Very little is known about TA systems in phytopathogenic bacteria. ecnAB, in particular, has only been studied in bacterial human pathogens. Here, we showed that it is present in a wide range of Xanthomonas sp. phytopathogens; moreover, this is the first work to investigate the functional role of this TA system in Xanthomonas citri biology, suggesting an important new role in adaptation and survival with implications for bacterial pathogenicity.

KEYWORDS: TA system, biofilm, quorum sensing, stress tolerance

ABSTRACT

Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri causes citrus canker disease worldwide in most commercial varieties of citrus. Its transmission occurs mainly by wind-driven rain. Once X. citri reaches a leaf, it can epiphytically survive by forming a biofilm, which enhances the persistence of the bacteria under different environmental stresses and plays an important role in the early stages of host infection. Therefore, the study of genes involved in biofilm formation has been an important step toward understanding the bacterial strategy for survival in and infection of host plants. In this work, we show that the ecnAB toxin-antitoxin (TA) system, which was previously identified only in human bacterial pathogens, is conserved in many Xanthomonas spp. We further show that in X. citri, ecnA is involved in important processes, such as biofilm formation, exopolysaccharide (EPS) production, and motility. In addition, we show that ecnA plays a role in X. citri survival and virulence in host plants. Thus, this mechanism represents an important bacterial strategy for survival under stress conditions.

IMPORTANCE Very little is known about TA systems in phytopathogenic bacteria. ecnAB, in particular, has only been studied in bacterial human pathogens. Here, we showed that it is present in a wide range of Xanthomonas sp. phytopathogens; moreover, this is the first work to investigate the functional role of this TA system in Xanthomonas citri biology, suggesting an important new role in adaptation and survival with implications for bacterial pathogenicity.

INTRODUCTION

Phytopathogenic bacteria such as Xanthomonas spp. cause major damage to many different crops such as brassicas, rice, cassava, tomato, and citrus (1). Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri causes citrus canker disease worldwide in most commercial varieties of citrus (2). For this reason, there has been an increase in the number of works focusing on the identification of genes involved in the mechanisms of pathogenicity and plant-pathogen interaction with the aim of developing strategies to control X. citri (3–8). X. citri is dispersed by wind-driven rain and then adheres to plant leaf surfaces (9). Stable adhesion to the host is the first step toward biofilm formation (10), which enhances the epiphytic persistence of the bacteria on host leaves, plays an important role in the early stages of infection (11), and confers resistance to different environmental stresses, including UV radiation, salt, osmotic challenge, desiccation, and H2O2 (12–14). Strains with mutations in genes involved in biofilm formation are less virulent (15–18), demonstrating that X. citri biofilms are also associated with virulence. Thus, the study of genes involved in biofilm formation has been an important step toward understanding the bacterial strategy of survival and host plant infection.

One of the genetic mechanisms involved in biofilm formation is quorum sensing, which is a refined process of cellular communication (19). Mutations in rpfF genes involved in diffusible signal factor (DSF)-mediated quorum sensing, such as rpfF, rpfG, and rpfC in Xanthomonas, lead to reductions in the synthesis of virulence factors, xanthan gum production, and biofilm development (18, 20, 21). Thus, it is important to understand the genes regulated by quorum sensing since they are directly involved in features allowing bacterial survival and virulence in the host (18). In fact, transcriptome analysis of the rpfF mutant, which is defective in DSF synthesis, revealed a set of genes involved in chemotaxis and motility, adhesion, stress tolerance, regulation, transport, and detoxification (18). Many of these genes have been extensively studied (18, 22, 23); however, there are genes whose functions in X. citri are still unknown. These genes include the components of the ecnAB toxin/antitoxin (TA) system (XAC_RS20190/XAC_RS20185 [GenBank database; genome coordinates 4700807 to 4700959/4700598 to 4700732]), which is known to play an important role in Escherichia coli (24, 25). The E. coli ecnAB locus encodes two small lipoproteins that are considered to be components of the entericidin locus TA system because of hypothesized similarities to a plasmid addiction module, mazEF, that has been studied in E. coli (24). EcnA was identified as the antitoxin that counteracts the EcnB toxin, whose overproduction results in more pronounced bacterial lysis than that observed under coexpression of ecnA and ecnB (25). Different functions have been proposed for the ecnAB TA system, including roles in programmed cell death (24) and adherence to the respiratory tract of humans (26) and a requirement of this system for the probiotic functions of Enterobacter sp. strain C6-6 (25).

In general, TA systems consist of a pair of genes in an operon that encodes a stable toxin and an unstable antitoxin that binds to the toxin and blocks its activity under normal conditions. On the other hand, under stress, the antitoxin is degraded, allowing the toxin to decrease cell growth and metabolism. When normal growth conditions are reestablished, the antitoxin is produced, blocking the toxin and allowing cells to grow (27).

Most of the studies addressing TA systems are related to human-associated bacteria, and only a few have addressed TAs from phytopathogens (28). Indeed, TA systems have been implicated in the induction of persister cells and, consequently, the maintenance of phytopathogen virulence (29). In Xanthomonas, although quantitative and qualitative differences among the type II TA systems have been reported (30), no function of these systems has yet been characterized. In this work, the importance of the ecnAB locus is demonstrated in Xanthomonas for the first time, and we suggest that this locus is involved in the regulation of genes related to biofilm formation, motility, and cell survival, thereby affecting the virulence of the pathogen in the host plant.

RESULTS

ecnA encodes a probable antitoxin.

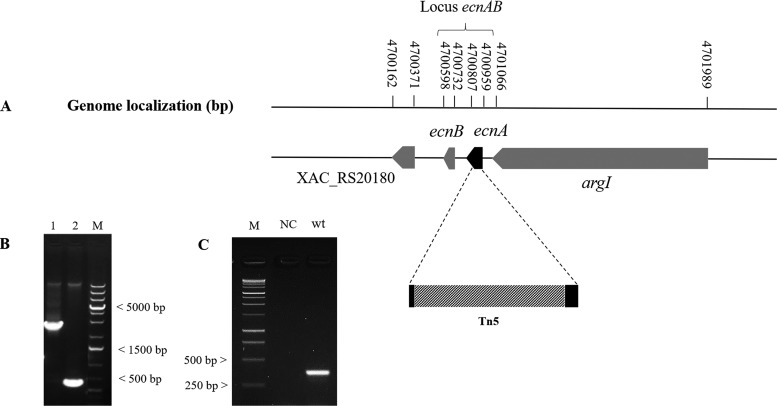

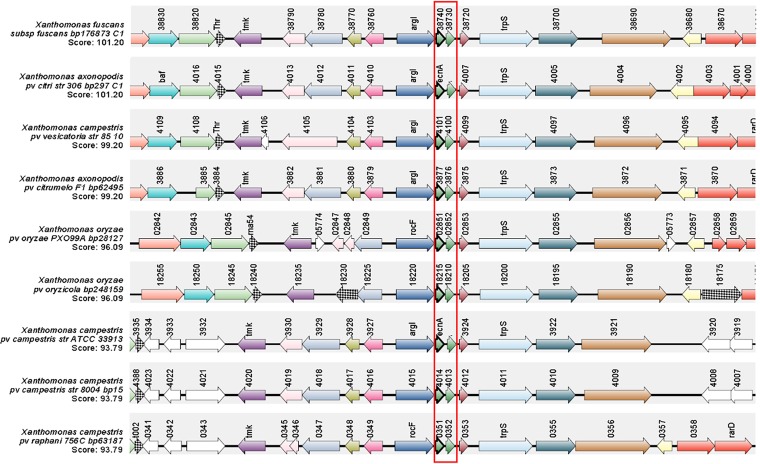

The ecnA mutant (B3) was isolated from an EZ-Tn5 transposon mutagenesis library of X. citri strain 306 (31), which was identified among other strains on the basis of an altered pattern in the formation of biofilms. Sequencing indicated that EZ-Tn5 was inserted between nucleotides 4 and 105 of the XAC_RS20190 locus in the B3 mutant (Fig. 1A). The mutant was designated the ecnA::Tn5 mutant since the transposon insertion was located in the ecnA gene, which encodes a protein with a similar identity to the EcnA protein belonging to the entericidin locus in E. coli. To confirm the insertion, PCR using the ecnA-specific primers Fw (5′-CAGCATTCCCACCGACAACATC-3′) and Rw (5′-GCATGGGGTCGTTGGATATCGT-3′) was carried out and resulted in an amplicon of 0.52 kb when X. citri subsp. citri 306 genomic DNA was used as the template and approximately 2.5 kb when the B3 mutant was used as the template, which corresponded to a genomic fragment of 1.938 kb plus the EZ-Tn5 transposon insertion (Fig. 1B). In silico analysis of the Xanthomonas genomes revealed that ecnA and ecnB constitute a putative operon, as evaluated in DOOR2 (data not shown). To confirm this hypothesis, amplification of a fragment comprising ecnA and ecnB was performed from cDNA of the wild-type strain, proving that these two genes are present in an operon (Fig. 1C). The ecnAB locus is conserved in other Xanthomonas species, including Xanthomonas fuscans subsp. fuscans, Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria, Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris, Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, and Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola (Fig. 2).

FIG 1.

Sequence analysis of the EZ-Tn5 insertion in the ecnA mutant strain. (A) Genomic location of ecnA on the X. citri chromosome showing the transposon insertion site between nucleotides 4 and 105 of ecnA. (B) PCR analysis confirming the insertion of EZ-Tn5 in the ecnA gene. DNA was amplified using the primers ecnA_F and ecnA_R targeting a 500-bp region surrounding ecnA from the wild-type X. citri and B3 strains. Lane 1, X. citri; lane 2, B3 (ecnA::Tn5); M, Invitrogen 1 Kb Plus DNA size marker. (C) PCR analysis from cDNA confirming that ecnAB is located in an operon. cDNA was amplified using the primers ecnA_F and ecnB_R targeting a 350-bp region surrounding the ecnAB operon from the wild type X. citri. M, Promega 1kb DNA ladder; NC, negative control; wt, X. citri cDNA.

FIG 2.

Synteny of the ecnAB locus. Genomic regions of different Xanthomonas spp. were aligned on the basis of the ecnAB locus, which is highlighted in red. Synteny analysis was performed using the SyntTax bioinformatics tool built with the Absynte algorithm (http://archaea.u-psud.fr/synttax/) (50) using nine Xanthomonas genomes as a reference. The synteny results show that the ecnAB locus is conserved among Xanthomonas species.

The ecnAB locus is regulated by X. citri quorum sensing and affects biofilm formation.

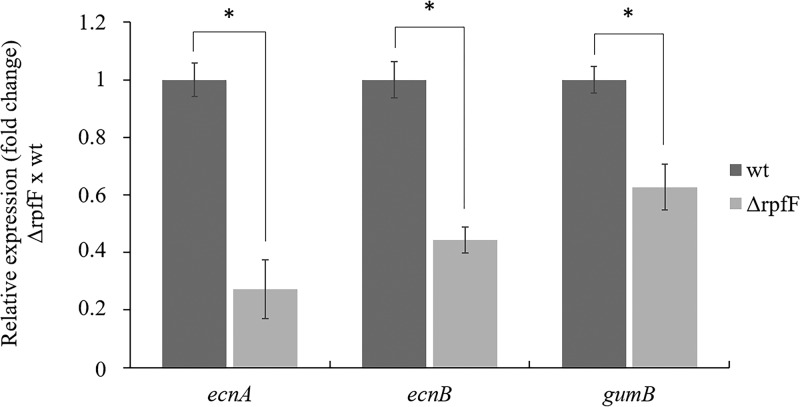

ecnA transcription is regulated by quorum sensing (18). To confirm the effect of quorum-sensing regulatory components on the expression of the X. citri ecnAB system, we evaluated its expression in the rpfF mutant background, in which no DSF is produced (18). gumB was used as a control since it is known to be positively regulated by RpfF (32). We verified that both ecnA and ecnB were downregulated in the rpfF mutant (Fig. 3). These results confirm that RpfF positively regulates the ecnAB system. To assess the role of EcnA in biofilms, we measured their development on abiotic and biotic surfaces. Intriguingly, in contrast to what was observed for the rpfF mutant, significantly less biofilm formation was observed for the ecnA mutant on abiotic and biotic surfaces (Fig. 4). Taken together, the results show that even though ecnAB is regulated by rpfF, the ecnA and rpfF mutants exhibit different behavior regarding biofilm formation, indicating that other components may play a role in this phenotype. With the aim of clarifying the effects of the mutation, we constructed a clean ecnA deletion mutant, and no difference in biofilm formation was observed in either mutant background.

FIG 3.

Gene expression analysis of ecnAB in the rpfF mutant strain. Relative expression of the ecnA, ecnB, and gumB genes in the rpfF mutant compared to the wild-type strain. gumB was used as a control that is positively regulated by RpfF. Transcript abundance was determined by real-time RT-qPCR. Data are shown as the mean of three independent biological replicates, and error bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean. 16S rRNA was used as an endogenous control. *, significant difference (P < 0.05); ns, no significant difference.

FIG 4.

Biofilm formation by the X. citri wild-type, ecnA::Tn5, ΔecnA, ecnA::Tn5_c, and ΔrpfF strains. Biofilms formed on abiotic (A) and biotic (C) surfaces were stained with crystal violet and quantified at an OD of 590 nm (B and D). The values in panel B were normalized to bacterial growth (OD at 600 nm). The picture of leaves is representative of six independent replicates. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of five replicates. *, significant difference (P < 0.05) compared with the wild-type strain.

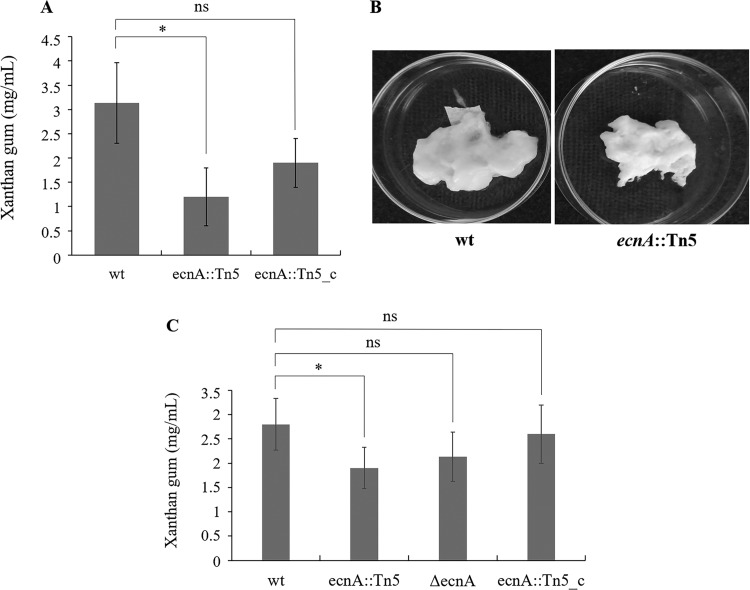

ecnA is involved in X. citri polysaccharide production and sliding motility.

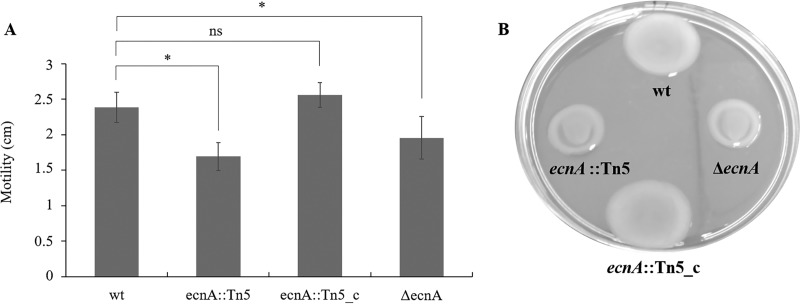

Because of the significant effect of ecnA on biofilm formation, we evaluated whether this characteristic was an effect of the alteration of exopolysaccharide production. Indeed, a significant reduction in exopolysaccharide (EPS) was observed in the ecnA mutant (Fig. 5A and C), with a lower content of crude xanthan gum (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that the reduced biofilm formation observed in the ecnA mutant could be related to the altered production of EPS. In addition to the participation of EPS in biofilms, EPS also plays a role in movement via sliding motility (11). Indeed, the ecnA mutants showed a significantly reduced diameter of sliding motility compared to the wild-type and ecnA::Tn5_c strains (Fig. 6). Swimming analyses were also performed, but no difference was observed between the mutant and wild-type strains (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Growth curve assays were performed, and no difference was observed between the strains (Fig. S1B), indicating that the difference observed in the motility assays was not related to growth.

FIG 5.

Effect of ecnA mutation on xanthan gum production. (A) Xanthan gum production by the wild type (wt), ecnA::Tn5 mutant, and complemented (ecnA::Tn5_c) strains. (B) Crude xanthan gum from the wild type and dried xanthan from the ecnA mutant. (C) Xanthan gum production by the wild type (wt), ecnA::Tn5 and ΔencA mutant, and complemented (ecnA::Tn5_c) strains. The data are the means of triplicate measurements from a representative experiment; similar results were obtained in two other independent experiments. *, significant difference (P < 0.05); ns, no significance. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean.

FIG 6.

Effect of wild-type (wt), ecnA::Tn5, complemented (ecnA::Tn5_c), and ΔecnA strains on sliding motility. (A) Diameters of cell sliding on plates. *, significant difference (P < 0.05); ns, no significant difference. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean. (B) ecnA::Tn5 and ΔecnA strains showed a decrease in motility that could be restored to wild-type levels by the introduction of a plasmid containing the intact ecnA gene. Cells from bacterial cultures at the exponential stage were spotted on SB plates supplemented with 0.5% agar. The plates were incubated at 28°C and photographed after 2 days.

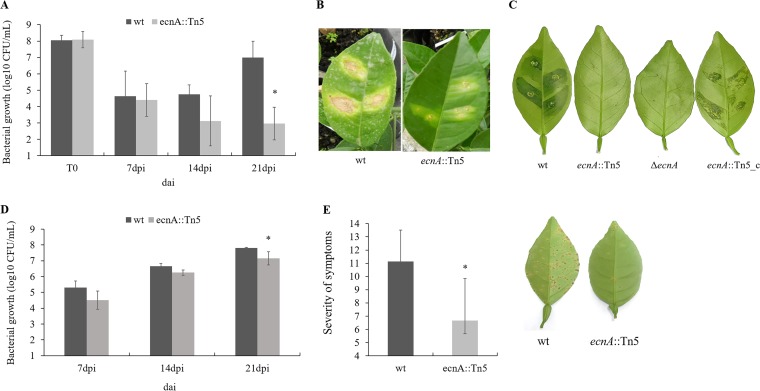

ecnA is involved in virulence and bacterial survival in plant hosts.

The pathogenicity of the ecnA mutant was evaluated by infiltration and spraying in the host plants. The bacterial population of the ecnA mutant in infiltrated leaves was significantly smaller than that of the wild type at 21 days after inoculation (dai) (Fig. 7A), showing a 5-log-unit difference. In addition, the symptoms were clearly reduced compared to those of the leaves infiltrated with the wild-type strain (Fig. 7B), which was also observed in the ΔecnA mutant (Fig. 7C) and was restored using the ecnA-complemented strain in detached leaves (Fig. 7C).

FIG 7.

Bacterial growth and pathogenicity assay in planta. (A) Populations of wild-type and ecnA::Tn5 bacteria inoculated by infiltration at a concentration of 108 CFU/ml and analyzed at 7, 14, and 21 days after inoculation (dai). (B) Symptoms of sweet orange leaves infiltrated with the wild type and the ecnA::Tn5 strain at 21 dai. (C) Symptoms of sweet orange detached leaves infiltrated with wild-type, ecnA::Tn5, ΔecnA, and ecnA::Tn5_c strains at 14 dai. (D) Populations of the wild type and ecnA::Tn5 mutant bacteria inoculated by spraying at a concentration of 108 CFU/ml and analyzed at 7, 14, and 21 dai. (E) Severity of citrus canker symptoms at 21 dai. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean of two independent experiments. *, significant difference (P < 0.05). Images are representative of five independent replicates.

When both bacteria were inoculated by spraying, the ecnA mutant population was also significantly smaller than that of the wild type at 21 dai (Fig. 7D), resulting in a significant difference in symptom severity in leaves (Fig. 7E). As ecnA is part of a TA system and may be associated with tolerance to stress conditions (24, 33), we speculated that the smaller bacterial population of the ecnA mutant observed in plants could be due to reduced tolerance to the plant defense response, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) production.

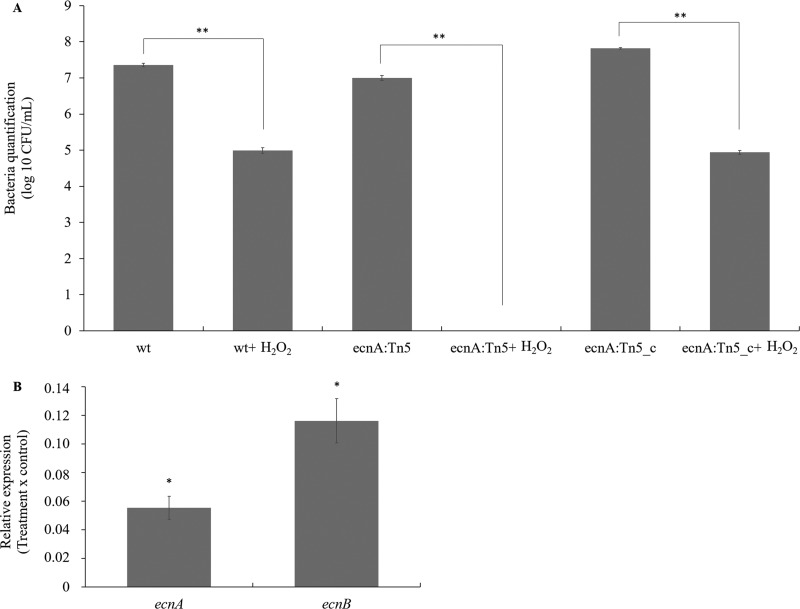

ecnA is involved in bacterial survival during oxidative stress.

Bacterial populations were analyzed under ROS stress induced by hydrogen peroxide. The number of wild-type and ecnA+ cells was significantly reduced (approximately 2 logs) after treatment (Fig. 8A), but the effect was much stronger for the ecnA mutant, for which no cultivable cells were recovered after the stress treatment. In addition, the relative expression of ecnA and ecnB was significantly repressed at high concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (50 mM) (Fig. 8B). These results are similar to previously published data on toxin-antitoxin systems in X. citri, showing that most stressor agents indeed repress the toxin-antitoxin systems in these bacteria (30). Taken together, these results suggest that the smaller population of ecnA mutants observed in the leaves could be a consequence of a reduced ability to cope with plant defense responses.

FIG 8.

Sensitivity of the X. citri wild-type, ecnA::Tn5, and ecnA::Tn5_c strains to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). (A) Bacterial quantification before and after H2O2 stress. (B) Relative expression of ecnA and ecnB in X. citri after H2O2 stress compared to cells without stress. The transcript abundance was determined by RT-qPCR. Data are shown as the means of two independent biological experiments and three technical replicates. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean. 16S rRNA was used as an endogenous control. *, significant difference at P < 0.05; **, significant difference at P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The ecnAB locus encodes two small peptides, EcnA and EcnB (Fig. 1), and has been considered a toxin-antitoxin system in E. coli because of similarities to the plasmid addiction module mazEF (24). Sequences such as ecnAB have been annotated in Xanthomonas genomes (Fig. 2), indicating that this operon may play a conserved role. In E. coli, different functions have been proposed for the ecnAB TA system, including programmed cell death (24) and adherence in the respiratory tract of humans (26). In Xanthomonas, it has been demonstrated that ecnAB is regulated by quorum sensing (18). Indeed, our data showed that ecnA and ecnB were downregulated in the rpfF deletion mutant (Fig. 3), corroborating the transcriptome assay performed for regulatory analysis of the quorum-sensing system in X. citri (18). Curiously, the biofilm formation phenotypes of the ecnA and rpfF mutants differ: while the ecnA mutation leads to reduced biofilm production, the rpfF mutant increases biofilm production. These opposing phenotypes are also observed for gumB since the mutant also produces less biofilm even though it is positively regulated by rpfF (32, 34). These results could be explained by negative regulation of adhesion proteins by rpfF in Xanthomonas (18), and mutation of this gene would therefore lead not only to a decrease in the expression of gumB and ecnA but also to an increase in genes related to adhesion. These adhesion genes are responsible for increased biofilm production, which may not be under the regulation of ecnA or gumB, thus potentially explaining the contrasting phenotypes observed in these genetic backgrounds.

Our results suggest that the correlation of ecnA and biofilm formation occurs due to EPS production, as the ecnA mutant presents less biofilm and EPS production (Fig. 4 and 5). Additionally, the ecnA mutant showed decreased sliding motility on the medium surface (Fig. 6), which could affect bacterial epiphytic growth and, consequently, pathogenicity. It has been demonstrated that inefficiency of epiphytic growth leads to less virulent behavior of X. citri (11, 35), which could explain the observed difference in symptom development when the bacteria were sprayed but not when they were infiltrated (Fig. 7). Fewer symptoms were also observed after infiltration of the bacteria, which suggests that the role of ecnA is not only associated with better fitness of epiphytic behavior but could also be involved in tolerance to plant defense responses. These phenotypes were observed in the ΔecnA mutant as well, which together with the ecnA::Tn5 mutant complemented by overexpression of ecnA alone, proved that the results regarding biofilm formation and pathogenicity were related to a mutation in ecnA and not ecnB. In addition, the ecnA::Tn5 mutant showed significant downregulation of ecnB compared to the wild type, which was not observed in the ΔecnA mutant, reinforcing the role of ecnA in the phenotypes (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Bursts of ROS are quickly produced as a defense response to pathogen attack (36). Indeed, the ecnA::Tn5 mutant presented higher susceptibility to H2O2 (Fig. 8A), which may explain the decrease in symptoms observed when the mutant was infiltrated, together with a reduction in the cell population.

We showed that the ecnA and ecnB genes were downregulated under hydrogen peroxide stresses (Fig. 8B). Similarly, the XACa0028/XACa0027 and chpBS TA systems are significantly downregulated by copper and temperature stresses in X. citri (30). The transcriptional repression of TAs under stress conditions suggests that the amount of unstable antitoxin in the cell decreases, and the stable toxin is then free and active (27, 37). The reasons for such repression are still elusive, but there is a possibility that it is involved in persister cell formation, a phenotype recently explored in phytopathogens, and is implicated in environmental stress survival (38).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids employed in this study are described in Table 1. E. coli DH5α cells were routinely grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (1% [wt/vol] tryptone, 0.5% [wt/vol] yeast extract, and 1% [wt/vol] sodium chloride, pH 7.5) with shaking at 180 rpm or on plates. X. citri subsp. citri strain 306 (39) and derivatives were grown at 28°C in nutrient broth-yeast extract (NBY) nutrient medium (0.5% [wt/vol] peptone, 0.3% [wt/vol] meat extract, 0.2% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 0.2% [wt/vol] K2HPO4, 0.05% [wt/vol] KH2PO4, pH 7.2) with shaking at 180 rpm or on 1.2% (wt/vol) agar solid medium. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: 100 μg/ml ampicillin (Ap), 50 μg/ml kanamycin (Km), and 5 μg/ml gentamicin (Gm).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Characteristic(s)a | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli Dh5α | F− ϕ80dlacZhM15 h (lacZYA-argF)U169 endA1 deoR recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) phoA supE44 λ− thi-1 gyrA96 | 51 |

| Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri 306 (X. citri) | Syn. X. axonopodis pv. citri strain 306; wild type, Apr | 39, 52 |

| B3/ecnA::Tn5 (ecnA mutant) | ecnA mutant (XAC_RS20190), Kmr | 31 |

| ecnA::Tn5_c strain (ecnA+) | ecnA+ (contained in pUFR053, Kmr Gmr) | This study |

| ΔrpfF strain (rpfF-negative strain) | ΔrpfF (XAC_RS09555) Apr | This study |

| ΔecnA strain (ecnA-negative strain) | ΔecnA (XAC_RS20190) Apr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pNPTS138 | Suicide vector for generation of gene knockouts, sacB and Kmr | 41 |

| pNPTS-rpfF | pNPTS138 derivative for generation of rpfF knockout, sacB and Kmr | This study |

| pNPTS-ecnA | pNPTS138 derivative for generation of ecnA knockout, sacB and Kmr | This study |

| pUFR053 | IncW Mob+ mob(P) lacZα+ Par+ Cmr Gmr Kmr, shuttle vector | 43 |

| p53_ecnA | ecnA gene cloning on pUFR053 | This study |

Apr, Kmr, and Gmr indicate resistance to ampicillin, kanamycin, and gentamicin, respectively.

Molecular biology.

Bacterial genomic and plasmid DNA were isolated using a Wizard genomic DNA purification kit and a Wizard miniprep DNA purification system according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). The concentration and purity of the DNA were determined by using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). PCR and DNA electrophoresis were performed as described previously (40) with Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI). Restriction digestions and DNA ligations were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (New England BioLabs, USA).

In-frame deletion of rpfF and ecnA.

To construct rpfF and ecnA deletion mutants, approximately 1 kb of the upstream and downstream regions of both rpfF (XAC_RS09555) and ecnA (XAC_RS20190) was amplified by PCR from X. citri genomic DNA. The primers used to amplify the fragments are listed in Table 2. Fragments were ligated to produce an in-frame deletion. Fragments containing in-frame deletions of rpfF and ecnA were then cloned into the HindIII/BglII and HindIII restriction sites of the pNPTS138 suicide vector, thus generating the constructs pNPTS-rpfF and pNPTS-ecnA, respectively. These constructs were introduced into X. citri cells by electroporation, and the wild-type copy was replaced by the deleted version after two recombination events as described previously (41).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequencesa (5′–3′) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| 16S | F, CCGGATTGGAGTCTGCAACT; R, ACGTATTCACCGCAGCAAT | 53 |

| gumB | F, GACCGAAATCGAGAAGGGCA; R, GCCACACCATCACAAGAGGA | This study |

| ecnB | F, CTGCGTCTTCCACCTTCTCG; R, TGAAGCGTGCAATTGTGCTG | This study |

| ecnA | F, ATGAAGCGACTGCTGACAC; R, GCACTTACCGTCGCTGCAT | This study |

| rpfF(1) | F, TGAGCAAGCTTCCGCGCGACATGCCAGGTTTCG; R, TCGTGCTCCATGGGTTTGATCCTGGTAAGGCCGCG | This study |

| rpfF(2) | F, TGCGCGTCGGCCATGGGCGTCGCTGATTTTTGAT; R, TGCAGGATGCCGACACCACCGCCAGATCTCCGG | This study |

| encA(1) | F, GGCTGGCGCCAAGCTTCGTTTGCTCGCACTGTTCAGTAC; R, GGATCCCAGTGTCAGCAGTCGCTTCATCGC | This study |

| ecnA(2) | F, GACACTGGGATCCTGATCCGTCACATCGCGTGGTCT; R, TCCTGCAGAGAAGCTTGTCAGCAACCACATCAACTCGGTG | This study |

| ecnA_p53 | F, TCGAAGCTTCAGCGAATGCAGGTGTTC; R, GCGATGTGACGGATCAGCGAATTCCTG | This study |

F, forward; R, reverse.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR of quorum-sensing regulated genes.

To verify whether RpfF is involved in the regulation of ecnAB, a quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) assay was performed using the rpfF deletion mutant. RNA extraction from the wild-type and rpfF mutant strains was performed using the RNeasy plant minikit (Qiagen), and RNA quality and concentrations were assessed by gel electrophoresis and with a NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific), respectively. cDNA was synthesized with the GoScript reverse transcription system (Promega), and quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using GoTaq SYBR green (Promega) following the manufacturer’s instructions in a 7500 fast real-time PCR system (Applied), and the output data were analyzed by fold change calculation (2−ΔΔCT). Gene expression was estimated using primers for the genes of the ecnAB locus. gumB was used as a control since it is negatively regulated by rpfF, and 16S rRNA was used as the endogenous control for the ΔΔCT calculation (Table 2). Three independent experiments were performed, and the statistical significance of the means was calculated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

Construction of the complementation vector p53_ecnA.

To complement the ecnA::Tn5 mutant, a 2,000-bp DNA fragment containing the entire ecnA gene (153 bp) plus approximately 1,850 bp of the promoter region was amplified by PCR using total DNA obtained from the X. citri wild-type strain 306 as the template and the specific primer pair ecnA_p53_F and ecnA_p53_R (Table 2). This promoter was the only region identified in BPROM (42) immediately upstream of ecnA. The PCR-amplified fragment was digested with HindIII and EcoRI at the recognition sites designed in the primer sequences, and this processed fragment was ligated into pUFR053 (43), resulting in p53_ecnA (Table 1). The construct was confirmed using sequencing, and the plasmid was transfected into the ecnA::Tn5 strain using electroporation. The cells were selected on NBY solid medium using gentamicin, resulting in the ecnA::Tn5_c strain (ecnA+).

Biofilm formation assays.

Biofilm formation on polystyrene (Nunc 96-well plates) and glass surfaces was examined as described previously (44) with some modifications. The wild-type, mutant, and complemented cells were grown in NBY overnight at 28°C with shaking (180 rpm). The optical density (OD) at 600 nm was adjusted to 0.1 (UV-visible [UV-Vis] spectrometer Lambda Bio; Perkin Elmer) using fresh NBY plus 1.0% (wt/vol) d-glucose. A 200-μl aliquot of the adjusted bacteria was added to each well of a 96-well plate, and a 1.5-ml aliquot of the adjusted bacteria was transferred to a glass tube, after which both were incubated at 28°C without agitation. After 48 h, bacterial growth was checked, and the culture was removed using a pipette. After three washes with water, the adhered cells were stained with 0.1% (wt/vol) crystal violet (CV) for 30 min at room temperature. The unbound stain was removed by washing two times with water, and the CV-stained cells were solubilized in ethanol. The samples on plates were quantified at 590 nm using a microplate reader 3550 (Bio-Rad), and the result was normalized to bacterial growth (OD = 600 nm). Both tests were repeated three times independently with six replicates each. The means were statistically analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

Assays of biofilm formation on leaf surfaces were performed as previously described (45), with some modifications. Briefly, 20 μl of each bacterial suspension (104 CFU/ml) was dropped onto the leaf abaxial surface of sweet orange leaves. The leaves were then maintained at 28°C in a humidified chamber. Biofilm formation was visualized on the leaf surfaces using crystal violet staining. Leaf discs were excised from stained spots, dissolved in 1 ml ethanol-acetone (70:30, vol/vol) and quantified by measuring the optical density at 590 nm. Data from both experiments were statistically analyzed using ANOVA and Tukey’s test (P < 0.05), and values are expressed as the means ± standard deviations.

EPS quantification.

The bacterial strains were cultivated overnight in NBY medium at 28°C with shaking at 200 rpm. The optical density (OD) at 600 nm was adjusted to 0.05 (UV-Vis spectrometer Lambda Bio; Perkin Elmer) using fresh NBY plus 1.0% (wt/vol) d-glucose. After 72 h, the cells were pelleted by centrifugation (4,456 × g for 6 min). The supernatant was transferred to another tube, and 5 volumes of 100% ethanol were added. The crude xanthan was collected using a glass rod and placed in a petri dish to dry at 60°C for 48 h. The dried xanthan was weighed, and the values were expressed as the means ± standard deviations. Data were statistically analyzed using ANOVA and Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

Motility assays.

Motility assays were performed as previously described (35). Bacteria were grown overnight in NBY medium, and 3 μl of bacterial culture (OD600 of 0.3) was then spotted onto a plate containing Silva-Buddenhagen (SB) medium plus 0.5% (wt/vol) agar (Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ) (46) for the sliding motility tests or nutrient-yeast-glycerol broth (NYGB) medium plus 0.25% (wt/vol) agar (47) for the swimming motility tests. Plates were incubated at 28°C for 48 h. The diameters of the circular halos occupied by the strains were measured, and the resulting values were taken to indicate the motility of the X. citri strains. The experiments were repeated three times with three replicates each time. The diameter measurements were statistically analyzed using ANOVA and Tukey’s test (P < 0.05), and the values are expressed as the means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments.

Pathogenicity assay.

Bacteria were grown in NBY medium containing appropriate antibiotics overnight at 28°C and then centrifuged at 4,456 × g and resuspended in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Immature leaves from sweet orange (Citrus sinensis cv. Bahia) plants were inoculated with the bacterial suspensions by spraying or injection into the intercellular spaces of leaves with a needleless syringe (108 CFU/ml). Phosphate buffer was used as the control in noninfected plants. Five plants were inoculated with each bacterial strain via each inoculation method. The plants were kept in the greenhouse at Fazenda Santa Elisa of the Instituto Agronômico de Campinas/IAC (Campinas, SP, Brazil) at a temperature of 28 ± 4°C under high humidity for 30 days. At 7, 14, 21, and 30 days postinoculation, three leaves with similar sizes were randomly collected from three different plants. To evaluate the spray assay, the leaves were immersed in 10 ml of phosphate buffer in Falcon flasks (50 ml). Bacterial cells were collected and then vortexed for 3 min to homogenize the specimen. In the infiltration assay, leaf discs (0.8 cm in diameter) that were randomly selected from the inoculated leaves were ground in 1 ml of phosphate buffer. Bacterial numbers were determined in serial dilutions of the suspensions, and the bacteria were then plated on NBY medium with appropriate antibiotics. Colonies were counted after 48 h of incubation at 28°C. Disease symptom severity was evaluated at 7, 14, 21, and 30 days after inoculation by three independent evaluators following the diagrammatic scale for citrus canker disease (48). Two independent experiments were performed. Statistical significance among the means was calculated with ANOVA and Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

Induction of oxidative stress.

Cells were grown overnight in NBY medium at 28°C with shaking at 180 rpm. The optical density (OD) at 600 nm was adjusted to 0.05 (UV-Vis spectrometer Lambda Bio; Perkin Elmer) using fresh NBY. At this point, 1-ml aliquots were added to 1.5-ml plastic tubes, which were supplemented with hydrogen peroxide to a 50 mM concentration. This concentration was chosen to induce oxidative stress in E. coli (49). These cells were maintained under this stress for 10 min at approximately 28°C without agitation. RNA extraction, RNA quality, cDNA synthesis, and qPCR were performed as described above. Relative expression was evaluated via the 2–ΔΔCT method using 16S gene expression as an endogenous control (Table 2). The experiment was performed with three biological replicates, and statistical significance among the means was calculated using ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test (P < 0.05).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a research grant from INCT Citrus (Proc. CNPQ 465440/2014-2 and FAPESP 2014/50880-0) and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP 2013/10957-0). L. M. Granato was a Ph.D. student from the Program in Genetics and Molecular Biology at the Institute of Biology at the State University of Campinas supported by a fellowship from CAPES/PSDE (99999.002657/2014–07) and is currently supported by a postdoctoral fellowship (FAPESP 2019/01901-8). P. M. M. Martins and M. D. O. Andrade are postdoctoral fellows (FAPESP 2016/01273-9 and 2017/18570-9, respectively). M. A. Takita, M. A. Machado, and A. A. de Souza are recipients of research fellowships from CNPq.

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00796-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fuente LDL, Saul B. 2011. Pathogenic and beneficial plant-associated bacteria, p 44 In Lal R. (ed), Encyclopedia of life support systems (EOLSS). EOLSS Publishers, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham JH, Gottwald TR, Cubero J, Achor DS. 2004. Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri: factors affecting successful eradication of citrus canker. Mol Plant Pathol 5:1–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2004.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duan S, Jia H, Pang Z, Teper D, White F, Jones J, Zhou C, Wang N. 2018. Functional characterization of the citrus canker susceptibility gene CsLOB1. Mol Plant Pathol 19:1908–1916. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia H, Zhang Y, Orbovic V, Xu J, White F, Jones J, Wang N. 2017. Genome editing of the disease susceptibility gene CsLOB1 in citrus confers resistance to citrus canker. Plant Biotechnol J 15:817–823. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorenzoni ASG, Dantas GC, Bergsma T, Ferreira H, Scheffers DJ. 2017. Xanthomonas citri MinC oscillates from pole to pole to ensure proper cell division and shape. Front Microbiol 8:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savietto A, Polaquini CR, Kopacz M, Scheffers DJ, Marques BC, Regasini LO, Ferreira H. 2018. Antibacterial activity of monoacetylated alkyl gallates against Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. Arch Microbiol 200:929–937. doi: 10.1007/s00203-018-1502-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pereira ALA, Carazzolle MF, Abe VY, de Oliveira MLP, Domingues MN, Silva JC, Cernadas RA, Benedetti CE. 2014. Identification of putative TAL effector targets of the citrus canker pathogens shows functional convergence underlying disease development and defense response. BMC Genomics 15:157. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Picchi SC, Takita MA, Coletta-Filho HD, Machado MA, de Souza AA. 2015. N-acetylcysteine interferes with the biofilm formation, motility and epiphytic behaviour of Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. Plant Pathol 65:561–569. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pradhan BB, Ranjan M, Chatterjee S. 2012. XadM, a novel adhesin of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, exhibits similarity to Rhs family proteins and is required for optimum attachment, biofilm formation, and virulence. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 25:1157–1170. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-02-12-0049-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottig N, Garavaglia BS, Garofalo CG, Orellano EG, Ottado J. 2009. A filamentous hemagglutinin-like protein of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri, the phytopathogen responsible for citrus canker, is involved in bacterial virulence. PLoS One 4:e4358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rigano LA, Siciliano F, Enrique R, Sendín L, Filippone P, Torres PS, Qüesta J, Dow JM, Castagnaro AP, Vojnov AA, Marano MR. 2007. Biofilm formation, epiphytic fitness, and canker development in Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 20:1222–1230. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-10-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, Wang N. 2012. The gpsX gene encoding a glycosyltransferase is important for polysaccharide production and required for full virulence in Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. BMC Microbiol 12:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nanda AK, Andrio E, Marino D, Pauly N, Dunand C. 2010. Reactive oxygen species during plant-microorganism early interactions. J Integr Plant Biol 52:195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prakash B, Veeregowda BM, Krishnappa G. 2003. Biofilms: a survival strategy of bacteria. Curr Sci 85:1299–1307. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo Y, Sagaram US, Kim J, Wang N. 2010. Requirement of the galU gene for polysaccharide production by and pathogenicity and growth in planta of Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:2234–2242. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02897-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Wang N. 2011. Genome-wide mutagenesis of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri reveals novel genetic determinants and regulation mechanisms of biofilm formation. PLoS One 6:e21804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan Q, Hu X, Wang N. 2012. The novel virulence-related gene nlxA in the lipopolysaccharide cluster of Xanthomonas citri ssp. citri is involved in the production of lipopolysaccharide and extracellular polysaccharide, motility, biofilm formation and stress resistance. Mol Plant Pathol 13:923–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00800.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo Y, Zhang Y, Li JL, Wang N. 2012. DSF-mediated quorum sensin plays a central role in coordinating gene expression of Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. MPMI 25:165–179. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-07-11-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waters CM, Bassler BL. 2005. Quorum sensing: cell-to-cell communication in bacteria. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 21:319–346. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.131001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barber CE, Tang JL, Feng JX, Pan MQ, Wilson TJ, Slater H, Dow JM, Williams P, Daniels MJ. 1997. A novel regulatory system required for pathogenicity of Xanthomonas campestris is mediated by a small diffusible signal molecule. Mol Microbiol 24:555–566. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3721736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Torres PS, Malamud F, Rigano LA, Russo DM, Marano MR, Castagnaro AP, Zorreguieta A, Bouarab K, Dow JM, Vojnov AA. 2007. Controlled synthesis of the DSF cell-cell signal is required for biofilm formation and virulence in Xanthomonas campestris. Environ Microbiol 9:2101–2109. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01332.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andrade MO, Alegria MC, Guzzo CR, Docena C, Rosa MCP, Ramos CHI, Farah CS. 2006. The HD-GYP domain of RpfG mediates a direct linkage between the Rpf quorum-sensing pathway and a subset of diguanylate cyclase proteins in the phytopathogen Xanthomonas axonopodis pv citri. Mol Microbiol 62:537–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao Y, Qian G, Yin F, Fan J, Zhai Z, Liu C, Hu B, Liu F. 2011. Proteomic analysis of the regulatory function of DSF-dependent quorum sensing in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzicola. Microb Pathog 50:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bishop RE, Leskiw BK, Hodges RS, Kay CM, Weiner JH. 1998. The entericidin locus of Escherichia coli and its implications for programmed bacterial cell death. J Mol Biol 280:583–596. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schubiger CB, Orfe LH, Sudheesh PS, Cain KD, Shah DH, Call DR. 2015. Entericidin is required for a probiotic treatment (Enterobacter sp. strain C6-6) to protect trout from cold-water disease challenge. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:658–665. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02965-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Vries SPW, Eleveld MJ, Hermans PWM, Bootsma HJ. 2013. Characterization of the molecular interplay between Moraxella catarrhalis and human respiratory tract epithelial cells. PLoS One 8:e72193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayes F. 2003. Toxins-antitoxins: plasmid maintenance, programmed cell death, and cell cycle arrest. Science 301:1496–1499. doi: 10.1126/science.1088157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee MW, Rogers EE, Stenger DC. 2012. Xylella fastidiosa plasmid-encoded PemK toxin is an endoribonuclease. Phytopathology 102:32–40. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-05-11-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martins PMM, Merfa MV, Takita MA, De Souza AA. 2018. Persistence in phytopathogenic bacteria: do we know enough? Front Microbiol 9:1099. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martins PMM, Machado MA, Silva NV, Takita MA, de Souza AA. 2016. Type II toxin-antitoxin distribution and adaptive aspects on Xanthomonas genomes: focus on Xanthomonas citri. Front Microbiol 7:652. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baptista JC, Machado MA, Homem RA, Torres PS, Vojnov AA, do Amaral AM. 2010. Mutation in the xpsD gene of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri affects cellulose degradation and virulence. Genet Mol Biol 33:146–153. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572009005000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He YW, Xu M, Lin K, Ng YJA, Wen CM, Wang LH, Liu ZD, Zhang HB, Dong YH, Dow JM, Zhang LH. 2006. Genome scale analysis of diffusible signal factor regulon in Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris: identification of novel cell-cell communication-dependent genes and functions. Mol Microbiol 59:610–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Segura A, Auffret P, Bibbal D, Bertoni M, Durand A, Jubelin G, Kérourédan M, Brugère H, Bertin Y, Forano E. 2018. Factors involved in the persistence of a Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157: H7 strain in bovine feces and gastro-intestinal content. Front Microbiol 9:375. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kakkar A, Nizampatnam NR, Kondreddy A, Pradhan BB, Chatterjee S. 2015. Xanthomonas campestris cell-cell signalling molecule DSF (diffusible signal factor) elicits innate immunity in plants and is suppressed by the exopolysaccharide xanthan. J Exp Bot 66:6697–6714. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Granato LM, Picchi SC, de O Andrade M, Takita MA, de Souza AA, Wang N, Machado MA. 2016. The ATP-dependent RNA helicase HrpB plays an important role in motility and biofilm formation in Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. BMC Microbiol 16:55. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0655-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang P, Lee Y, Igo MM, Roper MC. 2017. Tolerance to oxidative stress is required for maximal xylem colonization by the xylem-limited bacterial phytopathogen, Xylella fastidiosa. Mol Plant Pathol 18:990–1000. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wen Y, Behiels E, Devreese B. 2014. Toxin-antitoxin systems: their role in persistence, biofilm formation, and pathogenicity. Pathog Dis 70:240–249. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merfa MV, Niza B, Takita MA, De Souza AA. 2016. The MqsRA toxin-antitoxin system from Xylella fastidiosa plays a key role in bacterial fitness, pathogenicity, and persister cell formation. Front Microbiol 7:904. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.da Silva ACR, Ferro JA, Reinach FC, Farah CS, Furlan LR, Quaggio RB, Monteiro-Vitorello CB, Van Sluys MA, Almeida NF, Alves LMC, do Amaral AM, Bertolini MC, Camargo LEA, Camarotte G, Cannavan F, Cardozo J, Chambergo F, Ciapina LP, Cicarelli RMB, Coutinho LL, Cursino-Santos JR, El-Dorry H, Faria JB, Ferreira AJS, Ferreira RCC, Ferro MIT, Formighieri EF, Franco MC, Greggio CC, Gruber A, Katsuyama A, Kishi LT, Leite RP, Lemos EGM, Lemos MVF, Locali EC, Machado MA, Madeira A, Martinez-Rossi NM, Martins EC, Meidanis J, Menck CFM, Miyaki CY, Moon DH, Moreira LM, Novo MTM, Okura VK, Oliveira MC, Oliveira VR, et al. 2002. Comparison of the genomes of two Xanthomonas pathogens with differing host specificities. Nature 417:459–463. doi: 10.1038/417459a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. 2012. Molecular cloning, 4th ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andrade MO, Farah CS, Wang N. 2014. The post-transcriptional regulator rsmA/csrA activates T3SS by stabilizing the 5’ UTR of hrpG, the master regulator of hrp/hrc genes, in Xanthomonas. PLoS Pathog 10:e1003945. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Solovyev V, Salamov A. 2011. Automatic annotation of microbial genomes and metagenomic sequences, p 61–78. In Li RW. (ed), Metagenomics and its applications in agriculture, biomedicine and environmental studies. Nova Science Publishers, Hauppauge, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 43.El Yacoubi B, Brunings AM, Yuan Q, Shankar S, Gabriel DW. 2007. In planta horizontal transfer of a major pathogenicity effector gene. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:1612–1621. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00261-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li J, Wang N. 2011. The wxacO gene of Xanthomonas citri ssp. citri encodes a protein with a role in lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis, biofilm formation, stress tolerance and virulence. Mol Plant Pathol 12:381–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J, Wang N. 2014. Foliar application of biofilm formation-inhibiting compounds enhances control of citrus canker caused by Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. Phytopathology 104:134–142. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-04-13-0100-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guzzo CR, Salinas RK, Andrade MO, Farah CS. 2009. PILZ protein structure and interactions with PILB and the FIMX EAL domain: implications for control of type IV pilus biogenesis. J Mol Biol 393:848–866. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malamud F, Torres PS, Roeschlin R, Rigano LA, Enrique R, Bonomi HR, Castagnaro AP, Marano MR, Vojnov AA. 2011. The Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri flagellum is required for mature biofilm and canker development. Microbiology 157:819–829. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.044255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Belasque Júnior J, Bassanezi RB, Spósito MB, Ribeiro LM, De Jesus Junior WC, Amorim L. 2005. Escalas diagramáticas para avaliação da severidade do cancro cítrico. Fitopatol Bras 30:387–393. doi: 10.1590/S0100-41582005000400008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hazan R, Sat B, Sat B, Engelberg-Kulka H. 2004. Escherichia coli mazEF-mediated cell death is triggered by various stressful conditions. Microbiology 186:3663–3669. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.11.3663-3669.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oberto J. 2013. SyntTax: a web server linking synteny to prokaryotic taxonomy. BMC Bioinformatics 14:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hanahan D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol 166:557–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schaad NW, Postnikova E, Lacy GH, Sechler A, Agarkova I, Stromberg PE, Stromberg VK, Vidaver AK. 2005. Reclassification of Xanthomonas campestris pv. citri (ex Hasse 1915) Dye 1978 forms A, B/C/D, and E as X. smithii subsp. citri (ex Hasse) sp. nov. nom. rev. comb. nov., X. fuscans subsp. aurantifolii (ex Gabriel 1989) sp. nov. nom. rev. comb. nov., and X. alfalfae subsp. citrumelo (ex Riker and Jones) Gabriel et al., 1989 sp. nov. nom. rev. comb. nov.; X. campestris pv malvacearum (ex Smith 1901) Dye 1978 as X. smithii subsp. smithii nov. comb. nov. nom. nov.; X. campestris pv. alfalfae (ex Riker and Jones, 1935) Dye 1978 as X. alfalfa subsp. alfalfae (ex Riker et al., 1935) sp. nov. nom. rev.; and “var. fuscans” of X. campestris pv. phaseoli (ex Smith, 1987) Dye 1978 as X. fuscans subsp. fuscans sp. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol 28:494–518. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Caserta R, Picchi SC, Takita MA, Tomaz JP, Pereira WEL, Machado MA, Ionescu M, Lindow S, De Souza AA. 2014. Expression of Xylella fastidiosa RpfF in citrus disrupts signaling in Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri and thereby its virulence. MPMI 27:1241–1252. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-03-14-0090-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.