et al. Risk of donor-site lymphatic vessel dysfunction after microvascular lymph node transfer. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2015;68:551–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massey MF, Gupta DK. The incidence of donor-site morbidity after transverse cervical artery vascularized lymph node transfers: the need for a lymphatic surgery national registry. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015;135:939e–940e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pons G, Masia J, Loschi P, et al. A case of donor-site lymphoedema after lymph node-superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator flap transfer. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2014;67:119–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carreras MC, Clara Franco M, D PC, et al. Cell H2O2 steady-state concentration and mitochondrial nitric oxide. Methods Enzymol 2005;396:399–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dayan JH, Dayan E, Smith ML. Reverse lymphatic mapping: a new technique for maximizing safety in vascularized lymph node transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015;135:277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becker C, Vasile JV, Levine JL, et al. Microlymphatic surgery for the treatment of iatrogenic lymphedema. Clin Plast Surg 2012;39:385–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng MH, Huang JJ, Wu CW, et al. The mechanism of vascularized lymph node transfer for lymphedema: natural lymphaticovenous drainage. Plast Reconstr Surg 2014;133:192e–198e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumagai Y, Ishiguro T, Haga N, et al. Hemodynamics of the reconstructed gastric tube during esophagectomy: assessment of outcomes with indocyanine green fluorescence. World J Surg 2014;38:138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dayan JH, Voineskos S, Verma R, Mehrara BJ. Managing venous hypertension in vascularizedomentum lymphatic transplant: restoring bi-directional venous drainage. Plast Reconstr Surg 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson JA, Mehrara BH, Dayan JH. Vascularized lymph node transfer to the profunda artery perforator pedicle: a reliable proximal recipient vessel option in the medial thigh. Plast Reconstr Surg 2017;140:366e–367e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldsmith HS, De los Santos R. Omental transposition for the treatment of chronic lymphedema. Rev Surg 1966;23:303–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldsmith HS. Long term evaluation of omental transposition for chronic lymphedema. Ann Surg 1974;180:847–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suami H, Chang DW. Overview of surgical treatments for breast cancer-related lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010;126:1853–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egorov YS, Abalmasov KG, Ivanov VV, et al. Autotransplantation of the greater omentum in the treatment of chronic lymphedema. Lymphology 1994;27:137–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston ME, Socas J, Hunter JL, Ceppa EP. Laparoscopic gastroepiploic lymphovascular pedicle harvesting for the treatment of extremity lymphedema: a novel technique. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2017;27:e40–e43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]