SUMMARY

Homogeneous antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) that use a highly reactive buried lysine (Lys) residue embedded in a dual variable domain (DVD)-IgG1 format can be assembled with high precision and efficiency under mild conditions. Here we show that replacing the Lys with an arginine (Arg) residue affords an orthogonal ADC assembly that is site-selective and stable. X-ray crystallography confirmed the location of the reactive Arg residue at the bottom of a deep pocket. As the Lys-to-Arg mutation is confined to a single residue in the heavy chain of the DVD-IgG1, heterodimeric assemblies that combine a buried Lys in one arm, a buried Arg in the other arm, and identical light chains are readily assembled. Furthermore, the orthogonal conjugation chemistry enables the loading of heterodimeric DVD-IgG1s with two different cargos in a one-pot reaction and thus affords a convenient platform for dual-warhead ADCs and other multifaceted antibody conjugates.

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Hwang, Nilchan et al. convert a reactive lysine in a catalytic antibody to a reactive arginine, reveal its location by X-ray crystallography, and utilize the engineered antibody for site-selective antibody functionalization including its pairing with the original antibody for orthogonal dual cargo conjugation.

INTRODUCTION

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) are among the most promising next-generation monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapeutics for cancer therapy (Beck et al., 2017). ADCs enable the targeted delivery of a highly cytotoxic drug for selective (as opposed to systemic) chemotherapy, resulting in lower toxicity toward healthy cells and tissues (Chari et al., 2014; Lambert and Berkenblit, 2018; Senter, 2009). In addition to four FDA-approved ADCs, >60 ADCs are currently under investigation in clinical trials (Beck et al., 2017). Despite this success, the growing pipeline of ADCs also faces challenges. While the therapeutic index, i.e. the ratio of maximum tolerated dose and minimum effective dose, is generally higher for ADCs compared to chemotherapy (Panowski et al., 2014), ADCs have encountered on-target and off-target toxicities (Donaghy, 2016). However, with the rapidly growing knowledge of the four principle components of ADCs, i.e. mAb, linker, drug, and target (Beck et al., 2017), suitable combinations that afford high therapeutic indices provide exceptional opportunities for cancer therapy.

The four FDA-approved ADCs and the vast majority of ADCs in the clinical and preclinical pipeline randomly conjugate the drug to either surface lysine (Lys) or hinge cysteine (Cys) residues of the antibody, yielding complex mixtures of molecular species with varying drug-to-antibody ratios (DARs), pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics. Addressing this heterogeneity, the field is moving toward homogeneous ADCs that, ideally, consist of a single molecular species with defined pharmacological properties (Panowski et al., 2014). Thus, homogeneous ADCs are highly defined compositions of mAb, linker, and drug, and typically have DARs of 2 or 4. The precise assembly required to make homogeneous ADCs calls for uniquely reactive amino acid or carbohydrate residues in the mAb for drug attachment. We recently developed a homogeneous ADC platform that utilizes the highly reactive buried Lys residue of the catalytic antibody h38C2 (Rader et al., 2003b; Wagner et al., 1995) for precise, efficient, and stable drug attachment (Nanna et al., 2017). The platform is built on a dual variable domain (DVD)-IgG1 format (Wu et al., 2007) with the variable fragments (Fvs) of h38C2 and a cancer cell-targeting mAb as inner and outer Fvs, respectively. An electrophilic β-lactam hapten appended to the drug selectively reacts with the nucleophilic Lys residue in each of the two arms of the DVD-IgG1 to form a stable amide bond to generate ADCs with a DAR of 2. Conjugation efficiency correlates with the loss of catalytic activity of the DVD-IgG1. Our homogeneous ADC platform is inherently modular which we demonstrated by preparing DVDs against HER2 in breast cancer, CD138 in multiple myeloma, and CD79B in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, while retaining h38C2 as the inner Fv for conjugation to a β-lactam hapten derivative of the highly potent tubulin inhibitor monomethyl auristatin F (MMAF). All three DVD-IgG1/MMAF conjugates revealed subnanomolar and strictly target-dependent cytotoxicity in vitro. The HER2-targeting DVD-IgG1/MMAF conjugate was highly active in vivo, outperforming the FDA-approved ADC ado-trastuzumab emtansine in an orthotopic mouse xenograft model of human breast cancer (Nanna et al., 2017).

Here we expand the concept of hapten-driven conjugation to arginine (Arg) which is, to the best of our knowledge, the first site-selective Arg conjugation technology. Furthermore, combining a buried Lys residue with a buried Arg residue enables orthogonal one-pot assembly of site-selective ADCs carrying two different cargos.

RESULTS

Generation and Crystallization of h38C2_Arg Fab

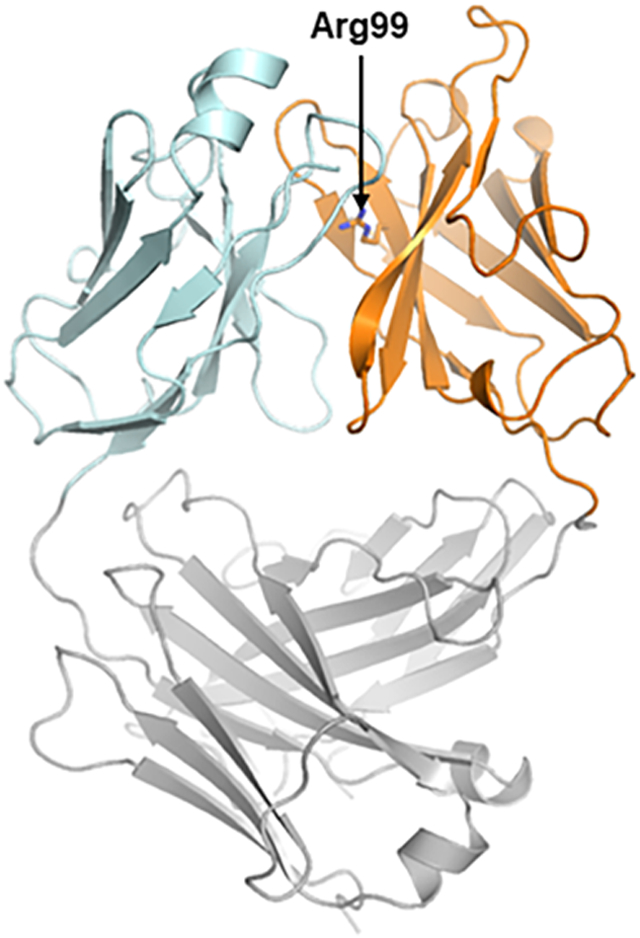

Catalytic antibody 38C2, which was generated by reactive immunization of mice using an aromatic hapten with β-diketone functionality (Barbas et al., 1997; Wagner et al., 1995), and its humanized version h38C2 (Rader et al., 2003b) contain a highly reactive buried lysine residue at position 99 (which is position 93 by Kabat numbering) in the variable heavy chain domain (VH) (Karlstrom et al., 2000). Due to its location at the bottom of a deep hydrophobic pocket, protonation of the ε-amino group of Lys99 is disfavored, thereby reducing its pKa and increasing its nucleophilicity. The unique reactivity of Lys99 is essential for the aldolase activity of the mAbs and has been utilized for reversible and irreversible covalent conjugation to β-diketone and β-lactam hapten derivatives, respectively, to afford highly homogeneous chemically programmed antibodies and ADCs (Figure 1A) (Nanna et al., 2017; Rader, 2014). Hypothesizing that substituting Lys99 with other nucleophilic amino acid residues would afford orthogonal conjugation chemistry, we cloned, expressed, and purified a Lys99Arg mutant of h38C2 (termed h38C2_Arg) in Fab format and determined its three-dimensional structure by X-ray crystallography at 2.4-Å resolution (Figure 2A and Table S1). Similar to Lys99 in the parental antibody, Arg99 was positioned at the bottom of a deep pocket filled with one sulfate ion and eight water molecules (Figure 2B and S1). An overlay with the previously crystallized catalytic antibody 33F12 (Barbas et al., 1997), which is closely related to 38C2 (Karlstrom et al., 2000), confirmed that the three-dimensional structures were highly conserved with disparities confined to the Lys99Arg mutation and a slight tilt of Tyr101 at the rim of the pocket (Figure 2C).

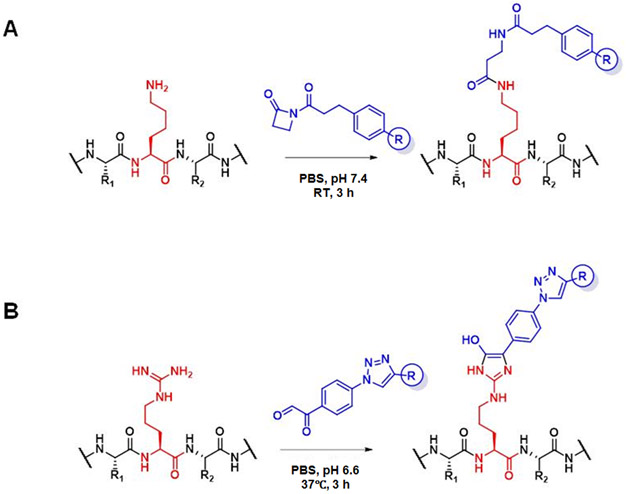

Figure 1. Conjugation of Lys and Arg.

(A) Hapten-driven covalent conjugation of a β-lactam-hapten derivative to the reactive Lys residue of mAb h38C2_Lys. The side chains of the flanking Cys and Thr residues are shown as R1 and R2, respectively.

(B) Hapten-driven covalent conjugation of a phenylglyoxal-triazole derivative to the reactive Arg residue of mAb 38C2_Arg.

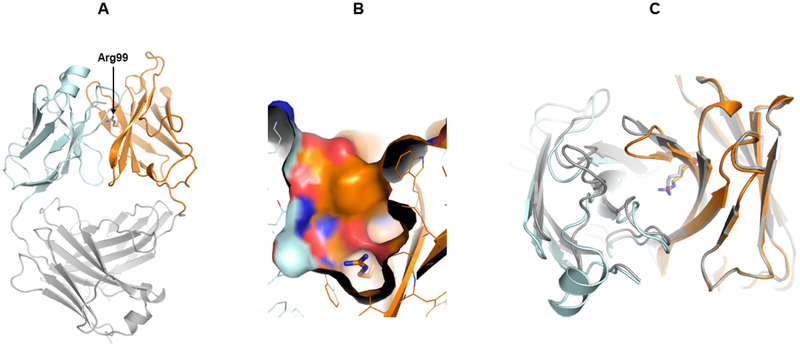

Figure 2. Crystal Structure of h38C2_Arg Fab.

(A) The three-dimensional structure of the Lys99Arg mutant of h38C2 in Fab format was determined by X-ray crystallography at 2.4-Å resolution. In this ribbon diagram, the variable domains of light (Vκ) and heavy chain (VH) are shown in cyan and orange, respectively, and the constant domains (Cκ and CH1) in gray. VH’s Arg99 (arrow) is located at the bottom of a deep pocket between Vκ and VH.

(B) Surface rendering model of the pocket of h38C2_Arg Fab. The side chain of Arg99 with its guanidino group is shown at the bottom.

(C) Top view overlay of the ribbon diagrams of h38C2_Arg (cyan/orange) and 33F12 Fab (gray; PDB: 1AXT) (Barbas et al., 1997). The presence of the sulfate ion in the pocket (Figure S1) pulls β-strand G’ of h38C2_Arg Fab’s VH toward the pocket. This structural change reduces the cavity volume to ~300 Å3 compared to ~450 Å3 for 33F12. See also Figure S1 and Table S1.

Orthogonal Conjugation Chemistry of h38C2_Arg

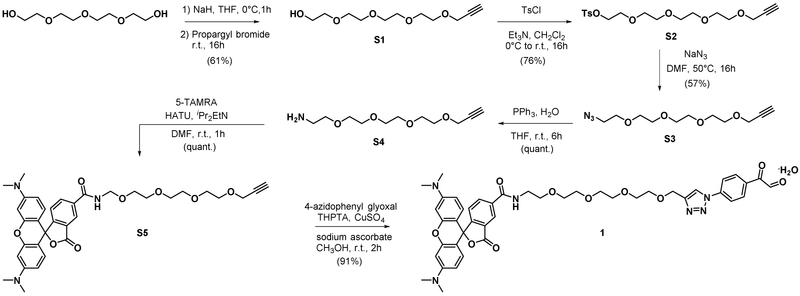

The preservation of the deep pocket suggested that similar to buried Lys99, buried Arg99 would have unique reactivity that could be utilized for site-specific conjugation. To test this, we first cloned, expressed, and purified a DVD-Fab with the outer Fv derived from humanized anti-human HER2 mAb trastuzumab (Herceptin®) and the inner Fv derived from h38C2_Arg (Figure 3A). A corresponding DVD-Fab with the inner Fv derived from parental h38C2 (i.e., the Fab fragment of our previously reported DVD-IgG1) (Nanna et al., 2017) was generated for comparison. Whereas the two DVD-Fabs were indistinguishable with respect to yield and purity, they revealed the expected dramatic difference in catalytic activity. The DVD-Fab based on h38C2_Arg had complete loss of retro-aldol activity (List et al., 1998) that is characteristic of the Lys99 containing aldolase antibodies 33F12, 38C2, and h38C2 (Figure 3B). To probe Arg99 for site-specific conjugation, we synthesized a phenylglyoxal derivative of tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) (compound 1; Figure 4 and STAR Methods). Phenylglyoxal is known to react with the guanidino group of Arg residues under mild conditions (Takahashi, 1968), resulting in the formation of a stable hydroxyimidazole ring (Figure 1B). Recently, this reaction has been utilized for click chemistry bioconjugations using commercially available 4-azido-phenylglyoxal (Dovgan et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2016). Covalent conjugation of compound 1 to h38C2_Arg DVD-Fab following incubation for 3 h at 37°C in 50 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaHCO3 (pH 6.0) at different molar ratios was analyzed by SDS-PAGE with blue light visualization (Figure 3C). At 5- and 10-fold molar excess of compound 1, a strong fluorescent band at 70 kDa was detected whereas an equimolar amount only resulted in weak staining. Although parental h38C2_Lys DVD-Fab was only weakly stained under the same conditions, suggesting preferential covalent conjugation of compound 1 to Arg99, it revealed a strong fluorescent band at 70 kDa following incubation with 5- and 10-fold molar excess of a β-lactam hapten derivative of TAMRA (compound 3; Figure 4 and STAR Methods). Furthermore, preincubation of h38C2_Arg DVD-Fab with a non-fluorescent β-lactam hapten (compound 2; Figure 4 and STAR Methods) at 10-fold molar excess did not block covalent conjugation of compound 1, demonstrating orthogonal conjugation chemistry of Arg99 and Lys99 (Figure 3D).

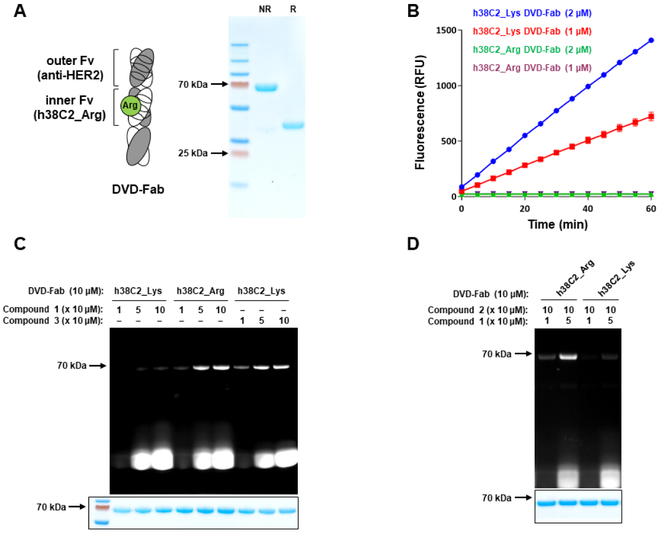

Figure 3. Generation and Characterization of an h38C2_Arg-Based DVD-Fab.

(A) The DVD-Fab is composed of variable domains of trastuzumab (outer Fv) and h38C2 mutant Lys99Arg (inner Fv with green circle) and constant domains. Inner and outer variable domains of both light chain (white) and heavy chain fragment (gray) are connected by a short spacer (ASTKGP). Following purification from the supernatant of transiently transfected Expi293F cells by Protein A affinity chromatography, the DVD-Fab revealed the expected ~70-kDa band by nonreducing (NR) and the expected ~35-kDa bands by reducing (R) SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining.

(B) The catalytic activity of parental (h38C2_Lys) and mutated (h38C2_Arg) DVD-Fab at 1 μM and 2 μM was measured using the retro-aldol conversion of methodol to a detectable fluorescent aldehyde (RFU, relative fluorescent units) and acetone. Mean (±) SD values of triplicates were plotted.

(C) DVD-Fabs with h38C2_Arg or h38C2_Lys were incubated with 1, 5, and 10 equivalents of a phenylglyoxal derivative of TAMRA (compound 1; Figure 4) or a β-lactam-hapten derivative of TAMRA (compound 3; Figure 4) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by fluorescent imaging and Coomassie staining.

(D) DVD-Fabs with h38C2_Arg or h38C2_Lys were pre-incubated with 10 equivalents of a β-lactam-hapten-azide (compound 2; Figure 4) followed by incubation with 1 and 5 equivalents of compound 1. See also Figure S2 and S4.

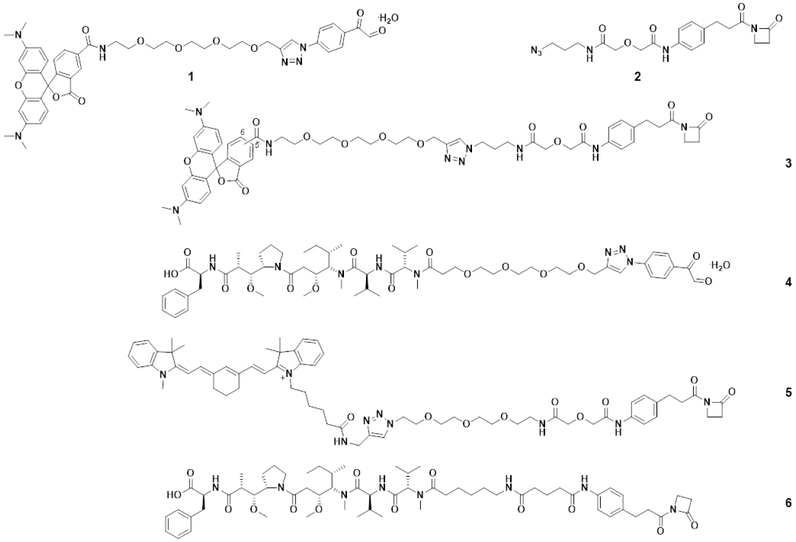

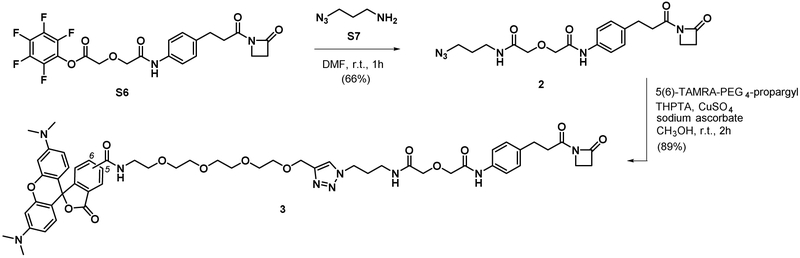

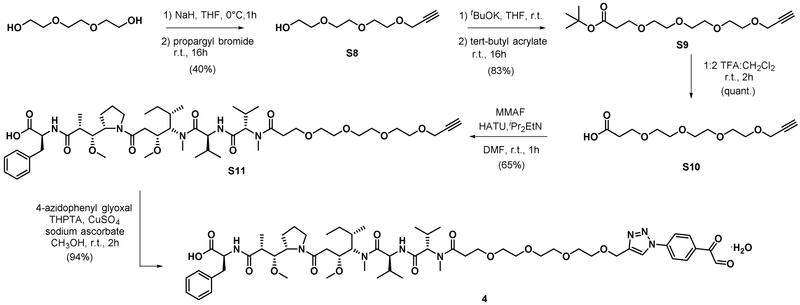

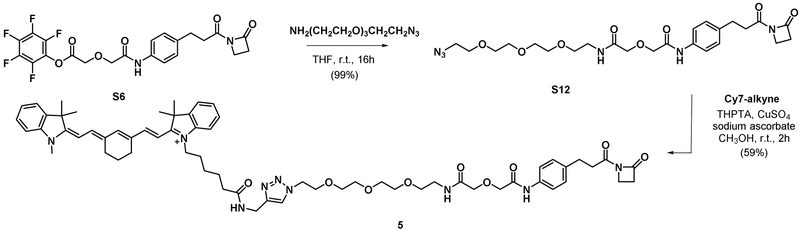

Figure 4. Phenylglyoxal and β-Lactam Derivatives.

Compounds 1 and 3 are phenylglyoxal and β-lactam-hapten derivatives, respectively, of the red fluorescent dye TAMRA. Compound 2 is a β-lactam-hapten-azide derivative. Compounds 4 and 6 are phenylglyoxal and β-lactam-hapten derivatives, respectively, of the cytotoxic drug MMAF. Compound 5 is a β-lactam-hapten derivative of the near infrared fluorescent dye Cy7.

Next, we analyzed h38C2_Arg DVD-Fab by mass spectrometry (MS). The unconjugated antibody revealed an observed molecular weight (MW) of 73,836 Da compared to an expected MW of 73,820 Da (Figure S2A-C). Following incubation with a 5-fold molar excess of compound 1, the observed MW increased by 803 Da, which corresponds to the expected MW increase from the formation of a stable hydroxyimidazole ring at Arg99. The ratio of conjugated to unconjugated antibody was ~8.5:1.5. The signal of the unconjugated antibody decreased when the molar excess of compound 1 was increased to 10-fold. However, a new signal corresponding to an antibody conjugate with two modified Arg residues appeared at a ~8.3:1.7 ratio of single to double conjugated antibody.

To confirm Arg99 as the conjugation site, untreated and phenylglyoxal-treated h38C2_Arg Fab was digested with pepsin and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). We achieved >90% amino acid sequence coverage of both light and heavy chain sequences. A hexapeptide, Tyr-Cys-Arg-Thr-Tyr-Phe, with a 116-Da modification on the Arg was detected for phenylglyoxal-treated but not untreated h38C2_Arg Fab (Figure S2D-G). This hexapeptide matched the amino acid sequence surrounding Arg99 and was the only detectable modified peptide with a higher relative abundance than the corresponding unmodified peptide, thus validating site-selective Arg99 modification. The 116-Da mass-over-charge ratio (m/z) shift on the Arg residue is in agreement with the formation of a hydroxyimidazole ring between the guanidino group of Arg and phenylglyoxal (Figure 1B). Although additional modified heavy and light chain peptides were detectable in this experiment, they had a much lower relative abundance than the corresponding unmodified peptides.

To assess the stability of the Arg::phenylglyoxal adduct, h38C2_Arg DVD-Fab was conjugated to compound 1 and incubated with human plasma for up to 10 days at 37°C. Analysis after 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, 96, 144, 192, and 240 h revealed high stability of the conjugate with no significant decay after 10 days (Figure S3).

Generation and Characterization of ADCs Based on h38C2_Arg

With conjugation efficiency, selectivity, and stability established, we next investigated the suitability of Arg::phenylglyoxal adducts for the assembly of site-selective ADCs. A phenylglyoxal derivative of MMAF (compound 4; Figure 4 and STAR Methods) was synthesized analogous to the β-lactam hapten derivative of MMAF (compound 6; Figure 4 and STAR Methods) (Nanna et al., 2017) we used for assembling homogeneous ADCs that were based on parental h38C2_Lys. Employing the same conditions as for compound 1, the h38C2_Arg DVD-Fab was incubated with compound 4 and the conjugate was confirmed by MS, revealing an observed mass of 74,970 Da and 73,837 Da for the conjugated and unconjugated antibody, respectively, at ~8.5:1.5 ratio (Figure S4A). Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) further showed that the MMAF-conjugated h38C2_Lys99Arg DVD-Fab was free of aggregates (Figure S4B).

The ADC in DVD-Fab format was cytotoxic to HER2-positive human SK-BR-3 breast cancer cells at subnanomolar concentrations but not to HER2-negative human MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells at up to 100 nM, the highest concentration tested (Figure S4C). Importantly, the Arg99-based ADC (IC50 = 0.85 nM) revealed similar potency and selectivity when compared to the Lys99-based ADC (IC50 = 0.64 nM) assembled from parental h38C2_Lys DVD-Fab and compound 6. The ability of the Arg99-based ADC to eradicate target cells as efficiently as the Lys99-based ADC suggested that binding, internalization, endosomal trafficking, lysosomal degradation, and drug release proceed with similar efficiency or at least give the same net result. Comparing both unconjugated and MMAF-conjugated h38C2_Arg and h38C2_Lys DVD-Fab for binding to HER2 by surface plasmon resonance, revealed highly conserved kinetic and thermodynamic parameters (Figure S5) which were in good agreement with published data (Bostrom et al., 2011) and confirmed that neither Arg99Lys mutation nor drug conjugation to the inner Fv interferes with outer Fv binding.

The potency of the MMAF-conjugated h38C2_Arg99 DVD-Fab prompted us to generate the corresponding ADC in DVD-IgG1 format (Figure 5A). Analysis of the ADC by MS revealed two major peaks, one corresponding to the unconjugated light chain and the other corresponding to the heavy chain with a single MMAF molecule (Figure S7A and B). Minor peaks corresponding to the unconjugated heavy chain (15% of the major peak of the heavy chain) and the heavy chain with two MMAF molecules (0.5%) were also detected, suggesting an overall DAR of ~1.7. As expected, the Arg99-based ADC in DVD-IgG1 format revealed essentially the same potency and selectivity as the Lys99-based ADC in DVD-IgG1 format (Figure 5C).

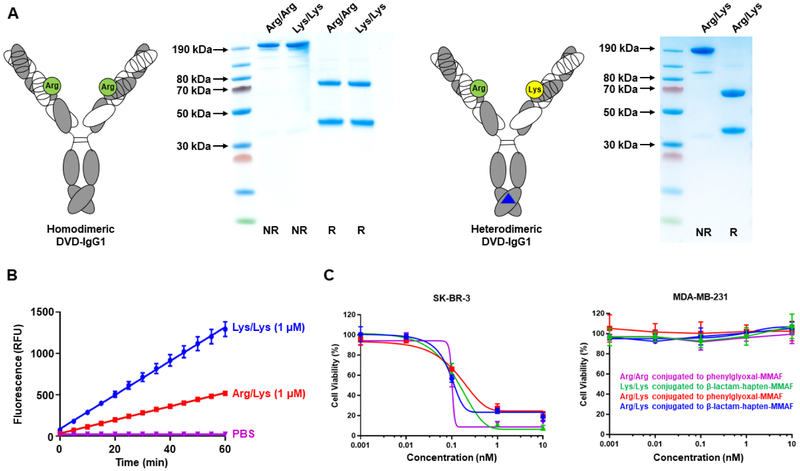

Figure 5. Generation and Characterization of Homodimeric and Heterodimeric DVD-IgG1s.

(A) Analogous to the DVD-Fab, the homodimeric DVD-IgG1 (left) is composed of variable domains of trastuzumab (outer Fv) and parental h38C2 or h38C2 mutant Lys99Arg (inner Fv with green circle) and constant domains. Inner and outer variable domains of both light chain (white) and heavy chain fragment (gray) are connected by a short spacer (ASTKGP). The heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 (right) combines a parental h38C2 inner Fv in one arm with h38C2 mutant Lys99Arg in the other arm and utilizes knobs-into-holes mutations (blue triangle) for heavy chain heterodimerization. Following purification from the supernatant of transiently transfected Expi293F cells by Protein A affinity chromatography, the h38C2_Arg-based DVD-IgG1 (“Arg/Arg”) was indistinguishable from the previously described h38C2_Lys-based DVD-IgG1 (“Lys/Lys”), revealing the expected ~200-kDa band by nonreducing (NR) and the expected ~65-kDa and ~35-kDa bands by reducing (R) SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. The heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 (“Arg/Lys”) revealed the same bands.

(B) The catalytic activity of homodimeric Lys/Lys and heterodimeric Arg/Lys DVD-IgG1 at 1 μM was measured using the retro-aldol conversion of methodol to a detectable fluorescent aldehyde (RFU, relative fluorescent units) and acetone. Mean (±) SD values of triplicates were plotted.

(C) Cytotoxicity of the two different homodimeric Lys/Lys and Arg/Arg and the heterodimeric Arg/Lys DVD-IgG1 after conjugation to β-lactam-hapten-MMAF (compound 6) or phenylglyoxal-MMAF (compound 4) following incubation with HER2+ SK-BR-3 and HER2– MDA-MB-231 cells for 72 h at 37°C. See also Figure S6.

Generation and Characterization of Heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 that Combine h38C2_Lys and h38C2_Arg

We next set out to utilize the orthogonality of Arg::phenylglyoxal and Lys:β-lactam conjugation by combining h38C2_Arg and h38C2_Lys in one DVD-IgG1. Notably, this assembly involves two different heavy chains and two identical light chains, enabling the utilization of knobs-into-holes mutations for heavy chain heterodimerization (Merchant et al., 1998) (Figure 5A). The heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 was expressed and purified in comparable quality and quantity as the homodimeric Arg99-based DVD-IgG1 (Figure 5A) and revealed roughly the expected ~50% reduction in catalytic activity compared to the Lys99-based DVD-IgG1 (Figure 5B). Conjugation of either phenylglyoxal or β-lactam hapten derivative of MMAF (compounds 4 and 6, respectively) to the heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 yielded DAR ≈ 1 ADCs with high potency and selectivity albeit generally higher IC50 values than the DAR ≈ 2 ADCs based on the corresponding homodimeric DVD-IgG1. We measured IC50 values of 0.53 nM vs. 0.39 nM (DAR ≈ 1 vs. DAR ≈ 2 for phenylglyoxal) and 0.60 nM vs. 0.37 nM (DAR ≈ 1 vs. DAR ≈ 2 for β-lactam) with SK-BR-3 cells; 9.9 nM vs. 0.7 nM (DAR ≈ 1 vs. DAR ≈ 2 for phenylglyoxal) and 10 nM vs. 0.33 nM (DAR ≈ 1 vs. DAR ≈ 2 for β-lactam) with KPL-4 cells; and 1.1 vs. 1.3 nM (DAR ≈ 1 vs. DAR ≈ 2 for phenylglyoxal) and 1.2 nM vs. 0.75 nM (DAR ≈ 1 vs. DAR ≈ 2 for β-lactam) with BT-474 cells (Figure 5C and Figure S6).

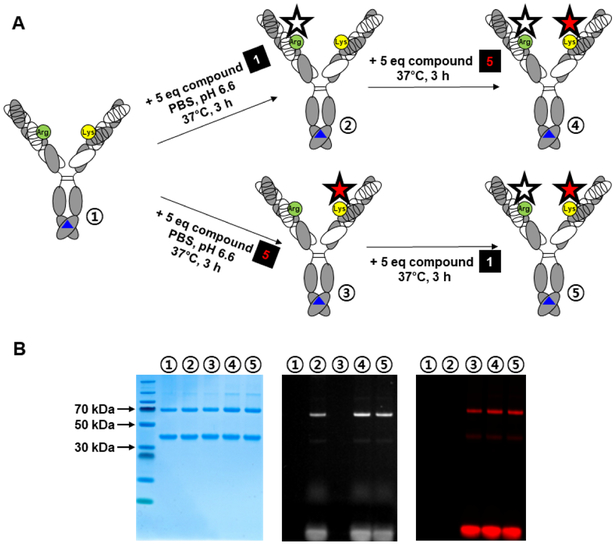

To test whether the orthogonal conjugation chemistry of h38C2_Arg and h38C2_Lys permits one-pot labeling of the heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 with two different cargos, we combined the phenylglyoxal derivative of TAMRA (compound 1) with a β-lactam hapten derivative of the near infrared fluorescent dye Cy7 (compound 5; Figure 4 and STAR Methods). The two dyes were sequentially conjugated to the heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 without intermittent purification or buffer exchange steps (Figure 6A). Regardless of the order of conjugation, the one-pot reactions yielded dual labeled heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 of the same quality and quantity. Using reducing SDS-PAGE, both TAMRA and Cy7 fluorescence were found to be largely confined to the heavy chain as expected for site-selective conjugation to h38C2_Arg and h38C2_Lys, respectively (Figure 6B). We next used the same one-pot assembly for sequential conjugation of the phenylglyoxal derivative of TAMRA (compound 1) and the β-lactam hapten derivative of MMAF (compound 6). MS confirmed the dual labeled heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 with a single TAMRA and a single MMAF molecule as the main product although MMAF-labeled heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 without TAMRA molecule was also prominent (Figure S7C and D). Notably, simultaneous rather than sequential conjugation of compound 1 and compound 5 delivered the dual labeled heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 with similar conjugation efficiency according to MS (Figure S7E).

Figure 6. One-Pot Assembly of Heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 with Two Different Cargos.

(A) Scheme of orthogonal labeling of the heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 (green circle, Arg; yellow circle, Lys; blue triangle, knobs-into-holes mutations) with phenylglyoxal-TAMRA (compound 1, white star) and β-lactam-hapten-Cy7 (compound 5, red star). Sequential conjugation of the two fluorescent dyes at the indicated conditions was conducted without intermittent purification or buffer exchange steps.

(B) Unconjugated heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 ① and conjugates ②, ③, ④, and ⑤ were analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE followed by TAMRA (middle) and Cy7 (right) fluorescent imaging and Coomassie staining (left). See also Figure S7.

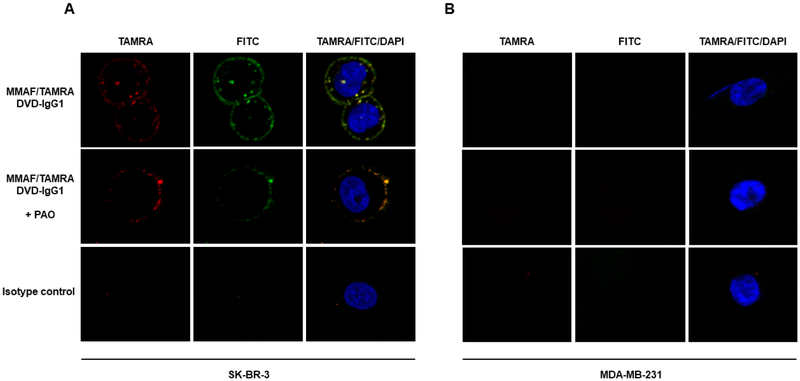

Dual labeling enables the generation of fluorescent ADCs that can be traced directly during internalization and trafficking. To investigate this utility, we incubated HER2-positive SK-BR-3 (Figure 7A) and HER2-negative MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure 7B) with the MMAF/TAMRA-labeled heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 for 4 h at 37°C in the absence and presence of endocytosis inhibitor phenylarsine oxide (PAO) and subsequently analyzed the cells by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Endosomal TAMRA fluorescence was only observed for SK-BR-3 cells and in the absence of PAO, suggesting HER2-mediated internalization and trafficking. Simultaneous staining of the heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 carrier with FITC-conjugated goat anti-human IgG F(ab’)2 polyclonal antibodies revealed strict colocalization with TAMRA fluorescence, suggesting that the endosomes contained an intact fluorescent ADC. No TAMRA and FITC fluorescence was detected with an h38C2_Lys-based and compound 3-labeled homodimeric DVD-IgG1 in which the outer Fv derived from trastuzumab was replaced with an isotype control outer Fv.

Figure 7. Internalization and Trafficking of Heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 with Two Different Cargos.

HER2-positive SK-BR-3 cells (A) and HER2-negative MDA-MB-231 cells (B) were incubated with the MMAF (via Lys) and TAMRA (via Arg)-labeled HER2-targeting heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 for 4 h at 37°C in the absence (top panel) and presence (middle panel) of endocytosis inhibitor phenylarsine oxide (PAO). The isotype control (lower panel) is a ROR2-targeting homodimeric DVD-IgG1 conjugated to TAMRA (via Lys). After the incubation, the cells were washed, fixed, blocked, permeabilized, incubated with FITC-conjugated goat anti-human IgG F(ab’)2 polyclonal antibodies, washed, stained with DAPI, and washed again before their analysis by confocal fluorescence microscopy.

DISCUSSION

The ability to selectively modify two buried Lys residues in the presence of >100 Lys residues in the DVD-IgG1 molecule by hapten-driven conjugation (Nanna et al., 2017) inspired us to extend this concept to site-specific Arg conjugation. We first used X-ray crystallography to show that the buried Lys residue can be replaced with a buried Arg residue without impairing the configuration of the deep pocket. Phenylglyoxal derivatives, which form a hydroxyimidazole ring with the guanidino group of Arg, selectively, efficiently, and stably modified the buried Arg residue(s) in both DVD-Fab and DVD-IgG1 formats. HER2-targeting ADCs based on Lys99 and Arg99 conjugation of MMAF were indistinguishable with respect to cytotoxicity in vitro. The orthogonal conjugation chemistry of Lys:β-lactam and Arg::glyoxal enabled the simultaneous or sequential one-pot assembly of site-selective antibody conjugates with dual cargos.

In the concept of hapten-driven covalent conjugation, a hapten that binds to a haptenbinding site of an antibody brings an electrophilic functionality in close proximity to a nucleophilic amino acid residue to trigger the formation of a covalent bond. Due to the high affinity and specificity of the antibody-hapten interaction, the conjugation can be carried out at low molar hapten:antibody ratios with minimal modification of other amino acid residues, thus ensuing homogeneous antibody conjugates. The phenylglyoxal functionality structurally resembles mAb 38C2’s imprinting aromatic hapten with β-diketone functionality (Barbas et al., 1997; Wagner et al., 1995) and can be considered a hapten-like electrophile. We are currently synthesizing alternative hapten-like electrophiles to increase the ~85% efficiency of site-selective h38C2_Arg conjugation.

Multifaceted antibody conjugates that can be assembled with high precision, efficiency, and stability have broad utility in the detection and treatment of cancer and other diseases. For example, ADCs with multiple warheads could address differential drug sensitivities of a heterogeneous target cell population and thereby overcome resistance. While this has been recognized for the therapy of solid malignancies with substantial intratumor heterogeneity (Marusyk et al., 2012; McGranahan and Swanton, 2015), the generation and assessment of ADCs with multiple warheads has been limited by suitable orthogonal conjugation strategies. Our approach of a knobs-into-holes-based heterodimerization of two heavy chains that only differ by one amino acid in their DVD portion and pair with a common light chain to form two orthogonal deep pockets for Lys and Arg conjugation affords a robust and elegant strategy for assembly of components that on their own have been vetted for large scale manufacturing and entered clinical trials (Gu and Ghayur, 2012; Rader, 2014). A previous in silico analysis we conducted did not reveal an increased immunogenicity risk for h38C2_Lys-based DVD-ADCs (Nanna et al., 2017). As part of the same study, we analyzed the substitution of Lys99 with all canonical amino acids and did not find an increased immunogenicity risk for the Lys99Arg mutation.

In addition to clinical applications, site-selective antibody conjugates carrying dual cargos are useful for basic and applied research (Adumeau et al., 2018; Bruins et al., 2018; Levengood et al., 2017; Li et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2016). For example, analogous to previous studies (Kulkarni et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2018; Maruani et al., 2015), we combined a cytotoxic drug and a fluorophore to directly track ADC internalization and trafficking by confocal microscopy. Afforded by the modular design of the heterodimeric DVD-IgG1, this study can be expanded to a panel of ADCs with different outer Fv domains that bind to different epitopes of a cell surface antigen or that bind the same epitope with different affinities. Alternatively, different linker-drug compositions can be compared with respect to their impact on intracellular delivery. Such studies are not limited to ADCs but can be broadened to other warhead delivery settings, such as radioimmunotherapy (Green and Press, 2017), photoimmunotherapy (Mitsunaga et al., 2011), and siRNA delivery (Lu et al., 2013). Furthermore, orthogonal utilization of h38C2_Lys and h38C2_Arg can be applied to the concept of chemically programmed antibodies and bispecific antibodies (Rader, 2014). Here, mAb h38C2 is used to endow a small molecule that binds to a cell surface receptor with long circulatory half-life and effector functions (Rader et al., 2003a; Walseng et al., 2016). Simultaneous chemical programming with two different small molecules for engaging two different cell surface receptors on cancer cells could improve the avidity and specificity, and thereby the potency and safety of chemically programmed antibodies.

Selective conjugation to the buried Lys and Arg residues depends on the structural integrity of the deep pocket in physiological conditions. Although not addressed experimentally in the current study, it is thus conceivable that our approach is more suitable for hydrophilic cargos that can be dissolved in aqueous buffers as opposed to hydrophobic cargos that require the presence of organic solvents. Given the emergence of highly potent hydrophilic payloads, such as α-amanitin (Liu et al., 2015), PNU-159682 (Yu et al., 2015), and hydrophobic drugs conjugated to polymers (Yurkovetskiy et al., 2015), as well as the development of hydrophilic linkers that were shown to improve the therapeutic index of ADCs (Lyon et al., 2015), our method is compatible with state-of-the-art ADC components, enabling precise, efficient, and stable one-pot assembly in mild conditions.

STAR ★ METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Christoph Rader (crader@scripps.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell Lines

Human breast cancer cell lines SK-BR-3, MDA-MB-231, and BT-474 were purchased from ATCC. Human breast cancer cell line KPL-4 (Kurebayashi et al., 1999) was kindly provided by Dr. Naoto T. Ueno based on an MTA with the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX) and with permission from Dr. Junichi Kurebayashi (Kawasaki Medical School; Kurashiki, Japan). All four human breast cancer cell lines were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat inactivated FBS and 1× penicillin-streptomycin (containing 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin; all from Thermo Fisher). Expi293F cells were cultured in Expi293 expression medium supplemented with 1× penicillin-streptomycin (all from Thermo Fisher).

METHOD DETAILS

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of h38C2_Arg Fab, DVD-Fab, and DVD-IgG1

Fab.

Light chain (Vκ-Cκ; LC) and heavy chain fragment (VH-CH1; Fd) encoding sequences of h38C2 Fab (Rader et al., 2003b) with a Lys99Arg mutation in VH and an N-terminal human CD5 signal peptide (MPMGSLQPLATLYLLGMLVASVLA) encoding sequence were separately cloned via NheI/XhoI (New England Biolabs) into mammalian expression vector pCEP4. Purified (Qiagen) plasmids encoding LC and Fd were co-transfected into Expi293F cells, which had been grown in 300 mL Expi293 Expression Medium to a density of 3×106 cells/mL, using the ExpiFectamine 293 Transfection Kit (Thermo Fisher) following the manufacture’s instruction. After continued culturing in 300 mL Expi293 Expression Medium at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 5 days, the culture supernatant was collected and purified by affinity chromatography with a 1-mL HiTrap KappaSelect column in conjunction with an ÄKTA FPLC instrument (both from GE Healthcare). The yield of Fab was ~15 mg/L as determined by the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher). The Fab was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) connected to the AKTA FPLC instrument. Fab peak fractions were concentrated by an Amicon Ultra 0.5-mL Centrifugal Filter (MilliporeSigma) and brought into 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 5.5).

DVD-Fab.

The same LC and Fd expression cassettes as for the Fab extended by Vκ and VH outer domain encoding sequences, respectively, of trastuzumab spaced from the inner domains by ASTKGP encoding sequences were cloned to generate a HER2-targeting h38C2_Arg DVD-Fab (Nanna et al., 2017). Following expression in the Expi293F system described above, the culture supernatant was collected and purified by affinity chromatography with a 1-mL Protein A HP column (GE Healthcare) in conjunction with the ÄKTA FPLC instrument. The yield of DVD-Fab was ~18 mg/L as determined by the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit and its purity was confirmed by SDS-PAGE using a 10-well NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris Protein Gel followed by staining with PageBlue Protein Staining Solution (all from Thermo Fisher). Using the same procedure, a DVD-Fab containing parental h38C2_Lys was cloned, expressed, and purified.

DVD-IgG1.

Using the same inner (h38C2_Arg) and outer domain (anti-HER2) encoding sequences as for the DVD-Fab, a DVD-IgG1 was cloned into pCEP4 as described (Nanna et al., 2017). A heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 that combined an h38C2_Arg heavy chain with a parental h38C2_Lys heavy chain was based on knobs-into-holes mutations in CH3 (Merchant et al., 1998; Qi et al., 2018). Expression, purification, and analysis of the homodimeric and heterodimeric DVD-IgG1s was identical to the DVD-Fab described above. The yields were ~19 mg/L.

Crystallization and Structure Determination of h38C2_Arg Fab

Crystals were obtained by vapor diffusion at room temperature (RT) from a precipitant condition containing 20% (w/v) PEG 3350, 40 mM ammonium sulfate, and 200 mM ammonium citrate (pH 4.8). A diffraction data set with Bragg spacings to 2.4 Å was collected on a Pilatus3 6M detector at the 5.0.1 beamline at the Advanced Light Source synchrotron facility (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory). Molecular replacement solution was obtained using PDB: 3FO9 (Zhu et al., 2009) as a search model in PHASER (McCoy, 2007). Crystallographic refinement was performed using a combination of PHENIX 1.12 and BUSTER 2.9 (Adams et al., 2010; Bricogne and Bricogne G, 2010). Manual rebuilding, model adjustment, and real space refinements were done using the graphics program COOT (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004). Model figures were created using PYMOL (Schrüdinger). The coordinates and structure factors for the final model were deposited as PDB: 6DZR.

Catalytic Activity Assay

Catalytic activity was analyzed using methodol (List et al., 1998). Followed by dispensing 1 μM and 2 μM of each antibody in 98 μL into a 96 well plate in triplicate, 2 μL of 10 mM methodol was added immediately. The wavelengths of excitation/emission at 330/452 nm were set at Spectra Max M5 instrument to detect fluorescence in 5 min intervals for 1 h (Nanna et al., 2017).

Synthesis of Phenylglyoxal and β-Lactam Derivatives

The syntheses of compounds 1 (phenylglyoxal-TAMRA), 2 (β-lactam-hapten-azide), 3 (β-lactam-hapten-TAMRA), 4 (phenylglyoxal-MMAF), and 5 β-lactam-hapten-Cy7) and their characterization by 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, HRMS, and LC-MS is provided in the folowing. The synthesis of compound 6 (β-lactam-hapten-MMAF) was described previously (Nanna et al., 2017).

General Information.

All non-aqueous reactions were performed in an oven-dried or a flame-dried glassware under argon atmosphere. Unless otherwise mentioned, all reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. Dichloromethane, tetrahydrofuran and N,N-dimethylformamide were purified by passing through a solvent column of desiccant (activated A1-alumina). Methanol was purchased as a reagent grade solvent. Diisopropylethylamine and triethylamine were distilled from calcium hydride under argon atmosphere. All reactions were monitored by either thin-layer chromatography or analytical LCMS. Thi-layer chromatography was performed on Merck TLC silica gel 60 F254 glass plates pre-coated with 0.25mm thickness. Visualization was done by UV light (254 nm), KMnO4 stain, phosphomolybdic acid (PMA) stain, triphenylphosphine solution and/or ninhydrin stain. Purification by preparative thin-layer chromatography was performed on Analtech UNIPLATE silica gel GF UV 254 20 × 20 cm, 2,000μm thickness. Purification on silica gel column chromatography was performed on SiliFlash F60 (40-63 μm, 230-400 mesh). Preparative HPLC purification was performed on Shimadzu LC-8A preparative liquid chromatography with mobile phase A H2O + 0.1% TFA/mobile phase B 1:1 CH3OH:CH3CN or mobile phase A H2O/mobile phase B: CH3CN. 1H-NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 MHz, 600 MHz, or 700 MHz spectrometer in appropriate deuterated solvents. 13C-NMR spectra were recorded at 100 MHz, 150 MHz or 175 MHz. Chemical shifts were reported in parts per million (ppm) on the δ scale from residue solvent peaks. NMR descriptions: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; q, quartet; m, multiplet; br, broad. Coupling constants, J, are reported in Hertz (Hz). Infrared spectra (IR) were recorded on a PerkinElmer Spectrum One FT-IR spectrometer with universal ATR sampling accessory as thin films (neat). High-resolution mass spectra were obtained from a spectrometer (ESI) at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Mass Spectrometry Laboratory. The purity of any materials using in biological experiments were determined by analytical LCMS to be >95%.

Synthesis of compound S1.

A solution of tetraethylene glycol (6.0 mL, 34.8 mmol) in THF (17 mL) was cooled down to 0°C and added with sodium hydride (0.903 g, 22.59 mmol). The reaction was stirred at 0°C for 1 h. Propargyl bromide (1.5 mL, 16.83 mmol) was then added into the cooled solution. The reaction was the allowed to warm up to room temperature and stirred for 16 h. The reaction was quenched with ice-cold water. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2, washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated. The crude mixture was purified with silica gel column chromatography (visualized TLC with KMnO4 stain). The product was obtained as clear colorless viscous liquid (2.37 g, 61%). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 4.18 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 3.72 – 3.55 (m, 17H), 2.77 (s, 1H), 2.42 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H). IR (neat) 3448.93, 3249.92, 2920.77, 2856.78, 2113.97. HRMS calcd for C11H20Na [M+Na]+ 255.1209 found 255.1207.

Synthesis of compound S2.

S1 (0.8 g, 3.44 mmol) and triethylamine (1.440 mL, 10.33 mmol) were dissolved in CH2Cl2 (6 mL) and cooled down to 0°C. A solution of tosyl chloride (0.788 g, 4.13 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (3 mL) was then added to the cooled solution. The reaction was then allowed to warm up to room temperature and stirred for 16 h. The reaction was quenched with saturated aqueous NH4Cl. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2, washed with 1 M HCl, water, and brine, respectively. The organic phase was then dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated to dryness. The crude mixture was purified with silica gel column chromatography. The product was obtained as clear colorless viscous liquid (1.01 g, 76%).1H-NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 7.79 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (dt, J = 7.9, 0.7 Hz, 2H), 4.18 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 4.16 – 4.12 (m, 2H), 3.71 – 3.60 (m, 10H), 3.57 (s, 4H), 2.44 (s, 3H), 2.42 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H). HPLC-MS calcd for C18H27O7S [M+H]+ 387.15 found 387.37.

Synthesis of compound S3.

S2 (986 mg, 2.55 mmol) was dissolved in DMF (5 mL) and then added with sodium azide (415 mg, 6.38 mmol). The reaction suspension was stirred in a 50°C oil bath for 16 h. DMF was then evaporated. The yellow residue was suspended in diethyl ether. Pale yellow precipitate was filtered off by a syringe packed with a plug of cotton wools. The obtained clear yellow solution was dried under reduced pressure. The residue was purified with silica gel column chromatography (50%EtOAc/hexanes to 100% EtOAc, visualized TLC with 10% PPh3 solution followed by ninhydrin stain). The product was obtained as clear pale yellow viscous liquid (0.37 g, 57%). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 4.20 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 3.74 – 3.61 (m, 14H), 3.42 – 3.34 (m, 2H), 2.43 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H). IR (neat) 3254.23, 2867.67, 2098.15.

Synthesis of compound S4.

S3 (370 mg, 1.438 mmol) was dissolved THF (3.0 mL) and added with triphenyl phosphine (754 mg, 2.88 mmol) followed by water (0.026 mL, 1.438 mmol). The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 6 h. The reaction was then dried under vacuum. Viscous yellow residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography (2% to 10% CH3OH/ CH2Cl2 followed by 10% CH3OH/CH2Cl2+1% Et3N, visualized with ninhydrin or KMnO4 stain). The product was obtained as pale yellow viscous liquid (0.33g, 100%). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 4.22 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 3.64 (s, 14H), 2.99 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H), 2.47 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H). IR (neat) 3363.42, 3244.98, 2868.66, 2111.92. HRMS calcd for C11H22NO4 [M+H]+ 232.1549 found 232.1557.

Synthesis of compound S5.

5-TAMRA (20.0 mg, 0.046 mmol) and HATU (17.67 mg, 0.046 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (250 μL). The mixture solution was added with DIPEA (40 μL, 0.229 mmol) and stirred at room temperature for 10 min. Then a solution of S4 (11.82 mg, 0.051 mmol) in DMF (150 μL) was added to the activated TAMRA solution. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 1 h (LCMS of the reaction showed complete consumption of 5-TAMRA). The reaction was dried under vacuum and the remaining residue was purified by preparative thin-layer chromatography (5%, 7.5%, and 10% CH3OH/CH2Cl2). The product band was scraped off and suspended in 10% CH3OH/CH2Cl2. The silica gel suspension was passed through a short plug of silica gel, washed off by 10% CH3OH/CH2Cl2+0.05% TFA. The filtrate was evaporated and then dried under high vacuum to yield dark purple viscous residue. The residue was dissolved in 10% iso-PrOH/CH2Cl2 and washed with 1:1 mixture of water: saturated NaHCO3. The aqueous layer was extracted with 10% iso-PrOH/CH2Cl2 until the organic phase is no longer pink. The combined organic phase was washed with brine and evaporated to dryness to yield the product as dark purple solid (30.6 mg, 102%). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.77 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.26 (dd, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 9.5 Hz, 2H), 7.04 (dd, J = 9.5, 2.4 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 4.12 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 3.77 – 3.69 (m, 2H), 3.69 – 3.58 (m, 14H), 3.28 (s, 12H), 2.80 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H). 13C-NMR (101 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 168.24, 167.34, 160.66, 158.94, 138.11, 137.69, 132.82, 131.94, 131.38, 115.57, 114.72, 97.46, 80.58, 75.98, 71.60, 71.54, 71.49, 71.32, 70.46, 70.07, 59.01, 41.25, 40.95. HRMS calcd for C36H42N3O8 [M+H]+ 644.2972 found 644.2977.

Synthesis of compound 1.

To a solution of S5 (7.8 mg, 0.012 mmol) and hydrated 4-azidophenyl glyoxal (3.51 mg, 0.018 mmol) in CH3OH (544 μL) was added aqueous solution of 50 mM THPTA (60.6 μL, 3.03 μmol), 50 mM copper(II) sulfate (60.6 μL, 3.03 μmol), and 100 mM sodium ascorbate (6.06 μL, 6.06 μmol) at room temperature. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and then evaporated under reduced pressure to remove methanol. The aqueous residue was stirred with 200 mg of Quadra pure TU resin (preswelled in THF for 30 min) for 3 h. The reaction was filtered through 0.2 μM PFTE filter and purified with preparative HPLC (254 nm). The fractions containing product were evaporated to remove acetonitrile. The remaining aqueous solution was lyophilized to give the product as a dark purple powder (7.3 mg, 72%). 1H-NMR (700 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.69 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 8.17 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.42 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (dd, J = 9.5, 3.3 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (ddd, J = 9.5, 3.9, 2.5 Hz, 2H), 6.80 (dd, J = 3.9, 2.5 Hz, 2H), 5.50 (s, 1H), 4.64 (s, 2H), 3.72 (dd, J = 5.8, 4.7 Hz, 2H), 3.69 – 3.61 (m, 12H), 3.26 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 12H). 13C NMR (176 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 194.52, 168.55, 160.99, 158.82, 158.70, 147.33, 141.48, 137.68, 137.45, 134.79, 132.52, 132.09, 131.52, 131.29, 130.76, 123.04, 120.63, 120.39, 115.33, 115.31, 114.62, 97.35, 97.25, 71.61, 71.60, 71.51, 71.38, 71.01, 70.43, 65.00, 41.26, 40.88. HRMS calcd for C44H49N6O11 [M+H]+ 837.3459 found 837.3440.

S6 was synthesized according to a previously published procedure (1). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 8.43 (s, 1H), 7.50 – 7.46 (m, 2H), 7.23 – 7.19 (m, 2H), 4.64 (s, 2H), 4.28 (s, 2H), 3.56 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 3.05 – 2.93 (m, 6H).

S7 was synthesized according to a previously published procedure (2). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 3.33 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.75 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 1.68 (p, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H). IR (neat) 3371.92, 2936.85, 2869.87, 2089.28.

Synthesis of compound 2.

S6 (15.0 mg, 0.030 mmol) in 200 μL anhydrous DMF was added a solution of S7 (6.00 mg, 0.060 mmol) in 120 μL anhydrous DMF. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The product was purified with silica gel column chromatography (8.2 mg, 66%). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 8.35 (s, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.77 (s, 1H), 4.16 (s, 2H), 4.12 (s, 2H), 3.56 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H), 3.47 – 3.38 (m, 4H), 3.08 – 2.91 (m, 6H), 1.84 (p, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H). 13C-NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.20, 168.69, 166.58, 165.14, 137.13, 135.20, 129.29, 120.44, 71.61, 71.40, 49.74, 38.15, 37.17, 36.65, 36.00, 29.54, 28.75. HRMS calcd for C19H26N6O54Na [M+H]+ 417.1886 found 417.1883.

Synthesis of compound 3.

To a solution of 2 (9.32 mg, 0.022 mmol) and 5(6)-TAMRA-PEG4-propargyl (7.2 mg, 0.011 mmol) in CH3OH (502 μL) was added 50 mM THPTA (55.9 μL, 2.80 μmol), 50 mM copper (II) sulfate (55.9 μL, 2.80 μmol), and 100mM sodium ascorbate (55.9 μL, 2.80 μmol). The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. The reaction was filtered through 0.2 μM PFTE filter and purified with preparative HPLC (254 nm). The fractions containing product were combined and evaporated to remove acetonitrile. The remaining aqueous solution was lyophilized to give the product as a dark purple powder (12.8 mg, 89%, 2TFA salt). 5- and 6-isomer mixture 1H-NMR (400 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.77 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 0.5H), 8.39 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 0.5H), 8.24 (ddd, J = 21.7, 8.1, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (s, 1H), 7.84 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 0.5H), 7.49 (dd, J = 12.2, 8.3 Hz, 2.5H), 7.21 – 7.09 (m, 4H), 7.02 (dt, J = 9.4, 2.7 Hz, 2H), 6.95 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 4.57 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 4.47 – 4.41 (m, 2H), 4.17 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 2H), 4.08 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 2H), 3.66 (m, 22H), 3.29 (s, 12H), 3.03 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H), 2.92 (m, 4H), 2.13 (m, 2H). HRMS calcd for C55H66N9O13 [M+H]+ 1060.4780 found 1060.4779.

Synthesis of compound S8.

A solution of triethylene glycol (6 mL, 44.9 mmol) in THF (22.45 mL) was cooled down to 0°C and added with sodium hydride (1.167 g, 29.2 mmol). The reaction was stirred at 0°C for 1 h. Propargyl bromide (1.5 mL, 16.83 mmol) was then added. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 16 h. The reaction was quenched with ice-cold water, extracted with CH2Cl2, washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated down. The crude mixture was purified with silica gel column chromatography. The product was obtained as clear colorless viscous liquid (1.71 g, 40%). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 4.19 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 3.75 – 3.63 (m, 10H), 3.62 – 3.56 (m, 2H), 2.49 (s, 1H), 2.43 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H). IR (neat) 3451.22, 3250.90, 2869.21, 2112.49. HRMS calcd for C9H16O4Na [M+Na]+ 211.0946 found 211.0947.

Synthesis of compound S9.

A solution of S8 (200 mg, 1.063 mmol) in THF (0.5 mL) was added potassium tert-butoxide (5.96 mg, 0.053 mmol). The reaction was then added dropwise with tert-butyl acrylate (177 mg, 1.381 mmol). The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 16 h. The reaction was neutralized with 1M HCl then partitioned with CH2Cl2 and brine. The organic phase was extracted, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude mixture was purified with silica gel column chromatography. The product was obtained as clear colorless viscous liquid (0.28 g, 83%). 1H-NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 4.20 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 3.77 – 3.53 (m, 14H), 2.50 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.42 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 1.44 (s, 9H). IR (neat) 3258.87, 2976.71, 2869.31, 2114.65, 1727.05. HPLC-MS calcd for C16H29NaO6 [M+H+Na]+ 340.19, found 340.45.

Synthesis of compound S10.

A solution of S9 (273.0 mg, 0.863 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (2.7 mL) was added with trifluoroacetic acid (1.4 mL, 18.17 mmol). The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. After TLC showed complete consumption of starting material, TFA was co-evaporated with toluene/CH2Cl2 3 times. Slightly yellow clear viscous liquid product was dried under high vacuum and used without further purification. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 4.21 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 3.77 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 3.73 – 3.58 (m, 12H), 2.64 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 2.43 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H). IR (neat) ~3500-2500 (very broad), 3257.04, 2876.00, 2115.78, 1716.74. HRMS calcd for C12H20O6Na [M+Na]+ 283.1158 found 283.1164.

Synthesis of compound S11.

S10 (6.15 mg, 0.024 mmol), HATU (8.09 mg, 0.021 mmol) were dissolved with DMF (100 μL). The solution was then added with DIPEA (10.32 μL, 0.059 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min. A solution of MMAF TFA salt (10 mg, 0.012 mmol, Levena Biopharma) in DMF (100 κL) was then added to the solution of activated acid. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The reaction was filtered through 0.2 μM PFTE and purified with preparative HPLC (210 nm). Fractions containing product were evaporated and lyophilized to give the product as white solid. 1H-NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d) δ 8.33 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 0.38H), 8.16 (dq, J = 18.3, 9.7, 9.1 Hz, 0.47H), 7.90 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 0.27H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 0.36H), 7.33 – 7.13 (m, 5.00H), 4.78 – 4.53 (m, 2.8H), 4.19 (t, J = 1.9 Hz, 2.09H), 4.17 – 3.89 (m, 1.88H), 3.88 – 3.74 (m, 2.77H), 3.73 – 3.57 (m, 13.84H), 3.46 – 3.33 (m, 5.94H), 3.26 – 3.05 (m, 5.96H), 3.01 – 2.62 (m, 5.53H), 2.56 – 2.40 (m, 2.04H), 2.39 – 2.19 (m, 2.25H), 2.18 – 1.95 (m, 1.86H), 1.95 – 1.69 (m, 3.11H), 1.58 (ddt, J = 31.6, 13.1, 7.1 Hz, 1.09H), 1.49 – 1.35 (m, 1.66H), 1.34 – 1.25 (m, 1.11H), 1.20 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1.47H), 1.15 (dd, J = 6.5, 3.3 Hz, 1.81H), 1.12 – 0.75 (m, 20.88H). HRMS calcd for C51H84N5O13 [M+H]+ 974.6065 found 974.6036

Synthesis of compound 4.

S11 (7.5 mg, 7.70 μmol) was mixed with a solution of hydrated 4-azidophenyl glyoxal (2.231 mg, 0.012 mmol) in CH3OH (345 μL). Then aqueous solution of 50mM THPTA (38.5 μL, 1.925 μmol), 50mM copper (II) sulfate (38.5 μL, 1.925 μmol), and 100 mM sodium ascorbate (38.5 μL, 3.85 μmol) were added. LCMS of crude reaction showed complete consumption of alkyne starting material at 2 h. The reaction was evaporated to remove CH3OH. Aqueous residue was diluted with water and passed through a plug of basic activated lumina and through 0.2 μM PFTE filter, purified with preparative HPLC. (monitored at 210 nm) to give product as off-white powder (8.5 mg, 94%). 1H-NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.52 (s, 0.04H), 8.93 (s, 0.86H), 8.54 (dd, J = 9.0, 5.5 Hz, 0.51H), 8.35 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.0 Hz, 0.35H), 8.27 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1.62H), 8.14 (dd, J = 14.7, 8.1 Hz, 0.59H), 8.08 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1.67H), 7.95 (s, 0.08H), 7.92 – 7.84 (m, 0.09H), 7.76 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 0.24H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 0.25H), 7.27 – 7.11 (m, 5.00H), 7.10 (s, 0.07H), 7.02 (s, 0.07H), 5.68 (s, 0.74H), 4.64 (s, 2H), 4.73 – 4.36 (m, 4H), 3.64 – 3.60 (m, 5.05H), 3.56 (t, J = 6.0, 3.7 Hz, 2.88H), 3.53 – 3.41 (m, 10.81H), 3.32 – 3.12 (m, 8.80H), 3.12 – 2.99 (m, 2.95H), 2.95 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 1.41H), 2.92 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1.37H), 2.88 (s, 0.34H), 2.85 – 2.70 (m, 3.73H), 2.67 – 2.52 (m, 1.61H), 2.45 – 2.28 (m, 1.71H), 2.26 – 1.84 (m, 4.56H), 1.84 – 1.57 (m, 3.21H), 1.48 – 1.17 (m, 2.79H), 1.05 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1.05H), 1.01 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1.06), 0.97 – 0.61 (m, 20.04H). 13C-NMR (151 MHz, DMSO) δ 195.61, 189.15, 187.05, 173.90, 173.86, 173.82, 173.71, 173.60, 173.47, 173.00, 172.93, 171.66, 171.62, 171.12, 171.09, 170.15, 170.07, 170.03, 169.44, 169.29, 169.16, 162.79, 159.02, 158.78, 158.54, 158.30, 145.95, 140.03, 138.19, 137.94, 133.64, 131.79, 131.77, 131.53, 129.59, 129.41, 129.38, 129.17, 129.10, 128.59, 128.57, 128.49, 126.75, 126.68, 122.89, 122.81, 120.25, 120.00, 119.98, 90.21, 90.20, 85.82, 81.84, 67.51, 67.25, 64.69, 63.85, 63.80, 61.49, 61.41, 61.25, 61.14, 60.66, 58.98, 58.65, 57.59, 57.54, 56.24, 55.57, 54.62, 54.55, 54.44, 53.47, 53.20, 52.36, 47.71, 47.56, 46.72, 46.61, 43.87, 43.55, 43.37, 36.82, 33.91, 33.62, 33.59, 32.08, 32.05, 31.74, 31.24, 31.08, 30.67, 30.64, 30.44, 30.38, 28.92, 28.88, 27.90, 26.86, 26.75, 26.18, 25.75, 25.71, 25.66, 25.04, 24.73, 23.57, 19.64, 19.60, 19.37, 19.23, 19.20, 19.11, 18.98, 18.92, 18.86, 18.72, 18.64, 16.10, 16.04, 15.87, 15.83, 15.65, 15.56, 15.49, 15.32, 10.87, 10.68. HRMS calcd for C59H91N8O16 [M+H]+ 1167.6553 found 1167.6531.

Synthesis of compound S12.

S6 (50.0 mg, 0.100 mmol) was dissolved in 200 μL THF. A solution of 2-(2-(2-(2-azidoethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethan-1-amine (36.0 mg, 0.165 mmol) in 200 μL THF was then added to the reaction vial. The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 16 h. The reaction was concentrated under reduced pressure and purified by silica gel column chromatography (1% CH3OH/CH2Cl2 to 10% CH3OH/CH2Cl2) to give the desired product as clear colorless viscous liquid (53.0 mg, 99%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.95 (s, 1H), 8.14 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 7.53 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 4.13 (s, 2H), 4.04 (s, 2H), 3.62 – 3.55 (m, 3H), 3.52 (s, 8H), 3.46 (td, J = 5.6, 3.7 Hz, 4H), 3.38 (dd, J = 5.6, 4.3 Hz, 2H), 3.33 – 3.25 (m, 2H), 3.04 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H), 2.85 (d, J = 43.2 Hz, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 169.39, 169.00, 167.59, 165.75, 136.31, 135.93, 128.49, 119.99, 70.66, 70.51, 69.78, 69.74, 69.67, 69.56, 69.23, 68.88, 49.97. HRMS calcd for C24H35N6O8 [M+H]+ 535.2516 found 535.2523.

Synthesis of compound 5.

A solution of Cyanine7-alkyne (2.0 mg, 3.21 μmol, Lumiprobe Corporation) and compound 3 (2.062 mg, 3.86 μmol) in CH3OH (144 μL) was treated with aqueous solution 50mM THPTA (16.07 μL, 0.803 μmol), 50mM copper (II) sulfate (16.07 μL, 0.803 μmol) and 100mM sodium ascorbate (16.07 μL, 1.607 μmol). The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. The crude reaction was filtered through 0.2 μM PFTE filter and purified with preparative HPLC. The fraction containing product was evaporated to dryness to yield the product as blue-green film coating the bottom of the vial (2.54 mg, 59%, 2TFA salt). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.96 (s, 1H), 8.28 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (s, 1H), 7.73 – 7.63 (m, 3H), 7.57 (dd, J = 7.6, 3.5 Hz, 2H), 7.56 – 7.49 (m, 2H), 7.44 – 7.29 (m, 4H), 7.27 – 7.13 (m, 4H), 6.14 (dd, J = 14.2, 5.0 Hz, 2H), 4.47 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 4H), 4.25 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 4H), 4.12 (s, 2H), 4.03 (s, 2H), 3.77 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 2H), 3.61 (s, 3H), 3.46 (d, J = 28.7 Hz, 12H), 3.28 (q, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 3.03 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H), 2.91 – 2.77 (m, 4H), 2.14 – 2.05 (m, 2H), 1.88 – 1.50 (m, 20H), 1.42 – 1.30 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 172.12, 171.66, 170.49, 169.58, 169.23, 167.77, 165.95, 158.56, 158.36, 158.16, 157.97, 147.99, 147.46, 144.88, 143.01, 142.34, 140.97, 140.93, 136.36, 136.14, 134.99, 132.08, 131.91, 130.34, 128.64, 124.70, 124.48, 123.21, 122.47, 122.37, 120.17, 117.23, 115.54, 110.97, 110.86, 100.28, 99.64, 70.72, 70.57, 69.72, 69.65, 69.63, 68.95, 68.85, 49.42, 48.70, 48.65, 43.25, 38.33, 37.55, 36.56, 35.68, 35.05, 34.18, 31.18, 28.87, 27.31, 27.13, 26.59, 25.91, 24.96, 23.47, 21.20. HRMS calcd for C64H82N9O9 [M]+ 1120.6236 found 1120.6211.

Antibody Conjugation

DVD-Fab conjugation to phenylglyoxal and β-lactam-hapten derivatives.

10 μM h38C2_Arg and h38C2_Lys DVD-Fab were incubated with three different concentrations (10 μM, 50 μM, 100 μM) of phenylglyoxal-TAMRA (compound 1) in 50 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaHCO3 (pH 6.0) for 3 h at 37°C. As a positive control, 10 μM of h38C2_Lys DVD-Fab was incubated with β-lactam-hapten-TAMRA (compound 3) in PBS (pH 7.4) for 3 h at RT in parallel. 7.5 μg of each conjugation mixture was loaded onto a 10-well NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris Protein Gel. Fluorescent bands were visualized by blue light on an E-gel Imager (Thermo Fisher) and the gel was subsequently stained by PageBlue Protein Staining Solution. To test whether DVD-Fab conjugation to phenylglyoxal can be blocked with β-lactam-hapten derivatives, 10 μM h38C2_Arg and h38C2_Lys DVD-Fab were pre-incubated with 100 μM β-lactam-hapten-azide (compound 2) for 3 h at RT and then processed and analyzed as described above. To generate ADCs in DVD-Fab format, 10 μM h38C2_Arg DVD-Fab was incubated with 50 μM phenylglyoxal-MMAF (compound 4) in 50 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaHCO3 (pH 6.0) for 3 h at 37°C. In parallel, 10 μM h38C2_Lys DVD-Fab was incubated with 50 μM β-lactam-hapten-MMAF (compound 6) at RT for 4 h. Following incubation, illustra NAP-5 Columns (GE Healthcare) were used to remove free compounds and the ADCs were concentrated with Amicon Ultra 0.5-mL Centrifugal Filters to 1 mg/mL in PBS (pH 7.4).

DVD-IgG1 conjugation to phenylglyoxal and β-lactam-hapten derivatives.

To generate ADCs in DVD-IgG1 format, 10 μM homodimeric h38C2_Arg DVD-IgG1 or heterodimeric h38C2_Arg/h38C2_Lys DVD-IgG1 was incubated with 50 μM phenylglyoxal-MMAF (compound 4) in PBS (pH 6.6) for 3 h at 37°C. In parallel, 10 μM homodimeric h38C2_Lys DVD-IgG1 or heterodimeric h38C2_Arg/h38C2_Lys DVD-IgG1was incubated with 50 μM β-lactam-hapten-MMAF (compound 6) at RT for 4 h. Following incubation, illustra NAP-5 Columns (GE Healthcare) were used to remove free compounds and the ADCs were concentrated with Amicon Ultra 0.5-mL Centrifugal Filters to 2 mg/mL in PBS (pH 7.4).

Sequential and simultaneous one-pot conjugation of heterodimeric DVD-IgG1 to phenylglyoxal and β-lactam-hapten derivatives.

10 μM heterodimeric h38C2_Arg/h38C2_Lys DVD-IgG1 in PBS (pH 6.6) was sequentially incubated with 50 μM phenylglyoxal-TAMRA (compound 1) for 3 h at 37°C and then, without purification, with β-lactam-hapten-Cy7 (compound 5) for 3 h at 37°C. The reverse order (compound 5 first and compound 1 second) was carried out in parallel. 5 μg of each conjugation mixture was loaded onto a 10-well NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris Protein Gel. TAMRA conjugation was visualized by blue light on an E-gel Imager and Cy7 conjugation using an Odyssey CLx Imaging System (LI-COR). The gel was subsequently stained by PageBlue Protein Staining Solution. Using the same sequential procedure, a heterodimeric h38C2_Arg/h38C2_Lys DVD-IgG1 conjugated to compound 1 and compound 5 was generated. For instantaneous conjugation, 10 μM heterodimeric h38C2_Arg/h38C2_Lys DVD-IgG1 in PBS (pH 6.6) was simultaneously incubated with 50 μM compound 1 and compound 5 for 3 h at 37°C.

Mass Spectrometry

DVD-Fab.

Following conjugation of 5 and 10 equivalents of phenylglyoxal-TAMRA (compound 1) or 5 equivalents of phenylglyoxal-MMAF (compound 4) to h38C2_Arg DVD-Fab as described above, illustra NAP-5 Columns were used to remove free compound and the conjugated DVD-Fab was concentrated with Amicon Ultra 0.5-mL Centrifugal Filters to 1 mg/mL in PBS (pH 7.4). Following dilution into water, data were obtained on an Agilent Electrospray Ionization Time of Flight (ESI-TOF) mass spectrometer. Deconvoluted masses were obtained using Agilent BioConfirm Software.

DVD-IgG1.

Following conjugation of 5 equivalents of phenylglyoxal-MMAF (compound 4) to h38C2_Arg DVD-IgG1, removal of free compound, and concentration as described above, the conjugated DVD-IgG1 was reduced with 50 mM DTT in PBS for 10 min at RT and then enzymatically deglycosylated by PNGase F (New England Biolabs) overnight at 37°C. The enzyme was removed by a Protein G HP SpinTrap (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The conjugated DVD-IgG1 was concentrated with Amicon Ultra 0.5-mL Centrifugal Filters to 2 mg/mL in PBS (pH 7.4). Following dilution into water, ESI-TOF data were acquired as described above. Heterodimeric h38C2_Arg/h38C2_Lys DVD-IgG1 conjugated to phenylglyoxal-TAMRA (compound 1) and β-lactam-hapten-MMAF (compound 6) was deglycosylated without reduction and processed for ESI-TOF data acquisition as described above.

Tandem Mass Spectrometry

Sample preparation.

h38C2_Arg Fab (50 μg/100 μL) with or without phenylglyoxal modification was reduced by the addition of 5 mM TCEP and incubated for 30 min with shaking at 55°C, followed by the addition of 20 mM iodoacetamide to alkylate cysteine residues. The sample was acidified to pH ~2 and digested with 4 μg pepsin at 37°C with shaking for 16 h. The pH was brought to 7 before submitting the samples for liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis.

LC-MS/MS Acquisition.

The pepsin-digested samples were analyzed on a Q Exactive high-resolution mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a Dionex UltiMate 3000 (Thermo Scientific) LC system using ESI spray ionization. Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Phenomenex Halo Peptide ES-C18 column (250 × 2.1 mm id, 2.7-μm particle size) using a linear gradient of mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid in water) and B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile) at 60 μL/min flow rate as follows: 2% B held for 8 min, increasing to 50 % B at 75 min, and 95% B at 100 min. B was held at 95% until 108 min, then quickly reduced to 2% and equilibrated at 2% B until 120 min. The Q Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer equipped with heated electrospray ionization source (HESI-II) was operated in the positive ESI mode. Source conditions were optimized as follows: The spray voltage was 3.5 kV, capillary temperature 300 °C, heater temperature 180°C, S-lens RF level 80, sheath gas flow rate 20, auxiliary gas flow rate 15 and sweep gas 0 (arbitrary units). Nitrogen was used for the collision gas in the HCD cell and damping gas in the C-trap. MS1 and MS/MS spectra were collected at a resolution of 70, 000 and 17,500, respectively. An MS1 survey scan was followed by MS/MS scans for the top 8 most intense precursor ions selected in the quadrupole with 1.5 m/z isolation window. Only ions with a charge state of +2 to +4 were selected for MS/MS and a 45 s exclusion time was used.

Data analysis.

Analysis of peptides and modified peptides was performed using PEAKS 8.0 software (Bioinformatics Solutions). Mass tolerances for precursor and fragment ions were set to 10 ppm and 0.02 Da, respectively. Searches were performed with enzyme setting as pepsin and with variable modifications settings for phenylglyoxal modifications (+116.0262, 132.0197 or 134.0368) of Arg or Lys, oxidation (+15.99) of methionine, and carbamidomethyl modification (+57.02) of cysteine. The amino acid sequence of h38C2_Arg Fab was used for subject-specific database searching. Mass tolerance for extracted precursor ion chromatogram was set to 10 ppm.

Human Plasma Stability Assay

To assess its stability in human plasma, 1 mg/mL of h38C2_Arg based DVD-Fab conjugated to phenylglyoxal-TAMRA (compound 1) in PBS was mixed with an equal volume of human plasma (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated at 37°C. After 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, 96, 122, 196, and 240 h, 2μL aliquots were frozen and stored at −80°C. After aliquots from all time points had been collected, they were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions using a 10-well NuPAGE 4-12% Bis-Tris Protein Gel. Fluorescent bands were visualized by blue light on an E-gel Imager (Thermo Fisher) and the gel was subsequently stained by PageBlue Protein Staining Solution. The experiment was carried out three times independently. Band intensities at 0 and 240 h were quantified by NIH ImageJ software and plotted as mean ± SD values.

Cytotoxicity Assay

SK-BR-3 (5×103 per well), MDA-MB-231 (3×103 per well), KPL-4 (3×103 per well), and BT-474 cells (5×103 per well) were plated in 96-well tissue culture plates. Ten-fold serially diluted ADCs and their corresponding unconjugated DVD-Fab (0.01-100 nM) or DVD-IgG1 (0.001-10 nM) were added to the cells and the plates were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 72 h. Subsequently, cell viability was measured using CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution (Promega) following the manufacturer’s instructions and plotted as a percentage of untreated cells. IC50 values (mean ± SD) were calculated by GraphPad Prism software.

Size-Exclusion Chromatography

Unconjugated and phenylglyoxal-MMAF (compound 4)-conjugated h38C2_Arg based DVD-Fab was analyzed by SEC using a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) connected to an ÄKTA FPLC system. Samples (30 μg in 50 μL PBS) were loaded on the column using 50 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl (pH 7.0) as mobile phase and a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The percentage of aggregates was determined by integration of peak areas at 280 nm. A Gel Filtration Calibration kit for high molecular weight range (GE Healthcare) was used as standard and included ferritin (F; 440 kDa), aldolase (A; 158 kDa), conalbumin (C; 75 kDa), and ovalbumin (O; 44 kDa).

Surface Plasmon Resonance

SPR for the measurement of kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of the binding of unconjugated and conjugated DVD-Fab to HER2 were performed on a Biacore X100 instrument using Biacore reagents and software (GE Healthcare). A mouse anti-human IgG CH2 mAb was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip using reagents and instructions supplied with the Human Antibody Capture Kit (GE Healthcare). Human HER2-Fc fusion protein (R&D Systems) was captured at a density not exceeding 300 RU. Each sensor chip included an empty flow cell for instantaneous background depletion. All binding assays used 1x HBS-EP+ running buffer (10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA (pH 7.4), and 0.05% (v/v) Surfactant P20) and a flow rate of 30 μL/min. For affinity measurements, all DVD-Fab were injected at five different concentrations. At least two independent experiments for each sample were carried out. The sensor chips were regenerated with 3 M MgCl2 from the Human Antibody Capture Kit without any loss of binding capacity. Calculation of association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants was based on a 1:1 Langmuir binding model. The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) was calculated from koff/kon.

Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy

SK-BR-3 and MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 35-mm Nunc Glass Bottom Dishes (Thermo Fisher) at 5×104 cells per dish. TAMRA (compound 1) / MMAF (compound 6)-labeled heterodimeric h38C2_Arg/h38C2_Lys DVD-IgG1 was added to a final concentration of 5 μg/mL in the presence or absence of 10 μM PAO (Sigma-Aldrich). TAMRA (compound 3)-labeled homodimeric h38C2_Lys DVD-IgG1 in which the outer Fv derived from trastuzumab was replaced with the outer Fv of a humanized version of rabbit anti-human ROR2 mAb XBR2–401 (Peng et al., 2017) was used as negative control. (SK-BR-3 and MDA-MB-231 cells do not express ROR2). After 4 h incubation, the cells were washed with cold PBS three times to stop internalization, and fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (Alfa Aesar) for 15 min at RT. Then, 0.2 M glycine-HCl (pH 2.0) was added for 5 min to remove extracellular bound antibodies. Samples were blocked with 2% (w/v) BSA in PBS for 1 h after permeabilization with 0.2% (v/v) Triton X-100 for 15 min at RT. After washing with cold PBS three times, the samples were incubated for 1 h with FITC-conjugated goat antihuman IgG F(ab’)2 polyclonal antibodies (Thermo Fisher) diluted in 2% (w/v) BSA in PBS. After washing with cold PBS three times, samples were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Thermo Fisher) diluted in PBS for 10 min and washed again with cold PBS three times. Images were captured on a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal system at the Light Microscopy Facility of the Max Planck Florida Institute of Neuroscience (Jupiter, FL).

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

The catalytic activity of h38C2 (Figure 3B and 5B) and cell viability data (Figure 5C, S4C, and S6) are presented as mean ± SD of triplicates. IC50 values were calculated by GraphPad Prism. In-gel fluorescence to determine human plasma stability (Figure S3) was quantified by NIH ImageJ software and mean ± SD values of three independent experiments; a t-test was used to calculate p.

Data and Software Availability

Coordinates and diffraction data of h38C2_Arg Fab were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession number 6DZR.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of phenylglyoxal-TAMRA (1).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of β-lactam-hapten-azide (2) and β-lactam-hapten-TAMRA (3).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of phenylglyoxal-MMAF (4).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of β-lactam-hapten-Cy7 (5).

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| FITC-conjugated goat anti-human IgG F(ab’)2 polyclonal antibodies | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 31628 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| HEPES | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# H3375 |

| DTT | Thermo Fisher | Cat# BP172-5 |

| Iodoacetamide | GE Healthcare | Cat# RPN6302V |

| Pepsin | Promega | Cat# V195A |

| Phenylglyoxal hydrate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 142433-5G |

| PAO | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# P3075-1G |

| Paraformaldehyde | Alfa Aesar | Cat# J61899-AK |

| PEG 3350 | Hampton Research | Cat# HR2-527 |

| Ammonium sulfate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A4915-500G |

| Ammonium citrate dibasic | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# 09833 |

| TCEP | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# C4706-10G |

| Triton X-100 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# X 100-500ML |

| DAPI | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 62248 |

| Sodium bicarbonate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# S5761 |

| Sodium phosphate, monobasic | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# S5011-500G |

| Sodium phosphate, dibasic | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# S5136-500g |

| Sodium chloride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# S7653-1Kg |

| Glycine | Thermo Fisher | Cat# BP381-1 |

| Compound 1 | This paper | N/A |

| Compound 2 | This paper | N/A |

| Compound 3 | This paper | N/A |

| Compound 4 | This paper | N/A |

| Compound 5 | This paper | N/A |

| Compound 6 | Nanna et al., 2017 | N/A |

| See chemistry procedures for synthesis of additional compounds | This paper | N/A |

| PNGase F | New England Biolabs | Cat# P0705S |

| NheI-HF | New England Biolabs | Cat# R3131S |

| XhoI | New England Biolabs | Cat# R0146S |

| Human serum from human male AB plasma | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# H4522 |

| Recombinant human HER2-Fc fusion protein | R&D Systems | Cat# 1129-ER |

| BSA | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A2058 |

| h38C2_Arg Fab | This paper | N/A |

| Anti-HER2 DVD-Fab_Arg | This paper | N/A |

| Anti-HER2 DVD-Fab_Lys | This paper | N/A |

| Homodimeric anti-HER2 DVD-IgG1_Arg | This paper | N/A |

| Homodimeric anti-HER2 DVD-IgG1_Lys | Nanna et al., 2017 | N/A |

| Heterodimeric anti-HER2 DVD-IgG1_Arg/Lys | This paper | N/A |

| h38C2_Arg Fab-phenylglyoxal | This paper | N/A |

| Anti-HER2 DVD-Fab_Arg-TAMRA | This paper | N/A |

| Anti-HER2 DVD-Fab_Arg-MMAF | This paper | N/A |

| Anti-HER2 DVD-Fab_Lys-MMAF | This paper | N/A |

| Homodimeric anti-HER2 DVD-IgG1_Arg-MMAF | This paper | N/A |

| Homodimeric anti-HER2 DVD-IgG1_Lys-MMAF | Nanna et al., 2017 | N/A |

| Heterodimeric anti-HER2 DVD-IgG1_Arg/Lys-MMAF | This paper | N/A |

| Heterodimeric anti-HER2 DVDIgG1-Arg/Lys-MMAF/TAMRA | This paper | N/A |

| Anti-human ROR2 mAb DVD-IgG1-TAMRA | This paper | N/A |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| ExpiFectamine 293 Transfection Kit | Thermo Fisher | Cat# A14525 |

| Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 23225 |

| Gel Filtration Calibration kit | GE Healthcare | Cat# 28403842 |

| Human Antibody Capture Kit | GE Healthcare | Cat# BR100839 |

| CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution | Promega | Cat# G3580 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Crystal structure of h38C2_Arg Fab | PDB | 6DZR |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Human: SK-BR-3 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-30 |

| Human: MDA-MB-231 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-26 |

| Human: BT-474 | ATCC | Cat# HTB-20 |

| Human: KPL-4 | Kurebayashi et al., 1999 | N/A |

| Human: Expi293F | Thermo Fisher | A14527 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pCEP4 vector | Nanna et al., 2017 | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| PHENIX 1.12 | Adams et al., 2010 | https://www.phenix-online.org/download/ |

| BUSTER 2.9 | Bricogne and Bricogne, 2010 | https://packages.debian.org/buster/libxml2-dev |

| COOT | Emsley and Cowtan, 2004 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| PYMOL | Schrödinger | https://pymol.org/2/ |

| Odyssey CLx Imaging System | LI-COR | https://www.licor.com/bio/odyssey-clx/ |

| BioConfirm | Agilent Technologies | https://www.agilent.com/en/products/software-informatics/masshunter-suite/masshunter-for-pharma/bioconfirm-software |

| PEAKS 8.0 | Bioinformatics Solution | http://www.bioinfor.com/peaks-studio/ |

| ImageJ | Li et al., 2017 | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| Prism 5.0 | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Biacore X100 software | GE Healthcare | https://www.gelifesciences.com/en/us/shop/protein-analysis/spr-label-free-analysis/systems/biacore-x100-p-05730 |

| ZEN lite | ZEISS | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/int/products/microscope-software/zen-lite.html |

SIGNIFICANCE.

Fueled by the mounting success of therapeutic and diagnostic monoclonal antibodies, substantial efforts have focused on defined antibody-small molecule conjugates. Here we describe the first site-selective antibody functionalization that employs an engineered arginine. This was achieved by replacing a uniquely reactive lysine in the active site of a catalytic antibody with an arginine followed by its selective conjugation to cytotoxic or fluorescent small molecules. Combining uniquely reactive arginine and lysine residues in one antibody molecule affords orthogonal conjugation and delivery of two different cargos with high precision and efficiency. The ability to site-selectively, simultaneously, and stably functionalize arginine and lysine considerably deepens the antibody conjugation toolbox, affording new opportunities of broad therapeutic and diagnostic utility.

Highlights.

X-ray crystallography confirmed an engineered antibody with a reactive arginine

The reactive arginine enabled site-selective and stable antibody functionalization

Pairing reactive arginine and lysine facilitated orthogonal dual cargo conjugation

The platform was applied to antibody-drug conjugates in dual variable domain format

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by NIH grants R01 CA174844, R01 CA181258, and R01 CA204484 (to C.R.). D.H. received postdoctoral support from the Cancer Research Institute, Seoul National University (Seoul, South Korea), with special thanks to Dr. Junho Chung. N.N. received a Predoctoral Fellowship from the Royal Thai Government (Bangkok, Thailand). A.R.N. received a Predoctoral Fellowship from the American Chemical Society Division of Medicinal Chemistry. Confocal images used in this article were generated at the Light Microscopy Facility of the Max Planck Florida Institute of Neuroscience (Jupiter, FL). This is manuscript # 29771 from The Scripps Research Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

C.R., D.H., and N.N. are named inventors on a patent application that claims dual variable domain antibodies based on h38C2_Arg. C.R., A.R.N., and W.R.R. are named inventors on a patent application that claims dual variable domain antibodies based on h38C2_Lys.

REFERENCES

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. (2010). PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adumeau P, Vivier D, Sharma SK, Wang J, Zhang T, Chen A, Agnew BJ, and Zeglis BM (2018). Site-specifically labeled antibody-drug conjugate for simultaneous therapy and ImmunoPET. Mol. Pharm 15, 892–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbas CF 3rd, Heine A, Zhong G, Hoffmann T, Gramatikova S, Bjornestedt R, List B, Anderson J, Stura EA, Wilson IA, et al. (1997). Immune versus natural selection: antibody aldolases with enzymic rates but broader scope. Science 278, 2085–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Goetsch L, Dumontet C, and Corvaia N (2017). Strategies and challenges for the next generation of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 16, 315–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostrom J, Haber L, Koenig P, Kelley RF, and Fuh G (2011). High affinity antigen recognition of the dual specific variants of herceptin is entropy-driven in spite of structural plasticity. PLoS One 6, el7887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricogne G, Blanc E, Brandl M, Flensburg C, Keller P, Paciorek W, Roversi P, Sharff A, Smart O, Vonrhein C & Womack T, and Bricogne G, B.E., Brandl M, Flensburg C, Keller P, Paciorek P, Roversi P, Sharff A, Smart O, Vonrhein C, Womack T (2010). BUSTER version 2.9. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Global Phasing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Bruins JJ, Blanco-Ania D, van der Doef V, van Delft FL, and Albada B (2018). Orthogonal, dual protein labelling by tandem cycloaddition of strained alkenes and alkynes to ortho-quinones and azides. Chem. Commun 54, 7338–7341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chari RV, Miller ML, and Widdison WC (2014). Antibody-drug conjugates: an emerging concept in cancer therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 53, 3796–3827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]