Cyclic di-GMP and associated signaling proteins are widespread in bacteria, but their role in physiology is often complex and difficult to predict through genomic level analyses. In C. crescentus, c-di-GMP has been integrated into the developmental cell cycle, but there is increasing evidence that environmental factors can impact this system as well. The research presented here suggests that the integration of these signaling networks could be more complex than previously hypothesized, which could have a bearing on the larger field of c-di-GMP signaling. In addition, this work further reveals similarities and differences in a conserved regulatory network between organisms in the same taxonomic family, and the results show that gene conservation does not necessarily imply close functional conservation in genetic pathways.

KEYWORDS: Brevundimonas, Caulobacter, c-di-GMP, development, divK, signaling

ABSTRACT

The DivJ-DivK-PleC signaling system of Caulobacter crescentus is a signaling network that regulates polar development and the cell cycle. This system is conserved in related bacteria, including the sister genus Brevundimonas. Previous studies had shown unexpected phenotypic differences between the C. crescentus divK mutant and the analogous mutant of Brevundimonas subvibrioides, but further characterization was not performed. Here, phenotypic assays analyzing motility, adhesion, and pilus production (the latter characterized by a newly discovered bacteriophage) revealed that divJ and pleC mutants have phenotypes mostly similar to their C. crescentus homologs, but divK mutants maintain largely opposite phenotypes than expected. Suppressor mutations of the B. subvibrioides divK motility defect were involved in cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) signaling, including the diguanylate cyclase dgcB, and cleD which is hypothesized to affect flagellar function in a c-di-GMP dependent fashion. However, the screen did not identify the diguanylate cyclase pleD. Disruption of pleD in B. subvibrioides caused no change in divK or pleC phenotypes, but did reduce adhesion and increase motility of the divJ strain. Analysis of c-di-GMP levels in these strains revealed incongruities between c-di-GMP levels and displayed phenotypes with a notable result that suppressor mutations altered phenotypes but had little impact on c-di-GMP levels in the divK background. Conversely, when c-di-GMP levels were artificially manipulated, alterations of c-di-GMP levels in the divK strain had minimal impact on phenotypes. These results suggest that DivK performs a critical function in the integration of c-di-GMP signaling into the B. subvibrioides cell cycle.

IMPORTANCE Cyclic di-GMP and associated signaling proteins are widespread in bacteria, but their role in physiology is often complex and difficult to predict through genomic level analyses. In C. crescentus, c-di-GMP has been integrated into the developmental cell cycle, but there is increasing evidence that environmental factors can impact this system as well. The research presented here suggests that the integration of these signaling networks could be more complex than previously hypothesized, which could have a bearing on the larger field of c-di-GMP signaling. In addition, this work further reveals similarities and differences in a conserved regulatory network between organisms in the same taxonomic family, and the results show that gene conservation does not necessarily imply close functional conservation in genetic pathways.

INTRODUCTION

Though model organisms represent a small portion of the biodiversity found on Earth, the research that has resulted from their study shapes much of what we know about biology today. The more closely related species are to a model organism, the more that theoretically can be inferred about them using the information from the model organism. Modern genomic studies have given this research an enlightening new perspective. Researchers can now compare the conservation of particular systems genetically. Using model organisms can be a very efficient and useful means of research, but the question still remains of how much of the information gained from the study of a model can be extrapolated unto other organisms. Though genomic comparison shows high levels of conservation between genes of different organisms, this does not necessarily mean the function of those genes or systems has been conserved. This phenomenon seems to be evident in the Caulobacter crescentus system.

C. crescentus is a Gram-negative alphaproteobacterium that lives a dimorphic lifestyle. It has been used as a model organism for the study of cell cycle regulation, intracellular signaling, and polar localization of proteins and structures in bacteria. The C. crescentus life cycle begins with the presynthetic (G1) phase in which the cell is a motile “swarmer cell” which contains a single flagellum and multiple pili at one of the cell’s poles (for a review, see reference 1). During this period of the life cycle, the cell cannot replicate its chromosome or perform cell division. Upon differentiation, the cell dismantles its pili and ejects its flagellum. It also begins to produce holdfast, an adhesive polysaccharide, at the same pole from which the flagellum was ejected. The cell then develops a stalk, projecting the holdfast away from the cell at the tip of the stalk. The differentiation of the swarmer cell to the “stalked cell” marks the beginning of the synthesis (S) phase of the cell life cycle as chromosome replication is initiated. As the stalked cell replicates its chromosome and increases its biomass in preparation for cell division, it is referred to as a predivisional cell. Toward the late predivisional stage, it again becomes replication incompetent and enters the postsynthetic (G2) phase of development. At the end of the G2 phase, the cell completes division, forming two different cell types. The stalked cell can immediately reenter the S phase, while the swarmer cell moves once again through the G1 phase.

Brevundimonas subvibrioides is another Gram-negative alphaproteobacterium found in oligotrophic environments that lives a dimorphic lifestyle like that of C. crescentus. Brevundimonas is the next closest genus phylogenetically to Caulobacter. According to a pairwise average nucleotide identity (ANI) test, their genomes are approximately 74% identical. Bioinformatic analyses showed that all developmental signaling proteins found in the C. crescentus cell cycle are conserved B. subvibrioides (2, 3). All the known developmental regulators found in C. crescentus are also present in B. subvibrioides, and these regulators are orthologs since they are bidirectional best hits when searched against each genome, and amino acid identity is extremely high (3) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Conversely, no other proteins thought to interact with DivK in more distantly related Alphaproteobacteria, such as PdhS1 or CbrA, are apparent in the B. subvibrioides genome. However, little physiological characterization has been performed. Conservation of genes does not necessarily mean conservation of function or properties (3). Essential gene studies within the Alphaproteobacteria have shown that gene essentiality/nonessentiality in one organism does not always correspond with that in another organism (3–6). Analyses that have been performed on C. crescentus and B. subvibrioides have shown many similarities in gene essentiality between the two but have shown several surprising differences as well (3).

In C. crescentus, the DivJ-DivK-PleC system controls the spatial activation of one of the master regulators in C. crescentus, CtrA (1, 7). This system is a prime example of how C. crescentus has evolved traditional two-component proteins into a more complex signaling pathway and, as a result, has developed a more complex life cycle. The DivJ-DivK-PleC pathway consists of two histidine kinases (PleC and DivJ) and a single response regulator (DivK) (8, 9). DivJ is absent in swarmer cells but is produced during swarmer cell differentiation. It then localizes to the stalked pole (8). DivJ is required for, among other things, proper stalk placement and regulation of stalk length. C. crescentus divJ mutants display filamentous shape, a lack of motility, and holdfast overproduction (8, 9).

PleC localizes to the flagellar pole during the predivisional cell stage (10). Though structurally a histidine kinase, PleC acts as a phosphatase, constitutively dephosphorylating DivK (8, 9). C. crescentus pleC mutants display a lack of pili, holdfast, and stalks and have paralyzed flagella, leading to a loss of motility (11–13). DivK is a single-domain response regulator (it lacks an output domain) whose location is dynamic throughout the cell cycle (9, 14). DivK remains predominantly unphosphorylated in the swarmer cell, while it is found mostly in its phosphorylated form in stalked cells. Photobleaching and FRET (fluorescence resonance energy transfer) analyses show that DivK shuttles rapidly back and forth from pole to pole in the predivisional cell depending on its phosphorylation state (9). Previous studies have shown that phosphorylated DivK localizes bipolarly, whereas primarily unphosphorylated DivK is delocalized throughout the cell (9). A divK cold-sensitive mutant suppresses the nonmotile phenotype of pleC at 37°C. However, at 25°C, it displays extensive filamentation much like the divJ mutant (15). In addition, filamentous divK cells sometimes had multiple stalks, though the second stalk was not necessarily polar. Furthermore, electron microscopy of divK disruption mutants led to the discovery that they lack flagella.

Upon completion of cytokinesis, PleC and DivJ are segregated into different compartments, thus DivK phosphorylation levels in each compartment are dramatically different. This leads to differential activation of CtrA in the different compartments (9, 16). In the swarmer cell, the dephosphorylated DivK leads to the downstream activation of CtrA. CtrA in its active form binds the chromosome at the origin of replication and prevents DNA replication (17, 18). The opposite effect is seen in stalked cells, where highly phosphorylated DivK results in the inactivation of CtrA and therefore permits DNA replication (19).

Gene essentiality studies in B. subvibrioides led to the discovery of a discrepancy in the essentiality of DivK. In C. crescentus DivK is essential for growth, while in B. subvibrioides DivK is dispensable for growth (3, 15). Further characterization found dramatic differences in the phenotypic consequences of disruption. Through the use of a cold-sensitive DivK allele or by ectopic depletion, C. crescentus divK disruption largely phenocopies divJ disruption in cell size and motility effects (8, 9, 15). This is to be expected since DivK∼P is the active form and disruption of either divJ or divK reduces DivK∼P levels. In B. subvibrioides, disruption of divJ leads to the same effects in cell size, motility, and adhesion (3). However, divK disruption leads to opposite phenotypes of cell size and adhesion, and while motility is impacted, it is likely by a different mechanism.

While the previous study revealed important differences between the organisms (3), it did not analyze the impact of PleC disruption, nor did it examine pilus production or subcellular protein localization. The work presented here further characterizes the DivJ-DivK-PleC signaling system in B. subvibrioides and begins to address the mechanistic reasons for the unusual phenotypes displayed by the B. subvibrioides divK mutant.

RESULTS

Deletion mutants in the B. subvibrioides DivJ-DivK-PleC system result in varied phenotypes compared to that of analogous C. crescentus mutations.

In the previous study done in Brevundimonas subvibrioides (3), deletion mutants of the genes divJ and divK, as well as a divJ divK double mutant, were made and partially characterized, uncovering some starkly different phenotypes compared to the homologous mutants in C. crescentus. However, characterization of this system was not complete since it did not extend to a key player in this system: PleC. As previously mentioned, C. crescentus pleC mutants display a lack of motility, pili, holdfast, and stalks (20). To begin examining the role of PleC in B. subvibrioides, an in-frame deletion of the pleC gene (Bresu_0892) was created. This strain, along with the previously published divJ, divK, and divJ divK strains, was used in a swarm assay to analyze motility. All mutant strains displayed reduced motility in swarm agar compared to the wild type (Fig. 1A; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This had been reported for the published strains (3). The mechanistic reasons for this are unclear. All were observed to produce flagella and were seen to swim when observed microscopically. The divJ strain has a significantly filamentous cell shape, which is known to inhibit motility through soft agar, but the divK and divJ divK cells are actually shorter than wild-type cells. The nature of the pleC motility defect is also unknown. The cell sizes of the pleC mutants were not noticeably different from those of wild-type cells (Fig. 1B). The C. crescentus pleC mutant is known to have a paralyzed flagellum, which leads to a null motility phenotype, but B. subvibrioides pleC mutants were observed swimming under the microscope, suggesting that unlike C. crescentus their flagella remain functional. While the mechanistic reason for this discrepancy is unknown, it does provide another important difference in developmental signaling mutants between the two organisms.

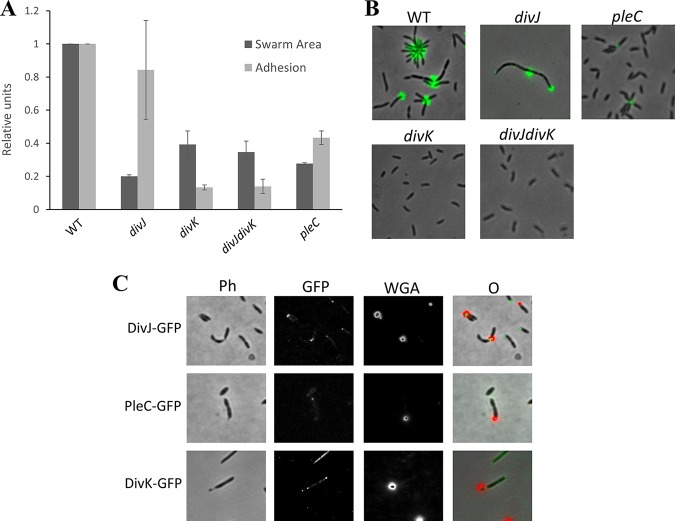

FIG 1.

Deletions in B. subvibrioides developmental signaling genes results in various physiological phenotypes. (A) Wild-type, divJ, divK, divJ divK, and pleC B. subvibrioides strains were analyzed for swarm expansion and adhesion defects using a soft agar swarm assay and a short-term adhesion assay. Mutant strains were normalized to wild-type results for both assays. Deletion of divJ gives motility defects but minimal adhesion defects, similar to C. crescentus divJ results. B. subvibrioides divK and divJ divK strains yielded opposite results, with severe motility and adhesion defects. The B. subvibrioides pleC strain has reduced motility and moderately reduced adhesion, which is similar but not identical to the C. crescentus pleC strain. (B) Lectin staining of holdfast material of wild-type, divJ, divK, divJ divK, and pleC strains. The pleC strain, despite having reduced adhesion in the short-term adhesion assay, still has detectable holdfast material. (C) GFP-tagged DivJ localizes to the holdfast-producing pole, while PleC-GFP localizes to the pole opposite the holdfast. DivK-GFP displays bipolar localization. These localization patterns are identical to those of C. crescentus homologs.

To further the phenotypic characterization, these strains were analyzed for surface adhesion properties using both a short-term adhesion assay and staining holdfast material with a fluorescently conjugated lectin. As previously reported, the divK and divJ divK strains had minimal adhesion and no detectable holdfast material (Fig. 1A and B). It was previously reported that the divJ strain had increased adhesion compared to the wild type, but in this study we found it to have slightly reduced adhesion compared to the wild type. It is not clear whether this difference in results between the two studies is significant. The pleC strain had reduced adhesion compared to the wild type but more adhesion than the divK or divJ divK strains. When analyzed by microscopy, the pleC strain was found to still produce detectable holdfast (Fig. 1B; Fig. S2), which is a difference from the C. crescentus pleC strain, where holdfast was undetectable (20, 21).

An important component to the function of this signaling system is the subcellular localization of DivJ and PleC to the stalked and flagellar poles, respectively. Since the localization of these proteins had yet to be characterized in B. subvibrioides, green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged constructs were generated such that the tagged versions were under native expression. Because B. subvibrioides cells very rarely produce stalks under nutrient-replete conditions (22), holdfast material was stained using a wheat germ agglutinin lectin conjugated with a fluorophore that uses red fluorescent protein imaging conditions. When the divJ-gfp strain was analyzed (n = 403 cells), the majority of cells (82.9%) had no detectable signal (Fig. 1C). It is not clear whether this means the cells are not producing DivJ or whether the level is below the detection limit. When cells had detectable fluorescence, it was seen only as a unipolar focus (17.1%). When cells had detectable DivJ-GFP foci and labeled holdfast, the foci were found exclusively at the holdfast pole (n = 55 cells). When the pleC-GFP strain was imaged (n = 433 cells), most cells displayed a unipolar focus (68.8%). Only 28.9% of cells displayed no fluorescence. A small number of cells (2.3%) had seemingly bipolar PleC localization; these cells may be transitioning from the swarmer to stalked state. Of the cells that had detectable PleC-GFP foci and labeled holdfast (n = 38), all PleC-GFP foci were found at the pole opposite the holdfast (Fig. 1C; Fig. S3). Because it has been demonstrated that holdfast material is produced at the same pole as the stalk in B. subvibrioides (22), this result suggests that these proteins demonstrate the same localization patterns as their C. crescentus counterparts. DivK-GFP was seen to form different localization patterns in different cells (Fig. 1C; Fig. S4). Of the 431 cells counted, the vast majority (85.8%) showed total cell fluorescence with no distinct localization. Bipolar localization was seen in 6.3% of cells, and unipolar localization was seen in 7.9% of cells. Of the cells that displayed unipolar localization and a detectable holdfast, DivK-GFP was localized almost exclusively to the stalked pole (96.3%, n = 27). These results contrast with C. crescentus results in some ways. In C. crescentus DivK-GFP was found predominantly bipolarly localized (56%), with 12% displaying stalked pole localization and 32% displaying no detectable fluorescence (23), though this quantification was performed using stalked cells specifically. Diffuse total body fluorescence was not reported in that study, but it is known that DivK-GFP is diffuse in swarmer cells. It should be noted that the work in C. crescentus expressed divK-gfp from a low-copy-number plasmid using the native promoter, while here a plasmid integration scheme was used to create a merodiploid; however, both strains had both tagged and untagged versions of divK, each expressed by native promoters, so it is not clear whether strain construction is the cause of the differences in localization pattern. Therefore, DivJ and PleC localizations match the C. crescentus model, whereas DivK appears to spend most of the time delocalized (with some bipolar and stalked pole localization), as opposed to C. crescentus, where the protein appears to spend most of the time bipolarly localized. This is another case where the histidine kinase results somewhat match between organisms, while the response regulator results are quite different.

Isolation of a bacteriophage capable of infecting B. subvibrioides.

Another important developmental event in C. crescentus is the production of pili at the flagellar pole coincident with cell division. Pili are very difficult to visualize, and in C. crescentus the production of pili in strains of interest can be assessed with the use of the bacteriophage ΦCbK, which infects the cell using the pilus. Resistance to the phage indicates the absence of pili. However, bacteriophage that infect C. crescentus do not infect B. subvibrioides (data not shown) despite their close relationship. In an attempt to develop a similar tool for B. subvibrioides, a phage capable of infecting this organism was isolated.

Despite the fact that B. subvibrioides was isolated from a freshwater pond in California over 50 years ago, a phage capable of infecting the bacterium was isolated from a freshwater pond in Lafayette County, Mississippi. This result is a testament to the ubiquitous nature of Caulobacter and Brevundimonas species in freshwater environments all over the globe. This phage has been named Delta, after the state’s famous Mississippi Delta region. To determine the host range for this phage, it was tested against multiple Brevundimonas species (Fig. 2A). Delta has a relatively narrow host range, causing the largest reduction of cell viability in B. subvibrioides and B. aveniformis, with some reduction in B. basaltis and B. halotolerans as well. None of the other 14 Brevundimonas species showed any significant reduction in cell viability. Neither did Delta show any infectivity toward C. crescentus (data not shown). While B. subvibrioides, B. aveniformis, and B. basaltis all belong to the same subclade within the Brevundimonas genus (P. Caccamo and Y. V. Brun, unpublished data), so do B. kwangchunensis, B. alba, and B. lenta, all of which are more closely related to B. subvibrioides than to B. aveniformis and all of which were resistant to the phage. Therefore, infectivity does not appear to fall along clear phylogenetic lines and may be determined by some other factor.

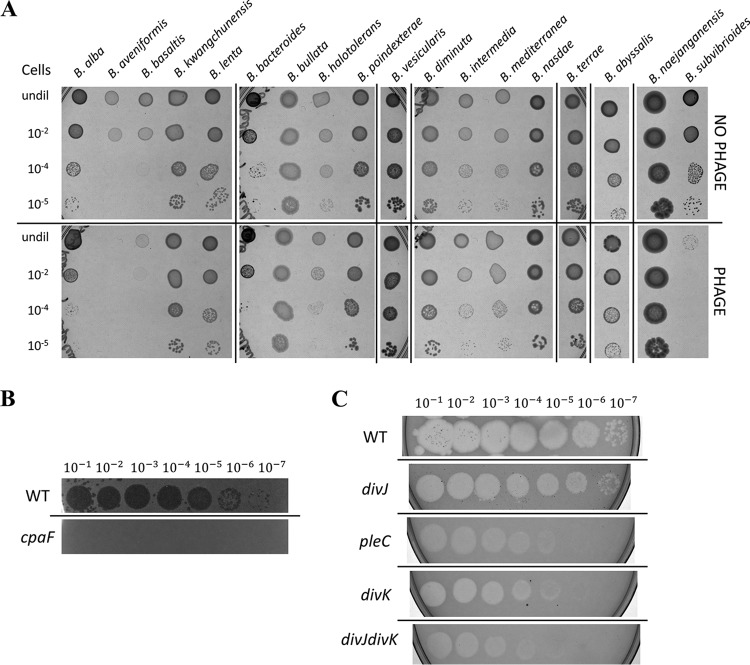

FIG 2.

Bacteriophage Delta serves as a tool to investigate B. subvibrioides pilus production. (A) Phage Delta was tested for infection in 18 different Brevundimonas species. Control assays used PYE medium instead of phage stock. Delta caused a significant reduction in B. subvibrioides and B. aveniformis viability, with some reduction in B. basaltis and B. halotolerans as well. (B) Phage Delta was tested against wild-type and cpaF::pCR B. subvibrioides strains using a soft agar phage assay. The wild type displayed zones of clearing with phage dilutions up to 10−7, whereas the cpaF strain showed resistance to all phage dilutions. (C) B. subvibrioides developmental signaling mutants were tested with phage Delta in soft agar phage assays. The wild type shows clear susceptibility to Delta, as does the divJ strain, suggesting that, like C. crescentus divJ, it produces pili. The pleC strain shows a 2- to 3-order-of magnitude-reduced susceptibility to the phage, indicating reduced pilus production, which is consistent with the C. crescentus phenotype. The divK and divJ divK strains display a resistance similar to that of the pleC strain. Here again, divK disruption causes the opposite phenotype to divJ disruption, unlike the C. crescentus results.

To begin identifying the infection mechanism of Delta, B. subvibrioides was randomly mutagenized with a Tn5 transposon, and resulting transformants were mixed with Delta to select for transposon insertions conferring phage resistance as a way to identify the phage infection mechanism. Phage-resistant mutants were readily obtained and maintained phage resistance when rescreened. A number of transposon insertion sites were sequenced, and several were found in the pilus biogenesis cluster homologous to the C. crescentus flp-type pilus cluster. Insertions were found in the homologs for cpaD, cpaE, and cpaF; it is known that disruption of cpaE in C. crescentus abolishes pilus formation and leads to ΦCbK resistance (23–25). A targeted disruption was made in cpaF and tested for phage sensitivity by a soft agar assay (Fig. 2B). The cpaF disruption caused complete resistance to the phage. The facts that multiple transposon insertions were found in the pilus cluster and that the cpaF disruption leads to phage resistance strongly suggest that Delta utilizes the B. subvibrioides pilus as part of its infection mechanism. The identification of another pilus-tropic phage is not surprising since pili are major phage targets in multiple organisms.

Phage Delta was used to assess the potential pilus production in developmental signaling mutants using the soft agar assay (Fig. 2C). The divJ mutant has a susceptibility to Delta similar to that of the wild type, suggesting that this strain still produces pili. This result is consistent with the C. crescentus result since the C. crescentus divJ mutant is ΦCbK susceptible (8). Conversely, the B. subvibrioides pleC mutant shows a clear reduction in susceptibility to Delta, indicating that this strain is deficient in pilus production. If so, this would also be consistent with the C. crescentus pleC mutant, which is resistant to ΦCbK (8, 20). With regard to the divK strain, if that mutant was to follow the C. crescentus model it should demonstrate the same susceptibility as the divJ strain. Alternatively, since the divK strain has often demonstrated opposite phenotypes to divJ in B. subvibrioides, one might predict it to demonstrate resistance to Delta. As seen in Fig. 2C, the divK strain (and the divJ divK strain) shows the same level of resistance to phage Delta as the pleC mutant. Therefore, in regard to phage sensitivity, the divK strain is once again opposite of the prediction of the C. crescentus model. Interestingly, none of these developmental signaling mutants demonstrate complete resistance to Delta as seen in the cpaF strain. This result suggests that these mutations impact pilus synthesis but do not abolish it completely.

A suppressor screen identifies mutations related to c-di-GMP signaling.

Since the B. subvibrioides divK mutant displays the most unusual phenotypes with regard to the C. crescentus model, this strain was selected for further analysis. Complementation of divK was attempted by expressing wild-type DivK from an inducible promoter on a replicating plasmid; however, induction failed to complement any of the divK phenotypes (data not shown), indicating that proper complementation conditions have not yet been identified. Transposon mutagenesis was performed on this strain, and mutants were screened for those that had increased motility. Two mutants were found (Bresu_1276 and Bresu_2169) that restored motility to the divK strain and maintained this phenotype when recreated by plasmid insertional disruption. Both mutants were involved in c-di-GMP signaling. The C. crescentus homolog of the Bresu_1276 gene, CC3100 (42% identical to Bresu_1276), was recently characterized in a subcluster of CheY-like response regulators and renamed CleD (26). The function of CleD is, at least in part, initiated by binding c-di-GMP via an arginine-rich region with high affinity and specificity for c-di-GMP. Upon binding, roughly 30% of CleD localizes to the flagellated pole of the swarmer cell. Nesper et al. suggest that CleD may bind directly to the flagellar motor switch protein, FliM. In Escherichia coli and Salmonella, the flagellar brake protein YcgR interacts with FliM in a c-di-GMP-dependent manner, biasing the motor in the smooth-running counterclockwise direction (27, 28), but YcgR is not a response regulator-type protein, and no obvious YcgR homologs are present in the C. crescentus or B. subvibrioides genomes (data not shown). Based upon the C. crescentus findings, it was hypothesized that increased c-di-GMP levels cause activation of CleD, which binds to the flagellar switch and inhibits flagellar function (26). In C. crescentus, cleD mutants are 150% more motile, while their adhesion does not differ significantly from that of the wild type. Unlike conventional response regulators, the phosphoryl-receiving aspartate is replaced with a glutamate in CleD. In other response regulators, replacement of the aspartate with a glutamate mimics the phosphorylated state and locks the protein in an active conformation. Alignment of CleD with orthologs from various Caulobacter and Brevundimonas species demonstrated that this was a conserved feature of CleD within this clade (Fig. 3). Similar to C. crescentus, the swarm size of B. subvibrioides cleD mutant increased to 151% compared to the wild type. A knockout of cleD in the divK background led to a complete restoration of motility compared to that of the wild type, whereas adhesion did not appear to be affected (Fig. 4A). These phenotypes correspond relatively well with the model given by Nesper et al. Since CleD is thought to inhibit motor function, a cell lacking CleD would have less motor inhibition, leading to an increase in motility and a delay in surface attachment, though cleD disruption had no impact on the phage sensitivity phenotypes of the wild-type or divK-derived strains (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material).

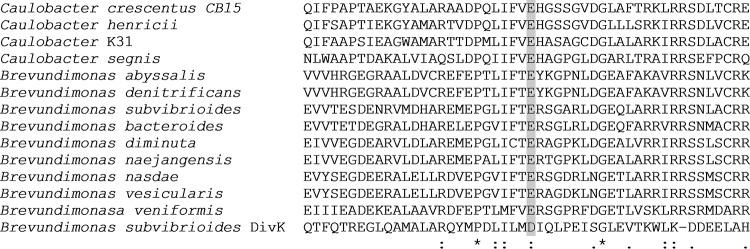

FIG 3.

CleD displays a conserved glutamate residue in place of an aspartate typical of response regulators. CleD orthologs from various Caulobacter and Brevundimonas species were aligned by ClustalW, along with B. subvibrioides DivK. The shaded box indicates B. subvibrioides DivK D53, which is analogous to C. crescentus DivK D53 and is the known phosphoryl-accepting residue. This alignment demonstrates that CleD orthologs all contain a glutamate substitution at that site, which has been found to mimic the phosphorylated state and lock the protein in an active conformation in other response regulators.

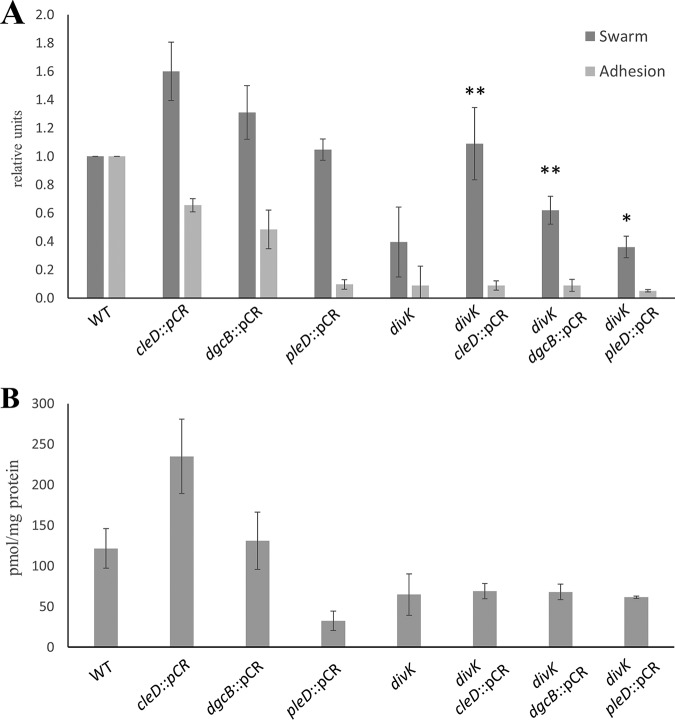

FIG 4.

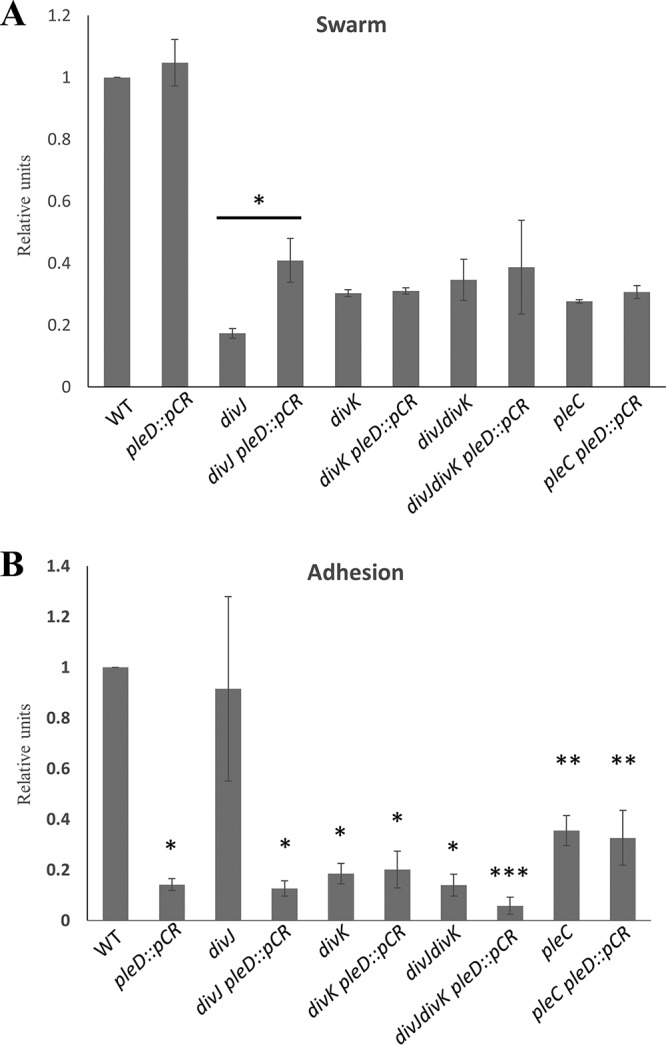

Phenotypes exhibited by divK suppressors do not coincide with intracellular c-di-GMP levels. (A) Swarm expansion and surface adhesion of suppressor mutations tested in both wild-type and divK backgrounds. Disruption of cleD and dgcB increased motility in the wild-type and divK backgrounds. Disruptions in the wild-type background lead to various levels of adhesion reduction, but the same disruptions had no effect on adhesion in the divK background. *, motility is statistically insignificant compared to the divK parent; **, motility is statistically significant compared to the divK parent (P < 0.05). (B) c-di-GMP levels were measured using mass spectrometry and then normalized to the amount of biomass from each sample. Despite disruptions causing increased motility in the wild-type background, these strains had different c-di-GMP levels. No disruption changed c-di-GMP levels in the divK background, even though some strains suppressed the motility defect while others did not. These results show a discrepancy between phenotypic effects and intracellular c-di-GMP levels.

Bresu_2169 is the homolog of the well-characterized C. crescentus diguanylate cyclase, DgcB (61% identical amino acid sequence). In C. crescentus, DgcB is one of two major diguanylate cyclases that work in conjunction to elevate c-di-GMP levels, which in turn help regulate the cell cycle, specifically in regard to polar morphogenesis (29). It has been shown that a dgcB mutant causes adhesion to drop to nearly 50% compared to the wild type, while motility was elevated to almost 150%. It was unsurprising to find very similar changes in phenotypes in the dgcB mutant in wild-type B. subvibrioides. In the dgcB mutant, swarm expansion increased by 124%, while adhesion dropped to only 46% compared to the wild type (Fig. 4A). Although the dgcB mutant did not restore motility to wild-type levels in the divK background, the insertion did cause the swarm to expand nearly twice as much as that of the divK parent. These phenotypes are consistent with our current understanding of c-di-GMP’s role in the C. crescentus cell cycle. As c-di-GMP builds up in the cell, it begins to make the switch from its motile phase to its sessile phase. Deleting a diguanylate cyclase should therefore prolong the swarmer cell stage, thereby increasing motility and decreasing adhesion. Similar to cleD, dgcB disruption had no impact on the phage sensitivity phenotypes of the wild-type or divK-derived strains (Fig. S5).

A pleD mutant lacks hypermotility in a divK background.

Given the identification of dgcB in the suppressor screen, it was of note that the screen did not identify the other well-characterized diguanylate cyclase involved in the C. crescentus cell cycle, PleD. PleD is an atypical response regulator with two receiver domains in addition to the diguanylate cyclase domain (30, 31). The pleD mutant in C. crescentus has been shown to suppresses the pleC motility defect in C. crescentus, which led to its initial discovery alongside divK (30–32). However, in a wild-type background, pleD disruption has actually been shown to reduce motility to about 60% compared to the wild type (29, 32). In addition, a 70% reduction in adhesion is observed in pleD mutants, which is thought to be a result of delayed holdfast production (29, 32, 33). Therefore, it was not clear whether a pleD disruption would lead to motility defect suppression in a divK background. To examine this, a pleD disruption was made in both wild-type and divK B. subvibrioides strains (Fig. 4A). The divK and pleD genes belong to the same two gene operon, where divK is the first gene. As previously published, deletion of divK was performed using an in-frame deletion and thus is not expected to impact pleD expression. Since pleD is the latter of the two genes, plasmid insertion into pleD is not expected to impact divK expression.

In wild-type B. subvibrioides, pleD disruption resulted in little change to motility, with swarms expanding to 105% of the wild type, whereas adhesion dropped to only 10% compared to the wild type. While these data support the broader theory of c-di-GMP’s role as the “switch” between the motile and sessile phases of the cell cycle, it does not align with the phenotypes seen in a C. crescentus pleD mutant. While adhesion is reduced in both organisms, the reduction in adhesion was much more drastic in B. subvibrioides than in C. crescentus. Moreover, the motility phenotypes in homologous pleD mutants do not match. In C. crescentus, pleD mutants cause a decrease in motility by nearly 40% in the wild-type background (29, 32). In B. subvibrioides, motility is the same as for the wild type (Fig. 4A). Disruption of pleD also causes a reduction in phage sensitivity (see Fig. 7B; see also Fig. S5 in the supplemental material).

Another interesting detail discovered in performing these assays was the lack of change in phenotypes seen in the pleD disruption in a divK background. It is not surprising that adhesion was not negatively impacted since it is already significantly lower in the divK strain compared to the wild type. However, disrupting the pleD gene did not increase motility in the divK mutant. In fact, motility was reduced to 89% compared to the divK control (Fig. 4A). In addition, both divK and pleD mutants had the same reduction in phage sensitivity as the divK pleD double mutant (see Fig. 7B; see also Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). It is not clear why disruption of the diguanylate cyclase DgcB leads to increased motility in both wild-type and divK backgrounds, but disruption of another diguanylate cycle PleD does not increase motility in either background. Interestingly, it was previously shown that DivJ and PleC do not act on DivK alone but in fact also have the same enzymatic functions on PleD phosphorylation as well (34). It may be that PleD acts upon motility not through c-di-GMP signaling but instead by modulating DivK activity, perhaps by interacting/interfering with the polar kinases. If so, then the absence of DivK could block this effect.

Suppressor mutants have altered c-di-GMP levels.

Since these mutations are all involved in c-di-GMP signaling, the c-di-GMP levels in each strain were quantified to determine whether the cellular levels in each strain correspond to observed phenotypes. These metabolites were quantified from whole-cell lysates. In bacteria, high c-di-GMP levels typically induce adhesion, while low c-di-GMP levels induce motility. Therefore, it would be expected that hypermotile strains would show decreased c-di-GMP levels. Instead, hypermotile strains of the wild-type background had various c-di-GMP levels (Fig. 4B). The pleD knockout had reduced c-di-GMP levels as predicted. Although it may seem surprising that c-di-GMP levels are not affected in a dgcB mutant, this in fact true of the C. crescentus mutant as well (29). This result suggests that the c-di-GMP levels found in the dgcB strain do not appear to be the cause for the observed changes in motility and adhesion. A comparison of c-di-GMP levels and phenotypic analyses between the organisms is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of changes in c-di-GMP levels and phenotypes between C. crescentus and B. subvibrioides strains

| Mutation | Organism | Phenotypea |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-di-GMP (%) | Adhesion | Motility | Source or reference | ||

| cleD | C. crescentus | ND | +/–b | ++ | 26 |

| B. subvibrioides | ++ (193) | +/– | ++ | This study | |

| dgcB | C. crescentus | + (∼105) | +/– | ++ | 29 |

| B. subvibrioides | + (108) | +/– | ++ | This study | |

| pleD | C. crescentus | +/– (∼70) | +/– | +/– | 29 |

| B. subvibrioides | – (27) | +/– | + | This study | |

++, above wild-type levels; +, wild-type or nearly wild-type levels; +/–, below wild-type or intermediate levels; –, null or nearly null levels; ND, not determined.

Adhesion of individual cells was measured in microfluidic devices.

Perhaps the most interesting result is that the cleD mutant had the highest c-di-GMP levels of all of the strains tested. This is surprising since it is suggested by Nesper et al. that CleD does not affect c-di-GMP levels at all but rather is affected by them. CleD is a response regulator that contains neither a GGDEF nor an EAL domain characteristic of diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases, respectively. Instead it is thought CleD binds to c-di-GMP, which then stimulates it to interact with the flagellar motor. The data presented here suggest that there may be a feedback loop whereby increased motility in the swarm agar leads to increased c-di-GMP levels. One potential explanation is that this situation increases contact with surfaces. Yet the cleD mutant clearly shows decreased adhesion compared to the wild type despite the elevated c-di-GMP levels. Therefore, there must be a block between the high c-di-GMP levels and the execution of those levels into adhesion in this strain.

Very different results were obtained when c-di-GMP levels were measured in divK-derived strains (Fig. 4B). While a wide variety of motility phenotypes were observed in cleD, dgcB, and pleD disruptions in the divK background, their c-di-GMP levels are all nearly identical to that of the divK mutant. For the dgcB divK strain, once again the increase in motility occurs without a change in c-di-GMP levels. These results suggest that DgcB is not a significant contributor to c-di-GMP production in B. subvibrioides. While pleD disruption leads to decreased c-di-GMP levels in the wild-type background, no change is seen in the divK background. This means that in the absence of PleD some other enzyme must be responsible for achieving these levels of c-di-GMP. Given the lack of impact DgcB seems to have on c-di-GMP signaling, it is tempting to speculate that an as-yet-uncharacterized diguanylate cyclase is involved. Lastly the elevated c-di-GMP levels seen in the cleD disruption are not seen when cleD is disrupted in the divK background. This result suggests that whatever feedback mechanism leads to elevated c-di-GMP levels is not functional in the divK mutant.

Nonnative diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases cause shifts in c-di-GMP levels but do not alter phenotypes in the divK strain.

As previously mentioned, c-di-GMP is thought to assist in the coordination of certain developmental processes throughout the cell cycle. The previous results found that mutations in genes involved in c-di-GMP signaling could suppress developmental defects, but the actual effect of the mutations appears to be uncoupled from effects on c-di-GMP levels. In order to further investigate the connection between developmental defects and c-di-GMP signaling, c-di-GMP levels were artificially manipulated. Plasmid constructs expressing nonnative c-di-GMP metabolizing enzymes previously used in similar experiments in C. crescentus were obtained and expressed in B. subvibrioides. The diguanylate cyclase ydeH from Escherichia coli was expressed from two different IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-inducible plasmids: the medium-copy-number pBBR-based plasmid pTB4 and the low-copy-number pRK2-based plasmid pSA280 (32). The combination of the two different inducible copy number plasmids resulted in different elevated levels of c-di-GMP (Fig. 5B). Phosphodiesterase gene pchP from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (35) and its active-site pchPE328A mutant were expressed from pBV-MCS4, a vanillate-inducible medium-copy-number plasmid (36). The phosphodiesterase gene on a medium-copy-number plasmid was enough to decrease levels of c-di-GMP to those either equivalent to or lower than levels seen in the divK strain. The decrease was not observed when the active-site mutant was expressed, demonstrating that the reduction of c-di-GMP was the result of pchP expression. Wild-type and divK strains were grown with IPTG and vanillate, respectively, to control for any growth effects caused by the inducers.

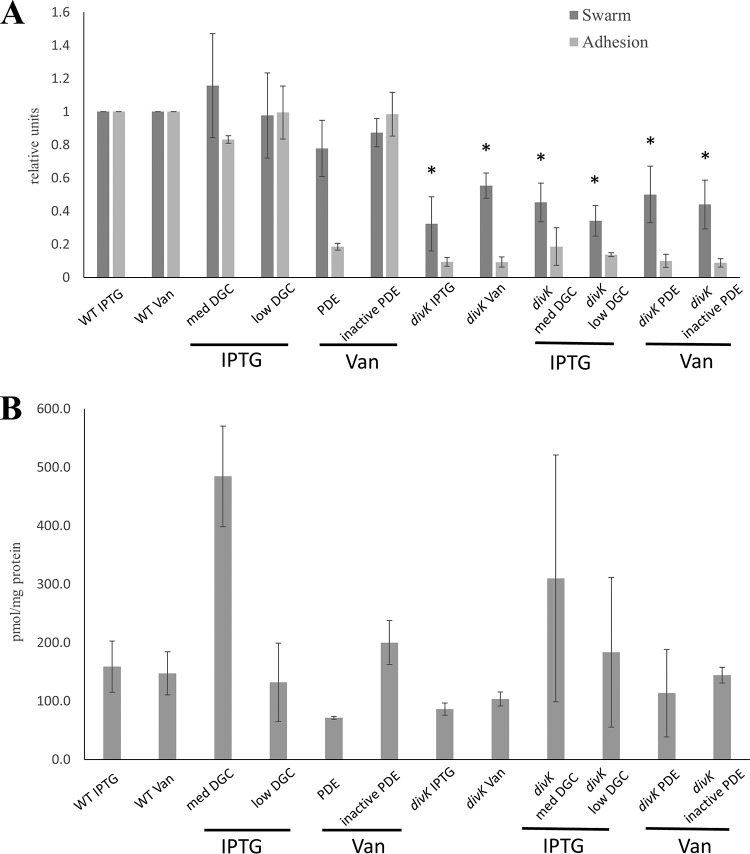

FIG 5.

Artificial manipulation of c-di-GMP levels do not significantly affect phenotypes in the divK mutant. (A) Swarm expansion and surface adhesion of strains that have altered c-di-GMP levels caused by expression of nonnative enzymes in wild-type and divK mutant backgrounds. Constructs, including the E. coli diguanylate cyclase gene ydeH expressed from a medium-copy-number plasmid (med DGC) and a low-copy-number plasmid (low DGC) and the P. aeruginosa phosphodiesterase gene pchP (PDE), as well as a catalytically inactive variant (inactive PDE), were utilized. Bars below the x axis outline inducer used for plasmids in each strain. In the wild-type background, the medium-copy-number DGC increased motility and decreased adhesion, which is opposite the expected outcome, whereas the PDE reduced motility and severely reduced adhesion. In the divK background, no expression construct significantly altered the phenotypes. *, motility and adhesion were statistically insignificant from the control strain (P > 0.05). (B) c-di-GMP levels were measured using mass spectrometry and then normalized to the amount of biomass from each sample. In the wild-type background, the medium-copy-number DGC significantly increased c-di-GMP levels, whereas the PDE reduced c-di-GMP levels. In the divK background, both DGC constructs increased c-di-GMP levels, although PDE expression has no effect, despite the fact that neither DGC construct has an effect on motility and adhesion phenotypes.

Expression of the phosphodiesterase in the wild-type background caused a reduction in c-di-GMP, which would be predicted to increase motility and decrease adhesion. While this strain had a large reduction of adhesion, it also had a small reduction in motility (Fig. 5A). However, these same results were obtained when this construct was expressed in wild-type C. crescentus (32). It is interesting to note, however, that expression of the phosphodiesterase results in c-di-GMP levels similar to those of the divK strain, and yet the phosphodiesterase strain demonstrates much larger swarm sizes than the divK strain. The low-copy-number diguanylate cyclase plasmid did not appear to affect c-di-GMP levels (Fig. 5B) and, unsurprisingly, did not appear to affect either motility or adhesion. However, the medium-copy-number diguanylate cyclase plasmid increased c-di-GMP levels but had surprising phenotypic results. An increase in c-di-GMP levels would be predicted to increase adhesion and decrease motility. When this construct was expressed in wild-type C. crescentus, there was a small decrease in adhesion but a very large decrease in motility, almost to the point of nonmotility (32); the motility results mirror the prediction based on the c-di-GMP levels. In B. subvibrioides the same construct produced a slight decrease in adhesion, but motility actually increased instead of drastically decreasing. Here, the B. subvibrioides results not only differ from C. crescentus results but also contradict predictions based on known c-di-GMP paradigms.

In the divK background strain, expression of either diguanylate cyclase increases c-di-GMP levels, although the low-copy-number diguanylate cyclase increase is not as dramatic as that of the medium-copy-number diguanylate cyclase. However, neither expression level has a significant impact on motility or adhesion (Fig. 5). Neither the phosphodiesterase nor its active-site mutant causes a noticeable shift in the c-di-GMP levels compared to the divK strain nor has any noticeable impact on phenotype. In fact, though the c-di-GMP levels differed dramatically between strains, the phenotypes of all six of these strains are not impacted. t tests performed between each strain and its respective control showed no significant differences. These results appear to be the antithesis of those found from the suppressor screen. While the suppressor mutants showed recovery in their motility defect compared to the divK strain, their c-di-GMP levels did not significantly differ from each other or divK strain. Conversely, when c-di-GMP levels were artificially manipulated, alterations of the c-di-GMP levels in the divK strain had no impact on phenotypes. These results suggest that DivK is somehow serving as a block or a buffer to c-di-GMP levels and their effects on phenotypes and calls into question the role c-di-GMP has in B. subvibrioides developmental progression.

Disruption of pleD in developmental signaling mutants does not alter pleC phenotypes but does alter divJ phenotypes.

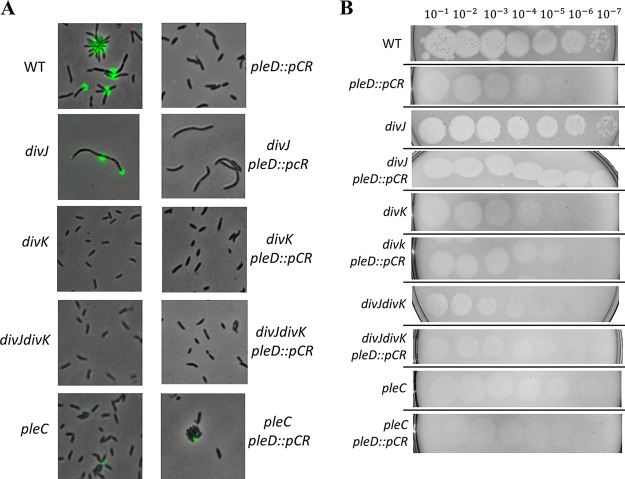

As discussed above, disruption of pleD does not impact the adhesion or swarm expansion phenotypes of a divK mutant. To determine the epistatic relationship between pleD and other developmental signaling mutants of B. subvibrioides, the pleD disruption was placed in the divJ, divJ divK, and pleC strains, and resultant mutants were analyzed for developmental defects (Fig. 6 and 7). Disruption of pleD does not alter the phenotypes of the divK or divJ divK strains in swarm expansion, adhesion, holdfast formation, or phage sensitivity. The exception to this is the divJ divK pleD::pCR strain, which had a small but statistically significant reduction in adhesion compared to the divJ divK parent (P = 0.03). These results are to be expected given previous results and the fact that the divJ divK strain has consistently phenocopied the divK strain. What was not expected was that disruption of pleD had no effect on pleC strain phenotypes. The pleD gene was originally discovered as a motility suppressor of the C. crescentus pleC mutant (13), but in B. subvibrioides pleD disruption does not alter any of the developmental phenotypes of the pleC strain. Instead, pleD disruption alters some, but not all, of the divJ mutant phenotypes. The divJ pleD::pCR strain had wild-type levels of phage sensitivity just like the divJ parent, and microscopic examination of the strain also revealed that the strain had a filamentous cell morphology characteristic of the divJ parent strain (Fig. 7A). However, this strain had a significant reduction in adhesion, holdfast was undetectable, and there was a small but statistically significant increase in motility. Essentially, pleD disruption removes holdfast formation and increases motility without affecting cell filamentation or pilus production, although swarm expansion results are clouded by the filamentous cell morphology, which impacts swarm expansion independent of flagellum function or chemotaxis. These divJ pleD::pCR results stand in stark contrast to the divJ divK results, where all developmental phenotypes copy the divK phenotypes. Perhaps this suggests that PleD may have a more specific role in the morphological changes that occur during B. subvibrioides cell cycle progression.

FIG 6.

Disruption of pleD does not alter pleC or divK motility or adhesion but does alter divJ motility and adhesion. Wild-type, pleD, divJ, divJ pleD, divK, divK pleD, pleC, and pleC pleD B. subvibrioides strains were analyzed for swarm expansion (A) and adhesion (B) defects using a soft agar swarm assay and a short-term adhesion assay, respectively. Mutant strains were normalized to wild-type results for both assays. The pleD mutation has no effect on the adhesion or motility of the pleC or divK strains but does reduce adhesion and increase motility of the divJ strain. In panel A, the bar with an asterisk indicates that divJ pleD::pCR has statistically significantly more swarm expansion than does the divJ strain (P < 0.05). In panel B, results with the same number of asterisks are not statistically significantly different from each other but are statistically significant compared to results with a different number of asterisks (P < 0.05).

FIG 7.

Disruption of pleD does not alter pleC or divK holdfast production or phage sensitivity but does alter divJ holdfast production. (A) Lectin staining of holdfast material of wild-type, pleD, divJ, divJ pleD, divK, divK pleD, pleC, and pleC pleD B. subvibrioides strains. Wild-type and divJ strains have easily detectable holdfast material. pleC and pleC pleD strains have greatly reduced but still detectable holdfast material, while all remaining strains have no detectable holdfast. This includes the divJ pleD strain, which still displays obvious cell filamentation though no longer producing holdfast. (B) B. subvibrioides wild-type, pleD, divJ, divJ pleD, divK, divK pleD, pleC, and pleC pleD strains were tested with phage Delta in soft agar phage assays. While the pleD disruption alters the adhesion and holdfast phenotypes of the divJ strain, this mutation does not alter the phage sensitivity of the parent, since both divJ and divJ pleD strains have sensitivities to the phage similar to that of the wild type.

DISCUSSION

Across closely related bacterial species, high levels of gene conservation are commonly observed. It has therefore been a long-standing assumption that information gathered from studying a model organism can be extrapolated to other closely related organisms. Through this study, by comparing and contrasting the developmental signaling systems of C. crescentus and B. subvibrioides, it has been shown that these assumptions may not be as safe to make as previously thought. Preliminary data raised a few questions by demonstrating major differences in the phenotypes of divK mutants between species. Here, the system was analyzed in greater depth in B. subvibrioides by examining subcellular protein localization, developmental phenotypes of a pleC mutant, and isolating a pilitropic bacteriophage to examine pilus production in multiple developmental mutants. GFP tagging revealed that the subcellular localization patterns of DivJ and PleC in B. subvibrioides are consistent with the C. crescentus proteins. DivJ was consistently detected at the holdfast (i.e., stalked) pole, while PleC was consistently detected at the nonholdfast (i.e., flagellar) pole. DivK was found in a variety of localization patterns. In C. crescentus, DivK is localized to the stalked pole in stalked cells, bipolarly localized in predivisional cells, and delocalized in swarmer cells. In B. subvibrioides, stalked pole and bipolar localizations were observed, but the majority of cells displayed delocalized DivK-GFP. If B. subvibrioides adhered to the C. crescentus model, this would suggest that >85% of the B. subvibrioides population in a growing culture are swarmer cells. Many of the cells with delocalized DivK were in rosettes and/or had detectable holdfast (Fig. S4 and additional data not shown). Correlated to this is the fact that 82.9% of cells had no detectable DivJ-GFP foci, whereas only 28.9% lacked detectable PleC-GFP foci; the presence of PleC and the absence of DivJ would theoretically lead to complete dephosphorylation of DivK, which causes delocalization in C. crescentus, such as in swarmer cells (37). This suggests that many, if not most, B. subvibrioides stalked cells have delocalized DivK. One unusual facet of B. subvibrioides physiology is the fact that the doubling time of this organism in peptone-yeast extract medium (PYE) is 6.5 h (3) compared to the 1.5 h of C. crescentus in the same medium. It is not clear how the cell cycle is adjusted to account for this longer generation time. Perhaps the B. subvibrioides signaling system is held in a more swarmer cell-like state even though the cells are morphologically more like a stalked cell. However, stalked pole localization is observed, so what induces the transition from delocalized to localized? More careful dissection of the B. subvibrioides cell cycle, with particular respect to signaling protein localization, may reveal the answer.

While the discovery that developmental protein localization in B. subvibrioides largely matches the localization in C. crescentus may not be surprising, this discovery makes the phenotypic results even more surprising (summarized in Table 2). Previously, it was shown that the B. subvibrioides divJ mutant closely matches the phenotypes of the C. crescentus divJ mutant in regard to cell filamentation, holdfast production, adhesion, and motility (3). Here, pilus synthesis was added by the use of a novel bacteriophage and the B. subvibrioides divJ strain still mirrored the C. crescentus results. In C. crescentus divK disruption/depletion leads to G1 cell stage arrest (15), i.e., in the stalked cell stage prior to entering the predivisional stage. As a consequence, the cells become extremely filamentous and do not produce flagella or pili. Although the adhesion of this strain was never tested, cells are seen to produce stalks that touch tip to tip in the rosette fashion, suggesting holdfast production. These phenotypes are similar to divJ phenotypes, which makes sense given that both mutations ultimately lead to lower levels of DivK∼P. Conversely, previously it was shown that B. subvibrioides divK deletion produced opposite phenotypic results in cell size, holdfast production, and adhesion. Both mutants were compromised in motility, but the mechanistic reasons are unclear, especially given that both strains produce apparently functional flagella, although the morphology defects of the divJ strain may have a bearing on these results. Here, another difference was demonstrated between the strains since the B. subvibrioides divK strain had an intermediate phage resistance phenotype. While the B. subvibrioides divJ strain largely matched the C. crescentus divJ strain and B. subvibrioides was largely opposite the C. crescentus divK strain, the B. subvibrioides pleC strain was an intermediate of the C. crescentus pleC strain. In C. crescentus pleC mutants have normal cell size, but produce no pili, produce no holdfast (and thus are adhesion deficient), and are nonmotile due to a paralyzed flagellum. Here, it was found that B. subvibrioides pleC mutants have an intermediate phage resistance phenotype, suggesting intermediate pilus production, intermediate adhesion with weak holdfast detection, and intermediate motility. Therefore, comparing signaling mutants between organisms results in the same, opposite, or intermediate results. These results are all the more confusing given the fact that the localization patterns of the proteins are mostly conserved between the organisms. It seems unlikely that the phenotypic consequences are a result of altered localization patterns. This suggests that the phenotypic consequences are a product of altered downstream signaling. Even in C. crescentus, the exact connection between signaling protein disruption and phenotypic consequence are largely unknown. Careful mapping of the signaling systems between the mutation and the eventual phenotype is required in both organisms.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of developmental mutation phenotypes between C. crescentus and B. subvibrioides

| Mutation | Organism | Phenotypea |

Source or reference(s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell size | Adhesion | Holdfast | Motility | Pili | |||

| divJ | C. crescentus | Filament | ++ | ++ | – | + | 8, 46, 47 |

| B. subvibrioides | Filament | +/++ | ++ | – | + | 3; this study | |

| divK | C. crescentusb | Filament | ND | ND | – | – | 15, 48, 49 |

| B. subvibrioides | Short | – | – | – | +/– | 3; this study | |

| pleC | C. crescentus | Normal | – | – | – | – | 12, 13, 20, 21, 36 |

| B. subvibrioides | Normal | +/– | +/– | +/– | +/– | This study | |

| pleD | C. crescentus | Normal | – | + | +/– | + | 29, 31, 33, 36, 50 |

| B. subvibrioides | Normal | – | – | + | +/– | This study | |

| dgcB | C. crescentus | Normal | +/– | + | ++ | ND | 29 |

| B. subvibrioides | Normal | +/– | + | ++ | + | This study | |

++, above wild-type levels; +, wild-type or nearly wild-type levels; +/–, below wild-type or intermediate levels; –, null or nearly null levels; ND, not determined.

Adhesion and holdfast production were not analyzed in this strain, but circumstantial evidence suggests that holdfast material is produced.

In an attempt to further map this system in B. subvibrioides, a suppressor screen was used with the divK mutant since its phenotypes differed most dramatically from its C. crescentus homolog. Suppressor mutations were found in genes predicted to encode proteins that affected or were affected by c-di-GMP. This was not necessarily a surprising discovery; c-di-GMP is a second messenger signaling system conserved across many bacterial species used to coordinate the switch between motile and sessile lifestyles. Previous research in C. crescentus suggests that organism integrated c-di-GMP signaling into the swarmer-to-stalked cell transition. Mutations that modify c-di-GMP signaling would be predicted to impact the swarmer cell stage, perhaps lengthening the amount of time the cell stays in that stage and thus leading to an increase in swarm spreading in soft agar. However, further inquiry into c-di-GMP levels of divK suppressor mutants revealed discrepancies between c-di-GMP levels and their corresponding phenotypes. First, CleD, a CheY-like response regulator that is thought to affect flagellar motor function, caused the strongest suppression of the divK mutant, restoring motility levels to that of wild type. Given that the reported function of CleD is to bind the FliM filament of the flagellar motor and interfere with motor function to boost rapid surface attachment (26), it is expected that the disruption of cleD would result in increased motility and decreased adhesion, which can be seen in both the wild-type and divK background strains (Fig. 4A). What was unexpected, however, was that a lack of CleD led to one of the highest detected levels of c-di-GMP in this study, which was surprising given that CleD has no predicted diguanylate cyclase or phosphodiesterase domains. Yet when this same mutation was placed in the divK background, the c-di-GMP levels were indistinguishable from those of the divK parent. Therefore, the same mutation leads to hypermotility in two different backgrounds despite the fact that the c-di-GMP levels are drastically different. Consequently, the phenotypic results of the mutation do not match the c-di-GMP levels, suggesting that c-di-GMP has little or no effect on the motility phenotype. A similar result was seen with DgcB. Disruption of dgcB in either the wild-type or the divK background resulted in hypermotility, but c-di-GMP levels were not altered. Once again, the effect on motility occurred independently of c-di-GMP levels. Disruption of divK seems to somehow stabilize c-di-GMP levels. Even when nonnative enzymes are expressed in the divK background, the magnitude of the changes seen in the c-di-GMP pool is dampened compared to the magnitude of changes seen when the enzymes are expressed in the wild-type background. This may explain why pleD was not found in the suppressor screen. While CleD and DgcB seem to be involved in c-di-GMP signaling, their effect on the cell appears to be c-di-GMP independent, whereas PleD appears to perform its action by affecting the c-di-GMP pool. If that pool is stabilized in the divK strain, then disruption of pleD will have no effect on either the c-di-GMP pool or the motility phenotype. However, it should be noted that c-di-GMP levels were measured from whole-cell lysates and do not reflect the possibility of spatial or temporal variations of c-di-GMP levels within the cell. It is possible that CleD and DgcB have c-di-GMP-dependent effects but that these effects are limited to specific subcellular locations in the cell.

In C. crescentus, c-di-GMP is implicated in the morphological changes that occur during swarmer cell differentiation, but c-di-GMP levels are also tied to the developmental network and, more specifically, CtrA activation by two different mechanisms. First, through most of the cell cycle the diguanylate cyclase DgcB is antagonized by the phosphodiesterase PdeA such that no c-di-GMP is produced by DgcB (29). Upon swarmer cell differentiation, PdeA is targeted for proteolysis, leaving DgcB activity unchecked. This, combined with active PleD, increases c-di-GMP levels in the cell. The elevated levels activate the protein PopA, which targets CtrA for proteolysis, which is useful for swarmer cell differentiation since it will relieve the inhibition of chromosome replication initiation performed by CtrA binding at the origin of replication. In the second mechanism, it has been found that c-di-GMP is an allosteric regulator of CckA, the hybrid histidine kinase responsible for phosphorylation of CtrA (38). As stated above, DivJ and PleC have the same antagonistic phosphorylation activities on PleD as they do on DivK, and phosphorylation induces PleD activity. During swarmer cell differentiation, isolated PleC is replaced at the transitioning stalked pole by DivJ, which leads to elevated PleD phosphorylation and therefore higher enzymatic activity. This, combined with unchecked DgcB activity, increases c-di-GMP levels, which has been shown to inhibit kinase activity and stimulate the phosphatase activity of CckA, causing CtrA to be dephosphorylated and therefore deactivated. In addition, the same CckA phosphatase activity causes the dephosphorylation of CpdR, which also targets CtrA for proteolysis. It has also been shown that CpdR activity targets PdeA for degradation, thereby permitting unchecked DgcB activity. Therefore, the elevation of c-di-GMP levels during swarmer cell differentiation works redundantly to deactivate CtrA, which is necessary for cell cycle progression, and serves to coordinate the morphological changes of swarmer cell differentiation with the necessary changes in the signaling state of the developmental network.

However, these models do not adequately explain some of the more unusual results reported in this study. First, it is not clear why c-di-GMP levels appear stabilized in a divK mutant in B. subvibrioides. In C. crescentus DivK has been shown to be an allosteric effector of PleC, where nonphosphorylated DivK stimulates PleC to become a kinase and increase PleD∼P levels (39), though it is thought this activity only occurs during the onset of swarmer cell differentiation. If one were to assume that DivK-driven PleC phosphorylation of PleD were the sole mechanism of PleD phosphorylation, then theoretically the absence of DivK could mean that PleD is never phosphorylated and therefore c-di-GMP levels would not change above background in a divK strain, but this would mean that (i) the observed DivJ kinase activity on PleD is unimportant to PleD activity and thus only the phosphorylation of PleD by PleC (at the onset or swarmer cell differentiation) is important and (ii) PleD is the sole contributor to c-di-GMP elevation and thus DgcB activity is not a meaningful contributor to measurable c-di-GMP changes. Perhaps this second point is supported by our data here, which show a disconnect between phenotype and c-di-GMP levels in dgcB mutants, and it was seen both here in B. subvibrioides and in C. crescentus that the overall c-di-GMP levels do not change much in dgcB mutants (29). These models also do not explain why pleD disruption alters the adhesion phenotypes of a divJ mutant. Assuming that DivJ is the PleD kinase, then PleD should be inactive in a divJ strain, and disrupting pleD in a divJ background should therefore have no effect. In this study, however, it clearly does. Perhaps this result supports a hypothesis that only PleC phosphorylation of PleD is biologically relevant. In addition, assuming another PleD kinase is active in a divJ strain, the results of pleD disruption should be redundant to divJ deletion and not counterproductive. A divJ deletion should lead to decreased levels of DivK∼P, which should allow promiscuous interaction between DivL and CckA, ultimately leading to overactivation of CtrA. Disruption of pleD should lead to decreased c-di-GMP levels (which was seen in this study), which would not direct CckA into its phosphatase role, and also potentially lead to overactivation of CtrA. Therefore, combining divJ and pleD mutations should be redundant, if not additive. Yet in this study it was seen that pleD disruption reversed the holdfast formation and motility of the divJ strain. Furthermore, pleD disruption did not alter the cell filamentation or pilus production of the divJ strain, which may suggest that PleD’s role in cell cycle progression is specific to holdfast and/or motility and argues against a role in CtrA regulation.

This research raises several questions. First, what is the exact role of c-di-GMP in cell cycle progression of B. subvibrioides? Is this signal a major driver of the swarmer cell and swarmer cell differentiation? Or have the various c-di-GMP signaling components found new roles in the swarmer cell and the actual c-di-GMP is simply vestigial. What is the role of PleD in cell cycle progression? Why are c-di-GMP levels so stable when DivK is removed? Finally, are the answers to these questions specific to B. subvibrioides, or can they be extrapolated back to C. crescentus? Further investigation into c-di-GMP signaling in both organisms is required.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

A complete list of strains used in this study is presented in the appendix (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Brevundimonas strains were cultured at 30°C on PYE medium (2 g peptone, 1 g yeast extract, 0.3 g MgSO4⋅7H2O, 0.735 CaCl2) (40). Kanamycin was used at 20 μg/ml, gentamicin at 5 μg/ml, and tetracycline at 2 μg/ml when necessary. PYE plates containing 3% sucrose were used for counterselection. Escherichia coli was cultured on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (10 g/liter tryptone, 10 g/liter NaCl, and 5 g/liter yeast extract) at 37°C. Kanamycin was used at 50 μg/ml, gentamicin at 20 μg/ml, and tetracycline at 12 μg/ml when necessary.

Mutant generation.

The B. subvibrioides divJ, divK, and divJ divK mutants were used from a previous study (3). The B. subvibrioides pleC construct was made by PCR amplifying an upstream fragment of ∼650 bp using the primers PleC138Fwd (ATTGAAGCCGGCTGGCGCCACCAGATCGAAAAGGTGCAGCCC) and PleCdwRev (TCTAGGCCGCGCCCCGCAAGGCGCTCTC) and a downstream fragment of ∼550 bp using the primers PleCupFwd (CTTGCGGGGCGCGGCCTAGAGCCGGTCA) and PleC138Rev (CGTCACGGCCGAAGCTAGCGGGTGCTGGGATGAAGACACG). The primers were designed using the NEBuilder for Gibson Assembly tool online (New England Biolabs) and were constructed to be used with the pNPTS138 vector (M. R. K. Alley, unpublished data). After a digestion of the vector using HindIII and EcoRI, the vector, along with both fragments, was added to a Gibson Assembly master mix (New England Biolabs) and allowed to incubate for an hour at 50°C. Reactions were then transformed into E. coli, and correct plasmid construction was verified by sequencing to create plasmid pLAS1. This plasmid was used to delete pleC in B. subvibrioides, as previously described (3).

To create insertional mutations in genes, internal fragments from each gene were PCR amplified. A fragment from gene cpaF was amplified using the primers cpaFF (GCGAACAGAGCGACTACTACCACG) and cpaFR (CCACCAGGTTCTTCATCGTCAGC). A fragment from gene pleD was amplified using the primers PleDF (CCGGCATGGACGGGTTC) and PleDR (CGTTGACGCCCAGTTCCAG). A fragment from gene dgcB was amplified using the primers DgcBF (GAGATGCTGGCGGCTGAATA) and DgcBR (CGAACTCTTCGCCACCGTAG). A fragment from gene cleD was amplified using the primers Bresu1276F (ATCGCCGATCCGAACATGG) and Bresu1276R (TTCTCGACCCGCTTGAACAG). The fragments were then cloned into the pCR vector using a Zero Blunt cloning kit (Thermo Fisher), creating plasmids pPDC17 (cpaF), pLAS2 (pleD), pLAS3 (dgcB), and pLAS4 (cleD). These plasmids were then transformed into B. subvibrioides strains as previously published (3). The pCR plasmid is a nonreplicating plasmid in B. subvibrioides that facilitates insertion of the vector into the gene of interest via recombination, thereby disrupting the gene.

To create a C-terminal B. subvibrioides DivJ fusion, ∼50% of the divJ gene covering the 3′ end was amplified by PCR using the primers BSdivJgfpF (CCTCATATGGGTTTACGGGGCCTACGGG) and BSdivJgfpR (CGAGAATTCGAGACGGTCGGCGACGGTCCTG) and cloned into the pGFPC-2 plasmid (41), creating plasmid pPDC11. To create a C-terminal B. subvibrioides PleC fusion, ∼50% of the pleC gene covering the 3′ end was amplified by PCR using the primers BSpleCgfpF (CAACATATGCCAGAAGGACGAGCTGAACCGC) and BSpleCgfpR (TTTGAATTCGAGGCCGCCCGCGCCTGTTGTTG) and cloned into the pGFPC-2 plasmid, creating plasmid pPDC8. These plasmids are nonreplicative in B. subvibrioides and therefore integrate into the chromosome by homologous recombination at the site of each targeted gene. The resulting integration creates a full copy of the gene under the control of the native promoter that produces a protein with C-terminal GFP tag and an ∼50% 5′ truncated copy with no promoter. This effectively creates a strain where the tagged gene is the only functional copy.

Due to the small size of the divK gene, a region including the divK gene and ∼500 bp of sequence upstream of divK was amplified using the primers BSdivKgfpF (AGGCATATGCCAGCGACAGGGTCTGCACC) and BSdivKgfpR (CGGGAATTCGATCCCGCCAGTACCGGAACGC) and cloned into pGFPC-2, creating plasmid pPDC27. After homologous recombination into the B. subvibrioides genome, two copies of the divK gene are produced, both under the control of the native promoter, one of which encodes a protein C-terminally fused to GFP.

Constructs expressing E. coli ydeH under IPTG induction on medium-copy-number (pTB4) and low-copy-number (pSA280) plasmids were originally published elsewhere (32). Constructs expressing Pseudomonas aeruginosa pchP under vanillate induction (pBV-5295), as well as an active-site mutant (pBV-5295E328A), were originally reported by Duerig et al. (36).

Transposon mutagenesis.

Transposon mutagenesis was performed on the B. subvibrioides divK mutant using the EZ-Tn5 <KAN-2> TNP transposome (Epicentre). B. subvibrioides divK was grown overnight in PYE to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of about 0.07 (quantified with a Thermo NanoDrop 2000 [Thermo Scientific]). Cells (1.5 ml) were centrifuged 15,000 × g for 3 min at room temperature. The cell pellet was then resuspended in 1 ml of water before being centrifuged again. This process was repeated. Cells were resuspended in 50 μl of nuclease-free water, to which 0.2 μl of transposome was added. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The mixture was added to a GenePulser cuvette with a 0.1-cm electrode gap (Bio-Rad). The cells were then electroporated as performed previously (3). Electroporation was performed using a GenePulser Xcell (Bio-Rad) at a voltage of 1,500 V, a capacitance of 25 μF, and a resistance of 400 Ω. After electroporation, the cells were resuspended with 1 ml of PYE and then incubated with shaking at 30°C for 3 h. The cells were diluted 3-fold and then spread on PYE-Kan plates (100 μl/plate). The plates were incubated at 30°C for 5 to 6 days.

Swarm assay.

Strains were grown overnight in PYE, diluted to an OD600 of 0.02, and allowed to grow for two doublings (to an OD600 of ca. 0.06 to 0.07). All strains were diluted to an OD600 of 0.03, and 1 μl of culture was injected into a 0.3% agar PYE plate. IPTG (final concentration, 1.5 mM) and vanillate (final concentration, 1 mM) were added to a plate mixture before pouring plates, where applicable. Molten 0.3% agar in PYE (25 ml) was poured into each plate. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 5 days. Plates were imaged using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP imaging system with Image Lab software. The swarm size was then quantified in pixels using ImageJ software. All swarm sizes on a plate were normalized to the wild-type swarm on that plate. Assays were performed in triplicate, and averages and standard deviations were calculated.

Short-term adhesion assay.

Strains were grown overnight in PYE, diluted to an OD600 of 0.02, and allowed to grow for two doublings (to OD600 of ca. 0.06 to 0.07). All strains were diluted to an OD600 of 0.05, and then 0.5 ml of each strain was inoculated into a well of a 24-well dish, followed by incubation at 30°C for 2 h in triplicate. The cell culture was removed, and wells were washed three times with 0.5 ml of fresh PYE. To each well was added 0.5 ml of 0.1% crystal violet, followed by incubation at room temperature for 20 min. Crystal violet was removed from each well before the plate was washed by dunking in a tub of deionized water. Crystal violet bound to biomass was eluted with 0.5 ml of acetic acid, and the A589 was quantified using a Thermo NanoDrop 2000. Averages for each strain were calculated and then normalized to wild-type values inoculated into the same plate. These assays were performed three times for each strain, and the results were used to calculate averages and standard deviations.

Lectin-binding assay and microscopy conditions.

Holdfast staining was based on a previously published protocol (42). Strains of interest were grown overnight in PYE to an OD600 of 0.05 to 0.07. For each strain, 200 μl of culture was incubated in a centrifuge tube with 2 μl of Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes) for 20 min at room temperature. The cells were washed with 1 ml of sterile water and then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 1 min at room temperature. The cell pellet was resuspended in 30 μl of sterile water. A 1% agarose pad (agarose in H2O) was prepared for each strain on a glass slide, to which 1 μl of culture was added. The slides were then examined and photographed with an Olympus IX81 microscope by phase-contrast and epifluorescence microscopy using a 100× Plan APO oil immersion objective. The holdfasts of GFP-labeled strains were stained with Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated to wheat germ agglutinin and prepared for imaging as described above. Alexa Fluor 488- and GFP-labeled strains were imaged with 470/20-nm excitation and 525/50-nm emission wavelengths. Alexa Fluor 594-labeled strains were imaged with 572/35-nm excitation and 635/60-nm emission.

Isolation of phage.

Surface water samples from freshwater bodies were collected from several sources in Lafayette County, Mississippi, in 50-ml sterile centrifuge tubes and kept refrigerated. Samples were passed through 0.45-μm filters to remove debris and bacterial constituents. To isolate phage, 100 μl of filtered water was mixed with 200 μl of midexponential B. subvibrioides cells and added to 2.5 ml of PYE with molten 0.5% agar. The solution was poured onto PYE agar plates, allowed to harden, and then incubated at room temperature (∼22°C) for 2 days. Plaques were excised with a sterile laboratory spatula and placed into sterile 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes. A portion (500 μl) of PYE was added, and the sample was refrigerated overnight to extract phage particles from the agar. To build a more concentrated phage stock, the soft agar plating was repeated with extracted particles. Instead of excising plaques, 5 ml of PYE was added to the top of the plate, followed by refrigeration overnight. The PYE/phage solution was collected and stored in a foil-wrapped sterile glass vial, and 50 μl of chloroform was added to kill residual bacterial cells. Phage solutions were stored at 4°C.

Isolation of phage-resistant mutants.

B. subvibrioides was mutagenized with EZ-Tn5 transposome as described above. After electroporation, the cells were grown for 3 h without selection, followed by 3 h with kanamycin selection. Transformed cells (100 μl) were mixed with 100 μl of phage stock (∼1 × 1010 PFU/ml) and plated on PYE agar medium with kanamycin. Colonies arose after ∼5 days and were transferred to fresh plates. Transformants had their genomic DNA extracted by using a Bactozol kit (Molecular Research Center). Identification of the transposon insertion sites was performed using Touchdown PCR (43), with the transposon-specific primers provided in the EZ-Tn5 kit.

Phage sensitivity assays.

Two different phage sensitivity assays were used. First (here referred to as the spotting assay) involved the mixing of cells and phage in liquid suspension and then spotting droplets on an agar surface. Each cell culture was normalized to an OD600 of 0.03. The culture was then diluted 10−2, 10−4, and 10−5 in PYE medium. For control assays, 5 μl of each cell suspension (including undiluted) was mixed with 5 μl of PYE, and then 5 μl of this mixture was spotted onto PYE plates, allowed to dry, and incubated at room temperature for 2 days. For the phage sensitivity assays, 5 μl of each cell suspension was mixed with 5 μl of phage stock (∼1 × 1010 PFU/ml), and 5 μl was spotted onto PYE plates, allowed to dry, and incubated at room temperature for 2 days.

The second assay (here referred to as the soft agar assay) involved creating a lawn of cells and spotting dilutions of phage on the lawn. Cell cultures were normalized to an OD600 of 0.03, and 200-μl portions of cells were mixed with 4.5 ml of PYE with molten 0.5% agar, mixed, poured onto a PYE agar plate, and allowed to harden. Phage stock (∼1 × 1010 PFU/ml) was diluted in PYE medium as individual 10× dilutions to a total of 10−7 dilution. Then, 5 μl of each phage concentration (10−1 to 10−7, seven concentrations in all) were spotted onto the top of the soft agar surface and allowed to dry. The plates were incubated for 2 days at room temperature.

Swarm suppressor screen.

Individual colonies from a transposon mutagenesis were collected on the tip of a thin sterile stick and inoculated into a 0.3% agar PYE plate. Wild-type B. subvibrioides strains, as well as the B. subvibrioides divK strain, were inoculated into each plate as controls. A total of 32 colonies were inoculated into each plate, including the two controls. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 5 days. The plates were then examined for strains that had expanded noticeably further than the parent divK strain from the inoculation point. The strains of interest were then isolated for further testing.

Identification of swarm suppressor insertion sites.