Abstract

Uterine rupture often occurs in the third trimester of pregnancy or during labor. Its occurrence in early pregnancy and in the absence of any predisposing factors is very rare. Untimely diagnosis and a low index of suspicion could be life-threatening. Here we report the case of a 29-year-old woman with a history of two previous cesarean sections. An ultrasound report revealed a dead fetus in the abdominal cavity at 14 weeks into the abdominal cavity due to a rupture at the site of the previous cesarean scar. Awareness of probable diagnosis of uterine rupture in a pregnant woman with abdominal pain could be important for timely diagnosis and proper management.

Keywords: Uterine rupture ; Pregnancy Trimester, First ; Cesarean section

What’s Known

The occurrence of uterine rupture in the first trimester of pregnancy is very rare.

What’s New

Clinical suspicion of possible uterine rupture is essential even in early pregnancy, especially in cases of abdominal pain and unstable vital signs.

A literature review revealed notable and novel viewpoints on uterine rupture.

Introduction

Rupture of the pregnant uterus is one of the most important causes of obstetric hemorrhage. It is classified as complete or partial separation of the uterine layers and can be a life-threatening event for both mother and fetus, especially in complete form.1 The incidence of uterine rupture is 1 in 4,800 deliveries in developed countries and the rupture of an unscarred uterus is a few as 1 in 10,000-15,000 birth.1 The greatest risk factor for either form of rupture is a prior cesarean delivery or other myometrial surgical incision. Other risk factors include grand multiparity, trauma, malpresentation, obstructed labor, misuse of uterotonic drugs, particularly for sequential labor induction.1,2 Uterine rupture rarely occurs in an unscarred pregnant uterus. The probability of a rupture is higher when a combination of several risk factors is present.1,3,4 Most uterine rupture occur in the third trimester at the onset of the contractions and mainly in a previously scarred uterus.5 Uterine rupture in the first trimester of pregnancy or even in the early second trimester is very rare.5,6 Considering the rarity of uterine rupture in the first trimester of pregnancy, we present a rare case of uterine rupture at 14 weeks of gestation in a 29-year-old woman with a history of two prior cesarean sections.

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman (gravida 3, para 2, live 2), with a history of two previous cesarean sections (both were lower segment CS), was admitted to Ghaem University Teaching Hospital (Mashhad, Iran) in November 2017. She complained of moderate abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding during the previous 10 days. Her last menstruation was about 15 weeks prior to admission. Due to the history of an irregular menstrual cycle and lack of financial means, the patient was unable to seek proper medical consultation. She only took a urine pregnancy test. Two days prior to admission, she underwent a sonogram and the report revealed a 24 mm endometrial lining and an 82×37 mm heterogeneous mass in the left adnexa, probably associated with a perforated gestational sac. An 8 cm long dead fetus corresponding to 14 weeks of gestational age, laterally positioned at the side of the heterogeneous mass was reported. The previous two pregnancies were uneventful. There was no history of either curettage or intrauterine device insertion. In addition, she had no history of drug use, abdominal trauma, or smoking.

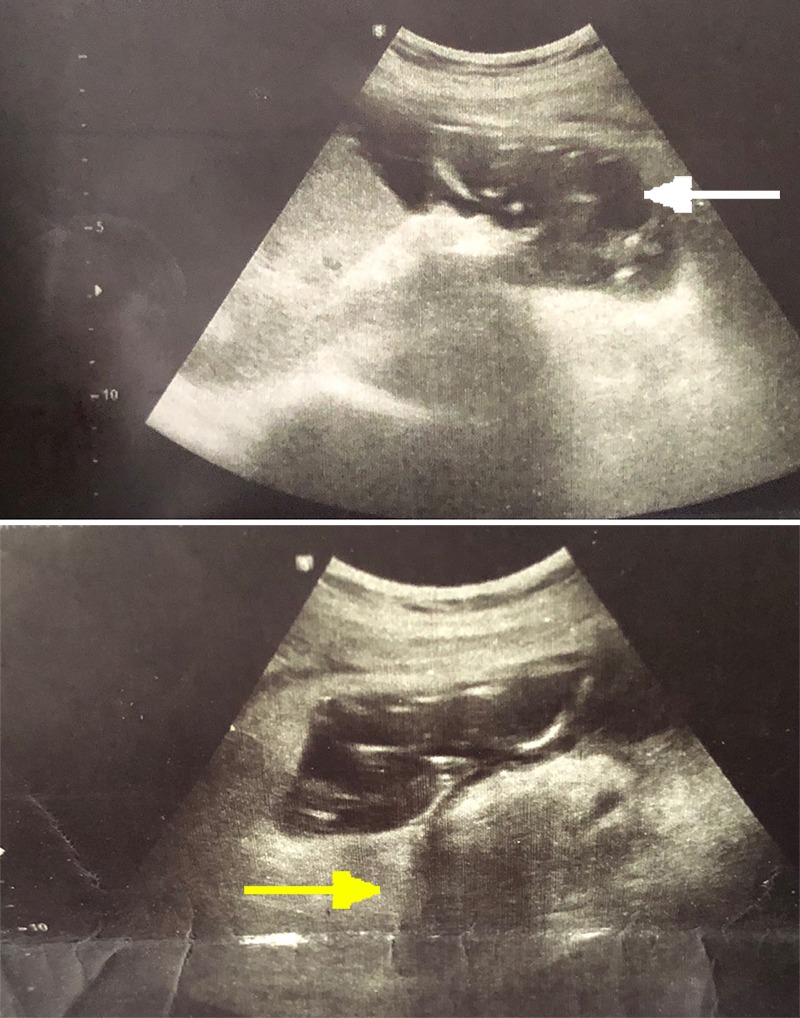

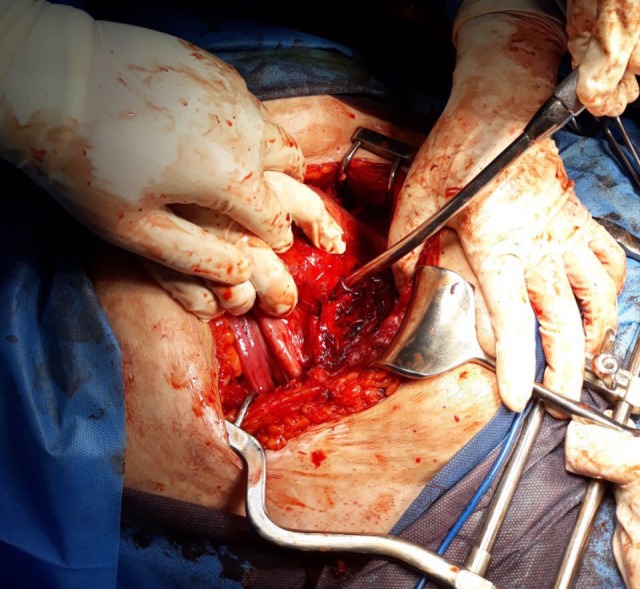

On general examination, the patient was in good condition and was not pale. Physical examination revealed moderate tenderness in the lower abdomen, especially in the left lower quadrant. There was no rebound tenderness. Her vital signs (blood pressure and pulse rate) were normal. On speculum examination, mild vaginal bleeding was observed. Her primary hemoglobin level was 11.8 gr/dl. A second ultrasound assessment revealed a 96×52 mm heterogeneous mass and a fetus without a heartbeat, 13 weeks of gestational age, positioned in the left lateral paracolic gutter of the abdominal cavity (figure 1). With an initial impression of abdominal ectopic pregnancy, laparotomy was performed. After opening the fascia, about 100 cc of hemoperitoneum was suctioned. The patient was about 12 weeks pregnant and placental tissue was present with multiple organized blood clots surrounding the lower segment of the anterior wall of the uterus and bladder. After removal of the placental tissue and clots, a tear of approximately 3 cm in length at the site of the previous cesarean scar was exposed; no active bleeding was noted (figure 2). The uterus was examined for residual placental tissue and the remaining tissue was removed. A macerated fetus was found in the left lateral paracolic gutter of the abdominal cavity (figure 3). Both salpinx and ovary were normal. The presence of a rupture at the site of the previous cesarean scar and almost empty uterus led to a change of diagnosis from abdominal ectopic pregnancy to uterine rupture. There was no abnormal placental adhesion or bleeding, which ruled out the diagnosis of cesarean scar pregnancy. The uterus was closed in two layers of 1-0 vicryl sutures. Subsequently, the abdominal cavity was washed with 2-liter warm saline and the walls were closed in the anatomical plane. There was no medical indication for a blood transfusion nor post-operative complications. Hematinic was prescribed and the patient was discharged 2 days after the surgery. At 6-month follow-up, no specific problems were noted. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.

Figure1.

Trans-Abdominal ultrasound shows empty uterus, mild collection and fetus without heartbeat in the left lateral paracolic gutter of the abdominal cavity corresponding to 13 weeks of gestational age (white arrow) and a heterogeneous mass in the left adnexa (yellow arrow).

Figure2.

Laparotomy revealed a tear of about 3 cm at the site of previous cesarean scar in a 14-week pregnant uterus; shown by suction head.

Figure3.

Fourteen weeks macerated fetus found in the abdominal cavity following uterine rupture.

Discussion

A rare case of uterine rupture at 14 weeks of gestation is reported in which, based on ultrasound reports, the primary diagnosis was extra-uterine pregnancy. However, upon laparotomy, a tear of approximately 3 cm in length was observed at the site of the previous cesarean scar with no active bleeding. A dead fetus was found in the abdominal cavity; confirming the diagnosis of a ruptured uterus.

Uterine rupture accounts for 14% of all hemorrhage-related maternal mortality. Most often, uterine rupture occurs in the third trimester of pregnancy, during labor, or mainly in a previously scarred uterus. Its occurrence in early pregnancy is very rare even in the presence of predisposing risk factors.1,6 At term and near-term pregnant women, especially in the setting of a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery, careful and close monitoring of both mother and fetus can help in its timely diagnosis. Abnormal labor progress, abnormal abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding, loss of station of presenting part, maternal tachycardia, and fetal bradycardia are indicative factors for detecting uterine rupture.5 However, in early pregnancy, especially without the presence of any predisposing risk factors, the diagnosis may occur with latency or may never be detected; leading to life-threatening complications. Furthermore, signs and symptoms of uterine rupture in the early trimester are non-specific.3,4,6 Although the presence of previous uterine scar has been described as the main cause of uterine rupture,1,6-9 some recent studies have reported abnormal placentation (accrete, increta, and percreta) as the most common underlying etiology even in early pregnancy.4,10 As shown in Table 1, a review of 15 cases of uterine rupture in the first trimester of pregnancy showed that the most common causes were placenta percreta (4 cases).8 Considering a worldwide increase in the cesarean delivery rate, such an outcome was anticipated.

Table 1.

Uterine rupture in the gestational age less than 20 weeks

| Author | Year | Age (years) | Gestation (week) | Gravida/para/abortion | Initial presentation | Risk factor | Rupture site | Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbas6 | 2018 | 24 | 10 | 3/2 | Acute abdominal pain and shock | Two previous scars | Fundus and posterior wall | Primary repair |

| Surve7 | 2017 | 25 | 10 | 3/1/ab1 | Acute abdominal pain and shock | Previous scar | Previous scar | Primary repair |

| Miranda9 | 2017 | 32 | 13 | 3/2 | Acute abdominal pain | Previous scar and short pregnancy interval | Previous scar | Primary repair |

| Bandarian8 | 2015 | 30 | 11 | 4/2/ab1 | Acute abdominal pain and shock | Two Previous scars, D&C | Previous scar | Primary repair |

| Ho4 | 2017 | 33 | 17 | 2/0/ab1 | Lower abdominal pain and abdominal distention | Placenta accreta | Fundus | Primary repair |

| Vaezi11 | 2017 | 34 | 12 | 2/1 | Acute abdominal pain | Without | Fundus | Primary repair |

| Mannini12 | 2016 | 34 | 15 | 3/1 | Acute abdominal pain | Without | Fundus | Primary repair |

| Sun3 | 2012 | 31 | 17 | 3/2 | Acute abdominal pain and shock | Without | Fundus | Primary repair |

| Sunanda13 | 2014 | 31 | 17 | 2/ab1 | Acute abdominal pain | Bicornuate uterus | Right horn of fundus | Primary repair |

| Faroog10 | 2016 | 27 | 17 | 4/2/ab1 | Acute abdominal pain | Twin/placenta percreta | None | Total hysterectomy |

| Porcu14 | 2003 | 28 | 12 | 1/0 | Acute abdominal pain | DES | None | None |

| Arbab15 | 1996 | 25 | 8 | Ab2/p2 | Severe hemorrhagic shock | Bilateral salpingectomy/left cornual resection | Vertical rupture of Fundus | Primary repair |

| Arbab15 | 1996 | 34 | 13 | 8/1/ep5/ab1 | Acute abdominal pain and shock | Bilateral salpingectomy /left cornual resection/placenta percreta | Right-sided uterine cornual rupture | Total hysterectomy |

| Arbab15 | 1996 | 33 | 18 | 4/1/ab2 | Acute abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding | Left salpingectomy/left cornual resection | Fundus | Primary repair |

| Arbab15 | 1996 | 25 | 20 | 1/0 | Acute abdominal pain and shock | Bilateral salpingectomy/cornual resection | Fundus | Primary repair |

| The present case | 2018 | 29 | 14 | 3/2 | Abdominal pain | Previous scar | Previous scar | Primary repair |

There is not always an underlying medical cause for uterine rupture.3,11,12 It seems that in these cases, which often occur in early pregnancies, the fundus is the most common site of rupture. This is while in term and near-term pregnancies, most uterine ruptures occur at the site of previous cesarean section scar.1,2 A previous study reported 8 cases of uterine rupture in unscarred uteri at a gestational age of below 20 weeks.11 In all those cases, the fundus was the rupture site. Multiparity was suggested as the main predisposing factor in most cases. However, since the cases involved second or third pregnancies, it seems that there was no underlying medical cause. Other causes of uterine rupture are congenital uterine abnormalities (e.g., bicornuate uterus13 and uterine septum4) and diethylstilbestrol exposure.14 In another study, past medical history of procedures performed on the uterus, such as bilateral salpingectomy or cornual resection, was reported as the main risk factor.15

In most reported cases of uterine rupture in early pregnancy, patients were presented with acute abdominal pain and shock. This might be due to untimely diagnosis or, in most cases, the involvement of the fundus. However, in our case, the patient was stable and showed no sign of hemoperitoneum, which could have been due to the small size of the rupture and hemostasis with clot formation. It seems that despite the difficulty of detecting uterine rupture in early pregnancy, most ruptures can be repaired. The majority of the reviewed studies indicated two main causes of uterine rupture, namely abnormal placenta invasion and previous cesarean scar. This, combined with an increasing rate of cesarean sections worldwide, highlights the need for a high degree of clinical suspicion in early diagnosis of uterine rupture.

Conclusion

Awareness of probable diagnosis of uterine rupture in pregnant women with abdominal pain is important for timely diagnosis and proper management; even in the early gestational age of pregnancies and in the absence of known risk factors.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Spong CY, Dashe JS, et al. Obstetrical hemorrhage. In: Cunningham FG, Gant NF, Leveno KJ, Gilstrap III LC, Hauth JC, Wenstrom KD. Williams obstetrics. 24th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2014. pp. 617-8,790–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Zirqi I, Daltveit AK, Forsen L, Stray-Pedersen B, Vangen S. Risk factors for complete uterine rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:165. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun HD, Su WH, Chang WH, Wen L, Huang BS, Wang PH. Rupture of a pregnant unscarred uterus in an early secondary trimester: a case report and brief review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38:442–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho W, Wang C, Hong S, Han H. Spontaneous Uterine Rupture in the Second Trimester: a Case Report. Obstet Gynecol Int J. 2017;6:00211. doi: 10.15406/ogij.2017.06.00211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Revicky V, Muralidhar A, Mukhopadhyay S, Mahmood T. A Case Series of Uterine Rupture: Lessons to be Learned for Future Clinical Practice. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012;62:665–73. doi: 10.1007/s13224-012-0328-4. [ PMC Free Article] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbas AM, Hussein RS, Ali MN, Shahat MA, Mahmoud AR. Spontaneous first trimester posterior uterine rupture in a multiparous woman with scarred uterus: A case report. Middle East Fertil Soc J. 2018;23:81–3. doi: 10.1016/j.mefs.2017.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Surve M, Pawar S, Panigrahi PP. A Case Report of First Trimester Spontaneous Uterine Scar Rupture. MIMER Medical Journal. 2017;1:26–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bandarian M, Bandarian F. Spontaneous rupture of the uterus during the 1st trimester of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;35:199–200. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2014.937334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miranda ASL, Castro L, Rocha MJ, Cardoso L, Reis I. Uterine Rupture in Early Pregnancy. International Journal of Pregnancy & Child Birth. 2017;2 doi: 10.15406/ipcb.2017.02.00046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farooq F, Siraj R, Raza S, Saif N. Spontaneous Uterine Rupture Due to Placenta Percreta in a 17-Week Twin Pregnancy. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2016;26:121–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaezi M. Unexpected Rupture of Unscarred Uterus at 12 Weeks of Pregnancy: A Case Report and Literature Review. International Journal of Womens Health and Reproduction Sciences. 2017;5:339–41. doi: 10.15296/ijwhr.2017.57. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mannini L, Sorbi F, Ghizzoni V, Masini G, Fambrini M, Noci I. Spontaneous Unscarred Uterine Rupture at 15 Weeks of Pregnancy: A Case Report. Ochsner J. 2016;16:545–7. [ PMC Free Article] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sunanda N, Sudha R, Vineetha R. Second trimester spontaneous uterine rupture in a woman with uterine anomaly: a case report. Int J Sci Stud. 2014;2:229–31. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porcu G, Courbiere B, Sakr R, Carcopino X, Gamerre M. Spontaneous rupture of a first-trimester gravid uterus in a woman exposed to diethylstilbestrol in utero. A case report. J Reprod Med 2003;48:744–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arbab F, Boulieu D, Bied V, Payan F, Lornage J, Guerin JF. Uterine rupture in first or second trimester of pregnancy after in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:1120–2. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]