Abstract

Background:

Young breast cancer survivors (YBCS) have unmet needs for managing hot flashes, fertility-related concerns, sexual health and contraception.

Purpose:

Describe the design and participant characteristics of a randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of the survivorship care plan on reproductive health (SCP-R) intervention on improving hot flashes, fertility-related concerns, sexual health, and contraception in YBCS.

Methods:

SCP-R is a web-based intervention with text message support encompassing evidence-based practices on four reproductive health issues. YBCS with ≥ 1 reproductive health issue are randomized to intervention (full SCP-R access) or attention control (access to list of online resources) arms with 24-week follow-up. The primary outcome will be improvement of at least one reproductive health issue measured by validated self-report instruments. Each YBCS nominated one healthcare provider (HCP), who can access the same materials as their patient. HCP outcomes are preparedness and confidence in discussing each issue.

Results:

Among 318 YBCS screened, 57.2% underwent randomization. Mean age was 40.0 (SD 5.9), and mean age at cancer diagnosis was 35.6 (SD 5.4). Significant hot flashes, fertility-related concerns, vaginal symptoms, and inadequate contraception were reported by 50.5%, 50%, 46.7%, 62.1% of YBCS, respectively; 70.9% had multiple issues. Among 165 nominated HCPs, 32.7% enrolled. The majority of HCPs reported preparedness (68.5-90.7%) and confidence (50.0-74.1%) in discussing reproductive health issues with YBCS. HCPs were least likely to report preparedness or confidence in discussing fertility-related concerns.

Conclusion:

Conducting a trial for improving YBCS reproductive health online is feasible, providing a mechanism to disseminate evidence-based management.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Survivorship care plan, Randomized controlled trial, Hot flashes, Fertility, Contraception

Introduction

There are nearly 3.5 million breast cancer survivors in the United States, with 19% of new cases occurring in women age 45 and younger [1]. Most young breast cancer survivors (YBCS) undergo chemotherapy and/or endocrine therapy, treatments that can impair ovarian function and result in significant reproductive health issues [2]. These include hot flashes, infertility, sexual dysfunction, and limited contraception options, which negatively impact quality of life in survivorship [3-13]. Evidence-based clinical strategies to manage these late effects have been identified, but have limited dissemination among YBCS and their healthcare providers (HCPs) [14-16], resulting in unmet informational needs among YBCS on reproductive health [3].

Breast cancer survivors seek health information and advice from their HCPs and online[5-7,17]. Information seeking in YBCS is associated with increased self-efficacy, satisfaction with treatment decisions, and improved quality of life [6,8]. These findings motivated us to develop a web-based intervention on reproductive health for YBCS and their HCPs.

In 2006, the Institute of Medicine recommended development of survivorship care plans (SCPs) to support the transition of care from cancer treatment to survivorship [9]. SCPs aim to inform patients about the effects of cancer treatment, guide follow-up care, and improve care coordination. Internet accessible SCPs for breast cancer survivors have been developed, but contain limited reproductive health guidance [10,11,18]. Randomized controlled trials on the efficacy of SCPs on patient-reported and health services outcomes have included YBCS, but none have focused on reproductive health [19,17,20,21].

The web-based Survivorship Care Plan in Reproductive Health (SCP-R) intervention was developed to address unmet informational and clinical management needs for hot flashes, fertility-related concerns, contraception, and sexual health in YBCS. Research findings, professional society guidelines and clinical expertise on these reproductive health issues were curated into screening and management strategies that will be delivered to YBCS and their HCPs via the SCP-R intervention. A web-based intervention and text message support were chosen to enhance intervention accessibility.

This report details the design, recruitment, and baseline characteristics of YBCS and HCP participants of the randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of the SCP-R intervention on improving reproductive health in YBCS. We hypothesize that YBCS who receive the SCP-R intervention will be more likely to improve on at least one of four targeted reproductive health outcomes (hot flashes, fertility-related concerns, sexual health, and contraception) compared to attention controls.

Material and Methods

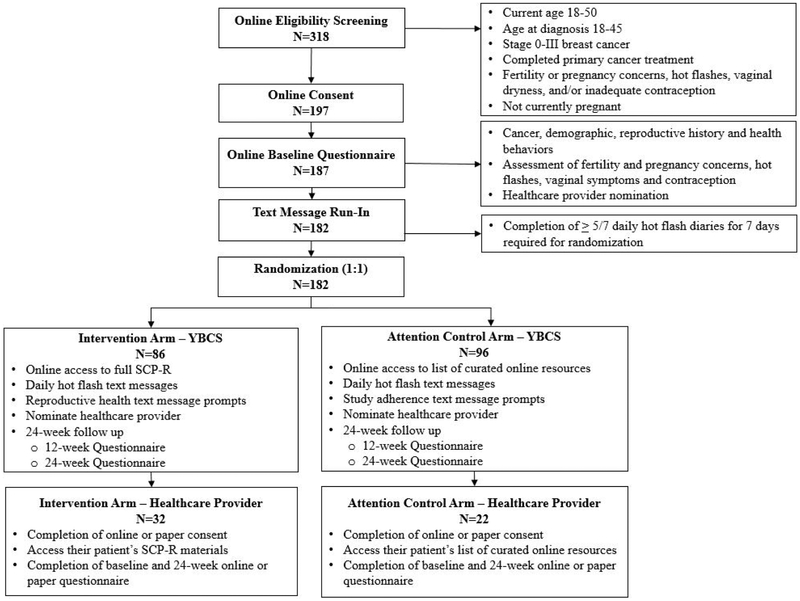

The SCP-R trial will test the efficacy of a 24-week, web-based educational intervention with text message support in improving reproductive health issues experienced by female YBCS. Figure 1 depicts an overview of the study. Following online eligibility screening and consent, YBCS complete an enrollment questionnaire and undergo a 7-day run-in period for reporting daily hot flash frequency and severity via text messaging. Adherent participants are randomized in a 1:1 ratio to the intervention or attention control arm. Participants in the intervention arm receive access to the full web-based SCP-R intervention and reproductive health text message prompts, while participants in the attention control arm receive access to a list of curated web-based resources and study adherence text messages. The two groups will receive the same number of contacts and duration of study, but will vary in the content of the web-based materials All participants will be followed for 24 weeks, report daily hot flash frequency and severity via text messaging, and complete a 12-week and a final 24-week questionnaire.

Figure 1:

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram for young breast cancer survivor (YBCS) and healthcare provider (HCP) participants

To support YBCS-HCP interactions, one HCP is nominated by each YBCS participant to receive the same study materials as their patient. Following eligibility screening and consent online or by paper, HCP participants whose YBCS patients are randomized to the intervention arm will receive access the full web-based educational intervention; HCP participants whose YBCS patients are randomized to the attention control arm will receive access to the list of curated web-based resources. HCP participants will complete an enrollment and a 24-week questionnaire. The UC San Diego institutional review board approved all study procedures, and the trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov ().

Intervention prototype development and refinement

In line with community-based participatory research [22], a stakeholder panel was formed to design and conduct the study. The panel was comprised of 2 YBCS advocates and 6 investigators with clinical and research expertise in reproductive health, primary care, breast oncology, health behavior and randomized trials. To develop the intervention, we conducted systematic reviews and searched professional medical society guidelines for evidence on managing hot flashes and sexual health, addressing contraception needs and predicting fertility potential [23-25]. Supplemented by clinical expertise and review of existing web-based resources from professional medical societies and cancer advocacy groups, these evidence- and guideline-based practices were summarized into the SCP-R prototype. SCP-R was designed to improve self-efficacy by providing both up-to-date evidence and actionable steps for symptom management. The multi-level intervention further promoted taking actionable steps by incorporating reinforcement from the YBCS’ HCP.

Seven focus groups with 37 YBCS were conducted to refine the content and presentation of the SCP-R [26]. For the intervention arm, we initially planned to provide each participant with only the SCP-R sections relevant to her specific reproductive issue(s). Based on focus group feedback, we changed the intervention design to allow participants in the intervention arm to access to all SCP-R sections.

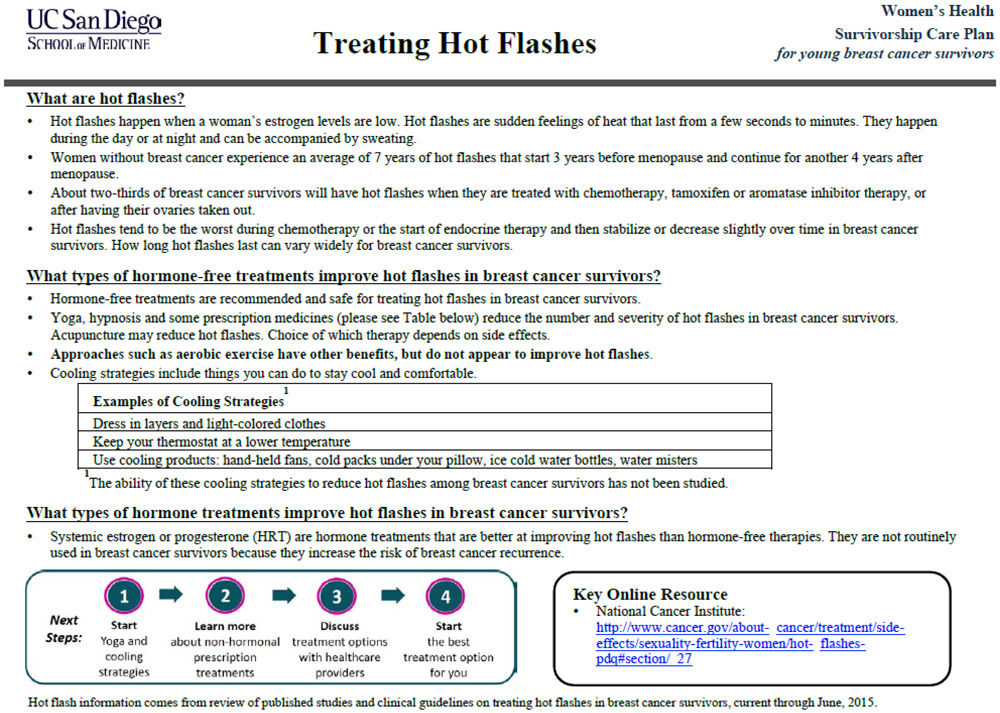

The final SCP-R intervention included four sections for each of the four planned reproductive health issue (hot flashes, fertility-related concerns, vaginal symptoms and contraception) and an additional fifth issue on genetic cancer risk. For each issue, the four sections included: 1) a 1- to 2-page SCP framed in a question and answer format; 2) a detailed summary of the systematic review results with hyperlinks to primary research articles; 3) a summary of clinical guidelines with hyperlinks; 4) a list of curated web-based resources. This content was programmed into the study website. The intervention arm will be able to access all 4 sections for all 5 issues (Appendix A); the attention control arm will only be able to access the list of curated web-based resources for all 5 issues.

Website and text messaging platforms

We collaborated with an experienced web architect to develop a HIPAA-compliant website that enabled online participant registration, consent, completion of questionnaires, automated randomization and access to group-specific intervention material, integration with MOSIO, a text messaging software, and pairing of YBCSs with their nominated HCPs [27]. The web portal is programmed to send study gift cards and weekly reminders on incomplete tasks to YBCS and HCP participants.

The text messaging platform is programmed to push daily text messages to all YBCS participants to ascertain hot flash frequency and severity. Natural language processing is embedded to minimize variation in how participants provide hot flash responses. Biweekly text messages with reproductive health prompts, which encompass tips for managing a symptom, will be sent to YBCS participants in the intervention arm. An example is, “Anti-depressants like venlafaxine (75 mg daily) have been shown to reduce hot flash frequency and severity. Contact your healthcare provider this week to discuss venlafaxine.” At the same time, study adherence text messages, reminding participants to complete study tasks, will be sent to YBCS participants in the control arm to standardize number of contacts between groups. The text messaging platform supports two-way communication between participants and study staff and provides participants the option to decline future receipt of text messages at any point during the study.

This web- and text message-based design supports streamlined YBCS screening, consent, follow-up, and data collection, enables geographically diverse recruitment and utilizes fewer resources compared to a traditional in-person RCTs. Daily hot flash text messages will provide near real-time data collection to minimize recall bias.

YBCS eligibility, recruitment, consent and enrollment

YBCS are eligible if they report experiencing at least one of the four targeted reproductive health issues: hot flashes (≥ 4 per day with ≥ 1 at least moderate in severity), moderate to high pregnancy and/or fertility concerns (fertility or pregnancy subscale score >3 on the Reproductive Concerns After Cancer Scale), not using contraception or using a less effective method (barrier or fertility awareness methods, withdrawal, or spermicides), or vaginal atrophy symptoms (≥ 1 symptom of vaginal dryness, irritation, soreness or dyspareunia over the past 4 weeks reported as at least moderate in severity) [28-34]. Additional eligibility criteria include: ages 18-50 at study enrollment, diagnosed with stage 0-III breast cancer between ages 18-45, completed primary cancer treatment including surgery, chemotherapy and radiation (participants currently on endocrine therapy were not excluded), are not pregnant at enrollment, are able to read English and access the Internet, and are able to complete daily text message hot flash diaries.

YBCS are recruited from the following sources: (1) cancer advocacy organizations including the Young Survival Coalition, Susan G. Komen San Diego and Army of Women-a program by the Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation, (2) referrals from health care providers and patient advocates, (3) Research Match, (4) previous observational studies conducted by the investigators. Interested YBCS are directed to the study web portal to create a secure personal account, followed by online access to study description, screening for eligibility and consent.

Consented participants complete the enrollment questionnaire and undergo a 7-day daily hot flash text message run-in period. Participants receive two daily text messages prompting them to report the number of hot flashes and severity of each hot flash (mild, moderate, severe, or very severe) in the previous 24 hours. Participants with at least 70% adherence over 7 days are then randomized.

YBCS randomization

Computerized, blocked randomization with equal allocation to intervention and attention control arms was undertaken. Randomization is stratified by the four a priori reproductive health issues in order to maintain balance between the intervention and attention control groups with regard to these factors. Fifteen unique strata were created based on possible combinations of experiencing one or more of the four late effects.

HCP eligibility, recruitment, consent, enrollment and procedures

At enrollment, each YBCS participant nominates a HCP with whom they wish to discuss reproductive health issues. Study staff contact nominated HCPs by email, phone and/or fax for study recruitment. After five contacts, non-responsive HCPs are mailed the study consent, enrollment questionnaire and their patient’s SCP materials. Interested HCPs are directed to the study web portal to create a secure personal account, followed by online access to study description, screening for eligibility and consent. Consented HCP participants complete the enrollment questionnaire and are provided with access to their patient’s intervention materials, i.e. full SCP-R or only curated web-based resource lists. HCPs will complete a 24-week questionnaire and may opt to complete all study procedures (consent, questionnaires) and access intervention materials in a paper format.

Blinding

Study staff, YBCS and HCP participants are blinded to treatment allocation. Automated computer allocation of participants into intervention or attention control arm within the study portal allow for study staff to be blinded to assignment. YBCS and HCP participants are informed about participant randomization in the trial but are not notified of assignment until they complete their final study tasks. YBCS and HCP participants assigned to the attention control arm will be able to access the full SCP-R materials following completion of their final study tasks. Although 3 HCPs were nominated by more than one YBCS participant, each HCP only had participants in the same study arm.

YBCS outcome measures

Hot flash frequency and severity over the prior 24 hours will be measured in each questionnaire and via daily text messages using the following questions: “How many hot flashes have you had in the past 24 hours?” and “How many of your hot flashes in the past 24 hours would you categorize as mild, moderate, severe and/or very severe?” The hot flash score is calculated as the weighted sum of the number of hot flashes in each severity category multiplied by a severityexclusive weight (1-mild, 2-moderate, 3-severe, 4-very severe) [35]. For the primary analysis, a decrease of 50% in the hot flash score will be defined as an improvement in hot flashes for the primary composite outcome. Secondary hot flash outcomes will include quality of life measured by the 29-item Menopause-specific Quality of Life (MENQOL) scale [36], confidence to talk with a HCP about hot flash management, plans to implement and implementation of a suggested tip from the intervention materials.

Fertility-related concerns will be measured with the Reproductive Concerns After Cancer Scale (RCAC), specifically fertility potential and pregnancy subscales. The RCAC is an 18-item multidimensional scale composed of 6 subscales (fertility potential, pregnancy, child’s health, disclosure to partner of fertility status, personal health, acceptance of infertility) measuring reproductive health concerns of young adult female cancer survivors [37]. The two subscales were chosen, because the SCP-R content addressed these constructs. Each subscale consists of 3 questions with response options ranging from 1 “Strongly disagree” to 3 “Neither agree nor disagree” to 5 “Strongly agree”. Scores for the fertility and pregnancy subscales will be calculated by averaging responses (range 1-5), scores > 3 indicating concern. For the primary analysis, scores < 3 in follow up will be considered an improvement in fertility-related concerns for the primary composite outcome. Secondary fertility-related outcomes will include the overall RCAC score, referral, consultation and treatment with a fertility specialist, pregnancy planning, and confidence to talk with a HCP about fertility-related concerns and plans to implement and implementation of suggestions from the fertility SCP.

Contraception outcomes will be analyzed in participants at risk of unintended pregnancy, defined as having a uterus and at least one ovary, sexually active in the 24 months prior to or during the study, < 45 years old. For the primary analysis, use of highly effective birth control methods (intrauterine devices, female sterilization, male partner sterilization, combined hormonal contraception, progestin implants or injections) during follow up will be considered an improvement for the primary composite outcome [38,39]. Secondary contraceptive outcomes will include confidence to talk with a HCP about contraception, plans to implement and implementation of suggestions from the contraception SCP.

Sexual health will be measured the Vaginal Atrophy Symptoms Score, a 4-item scale on vaginal dryness, soreness, irritation and dyspareunia experienced in the prior 4 weeks [29]. Each item has a 4-point Likert scale response (0-none, 1-mild, 2-moderate, 3-severe). The scale will be summarized by averaging responses, with higher scores indicating a greater level of vaginal atrophy. For the primary analysis, a decrease of 50% in the score will be defined as an improvement in vaginal symptoms for the primary composite outcome. Secondary outcomes included sexual desire, arousal, orgasm and pain via the 19-item Female Sexual Function Inventory (FSFI) [40], confidence to talk with a HCP about vaginal symptoms and sexual health management, plans to implement and implementation of a suggested tip from the intervention materials.

In addition to symptom and clinical outcomes, multiple process outcomes will be measured at 12 and 24 weeks, including whether and which reproductive health tips participants undertook and whether they accessed their healthcare provider to address their reproductive health issue(s). At 24 weeks, satisfaction and usefulness of their intervention materials will also be measured, and any additional feedback will be solicited. Unfortunately, our study portal does not accommodate measuring dose, e.g. how often and for how long study materials are accessed.

HCP measures

HCP preparedness and confidence in talking to their patients about each of the four reproductive health issues will be measured. Each preparedness item had a 4-point Likert scale response (very unprepared, unprepared, prepared, and very prepared). Each confidence item had a 7-point Likert scale response (not at all confident, slightly confident, somewhat confident, moderately confident, quite confident, very confident, and extremely confident). Demographic, medical specialty, and experience and volume of breast cancer patients seen per year were measured. In the 24-week questionnaire, we will also ask providers to rate their intervention materials’ usefulness in helping to manage their patient’s reproductive health issues, how likely they are to recommend the material to other providers, and to provide any additional comments and feedback.

YBCS participant adherence and retention

We will deploy several approaches to motivate YBCS participants to complete the study. Participants will receive up to $100 in Amazon gift cards for completing each of 3 questionnaires and daily hot flash text messages. Weekly, automated reminder emails to complete study tasks will be sent via the web platform. Telephone call and/or text message reminders will be undertaken for overdue tasks for up to 5 contacts. On hot flash text messages, daily reports will be generated to monitor responses and identify those who have not responded in > 3 consecutive days for study staff contact.

HCP participant adherence and retention

HCP participants will receive up to $40 in Amazon gift cards for completing each of 2 questionnaires. Weekly, automated email reminders to complete study tasks and view their patient’s SCP will be sent via the website platform. HCPs who opted to participate via paper materials will be contacted by telephone calls to their medical practice to confirm receipt and encourage completion of overdue tasks for up to 5 contacts. If a final questionnaire is not received within two months of mailing, questionnaires will be resent.

Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis will be intent-to-treat. The primary composite outcome will be an improvement in at least one reproductive health issue over the 24 week study, defined as: ≥ 50% improvement in enrollment hot flash score, ≥ 50% improvement in enrollment vaginal atrophy symptom score, use of highly effective contraceptive methods (sterilization, long-acting reversible contraception, injectables, pills, patch or vaginal ring), and fertility and pregnancy concern subscale scores <3. Logistic regression models will be used to test for differences by intervention versus control arm; odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for intervention effect will be reported.

To quantify intervention effects on each of the four reproductive health issues, we will also undertake secondary analyses to compare changes in each issue separately in which only participants who experience the respective concern will be included. As participant responses will be measured at enrollment, 12 and 24 weeks, we will compare each health issue outcome between the intervention and attention control groups using linear mixed effect models for the continuous outcomes (hot flash score, vaginal atrophy symptom score, fertility concerns score) and GEE models for binary outcomes (use of effective contraceptive method) . Best linear unbiased predictors from the mixed models will also be used to impute missing outcomes for the primary composite outcome. Similar analysis will be conducted for secondary outcomes, which include additional YBCS-reported symptoms and actions, as well as healthcare provider preparedness and confidence.

Sample size

YBCS participants will be randomized into two arms: intervention and attention control. We will measure outcomes at enrollment, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks. Leveraging published data on hot flashes [31], we based sample-size calculations on detecting meaningful changes in hot flash frequency and score. With a sample size of 50/arm, there will be 80% power to detect a 0.57 effect-size between groups on hot flash score changes from baseline to 24 weeks based on a 2-sided t-test with alpha =0.05. This effect-size translates to a group difference of 1.2 hot flashes or 3 units in the hot flash score, if we assume the standard deviation of the change was 2 hot flashes or 5 score units per patient per day. Incorporating all the repeated measurements on each participant should ensure sufficient power to detect an even smaller effect size. In particular, assuming 2 post-randomization measures with autocorrelation 0.5, there is 80% power to detect a 0.44 effect size with 50 samples in each arm and 2-sided significance level 0.05.

Considering the composite primary outcome of improvement in at least 1 reproductive health issue, we have 80% power to detect a 27% group difference, e.g., 25% in the control arm and 52% in the treatment improve on at least one outcome. Given that some participants may have the same healthcare provider, we account for a clustering effect as follows: we assume as a worst-case scenario that on average 3 participants shared a provider, and that intraclass correlations (ICC) of the study outcomes due to a shared physician is 0.1. This results in a design effect of 1.2, requiring us to inflate the sample-size by 20%. We further anticipate 20% sample size loss due to the run-in period prior to randomization, and an additional 20% drop-out rate. Hence, we aim to enroll 196 participants and randomize 157 to ensure sufficient power.

Results

Enrollment occurred between March, 2016 and April, 2017, during which 318 individuals underwent eligibility screening, and 182 YBCS underwent randomization (Figure 1.) The majority of YBCS who underwent eligible screen (82.7%) met criteria for at least one reproductive health late effect. Participants were recruited from cancer advocacy organizations (61.5%), previous observational studies conducted by the investigators (13.7%), ResearchMatch (5.5%), HCP referrals (3.9%), word of mouth (3.9%), and other sources (11.5%). Participants live in 38 different states.

One hundred and thirty-six individuals were excluded due to the following reasons: did not meet criteria for reproductive health issue (n=55); ineligible cancer type or stage (n=23); ineligible age at diagnosis and/or enrollment (n=9); had not completed primary cancer treatment (n=6), pregnant (n=6); failed text message run-in (n=5). No significant differences were found in demographic or cancer related characteristics between participants who successfully completed the text message run in period and those who did not (p >0.05). Thirty-two eligible women declined to consent to participation.

Baseline characteristics for the overall YBCS population and by intervention arm are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1:

Enrollment characteristics of young breast cancer survivor participants

| Characteristic | Overall No. (%) (n=182) |

Intervention No. (%) (n=86) |

Control No. (%) (n=96) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment (y) | 0.24 | |||

| 25-30 | 13 (7.1) | 3 (3.5) | 10 (10.4) | |

| 31-35 | 38 (20.9) | 22 (25.6) | 16 (16.7) | |

| 36-40 | 48 (26.4) | 20 (23.3) | 28 (29.2) | |

| 41-45 | 54 (29.7) | 27 (31.4) | 27 (28.1) | |

| 46-50 | 29 (15.9) | 14 (16.3) | 15 (15.6) | |

| Race | 0.15 | |||

| Black or African American | 8 (4.4) | 1 (1.2) | 7 (7.3) | |

| White | 157 (86.3) | 77 (89.5) | 80 (83.3) | |

| Other race | 17 (9.3) | 8 (9.3) | 9 (9.4) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.75 | |||

| Hispanic | 10 (5.5) | 4 (4.7) | 6 (6.3) | |

| Not Hispanic | 172 (94.5) | 82 (95.4) | 90 (93.8) | |

| Relationship status | 0.17 | |||

| Partnered | 149 (81.9) | 74 (86.0) | 75 (78.1) | |

| Not partnered | 33 (18.1) | 12 (14.0) | 21 (21.9) | |

| Education | 0.83 | |||

| Did not complete college | 20 (11.0) | 9 (10.5) | 11 (11.5) | |

| College graduate | 162 (89.0) | 77 (89.5) | 85 (88.5) | |

| Incomea | 0.29 | |||

| <$51,000 | 25 (14.6) | 10 (11.8) | 15 (17.4) | |

| ≥$51,000 | 146 (85.4) | 75 (88.2) | 71 (82.6) | |

| BMI | 0.02 | |||

| <18.5 | 7 (3.8) | 4 (4.7) | 3 (3.1) | |

| 18.5-24.9 | 82 (45.1) | 34 (39.5) | 48 (50.0) | |

| 25-29.9 | 49 (26.9) | 32 (37.2) | 17 (17.7) | |

| ≥30 | 44 (24.2) | 16 (18.6) | 28 (29.2) | |

| Age at diagnosis | 0.95 | |||

| 18-24 | 4 (2.2) | 2 (2.3) | 2 (2.1) | |

| 25-35 | 86 (47.2) | 40 (46.5) | 46 (47.9) | |

| 36-45 | 92 (50.6) | 44 (51.2) | 48 (50.0) | |

| Years since diagnosis | 0.51 | |||

| <1 | 20 (11.0) | 9 (10.5) | 11 (11.5) | |

| 1-2 | 52 (28.6) | 27 (31.4) | 25 (26.0) | |

| 3-5 | 47 (25.8) | 18 (20.9) | 29 (30.2) | |

| >5 | 63 (34.6) | 32 (37.2) | 31 (32.3) | |

| Cancer treatment | ||||

| Surgery | 180 (98.9) | 85 (98.8) | 95 (99.0) | 1.0 |

| Radiation | 124 (68.1) | 54 (62.8) | 70 (72.9) | 0.14 |

| Chemotherapy | 156 (85.7) | 72 (83.7) | 84 (87.5) | 0.47 |

| Biologic therapy | 48 (26.4) | 22 (25.6) | 26 (27.1) | 0.82 |

| Hormone therapy | 142 (78.0) | 67 (77.9) | 75 (78.1) | 0.97 |

| Cancer stagea | 0.17 | |||

| 0 | 10 (5.6) | 8 (9.5) | 2 (2.1) | |

| 1 | 49 (27.2) | 21 (25.0) | 28 (29.1) | |

| 2 | 81 (45.0) | 38 (45.3) | 43 (44.8) | |

| 3 | 40 (22.2) | 17 (20.2) | 23 (24.0) | |

| Cancer Recurrence | 7 (3.8) | 6 (7.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0.05 |

| Hysterectomy | 19 (10.4) | 9 (10.5) | 10 (10.4) | 0.99 |

| Oophorectomy | ||||

| Unilateral | 5 (2.7) | 2 (2.3) | 3 (3.1) | 1.0 |

| Bilateral | 32 (17.6) | 13 (15.1) | 19 (19.8) | 0.41 |

| Menses past year | 0.98 | |||

| 0 | 78 (42.9) | 36 (41.9) | 42 (43.7) | |

| 1-3 | 35 (19.2) | 16 (18.6) | 19 (19.8) | |

| 4-9 | 36 (19.8) | 18 (20.9) | 18 (18.8) | |

| 10-12 | 33 (18.1) | 16 (18.6) | 17 (17.7) |

Numbers do not sum up to 182 due to participants selecting prefer not to answer or unknown

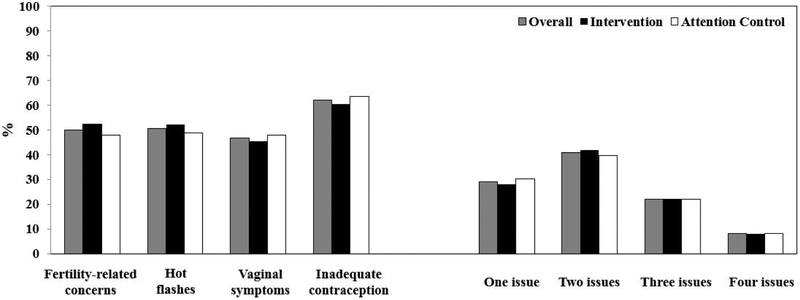

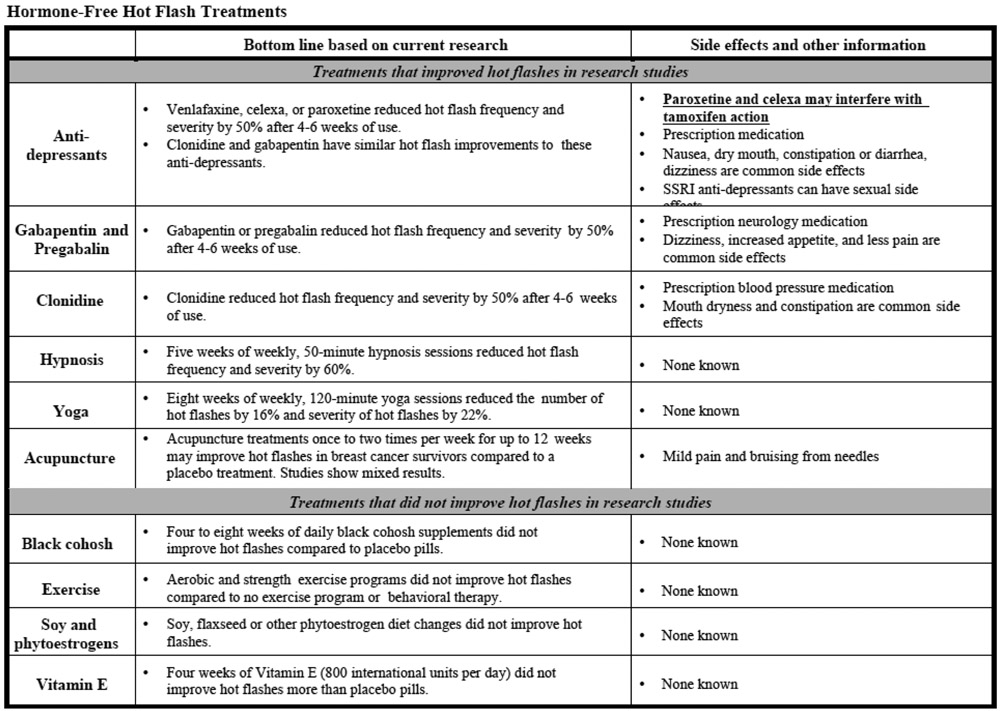

The mean age (standard deviation) of YBCS was 40.0 (5.9) years. No participants were younger than 25. The majority were white (86.3%), non-Hispanic (94.5%) and college graduates (89.0%). Mean age at breast cancer diagnosis was 35.6 (5.4) years. The majority of participants underwent surgery, chemotherapy, radiation and endocrine therapy. At baseline, significant hot flashes, fertility-related concerns, vaginal symptoms, and inadequate contraception were reported by 50.5%, 50%, 46.7%, 62.1% of participants, respectively (Figure 2). Moreover, 70.9% of participants reported more than one reproductive health issue. Randomization led to similar distributions of baseline characteristics and reproductive health issues between the intervention and attention control arms. Although the four categories of body max index revealed significant differences between the study arms, the proportion of overweight/obese vs. nonoverweight/obese was comparable (Table 1, Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Proportions of young breast cancer survivor participants with each reproductive health issues and total number of reproductive issues by intervention arm

YBCS participants nominated 165 unique HCPs, of which 54 (32.7%) were enrolled following repeated recruitment attempts (Figure 1). Enrolled HCPs responded to recruitment contacts in the following distribution: 1 attempt (9.2%), 2 attempts (16.7%), 3 attempts (25.9%), 4 attempts (24.1%), and 5 attempts (24.1%). The majority of HCPs (85.2%) preferred being mailed study materials and completing questionnaires in the paper format; only 8 chose to use the web-based platform. Baseline characteristics are depicted in Table 2.

Table 2:

Enrollment characteristics of healthcare provider participants

| Characteristic | Overall No. (%) (n=54) |

Intervention No. (%) (n=31) |

Control No. (%) (n=23) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | |||

| 30-39 | 12 (22.2) | 8 (25.8) | 4 (17.4) |

| 40-49 | 20 (37.0) | 10 (32.3) | 10 (43.5) |

| 50-59 | 17 (31.5) | 10 (32.3) | 7 (30.4) |

| ≥60 | 5 (9.3) | 3 (9.6) | 2 (8.7) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 10 (18.5) | 5 (16.1) | 5 (21.7) |

| Female | 44 (81.5) | 26 (83.9) | 18 (78.3) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black Non-Hispanic | 2 (3.7) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (4.4) |

| White Non-Hispanic | 45 (83.3) | 26 (83.9) | 19 (82.6) |

| Other Non-Hispanic | 7 (13.0) | 4 (12.9) | 3 (13.0) |

| Profession | |||

| Medical doctor | 40 (74.1) | 22 (71.0) | 18 (78.3) |

| Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine | 5 (9.3) | 4 (12.9) | 1 (4.4) |

| Nurse Practitioner | 7 (13.0) | 3 (9.7) | 4 (17.4) |

| Physician Assistant | 1 (1.8) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Registered Nurse | 1 (1.8) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Specialty | |||

| Oncology | 25 (46.3) | 12 (38.7) | 13 (56.5) |

| Family or Internal medicine | 12 (22.2) | 9 (29.0) | 3 (13.0) |

| Obstetrics/Gynecology | 15 (27.8) | 9 (29.0) | 6 (26.1) |

| Psychiatry/Psychology | 2 (3.7) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (4.4) |

| Time practicing medicine post residency (y) | |||

| <15 | 28 (51.8) | 17 (54.8) | 11 (47.8) |

| ≥15 | 26 (48.1) | 14 (45.2) | 12 (52.2) |

| Time treating breast cancer patients (y) | |||

| <15 | 31 (57.4) | 17 (54.8) | 14 (60.9) |

| ≥15 | 23 (42.6) | 14 (45.2) | 9 (39.1) |

| Number of breast cancer patients seen per year | |||

| ≤20 | 23 (42.6) | 15 (48.4) | 8 (34.8) |

| 21-40 | 10 (18.5) | 6 (19.3) | 4 (17.4) |

| >40 | 21 (38.9) | 10 (32.3) | 11 (47.8) |

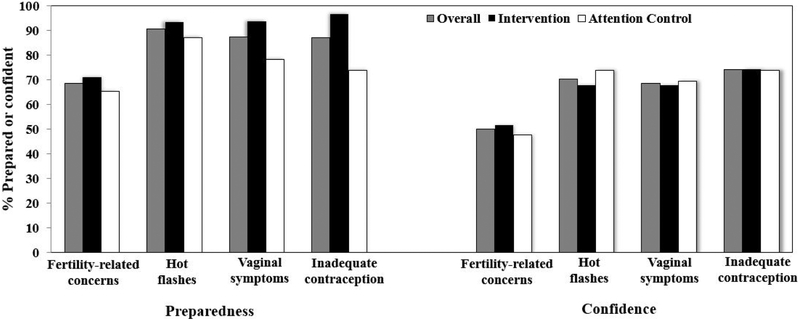

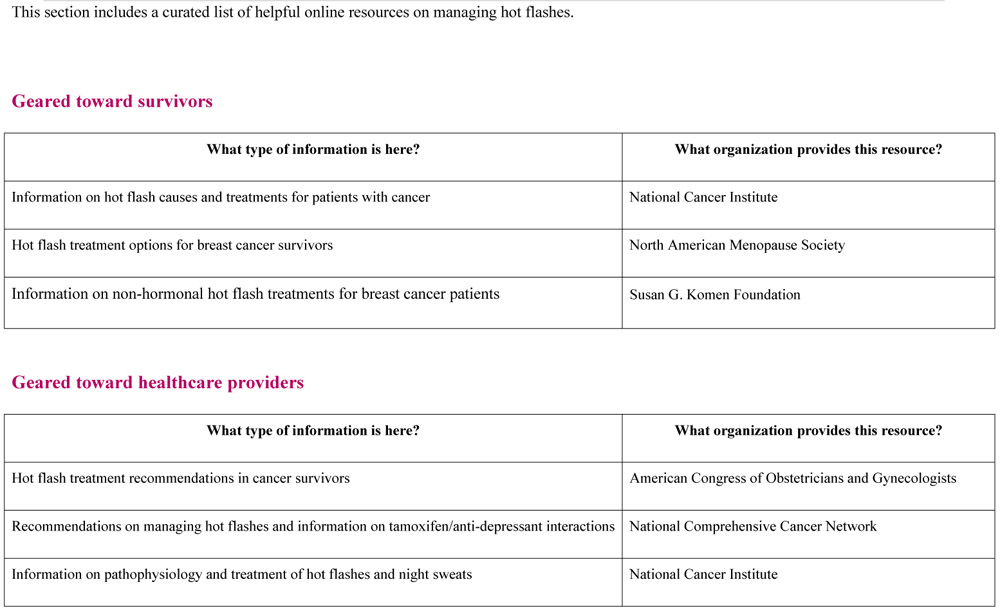

Most HCP participants were female, white and a physician in oncology or gynecology. At enrollment, the majority of HCPs reported that they were prepared or very prepared and at least quite confident in discussing each reproductive health issue with their patients (Figure 3). Among the reproductive health issues, HCPs were least likely to report preparedness or confidence in discussing fertility-related concerns. Randomization led to similar distributions of baseline characteristics, preparedness and confidence between HCPs whose YBCS patients were randomized to the intervention arm and those whose YBCS patients were randomized to the attention control arm.

Figure 3:

Health care provider participants report of preparedness and confidence in discussion each reproductive health issue with young breast cancer survivors, by intervention arm. Preparedness was dichotomized as prepared and very prepared, compared to unprepared and very unprepared. Confidence was dichotomized as quite/very/extremely confident, compared to not at all/slightly/somewhat/moderate confident.

Discussion

YBCS are at risk of reproductive health issues after breast cancer treatment and have unmet informational and symptom management needs [14-16]. We hypothesize that disseminating up-to-date information on evaluating and managing these late effects via a survivorship care plan intervention targeting both YBCS and their healthcare providers will improve the reproductive health of these young women. The intervention and trial were designed with stakeholder input and aimed to improve self-efficacy. The use of a web-based intervention with text message support enables geographically diverse YBCS to access the trial and real-time data collection.

Estrogen deprivation symptoms, fertility-related concerns, limited contraception, and sexual dysfunction are major reproductive health issues in YBCS that are associated with poorer quality of life [41,42]. These late effects occur largely because chemotherapy and/or endocrine therapy disrupt normal ovarian function, chemotherapy via direct toxicity to ovarian follicles and endocrine therapy via modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis [43,44]. Furthermore, YBCS have limited contraception options, because breast cancers expressing estrogen or progesterone receptors preclude the use of hormonal contraception leading to underuse of highly effective contraception to prevent unintended pregnancy [45]. The unmet gap in reproductive health care is supported by our observation that the majority of YBCS who screened for eligibility had at least one reproductive health issue. A considerable body of research and professional society guidelines on assessing and managing these reproductive health issues has been generated, but lacks broader dissemination [23-25].

The goal of the SCP-R intervention is to influence the health behavior of YBCS to improve their reproductive health. To this end, the survivorship care plan mechanism was chosen, because SCPs have been recommended by the Institute of Medicine and multiple general SCPs have been developed to which an effective reproductive health module could be added. A multi-level intervention involving both YBCS and her HCP was selected, because evaluation and management of these late effects frequently requires significant interactions between the patient and those who exert primary levels of influence on her reproductive health decisions [46,47].

Stakeholder engagement was central to the study, from intervention design to conduct of the clinical trial. Healthcare providers, patient advocates and advocacy groups provided invaluable feedback on participant recruitment and engagement strategies and dissemination methods. Their guidance increased the relevance and accessibility of the intervention to YBCS. Given that rates of breast cancer are lower in women under the age of 40, it was important to partner with advocacy groups that specialize in engaging this population. Our partners utilized social media to reach and highlight the relevance of the study to this reproductive aged population. Future research in young breast cancer survivors will likely benefit from actively involving stakeholders throughout the research process as this may increase the likelihood that programs are appropriate and clinically applicable to YBCS and their HCPs.

The use of a web-based intervention provided several advantages. The entire study was conducted remotely, allowing participants to engage from all over the country and in their home environment. This supported geographically broad recruitment and low resource utilization, enabling wider dissemination in the future. Text messaging for hot flash data acquired patient recorded outcomes in near real-time, decreasing recall bias [48,49]. For these young women, text messaging in pre-specified formats could be completed by the majority, as very few failed the run-in period. We plan to ascertain qualitative feedback from participants on text message capture of hot flash burden.

Several limitations need to be discussed. Participants were mostly white and educated, limiting the generalizability of the trial. All study materials were in English, precluding YBCS who are not fluent. Additional counseling was not required in the proposed model, which may be disadvantageous with the emergence of SCP trials that showed counseling in addition to SCP provision improves adherence to screening recommendations [50]. Although the study utilizes previously published HCP recruitment strategies including nomination of a provider by their patient, peer outreach by clinician investigators of the trial, incentives and multiple modalities for participation, recruitment was nonetheless challenging [51-53]. For this reason, it may be advantageous to integrate reproductive health needs in survivorship care into early trainings for healthcare providers such as health professional school and residency curriculum [54]. To assist providers who have already completed training, active dissemination of clinical practice guidelines and integration of survivorship care plans for managing reproductive late effects in YBCS is important. In addition, 16% of our sample was comprised of non-physician healthcare providers who may be in a position to play a meaningful role in conducting routine follow up on reproductive health late effects in YBCSs.

Conclusions

A novel reproductive health educational intervention for young women with breast cancer was generated and deployed via a web-based platform with text messaging. Conducting a trial for improving reproductive health in survivorship online is feasible in YBCS, providing a mechanism to broadly disseminate evidence-based management.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the California Breast Cancer Research Program Translational Award 20OB-0144 (all authors) and P30-CA008748 (JM). The funders had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript and decision to submit the article for publication.

Abbreviations:

- YBCS

Young Breast Cancer Survivors

- HCP

healthcare providers

- SCP

Survivorship Care Plan

- SCP-R

Survivorship Care Plan for Reproductive Health

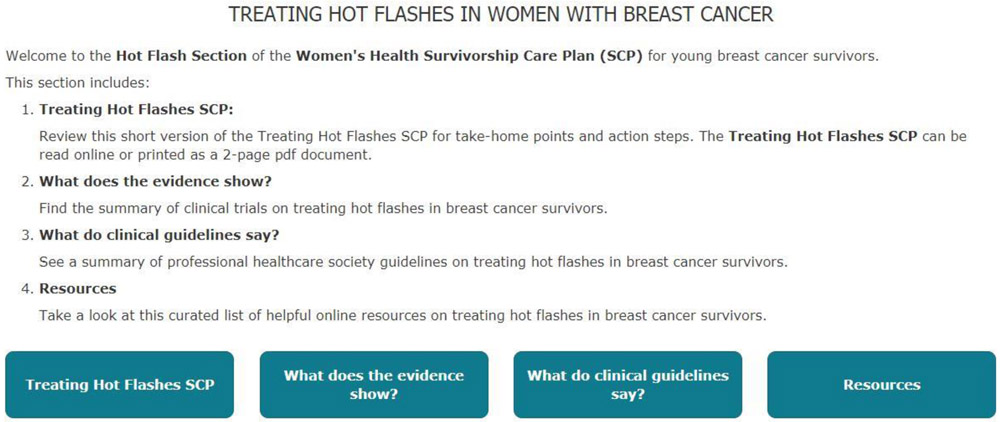

Appendix A:

Sample of SCP-R content (SCP and Resources) on hot flashes for participants randomized to the Intervention arm. Similar material are provided for fertility-related concerns, contraception, sexual health and cancer genetic risk. Participants randomized to the Attention Control arm were only able to access the list of curated web-based resources with hyperlinks.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: All authors state that they have no actual or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationship with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could have inappropriately influenced, or perceived to influence their work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].American Cancer Society, Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2017-2018, 2017. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2017-2018.pdf (accessed April 2, 2018).

- [2].Su HI, Sammel MD, Green J, Velders L, Stankiewicz C, Matro J, Freeman EW, Gracia CR, DeMichele A, Antimullerian hormone and inhibin B are hormone measures of ovarian function in late reproductive-aged breast cancer survivors., Cancer. 116 (2010) 592–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Maloney EK, D’Agostino TA, Heerdt A, Dickler M, Li Y, Ostroff JS, Bylund CL, Sources and types of online information that breast cancer patients read and discuss with their doctors, Palliat. Support. Care. 13 (2015) 107–114. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513000862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mayer EL, Gropper AB, Neville B. a, Partridge AH, Cameron DB, Winer EP, Earle CC, Breast cancer survivors’ perceptions of survivorship care options., J. Clin. Oncol 30 (2012) 158–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.9264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gorman JR, Bailey S, Pierce JP, Su HI, How do you feel about fertility and parenthood? The voices of young female cancer survivors, J. Cancer Surviv. 6 (2012) 200–209. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0211-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tan ASL, Moldovan-Johnson M, Gray SW, Hornik RC, Armstrong K, An Analysis of the Association between Cancer-Related Information Seeking and Adherence to Breast Cancer Surveillance Procedures, Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 22 (2013) 167–174. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mayer DK, Terrin NC, Kreps GL, Menon U, McCance K, Parsons SK, Mooney KH, Cancer survivors information seeking behaviors: A comparison of survivors who do and do not seek information about cancer, Patient Educ. Couns. 65 (2007) 342–350. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nguyen SKA, Ingledew PA, Tangled in the breast cancer web: An evaluation of the usage of webbased information resources by breast cancer patients, J. Cancer Educ. 28 (2013) 662–668. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0509-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hewitt ME, Ganz P, Institute of Medicine (U.S.), Lance Armstrong Foundation., National Cancer Institute (U.S.), National Cancer Policy Forum (U.S.), National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (U.S.), Implementing cancer survivorship care planning : workshop summary, National Academies Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [10].American Society of Clinical Oncology, ASCO Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Care Plans, (n.d.). https://www.cancer.net/survivorship/follow-care-after-cancer-treatment/asco-cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-care-plans (accessed April 10, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- [11].National Cancer Institute, NCI Community Cancer Centers Program Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Plan, (n.d.). http://prc.coh.org/Survivorship/NCCCPASCOBCSCP.pdf (accessed April 10, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hausman J, Ganz PA, Sellers TP, Rosenquist J, Journey forward: the new face of cancer survivorship care., J. Oncol. Pract. 7 (2011) e50s–6s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Boekhout AH, Maunsell E, Pond GR, Julian JA, Coyle D, Levine MN, Grunfeld E, Boekhout AH, Grunfeld E, Pond GR, Julian JA, Levine MN, Coyle D, A survivorship care plan for breast cancer survivors: extended results of a randomized clinical trial, J Cancer Surviv. 9 (2015) 683–691. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0443-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Buske D, Sender A, Richter D, Brähler E, Geue K, Patient-Physician Communication and Knowledge Regarding Fertility Issues from German Oncologists’ Perspective—a Quantitative Survey, J. Cancer Educ. 31 (2016) 115–122. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0841-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Thewes B, Meiser B, Taylor a, Phillips K. a, Pendlebury S, Capp a, Dalley D, Goldstein D, Baber R, Friedlander ML, Fertility- and menopause-related information needs of younger women with a diagnosis of early breast cancer., J. Clin. Oncol 23 (2005) 5155–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Peate M, Meiser B, Hickey M, Friedlander M, The fertility-related concerns, needs and preferences of younger women with breast cancer: A systematic review, Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 116 (2009) 215–223. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Pond G, Maunsell E, Coyle D, Folkes A, Joy AA, Provencher L, Rayson D, Rheaume DE, Porter GA, Paszat LF, Pritchard KI, Robidoux A, Smith S, Sussman J, Dent S, Sisler J, Wiernikowski J, Levine MN, Evaluating survivorship care plans: results of a randomized, clinical trial of patients with breast cancer., J. Clin. Oncol 29 (2011) 4755–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hausman J, Ganz PA, Sellers TP, Rosenquist J, Journey forward: the new face of cancer survivorship care., J. Oncol. Pract. 7 (2011) e50s–6s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Boekhout AH, Maunsell E, Pond GR, Julian JA, Coyle D, Levine MN, Grunfeld E, Boekhout AH, Grunfeld E, Pond GR, Julian JA, Levine MN, Coyle D, A survivorship care plan for breast cancer survivors: extended results of a randomized clinical trial, J Cancer Surviv. 9 (2015) 683–691. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0443-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hershman DL, Greenlee H, Awad D, Kalinsky K, Maurer M, Kranwinkel G, Brafman L, Jayasena R, Tsai W-Y, Neugut AI, Crew KD, Randomized controlled trial of a clinic-based survivorship intervention following adjuvant therapy in breast cancer survivors, Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 138 (2013) 795–806. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2486-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Maly RC, Liang L-J, Liu Y, Griggs JJ, Ganz PA, Randomized Controlled Trial of Survivorship Care Plans Among Low-Income, Predominantly Latina Breast Cancer Survivors., J. Clin. Oncol 35 (2017) 1814–1821. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.9497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Community-based participatory research: Policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research, Educ. Heal. 14 (2001) 182–197. doi: 10.1080/13576280110051055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Johns C, Seav SM, Dominick SA, Gorman JR, Li H, Natarajan L, Mao JJ, Irene Su H, Informing hot flash treatment decisions for breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of randomized trials comparing active interventions, Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 156 (2016) 415–426. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3765-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gorman JR, Julian AK, Roberts SA, Romero SAD, Ehren JL, Krychman ML, Boles SG, Mao J, Irene Su H, Developing a post-treatment survivorship care plan to help breast cancer survivors understand their fertility, Support. Care Cancer. 26 (2018) 589–595. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3871-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Seav SM, Dominick SA, Stepanyuk B, Gorman JR, Chingos DT, Ehren JL, Krychman ML, Su HI, Management of sexual dysfunction in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review, (n.d.). doi: 10.1186/s40695-015-0009-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gorman JR, Julian AK, Roberts SA, Romero SAD, Ehren JL, Krychman ML, Boles SG, Mao J, Irene Su H, Developing a post-treatment survivorship care plan to help breast cancer survivors understand their fertility, Support. Care Cancer. 26 (2018) 589–595. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3871-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].MOSIO, (2018). http://www.mosio.com/.

- [28].Gorman JR, Su HI, Pierce JP, Roberts SC, Dominick SA, Malcarne VL, A multidimensional scale to measure the reproductive concerns of young adult female cancer survivors, J Cancer Surviv. 8 (2014) 218–228. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0333-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Davila GW, Are women with urogenital atrophy symptoms symptomatic?, Am J Obs. Gynecol. 188 (1067). doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lepkowski JM, Mosher WD, Davis KE, Groves RM, Van Hoewyk J, The 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth: sample design and analysis of a continuous survey., Vital Health Stat. 2 (2010) 1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sloan JA, Loprinzi CL, Novotny PJ, Barton DL, Lavasseur BI, Windschitl H, Methodologic lessons learned from hot flash studies., J. Clin. Oncol. 19 (2001) 4280–90. doi: 10.1200/JC0.2001.19.23.4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, Stemfeld B, Cohen LS, Joffe H, Carpenter JS, Anderson GL, Larson JC, Ensrud KE, Reed SD, Newton KM, Sherman S, Sammel MD, LaCroix AZ, Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in healthy menopausal women: a randomized controlled trial., JAMA. 305 (2011)267–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Joffe H, Guthrie KA, LaCroix AZ, Reed SD, Ensrud KE, Manson JAE, Newton KM, Freeman EW, Anderson GL, Larson JC, Hunt J, Shifren J, Rexrode KM, Caan B, Sternfeld B, Carpenter JS, Cohen L, Low-dose estradiol and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine for vasomotor symptoms: A randomized clinical trial, JAMA Intern. Med. 174 (2014) 1058–1066. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Loprinzi CL, Kugler JW, Barton DL, Dueck AC, Tschetter LK, Nelimark RA, Balcueva EP, Burger KN, Novotny PJ, Carlson MD, Duane SF, Corso SW, Johnson DB, Jaslowski AJ, Phase III trial of gabapentin alone or in conjunction with an antidepressant in the management of hot flashes in women who have inadequate control with an antidepressant alone: NCCTG N03C5, J. Clin. Oncol. 25 (2007) 308–312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sloan JA, Loprinzi CL, Novotny PJ, Barton DL, Lavasseur BI, Windschitl H, Methodologic Lessons Learned From Hot Flash Studies, J Clin Oncol. 19 (n.d.) 4280–4290. https://vpn.ucsd.edu/+CSCO+1h756767633A2F2F6E66706263686F662E626574++/doi/pdfdirect/10.1200/JCO.2001.19.23.4280 (accessed April 2, 2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hilditch JR, Lewis J, Peter A, Van Marls B, Ross A, Franssen E, Guyatt GH, Norton PG, Dunn E, A menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire: development and psychometric properties, Maturitas. 24 (1996) 161–175. http://www.maturitas.org/article/S0378-5122(96)82006-8/pdf (accessed April 4, 2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Gorman JR, Irene Su H, Pierce JP, Roberts SC, Dominick SA, Malcarne VL, A multidimensional scale to measure the reproductive concerns of young adult female cancer survivors, (n.d.). doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0333-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].WHO, World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research (WHO/RHR) and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs (CCP) Knowledge for Health Project. Family planning: a global handbook for providers, 2011. https://www.ippf.org/sites/default/files/family_planning_a_global_handbook_for_providers.pdf (accessed May 24, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- [39].Stanback J, Steiner M, Dorflinger L, Solo J, Cates W, WHO Tiered-Effectiveness Counseling Is Rights-Based Family Planning, (n.d.). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4570010/pdf/352.pdf (accessed May 24, 2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Rosen R, Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, Ferguson D, Goldstein I, Berman J, Fourcroy J, Laan E, Mitchel J, Hays J, Padma-Nathan H, Phillips N, The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A Multidimensional Self-Report Instrument for the Assessment of Female Sexual Function, J. Sex Marital Ther. 26 (2000) 191–208. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/009262300278597 (accessed April 4, 2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gorman JR, Malcarne VL, Roesch SC, Madlensky L, Pierce JP, Depressive Symptoms among Young Breast Cancer Survivors: The Importance of Reproductive Concerns, (n.d.). doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0768-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Letourneau JM, Ebbel EE, Katz PP, Katz A, Ai WZ, Chien AJ, Melisko ME, Cedars MI, Rosen MP, Pre-treatment fertility counseling and fertility preservation improve quality of life in reproductive age women with cancer, (n.d.). doi: 10.1002/cncr.26459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Jordan VC, Fritz NF, Langan-Fahey S, Thompson M, Tormey DC, Alteration of endocrine parameters in premenopausal women with breast cancer during long-term adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen as the single agent, J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 83 (1991) 1488–1491. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.20.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Warne GL, Fairley KF, Hobbs JB, Martin FI, Cyclophosphamide-induced ovarian failure., N. Engl. J. Med. 289 (1973) 1159–1162. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197311292892202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Dominick SA, Mclean MR, Whitcomb BW, Gorman JR, Mersereau JE, Bouknight JM, Su HI, Contraceptive Practices Among Female Cancer Survivors of Reproductive Age National Survey for Family Growth. Log-binomial regression models estimated relative risks for characteristics associated with use of contraception, World Health Organization HHS Public Access, Obs. Gynecol. 126 (2015) 498–507. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Stange KC, Breslau ES, Dietrich AJ, Glasgow RE, State-of-the-art and future directions in multilevel interventions across the cancer control continuum, J. Natl. Cancer Inst. - Monogr. (2012) 20–31. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB, Ecological models of health behavior, 2008. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-4-350_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Mayer DK, Nekhlyudov L, Snyder CF, Merrill JK, Wollins DS, Shulman LN, American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical expert statement on cancer survivorship care planning., J. Oncol. Pract 10 (2014) 345–51. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Birken SA, Mayer DK, Weiner BJ, Survivorship care plans: Prevalence and barriers to use, (n.d.). doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0469-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Hudson MM, Leisenring W, Stratton KK, Tinner N, Steen BD, Ogg S, Barnes L, Oeffinger KC, Robison LL, Cox CL, Leisen-ring W, Increasing Cardiomyopathy Screening in At-Risk Adult Survivors of Pediatric Malignancies: A Randomized Controlled Trial, J Clin Oncol. 32 (n.d.) 3974–3981. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Nekhlyudov L, O’malley DM, Hudson SV, Integrating primary care providers in the care of cancer survivors: gaps in evidence and future opportunities, Lancet Oncol. 18 (2017) e30–e38. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Dawes AJ, Hemmelgarn M, Nguyen DK, Sacks GD, Clayton SM, Cope JR, Ganz PA, Maggard-Gibbons M, Are primary care providers prepared to care for survivors of breast cancer in the safety net?, Cancer. 121 (2015) 1249–1256. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Signorelli C, Wakefield CE, Fardell JE, Thornton-Benko E, Emery J, McLoone JK, Cohn RJ, Recruiting primary care physicians to qualitative research: Experiences and recommendations from a childhood cancer survivorship study, Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 65 (2018) e26762. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Miller EJN, Cookingham LM, Woodruff TK, Ryan GL, Summers KM, Kondapalli LA, Shah DK, Fertility preservation training for obstetrics and gynecology fellows: a highly desired but nonstandardized experience, Fertil. Res. Pract. 3 (2017) 9. doi: 10.1186/s40738-017-0036-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]