Abstract

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which is curable in the majority of patients treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP) immunochemotherapy. However, the therapeutic mechanism of R-CHOP has not been elucidated. The GSE32918 and GSE57611 datasets were retrieved from The Gene Expression Omnibus database. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with R-CHOP therapy were identified using limma. Combined with prognostic information in GSE32918, DEGs found to be significantly associated with prognosis were selected using univariate Cox regression analysis and a risk prediction model was constructed. Based on this model, the samples in the training set (GSE32918) were divided into high and low risk score groups according to the median risk score. A total of 801 DEGs were identified between the R-CHOP treated DLBCL and primary DLBCL samples, from this 116 prognosis-associated genes were selected. Using Cox proportional hazards model, an optimal combination of 12 genes [including calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase I (CAMK1), hippocalcin like 4 (HPCAL4) and ephrin A5 (EFNA5)] was selected, and the sample risk score prediction model was constructed and validated. The DEGs between high risk score and low risk score groups were significantly enriched in functions associated with ‘response to DNA damage stimulus’, and pathways including ‘cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction’ and ‘cell cycle’. The optimal combination of the 12 genes, including CAMK1, HPCAL4 and EFNA5, was found to be useful in predicting the prognosis of patients with DLBCL after R-CHOP treatment. Therefore, these genes may be affected by R-CHOP in DLBCL.

Keywords: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone, differentially expressed genes, prognosis risk model

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a B-cell malignancy. B-cells are a type of white blood cell responsible for producing antibodies. DLBCL is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma among adults, accounting for 25–40% of new cases annually worldwide (1). CD20, a cell-surface protein that is expressed almost exclusively on mature B-cells, is expressed in >90% of DLBCL cases (2). The conventional chemotherapy regimen for DLBCL has been dominated by cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP) since the 1970s. Patients with advanced stage DLBCL have a remission rate of 45–55% and a cure rate of 30–35% with standard CHOP chemotherapy (3). However, it is known that drug resistance is a major obstacle to the success of cancer chemotherapy (4). For DLBCL, 60–70% of patients relapse or develop resistance to CHOP chemotherapy, with a 5-year overall survival rate of 40–50% (5).

Rituximab is a chimeric IgG1 monoclonal antibody targeting CD20. The CD20-binding region of rituximab was derived from a mouse monoclonal antibody through genetic engineering (4,6). It has been reported that rituximab is effective for the treatment of refractory or relapsed lymphomas, and that it also has activity in refractory or relapsed DLBCL (7,8). Since the late 1990s, adding rituximab to conventional CHOP (R-CHOP) for DLBCL treatment has significantly improved the survival rate across all risk groups (6,9). In 2003, R-CHOP was proposed as a first-line standard therapy for DLBCL in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline (10,11). DLBCL is curable in the majority of patients treated with R-CHOP (12), nevertheless, the therapeutic mechanism of R-CHOP has not been elucidated.

In the present study, the genes associated with R-CHOP therapy were selected by comparing expression in primary DLBCL with DLBCL after the treatment with R-CHOP. Additionally, a prognosis prediction model for patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP was constructed based on prognosis-related genes. The present study comprehensively screened for genes associated with R-CHOP therapy in DLBCL, and evaluated the relationship between gene expression and prognosis.

Materials and methods

Data screening and normalization

Expression profiles were retrieved from the National Center of Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) database with ‘diffuse large B-cell lymphoma’, ‘Homo sapiens’ and ‘R-CHOP’ as the key words. The selection criteria for the dataset were as follows: i) Data are gene expression profiles; ii) data from solid tumors at lymph nodes samples from patients with DLBCL (not blood or cell lines); iii) datasets contained DLBCL samples that did not receive and received R-CHOP treatment; and iv) data also had clinical prognostic information.

In total, two datasets (GSE32918 and GSE57611) (13,14) were included in the present study. The GSE32918 dataset [including 82 germinal center B-cell like (GCB), 53 activated B-cell (ABC) and 37 Type III DLBCL] was derived from the GPL14951 Illumina HumanHT-12 WG-DASL V4.0 R2 expression beadchip platform (Illumina, Inc.). In the GSE32918 dataset there are 249 samples from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded biopsies (including 53 ABC, 82 GCB and 37 type III), including 62 DLBCL samples from 32 patients not treated with R-CHOP (palliative care or local radiotherapy) and 187 DLBCL samples from 140 patients treated with R-CHOP. Prognostic information was available for 167 patients. This dataset was used as the training dataset. The GSE57611 dataset, derived from the GPL96 [HG-U133A] Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array (Affymetrix; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), included 148 DLBCL samples (including 79 GCB, 49 ABC and 20 unclassified DLBCLs), among which 30 samples had prognostic information. This dataset was used for validation.

For the GSE32918 dataset that was sequenced on the Illumina platform, the R package limma (version 3.34.0; http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html) (15) was used to transform the skewness distribution of the data to an approximately normal distribution. The data were then normalized using the median normalization method (16). Additionally, for the GSE57611 dataset sequenced using the Affymetrix platform, the R package oligo (version 1.42.0; bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/oligo.html) (17) was used for format conversion, filling missing data (median method) (18), background correction and data normalization (quantile method) (19).

Selection of differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

Limma version 3.34.0 (15) in R 3.4.1 was used to calculate the false discovery rate (FDR) and fold change (FC) value of genes between the primary DLBCL sample and R-CHOP treated DLBCL samples in the training dataset. The genes with an FDR<0.05 and |logFC|>0.5 were considered as DEGs. On the basis of the expression level of the DEGs, Euclidean distance (20) based bilateral hierarchical clustering (21) was performed using pheatmap (version 1.0.8; http://cran.r-r-project.org/package=pheatmap) (22) in R 3.4.1 and the results were visualized using a heatmap.

Construction and validation of the prognostic risk prediction model

Selection of the optimum combination of prognostic genes

The DEGs significantly associated with prognosis in the training set were further selected using the univariate Cox regression analysis in Survival (version 2.4; cran.r-project.org/web/packages/survival/index.html) (23) in R 3.4.1. A log-rank P<0.05 was used as the threshold. The prognosis-associated DEGs were used for Gene Ontology (GO) function and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (version 6.8; david.ncifcrf.gov/) (24). Subsequently, the optimum combination of prognostic genes were selected according to the hazard parameter ‘λ’ that was calculated 1,000 times using a cross-validation likelihood algorithm based on the Cox proportional hazards (Cox-PH) model (25) of L1-penalized regularization regression algorithm in the Penalized package version 0.9–51 (26) in R 3.4.1.

Establishment and verification of the risk prediction model

Based on the aforementioned DEGs combination and Cox-PH regression coefficients, a risk score system for each sample was established using gene expression values weighted by regression coefficients. The risk score of each sample was calculated as follows: Risk score = βgene 1 × expressiongene 1 + βgene 2 × expressiongene 2+… +βgene n × expressiongene n, where β indicates the Cox-PH regression coefficient.

The samples in the training set were divided into high risk score and low risk score groups according to the median risk score. The correlation between the risk prediction model and prognosis was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier survival curves in Survival version 2.41-1 in R 3.4.1. The correlation was verified in the validation dataset (GSE57611).

Function analysis of DEGs between high and low risk score groups

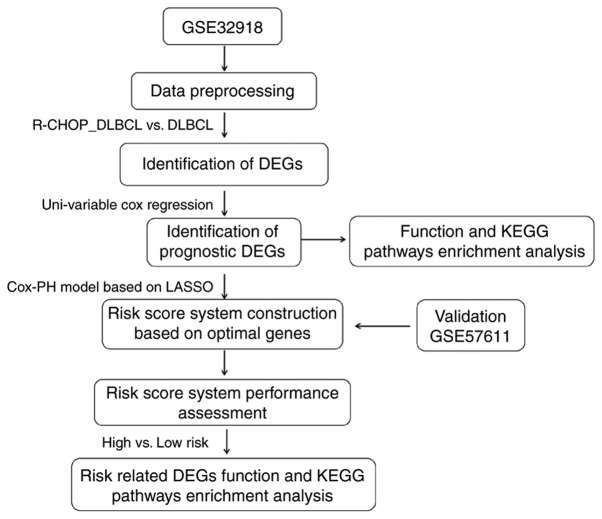

The DEGs between high and low risk score groups were selected using limma version 3.34.0 (15) with thresholds of FDR<0.05 and |log2FC|>0. DEGs were considered to be significantly correlated with risk grouping, and were then subjected to GO and KEGG enrichment analyses, if the threshold of P<0.05. The analysis process is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Analysis process. The GSE32918 dataset was used for the identification of DEGs. R-CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone immunochemotherapy; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; Cox-PH, Cox proportional hazards model.

Results

Data preprocessing and DEG screening

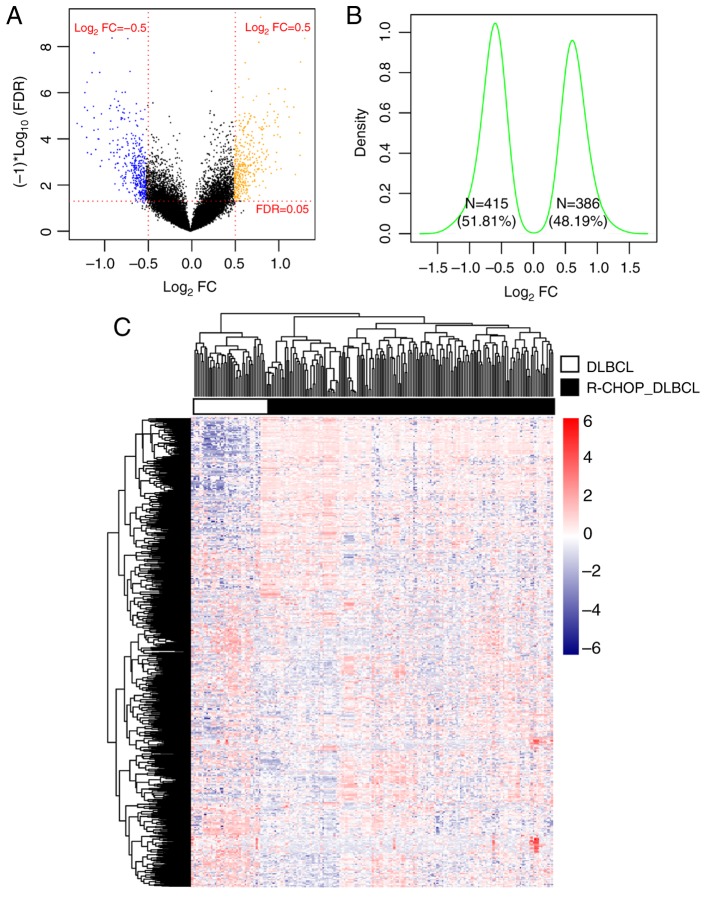

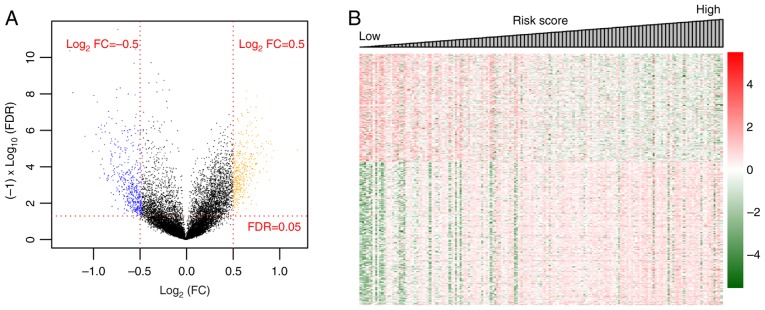

After normalization, the DEGs between R-CHOP-treated and primary DLBCL samples were screened. In total, 801 DEGs were identified, including 386 that were upregulated and 415 that were downregulated (Fig. 2A). The Log2 Kernel density curve based on the expression of the DEGs is shown in Fig. 2B. As shown in Fig. 2B, 51.81% (415/801) of DEGs were significantly downregulated and 48.19% (386/801) of DEGs were significantly upregulated in R-CHOP treated DLBCL samples. The bidirectional hierarchical clustering heatmap based on the expression levels of the DEGs is shown in Fig. 2C. The DEGs in the different samples separated clearly, as represented by the distinct colors in the heatmap.

Figure 2.

Results of screening for DEG. (A) Volcano plot. Orange and blue dots indicate significantly upregulated and downregulated DEGs, respectively. The red dotted horizontal line indicates an FDR<0.05 and the two red dotted vertical lines indicate |logFC|>0.5. (B) Log2 Kernel density curve based on DEGs. (C) Bidirectional hierarchical clustering heatmap based on the expression level of the DEGs. The heatmap colors indicate the expression level; blue indicates low expression while red indicates high expression. DEGs, differentially expressed genes; FDR, false discovery rate; FC, fold change; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; R-CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone immunochemotherapy.

Construction and validation of the prognostic risk prediction model

Selection of the optimal combination of prognostic genes

Based on the identified DEGs and the prognostic information in GSE32918, a total of 116 genes that were significantly correlated with prognosis were selected using univariate Cox regression analysis. Functional analysis of the 116 genes identified 18 significant GO terms, including 11 biological processes (BP), four molecular functions (MF) and three cellular components (CC), and eight KEGG pathways (Table I). The results of this analysis showed that the DEGs identified were significantly associated with the cell cycle and transcription regulation associated biological processes, as well as significantly involved in ‘hsa04060:cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction’ and ‘hsa04014:Ras signaling pathway’.

Table I.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment results for the differentially expressed genes that were significantly correlated with prognosis.

| A, Biological process | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Term | Count | P-value | |

| GO:0007411~axon guidance | 6 | 0.003641 | |

| GO:0007229~integrin-mediated signaling pathway | 5 | 0.003814 | |

| GO:0045892~negative regulation of transcription, DNA-templated | 10 | 0.004883 | |

| GO:0045893~positive regulation of transcription, DNA-templated | 10 | 0.005975 | |

| GO:0016055~Wnt signaling pathway | 6 | 0.007186 | |

| GO:0007165~signal transduction | 16 | 0.00733 | |

| GO:0051726~regulation of cell cycle | 5 | 0.008414 | |

| GO:0030036~actin cytoskeleton organization | 5 | 0.009895 | |

| GO:0043547~positive regulation of GTPase activity | 9 | 0.029303 | |

| GO:0006355~regulation of transcription, DNA-templated | 17 | 0.030824 | |

| GO:0042127~regulation of cell proliferation | 5 | 0.031547 | |

| B, Cellular component | |||

| Term | Count | P-value | |

| GO:0016020~membrane | 25 | 0.003065 | |

| GO:0005667~transcription factor complex | 6 | 0.00656 | |

| GO:0005886~plasma membrane | 36 | 0.018833 | |

| C, Molecular function | |||

| Term | Count | P-value | |

| GO:0005125~cytokine activity | 5 | 0.025713 | |

| GO:0005515~protein binding | 67 | 0.027873 | |

| GO:0003700~transcription factor activity, sequence-specific DNA binding | 12 | 0.041048 | |

| GO:0044212~transcription regulatory region DNA binding | 5 | 0.04659 | |

| D, KEGG pathway | |||

| Term | Count | P-value | |

| hsa04060:Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 7 | 0.00103 | |

| hsa04014:Ras signaling pathway | 6 | 0.00354 | |

| hsa04015:Rap1 signaling pathway | 5 | 0.008964 | |

| hsa05200:Pathways in cancer | 7 | 0.009679 | |

| hsa04062:Chemokine signaling pathway | 4 | 0.019075 | |

| hsa04151:PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 5 | 0.030569 | |

| hsa04310:Wnt signaling pathway | 3 | 0.030827 | |

| hsa04514:Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) | 3 | 0.032028 | |

GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

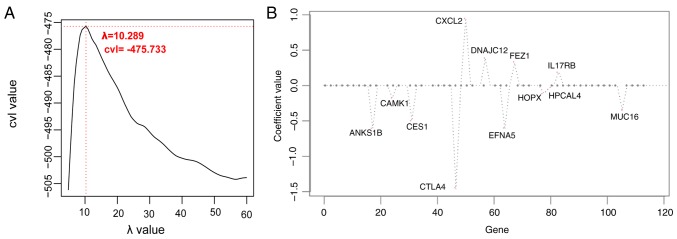

The optimal combination of prognostic genes was determined using the Cox-PH model. When the parameter ‘λ’ was 10.289, the cross-validation likelihood reached the maximum value of −475.733 (Fig. 3A). Under this parameter, the Cox-PH model identified a 12 gene combination (Fig. 3B). The 12 genes are listed in Table II.

Figure 3.

Selection of optimal prognostic genes. (A) Curve of cvl screening for the λ parameter. The optimized parameter λ, indicator of the hazard, was obtained by 1,000 rounds of cross-validated likelihood (cvl) circular calculation. The horizontal and vertical axes represent different values of λ and cvl, respectively. The crossing of the red dotted line represents λ of 10.289 when cvl takes the maximum (−475.733). (B) Coefficient distribution diagram of the optimal combination of prognostic genes based on the Cox proportional hazards model. cvl, cross-validation likelihood; ANKS1B, ankyrin repeat and sterile α motif domain-containing protein 1B; CAMK1, calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase I; CES, carboxylesterase 1; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4; CXCL2, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 2; DNAJC12, DnaJ heat shock protein family member C12; EFNA5, ephrin A5; FEZ1, fasciculation and elongation protein ζ1; HOPX, HOP homeobox; HPCAL4, hippocalcin like 4; IL17RB, interleukin 17 receptor B; MUC16, mucin 16, cell surface associated.

Table II.

Optimal genes list based on Cox proportional hazards model of L1-penalized regularization regression algorithm.

| Gene | Coef | Hazard ratio | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANKS1B | −0.605 | 0.767 (0.658–0.895) | 6.568×10−4 |

| CAMK1 | −0.179 | 0.837 (0.729–0.959) | 1.045×10−2 |

| CES1 | −0.496 | 0.846 (0.751–0.953) | 5.423×10−3 |

| CTLA4 | −1.468 | 0.716 (0.627–0.817) | 5.008×10−7 |

| CXCL2 | 0.948 | 1.559 (1.219–1.994) | 5.637×10−4 |

| DNAJC12 | 0.379 | 1.480 (1.239–1.767) | 1.332×10−5 |

| EFNA5 | −0.619 | 0.811 (0.719–0.915) | 5.862×10−4 |

| FEZ1 | 0.317 | 1.214 (1.059–1.390) | 5.066×10−3 |

| HOPX | −0.114 | 0.859 (0.750–0.984) | 2.703×10−2 |

| HPCAL4 | −0.039 | 0.666 (0.531–0.837) | 4.057×10−4 |

| IL17RB | 0.187 | 1.137 (1.023–1.263) | 1.627×10−2 |

| MUC16 | −0.348 | 0.837 (0.731–0.957) | 8.829×10−3 |

Coef, coefficient; ANKS1B, ankyrin repeat and sterile α motif domain-containing protein 1B; CAMK1, calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase I; CES, carboxylesterase 1; CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4; CXCL2, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 2; DNAJC12, DnaJ heat shock protein family member C12; EFNA5, ephrin A5; FEZ1, fasciculation and elongation protein ζ1; HOPX, HOP homeobox; HPCAL4, hippocalcin like 4; IL17RB, interleukin 17 receptor B; MUC16, mucin 16, cell surface associated.

Establishment and evaluation of the risk prediction model

According to the 12-gene combination, as well as the Cox-PH regression coefficients, the sample risk score prediction model was constructed as follows: Risk score = (−0.605) × expressionANKS1B + (−0.179) × expressionCAMK1 + (−0.496) × expressionCES1 + (−1.468) × expressionCTLA4 + (0.948) × expressionCXCL2 + (0.379) × expressionDNAJC12 × (−0.619) × expressionEFNA5 + (0.317) × expressionFEZ1 + (−0.114) × expressionHOPX + (−0.039) × expressionHPCAL4 + (0.187) × expressionIL17RB + (−0.348) × expressionMUC16.

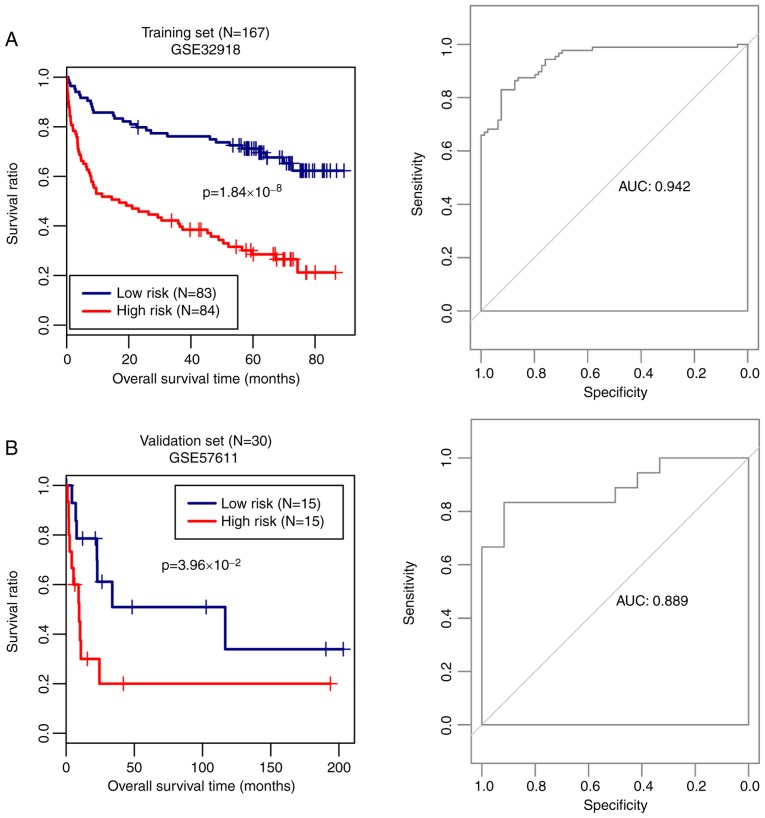

Based on this model, the risk score of each sample in GSE32918 (the training set) was calculated and the samples were divided into high risk score and low risk score groups according to the median risk score. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to evaluate overall survival prognosis in the 167 DLBCL samples in the training set. As shown in Fig. 4A, the patients with a high risk score had significantly shorter survival times (P=1.84х10−8). The prediction model had a high sensitivity, with the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.942. Additionally, the prediction performance of the model was confirmed using the validation set. Patients with high risk scores had shorter survival times (P=3.96х10−2; AUC=0.889; Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Prediction model and overall survival Kaplan-Meier curves. Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves (left) and receiver operating characteristic curves (right) based on the optimal gene combination in (A) training set (GSE32918) and (B) validation set (GSE57611). Blue and red curves represent the low and high risk score groups, respectively. AUC, area under curve.

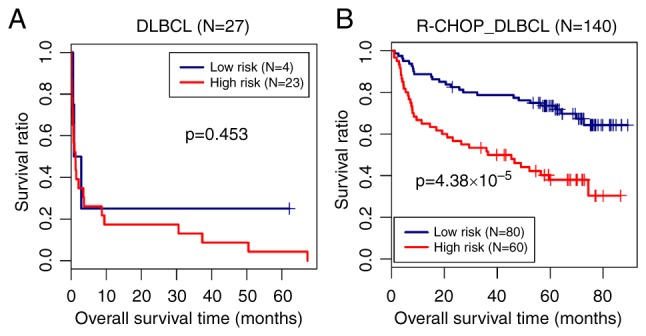

In order to analyze the performance of the prediction model in DLBCL and R-CHOP-treated DLBCL samples, the samples in the training set were divided into DLBCL and R-CHOP-treated DLBCL groups, and the risk score model was analyzed in the two sets of samples. As shown in Fig. 5, the predictive ability of the risk prediction model in the R-CHOP-treated DLBCL group (P=4.38х10−5) was superior to that in the untreated DLBCL group (P=0.453). This indicated that the risk score model had a high prediction power in R-CHOP-treated DLBCLs.

Figure 5.

Prediction model and the overall survival Kaplan-Meier curves. Overall survival Kaplan-Meier curves based on the optimal gene combination in (A) DLBCL and (B) R-CHOP treated DLBCL samples. Blue and red curves represent the low risk score and high risk score groups, respectively. DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; R-CHOP, rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone immunochemotherapy.

Function annotation of risk associated genes

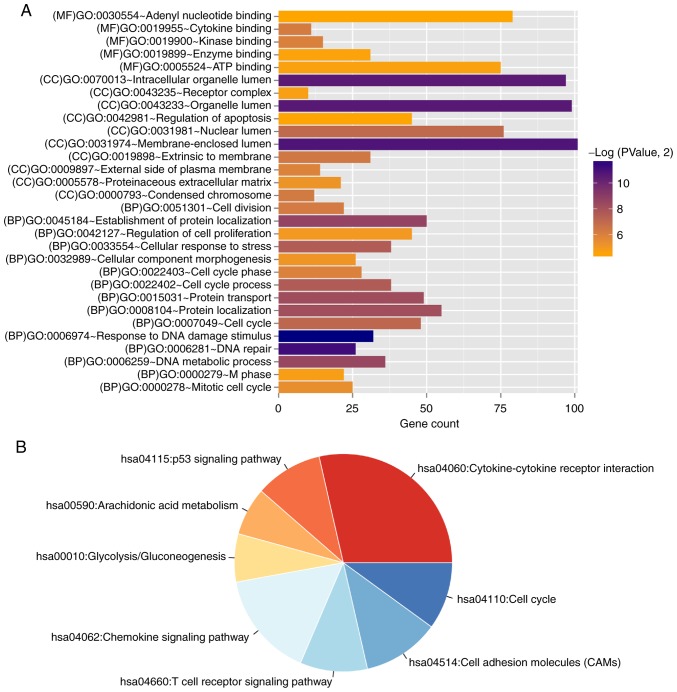

A total of 729 DEGs were identified comparing the high and low risk score samples in the training set, among which 314 DEGs were significantly downregulated and 415 were significantly upregulated in the high risk score group (Fig. 6A). The volcano plot is shown in Fig. 6A and the heatmap based on the expression level changes of the DEGs, with the risk score, is shown in Fig. 6B. These DEGs were used for functional annotation; 30 significant GO terms (16 BP, nine CC and five MF) and nine KEGG pathways were identified (Table III and Fig. 7). The DEGs were significantly enriched in functions associated with ‘response to DNA damage stimulus’, ‘cell cycle’ and the ‘cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction’ pathways.

Figure 6.

DEGs between high and low risk groups. (A) Volcano plot. Orange and blue dots indicate significantly upregulated and downregulated DEGs, respectively. The red dotted horizontal line indicates an FDR<0.05 and the two red dotted vertical lines indicate |logFC|>0.5. (B) Heatmap based on the expression level of DEGs. DEGs, differentially expressed genes; FDR, false discovery rate; FC, fold change.

Table III.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment results for DEGs.

| A, Biological process | ||

|---|---|---|

| Term | Count | P-value |

| GO:0006974~response to DNA damage stimulus | 32 | 2.47×10−04 |

| GO:0006281~DNA repair | 26 | 4.14×10−04 |

| GO:0045184~establishment of protein localization | 50 | 0.002456 |

| GO:0006259~DNA metabolic process | 36 | 0.002753 |

| GO:0015031~protein transport | 49 | 0.003342 |

| GO:0008104~protein localization | 55 | 0.003533 |

| GO:0022402~cell cycle process | 38 | 0.00521 |

| GO:0033554~cellular response to stress | 38 | 0.005394 |

| GO:0007049~cell cycle | 48 | 0.007516 |

| GO:0051301~cell division | 22 | 0.013451 |

| GO:0022403~cell cycle phase | 28 | 0.016532 |

| GO:0000278~mitotic cell cycle | 25 | 0.024163 |

| GO:0032989~cellular component morphogenesis | 26 | 0.029787 |

| GO:0042127~regulation of cell proliferation | 45 | 0.032887 |

| GO:0000279~M phase | 22 | 0.038695 |

| GO:0042981~regulation of apoptosis | 45 | 0.045193 |

| B, Cellular component | ||

| Term | Count | P-value |

| GO:0031974~membrane-enclosed lumen | 101 | 5.31×10−04 |

| GO:0043233~organelle lumen | 99 | 6.35×10−04 |

| GO:0070013~intracellular organelle lumen | 97 | 6.75×10−04 |

| GO:0031981~nuclear lumen | 76 | 0.008073 |

| GO:0019898~extrinsic to membrane | 31 | 0.012421 |

| GO:0000793~condensed chromosome | 12 | 0.012999 |

| GO:0009897~external side of plasma membrane | 14 | 0.017106 |

| GO:0005578~proteinaceous extracellular matrix | 21 | 0.028573 |

| GO:0043235~receptor complex | 10 | 0.039703 |

| C, Molecular function | ||

| Term | Count | P-value |

| GO:0019955~cytokine binding | 11 | 0.014221 |

| GO:0019900~kinase binding | 15 | 0.015941 |

| GO:0005524~ATP binding | 75 | 0.041085 |

| GO:0019899~enzyme binding | 31 | 0.042744 |

| GO:0030554~adenyl nucleotide binding | 79 | 0.046193 |

| D, KEGG pathway | ||

| Term | Count | P-value |

| hsa04060:Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 20 | 0.002507 |

| hsa04115:p53 signaling pathway | 7 | 0.008288 |

| hsa00590:Arachidonic acid metabolism | 5 | 0.024164 |

| hsa00010:Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis | 5 | 0.028166 |

| hsa04062:Chemokine signaling pathway | 11 | 0.032858 |

| hsa04660:T cell receptor signaling pathway | 7 | 0.035535 |

| hsa04514:Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) | 8 | 0.038001 |

| hsa04110:Cell cycle | 7 | 0.04925 |

GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; DEG, differentially expressed gene.

Figure 7.

Gene enrichment analysis. (A) Bar graph of the GO terms significantly associated with the differentially expressed genes. The horizontal axis represents the number of genes and the vertical axis shows the term. The color of the bars indicates the significance level. (B) Pie chart of KEGG pathways identified. Each segment represents a different KEGG pathway. The colors represent significant P-values (P<0.05) for each section; red low P-value, blue high P-value. KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; MF, molecular function; GO, Gene Ontology; CC, cellular component; BP, biological process.

Discussion

In the present study, 801 DEGs were identified between R-CHOP-treated DLBCL and primary DLBCL samples. From the 801 DEGs, 116 prognosis-associated genes were identified; these genes were significantly enriched in 18 GO terms and eight pathways. Using the Cox-PH model, an optimal combination of 12 genes was selected, and the sample risk score prediction model was constructed and validated. The samples in the training set were divided into high and low risk score groups based on the risk score. The DEGs between high and low risk score groups were significantly enriched in functions associated with ‘response to DNA damage stimulus’, ‘cell cycle’ and the ‘cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction’ pathway.

It has been reported that the signal transduction system, comprising growth factors, cytoplasmic secondary messengers and transmembrane receptor proteins, optimizes the growth and metastasis of tumor cells in malignancies, and is therefore considered as a target for cancer therapy (27). Functional enrichment analysis showed that calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase I (CAMK1), a component of the calmodulin-dependent protein kinase cascade, and hippocalcin like 4 (HPCAL4) were enriched in functions associated with ‘signal transduction’ (GO:0007165). The roles of CAMK1 and HPCAL4 in cancer have not been fully analyzed to the best of our knowledge, but it is speculated that CAMK1 and HPCAL4 may be targets of R-CHOP in DLBCL given their association with signal transduction.

Among the 12 genes, five were found to be associated with ‘protein binding’ (GO:0005515), including CAMK1, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4), fasciculation and elongation protein ζ1 (FEZ1), HOP homeobox (HOPX), and mucin 16, cell surface associated (MUC16). CTLA4 is a coinhibitory receptor that regulates T-cell activation during the initiation and maintenance of adaptive immune responses. The blocking of CTLA4 promotes antitumor T-cell immunity (28). In addition, rituximab could enhance the production of CTLA4 by regulatory T-cells (29) and B-cells (30). FEZ1 encodes a 67 kDa leucine-zipper protein with a region similar to cAMP-dependent activated protein (31), which has been found to be mutated in solid tumors (32). In FEZ1 null cancer cells, FEZ1 introduction has been reported to reduce cell growth, while FEZ1 inhibition stimulates cell growth, suggesting a role for FEZ1 in human cancer (33). HOPX belongs to the homeobox gene family and is ubiquitously expressed in normal tissues (34). It has been reported that enforced HOPX expression inhibits tumor progression and that HOPX knockdown restores tumor aggressiveness (35). MUC16 is a member of the mucin family that is reported to be involved in tumorigenicity and therapeutic resistance in pancreatic cancer (36). Moreover, MUC16 is overexpressed in multiple types of cancer and has an important role in acquired resistance to therapy (37). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no previous evidence showing the association of these DEGs with CD20 or DLBCL. Given the roles of the five genes in cancer, it is speculated that R-CHOP may target CAMK1, CTLA4, FEZ1, HOPX and MUC16. The negative effect of CTLA4 on risk scores in DLBCL samples showed that the increased expression of CTLA4 contributed to the efficiency of rituximab therapy. Similar hypotheses could be made for the CAMK1, MUC16 and HOPX genes.

The other two DEGs, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CXCL2) and ephrin A5 (EFNA5) were found to be involved in several signaling pathways, including the ‘Ras signaling pathway’, ‘chemokine signaling pathway’ and ‘PI3K-Akt signaling pathway’. These signaling mechanisms are fundamental pathways in normal and tumor cells, even if tumor cells may be more reliant on these pathways (38). The Ras signaling pathway is commonly activated in tumors (38). Rational therapies targeting the Ras signaling pathways inhibit tumor survival, growth and spread (39). The PI3K-Akt signaling pathway regulates multiple tumorigenesis-associated cellular processes, including cell proliferation, growth and motility (40). Mutations or altered expression levels of components of the PI3K-Akt pathway are implicated in human cancer (41). Therefore, several drugs, alone and in combination, including rituximab, targeting the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway are in clinical trials, in both hematologic malignancies and solid tumors (42,43). It has been previously reported that rituximab-induced apoptosis in the B-cell lymphoma cell line SD07 is mediated by PI3K-Akt dephosphorylation or suppression (43). The normal development of cells depends on chemokines and their receptors, and tumor progression also requires stimulation by chemokines (44). CXCL2, which is part of the CXC chemokine family, promotes inflammation and supports tumor growth (45). Taken together, it is speculated that CXCL2 and EFNA5 may be targeted by R-CHOP via these signaling pathways. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence showing the association of CXCL2 alteration with DLBCL, R-CHOP therapy or rituximab.

Interleukin 17 receptor B (IL17RB) was enriched in the ‘cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction’ pathway (hsa04060). IL17RB, a proinflammatory cytokine, is the receptor of IL17B (46). Cytokines play important roles in the localization of normal or malignant B-cells in tissues (47). IL17RB is expressed in endocrine tissues and is expressed in normal mammary epithelial cells at negligible levels (48). However, IL17RB was previously found to be highly expressed in malignant mammary epithelial cells (49). The overexpression of IL17B has been reported to be associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer (50). Previous studies have reported that certain cytokines, including interleukin-4 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) upregulate the expression of the CD20 antigen, increasing the efficacy of rituximab (51,52). IL-17 and TNF-α are inflammatory cytokines that are co-expressed by T helper 17 cells in a number of tumors (53). The findings indicate that IL17RB has a role in R-CHOP-mediated therapy for DLBCL.

In addition to the aforementioned genes, the remaining three DEGs were not enriched in GO terms or pathways. Ankyrin repeat and sterile α motif domain-containing protein 1B (ANKS1B) is involved in tyrosine kinase signal transduction (54), and is primarily expressed in the brain and testis (55). ANKS1B is involved in apoptosis, and thus, has potential functions in cancer development (56). A previous study demonstrated that the expression of ANKS1B gene is associated with the development of smoking-related clear cell renal cell carcinoma (57). Carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) is a member of the carboxylesterase family and is important in phase I metabolism (58). Carboxylesterases mediate the metabolism of drug compounds with thioester, ester and amide linkages, and the detoxification of xenobiotics (59). Carboxylesterases are found to hydrolyze two anticancer agents, capecitabine and irinotecan (60). DnaJ heat shock protein family member C12 (DNAJC12) encodes a member of a subclass of the heat shock protein 40 kDa family that is involved in a number of important biological functions (61,62). High expression of DNAJC12 functions as a negative predictive factor for the response to neoadjuvant concurrent chemotherapy in rectal cancer (63). Little information is available regarding these genes, and their role in DLBCL and other diseases. The combination of these genes in the risk predication model suggests their important roles in DLBCL therapy. It is speculated that ANKS1B, CES1 and DNAJC12 may serve as important target genes in R-CHOP therapy in DLBCL.

In conclusion, the optimal combination of 12 genes to predict prognosis risk, including CAMK1, HPCAL4, CXCL2 and EFNA5, was selected based on the differential expression of these genes between R-CHOP-treated DLBCL and primary DLBCL groups. These genes were utilized in the construction of the prognosis prediction model in DLBCL after R-CHOP treatment. These genes may also serve as target genes of R-CHOP in DLBCL. To the best of our knowledge, most of these DEGs have not been reported to be associated with DLBCL and CD20 or rituximab-mediated therapy, highlighting the novel insights the present study provides into the pathogenesis and treatment of DLBCL.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81600161).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

RL and ZC were responsible for the conception and design of the research and the manuscript drafting. YG performed the revision for important intellectual content. GZ, YG, SW, QH and BC were responsible for the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. QH and BC were involved in the manuscript revision. All authors approved the final revision.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sabattini E, Bacci F, Sagramoso C, Pileri SA. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues in 2008: An overview. Pathologica. 2010;102:83–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dreyling M, Thieblemont C, Gallamini A, Arcaini L, Campo E, Hermine O, Kluin-Nelemans JC, Ladetto M, Le Gouill S, Iannitto E, et al. ESMO Consensus conferences: Guidelines on malignant lymphoma. part 2: Marginal zone lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:857–877. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganjoo KN, An CS, Robertson MJ, Gordon LI, Sen JA, Weisenbach J, Li S, Weller EA, Orazi A, Horning SJ. Rituximab, bevacizumab and CHOP (RA-CHOP) in untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Safety, biomarker and pharmacokinetic analysis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:998–1005. doi: 10.1080/10428190600563821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patil Y, Sadhukha T, Ma L, Panyam J. Nanoparticle-mediated simultaneous and targeted delivery of paclitaxel and tariquidar overcomes tumor drug resistance. J Control Release. 2009;136:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cultrera JL, Dalia SM. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Current strategies and future directions. Cancer Control. 2012;19:204–213. doi: 10.1177/107327481201900305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, Morel P, Van Den Neste E, Salles G, Gaulard P, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maloney DG, Grillo-López AJ, White CA, Bodkin D, Schilder RJ, Neidhart JA, Janakiraman N, Foon KA, Liles TM, Dallaire BK, et al. IDEC-C2B8 (Rituximab) anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in patients with relapsed low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Blood. 1997;90:2188–2195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mclaughlin P, Grillo-López AJ, Link BK, Levy R, Czuczman MS, Williams ME, Heyman MR, Bence-Bruckler I, White CA, Cabanillas F, et al. Rituximab chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for relapsed indolent lymphoma: Half of patients respond to a four-dose treatment program. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2825–2833. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, Gascoyne RD, Cassileth PA, Cohn JB, Dakhil SR, Woda B, Fisher RI, Peterson BA, Horning SJ. Rituximab-CHOP versus CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3121–3127. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Comprehensive Cancer Network, corp-author. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pettengell R, Bosly A, Szucs TD, Jackisch C, Leonard R, Paridaens R, Constenla M, Schwenkglenks M, Impact of Neutropenia in Chemotherapy-European Study Group (INC-EU) Multivariate analysis of febrile neutropenia occurrence in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Data from the INC-EU Prospective Observational European Neutropenia Study. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:677–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07514.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sehn LH, Scott DW, Chhanabhai M, Berry B, Ruskova A, Berkahn L, Connors JM, Gascoyne RD. Impact of concordant and discordant bone marrow involvement on outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1452–1457. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrans SL, Crouch S, Care MA, Worrillow L, Smith A, Patmore R, Westhead DR, Tooze R, Roman E, Jack AS. Whole genome expression profiling based on paraffin embedded tissue can be used to classify diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and predict clinical outcome. Br J Haematol. 2012;159:441–453. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scholtysik R, Kreuz M, Hummel M, Rosolowski M, Szczepanowski M, Klapper W, Loeffler M, Trümper L, Siebert R, Küppers R, Molecular Mechanisms in Malignant Lymphomas Network Project of the Deutsche Krebshilfe Characterization of genomic imbalances in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by detailed SNP-chip analysis. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:1033–1042. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li S, Sun YN, Zhou YT, Zhang CL, Lu F, Liu J, Shang XM. Screening and identification of microRNA involved in unstable angina using gene-chip analysis. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:2716–2722. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parrish RS, Spencer HJ., III Effect of normalization on significance testing for oligonucleotide microarrays. J Biopharm Stat. 2004;14:575–589. doi: 10.1081/BIP-200025650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaminskyi R, Kunanets N, Pasichnyk V, Rzheuskyi A, Khudyi A. Recovery gaps in experimental data. COLINS. 2018:108–118. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Åstrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szekely GJ, Rizzo ML. Hierarchical clustering via joint between-within distances: Extending Ward's minimum variance method. J Classification. 2005;22:151–183. doi: 10.1007/s00357-005-0012-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Press W, Teukolsky S, Vetterling W, Flannery B. Section 16.4. Hierarchical clustering by phylogenetic trees. Numerical recipes: The art of scientific computing. 2007:868–881. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L, Cao C, Ma Q, Zeng Q, Wang H, Cheng Z, Zhu G, Qi J, Ma H, Nian H, Wang Y. RNA-seq analyses of multiple meristems of soybean: Novel and alternative transcripts, evolutionary and functional implications. BMC Plant Biol. 2014;14:169. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang P, Wang Y, Hang B, Zou X, Mao JH. A novel gene expression-based prognostic scoring system to predict survival in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:55343–55351. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tibshirani R. THE lasso method for variable selection in the COX model. Stat Med. 1997;16:385–395. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19970228)16:4<385::AID-SIM380>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goeman JJ. L1 penalized estimation in the Cox proportional hazards model. Biom J. 2010;52:70–84. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200900028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adjei AA, Hidalgo M. Intracellular signal transduction pathway proteins as targets for cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5386–5403. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.23.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang D, Zhang B, Gao H, Ding G, Wu Q, Zhang J, Liao L, Chen H. Clinical research of genetically modified dendritic cells in combination with cytokine-induced killer cell treatment in advanced renal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:251. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinha A, Bagga A. Rituximab therapy in nephrotic syndrome: Implications for patients' management. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:154–169. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sfikakis P, Souliotis V, Fragiadaki K, Moutsopoulos H, Boletis J, Theofilopoulos A. Increased expression of the Foxp3 functional marker of regulatory t cells following b cell depletion with rituximab in patients with lupus nephritis. Clin Immunol. 2007;123:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishii H, Baffa R, Numata SI, Murakumo Y, Rattan S, Inoue H, Mori M, Fidanza V, Alder H, Croce CM. The FEZ1 gene at chromosome 8p22 encodes a leucine-zipper protein, and its expression is altered in multiple human tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3928–3933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vecchione A, Ishii H, Shiao YH, Trapasso F, Rugge M, Tamburrino JF, Murakumo Y, Alder H, Croce CM, Baffa R. Fez1/lzts1 alterations in gastric carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1546–1552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cabeza-Arvelaiz Y, Sepulveda JL, Lebovitz RM, Thompson TC, Chinault AC. Functional identification of LZTS1 as a candidate prostate tumor suppressor gene on human chromosome 8p22. Oncogene. 2001;20:4169–4179. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kikuchi M, Katoh H, Waraya M, Tanaka Y, Ishii S, Tanaka T, Nishizawa N, Yokoi K, Minatani N, Ema A, et al. Epigenetic silencing of HOPX contributes to cancer aggressiveness in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017;384:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheung WK, Zhao M, Liu Z, Stevens LE, Cao PD, Fang JE, Westbrook TF, Nguyen DX. Control of alveolar differentiation by the lineage transcription factors GATA6 and HOPX inhibits lung adenocarcinoma metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:725–738. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shukla SK, Gunda V, Abrego J, Haridas D, Mishra A, Souchek J, Chaika NV, Yu F, Sasson AR, Lazenby AJ, et al. MUC16-mediated activation of mTOR and c-MYC reprograms pancreatic cancer metabolism. Oncotarget. 2015;6:19118–19131. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aithal A, Rauth S, Kshirsagar P, Shah A, Lakshmanan I, Junker WM, Jain M, Ponnusamy MP, Batra SK. MUC16 as a novel target for cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2018;22:675–686. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2018.1498845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slack C, Alic N, Foley A, Cabecinha M, Hoddinott MP, Partridge L. The Ras-Erk-ETS-signaling pathway is a drug target for longevity. Cell. 2015;162:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang Y, Zhang J, Hou L, Wang G, Liu H, Zhang R, Chen X, Zhu J. LncRNA AK023391 promotes tumorigenesis and invasion of gastric cancer through activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:194. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0666-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martini M, De Santis M, Braccini L, Gulluni F, Hirsch E. PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and cancer: An updated review. Ann Med. 2014;46:372–383. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.912836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayer IA, Arteaga CL. The PI3K/AKT pathway as a target for cancer treatment. Annu Rev Med. 2015;67:11–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-062913-051343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakamaki T, Baba Y, Abe M, Murai S, Watanuki M, Kabasawa N, Yanagisawa K, Hattori N, Kawaguchi Y, Arai N, et al. Rituximab-induced CD20-mediated signals and suppression of PI3K-AKT pathway cooperates to inhibit B-cell lymphoma growth by down-regulation of Myc. Blood. 2016;128:5312. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagasawa T, Hirota S, Tachibana K, Takakura N, Nishikawa S, Kitamura Y, Yoshida N, Kikutani H, Kishimoto T. Defects of B-cell lymphopoiesis and bone-marrow myelopoiesis in mice lacking the CXC chemokine PBSF/SDF-1. Nature. 1996;382:635–638. doi: 10.1038/382635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu Q, Peng J, Qin H, Yu W. The role of CXC chemokines and their receptors in the progression and treatment of tumors. J Mol Histol. 2012;43:699–713. doi: 10.1007/s10735-012-9435-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hunninghake GM, Chu JH, Sharma SS, Cho MH, Himes BE, Rogers AJ, Murphy A, Carey VJ, Raby BA. The CD4+ T-cell transcriptome and serum IgE in asthma: IL17RB and the role of sex. BMC Pulm Med. 2011;11:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-11-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Husson H, Carideo EG, Cardoso AA, Lugli SM, Neuberg D, Munoz O, de Leval L, Schultze J, Freedman AS. MCP-1 modulates chemotaxis by follicular lymphoma cells. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:554–562. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alinejad V, Dolati S, Motallebnezhad M, Yousefi M. The role of IL17B-IL17RB signaling pathway in breast cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;88:795–803. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.01.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharma S, Rajaram S, Sharma T, Goel N, Agarwal S, Banerjee BD. Role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations in epithelial ovarian cancer in Indian population: A pilot study. Int J Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;5:1–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Furuta S, Jeng YM, Zhou L, Huang L, Kuhn I, Bissell MJ, Lee WH. IL-25 causes apoptosis of IL-25R-expressing breast cancer cells without toxicity to nonmalignant cells. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:78ra31. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pievani A, Belussi C, Klein C, Rambaldi A, Golay J, Introna M. Enhanced killing of human B-cell lymphoma targets by combined use of cytokine-induced killer cell (CIK) cultures and anti-CD20 antibodies. Blood. 2011;117:510–518. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-290858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Venugopal P, Sivaraman S, Huang X, Nayini J, Gregory S, Preisler H. Effects of cytokines on CD20 antigen expression on tumor cells from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2000;24:411–415. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(99)00206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X, Yang L, Huang F, Zhang Q, Liu S, Ma L, You Z. Inflammatory cytokines IL-17 and TNF-α up-regulate PD-L1 expression in human prostate and colon cancer cells. Immunol Lett. 2017;184:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herberich SE, Klose R, Moll I, Yang WJ, Wüstehube-Lausch J, Fischer A. ANKS1B interacts with the cerebral cavernous malformation protein-1 and controls endothelial permeability but not sprouting angiogenesis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fu X, McGrath S, Pasillas M, Nakazawa S, Kamps MP. EB-1, a tyrosine kinase signal transduction gene, is transcriptionally activated in the t (1;19) subset of pre-B ALL, which express oncoprotein E2a-Pbx1. Oncogene. 1999;18:4920–4929. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Evan GI, Vousden KH. Proliferation, cell cycle and apoptosis in cancer. Nature. 2001;411:342–348. doi: 10.1038/35077213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eckel-Passow JE, Serie DJ, Bot BM, Joseph RW, Cheville JC, Parker AS. ANKS1B is a smoking-related molecular alteration in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. BMC Urol. 2014;14:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-14-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Satoh T, Hosokawa M. Structure, function and regulation of carboxylesterases. Chem Biol Interact. 2006;162:195–211. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Redinbo MR, Potter PM. Mammalian carboxylesterases: From drug targets to protein therapeutics. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:313–325. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03383-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pratt SE, Durland-Busbice S, Shepard RL, Heinz-Taheny K, Iversen PW, Dantzig AH. Human carboxylesterase-2 hydrolyzes the prodrug of gemcitabine (LY2334737) and confers prodrug sensitivity to cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1159–1168. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anikster Y, Haack TB, Vilboux T, Pode-Shakked B, Thöny B, Shen N, Guarani V, Meissner T, Mayatepek E, Trefz FK, et al. Biallelic mutations in DNAJC12 cause hyperphenylalaninemia, dystonia, and intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jung-KC K, Himmelreich N, Prestegård KS, Shi TS, Scherer T, Ying M, Jorge-Finnigan A, Thöny B, Blau N, Martinez A. Phenylalanine hydroxylase variants interact with the co-chaperone DNAJC12. Hum Mutat. 2019;40:483–494. doi: 10.1002/humu.23712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.He HL, Lee YE, Chen HP, Hsing CH, Chang IW, Shiue YL, Lee SW, Hsu CT, Lin LC, Wu TF, Li CF. Overexpression of DNAJC12 predicts poor response to neoadjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with rectal cancer. Exp Mol Pathol. 2015;98:338–345. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2015.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.