Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study is to report the benefits and burdens of palliative research participation on children, siblings, parents, clinicians, and researchers.

Background: Pediatric palliative care requires research to mature the science and improve interventions. A tension exists between the desire to enhance palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families and the need to protect these potentially vulnerable populations from untoward burdens.

Methods: Systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines with prepared protocol registered as PROSPERO #CRD42018087304. MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Scopus, and The Cochrane Library were searched (2000–2017). English-language studies depicting the benefits or burdens of palliative care or end-of-life research participation on either pediatric patients and/or their family members, clinicians, or study teams were eligible for inclusion. Study quality was appraised using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT).

Results: Twenty-four studies met final inclusion criteria. The benefit or burden of palliative care research participation was reported for the child in 6 papers; siblings in 2; parents in 19; clinicians in 3; and researchers in 5 papers. Benefits were more heavily emphasized by patients and family members, whereas burdens were more prominently emphasized by researchers and clinicians. No paper utilized a validated benefit/burden scale.

Discussion: The lack of published exploration into the benefits and burdens of those asked to take part in pediatric palliative care research and those conducting the research is striking. There is a need for implementation of a validated benefit/burden instrument or interview measure as part of pediatric palliative and end-of-life research design and reporting.

Keywords: benefits and burdens, palliative care research, pediatric palliative care

Introduction

Research is needed to support design of interventions in pediatric, palliative, and end-of-life care and to measure the impact of interventions once implemented.1 The advancement of pediatric palliative care as a new and maturing field requires research to advance the science of not only clinical care but caring with measured excellence as well. The general public, institutional review boards (IRBs), ethics and oversight committees, grant reviewers, and even some bedside clinicians are sometimes fearful of involving children and their family members in palliative care and end-of-life research.2–5 This hesitancy rests on a concern for potential or anticipated burden to research subjects.6–8

Adult studies have shown overestimation of palliative care research burden and underestimation of research benefit at end of life.9 Recent assessment of the benefit and burden of psychosocial research in medically ill youth using validated measures and a Burden and Benefit Scale9 revealed that pediatric patients (83%) and caregivers (93%) did not find participation burdensome; rather, patients (85%) and caregivers (95%) found benefit in participation.10 A clearer understanding of the actual benefit and experienced burden to children, family members, clinicians, and even study team members participating in pediatric palliative care research is needed.

A tension exists between improving care for children and family members receiving palliative care services and the need to protect these vulnerable, potential research participants. Rather than extrapolate adult palliative care research findings into pediatric settings, engaging children and their family members who are receiving palliative care or end-of-life care in research could lead to discovering knowledge unique to pediatrics. Fear of including children and their families in palliative care research could prevent this special population from experiencing the potential benefit of research participation. Including children and their families in pediatric palliative care research could foster an understanding of self-identified care needs or system improvements and, thus, could be a way to promote health equity.

To automatically exclude children receiving palliative or end-of-life care and their family members from research participation due to fear of burden could effectively silence these knowledgable informants. Including children and even bereaved family members in well-designed research will inform ways of giving care more thoughtfully and effectively.11,12 Therefore, the objective of this systematic review was to examine the state of the science regarding the burden and benefit of participation in pediatric palliative care research as reported by children or adolescents, their family members, their clinicians, and their research teams.

Methods

Inclusion criteria, as well as methods of data extraction and analysis, were specified in advance. The literature search process was guided by an academic research librarian (C.M.S.) and outlined in the PROSPERO protocol (Registry #CRD42018087304). Literature database searches were limited to English-language articles published from 2000 through 2017. The decision to start the search in year 2000 was based on the feasibility of capturing data in a rapidly growing field. Pediatric-specific palliative care publications exponentially increased in 2000 as compared with even the late 1990s. The searches were conducted in three phases in November 2017. During Phase 1, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO (all through EBSCOhost); EMBASE and Scopus (through Elsevier interfaces); and The Cochrane Library (through the Wiley interface) were searched. The search strategies were composed of keywords and subject headings for the four search concepts: (1) infants, children, and adolescents; (2) advance care planning, palliative/hospice/end-of-life care, and bereavement care; (3) risk/benefit terms; and (4) terms indicative of research participation. The complete search strategies are available in Supplementary Appendix SA1. C.A.S. and M.S.W. performed an initial, title/abstract review of Phase 1 results solely to identify articles that could be used as a basis for Phase 3, “cited-” or “citing-article” searches.

This review identified 54 articles with titles or abstracts that mentioned the topic of interest. During Phase 2, the interdisciplinary study team identified 19 articles that focused some attention on the topic of interest. These articles were previously known to the study team but had not been identified by the Phase 1 search. During Phase 3, a total of 72, “citing-” and “cited article” searches were run in Scopus. These searches were based on the 54 relevant articles identified during the title/abstract review of Phase 1 results and on 18 of the 19 articles identified during Phase 2. One of the 19 Phase 2 articles did not have a Scopus record. All citing/cited-article records that contained an infant/child/adolescent/pediatric-related term in either the title, abstract, or keyword fields were added to the project database.

This systematic review was not exploring the impact of palliative care interventions but was instead exploring the impact of participation in the research process associated with palliative care interventions. To be included in our analyses, a paper had to report on the benefit or burden of participation in palliative care research as reported by child, sibling, parent, clinician, or researcher. Only papers with the stated objective of finding out about palliative care research participation benefit or burden were included in final data syntheses.

Randomized clinical trials, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, descriptive quantitative and qualitative reports, and prospective cohort studies were included. Case reports, editorials, and clinical guidelines were excluded. In terms of case reports, the study team was concerned about the introduction of bias and the possibility of duplicate publication if a case study served as a pilot for a larger later palliative care paper. The study team perceived that a case study would not likely include more than a population-based study. The study subject had to include pediatric (defined as age <18 years) palliative care populations or their family members. Pediatric palliative care studies involving palliative care introduction to the family through end-of-life and family bereavement were included.

Seven team members participated in abstract-level eligibility assessment (V.N.M., A.R.N., C.A.F., K.M., K.P.K., K.M.-D., and M.S.W.), with each abstract being independently assessed by two authors. The abstract-level review included rereview of all the articles initially identified in Phase 1. Level of inter-rater agreement at abstract level was >90%. Disagreement between reviewers was resolved by consensus. Full-text eligibility assessment was performed in the same manner with >85% inter-rater agreement at full-text level.

Data extraction occurred through data extraction forms first piloted on five randomly selected included studies and refined (P.S.H., K.M.-D., A.R.N., C.A.F., K.M., and M.S.W.). The full-text data extraction was entered in an online format by two blinded reviewers with a third reviewer checking the extracted data (P.S.H., M.K.U., K.M., K.M.-D., K.P.K., C.J.B., J.L.S., C.A.F., VN.M., A.R.N., and M.S.W.). Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Full-text data extraction form is available in Supplementary Data 1.

Information was extracted from each paper on the following: study characteristics (study design, length, institutional involvement, location and setting, population description, research variables, intervention, control or comparison group, sample size, retention as indicated); benefit or burden of research participation on child, parent, clinician, study team and whose perspective was utilized to report benefit or burden; within-study bias or limitations reported; research barriers reported; and research participation benefit–burden assessment tool utilized. Data synthesis occurred primarily through quantification of shared themes and patterns.

Each study team member was assigned to a stakeholder perspective subgroup (child, parent, sibling, clinician, or researcher perspective) and was tasked with rereviewing the primary research findings with that stakeholder lens. The team then engaged in structured dialog to identify patterns within and across stakeholder groups. Each study team member discussed the benefits and burdens that may explain variations in findings from stakeholder perspectives. Study quality of individual studies was then assessed by two blinded reviewers using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT)—Version 2011.13 The MMAT is a 19-item validated bias and quality checklist tool for appraising the quality of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies.

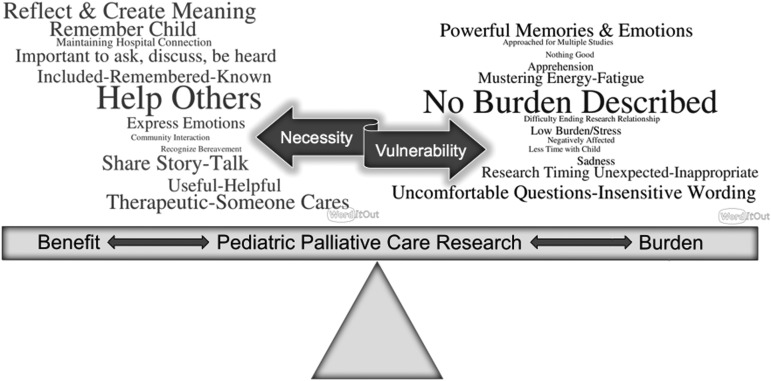

A conceptual framework was developed by data extracting key descriptive words used in the included manuscripts to define or describe the perceived benefit and burden of palliative care research into an Excel document. The words were then iteratively grouped by key phrases across the studies. Two word clouds were created (created at https://worditout.com) with one cloud representing benefits and the other representing burdens across stakeholders (children, their family members, clinicians, and researchers). Larger words in the created image then represented greater frequency of reported benefits/burdens included in the systematic review (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Conceptual model. Conducting pediatric palliative care research requires a delicate balance of weighing the burdens and benefits in this vulnerable population. Word size and color correlate with frequency of finding.

Results

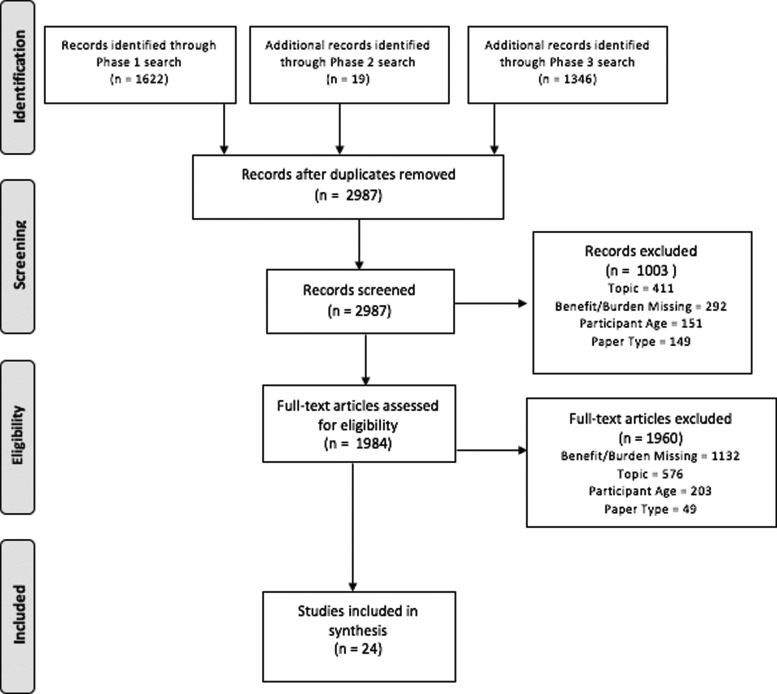

A total of 2445 records were retrieved by the Phase 1 searches (639 MEDLINE, 343 CINAHL, 243 PsycINFO, 608 EMBASE, 418 Scopus, and 194 Cochrane Library records). After removal of 823 duplicate records, 1622 records remained for expert review. The “citing article” searches produced 2078 records. A total of 732 duplicates were removed after the Phase 3 searches were completed, leaving an additional 1346 records from Phase 3. With duplicates removed, the records from Phase 1 (1622), Phase 2 (19), and Phase 3 (1346) together produced a total of 2987 records for expert review. A total of 1003 articles were excluded at abstract level due primarily to topic (41%), benefit/burden report missing (29%), participant age (15%), and paper type (15%). This left 1984 eligible for full-text review, with a total of 1960 papers then excluded at full-text level due to benefit/burden report missing (58%), topic (29%), participant age (10%), and paper type (3%). Twenty-four papers were included in final analysis. PRISMA flow diagram is available in Figure 2.

FIG. 2.

PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA flow diagram depicting paper search, selection, and inclusion process.

Study type included quantitative,3,14–18 qualitative,19–31 mixed methodology,32–34 and literature review.35 Study quality, as appraised by the MMAT score to assess bias and appraise quality across study formats, ranged from 50% to 100% with 8 studies rated at 100% and 7 at <70% (Table 1). Two research interactions regarding benefit/burden assessment were written survey format,16,17 one with online focus group format,23 one with in-person focus group format,36 one with mailed letter,22 three with telephone interaction,22,25,31 and the remainder were in-person interview based.

Table 1.

Summary of Included Papers

| Author last name and study | Year | Study population | Study objective | Benefit assessed by | Benefit described | Burden assessed by | Burden described | Mechanism of reporting benefit/burden | MMAT score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen19 | 2016 | n = 13 Bereaved parents of infants w/HIE | Understand the risks and benefits of conducting sensitive research to understand parental experiences of caring for infants with HIE | Parent | Benefit of expression of intense emotions in a nonjudgmental environment; reflection on child's milestones | — | Burden not reported | Structured interviews with content analysis | 50 |

| Bingen20 | 2011 | n = 16 Parents with child actively receiving palliative care; n = 9 bereaved parents | Explore respondent comfort with completing a parental palliative care parental self-efficacy measure instrument | Parent | 55/58 questions were rated as “important” to ask by >80% of respondents | Parent | 53/58 questions were rated as “comfortable being asked” with 5 questions presumably less comfortable areas of inquiry | Focus group interview format conducted by a psychologist to review family experience using the PCPEM | 66 |

| Briller21 | 2012 | n = 6 Medical professionals and n = 5 bereaved parents | Explore conceptual and design issues encountered in creating a bereaved parents needs assessment in intensive care setting | Parent | Opportunity to express feelings and remember child | Parent | Evocation of powerful memories and emotions | Qualitative interviews to review participant experience in completing the Bereaved Parent Needs Assessment–PICU | 50 |

| Butler22 | 2017 | n = 19 Bereaved parents | Inquire into preferred method of recruitment approach for bereavement studies | Parent | Time and opportunity to “think” about the study and the child; being known, remembered, and included by staff | Parent | Sense of “shock” (2/19) about unexpected research contact after death of child | Interview-based follow-up phone calls with parent participants | 75 |

| Cook23 | 2014 | n = 2 Online focus groups with 220 participant posts over five days | Understand impact of electronic bulletin board focus groups for medically fragile populations | Child | Accessibility; opportunity for reflection; community-building interaction | — | Burden not reported | Analysis of focus group postings and researcher reflection | 50 |

| Currie24 | 2016 | n = 10 Bereaved parents | Inquire about recruitment approach for bereaved parents after death of infant in neonatal intensive care setting | Parent | Freedom to share stories; opportunity to help others, meaning reconstruction, and increased awareness of their own experience | Parent | None of the bereaved parents reported negative experiences associated with research participation in this study or the timing of the interviews | Qualitative interviews | 100 |

| Researcher | |||||||||

| Dallas14 | 2016 | n = 97 Adolescent and surrogate decision-maker dyads | Report the acceptability of and experience with family-centered advance care planning research for adolescents with HIV | Parent | Adolescents and family dyad members, respectively, found participation useful (98%, 98%) and helpful (98%, 100%) | Parent | Experience feelings of sadness with topic (25% parent, 17% child) | Satisfaction Questionnaire by blinded research assistant | 75 |

| Child | Child | ||||||||

| Dyregov32 | 2004 | n = 64 Bereaved parents completed questionnaire and n = 69 interviewed | Describe the research participation experience of bereaved parents | Parent | Research participation was positive/very positive in 100% of respondents; benefit themes of telling the story and helping others | Parent | Parents reported that they experienced “some” anxious/tense feelings before interview, interview required “mustering energy” prior | Qualitative interviews | 100 |

| Eilegard33 | 2013 | n = 187 Bereaved siblings of pediatric patient with cancer | Describe the research participation experience of bereaved siblings | Sibling | 79% of siblings perceived long-term study value such as feeling like their bereavement was more noticed or that participation helped their own grief work | Sibling | 14% of siblings reported emotion as “sad” or “stirred up feelings” | Six-item questionnaire | 66 |

| 84% perceived short-term benefit such as less anxiety and helping others | |||||||||

| Hinds25 | 2007 | Researchers who had participated in at least one of eight end-of-life studies in pediatric oncology | Provide strategies that have been used to implement and complete pediatric end-of-life research studies in oncology | Parent | Positive reports about research participation, including “I like talking about my child,” “I want to help others,” and “I like being in contact with the hospital” | Parent | Only 1 of 191 parents perceived “nothing good” from study participation | Follow-up phone call with three questions to assess positive/negative aspects of participating in research | 100 |

| Researcher | Researcher | ||||||||

| Clinician | Clinician | ||||||||

| Hynson26 | 2006 | n = 69 Bereaved parents | Explore the impact of the research process on bereaved parents | Parent | Desire to benefit others (33/47 interviews) from participation in the research; participation provided therapeutic benefit | Parent | One bereaved parent reported that a later approach by the study team (more than two years post the death of the child) would be more appropriate timing for emotional ability to participate. Note: 19/64 upfront participation decline rate (concern participation “would be too difficult”) | In-depth qualitative interviews | 75 |

| Jacobs15 | 2015 | n = 17 Adolescent and family member dyads | Report on adolescent and surrogate experience in advance care planning research | Clinician | 75% of adolescents believed it was appropriate to discuss end-of-life decisions not only “if dying” | Child | When asked how comfortable are you talking about death, only 12% of adolescent respondents were “not at all comfortable,” and 54% were “somewhat” or “very comfortable” | Oral surveys administered by trained facilitators; written surveys sent to health care providers (after participation in Advance Care Planning research) | 66 |

| Child | |||||||||

| 82% considered it important to let their loved ones know their wishes. | |||||||||

| Eighty-three percent of those providers surveyed felt participation in the study was “somewhat”/“very much” helpful to their patients, and 78% felt it was “somewhat”/“very much” helpful to them as providers | |||||||||

| Kavanaugh27 | 2005 | n = 23 Bereaved parents | Examine the experience of parents surrounding perinatal loss research | Parent | Cited emotional relief, unique opportunity to talk, opportunity to help others, better understanding of experiences, and evidence someone cared | — | Burden not reported | Standard qualitative question regarding participation experience | 75 |

| Kreicbergs16 | 2004 | n = 432 Bereaved parents | Assess the harm and benefit of a questionnaire for bereaved parents | Parent | 285/432 participants reported being positively affected by answering the survey | Parent | 123/432 participants reported being negatively affected by answering the survey | Written survey | 75 |

| Michelson28 | 2006 | n = 70 Parents of hospitalized patients | Examine the reactions of patients' parents to end-of-life decision making research for their child in the intensive care unit | Parent | Perceived sense of “relief” to talk with someone; felt altruistic; opportunity for reflection | — | Burden not reported | Qualitative interview questions | 100 |

| Mongeau29 | 2007 | In-home respite program team members | Report on participatory research projects evaluating a new in-home respite program for children requiring pediatric palliative care | Parent | Parent perspective of “being heard” through research participation; parent goal of improving palliative program through research participation; shared vision | — | Burden not reported | Meeting note analysis, researcher reflections, interview questions | 75 |

| Clinician | |||||||||

| Child | |||||||||

| Price30 | 2013 | n = 2 Nurse reflections on prior interviews with parents of children with complex palliative care needs | Provide guidance on parental research participation for children with life-limiting conditions | — | Benefit not reported | Researcher | Vulnerability based on both topic and timing of data collection; insensitive wording of research documents (e.g., life-limited vs. complex needs) | Narrative review and researcher reflections | 100 |

| Difficulty ending research relationship especially with multiple interviews; emotional impact | |||||||||

| Scott17 | 2002 | n = 81 Bereaved parents | Investigate family members' experiences of involvement in a study following their child's diagnosis with Ewing's sarcoma | Parent | Most parents believed participation would benefit others; 2/3 thought participation was personally beneficial because of communication opportunity; 43% felt the interview “produced good from a bad situation” | Parent | 11% parents shared that some questions made them feel “uncomfortable,” 7% found the interview more painful than expected | Mailed, self-administered follow-up questionnaire in follow-up to prior qualitative research participation | 75 |

| Starks3 | 2016 | n = 220 Pediatric intensive care patients | Describe a research intervention designed to reduce family stress symptoms through early support from the palliative care team | Parent | Parents voiced appreciating “being able to vent”; “feeling cared about” through the interview, and the interview allowing them to gauge their feelings/experiences | Parent | Low burden scores reported by parents related to their participation in research across all three time points: mean (SD) scores were 1.1 (1.6), 0.7 (1.5), and 0.9 (1.6). | Qualitative inquiry thematic content analysis and written question asking parents to rate level of burden on 0–10 point scale with 0 = no burden | 75 |

| Steele37 | 2013 | n = 40 Families to include mothers and fathers | Determine how to improve care for families by obtaining their advice to health care providers and researchers after a child's death from cancer | Parent | Grateful for being remembered and included; maintained connection with the hospital through research; self-expression; helping others; contribution to child's legacy; sense of meaning | — | Burden not reported | Qualitative interviews | 100 |

| Steele34 | 2014 | n = 232 Parents caring for child with progressive and incurable condition | Obtain parents' perceptions about their experience of participating in one of two pediatric palliative care research studies | Parent | 310/322 (96%) thought conducting research about their families' experiences had at least some value; 163/323 (50%) said that the study had at least some positive effect | — | Burden not reported | “Impact of Participation” interview study assessment | 100 |

| Stevens31 | 2010 | n = 91 Family members | Describe the process to design and conduct a research study with families caring for children with life-limiting conditions | Parent | Interviews described as “cathartic” and “helpful”; “no adverse effects” reported by parents or siblings | Parent | Fatigue with interview (tired); emotion of content | Follow-up phone call after qualitative interview | 66 |

| Sibling | Sibling | ||||||||

| Child | Researcher Child |

||||||||

| Taneja18 | 2007 | n = 86 Bereaved parents | Assess parents' perceptions of their experience being interviewed after the death of their child | Parent | Appreciated opportunity to talk about their child; 79/86 reported willingness to participate again | Parent | 75/86 (87.2%) reported that participation was “not at all” or “a little” stressful | Open-ended verbal questions about interview length, stress, and participation experience | 75 |

| Tomlinson35 | 2007 | Review format | Address the ethical and recruitment issues of involving parents of children that are receiving palliative or end-of-life care in research | Researcher | Opportunity to share story and provide input for future palliative care programs | Researcher | Time spent participating in research could be spent in other ways, such as with child; burden of being approached for multiple studies | Review of the literature | 100 |

HIE, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy; MMAT, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool; PCPEM, Pediatric Palliative Care Self-Efficacy Measure; SD, standard deviation.

All studies used a single time point assessment of benefit/burden except four studies that used a two- to five-week follow-up encounter.3,14,27,31 Study population was limited to bereaved participants in 10 papers,16,17,22,24,26,27,32,33,35,37 and combined living and bereaved participants in two papers.20,34 Study locations included the United States,3,14,15,18–21,24,25,27,28,34,37 Canada,23,29,34,35,37 Australia,17,22,26,31 Sweden,16,33 Norway,32 and the United Kingdom.30 Only one paper mentioned inclusion of non-English assessment (Spanish).28 In the ten studies in which ethnic diversity was reported, non-Caucasian ethnic/racial diversity was 0–30% of the participant population in three studies,24,32,37 30–60% in another three,15,19,28 and 100% in one study.27

Specific assessment of benefit/burden of research participation included the following: scale measures,3 open-ended prescripted interview questions,18,22,25,27,28,32 questionnaire items,16,17,20,33 and design of an “Impact of Research” tool (tool validation not reported).34 None of the papers depicted use of a validated tool for assessing benefit, burden, or risk of research participation. Reliability was not reported for scales/questions utilized.

Stated institutional barriers to pediatric palliative care and end-of-life research were depicted as follows: burden presumed by medical personnel,19,30,32 with the term “gatekeeping” used in two papers30,31; concerns raised by institutional ethics committee26; and IRB hesitancy to approve this type of research.16,22,25

Benefit and burden to pediatric participants

Six papers presented the perceived benefits or burdens of palliative care research for the child or adolescent participant. Only four studies included child voice in reporting benefit or burden.14,15,23,31 Two papers focused on the impact of taking part in a randomized controlled trial14,15; three papers on taking part in qualitative research23,29,31; and one provided a comprehensive overview of the ethical and recruitment challenges of engaging parents of children receiving palliative or end-of-life care from the researchers' perspective.35 Stated benefits included the opportunity for the child's voice to be heard and the facilitation of more open and meaningful communication among the child, families, and health care providers.14,15,23 Burdens anticipated by parents and health care providers were associated with risk of emotional or physical imposition upon a child with an already compromised health status and limited life span.29,35 In one study that explored actual burden experienced by children participating in palliative care research, no pediatric adverse events were perceived by parents.31 Unfortunately, little work has been done to document the child's perspective of personal experience with research participation in palliative care and end-of-life settings.

Benefit and burden to sibling participants

Two papers reported potential benefits and burdens in regard to bereaved sibling involvement in research.31,33 Thirteen percent of bereaved siblings reported that completing a research questionnaire was an emotional experience, but none of them anticipated that participation would have any negative long-term effects on them.33 In addition, 99% of siblings indicated that they thought it was valuable to participate in the research study.33 Of 19 siblings from 29 families, one 16-year-old sibling was not able to complete her interview due to emotional distress but reported recovering within several days.31 Limited findings suggest an opportunity to further engage siblings in research surrounding care provided to family members receiving palliative care or at the end of life.

Benefit and burden to parent participants

A total of nineteen studies reported parents' descriptions of their benefits and burdens related to participating in palliative care research. Of these, 19 studies included parent reports of benefits3,14,16–19,21,22,24–29,31,32,34,35,37 and 18 studies reported burdens.3,14,16–22,24–26,28,30–32,34,35

Parents described benefits of research participation in largely intrapersonal and interpersonal ways; participating in research was beneficial intrapersonally because it was helpful for them to talk about their ill child, their family, and to “tell their story”32 to a nonjudgmental researcher and to have an outlet for their emotions. Themes of relief27,28 and positive meaning making24,32,36 were conveyed. Some described therapeutic benefit from participating in the interview or by knowing that this kind of research was being conducted, particularly a sense that the institution cared about parents.26,34,37 In 5 of 21 studies, parents described participation in research as beneficial specifically from an “altruistic” perspective mostly because they hoped other parents or families would benefit from their participation in research.17,21,25,28,37

The largest burdens self-reported by the parents who participated in palliative care research related to timing of research recruitment,25,26,30 the topic of the study,25,30 and the wording of questions.20,28,30 Parents did not want to be away from their dying child to participate in research, or they were not ready to discuss what was happening to their child and family.35 The research topic was reported as painful32 or sad,14 and yet consistently also as healing for parents to tell their story. One study reported that 7% of parent participants noted that participation was more painful than they expected.17 Some parents experienced anticipatory anxiety about research participation; they needed to mentally prepare themselves for participating.32 Of note, across six studies, parents reported an overall higher positive than negative impact from participation in palliative care research.3,16,18,24,25,34

When reported, the percentage of parents who were negatively affected ranged from 0%24,25 to minimal (<1%)3,34 to a high of 28%.16 In addition to the burdens noted, specific concerns about being asked to participate in palliative care research were noted. These concerns included the following: feeling obligated to participate when recruited by a clinical team member35; being shocked by an unexpected contact to recruit the parent to the study22; difficulties evaluating risk/burden for research participation,35 or not having burden disclosed in the consent process.14 In one study, parents discussed the difficulty of ending the research relationship.30 A substantial proportion of parents in another study (87.2%) stated that they would participate in this type of research again.18

Benefit and burden to clinicians

Three papers included clinician benefit15,25,29 and one paper included clinician burden.25 Benefits to clinicians included enhanced communication with and ability to provide support to patients and parents15—as well as opportunities for clinicians to participate in palliative care research and promote translation of findings into practice.25,29 Clinician burden resulted from a desire to protect potential subjects during a vulnerable time.25 Clinician perspective included not only perceived benefit and burden to patient and family but also perceived benefit and burden to oneself as a care provider.

Benefit and burden to researchers

Only one paper included researcher benefit25 and five papers included researcher burden.24,25,30,31,35 When questions to assess patient/family benefits and burdens of participating in a proposed palliative care study were included in the study design, researchers found more successful IRB outcomes.25 Researcher burden was primarily characterized by the actual or potential emotional impact secondary to being immersed in emotionally laden content for prolonged periods of time (through interviews and analyzing data).30,31,35 Other research-related burdens included the stress of adding palliative care studies to clinicians' existing work volume,22 role conflict when participants viewed the interview context as a valuable opportunity to gain advice/support from the researcher as a mental health professional,31 and challenges obtaining approval for this type of research from IRBs.24

Benefits and burdens: A cautious balance

Engaging stakeholders in pediatric palliative care research is a delicate balance that includes potential benefit and burden. A summary of benefits and burdens discovered in this systematic review is presented as a conceptual model (Fig. 1). Words depicting benefit and burden are sized/emboldened in this figure according to their frequency in the included manuscripts. Prominent benefits of palliative care research across stakeholders included altruism and helping others; reflection and reconstruction of memories or creation of meaning; being remembered; sense of inclusion; opportunity to share one's narrative or tell his or her story; and the therapeutic experience of sharing. An actual lack of perceived burden was the most prominent description of burden across stakeholders. When depicted, emotional intensity, fatigue, and the inconvenience of data collection timing were the primary perceived burdens.

Discussion

Despite an exponential increase in pediatric palliative care research in the past decade, there is a paucity of formal inquiry or measurement of the benefits or burdens of this research as experienced by patient, family member, clinician, and researcher. Recognizing the necessity of involving children, their families, and clinicians in research to improve quality care also requires acknowledging the vulnerability and the ethical obligation of supporting seriously ill children and their families during this difficult time. The current evidence is not sufficiently robust to make definitive conclusions about the benefits or burdens of participation in pediatric palliative care and end-of-life research.

Main findings

Pediatric patients, siblings, and parents reported more benefits than burdens associated with participating in palliative care research. There was not an obvious relationship between burden descriptions and type or format of research study. Participating in qualitative research interviews was generally described as positive by family members because of the opportunity for emotional expression and reflection, possibly because of the opportunity made available for connection, and, altruistically, to share wisdom. When approached with a structured, patient-centered protocol, research engaging adolescents and young adults suggests great benefit to eliciting the patient's voice, particularly in advance care planning studies.38–40

Implications for pediatric palliative care clinical research

From the researchers' perspective, there was a noted propensity toward well-intended protectionism with ethics committees, review boards, and clinicians cited as guarding or gatekeeping the study population from perceived risks or anticipated burdens. To avoid engaging in research involving pediatric palliative care patients or end-of-life scenarios is to risk missed opportunities to understand their experiences, good or bad, and to design care interventions that promote ethical methods and high-quality outcomes. A noted propensity toward well-intended protectionism from clinicians was also found. Yet, an inherent bias exists when clinicians only refer certain families they perceive to be doing well to palliative care and bereavement research.2 To address this concern, researchers should consider creative study designs that maintain rigor without disrupting support systems. Furthermore, formalized protocols and standard best practices are needed to reduce burden and enhance benefit to this vulnerable population.

Pediatric palliative care research warrants estimating benefit and burden as part of research reporting. Pediatric palliative care and end-of-life research was noted to be highly relational research, impactful even to the researcher as coparticipant. However, no reviewed study formally included benefit and burden assessment for all study stakeholders. Due to the interconnected nature of pediatric palliative care research topics, future studies would ideally explore benefit and burden not just to child and family but also to clinician and researcher. Perhaps, more concise definitions of benefit and burden would be of use. We do not know if the burden reported when participating in a pediatric palliative care study is associated with harm. Similarly, is benefit associated with helpfulness? New measures should also consider anchors of time. For example, a study might be burdensome or difficult for the participant for a few hours though the benefit long lasting. A study that is carried out during early palliative care integration may carry unique benefits and burdens, whereas a study that is carried out during late bereavement phase may carry different benefits and burdens. The current reporting of benefits and burdens does not allow for clear delineation as to the ways these realities may differ by time points.

The emotional impact of conducting this type of research was often noted. One paper recommended use of peer and expert debriefing to help combat the emotional impact of large amounts of highly emotional data, and suggested conducting data analyses in stages interspersed with other processes to remove the researcher from the continuous immersion in the data.30 Finding ways to professionally and comfortably exit the trusting relationship after the study measures/interview(s) are completed was noted to be challenging to both the research team and participant, especially if the relationship developed over repeated interviews and contacts.30,41 The nature of pediatric palliative care topics warrants thorough planning and training for the management of the research process, research activities, and potential benefits and burdens of the research experienced by participants, clinicians, and researchers alike.

Limitations, strengths, and future study opportunities

Limitations of the review itself included variability of quality within the reviewed studies, variety of research questions asked in primary studies, publication bias, and inability to synthesize data into meta-analysis due to the heterogeneous nature of the methodologies and populations. A limitation of the search includes restriction to English-language publications.

Our study has several strengths. We registered our protocol á priori enhancing transparency and rigor of data extraction and analysis. We included an interdisciplinary pediatric palliative care study team with members from medicine, nursing, psychology, and social work. Team members were blinded at each step in the review process. A validated tool (MMAT) was utilized to appraise study quality. A research librarian was included in the search strategy with inclusion of multiple databases and a 17-year publication period. A future comprehensive approach might be to consider identifying pediatric palliative care research papers written in a longitudinal time frame to then engage in content analysis on all mentions of benefit or burden for papers published in the field over a given time span.

Conclusion

Standards of care in research are essential for guidance and best practice. Quantitative and/or qualitative assessment tools that measure benefit and burden specific to palliative and end-of-life care research would aid quality research, and provide reassurance to ethics committees or IRBs.42 In addition, some centers may decline to consider pediatric palliative care research as needing formal institutional review, which risks an unregulated field without a standard for assessing harm and risk of this research. Fortunately, benefit and burden scales for participation in clinical cancer trials are underdevelopment.42

The reality that no included study utilized a benefit/burden tool with reported validity or reliability compels urgent adaptation of such an instrument for the pediatric palliative care setting. An implementable tool to quantify and qualify stakeholder benefit/burden could translate into a triaged care intervention as best practice in pediatric palliative care and end-of-life research. Novel, well-designed approaches should be considered to develop instruments for measuring benefit and burden of research participation for children, family members, clinicians, and study teams. A standard approach to measuring benefit and burden in pediatric palliative care research could translate into a field expectation of universally reporting benefit and burden to further advance the field's science in a participant-centric manner.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study team thanks the Pediatric Palliative Care Special Interest Group at Children's National Medical Center. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health and National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Human subjects were not involved in this systematic review methodology.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Twycross RG: Research and palliative care: The pursuit of reliable knowledge. Palliat Med 1993;7:175–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crocker JC, Beecham E, Kelly P, et al. : Inviting parents to take part in paediatric palliative care research: A mixed-methods examination of selection bias. Palliat Med 2015;29:231–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Starks H, Doorenbos A, Lindhorst T, et al. : The Family Communication Study: A randomized trial of prospective pediatric palliative care consultation, study methodology and perceptions of participation burden. Contemp Clin Trials 2016;49:15–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burnell RH, O'Keefe M: Asking parents unaskable questions. Lancet 2004;364:737–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lantos JD: Should institutional review board decisions be evidence-based? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007;161:516–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rapoport A: Addressing ethical concerns regarding pediatric palliative care research. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:688–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Duke S, Bennett H: Review: A narrative review of the published ethical debates in palliative care research and an assessment of their adequacy to inform research governance. Palliat Med 2010;24:111–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dixon-Woods M, Young B, Ross E: Researching chronic childhood illness: The example of childhood cancer. Chronic Illness 2006;2:165–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pessin H, Galietta M, Nelson CJ, et al. : Burden and benefit of psychosocial research at the end of life. J Palliat Med 2008;11:627–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wiener L, Battles H, Zadeh S, Pao M: Assessing the experience of medically ill youth participating in psychological research: Benefit, burden, or both? IRB 2015;37:1–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Parkes CM: Guidelines for conducting ethical bereavement research. Death Stud 1995;19:171–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Read K, Fernandez CV, Gao J, et al. : Decision-making by adolescents and parents of children with cancer regarding health research participation. Pediatrics 2009;124:959–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pluye P: Mixed kinds of evidence: Synthesis designs and critical appraisal for systematic mixed studies reviews including qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies. Evid Based Med 2015;20:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dallas RH, Kimmel A, Wilkins ML, et al. : Acceptability of family-centered advanced care planning for adolescents with HIV. Pediatrics 2016;138:pii: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jacobs S, Perez J, Cheng YI, et al. : Adolescent end of life preferences and congruence with their parents' preferences: Results of a survey of adolescents with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62:710–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdottir U, Steineck G, Henter JI: A population-based nationwide study of parents' perceptions of a questionnaire on their child's death due to cancer. Lancet 2004;364:787–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Scott DBF, Bain CJ, Valery PC: Does research into sensitive areas do harm? Experiences of research participation after a child's diagnosis with Ewing's sarcoma. Med J Aust 2002;177:507–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taneja GS, Brenner RA, Klinger R, et al. : Participation of next of kin in research following sudden, unexpected death of a child. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007;161:453–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Allen KA, Kelley TF: The risks and benefits of conducting sensitive research to understand parental experiences of caring for infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Neurosci Nurs 2016;48:151–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bingen K, Kupst MJ, Himelstein B: Development of the palliative care parental self-efficacy measure. J Palliat Med 2011;14:1009–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Briller SH, Schim SM, Thurston CS, Meert KL: Conceptual and design issues in instrument development for research with bereaved parents. Omega (Westport) 2012;65:151–168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Butler AE, Hall H, Copnell B: Ethical and practical realities of using letters for recruitment in bereavement research. Res Nurs Health 2017;40:372–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cook K, Jack S, Siden H, et al. : Innovations in research with medically fragile populations: Using bulletin board focus groups. Qual Rep 2014;19:1–12 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Currie ER, Roche C, Christian BJ, et al. : Recruiting bereaved parents for research after infant death in the neonatal intensive care unit. Appl Nurs Res 2016;32:281–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hinds PS, Burghen EA, Pritchard M: Conducting end-of-life studies in pediatric oncology. West J Nurs Res 2007;29:448–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hynson JL, Aroni R, Bauld C, Sawyer SM: Research with bereaved parents: A question of how not why. Palliat Med 2006;20:805–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kavanaugh K, Hershberger P: Perinatal loss in low-income African American parents. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2005;34:595–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Michelson KN, Koogler TK, Skipton K, et al. : Parents' reactions to participating in interviews about end-of-life decision making. J Palliat Med 2006;9:1329–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mongeau S, Champagne M, Liben S: Participatory research in pediatric palliative care: Benefits and challenges. J Palliat Care 2007;23:5–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Price JN, Nicholl H: Interviewing parents for qualitative research studies: Using an ABCD to manage the sensitivities and issues. Child Care Pract 2013;19:199–213 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stevens MM, Lord BA, Proctor MT, et al. : Research with vulnerable families caring for children with life-limiting conditions. Qual Health Res 2010;20:496–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dyregrov K: Bereaved parents' experience of research participation. Soc Sci Med 2004;58:391–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eilegard A, Steineck G, Nyberg T, Kreicbergs U: Bereaved siblings' perception of participating in research—A nationwide study. Psychooncology 2013;22:411–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Steele R, Cadell S, Siden H, et al. . Impact of research participation on parents of seriously ill children. J Palliat Med 2014;17:788–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tomlinson D, Bartels U, Hendershot E, et al. . Challenges to participation in paediatric palliative care research: A review of the literature. Palliat Med 2007;21:435–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tomlinson D, Capra M, Gammon J, et al. : Parental decision making in pediatric cancer end-of-life care: Using focus group methodology as a prephase to seek participant design input. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2006;10:198–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Steele AC, Kaal J, Thompson AL, et al. : Bereaved parents and siblings offer advice to health care providers and researchers. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2013;35:253–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wiener L, Ballard E, Brennan T, et al. . How I wish to be remembered: The use of an advance care planning document in adolescent and young adult populations. J Palliat Med 2008;11:1309–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Curtin KB, Watson AE, Wang J, et al. : Pediatric advance care planning (pACP) for teens with cancer and their families: Design of a dyadic, longitudinal RCCT. Contemp Clin Trials 2017;62:121–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lyon ME, Garvie PA, Briggs L, et al. : Is it safe? Talking to teens with HIV/AIDS about death and dying: A 3-month evaluation of Family Centered Advance Care (FACE) planning—Anxiety, depression, quality of life. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2010;2:27–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bell CJ, Zimet GD, Hinds PS, et al. : Refinement of a conceptual model for adolescent readiness to engage in end-of-life discussions. Cancer Nurs 2018;41:E21–E39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ulrich CM, Zhou QP, Ratcliffe SJ, et al. : Development and preliminary testing of the perceived benefit and burden scales for cancer clinical trial participation. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2018;13:230–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.