The type four pilus (Tfp) of Neisseria meningitidis contributes to fundamental processes such as adhesion, transformation, and disease pathology. Meningococci express one of two distinct classes of Tfp (class I or class II), which can be distinguished antigenically or by the major subunit (pilE) locus and its genetic context. The factors that govern transcription of the class II pilE gene are not known, even though it is present in isolates that cause epidemic disease. Here we show that the transcription of class II pilE is maintained throughout growth and under different stress conditions and is driven by a σ70-dependent promoter. This is distinct from Tfp regulation in nonpathogenic Neisseria spp. and may confer an advantage during host-cell interaction and infection.

KEYWORDS: Neisseria meningitidis, pilin, sigma factors, transcriptional regulation, type four pili

ABSTRACT

Neisseria meningitidis expresses multicomponent organelles called type four pili (Tfp), which are key virulence factors required for attachment to human cells during carriage and disease. Pilin (PilE) is the main component of Tfp, and N. meningitidis isolates either have a class I pilE locus and express pilins that undergo antigenic variation or have a class II pilE locus and express invariant pilins. The transcriptional regulation of class I pilE has been studied in both N. meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, while the control of expression of class II pilE has been elucidated in the nonpathogenic species Neisseria elongata. However, the factors that govern the regulation of the class II pilE gene in N. meningitidis are not known. In this work, we have bioinformatically and experimentally identified the class II pilE promoter. We confirmed the presence of conserved σ70 and σN-dependent promoters upstream of pilE in a collection of meningococcal genomes and demonstrated that class II pilE expression initiates from the σ70 family-dependent promoter. By deletion or overexpression of sigma factors, we showed that σN, σH, and σE do not affect class II pilin expression. These findings are consistent with a role of the housekeeping σD in expression of this important component of Tfp. Taken together, our data indicate that the σ-dependent network responsible for the expression of class II pilE has been selected to maintain pilE expression, consistent with the essential roles of Tfp in colonization and pathogenesis.

IMPORTANCE The type four pilus (Tfp) of Neisseria meningitidis contributes to fundamental processes such as adhesion, transformation, and disease pathology. Meningococci express one of two distinct classes of Tfp (class I or class II), which can be distinguished antigenically or by the major subunit (pilE) locus and its genetic context. The factors that govern transcription of the class II pilE gene are not known, even though it is present in isolates that cause epidemic disease. Here we show that the transcription of class II pilE is maintained throughout growth and under different stress conditions and is driven by a σ70-dependent promoter. This is distinct from Tfp regulation in nonpathogenic Neisseria spp. and may confer an advantage during host-cell interaction and infection.

INTRODUCTION

Neisseria meningitidis is a human-specific, Gram-negative bacterium that is a leading cause of meningitis and septicemia worldwide (1). Despite its ability to cause invasive disease, N. meningitidis colonizes the human nasopharynx, and it is carried asymptomatically by approximately 10% of the population (2). The capsular polysaccharide forms the basis of meningococcal classification into 12 serogroups, and meningococci can be further classified into clonal complexes based on nucleotide sequence differences in housekeeping genes (3). Certain clonal complexes, such as cc-11, have a marked propensity to cause disease and are referred to as hyperinvasive lineages (4).

Meningococci express type four pili (Tfp), which play key roles during meningococcal carriage and disease. During colonization, Tfp meditate the initial adherence of N. meningitidis to epithelial cells (5). Progression to systemic disease and dissemination from the nasopharynx are proposed to be triggered by the detachment of a small number of bacteria from microcolonies on the epithelial surface following changes in Tfp expression (6). Subsequently Tfp mediate formation of microcolonies on endothelial cells, providing resistance against shear stress in the circulation (7), as well as reorganization of host cell components, leading to translocation of N. meningitidis into the cerebrospinal fluid (8). In addition, Tfp are required for twitching motility and competence for DNA uptake that allows horizontal gene transfer between bacteria (9, 10).

The major component of Tfp is the pilin protein PilE. N. meningitidis isolates express one of two distinct classes of the type four pilin subunit: either a class I pilin, which undergoes high-frequency antigenic variation, or an invariant class II pilin (11). Based on genome analysis, meningococcal isolates have either a class I or a class II pilE locus but not both, and a number of features distinguish these loci (12, 13). For example, class I pilE loci are flanked by sequences that enable intrastrain pilin variation, namely, a G-quadruplex-forming (G4) sequence upstream of the pilE open reading frame (ORF) and a downstream Sma/Cla sequence. These features facilitate nonreciprocal homologous recombination between pilE and silent pilS cassettes located immediately downstream of pilE (14–17). Isolates that express invariant pilins harbor a class II pilE locus. This is situated at a different chromosomal site, and therefore, although pilS cassettes are present, they are not adjacent to pilE. Furthermore, the G4 and Sma/Cla elements are lacking from the regions adjacent to the class II pilE locus (12, 13, 18). Of note, strains with class II pilE mostly belong to hyperinvasive lineages that are responsible for epidemic disease in sub-Saharan Africa and for worldwide outbreaks (13, 19, 20).

A number of studies have investigated the transcriptional regulation of pilE in pathogenic and nonpathogenic Neisseria spp. (21–24). These have shown that the number, arrangement, and activity of pilE promoters vary between species and strains. For example, the class I pilE promoter in N. meningitidis strain MC58 includes both −10/−35 and −12/−24 sequences, but the −12/−24 sequence does not play a role in pilin transcription (21). The same is true in the related species Neisseria gonorrhoeae, in which the pilE promoter is similar to the meningococcal class I pilE promoter (25). In contrast, the pilE promoter of the nonpathogenic species Neisseria elongata lacks −10/−35 sequences, and transcription initiates from a −12/−24 sequence (23).

All bacterial promoters are recognized by sigma (σ) factors. These can be divided into two groups: (i) the σ70 family, which are structurally related factors that recognize −10/−35 sequences, and (ii) σN, which recognizes a consensus −12/−24 sequence and has a noncanonical mechanism of transcription initiation, requiring interaction with an AAA+ ATPase activator protein (26, 27). The meningococcal genome contains four genes encoding potential σ factors: three σ70 factors (σD, σE, and σH) and σN. σD is considered the housekeeping σ factor, σE is autoregulated by an anti-sigma factor and regulates 11 genes (28), and σH is essential but as yet has no defined role in the meningococcus, although it has been linked with the response to heat shock in gonococci (29, 30). σN has been reported to be nonfunctional based on analysis of isolates in which the rpoN gene is similar to the rpoN-like sequence (RLS) of N. gonorrhoeae (25). The gonococcal RLS has a frameshift mutation that results in loss of the domains required for DNA binding, namely, the helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif and the RpoN box which are required to bind to the −12 and −24 sequences, respectively (23, 25). More recently, genome sequence analysis has demonstrated that different meningococcal isolates encode distinct forms of σN, some of which lack both of the key DNA binding domains and others of which lack only the HTH motif (23). Interestingly, in N. elongata rpoN encodes a protein with both DNA binding motifs and which activates pilE transcription (23).

The factors that govern transcription of meningococcal class II pilE have not been studied previously. In this work, we characterized the pilE promoter in an N. meningitidis isolate expressing class II pilin (31). Through bioinformatic analysis of whole-genome sequences (WGS), we found that the class II pilE promoter region is highly conserved. The region comprises consensus σ70-dependent and σN-dependent promoter sequences. We show that class II pilE is expressed throughout bacterial growth and is transcribed from the σ70-dependent promoter. Our data showed that neither deletion of meningococcal rpoN nor overexpression of σN had any effect on pilin levels. Furthermore, altered expression of two other meningococcal σ factors, σE and σH, did not alter pilin levels, suggesting that class II pilin-expressing N. meningitidis strains have selectively retained housekeeping σD–dependent pilin transcription, allowing its constitutive expression.

RESULTS

Class II pilE promoter regions are conserved and distinct from class I pilE promoters.

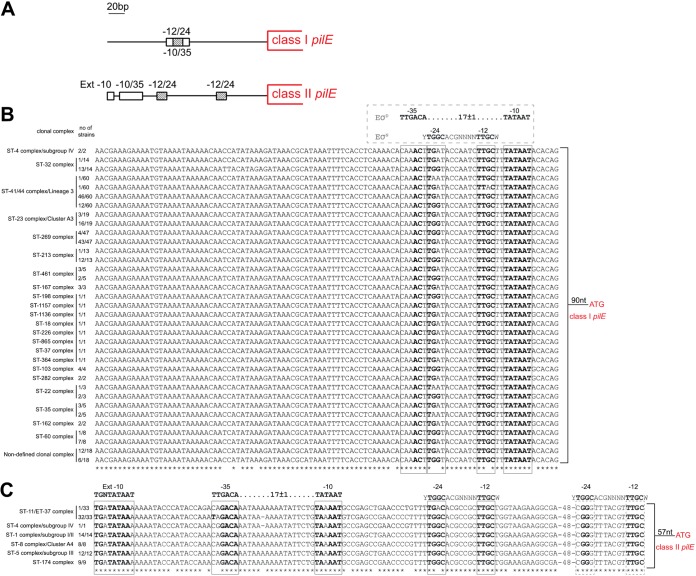

The sequence and organization of the pilE promoter in N. meningitidis have been described previously (12, 23, 24). Rendon et al. analyzed 64 meningococcal pilE promoter regions and classified them into three groups with different compositions of σ70-dependent and σN-dependent sequences (23). Independent analysis of genomes of meningococcal isolates expressing class I Tfp (8013 and MC58), and class II Tfp (FAM18) has shown that the compositions and sequences of the promoters of class I and class II pilE genes are distinct (12) (Fig. 1A). To determine whether this observation holds true for other strains, we analyzed pilE promoters in a collection of 290 meningococcal genomes. The collection included strains belonging to 20 different clonal complexes, isolated from 30 different countries, and comprised 213 isolates with class I pilE and 77 isolates with class II pilE (13). The sequence of the pilE promoter region was extracted from the PubMLST database using the full-length pilin-coding sequence from either 8013 (class I) or FAM18 (class II) as the query sequence and extracting 500 bp of 5′ flanking sequence. The nucleotide sequences of pilE and the promoter regions were aligned using Clustal Omega, and comparison with previously described meningococcal pilE promoter sequences (12, 21) and/or consensus sequences (32, 33) was used to annotate extended −10, −10/−35, and −12/−24 sequences. Our analysis revealed that the σ70- and σN-dependent promoter elements reported previously were present in all 213 class I pilE-containing isolates and that the relative positions of the −10/−35 and −12/−24 sequences were conserved (Fig. 1B). The sequences of the −10 and −35 elements were identical across all 213 isolates, and the −10 sequence was an exact match with the bacterial consensus −10 sequence (TATAAT). The −35 sequence, however, contained only two out of six consensus nucleotides (caaACt, compared to the consensus TTGACA), in line with previous reports that −35 sequences are not conserved in meningococcal genomes (21, 34). The σN-dependent promoter was located between the −35 and −10 sequences in all isolates but showed some sequence variation, and 138 of 213 strains contained at least one nonconsensus nucleotide in the −24 sequence (Fig. 1B), with one isolate, belonging to the ST-41/44 complex, having an additional change in the −12 region.

FIG 1.

Analysis of class I and class II pilE promoter regions in N. meningitidis. (A) Schematic representation of the class I and class II pilE promoter regions, based on N. meningitidis MC58 and 8013 (class I pilE) and FAM18 (class II pilE). An extended −10 and −10/−35 sequences are shown as open boxes, and the −12/−24 sequences are shown as striped boxes. (B and C) Clustal Omega alignment of the region upstream of pilE in isolates with class I (B) and class II (C) pilE. The clonal complex and the number of strains with the indicated sequences are shown. Sequences corresponding to −10/−35 and −12/−24 elements are boxed. E. coli consensus sequences (EσD −10/−35 and EσN −12/−24) are shown above the alignments. Asterisks indicate positions which have a single, fully conserved residue. Nucleotides in bold are identical to the consensus sequences.

Similarly, the σ70- and σN-dependent pilE promoters described in FAM18 (12, 23) were identified in all 77 genomes of strains with class II pilE (Fig. 1C). The extended −10 sequence was identical across all 77 isolates examined, and the sequence and spacing of the −10/−35 sequences of the σ70-dependent promoter were identical in 43 of the 77 isolates. Interestingly, in 1/1 cc-4 isolate and 32/33 cc-11 isolates the −10 and −35 elements were separated by 16 rather than 17 nucleotides, due to deletion of single adenine from a poly(A7) tract, although this still conforms to consensus σ70-dependent promoter spacing (35). Unlike the putative −35 sequence in the class I pilE promoters, the −35 sequence in the class II pilE promoters had at least four out of six nucleotides conserved (C/T-A/G-GACA [consensus, TTGACA]).

Two putative σN-dependent promoters were identified in all 77 isolates with class II pilE. These were previously reported in the pilE promoter region of FAM18 (12), and, similar to the published findings, one of the −12/−24 promoters had nonconsensus nucleotides in the −24 sequence (CGGG instead of TGGC), including nucleotide changes that have been shown experimentally to impair the activity of the σN promoter (32). The sequence of the second σN-dependent promoter was conserved and exhibited 100% nucleotide sequence identity to the −12/−24 consensus in all but one of the 77 isolates (Fig. 1C). This sequence conservation and lack of overlap with the σ70 binding site raised the possibility that the −12/−24 sequence is implicated in class II pilE regulation. Since the −12/−24 sequence requires σN for transcription initiation, we next examined the presence and sequence of rpoN, which encodes σN.

Meningococcal isolates contain atypical rpoN sequences.

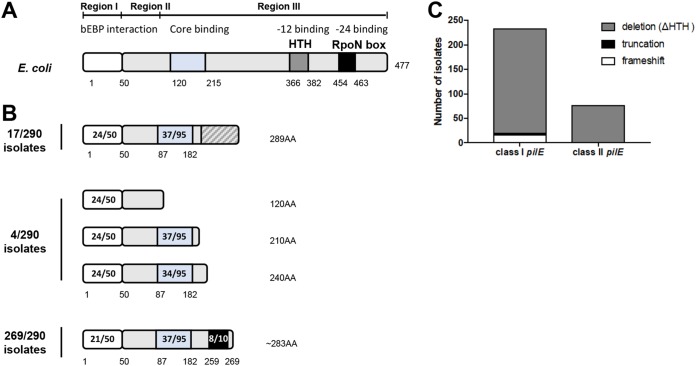

The rpoN gene in Escherichia coli (1,434 bp) is present in a single copy and encodes a protein of 477 amino acids (aa) with three domains. Region I is the activator binding domain, region II is a variable, nonessential region involved in DNA melting, and region III interacts with RNA polymerase (RNAP) and is implicated in promoter recognition and binding (26) (Fig. 2A). Region III contains two DNA binding/recognition motifs: an HTH motif (36) and the RpoN box (ARRTVAKYRE) (27). In N. gonorrhoeae the RLS is predicted to encode a protein of 277 aa which lacks the HTH motif and RpoN box; hence, any protein product is likely to be inactive (23, 25). In N. meningitidis 8013, the rpoN ORF encodes a potential 289-aa protein also without any recognizable HTH motif and which lacks the RpoN box due to a frameshift mutation (25, 37). However, more recently several N. meningitidis isolates were reported to harbor an rpoN sequence that encodes a protein which retains the RpoN box at the C terminus (23). We therefore investigated the presence and sequence conservation of rpoN in the collection of 290 N. meningitidis isolates.

FIG 2.

Schematic diagrams of σN proteins in E. coli and N. meningitidis. (A) Schematic representation of the E. coli σN domain organization. Three regions have been defined: region I mediates interactions with activator proteins (bEBPs), region II is a linker with variable sequence, and region III comprises an RNAP core binding domain and two DNA binding domains, the HTH motif and RpoN box. (B) Schematic of the deduced domain organization of σN in N. meningitidis. Analysis of genomes of 290 meningococcal isolates revealed 34 different peptide sequences. Putative domains were identified based on EMBOSS Water pairwise sequence alignment with E. coli σN. Meningococcal σN was classified into three groups. σN proteins present in 17/290 isolates and 4/290 isolates harbor frameshift mutations or are truncated, respectively, and therefore lack any DNA binding domains. In the majority of isolates (269/290, 93%) σN lacks the HTH domain but retains an in-frame RpoN box. Amino acid numbers are shown. Numbers in the boxes indicate the numbers of identical amino acids compared to E. coli σN. (C) Distribution of putative σN types (frameshift, truncation, or deletion) in isolates with class I or class II pilE.

The rpoN sequence from FAM18 (NEIS0212 allele 1 in PubMLST) was used as the query to extract sequences using BLASTn in PubMLST. We identified rpoN homologues in all 290 genomes. In total, there were 44 different alleles among the 290 isolates (see Table S1 and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The rpoN sequences were translated using EMBOSS Transeq, and predicted amino acid sequences were aligned using Clustal Omega. The 44 alleles encoded a total of 34 different peptides which range between 120 and 289 aa in length. Analysis of the 34 deduced protein sequences revealed three distinct types of σN (Fig. 2B). In 17/290 (6%) isolates, the putative σN protein is 289 aa and, similarly to the allele in N. meningitidis 8013, harbors a frameshift mutation and so lacks an RpoN box. In 4/290 (1%) of the isolates, the rpoN allele contains stop codons that result in truncated proteins. In the remaining 269 of 290 isolates (93%), the putative σN protein was as described by Rendon et al. (23), i.e., a protein which lacks a recognizable HTH domain but has an RpoN box in the C terminus. Analysis of the distribution of each of the three types of σN (frameshift, truncation, or deletion) in the isolates according to pilE locus demonstrated that 77/77 (100%) isolates with a class II pilE locus and 192/213 (90%) isolates with a class I pilE locus harbor an rpoN allele that encodes σN with an RpoN box but lacking the putative HTH region (Fig. 2C). Given the presence of a conserved RpoN box, we hypothesized that this atypical form of σN could retain binding to the −24 element and contribute to class II pilE transcription from the σN-dependent promoter.

σN-dependent promoters are usually preceded by one or more upstream activator sequences (UAS) situated 80 to 150 bp upstream of the −12/−24 sequence (38, 39). These sequences bind bacterial enhancer binding proteins (bEBPs), which are activated in response to certain stimuli and trigger a conformational change within the holoenzyme via ATP hydrolysis, resulting in the transition between closed and open complex formation and transcription initiation (38, 40). Based on homology to sequences in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a putative UAS has been identified in the promoter region of class I pilE in N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis (21, 22). We used the same UAS from P. aeruginosa (TGTGACACTTTTTGACA) to search for homologous sequences in the promoter regions of the 77 isolates with class II pilE. Sequences with 9/17 (TcTGACAaaaaacGtCA) or 10/17 (TcTGACAaaaaaTGtCA) nucleotide matches (unmatched nucleotides are lowercase) were identified approximately 112 bp upstream of the −12/−24 sequence in 50 and 24 of the genomes, respectively, but none of the isolates had an exact match to either the P. aeruginosa sequence or the putative UAS from N. meningitidis or N. gonorrhoeae (not shown).

rpoN is expressed in N. meningitidis, but no protein is detected and it is not required for pilin transcription.

Next, we examined whether σN can be detected in class II pilin-expressing N. meningitidis by Western blotting. Using cc-11 strain S4, which expresses class II pilin, a mutant was constructed in which the endogenous copy of rpoN was replaced with the rpoN ORF in frame with a sequence encoding a C-terminal histidine tag. The presence of σN in whole-cell lysates from bacteria grown overnight on solid medium was then assessed by Western blotting using an anti-His antibody. No protein of the predicted size (34 kDa) was present in extracts from S4rpoN_His, indicating that, under the conditions tested, σN could not be detected in N. meningitidis (data not shown).

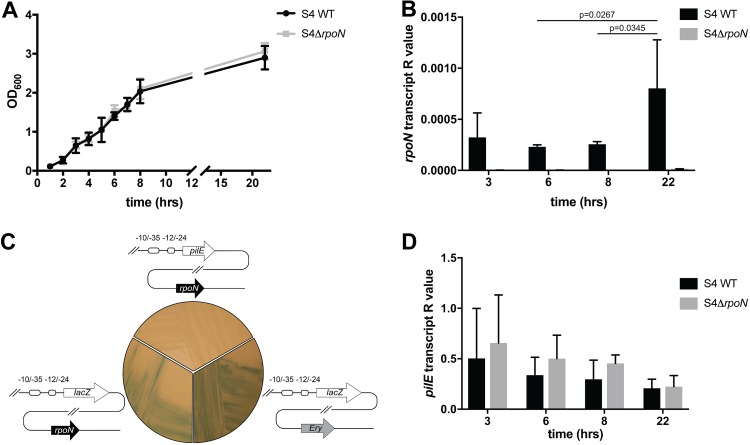

We therefore determined whether rpoN mRNA was detectable in N. meningitidis S4. Using quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) we measured rpoN transcript levels during growth of wild-type (WT) S4 in liquid medium at 37°C. RNA from strain S4 ΔrpoN, in which the entire rpoN coding sequence was replaced with an antibiotic resistance cassette, was used as a negative control for nonspecific amplification. Transcript levels were measured relative to those of transfer-messenger RNA (tmRNA). As shown in Fig. 3A, growth of wild-type S4 was similar to that of S4 ΔrpoN, indicating that the absence of rpoN does not impact bacterial fitness. rpoN transcript was detected throughout growth, albeit at low levels relative to those of the control tmRNA (Fig. 3B). rpoN transcript varied according to the growth phase, with highest levels detected during stationary phase (22 h).

FIG 3.

Effect of rpoN deletion on pilE levels in N. meningitidis. (A) Growth of N. meningitidis WT S4 and S4ΔrpoN in liquid medium at 37°C. (B) rpoN expression was measured using qRT-PCR at different time points as indicated. There was a significant difference between rpoN transcript levels in WT S4 at 22 h and 8 h (P = 0.0345) and at 22 h and 6 h, (P = 0.0267) (two-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]). No transcript was detected in S4ΔrpoN. (C) WT S4, S4ϕPpilE-lacZ, and S4ΔrpoNϕPpilE-lacZ were grown on medium containing X-Gal. Blue colonies indicate expression of β-galactosidase and therefore transcription from the pilE promoter. Colonies appeared blue even in the absence of rpoN. (D) pilE mRNA levels at different time points during the growth of WT S4 and S4ΔrpoN. pilE mRNA is present throughout bacterial growth, and no significant difference in pilE expression was detected, either at different time points or in the absence of rpoN. The amount of transcript is presented as an R value and normalized to tmRNA. Histograms show pooled data from three independent experiments. Error bars show SD.

To determine whether rpoN is required for pilE transcription, we next constructed reporter strains in which the class II pilE ORF was replaced by lacZ at the endogenous pilE locus in strains S4 and S4ΔrpoN (Fig. 3C). The resulting strains, S4ϕPpilE-lacZ and S4ΔrpoNϕPpilE-lacZ, were plated onto solid medium containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside (X-Gal), and the detection of blue colonies was used to qualitatively assess whether σN is required for pilE expression. After overnight growth, blue colonies were detected for both S4ϕPpilE-lacZ and S4ΔrpoNϕPpilE-lacZ, indicating that rpoN is not required for pilE expression. Finally we analyzed pilE transcript levels in wild-type S4 and in S4ΔrpoN. pilE mRNA was measured by qRT-PCR and expression levels normalized to those of tmRNA. As shown in Fig. 3D, pilE was expressed at similar levels throughout growth in the wild-type S4 and S4ΔrpoN, demonstrating that σN is not required for class II pilin expression in S4 under the conditions tested.

Induced expression of σN does not impact pilin protein levels in N. meningitidis.

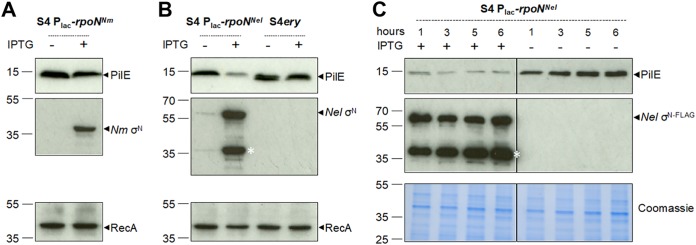

We considered the possibility that the absence of detectable σN in wild-type S4 could account for the observed lack of any effect of the deletion of rpoN on class II pilE transcript levels. Therefore, we examined the impact of inducing rpoN expression on pilin levels. We constructed N. meningitidis S4 harboring rpoN with an in-frame FLAG tag at an ectopic locus (41) under the control of an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter (S4Plac-rpoNNm). In parallel, we generated a strain (S4Plac-rpoNNel) with IPTG-inducible N. elongata rpoN, which activates pilE transcription in N. elongata by binding the −12/−24 sequence and requires the activator protein Npa (23), and a control strain, S4 ery, which lacks the σN-coding sequence at the ectopic locus. Pilin levels in S4Plac-rpoNNm, S4Plac-rpoNNel, and S4 ery were analyzed by Western blotting of cell lysates collected after overnight growth on solid medium with or without 1 mM IPTG to induce rpoN expression; the expression of σN was confirmed with anti-FLAG antibody. There was no detectable difference in pilin levels in S4Plac-rpoNNm in the presence or absence of inducer (Fig. 4A), demonstrating that expression of rpoN does not affect class II pilin levels. We therefore conclude that meningococcal σN is unlikely to bind to the −12/−24 sequences in the pilE promoter to activate transcription of class II pilE.

FIG 4.

Effect of rpoN overexpression on PilE levels in N. meningitidis. (A) S4Plac-rpoNNm was grown overnight on solid medium in the presence or absence of IPTG to induce σN expression. Pilin expression was detected by Western blotting with an antipeptide antibody. Expression of σN was verified using anti-FLAG antibodies. No change in pilin expression was detected in the presence of σN. (B) S4Plac-rpoNNel and control strain S4 ery were grown overnight on solid medium with or without IPTG. N. elongata σN was detected using anti-FLAG antibodies. Expression of σN from N. elongata in S4 led to a reduction in pilin expression, while no reduction was observed in the control strain. The asterisk indicates a degradation product of Nel σN-FLAG. (C) Similarly, a reduced level of pilin was detected in S4Plac-rpoNNel grown in liquid medium in the presence of IPTG for 1, 3, 5, and 6 h compared to that without the inducer. Expression of RecA or Coomassie blue staining of extracts was used as a control. Numbers to the left indicate the positions of molecular weight markers (kilodaltons).

Interestingly, the expression of N. elongata rpoN in N. meningitidis led to a substantial reduction in pilin expression (Fig. 4B), and this was also observed during growth in liquid medium (Fig. 4C). One possible explanation is that N. elongata σN can engage with the −12/−24 promoter upstream of class II pilE but, in the absence of additional N. elongata specific factors, transcription does not initiate, and the bound sigma factor instead blocks transcription from adjacent promoters. This phenomenon has been described in E. coli, in which an excess of σN can reduce RNA synthesis by σ70 RNAP when the σN binding site overlaps the region normally occupied by σ70 RNAP (42). Furthermore, our finding is consistent with analysis of gonococcal pilE promoters in E. coli, which has demonstrated that σN can reduce levels of transcription of PpilE-lacZ or PpilE-cat fusions, likely by steric hindrance at the overlapping σ70-dependent promoter (43, 44). Analysis of the relative positions of the –10/−35 promoter and the σN binding site upstream of class II pilE suggests that they are sufficiently close for competition to occur (42). Taken together, our data indicate that σN in N. meningitidis is nonfunctional or does not function as a canonical σN and that class II pilE transcription does not initiate from the −12/−24 promoter.

Class II pilE transcription initiates from the σ70-dependent promoter.

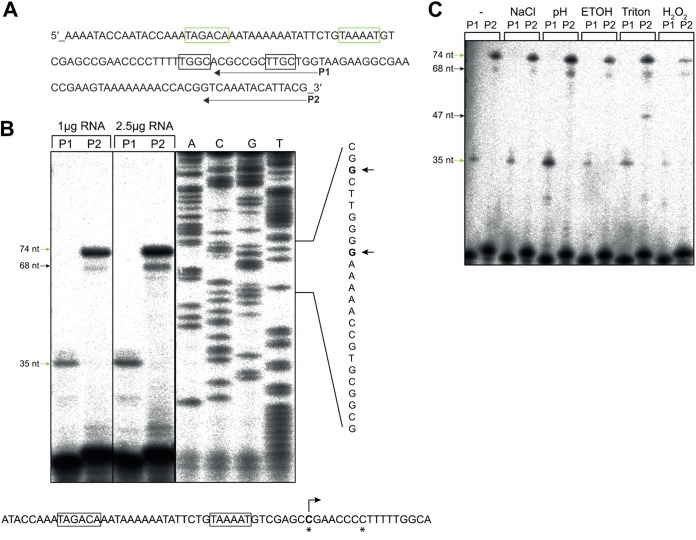

Next, we mapped the class II pilE transcriptional start site (TSS). Total RNA was prepared from N. meningitidis S4 grown in liquid brain heart infusion (BHI) at 37°C to mid-exponential phase, and primer extension was performed using primers designed to capture transcripts generated from both the −10/−35 and the −12/−24 promoters (primer P2) or from only the −10/−35 promoter (primer P1) (Fig. 5A). Extension conditions were such that any TSS within nucleotide (nt) −70 to −250 of the pilE start codon would be detected. Totals of 1 μg and 2.5 μg of RNA were used to generate cDNA with radiolabeled P1 and P2. Extension with primer P1 generated a product of ∼35 nt, corresponding to a transcript initiated from the −10/−35 sequence. Similarly, an ∼74-nt product was generated with P2, which corresponds to the same TSS. Interestingly, an ∼68-nt minor product was also generated with P2, which could be an alternative TSS or a degradation product. Importantly, using P2 there was no detectable product of ∼38 nt that would indicate transcription from the −12/−24 promoter, supporting our hypothesis that class II pilE transcription initiates from the σ70-dependent promoter. Sequencing with primer P2 using a PCR fragment of the upstream region of class II pilE as the template identified a cytosine residue located 8 nt downstream of the −10 sequence as the TSS of class II pilE (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5.

Identification of the class II pilE transcriptional start site. (A) Sequence of the region upstream of class II pilE in S4, comprising the putative −10/−35 and −12/−24 promoter elements (boxed). The position where primers P1 and P2 bind is indicated. (B) Primer extension was performed using 1 μg or 2.5 μg of RNA prepared from N. meningitidis S4 grown at 37°C in liquid BHI to mid-exponential phase. Products of approximately 35 nt (with primer P1) and 74 nt (with primer P2) were detected, corresponding to transcripts initiating from the −10/−35 promoter. An additional product of ∼68 nt was observed with P2. No product corresponding to transcript initiating from the −12/−24 sequence (∼38 nt) was detected. Lanes A, C, G, and T show sequences determined using a PCR product and primer P2. The transcription start sites (TSS) are indicated by arrows and highlighted by asterisks in the promoter sequence. (C) Primer extension of class II pilE transcript in bacteria subjected to different stresses as indicated. No difference in class II pilE TSS was observed. An additional extension product (∼47 nt) was detected with the P2 primer in Triton-treated samples. The experiment was performed twice using independent biological replicates.

Class II pilE transcript initiation is not affected by stress conditions.

σ factors are often associated with responses to a particular stress, and the level of a given σ factor increases rapidly following an appropriate stimulus (45). σN was originally identified in the response to nitrogen starvation but has since been implicated in responses to diverse stimuli mediated by specific bEBPs (26). Therefore, to determine whether pilE promoter activity changes when meningococci are subjected to different stress conditions, we performed primer extension on RNA from S4 exposed to salt (5 M NaCl), acid (HCl, pH 2.5), oxidative (0.15% H2O2 ), or envelope (5% ethanol or 5% Triton) stress for 10 min. N. meningitidis S4 grown to the same optical density at 600 nm (OD600) but not exposed to any stress was used as a control. As previously, we detected products corresponding to transcript initiation from the −10/−35 promoter under all conditions as well as the ∼68-nt product and a smaller ∼47-nt product with the primer P2 from bacteria exposed to Triton. However, none of the stress conditions led to the appearance of an ∼38-nt product with P2, indicating that the −10/−35 promoter is responsible for class II pilE transcription even under different environmental conditions.

Modulating levels of σE and σH does not impact class II pilin expression.

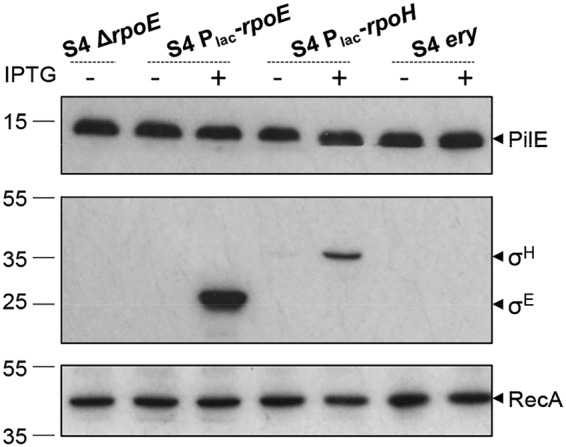

In bacteria, −10/−35 promoter sequences are able to recruit different σ factors belonging to the σ70 family (46, 47). For instance, the −10/−35 sequence upstream of rpoD in E. coli can bind σD, σE, and σS (48). Based on sequence similarity to orthologues in E. coli, three σ70 factors (σD, σH, and σE) have been identified in N. meningitidis. σD (encoded by NEIS1466) is considered the “housekeeping” σ factor. In most bacteria this σ factor is essential and is responsible for the transcription of the majority of genes and essential pathways throughout growth (49). Based on the analysis of essential genes in N. meningitidis 8013 and N. gonorrhoeae FA1090, rpoD is also essential in pathogenic Neisseria species (50, 51). The regulon of σH (encoded by NEIS0663) and its role in heat shock adaptation and regulation of genes involved in cell adhesion in N. gonorrhoeae has been characterized (30, 52), but the σH regulon in N. meningitidis has not been described. Finally, σE (NEIS2123) regulates 11 genes in N. meningitidis (28). The regulon does not include pilE, although the analysis was performed in a class I pilE-expressing strain. We hypothesized that if the pilE −10/−35 promoter binds different σ70 members, changing the levels of the sigma factors relative to the level of σD may impact pilin expression. Therefore, we constructed N. meningitidis mutants lacking or overexpressing σH or σE and examined pilin levels in these backgrounds.

Consistent with σH being essential in N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis (30, 51), our attempts to construct S4ΔrpoH were unsuccessful. Therefore, we generated strain S4Plac-rpoH, in which σH expression is inducible by IPTG and detectable due to the presence of a C-terminal FLAG tag. S4Plac-rpoH was grown overnight on solid medium with or without IPTG, and pilin levels were analyzed by Western blotting. There was no difference in pilin expression in the presence or absence of IPTG (Fig. 6).

FIG 6.

Pilin levels are unaffected by altering levels of σH or σE. Western blot analysis of pilin levels in whole-cell lysates collected from bacteria lacking σE (S4 ΔrpoE) or with inducible expression of σH or σE (S4 Plac-rpoH and S4 Plac-rpoE), or from a control strain (S4 ery), on solid medium at 37°C is shown. Expression of IPTG-induced σE and σH was detected using anti-FLAG antibody. No change in pilin levels was observed when σ factors were deleted or induced. RecA was used as a control, and the blot is a representative from two independent experiments. Numbers to the leftls indicate the positions of molecular weight markers (kilodaltons).

As meningococcal σE is not essential (28), we generated S4ΔrpoE by replacing the rpoE ORF with a kanamycin resistance cassette, as well as strain S4Plac-rpoE overexpressing FLAG-tagged σE. Western blot analysis revealed that pilin levels remained unaltered in the absence or induced expression of σE (Fig. 6). This is consistent with pilE not being part of the σE regulon and indicates that σE is not essential for pilin production. Since expression and/or deletion of rpoH and rpoE does not affect class II pilin levels, we conclude that class II pilE transcription is initiated from the −10/−35 promoter by σD.

DISCUSSION

Among the factors that allow bacteria to colonize and infect the human host, Tfp play a key role by meditating adhesion, signaling, and interbacterial attachment (7, 8, 53). Alterations to Tfp, through either changes in sequence, posttranslational modification, or changes in expression, can have important consequences for bacterial behavior. For example, the absence of Tfp significantly reduces the ability of bacteria to attach to host cells (54–56), while modification of the pilin sequence, glycosylation, or phospho-modification can impact bacterial adhesion and aggregation and may contribute to dissemination within or between hosts (5, 57, 58). Therefore, understanding the mechanisms by which Tfp expression and function are modulated is important for understanding pathogenesis and may provide insights into novel ways to overcome meningococcal immune evasion strategies.

Two distinct classes of pilin have been identified in pathogenic Neisseria (11, 12). Class I pilins can be altered at high frequency through gene conversion or phase variation (16, 59–62), while class II pilins are invariant. As described in previous studies, the meningococcal class II pilE locus is distinguishable from the class I pilE locus based on the encoded pilin sequence, the flanking genes, and the presence of sequences required for antigenic variation (13). Our current work confirms that class I and class II pilE loci also have different promoter sequences, consistent with previous observations (12). Mirroring the very low nucleotide diversity of class II pilin-coding sequences (13, 19, 20), the class II pilE promoter regions were highly conserved and, independent of clonal complex, harbored potential σ70 and σN binding sequences. These findings differ from those of Rendon et al. (23), who defined three types of pilE promoter, including one group (represented by FAM18) with σN but not σ70 recognition sequences; instead, we identified putative σ70-dependent promoters in all genomes, including FAM18.

Previous studies of pilE regulation in pathogenic Neisseria spp. showed that transcription of class I pilE relies on the σ70-dependent rather than the σN-dependent promoter (21, 22, 24). The presence and position of highly conserved, consensus −12/−24 sequences upstream of class II pilE, as well as an rpoN gene encoding a sigma factor with a conserved −24 binding region, led us to investigate the role of the σN-dependent promoter in class II pilE transcription. Based on structure-function studies in other organisms, we considered the possibility that this atypical form of σN still activates transcription despite lacking the −12 binding HTH domain. For example, mutants which do not effectively recognize the −12 sequence can still produce RNA in vitro in an activator-independent manner known as σN bypass transcription (63). Consistent with this, no GAFTGA-containing bEBPs have been identified in N. meningitidis (64), and Npa, the activator for σN-dependent pilE transcription in N. elongata, is truncated in N. meningitidis (23, 65). Furthermore, in E. coli σN bypass transcription can occur at −12/−24 promoters with a noncanonical −12 element (42). However, our findings indicate that the −12/−24 promoter and σN do not contribute to class II pilE expression; we were unable to detect any σN protein expression, and neither deletion nor overexpression of rpoN had any significant effect on class II pilE transcript or protein levels. Furthermore, mapping the TSS of class II pilE demonstrated that the σ70-dependent promoter is responsible for class II pilE expression, even under a variety of stress conditions, some of which are known to induce σN-dependent transcription in E. coli (66). Collectively, our results demonstrate that class II pilE transcription is independent of σN and initiates from the −10/−35 promoter.

An important observation that emerged from our analysis is that in a variety of N. meningitidis mutants lacking sigma factors, as well in the presence of stress signals, pilE transcript and/or protein expression remained relatively stable. Considering the importance of Tfp for bacterium-bacterium interactions, competence, and adhesion to host cells, it is likely that class II pilE is constitutively expressed to ensure that the capacity to synthesize pilin is maintained. Consistent with this, changing levels of σE, σH, or σN had no detectable impact on pilin levels. Although we cannot rule out that σH or σE may contribute to the expression of class II pilE under specific conditions, we found no evidence of σN expression or activity.

Of note, we found alleles which encode the same σN mutations or deletions in strains with either a class I or class II pilE locus, suggesting that the loss of functional rpoN occurred independently of the evolution of the distinct pilE loci. Interestingly, the commensal species Neisseria polysaccharea and Neisseria lactamica have class II pilE loci that are very closely related to the meningococcal class II pilE locus, and in our previous work we proposed that class II pilin-expressing meningococci may have either evolved from a common ancestor or acquired the class II pilE gene from these species (13). However, the rpoN gene in these nonpathogenic species does not harbor mutations and deletions and potentially encodes a functional σN (23). Therefore, our findings suggest that loss of functional σN is beneficial for the pathogenic Neisseria spp. and are consistent with the idea that a switch in pilE regulation from σN-dependent to σD-dependent control occurred during evolution and divergence of pathogens from commensals (23, 25). As σN-dependent transcription is usually tightly regulated by bEBPs which respond only to specific stimuli, loss of σN-dependent transcription of pilE might therefore be an evolutionary pathway to achieve constitutive σD-dependent expression from the −10/−35 promoter. In this way, transcription of the gene encoding the major component of Tfp is maintained, consistent with the significant contribution of this important organelle at multiple stages of colonization and pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. E. coli was grown at 37°C, supplemented with antibiotics where appropriate, either on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar or in 5 ml LB liquid with shaking at 180 rpm. N. meningitidis was grown at the desired temperature in the presence of 5% CO2 on brain heart infusion (BHI) (Oxoid) agar supplemented with 0.1% (wt/vol) starch, 5% (wt/vol) heat-denatured horse blood, and antibiotics as appropriate or in BHI liquid. To inoculate liquid cultures, N. meningitidis was grown overnight on BHI agar. A loop of bacteria was harvested from plates and resuspended in 600 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and DNA was quantified in lysis buffer (P2 buffer; Qiagen) by measuring the OD260. A total of 109 CFU was used to inoculate 25 ml of BHI in a 125-ml conical flask (Corning) and then incubated at appropriate temperatures with shaking at 180 rpm. The OD600 of cultures was used to monitor growth. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: kanamycin, 50 μg/ml and 75 μg/ml for E. coli and N. meningitidis, respectively; erythromycin, 2 μg/ml; and carbenicillin, 100 μg/ml.

Bioinformatic analysis.

The 290 isolates whose genomes were used in this study comprise 288 isolates described in our previous work (13) and two additional isolates: S4 and FAM18 (class II pilE). Among the 288 isolates, 56 belong to the collection of 107 meningococcal isolates originally used for multilocus sequence type (MLST) development in Neisseria (3). The remaining 232 are disease-associated strains isolated during the 2010–2011 epidemiological year from patients in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland and whose genomes are publicly available through the Meningitis Research Foundation genome library (MRF-MGL) on PubMLST (https://pubmlst.org/neisseria/) (67). These isolates were chosen for pilE promoter and rpoN analysis based on our previous work where we identified them as having either a class I or a class II pilE locus (13). BLASTn analysis of genomes in the PubMLST Neisseria database was performed to identify pilE promoter and rpoN sequences. For pilE promoter analysis, up to 500 nt of sequence flanking the coding DNA sequence (CDS) was analyzed, and annotation was performed manually based on published pilE promoters (12, 21, 32) and bacterial consensus promoter sequences (33). Nucleotide sequences were aligned using Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/) (68). Percent identity was determined using the percent identity matrix within Clustal Omega. rpoN (NEIS0212) of each isolate used in our study was identified by BLAST, results were manually inspected to define coding sequences, and alleles were assigned using PubMLST. Sequences were translated using EMBOSS Transeq (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/st/emboss_transeq/). N. meningitidis σN putative domains were identified based on alignment with E. coli σN using the EMBOSS Water pairwise sequence alignment tool with the default settings (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/psa/emboss_water/). SnapGene was used to construct plasmid maps and for automatic annotation of features and ORFs in whole-genome sequences.

Mutant construction.

The primers used in this study are listed in Table S3 in the supplemental material. N. meningitidis strains lacking σ factors were constructed by gene replacement. First, DNA fragments corresponding to 479 bp upstream and 712 bp downstream of the N. meningitidis S4rpoN ORF (NEIS0212, homologue of FAM18 NMC_RS01150) and a kanamycin resistance cassette were amplified by PCR using primers ML20/21, ML22/23, and ML24/25, respectively. The upstream and downstream fragments were cloned into pGEM-T Easy flanking a kanamycin resistance cassette, resulting in pGEM-T Easy ΔrpoN. This plasmid was digested with BamHI and NotI, and the ΔrpoN fragment was purified by gel extraction prior to transformation into S4. Plasmid pUC19ΔrpoE was generated by amplifying 483-bp and 459-bp fragments corresponding to regions upstream and downstream of the N. meningitidis rpoE (NEIS2123, homologue of FAM18 NMC_RS11230) using primers ML284/ML285 and ML288/ML289, respectively. A kanamycin resistance cassette was amplified using primers ML286/ML287, and the three fragments were ligated into pUC19 using the NEB Builder HiFi DNA assembly kit (New England Biolabs). The construct for replacing rpoE with the kanamycin resistance gene was amplified from pUC19ΔrpoE by PCR and then purified and used for transformation into S4.

To generate S4 and S4ΔrpoN harboring ϕPpilE-lacZ at the native pilE locus, first rpoN was replaced with ermC, encoding erythromycin resistance. Briefly, regions upstream (485 bp) and downstream (886 bp) of the rpoN start and stop codons, respectively, were amplified from existing mutant S4ΔrpoN (Kanr) genomic DNA (gDNA) using primers ML20/ML46 and ML25/ML52, and overlap PCR was used to clone these fragments 5′ and 3′ of an erythromycin resistance gene, respectively. The product was cloned into pCR2.1TOPO, resulting in pCR2.1TOPOΔrpoN, which was then used as a template to amplify the deletion construct for transformation, generating S4ΔrpoN (Eryr). Subsequently, the pilE ORF was replaced with lacZ as follows. A 673-bp region immediately 5′ of the pilE ORF was amplified from S4 gDNA using ML37/ML34. A fragment corresponding to the region 3′ of the pilE ORF with a kanamycin resistance marker inserted 81 bp downstream of the pilE stop codon was amplified from strain S4_pilEkanR (R. Exley, unpublished data) using ML30/ML31. The two fragments were cloned into pCR2.1TOPO flanking the lacZ gene, which was amplified from pRS415 (69) using primers ML32/ML33. The resulting plasmid, pCR2.1TOPOϕPpilE-lacZ, was used as a template to amplify DNA for transformation of wild-type S4 or S4ΔrpoN.

N. meningitidis strains overexpressing σ factors were constructed by inserting the relevant ORF at the iga-trpB intergenic locus (41) of N. meningitidis S4, under the control of an IPTG inducible promoter. For this purpose, pNMC2 was generated. First, a fragment comprising part of the iga gene and terminator was amplified from S4 gDNA using primers ML151 and ML149. Next, a fragment comprising ermC, the lac regulatory region, and a multiple-cloning site (MCS) was amplified from pGCC4 (a gift from Hank Seifert) (Addgene plasmid 37058; http://n2t.net/addgene:37058; RRID:Addgene_37058) using primers ML148/ML150. The two fragments were fused by overlap PCR using primers ML148 and ML151. The resulting PCR product was then combined using Gibson assembly with a fragment amplified from plasmid pNCC1 (70) with primers ML152 and ML153 (providing the origin of replication and kanamycin selection marker) and a fragment comprising the 3′ end of the trpB gene amplified from S4 gDNA using primers ML146 and ML147. Genes encoding C-terminally tagged sigma factors were amplified as follows. The rpoN, rpoE, and rpoH (NEIS0663, homologue of FAM18 NMC_RS03540) genes were amplified from S4 gDNA using primers ML154/ML155, ML280/ML282, and ML184/ML188, respectively. The PCR products were ligated into HindIII-digested pNMC2 using the NEB Builder HiFi DNA assembly kit to generate pNMC2rpoNNm, pNMC2rpoE, and pNMC2rpoH. pNMC2rpoNNel was generated using Gibson assembly with a fragment amplified from pNMC2rpoNNm using ML172/ML174 and a fragment comprising rpoN from N. elongata (NELON_RS02880) amplified using gDNA from strain 29315 and primers ML173/ML175. Plasmids were linearized by digestion with NcoI to ensure double-crossover recombination and prevent integration of the entire plasmid and were used to transform S4. DNA from single transformants selected on erythromycin was analyzed by PCR, and gDNA from PCR-positive colonies was backcrossed into the parental strain. Backcrossed colonies were pooled, and gDNA from the pooled stock was checked by PCR and sequencing of the region of interest.

RNA isolation.

N. meningitidis was grown at 37°C in liquid BHI, and at the indicated times a volume equivalent to an OD600 of ≈8 was centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was removed, and total RNA was isolated from pellets using TRIzol extraction (Thermo Fisher). Briefly, cell pellets were resuspended in 2 ml of TRIzol and incubated at room temperature for 5 min before adding 200 μl of chloroform. Samples were shaken by hand for 15 s, incubated at room temperature for 2 to 3 min, and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and the aqueous phase was transferred to a fresh tube. RNA was precipitated by adding 500 μl isopropanol, followed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. RNA pellets were washed with 75% ethanol and then air dried and resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water. Following DNase treatment for 2 h at 37°C, RNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform (5:1). The aqueous phase was reextracted with DEPC-treated water and chloroform-isoamyl alcohol. Samples were vortexed and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The aqueous phase was transferred to a tube containing 33 μl of 3 M Na acetate (pH 4.5) and 812.5 μl of 99.5% ethanol, and RNA was precipitated over 2 h or overnight at –20°C. Following centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, RNA pellets were washed with 75% ethanol, centrifuged again for 10 min at 20,000 × g, air dried, and resuspended in 200 μl DEPC-treated water.

qRT-PCR.

All primers used in quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) are listed in Table S3. RNA (2.5 μg) was used to synthesize cDNA with primers specific for the target gene containing a tag sequence (CCGTCTAGCTCTCTCTAATCG) which is not present in the N. meningitidis genome. RNA was reverse transcribed using reverse transcriptase III polymerase (Invitrogen) and treated with RNase H for 20 min at 37°C. cDNA was purified using the Wizard gel PCR purification kit (Promega). qRT-PCR was performed using Power SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). Primer efficiency was evaluated using serial dilutions of gDNA to generate a standard curve, and the slope of the standard curve for each primer pair was calculated. StepONEPlus real-time PCR software was used to collect qRT-PCR data; the ΔCT method (where CT is the threshold cycle) was used to analyze the data (71). Results are presented as the normalized R value (where the R value is calculated as 2−CT) relative to tmRNA. Experiments were repeated at least three times, each time with triplicate samples. The results shown are means and standard deviations (SD) of three biological replicates; tmRNA was used as a control.

Primer extension.

Primer extension was carried out using 1 μg and 2.5 μg of RNA isolated from N. meningitidis grown to mid-log phase (OD600 ≈ 0.4 to 0.5). Primers (P1 and P2 [Table S3]) were radiolabeled using [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer). A mix of radiolabeled primers and RNA was incubated for 3 min at 95°C and rapidly cooled on ice for 4 min. Reverse transcription was performed using Superscript II (Invitrogen) by incubating samples at 45°C for 60 min then stopped by deactivating the enzyme for 10 min at 70°C. Formamide loading dye (10 μl) was added to each reaction mixture, and samples were heated briefly at 95°C. Fifteen microliters of each sample was loaded on a 12% denaturing polyacrylamide sequencing gel, and electrophoresis was performed for 2 to 3 h at 20 to 25 W until bromophenol blue dye reached the bottom of the gel. Products were analyzed using a phosphorimager (FujiFilm). Sanger sequencing was performed using primer P2 and a DNA cycle sequencing kit (Jena Bioscience) with a PCR-amplified fragment of the promoter region of pilE from S4 as a template.

Western blot analysis.

N. meningitidis whole-cell extracts were prepared from bacteria grown overnight at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2, on solid medium or in liquid with appropriate antibiotics with or without 1 mM IPTG. Suspensions were normalized to an OD600 of 1 in 1 ml BHI and then centrifuged for 5 min at 12,000 × g, and the pellets were resuspended in an equal volume of sterile water and 2× SDS-PAGE lysis buffer (1 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 10% SDS, 30% glycerol, 1% bromophenol blue) containing 200 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Samples were boiled for 10 min prior to electrophoresis. Proteins were separated on 12% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond-C Extra [Amersham] or Immobilon-P polyvinylidene difluoride [PVDF] [Millipore]) using a Bio-Rad Trans-Blot Turbo system. Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C in PBS–5% milk. Western blotting was performed using anti-FLAG antibody (F1804; Sigma) at 1:5,000 and goat anti-mouse IgG–horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (final dilution, 1:10,000; Dako) or using antipilin (EP11270 antipeptide, 1:10,000) and goat anti-rabbit IgG–HRP (final dilution, 1:10,000; Santa-Cruz). Anti-RecA (1:5,000) (ab63797; Abcam) followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG–HRP (final dilution, 1:10,000; Santa-Cruz) or Coomassie blue staining was used as a loading control. All incubations with antibodies were for 1 h at room temperature in PBS–5% milk containing 0.1% Tween. Membranes were washed three times with PBS–0.1% Tween between incubations. Cross-reacting proteins were visualized using ECL detection reagent (GE Healthcare).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Martin Buck (Imperial College London) for helpful advice, to Aartjan te Velthuis for assistance with primer extension, and to Felicia Tan for help with RNA work.

This study made use of the Neisseria Multi Locus Sequence Typing website (http://pubmlst.org/neisseria/) funded by the Wellcome Trust and the European Union. M.L. is funded by the Anatoliy Denisenko Charitable Fund, Kharkov, Ukraine, and the CIU Trust. R.M.E. and C.M.T. are funded by the Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00170-19.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pizza M, Rappuoli R. 2015. Neisseria meningitidis: pathogenesis and immunity. Curr Opin Microbiol 23:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Read RC. 2014. Neisseria meningitidis clones, carriage, and disease. Clin Microbiol Infect 20:391–395. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maiden MC, Bygraves JA, Feil E, Morelli G, Russell JE, Urwin R, Zhang Q, Zhou J, Zurth K, Caugant DA, Feavers IM, Achtman M, Spratt BG. 1998. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:3140–3145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trotter C, Samuelsson S, Perrocheau A, de Greeff S, de Melker H, Heuberger S, Ramsay M. 2005. Ascertainment of meningococcal disease in Europe. Euro Surveill 10:247–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Virji M, Saunders JR, Sims G, Makepeace K, Maskell D, Ferguson DJ. 1993. Pilus-facilitated adherence of Neisseria meningitidis to human epithelial and endothelial cells: modulation of adherence phenotype occurs concurrently with changes in primary amino acid sequence and the glycosylation status of pilin. Mol Microbiol 10:1013–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imhaus AF, Dumenil G. 2014. The number of Neisseria meningitidis type IV pili determines host cell interaction. EMBO J 33:1767–1783. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikaty G, Soyer M, Mairey E, Henry N, Dyer D, Forest KT, Morand P, Guadagnini S, Prevost MC, Nassif X, Dumenil G. 2009. Extracellular bacterial pathogen induces host cell surface reorganization to resist shear stress. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000314. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coureuil M, Mikaty G, Miller F, Lecuyer H, Bernard C, Bourdoulous S, Dumenil G, Mege RM, Weksler BB, Romero IA, Couraud PO, Nassif X. 2009. Meningococcal type IV pili recruit the polarity complex to cross the brain endothelium. Science 325:83–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1173196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown DR, Helaine S, Carbonnelle E, Pelicic V. 2010. Systematic functional analysis reveals that a set of seven genes is involved in fine-tuning of the multiple functions mediated by type IV pili in Neisseria meningitidis. Infect Immun 78:3053–3063. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00099-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolfgang M, Lauer P, Park HS, Brossay L, Hebert J, Koomey M. 1998. PilT mutations lead to simultaneous defects in competence for natural transformation and twitching motility in piliated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol 29:321–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Virji M, Heckels JE, Potts WJ, Hart CA, Saunders JR. 1989. Identification of epitopes recognized by monoclonal antibodies SM1 and SM2 which react with all pili of Neisseria gonorrhoeae but which differentiate between two structural classes of pili expressed by Neisseria meningitidis and the distribution of their encoding sequences in the genomes of Neisseria spp. J Gen Microbiol 135:3239–3251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aho EL, Botten JW, Hall RJ, Larson MK, Ness JK. 1997. Characterization of a class II pilin expression locus from Neisseria meningitidis: evidence for increased diversity among pilin genes in pathogenic Neisseria species. Infect Immun 65:2613–2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wormann ME, Horien CL, Bennett JS, Jolley KA, Maiden MC, Tang CM, Aho EL, Exley RM. 2014. Sequence, distribution and chromosomal context of class I and class II pilin genes of Neisseria meningitidis identified in whole genome sequences. BMC Genomics 15:253. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cahoon LA, Seifert HS. 2009. An alternative DNA structure is necessary for pilin antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Science 325:764–767. doi: 10.1126/science.1175653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haas R, Veit S, Meyer TF. 1992. Silent pilin genes of Neisseria gonorrhoeae MS11 and the occurrence of related hypervariant sequences among other gonococcal isolates. Mol Microbiol 6:197–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagblom P, Segal E, Billyard E, So M. 1985. Intragenic recombination leads to pilus antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Nature 315:156–158. doi: 10.1038/315156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seifert HS. 1992. Molecular mechanisms of antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Cell Biol Hum Dis Ser 1:1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aho EL, Cannon JG. 1988. Characterization of a silent pilin gene locus from Neisseria meningitidis strain FAM18. Microb Pathog 5:391–398. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cehovin A, Winterbotham M, Lucidarme J, Borrow R, Tang CM, Exley RM, Pelicic V. 2010. Sequence conservation of pilus subunits in Neisseria meningitidis. Vaccine 28:4817–4826. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun X, Zhou H, Xu L, Yang H, Gao Y, Zhu B, Shao Z. 2013. Prevalence and genetic diversity of two adhesion-related genes, pilE and nadA, in Neisseria meningitidis in China. Epidemiol Infect 141:2163–2172. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812002944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrick CS, Fyfe JA, Davies JK. 1997. The normally silent sigma54 promoters upstream of the pilE genes of both Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis are functional when transferred to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene 198:89–97. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fyfe JA, Carrick CS, Davies JK. 1995. The pilE gene of Neisseria gonorrhoeae MS11 is transcribed from a sigma 70 promoter during growth in vitro. J Bacteriol 177:3781–3787. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.13.3781-3787.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rendon MA, Hockenberry AM, McManus SA, So M. 2013. Sigma factor RpoN (sigma54) regulates pilE transcription in commensal Neisseria elongata. Mol Microbiol 90:103–113. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taha MK, Giorgini D, Nassif X. 1996. The pilA regulatory gene modulates the pilus-mediated adhesion of Neisseria meningitidis by controlling the transcription of pilC1. Mol Microbiol 19:1073–1084. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.448979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laskos L, Dillard JP, Seifert HS, Fyfe JA, Davies JK. 1998. The pathogenic neisseriae contain an inactive rpoN gene and do not utilize the pilE sigma54 promoter. Gene 208:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00664-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buck M, Gallegos MT, Studholme DJ, Guo Y, Gralla JD. 2000. The bacterial enhancer-dependent sigma(54) (sigma(N)) transcription factor. J Bacteriol 182:4129–4136. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4129-4136.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor M, Butler R, Chambers S, Casimiro M, Badii F, Merrick M. 1996. The RpoN-box motif of the RNA polymerase sigma factor sigma N plays a role in promoter recognition. Mol Microbiol 22:1045–1054. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huis In’t Veld RA, Willemsen AM, van Kampen AH, Bradley EJ, Baas F, Pannekoek Y, van der Ende A. 2011. Deep sequencing whole transcriptome exploration of the sigmaE regulon in Neisseria meningitidis. PLoS One 6:e29002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gunesekere IC, Kahler CM, Powell DR, Snyder LA, Saunders NJ, Rood JI, Davies JK. 2006. Comparison of the RpoH-dependent regulon and general stress response in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol 188:4769–4776. doi: 10.1128/JB.01807-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laskos L, Ryan CS, Fyfe JA, Davies JK. 2004. The RpoH-mediated stress response in Neisseria gonorrhoeae is regulated at the level of activity. J Bacteriol 186:8443–8452. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.24.8443-8452.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uria MJ, Zhang Q, Li Y, Chan A, Exley RM, Gollan B, Chan H, Feavers I, Yarwood A, Abad R, Borrow R, Fleck RA, Mulloy B, Vazquez JA, Tang CM. 2008. A generic mechanism in Neisseria meningitidis for enhanced resistance against bactericidal antibodies. J Exp Med 205:1423–1434. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrios H, Valderrama B, Morett E. 1999. Compilation and analysis of sigma(54)-dependent promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 27:4305–4313. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hook-Barnard IG, Hinton DM. 2007. Transcription initiation by mix and match elements: flexibility for polymerase binding to bacterial promoters. Gene Regul Syst Biol 1:275–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heidrich N, Bauriedl S, Barquist L, Li L, Schoen C, Vogel J. 2017. The primary transcriptome of Neisseria meningitidis and its interaction with the RNA chaperone Hfq. Nucleic Acids Res 45:6147–6167. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimada T, Yamazaki Y, Tanaka K, Ishihama A. 2014. The whole set of constitutive promoters recognized by RNA polymerase RpoD holoenzyme of Escherichia coli. PLoS One 9:e90447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doucleff M, Pelton JG, Lee PS, Nixon BT, Wemmer DE. 2007. Structural basis of DNA recognition by the alternative sigma-factor, sigma54. J Mol Biol 369:1070–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rusniok C, Vallenet D, Floquet S, Ewles H, Mouze-Soulama C, Brown D, Lajus A, Buchrieser C, Medigue C, Glaser P, Pelicic V. 2009. NeMeSys: a biological resource for narrowing the gap between sequence and function in the human pathogen Neisseria meningitidis. Genome Biol 10:R110. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-10-r110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bush M, Dixon R. 2012. The role of bacterial enhancer binding proteins as specialized activators of sigma54-dependent transcription. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76:497–529. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00006-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Studholme DJ, Dixon R. 2003. Domain architectures of sigma54-dependent transcriptional activators. J Bacteriol 185:1757–1767. doi: 10.1128/jb.185.6.1757-1767.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glyde R, Ye F, Jovanovic M, Kotta-Loizou I, Buck M, Zhang X. 2018. Structures of bacterial RNA polymerase complexes reveal the mechanism of DNA loading and transcription initiation. Mol Cell 70:1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramsey ME, Hackett KT, Kotha C, Dillard JP. 2012. New complementation constructs for inducible and constitutive gene expression in Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:3068–3078. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07871-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schaefer J, Engl C, Zhang N, Lawton E, Buck M. 2015. Genome wide interactions of wild-type and activator bypass forms of sigma54. Nucleic Acids Res 43:7280–7291. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boyle-Vavra S, So M, Seifert HS. 1993. Transcriptional control of gonococcal pilE expression: involvement of an alternate sigma factor. Gene 137:233–236. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90012-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fyfe JA, Strugnell RA, Davies JK. 1993. Control of gonococcal pilin-encoding gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene 123:45–50. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90537-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharma UK, Chatterji D. 2010. Transcriptional switching in Escherichia coli during stress and starvation by modulation of sigma activity. FEMS Microbiol Rev 34:646–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rhodius VA, Suh WC, Nonaka G, West J, Gross CA. 2006. Conserved and variable functions of the sigmaE stress response in related genomes. PLoS Biol 4:e2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wade JT, Castro Roa D, Grainger DC, Hurd D, Busby SJ, Struhl K, Nudler E. 2006. Extensive functional overlap between sigma factors in Escherichia coli. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13:806–814. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho BK, Kim D, Knight EM, Zengler K, Palsson BO. 2014. Genome-scale reconstruction of the sigma factor network in Escherichia coli: topology and functional states. BMC Biol 12:4. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-12-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lonetto M, Gribskov M, Gross CA. 1992. The sigma 70 family: sequence conservation and evolutionary relationships. J Bacteriol 174:3843–3849. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.3843-3849.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Remmele CW, Xian Y, Albrecht M, Faulstich M, Fraunholz M, Heinrichs E, Dittrich MT, Muller T, Reinhardt R, Rudel T. 2014. Transcriptional landscape and essential genes of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Nucleic Acids Res 42:10579–10595. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Capel E, Zomer AL, Nussbaumer T, Bole C, Izac B, Frapy E, Meyer J, Bouzinba-Segard H, Bille E, Jamet A, Cavau A, Letourneur F, Bourdoulous S, Rattei T, Nassif X, Coureuil M. 2016. Comprehensive identification of meningococcal genes and small noncoding RNAs required for host cell colonization. mBio 7:e01173-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01173-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Du Y, Lenz J, Arvidson CG. 2005. Global gene expression and the role of sigma factors in Neisseria gonorrhoeae in interactions with epithelial cells. Infect Immun 73:4834–4845. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4834-4845.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carbonnelle E, Helaine S, Nassif X, Pelicic V. 2006. A systematic genetic analysis in Neisseria meningitidis defines the Pil proteins required for assembly, functionality, stabilization and export of type IV pili. Mol Microbiol 61:1510–1522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nassif X, Marceau M, Pujol C, Pron B, Beretti JL, Taha MK. 1997. Type-4 pili and meningococcal adhesiveness. Gene 192:149–153. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00802-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Virji M, Alexandrescu C, Ferguson DJ, Saunders JR, Moxon ER. 1992. Variations in the expression of pili: the effect on adherence of Neisseria meningitidis to human epithelial and endothelial cells. Mol Microbiol 6:1271–1279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Virji M, Kayhty H, Ferguson DJ, Alexandrescu C, Heckels JE, Moxon ER. 1991. The role of pili in the interactions of pathogenic Neisseria with cultured human endothelial cells. Mol Microbiol 5:1831–1841. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chamot-Rooke J, Mikaty G, Malosse C, Soyer M, Dumont A, Gault J, Imhaus A-F, Martin P, Trellet M, Clary G, Chafey P, Camoin L, Nilges M, Nassif X, Duménil G. 2011. Posttranslational modification of pili upon cell contact triggers N. meningitidis dissemination. Science 331:778–782. doi: 10.1126/science.1200729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jennings MP, Jen FE, Roddam LF, Apicella MA, Edwards JL. 2011. Neisseria gonorrhoeae pilin glycan contributes to CR3 activation during challenge of primary cervical epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol 13:885–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haas R, Meyer TF. 1986. The repertoire of silent pilus genes in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: evidence for gene conversion. Cell 44:107–115. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90489-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Segal E, Hagblom P, Seifert HS, So M. 1986. Antigenic variation of gonococcal pilus involves assembly of separated silent gene segments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83:2177–2181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.7.2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Serkin CD, Seifert HS. 1998. Frequency of pilin antigenic variation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol 180:1955–1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Helm RA, Seifert HS. 2010. Frequency and rate of pilin antigenic variation of Neisseria meningitidis. J Bacteriol 192:3822–3823. doi: 10.1128/JB.00280-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang JT, Syed A, Gralla JD. 1997. Multiple pathways to bypass the enhancer requirement of sigma 54 RNA polymerase: roles for DNA and protein determinants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:9538–9543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Studholme DJ, Buck M. 2000. The biology of enhancer-dependent transcriptional regulation in bacteria: insights from genome sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett 186:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rendon MA, Lona B, Ma M, So M. 2018. RpoN and the Nps and Npa two-component regulatory system control pilE transcription in commensal Neisseria. Microbiologyopen doi:10.1002/mbo3.713:e00713. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Okada Y, Okada N, Makino S, Asakura H, Yamamoto S, Igimi S. 2006. The sigma factor RpoN (sigma54) is involved in osmotolerance in Listeria monocytogenes. FEMS Microbiol Lett 263:54–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jolley KA, Maiden MC. 2010. BIGSdb: scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics 11:595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chenna R, Sugawara H, Koike T, Lopez R, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG, Thompson JD. 2003. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res 31:3497–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simons RW, Houman F, Kleckner N. 1987. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene 53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wormann ME, Horien CL, Johnson E, Liu G, Aho E, Tang CM, Exley RM. 2016. Neisseria cinerea isolates can adhere to human epithelial cells by type IV pilus-independent mechanisms. Microbiology 162:487–502. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. 2008. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.