Here we show that the conserved RNA chaperone Hfq is important for the growth of the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. We found that the growth defect of hfq mutant cells is dependent upon the expression of genes that are under the control of the transcription regulator MexT. These include a gene that we refer to as hilR, which we show is negatively regulated by Hfq and encodes a small protein that can be toxic when ectopically produced in wild-type cells. Thus, Hfq can influence the growth of P. aeruginosa by limiting the toxic effects of MexT-regulated genes, including one encoding a previously unrecognized small protein. We also show that MexT activity depends on an enzyme that synthesizes glutathione.

KEYWORDS: chromatin immunoprecipitation, glutathione, MexT, RNA binding proteins, transcription factors, transposon mutagenesis

ABSTRACT

Hfq is an RNA chaperone that serves as a master regulator of bacterial physiology. Here we show that in the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the loss of Hfq can result in a dramatic reduction in growth in a manner that is dependent upon MexT, a transcription regulator that governs antibiotic resistance in this organism. Using a combination of chromatin immunoprecipitation with high-throughput sequencing and transposon insertion sequencing, we identify the MexT-activated genes responsible for mediating the growth defect of hfq mutant cells. These include a newly identified MexT-controlled gene that we call hilR. We demonstrate that hilR encodes a small protein that is acutely toxic to wild-type cells when produced ectopically. Furthermore, we show that hilR expression is negatively regulated by Hfq, offering a possible explanation for the growth defect of hfq mutant cells. Finally, we present evidence that the expression of MexT-activated genes is dependent upon GshA, an enzyme involved in the synthesis of glutathione. Our findings suggest that Hfq can influence the growth of P. aeruginosa by limiting the toxic effects of specific MexT-regulated genes. Moreover, our results identify glutathione to be a factor important for the in vivo activity of MexT.

IMPORTANCE Here we show that the conserved RNA chaperone Hfq is important for the growth of the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. We found that the growth defect of hfq mutant cells is dependent upon the expression of genes that are under the control of the transcription regulator MexT. These include a gene that we refer to as hilR, which we show is negatively regulated by Hfq and encodes a small protein that can be toxic when ectopically produced in wild-type cells. Thus, Hfq can influence the growth of P. aeruginosa by limiting the toxic effects of MexT-regulated genes, including one encoding a previously unrecognized small protein. We also show that MexT activity depends on an enzyme that synthesizes glutathione.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen of humans and the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients (1). P. aeruginosa infections are difficult to treat, in part due to the intrinsic resistance of P. aeruginosa to a wide range of antibiotics (2, 3). The activation of several energy-dependent multidrug efflux pump systems has been shown to confer enhanced antibiotic resistance and has emerged as an important mechanism for the acquisition of multidrug resistance in P. aeruginosa (4).

The MexEF-OprN multidrug efflux pump has been shown to confer resistance to norfloxacin, quinolones, imipenem, and chloramphenicol (5). Mutations that lead to the constitutive expression of mexEF-oprN are readily isolated in vivo (6, 7) and in vitro (8). Among these are mutations that enhance the activity of MexT, a LysR-type transcription activator that positively regulates the expression of mexEF-oprN (8–13). Interestingly, mutations that diminish or abolish the activity of MexT can be selected for in vivo and have been shown to enhance known virulence traits of P. aeruginosa (14). Thus, MexT serves as an important regulator of P. aeruginosa biology by reciprocally regulating virulence and antibiotic resistance.

The regulator Hfq, an RNA chaperone protein, has been shown to regulate diverse cellular processes in many bacterial species. Hfq can recognize specific sites on the RNA and typically represses the translation of target transcripts or influences their stability (15). Hfq is thought to mediate many of its regulatory effects by facilitating interactions between small regulatory RNAs and target mRNAs (16). However, there are instances in which Hfq is thought to exert its regulatory effects without the assistance of any small RNA (sRNA) species (17–19). In P. aeruginosa, Hfq plays important roles in the control of catabolite repression and is essential for virulence (20). Transcriptomic studies suggest that Hfq influences the expression of hundreds of genes in P. aeruginosa (17, 21–23). A recent chromatin immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) study revealed that Hfq targets more than 600 nascent transcripts in this organism (24). The loss of hfq in P. aeruginosa has been shown not only to reduce several virulence traits, such as pyocyanin production or motility, but also to result in severely diminished growth on nonpreferred carbon sources (20). Indeed, Hfq is important for the growth or virulence of many different bacterial species (20, 25–34).

In this work, we sought to identify genes that contribute to the severe growth defect that we observed when P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 cells lacking hfq were grown on lysogeny broth (LB) agar. We discovered that deleterious mutations in mexT restore the growth of cells lacking hfq because they abrogate the MexT-dependent activation of mexEF and a previously uncharacterized gene, PA1942, referred to here as hilR. We demonstrate that Hfq regulates the expression of hilR and that the glutathione biosynthesis enzyme GshA is required for MexT-dependent transcription activation.

RESULTS

Loss of Hfq in P. aeruginosa results in a severe growth defect on LB agar.

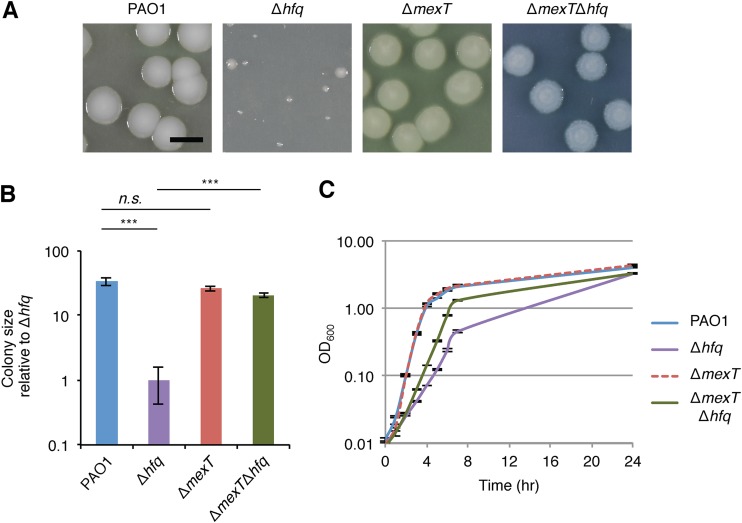

In the course of studying a small regulatory RNA in P. aeruginosa strain PAO1, we constructed a mutant derivative containing an in-frame deletion of hfq and thus lacking the RNA chaperone Hfq. PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells produced very small colonies when grown on LB agar that were apparent only after 2 to 3 days of incubation at 37°C (Fig. 1A and B). The severe growth defect of the PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells could be complemented by supplying hfq on a plasmid (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), indicating that the growth defect of our PAO1 Δhfq mutant was due to the loss of Hfq.

FIG 1.

The growth defect of PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells is suppressed by the loss of mexT. (A) Colonies of strains bearing markerless in-frame deletions of the genes indicated grown on LB agar at 37°C for 72 h. Bar, 5 mm. (B) Sizes of the colonies from panel A. The values are the means for 20 colonies relative to the size of colonies from PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells; error bars indicate ±1 standard deviation. P values were determined by one-way Student's t test. ***, P < 0.001; n.s., not significant. (C) Growth of PAO1, PAO1 ΔmexT, PAO1 Δhfq, and PAO1 ΔmexT Δhfq mutant cells in LB, recorded by measuring the OD600 of cells cultured at 37°C for 24 h.

A modest growth defect has previously been reported for P. aeruginosa PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells cultured in LB liquid medium (20); however, we found the growth of our PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells in LB to be substantively reduced relative to that of wild-type cells (Fig. 1C). Nevertheless, the growth defect of our PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells appeared to be much more pronounced when grown on LB agar than when grown in LB liquid (Fig. 1A to C). Taken together, our findings suggest that Hfq is critical for the growth of P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 when grown on LB agar.

To determine whether Hfq is important for the growth of P. aeruginosa strains other than PAO1, we created an in-frame deletion of hfq in cells of the clinical isolate strain PA99 (35). PA99 Δhfq mutant cells exhibited a dramatic growth defect relative to wild-type cells when grown on LB agar (Fig. S2). This finding suggests that Hfq may be critical for the growth of a variety of P. aeruginosa strains on LB agar.

Prior work suggested that PAO1 Δhfq mutants can grow in minimal medium (no-carbon E broth [NCE]) supplemented with succinate as a sole carbon source (NCE-succinate) but are unable to grow in minimal medium supplemented with glucose (20). We found that our PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells produced colonies of a similar size to wild-type colonies when grown on NCE-succinate agar plates (Fig. S3A and B). Thus, Hfq does not appear to be critical for the growth of P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 under all conditions.

Loss of MexT suppresses the pronounced growth defect of PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells.

We noticed that cells of our PAO1 Δhfq mutant strain gave rise to both small colonies and some colonies of a larger size when plated on LB agar (Fig. 1A). We surmised that the loss of hfq caused a profound growth defect on LB agar that could be suppressed by a spontaneous secondary mutation (or mutations) that enhanced cell growth. To test this idea, we selected 18 large colonies that arose when cells of our PAO1 Δhfq mutant strain were grown for 2 days at 37°C on LB agar. Whole-genome sequencing of putative suppressor mutant strains revealed that, in addition to the hfq deletion, the suppressor mutants that we tested contained either a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), a large chromosomal deletion, or multiple mutations (Table 1). Six independent SNPs in the mexT gene, encoding the LysR-type transcription regulator MexT (36), were discovered in different putative suppressor mutant strains (Table 1). In addition, cells of four other putative suppressor strains contained large deletions that encompassed the mexT gene (i.e., PA2492) (Table 1). The results of our whole-genome sequencing analyses suggest that the growth defect of cells lacking hfq can be suppressed through a variety of mutations, including different SNPs and deletions. Furthermore, our findings raised the possibility that the loss of mexT or mutations that reduce either the activity or the abundance of MexT can suppress the growth defect of our PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells.

TABLE 1.

Identification of mutations that suppress the small-colony phenotype of PAO1 Δhfq mutant cellsa

| Mutation type | Mutations |

|---|---|

| SNP | MexT (R28H), MexT (Q185fs), MexT (R46H), MexT (G105S), MexT (P127L), GltR (S34fs), PA2114 (G363D), PA4753 (L83syn), PtsP (S697W) |

| Deletion | ΔPA2466-PA2551, ΔPA2222-PA2503, ΔPA2424-PA2503, ΔPA2251-PA2494 |

| Multiple mutations | ΔPA1906-PA2318 and Dup(PA4217-PA4280), PtsP (S697W) and MexT (E19D), ΔPA2073-PA2213 and PtsP (S697W), ΔPA2108-PA2219 and GltR (S34fs), Dup(PA2690-PA3434) and PA2114 (G363D) |

Whole-genome sequencing identified mutations associated with a restoration in the growth of PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells for 18 strains. The relevant amino acid changes resulting from SNP mutations are indicated in parentheses. fs, a SNP that results in a frameshift subsequent to the specified amino acid; syn, a SNP mutation that results in a synonymous substitution of the specified amino acid; Δ, a deletion; Dup, a duplication that encompasses the genes included in parentheses. The amino acid changes indicated for MexT are based on the sequence of mexT from MPAO1 (GCA_000247435.2), encoding a protein with 304 amino acid residues, which is identical to the sequence of mexT in our PAO1 strain.

To test explicitly whether the loss of mexT could suppress the growth of our PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells, we deleted hfq in PAO1 cells that contained a deletion of mexT. We found that the loss of hfq did not appear to profoundly reduce the growth of cells containing the ΔmexT mutation on LB agar (Fig. 1A and B). The sizes of colonies from PAO1 ΔmexT mutant cells were similar to those of wild-type colonies (Fig. 1A and B), suggesting that the loss of mexT can suppress the growth defect of PAO1 mutant cells lacking Hfq. Consistent with this interpretation, ectopic expression of mexT was found to inhibit the growth of the PAO1 ΔmexT Δhfq mutant cells (i.e., to complement the phenotype of the ΔmexT mutation in the Δhfq mutant background) (Fig. S4). Furthermore, comparison of the growth of wild-type PAO1, PAO1 ΔmexT, PAO1 Δhfq, and PAO1 ΔmexT Δhfq mutant cells in LB indicated that the ΔmexT mutation partially restored the growth rate of Δhfq mutant cells but had no significant impact on the growth of otherwise wild-type (i.e., hfq+) cells (Fig. 1C). These findings suggest that the loss of mexT can suppress the growth defect observed in PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells grown either on LB agar or in LB.

Identification of MexT target genes using ChIP-seq.

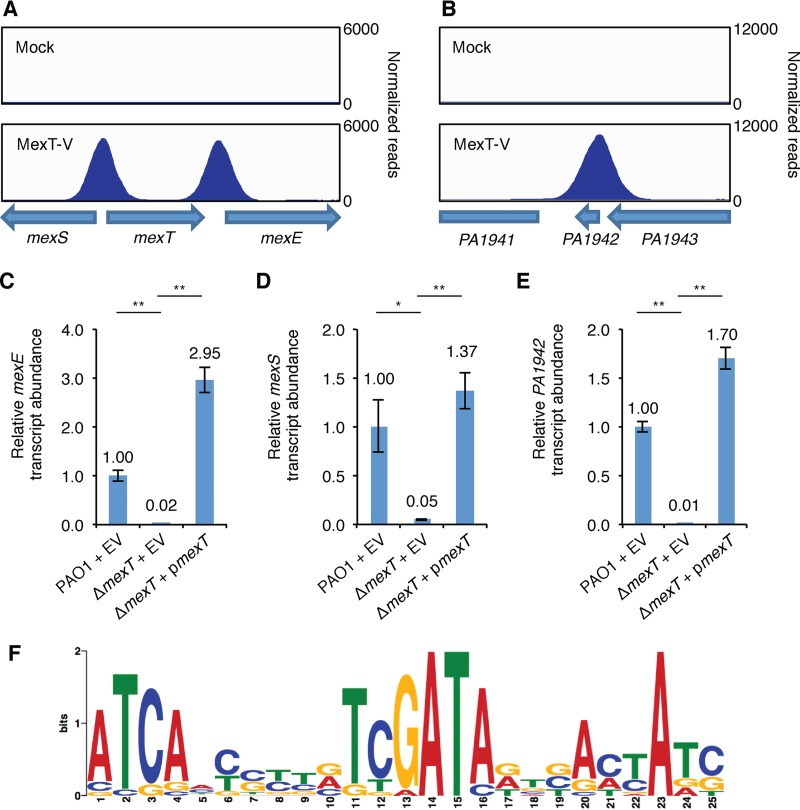

Because MexT primarily functions as a transcription activator (36), we suspected that the loss of mexT in PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells contributed to restored growth in LB due to a reduction in expression of a MexT-activated gene whose product is important for the effect of a Δhfq mutation on growth. To identify genes that might be direct regulatory targets of MexT, we used chromatin immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq). First, we generated a strain expressing a C-terminal vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) epitope-tagged version of MexT (MexT-V) from the native mexT locus. We grew wild-type PAO1 and PAO1 MexT-V cells to mid-log and stationary phases and performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for the VSV-G epitope. ChIP of MexT-V reproducibly enriched 22 genomic loci greater than 2-fold relative to their expression in the wild-type PAO1 mock control in either the mid-log or stationary phase of growth (Table S1). We found that MexT associates with chromosomal regions found upstream of the vast majority of genes previously demonstrated to be positively regulated by MexT (36), including the MexT-activated mexEF-oprN and mexS loci (Fig. 2A and Table S1). The MexT-binding motif derived from our ChIP-seq study (Fig. 2F) is in good agreement with the predicted MexT-binding motif found upstream of known MexT-regulated genes (36).

FIG 2.

MexT associates with the mexS, mexE, and PA1942 genes. (A, B) ChIP-seq with MexT-V identifies enrichment peaks near mexS and mexE (A) as well as PA1942 (B) in cells grown to mid-log phase. Genes are indicated by arrows at the bottom of each panel. (C to E) Expression of the mexE (C), mexS (D), or PA1942 (E) gene, measured by qRT-PCR, in PAO1 cells transformed with plasmid pPSPK (indicated the empty vector [EV]) or PAO1 ΔmexT mutant cells transformed with EV or plasmid pPSPK-mexT (pmexT). All cells were grown in LB to mid-log phase, and then IPTG (1 mM), which induces expression of mexT in cells containing pmexT, was added for 1 h. The relative abundance of each transcript was normalized to that of clpX. P values were determined by a one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. The primers used to amplify a transcript within the PA1942 ORF are the same as those used to amplify a transcript within the hilR ORF. (F) Sequence logo representation of the experimentally determined MexT-binding site motif derived from nonredundant sequences in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The logo was generated using the MEME program.

We identified two novel targets for MexT using ChIP-seq and sought to determine whether MexT regulates the expression of the associated genes. The MexT association occurred proximal to PA1333 (Fig. S5) and PA1942 (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the idea that MexT positively regulates the expression of these genes, we found, using quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR), that the abundance of the PA1942 and PA1333 transcripts was dramatically decreased in the absence of mexT in a manner that could be complemented with ectopic expression of mexT (Fig. 2E and S6). Similarly, qRT-PCR revealed that the expression of the known MexT-activated mexE and mexS genes was positively regulated by MexT in our strain of PAO1 (Fig. 2C and D). We note that prior analyses performed using a neural network-based feature extraction approach suggested that PA1942 might be part of the MexT regulon (37).

Tn-seq reveals MexT-activated genes with toxicity in Δhfq mutant cells.

Having identified the set of MexT target genes in PAO1, we next sought to determine whether the expression of one or more of these genes contributes to the growth defect seen in Δhfq mutant cells grown on LB agar. To do this, we used transposon mutagenesis and high-throughput sequencing (Tn-seq) to comprehensively identify genes whose inactivation suppressed the growth defect of Δhfq mutant cells. In particular, we first generated a library with ∼300,000 independent transposon insertions in PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells grown on NCE-succinate agar (conditions under which the selection of spontaneous mutant suppressors is reduced). Then, we screened a pool of ∼30,000,000 colonies from this library (i.e., 100× coverage of the mutant library) on LB agar. We purified genomic DNA (gDNA) from cells grown on LB agar as well as DNA from cells of the input library (originally harvested from cells grown on NCE-succinate agar), created sequencing libraries, and mapped reads corresponding to transposon insertions to the PAO1 genome. We expected that reads mapping to transposon insertions that resulted in large colonies on LB agar would be overrepresented in genomic DNA isolated from cells of the library which had been grown under these conditions relative to genomic DNA isolated from cells of the input library which had been grown on NCE-succinate.

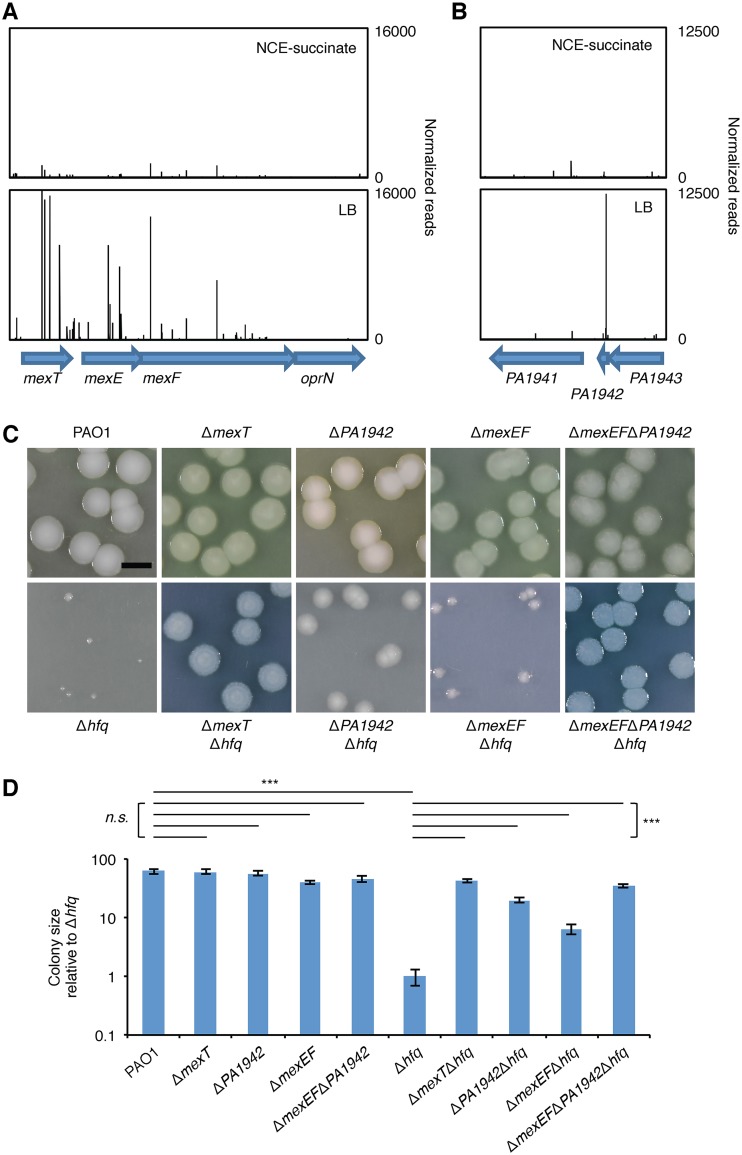

We found that there were 38 intragenic or intergenic regions with statistically significant increases (>2-fold) in the number of reads mapping to transposon insertions under the LB agar growth condition relative to the NCE-succinate growth condition (Table S2). Consistent with our whole-genome sequencing results, reads mapping to transposon insertions in the mexT gene were more abundant in cells of the transposon-mutagenized PAO1 Δhfq mutant library grown on LB agar than in cells of the input library. Importantly, we discovered that insertions in the MexT-regulated genes PA1942, mexE, and mexF were overrepresented in cells grown on LB agar (Fig. 3A and B). This suggested that insertional inactivation of these MexT-regulated genes enhanced the growth of Δhfq mutant cells on LB agar. It is noteworthy that no other MexT-regulated gene described previously or here was identified to be a putative suppressor of the growth defect of Δhfq mutant cells. These results suggest that the MexT-dependent activation of PA1942, mexE, and mexF results in toxicity in cells lacking Hfq.

FIG 3.

MexT-activated genes mexE and PA1942 contribute to the growth defect observed in Δhfq mutant cells. (A, B) Tn-seq profiles for genomic regions spanning mexT-oprN (A) or PA1942 (B) from analyses performed in the PAO1 Δhfq mutant strain grown on NCE-succinate or LB agar. The bars above the locus map represent transposon insertion sites, and the height of each bar indicates the number of normalized sequencing reads at that site. (C) Colonies of strains bearing markerless in-frame deletions of the genes indicated grown on LB agar at 37°C for 72 h. Bar, 5 mm. (D) Sizes of the colonies from panel C. The values are the means for 20 colonies relative to the size of colonies from PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells; error bars indicate ±1 standard deviation. P values were determined by one-way Student's t test. ***, P < 0.001; n.s., not significant.

To test whether the loss of the MexT-activated PA1942, mexE, and mexF genes contributed to the growth defect seen in PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells grown on LB agar, we first constructed PAO1 mutants that contained in-frame deletions of PA1942, mexEF, or PA1942 together with mexEF in PAO1. We then deleted hfq in each of the resulting PAO1 ΔmexEF, PAO1 ΔPA1942, and PAO1 ΔmexEF ΔPA1942 mutant cells. The results, depicted in Fig. 3C and D, suggest that the loss of PA1942 or mexEF can suppress the growth defect of PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells grown on LB agar. We observed that the loss of PA1942 had a greater suppressive effect than the loss of mexEF on the growth of Δhfq mutant cells but that none of these mutations restored growth to the same extent as a ΔmexT mutation. However, the loss of PA1942 and mexEF combined resulted in a similar effect as the loss of mexT on the growth of Δhfq mutant cells (Fig. 3C and D). Taken together, these findings suggest that the MexT-dependent activation of mexEF and PA1942 expression is responsible for the growth defect of Δhfq mutant cells on LB agar (Fig. 3C and D).

hilR encodes a small protein that can be toxic in P. aeruginosa.

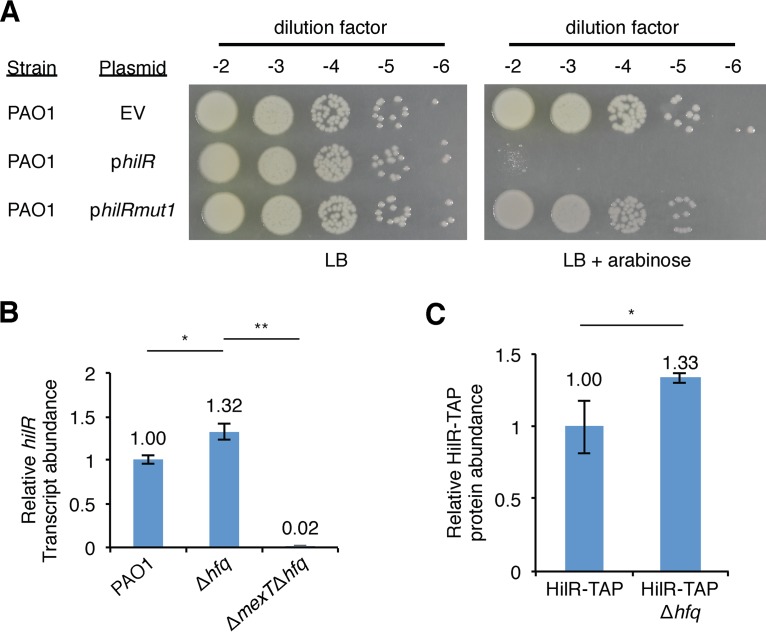

The PA1942 gene is predicted to encode a small hypothetical protein of unknown function. We used our MexT ChIP results to identify a putative MexT-binding site near PA1942. We observed that our predicted MexT-binding site overlapped the annotated open reading frame (ORF) for PA1942. Reasoning that the PA1942 ORF was likely misannotated, we identified a putative promoter downstream of the predicted MexT-binding site and identified two possible ORFs downstream of this promoter, the longer of which (referred to henceforth as hilR, for Δhfq-interacting locus regulating growth) is in frame with the annotated ORF of PA1942. When placed downstream of an arabinose-inducible promoter on a plasmid vector, the portion of PA1942 containing the hilR ORF could restore the growth defect observed in Δhfq mutant cells to cells of the ΔPA1942 Δhfq mutant grown on medium supplemented with arabinose (Fig. S7). Induction of the portion of PA1942 containing the hilR ORF was toxic to cells of wild-type PAO1 (Fig. 4A). These data suggest that ectopic expression of hilR can be detrimental to the growth of wild-type cells. To determine whether the hilR ORF was required for the toxic effect observed in wild-type cells, we engineered a mutant version of our plasmid with the portion of PA1942 containing the hilR ORF in which a stop codon was introduced early on in the hilR ORF but the second ORF was left unaltered. Cells containing this mutated version of the arabinose-inducible hilR expression construct grew just as well on medium supplemented with arabinose as they did on medium that lacked arabinose (Fig. 4A). This result is consistent with HilR being translated from the hilR ORF, producing a small, toxic protein of only 44 amino acids.

FIG 4.

hilR encodes a toxic small protein, and hilR expression is regulated by Hfq. (A) PAO1 cells were transformed with plasmids pHerd20T (EV), pHerd20T-hilR (philR), or pHerd20T-hilRmut1 (philRmut1), and transformants were selected on LB agar with 200 μg ml−1 carbenicillin. Single colonies were mixed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), normalized for cell density (OD600 = 0.1), and serially diluted, and 7.5 μl of each dilution (10−2 to 10−6) was spotted onto LB agar with 200 μg ml−1 carbenicillin with and without 0.1% arabinose before incubation at 37°C for 24 h. (B) Expression of hilR measured by qRT-PCR in PAO1, PAO1 Δhfq, and PAO1 ΔmexT Δhfq cells grown in LB to mid-log phase. The relative hilR transcript abundance was normalized to clpX transcript levels. The primers used to amplify a transcript within the hilR ORF are the same as those used to amplify a transcript within the PA1942 ORF. P values were determined by a one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test. *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01. (C) Results of Western blot analysis of HilR-TAP in PAO1 HilR-TAP and PAO1 HilR-TAP Δhfq cells. The RNA polymerase alpha subunit was used as a loading control. The bar graph shows the quantitation of HilR-TAP relative to the abundance of the RNA polymerase alpha subunit from a representative experiment performed with biological triplicates. P values were determined by one-way Student's t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Hfq represses the expression of hilR.

Given that ectopic expression of the hilR gene is toxic in wild-type cells, we predicted that the detrimental effect of the hilR gene in Δhfq mutant cells could result from an effect of hfq on the MexT-dependent activation of hilR expression. We measured the abundance of the hilR transcript in PAO1 wild-type, PAO1 Δhfq, and PAO1 ΔmexT Δhfq mutant cells grown to mid-log phase. We found that hilR expression was modestly, but reproducibly, elevated in Δhfq mutant cells and dramatically decreased in ΔmexT Δhfq mutant cells (Fig. 4B). These findings raised the possibility that the growth defect of Δhfq mutant cells could result from an increase in MexT-dependent activation of hilR. Indeed, we found that, like hilR, the abundance of the MexT-regulated mexS transcript was slightly higher in Δhfq mutant cells than in wild-type cells (Fig. S8A). However, the abundance of the mexE and mexT transcripts was modestly decreased in Δhfq mutant cells compared to wild-type cells (Fig. S8B and C). These findings suggest that Hfq might independently exert a negative effect on the expression of certain MexT-regulated genes, such as mexS and hilR.

To determine whether the observed increase in hilR transcript abundance in Δhfq mutant cells led to an increase in the intracellular concentration of HilR, we created an epitope-tagged version of hilR by introducing a tandem affinity purification (TAP) tag in frame with the predicted hilR ORF at the endogenous chromosomal locus. We also constructed an additional strain in which we deleted hfq in cells synthesizing HilR-TAP. Western blot analysis of PAO1 HilR-TAP and PAO1 Δhfq HilR-TAP cells grown to mid-log phase revealed that HilR-TAP is more abundant in cells of the Δhfq mutant (Fig. 4C). Consistent with our observation that mexT transcript abundance is unchanged in Δhfq mutant cells, we found that MexT protein abundance in Δhfq mutant cells was unchanged from that in wild-type cells (Fig. S9). Taken together, our results suggest that an increase in the abundance of HilR in Δhfq mutant cells could contribute to the observed hilR-influenced growth defect in these mutants.

Expression of mexS promotes the growth of Δhfq mutant cells by inhibiting MexT activity.

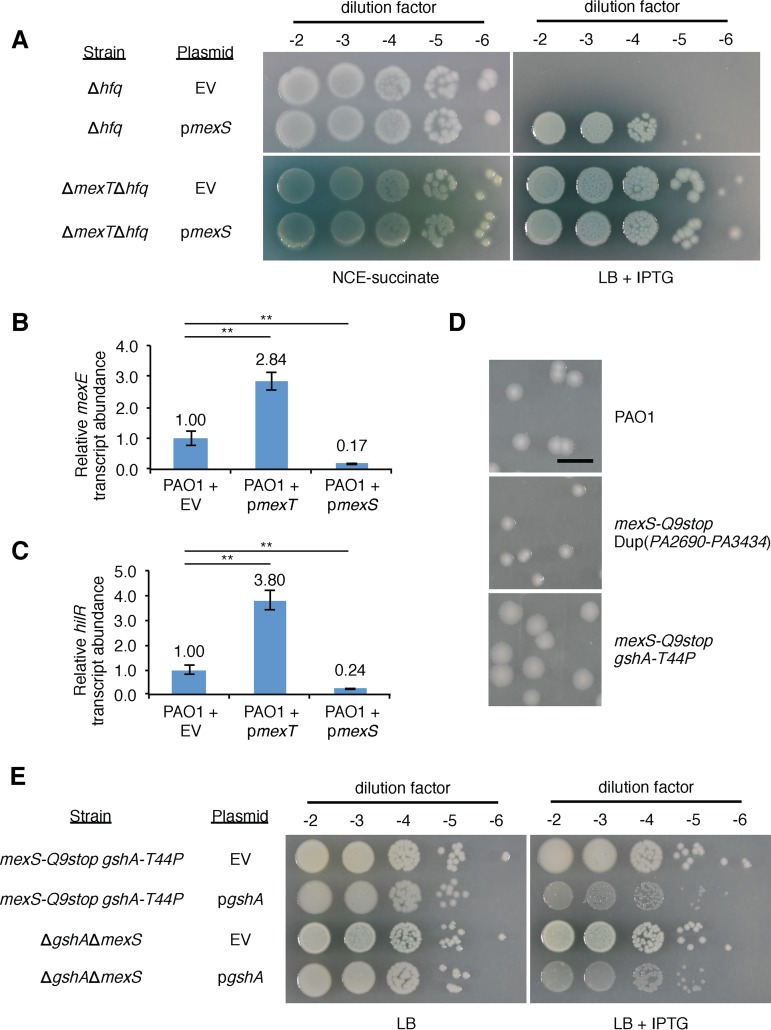

Previous work on nfxC-type resistance to antibiotics in P. aeruginosa found that mutations in mexS contribute to resistance by promoting MexT-dependent activation of the mexEF-oprN genes, encoding an RND-type efflux pump (38). These findings suggest that MexS antagonizes the function of MexT (38). However, other work suggested that MexS might function by stimulating the activity of MexT (39). We reasoned that if MexS functions to antagonize MexT activity, then expression of mexS would rescue the growth defect observed in Δhfq mutant cells. We found that ectopic expression of mexS promoted the growth of Δhfq mutant cells (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, ectopic expression of mexS had no obvious effect on the growth of PAO1 ΔmexT Δhfq mutant cells (Fig. 5A). This suggests that mexS antagonizes the function of MexT in Δhfq mutant cells. Consistent with this idea, we found that ectopic expression of mexS in wild-type cells decreased the expression of the MexT-activated genes implicated in the growth defect observed in Δhfq mutant cells (Fig. 5B and C).

FIG 5.

Ectopic expression of mexS mitigates the growth defect of Δhfq mutant cells and reduces the expression of MexT-activated genes in wild-type cells. (A) PAO1 Δhfq mutant cells were transformed with pPSPK (EV), PAO1 ΔmexT Δhfq mutant cells were transformed with plasmid EV or pPSPK-mexS (pmexS), and transformants were selected on NCE-succinate agar with gentamicin at 30 μg ml−1. Single colonies were mixed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), normalized for cell density (OD600 = 0.1), and serially diluted, and 7.5 μl of each dilution (10−2 to 10−6) was spotted onto NCE-succinate agar with gentamicin at 30 μg ml−1 and LB agar with gentamicin at 30 μg ml−1 and 5 mM IPTG before incubation at 37°C for 48 h. (B, C) Expression of the mexE (B) or hilR (C) gene, measured by qRT-PCR, in PAO1 cells transformed with pPSPK (EV), pPSPK-mexT (pmexT), or pPSPK-mexS (pmexS). All cells were grown in LB to mid-log phase, and then IPTG (1 mM), which induces expression of mexT or mexS in cells containing pmexT or pmexS, respectively, was added for 45 min. The relative abundance of each transcript was normalized to that of clpX. P values were determined by a one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test. **, P < 0.01. (D) Colonies of strains with the indicated mutations (discovered by whole-genome sequencing) grown on LB at 37°C for 24 h. Bar, 5 mm. Dup(PA2690-PA3434) indicates a large-scale duplication event of a region of the chromosome between PA2690 and PA3434. gshA-T44P indicates an SNP that results in a nonsynonymous amino acid substitution in GshA. (E) PAO1 mexS-Q9stop gshA-T44P and PAO1 ΔgshA ΔmexS cells were transformed with plasmid pPSPK (EV) or pPSPK-gshA (pgshA), and transformants were selected on LB agar with gentamicin at 30 μg ml−1. Single colonies were mixed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), normalized for cell density (OD600 = 0.1), and serially diluted, and 7.5 μl of each dilution (10−2 to 10−6) was spotted onto LB agar with gentamicin at 30 μg ml−1 with and without 5 mM IPTG before incubation at 37°C for 24 h.

Loss of MexS causes a GshA- and MexT-dependent growth defect.

In order to test the effects of the loss of mexS on MexT-activated gene expression, we introduced a stop codon early on in the mexS gene (at codon 9), producing the mexS Q9stop mutant. Surprisingly, we discovered that colonies of the mexS Q9stop mutant were of variable size when plated on LB. We purified a single small-colony variant and a single large-colony variant (Fig. 5D) and performed whole-genome sequencing to identify possible secondary mutations that might account for the differences in colony size. In the small-colony variant, in addition to the mexS Q9stop mutation, we discovered a large-scale duplication from PA2690 to PA3434 [Dup(PA2690-PA3434)], which was also discovered in our screen of spontaneous suppressors of the growth defect of Δhfq mutant cells (Table 1). In the large-colony variant, in addition to the mexS Q9stop mutation, we discovered a single missense mutation in the gshA gene, encoding a glutamate-cysteine ligase that is involved in glutathione synthesis. Ectopic expression of wild-type gshA in cells of this large-colony variant resulted in a reduction in colony size when cells were grown on LB (Fig. 5E). In addition, we generated an in-frame deletion of mexS in ΔgshA mutant cells and observed a similar reduction in colony size upon ectopic expression of gshA in these ΔgshA ΔmexS double mutants (Fig. 5E). These findings suggest (i) that mexS is important for the growth of P. aeruginosa and (ii) that the mutant form of GshA made by the mexS Q9stop large-colony variant (containing GshA with the amino acid substitution T44P) is less active or less abundant than the wild-type protein.

Our findings with the mexS Q9stop mutant led us to predict that mexS is critical for the growth of PAO1 wild-type cells because it inhibits the activity of MexT. Consistent with this prediction, ectopic expression of gshA inhibited the growth of ΔgshA ΔmexS mutant cells but did not inhibit the growth of cells of a ΔgshA ΔmexS ΔmexT triple mutant (Fig. S10). Furthermore, ectopic expression of mexT resulted in a growth defect in wild-type cells grown on LB agar but not in cells of a ΔmexEF ΔPA1942 mutant (Fig. S11), suggesting that increased MexT-dependent expression of mexEF and hilR results in a growth defect in wild-type cells. Finally, in the context of a ΔPA1942 (ΔhilR) mutant background, where the loss of MexS would be predicted to be less detrimental to cell growth, we found that expression of the MexT-activated mexE gene was higher in cells that lacked mexS (i.e., in ΔmexS ΔPA1942 mutant cells) than in cells of the ΔPA1942 single mutant and that the effect of deleting mexS could be restored through mexS ectopic expression (Fig. S12). Taken together, our findings support a model in which the loss of mexS is detrimental to the growth of P. aeruginosa because it results in an increase in expression of MexT-activated genes.

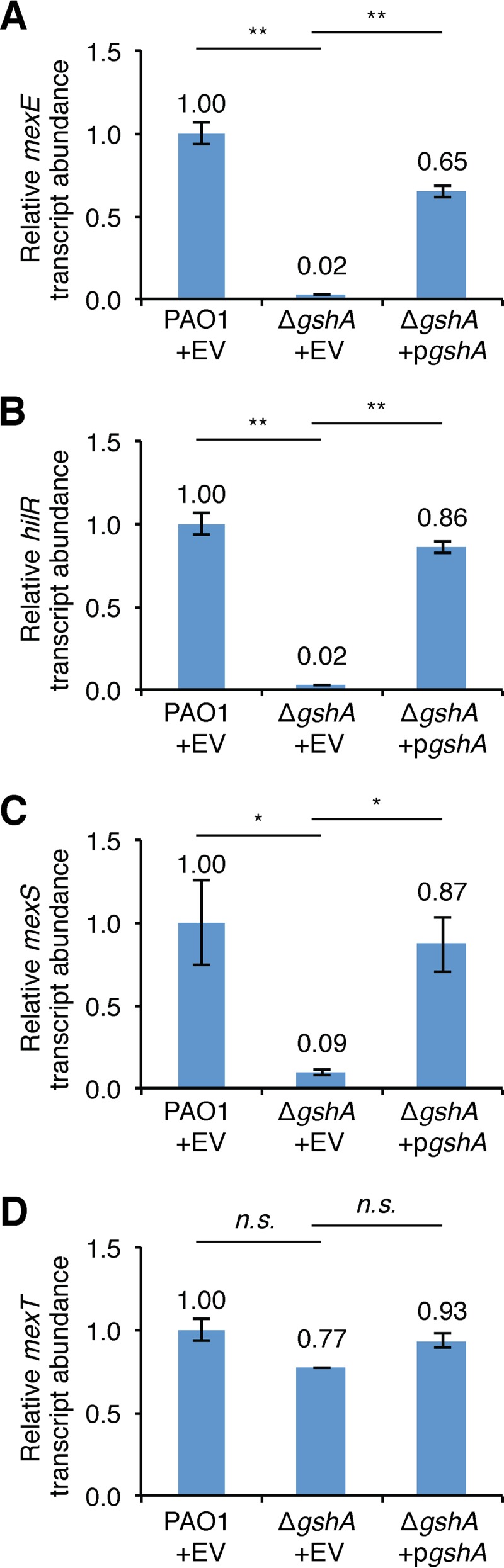

GshA is critical for MexT activity.

We reasoned that the missense mutation in gshA arose in the large-colony variant of the mexS Q9stop mutant because it suppressed the growth defect resulting from the mexS mutation. This raised the possibility that gshA is important for the activity of MexT. To determine whether or not this was the case, we measured the expression of MexT-activated genes in both PAO1 wild-type and ΔgshA mutant cells. Consistent with the idea that gshA is critical for the activity of MexT, the expression of the MexT-activated mexE, hilR, and mexS genes was dramatically reduced in cells of the PAO1 ΔgshA mutant strain relative to wild-type cells in a manner that could be restored upon ectopic expression of gshA (Fig. 6A to C). In addition, the loss of gshA had only a very modest effect on the expression of the mexT gene itself (Fig. 6D). The abundance of MexT-activated transcripts was reduced similarly in ΔmexT and ΔgshA mutant cells (Fig. 2C to E and 6A to C), indicating that GshA is essential for the activity of MexT. Moreover, these findings suggest that gshA mutations spontaneously arise in mexS mutant cells because they abrogate the expression of MexT-activated genes.

FIG 6.

GshA is required for MexT-dependent gene activation. Expression of the mexE (A), hilR (B), mexS (C), and mexT (D) genes measured by qRT-PCR in PAO1 cells transformed with pPSPK (EV) or PAO1 ΔgshA cells with EV or pPSPK-gshA (pgshA). All cells were grown in LB to mid-log phase, and then IPTG (1 mM), which induces expression of gshA in cells that contain pgshA, was added for 45 min. The relative abundance of each transcript was normalized to that of clpX. P values were determined by a one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; n.s., not significant.

DISCUSSION

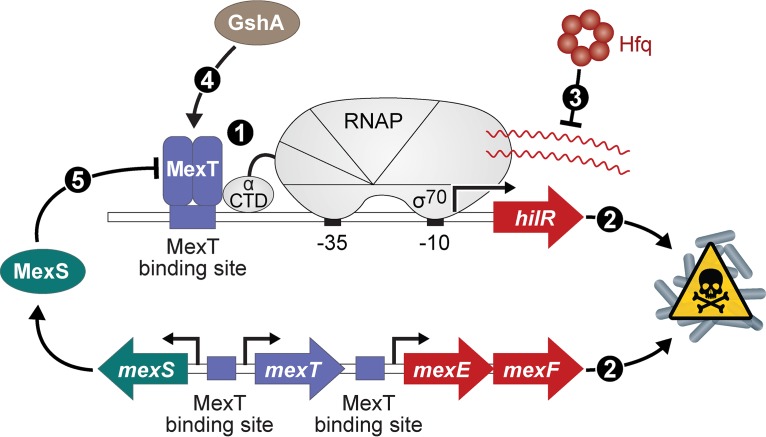

We have found that Hfq is critical for the growth of P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 on LB agar. The reduced growth that we observed in these mutant cells was due, at least in part, to the activities of genes whose expression is positively regulated by MexT. These include mexEF, encoding components of an RND multidrug efflux pump, as well as the novel MexT-regulated gene hilR. The expression of hilR is negatively regulated by Hfq, which may explain why cells lacking this RNA chaperone exhibit a growth defect. We also identified the direct regulatory targets of MexT using ChIP-seq and obtained evidence that the activity of this important transcription regulator is dependent upon GshA, an enzyme involved in the synthesis of glutathione. From our results, we propose an integrated model for the regulation of a toxic pathway in P. aeruginosa by Hfq, MexT, and GshA (Fig. 7).

FIG 7.

Proposed model for regulation of a MexT-activated toxic pathway. MexT binds specific sites located upstream of hilR, mexE, and mexS to positively regulate the expression of these genes (1). Activation of hilR and mexEF contributes to toxicity in PAO1 cells (2). Hfq functions to repress the expression of hilR in PAO1 cells (3). GshA promotes MexT-dependent activation of target genes (4). MexS functions to inhibit MexT-dependent activation of target genes, including hilR, mexE, and mexS (5).

We report that the previously uncharacterized hilR gene is a MexT-activated gene that is conserved among P. aeruginosa isolates and that hilR homologs are found in other species in the Pseudomonas genus. Using genetic approaches, we established that hilR, corresponding to PA1942, specifies a protein of 44 amino acids, which is smaller than that currently annotated for PA1942 (40). Although the physiological role of HilR is unclear, HilR is toxic in cells of an hfq mutant and can be toxic to wild-type cells when produced ectopically. There are reports of several small proteins of less than 50 amino acids from other bacteria being acutely toxic when overproduced (41). It is becoming increasingly clear that small proteins can play critical roles in a variety of cellular processes, such as small-molecule transport or cell division, and can mediate their effects through interaction with protein complexes (42). Indeed, in Escherichia coli the small protein AcrZ interacts with the AcrAB-TolC multidrug efflux pump to enhance its action on certain substrates (43). Note that we do not necessarily think that HilR interacts directly with components of the MexEF-OprN multidrug efflux pump to stimulate its activity, as the deletion of hilR appears to suppress the Δhfq mutant growth defect more strongly than does deletion of mexEF (Fig. 3C and D). Nevertheless, it will be interesting to determine whether or not HilR acts through interaction with other protein partners.

We found that Hfq influences the expression of hilR as well as the abundance of HilR. Consistent with these findings, prior transcriptome profiling studies identified hilR (PA1942) to be a gene that is subject to control by Hfq (22). Moreover, recent ChIP studies revealed that Hfq interacts with the hilR nascent transcript (24), suggesting that Hfq likely exerts its effects on hilR expression by interacting directly with the hilR mRNA. An interaction between Hfq and a specific site on the hilR mRNA could inhibit the translation of hilR and possibly influence the stability of the hilR transcript. Although Hfq can interfere with the translation of mRNA species by facilitating the base pairing between sRNAs and their mRNA targets (15), this is not always the case (19), and it remains to be determined whether the control of hilR by Hfq involves an sRNA.

How MexEF contribute to the growth defect of Δhfq mutant cells is unclear. MexEF are components of the MexEF-OprN multidrug efflux pump that is responsible for the efflux of several small molecules (44–46). The loss of mexEF might therefore create a situation in which a particular small molecule builds up to a level that is inhibitory to growth in cells of a Δhfq mutant. However, the activity of MexEF-OprN has also been linked to the control of gene expression in P. aeruginosa, presumably as a result of its effects on the intracellular concentrations of small molecules that influence the activities of transcription factors (36). Indeed, one of the substrates for MexEF-OprN is 4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline (HHQ), which is a precursor of the Pseudomonas quinolone signal that influences the expression of genes regulated by quorum sensing (46, 47). It is therefore possible that MexEF inhibit the growth of cells of a Δhfq mutant through an indirect effect on gene expression. Regardless of how MexEF or HilR inhibits the growth of Δhfq mutant cells, their combined inhibitory effects appear to result in a selective pressure that favors the loss of MexT activity.

We identified mutations in mexT that suppressed the growth defect of our Δhfq mutant cells. However, mutations in P. aeruginosa that alter the mexT-dependent activation of target genes have arisen in a variety of contexts. Mutants with enhanced mexT-dependent activation of target genes were first discovered almost 30 years ago in a selection for norfloxacin-resistant (nfxC) mutants (5). These mutants were characterized by their overexpression of the multidrug efflux pump MexEF-OprN (48), their cross-resistance to imipenem and chloramphenicol (5), as well as their attenuation of virulence (45). nfxC-type mutants, which frequently arise through mutation of mexS (11), are readily selected in mice treated with chloramphenicol but can also arise in mice in the absence of chloramphenicol treatment (6). Mutations linked to the activation of mexEF-oprN have been observed in P. aeruginosa isolates recovered from a cystic fibrosis (CF) patient chronically infected with the organism (7). However, in other CF patient isolates, mutations in mexS as well as mexT were found to occur (49). A nonsense mutation in mexT, resulting in the expression of a truncated version of MexT, was discovered in a spontaneous PAO1 mutant that displayed an enhanced tissue-destroying phenotype in a rat (14). This mexT mutant (referred to as P2 [mexT]) exhibits enhanced virulence and a competitive growth advantage over P1 (i.e., mexT+) wild-type cells (14). Recently, it was reported that loss-of-function mutations in mexT restore the growth of lasR mutants grown in vitro in medium containing casein as a sole carbon source (50). The mexT-dependent growth restoration of a lasR mutant was shown to be partially dependent on the expression of mexE, suggesting that other MexT-activated genes also contribute to this phenotype. These results and ours illustrate that mexT mutants can be selected for in vitro in specific genetic backgrounds, under specific growth conditions, or both. In this regard it is noteworthy that certain PAO1 strains of P. aeruginosa do not encode functional versions of MexT (8). Our results indicate that the mexT allele found in our PAO1 strain produces a functional MexT protein capable of activating the transcription of target genes. It is therefore likely that the deletion of hfq will result in a significant growth defect only in derivatives of PAO1 that contain functional versions of MexT.

Our findings establish that an enzyme involved in glutathione biosynthesis, GshA, is required for the activity of MexT. GshA catalyzes the first and rate-limiting step in glutathione biosynthesis, which involves the formation of γ-glutamylcysteine from the ligation of glutamate and cysteine (51). Thus, glutathione or, possibly, γ-glutamylcysteine may be important for the activity of MexT in cells of P. aeruginosa. MexT belongs to the LysR family of transcription regulators that typically bind to target sequences on the DNA as tetramers in a manner that can be influenced by small molecules acting as coinducers or corepressors (52). In vitro experiments performed with purified MexT indicate that the protein can bind target DNA in the presence of oxidized but not reduced glutathione (53). Furthermore, it has been proposed that diamide activates the expression of the mexEF-oprN genes by oxidizing glutathione in the cell to promote the oligomerization of MexT at target promoters (53). Our findings provide genetic evidence in support of a role for glutathione in the control of MexT in vivo. Although our findings indicate that GshA is essential for the activity of MexT, it remains to be determined whether the effects of GshA on biofilm formation, stress resistance, motility, and virulence in P. aeruginosa (54, 55) are tied to its effects on the activity of MexT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

All experimental strains were derived from P. aeruginosa strains PAO1 and PA99 and are listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material. Bacterial cultures were grown at 37°C at 200 rpm in lysogeny broth (LB) medium or no-carbon E broth (NCE) supplemented with 20 mM succinate (NCE-succinate) (20), where indicated. For the experiment measuring the growth of cells in LB, overnight cultures grown in LB from colonies isolated on LB agar plates were backdiluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.01. Where indicated, Δhfq mutant cells were grown on NCE-succinate agar before plating on LB agar. Where appropriate, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: gentamicin, 30 μg ml−1 (15 μg ml−1 in E. coli cloning and mating strains), and carbenicillin, 200 μg ml−1 (100 μg ml−1 in E. coli cloning and mating strains). Where indicated, inducers were used at the following concentrations: 1 or 5 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) or 0.1% (vol/vol) l-arabinose.

Plasmid and strain construction.

All primers and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S3. Details of plasmid and strain construction are described in the supplemental material.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR.

Cells were backdiluted from overnight cultures to an OD600 of 0.01 in 50 ml LB and grown at 37°C with shaking to a mid-log-phase OD600 of ∼0.3 to 0.5. For experiments performed on cells bearing plasmids with IPTG-inducible genes, IPTG was added to mid-log-phase cultures at a final concentration of 1 mM and the cells were grown at 37°C with shaking for 30 to 60 min. For experiments on untransformed cells, cells were harvested at mid-log phase. Five milliliters of cells was harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 10 min. RNA was isolated using the Tri-Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc.) as previously described (56). RNA quality was determined by gel electrophoresis. cDNA synthesis using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) were performed essentially as described previously (57) using a LightCycler 96 system (Roche). The abundances of transcripts were measured relative to the abundance of the clpX transcript. qRT-PCR was performed at least twice on sets of biological triplicates. Relative expression values were calculated by using the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method (2−ΔΔCT) (58). The fold enrichment values shown are the means from three biological replicates, and error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. The data shown are from one representative experiment. Results were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test for significance.

Transposon mutagenesis.

P. aeruginosa PAO1 Δhfq cells were mutagenized with the minitransposon pBTK30 (59) using a mating protocol adapted from a previously described procedure (60). The donor strain SM10(λpir) carrying pBTK30 was grown in LB supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 ampicillin at 37°C, and PAO1 Δhfq was grown in NCE-succinate at 42°C overnight. On the next morning, cultures were concentrated and adjusted to an OD600 of 5 for the donor and an OD600 of 10 for each recipient. Equal volumes of donor and recipient were mixed together, and 50-μl aliquots were spotted on prewarmed LB plates. Matings were allowed to proceed at 37°C for 1 h prior to resuspension in NCE-succinate supplemented with 25 μg ml−1 triclosan (Irgasan) and 30 μg ml−1 gentamicin (NCE-succinate-Gm-Irg). Transconjugants were selected on NCE-succinate-Gm-Irg agar plates following incubation at 37°C for 48 h. Donor-only and recipient-only controls were performed in parallel to ensure counterselection against the E. coli donor and the selection of P. aeruginosa transconjugants, respectively. The approximate complexity (i.e., the number of transconjugants collected) of the input (NCE-succinate) library was ∼2.9 × 105 CFU. Transconjugant colonies were isolated from agar plates by suspension in NCE-succinate-Gm-Irg. Colonies were screened by diluting cells of the input library (which had been grown on NCE-succinate agar) in LB, plating dilutions on LB agar, and incubating at 37°C for 22 h. Colonies from this screen were scraped from the plates and resuspended in LB. The approximate complexity of the output (LB) library was 3.1 × 107 CFU. Cell pellets of each library consisting of approximately 5 × 109 CFU were collected and frozen at −80°C.

Transposon sequencing.

Genomic DNA from thawed cell pellets of each mutant library was extracted, fragmented, poly(C) tailed, and purified as previously described (61). gDNA libraries were constructed and sequenced as previously described (60). Trimmed reads were mapped to TA insertion sites, normalized to total reads, and visualized using the Sanger Artemis genome browser and annotation tool as previously described (60). A Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine differences in reads corresponding to insertions in intragenic and intergenic regions of the genome.

Western blotting.

Cell lysates from biological triplicates were separated by SDS-PAGE on either 10% or 12% bis-Tris NuPAGE gels in MES (morpholineethanesulfonic acid) or MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) running buffer (Thermo Fisher). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose or polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes with an iBlot dry blotting system or an XCell II blot module (Thermo Fisher). The membranes were blocked overnight with SuperBlock blocking buffer supplemented with 0.25% Surfact-Amps detergent sampler (Thermo Fisher) or Odyssey blocking buffer diluted 1:5 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (LI-COR). Membranes were probed with anti-VSV-G (Sigma) and anti-RNA polymerase (RNAP) alpha subunit (NeoClone) antibodies or anti-PAP (Sigma) and anti-RNA polymerase alpha subunit antibodies. For qualitative Western blot analyses, membranes were then incubated with polyclonal goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin and/or polyclonal goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin, and proteins were detected by use of the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher). For quantitative Western blot analyses, membranes were incubated with near-infrared secondary antibodies, 680LT donkey anti-mouse immunoglobulin, and 800CW donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (LI-COR). Imaging was performed on a LI-COR Odyssey CLx imager, and fluorescence intensity was quantified using Image Studio software (LI-COR). P values were calculated using one-way Student's t test.

Whole-genome sequencing.

A total of 18 large-colony suppressors were selected from isolated single colonies of Δhfq cells streaked on LB agar, and two colonies were selected from isolated single colonies of mexS Q9stop cells streaked on LB agar. For each isolate, a single colony was inoculated in LB and incubated for ∼16 to 24 h at 37°C. Pellets of overnight cultures were collected by centrifugation, and genomic DNA was harvested from cells using a MasterPure DNA purification kit (Epicentre). Sequencing libraries were constructed using a NEBNext Ultra II DNA preparation kit for Illumina (NEB) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. Approximately 50 to 100 ng of genomic DNA was used, and adaptors were diluted 1:10 prior to ligation. Size selection was performed using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) to yield inserts 400 to 500 bp in length, followed by 10 rounds of PCR amplification. Libraries from each strain were pooled, and 50-bp reads were sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 sequencer by Elim Biopharmaceuticals. Reads were trimmed and aligned to the PAO1 genome (GenBank accession number NC_002516). Read processing and data analysis to identify potential mutations were performed using the CLC Workbench package (Qiagen). The Basic Variant Detection tool was used to identify SNPs and small insertion-deletions (InDels), and the InDel and Structural Variants tool was used to identify large deletions and duplications.

Colony size quantitation.

Colony size quantitation was performed on cells plated on LB or NCE-succinate agar plates, where indicated. Agar plates were photographed with a Nikon D3300 camera with an AF-S Micro Nikkor 60-mm 1:2.8 lens at a fixed distance after incubation at 37°C for 48 or 72 h, where indicated. The optical areas of 20 well-isolated colonies on agar plates with <75 colonies were measured using ImageJ software. The colony area was normalized to the average area of Δhfq colonies. Colony size quantitation was performed at least twice on sets of biological duplicates. P values were calculated using one-way Student's t test.

ChIP.

Biological triplicate cultures of wild-type PAO1 and PAO1 MexT-V were grown overnight and backdiluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in 200 ml of LB. The triplicate cultures were grown at 37°C with shaking to mid-log or stationary phase (OD600 = 0.5 or 2.0, respectively). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed as previously described (24) with anti-VSV-G–agarose beads, with wild-type PAO1 serving as the mock control.

ChIP-seq library preparation and sequencing.

Sequencing libraries were constructed with the NEBNext Ultra II DNA library preparation kit for Illumina (NEB) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Approximately 5 ng immunoprecipitated DNA was used, and adaptors were diluted 1:10 prior to ligation. For PAO1 MexT-V and PAO1 (mock control), size selection was performed using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) to yield inserts 500 to 700 bp in length, followed by 8 rounds of PCR amplification. The libraries were sequenced by Elim Biopharmaceuticals (Hayward, CA) on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer producing 50-bp paired-end reads.

ChIP-seq data analysis.

Computational analysis was performed using the open-source Galaxy web server (https://usegalaxy.org/) (62), and paired-end sequencing reads were preprocessed using the FASTQ Groomer tool (63). Reads were trimmed using the Trimmomatic (v0.32) tool (-phred33) (64) and were mapped to the PAO1 genome (GenBank accession number NC_002516) using the bowtie2 (v2.2.6.2) program (65). In order to identify the chromosomal regions to which MexT-V was associated, reads from MexT-V cultures were compared to those for the corresponding wild-type (mock control) samples, and peaks of enriched binding were called from the sorted, aligned BAM files using the MACS (v2.1.0.20151222) program (https://github.com/taoliu/MACS/) (66) and an effective genome size of 6.26 Mbp, a bandwidth of 300 bp, and a false discovery rate (q-value) cutoff of 0.05. Peaks were stored in bedGraph format and considered for further analysis if they (i) were enriched ≥2-fold, (ii) were enriched in at least two of the three biological replicates, and (iii) were statistically significantly enriched (−log10 P value > 2). Enrichment was visualized using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV; v2.3.88) (67, 68). One hundred bases surrounding the summit of each nonredundant enrichment peak were extracted from the PAO1 reference sequence using the summit coordinates generated by the MACS program. A binding motif was computed using nonredundant sequences from these using the MEME program (69, 70), which was compared visually to the motif generated by Tian et al. (36).

Data availability.

Sequencing data are available in the NCBI Bioproject accession number PRJNA531246.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tracy Kambara and other members of the S. L. Dove lab for important discussions, Michael Gebhardt for assistance analyzing the whole-genome sequencing data for mexS mutants, Alan Hauser for providing the PA99 strain, and Ann Hochschild for comments on the manuscript. We also thank Keith Turner for construction of the mexT and mexEF deletion plasmids, as well as design of the mexT expression plasmid. We thank Neil Greene and Thomas Bernhardt for advice and reagents for the Tn-seq experiment.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI125876 and AI105013 (to S.L.D.). I.T.H. was supported by a graduate research fellowship from the NSF (fellowship DGE1745303).

I.T.H. and S.L.D. designed the experiments; I.T.H., T.T., and M.J.D. performed the experiments; I.T.H. and M.J.D. analyzed the data; and I.T.H and S.L.D. wrote the manuscript.

I.T.H. dedicates this paper to the memory of his father, Rodney Hill.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00232-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Emerson J, Rosenfeld M, McNamara S, Ramsey B, Gibson RL. 2002. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other predictors of mortality and morbidity in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 34:91–100. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okamoto K, Gotoh N, Nishino T. 2001. Pseudomonas aeruginosa reveals high intrinsic resistance to penem antibiotics: penem resistance mechanisms and their interplay. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:1964–1971. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.7.1964-1971.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breidenstein EBM, de la Fuente-Núñez C, Hancock R. 2011. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: all roads lead to resistance. Trends Microbiol 19:419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aeschlimann JR. 2003. The role of multidrug efflux pumps in the antibiotic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacteria. Pharmacotherapy 23:916–924. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.7.916.32722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukuda H, Hosaka M, Hirai K, Iyobe S. 1990. New norfloxacin resistance gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 34:1757–1761. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.9.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Join-Lambert OF, Michea-Hamzehpour M, Kohler T, Chau F, Faurisson F, Dautrey S, Vissuzaine C, Carbon C, Pechere J-C. 2001. Differential selection of multidrug efflux mutants by trovafloxacin and ciprofloxacin in an experimental model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute pneumonia in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:571–576. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.2.571-576.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Mansfeld R, de Been M, Paganelli F, Yang L, Bonten M, Willems R. 2016. Within-host evolution of the Dutch high-prevalent Pseudomonas aeruginosa clone ST406 during chronic colonization of a patient with cystic fibrosis. PLoS One 11:e0158106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maseda H, Saito K, Nakajima A, Nakae T. 2000. Variation of the mexT gene, a regulator of the MexEF-OprN efflux pump expression in wild-type strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol Lett 192:107–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sobel ML, Neshat S, Poole K. 2005. Mutations in PA2491 (mexS) promote MexT-dependent mexEF-oprN expression and multidrug resistance in a clinical strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 187:1246–1253. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.4.1246-1253.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juarez P, Broutin I, Bordi C, Plésiat P, Llanes C. 2018. Constitutive activation of MexT by amino acid substitutions results in MexEF-OprN overproduction in clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62:e02445-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02445-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richardot C, Juarez P, Jeannot K, Patry I, Plésiat P, Llanes C. 2016. Amino acid substitutions account for most MexS alterations in clinical nfxC mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:2302–2310. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02622-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westfall LW, Carty NL, Layland N, Kuan P, Colmer-Hamood JA, Hamood AN. 2006. mvaT mutation modifies the expression of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa multidrug efflux operon mexEF-oprN. FEMS Microbiol Lett 255:247–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2005.00075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juarez P, Jeannot K, Plésiat P, Llanes C. 2017. Toxic electrophiles induce expression of the multidrug efflux pump MexEF-OprN in Pseudomonas aeruginosa through a novel transcriptional regulator, CmrA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00585-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00585-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olivas AD, Shogan BD, Valuckaite V, Zaborin A, Belogortseva N, Musch M, Meyer F, Trimble WL, An G, Gilbert J, Zaborina O, Alverdy JC. 2012. Intestinal tissues induce an SNP mutation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa that enhances its virulence: possible role in anastomotic leak. PLoS One 7:e44326. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogel J, Luisi BF. 2011. Hfq and its constellation of RNA. Nat Rev Microbiol 9:578–589. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Storz G, Vogel J, Wassarman KM. 2011. Regulation by small RNAs in bacteria: expanding frontiers. Mol Cell 43:880–891. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sonnleitner E, Bläsi U. 2014. Regulation of Hfq by the RNA CrcZ in Pseudomonas aeruginosa carbon catabolite repression. PLoS Genet 10:e1004440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen J, Gottesman S. 2017. Hfq links translation repression to stress-induced mutagenesis in E. coli. Genes Dev 31:1382–1395. doi: 10.1101/gad.302547.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kavita K, de Mets F, Gottesman S. 2018. New aspects of RNA-based regulation by Hfq and its partner sRNAs. Curr Opin Microbiol 42:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonnleitner E, Hagens S, Rosenau F, Wilhelm S, Habel A, Jäger K-E, Bläsi U. 2003. Reduced virulence of a hfq mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa O1. Microb Pathog 35:217–228. doi: 10.1016/S0882-4010(03)00149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sonnleitner E, Wulf A, Campagne S, Pei XY, Wolfinger MT, Forlani G, Prindl K, Abdou L, Resch A, Allain FHT, Luisi BF, Urlaub H, Bläsi U. 2018. Interplay between the catabolite repression control protein Crc, Hfq and RNA in Hfq-dependent translational regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nucleic Acids Res 46:1470–1485. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sonnleitner E, Schuster M, Sorger-Domenigg T, Greenberg EP, Bläsi U. 2006. Hfq-dependent alterations of the transcriptome profile and effects on quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 59:1542–1558. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pusic P, Tata M, Wolfinger MT, Sonnleitner E, Häussler S, Bläsi U. 2016. Cross-regulation by CrcZ RNA controls anoxic biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci Rep 6:39621. doi: 10.1038/srep39621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kambara TK, Ramsey KM, Dove SL. 2018. Pervasive targeting of nascent transcripts by Hfq. Cell Rep 23:1543–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bai G, Golubov A, Smith EA, McDonough KA. 2010. The importance of the small RNA chaperone Hfq for growth of epidemic Yersinia pestis, but not Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, with implications for plague biology. J Bacteriol 192:4239–4245. doi: 10.1128/JB.00504-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irnov I, Wang Z, Jannetty ND, Bustamante JA, Rhee Y, Jacobs-Wagner C. 2017. Crosstalk between the tricarboxylic acid cycle and peptidoglycan synthesis in Caulobacter crescentus through the homeostatic control of α-ketoglutarate. PLoS Genet 13:e1006978-27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmqvist E, Wright PR, Li L, Bischler T, Barquist L, Reinhardt R, Backofen R, Vogel J. 2016. Global RNA recognition patterns of post-transcriptional regulators Hfq and CsrA revealed by UV crosslinking in vivo. EMBO J 35:991–1011. doi: 10.15252/embj.201593360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ding Y, Davis BM, Waldor MK. 2004. Hfq is essential for Vibrio cholerae virulence and downregulates sigma expression. Mol Microbiol 53:345–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNealy TL, Forsbach-Birk V, Shi C, Marre R. 2005. The Hfq homolog in Legionella pneumophila demonstrates regulation by LetA and RpoS and interacts with the global regulator CsrA. J Bacteriol 187:1527–1532. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.4.1527-1532.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsui HC, Leung HC, Winkler ME. 1994. Characterization of broadly pleiotropic phenotypes caused by an hfq insertion mutation in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Microbiol 13:35–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arce-Rodríguez A, Calles B, Nikel PI, de Lorenzo V. 2016. The RNA chaperone Hfq enables the environmental stress tolerance super-phenotype of Pseudomonas putida. Environ Microbiol 18:3309–3326. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robertson GT, Roop RM. 1999. The Brucella abortus host factor I (HF-I) protein contributes to stress resistance during stationary phase and is a major determinant of virulence in mice. Mol Microbiol 34:690–700. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lenz DH, Mok KC, Lilley BN, Kulkarni RV, Wingreen NS, Bassler BL. 2004. The small RNA chaperone Hfq and multiple small RNAs control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio cholerae. Cell 118:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christiansen JK, Larsen MH, Ingmer H, Søgaard-Andersen L, Kallipolitis BH. 2004. The RNA-binding protein Hfq of Listeria monocytogenes: role in stress tolerance and virulence. J Bacteriol 186:3355–3362. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.11.3355-3362.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozer EA, Allen JP, Hauser AR. 2014. Characterization of the core and accessory genomes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa using bioinformatic tools Spine and AGEnt. BMC Genomics 15:737. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tian Z-X, Fargier E, Mac Aogáin M, Adams C, Wang Y-P, O’Gara F. 2009. Transcriptome profiling defines a novel regulon modulated by the LysR-type transcriptional regulator MexT in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nucleic Acids Res 37:7546–7559. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan J, Huyck M, Hu D, Zelaya RA, Hogan DA, Greene CS. 2017. ADAGE signature analysis: differential expression analysis with data-defined gene sets. BMC Bioinformatics 18:512. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1905-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uwate M, Ichise Y, Shirai A, Omasa T, Nakae T, Maseda H. 2013. Two routes of MexS-MexT-mediated regulation of MexEF-OprN and MexAB-OprM efflux pump expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol Immunol 57:263–272. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin Y, Yang H, Qiao M, Jin S. 2011. MexT regulates the type III secretion system through MexS and PtrC in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 193:399–410. doi: 10.1128/JB.01079-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin AL, Mizoguchi SD, Warrener P, Hickey MJ, Brinkman FSL, Hufnagle WO, Kowalik DJ, Lagrou M, Garber RL, Goltry L, Tolentino E, Westbrock-Wadman S, Yuan Y, Brody LL, Coulter SN, Folger KR, Kas A, Larbig K, Lim R, Smith K, Spencer D, Wong G-S, Wu Z, Paulsen IT, Reizer J, Saier MH, Hancock REW, Lory S, Olson MV. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959–964. doi: 10.1038/35023079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fozo EM, Hemm MR, Storz G. 2008. Small toxic proteins and the antisense RNAs that repress them. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 72:579–589. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00025-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Storz G, Wolf YI, Ramamurthi KS. 2014. Small proteins can no longer be ignored. Annu Rev Biochem 83:753–777. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-070611-102400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hobbs EC, Yin X, Paul BJ, Astarita JL, Storz G. 2012. Conserved small protein associates with the multidrug efflux pump AcrB and differentially affects antibiotic resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:16696–16701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210093109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Köhler T, Van Delden C, Curty LK, Hamzehpour MM, Pechere JC. 2001. Overexpression of the MexEF-OprN multidrug efflux system affects cell-to-cell signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 183:5213–5222. doi: 10.1128/jb.183.18.5213-5222.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Olivares J, Alvarez-Ortega C, Linares JF, Rojo F, Köhler T, Martínez JL. 2012. Overproduction of the multidrug efflux pump MexEF-OprN does not impair Pseudomonas aeruginosa fitness in competition tests, but produces specific changes in bacterial regulatory networks. Environ Microbiol 14:1968–1981. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lamarche MG, Déziel E. 2011. MexEF-OprN efflux pump exports the Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) precursor HHQ (4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline). PLoS One 6:e24310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Häussler S, Becker T. 2008. The Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS) balances life and death in Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000166. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Köhler T, Michéa-Hamzehpour M, Henze U, Gotoh N, Curty LK, Pechère JC. 1997. Characterization of MexE-MexF-OprN, a positively regulated multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 23:345–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2281594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith EE, Buckley DG, Wu Z, Saenphimmachak C, Hoffman LR, D'Argenio DA, Miller SI, Ramsey BW, Speert DP, Moskowitz SM, Burns JL, Kaul R, Olson MV. 2006. Genetic adaptation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:8487–8492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602138103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oshri RD, Zrihen KS, Shner I, Omer Bendori S, Eldar A. 2018. Selection for increased quorum-sensing cooperation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa through the shut-down of a drug resistance pump. ISME J 12:2458–2469. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0205-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Masip L, Veeravalli K, Georgiou G. 2006. The many faces of glutathione in bacteria. Antioxid Redox Signal 8:753–762. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maddocks SE, Oyston P. 2008. Structure and function of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology 154:3609–3623. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022772-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fargier E, Mac Aogain M, Mooij MJ, Woods DF, Morrissey JP, Dobson ADW, Adams C, O'Gara F. 2012. MexT functions as a redox-responsive regulator modulating disulfide stress resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 194:3502–3511. doi: 10.1128/JB.06632-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Laar TA, Esani S, Birges TJ, Hazen B, Thomas JM, Rawat M. 2018. Pseudomonas aeruginosa gshA mutant is defective in biofilm formation, swarming, and pyocyanin production. mSphere 3:e00155-18. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00155-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wongsaroj L, Saninjuk K, Romsang A, Duang-Nkern J, Trinachartvanit W, Vattanaviboon P, Mongkolsuk S. 2018. Pseudomonas aeruginosa glutathione biosynthesis genes play multiple roles in stress protection, bacterial virulence and biofilm formation. PLoS One 13:e0205815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldman SR, Sharp JS, Vvedenskaya IO, Livny J, Dove SL, Nickels BE. 2011. NanoRNAs prime transcription initiation in vivo. Mol Cell 42:817–825. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rohlfing AE, Dove SL. 2014. Coordinate control of virulence gene expression in Francisella tularensis involves direct interaction between key regulators. J Bacteriol 196:3516–3526. doi: 10.1128/JB.01700-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−delta delta C(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goodman AL, Kulasekara B, Rietsch A, Boyd D, Smith RS, Lory S. 2004. A signaling network reciprocally regulates genes associated with acute infection and chronic persistence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Dev Cell 7:745–754. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greene NG, Fumeaux C, Bernhardt TG. 2018. Conserved mechanism of cell-wall synthase regulation revealed by the identification of a new PBP activator in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:3150–3155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717925115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lai GC, Cho H, Bernhardt TG. 2017. The mecillinam resistome reveals a role for peptidoglycan endopeptidases in stimulating cell wall synthesis in Escherichia coli. PLoS Genet 13:e1006934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J, The Galaxy Team . 2010. Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol 11:R86. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blankenberg D, Gordon A, Von Kuster G, Coraor N, Taylor J, Nekrutenko A. 2010. Manipulation of FASTQ data with Galaxy. Bioinformatics 26:1783–1785. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Myers RM, Brown M, Li W, Liu XS. 2008. Model-based analysis of ChIP-seq (MACS). Genome Biol 9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. 2013. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform 14:178–192. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. 2011. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol 29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bailey TL, Elkan C. 1994. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol 2:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, Ren J, Li WW, Noble WS. 2009. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res 37:W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequencing data are available in the NCBI Bioproject accession number PRJNA531246.